Self-care for Single Mission Workers

Info: 9573 words (38 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Tagged: ReligionHealth and Social Care

The purpose of this chapter is to set the topic of self-care for single mission workers in the context of the member care literature available.

Despite there being abundance of literature available on singleness in the church context or on dating, there is limited literature available relating to singles in the context of missions. The same applies for self-care in that while there are scarce resources on this particular topic, there is a range of materials available relating to resilience, spiritual life, emotional life and physical care.

First, I review the wider member care context, including the Biblical basis for member care and self-care, and how self-care fits within this context. In light of these topics, I review the more common challenges and opportunities for singles in mission within the areas of spiritual, emotional and physical well-being. Subsequently, I explore the area of single workers in mission. Finally, the organisational response to member care and self-care will also be examined.

Member care can be defined in broad terms, but importantly, as having a flow of care that enables mission workers to thrive in their ministry contexts. Gardner (2015, p.15) provides an all-encompassing definition of member care as “doing whatever it takes, within reason” to ensure that mission workers are well supported and cared for, being resourced and equipped for life and ministry from recruitment through to the end of their service or retirement.

Spruyt and Schudel’s definition of biblical member care concurs with the above in that “it is about helping people to be fruitful, strong, resilient, purposeful, loving and Christ‐centered as they seek to fulfill His call upon their lives” (2012, p.1). The source of this care comes from God with the expectation that we will then care for each other (Gardner, 2015, p.16; Taylor, 2002, p.56). Gardner (2015, pp.16-18) also provides various examples of how the Bible illustrates Jesus showing his care for his followers and how he expected them to show care for one another including the 55 ‘one another’ commands in the New Testament, such as ‘love one another’ in John 13:34-35.

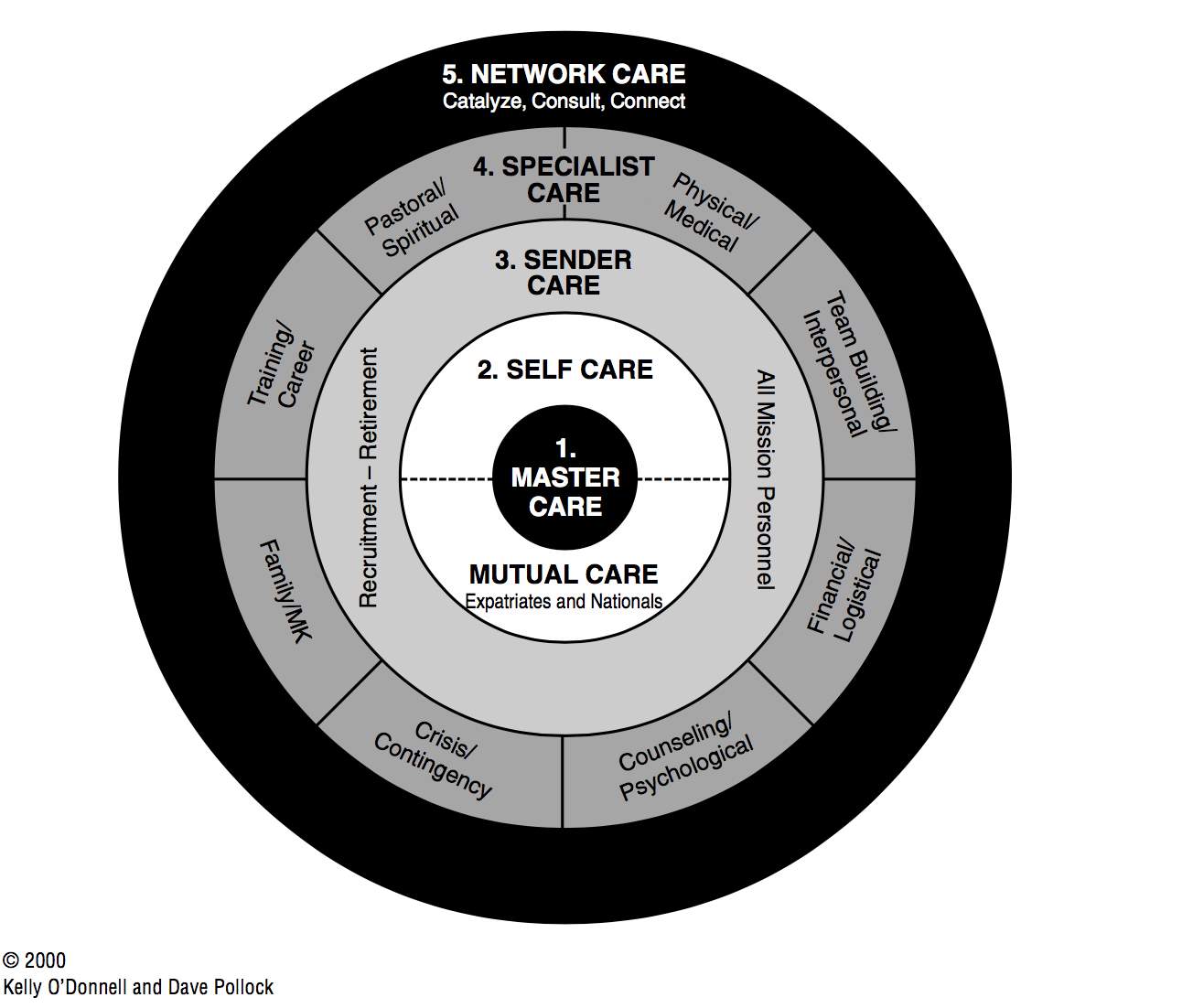

These definitions, I believe, allow for both organisations and individual workers to be responsible for member care. However, in my opinion, Gardner’s definition appears to lean more heavily towards organisational care as being a primary source of member care. The following diagram shows the well-known member care model developed by O’Donnell, Pollock and Foyle (O’Donnell, 2002, p.16), which I consider provides a more balanced model for member care as the different spheres “flow into and influence each other” (O’Donnell, 2002, p.15).

Figure 1: Member Care Model, ‘Doing Member Care Well’, O’Donnell, 2oo2

Master care is rightly at the core of the model, however, self-care and mutual care can be seen as a necessary and vital element of member care, along with sender care. I believe that it is profoundly important that mission workers take responsibility, under God, for their own care, recognising the need to ask for help, and acknowledging the need for self-care in their individual situations.

So, what is self-care and why is it important?

In the secular world, self-care has been described as “our culture’s latest therapeutic panacea” (Rosen, 2016) or as a new buzzword as interest in the topic has increased. Apparently, Google internet searches for the term ‘self-care’ reached a five-year high immediately following the US Presidential election in November 2016 (Mahdawi, 2017). Mahdawi (2017) appears quite derogatory about self-care stating that

as with many zeitgeisty phrases (think: “clean-eating” or “wellness”), the vogue-ishness comes with a certain vagueness. Self-care seems to mean anything and everything: if an activity (or inactivity) makes you feel better, in body or mind, then it’s self-care.

However, the French philosopher Michel Foucault argued that the ancient Greeks saw self-care as “integral to democracy as it was a necessary part of care for others. It made you a better, more honest citizen” (as cited in Mahdawi, 2017).

A significant proportion of Google searches on the term ‘self-care’ relate to mental health care. The Self-Care Forum (2018) defines self-care as “the actions that individuals take for themselves, on behalf of and with others in order to develop, protect, maintain and improve their health, well-being or wellness”. The upsurge in interest in self-care could be attributed to the increase in mental health concerns. The UK National Health Service (NHS) introduced a ‘Self Care Week’ in 2011 and this has been running each year since. Its goal is to encourage everyone to have ‘a healthier, happier life’ and to have self-care embedded into everyday life (NHS, 2017).

Linked to this is the practice of mindfulness as a method of self-care. This has steadily grown in popularity in recent decades in Western cultures; I sense, however, that there is a general misconception about mindfulness and about meditation in general in that it is believed that they involve emptying the mind of thoughts and emotions. However, mindfulness is a therapeutic technique that comprises elements of focusing on awareness of the present moment and the non-judgmental acceptance of one’s emotions and thoughts (Teper, Segal and Inzlicht, 2013, p.1; NHS, 2017). Benefits from practising mindfulness including helping people “manage their mental health or simply gain more enjoyment from life” (Mind, 2016). Mindfulness is also gaining acceptance in the UK and is being promoted widely in schools, for example, at the moment. Mindfulness in Schools Project (MiSP) is a charity whose aim is to inform, create, train and support the teaching of secular mindfulness to young people and those who care for them with the aim of helping them cope with difficulty, to thrive, and to improve their well-being and attention. It would be interesting to see how this will have an impact on their general well-being when in adulthood.

However, how does this relate to self-care in the context of missionary service?

Self-care sits within the wider member care model. The biblical basis for self-care includes, for example, loving ourselves (Matt 19:19; Mark 12:31; Luke 10:27; Galatians 5:14), the need to spend time with God and enjoying communion with Him (Luke 6:12; Luke 21:37), the need for rest (Genesis 2:2; Matt 11:28-30) and the need for accountability (Matthew 20:1-16; 1 Corinthians 3:5-9) (Bosch, 2014, p.200).

Missionary self-care refers to the manner in which mission workers are able to care for themselves proactively and wisely by having a balanced lifestyle throughout the ups and downs of their missionary life (Bruner, 2015; Bosch, 2014, p.199; Camp, C., Bustrum, J., Brokaw, D., and Adams, C., 2014, p.364; O’Donnell, 2002, p.17). It needs to be both proactive and preventative in nature so that mission workers can finish well and, when possible, take care of others in a healthy way (Bosch, 2014, pp.199-205). Ohanian (2015) describes it well as follows:

Self-care is neither selfish nor egotistical, but a wise, mature, preventative and self-respecting practice for anyone who desires to remain in their role of care and service. Self-care ensures that one will thrive and flourish as opposed to merely survive and cope. Self-care is the unseen root system, deep, nourished, expanding, of a strong, resilient, blossoming tree.

Caring for oneself as well as receiving care from those around us (mutual care) can be seen as the “backbone” of member care (O’Donnell, 2002, p.17). There is a reason why self-care and mutual care are linked closely together as we need a supportive community. “True self-care calls for a willingness to be vulnerable, to form meaningful and supportive connections, and to experiment with the balance between our personal needs and the needs of the community or collective” (Elliot, 2013). Ultimately, however, “you are responsible for you…. Not your spouse, roommate, prayer partner, mission leader, friends or anyone else… so be willing to accept the responsibility for getting your own needs met” (Graybill, 2001, p.13). Gardner reinforces this view, stating that no-one can meet all the needs of anyone else – ‘If it is to be, it is up to me’” (Gardner, 2015, p.177).

With this is mind, it is important to understand why self-care is not always a priority for mission workers. Hartz (2017a, pp.4-8) provides two possible reasons for this. Firstly, as mission workers carry many responsibilities and provide care to other people, they can let their own care fall by the wayside. It is essential for each worker to carve out their own habits and practices for self-care without turning it into another to-do list. “Making time every day for something that nourishes our body and soul is the equivalent of brushing your teeth every day” (Alessandra Pigni as quoted in Hartz, 2017a, p.46).

Secondly, it may be seen as a case of self-care versus self-sacrifice. Pressure from supporters (in particular, financial supporters) could mean that mission workers see themselves as having to suffer for the gospel and therefore, self-care is seen as being selfish. This can result in barriers to implementing self-care being put place at times when self-care is most necessary (Bruner, 2015). These barriers could include prioritising their ministry over their own self-care, not being willing to spend money on themselves, not taking holidays or believing that only weak unspiritual people need help (Bruner, 2015).

In contrast to this, if mission workers provide good self-care for themselves, there are many benefits for them and for others. These benefits might include managing stress levels, being effective in ministry, being productive and joyful in ministry, sustaining one’s own physical and spiritual health, avoiding burnout and maintaining healthier relationships (Bosch, 2014, pp.209-210). It could also prevent a disproportionate need for counselling and having people in mission who have been wounded (Bosch, 2014, p.205).

Self-care incorporates dimensions of life such as spiritual care, emotional/ mental health, physical health, social and family health (Whittaker, no date). Ignoring any of these dimensions would have consequences in our relationship with God, with others and with ourselves (Scazzero, 2006, p.18). The dimensions of spiritual, physical care and emotional care will now be reviewed.

With Master care at the core of member care (O’Donnell, 2002, p.16), having a healthy and vibrant spiritual life is fundamental to mission workers’ general welfare and effectiveness in their ministry. Gardner (2015, p.25) suggests that “no amount of member care will ever replace the need for God’s care in a worker’s life”. Master care involves God’s care for his people and our relationship with him (as evidenced through, for example, prayer, understanding God’s word, and maintaining spiritual disciplines). Our relationship with God should be protected, encouraged and enabled to grow and strengthen.

It is significant that even in the secular environment it can be seen, for example, in Hackney and Sanders’ 2003 meta-analysis of religiosity and mental health, that there was an improvement in the mental health of patients if they maintained an element of personal devotion (as cited in Duncan 2017, p.117). “The interesting conclusion to emerge… is that it is the world… that is telling us that we can improve our overall well-being if we follow religious practices, such as meditation, prayer, praise, and worship” (Duncan, 2017, p.117). The practice of these spiritual disciplines, among others, can help develop spiritual maturity and resilience.

Mission workers need to identify areas in their own lives where there needs to be spiritual growth. This can be done through carrying out a spiritual health check on a regular basis. Assessing our spiritual health means we can identify areas where there needs to be spiritual growth. We have a mandate to continually check our hearts and lives. Psalm 139: 23-24 (NIV) says

Search me, God, and know my heart;

test me and know my anxious thought.

See if there is any offensive way in me,

and lead me in the way everlasting.

A spiritual health check means digging deeper into our lives. Spiritual health checks or spiritual growth assessments are available online, which can provide an insight into areas of our spiritual lives which need added input, such as the Lifeway assessments found at http://www.lifeway.com/lwc/files/lwcF_PDF_DSC_Spiritual_Growth_Assessment.pdf

We should assess our spiritual life just as we would our physical health.

For single mission workers there is often no boundary between work and home. There can be expectations from others, for example, to work longer hours (as single workers don’t have family responsibilities), to babysit, or to be more available at weekends. This is above the normal daily tasks of handling their own finances, housework, and so on that go alongside ministry needs. It is easy to become over-busy, and as a result, become exhausted (Hawker & Herbert, 2013, p.260). This physical exhaustion could also affect other areas of life including neglecting their spiritual life.

Key components of physical resilience – our body’s ability to adapt to challenge and recover quickly – can suggest that people who are physically tough are able to withstand prolonged stress better than those who aren’t (Duncan, 2017, p.42). Duncan (2017, pp.46-56) continues that the following areas of physical care are important: exercise (being physically strong enables us to deal with challenges that we face); diet and nutrition; and sleep as it is important to support our body’s natural rhythms.

The need for physical rest, that is the ability to stop work or activity to relax or sleep, is extremely valuable. Jesus showed the importance of rest when he told the disciples to rest in Mark 6 verse 31:

Then, because so many people were coming and going that they did not even have a chance to eat, he said to them, “Come with me by yourselves to a quiet place and get some rest” (NIV).

Tim Keller expressed the view that “Rest, ironically, is an activity that must be prepared for and then pursued” (as quoted in Duncan, 2017, p.74).

In the organisation internationally, all members are encouraged to have a health review every other year, which covers both physical care and emotional/ psychological care.

2.2.3 Emotional/ Mental Health Care

According to Mind, the UK mental health charity, one in four people will experience a mental health problem each year. The Mental Health Foundation defines mental health as emotional health or well-being and states that it is just as important as physical health.

In order to reduce the risk of experiencing mental health problems, mission workers need to have the ability to recognise and reflect on their own reactions and feelings, to listen to their own intuitions and to look after themselves psychologically when needed in order to make the most of their lives and cope with the stresses of life (Gilbert, 2006, pp.2-3; Mental Health Foundation, 2018). Self-awareness and being accountable to others are key components to this. Self-awareness includes having an understanding of your strengths and weaknesses, understanding how to build intimacy in your context and having accountability relationships set up. As Hawker and Herbert state “we all need intimacy… single people are advised to prioritise time with their friends, forming deep, rich relationships” (2013, p.252). A lack of trust, fear of being hurt or the transient nature of mission work that can significant a lack of consistent relationships provides an understanding of why single workers do not always make this a priority (Carr, 2011, pp.10-11).

For a healthy balanced life, individuals should assess all of the dimensions of self-care and reflect and act on areas of growth. This applies to married mission workers just as much as single workers. However, I will now focus on single workers in the context of mission.

2.3 Single Workers in the Mission Context

This is not a paper on singleness as such. Nevertheless, it is important to understand the biblical basis for singleness. From the outset, it must be emphasised that singleness is not a second-class state or a less than ideal state for a mission worker (Moreau, Corwin & McGee, 2015, p.188). John Stott, a well-known Christian teacher and author, wrote “both the married and the single states are ‘good’; neither is in itself better or worse than the other. So, whether we are single or married, we need to receive our situation from God as his own special grace-gift to us” (as quoted in Carr, 2011, p.6).

One of the underlying issues for many single workers in receiving this grace-gift is whether or not they are content in their single status. In research carried out in recent years, it found that, on the whole, single mission workers agreed with the statement ‘I am content in being single’ (Hawker & Herbert, 2013, p.269). Some mission workers believe that God has called them to remain single and feel fulfilled in that calling. For others, this is an area of growth in which they need to develop. Therefore, some of the following challenges and opportunities/ benefits of being single will be seen through the lens of where they currently are in their level of contentment.

The majority of literature available on singles in mission relate to single women who represent the majority of single mission workers. Single male mission workers are “a rare breed” (Hawker & Herbert, 2013, p.36) and many choose to go either short-term rather than long-term. The ratio of single women to single male mission workers could be as great as ten to one (Hawker & Herbert, 2013, p.36). Although the single men can face different challenges on the field, this dissertation does not distinguish between the challenges and opportunities raised by the male respondents, primarily to protect their identity.

Some of the following challenges and opportunities are applicable to single Christians here in the UK and are not specifically relevant to single mission workers. However, they can take on a different intensity for single mission workers as they have an impact on their life and ministry on the field (Terry, 2015, p.429). Herbert & Rotter (2016) provide a good analogy of the difference between singles and marrieds using the example of building a house out of Lego© bricks. They describe the difference as everyone being given the same bricks, however, single people can have the freedom to build their houses differently. Whether through choice or not, single people are individuals and can “respond differently, struggle in different ways, and express ourselves differently” (Clark, 2013, p.225). Phoenix (2016) concurs with this view, stating that “singleness is neither a curse nor a handicap. It is merely a different sort of life, and it can be just as ripe with purpose and joy as one lived in tandem”. In terms of being single in the mission context, it has been said that “the hardest part of singleness … is being single!” (Graybill, 2001, p.6).

2.4 Opportunities for single mission workers in the area of self-care

According to the available literature, the main opportunities for greater self-care for the single mission worker are having time, flexibility and being able to develop stronger bonds with national friends and workers for mutual care and friendship.

The most mentioned opportunity by the respondents in this study was that of flexibility and time. This is reinforced by the available literature for singles in mission. It is claimed that single mission workers have more time to devote to ministry, and more control over their time as their schedules are more flexible. They have more leisure time and have more time to develop their relationship with the Lord and others in ministry (Gardner, 2015, p.168; Moreau, Corwin & McGee, 2015, p.188; Bosch, 2014, p.146; Hawley, 2014).

It is argued that the best part of being single is the freedom to use their time as they choose, to not have to worry about anyone else, and be able to make their own decisions (Hawker & Herbert, 2013, p.269; Carr, 2011, p.8). The positive aspect of making their own decisions is that ultimately those decisions often only really affect themselves (Clark, 2013, p.219). This is in contrast to the challenge regarding having to make decisions on their own which will be reviewed later.

Moreau, Corwin & McGee (2015, p.188) contend that single mission workers also tend to be more flexible in terms of where they serve/ location. While it is true that there can be flexibility in location, it is my experience that many mission workers, whether married or single, come with fairly definite ideas of where they wish to serve and what ministries they want to be involved in. The reasons for this include issues of isolation, team size and colleagues.

2.4.2 Stronger bonds with friends, both national and team

Singleness on the field can be seen as an advantage in terms of having time, freedom and flexibility in developing stronger bonds with friends and developing family-like relationships (Gardner, 2015, p.168; Hawker & Herbert, 2013, p.270; Smith, 2004, p.193), while being spared the challenges that families face in setting up a way of life for their family, figuring out how to socialise and having the time needed to do that (Smith, 2004, pp.194-195). Ritchey provides the view that the single workers can be creative and effective in forming friendships, establishing trust, contributing positively to the community and sharing their faith in the midst of it (2013, p.232).

Graybill (2001, p.18) advises single workers to take the initiative to make friends with roommates or other singles, missionary wives, couples and families. This includes developing appropriate friendships with the opposite sex. She also recommends limiting how much time single workers spend alone, acknowledging their own ‘nesting’ needs and finding healthy ways of meeting their need for touch.

The status of being single is one that can be seen as an opportunity as well as a challenge for many single workers. Much of the literature on singleness in mission focuses on singleness being seen as a flaw or full of challenges (Gardner, 2015, p.172) or describes single mission workers as being a “social peculiarity” (Foyle, 2001, p.142) as opposed to something to be “celebrated as independence” (Constantine, no date). Although the research highlights various challenges, these challenges need to be kept in balance with the positives/ benefits of being single on the field. There is often a flipside to each of the opportunities and challenges. Bosch (2014, p.146) states “It is worth mentioning that the privilege of being single could also become a real challenge or a stressor. Every privilege may therefore be debatable”. It is to these challenges that we now turn our focus.

2.5 Challenges faced by single mission workers in the area of self-care

Graybill (2002, pp.147-151) provides some examples of the challenges faced on the mission field, focusing on single female mission workers but which are relevant for both sexes. These include loneliness, barriers to developing close friendships, finding validation and affirmation, searching for good solutions to their living arrangements, and dealing with a missionary subculture that gives preference to married people.

The challenges which are highlighted here relate to the challenges raised by the respondents either in the questionnaires or the interviews and so will not cover the whole range of challenges faced. This is not to say that these more important as the challenges of, for example, appropriate intimacy, touch and sexual behaviour in relation to self-care which are just as important. “It has been said that to be emotionally healthy a person needs eight to twelve hugs a day” (Graybill, 2001, p.10). Touch is one of the five senses and the premise of Chapman’s book (2009) is that physical touch is one of the fundamental love languages. However, some single adults may not respond as positively to physical touch and may not find it as affirming as others, especially if they did not grow up in a ‘touching family’ (Chapman, 2009, pp.102-103).

Views held 20-30 years ago with regards to single workers and accommodation needs could be summarised by this quote by Lum (1984, p.108 as quoted in Moreau, Corwin & McGee, 2015, p.189):

Singles can get along with temporary furnishings that are impractical for a family. They can live out of a suitcase but a family cannot. A bicycle often suffices for a single person… So not only do singles spend less money on personal and household furnishing; they spend less time maintaining them. In short, singles can keep their lives uncluttered materially and emotionally. This should make it easier to keep their lives emotionally uncluttered too.

Thankfully, understanding of the needs of single workers has moved on since then. Nonetheless, single mission workers can still be made to feel like second-class citizens with regards to accommodation and can receive less consideration than couples and families. Singles often do not get to choose their housemates and living alone is often not possible due to accommodation costs. Having to share housing can cause stress levels to rise if housemates have different habits and come from different cultures (Foyle, 2001, p.144).

Securing appropriate accommodation on home assignment can also be an issue. There is often a need for single workers to stay at parents’ home, especially on a short Home Assignment. This can bring pressures if family members do not understand the need for space and separateness (Wiarda, 2002, p.54). “Singles deserve to have a household and to choose with whom they want to live” (Roembke, 2000, p.144).

However, on the flipside, living alone can lead to singles becoming reclusive and set in their ways. “We need to avoid becoming more peculiar than our job makes us anyway!” (Foyle 2001, p.146). This is linked to the challenge of relationships with others.

2.5.2 Relationships with others/ Accountability

Accountability is having someone trustworthy to whom we can appropriately disclose struggles, through whom we can be encouraged, supported and challenged. “Accountability partners help us face into the truth of who we are in Christ” (Ahlberg Calhoun, 2015, p.143). It is possible, if there is no consistent accountability, that single workers can tend to become selfish, self-centred, set in their ways, inflexible, impatient and intolerable, often with low self-esteem (Bosch, 2014, p.151; Aune, 2002, p.92). It is, therefore, important to ensure accountability is in place and that relational needs are met. It is possible that ministry and other time-fillers could take the place of relational intimacy (Moreau, Corwin and McGee, 2015, p.189).

2.5.3 Loneliness and no significant other to share daily events with

A vast percentage of the relevant literature highlights the issue of loneliness as being one of the biggest struggles for single people, whether in mission or not (Koteskey, 2017, p.31; Bosch, 2014, p.148; Roembke, 2000, p.187). Loneliness can be defined as “that hollow devastating feeling that one has to carry their weight of one’s life alone, without being in a position to really share it with anyone special, with someone who really cares” (Roembke, 2000, p.188).

This loneliness can come from not having a “built-in companion or an already established support system” (Kraft, 2013, p.126) and can be a significant disadvantage when it comes to sharing the ups and downs of life and in decision making (Aune, 2002, p.92). In addition to the emotional support that is needed, single workers also have to deal with their ‘aloneness’ (Hoke & Taylor, 2009, p.175), that is, dealing with the responsibilities of everyday life, such as making big decisions on their own (planning towards retirement, buying a home, changing ministries), dealing with their finances, getting repairs done, shopping, cleaning and running a car (Phoenix, 2016; Phoenix, 2014; Clarke, 2013, p.219). In some ways, this is a bigger challenge than loneliness itself. “God is sufficient for our needs, but he usually meets them through people. To be blunt: even if the Lord is meeting my emotional needs, he doesn’t change light-bulbs!” (Clark, 2013, p.220).

In contrast to this view, Ohanian (2009, p.1) counters the view that loneliness is a constant challenge with the idea that loneliness is a feeling that comes in waves and seasons and can affect both married and single workers. From my own experience, I would agree with this view. Loneliness was not something experienced every day on the field and there were ways of limiting those periods of loneliness by planning ahead for trips, holidays and days off. It is interesting that none of the respondents interviewed highlighted loneliness as being a major issue for them, although this could be subsumed into the challenges of finding people to do things with or having to deal with everything on their own.

“The single missionary must learn to meet [her] emotional needs in the absence of a spouse… Single workers need to be willing to be intentional and assertive about getting their emotional needs met in order to thrive on the field” (Graybill, 2001, p.7). Single workers can achieve this through having appropriate support structures in place. Developing a network of friends is also important. They often get closer to national friends out of a sheer personal need in order to settle into a new culture (Roembke, 2000, p.141).

However, not being able to share deeply in your heart language can lead to a lack of deep personal relationships on the field. Single mission workers face special stresses as, when they go to the field, they leave their families behind (Andrews, 2004, p.257). As a result of this, some single mission workers have relied on sustaining relationships back in their home country. This hasn’t been helped by modern technology, such as email, instant messaging or Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) such as Skype, which has resulted in some workers becoming so interested in maintaining their support networks at home to such an extent that that they fail to build sufficient new support networks in their local context (Koteskey, 2017, p.34).

2.5.5 The challenge of holidays

Holidays alone can seem a lonely or boring prospect and are not always satisfying (Koteskey, 2017, p.33; Gardner, 2015, p.167; Hawker & Herbert, 2013, p.261). They can be expensive for singles as many hotels add on supplements for rooms with single occupancy. Finding others to travel with is not always easy as their availability may be different. The locations to which a single worker can go for a holiday can also be limited due to safety concerns. OMF International has several holiday homes around Asia, however, for many single workers spending time with other mission workers is not a break from ministry and they can often find themselves being asked to babysit for families who are also staying there.

2.5.6 Understanding from team leaders

A challenge for those caring for single workers, either by the organisation as a whole or by teammates/ colleagues is that “single workers have different needs, for companionship, logistical help, practical daily living and attention should be given to ways of helping without demeaning” (Gardner, 2015, p.177). However, single mission workers often feel neglected in terms of on-field care by their agencies (Andrews, 2004, p.257) so there is a balance needed between actually giving care and helping without demeaning.

Team members might also have expectations about the amount of ministry single workers can accomplish as they have more time to give (Hawley, 2014). “In missions, single people are frequently expected to work extra hours because they don’t have the same responsibilities as families” (Clark, 2013, p.219).

“Team leaders or couples are not always aware or in tune with the specific needs of singles and vice versa” (Tissingh, 2002, p.109) and single workers may have more expectations of their team members in acting as a substitute family than their team members recognise and relate to (Roembke, 2000, p.141). How those needs are made known and met will depend on the make-up of the team and the willingness of the single worker to be vulnerable and share their needs.

Boundaries are limits on what is reasonable and are essential for both physical and emotional health. According to Cloud and Townsend (2017, pp.31-32), boundaries define us and we need to take responsibility for our own needs and to be responsible to others. These boundaries can relate to our feelings, attitudes and beliefs, behaviours, choices, limits and values (Cloud and Townsend, 2017, pp.41-50). Difficulties may arise when it becomes impossible to say no to something or someone if they are put under pressure by others, or when their boundaries are not respected (Cloud and Townsend, 2017, pp.55-56).

Clarke (2013, p.223) notes that the accepted teaching for mission workers in terms of priorities should be God first, family second, ministry next and ourselves last. However, “for a single mission worker the order is reduced to: God, ministry, self. Often this leads to overwork and burnout, as well as a failure adequately to meet one’s own needs such as rest, exercise, friendships, healthy food and fun” (Clarke, 2013, p.223). It is essential that boundaries are put in place in order to avoid the potential of overwork and burnout.

While setting boundaries are essential for good health, it is important to recognise as well when they are being used to avoid responsibility or suffering. Having appropriate accountability will be beneficial in tackling this issue.

Although the above challenges and opportunities are under the control of the individual mission worker, the organisation should have a role to play in encouraging its members to carry out self-care. The following section reviews the organisational response to this.

Organisations have a responsibility to care for their workers. However, they often can have many constraints which may prevent them from providing an appropriate level of support to those workers. This could be due to a lack of resources or capacity, a culture of putting the needs of the work above the needs of the workers, a lack of understanding as to who is responsible for providing support within the organisation as well as the operational reality of getting the work done (Gilbert, 2006, p.3). Unfortunately, there could also be “an organisational culture which implicitly encourages the ‘superman’ or ‘hero’ image” (Gilbert, 2006, p.3). When considering its single workers, Herbert (2012) states that “by making assumptions about the flexibility of singles, they [organisations] can unintentionally contribute to stress and burnout. Sometimes they can take advantage of singles to such an extent that, in a different context, it could be seen as discrimination or even abuse”.

There are a number of questions which an organisation needs to ask itself when thinking through the support it needs to give its members. These could include asking what support structure is in place for its single mission workers, what policies and practices are in place and is the organisation doing anything that makes life and ministry harder for its single workers (Carr, 2011, p.13). In light of the declining number of single mission workers, as seen in a study carried out by Lois McKinney Douglas (as cited in Carr, 2011, p.13), organisations need to ensure that they do not consider their single workers as second-class members and make it harder for them to remain on the field long-term (Carr, 2011, p.13).

Organisational leaders can be encouraged to take a fresh look at their policies and practices regarding housing, finances, retirement, home assignment expectations, leadership structure, ministry placements, and decision making in order to ensure that they are being fair to and inclusive of their single workers (Carr, 2011, p.13). Herbert (2017) raises questions regarding single men joining mission agencies. These include organisations needing to consider having placements that will seem attractive to single men, how organisations are mobilising men, having an understanding of their needs and how organisations are mentoring single men in the field so that they can be fulfilled in their singleness and ministry.

The values embedded in the organisation’s culture will have an impact on how mission workers will care for themselves and others. “By emphasizing the foundational need for self-care as a prerequisite of being able to care for and minister to others, agencies can promote a culture that recognizes human limitations and needs” (Camp, C., Bustrum, J., Brokaw, D., and Adams, C., 2014, p.366).

After gaining this understanding from available member care literature, it was necessary then to consider and choose appropriate research methods in order to gather relevant information from the participants. The research methods will be presented in the following chapter.

The purpose of this chapter is to explain the research process. The rationale behind selecting questionnaires and semi-structured interviews as the research methods employed will be presented. Following this, the process of data gathering and the subsequent analysis will be examined. Limitations of the data collection will also be highlighted.

3.1 Rationale for use of chosen methods

As the purpose of the research was to analyse emerging themes rather than testing a hypothesis, it was essential to use appropriate methods to extract the relevant information from the mission workers.

Qualitative research has been used as it is conducted, for example, when there is a question to be answered, or a problem to be explored (Creswell, 2007, p.39), when individuals are “empowered to share their stories” or because there is a need or a desire to understand how respondents in certain settings or contexts react to a problem or issue (Cresswell, 2007, p.40). Advantages of qualitative research include being able to have the flexibility to follow unexpected issues and ideas that can arise during the research process and being able to respond sensitively to contextual factors (Ospina, 2004, p.2).

Since we experience events through our own point of view, each of us experiences reality in a different way. So, although there may be commonalities between the single mission workers and their age, location or personality, their perceived needs and outlook may be different. Due to the scarcity of literature on this matter of self-care, it was important to obtain first-hand comments from this selected group of participants and therefore a phenomenological approach has been taken as it generally deals with perceptions, meanings, attitudes/ beliefs and feelings and emotions (Denscombe, 2010, pp.93-94). The constructivist approach has been taken due to the fact that the ontological situation is that ‘reality is subjective and changing’ (Swinton and Mowat, 2006, p.70) and there is a need to focus on understanding (Swinton and Mowat, 2006, p.71).

In order to obtain this first-hand input, the use of more than one method provided a fuller, more complete picture (Denscombe, 2010, p.141). The use of questionnaires and semi-structured interviews were used as the focus of the research. They complement each other and have provided the depth of material needed as they presented details of the real-life experiences of single mission workers on the field and in their sending country.

The use of a questionnaire enabled me to contact all of our UK single members as they were able to complete it online. Our members are spread geographically throughout East Asia and the UK and I required a means of reaching as many members as possible. As we have a secure email set-up within the organisation, it meant that security, although it was a consideration, was not a major concern. As all of our UK members know who I am, it meant that limited introduction was needed for them. I anticipated that the already existing work relationship with them would encourage them to complete the questionnaire.

Before contacting all members, a sample questionnaire was given to two members in order to test the questions and to see if the questions covered the pertinent topics. Feedback was given, relating to the wording of the questions and ease of being able to answer them. As a result, various questions were added or refined.

The advantages surrounding the use of questionnaires include the ability to gather basic information efficiently and economically from those taking part in the research and can be used in various situations. The questions were “identical for each participant, allowing for consistency and precision in terms of the wording of the questions and makes the processing of the answers easier” (Denscombe, 2010, p.156). One further advantage is that they are commonplace as they are used frequently by many organisations. Bradburn and Sudman (1988 as quoted in Sarantakos, 2005, p.239) have stated “surveys are not only a common research tool, but also part of a person’s life experience”.

Once the questionnaire was ready, an email was sent to all participants with a link to SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com), an online software tool used for creating and administering questionnaires. SurveyMonkey was simple to use and set up, with a variety of styles of questions being available. It provided a means of giving introductory information to the respondents and was easy to self-administer and so this resulted in limited contact with the respondents at this stage.

The questionnaires contained 30 questions, ranging from introductory factual questions about their age, ministry setting, length of service, and personality to questions designed to gather their opinions on their physical care (days off, holidays, and living arrangements), spiritual care, and emotional/ intellectual care (how they spend their time, the need for physical touch, isolation and on-going learning and development). Questions on challenges in caring for themselves, accountability partners, location impacting their self-care and how the organisation could better assist them completed the questionnaire. A copy of the questionnaire is attached as Appendix A.

Although the questionnaires provided invaluable data, I made some errors in the set-up of the SurveyMonkey questionnaire. The set-up allowed respondents to skip questions that resulted in obtaining incomplete data. Some respondents started a questionnaire but then didn’t complete it and then started it a second time. This resulted in duplication of some of the data which had to be excluded. Out of a total of 42 questionnaires filled in, there were only 36 complete questionnaires that could be used. All of the incomplete questionnaires were excluded, as it was unclear whether some were a first attempt by some of the respondents and so results had the potential to be unhelpfully duplicated.

In order to provide a flow of information, questionnaires can be used in conjunction with interviews. In this case semi-structured interviews have been selected as an appropriate method that will build on the information gathered in the questionnaires.

3.3 Semi-Structured Interviews

An interview is “the most prominent data collection tool in qualitative research. It is a very good way of accessing people’s perceptions, meanings, definitions of situations and constructions of reality. It is also one of the most powerful ways we have of understanding others” (Punch, 2013, p.144).

Semi-structured interviews were chosen as a means of developing the themes and questions that came out of the questionnaires and clarifying some of the data provided. They “manage to address the need for comparable responses – that is, the same questions being asked of each interviewee – and the need for the interview to be developed by the conversation between interviewer and interviewee” (Wisker, 2008, pp.194-195). This allowed me expand further with the objective of understanding the respondent’s point of view and to obtain their views and opinions gaining an understanding of their meaningful but nuanced responses (Patton, 1990 as cited in Biggam, 2011, p.146; Quirkos, 2016).

Preparation for the interviews was vital. The principles of striving to avoid asking leading questions or imposing meanings on the questions/ answers and creating a relaxed comfortable conversation was key to build trust and rapport (Denscombe, 2010, p.185; Wisker, 2008, p.200) when drawing up the list of potential questions and follow-on questions. Before carrying out any of the interviews, a pilot interview was carried out to ensure that the questions weren’t too vague or too probing. They needed to be clear and follow on from the previous questions, in order to obtain the information that I needed and to ensure that they were not misleading (Wisker, 2008, p.200-201). A single former mission worker from another organisation provided input to the questions when piloting the interview. She was able to provide input in relation to ensuring that the questions were clear and understandable to someone hearing them for the first time. Following her input, several questions were re-worded. A copy of the interview questions is attached in Appendix B.

Following on the initial response from the questionnaires, I chose eight OMF International (UK) members to be interviewed either in person while on home assignment or via Skype/ VSee. These eight members were a representative sample involving a cross-section of the membership. A representative sample “matches the population in terms of its mix of ingredients and relies on using a selection procedure that includes all relevant factors/ variables/ events and matches the proportions in the overall population” (Denscombe, 2010, p.24). These members were a mix of male and female members, those working in Open Access Ministry Settings (OAMS) and Creative Access Ministry Settings (CAMS) and a mix of those who have served long-term with the organisation and newer joiners in order to bring a breadth of experience and opinions. With only seven single male mission workers sent from the UK, it was anticipated that the majority of those interviewed would be female (only two men were interviewed). Participants were provided with a list of potential questions, along with relevant information regarding consent and recording of data, in advance of the interview to allow time for consideration, which was appreciated by them.

One strength of such interviews included the fact that rapport between myself as the interviewer and the interviewee could be built up quickly and complex questions and issues could be discussed or clarified (Punch, 2013, p.144). However, I tried to avoid over-familiarity as all interviewees were known personally to me. My role as the researcher as well as being the person responsible for member care in OMF International (UK) meant that there was the possibility of the participants feeling unable to share fully about how they felt. Only one respondent mentioned this in their interview, however, they felt they were able to be honest and share their views openly.

The interviews allowed opinions, feelings and perceptions to be probed (Richardson et al, 1965, Smith 1975 cited in Barriball and White, 1994, p.329) as well as being able to evaluate the reliability and viability of the interviewee’s responses (Barriball and White, 1994, p.329).

Authors such as Patton (2002) and Creswell, (2009) corroborate this view identifying that “Qualitative interviews provide in-depth, contextualised open-ended responses from respondents about their views, opinions, feelings, knowledge and experiences. They can discover how certain events have affected people’s thoughts and feelings’’ (as quoted in Mikėnė, S., Gaižauskaitė, I., & Valavičienė, N., 2013, p.51).

These interviews were easy to record due to the availability of various recording devices available currently. The interviews were recorded using ‘QuickTime’ programme, which worked well when recording both from Skype or face-to-face. These were then transcribed. Denscombe (2010, p.275) states that “transcriptions help with detailed searches and comparisons of the data” and it also enabled me to get a deeper understanding of the material and I was able to identify emerging themes throughout the process. It brought “the talk to life again” (Denscombe, 2010, p.275). However, it was a time-consuming process. “The process of transcribing needs to be recognized as a substantial part of the method of interviewing and not to be treated as some trivial chore to be tagged on once the real business of interviewing has been completed” (Denscombe, 2010, p.275). Once the interviews were typed up, they were sent to the interviewees for validation.

As most of the interviews were conducted over Skype – only two out of the eight were face-to-face – the quality of the recordings was a concern, however, the result was that the recordings were of good quality. One of the main problems that arose during the interviews was the fact that the respondents often did not speak in complete sentences or changed what they were going to say part-way through a sentence and so it was necessary to clean up the transcripts to ensure that they were readable. However, this may mean that it “loses some authenticity” (Denscombe, 2010, p.276).

The next step is to code the data as “the interpretation of data is at the core of qualitative research” (Flick, 2009, p.306).

“Coding is … a method than enables you to organize and group similarly coded data into categories or ‘families’ because they share some characteristic – the beginning of a pattern” (Saldana, 2015, p.8). The codes are tags (words or short phrases) that are attached to the gathered data from the interview transcripts and questionnaires (Denscombe, 2010, p.284).

From these codes, it was possible to reduce the data to determine relevant themes (Saldana, 2015, p.9). “A set of themes is a good thing to emerge from analysis, but at the beginning cycles there are other rich discoveries to be made with specific coding methods that explore such phenomena as participant process, emotions and values” (Saldana, 2015, p.13). These key themes were focused around the challenges and opportunities for single workers and how they fit within the areas of spiritual care, emotional care and friendships. This required me to review, select, interpret and summarise the information without distorting it (Walliman, 2011, p.133). The themes are significant if they capture something important in relation to the overall research question (Braun and Clark, 2006, p.11). Some of the codes were mentioned in the majority of the transcripts, whereas one or two were significant only in a couple of them.

Open coding is “the first step at expressing data and phenomena in the form of concepts” which can be applied in various degrees of detail (Flick, 2009, p.307-309). “The main goal is to break down and understand a text and to attach and develop categories and put them into an order in the course of time” (Flick, 2009, p.309).

Reliability refers to the ability to produce consistent results from the findings. Validity is concerned with the accuracy and precisions of the data, i.e., it “concerns the extent to which it is actually capable of providing information, which it claims to provide” (Akbayrak, 2000, p.8).

Lincoln and Guba (1985) “make the point that it is not possible for qualitative researchers to prove in any absolute way that they have ‘got it right’” (as quoted in Denscombe, 2010, p.299). However, in order to show that the data is as dependable and credible as possible, the research process needs to be “open for audit” (Denscombe, 2010, p.300). This entails showing in as much detail as possible how the research led to the defined outcomes. Using both questionnaires and interviews together will increase the validity of the findings as it will be possible to dig deeper in interviews and to clarify answers given in the questionnaires. All respondents were willing to contribute to the questionnaires and interviews which increased the validity and reliability of the data gathered. Similar wording of questions in the interviews were used to reduce interview bias and asking interview participants to check the transcript of their interview also enabled me to check the accuracy and credibility of the data. Anonymity was provided to the respondents which increased the reliability of the data as they were freer to share their opinions.

Ethics in relation to social research “refers to the moral deliberation, choice and accountability on the part of the researchers throughout the research process” (Edwards & Mauthner, 2012, p.14).

As questionnaires and semi-structured interviews were used, it was necessary to obtain the consent of those responding to the questionnaire and taking part in the interviews. The completion of the online questionnaire was taken as a sign of consent for their information to be used in the research paper, as stated in the introduction to the questionnaire. Participants who were asked to be interviewed were required to give their consent in writing by completing a Participant Consent Form (Appendix C).

It was intended that the interviews would be recorded in order to provide an accurate objective record of the discussion as well allowing the researcher to concentrate on the interview at the time.

An explanation of how anonymity and privacy of the individuals was given, as well as providing an understanding of the research question. It was my responsibility as the researcher to ensure that the participants are not adversely affected by the research. As there is a feeling of fellowship and family among a lot of the OMF members, everyone knows everyone else and it was important to ensure that none of the participants could be identified through the comments used in this paper. Therefore, each interviewee has been given a pseudonym and the male respondents have not been identified in the Table 1: demographic profile of interview respondents.

It was made clear that participants could withdraw at any stage of the process. As the person responsible for member care within OMF International (UK), it was important to avoid imposing my own views or reactions on to the research and interviews.

In this chapter, I have explained the reasoning behind using the chosen research methodology. The results from this research, gathered through the questionnaires and interviews, will be presented and analysed in the following chapters.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Health and Social Care"

Health and Social Care is the term used to describe care given to vulnerable people and those with medical conditions or suffering from ill health. Health and Social Care can be provided within the community, hospitals, and other related settings such as health centres.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: