Trauma-Informed Care & Practice (TICP) for Mental Health Services in NSW

Info: 8580 words (34 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Project Summary

Experiences of trauma are highly prevalent in the general population and are endemic in the population of people using mental health services. Trauma has a relationship with the development of mental health conditions and adversely affects the response to treatments, services and personal recovery.

A case for change (Appendix 1) provides the evidence about the importance of TICP and the positive effects for consumers, staff, services and systems when TICP principles are applied into practice. TICP is an approach which recognises and acknowledges trauma and its prevalence, along with awareness and understanding to its subtleties, in all aspects of service delivery. Services where trauma informed care is not practiced risk traumatising and re-traumatising consumers and staff with increased likelihood of:

- the use of restrictive practices

- critical incidents that can incur physical and psychological injury

- increased cost from injury

- increased length of stay

- increased readmission rate

- negative experience of care for consumers

- decreased staff satisfaction and engagement in care

- custodial organisational cultures of care

Where evidence based strategies and approaches to TICP are implemented it increases the likelihood of effective treatment, decreases adverse events in care and improves safety for consumers and staff. Trauma-informed care is a crucial component of recovery-oriented practice and the delivery of person centred care.

A current priority within public mental health services, the mental health sector more broadly, policy makers and from consumers and carers is that services are trauma informed in all aspects of their organisation, management and service delivery to ensure a basic understanding of how trauma impacts the life of people accessing services.

The project will design, develop and evaluate evidence informed approaches to the implementation of Trauma-Informed Care & Practice inMental Health Services in NSW. It will provide evidence based guidance on the translation of TICP principles into practice in mental health settings The project will use a co-design approach to understand what will assist staff/ practitioners and services with the implementation of TICP. A feature of the project will be a website which will centralise current TICP service provision in NSW indlcuing best practice strategies and resources.

An implementation strategy will be developed and a pilot will occur in two acute mental health units ( yet to be identified). An Evaluation framework will be developed to measure the success of the project, including the outcomes and experiences of care for consumers accessing these services and the staff who are delivering care.

- Aims

The aim of the project is to improve outcomes and experience for people who access mental health services in NSW through the development and evaluation of evidence based strategies and approaches to the implementation of TICP for Mental Health services in NSW.

- Project Deliverables and Scope There are two major deliverables from this project with different scopes.

The first deliverable will be the development of a website that will provide information on the TICP project, specific TICP initiatives in NSW public mental health services, links to relevant existing resources and which will provide access to resources and implementation support that will be developed during the solution design.

Project Scope for Website

| In | Out | |

| People | People who access public MHS and CMOs and their families, carers and support people

All staff/practitioners in public mental health services and CMOs |

People who do not access -mental health services |

| Process | Broad Processes

Admission and discharge process to mental health services including ED Transfer of care across service settings Restrictive practices:

Environmental safety Cultural practices and gender sensitivity Policies & procedures Service Specific Processes Assessments Discharge Planning Safety Plans Clinical Reviews Treatment Access Referral MHRT processes |

|

| Organisation | MH Line

CMOs Public Mental Health Services ED |

Care provided outside mental health units/by non-mental health staff

Drug and Alcohol Services Non-mental Health ED presentations |

| Technology | Web based resources | EMR |

| Facility/Services | Yet to be determined | Paediatric mental health services

Non-mental health services General Practitioners Private care providers |

The second deliverable will be the implementation and evaluation of TICP strategies and resources with two standalone acute mental health units. The two units are yet to be determined.

- Project Phases and Schedule

The project commenced in late 2016 and is expected to take approximately 24 months dependent on resourcing. Identified in Phase1 are a number of deliverables that have been achieved. See Appendix 2 for more detail on time frames

Phase 1: Project Initiation Phase: develop a project concept and scope (Complete)

- Document project aim, objectives, scope and method

- Determine the case for change

- Establish sponsorship / generate support / interest / participation

- Establish governance framework

- Develop project timeline

- Undertake program logic

Phase 2: Development of Web page and communication plan (Dec 2017 – March 2018)

- Develop content and establish a web page for project

- Develop and implement a process to publish current TICP service provision and training in NSW

- Identify existing relevant resources

- Develop a communication and stakeholder engagement plan for the project

Phase 3: Solution Design (Jan – July 2018) (See Appendix 3)

- Undertake consumer and staff/participant focus groups (round one) and broader stakeholder consultation (round two) to inform solution design

- Develop a suite of strategies and tools for implementation

- Develop and test prioritised solutions with stakeholders

- Develop a conceptual framework for the delivery of TICP in NSW

- Development of self-assessment tool

- Development of evaluation framework to assess the efficacy of approach

Phase 4: Implementation and evaluation of TICP at pilot sites (July 2018- Mar 2019)

- Focus implementation on 2 pilot mental health units identified through expression of interest however this will be dependent on available resourcing and prioritisation

- The approach could include for example the ACI implementation framework or collaborative methodology.

- Development of Phase 3 – 4 budget

Phase 5: Evaluation of the TICP Strategies (January – March 2019)

- Evaluation of TICP implementation and opportunity to scale up processes

- Project Budget (Phase 1 & 2)

This budget relates to the estimated cost of the project till 30th June 2018. It is proposed that nine focus groups are held across a number of metropolitan, regional and rural areas that will then inform a broader survey to stakeholders. Human resource costs are in kind however it is proposed a consumer researcher* is contracted to: lead the consumer focus groups and colead the staff/practitioner focus groups, provide the thematic analysis and reporting.

Phase 3 budget to be developed in March 2018 as part of Implementation planning.

| Description of Expense | Expenditure |

| EWG expenses travel | $7,500 |

| EWG expenses : accommodation & incidentals | $3,300 |

| Focus group travel & accommodation | $10,000 |

| Consumer researcher | $6,500 |

| Incidentals eg venues, catering for focus groups | $2,000 |

| Resource Development e.g. professional writing, web development, resource production | $8,000 |

| Total Cost | $37,300 |

* Evidence shows when consumers are partners or leaders of mental health projects, more meaningful connections are made with participants, effective research tools are created, such as surveys, and they report personal and professional benefits of conducting research. NSW Mental Health Commission

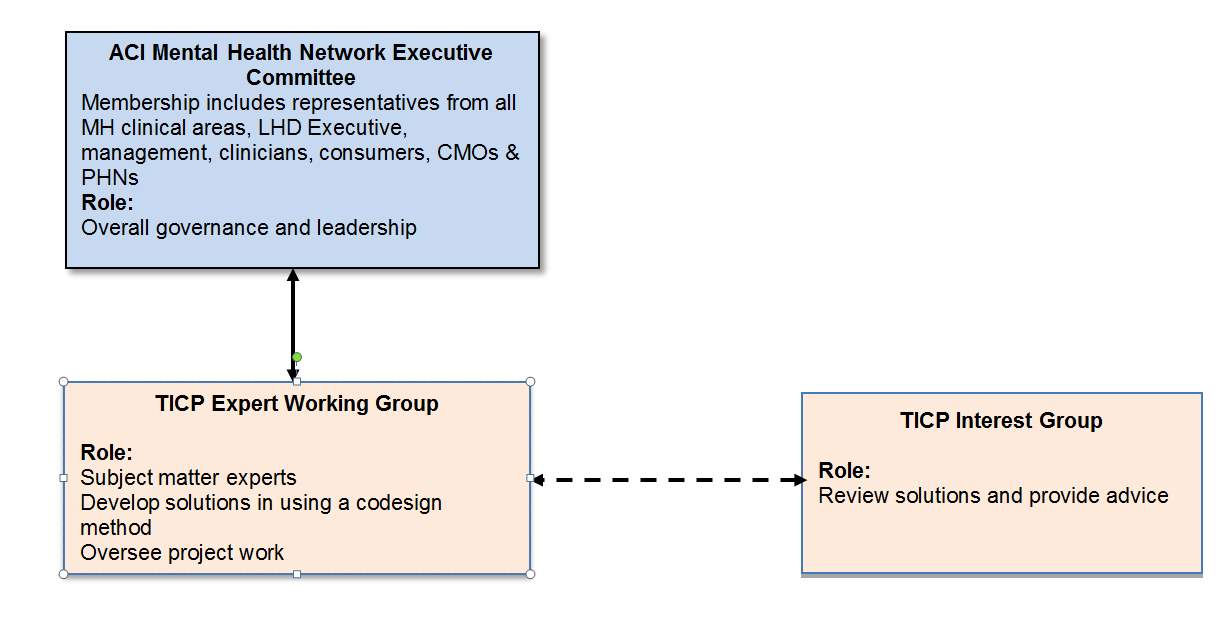

- Governance

ACI MH NEC provides overall governance with the EWG providing project leadership. Endorsement of the project will be by the MH NEC co-chairs with Approval required by the Director, Primary Care and Chronic Services. It is expected that the members of the MH NEC and the TICP Advisory Group (Reference Group) who will include LHD executive representatives, senior management, mental health service managers, CMO executive and consumer organisations will take the role of influencers for the project.

The ACI TICP EWG (ACI Network Manager, ACI Implementation Manager, ACI Mental Health Network Co-Chairs (2), expert clinicians, consumer researchers and people with lived experience of mental illness, make up the project team involved in the development of solutions, and plans for implementation and evaluation.

The TICP Reference Group will consist of stakeholders who have experience in mental health service delivery and provide a broader representation of key stakeholders across the state. The role will be to review and provide advice on project work as required.

Governance Structure

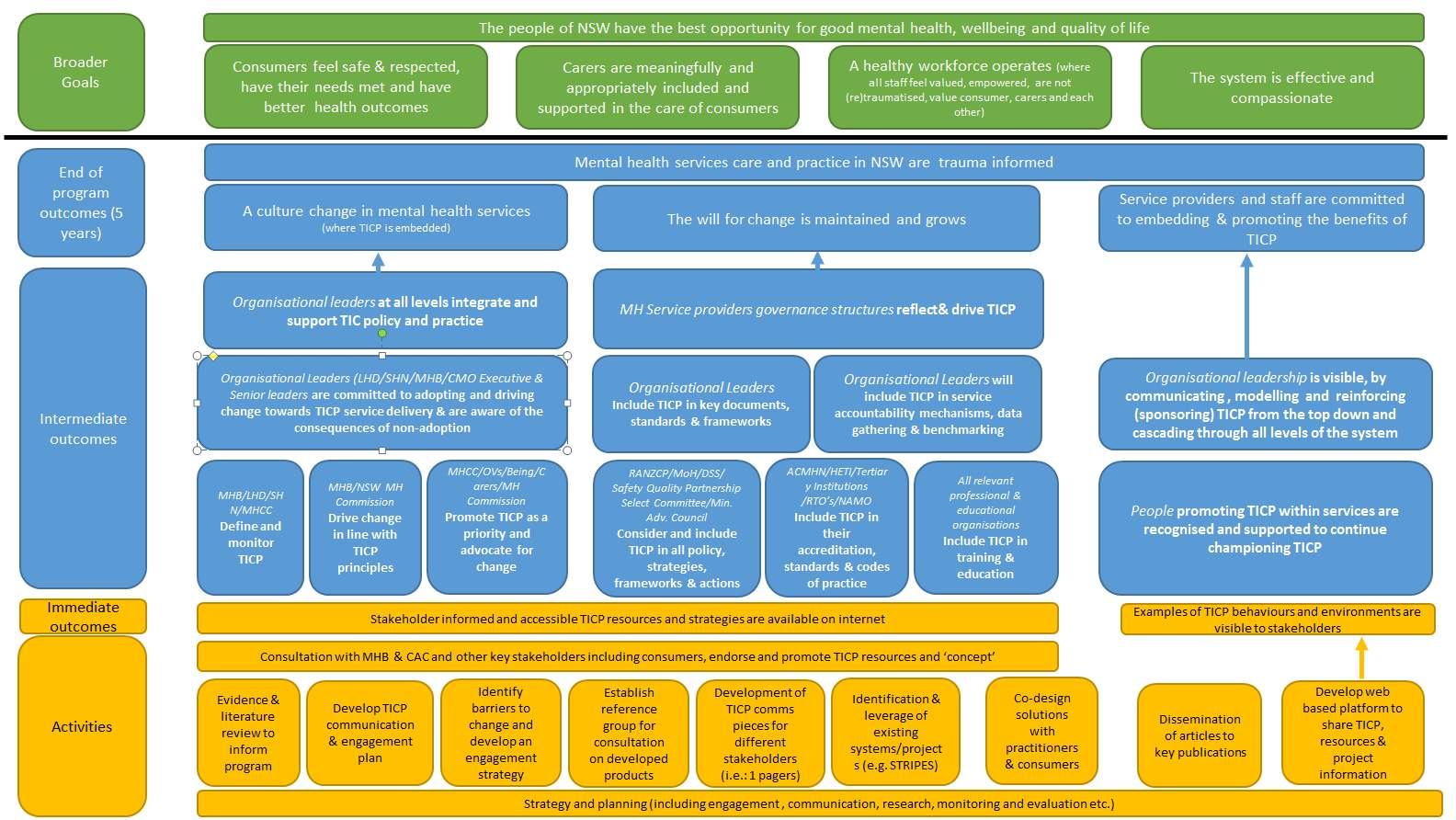

- Program Logic

The TICP project’s five-year end of program outcome is for mental health services in NSW to demonstrate trauma informed care and practice. The Program Logic provides a planning and evaluation framework for the project by understanding the change levers and drivers and will be reviewed at key points during the project

Appendix 1: Case for Change

Background/Issue/Case for Change

Experiences of trauma are highly prevalent in the general population and are endemic in the population of people using mental health services[1]. Trauma has a relationship with the development of mental health conditions and adversely affects the response to care, treatment, service delivery and personal recovery [2,3]. An evidence based approach to trauma-informed care and practice will increase the likelihood of effective treatment, decrease adverse events in care and improve safety for consumers and staff/practitioners. Trauma-informed care and Practice (TICP) is a crucial component of recovery-oriented, person-centred care and practice and reflects best practice.

Definition

Trauma in this context refers to the psychological and neurobiological effects of circumstances or events, often sustained or cumulative, incorporating physical, sexual and psychological abuse or violence of all kinds[4]. Trauma encompasses events, experiences and their impacts[5] and has profound impacts when experienced in childhood or within trusting relationships. .

TICP is an internationally recognised practice approach underpinned by a set of principles that provide health care and treatment based on an understanding of trauma and the recognition of the prevalence of trauma in the lives of those accessing services[6]. An understanding of how trauma impacts the life and experiences of individuals and families; and an appreciation of the benefits of modifying service delivery to reduce the potential for harm in a care setting[7].

Prevalence

The prevalence of lifetime trauma in individuals accessing mental health services has been found to be about 90%[1,8-10]. In addition, the frequency and severity of trauma experiences are much higher among people accessing mental health services than the general population. Rates of lifetime trauma are higher for women [11], Indigenous populations [12,13] and individuals with a disability[14] who also experience mental illness.

Two out of three patients presenting at emergency, inpatient or outpatient mental health settings experience underlying complex trauma secondary to childhood physical or sexual abuse[15]. If emotional abuse, chronic neglect and the impacts of witnessing domestic violence or growing up with significant family violence, substance abuse and poverty are also included, the percentage is much higher [16].

Relationship to mental illness and treatment

Exposure to traumatic events is well known to be linked to the development of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), however, exposure to cumulative, intentional[17] or interpersonal trauma[18], particularly in childhood, is also related to the development of complex trauma. Complex trauma affects the functioning of the person across multiple domains throughout the lifespan [19,20]. Complex trauma and PTSD arising from experiences of trauma are identified as the most significant lifetime risk factors for mental illness [7,17]. The occurrence of trauma is implicated in the development of a range of mental health conditions and has some identifiable and enduring consequences. There is a strong correlation between child abuse, PTSD and psychiatric symptoms [21,22] with up to 76% of adult survivors of childhood physical abuse and neglect having at least one mental health diagnosis, while 50% have three or more diagnoses [23].

Experiences of childhood trauma are significant risk factors for depression and anxiety disorders [24,25] as well as psychosis and schizophrenia [26]. Trauma is associated with more severe symptoms, more suicide attempts as well as the presence of psychotic symptoms in the context of major depression [27]. A history of childhood trauma has been shown to have a negative effect on the course of illness including severity, chronicity and response to treatment [28-31]. Exposure to trauma is likewise correlated with other negative outcomes such as drug and alcohol abuse [32].

Benefits and cost effectiveness of TICP

TICP is being introduced internationally and nationally across diverse human service contexts including mental health and psychosocial support services. While there is a lack of direct evaluation of cost-effectiveness of trauma-informed care approaches, TICP has been shown to dramatically reduce the use of coercive and restrictive practices including seclusion and restraint; improve psychiatric, social and health outcomes for service users; reduce staff injuries and sick leave; improve workplace culture; reduce critical incidents and the use of involuntary medication; and improve consumer experiences of care [33-38]. All of these factors have been shown to reduce costs of service delivery and demonstrate benefits experienced by service users, the mental health workforce and the service in general.

Service users

Currently mental health services often provide care for survivors of trauma without addressing trauma, and often without even being aware that trauma has occurred [33]. Individuals with experiences of trauma can present to numerous services over extended time periods, receive multiple and fragmented interventions that do not address their underlying needs[39].This pattern of care comes at a significant cost to the health services.

Trauma is correlated to the course of illness, severe clinical conditions, self-destructive behaviour and suicide attempts[40,41]. In New South Wales (NSW) approximately 24% of consumers of mental health acute inpatient services leave hospital with no significant improvement in their condition, and for 4%, their health deteriorates during admission [42]. Consumers frequently report experiences in many mental health service settings as counter therapeutic[43] typically occurring as a result of fragmented and coercive service models and practice approaches, along with the experience of a powerlessness due to the interactions with clinicians and other health professionals[44] .

People who have history of trauma are more likely to have experienced coercive and restrictive practices including physical and chemical restraint and seclusion within mental health services [45]. Consumers who experience seclusion and restraint are more likely to have experienced childhood physical or sexual abuse and are more likely to remain in care longer and be readmitted for care[46]. This increases the cost of care and negatively impacts on consumer outcomes and satisfaction with care. The imbalance of power frequently demonstrated in the provider-patient relationship may be reminiscent of abuses of power experienced in other contexts with interpersonal violence [47]. This suggests a need for reconsideration of the way that people who have experiences of trauma receive care within mental health services. A large TICP study found that the single most important predictor of a consumers’ satisfaction of the care received in the service was their therapeutic relationship with mental health (MH) staff [48]. Trauma informed care prioritises safety within the therapeutic relationship and between mental health workers and service users.

A pathway to TICPis through the embedding of recovery-oriented, consumer centred care where the emphasis is on consumer choice, control and a focus on building collaborative partnerships [49]. Enhancement of collaboration, recovery orientation and consumer-centred practice through TICP leads to healthier lifestyles, and self-determination, which in turn can result in economic benefits, improved quality of life and greater productivity[ 50].

Evidence has shown that trauma-informed service settings, have demonstrated better clinical outcomes than ‘treatment as usual with consumers reporting a decrease in psychiatric symptoms[34,35]Positive outcomes include: higher participation rates in health care; sustained agreement with treatment plans; decrease in trauma-related symptoms; increase in effective coping skills; less engagement in sexually-risky behaviours; decrease in alcohol and substance use [51]; and increased housing stability [52]

Mental health workforce

Health care providers have a higher prevalence of lifetime trauma than the general population [53] and individuals who have experienced one or more traumatic events in their own lives are at higher risk of developing secondary traumatic stress [54]. Staff exposed to trauma through their work may experience distress and vicarious trauma (VT) [55]which can significantly impact individuals and service delivery quality. The mental health workplace often places employees at risk of experiencing trauma not only due to the frequency of violence and aggression but as secondary to the nature of the role itself, as a consequence staff are at risk of developing compassion fatigue, burnout syndrome and vicarious traumatisation[56] and mental health and substance use issues [57]all of whichexacerbate rates of absenteeism [58], staff turnover and poor cultures of care [59] which impact on service delivery costs.

Implementation of TICP has been associated with lower staff stress and higher staff morale, increased feelings of job competence and proficiency, a greater investment in the individuals served [60], and positive impacts on the culture of the workplace [61]. After implementation staff report feeling they can challenge their peers when needed, express opinions in team meetings and can deal with team issues in non-hierarchical and more complex ways[62].

TICP training and education have demonstrated improved outcomes for consumers and staff through; improved therapeutic relatedness, consumer self-advocacy, challenging of paternalistic views, decreased use of coercive practices in acute inpatient settingsand when combined with strategies to support workplace culture change, there is a link to a reduction in significant staff injury [49,63] A healthier mental health workforce has clear financial benefits to mental health services.

Service level

Two recent Australian studies conservatively estimated the annual national financial cost of unaddressed childhood trauma as $9.1 billion dollars [64] and $10.7 billion dollars respectively [65]. Many of these costs accrue from the health effects of trauma and inadequate and potentially harmful delivery of care. Positive service level outcomes arising from TICP are most evident regarding seclusion and restraint [66]. Nationally seclusion rates have been reported annually for all jurisdictions since 2008-09 with NSW reporting a rate of 11.1 episodes per 1000 occupied bed days. Focusing on NSW, seclusion rates were lowest in 2013-14 at 7.9 rising to 8.7 for 2015-16. A review into seclusion, restraint and observation will report its findings to the Minister for Mental Health and the Minister for Health by Friday 8 December 2017.

A number of studies reviewing implementation of a TICP approach to decrease seclusion and restraint rates reported an 80% plus reduction [43,67] .In some studies use of TICP has eliminated restraint practices [68] and decreased enforced and overall medication use [67]. In one unit where restraint reduction was targeted, related costs were reduced by 93%, incidental cost savings were observed through positive consumer outcomes, and decreased workforce related costs that included freeing up of clinical time to focus on other aspects of care[69]. Similarly, staff and consumer injuries and sick leave decreased, and a significantly decreased length of stay and readmission rate for consumers was observed. The same study noted that restraint use was claiming 23% of staff time and $1.446 million in staff-related costs which represented nearly 40% of the operating budget for the inpatient service. Their analysis of organisational savings followed a 98% reduction in restraint and seclusion use. Since implementation in 2004, the department estimates a return on their investment to change practice of more than $7 million. These findings have been replicated elsewhere[70] including demonstrating a 90% decrease in critical incidents[71], a decreased median length of stay; a substantial increase in engagement in community services following discharge; and a lower increase in the percentage of people readmitted in the 90 days following discharge[72].

Policy context

Recovery orientation has been widely adopted as an overarching philosophy of practice guiding mental health service delivery and is embedded into policy and practice standards in Australia[73] and is widely accepted internationally and nationally across mental health and psychosocial support services. The principles of TICP and recovery-oriented practice are interrelated and consistent with each other.

The Australian government recognises the importance of trauma informed care services in:

- Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan

- Trauma-informed services and trauma-specific care for Indigenous Australian children.

- Roadmap for national mental health reform

The National Mental Health Commission has also recognised the importance of a TICP approach in:

The 2013/14 the NSW Mental Health Commission emphasised the importance of incorporating and understanding trauma and its effects in mental health service provision as evidenced in the following documents:

- Living Well – A Strategic Plan for Mental Health in NSW 2014-2024.

- Yarning Honestly About Aboriginal Mental Health in NSW 2013.

The NSW Ministry of Health has recognised the significance of responding to trauma and its effects in mental health service provision. This is evidenced in the following New South Wales Health Policy Directives, Guidelines and Plans:

- Aboriginal Mental Health and Well Being Policy 2006-2010 Document Number PD2007_059.

- Aggression, Seclusion & Restraint in Mental Health Facilities – Guideline Focused Upon Older People Document Number GL2012_005.

- Aggression, Seclusion & Restraint in Mental Health Facilities PD2012_035.

- Building Strong Foundations (BSF) Program Service Standards Document Number PD2016_013.Clinical Care of People Who May Be Suicidal Document Number PD2016_007

- Drug and Alcohol Psychosocial Interventions Professional Practice Guidelines Document Number GL2008_009.

- Sexual Safety – Responsibilities and Minimum Requirements for Mental Health Services Document Number PD2013_038.

- Sexual Safety of Mental Health Consumers Guidelines Document NumberGL2013_012.

- The NSW Strategic Mental Health Plan 2014-2024 identifies trauma-informed care as a key workforce training priority for mental health (in development).

TICP project aligns with the ACI strategic plan through working collaboratively with clinicians, consumers and managers to design and promote better healthcare for NSW through demonstrating a culture and practice of collaboration, utilising co-design approaches with consumers and clinicians in the development, design and implementation of solutions (or strategies and resources).

References

- Mauritz, M, W., Goossens, P, J, J., Draijer, N., & Achterberg, T. (2012). Prevalence of Interpersonal Trauma Exposure and Trauma-Related Disorders in Severe Mental Illness. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(1):1-15. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.19985

- Trickett, P. K., Noll, J. G., & Putnam, F. W. (2011). The impact of sexual abuse on female development: Lessons from a multigenerational, longitudinal research study. Journal of Developmental Psychopathology, 23(3), 453–476.

- Pacella, M, L., Hruska, B., & Delahanty, D, L. (2012). The Physical Health Consequences of PTSD and PTSD symptoms: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, (1): 33-46.

- Isobel, S., Goodyear, M., & Foster, K. (2017). Psychological Trauma in the Context of Familial Relationships: A Concept Analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1524838017726424.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. MD Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Harris, M., & Fallot, R. D. (2001). Envisioning a trauma‐informed service system: a vital paradigm shift. New directions for mental health services, 2001(89), 3-22.

- Henderson, C., Kezelman, C. & Bateman J. (2013). Trauma Informed Care and Practice: Towards a Cultural Shift in Policy Reform Across Mental Health and Human Services in Australia. Sydney, NSW: Mental Health Coordinating Council.

- Mueser K, Goodman L, Trumbetta S, et al. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998; 66: 493–499.

- Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Rosenberg SD, et al. Interpersonal trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with severe mental illness: demographic, clinical, and health correlates. Schizophrenia Bull 2004; 30: 45.

- Cusack K, Frueh B, Hiers T, et al. Trauma within the psychiatric setting: a preliminary empirical report. Admin Policy Mental Health 2003; 30: 453–460.

- Felitti, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2014). The lifelong effects of adverse childhood experiences. Chadwick’s child maltreatment: Sexual abuse and psychological maltreatment, 2, 203-15.

- Nadew, G. T. (2012). Exposure to traumatic events, prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol abuse in Aboriginal communities. Rural and remote health, 12(4), 1667.

- Stanley, J., Tomison, A. M., & Pocock, J. (2003). Child abuse and neglect in Indigenous Australian communities. NCPC Issues No. 19

- Frohmader, C. (2002). There is No Justice-: There’s Just Us: the Status of Women with Disabilities in Australia. Women with Disabilities Australia.

- Read, J., Os, J. V., Morrison, A. P., & Ross, C. A. (2005). Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 112(5), 330-350.

- Najman, J. M., Dunne, M. P., Purdie, D. M., Boyle, F. M., & Coxeter, P. D. (2005). Sexual abuse in childhood and sexual dysfunction in adulthood: An Australian population-based study. Archives of sexual behavior, 34(5), 517-526.Nadew, G. T. (2012). Exposure to traumatic events, prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol abuse in Aboriginal communities. Rural and remote health, 12(4), 1667.

- Santiago, P. N., et al. (2013). “A systematic review of PTSD prevalence and trajectories in DSM-5 defined trauma exposed populations: intentional and non-intentional traumatic events.” PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 8(4): e59236.

- Benjet, C., et al. (2016). “The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium.” Psychological Medicine 46(2): 327-343.

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5, 377–391.

- Forbes, D., Fletcher, S., Parslow, R., Phelps, A., O’Donnell, M.,Bryant, R. A., . . . Creamer, M. (2012). Trauma at the hands of another: Longitudinal study of differences in the post traumatic stress disorder symptom profile following interpersonal compared with non-interpersonal trauma. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 73, 1–478.

- Hart, H., & Rubia, K. (2012). Neuroimaging of child abuse: a critical review. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 6.

- Chen, L.P., Hassan Murad, M., Paras, M.P., et al. (2010) Sexual Abuse and Lifetime Diagnosis of Psychiatric Disorders: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Mayo Clin Proc. 85(7):618-629

- Harper, K., Stalker, C. A., Palmer, S., & Gadbois, S. (2008). Adults traumatized by child abuse: What survivors need from community-based mental health professionals. Journal of Mental Health,17(4), 361-374.

- Heim CM and Nemeroff CB (2001) The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: Preclinical and clinical studies. Biological Psychiatry 49: 1023–1037.

- Oquendo M, Brent D. A, Birmaher B, Greenhill L, Kolko D, Stanley B, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder comorbid with major depression: Factors mediating the association with suicidal behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:560–566

- Cutajar, M. , Mullen, P.E., Ogloff, J.R., Thomas, S.D., Wells, D.L. and Spataro, J. (2010) Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders in a Cohort of Sexually Abused Children Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(11):1114-1119

- Gaudiano B. A, Zimmerman M. The relationship between childhood trauma history and the psychotic subtype of major depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2010;121:462–470.

- Rosenberg S. D, Lu W, Mueser K. T, Jankowski M. K, Cournos F. Correlates of adverse childhood events among adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(2):245–253.

- Assion H.-J, Brune N, Schmidt N, Aubel T, Edel M.-A, Basilowski M, et al. Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder in bipolar disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44:1041–1049.

- Kauer-Sant’ Anna M, Tramontina J, Andreazza A. C, Cereser K, da Costa S, Santin A, et al. Traumatic life events in bipolar disorder: Impact on BDNF levels and psychopathology. Bipolar Disorders. 2007;9(Suppl. 1):128–135

- Leverich, G. S., McElroy, S. L., Suppes, T., Keck, P. E., Denicoff, K. D., Nolen, W. A., … & Autio, K. A. (2002). Early physical and sexual abuse associated with an adverse course of bipolar illness. Biological psychiatry, 51(4), 288-297.

- Dorrington, S., Zavos, H., Ball, H., McGuffin, P., Rijsdijk, F., Siribaddana, S, & Hotopf, M. (2014). Trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder and psychiatric disorders in a middle-income setting: prevalence and comorbidity. The British Journal of Psychiatry, bjp-bp.

- Bateman, J., Henderson, C., & Kezelman, C. (2013). Trauma-informed care and practice: towards a cultural shift in policy reform across mental health and human services in Australia, a national strategic direction. Position paper, Mental Health Coordinating Council.Bebbington,

- Cocozza, J J, Jackson, E W & Hennigan, K, 2005, ‘Outcomes for women with co-occurring disorders and trauma: Program-level effects’, Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 2005, 28, pp 109–19

- Morrissey, J. P., Jackson, E. W., Ellis, A. R., Amaro, H., Brown, V. B., & Najavits, L. M. (2005). Twelve-month outcomes of trauma-informed interventions for women with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatric Services, 56(10), 1213-1222.

- Ashcraft, L. & Anthony, W. (2008). Eliminating seclusion and restraint in recovery-oriented crisis services. Psychiatric Services, 59 (10), 1198–1202.

- Chandler, G. (2008). From traditional inpatient to trauma-informed treatment: Transferring control from staff to patient. Journal of Psychiatric Nurses Association, 14, 363–371.

- Clark, C., Mazelis, R., Young, M. S. et al. (2008). Consumer perspectives of integrated trauma-informed services among women with co-occurring disorders. The Journal of Behavioural Health Services and Research, 35, 71–90.

- Harris, M., & Fallot, R. D. (2001). Envisioning a trauma‐informed service system: a vital paradigm shift. New directions for mental health services, 2001(89), 3-22.

- Barnow, S., Plock, K., Spitzer, C., Hamann, N., & Freyberger, H. J. (2005). Traumatic life events, temperament and character in patients with borderline personality disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Verhaltenstherapie, 15, 148-156.

- Sar, V., Kundakci, T., Kiziltan, E., Yargic, I. L., Tutkun, H., Bakim, B., … & Özdemir, Ö. (2003). The Axis-I dissociative disorder comorbidity of borderline personality disorder among psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 4(1), 119-136.

- NSW Mental Health Commission (2014). Living Well: Putting people at the centre of mental health reform in NSW. Sydney, NSW Mental Health Commission.

- Cleary, M. (2003). The challenges of mental health care reform for contemporary mental health nursing practice: Relationships, power and control. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 12 (2), 139–147.

- Domino, M E, Morrissey, J P, Chung, S, Huntington, N, Larson, M J & Russell, L A, 2005, ‘Service use and costs for women with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders and a history of violence’, Psychiatric Services, 2005, 56, pp 1223–32 113

- Frueh, B, Knapp, R, Cusack, K, Witnessing, J, Grubaugh, A, Sauvageot, J, Cousins, V, Yim, E, Robins, C, Monnier, J & Hiers, T, 2005, ‘Patients’ Reports of Traumatic or Harmful Experiences within the Psychiatric Setting’, Psychiatric Services, Vol 56(9)

- Borckardt, J. J., Madan, A., Grubaugh, A. L., Danielson, C. K., Pelic, C. G. & Hardesty, S. J. (2011). Systematic investigation of initiatives to reduce seclusion and restraint in a state psychiatric hospital. Journal of Psychiatric Services, 6, 477–483.

- Aaron, E., Criniti, S., Bonacquisti, A., & Geller, P. A. (2013). Providing sensitive care for adult HIV-infected women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 24(4), 355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.03.004

- Clark, C., Mazelis, R., Young, M. S. et al. (2008). Consumer perspectives of integrated trauma-informed services among women with co-occurring disorders. The Journal of Behavioural Health Services and Research, 35, 71–90.

- Ashmore, T. (2013). Implementation of Trauma Informed Care in Acute Mental Health Inpatient Units. Wellington: Massey University.

- Chandler, G. (2008). From traditional inpatient to trauma-informed treatment: Transferring control from staff to patient. Journal of Psychiatric Nurses Association, 14, 363–371.

- Gatz, M., Brounstein, P. & Noether, C. (2007). Findings from a national evaluation of services to improve outcomes for women with co-occurring disorders and a history of trauma. Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (7), 819–822.

- Rog, D J, Holupka, C S & McCombs-Thornton, K L, 1995, ‘Implementation of the Homeless Families Program 1, Service Models and Preliminary Outcomes’, American Journal Orthopsychiatry, 1995, 65, pp 502–13 109

- Esaki, N., & Larkin, H. (2013). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among child service providers. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 94(1), 31-37. Figley, C. R. (Ed.) (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. NY: Brunner/Mazel.

- Choi,G. (2011). Organizational impacts on the secondary traumatic stress of social workers assisting family violence or sexual assault survivors. Administration in Social Work, 35, pp. 225–242

- Maguire, G., & Byrne, M. K. (2017). The Law Is Not as Blind as It Seems: Relative Rates of Vicarious Trauma among Lawyers and Mental Health Professionals. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 24(2), 233-243.

- Franza, F., Del Buono, G. & Pellegrino, F. (2015). Psychiatric caregiver stress: Clinical implications of compassion fatigue. Journal of Psychiatric Danub, 27, 21–27.

- Lamont, S., Brunero, S., Perry, L., Duffield, C., Sibbirt, D., Gallagher, R., & Nicholls, R. (2016). ‘Mental Health Sick Day’ sickness absence among nurses and midwives: workplace, workforce, psychosocial and health characteristics. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 00(0), 000-000. Doi: 10.1111/jan.13212

- Handran, J. (2015). Trauma-Informed Systems of Care: The Role of Organizational Culture in the Development of Burnout, Secondary Traumatic Stress, and Compassion Satisfaction. Journal of Social Welfare and Human Rights, 3(2), 1-22.

- Marner, S. (2008). The Role of Empathy and Witnessed Aggression in Stress Reactions Among Staff Working in a Psychiatric Hospital. (Published Doctoral thesis). Camden, NJ: The State University of New Jersey.

- Stein, B. D., Kogan, J. N., Magee, E., & Hindes, K. (2011). Sanctuary Survey-Final State Report.

- McSparren, W. M. (2007). Models of Change and the Impact on Organizational Culture: The Sanctuary Model® Explored (Doctoral dissertation, Robert Morris University).

- Rivard, J.C., Bloom, S. L., McCorkle, D. and Abramovitz, R. (2005) Preliminary results of a study examining the implementation and effects of trauma recovery framework for youths in residential treatment. Therapeutic Community: The International Journal for Therapeutic and Supportive Organizations 26(1): 83-96

- Barton, S. A., Johnson, R. & Price, L. V. (2009). Achieving restraint-free on an inpatient behavioural health unit. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing, 47, 34-40.

- Kezelman, C., Hossack, N., Stavropoulos, P., & Burley, P. (2015). The cost of unresolved childhood trauma and abuse in adults in Australia. Sydney: Adults Surviving Child Abuse.

- Taylor, P., Moore, P., Pezzullo, L., Tucci, J., Goddard, C. and De Bortoli, L. (2008). The Cost of Child Abuse in Australia, Australian Childhood Foundation and Child Abuse Prevention Research Australia: Melbourne.

- Ashcraft, L. & Anthony, W. (2008). Eliminating seclusion and restraint in recovery-oriented crisis services. Psychiatric Services, 59 (10), 1198–1202

- Murphy, T., Bennington-Davis, M. (2005). Restraint and Seclusion: The model for eliminating their use in healthcare. Marblehead, MA by HC Pro, Inc.

- Barton, S. A., Johnson, R. & Price, L. V. (2009). Achieving restraint-free on an inpatient behavioural health unit. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing, 47, 34-40.

- LeBel, J., & Goldstein, R. (2005). Special section on seclusion and restraint: the economic cost of using restraint and the value added by restraint reduction or elimination. Psychiatric Services, 56(9), 1109-1114

- Chan, J., LeBel, J., & Webber, L. (2012). The dollars and sense of restraints and seclusion. Journal of law and medicine, 20(1), 73.

- Banks, J.A; Vargas, A., (2009). Contributors to Restraints and Holds in Organizations Using the Sanctuary Model. 2009, The Sanctuary Institute, www.thesanctuaryinstitute.org.

- Stein, B. D., Sorbero, M., Kogan, J., & Greenberg, L. (2011). Assessing the implementation of a residential facility organizational change model: Pennsylvania’s implementation of the Sanctuary Model. Retrieved from http://www. ccbh.com/aboutus/news/articles/SanctuaryModel.php.

- Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council 2013, The National framework for recovery oriented mental health services: Policy & Theory.

Appendix 2: High Level Project Deliverables

A more detailed project plan sits behind this high level plan that provides detailed activities to achieve deliverables.

| Phase | Deliverable | Timeframe |

| 1 | Project Initiation Proposal ( PIP) endorsed | December 2017 |

| Undertake Program Logic | December 2017 | |

| 2 | Develop content & establish web page | January 2018 |

| Project Communication/Engagement plan completed | January 2018 | |

| Devolve Advisory group and establish Reference group | February 2018 | |

| Current TICP service provision & training published on web site | March 2018 | |

| 3 | Diagnostic & Solution Design commences | January 2018 |

| Focus groups completed | April 2018 | |

| Survey completed & data analysed | May 2018 | |

| TICP strategies & resources developed | June 2018 | |

| TCIP self-assessment tool complete | July 2018 | |

| Evaluation framework complete | June 2018 | |

| Pilot sites identified | June 2018 | |

| 3 | Implementation and evaluation of TICP pilots commence | July 2018 |

| 4 | Evaluation of TICP sites complete | March 2019 |

Appendix 3: Project Methodology

Phase 2: Solution design

The solution phase will provide an opportunity to generate and select ideas and design agreed solutions to improve the outcomes and experience of people who access mental health services in NSW. The aim is to understand and articulate what practical approaches can be used to implement Trauma Informed Care. Solutions will be identified, prioritised then tested with stakeholders prior to their development.

The solution phase will use the following codesign method

- Pilot a Consumer led consumer focus group including questions and thematic analysis. Groups will be run by consumer researcher and CE Being.

Check in with group to: Refine questions, discuss theming and review process

- Four consumer led focus groups: With the aim to reach data saturation & to inform focus group questions for mental health staff. The four areas were identified to represent metropolitan, regional and rural areas with strong Aboriginal Medical Services. This will facilitate Aboriginal participation through the assistance of Phillip Orcher, PEACE.

Check in with group to: review themes and process

- Four codesigned and led focus groups for staff/practitioners. Led by Clinician ( EWG) and consumer researcher supported by MH Network Manager and ACI Implementation Manager

Thematic analysis of groups reported back to group

4 Develop, test and execute codesigned survey (Cemplicity) for consumers and staff

5 Develop solutions & resources for implementation

Project Approved / Not Approved by Chris Shipway

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Mental Health"

Mental Health relates to the emotional and psychological state that an individual is in. Mental Health can have a positive or negative impact on our behaviour, decision-making, and actions, as well as our general health and well-being.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: