Student Search and Seizure in K-12 Public Schools

Info: 42941 words (172 pages) Dissertation

Published: 21st Jan 2022

Tagged: EducationChildrenYoung People

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION

School administrators are responsible for providing a safe and orderly school environment that is conducive to learning. To provide this environment, administrators are sometimes required to address disruptive or unsafe behavior that is a violation of the law as well as school policy and may require the searching of students and their belongings. Dealing with inappropriate behavior or actions that are violations of school policy and the law create a complex situation that requires sound decision-making when deciding when, where and how to conduct a search and seizure. How does an individual maintain order while also serving as a guardian for large numbers of young people and not violating their constitutional rights?

In an effort to provide guidance and understanding of the case law governing search and seizure in public schools, legal research was conducted and is being presented in this document in a non-traditional format. It differs from the typical experimental dissertation because it follows the format used in previous legal research documents by providing a historical review of the relevant case law.

In Loco Parentis

School officials have and continue to operate under the doctrine of in loco parentis which means “in place of a parent.”3 Sir William Blackstone stated in his Commentaries:4

A parent may also delegate part of his parental authority, during his life, to the tutor or schoolmaster of his child; who is then in loco parentis, and has such a portion of the power of the parents viz. that of restraint and correction as may be necessary to answer the purposes for which he is employed.

Because of this doctrine, administrators had previously been afforded many of the same rights and privileges given to parents regarding safety, discipline, and the general care of children.5 In its early application, in loco parentis provided school officials with broad authority to discipline students. By applying the doctrine of in loco parentis to schools, the courts were able to avoid addressing the issue of students’ rights as stated in the Fourth Amendment:

The rights of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. (U.S. Const, Amend. IV.)

3 Kern Alexander M. David Alexander, American School Law, 309 (4th ed., West Publishing Company, 1998).

4 Sir William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, 441 (1769).

5 M. Teresa Harris, “New Jersey v. T.L.O.: New Standard of Review or New Label,” 163, Am. J. Trial Advoc. (1985).

However, recent trends in constitutional law have more clearly defined student rights, how they relate to schools, and narrowed the application of in loco parentis. Alexander and Alexander6states that the courts have never intended nor meant for the doctrine of in loco parentis to authorize school authorities or teachers to stand fully in place of parents in control of their children. School officials’ and teachers’ prerogatives are circumscribed by, and limited to school functions and activities. In Richardson v. Braham7, the court stated:

General education and control of pupils who attend public schools are in the hands of school boards, superintendents, principals, and teachers. This control extends to health, proper surroundings, necessary discipline, promotion of morality and other wholesome influences, while parental authority is temporarily superseded.

In Lander v. Seaver8, the Supreme Court of Vermont pointed out that the power of the teacher over a student is not coextensive with that of the parent.9 According to Mike Levin, Pennsylvania School Board Association attorney and legal counsel for several school districts, in Pennsylvania, “in loco parentisis limited to maintaining order”.10

When a student violates a school rule which is also a violation of the law, the student may be subject to two sanctions, one by the school and one by law enforcement officials. Actions usually taken by the school are intended to protect the school environment and educational program. An action taken by law enforcement officials is often done to address a violation that may be considered a criminal act. In both situations, violation of policy or law, the student is entitled to due process. Courts have consistently ruled that a student is entitled to due process when he/she may be subject to certain exclusions from school. A student has a right to a notice of the allegations and the right to a hearing (administrative) to hear evidence against him/her, and present their own evidence. In Goss v. Lopez11 the court stated that there are procedural processes and minimum requirements for notice and a hearing, specifically, 1) “students facing temporary suspension from a public school have property and liberty interests that qualify for protection under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment”,12 and

2) “due process requires, in connection with a suspension of 10 days or less, that the student be given oral or written notice of the charges against him and, if he denies them, an explanation of the evidence the authorities have and an opportunity to present his version. Generally, notice and hearing should precede the student’s removal from school, since the hearing may almost immediately follow the misconduct, but if prior notice and hearing are not feasible, as where the student’s presence endangers persons or property or threatens disruption of the academic process, thus justifying immediate removal from school, the necessary notice and hearing should follow as soon as practicable”.13 It is important to note that unlike being in court with very formal procedures, the administrative hearing is not a trial and may be conducted with a degree of informality. However, it must be conducted with fairness.

6 Alexander Alexander, 308.

7 Richardsonv. Braham, 249 N. W. 557 (Neb., 1933).

8 Landerv. Seaver, 32 Vt. 114 (1859).

9 Id.

10 Interview with Mike Levin, Levin Legal Group, PA (2005).

11 Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S, 565, 95 S. Ct., 729 (1975).

Student Rights

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Tinker v. Des Moines14that students have rights which are explicitly and implicitly guaranteed by the Constitution and school administrators must know what, when, and where it is appropriate and legal to search students and their property.The

Court declared that “students in school as well as out of school are ‘persons’ under the constitution”.15 The Tinker decision ushered in a new era, the “era of student rights”, which changed the previous judicial view that attendance at public schools is a privilege and not a right.16 Tinker also said that a denial of freedom of expression may be justified by a reasonable forecast of substantial disruption.17 Approximately twenty years later, two other U.S. Supreme Court cases brought clarification and balance to the new thinking.

Bethel School District v. Fraser 18 and Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier 19 balanced the legal standard back in favor of school officials. Fraser, a 17-year-old honor student gave a nominating speech on behalf of a classmate who was campaigning for vice president of the student government. School officials accused Fraser of using sexual innuendos and metaphors, and disciplined Fraser for giving a lewd and indecent speech that violated school policy.

12 Id. 735-737.

13 Id. 738-741.

14 Tinkerv. DesMoines Independent Community School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969).

15 Id. 511.

16 Kern Alexander M. David Alexander, American School Law,365 (Thomson West, 6th ed., 2005).

17 Id. 367.

18 Bethel School District v.Fraser, 478 U.S. 675 (1986).

19 HazelwoodSchoolDistrictv.Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260 (1988).

The Supreme Court upon hearing the case, by 7-2 vote ruled in favor of the school district. This decision reversed the Ninth Court of Appeals which had indicated that his speech was no different than the wearing of the armband in Tinker. However, the Supreme Court ruled that unlike Tinker, the penalties imposed in this case were unrelated to any political view. According to Chief Justice Burger, “…children’s rights are not coextensive with those of adults. And the First Amendment does not protect students in the use of vulgar and offensive language in public discourse.”20

In the Hazelwood case, two articles were removed from the student newspaper by direction of the school principal. The school principal objected to the content involving pregnancy experiences of three school students and the impact of divorce on children. Three student staff members of the school’s student newspaper filed suit in federal court for violation of their freedom of expression. The District Court denied the students’ request. Later, the Eighth Circuit of Appeals reversed the District Court’s decision which had decided in favor of the school administration. Upon review of the case by the Supreme Court, the Eighth Circuit court’s decision was reversed by a vote of 5-3. The majority ruling felt the principal had acted reasonably in his response to “legitimate pedagogical concerns” regarding speech (as protected by Tinker) and “speech sponsored by the school and disseminated under its auspices”. The Hazelwood standard of “reasonable exercise of legitimate pedagogical concerns” extends beyond the issue of student newspapers.

The two decisions, Betheland Hazelwood together granted school officials considerable discretion in deciding matters of student expression whether the context of the activity is curricular in nature or where the school’s sponsorship is evident and where the school’s official imprimatur (official license to print or publish) is present as in Hazelwood.21 In short, Tinker says that denial of student expression must be justified by reasonable forecast of substantial disruption; Bethel says students’ lewd and indecent speech is not protected by the First Amendment, and Hazelwood ruled schools could regulate the content of school-sponsored newspapers.22

20 Richard S. Vacca William C Bosher, Jr., Law and Education: Contemporary Issues and Court Decisions § 11.7, 297-298 (6th ed., Lexis Nexus, 2003).

21 Id.

22 Alexander Alexander, 353, 355, 367.

When considering the issue of student rights, one of the most significant issues is the deprivation of student rights as a result of a search and seizure. New Jersey v. T.L.O.23 (T.L.O.) was the landmark case in which the United States Supreme Court found the prohibition of unreasonable searches and seizures applied to public schools under the Fourteenth Amendment:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law, which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. (U.S. Cons, Amend XIV, §1)

T.L.O. set forth several important legal points about which school administrators must be knowledgeable if they wish to avoid litigation. First, T.L.O. changed school administrators’ (schools) broad protection under the in loco parentis concept. “In carrying out searches and other functions pursuant to disciplinary policies mandated by state statutes, school officials act as representatives of the State, not merely as surrogates for the parents of students, and they cannot claim the parents’ immunity from the Fourth Amendment’s strictures.”24

Second, the case established the standard of reasonable suspicion instead of probable cause as the basis for school administrators when conducting searches and seizures. The standard of reasonable suspicion provided a more flexible standard for school administrators to use as

they conduct searches when compared to the standard of probable cause for law enforcement officials. In Board of Education of Independent School District No. 92 of Pottawatomie County v. Earls 25, Justice Breyer’s concurring opinion further clarified the modified view of the Supreme Court related to in loco parentis and the need for a more flexible standard with the following statement:

Schools prepare pupils for citizenship in the Republic and inculcate the habits and manners of civility as values in themselves conductive to happiness and as indispensable to the practice of self-government in the community and the nation.

23 New Jersey v. T.L.O., 469 U.S. 325 (1985).

24 Id. 336.

25 Board of Education of Independent School District No.92 of Pottawatomie County v. Earls, 536 U.S. 822, 122 (2002).

The law itself recognizes these responsibilities with the phrase in loco parentis—a phrase that draws its legal force primarily from the needs of younger students (who here are necessarily grouped together with older high school students) and which reflects, not that a child or adolescent lacks an interest in privacy, but that a child’s or adolescent’s school-related privacy interest, when compared to the privacy interest of an adult, that falls adequately to carry out its responsibilities may well see parents send their children to private or parochial school instead—with help from the State.26

Third, and probably most significant, the decision answered some questions, but it also created unresolved legal issues (which increased litigation) because the court failed to specifically define “reasonable suspicion”, or address the following: 1) does the exclusionary rule apply to an unlawful search in school, particularly saying,

In holding that the search of T.L.O.’s purse did not violate the Fourth Amendment; we do not implicitly determine that the exclusionary rule applies to the fruits of unlawful searches conducted by school authorities. The question whether evidence should be excluded from a criminal proceeding involves two discrete inquiries: whether the evidence was seized in violation of the Fourth Amendment, and whether the exclusionary rule is the appropriate remedy for the violation.

Neither question is logically antecedent to the other, for a negative answer to either question is sufficient to dispose of the case. Thus, our determination that the search at issue in this case did not violate the Fourth Amendment implies no particular resolution of the question of the applicability of the exclusionary rule.27

2) do students have privacy rights related to lockers, desks, etc.; and 3) do standards change if police are involved? However, New Jersey v. T.L.O. did say that a search by school officials is constitutionally permissible if: 1) reasonable suspicion exists, 2) search is not excessively intrusive, and 3) it is necessary to have individualized suspicion at the inception before a search takes place?28

26 Id.840.

27 NewJerseyv.T.L.O., 469 U.S., 325 (see Footnote 3) (1985).

Statement of the Problem and Statistics

As incidents of school violence appear to become more frequent and severe, public perception is at the point where many citizens believe that schools are unsafe and administrators lack the power to control inappropriate student activity. As administrators develop safety and security procedures, they are provided limited guidance by the Supreme Court regarding the application of the Fourth Amendment to a school setting. As statistics differ on the closeness between the perceptions of danger in American schools and the reality of how safe they are, school administrators fear legal repercussions due to their uncertainties, confusion, and limited knowledge about students’ Fourth Amendment rights.

Schools are entrusted with ensuring the safety of students and staff. One measure of the safety in America’s public schools is the amount of violence on school campuses. In 1999–2000, 71% of public elementary and secondary schools experienced at least one violent incident. Approximately 1.5 million violent incidents occurred in about 59,000 public schools that year. Thirty-six percent of public schools reported at least one violent incident to police or other law enforcement personnel during the 1999–2000 school years. Of the 1.5 million violent incidents that occurred at school, around 257,000 were reported to the police. Twenty percent of public schools experienced at least one serious violent incident (including rape, sexual battery other than rape, physical attacks or fights with a weapon, threats of physical attack with a weapon, and robberies, either with or without a weapon), for a total of 61,000 serious violent incidents.29

Because of increased resources, technological improvements and media industry growth, newspapers, televisions, radios, etc. across the country broadcast the aforementioned statistics to the public. The news media communicates that students are participating in more violent and illegal behavior that includes, but is not limited to theft, the use of weapons, drugs, explosive devices and other forms of violence. While, the news media reports provide us with information on events that occur locally, nationally, and internationally in the larger society, news reports can also create a false perception, that there is more violence than what really exists. The news articles and broadcasts are communicating what appears to be a significant problem facing our schools and administrators as it relates to school safety and more specifically, searching students.

29 U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS, 2000).

In 2000, the U.S. Department of Education gathered national statistics about weapons in schools for its first annual report on school safety. These statistics do reveal weapon problems exist in a growing number of public schools. For example, 5 percent of twelfth-grade students reported being purposely injured with a weapon while they were in school during the prior twelve months; 12% of twelfth-grade students reported being threatened with injury with a weapon.30

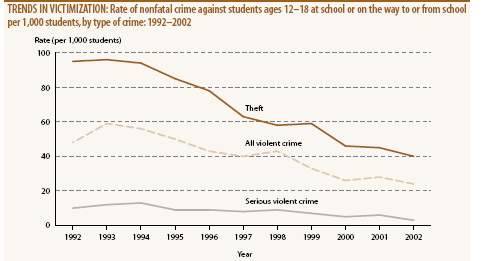

On November 29, 2004, a report issued by the Justice Department and the Department of Education titled, “Indicators of School Crime and Safety”,31 stated that crime in the nation’s schools fellsharplyfrom 1992 to 2002. School crime over that period dropped from 48 violent incidents to 24 violent incidents per 100,000 students. These figures were based on a nationwide random sample of students who were asked whether they had been victims of crime. Also, the report stated that in 2002, students 12 to 18 years old were more likely to be victims of serious violent crime away from school than at school.

The report also said that in the 12 months from July 1999 to June 2000, 16 students were victims of homicide at their schools. This represents 1% of homicide victims among school-age children during that time period. Despite these encouraging findings, the report included a number of warnings that bullying, violent crime, drinking and drugs remained a serious problem at many schools. For example, it found that 659,000 students had been victims of violent crimes, including rape, robbery and aggravated assault while at school in 2002. An additional 1.1 million students said they had been victims of theft at school during that year. In 2003, 7% of students questioned said they had been bullied while at school.

Additionally, 21% of high school students reported the presence of street gangs in their schools. Twenty percent of public schools reported that they had experienced one or more serious violent crimes in the 1999-2000 school year. Regarding the use of drug and alcohol, 5% of high school students in 2003 said they had had at least one drink of alcohol on school property in the last 30 days, 22% said they had used marijuana either at school or somewhere else, and 29% said they had been approached with offers to give or sell them illegal drugs on school grounds within the past year.

30 A. K. Miller (2003). Violence in U.S. Public Schools: 2000 School Survey on Crime and Safety (NCES, 2004–314). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS, 2000).

31 Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2004, U.S. Department of Education and Department of Justice, November 2004 at http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2005/crime_safe04/

As for violence involving teachers, the study found that teachers were also often at risk of being victims of crimes committed by students. From 1998 to 2002, students committed 144,000 thefts against teachers and 90,000 violent crimes against teachers. In 1999, a total of 9% of all teachers were threatened with injury by a student, and 4% were physically attacked by a student, according to the report.32 On the positive side, from 1993 to 2003 the number of high school students who reported carrying a gun or a knife to school dropped to 6% from 12%. Among students 12 to 18 years old who reported being bullied in 2003, the highest rate, 10%, was at schools in rural areas, while those in urban and suburban areas averaged 7%. Private schools had the lowest rate of bullying with 5%. Physical fighting on school property declined significantly, from 16.2% in 1993 to 12.8% in 2003. A similar significant linear trend was detected among all subgroups.

Conclusion, school safety is a concern, however, no significant changes were detected in the prevalence of being threatened or injured with a weapon on school property between 1993-2003 overall or among female, male, Hispanic, 10th-, and 12th-grade students. A significant linear increase during 1993-2003 was detected among white and 9th-grade students. There was a decline among black students, being threatened or injured with a weapon on school property from 1993-1999 and then an increase through 2003. The number of 11th-grade students, being threatened or injured with a weapon on school property declined during the 1993-1999 period and then remained level through 2003.33 The following figure from the publication, “The Condition of Public Education 2005, School Violence and Safety” showed a general decline in the rate at which students ages12–18 were victims of theft, violent crime, and serious violent crime at school from 1992-2002.34

32 Id.

33 D. Brener, L. Simon, N. Lowry, R. Barrious, T. Eaton, Violence-Related Behaviors Among High School Students—United States, 1991-2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report; July 30, 2004.

34 U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2005) The Condition of Education 2005, NCES 2005-094, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office at http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/2005/pdf/30_2005.pdf

Figure 1. Trends in victimizations.

From U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2005) The Condition of Education 2005, NCES 2005-094, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office at http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/2005/pdf/30_2005.pdf

Even with the positive movement towards a decline in school violence, school safety remains an issue for public schools administrators because of the continued presence of weapons, drugs, and violence on school property. One death, injury, or theft, is one too many. Increased awareness and more severe deviant juvenile (student) violence prompted an increase in aggressive interventions by school administrators and an increase in police involvement in school-related issues. In reaction to national concern and the perceived increase in school violence, federal lawmakers took several unsuccessful actions to make public schools safer. While the federal government does not have direct oversight over education in the United States, it attempted to pass several acts designed to withhold federal funds to states that did not implement the legislation on educational issues. These actions were the federal government’s unsuccessful attempt to influence how states and public education officials addressed school violence. The following table lists two of the laws passed by the federal government targeted at reducing school violence, but were ruled unconstitutional by the courts.

Table 1

Federal Laws Targeting School Violence35

Searching for Safe Schools: Legal Issuesin the Prevention of School Violence

Law Purpose And Result

Law Purpose And Result

The Gun-Free School Zones Act of

The Gun-Free School Zones Act of

1990, 18 U.S.C.A. [Section] 922

The Gun-Free Schools Act of

1994, 20 U.S.C.A. [Section] 8921

This law made it a federal crime to possess a firearm in a school zone (i.e., within 1,000 feet of a public, parochial or private school).

Ruled Unconstitutional

United States v. Lopez,514 U.S. 549 (1995)

This law required states receiving federal funds to pass legislation requiring local education agencies to expel from school for at least a year students possessing weapons in school. Exceptions are allowed on a case-by-case.

This law required states receiving federal funds to pass legislation requiring local education agencies to expel from school for at least a year students possessing weapons in school. Exceptions are allowed on a case-by-case.

In reality, a large number of studies have shown that the school environment is a safe place for children. However, the schoolhouse is still a microcosm of society. It is not uncommon for the problems that affect youth in society to become problems that school personnel must address or be prepared to respond to in their day-to-day operations and management of the school climate. Because of the types of violent acts being committed, school administrators are now more aggressively searching students and their property in an effort to maintain a safe and orderly environment for learning. The map in Figure 236 taken from the American Schools Safety Archives shows the location of some of the serious and violent acts committed at various schools around the nation from 1997 to 2004.

35 Michael E. Rozalski and Mitchell L. Yell, “Searching for Safe Schools: Legal Issues in the Prevention of School Violence,” Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, Fall, 2000.

36 American School Safety Archives, “American School Safety Archives” 1999 at http://www.americanschoolsafety.com/members/archives.html (2/24/04)

Figure 2. American schools safety. From American School Safety Archives, “American School Safety Archives” 1999 at http://www.americanschoolsafety.com/members/archives.html (2/24/04)

The National Schools Safety Center’s report (see Table 2) on school associated violent deaths and the data from the American Schools Safety Archives map indicates that there are still a large number of serious and deadly acts being committed in schools.

Table 2

Incidences of School Violence Since 1997

National School Safety Center’s Reporton School Associated Violent Deaths37

Date Incident

2-19-1997 A 16-year-old student opened fire in Alaska High School. Killed with a shotgun in a common area at the Bethel were the school principal and a classmate. Student was sentenced to two 99-year terms.

10-9-1997 A 16-year-old student in Pearl, Mississippi, was accused of killing his mother, then going to school and shooting nine students. Two of them died.

37 National School Safety Center Report on: “School-Associated Violent Deaths Report” 2004 at http://www.nssc1.org/savd/savd.pdf

12-1-1997 A 14-year-old opened fire on a student prayer circle in a hallway at Heath High School in West Paducah, Kentucky. Three students were killed and five others wounded.

3-24-1998 Two students opened fire with rifles on classmates and teachers when they came out during a false fire alarm at the Westside Middle School in Jonesboro, Arkansas. Four girls and a teacher were killed and 11 people were wounded.

4-24-1998 A 14-year-old student fatally shot a teacher and wounded two students at an eighth-grade dance at J.W. Parker Middle School in Edinboro, PA.

5-19-1998 A high school senior shot and killed another student in the school parking lot at Lincoln County High School in Fayetteville, TN.

5-21-1998 In Springfield, OR, a freshman student opened fire with a semi-automatic rifle in a high school cafeteria, killing two students and wounding 22 others. The teenager’s parents were later found shot to death in their home.

6-15-1998 Richmond, VA, Armstrong High shooting resulted in two life threatening wounds. Two suspects were taken into custody.

4-20-1999 Two students entered Columbine High School in Littleton, CO armed with a handgun, rifle, shotguns, and home-made bombs. The death toll was 15 (12 fellow students, one teacher, and the two terrorists-the latter by suicide). 20 students were injured, some very seriously.

5-20-1999 Sophomore student in Conyers, GA wounded six students in Atlanta suburb school and threatened to commit suicide.

10-1999 Philadelphia, PA Vice Principal wounded.

10-1999 Cleveland, Ohio authorities (Mayor) ordered a high school closed Friday after they uncovered an apparent plot by students to stage “violent acts”.

11-1999 Several students, who overheard classmates’ threats to plant a bomb to kill students and school employees, told their parents. The parents called school administrators resulting in the arrest of four Windsor, CT, middle school students.

11-1999 A 4-year-old boy who brought a loaded .38-caliber handgun to school in Oklahoma was suspended for one year, a punishment required by school district policy for the offense. The boy apparently got the gun from a dresser in his parents’ room.

11-1999 A boy dressed in camouflage shot and critically wounded a 13-year-old female classmate in the lobby of their New Mexico middle school. The boy also pointed a pistol at the principal and assistant principal.

12-1999 A 13-year-old student wounded four Oklahoma middle school classmates with a handgun Three boys and a girl, all students at the school were wounded in the shooting.

12-1999 A student opened fire at a Netherlands high school in a southern Dutch town, wounding a teacher and three others.

12-1999 A threatening message scrawled in a boy’s bathroom allegedly read: “If you think what happened at Columbine was bad, wait until December 15.” Classes for the remaining three days before winter break were cancelled.

12-1999 A Kansas school principal was charged with making a phony bomb threat that forced officials to close schools early. The school was evacuated immediately, followed by evacuations of four other schools.

3-2000 A shooting outside a Georgia high school killed one person and injured two.

An 18-year-old black male was shot in the head. He later died at Memorial Health University Medical Center.

3-10-2000 Francisco Valerdi, 15, was fatally stabbed about 100 yards away from Franklin D. Roosevelt High School at about 1:00 pm. He died later that night. Gang activity was suspected.

4-2000 A teacher was shot in the shoulder Monday morning at a Tucson, AZ middle school before students reported for class. The injury was not life- threatening. The school teacher who reported being shot in her empty classroom confessed to authorities that she shot herself.

5-2000 An Arkansas seventh-grade student who left school in an apparent fit of rage and a police officer, were injured after shooting each other in an altercation in a field north of the school.

5-26-2000 Barry Grunow, 35, was shot and killed by a 13-year-old student. Grunow was a teacher at Lake Worth Middle School in West Palm Beach, FL. The suspect, Nathaniel Brazil had been sent home for throwing water. He returned to the school with a gun stolen from his grandfather. When Mr. Grunow asked Brazil to stop talking, Brazil took out the gun and shot his teacher in the head.

10-26-2000 Joseph Gallo-Rodriguez, an 18-year-old tow truck driver, was shot and killed as he helped a teacher change a tire in the Bushwick High School parking lot in Brooklyn, NY. The suspect was an 18-year-old special education student, Victor Moreno.

1-10-2001 The Oxnard Police SWAT team fatally shot Richard Lopez as he held a female student hostage at Hueneme High School. Lopez was not a student of the school. The event took place in the quad just as the students were finishing lunch.

1-17-2001 Juan Matthews, a 17-year-old student at Lake Clifton Eastern Senior High School was shot and killed as he stood near a flag pole at the school’s main entrance. The suspect was not known.

3-5-2001 Santana High School student, Andy Williams shot two people in a restroom and then walked onto the quad and began to fire randomly at students. He stopped to reload as many as four times, getting off 30 or more shots. Two students were killed. The wounded included 11 students and two adults – a student teacher, and a campus security officer. Santana High is in Santee, CA. Williams was known to be a victim of frequent taunting. He told friends of his desire to shoot up the school during the weekend prior to the Monday event. Friends said he claimed to be joking and decided to let it go. One adult friend tried to call his father to warn him about Andy’s threats during the weekend, but failed to reach him. Other friends reportedly checked his backpack and “patted him down” checking for a gun before school on Monday.

3-30-2001 Neal Boyd, a 12-year-old student at Lew Wallace High School in Gary, IN, was shot and killed by 17-year-old former student, Donald Burt, Jr. in the school’s parking lot.

5-15-2001 Jay Goodwin, 16-year-old student at Ennis High School, shot and killed himself in front of a teacher and his former girlfriend after releasing 17 other hostages.

12-5-2001 Theodore Brown, 51, a counselor at Springfield High School, was stabbed and killed after he asked a male student to take off a hooded sweatshirt. The student argued and drew a knife. In the struggle, Mr. Brown was stabbed and killed.

8-8-2002 An 18-year-old student at John F. Kennedy High School in the Bronx, NY, was stabbed three times during a fight over the victim’s sister.

10-4-2002 A 13-year-old student at Page Middle School in San Antonio, TX, shot and killed herself just as school began for the day.

11-19-2002 A 17-year-old-student of Hoover High School in Hoover, AL, stabbed and killed his 17-year-old classmate between classes. No motive given.

2-13-2002 A 13-year-old student, Tony Fiske, shot into Wind River Middle School, Carson, WA and injured two students. He then used the gun to kill himself.

12-16-2002 Maurice Davis, an 18-year-old student at Englewood Tech Prep Academy in Chicago, IL was shot and killed as he tried to protect his sister from the advances of two other males.

1-13-2003 An unknown attacker slashed Jose Lopez, age 14, as he stood on the campus of Cary Middle School in Dallas, TX. The suspect was not caught.

1-27-2003 Jose Hertas was found bleeding from puncture wounds on the campus of Elizabeth High School in Elizabeth, NJ. An unknown student slashed the victim three times.

2-10-2003 Ashley Carter, 16, a student at Wilcox Central High School was stabbed six or seven times in her upper body as she attempted to walk away from the suspect, another 16 year-old girl.

3-5-2003 Sedrick Daniels, 17, was fatally stabbed in the Livingston High School cafeteria shortly after the morning bell. The suspect fled the scene and was arrested later that day.

3-28-2003 Fifteen-year-old Ortralla Mosley was stabbed repeatedly by her ex- boyfriend, Marcus McTear, using an 11 inch butcher knife in the hallway of Reagan High School in Austin, TX.

4-14-2003 Johnathan Williams, 15, was killed when an unknown gunman opened fire with an AK-47 rifle in the packed gymnasium of John McDonough High School in New Orleans, LA. Three girls were also wounded in the attack. The suspect has not been caught.

10-29-2003 David Robey, 12, shot and killed himself in the bathroom of the Rock L. Butler Middle School. Witnesses said that the boy had been picked on for months by the same group of boys and could no longer take it.

9-5-2003 Even Nash, 14, was shot and killed by his father who later killed himself. The incident happened on the track at Point Loma High School.

9-5-2003 Vasquez Acosta, 16, died as a result of a school “scuffle” in which the victim was held down and blows were delivered to his head.

9-24-2003 Jason McLaughlin (15) opened fire on students at Rocori High School in Cold Spring, MD. The gym teacher talked Jason into putting down the gun but not before he had shot and killed Aaron Rollins, and wounded Seth Bartell who died later on 10-10-2003.

12-8-2003 An unknown male, age 15, stabbed another student of Porter High School in Porter OK on the school bus. He ran from the scene as soon as the bus stopped.

1-27-2004 Saul Pena, 15, was on his way to school at Willow Glen High School when an argument on the bus escalated to an assault. Pena died of multiple stab wounds in San Jose, CA.

2-2-2004 James Richardson, 17, shot and killed another student in the cafeteria of Ballou High School in Washington, D.C.

2-3-2004 An unknown student slashed Jaime Gough’s (14) neck causing him to bleed to death in the school locker room. Gough was a student at Southwest Middle School in Palmetto Bay, FL. Other students say that Gough was a shy boy often terrorized by bullies.

2-11-2004 Gaheem Thomas-Childs (10) was killed on the playground of Pierce Elementary School in Philadelphia when a gun battle between adults moved near the school. At least 94 rounds were fired in the altercation.

6-25-2004 A female student age 16 was beaten to death in the school parking lot by a gang of more than 5 girls.

9-5-2004 Bob Mars, 44, a teacher in Benton City, WA was killed by two gang members, ages 14 and 16.

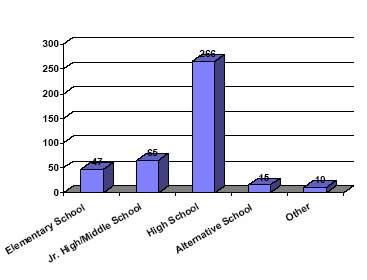

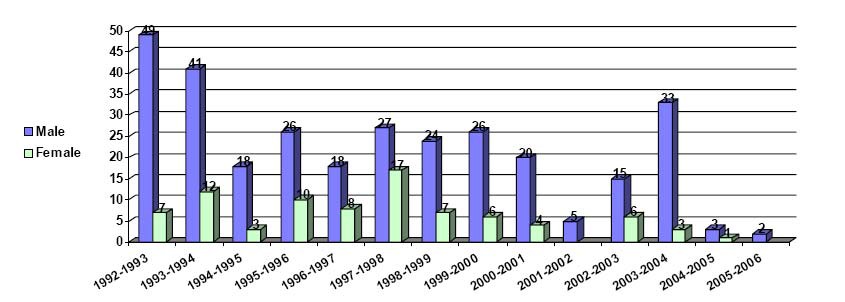

The bar graph in Figure 338 taken from The National Safety Centers Report on school associated violent deaths indicates the number of school deaths by school type between the 1992 to 2005 school years. During the thirteen-year period, there were 266 high school deaths, an average of 20.46 deaths per year.

38 National School Safety Center Report on: “School-Associated Violent Deaths Report” 2004 at http://www.nssc1.org/savd/savd.pdf

Figure 3. Deaths by school type.

From National School Safety Center Report on: “School-Associated Violent Deaths Report” 2004 at http://www.nssc1.org/savd/savd.pdf

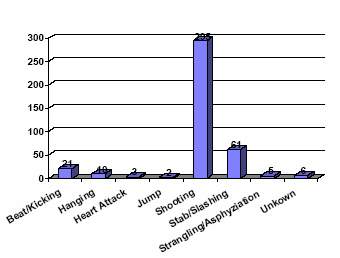

The next figure shows the method of deaths during the 1992 to 2005 school years. Shooting deaths totaled 295, an average of 22.69 shooting deaths per year.

Figure 4. Methods of death.

From National School Safety Center Report on: “School-Associated Violent Deaths Report” 2004 at http://www.nssc1.org/savd/savd.pdf

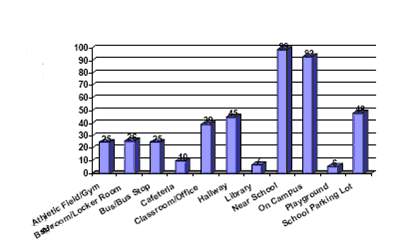

Additional data from the same report illustrated below in figures 5-7 were collected in the following areas: location of deaths, reasons for death, and victim’s gender.

Figure 5. Location of deaths.

From National School Safety Center Report on: “School-AssociatedViolent Deaths Report” 2004 at http://www.nssc1.org/savd/savd.pdf

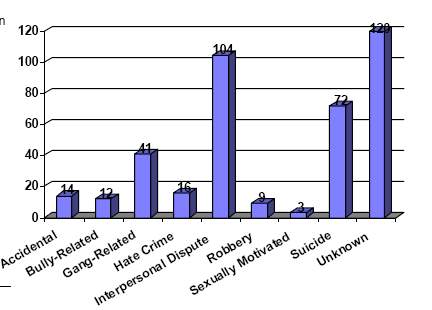

Figure 6. Reason for death.

From National School Safety Center Report on: “School-Associated Violent Deaths Report” 2004 at http://www.nssc1.org/savd/savd.pdf

Figure 7. Victim’s gender. From National School Safety Center Report on: “School–Associated Violent Deaths Report” 2004at http://www.nssc1.org/savd/savd.pdf

In reaction to these and other tragic, violent acts occurring in schools, national education organizations such as the Board of Directors of the National Association of Secondary School Principals expressed their concern by adopting position statements (see Appendix A) stressing the importance of students having a right to attend safe and secure schools.39 While attempting to meet the expectation of providing a school environment conducive to learning, school administrators increasingly search students and their belongings when presented with information that provokes suspicion. When school officials decide to search, they are often challenged in two areas:

1) the circumstances under which the search was conducted, and

2) the admissibility of evidence garnered from the search. Because of the preceding two issues, administrators must at all times consider a students’ Fourth Amendment rights which may compound the difficulty decision of what, when, where and how to search students without violating their constitutional guarantees.

39 National Association of Secondary School Principals (2000). Safe Schools at http://www.principals.org/s_nassp/sec.asp?TrackID=A2BKZTACCWXTD55UVU6KC3ESU7BBDU53&SID=1&DID=47111&CID=33&VID=2&RTID=0&CIDQS=&Taxonomy=False&specialSearch=False

As mentioned earlier, adding to the confusion is the fact that when a student violates school policy that is also a violation of the law; the offense could include addressing both school policy and the legal guidelines outlined by local, state or federal law, thus involving law enforcement officials. Since the 1960’s, the constitutional issue of search and seizure has been the subject of increasing litigation. In 1967, In re Gerald Gault,40described later in this study, was heard by the nation’s highest court to address the issue of due process for juveniles’ constitutional rights. Because search and seizure is governed by the federal constitution and in some states, comparable state constitutional clauses, school officials need to have a sound understanding of case law and the constitutional application of the Fourth Amendment to schools. Unfortunately, many administrators do not, resulting in search and seizure actions that violate students’ constitutional rights.

Purpose of the Study

It is important for school officials to know and understand the legal guidelines governing student search and seizure as well as the potential legal liability that may result from unsupported searches. The primary purpose of this study is to increase the readers understanding of student rights related to search and seizure in the school environment by providing a systematic review of relevant Supreme Court cases, post- New Jersey v. T.L.O. cases and commentary related to search and seizure involving K-12 public schools and the legal standards governing searches involving students. The secondary purpose is to provide some practical methods of applying search and seizure law to K-12 public school situations.

Guiding Questions

In New Jersey v. T.L.O.,41 the Supreme Court departed from its previous policy, which was rooted in the Doctrine of Discretionary Educational Primacy.42

40 In re Gerald Gualt, 387 U.S.1, 87 (1967).

41 New Jersey v.T.L.O.(1985).

42 Holeck, 205.

This doctrine meant that the Court would not interfere with school officials’ discretion as long as refraining would not cause serious constitutional loss. In other words, the Supreme Court no longer gave judicial deference, the Court yielding to the school’s opinion or wishes. Five central questions have been established to guide the research. The conclusion will provide answers to the five guiding questions listed below. Based upon case law, the answers are intended to help provide a better understanding of school law, especially as it relates to search and seizure in K-12 public schools. The guiding questions are:

i. Does the Fourth Amendment apply to student searches in public schools?

ii. What types/methods of searches are legal?

iii. What is considered to be a reasonable search?

iv. What guidelines should be used in search and seizure practices?

v. What things should be considered to make a search legal?

Definitions

Administrative Search: A search conducted by a school administrator, usually an assistant principal or principal.43

De novo: A second time. A writ for summoning a jury for the second trial of a case that has been sent back from above for a new trial.

Delinquent: Person who has been guilty of some crime, offense, or failure of duty or obligation.44

Discretionary Review: Form of appellate review which is not a matter of right, but rather occurs only at the discretion of the appellate court.45

Due Process: Law in the regular course of administration through courts of justice, according to those rules and forms that have been established for the protection of private rights.46

Exclusionary Rule: A rule that excludes or suppresses evidence obtained in violation of an accused person’s constitutional rights.47

Hearing de novo: A reviewing court’s decision of a matter anew, giving no deference to a lower court’s findings. A new hearing of a matter, conducted as if the original hearing had not taken place.48

In Loco Parentis: The Latin phrase that literally means “in the place of parents.” This means that school officials may discipline students as if the students were their own children.

In re: “In the matter of,” designating a judicial proceeding (for example, juvenile cases) in which the customary adversarial posture of the parties is de-emphasized or nonexistent.49

43 Black’s Law Dictionary, 1351 (7th. ed., 1999).

44 Black’s Law Dictionary, 428 (6th. ed., 1990).

45 Black’s Law Dictionary, 467 (6th. ed., 1990).

46 Kern Alexander M. David Alexander, AmericanSchoolLaw, 1034 (Thompson West, 6th ed., 2005).

47 Id. 587.

48 Black’s Law Dictionary, 725 (7th. ed., 1999).

49 Perry A. Zirkel, ET AL, A Digest of Supreme Court Decisions Affecting Education, 206 (Phi Delta Kappa, 3rd ed., 1995).

Individualized Suspicion: Individualized suspicion, also known as particularized suspicion, refers to suspicion that a particular individual has engaged in misconduct or may be in possession of contraband or evidence of misconduct.50

Interlocutory Appeal: An appeal of a matter which is not determinable of the controversy, but which is necessary for a suitable adjudication of the merits.51

Miranda: Derives from the 1966 case of Miranda v. Arizona,52 in which the Warren court required that police must advise criminal suspects of their constitutional rights prior to interrogation.53

Nexus: A causal link54

Nolo Contendre: Latin for “I do not wish to contend.”55

Parens Patriae: Concept of the state’s guardianship over persons unable to direct their own affairs. For example, minors.56

Police Officer: State officials who enforce the law.57

Probable Cause: Situation where the facts and circumstances within an officer’s knowledge and of which he has reasonable caution in believing that an offense has been or is being committed. Fourth Amendment requirement that government officials must satisfy in order to secure a warrant to search.58

ReasonableSuspicion: Lesser Fourth Amendment standard applying to searches and

seizures of students and their property by school officials. Developed from by the Supreme Court in New Jersey v. T.L.O. case.59

School Officials: Public school administrators or their designees who deal with students in disciplinary matters.

Search: An examination of a man’s house…or of his person…with a view to the discovery of contraband or stolen property, or some evidence of guilt to be used in the prosecution of a criminal action for some crime or offense with which he is charged.60

50 Schreck, Myron, The Fourth Amendment In The Public Schools: Issues for the 1990’s And Beyond, 25 Urb. Law, 117 (Winter, 1993).

51 Black’s Law Dictionary, 815 (6h. ed., 1990).

52 Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966).

53 Kermit L. Hall, The Oxford Guide to United States Supreme Court Decisions, 354 (Oxford University Press, Inc. 1999).

54 Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, http://www.m-w.com/cgi-bin/dictionary?book=Dictionary&va=nexus&x=10&y=17

55 Black’s Law Dictionary, 1070 (7th ed., 1999).

56 E. Edmund Reutter, Jr., The Law of Public Education, 910 (The Foundation Press, Inc., 3rd ed., 1985).

57 Black’s Law Dictionary, 1178 (7th ed., 1999).

58 Id. 1081.

59 New Jersey v. T.L.O.(1985).

60 Black’s Law Dictionary, 1351 (7th ed., 1999).

Seizure: Forcible or secretive dispossession of something against the will of the possessor or owner.61

Warrant (Search): An order in writing, issued by a justice or other magistrate, in the name of the state, directed to a sheriff, constable, or other officer, authorizing him/her to search for and seize any property that constitutes evidence of the commission of a crime, contraband, the fruits of a crime, or things otherwise criminally possessed; or property designed or intended for use or which is or has been used as a means of committing a crime. A warrant may be issued upon an affidavit or sworn oral testimony.62

Writ of Certiorari: Latin meaning, “to be more fully informed.” Writ issued by higher court at its discretion, directing lower court to deliver the record in the case for review.63

Writ of habeas corpus: A writ employed to bring a person before a court, most frequently to ensure that the party’s imprisonment or detention is not illegal.64

Methods of Research

Research was conducted to locate cases and other relevant commentary pertaining to the Fourth Amendment and student rights related to elementary and secondary schools. The research process included a review of literature provided by various education associations (i.e. Education Law Association, Desktop Encyclopedia of American School Law, NASSP, etc.), previous studies and dissertations, accepted legal research practices learned from previous graduate work at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (i.e. use of West Law), professional and practical training gained from serving over thirteen years as an educational administrator. For each source, key words were used to locate the information. The key words included: Fourth Amendment, School Law, Student Discipline, Search and Seizure, and Student Rights. The following sources were used:

Statute refers to legislative law derived from actions of the legislature producing either state or federal law.

61 Id. 1363.

62 Black’s Law Dictionary, 1353 (7th ed., 1999).

63 Id. 220.

64 Id. 715.

The American Digest System is a multi-volume set that indexes published court cases by legal topics and case names. Digests provide brief summaries of legal issues in the court cases indexed and citations to the cases themselves, which are published in multi-volume sets called reporters. There are several digest sets, each indexing different courts: “regional” digests index court cases from groups of neighboring states, West’s Federal Practice Digestindexes cases in federal courts, and the U.S. Supreme Court Digest indexes only U.S. Supreme Court cases. The American Digest System indexes all published federal and state appellate court cases in two parts: 10-year cumulative indexes called “Decennial” digests and monthly “General” digest volumes for years since the last 10-year accumulation.

Westlaw is one of the leading online legal research services, providing the broadest collection of legal resources, news, business and public records information to authors and those working in law-related profession. Westlaw helps legal professionals conduct their research easier and faster. At the root of the success of Westlaw is its content which includes cases and statutes, administrative materials, law reviews and treatises, attorney profiles, news and business information, and forms. With nearly 15,000 databases, more than 1 billion public records, more than 6,800 news and business publications from Dow Jones Interactive, and more than 700 law reviews, Westlaw is one of the most trustworthy and convenient online resources for legal professionals in the world. Moreover, cases, statutes, and other legal documents published on Westlaw are editorially enhanced by West Group editors for more productive searching and research leads. These enhancements include such West Group exclusives as West topic and key numbers, head notes, and notes of decisions.

Find Law is the highest-trafficked legal Web site, providing the most comprehensive set of legal resources on the internet for legal professionals, businesses, students, and individuals. These resources include Web search utilities, cases and codes, legal news, an online career center, and community-oriented tools, such as a secure document management utility, mailing list, message boards and free e-mail.

Deskbook Encyclopedia of American School Law is an annually updated encyclopedia that includes a compilation of state and federal appellate courts decisions that affect education.

American Jurisprudence is a legal encyclopedia that provides an overview of a legal issue and supports it with case citations.

The Oxford Guide to United StatesSupreme Court Decisions is a book dealing with the constitutional and legal history – the cases and decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Black’s Law Dictionary is a legal dictionary which provides definitions with pronunciations.

Education Law Association houses legal materials and disseminates legal information via a variety of publications: ELA School Law Reporter, ELA Notes, Yearbook of School Law and conferences.

Dissertations are a substantial academic paper written on an original topic of research, usually presented as one of the final requirements for the doctorate. In this case, previous dissertations related to search and seizure in schools.

Textbooks are defined as “a manual of instruction, a standard book in any branch of study”. Specifically text involving school law.

Journals are any publication issued at stated intervals, such as a magazine or the record of the transactions of a learned society (a scientific or other academic journal).

Internet is an electronic network providing access to millions of resources worldwide.

Personal Interview is a dialogue between at least two people in which one ask questions and the other answers related to a topic or group of topics.

Design of Study

The second chapter of this study will introduce the legal aspects of the search and seizure issue as it relates to the Constitutional provisions of the Fourth Amendment including the following: Exclusionary Rule, Miranda, Special Needs Doctrine, Plain View Doctrine, Probable Cause, Chimel Rule and relevant landmark Supreme Court cases. Chapter 3 will review

landmark Supreme Court cases directly related to search and seizure involving juveniles (students) and/or schools. The fourth chapter will examine selected federal and state court cases related to search and seizure organized by the type of search in the following categories: police involvement in student searches, drug policy, random, locker, mass searches (metal detector), weapon, automobile searches and canine (sniff) searches. Because state constitutional provisions may also govern student searches, I have included state decisions. In each category where applicable, I will include a Commonwealth of Pennsylvania case to provide relevant case law for Pennsylvania administrators since I am currently a practicing school superintendent in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Finally, Chapter 5 will provide a summary and conclusions.

Limitations

This study will be limited to relevant Supreme Court cases, Supreme Court cases involving K-12 education, and post- New Jerseyv. T.L.O.federal and state court decisions related to student search and seizure in K-12 public schools. Conclusions drawn are based upon these limitations.

CHAPTER II: A REVIEW OF REVELANT SOURCES OF LAW AND SUPREME COURT CASES

Introduction

“Court decisions throughout the years have established a common law of the school under which the teacher and the student have mutual responsibilities and obligations.” However, “the courts have recognized that in order for teachers to address the diversity of expectations placed upon them, they must be given sufficient latitude in the control of the conduct of the school for an appropriate decorum and learning atmosphere to prevail”.65 While there is still much to define and learn regarding student privacy and the application of the Fourth Amendment in the school setting, several relevant court cases were decided that provide some understanding of the constitutional provisions and school application.

Constitutional Provisions

While somewhat diminished since the 9/11 tragedy, Americans still enjoy and expect a great deal of privacy compared to citizens in other countries. The Constitution of the United States has served as one of the main guarantee of rights and is strongly enforced by the courts. Relevant to this paper is the Fourth Amendment which provides the right to be secure from unreasonable search and seizure. While written for the general public, the Courts have made some of the connections of how this Amendment applies to school settings and answered with a strong affirmation that students do not shed their rights when entering the school.

Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment provides for “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”66 Thus, the Fourth Amendment contains two discrete clauses: the Reasonableness Clause and the Warrant Clause.

65 Kern Alexander M. David Alexander, American School Law 306-307 (4th ed., West Publishing Company, 1998).

66 U.S. Const. amend. IV.

Reasonableness Clause and Warrant Clause

The Reasonableness Clause of the Fourth Amendment applies to all searches and seizures, and the Warrant Clause–which specifies the requirements for obtaining a constitutionally valid warrant–indicates that prior approval by a judge or magistrate must be obtained. Logically, the two clauses are interrelated. The U.S. Supreme Court has held that, with very few exceptions, searches and seizures by the state conducted without warrants are unreasonable. In recent years, the Supreme Court has also clarified the circumstances under which the Fourth Amendment does not apply. Legal situations that fall outside the scope of the Fourth Amendment include investigative methods such as “consent searches,” electronic surveillance with the consent of one party to the conversation, searches by private citizens, and searches of places and objects as to which a person has no reason to expect privacy.67

In the area of electronic surveillance (which has significantly increased since 9/11), states cannot generally give their officers more power than the federal government allows when it comes to technology, but there are loosened restrictions on consent and different definitions of the term private (e.g., email) under the wiretapping law.68 Pennsylvania law 18 Pa. Cons. §5703 which specifically mentions “electronic or computer”, requires all parties to consent, thus possibly having one of the toughest laws of all states. While electronic surveillance is not a direct part of this study, Appendix B – Federal Electronic Surveillance Law has been included as an informational resource.

Consequently, searches and seizures that either do not meet the reasonableness clause or warrant clause standard could be deemed as violations of the Fourth Amendment and result in the application of the exclusionary rule.

Exclusionary Rule

The exclusionary rule states that evidence illegally obtained cannot be legally admitted in court. The rule was first established by the 1914 case of Weeks v. United States69 and made applicable to the states via Mappv.Ohio.70 Originally, the rule only applied to federal officials.

67 Schreck, Myron, The Fourth Amendment In The Public Schools: Issues For The 1990’s And Beyond, 25 Urb. Law, 117 (Winter, 1993).

68 Tom O’Connor, North Carolina Wesleyen College, Search and Seizure: A Guide to Rules, Requirements, Tests, Doctrines, and Exceptions, Lecture, 2004 at http://faculty.ncwc.edu/toconnor/405/405lect04.htm

69 Weeksv. United States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914).

70 Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961).

In Mapp v. Ohio,71 the Supreme Court expanded the Weeks doctrine (exclusionary rule), banning illegally seized evidence. Thirty years ago, the courts were in general, but not unanimous, agreement that evidence illegally seized by school officials may not be used against students in a criminal or juvenile delinquency hearing. However recent case law indicates a significant shift in the application of the exclusionary rule to schools. In fact, the Supreme Court has ruled that evidence seized illegally by school officials may be used. A large number of the lower courts are now allowing the admission of illegally seized evidence.

The intent of the exclusionary clause is to prevent the admission of illegally seized evidence.72 In T.L.O., the Court did not consider whether the exclusionary rule is the appropriate remedy for a search conducted by school officials.

In holding that the search of T.L.O.’s purse did not violate the Fourth Amendment, we do not implicitly determine that the exclusionary rule applies to the fruits of unlawful searches conducted by school authorities. The question whether evidence should be excluded from a criminal proceeding involves two discrete inquiries: whether the evidence was seized in violation of the Fourth Amendment, and whether the exclusionary rule is the appropriate remedy for the violation. Neither question is logically antecedent to the other, for a negative answer to either question is sufficient to dispose of the case. Thus, our determination that the search at issue in this case did not violate the Fourth Amendment implies no particular resolution of the question of the applicability of the exclusionary rule.73

Does the exclusionary rule apply to the fruits of an unlawful search in the public school? Yes and no. If the evidence is going to be used to prosecute criminally, the exclusionary rule will be litigated with the question of application being determined by the court. If the evidence is to be used for disciplining the student under school rules, the exclusionary rule does not apply.74

71 Id. 654-655.

72 Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914).

73 New Jersey v. T.L.O., 469 U.S. 325 Footnote 3 (1985).

While the exclusionary rule primarily applies to Fourth Amendment protections against illegal search and seizure, it also applies to the Fifth Amendment protections against self-incrimination. The Weeks case clearly identified the basis for the exclusionary rule as the self-incrimination clause of the Fifth Amendment. The Fifth Amendment states:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger;

nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.75

“The Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination does not apply to school disciplinary proceedings; it applies only to criminal proceedings. The testimony given by a student in a school disciplinary hearing can later be used in a criminal proceeding, although a student may then object to the use of statements made at the school hearing.”76 Given that the Fifth Amendment directly pertains to law enforcement officials, it may apply to school situations when law enforcement officers are involved in the search, questioning and detention of a student. Conclusion for administrators, rather than deliberating on the law, school administrators should focus on providing students and staff a safe and orderly school environment within the guidelines established by the school district’s policies and procedures.

While Mapp v. Ohio expanded the exclusionary rule, a 1995 case, Arizona v. Evans77 provided modern day application of the exclusionary rule and technology. Evans was mistakenly detained due to an error in the police computer which indicated an outstanding warrant for his arrest. As a result of the arrest, the police searched his vehicle and found drugs. Evans argued that because the warrant was incorrect, the search was illegal. The state court agreed and the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the decision.

74 Lawrence Rossow Jacqueline Stefkovich, Search and Seizure In the Public Schools, (NOLPE, 2d., 1995).

75 U.S. Constitutional Amendment V.

76 Richard S. Vacca William C Bosher, Jr., LawandEducation:ContemporaryIssuesandCourtDecisions§11.7 297-298 (6th ed., Lexis Nexus, 2003).

77 Arizona v. Evans, 511 U.S. 1 (1995).

In deciding the case, the Court looked at three different things.

1. They decided that the exclusionary rule was created to stop police misconduct. In this case, the Court said no misconduct had occurred.

2. The Court also decided that, because there is no evidence that record keeping employees were inclined to ignore the Fourth Amendment, the computer error was probably a result of pure human error rather than an attempt to undermine the rights of individuals.

3. Without evidence that extending the exclusionary rule to mistakes made by record keeping employees would change police behavior, there was no reason to believe that finding for Evans in this case would make a police officer more accurate. After all, they determined, the officer was just doing his job.78

In New Jersey v. T.L.O.,79 the New Jersey Court reasoned that the Supreme Court of the

United States (prior cases before T.L.O. Supreme Court decision) made it quite clear that the exclusionary rule is equally applicable “whether the public official who illegally obtained the evidence was a municipal inspector, a firefighter, or school administrator or law enforcement official.” The New Jersey Court concluded, “that if an official search violates constitutional rights, the evidence is not admissible in criminal proceedings.”80 One method of gaining evidence by police is to question suspects. When being questioned by the police about a crime, citizens have a specific right to be informed of their legal rights related to answering the questions.

Miranda

When police are involved in questioning someone about a criminal offense, they are required to inform the person of their rights and provide a warning that notifies the person of the potential to use the information against them in a court of law. This is called a Miranda warning, named for the 1966 case, Miranda v. Arizona.81 This means that if the police fail to inform a suspect of his or her right to remain silent, and the suspect confesses, the confession cannot be introduced as evidence in the suspect’s trial. The case, Miranda v. Arizona,82 involved Ernesto Miranda who was arrested for stealing $8 from a bank worker and charged with armed robbery.

78 Landmark Supreme Court Cases, “The Exclusionary Rule in a Computer-Driven Society: The Case of Arizona v. Evans (1995), Summer 2002 at http://www.landmarkcases.org/mapp/society.html#outcome

79 New Jersey v. T.L.O., 469 U.S. 325 (1985).

80State In Interest of T.L.O. (1983) & Landmark Supreme Court Cases, “NewJerseyv. T.L.O.(1985). Should the Exclusionary Rule Apply to Searches Conducted by School Officials in a School Setting?”, Summer, 2002 at http://www.landmarkcases.org/newjersey/apply.html

81 Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966).

82 Id.

While in police custody he signed a written confession to the robbery, kidnapping and raping an 18-year-old woman 11 days before the robbery. After the conviction, his lawyers appealed, on the grounds that Miranda did not know he was protected from self-incrimination by the Fifth Amendment. Upon review by the Supreme Court, the conviction was overturned and the court established that the accused have the right to remain silent and that prosecutors may not use statements made by defendants while in police custody unless the police have advised them of their rights, commonly called the Miranda Rights. To be Mirandized, a person must be read the following:

1. You have the right to remain silent and refuse to answer questions. Do you understand?

2. Anything you do say may be used against you in a court of law. Do you understand?

3. You have the right to consult an attorney before speaking to the police and to have an attorney present during questioning now or in the future. Do you understand?

4. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed for you before any questioning if you wish. Do you understand?

5. If you decide to answer questions now without an attorney present you will still have the right to stop answering at any time until you talk to an attorney. Do you understand?

6. Knowing and understanding your rights as I have explained them to you, are you willing to answer my questions without an attorney present?

Schools employ police officers who are often referred to as School Resource Officers or SROs. School and law enforcement officials have to be knowledgeable about Miranda requirements when police officers or SROs are involved in the questioning or are present during the questioning of a student. When a student is in custody or believes they are in custody, the Miranda requirement applies. In the Interest of John Doe,83 a ten-year-old student was told to report to the faculty room where he was questioned by the school’s SRO regarding sexually touching a female student. The question presented before the court was whether Doe was in custody when he talked to the SRO, thus was a Miranda warning required?

83 In the Interest of John Doe, 948 P.2d 166 (Ct. App. Idaho, 1997).

The court in Interest of John Doe gave the following statement “we are persuaded that under these circumstances a child ten years of age would have reasonably believed that his appearance at the designated room and his submission to questioning was compulsory and that he was subject to restraint which, from such a child’s perspective, was the effective equivalent of arrest.” The Miranda warning was required. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Stansbury v. California, 84“ a person questioned by law enforcement officers after being ‘taken into custody or otherwise deprived of his freedom of action in any significant way’ must first ‘be warned that he has a right to remain silent, that any statement he does make may be used as evidence against him, and that he has a right to the presence of an attorney, either retained or appointed.’ Statements elicited in noncompliance with this rule may not be admitted for certain purposes in a criminal trial.”85

Another issue related to police or SRO being present during questioning involves the question of what is the Miranda warning requirement? Interest of J.C.,86 a high school student was sent to the office because he had allegedly been smoking marijuana at school. When he was questioned by the assistant principal with the sheriff deputy present, he admitted he was in possession of marijuana. The court ruled that since he was questioned by the school official and the deputy was only present, then no Miranda was required. In this case, the school official was in control and not acting as an agent of the police. The court did articulate that questioning by a law enforcement officer after a person has been taken into custody, having the feeling you are unable to leave or deprived of freedom does require a Miranda warning. “As a general rule, where a student is detained and a law enforcement officer participates in the interrogation, Miranda warnings should be given, if his confession is to be admissible.”87

The Fourth Amendment applies to searches conducted by public school officials because ‘‘school officials act as representatives of the State, not merely as surrogates for the parents.’’88

However, the Supreme Court’s T.L.O. decision set forth the principles governing searches by public school authorities. ‘‘the school setting requires some easing of the restrictions to which searches by public authorities are ordinarily subject.’’89 Neither the warrant requirement, nor the probable cause standard, is appropriate, the Court ruled.

84 Stansbury v. California, 114 S. Ct. 1526 (1994).

85 Id. Footnotes 1-3.

86 In the Interest of J.C., 591 So.2d 315 (Florida Dist. Ct. App., 4th Dist., 1992).

87 Id. Footnote 4.

88 New Jersey v. T.L.Oat 340 (1985).

89 Id. 326.

Instead, a simple reasonableness standard governs all searches of students’ persons and effects by school authorities. A search must be reasonable at its inception, i.e., there must be ‘‘reasonable grounds for suspecting that the search will turn up evidence that the student has violated or is violating either the law or the rules of the school.’’90

The scope of school searches must also be reasonably related to the circumstances which initiated the search and ‘‘not excessively intrusive in light of the age and sex of the student and the nature of the infraction.’’ “In applying these rules, the Court upheld the search of a student’s purse as a reasonable act needed to determine whether the student accused of violating a school rule, by smoking in the lavatory, possessed cigarettes. The search for cigarettes, which uncovered evidence of drug activity, was held admissible in a prosecution under the juvenile laws.”91

Certain circumstances and environments create a need for flexibility to provide protection and appropriate supervision. The school setting, at times, has been identified as such a place that may have special needs in order to provide a safe and secure environment.

Special Needs Doctrine

The U.S. Supreme Court has determined that the government has a significant interest in protecting the welfare of all people. It has also recognized that children’s constitutional rights are limited and that intrusions on those rights may be justified by a “compelling state interest.” The Supreme Court says a search is reasonable when an important governmental need, beyond the normal need for law enforcement, makes the warrant and probable cause requirements impracticable, and the government’s interest outweighs the individual’s privacy interest. For instance, the “special needs doctrine” enables states (school officials) to circumvent the warrant and probable cause requirements of the Fourth Amendment when certain requirements are met. The “special needs” doctrine has often been applied in suspicionless drug testing cases.

Several non-education cases set the foundation for decisions related to the “special needs” doctrine. The 1989 case, Treasury Employees v. Von Raab,92 the court ruled that the “United States Customs Service’s suspicionless drug testing of employees applying for promotion to positions involving interdiction of illegal drugs or requiring them to carry firearms was reasonable under the Fourth Amendment; government’s compelling interest in safeguarding borders and public safety outweighed diminished privacy expectation in respect to intrusions occasioned by urine testing program, which was carefully tailored to minimize intrusion.”93

90 NewJersey v. T.L.Oat 342, 326 (1985).

91 Find Law: U.S. Constitution: Fourth Amendment, Annotations p. 4 at http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/data/constitution/amendment04/04.html#5, 113.

92 Treasury Employees v. VonRaab, 489 U.S. 656 (1989).

Also in 1989, Skinner v. Railway Labor Executives’ Ass’n, said “Lack of individualized suspicion required to conduct blood, breath and urine testing for railroad employees to determine drug and alcohol content did not make intrusions unreasonable as, to the extent transportation and similar restrictions were necessary to procure the testing, the interference was minimal given the employment context for railroad employees.” The 1997 case, Chandler v. Miller 94 provided the following statement related to position and job requirement for special needs establishment, “Alleged incompatibility of unlawful drug use with holding high state office did not establish special needfor drug testing of candidates for state office as required to depart from Fourth Amendment’s requirement of individualized suspicion for search; there was no evidence of drug problem among state’s elected officials, those officials typically did not perform high-risk, safety-sensitive tasks, and required certification immediately aided no interdiction effort.”

In T.L.O., the Supreme Court concluded that the Fourth Amendment does not require school officials to obtain a warrant before searching a student who is under their authority because they felt the warrant requirement was not suited for a school environment.95 Namely, the state must articulate a “special need” for the search or seizure, after which the court will balance the governmental interest against the individual’s privacy interests. Under this doctrine, federal courts have upheld warrantless, suspicionless drug-testing programs as applied to certain groups of minors.96

93 Id. 677, 1397.

94 Chandler v. Miller, 117 S. Ct. 1295 U.S. Ga., 1997.

95 David Badanes, “Earls v. Board of Education: A Timid Attempt to Limit Special Needs From Becoming Nothing Special”, St. John’s L. Rev (2001).

96 Shannon D. Landreth, “An Extension of the Special Needs Doctrine to Permit Drug Testing of Curfew Violators,”Vol. 2001, Issue5 U.ILL.L.Rev(2001).

Plain View Doctrine

Another aspect of search and seizure of evidence without a warrant is the doctrine of “plain view”. The plain view doctrine states that objects falling in the ‘‘plain view’’ of an officer who has a right to be in the position to have that view are subject to seizure without a warrant or that if the officer/official needs a warrant or probable cause to search and seize his lawful observation will provide grounds. American Jurisprudence, Second Edition states, “Under the