Practice-Based Mentoring and Coaching in Primary Schools

Info: 12533 words (50 pages) Dissertation

Published: 11th Dec 2019

Tagged: EducationYoung People

Introduction

By way of introduction, the purpose for this assignment is to critically reflect on the practice-based processes of mentoring and coaching used within a primary school context, and to evaluate the effectiveness of these processes through making connections to key literature and policies. The underlying aims of the assignment are to emphasise and reiterate the well-understood view that professional development in Education is an ‘ongoing and continuous process’ (GTCS, undated a). Through discussion and critique of gathered evidence, I wish to highlight my developing understanding of the mentoring and coaching process and how effective mentoring and coaching processes are achieved, with a focus on the key aspects of the roles, relationships and skills of the mentor and the mentee. Additionally, I will aim to discuss the impact of engagement with the mentoring and coaching process on my own professional learning currently and in the future. A study by Kwan and Lopez-Real in 2005 centres around two key questions which I intend to use as the focus of my reflective discussion:

- ‘Firstly, how do mentors perceive their roles during the mentoring process?’

- ‘Secondly, how have perceptions of their roles changed over the time they have acted as mentors?’

Extract from Kwan and Lopez-Real, 2005, pg. 275.

As a current practitioner, the standards for career-long professional learning outlined by the GTCS (2012) are at the forefront of my professional development objectives and through engagement with this course, I have strived to continually build upon and develop my knowledge and understanding in a variety of areas.

The Mentoring and Coaching Context

The mentoring and coaching processes detailed within this assignment took place within a Roman Catholic primary school in the city-centre of Aberdeen, with a pupil enrolment of approximately three-hundred and seventy and a teaching staff role of fifteen.

Periodically throughout the current school year, the school has hosted a group of fourth-year MA students from the university. Within the ethos and culture of the school, the management team strive to allow staff to meet the criteria laid out in the Catholic Schools Charter, which states that all individuals within the school must demonstrate a “commitment to support the continuing professional and spiritual development of staff” (SCES, 2016) (attached in Appendix 1). Although the traditional approach to mentor selection is based on the number of years of teaching experience accrued by an individual, other prevailing aspects such as; emotional availability, critical thinking skills and desirability can also be brought into consideration (Young et al, 2005). In addition, over the years, extensive research has been conducted into the benefits of mentoring and coaching for both the mentor, the mentee [1], the pupils and staff as a whole and as a result, many head teachers are encouraging the promotion of mentors amongst their differing levels of staff (MCR Pathways, undated; GTCS, 2016).

From a more negative standpoint however, a study by Lord et al (2008) discusses the impact of the lack of professional development courses provided for those considering undertaking mentoring and coaching roles. Bullough’s (2012) study reiterates these findings; highlighting the lack of professional development and training available, and the implications of this on the skills and knowledge developed during their ‘mentor education’. Within the context school in particular; the lack of training available resulted in a significant decrease in the number of class teachers willingly volunteering to adopt the role of a mentor. Professional dialogue occurred during a school staff meeting regarding perceived professional skills and abilities in terms of mentoring and coaching, and the general consensus regarding the student teacher process. Each member of staff was asked to complete a short evaluation slip stating whether they would be willing to have a mentee (student teacher) assigned to their class and any relevant skills or experience they could provide. The majority of the more experienced staff, in terms of the number of years taught, felt they did not have the required skills to work alongside the university in developing the student, as they were unfamiliar with the new course format and the expectations required. This notion is backed up in the paper by HMIE (2008) whose findings reiterate that head teachers often deploy the mentoring role to more inexperienced staff in order to provide opportunities for their professional development and to delegate leadership responsibilities throughout the school. Through continuous engagement with the ED50JK university course, the provision I needed to involve myself further in the life of the school was readily available. The preparation of a mentor must be made a priority by teachers, researchers and management alike (Hobson et al, 2009). I relished the opportunity to develop and hone my professional skills and abilities further and my head teacher was keen for me to explore alternate CPL (continuous professional learning) activities in order to enhance leadership opportunities.

Accordingly, a fourth year university student was allocated to four different classes by the head teacher based on the data collected, resulting in the placement of a student within my Primary 5 class, which consists of twenty-five pupils with a variety of additional support needs.

Theory into Practice

The links between formal support programmes, providing beginning teachers with mentors and coaches, and high quality teaching and learning experiences have been well documented (Hobson et al, 2009; Rippon & Martin, 2003; Nicholls, 2002). The most notable action taken from these findings was the probation year in Scotland (GTCS, undated b). Ingersoll and Strong (2011) discuss in their study the intrinsic links between the aforementioned factors and the implementation of effective mentoring techniques. Undertaking the role of a mentor or coach is viewed by many as a complex task, but both are processes that through continuous practice, can be learned and improved upon over time.

Mentoring can be performed within a variety of different contexts and for a range of purposes; such as student teachers, trainee doctors and business apprenticeships. Within these contexts, a variable approach to theoretical models and frameworks can be undertaken (Hobson et al, 2009; Dominguez & Hager, 2013). The duration and intensity of the approach is circumstantial and relies on an array of factors such as; the perceived ‘efficiency’ of the mentor and the mentee, the confidence and professional skills of those involved in the process (Strong & Baron, 2004; Ingersoll & Strong, 2011).

To begin with, throughout the eight week placement the student teacher (the mentee) and I (the mentor) engaged with a number of mentoring and coaching activities. Attached in Appendix 2, is a copy of the timeline of events undertaken throughout the context mentoring process; a variety of techniques and tools were used and intrinsic links to theoretical models and frameworks were made. Each week a PROP form was completed to show the student’s progress, and evidence for this was gathered from in-class observations, learning conversations and more formal meetings. As the placement progressed, the models and frameworks used were adapted to suit the needs of the mentee and myself as the mentor. Adaptions and changes to the procedures over the duration of the weeks have been highlighted in yellow and will be discussed later in the assignment.

The Mentoring Matters document states that “for mentoring to be successful, practitioners must be committed to improving how their pedagogy impacts on learners’ outcomes. Engaging in mentoring conversations broadens knowledge and deepens understanding of the learning and teaching process” (MCR Pathways, undated). To ensure continuity and best practice, I engaged with a range of readings, models and frameworks;the GTCS continuum, the GROW model and the CUREE framework for example.

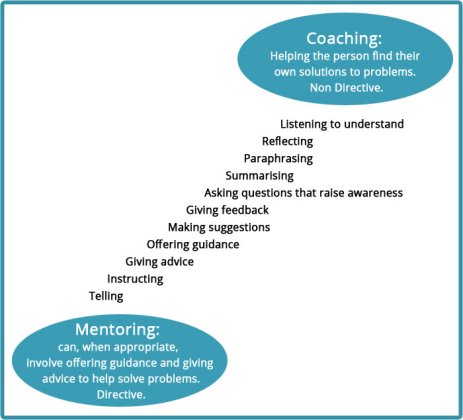

The GTCS continuum (attached in Appendix 3) was used as an initial starting point for my own mentoring process to aid critical thinking and discussion with the mentee. It is widely recommended to use a mentoring and coaching model as a means of providing support for reflections and actions and particularly, a continuum approach is recommended in literature (Pask and Joy, 2007). The GTCS model was created to highlight the potential ‘shifting’ approach of the mentor throughout the process; moving between a ‘directive’ (mentoring) and ‘non-directive’ (coaching) approach to providing support (GTCS, 2016). The model in itself, therefore, is a model for learning; for both the mentor and the mentee. Pask and Joy (2007) state that a continuum model, such as that depicted, can provide opportunities for progress through problematic issues and the ability to take actions forward, ultimately resulting in teacher autonomy. This is evidenced through Appendix 4, which shows snapshots of records of conversation collected from the first and final week of the placement and explicit links to the different areas of the GTCS continuum have been highlighted.

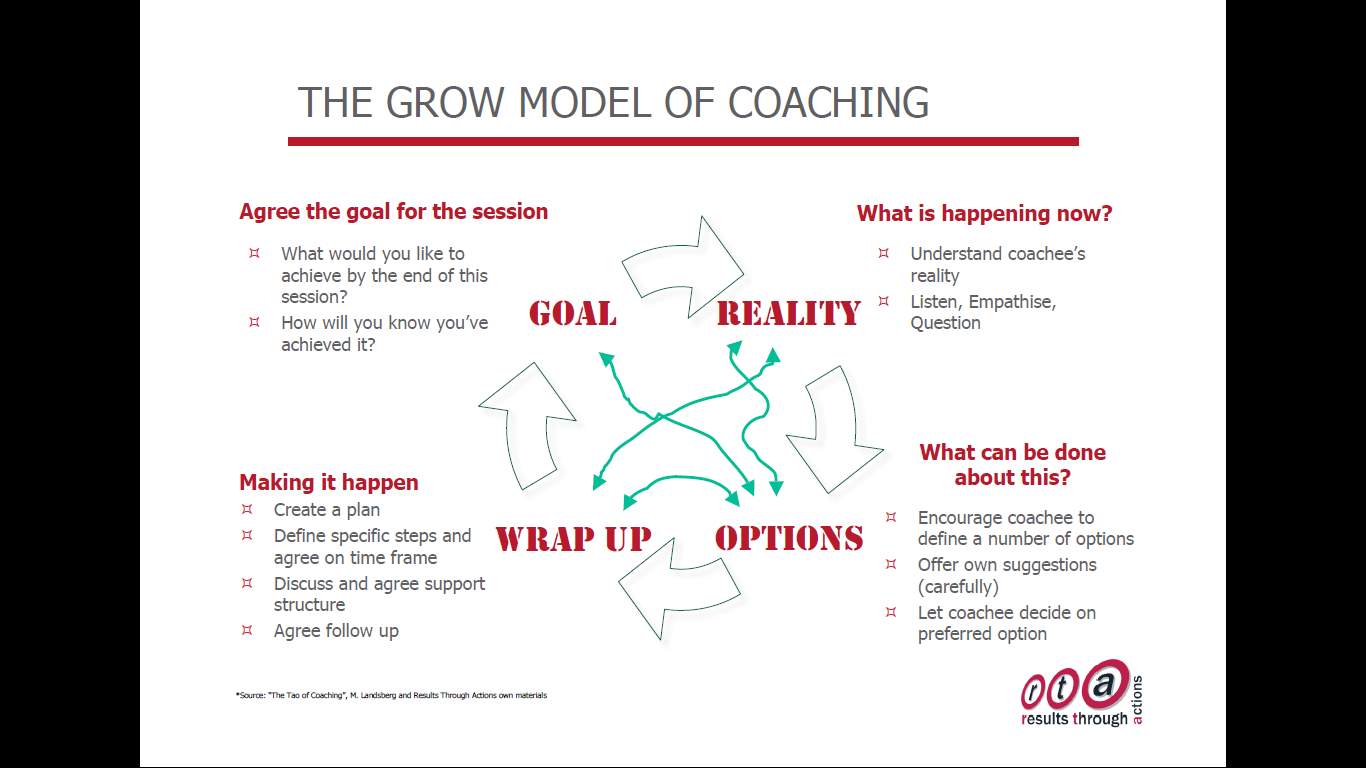

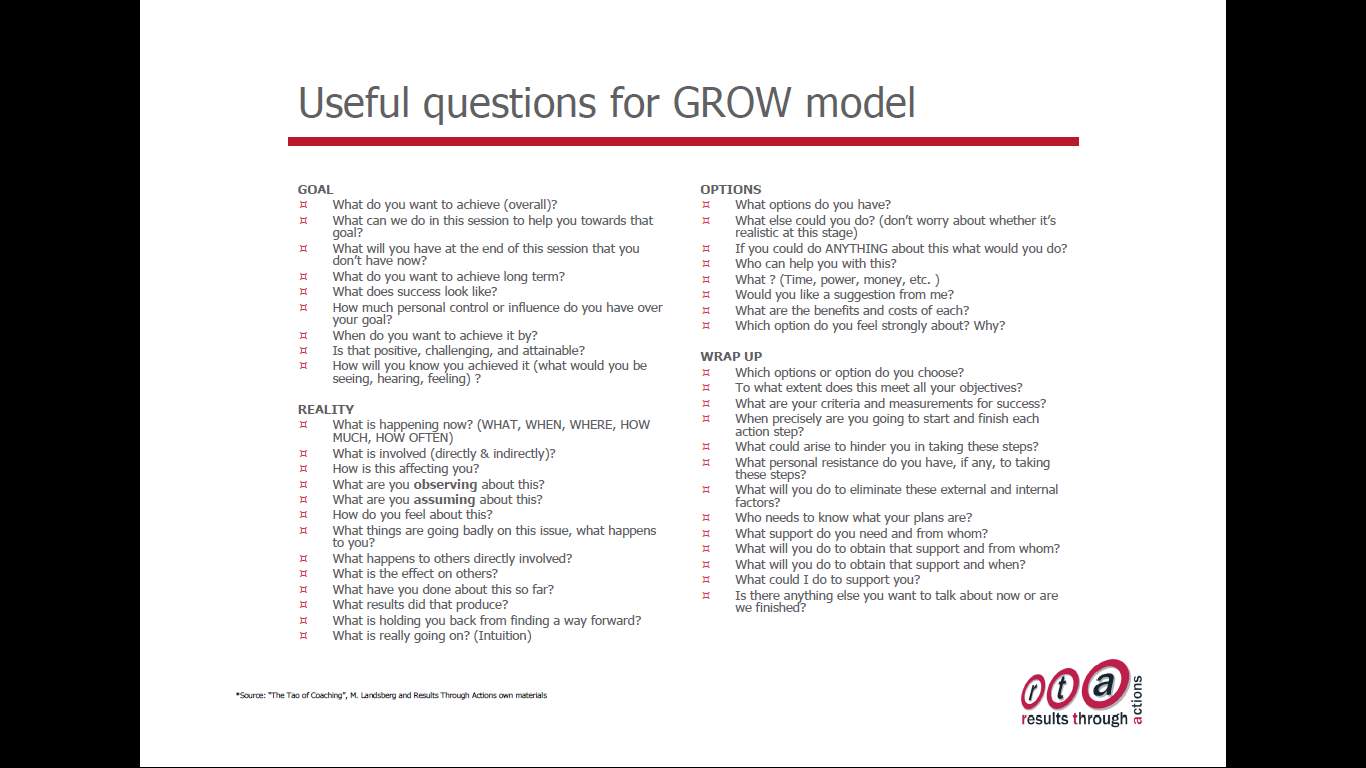

Researchers Connor and Pakora (2012, pg. 9) detail nine principles for the effective practice of mentoring and coaching, these include; ‘the coach facilitates learning and development… the outcome is change and action… the approach of model provides movement and direction’ (p9). As detailed in Appendix 2, more formal weekly meetings were conducted each Friday to discuss and record the mentee’s development through professional dialogue and completion of the PROP form and after each observation. As a beginning mentor I sought a different model to help me structure the learning conversations during these regular meetings with my mentee more appropriately, make better use of time management and move towards teacher autonomy. The EIS (2008) emphasise that research should be conducted by teachers to obtain a pertinent model or framework that is practical for their own usage. With this in mind, as the student placement progressed I opted to use the most well-known coaching model; the GROW (Goal, Reality, Options, Wrap-up) model created by John Whitmore (Grant, 2011; Dembkowshi & Eldridge, 2003) (attached in Appendix 5) to guide the learning conversations further and provide opportunities for the mentee to critically self-reflect. The GROW model allows the learners to develop and define their own professional goals, reflect on how they can reach this set goal, identify where they are currently and finally draft up and develop a professional action plan.

In addition to this, more informal learning conversations took place regularly throughout the week, usually at the end of the school day – allowing for ‘spontaneous collaboration’ between the mentee and myself. This allowed for the of use unplanned events such as small issues with behaviour management, responses from the children, new school initiatives or new planning ideas as ‘developmental tools’ to progress the student teacher further (Williams and Prestage, 2002, p.43). These conversations were not documented formally, but evidence of these discussions occurred through professional dialogue and the impact was discussed through PROP forms and evaluations.

To encompass the above discussion; Zachary (2000) examines many underlying aspects of the mentoring process such as ‘communication, goal setting, reflecting, providing and receiving feedback and problem solving’ and affirms that these aspects can be used by mentors to tie in theoretical knowledge learnt at university into student teacher practice, and improve upon their knowledge, understanding and skills of their own practice. A commonality amongst theorists is that a developmental relationship is paramount to the mentoring and coaching process; as is the use and application of models and frameworks in practice. In order for a mentoring process to be truly successful, the mentor must be flexible and adaptable in the use resources to suit the participants in question (Liljenstrand, 2003).

Effectiveness of Mentoring and Coaching in Context

The relationship between a mentor and a mentee is of the utmost importance and ultimately acts as a defining factor in the beginning teacher experience of a student teacher or probationer (Hobson, 2002; Williams and Prestage, 2002). Nicholls’ (2002) research into the key features of a mentor-mentee relationship established a dependence of the type of mentor model or preferred approaches used throughout the process. He suggests there are three main mentor models that can be adopted; apprenticeship, competency and reflective. These terms encompass the shift from a directive to a responsive approach based on the qualities and skills of the mentee; this in turn links back to the GTCS continuum and the ‘continuum’ approach to mentoring and coaching. A study by Young et al (2005) mirrored these three terms and ultimately defined them as a means of working with beginning teachers, adhering to mentor responsibilities but above all, they are a preferred ‘way of being’. Incorporated within the preferred mentoring approach of an individual are their professional values of teaching and learning, their acceptance of duties and obligations and personal beliefs with regards to respect and equality. The notion then that “teaching is a highly personalised practice of finding one’s own style” (Feiman-Nemser, 2001, p.1033) is a common thread of thinking amongst educators and throughout my own mentoring process I strived to keep this in consideration.

Studies by Darling-Hammond and Richardson (2009) and Valencia et al (2009) show that student teachers are regularly left to develop as a ‘teacher’ on their own with little guidance and limited connections made to the literature studied at university. The findings from these studies resonated with me personally as they were particularly pertinent to my own situation during my university placements. Therefore, I endeavoured to adopt a more structured and reflective approach within my own context; effort was made to provide regular support through weekly meetings and availability for discussions with the mentee, which in turn allowed for opportunities for a continuous process of reflection and planning of next steps. Hankey (2004) endorses dedicated time set for observations, meetings and professional dialogue between the two parties and the adoption of a dynamic approach; the use of a number of techniques and tools to include the mentee in their learning process. Opportunities to engage a mentee in determining the next steps in their own learning then, in particular ensuring self-reflection on their current learning context and setting achievable goals to overcome problems, can be afforded through the use of a coaching model (Trivette et al, 2009, p7). A coaching model that offers these opportunities can be described as an effective model in terms of supporting the mentee’s professional development. Concurringly, Education Scotland (undated a) maintains that the coaching process allows learners to ‘take responsibility for their development, set goals, take action and grow’. The GROW model mentioned previously was received positively by the mentee and myself alike. Feedback from the mentee has been collated and detailed in Appendix 6, confirming the positive effect of the model on the mentoring process. Comments made include a better use of time management from both parties during discussions in comparison to the less structured conversations at the beginning of the placement, using only the GTCS continuum and an increased shift in responsibility for learning. Whitmore (2004) accredits the simplistic nature of the GROW model design to having a positive effect on the mentee’s self-motivation and confidence, whilst providing a scaffold to develop the mentor/coach’s communication and intrapersonal skills. Using the GROW model, as a beginning mentor, afforded me a platform in which I could consider the wording of my questioning technique and ensure that the learning dialogue remained professional at all times.

Linking back to Young et al (undated) and the concept of mentoring as a ‘way of being’, this places high prominence on the establishment of positive relationships in order to form an effective mentoring process. A study by HMIE (2008) observed that, overall, NQTs (newly qualified teachers) embraced the mentoring process and were appreciative of the feedback, lesson observations and target setting from their mentors, viewing the process as a key element to improving their professional practice. Opportunities for an accelerated rate of learning, an increase in confidence and improved communication skills are some of the many benefits associated with this positive relationship (Ingersoll and Strong, 2011).

On the other hand, there can be considerable variability in how the mentee responds to the mentoring process and the mentor themselves; an inconsistency in the understanding of the relationship and roles differs amongst individuals, cultures and contexts (Jones 2001; Stanulis & Russell, 2000). In contrast to my personal experiences as a student teacher, I sought to provide a balanced approach of structure whilst being open to and allowing for opportunities for self-expression and development of the mentee’s own ideas. Lindgren (2005) clearly defines the act of effective mentorship as a focussed process on the individual mentee’s needs. For this to transpire, a relationship between the mentor and mentee is fundamental (Rippon and Martin, 2003). Personality clashes, misinterpretation of the roles and responsibilities and a difference in professional and personal values can cause the mentoring process to become emotionally demanding for those involved (Bullough & Draper, 2004; Maynard, 2000). A study by Halatin and Knotts in 1982 explored the potential negative side-effects that mentors can be subjected to in terms of the time and energy demanded from a mentoring or coaching position, especially with an unprofessional or non-willing mentee.

Repeated discussions and feedback were provided at regular intervals, as discussed, to provide the mentee with support, however the impact of the mentoring process in terms of these informal and formal discussions became a slow and minimal impact process; small changes such as attempting to reflect more fully and critically and becoming more pro-active in maintaining accessible and up-to-date plans were observed in the latter half of the placement, are detailed in the summative report (shown in Appendix 7).

As the placement progressed, the student teacher placed within my class, regrettably, did not fully adhere to the ethos of the school nor did they actively or willingly take on board the majority of the feedback provided, instead choosing to substantiate their personal written reflections with inconsistencies. Evidence of this can be found in Appendix 8, which shows a collation of formative feedback from PROP forms and a formative forward planning review.

As a mentor, I felt there was a distinct lack of enthusiasm for class teaching from the mentee, waning as time progressed, and I sought alternate methods to maintain and create motivation for both the mentee and the pupils in my class. The process was frustrating for my part, connecting back to the effects of a negative mentoring experience proposed by Maynard (2000). Perhaps this feeling was due to an intrinsic feeling of a lack of preparedness to teach or a lack of motivation on the part of the mentee? Or a lack of engagement in the mentoring process?

Rhodes Offutt (1995) reviews five attributes applicable to both a successful or ‘problematic’ student teacher; self-concept, personal effectiveness, motivation, priorities and effort. Elements of the latter three attributes correlate directly to the context situation, namely;

- ‘Students may appear unconcerned about the quality of their work

- Tasks are not completed properly and work is handed in late

- Students can prioritise their social lives, above that of their placement ‘teacher’ life

- The student seems to lack the desire or ability to acquire organisational skills

- The student needs to be asked to do something, instead of taking the initiative to do it without being told’

Extract adapted from Rhodes Offutt (1995).

Housego (1990) also compiled a study discussing these elements and their impact upon the student teacher programme in general; in aspects such as motivation, record-keeping, planning and self-discipline, he alludes to the longevity of the placement field experiences as a vital component and equates this to a brief ‘survival course’. The short nature of the placement field experiences can be somewhat of a ‘shock’ for the student teacher and it can take them a number of weeks to adjust to the numerous roles and responsibilities of a class teacher. As a mentor, particularly of a student teacher, one must remember that as an Education practitioner, we are all continuously learning throughout our careers and that in Scotland, the probation year is used as a stepping stone to full registration (GTCS, undated c). Within the final summative report, using literature, frameworks and observations to guide me, I referenced the possible potential development of the mentee, opting to provide a ‘benefit of doubt’ and ensuring concise professional development targets were set and discussed for the next block of placement (shown in Appendix 9).

Differing expectations are a common component of the student teacher experience, of both the university and the placement school in a range of areas such as giving instructions and ways of teaching (Yördema and Akyolb, 2014), as evident in the previous discussion, incorporating theory into practice can be challenging. Reference to literature and key action points were detailed within the university pro-forma of PROP forms each week to enable opportunities for more succinct connections to the theories and practices studied at university, an example is attached in Appendix 10. Evidence of the impact of this approach was evident towards the end of the placement, and a more positive evaluation can be found in the summative report. Enacting the learnt teaching practices from student studies into the classroom environment can be a complex task and it is the responsibility of the more experienced other to emphasise the importance of making these connections to ensure progression (Zeichner, 2010).

On reflection, I would conclude that the mentoring techniques and approaches chosen were somewhat ineffective in terms of truly progressing and developing the mentee further. A more directive approach was assumed by myself throughout the duration of the placement as the mentee was not fulfilling the requirements to a satisfactory degree. However with hindsight perhaps the adoption of an apprenticeship approach would have been more applicable for the student in question. This would have allowed for a more scaffolded approach through an increase in regular team teaching and group work sessions for the mentee and perhaps supported her more fully during her continuous practice. Rippon and Martin (2003) suggest that “it is not enough to follow a set of guidelines and operate a timetable of scheduled meetings” (p.221), with the intention of effective professional development mentors must promote and actively encourage the use of collaborative practice; working as a successful partnership to plan opportunities for teaching and learning for all parties (Williams and Prestage, 2002, p.43).

Mentoring through Observations

A collectively renowned aspect of the student field experience is the method of observation; this traditionally occurs through a process in which a more experienced professional observes a student teaching a class and consequently creates either oral or written feedback based on a number of set criteria (Lucas, 1995). GTCS (undated b) have moved away from this style of observation and recommend using the procedure as a means of collaborative working through ‘using questions, discussions and guided activities to help… solve problems, address issues and complete tasks to a higher standard’. The GTCS (ibid.) suggests incorporating three stages in the approach to observing a teaching session;

- Pre-observation meeting (plan)

- Observation (observe)

- Post-observation meeting (feedback)

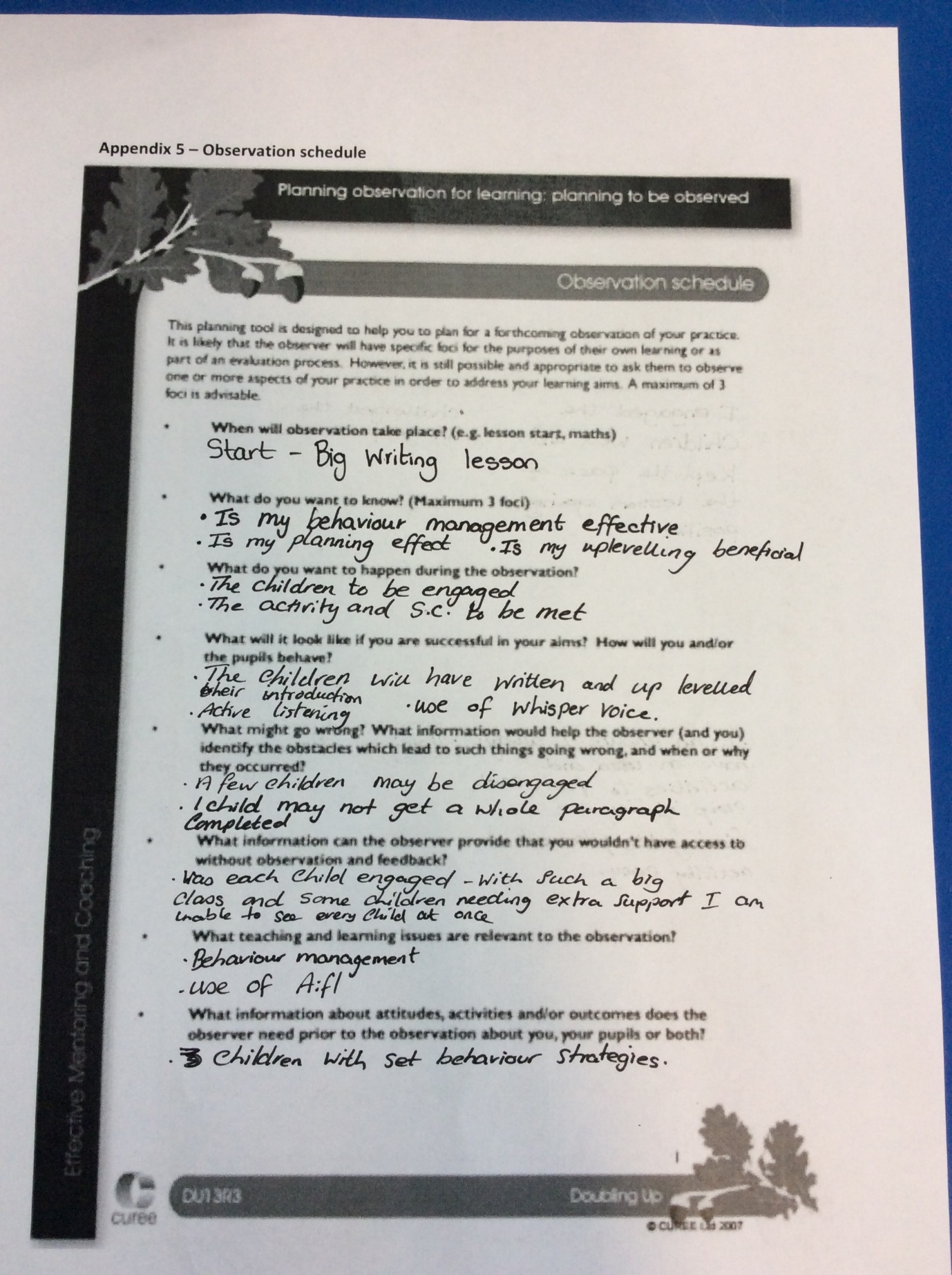

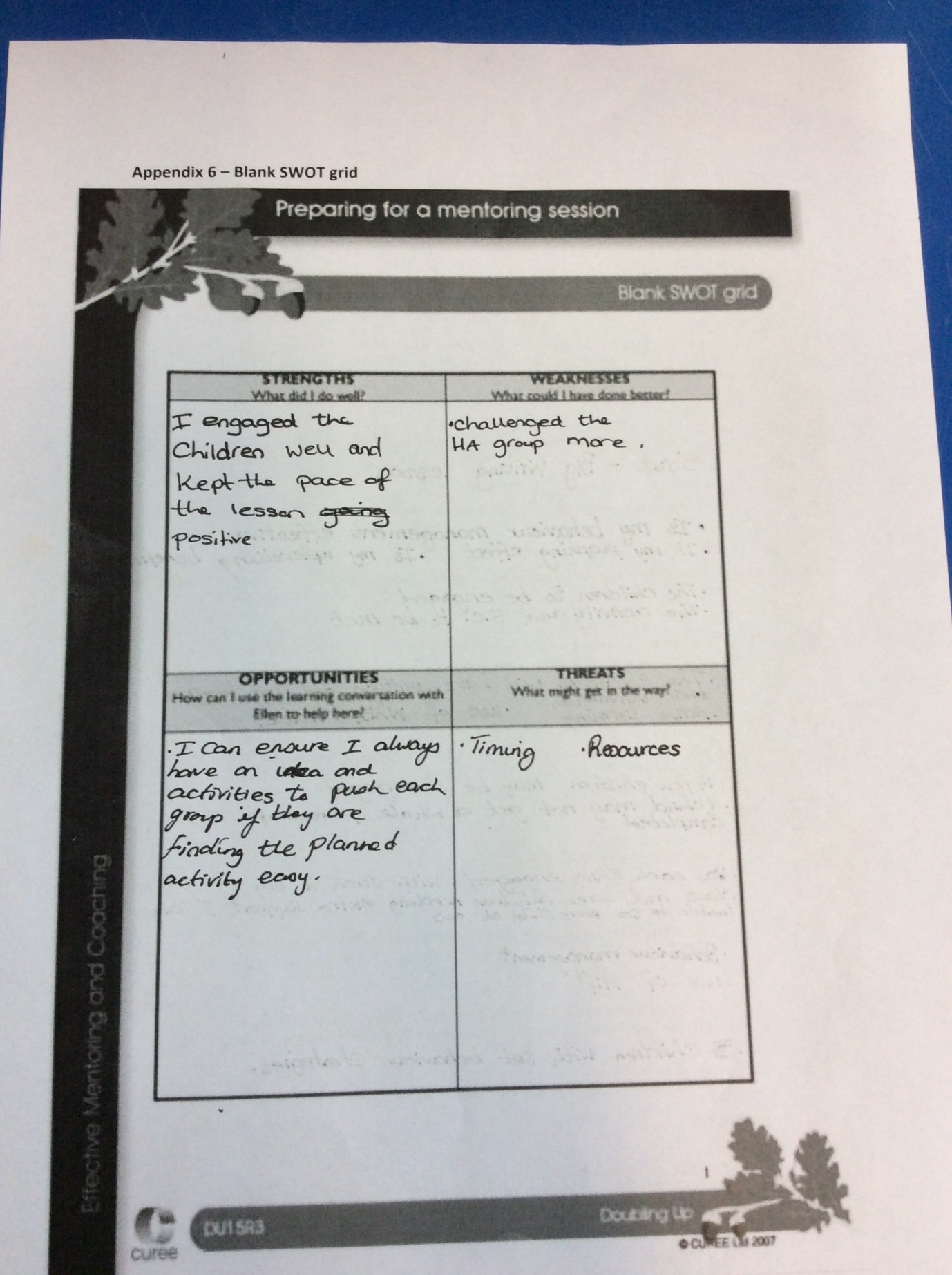

A recommendation of a collaborative approach to observation is reiterated in Education Scotland documentation (undated b) and by the Centre for the Use of Research and Evidence in Education (CUREE, 2005) who created a series of documentation to aid the implementation of effective professional development through mentoring and coaching. Formal observations occurred twice a week throughout the duration of placement, covering a variety of curricular areas to provide scope and opportunity to increase depth of curricular knowledge for the student teacher. The process described below was implemented on Week 3 of the placement block as a means of enabling another support mechanism for both involved in the mentoring process.

Both documents were completed by the mentee and myself as the observer. Firstly, an observation schedule (Appendix 11) was completed before the first stage of the process; the pre-observation meeting, alongside a SWOT grid (Appendix 12) documenting the mentee’s self-reflections and evaluations of their Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats before the final stage; the post-observation meeting. Both pieces of documentation provided opportunities for the development of questioning skills and allowed the mentee to put forward their own opinions and ideas, based on their written reflections. I believe this approach to observations had the most significant impact upon the professional development of the mentee. The incorporation of written and oral collaborative discussion afforded deeper opportunities for true critical reflection as they were completed in a more collaborative, timely fashion with the post-observation meeting occurring directly after the taught lesson. Reflecting upon the overall process, the mentee stated a number of advantages to both documents (see Appendix 13). The mentee deemed the observation schedule as a useful tool to establish a clear focus for the observation, together with the SWOT grid allowing an accessible platform for self-evaluation. I am in agreement with these statements, singularly I found the SWOT grid a beneficial means of encouraging self-reflection and evaluation by taking consideration of one’s strengths and weaknesses after a lesson. Education Scotland (undated b) advocates immediate reflections post-lesson, to ensure an accurate account of the experience. I hope to gain more confidence and experience using these documents again as a mentor in the future.

Personal Self-Reflection

Through my engagement with the course ED50JK, I have developed my overall understanding of the processes of mentoring and coaching and learnt more about the intricate dynamics of mentoring and coaching models, particularly the complexity of the mentor-mentee relationship and the impact this can have upon the process as a whole.

Moreover, the surprising personal acknowledgment that mentors can learn and gain as much from the process as the mentee through a continued commitment and participation in the mentoring and coaching process. Nicholls (2002, p.142) argues that mentoring ‘is also seen as a powerful tool for professional development…encouraging systematic critical reflection”. Accepting the role of a mentor affords teachers professional progression and development through their widened experiences, providing support for another individual can lead to enhanced professional practice for those involved (Moor et al, 2005). Through mentoring a student teacher, I feel I have deepened my understanding of the application of coaching and mentoring models, and the significant role they play in the process. The GTCS (2007) emphasise the importance of providing practical opportunities for student teachers to apply and reflect on the theoretical approaches studied at university and through the mentoring process, I have developed my recognition of this. I have now had experience of contributing to the overall education of a beginning teacher and how my own teaching practice can influence theirs, how explicit teaching and modelling of effective, practical strategies can provide opportunities for learning and development for a career in teaching.

Careful consideration of the mentoring approach will be undertaken in the future, further research into the three models (apprenticeship, directive and responsive) and how these correlate into a real-life context would be beneficial. I will endeavour to devote more time to getting to know the mentee on a personal level and to work on finding commonalities to establish a more positive relationship. I feel an apprenticeship or responsive approach will be more suited to my personality and values and beliefs, although the approach will of course, be dependent on the mentee. I will also be more willing to seek guidance from more experienced colleagues, management and tutors, with the intention of improving my mentoring ability and developing further professionally.

My reflective and communication skills have been broadened through these experiences and I now consider these within my own teaching practice more fully, especially with regards to my strengths and areas for development, in order to continue to meet the Standards for Continuing professional Learning (Education Scotland, undated c).

I aim to ensure that I can continue to build upon my mentoring and coaching experiences next year through the mentorship of a probationer teacher, and that I learn from my experiences this year, by combining my current skills and abilities as a mentor with critical reflection and self-evaluation of my strengths and areas for improvement as a mentor and coach.

My areas for development, next steps and current strengths through my involvement in the mentoring process and this course have been detailed in the form of a Continuing Professional Learning (CPL) log, attached in Appendix 14.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the mentoring and coaching process is advocated by many namely; Education Scotland (undated b), GTCS (2007), Williams and Prestage (2002) and Hobson (2002) to name but a few. Though there are factors within the mentoring and coaching process such as the delivery and the nature of the mentor/mentee themselves which can hinder the process somewhat. It is important to note that ‘having access to a ‘mentor’, does not guarantee a successful mentoring process’. Smith (2000) reviews the need for individualised learning for the mentee, much like that of the child-centred approach advocated in our current curriculum, in order for professional learning and growth to occur. Thus, a focus must be placed on enhancing reciprocal learning, teaching and communication experiences in order for the mentoring and coaching process to be truly effective ((Yördema and Akyolb, 2014).

NOTES [1] The term mentee in this article is interchangeable with student teacher and NQT, referring to the adult whom has an assigned mentor.

Bibliography

BULLOUGH, V, R, JR. and DRAPER, J, R. (2004). Mentoring and the emotions. J Educ Teach, 30 (3), pp.271 – 288.

BULLOUGH, V, R, JR. (2012). Mentoring and New Teacher Induction in the United States: A Review and Analysis of Current Practices. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 20 (1), pp. 57-74.

CONNOR, M. and PAKORA, J. (2012). Coaching and Mentoring at Work. Open University Press.

CENTRE FOR THE USE OF RESEARCH AND EVIDENCE IN EDUCATION (CUREE). (2005). Mentoring and Coaching CPD Capacity Building Project: National Framework for Mentoring and Coaching. London: DCSF. Available at: www.curee-paccts.com/files/publication/1219925968/National-framework-for-mentoringand-Coaching.pdf [Date accessed: 21st January 2017]

DARLING-HAMMOND, L. and RICHARDSON, N. (2009). Research Review/Teacher Learning: What Matters? How Teachers Learn, 66 (5), pp. 46-53.

DEMBKOWSKI, S. and ELDRIDGE, F. (2003). Beyond GROW: A new coaching model. The International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching. 1 (1)

DOMINGUEZ, N. and HAGER, M. (2013). Mentoring frameworks: synthesis and critique. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 2 (3), pp.171-188.

THE EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTE OF SCOTLAND (EIS). (2008). Coaching and Mentoring. Edinburgh: EIS.Available at: http://www.eis.org.uk/images/EIS%20policies/coaching%20and%20mentoring%200108.pdf

[Date accessed: 2nd April 2017]

EDUCATION SCOTLAND (undated a). Professional Update, Coaching and Mentoring, Core Characteristics of Coaching and Mentoring. Available: http://www.gtcs.org.uk/professionalupdate/coaching-and-mentoring.aspx [Date Accessed: 13th April 2017].

EDUCATION SCOTLAND (undated b). What is mentoring, How does mentoring improve teaching and learning? Available: http://www.educationscotland.gov.uk/professionallearning/mentoringmatters/whatisment oring/improvelearningandteaching.asp [Date Accessed: 13th April 2017].

EDUCATION SCOTLAND (undated c). Career-long professional learning, Self-evaluation. Available: http://www.educationscotland.gov.uk/professionallearning/clpl/selfevaluation.asp [Date Accessed: 13th April 2017].

FEIMAN-NEMSER, S. (2001). From preparation to practice: Designing a continuum to strengthen and sustain teaching. Teachers College Record, 103 (6), pp. 1013-1055.

GENERAL TEACHING COUCIL FOR SCOTLAND (GTCS) (2007). Teacher Induction Scheme, Probation Supporter Guidance. Edinburgh, GTCS. Available: http://www.in2teaching.org.uk/nmsruntime/saveasdialog.aspx?fileName=teacher-inductionscheme-probationer-supporter-guidance1647_2091761_54.pdf [Date Accessed: 15th April 2017].

GENERAL TEACHING COUCNCIL FOR SCOTLAND (GTCS) (2012). The Standards for Registration: mandatory requirements for Registration with the General Teaching Council for Scotland. Edinburgh: GTCS. Available: http://www.gtcs.org.uk/web/files/the-standards/standards-for-registration- 1212.pdf [Date Accessed 15th April 2017]

GENERAL TEACHING COUNCIL FOR SCOTLAND (GTCS). (2016) Professional Update: Coaching and Mentoring. Edinburgh: GTCSAvailable at: http://www.gtcs.org.uk/professional-update/professional-learning/coaching-and-mentoring.aspx [Date accessed: 15th April 2017]

GENERAL TEACHING COUNCIL FOR SCOTLAND (GTCS) (Undated a). About GTC Scotland, Available: http://www.gtcs.org.uk/about-gtcs/about-gtcs.aspx [Date Accessed: 14th April 2017].

GENERAL TEACHING COUNCIL FOR SCOTLAND (GTCS) (undated b). Coaching and Mentoring, Coaching and Mentoring Defined. Available: http://www.gtcs.org.uk/professionalupdate/coaching-and-mentoring.aspx [Date Accessed: 15th April 2017].

GENERAL TEACHING COUNCIL FOR SCOTLAND (GTCS) (undated c). In2Teaching, Probation process. Available: http://www.in2teaching.org.uk/teacher-induction-scheme/teacherinduction-scheme-probation-process.aspx [Date Accessed: 16th April 2017].

HALATIN, T. J.7 and KNOTTS, R. E. (1982). Becoming a mentor: Are the risks worth the rewards? Supervisory Management 27(2), pp. 27 – 29

HANKEY, J. (2004). The Good, the Bad and Other Considerations: reflections on mentoring trainee teachers in post-compulsory education. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 9 (3), pp. 389-400.

HM INSPECTORATE OF EDUCATION (HMIE). (2008). Mentoring in Teacher Education. Edinburgh: HM Inspectorate of Education. Available at: http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/998/7/mite_Redacted.pdf

[Date accessed: 11th April 2017]

HOBSON, A.J. (2002). Student Teachers’ Perceptions of School-based Mentoring in Initial Teacher Training (ITT), Mentoring &Tutoring: Partnership in Learning. 10(1), pp. 5-20.

HOBSON, A.J., ASHBY, P., MALDEREZ, A., and TOMLINSON, P.D. (2009). Mentoring beginning teachers: What we know and what we don’t. Teaching and Teacher Education. 25, pp. 207-216

HOUSEGO, E, J, B. (1990). Student Teachers’ Feelings of Preparedness to Teach. Canadian Journal of Education, 15 (1), pp.37-56. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1495416

[Date accessed: 17th April 2017 ]

INGERSOLL, R. and STRONG, M. (2011). The Impact of Induction and Mentoring Programs for Beginning Teachers: A Critical Review of the Research. Review of Education Research, 81 (2), pp.201-233. Available at: http://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/127 [Date accessed: 10th January 2017]

JONES, M. (2001). Mentors’ perceptions of their roles. Journal of Education for Teaching, 27 (1), pp. 75 – 94.

KWAN, T. AND LOPEZ-REAL, F. (2005). Mentors’ perceptions of the perceptions of their roles in mentoring student teachers. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 33 (3), pp. 275-287

LILJENSTRAND, M, A. (2003). A comparison of practices and approaches to coaching based on academic background. Dissertation (Dual Doctor Philosophy Degree). The California School of Organizational Studies and The California School of Professional Psychology Alliant International University.

LINDGREN, U. (2005). Experiences of beginning teachers in a school-based mentoring program in Sweden. Educational Studies. 31(3), pp. 251-26

LORD, P., ATKINSON, M., and MITCHELL, H. (2008). Mentoring and coaching for professionals: A study of the research evidence. Berkshire: National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER)

LUCAS, P. (1995). A neglected source for reflection in the supervision of student teachers. In KERRY, T. and MAYES, A.S. (1995) Issues in Mentoring. London: Routledge, pp. 129-135.

MAYNARD, T. (2000) Learning to teach or learning to manage mentors? Experiences of school-based teacher training, Mentoring and Tutoring,8(1), 17-30.

MCR PATHWAYS. (undated). Mentoring Matters. Glasgow: Glasgow City Council. Available at: https://www.glasgow.gov.uk/councillorsandcommittees/viewSelectedDocument.asp?c=P62AFQDNT1ZLT1NTZL [Date accessed: 13th January 2017]

MOOR, H., HALSEY, K., JONES, M., MARTIN, K., STOTT, A., BROWN, C. and HARLAND, J. (2005). Professional Development for Teachers Early in Their Careers: an Evaluation of the Early Professional Development Pilot Scheme (DfES Research Report 613). London: DfES. Available at: http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/research/data/uploadfiles/RR [Date accessed: 13th January 2017]

NICHOLLS, G. (2002). Mentoring: the art of teaching and learning. In: P. JARVIS, ed., The Theory & Practice of Teaching. London: Routledge, pp.132-142.

PASK, R. and JOY, B. (2007). Mentoring-coaching: A Guide for Education Professionals. 1st Edition. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

RIPPON, R. and MARTIN, M., (2003). Supporting Induction: relationships count. Mentoring and Tutoring. 11(2), pp. 211-226

RHODES OFFUTT, E. (1995). Identifying Successful versus Problematic Student Teachers. The Clearing House, 68 (5), pp. 285-288.

SCOTTISH CATHOLIC EDUCATION SERVICSE (SCES) (2016). A Charter for Catholic Schools in Scotland. SCES WordPress. Available at: http://sces.org.uk/excellent-catholic-schools/

[Date accessed: 22nd February 2017]

SMITH, M.E., (2000). The Role of the Tutor in Initial Teacher Education. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 8(2), pp. 137-144.

STANULIS, R. N., & RUSSELL, D. (2000). “Jumping in”: Trust and communication in mentoring student teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(1), pp. 65-80.

STRONG, M. & BARON, W. (2004) An analysis of mentoring conversations with beginning teachers: suggestions and responses, Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(1), pp. 47-57.

TRIVETTE, C.M., DUNST, C.J., HAMBY, D.W. and O’HERIN.C.E. (2009). Characteristics and Consequences of Adult Learning Methods and Strategies, Research Brief. Tots n Tech Research Institute. 3(1), pp.1-33.

VALENCIA, S. W., MARTIN, S. D., PLACE, N. A., and GROSSMAN, P. (2009). Complex interactions in student teaching: Lost opportunities for learning. Journal of Teacher Education, 60, pp. 304–322

WHITMORE, J. (2004). Coaching for performance: GROWing people, performance and purpose. (3rd Edition.). London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

WILLIAMS, A. and PRESTAGE, S. (2002). The Induction Tutor: Mentor, manager or both? Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 10(1), pp. 35-46.

YORDEMA, A. and AKYOLB, B. (2014). Problems of mentoring practices encountered by the prospective ELT teachers: Perceptions of faculty tutors. European Journal of Research on Education, 2(Special Issue 6), pp.142-146.

YOUNG, J. R., BULLOUGH, R. V., DRAPER, R. J., SMITH, L. K. & ERICKSON, L. B. (2005) Novice teacher growth and personal models of mentoring: choosing compassion over enquiry, Mentoring and Tutoring, 13(2), pp. 169-188

ZACHARY, L.J. (2000). The Mentor’s Guide, Facilitating Effective Learning Relationships. San Francisco: Jossey Bass

ZEICHNER, K. (2010). Rethinking the Connections Between Campus Courses and Field Experiences in College and University-Based Teacher Education. Journal of Teacher Education, 61, (1-2), pp. 89-99.

Appendix 1: The Charter for Catholic Teaching in Scotland

SCOTTISH CATHOLIC EDUCATION SERVICSE (SCES) (2016). A Charter for Catholic Schools in Scotland. SCES WordPress.

Appendix 2: Timeline of Events

NB: In addition, opportunities for more informal discussions and questions were provided on a daily basis, as and when required.

| WEEK 1 | WEEK 2 | WEEK 3 | WEEK 4 | WEEK 5 | WEEK 6 | WEEK 7 | WEEK 8 | |

| MONDAY | Discussion: Overview of student handbook.

Class information. School expectations. |

Responsibility for one group in Maths or Language all week. | Continuous practice begins. | Continuous practice.

Classroom observation.*

|

Classroom observation.* |

|||

| TUESDAY | Discussion:

Planning for group work sessions. Curricular areas focus for term. Staff meeting |

Classroom observation.

Staff meeting

|

Classroom observation.

Forward planning review and discussion. |

Classroom observation.

Staff meeting |

Forward planning review and discussion.

Staff meeting |

Classroom observation.*

|

Whole class responsibility all day.

Staff meeting |

Classroom observation.*

Staff meeting |

| WEDNESDAY | Mid-week meeting:

Record of conversation – planning, next steps etc. |

Mid-week meeting:

Record of conversation – planning, next steps etc. |

Mid-week meeting:

Record of conversation – planning, next steps etc. |

Mid-week meeting:

Record of conversation – planning, next steps etc. |

Classroom observation.*

Mid-week meeting: Record of conversation – planning, next steps etc. |

Mid-week meeting:

Record of conversation – planning, next steps etc. |

Mid-week meeting:

Record of conversation – planning, next steps etc. Classroom observation.* |

Mid-week meeting:

Record of conversation – planning, next steps etc. |

| THURSDAY | Group work session for student: observed. | Classroom observation. | Classroom observation.

* use of CUREE documentation to record obs. |

Whole class responsibility all day.

Classroom observation.*

|

||||

| FRIDAY | Formal Meeting:

PROP Form and discussion.

|

Formal Meeting:

PROP Form and discussion. |

Classroom observation.

Formal Meeting: PROP Form and discussion. *use of GROW model to support discussion. |

Formal Meeting:

PROP Form and discussion. *use of GROW model to support discussion. |

Formal Meeting:

PROP Form and discussion. *use of GROW model to support discussion. |

Formal Meeting:

PROP Form and discussion. *use of GROW model to support discussion. |

Formal Meeting:

PROP Form and discussion. *use of GROW model to support discussion. |

Formal Meeting:

PROP Form and discussion. *use of GROW model to support discussion. |

Appendix 3: The GTCS Mentoring Continuum

The GTCS continuum taken from: GENERAL TEACHING COUNCIL FOR SCOTLAND (GTCS). (2016) Professional Update: Coaching and Mentoring. Edinburgh: GTCS Available at: http://www.gtcs.org.uk/professional-update/professional-learning/coaching-and-mentoring.aspx [Date accessed: 12th January 2017]

| Instructive | Collaborative | Facilitative |

|

|

|

| Suggest a strategy for meeting with new clients

Suggest strategies for effective classroom organisation and management |

Problem solve issues of practice

Observe a colleague’s practice together and share thoughts ideas Monitor and evaluate aspects of behaviour |

Listen to analysis of practice

Pose questions which enable deeper thinking to take place |

| Conversation stems

One thing I have learned… From our experience… Something you might consider trying… Something which might work for you.. Follow-up Question What do you think might happen if you were to try that? To what extent do you think that might work in your situation? Which of these ideas might work best? |

Conversation stems

One of the key learning points for me … Is there another way we could… Let’s identify the main areas… Let’s work on developing that together… Let’s visit….. together.. Questions Could we try? Which aspect would you like me to model? |

Conversation stems

It sounds like you have a number of ideas to try out. I am interested in hearing more about… What has made this so successful? Let me see if I understand… Questions What kind of impact do you think that would that have? Have you seen anything like this before? What criteria are you using? |

Adapted from New Teacher Center, Santa Cruz, California (2007) at http://www.newteachercenter.org

Appendix 4: Records of conversation

Appendix 5: GROW Model

The GROW Coaching Model adapted from: WHITMORE, J. (2004). Coaching for performance: GROWing people, performance and purpose. (3rd Edition.). London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

df

Appendix 6: GROW Model Approach; Mentee Feedback Table

| Feedback from the mentee pertaining to the use of the GROW model approach during discussions | |

| Strengths | Areas for Development |

|

|

Appendix 7: Extract from Summative Report

| 2.3 Pedagogical Theories and Practice | S | Comments on progress to date drawing on evidence |

| Have knowledge and understanding of relevant educational principles and pedagogical theories to inform professional practices

These key features are assessed on campus by University staff. Please do not assess this key feature below within 2.3: Have knowledge and understanding of the importance of research and engagement in professional enquiry

|

******** has begun to make more frequent references to pedagogical theories in her school experience file. There is some evidence of the use of the theory bank provided in the file through annotations.

– Continue to refer to theory to inform all areas of your practice – planning, teaching, learning and assessment

|

|

| 2.1 Curriculum | S | Comments on progress to date drawing on evidence |

Have knowledge and understanding of the relevant area(s) of pre-school, primary and secondary curriculum Have knowledge and understanding of planning coherent and progressive teaching programmes Have knowledge and understanding of contexts for learning to fulfil their responsibilities in literacy, numeracy, health and wellbeing and interdisciplinary learning Have knowledge and understanding of the principles of assessment, recording and reporting

|

********’s curricular knowledge has improved over the placement. She has shown more awareness of how to plan progressive lessons during her second block. After advice given by the class teacher, ******** has now planned for progression in learning through a series of linked lessons. ******** made more effort to fulfil the minimum planning folder requirements during the second week of the second block, she needs to be more proactive in finding and supplying information for herself, without the need to be prompted. ******** must change and adapt her practice in this aspect to a satisfactory degree in order to better meet the needs of all learners and develop herself as a professional, reflective pracititioner. ******** used a limited amount of AiFL strategies but is showing an improved understanding of how assessment results inform future planning. She should work hard to ensure she is fulfilling the curriculum requirements of the school (themed weeks and curricular developments) by incorporating these aspects fully into her planning; e.g. she did not embrace Catholic Education week fully by only planning one activity for the week. There has been little concrete evidence of ********’s ability to differentiate; this is an area of development. She must make it explicit within her planning and during the lesson how she is differentiating, whether by support, task or outcome. ******** should focus further on developing her knowledge and understanding of assessment and its role within the primary curriculum.

Next Steps: Continue to develop a deeper understanding of how assessment is used to move the learning forward and its central role in planning. Continue to take opportunities to try out a wide range of learning and teaching approaches. Continue to plan for extra support and extension for learners as a matter of course. Continue to use your initiative to seek out or make the most appropriate learning resources – Ensure she keeps up to date with current educational priorities. Understand the importance of planning for effective learning across different contexts and experiences.

|

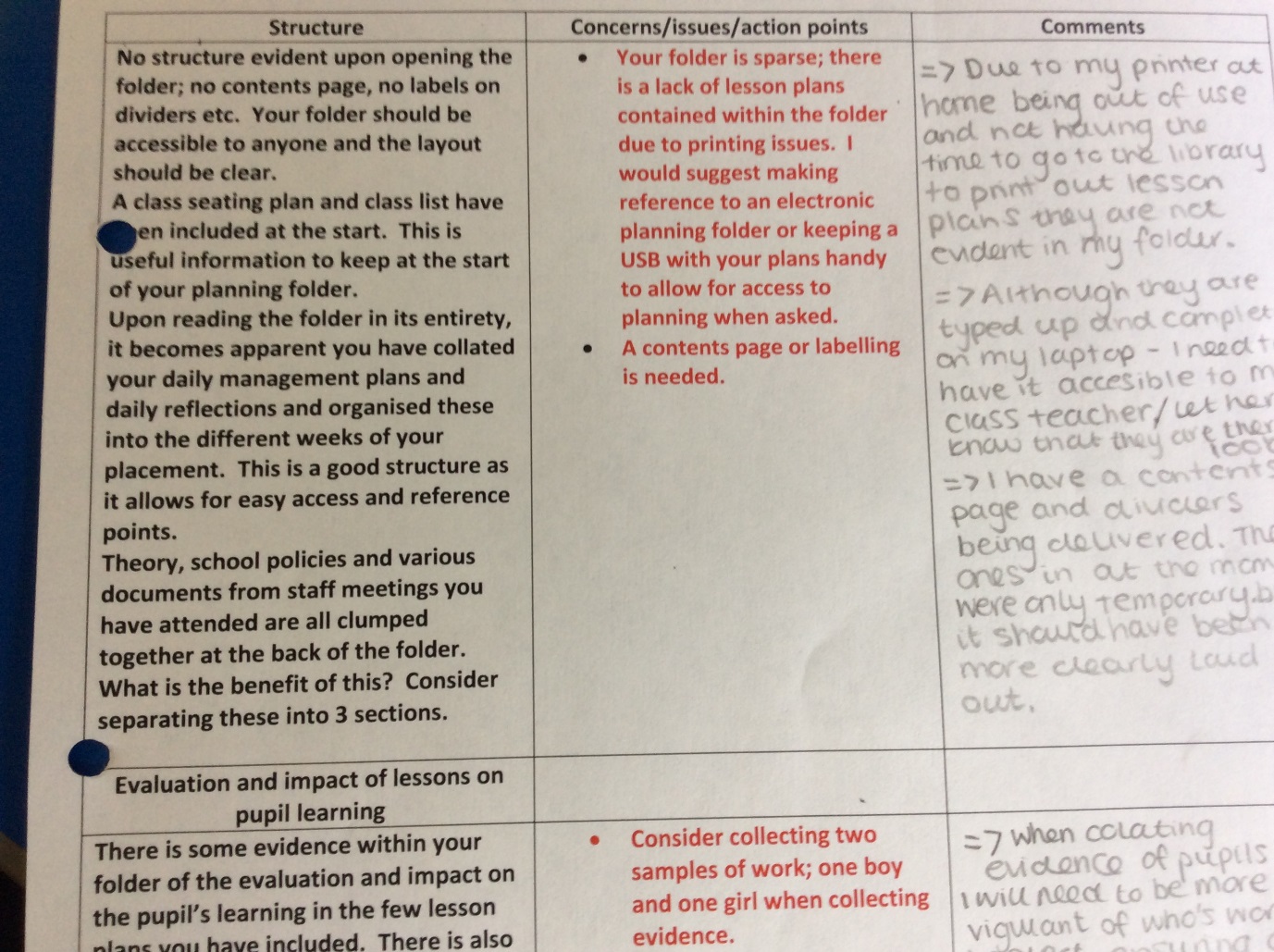

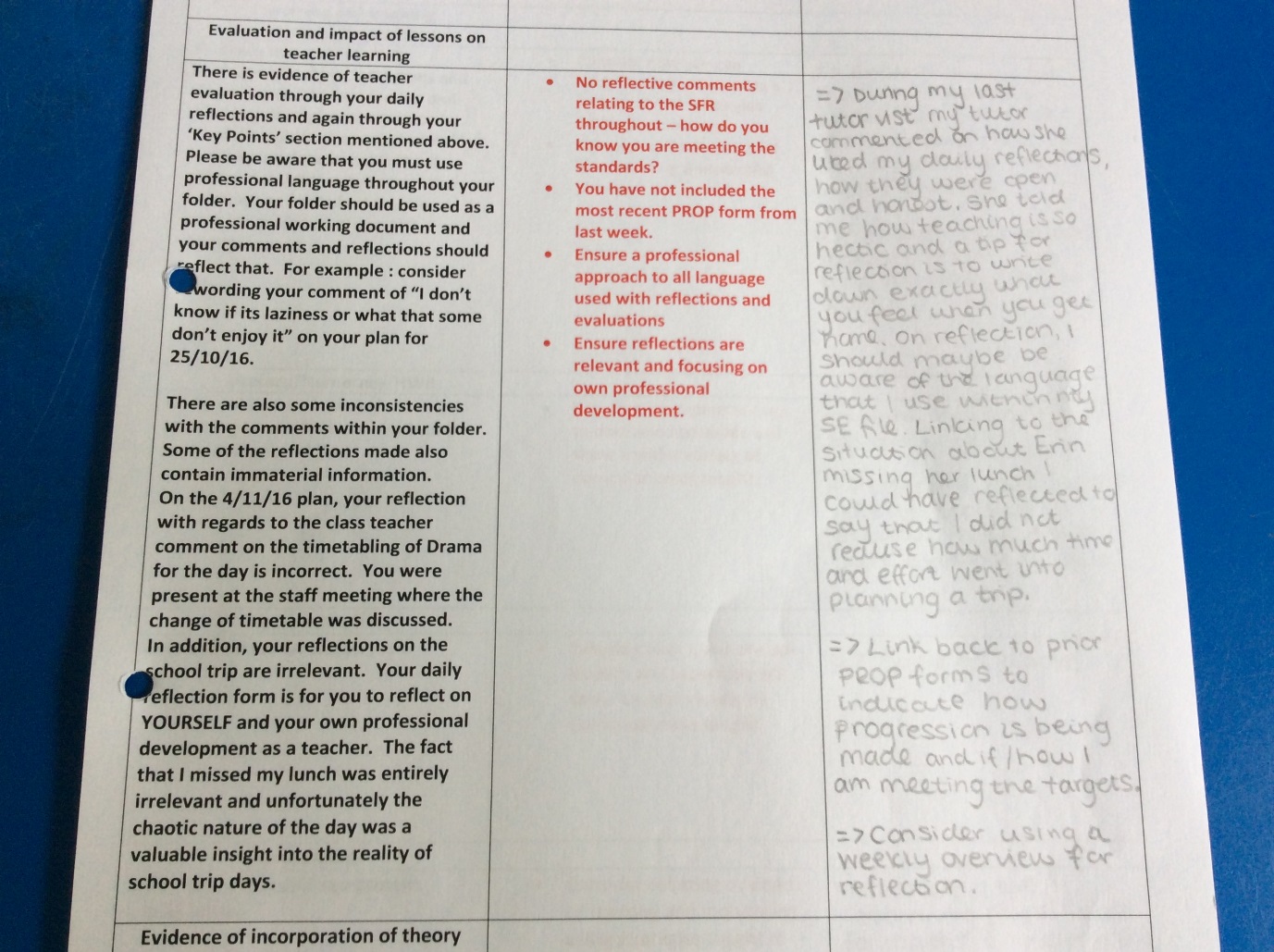

Appendix 8: Extracts of PROP forms and planning review

| Supporter teacher feedback |

| This week ******* has taught five whole class lessons over a wide spread of curricular areas. She used the experienced PSA within the class as support for a few of the less able learners during her lessons. However, I question her comment regarding differentiation. This is an area of development for*******, as throughout my observations this week the whole class have been given the exact same task for each lesson and it is unclear whether she was intending to differentiate by outcome or level of support. During her Science lesson for example, the cloze passage activity was too easy for the HA group, with no challenge extension task provided, and the LA group containing EAL children were not supported through use of a word bank or another appropriate resource. I would encourage ******* to look further into the theory and policy behind the application of differentiation to develop her professional practice.

Professional dialogue regarding *******’s planning folder occurred twice during the week where concerns were raised regarding the content. Upon myself as the class teacher seeking guidance from the university and colleagues with students in another school, and sharing this feedback with *******, she is now more accepting of the expectations with regards to the professional standard she must adhere to. She showed some desire to improve by creating a new forward planning template during her NCCT today. She must continue with this and recognise the importance of keeping her folder up-to-date, accessible and with appropriate content during her continuous and throughout her future career. It is good to see that ******* has made reference to some elements of this through her proposed targets detailed above, showing she is beginning to reflect upon feedback she is given. There are two further areas for ******* to consider before undertaking her continuous practice. Firstly, there have been issues with behaviour management this week. It is important that she sets high expectations for behaviour from the outset and uses positive behaviour strategies to encourage and promote good behaviour from the children. Researching different strategies and incorporating those already in place within the class will help. She should bear in mind the role of relationships and interactions and work on building up a rapport with each individual child to help with questioning, enthusing and engaging the class. Moving forward, she needs to actively take on board feedback and demonstrate this explicitly through her planning and teaching to ensure a successful continuous practice. |

| Student adjustments towards targets from learning conversation/s with supporter teacher |

Appendix 9: Extract from Summative Report

| 3.1 Teaching and Learning | S | Comments on progress to date drawing on evidence |

| Communicate effectively and interact productively with learners, individually and collectively

Employ a range of teaching strategies and resources to meet the needs and abilities of learners Have high expectations of all learners Work effectively in partnership in order to promote learning and wellbeing Demonstrate a competent standard of literacy

|

In the last weeks of her placement, ******* showed some understanding of the importance of forward planning, and as this developed she began to plan more appropriately for the class. She also became more aware of constructing planned learning intentions with her daily plans. She has started to give more consideration to pace and challenge within her lessons, however this has been inconsistent. ******* should consider researching and implementing a variety of teaching and learning strategies; her fail-safe lesson activity of researching on iPads was over-used and did not challenge the children appropriately. She must more aware of the importance of lesson introductions to ensure the children fully understand what they are learning and why; for example throughout her continuous she taught the mini-topic of the Stuarts but the class are still unable to describe who the Stuarts are. Her linked lessons of the Plague and the fire of London were not relevant to Topic, particularly from a child’s standpoint.

For the most part, ******* communicated well with the children and she had a confident presence in the classroom. When modelling literacy for the pupils and completing professional documentation, ****** should ensure she checks the spelling, grammar and punctuation of any writing she displays in the classroom or in her folder. Next steps: – Continue to provide quality feedback to all learners. Ensure ****** doesn’t rely on oral feedback as it is vital to have written communication for children and parents to access. – Always make sure she sets high expectations for the pupils and supports them by giving clear examples of how to complete their work in an organised and neat manner. – Develop use of teaching and learning strategies through engagement in professional readings, CPD courses and discussions/observations with colleagues – Ensure provision of appropriate, differentiated resources at all time – consider ways to ensure effective organisation skills and encompass the needs of the learners |

Appendix 10: Links to theory through PROP forms

| Supporter teacher feedback |

| ******* has had a positive first week of her school placement. She has strived hard to form relationships with the children in the class and has shown this through her regular interactions with the children. She has been respectful and mindful of the teachings and beliefs in place within the school by joining in with our daily prayers. In order to progress over the coming weeks, ***** should familiarise herself with the Catholic Charter for Schools to allow her to fully understand the roles and responsibilities of a teacher in a Catholic school and engage with This is Our Faith in order to develop her knowledge of the RME curriculum. She will have more experience of this when she attends the school Mass next week.

****** has planned four class lessons this week, three Maths and one Health & Wellbeing. She has shown an initial understanding of planning for a group of children but it is important to remember to integrate the procedures already in place within the class, particularly with the Maths groupings, in order to ensure continuity for the learners. For next week, she should consider how she can make an accurate assessment on the collective motivation of the children – the Leuven scale of engagement may be useful for this. In addition, she should place more emphasis on assessing that all children are contributing to the task at hand and that the activity is not being monopolised by one or two individuals. ******* has shown her respectful manner when communicating with the children, this was evident during her Health & Wellbeing lesson during the question and answer section. However some learning opportunities were missed throughout this part of the lesson. With more experience, she will learn that it can be good practice to deviate from the lesson plan and follow the lead of the children to help create a more child-centred approach to the learning. More use of visual representations during her lessons will help aid the understanding and enjoyment of the children. This is something she has discussed in her reflections and her planning for the coming week reflects this. In addition, ****** should consider engaging in readings regarding Autism, accessing The Autism Toolbox would be beneficial, in order to develop her understanding of strategies for working with particular pupils within the class. |

| Student adjustments towards targets from learning conversation/s with supporter teacher |

| – Build upon professional knowledge and understanding of the role of a teacher within a Catholic school

– Familiarise self with class teacher tracking and recording of Mathematics – Build upon relationship with PSA and familiarise self with working with an ASN child – Develop planning skills through further teaching days

|

Appendix 11: Observation Schedule

Appendix 12: SWOT Grid

Appendix 13: Feedback from mentee on use of observation documentation

| Completion of observational schedule prior to pre-observation meeting | |

| Strengths | Areas for Development |

|

|

| Completion of SWOT grid following observation | |

| Strengths | Areas for Development |

|

|

Appendix 14: CPL Log

CPL (CPD) REFLECT – LEARNING LOG

Complete this log for each key CPL/CPD experience which you undertake.

- Pre CPL experience/event/activity: to help you justify your rationale/reason for the CPL activity/experience and identify your specific CPL target and planned outcomes

- CPL experience/event/activity: to capture brief overview of date(s); details of CPL

- Post CPL experience/event/activity: to identify your learning; to reflect on the impact of your learning on your practice; to identify the evidence you have to demonstrate your learning and its impact on your professional practice.

| Pre-CPL activity/experience/event | ||

| Rationale for CPD | To develop my professional knowledge and understanding of mentoring and coaching, focussing specifically on the models, frameworks, approaches and techniques used and discussed in key literature and policy to mentor/coach beginning teachers (student or probationer). | |

| Specific CPD Target |

|

|

| Anticipated outcomes (links to CLPL) | 1.4 – Profession Commitment

2.2 – Professional Skills and Abilities 3.5 – Sustaining and developing profession learning |

|

| CPL activity/experience/event | ||

| Title of activity/experience/event | MED Negotiated Extended Study ED50JK | |

| Date(s) of engagement | 2016 – 2017 | |

| Brief outline of the CPL experience/activity/event | Online learning course provided by the University of Aberdeen, structured into 4 key themes of mentoring and coaching. Activities and readings were provided throughout the duration of the course to support and guide the mentoring process. Collaborate sessions were used to encourage professional dialogue. A summative assignment, split into two sections comprise the assessment criteria of the course. | |

| What have I learned from this new experience/activity/event? (eg. new knowledge, skills, attributes, qualities) |

|

|

| Post CPL activity/experience/event | ||

| How can I evidence my new learning/knowledge/skills? |

|

|

| Planned action arising from CPD experience/activity/event | I hope to develop my acquired skills and knowledge of techniques and approaches further through becoming a mentor to a probationer teacher next school session. I will also engage with further professional readings regarding mentoring approaches to develop my current understanding of embedding theory into practice. | |

| What further reading/enquiry has informed my thinking and practice in this area? | See bibliography from summative assignment parts 1 and 2 of course ED50JK. | |

| How have I applied what I learned to my professional practice? | Throughout the student placement experience within my class setting, I have undertaken observations, provided reflective feedback, report writing, application of coaching models and engaged in professional dialogue. | |

| The impact this has had on my practice – how have I consolidated or enhanced my practice? | What evidence to I have to support this? | |

|

|

|

| The impact this has had on the children in my class. | What evidence do I have to support this? | |

| None as yet. | None as yet.

|

|

| The impact this had had on other colleagues/wider school community. | What evidence do I have to support this? | |

|

|

|

| Next steps:

… for my CPL … for my practice … for reading … for evaluating impact and gathering evidence … for sharing with others

|

Over the next school session, I will aim to:

|

|

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Young People"

The term Young People often refers to those between childhood and adulthood, meaning that people aged 17-24 are often considered to be a young person.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: