Relationship Between Pregnancy, Childbirth and IPV

Info: 38563 words (154 pages) Dissertation

Published: 16th Dec 2019

Chapter 1

Introduction |

The chapter introduces the social and health problem of intimate partner violence (hereafter referred to as IPV[1]), highlights gaps in the research on IPV around the time of pregnancy in Bangladesh, and outlines the aims of the current research. It also provides a layout of the dissertation.

1.1 Contextualizing the problem

Pregnancy has been described as a life-changing event for women, introducing a range of new trials and tribulations. On the one hand, pregnancy is often a time of happiness and expectancy characterized by maternal optimism, emotional uplifts and growing social support (DiPietro, Hilton, Hawkins, Costigan, & Pressman, 2002; Ogbonnaya, Kupper, Martin, Macy, & Bledsoe-Mansori, 2013). Culturally, pregnancy is often viewed as a time of happiness and expectancy in women’s lives, with the welcoming of the next generation and growing anticipation of the joys a new child will bring to the family. However, pregnancy can also be a stressful and anxiety-provoking life event (Bondas & Eriksson, 2001) since it is a major life transition (Bost, Cox, Burchinal, & Payne, 2002) and, for some women, poses a maturational crisis they are ill-prepared for (Bondas & Eriksson, 2001). Regrettably, pregnancy can also introduce an increased risk for experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV) for millions of women of reproductive age worldwide (Chang et al., 2005; Devries et al., 2010; Garcia-Moreno & Watts, 2011; James, Brody, & Hamilton, 2013; Kendall-Tackett, 2007). IPV is the most frequent form of violence against women and includes acts of physical, sexual and psychological coercion as well as controlling behaviours by a current or former intimate partner or husband (World Health Organization (WHO) & Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), 2012).

Home is often considered as a haven for women and children, where there is physical and psychological safety, trust and care (Fisher et al., 2013). However, partner violence is a complete contravention of this and makes what should be a place of safety, an environment characterized by threat (Dobash & Dobash, 1979). It occurs among all socioeconomic, religious, cultural backgrounds, heterosexual or same-sex couples, and perpetration can be bidirectional (Campbell et al., 2002; Ellsberg, 2006; Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, & Lozano, 2002; Watts & Zimmerman, 2002). While estimates vary widely, population-based studies indicate that anywhere from 15–71% of women experience IPV worldwide (Ellsberg & Heise, 2005; Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006). A recent meta-analysis that included studies from the US as well as other developed and developing countries, established the prevalence of IPV during pregnancy to be between 4.8% and 63.4% (James, Brody, & Hamilton, 2013). Although, there is no conclusive evidence that women who are pregnant are at greater risk for IPV victimisation (Campbell, Garcia-Moreno, & Sharps, 2004; Devries et al., 2010; Macy, Martin, Kupper, Casanueva, & Guo, 2007; Martin, Mackie, Kupper, Buescher, & Moracco, 2001; Saltzman, Johnson, Gilbert, & Goodwin, 2003), evidence suggests that a significant number of women are exposed to IPV at this vulnerable period, which in turn, jeopardise their lives (Devries et al., 2010; James, Brody, & Hamilton, 2013; Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010).

IPV has a multidimensional radiating impact on women’s lives; it affects women’s physical, sexual, mental and reproductive health (Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006; Plichta, 2004; Trabold, Waldrop, Nochajski, & Cerulli, 2013), and well-being (Krantz, 2002; Riger, Raja, & Camacho, 2002). IPV damages women’s capacities to pursue education and work (McCloskey et al., 2007; Nurius et al., 2003) resulting in increased risk of poverty, divorce and unemployment (Byrne, Resnick, Kilpatrick, Best, & Saunders, 1999; Salomon, Bassuk, & Browne, 1999). It causes more deaths and incapacity among women of reproductive age than cancer, traffic accidents and malaria combined (Gomez-Beloz, Williams, Sanchez, & Lam, 2009). Along with physical and emotional impacts, victims of IPV have also lost a total of approximately 8 million days of paid work yearly, equivalent to 32,000 full-time jobs due to IPV in the US (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2003). Each year IPV costs the US economy $12.6 billion (WHO, 2004) and the Australian economy $13.6 billion (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2013). Homicide is the most extreme consequence of IPV (WHO, 2011). IPV during pregnancy poses a grave risk to two lives – mothers and unborn babies.

IPV during pregnancy is a crucial public health risk and has implications for the health and welfare of the mother, the developing fetus and the newborn during gestation, birth and postpartum (Cha & Masho, 2014; de Jager, Skouteris, Broadbent, Amir, & Mellor, 2013; Islam, Baird, Mazerolle, & Broidy, 2017; Kendall-Tackett, 2007; Lau & Chan, 2007; Leneghan, Gillen, & Sinclair, 2012; Liou, Wang, & Cheng, 2014; Trabold, Waldrop, Nochajski, & Cerulli, 2013). Established direct health consequences of IPV during pregnancy include increased risk of unwanted pregnancy, preterm birth, miscarriage (Shah & Shah, 2010), low birth weight (Bonomi et al., 2006; Dillon, Hussain, Loxton, & Rahman, 2013), emotional distress, depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder and low self-esteem (Howard, Oram, Galley, Trevillion, & Feder, 2013; Yoshihama, Horrocks, & Kamano, 2009). Indirect health consequences include substance abuse (Datner, Wiebe, Brensinger, & Nelson, 2007; Lipsky, Holt, Easterling, & Critchlow, 2005; Sarkar, 2008), constrained access to antenatal care (Bailey & Daugherty, 2007; Cha & Masho, 2014), insufficient weight gain during pregnancy (McFarlane, Campbell, Sharps, & Watson, 2002; Shadigian & Bauer, 2004), disturbances in maternal-child bonding (Janssen et al., 2003; Sharps, Laughon, & Giangrande, 2007; Trabold, Waldrop, Nochajski, & Cerulli, 2013) and early cessation of exclusive breastfeeding (Islam, Baird, Mazerolle, & Broidy, 2017; Taveras et al., 2003). IPV-related homicide is the leading cause of maternal mortality (Chang, Berg, Saltzman, & Herndon, 2005; Cheng & Horon, 2010), accounting for 13% to 24% of all deaths among pregnant women (Plichta, 2004). Once considered a family matter, IPV is now increasingly recognized as a social problem, a critical global health concern (WHO & PAHO, 2012) and a fundamental human rights issue (Amnesty International, 2004; WHO, 2006) due to its deleterious consequences on women.

Because IPV generally occurs in private, many instances of IPV are rarely reported (Flury, Nyberg, & Riecher-Rössler, 2010; Keeling & Mason, 2011), and victims often fear that reporting will increase their risk of potential harm. Additionally, women consider the trade-offs between suffering from IPV and tarnishing their social reputation, which contributes to the low reporting of IPV (Khatun & Rahman, 2012). However, in the past two decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the scope and breadth of research interest in IPV across various disciplines, including criminology, psychology, public health, social work and sociology (Loue, 2001). It is a problem beyond criminal justice, impacting health, legal, economic, education, development, and human rights as well (Malyadri, 2013). After decades of global feminist activism, international institutions now recognize the significance of violence against women (Cook & Kaya, 2010). In 1993, the United Nations began a major initiative targeting violence against women (Johnson, Ollus, & Nevala, 2007), and the WHO now defines violence against women as a serious threat to women’s health, and has been running a major research initiative (Ellsberg & Heise, 2005) in an attempt to address the devastating effects of IPV worldwide.

Although our understanding regarding the risks of IPV during pregnancy is progressing, notable gaps remain. Currently, most of the research on the prevalence, correlates and consequences of IPV during pregnancy and postpartum period have been thoroughly examined in high-income countries (Annan, 2008; Brown, McDonald, & Krastev, 2008), although IPV during pregnancy is commonly occurred in low-and-middle-income countries (27.7%–32%) compared with high-income countries (12%–13.3%) (Devries et al., 2010; James, Brody, & Hamilton, 2013). Limited research has explored these issues in low-income countries including Bangladesh (Fisher et al., 2012; Nasir & Hyder, 2003; Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010). According to Taillieu and Brownridge (2010), IPV during pregnancy in low-income countries is a relatively new area of investigation, and thus, less is known about factors contributing to violence during pregnancy and following childbirth in developing nations. The majority of research has focussed primarily on physical and/or sexual IPV (Howard, Oram, Galley, Trevillion, & Feder, 2013; Scribano, Stevens, & Kaizar, 2013; WHO, 2011). Little is known about the prevalence and correlates of sexual and psychological IPV during pregnancy, although sexual and psychological IPV around the time of pregnancy are proven to have detrimental consequences for women and their children (Chan et al., 2011; Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010; WHO, 2011). Given the potentially profound effects that IPV during pregnancy can have on the physical and mental wellbeing of women and their children, we also need to understand the impact of IPV on pregnant women’s health seeking behaviour in developing countries (Koski, Stephenson, & Koenig, 2011). Comprehensive research focusing on IPV and women’s mental health is scarce (Hegarty, 2011), and it is unclear how the experience of IPV before, during and after pregnancy affects women’s psychological health during the postpartum period (Reichenheim, Moraes, Lopes, & Lobato, 2014). Additionally, IPV during pregnancy may compromise women’s exclusive breastfeeding (EBF, only breast milk until 6 months of age, and thereafter its complementation with safe foods until the child reaches ≥ 2 years) efforts, which can further compromise the health of their newborn. Few studies have examined the influence of IPV on the continuation of EBF (Kendall-Tackett, 2007; Lau & Chan, 2007; Moraes, Oliveira, Reichenheim, & Azevedo, 2011), and therefore the association is poorly understood in the literature (Henderson, Evans, Straton, Priest, & Hagan, 2003).

In summary, there are significant gaps in the knowledge and understanding of IPV around the time of pregnancy, and the influence of different forms of IPV before, during and after pregnancy on maternal health service utilization, maternal mental health, and breastfeeding practices especially in low- and middle-income countries including Bangladesh. To improve the health of expectant mothers and their infants, it is important to investigate the potential correlates for, the co-occurring nature and patterns and the consequences of IPV around the time of pregnancy (Brownridge et al., 2011).

1.2 Setting the context: Bangladesh

1.2.1 Overview of Bangladesh

The people’s republic of Bangladesh is a developing country located in South Asia. With over 160 million people in a 147,570 km2 land mass, it is world’s eighth-most populous country, and one of the most densely-populated (~1,077/ km2) nations in the world (GOB, 2016). The per-capita income is estimated at US$1,466 for the fiscal year 2016 compared to the world average of US$14,301 (GOB, 2016). Eighty-three percent of the population lives on less than US$2 per day, 25% on less than US$1 per day, and 31.5% of people live below the international poverty line of a per capita income of US$ 1.25 per day (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2015). Adult literacy rate (15+ years) for both sexes is 63.6% and male-female ratio is 100.3:100 (GOB, 2016). In 2015, among 188 countries, Bangladesh ranked 142nd position in the Human Development Index, and 111th position in the Gender Inequality Index (UNDP, 2015). The low ranking in the gender inequality index implies that there is significant inequality in income and education between males and females in the society of Bangladesh.

1.2.2 Prevalence of IPV in Bangladesh

Bangladesh has the highest prevalence of sexual and physical IPV among South Asian countries, and it ranks second in the World Bank top 15 countries with the highest global prevalence of physical IPV (Solotaroff & Pande, 2014). The WHO multi-country study states that the lifetime prevalence of physical IPV in Bangladesh ranges from 40%–42%, the sexual IPV ranges from 37–50% and either physical or sexual IPV or both ranges from 53–62% (Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006). The Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS)-2007 reports 48% of ever-married women have experienced physical IPV (NIPORT et al., 2009). Other studies from Bangladesh have reported the past year or current prevalence of physical IPV to be between 16–52% (Dalal, Rahman, & Jansson, 2009; Kabir, Nasreen, & Edhborg, 2014; Sambisa et al., 2010), sexual IPV between 11–65% (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), 2013; Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006; Kabir, Nasreen, & Edhborg, 2014; Naved, 2013), and psychological IPV between 24–84% (Dalal, Rahman, & Jansson, 2009; Kabir, Nasreen, & Edhborg, 2014).

A number of Bangladeshi studies have documented the prevalence of IPV in general, however, a few of them also inquired about its presence during pregnancy. These studies indicated a range of 10–22% of the ever-pregnant women experienced physical IPV (Åsling‐Monemi, Tabassum Naved, & Persson, 2008; Bates, Schuler, Islam, & Islam, 2004; Kabir, Nasreen, & Edhborg, 2014; Naved & Persson, 2008), 10–21% experienced sexual IPV (Hadi, 2000; Kamal, 2013) and 38% experienced psychological IPV during pregnancy (Bhuiya, Sharmin, & Hanifi, 2003). Regardless of the varied prevalence rates across studies, what is abundantly clear is that violence against women in Bangladesh is widespread so much so that the UNICEF defines IPV in Bangladesh as one of the most blatant manifestations of gender asymmetry (United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2011).

1.2.3 Rationale for IPV study in Bangladesh

Maternal and child health has traditionally been considered an important indicator of the health progress and the overall social and economic well-being of a country (Abedin, Islam, & Hossain, 2008). Although considerable progress has been made in reducing maternal mortality globally, Bangladesh remains a leader in maternal mortality, with a ratio of 170 per 100,000 live births in 2013 (WHO, 2014a). It is well recognised that low use of prenatal care (Jasinski, 2004), limited postnatal care (Chakraborty, Islam, Chowdhury, Bari, & Akhter, 2003; Chaudhury, 2008; Kidney et al., 2009), and low birth assistance and attendance by a medically trained professional (Choudhury, Hanifi, Rasheed, & Bhuiya, 2000; Ronsmans et al., 2009) contributes to high maternal and child mortality. Research has begun to investigate the influence of other psychosocial risk factors on maternal and child health.

In South Asian countries including Bangladesh, family planning, major infectious diseases and malnutrition have been on the top of the public health priorities (Hosain, Chatterjee, Ara, & Islam, 2007). IPV has not been acknowledged as a significant public health concern in South Asian nations, and this is especially true in Bangladesh, and thus, it has never received considerable attention at the policy level or in the planning of health frameworks and research (Salam, Alim, & Noguchi, 2006). A study conducted by Afsana, Rashid, Thurston, & BRAC (2005) reviewed existing health policies and plans, interviewed policy makers, service providers and women, and identified some of the challenges and gaps in addressing violence against women in the health policy of Bangladesh. These include (1) absence of government’s concrete policies to address domestic violence and associated health issues; (2) lack of understanding or sensitivity to the issue of IPV and how it affects women’s health; (3) insufficient and weak laws in tackling IPV; (4) inadequate safety and security of victims and individuals working with the abused women; (5) lack of shelter homes; (6) inadequate support for counselling; and (7) lack of adequate training and awareness of health care providers, police, lawyers and other relevant service providers. Without a clear knowledge and understanding of IPV during pregnancy, health care providers, social workers and other service providers are underprepared for the challenges of treating IPV victims.

Despite the increase in the prevalence rate of IPV in Bangladesh, at present, there is little information on IPV during pregnancy and following childbirth. Almost all the research so far has been conducted in the U.S and other developed countries that are not representative of or generalizable to women of Bangladesh. A growing number of studies have been undertaken in Bangladesh to explore significant correlates and consequences of IPV victimization, however, most studies have only considered women of reproductive age in general, and have not investigated the experience of IPV during pregnancy. Only a single study conducted by Naved and Persson (2008) focuses on pregnant women’s experiences on physical IPV only. Except for the single study by Rahman et al. (2012) which ascertained the effect of physical and sexual IPV (did not examine psychological IPV ) on maternal health services utilization using the BDHS-2007 data, no other studies in Bangladesh have specifically examined the impact of IPV during pregnancy on the receipt of prenatal care. At present, there are very few studies in Bangladesh that have examined the prevalence of psychological or sexual IPV during pregnancy nor are there studies that have examined physical, sexual or psychological IPV during the postpartum period. Currently, there are no studies that have focused on maternal exposure to IPV during and after pregnancy, which is independently associated with postpartum depression. Furthermore, no studies in Bangladesh have investigated the effect of IPV during pregnancy on mother’s exclusive breastfeeding efforts.

Addressing the abovementioned gaps, the present study examines IPV victimization during pregnancy. It also explores the influence of IPV around the time of pregnancy on the timing of entry into prenatal care, experiencing postpartum depression and exclusive breastfeeding among women in Bangladesh.

1.3 Purpose of the study

According to Taillieu and Brownridge (2010) research on IPV during pregnancy lacks a guiding theoretical framework. There is also a global gap in the understanding of the relationship between pregnancy, childbirth and IPV. The study aims to fill some of the important gaps in the empirical evidence to help explain the prevalence, correlates and consequences of different forms of IPV before, during and after pregnancy. Currently, our understanding of the influence of IPV during pregnancy on exclusive breastfeeding practices is very limited and therefore, it is envisaged that the findings from this study will help to permeate the theoretical gap in this area. Policy makers should have a comprehensive understanding of how gender inequity increases the risk of IPV and affects the health of women and children. The research findings from this study will have implications in formulating policy and programs for IPV prevention strategies as well as maternal and child health improvement in Bangladesh and in other similar settings. Furthermore, findings from the research will also inform culturally specific educational programs on IPV for healthcare professionals, social workers, and for the women themselves in Bangladesh and other developing countries.

Pregnancy is one of the few times when almost all women need to visit health care settings on several occasions, thereby providing an opportunity for health professionals to identify IPV by routine enquiry, provide health-related services, and facilitate access to non-health support services (Jeanjot, Barlow, & Rozenberg, 2008; Martin & Garcia, 2011). Currently, Bangladesh does not have a screening protocol. The findings from this study will provide the basis for preparing nationally appropriate guidelines that would aid in the identification of women experiencing or at risk for IPV, and facilitate appropriate intervention including supportive referral and proper counseling by trained health care providers and social workers.

1.4 Research Questions

The research aims to answer two questions:

RQ1 How do pregnancy and the postpartum period influence the prevalence of IPV?

RQ2 Does IPV influence delayed entry into prenatal care, postpartum depression and mother’s exclusive breastfeeding?

1.5 Aims of the study

To address the first research question, this study broadly examines IPV victimisation during pregnancy among women in Bangladesh with specific aims to:

Aim-1: Examine IPV victimisation for pregnant women in Bangladesh.

| Aim 1.1 | : | Determine the prevalence of different forms of IPV before, during and after pregnancy; |

| Aim 1.2 | : | Examine the changing patterns of IPV victimisation before, during and after pregnancy; |

| Aim 1.3 | : | Identify and describe potential correlates of different types of IPV victimisation during pregnancy. |

To detail the impacts of IPV on the health of mothers and babies, the study addresses the following specific aims:

Aim-2: Explore the health consequences of IPV victimisation for pregnant women in Bangladesh.

1.6 Thesis framework

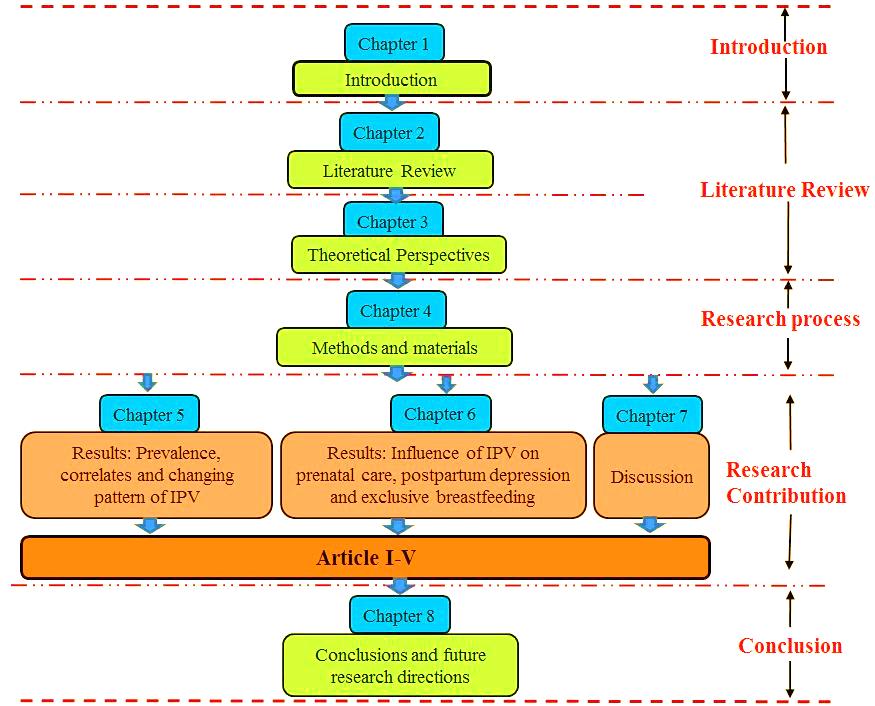

The thesis is structured in five portions including introduction, literature review, research process, research contribution and conclusion and consists of eight chapters (as shown in Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Thesis Framework

Introduction

Chapter 1 contextualises the problem of IPV during pregnancy and postpartum period. It explores the Bangladeshi context including the prevalence of IPV. This chapter also provides the purpose, objectives and research questions of the study.

Literature review

Chapter 2 presents a review of the available literature on IPV and pregnancy-prevalence and changing pattern of IPV both during and after pregnancy and potential correlates of IPV during pregnancy that has relevance with the cultural context of Bangladesh. It also elaborately illustrates direct and indirect consequences of IPV before, during and after pregnancy.

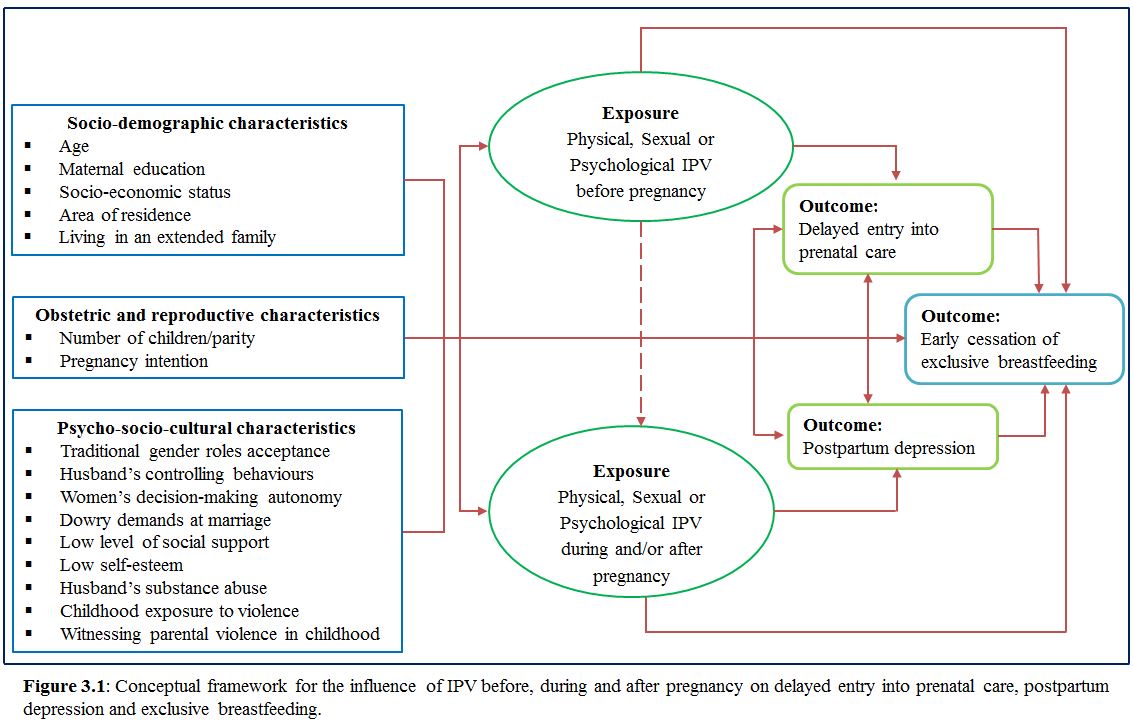

Chapter 3 depicts the contextual reasons for IPV victimization during pregnancy followed by the theoretical perspectives of IPV. Among theories, feminist theory, social learning theory and evolutionary psychological theory are elaborately explained. At the end of this chapter, a conceptual framework has been developed based on the theories and past literature of IPV.

Research process

Chapter 4 focuses the methodology of the study. This part consists of study design, data collection sites, sample of the study, detailed procedure in undertaking the study and research instruments. Finally, ethical considerations are highlighted in this chapter.

Research contribution

During the PhD candidature, the candidate made a considerable contribution to five published and unpublished peer-reviewed journal articles (two has already been published and three are under review), which confirms the originality of this research (presented in Chapter 5, 6 and 7, as shown in Table 1.1). Paper I addresses research aim 1.1 and 1.2. Paper II, III, IV and V address aim 1.3, 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3 respectively. The articles are listed as follows:

Table 1.1: Published and unpublished articles from this thesis

| Articles | Descriptions | Current status | |

| Paper I | : | Islam, M.J., Broidy, L., Mazerolle, P., and Baird, K. Exploring intimate partner violence before, during and after pregnancy in Bangladesh, Justice Quarterly. | Under review |

| Paper II | : | Islam, M.J., Mazerolle, P, Broidy, L., and Baird, K. Exploring the prevalence and correlates associated with intimate partner violence during pregnancy in Bangladesh, Journal of Interpersonal Violence. | Under review |

| Paper III | : | Islam, M.J., Broidy, L., Baird, K., and Mazerolle, P. (2017). Exploring the associations between intimate partner violence and delayed entry to prenatal care: Evidence from a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh, Midwifery. 47:43-55. | Published |

| Paper IV | : | Islam, M.J., Broidy, L., Baird, K., and Mazerolle, P. Intimate partner violence around the time of pregnancy and postpartum depression: The experience of women of Bangladesh, PLoS One. | Under review |

| Paper V | : | Islam, M.J., Baird, K., Mazerolle, P., and Broidy, L. (2017). Exploring the influence of psychosocial factors on exclusive breastfeeding in Bangladesh, Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 20 (1): 173-188. | Published |

Analytical results and significance of the findings are discussed in chapter 5–7.

Chapter 5 presents the analytical results of aim 1 (RQ1). Prevalence, potential risk factors of IPV during pregnancy, and changing pattern of IPV throughout the pregnancy are identified and described in this chapter.

Chapter 6 discusses the analytical results of aim 2 (RQ2). The influence of IPV on the timing of entry into prenatal care, postpartum depression and mother’s exclusive breastfeeding are explored in this chapter.

Chapter 7 discusses the significance of the findings outlined in chapter 5 and chapter 6 in light of past studies and theoretical frameworks.

Conclusion

To conclude, chapter 8 presents the summary of the core research findings extracted from the study. Having outlined the limitations of the research, the outlook for future research directions is also stated in this chapter.

Chapter 2

Literature Review: Prevalence, correlates and consequences of IPV during pregnancy |

The prevalence of IPV directed at pregnant women in both developed and developing countries remains elusive and varies widely from study to study depending on how IPV has been assessed. Variation in IPV prevalence estimates may be due to actual differences in the prevalence of violent acts within different study populations, as well as differences in methodologies, definitions and cultural aspects among studies that make it difficult to compare the results (Jasinski, 2004; Jeanjot, Barlow, & Rozenberg, 2008; Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010). With varied prevalence rates of IPV, a number of risk factors relevant to understanding the risk of IPV during pregnancy are also available in the literature. In the first part of this chapter, the prevalence of IPV during and after pregnancy, and the patterns of IPV experienced by pregnant women are discussed. Further, the factors that put women at risk for experiencing IPV during pregnancy and the negative consequences of IPV during pregnancy are demonstrated in the later part of this chapter.

2.1 Prevalence of IPV during pregnancy

Gazmararian et al.’s (1996) review, synthesizing the results of 13 studies from the USA and other developed countries reveals that the prevalence of IPV against pregnant women ranges from 0.9% to 20.6%, with most studies reporting estimates between 3.9% and 8.3% (Gazmararian et al., 1996; Martin, Mackie, Kupper, Buescher, & Moracco, 2001; Saltzman, Johnson, Gilbert, & Goodwin, 2003). Another review of six studies from developing countries (including India, China, Pakistan and Ethiopia) reports that the prevalence of IPV during pregnancy is between 4% and 29% (Nasir & Hyder, 2003). A review of 19 studies from some African countries has documented that 8 to 57.1% pregnant women experience IPV during pregnancy (Shamu, Abrahams, Temmerman, Musekiwa, & Zarowsky, 2011). Another systematic review consolidating findings from both developed and developing nations has documented the prevalence as 0.9-30% physical violence, 1-3.9% sexual violence, and 1.5-36% psychological violence during pregnancy (Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010). A recently published meta-analysis synthesizing the results of 92 studies from both developed and developing countries reports that the prevalence of IPV against pregnant women varies between 4.8% in China and 63.4% in Brazil (James, Brody, & Hamilton, 2013). This review also reveals that the prevalence of psychological IPV to be 28.4%, physical IPV to be 13.8% and sexual IPV during pregnancy to be 8%. Notably, the prevalence of IPV against pregnant women appears to be higher in African and Latin American countries compared to the Asian and European countries (Devries et al., 2010).

The literature contains mixed results concerning whether pregnancy is a vulnerable period for IPV and whether IPV escalates in severity during pregnancy. A number of factors are responsible for these discrepancies. First, IPV (e.g. physical, sexual, and/or psychological) has been defined differently from study to study (McMahon & Armstrong, 2012). IPV measurements that include multiple items and consider a number of different types of violence tend to result in the highest prevalence rates (Farid, Saleem, Karim, & Hatcher, 2008; Perales et al., 2009). Furthermore, IPV has been assessed with a range of instruments including the Conflict Tactics Scales, the Danger Assessment Scale, the Abuse Assessment Scale and the Index of Spouse Abuse, among other instruments. Second, the pregnancy period has been defined variously, up to one-year pre- or post-delivery (McMahon & Armstrong, 2012). Third, prevalence rates vary whether national or community samples are used, with community samples reporting more violence than national samples (Bailey & Daugherty, 2007; James, Brody, & Hamilton, 2013; Jasinski, 2004). Fourth, prevalence rates also vary whether population-based samples or hospital or clinic-based samples are used. Notably, population-based studies have found lower rates of IPV than hospital-based samples (Guo, Wu, Qu, & Yan, 2004b; James, Brody, & Hamilton, 2013; Janssen et al., 2003; Yost, Bloom, McIntire, & Leveno, 2005). Fifth, the prevalence is higher in low-income countries in comparison to high-income countries and within countries, it is higher in rural areas than in urban areas (Fanslow, Silva, Robinson, & Whitehead, 2008; Naved & Persson, 2008; Peek-Asa et al., 2011; Valladares, Pena, Persson, & Hogberg, 2005). Sixth, prevalence rates vary depending on the timing of inquiry (e.g. single point early in pregnancy vs. multiple points during pregnancy). Finally, the mode of inquiry (Self-administered questionnaire vs face-to-face interview) also plays an important role in estimates of prevalence rate. Higher prevalence rates have been associated with in-person interviews than self-administered questionnaire (Gazmararian et al., 1996).

Although the prevalence of IPV during pregnancy vary, it is clear that a significant number of women experience IPV during pregnancy. For this thesis, a comprehensive search of the current studies has been undertaken on the prevalence of IPV before, during and after pregnancy. The results are summarized in Table 2.1.

2.2 Prevalence of IPV during postpartum period

The postpartum period begins immediately after the birth of the baby and extends up to six weeks (WHO, 2014b) to six months after birth (Brown, Posner, & Stewart, 1999). Since most deaths occur during the postpartum period, WHO describes this period as the most critical and yet, the most neglected phase in the lives of mothers and babies (WHO, 2014b).

A number of studies have demonstrated that the risk of IPV associated with pregnancy is not only limited to the time between conception and birth, but also the period of one year before conception until one year after childbirth (Charles & Perreira, 2007; Jasinski, 2004; Martin et al., 2004; Saltzman, Johnson, Gilbert, & Goodwin, 2003; Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010). An increasing number of studies have shown that the postpartum period is also a time of increased risk for IPV victimisation (Ezechi et al., 2004; Hedin, 2000; Macy, Martin, Kupper, Casanueva, & Guo, 2007; Martin et al., 2004; Silva, Ludermir, de Araujo, & Valongueiro, 2011; Woolhouse, Gartland, Hegarty, Donath, & Brown, 2012). Previous studies have reported that IPV during the postpartum period ranges from 2–25% (Charles & Perreira, 2007; Gartland, Hemphill, Hegarty, & Brown, 2011; Hellmuth, Gordon, Stuart, & Moore, 2013; Saito, Creedy, Cooke, & Chaboyer, 2012; Silva, Valongueiro, Araújo, & Ludermir, 2015).

One longitudinal study has reported that the rates of psychological and sexual IPV are the highest during the first month after the birth of the infant (Macy, Martin, Kupper, Casanueva, & Guo, 2007). One study reports that the prevalence of physical IPV in the postpartum period is around eight times higher in women who have also experienced IPV during pregnancy as compared to those who have not (Moraes et al., 2011). Another study has revealed that physical IPV among young mothers is as high as 21.3% at 3 months postpartum, and 78% of these women have reported no IPV before pregnancy (Harrykissoon, Rickert, & Wiemann, 2002). In the same study, 75% of mothers experienced IPV during their pregnancies also reported IPV within 24 months following birth.

Table 2.1: Worldwide prevalence of IPV during pregnancy and postpartum period from previous research

| Author(s) (year) | Country/ Region | Setting | Sample Size | Type of Sample | Design | Instrument | Percentage | ||

| Before pregnancy/ lifetime | During pregnancy | After birth | |||||||

| (Scribano, Stevens, & Kaizar, 2013) | USA | P | 10,855 | First time and low-income mothers, ≥ 13 years old. | Longitudinal | AAS | 8.1 % | 4.7 % | 12.4 % |

| (Koenig et al., 2006) | USA | C | T1: 634

T2: 485 |

Pregnant women with HIV | Prospective, correlational (late pregnancy and 6 months postpartum) | Questionnaire | Not reported | 8.9% (physical or sexual) | 4.9% (physical or sexual) |

| (Dunn & Oths, 2004) | USA/ Alabama | H | 439 | Pregnant women, 20-34 years of age | Prospective, correlational | AAS | 15% | 10.9% (physical) | Not reported |

| (Daoud et al., 2012) | Canada | P | 6421 | Postpartum women (5-14 months), aged ≥15 years. | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire | 6% (physical & sexual) | 1.4% (physical & sexual) | 1% (physical & sexual) |

| (Heaman, 2005) | Canada/ Manitoba | H | 680 | Postpartum mothers | Cross-sectional | AAS | 9.1% (physical) 1.9% (sexual) Lifetime: 36.7% (physical, psychological) | 5.7% (physical) | Not reported |

| (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2004) | UK/Bristol Avon | P | 200 | Pregnant women, aged ≥16 years | Cross-sectional | AAS | 10.6% (physical) 23.4% (sexual) Lifetime: 23.5% (physical) | 3% (physical) 1% (sexual) | Not reported |

| (Bowen, Heron, Waylen, & Wolke, 2005) | UK/ Bristol Avon | P | 7591 | Pregnant mothers | Prospective longitudinal cohort (18 weeks of gestation, 8 weeks, 8 months, 21 months and 33 months postpartum) | Questionnaire | Not reported | 1% (physical) 4.8% (psychological) | 1.8% (physical) 7.3% (psychological) (at 8 months) |

| (Thananowan & Heidrich, 2008) | Thailand/ Bangkok | H | 475 | Pregnant women, aged ≥ 18 | Cross-sectional | AAS | 9.9% (Physical) 4.8% (sexual) | 4.8% (physical) | Not reported |

| (Perales et al., 2009) | Peru/ Lima | H | 2,392 | Postpartum mothers, 15 – 49 years age, | Cross-sectional | DHS Domestic Violence Module | Lifetime: 45.1% (any)34.2% (physical)8.7% (sexual)28.4% (psychological) | 21.5% (any) 11.9% (physical), 3.9% (sexual), 15.6% (psychological) | Not reported |

| (Farid, Saleem, Karim, & Hatcher, 2008) | Pakistan/ Karachi | H | 500 | Pregnant women, age 15-49 years. | Cross-sectional | WHO’s Domestic Violence Module. | 28.4% (physical) 49.8% (psychological) | 12.6% (physical) 43.2% (psychological) | Not reported |

| (Peedicayil et al., 2004) | India/Bhopal, Chennai, Delhi, Lucknow, Nagpur, Trivandrum and Vellore | P (Rural & Urban) | 9938 | Women of 15 to 49 years old who were living with a child younger than 18 years. | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire | 23% (physical) | 18% (physical) | Not reported |

| (Karaoglu et al., 2005) | Turkey/ Malatya | P (Urban & Rural) | 824 | Pregnant women | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire (developed from AAS) | 16.3% (physical), 8.5% (sexual) 30.8% (Psychological) | 8.1% (physical) 9.7% (sexual) 26.7% (Psychological) | Not reported |

| (Díaz-Olavarrieta et al., 2007) | Mexico/ Mexico City | H (public) | 1311 | Pregnant women, | Longitudinal (once in each trimester (<20 weeks, 20.1–36 weeks, >36.1 weeks) | A composite case record form adapted from AAS and other instruments. | 11.1% (physical and/or sexual) Lifetime: 41% (physical, sexual) | 7.6% (physical and/or sexual) 6.7% (physical) 1.8% (sexual) | Not reported |

| (Fawole, Hunyinbo, & Fawole, 2008) | Nigeria/ Abeokuta | H | 534 | Pregnant women, | Cross-sectional | A 21-item semi-structured questionnaire | 14.2% | 2.3% | Not reported |

| (Guo, Wu, Qu, & Yan, 2004b) | China/ Tianjing, Liaoning, Henan, and Shaanxi | P | 12,044 | Women with children aged 6–18 months | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire | 8.5% (physical, sexual) 4.2% (physical) 5.8% (sexual) | 3.6% (physical, sexual) 1.3% (physical) 2.8% (sexual) | 7.8% (physical, sexual) 3.8% (physical) 4.9% (sexual) |

| (Ludermir, Valongueiro, & Araújo, 2014) | Brazil/ Recife | C | 1,120 | Pregnant women of 18-49 years old | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire | Not reported | 31% (any type) 16.6% (psychological) | Not reported |

| (Van Parys, Deschepper, Michielsen, Temmerman, & Verstraelen, 2014) | Belgium/ Flanders | C | 1894 | Pregnant women, aged ≥ 18 | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire (developed from AAS) | 14.3% (overall) 2.3% (physical) 0.6 (sexual) 13.6 (psychological) | 10.6% (overall) 0.8% (physical) 0.5 (sexual) 10.1 (psychological) | Not reported |

| (Clark, Hill, Jabbar, & Silverman, 2009) | Jordan | C | 390 | Ever-married women who visited family planning clinics. | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire (developed from WHO’s Multi-Country Study) | 8% (physical) | 15% (physical) | Not reported |

| (Kabir, Nasreen, & Edhborg, 2014) | Bangladesh/ Mymensingh | P | T1=720

T2=660 |

Pregnant women | Longitudinal | Questionnaire (developed from WHO’s Multi-Country Study) | Lifetime 70% (physical) | 18% (physical) | 52% (physical) 65% (sexual) 84% (psychological) |

| (Mohammadhosseini, Sahraean, & Bahrami, 2010) | Iran/ Jahrom | C | 300 | Married women with a child aged 6 to 18 months | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire (developed from previous studies) | 52% (any type), 17% (physical), 21% (sexual) 42% (psychological) | 42% (any type) 10% (physical) 17% (sexual) 33% (psychological) | 54% (any type) 15% (physical) 25% (sexual) 43% (psychological) |

Note: P: Population-based, C= Clinic-based, H= Hospital-based, AAS: Abuse Assessment Screen, CTS2 = Conflict Tactics Scale 2,

2.3 Changing patterns of IPV during pregnancy

A debate continues in the literature whether pregnancy provides a time of protection or increased risk for IPV. Varied prevalence rates of IPV during pregnancy across literature have intensified the debate largely (Taylor & Nabors, 2009). Some argue that IPV may increase during pregnancy (Burch & Gallup Jr., 2004; Charles & Perreira, 2007; Clark, Hill, Jabbar, & Silverman, 2009; Martin et al., 2004; Mercedes & Lafaurie, 2015; Richardson et al., 2002), while other studies suggest that pregnancy may provide somewhat of a protective respite (Decker, Martin, & Moracco, 2004; Jasinski, 2001). Most of the studies have documented that the prevalence of IPV during pregnancy is consistently lower than IPV occurring before pregnancy, both in developed (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2004; Charles & Perreira, 2007; Datner, Wiebe, Brensinger, & Nelson, 2007; Dunn & Oths, 2004; Heaman, 2005; Janssen et al., 2003; Renker & Tonkin, 2006; Saltzman, Johnson, Gilbert, & Goodwin, 2003; Yost, Bloom, McIntire, & Leveno, 2005), and developing nations (Díaz-Olavarrieta et al., 2007; Farid, Saleem, Karim, & Hatcher, 2008; Guo, Wu, Qu, & Yan, 2004a, 2004b; Nasir & Hyder, 2003; Perales et al., 2009; Thananowan & Heidrich, 2008). For example, a study among a national sample of Canadian women has found that 8.2% of women have experienced IPV before pregnancy, 3.3% during pregnancy and 2.2% after childbirth (Daoud et al., 2012). Similarly, Koenig et al. (2006) have reported that the prevalence of IPV is 8.9% during pregnancy and 4.9% in the postpartum period.

IPV around the time of pregnancy has been categorized into four different patterns in the literature: (1) Commencement of IPV (no IPV before pregnancy, but violence during pregnancy), (2) Continuation of IPV (IPV both before and during pregnancy), (3) Termination of IPV (IPV before pregnancy, but no IPV during pregnancy), and (4) No IPV either before or during pregnancy (Agrawal, Ickovics, Lewis, Magriples, & Kershaw, 2014; Ballard et al., 1998; Van Parys, Deschepper, Michielsen, Temmerman, & Verstraelen, 2014). Gazmararian et al. (1996) have proposed two patterns of IPV among pregnant women as: (1) Chronic, where pre-existing IPV may either increase or decrease in severity and chronicity during pregnancy, and (2) Acute, where IPV starts for the first time during pregnancy. In a longitudinal study with pregnant women to assess IPV during the late pregnancy and 6 months postpartum, Koenig et al. (2006) have proposed three patterns of IPV, as: (1) abating pattern (during pregnancy only), (2) repeating pattern (during and after pregnancy), and (3) emerging pattern (after delivery only).

Past history of IPV before pregnancy is one of the strongest predictors of experiencing IPV during pregnancy (Martin, Mackie, Kupper, Buescher, & Moracco, 2001). Studies have revealed that the commencement of IPV during pregnancy is the least common pattern of IPV against pregnant women, between 4% and 40% of women experience IPV for the first time during pregnancy (Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010). On the other hand, between 31% and 69% of pregnant women with a past history of IPV have reported that IPV has ceased during their pregnancies (Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010). Moreover, the WHO multi-country study has revealed that women who were victims of IPV before pregnancy, 13–50% of women were physically abused for the first time during pregnancy, and 8–34% of women reported that the extent of the abuse was more severe and frequent during pregnancy (Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2005).

During pregnancy, there is a common pattern that the prevalence of psychological IPV is predominantly greater than the prevalence of physical IPV and sexual IPV, whereas the prevalence of sexual IPV is generally less than the prevalence of physical IPV (Castro, Peek-Asa, & Ruiz, 2003; Perales et al., 2009). Among three types of IPV, Physical IPV is relatively lower during pregnancy compared to other periods (Martin, Mackie, Kupper, Buescher, & Moracco, 2001; Scribano, Stevens, & Kaizar, 2013). However, in their longitudinal study, Macy et al. (2007) have revealed that women who have experienced physical IPV early in pregnancy always experience higher mean rates of each type of IPV during all of the time periods relative to women who do not report IPV at the beginning of their pregnancies.

The level of gender inequality within a society and cultural attitudes towards pregnancy may have an influence on IPV against pregnant women (Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010). In explaining why IPV is comparatively lower during pregnancy in comparison to before pregnancy, Van Parys et al. (2014) have reported three hypotheses: (a) pregnancy changes social status and increases social control and respect for the women; (b) a pregnant women is viewed as a receptacle for the vulnerable unborn baby, and use less physical and sexual IPV, and (c) during pregnancy, women themselves feel more vulnerable and in turn, use more strategies to avoid violent escalations. However, little is known about what factors contribute to the changing patterns, and why pregnancy appears to be a protective time for some women, while it is a period of increased risk for others (Macy, Martin, Kupper, Casanueva, & Guo, 2007; Silva, Ludermir, de Araujo, & Valongueiro, 2011; Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010; Van Parys, Deschepper, Michielsen, Temmerman, & Verstraelen, 2014).

2.4 Correlates of IPV during pregnancy

Correlates or factors associated with IPV during pregnancy are important to identify high-risk groups and illuminate intermediary factors in the causal pathway. Although there is no consensus as to the primary cause of IPV during pregnancy, several studies have attempted to identify some multiple social, economic, cultural, biological and environmental risk factors (Bohn, Tebben, & Campbell, 2004; Dunn & Oths, 2004; Hellmuth, Gordon, Stuart, & Moore, 2013; Karaoglu et al., 2005; Lipsky, Holt, Easterling, & Critchlow, 2005; McMahon & Armstrong, 2012; Saltzman, Johnson, Gilbert, & Goodwin, 2003). Factors that have been mentioned in different studies can be categorized into socio-demographic characteristics, obstetric and reproductive characteristics, and psycho-socio-cultural characteristics.

2.4.1 Socio-demographic characteristics

The socio-demographic correlates of age, maternal education, socio-economic status, area of residence and family status are illustrated in this section.

2.4.1.1 Age

A growing number of studies have shown that a relationship exists between young age and an increased risk of experiencing IPV during pregnancy (Datner, Wiebe, Brensinger, & Nelson, 2007; Farid, Saleem, Karim, & Hatcher, 2008; Heaman, 2005; Rådestad, Rubertsson, Ebeling, & Hildingsson, 2004; Thananowan, 2008; Thananowan & Heidrich, 2008; Valladares, Pena, Persson, & Hogberg, 2005). However, most of the studies use health facility-based samples rather than population-based samples and are limited in their generalizability (Brownridge et al., 2011; Jasinski, 2004). Some studies, on the other hand, have found no significant association between age and IPV victimisation during pregnancy IPV (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2004; Fanslow, Silva, Whitehead, & Robinson, 2008). Few studies have documented that older age is also a risk factor for experiencing IPV during pregnancy (Hedin, 2000; Horrigan, Schroeder, & Schaffer, 2000). However, several studies have shown that increasing age is protective for physical and psychological IPV (Naved & Persson, 2008; Ruiz-Pérez et al., 2006; Thananowan & Heidrich, 2008; Varma, Chandra, Thomas, & Carey, 2007). Therefore, it is difficult to draw a general conclusion regarding the association between age and an increased risk of experiencing IPV during pregnancy.

2.4.1.2 Maternal Education

Research reveals contradictory findings in examining the association between women’s education and the risk of experiencing IPV during pregnancy. While some studies demonstrate that illiteracy or low education increases the risk of IPV during pregnancy (Audi, Segall-Correa, Santiago, Andrade, & Perez-Escamilla, 2008; Charles & Perreira, 2007; Datner, Wiebe, Brensinger, & Nelson, 2007; Farid, Saleem, Karim, & Hatcher, 2008; Fikree, Jafarey, Korejo, Afshan, & Durocher, 2006; Hammoury, Khawaja, Mahfoud, Afifi, & Madi, 2009; Heaman, 2005; Khosla, Dua, Devi, & Sud, 2005; Perales et al., 2009; Thananowan & Heidrich, 2008), several others reveal no significant difference (Campbell, Poland, Waller, & Ager, 1992; Chan et al., 2011; Díaz-Olavarrieta et al., 2007; Fanslow, Silva, Robinson, & Whitehead, 2008; Perales et al., 2009; Tiwari et al., 2008). A study has demonstrated that women with less than 12 years of education are nearly 5 times more likely to experience IPV during pregnancy than women with more than 12 years of education (Saltzman, Johnson, Gilbert, & Goodwin, 2003).

2.4.1.3 Socio-economic status (SES)

In the literature, the association between low income and the risk of IPV victimisation during pregnancy is inconsistent. Some studies have reported that women with low income are likely to be at a greater risk for experiencing IPV during pregnancy (Daoud et al., 2012; Díaz-Olavarrieta et al., 2007; Fanslow, Silva, Robinson, & Whitehead, 2008; Heaman, 2005; Perales et al., 2009; Ruiz-Pérez et al., 2006; Thananowan & Heidrich, 2008). In contrast, several studies find no significant difference in terms of household income between abused and non-abused pregnant women (Dunn & Oths, 2004; Farid, Saleem, Karim, & Hatcher, 2008; Lau, 2005; Leung, Leung, Lam, & Ho, 1999; Muthal-Rathore, Tripathi, & Arora, 2002). Quite surprisingly, while Varma et al. (2007) have shown that higher household income increases the risk of IPV victimisation during pregnancy; Fanslow et al. (2008) have reported that higher household income decreases the risk of experiencing IPV during pregnancy.

To assess the relationship between SES and the risk of IPV during pregnancy, these studies have directly used household income (Dunn & Oths, 2004; Sagrestano, Carroll, Rodriguez, & Nuwayhid, 2004) or proxy socioeconomic indicators [e.g. Medicaid or WIC participation (special supplemental food program for women, infants and children): a proxy measure of lower SES] (Gazmararian et al., 1995; Goodwin et al., 2000; Saltzman, Johnson, Gilbert, & Goodwin, 2003). For example, Saltzman et at. (2003) revealed that Medicaid recipients were 4.2 times more likely to be abused during pregnancy compared with non-Medicaid recipients. Pregnancy or the childbirth may intensify existing strains such as low socioeconomic status, which in turn may increase the stress level in the family and the risk of IPV (Jasinski, 2004).

2.4.1.4 Area of residence

There is no concrete evidence in the literature to get an idea regarding the association of area of residence (rural/urban) with the risk of IPV victimisation during pregnancy. Rural women may have more limited access to health care and social services than urban women, which may be a potential determinant of IPV victimisation during pregnancy (Brownridge et al., 2011). Some studies have found that the place of residence is not significantly associated with IPV, which may indicate that IPV is a serious social issue both in urban and rural areas (Daoud et al., 2012; Salari & Nakhaee, 2008).

2.4.1.5 Family status

While a few studies have found a positive relationship between living in an extended family and higher risk for experiencing violence during pregnancy (Mohammadhosseini, Sahraean, & Bahrami, 2010), at least one study has documented a negative relationship (Koenig, Ahmed, Hossain, & Mozumder, 2003).

In the culture of many traditional Asian societies, a newly married woman moves into her male partner’s household, which is generally an extended or joint family encompasses her husband’s parents and siblings. In these extended families, the mother-in-law commonly exercises power and control over household matters and the daughter-in-law is expected to carry out all her instructions and household chores (Gausia, Fisher, Ali, & Oosthuizen, 2009). During pregnancy, if the daughter-in-law fails to perform her household tasks because of her physical weakness or illness, in-laws often instigate violence. A study with Pakistani pregnant women reported that presence of in-laws is the most common reason for marital conflicts in the family (Fikree & Bhatti, 1999). A limited number of studies have shown a positive relationship between IPV victimisation and in-law-conflict or poor relationship with in-laws (Chan et al., 2011). Conversely, Naved and Persson (2008) have not found any association between spousal violence during pregnancy and living with one’s in-laws. Although the presence of in-laws in the household may create some conflict, at the same time they may prevent IPV as well (Naved & Persson, 2005).

2.4.2 Obstetric and reproductive characteristics

The obstetric and reproductive correlates of number of children/parity and pregnancy intention are discussed in this section.

2.4.2.1 Number of children/parity

Some studies have indicated that multiparous women are more likely to experience IPV during pregnancy than those pregnant with their first child (Farid, Saleem, Karim, & Hatcher, 2008; Heaman, 2005; Mohammadhosseini, Sahraean, & Bahrami, 2010; Muhajarine & D’Arcy, 1999; Ruiz-Pérez et al., 2006; Salari & Nakhaee, 2008; Tiwari et al., 2008). Farid et al. (2008) have shown an independent association between the number of living children and physical and/or emotional IPV victimisation among Pakistani pregnant women, with each additional child increases the risk of IPV victimisation by 34%. A study from Iran has shown that multiparous women are up to 7 times more likely to experience IPV during pregnancy than primiparous women (Salari & Nakhaee, 2008). The reason behind these outcomes may be that many children intensify the existing socioeconomic stress of the family. In contrast, a range of studies has found no significant difference between parity and the likelihood of experiencing IPV during pregnancy (Charles & Perreira, 2007; Díaz-Olavarrieta et al., 2007; Dunn & Oths, 2004; Srinivasan & Bedi, 2007).

2.4.2.2 Pregnancy intention

Previous studies have revealed an association between pregnancy intention and the increased risk for IPV victimisation during pregnancy. A growing number of studies have found that unintended or unplanned pregnancy is significantly correlated with higher risk for experiencing IPV during pregnancy (Charles & Perreira, 2007; Cripe et al., 2008; Fanslow, Silva, Whitehead, & Robinson, 2008; James, Brody, & Hamilton, 2013; Mercedes & Lafaurie, 2015; Okenwa, Lawoko, & Jansson, 2011; Pallitto et al., 2013; Perales et al., 2009; Raihana, Shaheen, & Rahman, 2012; Salari & Nakhaee, 2008; Tiwari et al., 2008). A few studies, on the other hand, find no significant association between unintended pregnancy and the risk for IPV victimisation during pregnancy (Martin & Garcia, 2011).

Salari & Nakhaee (2008) has shown that unintended pregnancy in Iran is the most significant associated factor for IPV victimisation during pregnancy, carrying an adjusted odds ratio of 7.7. Goodwin et al. (2000) have indicated that women with unintended pregnancies in the United States are approximately 2.5 times more likely to have been physically abused than women with intended pregnancies. Couples expecting an unplanned or unwanted child may be facing a greater level of stress compared to those couples who have children that were planned, consequently elevate the risk for IPV victimisation (Jasinski, 2004). Moreover, a pregnancy not planned by the male partner might mean something that he could not control and therefore increases the risk for IPV against his spouse (Jasinski, 2004).

2.4.3 Psycho-socio-cultural characteristics

The psycho-socio-cultural correlates of traditional gender roles acceptance, husband’s controlling behaviours, women’s decision-making autonomy, dowry demands at marriage, low level of social support, low self-esteem, husband’s substance abuse and childhood exposure to violence are examined in this section.

2.4.3.1 Traditional gender roles acceptance

Cross-cultural research of IPV suggests that it widely occurs in male-dominant, patriarchal social structures where societies support higher levels of inequality between male and female, and where highly conservative attitudes towards traditional gender roles may lead to endorsement and acceptance of IPV (Fulu et al., 2013; Jewkes, 2002; Okenwa, Lawoko, & Jansson, 2009). Traditional gender constructions limit women’s responsibilities to maintain exclusively the household through housework, childbearing and child caring. In contrast, the social acceptability of male domination reinforces the belief that men should be the breadwinner with the prime decision-making authority as the head of the family. Feminist theorists consider traditional gender roles to be the principal breeding ground for IPV in patriarchal societies because it gives superiority to male over female (Clark, Hill, Jabbar, & Silverman, 2009; Flood & Pease, 2009; Stark, 2007; Walker, 2009). Notably, gender roles attitudes act as socio-cultural tools for the intimidation and control of women (Islam, Broidy, Baird, & Mazerolle, 2017).

Studies from countries with traditional gender constructions indicate that physical violence is seen to be normatively acceptable when a wife is perceived to be disobedient, and when she fails to conform to certain traditional gender role expectations (Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006; Hadi, 2005; Healey, Smith, & O’Sullivan, 1998; Sugarman & Frankel, 1996). Furthermore, evidence suggests that societal norms, such as male dominance and female subjugation and subordination become internalized and integrated into the culture so much so that women themselves support a man’s right to beat his wife under certain circumstances (Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006; Jewkes, 2002; Uthman, Moradi, & Lawoko, 2009). Existing literature also reveals a positive relationship between traditional gender roles attitudes and tolerant views of IPV (Dobash & Dobash, 1979; Haj-Yahia, 1998; Straus, Gelles, & Steinmetz, 1980; Sugarman & Frankel, 1996; Willis, Hallinan, & Melby, 1996).

Women’s conservative attitude towards traditional gender roles is rarely evaluated as a determinant for IPV during pregnancy (Clark, Hill, Jabbar, & Silverman, 2009). A few studies demonstrated that traditional attitudes towards gender roles, such as the belief that men should be the head of the family and women should be the homemakers, or that women should be always emotionally and physically available to men, are correlated with victimisation and perpetration of IPV during pregnancy (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2006; Brownridge et al., 2011; Burch & Gallup Jr., 2004; Pallitto, Campbell, & O’campo, 2005). During pregnancy, women may be unable to perform their traditional roles as homemaker/caretaker due to reduced mobility, increased tiredness and a lack of emotional availability, which may induce increased IPV by abusers who tend to hold more conventional sex role attitudes (Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010).

2.4.3.2 Husband’s controlling behaviours

There is a dearth of research on the impact of husband’s controlling behaviours on the risk of IPV during pregnancy (Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010). Limited evidence suggests that male partners may be more prone to abusive behaviour in the presence of jealousy or suspicion of infidelity, especially during pregnancy (Goetz, Shackelford, Romero, Kaighobadi, & Miner, 2008; Harris, 2003; Hellmuth, Gordon, Stuart, & Moore, 2013). Men want to control female sexuality and to prevent predicted infidelity (Buss & Shackelford, 1997; Cousins & Gangestad, 2007; Pallitto & O’Campo, 2005), and use violence as a controlling strategy (Buss & Duntley, 2011). Notably, paternal uncertainty and accusations of infidelity have been linked to an increased risk for experiencing IPV among pregnant women (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2006; Burch & Gallup Jr., 2004; Chambliss, 2008; Pallitto & O’Campo, 2005). Burch and Gallup (2004) suggest that the male constantly monitors his partner or isolates her from other men so as to be sure that the child she bears is his own. Therefore, men may develop paternal assurance tactics, such as the use of IPV to establish control, to combat paternal uncertainty and to make sure that the children he raises are his own (Brownridge et al., 2011).

In a study from the U.S, 43% of women experiencing IPV during pregnancy have reported that their partner regulated all their activities in the year prior to pregnancy onset (Decker, Martin, & Moracco, 2004). Moreover, financial control by restricting access to money has been reported by women who have experienced IPV during pregnancy (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2006; Pulido, 2001). Sexual jealousy and possessiveness, financial control and social isolation from family and friends are some of the male partner’s controlling behaviours that are inflicted upon the pregnant women (Brownridge et al., 2011).

2.4.3.3 Women’s decision-making autonomy

Cross-cultural research of IPV demonstrates that women whose husbands have the final authority in household decisions are more likely to experience physical, sexual and psychological IPV (Morash, Bui, Zhang, & Holtfreter, 2007; Rani & Bonu, 2009; Uthman, Moradi, & Lawoko, 2009; Zhu & Dalal, 2010). All forms of IPV were found to be least common among couples when they hold joint autonomy in household decisions, and when women had decision-making power on spending her own earnings (Uthman, Moradi, & Lawoko, 2009; Zhu & Dalal, 2010). It is undebated that abused women commonly have less decision-making power, limited freedom of movement and higher financial dependency on their male partners (Ellsberg, Peña, Herrera, Liljestrand, & Winkvist, 2000; Smith & Martin, 1995). Women’s low decision-making autonomy is an important component of the feminist theory that reflects a power and control motive.

2.4.3.4 Dowry demands at marriage

A number of studies have found that payment of dowry (the bride’s family commits to provide large sums of money, jewellery, and other goods to the groom or groom’s family at marriage) is associated with IPV in some developing countries, especially in South Asian countries (Hasan, Muhaddes, Camellia, Selim, & Rashid, 2014; Naved, Azim, Bhuiya, & Persson, 2006; Naved & Persson, 2008; Peedicayil et al., 2004). There is a common tendency in those societies to consider dowry as groom price (Taher, Islam, Chowdhury, & Siddiqua, 2014) that may be an indicator of patriarchal attitude (Naved & Persson, 2010). Dissatisfaction with non-payment or inadequate dowry payment usually leads to conflict between the couple after marriage, and substantially contributes to IPV[2], though giving and taking dowry is legally prohibited (Babu & Kar, 2010; Barnett, Miller-Perrin, & Perrin, 2005; Naved & Persson, 2010; Odhikar, 2014; Taher, Islam, Chowdhury, & Siddiqua, 2014). Brides families offer dowry for their daughters, especially when daughters are not beautiful by conventional and cultural norms (Hasan, Muhaddes, Camellia, Selim, & Rashid, 2014). Thus, dowry completely demolishes the dignity of women, and makes them very vulnerable to IPV (Taher, Islam, Chowdhury, & Siddiqua, 2014). Marriage involved dowry demands are positively associated with IPV during pregnancy in rural areas of Bangladesh (Naved & Persson, 2008) and India (Peedicayil et al., 2004).

2.4.3.5 Low level of social support

A lack of social support from friends, family and significant others have been linked with an increased risk of IPV victimisation during pregnancy (Farid, Saleem, Karim, & Hatcher, 2008; Jeanjot, Barlow, & Rozenberg, 2008; Peedicayil et al., 2004; Ruiz-Pérez et al., 2006; Valladares, Pena, Persson, & Hogberg, 2005). Past studies have revealed that abused pregnant women report being socially isolated from family, friends and other social support networks by their male partners due to jealousy of other close relationships (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2006; Noel & Yam, 1992; Pulido, 2001; Wiemann, Agurcia, Berenson, Volk, & Rickert, 2000). Besides, abused pregnant women have reported both lower level of social support from others and from their male partners compared to non-abused pregnant women (Heaman, 2005). It may be due to that a male partner’s attempt to socially isolate his female partner may decrease her social support networks, and in turn, increase the dependence on the male partner (Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010). Conversely, other research has not found significant differences in the social support networks of abused and non-abused pregnant women (Chan et al., 2011; Charles & Perreira, 2007; Dunn & Oths, 2004).

2.4.3.6 Low self-esteem

Previous studies have documented an association between low self-esteem and the increased risk for experiencing IPV during pregnancy (Loft Abadi, Ghazinour, Nojomi, & Richter, 2012). In abusive relationships, the abused women were found to have a lower self-esteem and were more likely to report physical, sexual and psychological aggression compared to women with higher self-esteem (Salari & Baldwin, 2002). A woman’s lowered sense of self-esteem creates a feeling of guilt, shame, unworthiness, helplessness, powerlessness and a negative perception of the self that ultimately increase her frustration, depression, motivational impairment of problem-solving ability and isolation from others (Bell & Mattis, 2000; Deyessa et al., 2009; Mechanic, Weaver, & Resick, 2008). As a consequence, she may no longer enjoy her intercommunication with her husband and significant others (Stewart, 2007), suggesting that a lowered sense of self-esteem makes women unworthy of being loved by others which in turn increases a woman’s risk of IPV victimisation (Bell & Mattis, 2000). Moreover, the feeling of unworthiness and powerlessness generates fear of being alone within abused women, which in turn prevents women from leaving the abusive relationship (Bell & Mattis, 2000).

2.4.3.7 Husband’s substance abuse

IPV during pregnancy is associated with the use of tobacco, alcohol, and/or illicit drugs. Although a number of studies have found a strong relationship between pregnant women’s substance abuse and the increased risk for IPV victimisation (Bailey & Daugherty, 2007; Certain, Mueller, Jagodzinski, & Fleming, 2008; Charles & Perreira, 2007; Datner, Wiebe, Brensinger, & Nelson, 2007; Lipsky, Holt, Easterling, & Critchlow, 2005), few studies so far have documented the relationship between the husband’s substance abuse and the risk of perpetrating IPV against a woman during pregnancy (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2006; Díaz-Olavarrieta et al., 2007; McFarlane, Parker, & Soeken, 1995; Muhajarine & D’Arcy, 1999; Wiemann, Agurcia, Berenson, Volk, & Rickert, 2000). Other than alcohol use, male partners’ illicit drug abuse also significantly increases the odds of IPV against a pregnant partner (Amaro, Fried, Cabral, & Zuckerman, 1990; Charles & Perreira, 2007).

2.4.3.8 Childhood exposure to violence

Previous history of violence in the families of origin of either partner has an impact on degrees of adult perpetration and victimization because it is often transmitted across generations through the socialisation process (Brownridge et al., 2011; Flood & Pease, 2009; Zhu & Dalal, 2010). However, it has not been fully explored whether childhood exposure to violence is associated with the risk of IPV during pregnancy. Very few studies have demonstrated that women who witnessed or experienced violence during their childhood are more likely to experience IPV during pregnancy (Castro, Peek-Asa, & Ruiz, 2003; Clark, Hill, Jabbar, & Silverman, 2009; Farid, Saleem, Karim, & Hatcher, 2008; Guo, Wu, Qu, & Yan, 2004a; Naved & Persson, 2008). Naved and Persson (2008) found that spousal abuse of a woman’s mother or mother-in-law is one of the strongest predictors of her risk for experiencing IPV during pregnancy by her husband.

2.5 Consequences of IPV during pregnancy

Studies from the developed and developing countries have generated increasing evidence that IPV during pregnancy is a serious public health concern with consequences for the health and well-being of the mother, the developing fetus and the baby during pregnancy, at birth and during the postpartum period (Brown, McDonald, & Krastev, 2008; Han & Stewart, 2014; Howard, Oram, Galley, Trevillion, & Feder, 2013; Jasinski, 2004; Kendall-Tackett, 2007; Trabold, Waldrop, Nochajski, & Cerulli, 2013; Van Parys, Verhamme, Temmerman, & Verstraelen, 2014). These devastating effects generally have long lasting consequences on the emotional well-being of victims and may prevail well after the IPV has ended (Campbell, 2002; Trabold, Waldrop, Nochajski, & Cerulli, 2013). Some of the negative consequences of IPV during pregnancy for women and their children are presented in this section.

2.5.1 Injuries and physical health outcomes

Victims of IPV usually report negative physical health effects such as chronic health conditions, poor quality of life and increased use of health care services (Campbell, 2002). The mean medical cost per incident of physical assault in the US is US$548 which may rise to US$2,665 if all medical services are sought (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2003). IPV is one of the leading causes of injury in women (Campbell, 2002). Women experiencing IPV during pregnancy report being kicked, punched, threatened with knives, choked, scalded and having objects thrown at them (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2006). Along with a number of IPV-related injuries, including cuts, bruises to the face, neck, chest and abdomen, fractures, concussions, dental injuries, stab wounds, pneumothorax, performed eardrums, women also report to have vaginal bleeding and persistent headaches as a result of the IPV they experience (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2006; Rachana, Suraiya, Hisham, Abdulaziz, & Hai, 2002; Sharps, Laughon, & Giangrande, 2007). Studies have reported that IPV during pregnancy is a risk factor for antepartum hospitalization (Kaye, Mirembe, Bantebya, Johansson, & Ekstrom, 2006), and 10% of hospitalizations during this period are the result of intentional injuries due to IPV against the pregnant woman (Chambliss, 2008).

Other adverse outcomes include general poor health, high blood pressure, diabetes, asthma, cardiovascular problem, gastrointestinal, frequent kidney infections and urinary tract infection (Dillon, Hussain, Loxton, & Rahman, 2013; Rachana, Suraiya, Hisham, Abdulaziz, & Hai, 2002). Sexual IPV can lead to an increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases, pelvic inflammatory disease, sexual dysfunction, bladder infections and other gynaecological health problems (Campbell & Lewandowski, 1997). Women who are victims of sexual IPV with or without physical IPV are more likely to report gynaecological health problems than women who experience physical IPV only, or those who have never abused (Stenson, 2004; Stephenson, Koenig, & Ahmed, 2006). Studies also have reported that self-perceived poor health status is significantly associated with IPV (Ellsberg, Jansen, Heise, Watts, & Garcia-Moreno, 2008; Ishida, Stupp, Melian, Serbanescu, & Goodwin, 2010; Nur, 2012; Yoshihama, Horrocks, & Kamano, 2009).

2.5.2 Mental health outcomes

A growing number of studies have demonstrated that IPV during and after pregnancy is associated with maternal mental health complexities such as anxiety disorders, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, low self-esteem, negative self-image, less life satisfaction, functional impairment and fear of intimacy (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2006; Chambliss, 2008; Escribà-Agüir, Ruiz-Pérez, & Saurel-Cubizolles, 2007; Jeanjot, Barlow, & Rozenberg, 2008; Martin, Li, Casanueva, Britt, & Kupper, 2006; Murphy & Ouimet, 2008; Pallitto, Campbell, & O’campo, 2005; Romito, Pomicino, Lucchetta, Scrimin, & Molzan Turan, 2009; Zlotnick, Johnson, & Kohn, 2006). These mental health problems often co-occur (Ogbonnaya, Kupper, Martin, Macy, & Bledsoe-Mansori, 2013). Martin and colleagues (2006) have revealed that women who have experienced multiple forms of IPV (physical, sexual and/or psychological) before or during pregnancy are at a greater risk for psychological distress and depression compared to non-victims. It is estimated that the cost for women who seek mental health care after being abused is US$269 per incident of IPV in the US, while the cost rises to US$1017 if victims seek a full set of mental health care visits (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2003).

Other related complications of IPV during pregnancy are prenatal substance use or abuse including tobacco, alcohol, prescription drugs and illicit drugs (Datner, Wiebe, Brensinger, & Nelson, 2007; Heaman, 2005; Lipsky, Holt, Easterling, & Critchlow, 2005; Pallitto, Campbell, & O’campo, 2005; Sarkar, 2008), and suicide (Karmaliani et al., 2008; Naved & Akhtar, 2008; Shadigian & Bauer, 2004). Women who have experienced IPV, and have attempted suicide reports higher levels of sadness, self-dislike, feeling of worthlessness and suicidal thoughts (Houry, Kaslow, & Thompson, 2005). A number of women who are abused during pregnancy hold themselves responsible for their partner’s abusive behaviour (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2006), and as a consequence report perceived stress (Valladares, Ellsberg, Peña, Högberg, & Persson, 2002). The WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women reports that memory loss, problems with concentration and dizziness are significantly associated with lifetime experiences of IPV across all the study sites (Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2005).

Considering the severity and frequency, the more severe and/or the more frequent the experience of IPV, the more severe the symptomatology of mental health complications appears to be, suggesting a dose-response association between IPV victimisation and depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation (Dillon, Hussain, Loxton, & Rahman, 2013). These mental health complexities not only affect the quality of life for the new mothers but also their daily functioning in the postpartum period (Martin, Li, Casanueva, Britt, & Kupper, 2006; Rådestad, Rubertsson, Ebeling, & Hildingsson, 2004).

2.5.3 Pregnancy outcomes

IPV beforeor during pregnancy may affect pregnancy outcomes through direct and indirect mechanisms (Koski, Stephenson, & Koenig, 2011; Shah & Shah, 2010).The most studied pregnancy outcome due to IPV is low birth weight (LBW) of babies (Kaye, Mirembe, Bantebya, Johansson, & Ekstrom, 2006; Murphy, Schei, Myhr, & Du Mont, 2001; Saltzman, Johnson, Gilbert, & Goodwin, 2003; Sarkar, 2008; Shah & Shah, 2010). A meta-analysis of studies across the USA and Canada demonstrated that women who report experiencing IPV during pregnancy are 40% more likely to give birth to an LBW baby (Murphy, Schei, Myhr, & Du Mont, 2001).It has been suggested that there is a relationship between IPV and stress. An increase in stress is thought to lead to increased levels of cortisol, which has been linked to LBW babies (Valladares, Peña, Ellsberg, Persson, & Högberg, 2009). LBW is one of the most significant risk factors of infant ill-health and mortality during the first year of life.

IPV is also significantly linked to other adverse pregnancy outcomes such as unwanted pregnancy, low prenatal weight gain (McFarlane, Campbell, Sharps, & Watson, 2002; Shadigian & Bauer, 2004), preterm delivery (Rachana, Suraiya, Hisham, Abdulaziz, & Hai, 2002; Sarkar, 2008; Shah & Shah, 2010), miscarriage/abortion (Jewkes, Penn-Kekana, Levin, Ratsaka, & Schrieber, 2001; Silverman, Gupta, Decker, Kapur, & Raj, 2007), placental abruption, fetal injury and perinatal death (Janssen et al., 2003; Sarkar, 2008; Shadigian & Bauer, 2004; Van Parys, Verhamme, Temmerman, & Verstraelen, 2014). Sexual IPV can cause vaginal infection which in turn increases the risk of preterm rupture of membranes and preterm delivery (Moodley & Sturm, 2000).

2.5.4 Maternal health service utilization

Although service accessibility (Rahman, Mosley, Ahmed, & Akhter, 2008)demographic (Chakraborty, Islam, Chowdhury, & Bari, 2002; Chakraborty, Islam, Chowdhury, Bari, & Akhter, 2003; Rai, Singh, Singh, & Kumar, 2014) and socio-economic factors (Amin, Shah, & Becker, 2010; Navaneetham & Dharmalingam, 2002; Paul & Rumsey, 2002; Rahman, Mosley, Ahmed, & Akhter, 2008; Rai, Singh, Singh, & Kumar, 2014) are notable in affecting when, where and how often women receive maternal health care services; research has begun to investigate the influence of other psychosocial risk factors. Scholars have proposed that IPV might introduce unique risks that negatively affect women’s reproductive behaviour and utilization of health care services such as prenatal care (Bailey & Daugherty, 2007; Moraes, Arana, & Reichenheim, 2010; Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010). Several studies have revealed that women who experience IPV during pregnancy are more likely to receive inadequate prenatal care (Heaman, 2005; Lipsky, Holt, Easterling, & Critchlow, 2005) and entry into prenatal care late (Bailey & Daugherty, 2007; Goodwin et al., 2000; Huth-Bocks, Levendosky, & Bogat, 2002; Jasinski, 2004; McCloskey et al., 2007; McFarlane, Campbell, Sharps, & Watson, 2002; Sharps, Laughon, & Giangrande, 2007) compared to non-abused women.

Survivors of IPV are also reported to have a lack of family support, restricted access to health services, strained relationship with health care providers and employers, and isolation from social networks (Heise & Garcia-Moreno, 2002). Additionally, IPV can compromise women’s health seeking behaviour due to the associated mental and emotional health impairments such as trauma, chronic pain, stress, depression, anxiety, dizziness, functional disorders and other mental health problems (Coker, Smith, Bethea, King, & McKeown, 2000; Ellsberg, Jansen, Heise, Watts, & Garcia-Moreno, 2008), which may limit women’s energy to take appropriate health care measures. Delayed entry in seeking maternal health care services may be due to either controlling behaviour by the perpetrator (Dietz et al., 1997; Koski, Stephenson, & Koenig, 2011; Taggart & Mattson, 1996) or fear of exposing obvious signs of physical violence, such as black eyes or bruises (Taggart & Mattson, 1996).

2.5.5 Maternal-child bonding

IPV may have adverse effects on women’s mental health during pregnancy and after delivery (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2004; Bonomi et al., 2006; Romito, Molzan Turan, & De Marchi, 2005). Studies have demonstrated associations between maternal depression and disturbances in mother-child interactions (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000). Depressed mothers are more likely to express behaviours that have a long-term emotional, cognitive, intellectual and developmental problem in children (Cooper & Murray, 1998; Hart, Field, & Nearing, 1998; Murray, Fiori‐Cowley, Hooper, & Cooper, 1996; Wachs, Black, & Engle, 2009; Weinberg & Tronick, 1998). Furthermore, IPV during pregnancy significantly affects maternal-child bonding, fetal brain development and breastfeeding practices (Janssen et al., 2003; Jasinski, 2004; Sarkar, 2008; Sharps, Laughon, & Giangrande, 2007; Trabold, Waldrop, Nochajski, & Cerulli, 2013). A mother experienced IPV will likely to expend most of her time and energy coping with ongoing violence, rather than focus on bonding and caring for her baby. Additionally, a depressed mother may be tired, unable to concentrate and preoccupied with feelings of guilt, worthlessness and hopelessness, and consequently, may no longer enjoy her interaction with her child (Stewart, 2007).

2.5.6 Homicide