Is Poor Parenting the Main Cause for Youth Criminality?

Info: 9719 words (39 pages) Dissertation

Published: 4th Oct 2021

Tagged: Criminology

Contents

Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………… page 2

Research Methodology………………………………………………………………….…page 4

Chapter 1…………………………….………………………………………………….… page 6

Chapter 2…………………………….………………………………………………….… page 12

Chapter 3……………………………………………………………………………….…. page 18

Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………page 23

References…………………………………………………………………………………page 24

Introduction: Deviant or Unlucky?

Schedule 21 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 states that the starting point for determining the minimum sentence where the offender is under 18 years of age is 12 years (UK Government, 2003). This therefore means that an individual not even considered a teenager can be punished similarly to that of an adult. England and Wales have particularly high rates of youth custody, second in absolute number only to Turkey (Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics, 2009). After a period of higher levels around the turn of the century, the overall juvenile prison population in 2011 was close to the level of the early 1990s (National Centre for Juvenile Justice, 2005). But, a study by the University of Cambridge found that less than 4% of youths are responsible for nearly half of all youth crime committed. 16% of the 700 teenagers studied admitted to having poor moral sense and self-control and were responsible in committing 60% of all the recorded crimes (The Independent, 2012). So, how do we tackle the extent of deviant acts this small percentage of youths commit? Professor Per-Olof Wikstrom, who led the Cambridge study, stated:

“We need to focus on developing policies that affect children and young people’s moral education and cognitive nurturing – which aids the development of greater self-control”

This therefore suggests that the individual factors which are the sparks for youth criminality must be identified, examined and dealt with to halt the extent of crime committed by adolescents. This would perhaps have a positive effect on the rates of reoffending by individuals whose problems are dealt with in the early stages of their life. There are varying factors which are to blame for youth criminality, some of which deemed more believable than others. Poor parenting is discussed as being the main cause for youth criminality as it ‘fuels rise in violent behaviour’ (BBC News, 2012) – but it is not due to only this factor alone.

To conclude that poor parenting is the main cause for youth criminality, we must first examine the extent to which others do so also. After researching many supposed reasoning’s behind the cause of youth deviance I picked proposals that I believed could be the best reasons as to why young people commit crime. So, Chapter One will therefore examine the extent to which poor parenting, poverty and genetics influence youth criminality in the UK and other respective countries.

Research Methodology

In writing this dissertation, I used several methods of research, both primary and secondary to gather relevant information. Most of the research I conducted was successful however I did face a few issues which impacted on how easy gathering some of the information was. One way I conducted primary research was through participating in a group semi structured interview with MSP and former Justice Community Member, Fulton MacGregor. I was able to ask questions for my research and clarify points by asking follow up questions based on his answer. This helped to further develop my hypothesis as he provided useful information and he was a reliable source due to his previous experience which related to my dissertation. However, Mr MacGregor may have potential bias due to representing the governing party in Scotland and so may have provided answers which were in favour of the SNP party’s views. However overall his views seemed to fit what I had read in other sources and so I considered what he had to say quite trustworthy. If I were to alter anything about this method of gathering information, I would have used more specific questions to gather better quality information.

My second method used was through secondary research. I acquired a Government source on “Youth Justice Statistics, 2015/16 in England and Wales”[1] as it was an official source which provided reliable information to base an argument on. Most of the source was useful to my research as it provided relevant information which was at hand to use, furthermore it was an up to date source. It was informative and showed trends and patterns between different groups in relation to crime and covered large populations which further ensured reliability. However, the source excluded Scotland and Northern Ireland and so means that judgements made didn’t include the whole of the UK which perhaps would have been different due to crime levels in Scotland. Furthermore, information could have been left out to make crime levels seem more positively in that figures are better than previous years. However, as this is a Government source I believe that it is largely trustworthy. If I were to change anything about this method of gathering information I would have used an even more up to date Government source which would have furthered strengthened my argument overall.

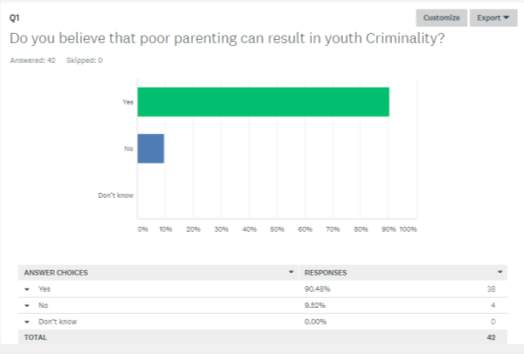

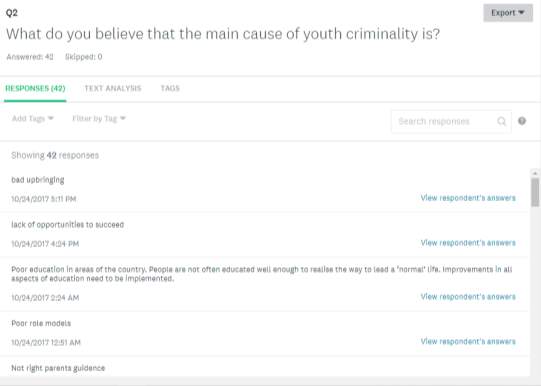

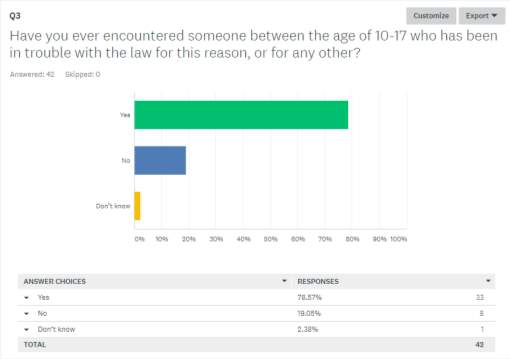

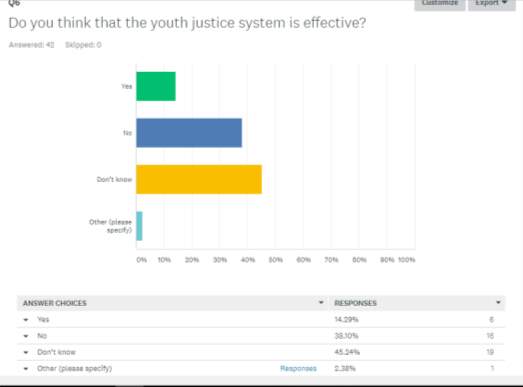

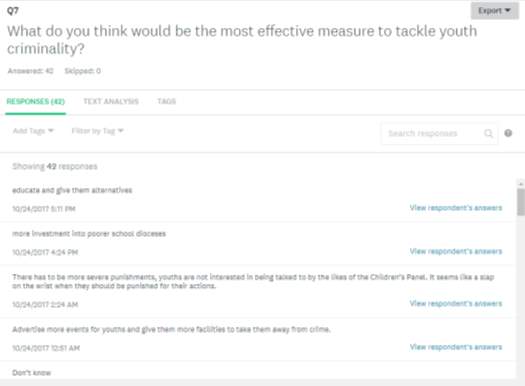

I also conducted my own survey on ‘survey monkey’[2] which helped me gain insight into the publics viewpoints on my topic[3]. I feel as though my questions would have been easier for another researcher to repeat and so were reliable. My survey used mostly closed questions to get results which would be easiest to quantify but limited potential answers from respondents. Although I feel as though my questions covered most of the topic and were well thought out which helped with my research. If I were to do anything differently I would have attempted to set up face to face interviews with family/ friends to increase my response rate as less than half of the free responses available responded. Furthermore, although this method helped my argument I found using secondary sources to be much more helpful. However, this method gave me a chance to find out both teenagers and adults opinions on a topic would could easily apply to them.

Poor Parenting – Are our Parents to Blame?

In the year ending 2016, there were 88,600 arrests of young people (aged 10-17) in England and Wales (UK Government, 2016). A considerable 64% of these young people were males aged 15 and over. An undoubtable question in relation to these arrests is the reasons why these crimes took place. Laurence Steinberg, an American Professor of Psychology, noted that:

“parental engagement in the children’s lives is one of the most important…contributors to children’s healthy psychological development… adolescents whose parents are not sufficiently engaged in their lives are more likely to get into trouble than are other youngsters”.

Therefore, does this mean that a lack of adequate parenting triggers criminalistic behaviour within all adolescents? Steinberg then clarifies his opinion, stating that poor parenting is a risk factor, not a probable cause of juvenile delinquency (Steinberg, 2000)- but some methods of ‘negative parenting’ can itself be considered a crime. For example, child abuse; there were almost 58,000 children needing protection in 2016 in the UK[4], and abandonment, in which parents leave their children with the intention of severing the parent-child relationship – this can then lead to a self-destructive future. Fewer than 1% of all children in England are in care but looked after children make up for 33% of boys and 61% of girls in custody[5]. It is believed that the absence of fathers from a child’s upbringing is a main cause for youth criminality (Department of Justice, 1992). In fact, boys who don’t have a father figure from birth are three times more likely to go to prison as those from nuclear families[6] and along with the increased likelihood of family poverty and higher risk of delinquency, a father’s absence is associated with a number of other issues. The most prominent effects being greater levels of illegitimate parenting in teenage years and greater levels of welfare dependency (Journal of Research on Adolescence, 2004).

As with fathers, mothers also have considerable influence upon their child with the early experience of intense maternal affection, which is the basis for the development of a conscience and moral compassion for others (The Heritage Foundation, 1994). If a child’s emotional attachment to their mother is disrupted, permanent harm can be done to the child’s capacity for emotional attachment to people throughout their life. Severe maternal deprivation is a critical ingredient of juvenile delinquency as the child’s first experience within a ‘community’ is rejected – which sets the stage for social tragedy. Ronald Simons, Professor of Sociology at Iowa State University, states:

“Parental rejection… increased the probability of a youth’s involvement in a deviant peer group, reliance upon an avoidant coping style, and use of substances.” (Family Relations, 1989)

Clearly, bonding between parent and child is critical in helping to protect against youth violence (Journal of Marriage and Family, 2005). Neglectful Parenting, as referred to by Laurence Steinberg, is where the child’s parents are largely absent from their life, including both physical and emotional neglect. This, in turn can lead to: poor self-esteem, poor self-control, and increase the likelihood of truancy and delinquency during adolescence (Santrock, 2012). As a result, the child receives almost no guide or structure from his or her own parents which may be due to many factors such as, drug use/ alcoholism or incarceration. A young person may in turn seek guide from the wrong outlets. These can include social media, negative peer pressure and even the compromisation of the child’s own mental health status. As part of my primary research I had to opportunity to take part in a group semi- structured interview with Fulton MacGregor, MSP for Coatbridge and Chryston on the 10/10/17, who has previous experience as a Justice Community Member. When questioned ‘During your 12 years as a social worker, how much do you believe the impact of a family can have on an adolescent and their participation in crime?’, MacGregor replied, stating that ‘It is a definite factor in relation crime’. He then went on to state; ‘I have had many (male) parents in asking about crime and how to keep their children out of it’. This therefore furthers the idea of many parents realising how available crime is for their child and acting upon it so that they do not fall into a life of crime (that perhaps the parent did before).

In relation to incarcerated parents, in 2007, over 1.5 million children in the USA had a father in prison, and over 147,000 children had a mother in prison (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2008). Violent youth are more likely to witness abuse between their parents (Criminology 24, 1986). Moreover, as parents are key role models in a young person’s life they are likely to mimic the behaviors they see from their parents, including negative and criminal behaviour. They also are more likely to commit serious violent crime and therefore become “versatile” criminals – those actively involved in a variety of crimes, for example, theft, drugs, and fraud (Clinical Psychology Review, 1990). Clearly children are the true victims of their parent’s choices and actions – some of which have a detrimental effect which last a lifetime.

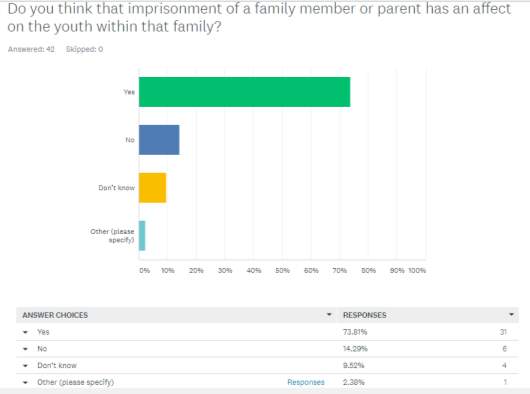

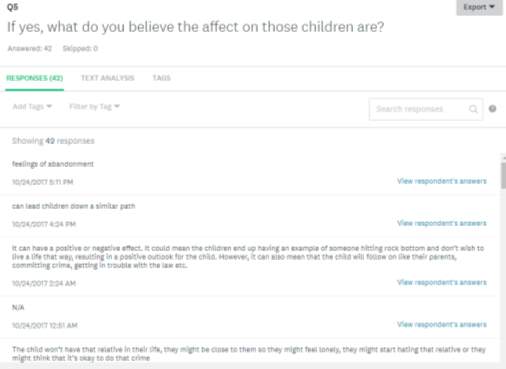

In a survey I carried out on the 23/10/17 on Survey Monkey, the results gathered further supported a link between poor parenting and crime. As to date 90% of people believe that poor parenting can result in youth criminality, with 38% of respondents believing that it is the main cause. When asked ‘What do you believe the effect of having an imprisoned family member is on the youth within that family’, there were varying replies. For example, responses included, ‘resulting in the mimicking of their parent’s behaviour’, ‘feeling alone and turning to crime as an outlet’, and ‘encouraging the adolescent to commit crime due to family life at home changing in a negative way’.

The idea of delinquency amongst children being correlated to upbringing is further highlighted by Martha Gault- Sherman, a Lecturer in Sociology and Criminology, who in the article “It’s a two-way street: The Biodirectional Relationship Between Parenting and Delinquency” found that family conflict may escalate after children become immersed in committing deviant acts (Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 2012) – the parent themselves could struggle with the emotional detachment created due to their child’s emersion in crime (Robert Karen, 1998). She found that the parent-child relationship is interactional: while a lack of parental attachment has an adverse effect on delinquency, an adolescent’s increasing delinquency contributes to the decreasing parental attachment. Her findings regarding parental attachment clearly shows a distinct correlation between parenting and crime.

This conclusion drawn by Martha Gault-Sherman, suggests causes for crime amongst adolescents must also be explored elsewhere. Perhaps, there are also definite reasons as to why poor parenting may not be the lead cause for youth criminality. For example, it could be that problem behaviour instead elicits poor parenting. Results from a study carried out on 496 adolescent girls in 2006 supported the idea of female behaviour having an adverse effect on parenting as elevated externalising symptoms and substance abuse symptoms predicted a future decrease in parental support and control (Huh, David. et. al, 2006). This idea mirrors the Reciprocal Effects Model, which states that ‘parenting affects child behaviour, but also that child behaviour affects parenting’ (Sameroff, 1975). The study also stated that ‘problem behaviour is a more consistent predictor of parenting than parenting is of problem behaviour, at least for girls during middle adolescence’. Professor Frances Gardner from the Department of Social Policy and Social Work at the University of Oxford found no evidence for declining standards of parenting[7] – and that this factor alone does not explain the rise in problem behaviour[8].

Furthermore, the blame of problem behaviour on poor parenting is also viewed as being outdated by some critics. The same study found that parents are more likely to know where their children are than their 1980’s equivalents as the proportion of parents enquiring as to what their children are doing has increased from 47% in 1986 to 66% in 2006 (ibid). This is widely due to developments in technology with the availability of mobiles and tracking applications they can monitor with. Gardner followed this by stating:

‘Today’s parents have had to develop skills that are significantly different and arguably more complex than 25 years ago’.

So, perhaps parents are still adapting to new ways in which their child can commit deviant acts, meaning that many could be actively attempting to control their child but still fall victim to the age old ‘culture of blame’[9]. This is where the parent is blamed for the actions of their child, or when criminals blame their crimes on their upbringing/ childhood experience, instead of placing themselves solely responsible for their actions. This is also known as a ‘neutralisation technique’ in that an individual who has committed an illegitimate act may engage in the process of neutralising of certain values that may otherwise prevent them from committing those acts (Whyte. David, 2016)

Judith Rich Harris, an American psychologist, writing in Prospect magazine stated that

‘the type of home in which a child is raised has comparatively little impact on how they will grow up’.

Moreover, identical twins who grow up in the same home with the same parents turn out about 45% the same and 55% different (Tellegen, A, et. al, 1988). This therefore suggests that parents’ parenting methods do not play the key role in shaping an individual’s permanent personality traits. So, can the quality of parenting really be placed to blame for youth criminality?

It is evident that from the issues that have been analysed in Chapter One that poor parenting is arguably a prevalent cause of deviance amongst adolescents. Clearly, youth criminality is prevalent throughout the UK, and has been an ongoing issue that authorities are still attempting to address.

The idea of ‘poor parenting’ can be deemed an umbrella term due to the many factors which can be encompassed by it. This can therefore lead to a higher chance of a form of poor parenting taking place within the household that can therefore lead to an adolescent following a life of crime. However, clearly there is evidence available that provides a strong argument against poor parenting being the main perpetrator for the incidence of youth crime due to for example, reciprocal relationships and the culture of blame, which both are valid opinions which question previous arguments presented.

Chapter Two will further explore causes for youth crime in the UK and other respective countries, and as with Chapter One, question the validity of the argument presented with the question of whether poverty could be argued to have a larger impact on causing youth deviance.

Poverty

An uncomfortable truth for our modern society is that there are currently over 3.7 million children living in poverty in the UK, with 1.7 million being deemed to be in severe poverty. This is defined by the United Nations as:

“a condition characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education and information.” (United Nations, 1995)

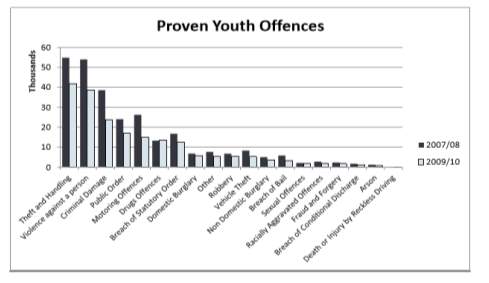

The rates of poverty in Britain amongst children are due to several factors, such as geographic location, a lack of educational prospects and parent’s financial status. These can undeniably lead to an adolescent committing offences. The Home Office reported that youth criminals committed around a fifth of shoplifting crimes, violent crimes and sex crimes in 2009/10[10]. The report concluded: ‘The youth crime estimate produced here reinforces the significance of tackling crime by young people in reducing crime overall.’ [11]Actions that young people may take due to their own individual circumstance may perhaps mean that the alleviation of poverty is where tacking this issue should begin, as it would offer one of the best way of reducing offending.

Many children are deprived of necessities in life. This in turn may lead to crime that can be due to jealously of their more affluent peer’s possessions or even be a desperate attempt to gain materials they simply need to get by.

Fig 1. – Table outlining the types of crimes committed by 10-17-year olds between 2007-2009 in the UK.

Professors Lesley McAra and Susan McVie of Edinburgh University believe that violence is part of the identity of poor young people (Youth Crime and Justice,2010). For some, a life of crime may be what is familiar, due to being part of deviant peer groups, better known as gangs, who may thrive in the deprived area of which they live. This therefore spirals into cases of peer pressure – often leading to crime. It was estimated that there were 170 gangs in Glasgow, with 3,500 gang members aged as young as 11 in 2008[12]. This is hardly surprising as Glasgow remains the most deprived city and local authority area in Scotland as almost half (47.3%) of Glasgow’s residents – 283,000 people – reside in the 20% of most deprived areas in Scotland[13].

The Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions and Crime, a study which has followed the lives of 4,300 children as they made the change from childhood to adulthood reported negative effects from formal engagement with the criminal justice system – the “labelling” effect[14]. The Professors involved in the study found that poverty in fact did have a significant effect on a young person’s likelihood to be associated with violence at 15, even after taking other factors into account which may already be suspected to influence violent behavior. For example, poor family functioning, lack of school attachment and a range of protective factors that are known to act as a preventative such as having a strong positive relationship with parents. Researchers found that young people deemed as “low risk” but were from a poorer background had a higher likelihood of engaging in crime[15]. This suggests that for certain types of young people, living in a poor household increases their risk of engaging in violence as poor teenagers are more likely to be charged by the police than those who are deemed more affluent. This relates to Robert K Merton’s Theory (1966) ‘Institutionalised Means and Cultural Goals’ in that an individual from an impoverished background may commit crime as they cannot achieve their cultural goals through legitimate, law abiding ways, and so reject institutionalised means by rebellion instead. This theory also applies to people who are not impoverished as their goals may be too unrealistic for even a semi wealthy individual to acquire and so can therefore lead to crime. The Professors conclude that “the youth and adult criminal justice systems appear to punish the poor and reproduce the very conditions that entrench people in poverty and make violence more likely” (Youth Crime and Justice,2010).

There is minimal evidence available which proves the claim that that youth crime is in fact not due to poverty. Although poverty is a source of street crime and breeds alienation from social institutions – it is not a definitive factor as to whether an individual will follow a life of crime. Futhermore, a study carried out by Cambridge’s Institute of Criminology – ‘The Peterborough Adolescent and Young Development’ concluded that children commit crime because they lack moral compass – not because of the social background/ environment they are from[16]. The research found that teenagers who avoided crime did so not because they feared persecution, but because they saw it as wrong (ibid). Instead, materialism is the root cause of crime[17]. Young people commit crime because the media has continually saturated them with the message that the goal of life is sensual pleasure, and that success in life depends on the acquisition of those objects that make such sensual pleasure possible – this does not only apply to those who stem from poverty.

Furthermore, it can be argued that people who do not reside in poverty are instead affected by crime, depending on the people they associate themselves with. This can be exemplified by the case of James Bulger (aged 2) who was murdered by Robert Thompson and Jon Venables, (both 10 years of age) in 1993. Both boys grew up in situations which had both striking similarities and drastic differences – being at very different ends of the dysfunctional spectrum. Thompson, was from what is described as an ‘appalling family’ in the care he received [18],with the NSPCC case conference reporting the children of the broken family growing up afraid of one another as they ‘bit, hammered and tortured each another’ – not helped by their lone mother who was described as an ‘incompetent alcoholic’[19]. In contrast, although separated, Venables parents attempted to bring up their child in a united way. But although he was brought up in a stable environment – it was instead Jon Venables, not Robert Thompson, who had a record of violence. This seems surprising as it was Thompsons mother who was described as the alcoholic and uncaring mother – although Thompson was the child who stemmed from poverty, it seems Venable was the leading character who had the characteristics capable of this crime – further proved by his continuation of a deviant lifestyle even after being released from prison[20] while Thompson remained anonymous. This therefore shows that perhaps children within the poverty line are influenced by the wealthier counterparts they associate themselves with and so shows that poverty is not necessarily related to crime. It seems the case children are likely to be caught up in crime and then consequently have the crime they committed based on poverty – when this could not be case at all.

Chapter Two has clearly shown that poverty is a significant cause of youth criminality in the UK. This is seen due to the rates of crime which take place in the UK’s poorest cities. Children are very susceptible to temptation and so when a child lives in poverty and has a lack of personal goods – this understandably leads the way to jealousy and temptation as they could possibly aspire to acquire assets they cannot afford, therefore leading to crime. However, it has been proven that poverty doesn’t directly link to a child committing a crime. Outside factors, such as peer pressure and social interactions can lead the way for a child who is not in poverty to be caught up in its consequences as they are influenced by those around them. Also, the poverty rates in Britain in no way show that every child in poverty is likely to commit a crime – as many grow up with the intent of becoming wealthier whereas others, such as criminals, clearly thrive in it. Therefore, poverty is not the most important factor as to why an individual commits crime.

In order to gain a more in depth understanding of the reason as to why children break the law, Chapter Three will investigate ‘genetics’ as a possible reason as to why the committing of crime takes place as perhaps it is a child’s genetic makeup which destines them to lead a life of crime, instead of the compromising choices they make on their own free will.

Genetics – Are Children Made to be Deviant?

Researchers at Oregon State University believe that genetics explain why some children thrive in their younger years while others develop behavioural problems[21]. Lead author, Dr Shannon Lipscomb, stated:

“Assuming that findings like this are replicated, we can stop worrying so much that all children will develop behavioural problems at centre-based facilities. But some children (with genetic depositions) may be better able to manage their behaviour in a different setting, in a home or smaller group size” [22]

The researchers collected data from 233 families and found that parents who had higher levels of negative emotion and poor self-control were most likely to have children who had behavioural issues[23]– this could be down to chromosomes transmitting inherited characteristics from parents to children – this was theorised by Ian Taylor, Paul Walton and Jock Young in 1973. This could be related to the first point made in that children are influenced by their parents – but perhaps their parent’s traits are instead inherited.

The researchers also studied adopted children and found a link between parent’s characteristics and their childs behaviour although they had not been brought up by them[24] – these are identical to the Hutchings and Mednick’s theory after a study carried out in Denmark which studied adopted boys found that boys who were adopted, who’s biological father had been a criminal were more likely than boys whose biological fathers were not criminals to be criminal also. This also suggests that criminality is inherited[25]. Moreover, evidence of crime being in the genes is further proved by the studies of the Kallikak and Juke families. The descendants of Ada Juke included seven murderers, sixty thieves, fifty prostitutes and several other crimes – this also indicates crime could be inherited (Carrabine. Eamonn et al. 2004). Also, in a meta-analysis researching the effect of genetics in relation to crime in 51 twin and adoption studies, the study reported a heritability estimate of 41%, with the remaining 59% being due to environmental factors (Rhee and Waldman, 2002). A study by the Institute of Criminology found that sons with criminal fathers but non-criminal mothers had a 48.5% chance of committing a serious crime throughout their lifetime[26]. If the mother was a criminal, but had a clean father, the likelihood of the son offending was 33% [27]. This relates to the impact of parents in an adolescent’s upbringing as previously discussed.

Furthermore, a study published in ‘Molecular Psychiatry’ has found a link between two specific genes and a person’s tendency to commit a violent crime. According to the research, which was led by the Karolinska Institute in Sweden and examined patterns of criminal behavior and genetics in the Finnish population, the two genes – MAOA (better known as the ‘warrior gene’) and CDH13 – are present in the genomes of up to 10% of all violent offenders. In one study cited by Morley and Hall (2003), a relationship was identified between the genes in the dopaminergic pathway, ADHD, impulsivity, and violent offenders[28].

Based on this abundance of evidence, it seems entirely possible that there is a genetic component to antisocial or criminal behaviour. Does this therefore mean that in fact, children are born this way? Do young offenders then deserve to be criminalised over the committing of an act they were ‘programmed’ to do? Perhaps some people are genuinely unable to conform to the laws of society. If genes truly are the root cause for crime, this could cause feelings of inferiority which may lead an adolescent to commit deviant acts which it could be argued are ‘not their fault’..

However, genes have already been proven as not being the main cause for youth deviance due to the factors previously discussed. Historically, many theories of gene related crime have been discredited and deemed outdated. Cesare Lombroso, who was an Italian physician and criminologist and worked previously in prisons, thought that criminals could be identified by their physical features[29]. For example, high cheekbones, large jaws and insensitivity to pain. However, these claims have been deemed ‘unscientific’ due to the simple observations that were made, no robust modern science was used and the research could be deemed biased due to the fact only criminals were used in the study[30].

Crime is considered to result from a plethora of combined factors such as geographical, social and economic factors – not genes alone (Carrabine. Eamonn et al. 2004). In relation to genes when discussing crime, Brett Haberstick from the University of Colorado stated that it is ‘vital that environmental influences are considered as well’. This therefore furthers the idea that genes alone do not create a criminal but rather the environment around them influences them to follow a life of crime. Jan Schnupp, University of Oxford, commented that half the population could have ‘bad’ genes and stated, ‘to call these alleles ‘genes for violence, would therefore be a massive exaggeration … (genes) do not predetermine you for a life of crime’[31]. This therefore indicates that violence and criminality is not inherited and does not pre-decide whether a child will grow up to lead a criminal life.

Research in the debate between genetic and environmental influences on criminal behaviour must consider the age of the individual. Studies shows that for children and adolescents the environment is the most significant factor in influencing their behaviour in contrast to heritability (Rhee & Waldman, 2002). Adults, in theory, have greater choice of the environment they chose to live in and this will either positively or negatively reinforce their personality traits, for example, aggressiveness. However, children and adolescents are limited to the extent of choosing the environment they live in, which accounts for the greater influence of environmental factors in childhood behaviour, instead of genes. There are also many factors which could explain the assumptions made behind the link between the MAOA gene and criminal behavior due to the fact very different types of behavior could be defined as antisocial, aggressive or violent.

Another environmental factor in the development of delinquent behaviour in adolescence is friend groups as (Garnefski and Okma, 1996) state that there is a correlation between the involvement in a delinquent peer group and crime. One of the main reasons as to why this occurs can be traced back to aggressive behaviour in young children. When children are in early education and are repeatedly violent towards their peers, they will likely be made an outcast. This births poor peer relationships and leads those children to be with others who share similar behaviours. This kind of relationship would likely continue into adolescence and perhaps further into adulthood. The tendencies of these individuals create an environment where they influence one another and push the problem towards criminal or violent behaviour – creating a never-ending circle of crime (Holmes et al., 2001)[32].

Overall, this therefore questions the idea of genes truly being the predominant cause for crime amongst children due to the factors which create a strong counter argument, with environmental and peer influences clearly being very influential in the possibility of a child committing crime. Although strong arguments have been made through studies carried out and genes identified which have been suspected to play a role in crime, and have been thoroughly tested by professionals who believe this is the case there has simply not been enough research to justify its merit in being the leading cause for crime – although this may change in years to come as more studies are carried out. Thus, despite the fact some studies suggest genetics may have some influence in determining criminal behaviour, arguably genes do not seem to play a significant role in being a leading factor in this argument.

Conclusion

Clearly, the UK faces ongoing challenges over youth criminality and the causes of it. There are several reasons as to why children commit crime in our modern society and number of measures which are in place to prevent it, for example, child protection services and hearings which are available to support young individuals who have chosen a troubled path[33]. With poor parenting, poverty and genetics being identified as what research has suggested to be some of the main factors which are to blame for youth criminality, overall evidence has shown that poor parenting, is in-fact the main cause.

The abundance of evidence available paints a clear picture of deviance coming to light in a child due to their socioeconomic position, methods of upbringing and the nature of their parents in relation to their criminal past– these points have all been proven to play a role in youth crime.

Firstly, genetics are thought to cause youth crime but this idea is discredited from the lack of evidence available From thoroughly researching and analysing these factors alone an abundance of evidence shows overall that from these 3 factors, poor parenting is the most prevalent causing of crime.

References

Carrabine. Eamonn; Iganski. Paul; Lee. Maggy; South. Nigel; Plummer. Ken & Turton. Jackie, (2004), ‘Criminology: A Sociological Introduction. Routlegde, University of Essex,UK, 259-262. (cited 23/02/18)

Chris Knoester and Dana L. Haynie, 2005, “Community Context, Social Integration into Family, and Youth Violence,” Journal of Marriage and Family 67, no. 3, Ohio USA, Ohio State University, 767-780. (cited 07/12/17)

Cynthia C. Harper and Sara S. McLanahan, 2004, “Father Absence and Youth Incarceration,” Journal of Research on Adolescence volume 14, University of California USA, 369-397. (cited 19/10/17)

David Huh, Jennifer Tristan, Emily Wade and Eric Stice. 2006, ‘Does Problem Behaviour Elicit Poor Parenting?: A Prospective Study of Adolescent Girls’ University of Texas, Austin, US. 21(2): 185–204. (cited 14/09/17)

Fagan. Patrick.F, 1994, “Rising Illegitimacy, America’s Social Catastrophe.” The Heritage Foundation: Washington D.C, USA (cited 23/10/17)

Garnefski, N., & Okma, S. (1996). “Addiction-risk and aggressive/criminal behavior in adolescence: Influence of family, school, and peers”. Journal of Adolescence, 19, 503-512. University of Leiden, The Netherlands. (cited 14/12/17)

Holmes, S. E., Slaughter, J. R., & Kashani, J. (2001). “Risk factors in childhood that lead to the development of conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder”. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, Kluwer Academic Publishers-Plenum Publishers. 31, 183-193. (cited 17/11/17)

Karen. Robert, 1998, “Becoming Attached; First Relationships” Oxford University Press Inc, New York, US. 314-325. (cited 18/09/17)

Kevin N. Wright and Karen E. Wright, 1992, “Family Life and Delinquency and Crime: A Policymaker’s Guide to the Literature,” prepared under interagency agreement between the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention and the Bureau of Justice Assistance of the U.S. Department of Justice. (cited 1/11/17)

Kruttschmitt, Candace. Heath, Linda. & Ward, David A. 1984, “Family Violence, Television View Habits and Other Adolescent Experiences Related to Violent Criminal Behavior,” Criminology 24, 235-267. (cited 29/12/17) http://www.marripedia.org/effects_of_parents_on_crime_rates

Lauren Glaze and Laura Maruschak, 2008, Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics). (cited 17/10/17)

Marcelo F. Aebi and Natalia Delgrande, Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics – 2009, Table 2, http://www3.unil.ch/wpmu/space/files/2011/02/SPACE-1_2009_English2.pdf (cited 12/09/17)

Martha Gault Sherman, 2012, “It’s a two-way street: The Biodirectional Relationship Between Parenting and Delinquency”, Journal of Youth and Adolescence, Cengage Learning, 41:121-145 (cited 14/09/17)

Morley, K., & Hall, W. (2003). Is there a genetic susceptibility to engage in criminal acts? Australian Institute of Criminology: Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. 263, 1-6. (cited 14/03/18)

National Center for Juvenile Justice, State Profiles, Juvenile Transfer Laws, http://www.ncjj.org/Research_Resources/State_Profiles.aspx (cited 25/10/17)

Rhee, S. H. and Waldman, I. D. (2002). Genetic and environmental influences on antisocial behavior: a meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychological Bulletin.

Department of Psychology, Emory University, USA.128: 490–529. (cited 15/10/17)

Rolf Loeber, 1990, “Development and Risk Factors of Juvenile Antisocial Behavior and Delinquency,” Clinical Psychology Review 10, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, USA 1-41. (cited 28/01/18)

Ronald L. Simons and Joan F. Robertson, 1989, “The Impact of Parenting Factors, Deviant Peers, and Coping Style Upon Adolescent Drug Use,” Family Relations 38, The Heritage Foundation, US. 273-281. (cited 17/11/17)

Sameroff A. ‘Early influences on development: Fact or fancy?’ Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1975;21:263–294. (cited 17/11/17)

Santrock, John W. (2012). A topical approach to lifespan development (6th Ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. (cited 13/03/18)

See reference to Ann Goetting, “Patterns of Homicide Among Children,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 35, no. 1 (1989): 31-44. (cited 22/09/17)

Steinberg, Laurence. (2000). Youth violence: do parents and families make a difference? National Institute of Justice Journal, 31-38 (cited 24/09/17)

https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/jr000243f.pdf (cited 24/09/18)

Tellegen, A., Lykken, D. T., Bouchard, T. J., Wilcox, K. J., Segal, N. L., & Rich, S. (1988). Personality similarity in twins reared apart and together. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1031–1039. (cited 16/10/17)

United Nations. “Report of the World Summit for Social Development”, March 6–12, 1995. (cited 05/09/17)

Whyte. David, 2016 ‘It’s common sense, stupid! Corporate crime and techniques of neutralization in the automobile industry’ University of Liverpool, Bedford, UK. 66:165-181 (cited 14/01/18)

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/44/schedule/21 (cited 14/09/17)

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/the-16-year-olds-who-have-committed-86-crimes-each-7878741.html (cited 14/09/17)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-17553210 (cited 14/09/17)

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/585897/youth-justice-statistics-2015-2016.pdf (cited 14/12/17)

http://www.randywithers.com/how-bad-parenting-can-turn-a-child-into-a-juvenile-delinquent/ (cited 03/03/18)

http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/morality-prevents-crime (cited 25/02/18)

https://thf_media.s3.amazonaws.com/1995/pdf/bg1026.pdf (cited 02/04/18)

http://www.academia.edu/6761207/Youth_crime_and_justice_Key_messages_from_the_Edinburgh_Study_of_Youth_Transitions_and_Crime (cited 01/04/18)

http://www.civitas.org.uk/content/files/factsheet-youthoffending.pdf (cited 23/10/17)

https://www.smh.com.au/national/parents-can-pass-criminality-on-to-children-20110509-1efw2.html (cited 02/04/18)

http://www.transformjustice.org.uk/an-uncomfortable-truth-the-strong-link-between-poverty-and-crime/ (cited 04/04/18)

http://www.smh.com.au/national/parents-can-pass-criminality-on-to-children-20110509-1efw2.html (cited 12/09/17)

https://www.government.nl/topics/youth-crime/reducing-youth-crime (cited 03/04/18)

http://www.personalityresearch.org/papers/jones.html (cited 02/09/17)

https://www.nationalreview.com/2014/11/poverty-doesnt-cause-crime-dennis-prager/ (cited 2/10/17)

https://www.nspcc.org.uk/services-and-resources/research-and-resources/statistics/

http://www.beyondyouthcustody.net/about/facts-and-stats/ (cited 04/09/17)

https://phys.org/news/2009-07-today-parents-blame-teenage-problem.html (cited 04/09/17)

https://www.empoweringparents.com/article/parenting-truth-you-are-not-to-blame-for-your-childs-behavior/ (cited 04/09/17)

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2150187/Under-18s-commit-quarter-crimes-Young-offenders-responsible-million-crimes-just-year.html (cited 26/09/17)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-15238377 (cited 9/10/17)

http://www.understandingglasgow.com/indicators/poverty/overview

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2163974/Poverty-excuse-crime-morality-biggest-factor-claims-Cambridge-University-study.html (cited 4/12/17)

http://www.personalityresearch.org/papers/jones.html (cited 01/04/18)

http://www.scienceofidentityfoundation.net/yoga-philosophy/ancient-wisdom-for-modern-living/the-root-cause-of-crime (cited 4/12/17)

http://www.transformjustice.org.uk/an-uncomfortable-truth-the-strong-link-between-poverty-and-crime/ (cited 03/04/18)

https://prezi.com/ehyozfk1druk/the-roots-of-crime/ (cited 03/04/18)

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2000/nov/01/bulger.familyandrelationships (cited 11/03/18)

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5373857/Very-different-monsters-Jon-Venables-jailed-again.html (cited 11/03/18)

http://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/news/parents-teenagers-are-doing-good-job (cited 03/04/18)

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2476935/Dont-blame-poor-parenting-tearaway-kids–bad-behaviour-childs-GENES.html (cited 13/02/18)

http://www.psychlotron.org.uk/newResources/criminological/A2_AQB_crim_biologicalTheories.pdf (cited 13/02/18)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-29760212 (cited 04/02/18)

https://www.historyextra.com/period/victorian/the-born-criminal-lombroso-and-the-origins-of-modern-criminology/ (cited 24/03/18)

https://www.surveymonkey.com/home/?ut_source=header (cited 24/10/17)

Appendix 1:

[1]https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/585897/youth-justice-statistics-2015-2016.pdf

[2] https://www.surveymonkey.com/home/?ut_source=header (See Appendix 1)

[3] See Appendix 1

[6] See reference to Ann Goetting, “Patterns of Homicide Among Children,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 35, no. 1 (1989): 31-44.

[9] https://www.empoweringparents.com/article/parenting-truth-you-are-not-to-blame-for-your-childs-behavior/

[10] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2150187/Under-18s-commit-quarter-crimes-Young-offenders-responsible-million-crimes-just-year.html

[11] ibid

[14] http://www.transformjustice.org.uk/an-uncomfortable-truth-the-strong-link-between-poverty-and-crime/

[16] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2163974/Poverty-excuse-crime-morality-biggest-factor-claims-Cambridge-University-study.html

[17] http://www.scienceofidentityfoundation.net/yoga-philosophy/ancient-wisdom-for-modern-living/the-root-cause-of-crime

[19] ibid

[20] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5373857/Very-different-monsters-Jon-Venables-jailed-again.html

[21] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2476935/Dont-blame-poor-parenting-tearaway-kids–bad-behaviour-childs-GENES.html

[22] Ibid

[24] ibid

[27] ibid

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Criminology"

Criminology is a social science that applies elements of sociology, psychology and law in the study of crime, criminal behaviour and law enforcement.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: