Supporting Social Communication and Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties (Sebd) in Primary School

Info: 8561 words (34 pages) Dissertation

Published: 26th Jan 2022

WHAT IS THE MOST EFFECTIVE STRATEGY FOR SUPPORTING SOCIAL COMMUNICATION AND EMOTIONAL AND BEHAVIOURAL DIFFICULTIES (SEBD) FOR A CHILD IN MAINSTREAM PRIMARY SCHOOL

Abstract

The research explored strategies that best supported children who struggled with challenging behaviour and social communication in school. The research aimed to find a way for the child to more easily cope with the day to day struggles and anxieties of a mainstream classroom. How the child communicated and integrated with their peers and adults in the school was explored. The methods used for collecting data were, interviews and question prompts with 2 teaching assistants (TA’s) that support the child on a one to one basis answered.

Chapter One - Introduction Checklist

Social communication and Social Emotional and Behavioural difficulties (SEBD) is a widespread problem in schools today. The child may lack the social skills needed to form friendships with their peers. This may lead to frustration and be displayed as challenging behaviour. However, in this study, the links between deficits in social communication and the triggers to the challenging behaviour with that of an Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are too strong to separate.

Deficits in social functioning have been found to be a significant feature ASD (Myles et al., 2005; Rogers, 2000). The difficulties for children with this type of disorder are widespread and can range from, difficulties with sleep patterns, integration, creating, sustaining relationships and anxiety.

Children with these types of difficulties, are often assigned a teaching assistant (TA) in school to support them on a one-to-one basis. The TAs role in supporting the teacher with supporting positive behaviour plays a significant role in the classroom. The TAs role has become more significant since the green paper, Excellence for All Children (EfAC) (DfEE, 1997) announced policy interventions to support the development of inclusion for pupils with special educational needs (SEN), with specific importance highlighting the inclusion of pupils with social, emotional, and behavioural difficulties (SEBD).

Therefore, to accomplish this, EfAC (1997) states that more training is needed for teachers to enhance their knowledge of SEBD. Also suggested, is that schools and outside agencies should work in collaboration to develop plans to support behaviour. Failure to provide adequate teaching for these children can result in under achievement. If children with SEBD do not get the support they need, they cannot make a valued economic contribution in later life.

This research will identify factors contributing to effective practice by TAs, in supporting the inclusion of children who lack social skills and display challenging behaviour in my setting. Furthermore, the research aims to find a way for the a specific, identified child to manage more easily with their day to day struggles in the classroom. Integration with their peers will be examined along with strategies for coping with anxiety. The study will cover the subject of inclusive practice regarding children with special educational needs (SEN).

The research intends to inform and thus support the school staff in understanding effective supportive strategies in school regarding challenging behaviour, social communication, and autism. Also, TA’s will be welcome to use the strategies of support for other children in the school that already have diagnosis of social, emotional, and behavioural difficulties if (SEBD) or Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) If so desired. The benefits to myself as the researcher will be an integral part of my continuing professional development and future learning.

This case study will be conducted in a mainstream primary school. The school has two hundred and sixty children aged from 4 years to 9 years, with a range of diverse backgrounds. There are currently twenty-five TA’s across the school and twelve teachers. Over half the children on role have some sort of special educational need. The school is an inclusive mainstream school and does not yet have an autism base, but plans are to have one introduced at a later stage.

My role within the school is a teaching assistant in a year 1 classroom. I have worked in this setting for 7 years and on occasion have been able to support children with special needs. The school is in an urban area, which has previously been identified as a widespread child poverty area.

In a report by Ofsted (2015) they specified that in areas of Wychavon, the levels of child poverty varied widely. Pockets of deprivation (in the area this school sits in), attributed to Wychavon being placed in the top 30% of the most deprived areas nationwide.

The participants in this study include a year one child who struggles in the areas of challenging behaviour and social communication. The child, has also been seen by the Umbrella team, a term used to describe the various multi-agencies, and been assessed by the child phycologist at school. The School is currently awaiting an imminent diagnosis, which is expected to return a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.

There will also be two TA’s that work with the child on a one-to-one rota. One of the TA’s has worked with the child for two years. The child joined the school in reception class, having previously attended a nursery within a special school due to his autistic traits.

My intentions are to:

1. Critically examined literature regarding behavioural support strategies for the improvement of social skills with peers and others for special educational needs (SENs).

2. Through qualitative enquiry, investigate the efficacy of specific strategies employed by TA’s to support behaviour.

3. From analysis suggest changes in support for children with specific educational needs.

The role of the TA has changed since the days of ‘an extra pair of hands’ in the classroom. TAs now have a more professional standing in their job role. This is down to a range of accredited training initiatives and qualifications offered by most colleges and higher education facilities (Teacher Training Agency, 2003).

Clarke, et al, (1999) suggested that TAs were key to being able to effectively manage children with Special Educational Needs (SENs) in a mainstream classroom. However, Clarke noted, that many teachers had not had training on how to deploy TAs effectively, TAs could be costly and pointless if they are deployed in an inappropriate way. framework for a positive endorsement for inclusion.

Social, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties (SEBD)

The definition of SEBD is a much-discussed subject. The Department for Education (DfE), prefers to use the abbreviation BESD, however, the Social, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties Association (SEBDA) argues that social and emotional difficulties commonly escalate the behaviour, and therefore the words social and emotional should come first in the acronym (Cole 2006). We can also argue that placing the word ‘behaviour’ first concentrates attention on the challenge of the behaviour, and therefore detracts from the emotions behind that behaviour (Cole & Knowles, 2011). Therefore, for the purpose of this study I will continue to use the term SEBD.

Practitioners sympathise, that the understanding of the definition of remains unclear (SEED, 2001; Thomas 2005; Head, 2005;). Seed (2001) argues that this lack of understanding of SEBD is explained by an unavoidable discrepancy in viewpoints, owing to the pure intricacies of the difficulties.

Broomhead (2014) concurs with Seed (2001) and, argues that SEBD is misinterpreted as this is thought of as an inaccurate term. There is a need for a world-wide characterisation for SEBD to be fully accepted and understood (Bennett, 2007; Thomas, 2005; Visser, 2003).

Previous research (Thomas, 2005; Shuttleworth,2005; Crawford and Simonoff, 2003), has raised concerns regarding, practitioner’s roles when working with children that had SEBD. When consulting a guide to the care of children with SEBD, it was found that the support the educational practitioners gave was considered as simply nurturing the children. However, the educational practitioners were supporting social and emotional needs in conjunction with educating the children (Broomhead, 2014).

Based on this, practitioner knowledge of SEBD, needs to be improved, with the correct training. There is also a strong suggestion that partnerships between mainstream and special schools should be forged (Broomhead, 2014).

However, Sutherland and Oswald (2005) define that, social, environmental, and biological factors influence each other, to form associated limitations, where difficulties in one area can cause or support complications in another. Cross (2005) confirms this, stating that it is likely to be the case that children with SEBD have more communication difficulties than their peers who have no needs or social difficulties.

Therefore, the collective opinion on the term SEBD, is that there is none or diminutive clarity in its definition (SEED, 2001; Thomas 2005; Head, 2005; Broomhead, 2014).

It has been shown that when teachers are sympathetic and demonstration emotional warmth toward the child it raises the child’s emotional well-being and can influence academic attainment (Buyse et,al, 2008).

Forness et,al, (2012) suggests that interventions for behavioural issues can be beneficial to the whole school and are easily implemented.

As suggested by the Elton report (1989) assessments of support for the children with SEBD should commence within a timeline of six months. The report also cautioned that failure to put the support in place would contribute to the challenging behaviour of the child.

In the Steer report (2005), the prime concern was not for the severe occurrences of violence by children against teachers, but for the increasing episodes of commotion created through minor but incessant misconduct by children with challenging behaviour. This leads to the learning of the other children in the classroom being disrupted. As Desforges (1995) reasoned, teachers must decide as to whether to intervene in the disruption or not. This must be handled sensitively if the child has SEBD, as the incident could manifest into a meltdown for the child. Time spent intervening and controlling these minor disruptions is precious time away from teaching (Goodman and Burton 2010).

In a paper by Evans et. al, (2014) strategies have been proposed to support teachers and TA’s to control and calm disruptive children, including those with SEBD. The study that Evans conducted looked at four types of behaviour, being off-task, being disruptive, being aggressive, and difficulties with social behaviour. These four types of behaviour are comparable to the behaviour displayed by the child in this study.

Evans et, al, (2014) confirmed that, the intervention strategies were conducted by trained teachers, although, the need for support from a TA or other support staff was evident. This again challenges the ability of teachers being able to effectively support children with SEBD, as well as the time spent out of whole class teaching, to achieve the intervention goals.

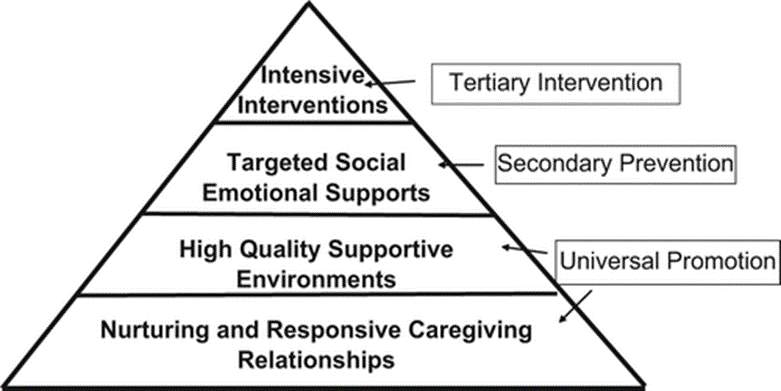

In a study by Hemmeter et, al, (2011) a framework was presented, ‘The Teaching Pyramid Model, (see Figure 1), for promoting SEBD (Fox et, al, 2010). This is a summary of The Teaching Pyramid, the model is described in more detail by (Fox et al, 2003). The framework has four levels intended to encourage the social and emotional development of children, including those with insistent challenging behaviour (Fox, et al, 2010; Hemmeter,et, al, 2006).

The pyramid suggests universal strategies for all children who struggle, secondary strategies focus on social skills and emotional capabilities for children who require more focused teaching, and tertiary strategies for children whose behaviours are constant when the even when all levels have been put in place.

Thus, Fox (2010) suggests: creating a classroom conducive for learning, organising routines so the children know what to do and what is expected of them, implementing strategies with clear directions, and giving positive feedback to the children. Secondary strategies focus on intentionally teaching social skills and promoting emotional competence (Kaiser & Rasminsky, 2007).

Kaiser & Rasminsky (2007), argue that the key to preventing challenging behaviour is engagement. Challenging behaviour is less likley to present itself if the child is involved in an activity they enjoy. Universal strategies build upon positive relations with the children and caregivers (Bowman, Donovan, & Burns Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000).

Response to Intervention (RtI) (Fox et al 2010) is a methodical process used to aid decision making. Rtl has been used as a problem-solving framework in measuring the efficacy of evidence-based interventions. RtI has parallels to the “Pyramid Model” (Fox, et al 2003) for encouraging the development of social, emotional, and the acceptable behaviour of children. The pyramid model complements the use of Rtl in the problem-solving process, and helps to address the challenging behaviour.

Circle time (CT) a widely used intervention to support social and emotional learning in schools. CT, is a child-centred approach to encourage, develop, and practice social and emotional skills including, listening, communicating, respect and problem solving, within a safe non-judgemental and inclusive environment (Mosley 2009).

Mosley (2009) also states that circle time can enable the growth of empathy and, as Labour Government’s Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) policy highlighted, by encouraging children to participate, symptoms of SEBD may significantly lessen over time.

Mary (2014) stated that from the children’s voice, that CT had enabled them to have positive relationships with peers. Children started that CT had facilitated their ability to become friendly with the shy children in the class.

The only negative I have found, is that the children in my setting that lack social confidence don’t like to get involved with the conversations and just like to sit and watch.

Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is a life-long developmental disorder, it is characterised by lack of social interaction, communication, and behavioural difficulties (Dillenburger et, al. 2015). Autism affects about 1.1% of the population.

Autism is not fickle, it presents itself in all races, and classes of people globally. It is a spectrum disorder meaning that it is greatly complex and effects on people are varying and to variable degrees. Autism is generally defined as a triad of impairments, social communication, social interaction, and social imagination. (Cashin & Barker, 2009; Autism, H.F., 2011).

The triad of impairments:

- Impaired communication can be a broad area. Children can be verbal or non-verbal as a minor number of children have no verbal language at all (Nacewicz, Dalton, Johnstone, Long, & al., 2006). Children can also have echolalia, the repetition of another person’s spoken words (Depape, Chen, Hall, & Trainor, 2012). Children can also take the meaning of words literally (Cashin & Barker, 2009).

- Impaired social skills and difficulties are clearly interconnected with communication, children with ASD are not only monotone themselves, but struggle to comprehend different pitch in others language (Depape, et al., 2012). Children with ASD also struggled to match emotions on pictures of faces with a description of the emotions (Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Hill, Raste, & Plumb, 2001)

- Repetitive behaviours. As Cashin and Barker (2009,) note a common trait that children with ASD do not like change and prefer constant routine. Changes can cause high anxiety for some children, with other children not being concerned with the change if they have been prepared. The children often have the characteristics such as, rocking, flapping other children with ASD develop new obsessions such as popular TV characters or certain book characters (Shattuck et al., 2007).

Friedlander (2009) suggested, that in order to flourish, all children including those with ASD need to be in an ordered classroom and be regulated by a consistent schedule. Therefore, visual timetables should be favoured by the teacher and regularly updated times for targets, also, coloured binders may be beneficial to children with reading difficulties.

There is various literature suggesting the efficacy of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) (Jensen and Sinclair, 2002; Johnson et al. 2007) for children with ASD. ABA, as explained by Jensen and Sinclair (2002) is being able to apply what is learned from examining the behavior, in order to recognise why the behaviour occurs in the situation. Interventions can then be put in place to change/alter the behaviour, so that the same situation does not repeat.

Evidence of positive outcomes have been shown by Harris et al, (2000); Department of Health Early Intervention Program (1999); Luiselli (2000). The outcomes proved to be most successful for children with ASD and behavioural difficulties when, the interventions are thoroughly supported, differentiation for each child has been applied and targeted behaviour plans are put in place.

Pedagogic and Inclusive practice

How an organisation is controlled effects how inclusion is understood, the affects reflect on the physical, social, and psychological integration (Pijl and Meijer, 1991).

Several studies (Vislie, 1995; Sugden, 1996; Dyson and Millward, 1997; Meijer et al., 1997) have shown that inclusive education and social integration involves meeting the needs of all children whether they have special needs or are quite able to cope without the need for extra support.

In a small-scale study conducted by Goodman and Burton (2010) the challenges to effective inclusion were pointed out by teachers, these included an overall lack of resources and level of proficiency.

In Flem and Keller’s (2000) study of inclusive practice, they agreed with a previous comment by Fox, (2010), that enabling the classroom was of a major importance to promote the efficacy of all the children’s learning.

Pedagogical effectiveness, was reviewed by Lewis and Norwich (2005), they scrutinised varying methods of inclusion in mainstream schools. Lewis and Norwich found that the notion of differentiation for children with SEBD and ASD was indeed lacking.

If children need specific pedagogical modifications, Vygotsky’s (1929/1994) recommendation was to enhance staff mindfulness of these identified children, their assets, weaknesses and how they accessed the syllabus. Norwich and Lewis’ review proved to be, of key standing for children with BESD and ASD.

Dyson et, al, (2004) suggested that relationship-learning and nurturing is significant and should be encouraged, with teacher-children associations being a part of teaching that contributed to the child’s increase in self-esteem and well-being.

Nurture groups, where started in London in 1969 by Marjorie Boxall in a bid to settle and stabilise a child’s behaviour within mainstream schools. The group may have up to ten children with a range of diverse needs. The groups nurturing approach has had positive outcomes for children with SEBD and enables the child to regain the missed building blocks of early childhood, that SEBD may have taken from them (Bennathan and Boxall, 2002).

Relationships between ASD and SEBD

Research has shown that a substantial number of children with ASD have some form of expressive or social skills discrepancies (Mitchell et al. 2006; Carr & Durand 1985). Children with ASD may use problem behaviour to express their selves. Behaviour may include self-injury, being aggressive to peers or just plain tantrums (Prizant & Wetherby 2005). It was suggested by (Reese et al. (2005) that poor expressive communication, a lack of social and emotional skills and inappropriate behaviour are linked with the cognitive development of children with ASD (Murphy et al. 2005). A substantial number of children with ASD have less than the basic spoken language to be able to verbally communicate at an elementary level, with an estimated 19% to 59% of children with ASD who do not verbalise at all (Fombonne 1999; National Research Council, 2001).

Estimation for the frequency of SEBDs in children with ASD are suggested to be higher than those for the children without ASD. However, the reasons for this assumption are not clear (Robertson, Chamberlain, & Kasari, 2003; Zingerevich & LaVesser, 2009). Consequently, more evidence based research is needed into why SEBDs are more frequently detected in children with ASD. Therefore, guidelines would be advantageous to school staff who are delegated to develop diverse assessment based agendas (Simpson, et al, (2011).

Again, as in EfAC (1997), argument arises as to whether mainstream teachers are sufficiently knowledgeable to develop, teach and appraise programs or strategies for children with ASD and SEBD (Gilmour, 2010; Nosek, 2011).

However, O’Brien (1998) argues that teachers are better trained in classroom management, and voiced his fears that, TAs are being incorrectly deployed in the educational supervision of children with SEBD and ASD. O’Brien questions that TAs should be proactive and have the right amount of training to effectively deal with challenging behaviour.

Proactive strategies as described by Handbury (2007), are based on a study of the child’s needs and should enhance their life chances. The interventions must be designed to anticipate the manifestation of an episode of challenging behaviour. For a child with ASD proactive strategies will bring about a change in behaviour, not knowing if the results will be positive or negative.

This section has attempted to provide a, brief summary of the literature relating to strategies and boundaries for children with SEBD and ASD in regard to communication and behaviour. It has been shown that there is an abundance of strategies, for effectively supporting children with SEBD and ASD with their challenging behaviour.

What is a case study?

A case study as described by Cohen et al, (2011) is a detailed occurrence that is observed to show a more general perspective. Case studies can help us to explain cause and effect to many situations (Cohen et al, 2011). Also, a case study can be regarded as a comprehensive study of interactions of real people in real situations, as is the bearing on this research (Opie, 2005). According to Grinnell (1981) a case study is a very flexible and open-ended method of data collection and analysis.

Structured interviews

Structured interviews have a set of predetermined questions that can be quickly asked and then are able to be coded. As the questions are set, there is very little in the way of expanding the responses. The interview questions might just as well be sent out as a questionnaire (Robson, and McCartan, 2016).

This method was not chosen as coding the data was not necessary with only a small sample of participants.

Unstructured interviews

As the name suggests there is no format for this type of interview, it is more like having a conversation. The interviewee sets the agender and leads the way. They may talk at length about the research subject, however, there is room to go off topic. You may need to prompt the interviewee occasionally although, this should be done without taking over the interview and leading the agenda (Thomas, 2017).

Although unstructured interviews can offer a wide range of information on the subject offered. As the research was in my setting, I had to conduct an ethical interview, without the concern of the interviewee going off theme. For this reason, this method of interview was rejected.

Semi-structured interviews

A semi-structured interview is guided by a set of themes or issues that are to be covered, rather than a set of questions to be answered. It is considered the most advantageous and for this reason it is the most commonly used for interviews in social research where the sample is very small (Thomas, 2016).

Oppenheim (1992) states that the researcher conducting the interview and only gently probe the respondent when necessary to give an impression of authority and to build the respondents confidence. Giving the respondent confidence, will encourage more in-depth answers (Oppenheim, 1992).

Interviews however, do have some limitations such as, if you give the wrong body language, the respondent may shut down, lack of mutual trust, and the connotations of words (Woods, 1986 cited in Cohen et al. 2000).

Methods

The main aim of the research along with the methods are explained here along with the reasons for adopting the approach outlined. A description of the participants in the study, a summary of the methods of data collection, an explanation of how the data was analysed, an outline of the ethical procedures in accordance with which the study was conducted and a discussion of the limitations of the study.

The aim of the research was to gather strategies for the TAs, regarding effective support in the areas of social, emotional, communication needs and strategies to encourage positive behaviour.

A case study design was chosen for this project, as the number of participants was so small. Also, I felt an empathic neutrality approach was needed as I personally knew the participants involved in the study.

Patton (2002) suggested that participants should be carefully chosen, with preference put on those who can give the most relevant and reliable information of the chosen study.

Therefore, when choosing the participants, I selected two TAs that work with the child daily. The reasoning behind this, is the fact that one of the TAs has worked with the child for two years so understood him very well. I believed her knowledge of the child would be very reliable.

Wellington (2000) states his definition of validity as ‘the degree to which a method or a research tool truly measures what it is supposed to measure’ (Wellington, 2000).

The research carried out in this study was of a qualitative nature. Therefore, the method of data collection decided upon for this study were semi-structured interviews, with prompts in the form of questions. Semi-structured interviews, for qualitative data collection were used in studies I digested before commencing the research. The results shown in these studies suggested that semi-structured interviews were plausible for this type of case study.

I reviewed similar titles to ‘What is the most effective strategy for supporting social communication, emotions and challenging behaviour for an undiagnosed child in a mainstream primary school’, for the purpose of examining the methods used for the data collection. I found numerous case studies (Flem,et al,. 2004; Samsel, and Perepa, 2013; Nilholm, et al,2010; Goodman & Burton, 2010; Nilholm et al, 2010) that had used Semi-structured interviews with questionnaire prompts.

Ethics

Who will benefit from it?

What right does the researcher have to undertake the research?

What responsibilities arise from the privileges the researcher has as a result of their professional role?

Will involvement in the research raise unrealistic expectations on the part of the participants that ‘things will improve’?

Can the researcher deliver the outcomes of the research, or if support is required, where will it come from?

Chapter Structure:

The role and purpose of practitioner research

(How) can the research be used as a vehicle for change or improvement?

Identification of methods for collecting data and samples – how has the sample been chosen?

What sampling method was/will be used?

Key issues that must be considered and applied

Criteria Chapter Four Data Analysis Checklist

Approximate word count 1,500 words or equivalent (e.g. graphs, diagrams)

Data presented in a readable format

Data analysis and interpretation:

- What does the data tell the researcher?

Identification of different dimensions of the data. E.g.:

- Differences

- Similarities

- Links/connections

Clear identification of data. E.g. re-stating the question that generated the data, number of people who responded, if appropriate, categories of the respondents

Appropriate use of graphs, diagrams:

- clearly presented and labelled

- informative

- accompanied by a key

- no unnecessary/inappropriate graphs e.g. yes/no answers for a single group, repetitive data

- give each graph/diagram a figure number (fig. no.)

- avoid lurid/over ambitious graphs

- explain all the material included e.g. label photographs, explain value and purpose pupils work

- maintain anonymity of respondents, places

Qualitative data could be presented:

- in a bulleted pointed format in a box

- in continuous prose with key points highlighted in a box at the end

- continuous prose

- avoid overlong quotes from interviews – précis/select key points and, if necessary add an appendix

Other considerations:

- Synthesise findings from research at appropriate points in the chapter e.g. after the interview/questionnaire/observation data. This allows evaluation of different aspects of the research and helps identify themes, links, comparisons, contrasts in the range of findings

Criteria Chapter Five Evaluation Checklist

Approximate word count 2,000 words 1000

The role of the researcher:

- The extent to which the research objectives have been achieved

- Provision of evidence that they have been achieved

- If not achieved, why?

The research and the quality of the data:

- The extent to which the methods used were appropriate

- The extent to which they provided the data hoped for

- Were ethical issues adhered to?

- Was the model (e.g. action research) of research appropriate for the study?

- Were the right questions asked?

- Was sufficient research undertaken? E.g. a sufficient number of observations, an appropriate range of interviewees?

- What might be done differently and why

Micro-political implications of the research. The impact of the implications, if adopted, for:

- Colleagues?

- Line managers?

Provide evidence to substantiate impact

What has been learned from the research?

- New information?

- Confirmation of previous thoughts?

- The extent to which the outcomes impact upon / can be used to improve own practice

- Impact on own professional development

- Impact upon research participants

- How might the research be used to improve organisational practice / implement change

- Practicality of application of findings?

- Who would need to be informed?

- Resource implications

- Potential barriers

The literature has suggested, that to effectively enable the learning of children with SEBD and ASD specific training is needed. Also, suggestion has been made that there are limitations with regard to the experience of those staff that aid the support of these children.

The research in the wider context

- Reflection upon the implications of the research in other contexts e.g. other educational settings, key stages

- Consideration of present / possible future political direction / change

Literature

- Reference to literature in chapter two may be relevant

- Exploration of literature relating to organizational change, leadership, school improvements etc. may provide relevant underpinning

Recommendations for future practice with justification

- Individual, Students, Setting, Wider-scale, Action plan and time-scale

List of References

Appendices

Appendix 1 Questionnaire

Appendix 2 Interviews

Appendix 3 Data Tables

1 May

Annlaug Flem & Clayton Keller (2000) Inclusion in Norway: a study of ideology in practice, European Journal of Special Needs Education, 15:2, 188-205, DOI: 10.1080/088562500361619

Autism, H.F., 2011. What is autism?. Training, 121(450), p.7576. https://scholar.google.co.uk/

Bowlby, J. 2005, The making and breaking of affectional bonds, Routledge, New York;London;hu7

Bowlby, J., 1970. Attachment and Loss. Volume 1: Attachment. International Psycho-analytic Library.

Bowman B. T., Donovan M. S., Burns M. S. (2001). Eager to learn: Educating our preschoolers. Washington, DC: National Academy Press

Buyse, M. 2008, “Reformulating the hazard ratio to enhance communication with clinical investigators”, Clinical Trials, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 641-642.

Carr E. G. & Durand V. (1985) Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 18, 111–26.

Cole, T & Knowles, B, 2011, How to Help Children and Young People with Complex Behavioural Difficulties, London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Cole, T, 2006, Appendix 1 from SEBDA (Social, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties Association) 2006 Business Plan [online]. Available from: www.sebda.org/resources/articles/DefiningSEBD.pdf [accessed 29 July 2010]

Created from worcester on 2017-06-03 02:46:46.

Cross, M. 2004. Children with emotional and behavioural difficulties and communication difficulties – There’s always a reason, London: Jessica Kingsley

Department for Education and Skills (DfES). 1989. The Elton report: Enquiry into discipline in schools, London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Desforges, C. 1995. “Teaching for order and control”. In An introduction to teaching, Edited by: Desforges, C. Oxford: Blackwell.

DfEE (1997b) Excellence for All Children. London: Department for Education and Employment.

Dillenburger, K., McKerr, L., Jordan, J.A., Devine, P. & Keenan, M. 2015, “Creating an Inclusive Society… How Close are We in Relation to Autism Spectrum Disorder? A General Population Survey”, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, vol. 28, no. 4, (Online) pp. 330-340.

DYSON, A. and MILLWARD, A. (1997). ‘The reform of special education or the transformation of mainstream schools?’ In: PIJL, S. J., MEIJER, C. J. W. and HEGARTY, S. (Eds) Inclusive Education: A Global Agenda. London: Routledge, pp. 51–67.

Dyson, A., Howes, A. & Roberts, B. (2002) ‘A systematic review of the effectiveness of school-level actions for promoting participation by all students (EPPI-Centre review, version 1.1).’Research Evidence in Education Library. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education.

Ekins and Grimes’ (2009) recent work in schools suggests that BESD children do feature highly in schools’ inclusion agendas, as ‘challenging behaviour’ was one of three areas of focus commonly referred to by schools when talking about inclusion.

Fox, L., Dunlap, G., Hemmeter, M. L., Joseph, G., & Strain, P. (2003). The Teaching Pyramid: A model for supporting social competence and preventing challenging behavior in young children. Young Children, 58(4), 48 -53.

Flem, A and Keller, C. (2000). Inclusion in Norway: a study of ideology in practice. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 15(2): 188–205).

Fombonne E. (1999) The epidemiology of autism: a review. Psychological Medicine 29, 769–86

Forness, S.R., Kim, J. & Walker, H.M. 2012, Prevalence of Students with EBD: Impact on General Education, Council for Children with Behavioral Disorders.

Fox L., Carta J., Strain P. S., Dunlap G., Hemmeter M. L. (2010). Response to intervention and the Pyramid model. Infants & Young Children, 23, 3-13

Frederickson, N., Jones, A.P., Warren, L., Deakes, T. & Allen, G. 2013, “Can developmental cognitive neuroscience inform intervention for social, emotional and behavioural difficulties (SEBD)?”, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 135-154.

Frydenberg, E., Deans, J. & O’Brien, K. 2012, Developing everyday coping skills in the early years: proactive strategies for supporting social and emotional development, Continuum, London.

Gilmour, N. M. (2010). Perceptions of school psychologists regarding behavioral interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders and co-occurring emotional and behavioral disorders. Unpublished master’s thesis, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY.

Goodman, R.L. & Burton, D.M. 2010, “The inclusion of students with BESD in mainstream schools: teachers’ experiences of and recommendations for creating a successful inclusive environment”, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 223-237.

HEAD, G. (2005) Better Learning – Better Behaviour. Scottish Educational Review, 37, 2, 94–103.

Hemmeter M. L., Ostrosky M. M., Fox L. (2006). Social and emotional foundations for early learning: A conceptual model for intervention. School Psychology Review, 35, 583-601.

Hemmeter, M.L., Ostrosky, M.M. & Corso, R.M. 2012;2011;, “Preventing and Addressing Challenging Behavior: Common Questions and Practical Strategies”, Young Exceptional Children, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 32-46.

Kaiser B., Rasminsky J. S. (2007). Challenging behavior in young children: Understanding, preventing and responding effectively. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Lewis, A. & Norwich, B. (2005) Special Teaching for Special Children? Pedagogies for Inclusion. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Mainstream inclusion, special challenges: strategies for children with BESD – full report

MEIJER, C. J. W., PIJL, S. J. and HEGARTY, S. (1997b). ‘Inclusion: implementation and approaches’. In: PIJL, S. J., MEIJER, C. J. W. and HEGARTY, S. (Eds) Inclusive Education: A Global Agenda. London: Routledge, pp. 150–161.

Mitchell S., Brian J., Zwaigenbaum L., Roberts W., Szatmari P., Smith I., et al (2006) Early language and communication development of infants later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 27, S69–S78.

Murphy G. H., Beadle-Brown J., Wing L., Gould J., Shah A. & Holmes N. (2005) Chronicity of challenging behaviours in people with severe intellectual disabilities and/or autism: a total population sample. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 35, 405–18.

Myles, B.S., Adreon, D.A., Hagen, K., Holverstott, J., Hubbard, A., Smith, S.M., et al. (2005). Life journey through autism: An educator’s guide to Asperger syndrome. Arlington, VA: Organization for Autism Research.

National College for Teaching and Leadership

National Research Council (2001) Educating children with autism (Committee on Educational Interventions for Children with Autism, Division of Behavioral and Social Science and Education). National Academy Press: Washington, DC.

Nosek, K. (2011). School-based professionals’ self-reported training, perception, and confidence in providing services to students with ASD. Unpublished master’s thesis, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY.

PIJL, S. J. and MEIJER, C. J. W. (1991). ‘Does integration count for much? An analysis of the practices of integration in eight countries’, European Journal of Special Needs Education, 6, 2, 100–111

Prizant B. M. & Wetherby A. M. (2005) Critical issues in enhancing communication abilities for persons with autism spectrum disorders. In: Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders, (3rd edn. Vol. 2. Assessment, Interventions and Policy) (eds F. R.Volkmar, R.Paul, A.Klin & D.Cohen), pp. 925–45. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ.

Published:

Reese R. M., Richman D. M., Belmont J. M. & Morse P. (2005) Functional characteristics of disruptive behavior in developmentally disabled children with and without autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 35, 419–28.

Robertson, K., Chamberlain, B., & Kasari, C. (2003). General education teachers’ relationships with included students with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 33, 123–130. doi:0162-3257/03/0400-0123/0

Rogers, S. (2000). Interventions that facilitate socialization in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 399—409.

SEBDA – The Social, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties Association (Registered Charity 258 730: formerly AWCEBD) SEBDA, c/o Goldwyn School, Godinton Lane, Great Chart, Ashford, Kent, TN23 3BT. http://www.sebda.org/

Simpson, R. L., Mundschenk, N. A., & Heflin, L. J. (2011). Issues, policies, and Recommendations for improving the education of learners with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 22, 3–17. doi:10.1177/1044207310394850

Staats, Walter W.. Behavior and Personality : Psychological Behaviorism, Springer Publishing Company, 1996. ProQuest Ebook Central, .

Steer report, DfES 2005Department for Education and Skills (DfES). 2005. Learning behaviour: The report of the practitioners’ group on school behaviour and discipline, London: DfES.

SUGDEN, D. A. (1996). ‘Moving towards inclusion in the United Kingdom?’, Thalamus, 15, 2, 4–11

Sutherland, K.S. and Oswald, D.P., 2005. The relationship between teacher and student behavior in classrooms for students with emotional and behavioral disorders: Transactional processes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14(1), pp.1-14.

THOMAS, G. (2005) What do we mean by EBD? In P.Clough, P.Garner, J. T.Pardeck and F.Yuen (eds), Handbook of Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, pp. 59–82. London: Sage.

VISLIE, L. (1995). ‘Integration policies, school reforms and the organisation of schooling for handicapped pupils in Western societies’. In: CLARK, C., DYSON, A. and MILLWARD, A. (Eds) Towards Inclusive Schools? London: David Fulton, pp. 42–53.

Visser, J., Daniels, H. & Cole, T. 2012, Transforming troubled lives: strategies and interventions with children and young people with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bradford.

Vygotsky in Roth, W.M., 2013. An integrated theory of thinking and speaking that draws on Vygotsky and Bakhtin/Vološinov. Dialogic Pedagogy: An International Online Journal, 1.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1995). Problemy defectologii [Problems of defectology]. Moscow: Prosvecshenie Press.

Friedlander, D. 2009, “Sam Comes to School: Including Students with Autism in Your Classroom”, The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, vol. 82, no. 3, pp. 141-144.

Evans, J., Harden, A. and Thomas, J. (2004), What are effective strategies to support pupils with emotional and behavioural difficulties (EBD) in mainstream primary schools? Findings from a systematic review of research. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 4: 2–16. doi:10.1111/J.1471-3802.2004.00015.x

Gilmour, N. M. (2010). Perceptions of school psychologists regarding behavioral interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders and co-occurring emotional and behavioral disorders. Unpublished master’s thesis, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY.

Johnson, C. R., Handen, B. L., Butter, E., Wagner, A., Mulick, J., Sukhodolsky, D. G., (2007). Development of a parent training program for children with pervasive developmental disorders. Behavioral Interventions, 22, 201–221.

Jensen, V.K. & Sinclair, L.V. 2002, “Treatment of Autism in Young Children: Behavioral Intervention and Applied Behavior Analysis”, Infants & Young Children, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 42-52.

Groom, B. and Rose, R. (2005), Supporting the inclusion of pupils with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties in the primary school: the role of teaching assistants. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 5: 20–30. doi:10.1111/j.1471-3802.2005.00035.x

Morley, Dr. John. The Academic Phrasebank: an academic writing resource for students and researchers (Page 42). The University of Manchester I3 Limited. Kindle Edition.

Teacher Training Agency (2003) Professional Standards for Higher Level Teaching Assistants. London: Teacher Training Agency Publication.

O’Brien, T. (1998) Promoting Positive Behaviour. London: David Fulton. e,

Clarke, C., Dyson, A., Millward, A. & Robson, C. (1999) ‘Theories of inclusion. Theories of schools: deconstructing and reconstructing the inclusive school. British Educational Research Journal, 25 (2), pp. 157–77.

Reardon, D. 2006, Doing Your Undergraduate Project, 1st edn, Sage Publications Ltd, GB

Evans, J., Harden, A. and Thomas, J. (2004), What are effective strategies to support pupils with emotional and behavioural difficulties (EBD) in mainstream primary schools? Findings from a systematic review of research. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 4: 2–16. doi:10.1111/J.1471-3802.2004.00015.x

Kumar, R. 2011, Research methodology: a step-by-step guide for beginners, 3rd edn, SAGE Publications, London.

The seminal Elton report (DfES 1989 Department for Education and Skills (DfES). 1989. The Elton report: Enquiry into discipline in schools, London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office

” (Cicourel, 1964 and Woods, 1986 cited in Cohen et al.2000).

Goodman, R.L. & Burton, D.M. 2010, “The inclusion of students with BESD in mainstream schools: teachers’ experiences of and recommendations for creating a successful inclusive environment”, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 223-237.

Cefai, C., Ferrario, E., Cavioni, V., Carter, A. & Grech, T. 2014, “Circle time for social and emotional learning in primary school”, Pastoral Care in Education, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 116-130.

Robson, C. and McCartan, K. (2016) Real world research: a resource for users of social research methods in applied settings. Fourth Edition. Chichester, West Sussex, United Kingdom: Wiley.

Thomas, G. (2017) How to do your research project: a guide for students in education and applied social sciences. Third edition. Los Angeles: SAGE

Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2009.

Mary, L. 2014, “Fostering positive peer relations in the primary classroom through circle time and co-operative games”, Education 3-13, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 125-137.

Flem, A., Moen, T. & Gudmundsdottir, S. 2004, “Towards inclusive schools: a study of inclusive education in practice”, European Journal of Special Needs Education, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 85-98.

Samsel, M. and Perepa, P. (2013), The impact of media representation of disabilities on teachers’ perceptions. Support for Learning, 28: 138–145. doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.12036

Nilholm, C., Alm, B., HLK, Ä., HLK, C., Högskolan för lärande och kommunikation & Högskolan i Jönköping 2010, “An inclusive classroom? A case study of inclusiveness, teacher strategies, and children’s experiences”, European Journal of Special Needs Education, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 239-252.

Hulme, M. & Sangster, P. 2013, “Challenges of research(er) development in university schools of education: a Scottish case”, Journal of Further and Higher Education, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 181-200.

onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy.worc.ac.uk/

http://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy.worc.ac.uk/

Jackie Lown (2002) Circle Time: The perceptions of teachers and pupils, Educational Psychology in Practice, 18:2, 93-102, DOI: 10.1080/02667360220144539 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02667360220144539

Goodman, R.L. & Burton, D.M. 2010, “The inclusion of students with BESD in mainstream schools: teachers’ experiences of and recommendations for creating a successful inclusive environment”, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 223-237.

Nilholm, C., Alm, B., HLK, Ä., HLK, C., Högskolan för lärande och kommunikation & Högskolan i Jönköping 2010, “An inclusive classroom? A case study of inclusiveness, teacher strategies, and children’s experiences”, European Journal of Special Needs Education, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 239-252.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Children"

Dissertations looking at all aspects of children, their health and wellbeing, the impact of advances in technology on childhood and more.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: