Immigration in a post-Celtic tiger era Ireland

Info: 9004 words (36 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Tagged: Immigration

“Immigration in a post-Celtic tiger era Ireland. Did the Celtic Tiger draw migrants to Ireland?”

An investigation into how small towns have adapted to becoming a multicultural and integrated society.

Abstract

The following study will explore migrant’s experience of integration in Ireland. Using a qualitative method which involves interviewing 15 people of a varying age range. The focus of this study is to find out the problems and barriers that the migrants are faced with in the process of integrating into Irish society. Furthermore, an important aspect of the research was to establish the period in which the migrants came to Ireland, in particular if they came to Ireland during the economic boom or during our most recent recovery from the economic crisis. Despite the fact that some of the respondents articulated negative experiences of integration in Ireland, some have also stated that they had positive experiences of integration. Various factors including cultural differences, discrimination and racism, qualifications and training courses were some of the aspects that contributed to those varied experiences. It is evident from this research that the situation is gradually changing and improving in terms of integration into Irish society, however there is still a big room for improvement both from the policy making level and in society’s attitude at large. The overall aim of the research conducted was to suggest efficient ways in which Ireland can become more integrated

Introduction:

This study aims to explore migrant’s experiences of integration in Ireland. It aims to investigate whether or not the Celtic Tiger and the wealth and opportunities it brought along with it was the main attraction for migrants into Ireland. Secondly, it will highlight the main problems migrants face upon their arrival into a new country, with particular reference to Ireland. Furthermore, how Ireland has evolved into a more multicultural society will be analysed. This will also focus on how Ireland has used education to create a more multicultural society.

As the researcher I believe that this study is essential because I believe that it will result in an improved understanding of migrants experiences of integration in Ireland. Migration is a remarkably controversial topic, and it constantly remains a topic of conversation in society. But oftentimes, society tends to forget the question of how well migrants have settled into the society and what their experiences of integration into Ireland are. In Ireland, it has been recorded that the country is taking in 40 migrants every fortnight.

It is more common for society to presume what the experiences of these migrants are, however the actual experiences and what effect they have on their everyday living oftentimes remains hidden to the wider society.

How well migrants feel they’ve settled into society or not can be agreed to have a major impact on every other aspect of their life. This is represented by some of the literature reviewed for this research project. The research will look at the relevant policies and programmes on migrants integration in Ireland, furthermore the study will contribute to identifying key factors that will promote the integration experiences of migrants in Ireland, as well as suggesting steps that societies can take to becoming a more integrated and multicultural society. The decision was made that the most suitable method of research used would be a qualitative method because it allows the migrants to efficiently voice their opinion on the experiences they have of integration in Ireland.

By taking evidence from various academic sources and researchers across different fields of interests, this study will reflect a light on the migrant’s experiences of integration. Furthermore, multiculturalism is explored in the sense that people can use education to evolve society into a more multicultural one for migrants.

Part 1: Research Aims and Objectives

Aim:To analyse Ireland’s current approach to integration, how multicultural the society is and how Ireland can use education to become more integrated.

Objectives:

- To provide a detailed analysis of migration and what causes people to migrate.

- To provide a background to immigration in Ireland before the Economic Boom.

- To analyse the reasons as to why immigration rates in Ireland continue to rise and why Ireland has proved to be so open to immigrants.

- Investigate how well integrated Ireland is, with particular reference to small towns (Letterkenny).

- Analyse how open Ireland is to multiculturalism.

- Provide suggested steps that societies can take to becoming more integrated (i.e. through the use of education).

Part 2: Literature Review

The main motivation to carry out a study on this particular topic was because of the popularity of the topic over the last year. Migration has become a familiar topic of conversation in society and it continues to affect people worldwide, particularly Irish society. Furthermore, the link between migration and the Celtic Tiger remains a controversial topic. This literature review deals with four main elements – The Celtic Tiger, Integration, Education and Multiculturalism.

To define migration, one would say that it involves the movement of an individual between two places for a certain period of time. In the book entitled ‘Exploring Contemporary Migration’ reasons to why people migrate are discussed in detail. Migration is described as the “international flows of large numbers of refugees stimulated by wars, famine or political unrest; young adults moving between regions in search of employment; middle aged professionals moving back to the land in their search for a rural retreat; families moving down the road to satisfy changing housing requirements, and gypsies and other nomadic peoples for whom mobility is a way of life.” This description of Migration is an accurate representation of the reasons why migrants have chosen to settle in Ireland. A huge number of the migrants who enter Ireland are in search of employment and are forced to leave their previous residence due to war and unrest. Chapter one in ‘Exploring Contemporary Migration’ is essential for my research as its main aim is investigating the significance of migration in shaping and developing people’s lives and experiences in the contemporary world. This is done in a number of ways. Firstly, attention is given to the migration histories of the three authors, which shows very openly that migration has been a vital feature of our lives. Secondly, a more academic account of the importance of migration is sketched. Lastly, the bulk of the chapter is taken up with describing some of the main spatial patterns of migration within both the developed and developing worlds and at the international scale (Boyle et. Al, 1998).

The two biggest studies to date in Ireland specifically on migrant’s integration experience wee studies carried out by Coakley and Mac Einri (2007) , which investigated the Integration experience of African families in Ireland. The study carried out highlights the need for ‘government coherent approach in addressing migrant’s access to education and training, language provision, employment opportunity and recognition of foreign qualifications’ in an attempt to improve better integration of African families in Ireland. It can be said that the views of these migrants may represent the views of migrants of other origins also.

What exactly is migration?

It is well established that migration is a result of a collection of factors including social, economic, cultural, political, institutional, psychological, and physical, considerations that independently or together may influence the way in which a migration decision is made or enacted. It is the central process that involves the redistribution of people over the surface of the earth. It has insightful implications both for governments at all levels in providing infrastructure and human services, and for the private sector in affecting the size and nature of markets for goods and services (Golledge and Stimson, 1997).

It is said that migration into Ireland is one of the biggest demographic changes to affect Irish society since the famine (Curry et al, 2010). During both of these periods, Ireland experienced a dramatic increase in population. Ireland experienced a dramatic rise in immigration, it was a phenomenon that has been mainly absent for most of its recent history (Share et al, 2007). Various contributing factors to the inflow of migrants to Ireland have been noted. One of the factors was the economic growth – Ireland was ranked as the 3rd richest country during its economic boom. Share has stated that ‘since the 1990’s, Ireland saw the emergence of a very different Ireland, the population profile has changed radically… different factors are said to have contributed to this’ (Share, 2007. P.144).

It can be said that every migrant has a very diverse reason as to why they have left their country of origin to migrate to another. These reasons are most commonly for employment opportunity, education, or just a better quality of life.

. There are various categories of migrants, for example: economic migrants or migrant worker, asylum seekers, refugee, international students etc. According to the Central Statistics Office (CSO) there were 419,733 non-Irish persons resident and present in the State on Census night of 2006. Approximately 275,000 of these persons were of EU nationality, 24,000 from the rest of Europe, 35,000 from Africa, 47,000 from Asia and 21,000 from America (CSO, 2016). It is said that many of these migrants still remain in Ireland today, and the CSO results continue to have a similar pattern

Argaiz and King have stated that “since the collapse of its Celtic Tiger Economy, Ireland has experienced not only a reversal of fortune but also of migratory flows that have transformed it from an emigrant-sending to an immigrant-receiving society, and then into a nation of emigrants once again (Argaiz and King, 2017). This is an accurate depiction of the change in Irish society in terms of the movement of migrants in and out of the country. This instable situation has led to rapidly changing views of migrants coming to and going from Ireland. Public expectations that non-Irish migrants would return to their countries of origin in times of economic recession have proven to be wrong. Most immigrants were Here to Stay, as expressed succinctly in the title of a 2000 documentary film by Alan Grossman and Áine O’Brien. The presence of these immigrants in post-Celtic Tiger Ireland, however, seems to be outshined by other realities. The intense and often contested debates on migration that dominated the headlines of Irish newspapers and broadcast media during the boom years predictability dissipated. “As daily news of bank bailouts and draconian budget cuts, mortgage defaults, debts, house repossessions and emigration fill the post-Tiger Irish air with despair and bewilderment, no one mentions diversity and integration any longer”, notes Ronit Lentin (Fanning,Bryan. Immigration and Social Cohesion in the Republic of Ireland. Manchester: Manchester University Press) while the Irish state focused its efforts in recovering from the economic downfall, the focus of the media shifted away to other heated concerns, not only the dire recession of the country and the new austerity measures but also many political and religious scandals of recent years” (Argaiz and King). Therefore, even in the downfall of the economy, migrants still remained in Ireland, due to the remaining opportunities that the country offered. According to local news, Donegal is to welcome 30 new migrant families by the end of 2018, under the refugee resettlement programme.

When defining integration, as it is cited in the article ‘European Migrants in Ireland: Pathways to Integration’ it is broadly defined as how ‘newcomers to a country become part of society’ (Castles et al., 2002). Immigration in Ireland has dramatically risen, particularly during the post- economic crisis period in 2008. This has had a huge effect on both the social and economic development of Ireland as a country. As a result of this, it has hindered the development of Ireland becoming a well-integrated society. The Celtic Tiger period left a lasting legacy on the Irish population, leaving a period of rapid economic growth which lead to the transformation of the Republic of Ireland into a more multi-ethnic society, with a large permanent immigration population.

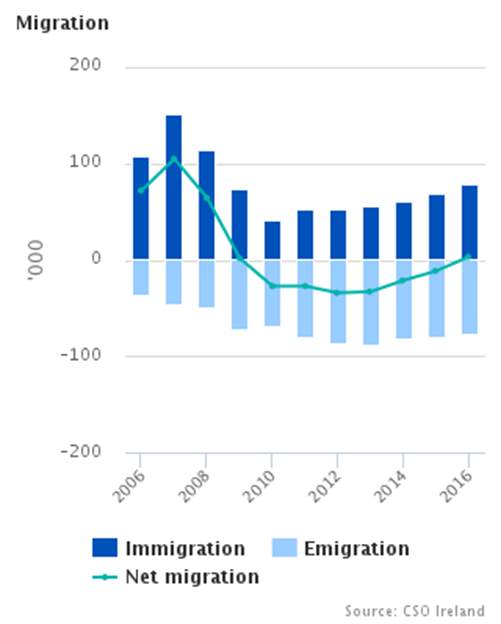

It has been noted that there has been a lack of progress in the field of integration since late 2007. This is due to the financial difficulties which Ireland experienced since then. The financial crisis and dramatic rise in unemployment resulted in April 2009 in a return to net migration for the first time since 1995. These developments have meant that integration is no longer as instantaneous an issue as it was between 2000 and 2007 and it slipped down the political agenda. Furthermore, the punitive budgetary measures associated with the financial crisis have impacted on the equality and integration infrastructure through, for example, the closing of the National Consultative Committee on Racism and Interculturalism and the cuts in funding for the Human Rights Commission and Equality Authority (Murphy, C. 2015).

In the years leading up to the Celtic Tiger, the growth of global economic activity resulted in a worldwide increase in migration. The number of immigrants to the State in the year to April 16 is estimated to have increased by almost 15% from 69,000 to 79,300, while the number of emigrants declined over the same period, from 80,900 to 76,200. These combined changes have resulted in a return to net inward migration for Ireland with a surplus of 3,100 for the first time since 2009 (CSO, 2016). With such a dramatic rise in immigrants, it is a logical suggestion that this would also serve as a challenge for Ireland in becoming more integrated. It can be said that perhaps services were not prepared to cope with such an drastic influx of migrants into the country, and as a result, every migrant that settled into each town was not receiving adequate assistance in settling into their new locality. Furthermore, there would have been less of a focus on Multiculturalism, and more of a focus on establishing key services like housing.

Integration

Bernard defines integration as, “integration is achieved when migrants become a working part of their adopted society, take on many of its attitudes and behaviour patterns and participate freely in its activities, but at the same time retain a measure of their original cultural identity and ethnicity” (Kuhman 1991). Bulcha adds that this need not imply harmonious equilibrium as “conflict is naturally part of the relationship” (Ibid). For Kuhman the problem with this view is that integration cannot be measured against anything other than marginalisation, and thus it fails somewhat against the predictive requirements of theory making. Nevertheless, one key component for Kuhman is that migrants maintain their own identity while also becoming part of the host society. Kuhlman argues for the multi-dimensionality of integration, involving spatial, economic, political, legal, psychological and cultural factors (Ibid 9), while Castles et al point to the influence of ‘structural factors’, which differ according to migrant type (Ibid).

There are many aspects of society which are taken into consideration when judging how well integrated a particular area is. These include education, employment, language, etc. With such a huge number of migrants entering the country every year, it can be said that Ireland has experienced difficulties with becoming an integrated society, particularly amongst children. It can be said that Integration is linked to stability, how stable a migrant feels in her ‘new’ country. Migrant children, in particular, struggle with stability. In the book entitled ‘Spacing Ireland: Place Society and Culture in a Post-Boom era’, chapter four focuses on a case study carried out on a group of young migrants of the CEE nationality. An aspect of stability that all of the migrant young people discussed was their national identity. They often felt that their lives were in a state of flux, precarious because of their mobile situations, and it was their sense of belonging to a national collective that enabled them to maintain and develop their sense of self, their identity, while encountering change. For example, rather than considering that they were able to develop hybridised identity, such as Lithuanian- Irish or Polish-Irish, young people from CEE countries were keen to emphasise their singular national identity (Tyrell, 2013). It appeared that from migrating into Ireland, that their experience was so positive, they were eager to migrate more. It is stated in the conclusion of this case study that ‘having experienced migration once, adjusting to a new country and culture and living internationally, the prospect of migrating again was not off-putting for some CEE young people”.

In a report published by ….. On education and migration, it states that European societies must acknowledge that they have merged into immigration countries and that a significant proportion of their young people are and increasingly will be, migrants or of migration background. Due to major demographic processes this trend will not be reversible in the foreseeable future. All major institutions, and particularly educational institutions of all kinds, have to adapt to this situation and develop new kinds of services

To focus on Letterkenny, Donegal in particular, accessing employment remains as big a challenge as ever before for members of minority communities in Donegal. Participants in a conference held in Letterkenny on ‘Migrant Rights, Employment, and Supports’ provided evidence that included the persistent lack of African employees in customer service positions at a number of large department stored and retailers in the county, as well as problems that highly qualified applicants from a range of minority communities are having getting hired even for the positions that they are over-qualified for. Stephen Barrett of DLDC explained that “Despite that having the skills and being over-qualified for the jobs, there are still barriers accessing available job opportunities”. He stated that the real question is “What can we do to better educate employers, to better engage with employees, and to increase access to employment opportunities?”

Key issues brought to the attention of the Donegal Intercultural Platform are that they are experiencing exclusion, discrimination, isolation and racism in Donegal, said Paul Kernan, head of the Intercultural Platform in Donegal.

Discrimination

Discrimination is a topic that has a depth of literature. Discrimination is a problem for both minority groups and the societies in which they live. It is a problem for the migrants that have to experience it, but it is also a problem that people in the receiving society must learn to overcome and perhaps diminish. Perceptions of discrimination among migrants can influence sense of belonging and well-being (Safi, 2016). Discrimination in the workplace can have adverse effects on the migrant’s mental health, as well as their confidence and self-esteem. A growing body of research examines the role that discrimination plays in affecting how individuals identify with the host country versus identifying with their own group (Diehl et al, 2016). Furthermore, discrimination can play a role in acculturalisation, with those perceiving group discrimination being less likely to adapt to the host country in terms of attitudes (Roeder and Lubbers, 2016). To the extent that immigrants lack a sense of belonging, feel unfairly treated and retreat into separate identities, this can put major pressure on social cohesion (De Vroome et al., 2014).

In Letterkenny, it can be said that discrimination is higher among Black Africans than white EU migrants, of which Poles are the majority. This is represented by Kingston’s finding that the experience of discrimination much higher among Black African’s than white EU migrants.

The question of why Ireland has proven so open to immigration must be answered. In the article ‘Immigration, the Celtic Tiger and the economic crisis’ the reasons to this puzzling question are critically analysed. It compares responses to immigrants in the Republic of Ireland during the Celtic Tiger era and during the post-2008 economic crisis and finds no evidence of a political backlash during the latter period even though opinion polls suggested that refusal to immigration had increased and other evidence suggested that there had been an increase in racist incidents within Irish society. It also suggests that it wasn’t the continuation of large-scale emigration that triggered political hostility to immigrants (Fanning, B. 2015). As stated in the second paragraph, the Celtic Tiger left a lasting legacy on the Irish population. One of these legacies is the transformation of Ireland into a multi-ethnic society with the population being largely made of permanent immigration. The 2006 census identified 419, 733 non-Irish citizens as living in the country. By 2011, when the next population census was taken, the number had risen to 544,357. Ireland’s immigrant population appeared to have increased during the economic crisis. Interestingly, it peaked in 2008 at over 575,000, or 12.8% of the population. The population then declined slightly during the economic crisis to 550,400 in 2010 but rose to 564,300 by 2014. This eventually bottomed out in 2010 at around 41,000 and rose in the years that followed. Unemployment levels during the boom averaged at around 4%. By July 2008 this level had risen to 6.5%,, then dramatically to 14.8% by July 2012(CSO, 2016).The table below illustrates this increase in population:

(CSO,2016)

(CSO,2016)

From these statistics, a conclusion can be drawn that Ireland has welcomed these ‘New Irish’ into Ireland. In a special ceremony in which Taoiseach Enda Kenny addressed some of the 2250 new Irish citizens from 110 countries who pledged their allegiance to the Irish state, he told them to make Ireland their proud home (Fanning, B. 2015). But, this leads to a very significant question- are these immigrants proud to call Ireland their new home? Do they feel welcome in their new country? Tyrell offers an interesting answer to this question. She focuses on the younger migrant population. She states that in some ways, young people who migrated to Ireland from countries that joined the EU in 2004 are quite a privileged group of in comparison to other groups of migrant young people. She suggests that this is due to the fact that they have free movement within the EU and their family migrations to Ireland were unrestricted. Furthermore, their ability to move freely between countries was not lost on the young people themselves when considering their plans for the future. On the contra to this, adult migrants from CEE often experienced de-skilling or under-skilling in Ireland, gaining places in the labour market that were below their qualifications and skills level. More often this is has been seen by migrant workers as being beneficial and worthwhile because of wage differentials between their home country and Ireland, even when working in jobs that they would not have considered doing at home. In comparison to this however, for the younger migrant population and parents in this particular piece of research, tough economic considerations had motivated many of their moves, migration was not considered to be a short-term measure. It was often part of the plans they made with their family in which financial gains were essentially the most important. Tyrell then gives a relevant example, stating that the advantages of learning English were recognised by these young people and their parents, some also spoke of Ireland offering a better family environment than their home countries, with less crime and drug related problems. Although these points could be debated and, to an extent, depend on the location in Ireland to which families moved, it is remarkable that particular areas in Ireland followed these lines (Tyrell, N. 2013). This can be seen within my case study on Letterkenny within this dissertation project as Letterkenny is known to be a town with a very low crime rate with a large migrant population.

Migrants may experience difficulties settling into Irish society. These problems may include employment difficulties due to language barriers, cultural difficulties, racism and discrimination. Other employment difficulties may include their qualifications not meeting the standard of the job they are applying for, such a standard may be acceptable for a similar job position in their country of origin.

International Experience

In relation to where other countries position themselves in the problem of integration at the EU level, the European Council adopted eleven Common Basic Principles for EU immigrant integration policy. These principles focus on integration in terms of a two-way process, while integrating many of the socio-cultural apprehensions articulated in some of the member states’ national integration programmes. Despite this, Boucher stated that European Union integration policies are not legally binding on member states. It states that the exact integration measures a society chooses to take should be determined by individual states, reflecting each individual member states, individual history and legal framework (Boucher, 2008).

As well as discussing integration policy or model in the European context, it is also vital to look at integration model of different countries, for example countries such as France adopted an assimilation model of integration which means that migrants will not display their culture, religion, or national identity in public places. This is a one way process in that migrants will eventually give up their unique, social and cultural characteristics such as language and adapt to the lifestyle of the majority culture and the value systems of the host society (Cagiano de Azavedo and Sannino, 2004). However, the migrant human rights are as equal as those of any French Citizen. On the other hand for countries such as Canada and Australia, they practice a multicultural model. This is where migrants will not be required to repress their national identity, culture or religion. They interact with the majority culture, they learn the core values and culture of their host while at the same time also maintaining their cultural identity.

The migrants retain their culture and at the same time, learn the values, and culture of their host countries (Boucher, 2008). However, since the incident of 9/11, there has been a shift in the thinking on whether multiculturalism is the best way to go or not and it has stirred up debates by political leaders. For example, Merkel Germany chancellor and British Prime Minister David Cameron, claimed that multi-culturalism has failed, although the same Merkel once claimed that multiculturalism is the way forward. What is crucial is to look critically on the model that will best support the migrants. This issue continues to generate ongoing debates. In Irish context, integration policy or legislation previously has focused on immigration mainly on asylum seekers and refugees. It hasn’t focused on the integration of migrants into society.

However, since 2007, there has been various steps taken to improve and enhance the experience integration of the migrants. It must be noted that Ireland are at an advantage as they have the opportunity to learn from other countries, whether good or bad. Perhaps if legislation aimed to promote the integration of migrants into Irish society, then the Irish population will have a more positive attitude towards welcoming migrants into the country.

Migrants’ integration experiences in Ireland and Barriers to their Integration experiences

Castles and Miller (1998) have stated that the experiences of migrants are significantly shaped by the policies and practices of the state. It has been previously argued that migrants’ incentives for migration are an imperative variable in understanding their experiences. Each migrant’s experience of integration differs from one another, and how migrants settle does not occur at a similar rate across all aspects of life. Integration issues can arise long after arrival, some members of the migrant family may be well integrated while others are not. It is vital o note that some migrants may be well settled in one dimension of their life. For example, they may be well settled into employment but poorly integrated in other aspects (i.e. socially), which could lead to isolation and in turn impact on their sense of well-being, self-esteem and on their mental health (Coakley and Mac Einri, 2007). This, therefore could suggest that instead of integrating migrants into society in terms of Employment, ensure that they feel that they have integrated in terms of feeling they are a part of the community.

Methodology

In order to achieve the overall aim of this study, the methodology outlined below will be followed. The data collected from this research will be both qualitative and quantitative. Quantitative data collection in the area of migration has been a fast developing area in the past decade, marked by growing efforts to harmonise statistics on the national level as well increasing efforts to extend systematic data collection on migrants over and beyond core demographic data. The census is both the most important and most reliable sources of information. A population census can be defined as a full enumeration of the population. Furthermore, they provide extensive information on the total population who have a migration background.

Another method of data collection which is appropriate for the study area that I will use is sample surveys. A sample survey is a statistically representative survey of a sample of the population or part of the population. This will be a vital part of my research project as surveys are a major source of providing information on migration and integration, two key parts of my research. The main advantage of using a sample survey is that they are very rich in information. Furthermore, they allow the collection of data that may have been of a limited extend available from registers. This includes relational information or information on views and experiences of respondents. Surveys will therefore allow the generation of comparable data through harmonised indicators and questionnaire items. In previous research projects based on the area of Migration, problems were encountered with accurately sampling migrants. This was mainly due to the sample sizes being too low, which meant only simple statistical analyses on simple categories of migrants was allowed. I will overcome this problem in my project by creating specific migrant surveys and personally distribute them at a migrant group meeting which is held in the local Library in Letterkenny.

Government Reports:

To establish a solid foundation on the current flows of migration, it is essential that I collect records from government offices. In particular, I will collect information from the Central Statistics Office online on population numbers and focus on Letterkenny which is my case study for this research project. These records will then be carefully analysed and organised into detailed charts illustrating the growth and decline in populations of migrants within the areas.

Survey:

A survey was conducted which focused on the Migrant population in Letterkenny. The sample population was a group of 15 migrants who have recently settled in Letterkenny. The survey addressed the topic of Migration, requesting their experiences with employment and integration.

Results

The following table represents the results obtained from the surveys carried out at a Migrant Group meeting in Letterkenny in March, 2017.

| Respondant

|

Age | Status on Arrival | Birthplace | Year of Arrival to Ireland, and what attracted you to Ireland? | Job | Did you have difficulties finding a job? | Social Issues

Experienced |

||

| 1 | 51+ | Work | Italy | 2013, employment opportunities | Retired | Yes | English

Language |

||

| 2 | 41-50 | Work | Poland | 2006, Employment Opportunities | Cleaner | Yes | English

Language |

||

| 3 | 21-30 | Work | Poland | 2008, Employment opportunities | Café Worker | Yes | English

Language |

||

| 4 | 21-30 | Other | Russia | 2016,

Quality of life |

Student | Yes | Visa | ||

| 5 | 41-50 | Work | Poland | 2004,

Employment opportunities |

Cleaner | Yes | Discrimination | ||

| 6 | 21-30 | Volunteer | Turkey | 2017,

Quality of Education |

Counsellor with Migrant Children, Part time Student | No | English Language | ||

| 7 | 21-30 | Study, Family | Afghanistan | 2015,

Quality of Life |

Other | Yes | Discrimination | ||

| 8 | 21-30 | Volunteer | Ukraine | 2017,

Employment Opportunities |

Student | Yes | Cultural Barriers | ||

| 9 | 21-30 | Study | France | 2016,

To Learn English |

Student | Yes | English Language | ||

| 10 | 31-40 | Other | Ukraine | 2015,

Quality of Life |

Unemployed | Yes | Languge and

Qualification |

||

| 12 | 31-40 | Work | Spain | 2017, Employment Opportunities | Social Work | Yes | Language and

Qualification |

||

| 13 | 31-40 | Family Reunion | Latvia | 2010,

Quality of Life |

Unemployed | Yes | Children

Experienced Discrimination |

||

| 14 | 21-30 | Other | Egypt | 2015, Employment Opportunities | Nurse | No | Discrimination | ||

| 15 | 21-30 | Family Reunion | Spain | 2014,

Family |

Retired | No | Language |

Survey Results (contd.)

Discussion:

This survey was carried out over a sample population of 15 migrants, each representing a different minority group. The migrants that took part in the survey also agreed to answer a few questions once the survey was completed. The migrant countries involved were – Italy, Poland, Russia, Turkey, Afghanistan, Ukraine, France, Spain and Egypt.

This selection of respondents ranged between the ages of 21-55. A lot of these migrants moved to Ireland quite recently – which proves that Ireland is still welcoming migrants into the country.

Out of the 15 migrants that took part in the survey, 20% of the respondents were of a Polish nationality (3 out of 15). Ireland is still known as a country that is of a high Pole migrant population.

From the numerous surveys carried out, one migrant stated that “If you come alone and start a new life alone is good, but I think it is very hard for a migrant family. There are so many cultural difficulties and barriers. (Female, 21-30, Spanish). She went on and said that her ‘younger sister experiences a lot of difficulties fitting in to her classroom. She doesn’t have many friends because she doesn’t have good English’. This statement could suggest that Letterkenny needs to evolve into a more multicultural society in order to eliminate these cultural difficulties and barriers. It also suggests that schools must put effective measures in place to ensure that the young migrants attending their school feel that they are part of the school community and that they are receiving all help that is on offer for them on arrival into the new school. A society that is multicultural is vital if it wishes to keep migrants in it. This could suggest that schools need to educate their students from a young age on the topic of migrants and teach them how to become more welcoming towards migrant students. Perhaps these cultural difficulties and barriers that exist in Letterkenny may include

From the results table, it is evident that the main issue experienced by migrants while settling into Irish society was language. Language difficulties can be overcome by setting up conversation classes within the local area. During my research for this project, the opportunity was given to “sit in” and observe the English Conversation class that was held in the local library in Letterkenny town. This class, along with many other services provided to migrants, is run by a programme called “Fáilte Isteach”. On completion of the conversation class, migrants were asked what they gained from taking part in these classes. Most responded that they felt that their English had improved. Whilst talking to a young women, aged 21-30, from Poland, she stated that she had developed some new friendships through the classes as well.

(Source:thirdageireland.ie)

(Source:thirdageireland.ie)

Failte Isteach

Fáilte Isteach is a community based project which involves largely older volunteers through conversational English classes. The project aims to provide the essential language skills to new migrants in a student-centred, welcoming and inclusive manner while involving older volunteers and recognising their skills, expertise and contribution to the community (ThirdAgeIreland).

Problems with Integration identified

Employment and Qualification

It is evident from the results table that the majority of migrants that have moved to Letterkenny have experienced difficulties finding a job that meets their qualifications. Some are currently working in a job that is “way under their qualification standard” (Respondent 3, Polish woman).

Chiswick, Lee and Miller (2005) provide a useful framework in which to analyse and comprehend immigrant integration. In their model, immigrants experience a “U-shaped” pattern of occupational attainment. In transitioning between their last job in their country of origin and the first job in the host country, immigrants are likely to experience downward occupational mobility. Because their skills are not likely to be directly convertible to the new setting, the migrants may need to work in lower-level jobs at the point of their arrival in the host country(Barrett and Duffy, 2008). This is seen in one of the respondent’s situation, where she graduated with a degree in history but struggled to find a job in her country of origin, and continued to find one in Ireland, the country she migrated to.

It is also clear from the research carried out that the majority of migrants that reside in Letterkenny are Polish. Few Poles lived in Ireland before their country gained EU membership in 2004, but this rapidly changed, with increasing numbers moving to Ireland soon after accession. Inflows peaked in 2006 (Krings, 2010), but remained relatively high until the recession. Within only a few years, Polish immigrants became an important presence in Ireland, and are likely to remain so even if some may choose to return or move elsewhere as the economic situation in Ireland worsens (MCA, 2008). As a result, first research findings have been emerging in recent years focusing on Poles living in Ireland, but these studies are largely limited to small scale qualitative studies that can only provide some general insights into Polish migration. This should change in the near future, as various researchers have studied Polish migration and are beginning to publish findings that will address some of these shortcomings. Various factors have been cited to motivate Polish people to come to Ireland. The main push factors are linked to the process of economic and political transition in Poland that was accompanied by falling living standards and rising unemployment (Grabowska, 2003). The goal of Polish migrants was earning and saving money to provide better futures for them and their families back in Poland (Kropiwiec, 2006). These push and pull factors of a mainly economic nature were the main motivation to come to Ireland, but these often went beyond simply earning a certain amount, and included gathering work experience that could be beneficial for their future career (King-O‟Riain, 2008). Many saw no opportunities for professional developments and improvements, and university leavers in particular were often quite disillusioned about the opportunities available for them in Poland (Grabowska, 2003).

Pull factors that led to Ireland becoming a popular destination for Poles who were willing to migrate are largely due to the fact that Ireland was one of the few countries to allow immediate access to its labour market after Poland’s EU accession. Immigrants are well aware of their rights as European citizens, and legal status is certainly a key aspect (MCA, 2010b). In a survey conducted before accession, Polish people indicated a high willingness to migrate to Western European countries for work, but Ireland did not feature significantly as a destination country (Grabowska, 2003). Ireland’s decision to open its labour market must therefore be considered as a decisive factor. A further important pull factor was the favourable economic climate in Ireland with relatively high wages and easy availability of work, as well as the better conditions within workplaces, although the latter seemed to primarily emerge as a reason for staying rather than moving in the first place (Grabowska, 2003). English language is a further factor in favour of Ireland as a destination, as it is widely taught in Poland, and many migrants see spending time in Ireland as an opportunity to improve their level of English as well as gaining other occupational skills (Kropiwiec, 2006). Whilst Polish immigrants are largely Catholic, which may attract them to a majority Catholic country like Ireland, this was not cited as a motivation by immigrants who were interviewed by Kropiwiec (2006). Bushin (2009) also notes that the small population, environment and friendliness of Irish people attracted them to Ireland, and that quality of life was an important concern. Also, social networks with friends and family who have already migrated are important, as many immigrants needed immediate access to a job (Kropiwiec, 2006). These networks are relatively new, due to the recent nature of migration, but developed rapidly after accession. The importance of these factors is likely to shift over time, with economic motives potentially becoming less important for decisions to stay than other concerns.

Quality of life

Another aspect of Ireland that attracted migrants to Ireland was for the quality of life. Two out of the fifteen respondents agreed that the quality of life in Ireland is a lot better than in their country of origin. Apart from excellent working conditions, they felt that the people of Ireland were a lot friendlier than those in their country of origin. Mentally and physically, they felt a lot more content in Ireland in comparison to other countries they’ve lived in.

Conclusion:

From the research carried out on this topic, a conclusion can be drawn that small towns in Ireland are on the way to becoming multicultural and integrated. Through the introduction of more training programmes for new migrants, this will increase their chances of finding a job that matches their qualifications immediately. Furthermore, it is evident that the Celtic Tiger wasn’t the only reason that migrants were attracted to Ireland. They were attracted to Ireland because of a wealth of opportunities both socially and economically, as discussed previously. It is recommended that Irish society introduces new training programmes in the education sector that are particularly aimed at new migrants that will aim to improve the standard of their qualifications. Using education to help societies become more multicultural is vital if Ireland wishes to keep their migrant population.

Bibliography

Argaiz and King (2017). Integration, migration, and recession in post-Celtic Tiger Ireland: Irish Studies Review: Vol 24, No 1. [online] Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09670882.2015.1113002 [Accessed 18 Apr. 2017].

Barrett, A. and Duffy, D. (2008). Are Ireland’s Immigrants Integrating into Its Labor Market?. International Migration Review, 42(3), pp.597-619.Boyle, P., Halfacree, K., and Robinson, V. (1998). Exploring Contemporary Migration. Longman, New York

Bushin, Naomi. 2009. “From central and Eastern Europe to Ireland: Children‟s experiences of migration” in Ní Laoire, Caitríona, Naomi Bushin, Fina Carpena-Méndes and Allen White, Tell Me About Yourself: Migrant Children’s Experiences of Moving To and Living In Ireland. Cork:University College Cork

Cagiano de Azevedo, R., & Sannino, B., (2004). Measurement and indicators of integration.

Italy: Council of Europe Publishing.

Castles S, Korac M, Vasta E, et al. (2002) Integration: Mapping the Field. London: Home Office , as cited in European migrants in Ireland: Pathways to integration, Gilmartin. M., Migge.B. (2015) European Urban and Regional Studies, 22 (3) , pp. 285-299

Curry, P., Gilligan, R., & McGrath, J., (2010). Where to from Here? Inter-ethnic Relations among children in Ireland. Dublin: Liffey Press in association with the Children’s Research Centre, Trinity College Dublin.

Fanning, Bryan (2015) in Immigration, the Celtic Tiger and economic crisis pp9-20

Golledge, R. and Stimson, R. (1997). Spatial behavior. 1st ed. London: Guilford Press, pp.424-425.

Grabowska, Izabela. 2003. Irish Labour Migration of Polish Nationals: Economic, Social and Political Aspects in the Light of the EU enlargement. Institute for Social Studies Warsaz University.

Krings, Torben. 2010. “The impact of the economic crisis on migrants and migration policy: Ireland”in Migration and the Economic Crisis: Implications for Policy in the European Union. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

Kropiwiec, Katarzyna. 2006. Polish Migrant Workers in Ireland. Dublin: NCCRI

Kuhlman, T. (1991) ‘The Economic Integration of Refugees in Developing Countries : A Research Model’,Journal of Reficgee Studies 4: 1-20

MCA. 2008. MCA Newsletter No.1 Migration and Recession. Dublin: Trinity Immigration Initiative/Employment Research Centre, December 2008.

Murphy, C. (2015). Interculturalism and Immigration Reform? Integration Policy in Ireland – Human Rights in Ireland. Available: http://humanrights.ie/international-lawinternational-human-rights/interculturalism-and-immigration-reform-integration-policy-in-ireland/. Last accessed 28th Oct 2016.

Safi, M. (2010) in McGinnity, F. and Gijsberts, M. (2016). A threat in the air? Perceptions of group discrimination in the first years after migration: Comparing Polish Migrants in Germany, the Netherlands, the UK and Ireland. Ethnicities, 16(2), pp.1-2.

Share, P., Tovey, H., & Corcoran, M., (2007). A Sociology of Ireland (3rd ed.). Dublin: Gill & Macmillan Ltd.

Tyrell, N . (2013). ‘Of course I’m not Irish’: Young people in migrant worker families in Ireland. In: Crowley. C, and Linehan, D. Spacing Ireland: Place, Society and Culture in a Post-Boom era . Ireland : Manchester University Press (Irish Society) . p39-40.

www.communicraft.com, C. (2017). Third Age Homepage. [online] Third Age Ireland. Available at: http://thirdageireland.ie [Accessed 22 Apr. 2017].

www.CSO.ie Last accessed 29th Oct 2016

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Immigration"

Immigration is the act of someone travelling or moving to a country they are not a citizen of to live on a permanent basis. Someone that has gone through the process of immigration is defined as an immigrant.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: