Outsourcing Continuing Airworthiness Management Activities: Benefit and Risks

Info: 33127 words (133 pages) Dissertation

Published: 26th Oct 2021

Tagged: Aviation

Outsourcing Continuing Airworthiness Management activities is a benefit or a risk? Does EASA need to change the CAMO rules?

Abstract

Under current legislation, Commission Regulation (EU) No. 1321/2014, both air carriers and commercial air transport operators have to develop their own Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation which has the purpose of managing the tasks and activities associated with the continuing airworthiness of the fleet. Moreover, if the operator is deciding to outsource continuing airworthiness management tasks and activities, it will be limited and subject to the European Competent Authority approval from where the air carrier or the commercial air transport operator was registered. To put it in another way, the operator will be limited when outsourcing continuing airworthiness management tasks or activities.

This dissertation aims to investigate and evaluate the risks and benefits of outsourcing an airline or commercial air transport operator’s continuing airworthiness management activities and tasks. Based on this, an outsourcing decision model is developed which has the scope to help the operators on deciding whether it is beneficial to manage the continuing airworthiness tasks and activities in house or to outsource a part of them. In addition, this dissertation will analyse the regulations governing the continuing airworthiness to see if the European Aviation Safety Agency has to create a more flexible environment for airlines and commercial air transport operators for managing the continuing airworthiness. Consequently, the Notice of Proposed Amendment 2010-09 developed by the European Aviation Safety Agency will be analysed. The NPA 2010-09 proposes that air carriers or commercial air transport operators are offered the choice to outsource all continuing airworthiness tasks and activities to an approved stand-alone Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation and in this instance the operator is not required anymore to develop its own CAMO.

By choosing the structured interview as a research method, the researcher is looking to explore concepts, ideas and interpretations from the perspectives of the respondents that are experienced within the field of study and are knowledgeable about this topic. The purpose of interviewing industry experts is to gather primary information which is to offer a better understanding and an industry overview of the topic being analysed in this dissertation.

List of tables and figures

Figure 3.1: Continuing Airworthiness Process

Figure 3.2: EASA Initial and Continuing Airworthiness Regulation Structure

Figure 3.3: Part M in Relation to Maintenance of Aircraft

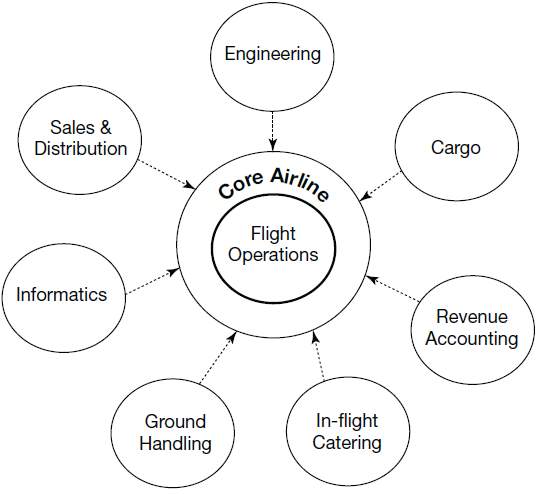

Figure 4.1: Traditional Airline Business Model

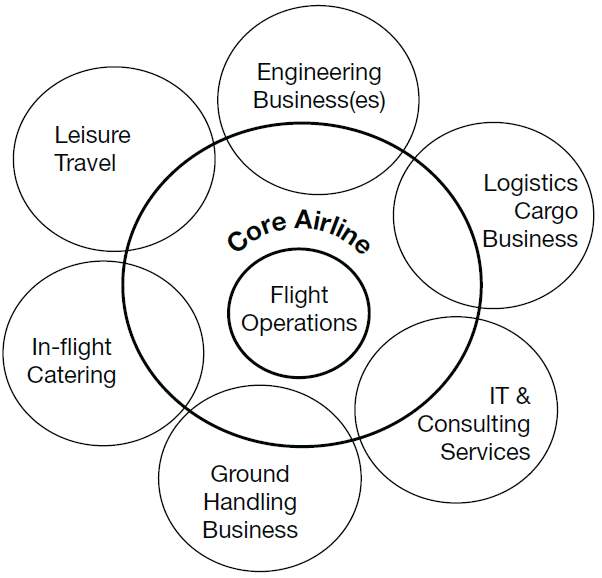

Figure 4.2: Virtual Airline Business Model

Figure 4.3: Aviation Business Model

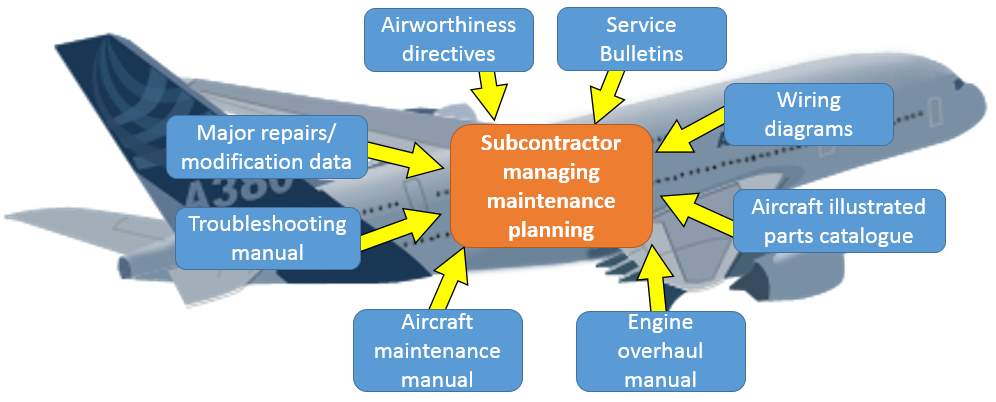

Figure 4.4: Important information needed by the subcontractor to carry out maintenance planning

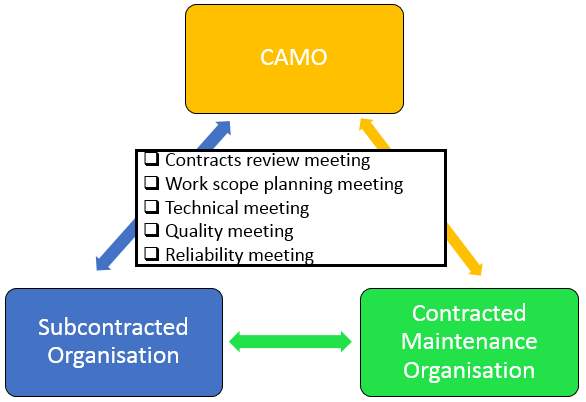

Figure 4.5: communication between CAMO, contracted Part 145 and subcontracted party

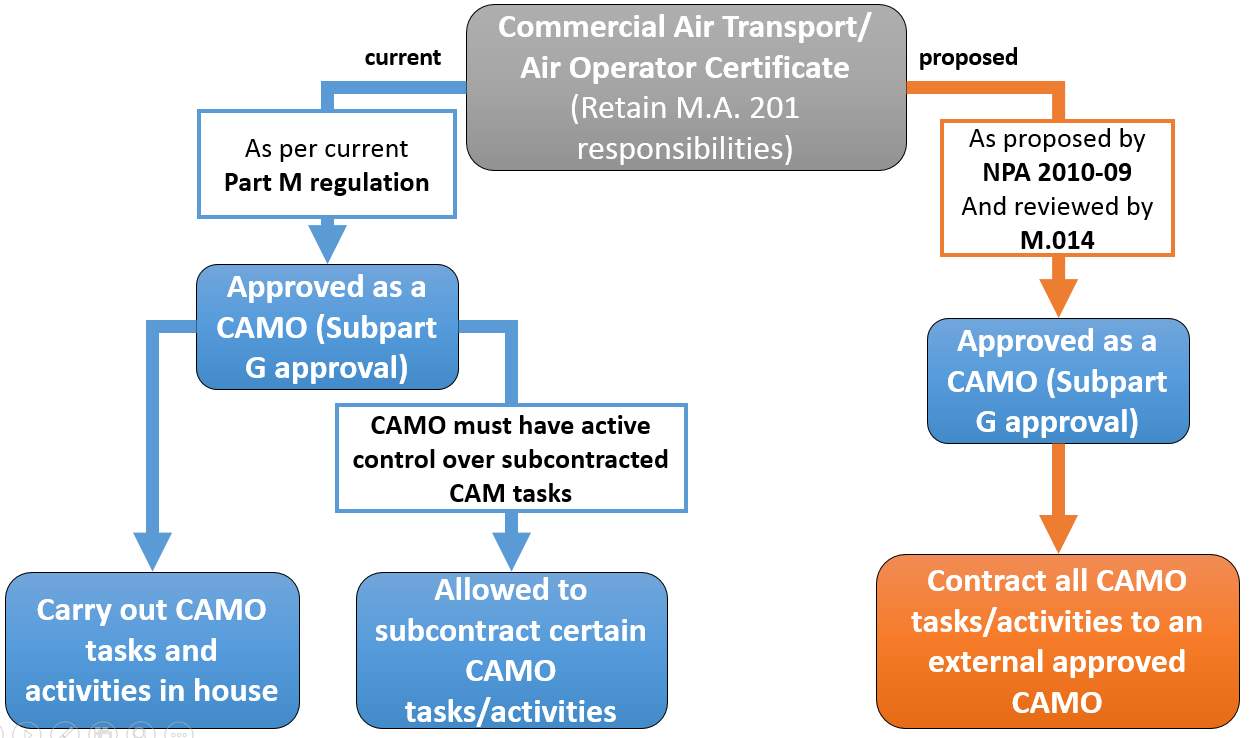

Figure 4.6: Possible choices for a CAT/licensed air carrier to ensure continuation of the aircraft airworthiness

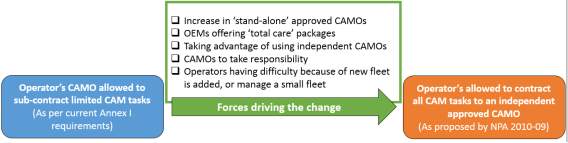

Figure 4.7: Forces driving the change of the legislation governing continuing airworthiness

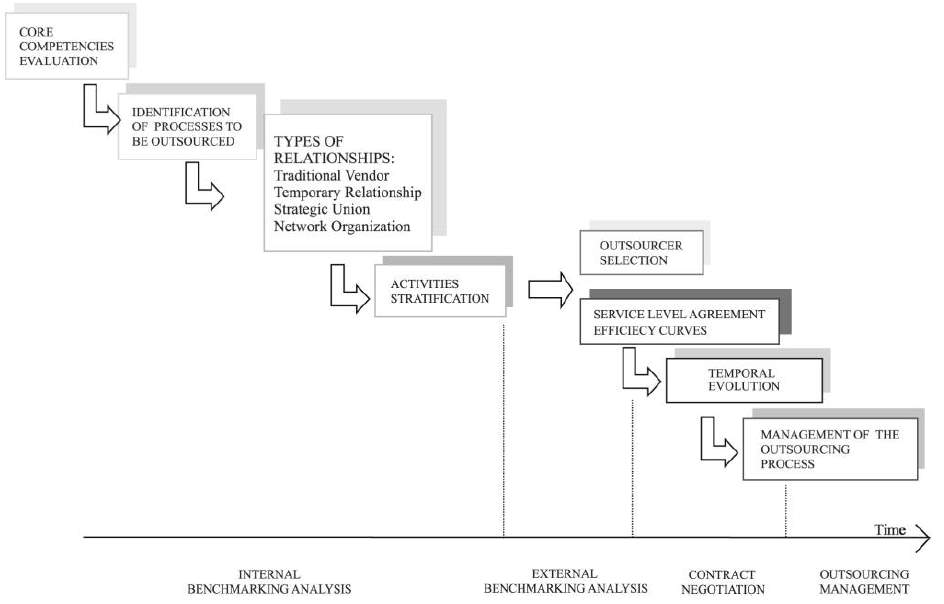

Figure 4.8: Rational and systematic approach to outsource CAM tasks and activities

List of abbreviations

AD = Airworthiness Directive

AMC = Applicable Means of Compliance

AOC = Air Operator Certificate

ARC = Airworthiness Review Certificate

C of A = Certificate of Airworthiness

CACE = Continuing Airworthiness Control Exposition

CAM = Continuing Airworthiness Management

CAME = Continuing Airworthiness Management Exposition

CAMO = Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation

CAT = Commercial Air Transport

CDL = Configuration Deviation List

EASA = European Aviation Safety Agency

EU = European Union

GM = Guidance Material

ICAO = International Civil Aviation Organisation

MEL = Minimum Equipment List

MP = Maintenance Programme

NAA = National Aviation Authority

NPA = Notice of Proposed Amendment

PICAO = Provisional International Civil Aviation Organisation

SARP = Standard and Recommended Practice

SB = Service Bulletin

TC = Type Certificate

TDO = Type Design Organisation

Table of Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1

1.1 Hypothesis

1.2 Research question

1.3 Aims and objectives

1.4 Background

1.5 Challenges

1.6 Methodology

1.7 Sources / Bibliography

Chapter 2

2.1 Difference between qualitative and quantitative research

2.2 Research methods

2.3 Analysis of the interviews

2.4 Primary research limitations and challenges

Chapter 3

3.1 From airworthiness to continuing airworthiness concept

3.2 Continuing airworthiness under ICAO

3.3 Overview of continuing airworthiness under EASA

3.4 Responsibilities of an operator and overview of Part M Sub-part G

Chapter 4

4.1 Outsourcing in aviation

4.2 Outsourcing an airline’s CAMO activities

4.3 Changing CAMO rules – NPA 2010-09

4.4 Decision model to outsource CAM tasks and activities

Conclusions and recommendations

Appendices

List of references

Introduction

Continuing airworthiness is an important aspect of the commercial aviation industry because this concept is enhancing safety by ensuring that operated aircraft for commercial reasons have to be always in an airworthy condition. In the European Union (EU) any licenced air carrier or commercial air transport (CAT) operator registered in one of EU’s member countries has to comply with the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) regulations. Under Commission Regulation (EU) 1321/2014 a licenced air carrier or CAT operator has to develop an internal Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation (CAMO) department which has to manage the continuing airworthiness management (CAM) tasks and activities that keeps the aircraft airworthy. The air carriers or CAT operators can outsource those CAM tasks and activities however, it is limited. EASA took the initiative to develop the Notice of Proposed Amendment (NPA) 2010-09 which proposes that airlines shall have the option to outsource all CAM tasks and activities. This NPA is still active and under discussions.

The core questions investigated in this dissertation are: is the outsourcing the CAM tasks and activities a benefit or a risk for airlines and CAT operators? Does EASA need to change Part M to make the continuing airworthiness legislation more flexible for commercial aviation? Therefore, the objectives of this dissertation are to determine if the outsourcing of CAM tasks is a benefit or a risk and to investigate if EASA has to change CAMO rules. Another objective is to develop an outsourcing decision model which will potentially help the air carriers and CAT operators.

The first chapter includes information about the hypothesis of this dissertation, its aim and objectives, research questions, background and potential challenges. In addition, the first chapter includes a brief description of how primary and secondary research will be gathered. In the second chapter it is discussed in detail the research methodology and method selected to gather information for primary research. Also, this chapter contains information on how the primary research was conducted and how the information was analysed. The third chapter is part of the literature review and is describing the continuing airworthiness concept. Also, third chapter provides an overview of how the continuing airworthiness is regulated under EASA. Moreover, the main focus of the third chapter is to identify the responsibilities of the operator and provide an overview of the Annex I Sub-part G of Commission Regulation (EU) 1321/2014. In the final chapter the author is discussing what CAM activities and tasks can be outsourced by a licensed air carrier or commercial air transport operator. In addition, this chapter outlines the idea behind the NPA 2010-09 and its purpose. Furthermore, at the beginning of the chapter the outsourcing in aviation is briefly discussed and at the end of it, the outsourcing decision model based on an economic model is developed and explained.

Chapter 1

1.1 Hypothesis

Continuing airworthiness is one of the most important key contributors to enhancing safety in commercial aviation. Continuing airworthiness[i] comprises from key maintenance tasks and activities which ensure that the aircraft will continue to operate in safe conditions during its operating life. Under the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), any European Union (EU) licensed air carrier[ii] or commercial air transport (CAT) operator[iii] must have their own Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation (CAMO), as per Commission Regulation (EU) No. 1321/2014[iv] Annex I. The purpose and objectives of a CAMO department is to keep the aircraft airworthy during its operating life. Some of the in-house CAMO activities of a licensed air carrier or CAT operator can be outsourced to an independent approved CAMO company. Although the CAMO activities that can be outsourced are limited, some airlines have different views about outsourcing and this might depend on what kind of business model the airline is operating.

Recently, there have been initiatives made by EASA to change the regulatory framework governing CAMO through the Notice of Proposed Amendment (NPA) 2010-09[v] which is questioning if it is possible that licensed air carriers or CAT operators can outsource all CAMO’s activities. However, no consensus has been reached over NPA 2010-09 which is still being debated. Being able to outsource CAMO activities and tasks may help start-up and established airlines to avoid the financial burden through outsourcing the CAMO department and pay more attention to their core business and competencies. Moreover, independent approved CAMO companies will not only be fully contracted by leasing companies but also by licensed air carriers and CAT operators that wish to outsource all CAMO tasks and activities. Therefore, the option of being able to outsource all CAMO activities and tasks will create a flexible solution for licensed air carriers and CAT operators and this may allow them to focus more on their core business and competencies to maximise profit.

1.2 Research question

Is outsourcing Continuing Airworthiness Management activities and tasks a benefit or a risk?

- This particular question will provide an insight into whether or not the decision of outsourcing the CAM activities brings a huge benefit to CAT operators and air carriers.

- In order to assess the benefits and risks of outsourcing CAM activities an outsourcing decision model will be developed.

Does EASA’s legislative framework governing CAMO need to be changed?

- In case the NPA 2010-09 will supersede the current rules governing continuing airworthiness, CAT operators and air carriers will focus more on their core business and the financial burden involved in developing their own CAMO department will not be required anymore. Also, the independent approved CAMOs will get more business by being fully contracted by CAT operators and air carriers.

1.3 Aims and objectives

1.3.1 Aim of this dissertation

The primary aim of this dissertation is to investigate and evaluate the benefits and risks of outsourcing CAMO activities and, based on this, to create an outsourcing decision model regarding continuing airworthiness activities. The secondary aim is to assess the opinions of different areas of the commercial aviation industry to see if EASA has to change the continuing airworthiness rules to create a flexible environment from which the aviation industry in the EU can benefit as a whole.

1.3.2 Objectives of this dissertation

The first objective is to determine what are the benefits and risks of outsourcing continuing airworthiness activities. This will require a good understanding of EASA regulatory framework needed in particular, the Annex I of Commission Regulation (EU) 1321/2014 including any relevant Guidance Materials and Acceptable Means of Compliance. Also, industry opinions will be used to understand better the risk and benefits of outsourcing CAMO activities.

The second objective is to find out what will be the impact of outsourcing all CAMO activities in case EASA will supersede current continuing airworthiness rules and to what extent the aviation industry will benefit from this.

The third objective is to develop a continuing airworthiness outsourcing decision model for CAT operators and air carriers.

1.4 Background

During a recent work experience I had the opportunity to take an internship with the CAM department of an aero-club. All CAMO activities were done in-house and nothing was outsourced to any independent organisation. When new services such as supplemental type certificates and CPCP programs had to be developed it was taking a long time and a lot of resources to do it especially that the aero-club owned an impressive fleet of gliders, aerobatic aircrafts and lightweight aircrafts. Sometimes not having the expertise in house means that time and resources are required to develop specific services. In addition, recently I had the opportunity to work in an independent CAMO which was dealing mainly with large airplanes in transition from one operator to another. However, most of the work generated for this independent CAMO was coming from aircraft leasing companies. Also, studying extensively in the Aviation Technology degree about EASA’s regulatory framework, I have started to focus on the continuing airworthiness legislation. Thus, being exposed to both independent and in-house CAMO gave me the idea of choosing this topic as a main research subject for this dissertation.

1.5 Challenges

- Primary research might be a challenge as specific contacts in the aviation industry are required;

- Obtaining the necessary resources for the literature review as there are no books written specifically on this subject;

- Researching and understanding the EASA’s regulatory framework;

- Developing a conceptual outsourcing model for continuing airworthiness activities will hugely depend on primary and secondary research;

More information on challenges encountered during this research can be found in chapter 2.4 Primary research challenges and limitations.

1.6 Methodology

1.6.1 Primary research

Primary research will comprise of interviews/ questionnaires which will be addressed to airlines (both legacy and low cost carriers), independent CAMO companies and Competent Authorities. Primary research may also be under the form of analysing both qualitative and quantitative information made available. More details on primary research methods and methodology can be found in second chapter.

1.6.2 Secondary research

Secondary researchwill comprise of EASA regulations governing continuing airworthiness such as Annex I to Commission Regulation (EU) No. 1324/2014, NPA No. 2010-09 and International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) Annex 6 [vi] Part I and Annex 8 [vii]. In addition, library resources, journal articles, internet resources and any relevant conference proceedings. Using secondary research materials, a critical literature review will be used to evaluate in greater detail why and why not to outsource CAMO activities.

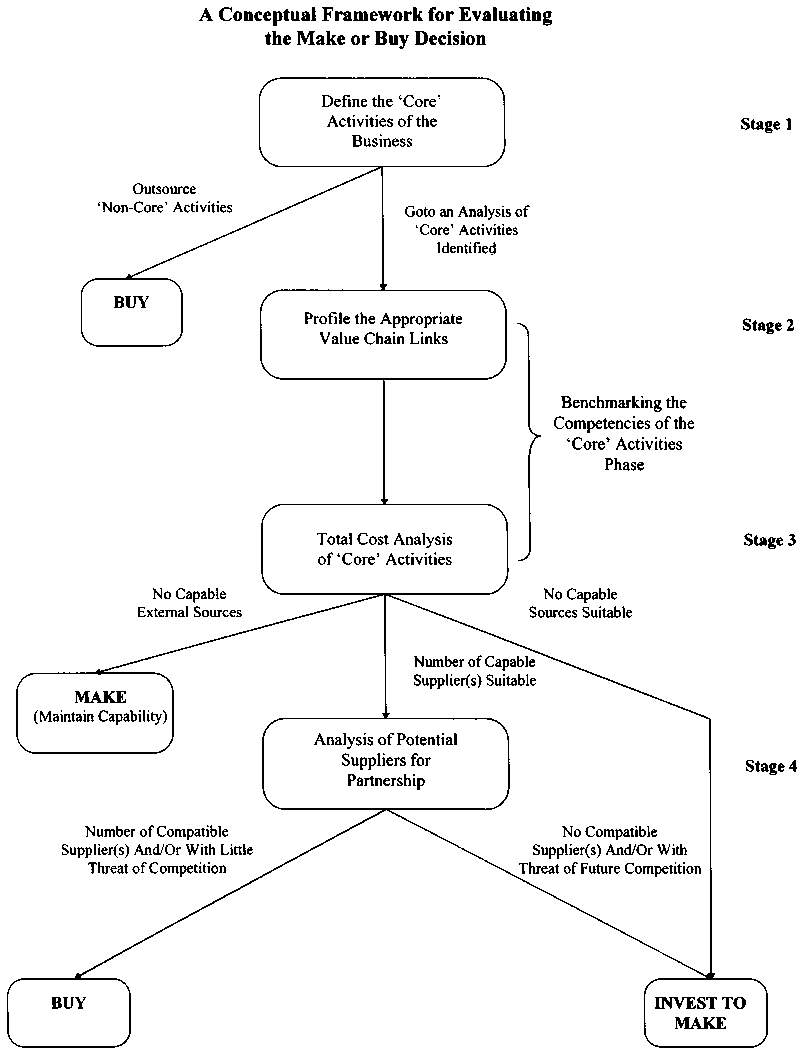

Three options are identified in relation to outsourcing CAMO activities and those are: keeping CAMO activities in house, outsourcing partially CAMO activities (as reflected by the current Commission Regulation (EU) No. 1324/2014) or fully outsourcing the CAMO activities (if NPA 2010-09 will be adopted by European Commission to supersede current legislation). The options can be used in conjunction with a SWOT/Risk analysis to develop a conceptual outsourcing model for continuing airworthiness activities.

1.7 Sources / Bibliography

- European Aviation Safety Agency regulations: Annex I to Commission Regulation (EU) No. 1324/2014, NPA 2010-09

- ICAO Annex 6 Part I and Annex 8

- Irish Aviation Authority and European Aviation Safety Agency websites

- Dublin Institute of Technology library and E-resources provided through DIT

- Google Scholar, books, journals, conference proceedings

- Other internet resources especially websites with a major focus on aviation industry i.e.: Flight Global, Royal Aeronautical Society etc.

- A full list of references it is provided at the end of this dissertation.

Chapter 2

2.1 Difference between qualitative and quantitative research

The qualitative research examines and takes into consideration experiences, attitudes and behaviour (Dawson, 2002, p. 14). The data or information gathered in a qualitative research is mainly qualitative in character (Saldana, 2011, p. 3) and uses research methods such as interviews or focus groups for primary research (Dawson, 2002, p. 14). Through a qualitative research, the researcher is aiming to gain a better understanding of the selected topic to be investigated by collecting data from other individuals’ experiences (Blair, 2016, p. 56). This type of research will require few people to take part in the research, however the contact with them will last longer (Dawson, 2002, p. 14).

Comparatively, the quantitative research will always generate statistics by using large-scale survey research and through research tools like structured interviews and questionnaires. To gather data for a quantitative research more people are involved and the contact with those people might be shorter when comparing with the qualitative research (Dawson, 2002, p. 15). In a quantitative research, the researcher will measure the relationship, which is the basis of predictions, between a dependent or outcome variable and an independent variable (Blair, 2016, p. 52). Furthermore, it is acknowledged that the researcher can achieve a combination of both qualitative and quantitative research. This is known as triangulation and some researchers claim that is a good approach for a thesis as the strengths and weaknesses of both qualitative and quantitative research are somehow balancing each other (Dawson, 2002, p. 20).

Providing that the researched topic is narrowed and focused on a specific area of study, the qualitative research was selected to be the main methodology framework of this dissertation. Moreover, the researcher chose the qualitative research because it is important to understand interviewees’ knowledge and their experiences. On the contrary, if the researcher was to select a quantitative research this could have been a constraint to find out qualitative answers for the core questions (Savin-Baden and Major, 2013, pp. 5-7). To find out the answers for the core questions, the researcher has to approach specific individuals who are working in the field of the studied topic and have experience within the field of study. Furthermore, by employing a qualitative research, the researcher will make the decision of what to be included or excluded in the research, what are the research questions and who are the participants. Consequently the qualitative research is a flexible research methodology framework where the boundaries can only be created by the researcher (Savin-Baden and Major, 2013, pp. 11-2). In addition, the main advantage of employing a qualitative research is that the research methods can be defined in the early planning stage. Therefore, the researcher becomes more focused and will know precisely what will be the most appropriate way to gather information for the research (Dawson, 2002, p. 33).

2.2 Research methods

The research methods are tools used by researchers to collect primary information. The major research methods are focus groups, questionnaires, participant’s observation and interviews. The focus groups method involves a moderator and a number of individuals discussing a particular topic. The moderator’s role is to ask questions, mediate the group conversation and make sure that this is not deviated from the topic under discussion (Dawson, 2002, pp. 27-38). On the other hand, questionnaires are associated with quantitative research through which a scholar is looking to gather measurable data which is presented in a numerical format (Blair, 2016, p. 52). Different from focus groups and questionnaires as research methods, the participant observation method is the research tool through which the scholar wants to notice and have a deeper understanding on what is happening in a specific culture without interacting with it (Dawson, 2002, pp. 27-38). In contrast, the interview research method is one of the most common tools used to gather primary research information when the scholar is undertaking a qualitative research. Dawson identifies three different types of interview research methods: unstructured, semi-structured and structured interviews (Dawson, 2002). Because the researcher approached the qualitative research for this dissertation, the research tool used to collect data for primary research is the interview method (more details in subchapter 2.2.1).

2.2.1 Interview as a research method

Interview is one of the main methods used to gather information and data in a qualitative research. Interview is defined by Savin-Baden as being a conversation between two persons where the interviewer asks questions and the interviewee answers them. The purpose of the interviewer is to obtain in-depth information shared by the interviewee from it is own experience and perspective (Savin-Baden and Major, 2013, pp. 358-68).

The main advantage of the interview is that the researcher can adapt it while interviewing individuals. Through an interview concepts, ideas and interpretations can be explored whereas by carrying a questionnaire similar information cannot be gathered. Moreover, by carrying interviews, the feelings and motives of the person interviewed can be investigated. This is where a questionnaire will fail to record such information because through interviews ideas and concepts can be clarified or further developed. The down side of the interview method is that it is time-consuming and only a small number of people can be interviewed while compared to a higher number of respondents when selecting the questionnaire as a research method. In addition, the interview can be influenced by personal feelings and opinions and there is always the threat of biasing. As the information obtained is qualitative in nature it might be a challenge to analyse it. Similarly to a questionnaire, it is really important when the researcher is formulating the questions which are to be addressed to the interview participants (Bell and Waters, 2014, p. 178).

There are three common types of interviews: unstructured, semi-structured and structured interviews. By choosing the unstructured or in depth interview the researcher will look to achieve a better understanding of the researched topic through the perspective offered by the interviewed participant. The interviewee is allowed to talk freely and the interviewer has to keep the directional influence at minimum by asking as fewer questions as possible. The advantage of this type of interview is that it is easy to manage. However, as the interviewer has a lower interaction in the conversation it may become difficult to remain quiet. The interviewer has to stay focused and make sure that the participant is not changing the subject of the topic. In addition, unstructured interviews produce a huge amount of data which may be difficult to analyse (Dawson, 2002, pp. 27-8). On the other hand, a semi-structured interview requires the researcher to follow a set of questions, but during the interview additional questions may arise from the conversation. In general the main questions asked during the interview tend to follow an order. To allow the interview’s participant to express its opinions freely the questions are usually open-ended (Savin-Baden and Major, 2013, p. 359). The structured interview is discussed in detail in the next subchapter (2.2.2 Structured interviews) as the researcher chose this approach to collect information for primary research.

2.2.2 Structured interviews

A structured interview requires the researcher to follow a particular set of questions that are to be asked in each interview. Although most of the questions asked are closed type questions, sometimes the researcher has a tendency to formulate the questions as open-ended. The structured interview is the research tool selected for this dissertation as it is considered to be the most suitable qualitative research method. Through a structured interview, the researcher is trying to minimise the variation in questions. Moreover, one advantage of the structured interviews is that the interviewer avoids to upset the conversation and opinions exposed by the interviewee. Also, by asking all participants similar questions, common information is collected and this is making easier for the researcher to analyse and compare the information provided by each participant. This particular research method can be used only if the researcher has a good understanding of the topic. Usually this is achieved by carrying a literature review of the topic and based on this the questions are structured for the interview. One disadvantage of the structured interview is that the questions prepared by the researcher may limit and restrict the investigation of issues that were not identified by the researcher when the questionnaire was developed (Savin-Baden and Major, 2013, pp. 358-9).

2.2.3 Ethics when conducting interviews

The researcher has to make sure that there is no legal boundary breached while carrying out the primary research. For this reason a good approach was followed as per Bell and Waters (2014) which points out that it is really important to let the participants know what the research is about and why they were chosen to be interviewed. Equally important is to let the participants know about the interview process and for what the information acquired during the interview is going to be used for. Therefore, each participant received a document before they confirmed their availability for the interview. The document entitled “Dissertation interview” contains details about the researched topic, objectives of the research, general ground rules to be agreed and questions asked during the interview (for more details on ‘Dissertation Interview’ document see Appendix IX). All participants have been given equal opportunity to enquire if there is any information or statement in the ‘Dissertation Interview’ document needed to be clarified. This was to make sure that the participants fully understood what the research is about and what will be the questions that the researcher will focus on during the interview. Also, this approach was followed to eliminate any uncertainty caused by participants withdrawing from the interview stage based on misleading or ambiguous interview process and/or questions.

To ensure that the participants know about their rights and identify the interviewee responsibilities, some ground rules have been implemented in the interview process document. The ground rules had to be agreed between respondents and researcher in order to protect any party’s position. All participants had the opportunity to remain anonymous. Also, they were asked if they wanted to be dissociated with the company/corporation they worked for. As part of analyzing the interviews, the researcher decided to protect the respondents’ identity (for more details see “Interview duration, place and ground rules” section from Dissertation Interview document attached in Appendix IX).

2.2.4 The interview protocol and process

The participants were approached through email to see if they wished to take part in the research and consequently interviewed. After they confirmed and accepted to be interviewed, the dissertation questionnaire was sent to them. This was to ensure that the respondents will fully understand the researched topic and also know what questions are going to be asked during the interview. Each participant had the right to request clarification in case there was an identified ambiguous process step or question.

To ensure the participation at the interview the location, date and time of the interview was decided upon the preference of respondents. At the start of the interview, each respondent was asked if the interview can be recorded and if they need any other clarification about the interview process or questions asked. In addition, each interviewee was asked if they would like to remain anonymous or not associated with their company they work for. This was to protect them in case the information gathered thorough the interview contained sensitive information about them or the company/corporation they work for. At the end of the interview the participants were asked if they would like to receive a transcript of the interview. This was to reflect a transparent analysis of what exactly they said and stated during the interview.

2.3 Analysis of the interviews

The analysis of the interviews is based on evaluation and examination made on each interview transcript which are attached in Appendix X. By analysing the first question it was found out that it is not a huge cost incurred on airlines setting their own CAMO but is important to mention that managing the CAM tasks and activities is only a labour intensive job and it hugely depends on the pay rates. This is one of the criteria which will influence an operator to outsource certain CAM tasks and activities and this is where the operator cannot compete with independent CAMOs offer, as they can perform the tasks cheaper. Furthermore, the outsourcing will hugely depend on airline’s fleet size, complexity of operations [flying short, medium or long haul routes], how many aircraft types are operated and to what extent the airline is unionized (in this case outsourcing being the last option). One of the airlines interviewed was outsourcing one of their aircraft type CAM tasks to a well-known technical services provider and the benefit of this was the knowledge pool that the subcontractor has. The CAMO manager stated that the subcontractor helps the airline to keep the aircraft in-service and without a third party input developing the in-service experience might be a challenge.

When the interview participants were asked what are the risks associated with outsourcing CAM tasks and activities, the following potential risks have been highlighted:

- Lack of oversight when the airline is not having control over the subcontracted CAM tasks and personnel performing them.

- Lack of performance as the third party is not performing as the airline would like them to perform. The underperformance might be because the contracted third party cannot take the influx of information for each managed aircraft.

- Improper service level agreements where one of the parties can take the advantage.

- Operator or contracted party missing significant information such as mandatory AD embodiment. This is caused by a lack of communication between the operator and contracted party and both entities working on different IT systems which are incompatible. Moreover, if the contracted party is performing work for other airlines or managing different aircraft types this can result in a ‘cross contamination’ of vital information.

All potential risks mentioned above can be prevented by having strong contracts in place and a sufficient level of oversight. A good oversight will comprise from implementing audit processes to assess the performance of the contracted party and to make sure that the contracted work [CAM tasks/activities] are carried out. In addition, the operator’s audit programme shall ensure that the contracted party has proper procedures and resources to manage the contracted CAM tasks/activities. To ensure a good communication between both parties, proper meetings have to be arranged and a good reporting system should be developed. To ensure a ‘good visibility’ for the aircraft managed by a contracted third party and to eliminate the likelihood of ‘cross contamination’ to occur, both parties shall either work on the same IT system/platform or the contracted party has to be fully trained to work as per the operator’s requirements and standards. A very important key point to mention is that the operator has to do his due diligence before contracting any organisation to manage CAM tasks/activities. This is mainly to ensure that the third party provider is a viable company, with a long term commitment and that will not go out of business causing the airline (or aircraft managed) to be grounded.

The fourth question asked, revealed that there is not a high risk between outsourcing CAM tasks/activities to either an approved stand-alone CAMO or a non-approved technical services provider organisation. In both cases it is a must that the operator’s CAMO has to review the contracted work performed by the third party to make sure the operator’s standards are followed and that the contractual agreements are followed. The required level of oversight is usually greater when CAM tasks/activities are outsourced to a non-approved organisation (not CAMO approved). Also, the work performed by a non-approved organisation has to be reviewed and certified by an operator’s CAMO while CAM tasks/activities carried out by an approved CAMO are certified. Additionally, the independent CAMOs are seen as a better choice as they reached a European standard by being approved by a particular NAA. A CAMO already went through the NAA’s audits while a non-approved technical services provider is not regulated. However, there are situations where non-approved organisations are as good as a CAMO and possibly more specialized than a CAMO, having that knowledge pool and in-service experience for certain aircraft types. Consequently, either a poor CAMO provider or a poor non-approved technical services provider will not last long on the market. Ultimately, the outsourcing decision stands with the operator who has to do their due diligence. It is a very common approach that the airlines will look to outsource CAM tasks and activities to reputable organizations disregarding that they are approved or not. Moreover, those reputable organisations are unlikely to go out of business as they have a massive financial back-up and a strong position in the market.

From the fifth and sixth questions it is concluded that the proposed amendment NPA 2010-09 will potentially eliminate the higher risks associated with sub-contracting a non-approved organisation. As the airlines will have the choice of outsourcing all CAM tasks and activities to an approved stand-alone CAMO, certain non-approved organisations providing technical services may look into getting a CAMO approval. This will not only raise the industry standard but will potentially bring them more customers. One of the respondents is stating that “if the non-approved organisation becomes approved by changing their processes to good processes it is an improvement and this will make a difference”. On the other hand there is a demand from the EU aviation industry that EASA has to offer the choice for airlines to outsource all of their CAM tasks and activities. This demand is mainly driven by airlines where the outsourcing is their business model, airlines that have a small fleet (including operations) and airlines which are looking to establish on the market (including start-up airlines). Another advantage is that multiple airlines making part of the same parent company will be able to use a centralized CAMO through which all airlines will share certain CAM services and build up the in-service experience. One potential issue with providing this option to airlines is how the airlines and CAMOs will control the accountability. Another challenge will be to ensure, manage and maintain a good relationship between both parties which will be vital for aircraft continuing airworthiness.

Regarding the development of the outsourcing decision model one interviewee advised that this should be based on an economic model. Before the outsourcing decision will take place the operator has to ask itself why there is a need to take into consideration the outsourcing option. As previously stated, the decision will be based on the airline business model, fleet size etc. Also, the operator has to take into account the competent authority’s acceptability for a third party to be contracted to manage operator’s CAM tasks. After this, the operator has to clarify what CAM tasks and activities have to be outsourced and this has to be supported by arguments which will contribute to outsourcing decision.

2.4 Primary research limitations and challenges

As mentioned previously in subchapter 2.2.2 one limitation of using the structured interview as a primary research method is that that the questions prepared by the researcher may restrict the investigation of issues that were not identified in the secondary research and when the questionnaire was developed. For instance, from one interview carried with one respondent, it was highlighted that there is the need to develop legislation to control and standardize those technical services companies and lessors managing engines. At the moment when an engine comes off the wing independent technical services providers can do all CAMO type functions but their work is not certified. The airline is generally re-analysing all information prepared by those independent companies in order to certify the status of the engines. Therefore, there is a scope for EASA to develop regulations to cover those organisations looking to obtain a dedicated CAMO approval for components, engines and APUs. This area is not well developed and regulated at the moment, and the engines, APUs and other aircraft components are more valuable than the airframe itself.

One challenge was that only five out of nine participants expressed their interest to be interviewed. The researcher targeted participants from airlines’ CAMO department, independent CAMOs and competent authorities in order to gather information with the scope to achieve a full industry overview for the researched topic. However, there were no participants interviewed which were involved or worked for a competent authority. Moreover, it was desirable to interview participants employed in all airline business models but only employees from a legacy and a regional airline took part in the interview. Under those circumstances, a full industry overview cannot be provided, as the primary research information cannot be analysed from different perspectives (from each airline business model and competent authority’s point of view). Another challenge encountered by choosing to research this topic is that there are no previous studies, dissertations or other academic papers to discuss about the Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation concept and gaps within the EU legislation governing this concept.

Chapter 3

3.1 From airworthiness to continuing airworthiness concept

The author Fillip de Florio (2016) defines the airworthiness concept as being “the possession of the necessary requirements of an aircraft to fly in safe conditions, within allowable limits”. In this simplified definition three important key elements can be identified: possession of necessary requirements, flying in safe conditions, and allowable limits. The possession of the necessary requirements refers to the standards and regulations which are followed to build, design and test an aircraft, its parts and components. In addition, the safe conditions makes reference to those conditions free of causing any harm, injury, illness to aircraft passengers or damage to a property or environment. Furthermore, the allowable limits means that the aircraft is flying within its approved flight envelope for which it is designed to operate into. Therefore, each aircraft type has specific structural load factors and speed ranges that cannot be exceeded and is designed to fly in specific types of operations. (Florio, 2016).

In contrast with the airworthiness concept, continuing airworthiness is regarded to be a set of processes which maintain or restore an airplane, its systems or parts of a system to a standardised airworthiness process established by a type design organisation. Sometimes from a safety perspective, it is identified that the original standards are not stringent enough when the operator may encounter issues such as systems malfunctions and faults while the aircraft is in service. For this reason, service life expectation of the aircraft may be reduced or extended if adequate corrective actions are taken. Therefore, the continuing airworthiness process carried out continuously during the aircraft life cycle may adjust the aircraft service life values and design standards. Equally important, is the revision of civil aviation regulations, standards and recommended practices based on findings while the aircraft is in service (Enders, Dodd, and Fickeisen, 1999).

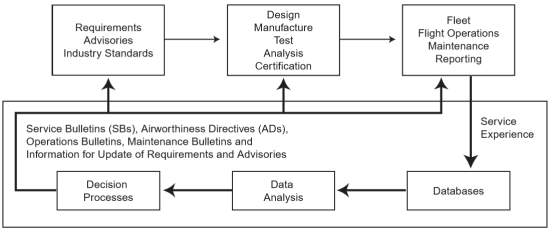

The continuing airworthiness process comprises from three key steps: generating a database, analysing data and decision process. The generation of database is done through gathering data from operators based on service experience. After that, data is analysed and often compared to the original certification process and results. The final step is the decision making process carried out by either an accident investigation authority or a national aviation authority and certification authorities. Furthermore, the manufacturers and operators of the aircraft, parts and components will be part of the decision making process (see Fig. 3.1) In all steps difficulties may be encountered because the acquisition of human and computer resources information may be insufficient to form a consistent database which makes it difficult to generate a database and analyse it (Enders, Dodd, and Fickeisen, 1999).

Figure 3.1: Continuing Airworthiness Process

Source: (Enders, Dodd, and Fickeisen, 1999)

3.2 Continuing airworthiness under ICAO

On December 1944, 52 States signed the Convention on International Civil Aviation – known as the Chicago Convention – to establish the Provisional International Civil Aviation Organisation (PICAO). In April 1947, PICAO turned into a fully operational organisation named as the ICAO which also became a United Nations agency (ICAO, 2017b). Nowadays ICAO works with its member states, and various aviation industry groups to develop Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs) and policies. By doing this, ICAO aims to improve safety and efficiency of the civil aviation sector at an international level. Equally important, the policies and SARPs makes commercial aviation aspire to an environmentally responsible and a more economic sustainable aviation sector. SARPs and policies are adopted by ICAO’s contracted states into air law that must be respected by the commercial aviation businesses operating in that particular country. Therefore, the ICAO SARPs and policies are more or less the global norms to harmonize the international commercial aviation (ICAO, 2017a).

The ICAO standards are highly important for civil aviation, especially for air carriers operating on international flights. Under Article 29 of the ICAO Convention it is established that each aircraft registered under an ICAO member country[viii] has a certificate of registration and a certificate of airworthiness[ix]. In addition to that, Article 31 requires that the certificate of airworthiness shall be valid during aircraft operations and should only be released by the State of Registry. Moreover, Article 33 obliges all ICAO member states to acknowledge any valid certificate of airworthiness released by an ICAO recognised State of Registry[x] provided that the established minimum standards are met (ICAO, 2006).

In accordance with standards provided in ICAO Annex 6 – Part I and following the State of Registry’s procedures, an operator has to maintain the operated aircrafts in an airworthy condition and also provide that the emergency equipment is serviceable for intended operations. Correspondingly, the airplanes shall be maintained and released to service only by approved maintenance organisations recognised by the State of Registry. Equally important, each operated airplane shall have a valid certificate of airworthiness while in service. Additionally, a group of persons shall be employed by the operator to ensure that the maintenance is performed in accordance with a maintenance control manual [xi]. Furthermore, the maintenance carried out on the airplane has to be executed in accordance with an approved maintenance programme [xii] (ICAO, 2010).

ICAO defines the concept of continuing airworthiness in the Airworthiness Manual as being a set of processes required to show compliance with airworthiness requirements established in the aircraft type certificate (TC) [xiii] or any other specifications stipulated by the State of Registry. In addition, the aircraft, its parts and components shall be in a state of safe operation at any point in time during the operating life. In particular, based on the ICAO Airworthiness Manual the operator has to accomplish the following minimum standard tasks in order to keep the aircraft airworthy (ICAO, 2013):

- The operator shall develop a maintenance programme for the aircraft operated. The maintenance programme has to comprise from specification, methods, procedures and maintenance tasks that are established by the aircraft manufacturer and tailored to specific operations carried by the operator.

- The operator has to report back to the type design organisation (TDO) [xiv] any defects, faults or malfunctions and important information or issues encountered during operations or when carrying out maintenance on the aircraft. The reporting procedure shall follow the requirements established by the State of Registry and State of the Operator [xv].

- When required by the TDO or it is necessary to ensure the structural integrity of the aircraft, the operator has to meet the airworthiness requirements taking into consideration the fatigue life limits, inspections or any special test to ensure the continuing airworthiness of the aircraft and its structural integrity.

- The operator has to implement a supplemental structural inspection programme (SSIP) and any other SSIP requirements if mandatory. In addition, the operator has to consider the TDO’s recommended SSIP. The SSIP may also include corrosion protection and control programme, Service Bulletin (SB) review and mandatory modification programme, repairs review for damage tolerance.

Regarding the exchange and use of the continuing airworthiness information the operator has to keep informed the State of Design and aircraft’s TDO in respect with any service difficulty experienced when operating the aircraft. Provided that the important information is shared by the operator, the State of Design or TDO can issue appropriate recommendations which shall have the objective of solving the problems of the aircraft in service (ICAO, 2013).

3.3 Overview of continuing airworthiness under EASA

The EASA, also known as the Agency, is an independent EU agency which became operational in 2002 through the adoption of Basic Regulation (EC) No. 1592/2002 [xvi] by the European Parliament and the Council of EU. Mainly, the Commission Regulation’s rules governing commercial aviation are mirroring the ICAO’s SARPs and recommended practices. However, the implementing regulations are binding rules which are more detailed and rigorous than ICAO SARPs. EASA’s purpose is to help the European Commission in drafting the necessary regulatory framework and assist in the development of implementing rules which governs the air safety and environmental protection. Moreover, by developing the necessary expertise to deal with civil aviation matters, EASA is assisting the EU member states and aviation industry to adopt the regulations. In the light of assisting the EU states to implement the rules, EASA can develop applicable means of compliance (AMC) and guidance materials (GM). More importantly, EASA has the authority to verify if the regulations are well implemented and respected by each member state. Also, EASA can carry out certification tasks and impose financial penalties on holders of certificates and approvals issued under the Agency and withdraw them in case of breaching the regulations (European Parliament and Council of the European Union, 2008).

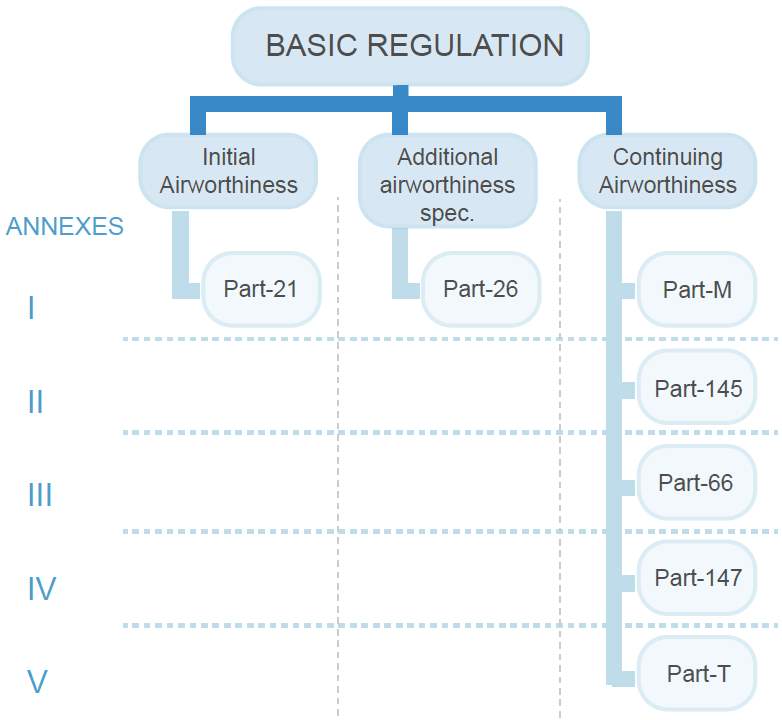

Fig. 3.2: EASA Initial and Continuing Airworthiness Regulation Structure

Source: (European Aviation Safety Agency, 2017c)

Under the Basic Regulation through which EASA was established, Initial Airworthiness and Continuing Airworthiness regulations have been developed (see Fig.3.2). The implementing rules on continuing airworthiness are adopted by European Commission Regulation (EU) No. 1321/2014. This regulation is setting up common technical requirements and administrative procedures with the scope to keep the aircraft and its components airworthy. The regulation applies to aircrafts registered in an EU member state and aircrafts registered in third countries that are used by an operator of which an EU member state is assigned to supervise the operations (European Union, 2014).

The implementing regulation on continuing airworthiness consists of five different annexes. The first annex is Annex I or Part M and contains requirements on how to manage the continuing airworthiness of the aircraft and components. Moreover, Part M contains requirements on organisations and personnel involved in managing the continuing airworthiness of aircraft and components. Additionally, the requirements for continuing airworthiness for aircraft possessing a permit to fly can be found in this annex. The second annex, the Annex II or Part 145, incorporates requirements for approval of maintenance organisations engaged in maintenance of aircrafts used for commercial air transport and aircraft components intended for fitment. Furthermore, Part 145 includes requirements on qualifications of personnel which performs and/or controls the aircraft maintenance and non-destructive testing carried out on aircraft components and/or structures and releases them to service. Requirements for certifying the engineers carrying out maintenance on airplanes, helicopters and components are established in Annex III or Part 66. Within the Part 66 different type of licence categories are distinguished and correspondingly a level of technical and practical knowledge is affixed to each licence category. Nonetheless, Part 66 covers the renewal of such licences, as well as the possibility of licence extension to multiple categories and also the prerequisite of individual type rating is included in this annex. On the other hand, Annex IV or Part 147 establishes binding rules for organisations involved in the training of engineers carrying out non-destructive tests or maintenance on aircraft and components. Through Part 147 the approved training organisations can be entitled to conduct recognized basic and type training courses, to carry out examinations and issue training certificates. (European Union, 2014). The last annex, Annex V or Part T, contains amendments to AMC[xvii] and GM[xviii] of Annex I, II and III. All of the amended AMC and GM are focusing on the safety issues related with the implementation of continuing airworthiness programme by competent authorities[xix]. Also, Annex V is making reference to risk mitigation associated with the performance of maintenance and the necessity of developing corrective actions. Moreover, Part T covers AMC and GM for regulatory coordination issues to assure that the continuing airworthiness Implementing Regulation is applied efficiently by all entities involved in commercial aviation (European Aviation Safety Agency, 2016b).

3.4 Responsibilities of an operator and overview of Part M Sub-part G

The Annex I is dealing with the management of aircraft maintenance which is cross referenced with the continuing airworthiness. In particular the Annex I of Commission Regulation (EU) No. 1321 from 2014 lays out regulations on how to manage the maintenance with special consideration to the work orders and contracts for maintenance performed by an approved Part 145 organisation (Total Training Support Ltd, 2014).

3.4.1 CAMO responsibilities

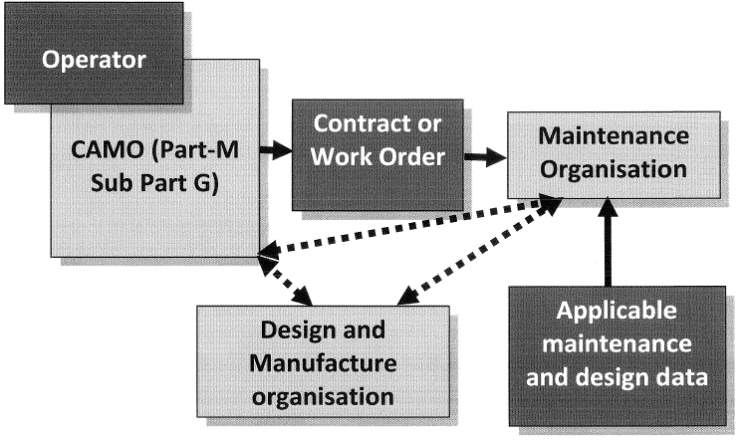

Figure 3.3: Part M in Relation to Maintenance of Aircraft

Source: (Total Training Support Ltd, 2014)

As per M.A. 201, an EU registered licensed air carrier or a Commercial Air Transport (CAT) operator has to apply for CAMO approval as per Part M Subpart G. The CAMO will be responsible for managing the continuing airworthiness of the aircraft. To receive a CAMO approval the operator has to comply with all requirements outlined in Part M Subpart G (European Commission, 2015b). The main objective of a CAMO is to be the interface between the CAT/air carrier operator and the internal approved or contracted approved maintenance organisation (See Fig. 3.3).

The CAMO is responsible for sending the work orders to be accomplished by an approved Part 145 maintenance organisation. In essence, any person or organisation performing maintenance will be responsible for the tasks and activities carried out (European Union, 2014). However, the operator is accountable and responsible to demonstrate that the aircraft operated are airworthy. Equally important is that the operator will make sure that the emergency equipment of the aircraft operated is installed and serviceable. Nonetheless, the operator has to ensure that the Air Operator Certificate (AOC) of the aircraft remains valid and the maintenance carried out on the aircraft is in accordance with a maintenance programme (European Commission, 2015a). Furthermore, if the operator identifies any condition of the aircraft or any component that might put in danger the flight safety, the competent authority assigned by the state of registry and the holder of the type or supplemental type design shall be informed within 72 hours (European Union, 2014).

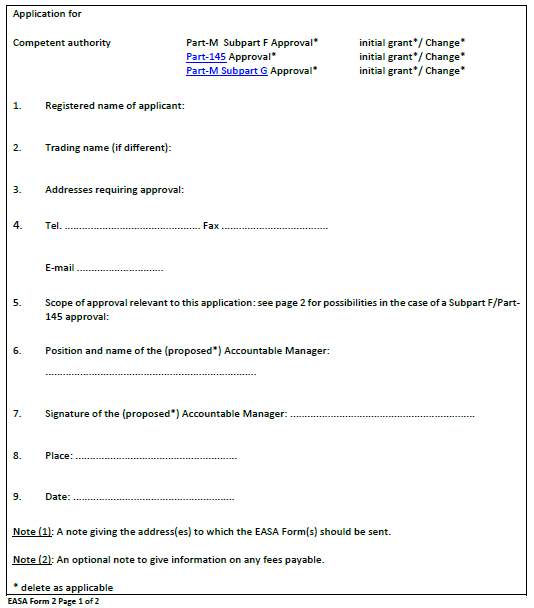

3.4.2 Application for CAMO approval

In order to obtain a CAMO approval the representative of the air carrier has to submit an EASA Form 2 [xx] or an equivalent application to the competent authority that is also issuing the AOC for the air carrier (European Union, 2014). Moreover, as part of the CAMO approval process the operator has to develop a continuing airworthiness management exposition (CAME) (European Commission, 2015b).

To demonstrate that the organisation [xxi] is compliant with the CAME and Annex I at any point in time, the accountable manager [xxii] has to confirm by signing a written statement included in CAME. The accountable manager has to nominate a person or multiple individuals that will ensure that the CAMO is all the time compliant with Part M Sub-part G. In addition, in the case of a licensed air carrier the accountable manager has to nominate a post-holder [xxiii] that will supervise and manage the continuing airworthiness activities. In order to clarify the chain of responsibilities within the organisation, a corporate structural chart including the names and titles of nominated post-holders has to be included in CAME. Similarly, if the CAMO has the privilege to issue or extend the Airworthiness Review Certificates (ARC) [xxiv], names of the personnel authorised to issue/extend such certificates must be listed in the CAME. Likewise, the CAME should also contain a list with the airworthiness staff [xxv] and if applicable a list with the staff authorised to issue permits to fly [xxvi]. CAME will also contain detailed information about the operator’s scope of work and procedures in place through which the operator will show compliance with Annex I and how the CAME can be amended for future improvements. Furthermore, the CAME has to contain a brief about the location of the facilities of the operator in question. Also, a list with the approved maintenance programme (or programmes if there is more than one type of aircraft operated) or an approved generic maintenance programme shall be incorporated in the CAME (European Commission, 2015b). An example of a CAME layout is attached to Appendix I.

3.4.3 CAMO facilities and personnel requirements

The organisation has to provide adequate office accommodation for employees whether they carry out activities related to continuing airworthiness management, quality staff, technical records and planning. Having sufficient office space will ultimately contribute to good standards. Additionally, the CAMO has to accommodate an adequate technical library and a room for document consultation (European Aviation Safety Agency, 2015).

Regarding the personnel requirements, the CAMO staff has to be appropriately qualified for the expected work carried out in the department. The nominated post holder supervising and managing the airworthiness tasks and the personnel overseeing the compliance of organisation with Part M Sub part G have to demonstrate that they have the appropriate background, knowledge and experience relevant to aircraft continuing airworthiness (for more details on personnel qualifications see Appendix II). Moreover, qualification of all CAMO’s personnel has to be recorded.

Regarding the personnel approved to perform and issue airworthiness reviews for aircrafts, they must acquire at least 5 years of experience in continuing airworthiness, have an aeronautical degree or an appropriate Part 66 license, a formal aeronautical maintenance training and have to be named on a position with the appropriate responsibility. The organisation is responsible to maintain a record of all airworthiness review staff and to ensure training continuation in the field of continuing airworthiness management. However, the approval to conduct airworthiness reviews is optional. More details regarding the CAMO privilege to conduct airworthiness reviews and issue airworthiness review certificates are attached to Appendix III (European Commission, 2015b).

3.4.4 Quality system and classification of findings

For the purpose of CAMO showing continuous compliance with Part M Subpart G of Annex I, a quality system has to be implemented and a quality manager shall be designated. The responsibilities of the quality manager is to monitor the compliance of CAMO with part M and to see if the established continuing airworthiness management procedures are adequate. The quality system shall have a direct feedback system with the accountable manager. This is to insure that the corrective actions are applied where necessary. Therefore, the core objectives of the quality system is to ensure that CAMO manages the continuing airworthiness adequately and at the same time it shows continuous compliance with Annex I requirements. A fundamental component of the quality system is the independent audit process. This is an objective process and comprises from a regular sample check carried out to see if the CAMO is managing the continuing airworthiness as per the mandatory regulations and recommended standards. Additionally, the independent audit will consists of a product sample check intended to complement the requirements for airworthiness review to ensure the aircraft will continue to be airworthy and safe to operate (European Aviation Safety Agency, 2015).

Aside from the direct feedback system is the occurrence reporting mechanism through which all employees can report any difficulties encountered with CAMO’s approved procedures. Establishing such an internal mechanism to report issues will lead to the improvement of CAMO procedures. This in turn will reflect that a best practice is applied within the organisation (European Aviation Safety Agency, 2015). In the case of a licensed air carrier the quality system required under Part M Subpart G shall be an integral function of the operator’s quality system. Moreover, where the airline is approved under another Part, the quality system can be linked together with the other Part (European Commission, 2015b).

The organisation has to establish levels of findings in accordance with Part M Subpart G, Section M.A.716 and two levels can be identified. The level 1 finding indicates that the organisation is not showing compliance with Part M and there is a serious issue where the safety standards are reduced resulting in an unsafe operation of the aircraft. The level 2 finding is when there is a non-compliance with Part M and is possible that safety standards and flight safety can be lowered but not as significant as a level 1 finding. If the competent authority is carrying out an audit on the organisation and a non-compliance with Part M, the CAMO’s holder has to implement a corrective action plan and within a timeframe given by the competent authority the issue has to be rectified (European Union, 2014).

3.4.5 Documentation, record retention and continuation of approval

In respect with the approved documentation, the CAMO must ensure that data used to perform continuing airworthiness tasks is up to date. The operator has to make the maintenance data available to any contracted parties (European Commission, 2015b). Regarding storage of the records, the CAMO has to keep a detailed record comprised from all work that was performed. A list with all required documents that have to be stored in the record system by a CAMO can be found in Appendix IV. When a CAMO has the privilege to issue, renew or make recommendations for an ARC, a copy of each ARC shall be retained and stored in the record system. This similarly applies when permits to fly are issued by a CAMO. The ARC and permits to fly records have to be kept for two years after the aircraft was withdrawn permanently from service. Also, the records have to be stored in such a way that they are unlikely to be damaged, altered or robbed. In case the records are kept electronically the CAMO must ensure that a second backup copy is kept in another location and that all documents will be kept in a good condition at any point in time (European Union, 2014).

When a competent authority approves the CAMO there will be no renewal date. In other words, the approval is never expiring. However, in the circumstances that the CAMO will not comply with the Part M provisions the competent authority has the entitlement to revoke the approval. In this case, the organisation has to return the approval title back to the competent authority. Similarly, if any corrective actions proposed by the competent authority is not implemented to rectify the findings, the CAMO approval can be suspended or revoked (European Union, 2014).

3.4.6 Continuing airworthiness management tasks and CAMO privileges

As per M.A. 708 and M.A 301 from Annex I, a CAMO shall ensure that for each aircraft managed the following tasks are carried out (European Commission, 2015b):

- The pre-flight inspections are accomplished before aircraft departure.

- Any defects and damages that have the potential to affect the safe operation of the aircraft are rectified. Moreover, a Minimum Equipment List (MEL) and a Configuration Deviation List (CDL) have to be developed for each aircraft type operated.

- CAMO must establish and control a maintenance programme for the aircraft managed. If the maintenance programme is based on MSG-3 logic a reliability programme must be established. The competent authority has to approve both the maintenance and reliability programme. The CAMO has to analyse the effectiveness of the maintenance programme and consequently revise it if necessary. Based on monitoring the frequency of aircraft any defect, damage or malfunctions of parts and components the maintenance programme has to be revised where required.

- CAMO must insure that the maintenance is performed in accordance with the approved maintenance programme and an approved Part 145 organisation is accomplishing it. Also whenever is required, the operator has to bring the aircraft to an approved Part 145 organisation. Additionally, CAMO has to verify and confirm that the scheduled maintenance, replacement of life limited parts and inspection of components are properly performed. The CAMO is in charge to determine what maintenance is required, when and where the maintenance has to be performed and who can perform it to ensure the aircraft will continue to stay airworthy (European Aviation Safety Agency, 2016b).

- The CAMO must ensure that any applicable Airworthiness Directive (AD), operational directives made by the Agency which impacts the continuing airworthiness, EASA’s continuing airworthiness requirements and rectifications mandated by the competent authority in response to a safety problem finding are carried out.

- The CAMO shall ensure that modifications and repairs are carried out in accordance with approved data authorised by EASA or a Part 21 design organisation. Also, approval of any modification and repair has to be properly managed and documented.

- Maintain and administer the continuing airworthiness records and operator’s technical log.

- Insure that the mass and balance statements are accurate when comparing with the current status of the aircraft.

- CAMO has to establish an embodiment policy for non-mandatory modifications and/or inspections. Some examples of non-mandatory information are the service bulletins or any authorised information made by an approved design organisation and which is tailored to a specific aircraft.

- The operator’s CAMO has to make sure that maintenance check flights are carried out when necessary.

On top of the tasks that CAMO has to carry out, The CAMO personnel should have an acceptable level of understanding the design status [xxvii] of the aircraft operated and what maintenance is necessary to be carried out. To support a good performance of CAMO’s quality system, the aircraft type design and maintenance to be carried out should be well documented (European Aviation Safety Agency, 2016b).

An airline’s CAMO is approved under Subpart G, Section A of Annex I and has the privilege to manage the continuing airworthiness only for the aircraft listed on its approval certificate and which is also mentioned on the AOC. Moreover, the CAMO can outsource some continuing airworthiness tasks and in this case the CAMO has to make sure that the contracted organisation is working under the airline’s quality system and that the subcontracted arrangement is listed on the approval certificate. Another privilege is that the CAMO can extend an ARC issued by the competent authority or another approved CAMO. In addition, when the CAMO is registered in a EU member state it may hold the privilege of issuing and extending an ARC if the competent authority approves it in the basis of the CAMO being compliant with Part M, Subpart G, Section M.A.901 (see more details in Appendix V). Furthermore, the CAMO is entitled to issue a recommendation for airworthiness review to the competent authority of where the aircraft was registered. In addition, if a CAMO was approved to issue a permit to fly for a particular airplane, it is considered to be an entitlement of the CAMO. However, the CAMO has to satisfy the competent authority’s approved flight conditions (European Commission, 2015b).

Chapter 4

4.1 Outsourcing in aviation

Outsourcing in general has become a restructuring tool for companies looking to improve their business performance and expand their business (Mol, 2007). Usually through outsourcing the functions of a business will result in reducing operational cost and capital investment. At the same time, outsourcing decisions will help managers to leverage capabilities and resources of a company with the aim to focus on the core values of the business (Al‐kaabi, Potter, and Naim, 2007). Furthermore, the outsourcing option is also fuelled by attractive marketing offerings which promise lower prices due to cheap labour (Rosenberg, 2004). Usually this is one of the main reasons why airlines are outsourcing their maintenance. The objectives are to cut the maintenance cost which occasionally will result in significant reduction in operational costs when compared with maintenance carried out in-house (Baum Hedlund Aristei&Goldman, 2016).

In the aviation industry, airlines are outsourcing those parts of the business that are labour intensive, such as aircraft maintenance, or are identified as being a non-core activity of the business (Rosenberg, 2004). McFadden and Worrells (McFadden and Worrells, 2012) considers that outsourcing a company may increase its overall profit, however this is not risk free as the contracted organisation may underperform. For example the worst scenario for an airplane maintained by a contracted Part 145 is when the aircraft is grounded and not able to fly as its airworthy condition was not maintained. Ultimately, the airline is the one responsible to properly select external suppliers if not there is always the option to perform everything in-house.

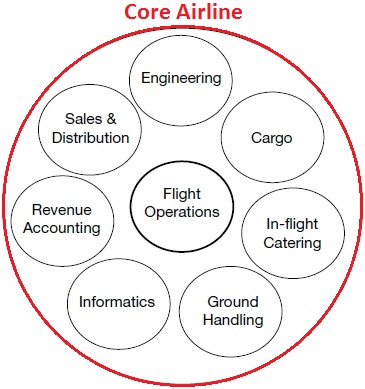

A big factor that dictates how much an airline is going to outsource is to analyse what is the airline business model. Doganis (2006) identifies three distinctive business models operated by airlines: the traditional, virtual and an aviation business model. Under a traditional business model, an airline is performing most of the functions and services in house with the aim to limit the outsourcing. An airline with a traditional model is characterized by the fact that all departments are developed in-house with the consideration that all airline’s functions are vital to manage the airline (See Fig. 4.1). After 1990s another two airline business models, virtual and pure business, have evolved. The virtual airline concept requires that an airline should focus only on its core competences and outsource those non-core functions and activities (See Fig. 4.2).

Fig. 4.1: Traditional Airline Business Model

Fig. 4.2: Virtual Airline Business Model

Source: (Doganis, 2006)

Fig. 4.3: Aviation Business Model

Source: (Doganis, 2006)

The result expected from adopting a virtual business model is to reduce unnecessary costs created by non-core activities. This business model is suitable for start-up, small airlines and low cost carriers because they can take the advantage of obtaining good deals from third party suppliers and at the same time focus only on the core activities. The alternative between the traditional and virtual business model is the aviation business model (see Fig. 4.3). An aviation business model is proposing that airlines can develop the functions as a separate business entity to operate the airline and also to offer their services to other airlines. Thus some airline functions can bring profit on its own from other airlines (Doganis, 2006).

Another criterion by which an airline decides to carry everything in house or to outsource is based on the managed fleet size. A study made by Al-kaabi et al. (2007) indicates that only airlines managing a larger fleet will have a lower level of outsourcing, around 30% to 40%. The main reason is that larger airlines have the capital to invest whereas airlines with a small fleet may not have this advantage. This is typical for start-up airlines and low cost carriers (McFadden and Worrells, 2012).

Outsourcing functions of an airline company has advantages, however it is not risk free. Selecting suppliers that will underperform might result in long turnaround times, late deliveries or even loss of aircraft reliability. Moreover, safety and quality might be on the edge if certain functions are performed under operator’s standards (McFadden and Worrells, 2012, pp. 66-7). Also, by outsourcing certain airline functions the operator will heavily rely on supplier’s performance (Al‐kaabi, Potter, and Naim, 2007). Furthermore, when outsourcing it must be taken into consideration how secure it is to share certain information with the third party suppliers. Sometimes the information shared with the contracted organisations may encourage them to become a competitor or take the advantage of passing the information to other rivals on the market (Heikkilä and Cordon, 2002). Another risk when deciding to outsource is when one of the parties might take the advantage of a loosely written contract. For example, a contract between an airline and a maintenance provider may not contain information as to what extent a non-routine maintenance task can be carried out as part of a scheduled maintenance task. Therefore, inadequate contract terms might result in a late delivery of aircraft and occasionally hidden costs incurred (Sedatole, Vrettos, and Widener, 2012). Furthermore, one of the parties may be trapped in a long term contract with no opportunity to clarify the contract (Heikkilä and Cordon, 2002, p. 186). An additional risk of outsourcing is when the business functions are contracted out but previously were performed in house. This will lower employees’ morale because some of their colleagues are to be dismissed because of business restructuring. Moreover, these actions may result in union strikes and grievances which will lower down the company’s operations and share prices (Belcourt, 2006, pp. 274-5). Therefore, by selecting a reputable supplier and keeping a good relationship with him outsourcing risks may be eliminated. Moreover, implementing certain contractual agreements between an airline and a third party might lower the risks regarding the breach of confidentiality and disputes (Belcourt, 2006).

4.2 Outsourcing an airline’s CAMO activities

4.2.1 Requirements of subcontracting continuing airworthiness tasks

Already discussed in subchapter 3.4.6, one of the CAMO’s privilege is the ability to subcontract a qualified organisation or person to manage certain continuing airworthiness tasks. A key point is that any subcontracted organisation has to be listed on CAMO’s approval certificate and that all subcontracted activities are performed under CAMO’s quality system (European Commission, 2015b). Important to realize is that the CAMO is still responsible for the management of continuing airworthiness tasks regardless of any contractual agreement between CAMO and subcontracted party. Under those circumstances, the CAMO must establish measures of active control with the purpose of monitoring the subcontracted party compliance with the relevant requirements of Part M (European Aviation Safety Agency, 2016b). As part of implementing active control measures for subcontracted tasks, the CAMO has to employ a person/group of persons that have adequate knowledge about Part M Subpart G to supervise the subcontracted party (European Aviation Safety Agency, 2016a). The procedures of maintaining an active control over the subcontracted person/organisation must be stipulated in the contract between both parties. In addition, those control measures and procedures have to be in accordance with CAMO’s practices and policies stipulated in the CAME. Therefore, in the case of subcontracting tasks to a person or to an organisation, the continuing airworthiness management system is considered to be extended to the subcontracted parties.

The subcontracted person/organisation cannot further subcontract any continuing airworthiness management task. EASA advises that there should be only one subcontracted organisation per aircraft type performing the agreed subcontracted continuing airworthiness tasks. The latter conditions will not apply to subcontracted organisations that are managing specific continuing airworthiness tasks for engines and/or auxiliary power units. Ultimately, the contract between CAMO and a subcontracted party has to be approved by the competent authority. The competent authority has the privilege to oversee the subcontracted CAMO activities through the CAMO approval. Additionally, any change in the contract between CAMO and subcontracted organisation must be acknowledged to the competent authority and consequently approved by it (European Aviation Safety Agency, 2016b).

With respect to outsourcing the continuing airworthiness tasks mentioned in subchapter 4.2.2, the CAMO’s quality system has to monitor if the subcontracted work is carried in compliance with the contract and with the Part M subpart G. Therefore, the contract between CAMO and subcontracted party shall include certain conditions which allow CAMO to carry out quality control and audits on the subcontracted organisation. The primary objectives of quality audits is to examine the compliance with the contract and the Subpart G of Annex I. Also, quality audits will provide a measure to see how effective the subcontracted tasks are carried out. Where necessary, the audits carried out by CAMO’s quality department can be reviewed by the competent authority (European Aviation Safety Agency, 2016a).

4.2.2 What a CAMO can outsource and typical subcontracting arrangements

To retain the ultimate responsibility the CAMO department has to limit the subcontracted tasks. Therefore as an acceptable means of compliance the CAMO can only outsource the following tasks as per AMC M.A.711(a)(3) of Annex I (European Aviation Safety Agency, 2016b):

- Airworthiness Directives (ADs) analysis and planning;

- SBs analysis;

- Planning of maintenance;

- Maintenance programme development and amendments;

- Engine health monitoring and reliability monitoring;

- Any other activities which do not limit the CAMO responsibilities, as agreed by the competent authority.

Choosing to subcontract Airworthiness Directives

The AD planning and follow-up may be subcontracted to an organisation, however the AD embodiment can only be performed by an approved Part 145 organisation. The CAMO responsibility is to make sure that the embodiment of any mandatory AD is done within the timeframe specified in the AD, and that notification of compliance is provided. Also, by having clear policies and procedures on AD embodiment CAMO will show compliance with EASA’s AMC. When outsourcing the analysis and planning of ADs, the CAMO has to establish procedures on what information has to be shared with the subcontracted party. To illustrate this, the subcontracted party may need access to ADs publications, to continuing airworthiness records and the aircraft/engines flight hours and cycles. On the other hand, the CAMO shall implement procedures on what kind of information the subcontractor has to provide. For example, the CAMO may need the AD planning list and detailed engineering order (European Aviation Safety Agency, 2016a).

Subcontracting analysis of Service Bulletins