Can Technology Enhance the Educational Learning Outcomes of the Museum Visit?

Info: 12176 words (49 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Tagged: EducationTechnologyLearning

Acknowledgements………………………………………………..…………… 4

Abstract……………………………………………………………….………….. 5

Chapter 1. Introduction………………………………………………………… 6

- Background and Motivations……………………………………….. 6

- Problem………………………….……………………………………. 6

- Aims and Objectives………………………………………………… 7

- Research Methods…………………………………………………… 8

- Chapter Summaries……………………………………..…………… 9

Chapter 2. Literature Review…………………………………………………. 11

2.1 Introduction…………………………………………………………… 11

2.2 Museum Design……………………………………………………… 11

2.3 Purpose of a Museum………………………………………………. 13

2.4 Key Types of Museum Visitor………………………………………. 14

2.5 Museums as a Learning Environment…………………………….. 16

2.6 Virtual Museums……………………………………………………… 18

2.7 Augmenting Museums………………………………………………. 19

2.8 Social Interaction…………………………………………………….. 20

2.9 Technology as a Way to Enhance the Visitor Experience………. 20

2.9.1 Infrared Radiation…………………………………………. 22

2.9.2 The Personal Digital Assistant…………………………… 22

2.9.3 Google Glass………………………………………………. 23

2.9.4 The Multi-touch Table…………………………………….. 23

2.9.5 Holography…………………………………………………. 24

2.10 The Price of Technology…………………………………………… 24

2.11 Myartspace………………………………………………………….. 25

2.12 Further Literature…………………………………………………… 26

Chapter 3. Design and Development………………………………………… 28

3.1 Exploring Existing Technology…………………………………….. 28

3.2 What technologies will be used?………………………………………….. 31

3.3 Aurasma………………………………………………………………. 32

3.4 The Exhibit……………………………………………………………. 33

3.5 Limitations……………………………………………………………. 34

Chapter 4. Implementation……………………………………………………. 36

Chapter 5. Critical Evaluation………………………………………………… 37

Chapter 6. Further Work………………………………………………………. 39

Chapter 7. Conclusion…………………………………………………………. 40

References………………….……………………………………………………. 41

Appendix…………………………………………………………………………. 44

Abstract

“Can technology further enhance the educational learning outcomes of the museum visit?”

This study tries to answer this very question and provide, implement, and evaluate a design model which successfully enhances educational learning outcomes in this space. Through the review of literature it is established how museums are used as centers of learning, how technology is developing within the museum and which type of visitor is engaging with it. The project is then evaluated and alternative paths discussed.

Chapter 1. Introduction

- Background and Motivations

Many people think school days were some of the best days of their life. Museum visits list highly on their list of fondest memories during this special time.

During the latter part of the twentieth century, interaction in a museum was talking with classmates about a particular artefact, listening to the dinosaur roar by pressing a button under the words ‘Tyrannosaurus Rex’ or by completing a quiz about the visit on a scrap of printed paper with a pencil hardly big enough to fit in the hand.

Did the museum visit help educational learning outcomes at this time? The short answer is, a little, but not enough. Should today’s technology have existed back then maybe more exams in this field would have been passed and more thought would have gone in to the preservation and cultural heritage of the museum and its environment.

This project is a chance to re-engage with fond memories and a chance to further explore in the context of museums, the tools of education and the technology now used.

- Problem

Nina Simon, Executive Director of the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History (Simon, 2011) claims the two biggest problems in the cultural sector commonly talked about to be finding new business models to sustain funding and support operations, and making offerings relevant and appealing to shifting audiences. These problems could just as easily be associated with any industry. The real problems lie in making the educational knowledge gained through visits to the museum as freely accessible as possible whilst at the same time, keeping the visitor interested.

By the late twentieth century technology was little used in the museum space and in this traditional form of the museum the level of engagement with exhibits struggled to keep a high enough level of interest that the visitor would then remember what they had seen, and the history or relevance behind it.

Over the last twenty year’s technology has gradually been introduced to the cultural sector and has, in certain environments proved to enhance the visit in terms of educational learning. Problems still lie in the museum that wishes to stay ‘traditional’ or is worried about the extra expense of incorporating an interaction between visitor and technology or the expertise and personnel to maintain this to the standard required.

This study aims to find a ‘low tech’ option which incorporates all cultures without discrimination but provides enough interaction to keep the visitor engaged and able to remember the information supplied.

- Aims and Objectives

The project aim is to explore the use of technology in museums and art galleries, and to design, implement, test and evaluate a solution to further enhance the educational learning outcomes of a museum visit.

To explore through research and literature the use of technology as a method of learning in the museum and gallery environment.

To explore different types of interaction available at a museum and to realise how it can help educate.

To explore and categorise the different visitor types to the museum and evaluate the reasons behind their visit.

Critically evaluate ideas and solutions for the development of a design outcome to further enhance the educational outcome of the museum visit and to design solutions with the use of technology and within the limitations of this long study.

To implement and test a solution and evaluate its success, exploring further how it can actively be taken forward and improved upon.

- Research Methods

Research shall be carried out on the understanding that the goal is to design a technology based solution to further enhance the educational learning outcomes of the museum visit. Thus, the main part of research will be tailored around areas of interest in connection to the scope of this.

Research shall be carried out mainly with literature and case studies that back up any facts or figures mentioned.

Other methods of research may include, but are not limited to the ethnographic approach. For example, to spend time watching and measuring visitor’s dwell time and exhibit interactivity in a museum. Using this approach may result in skewed data and personal choices could affect the outcome and so any findings will need backing up with further research.

There are certain testing limitations pre-design and after implementation. For example, lots of research has been carried out using tracking devices such as tickets with RFID tracking tags which would allow to map out user behaviour in an environment. Data could then be evaluated to measure findings. Putting this in to real-world practice within the scope of this project could be difficult due not only with the access to technology but also the ethical factor.

- Chapter Summaries

This study contains seven chapters, each one focusing on an area of interest providing sufficient reasoning to choices and directions taken in the motivations, research, design, build, and implementation of the final project.

The chapters are:

Introduction. This chapter contains the motivations and reasoning behind the area of study, project aims and objectives, and information on the methods of research which will be used to build the foundations of the project on the way to implementing a design solution with supporting literature for the decision-making process.

Literature Review. This is where any research began and drives the project through from the beginnings of museum design and purpose, establishing the key visitor types and the technology they may use and explores museums as a learning environment.

Design and Development. This chapter further explores existing technologies and how the museum is using it in an educational sense. These technologies tie in with what three chosen key visitor types may find most useful in the context of the reason for their visit to the museum. This builds from the project foundations earlier laid to establish a design model to take forward for implementation and testing.

Implementation. Following on from the design and development stage, the model is implemented. This chapter talks about what needed to be done to make this happen, what happened, and about why it happened.

Critical Evaluation. The design and implementation are evaluated. This chapter discusses why or why not it is believed that the design would further enhance the educational learning outcomes of each of the key visitor types and the processes throughout the project are analysed.

Chapter 6 explains what could be done to improve the design model and explores alternate strategies going forward should this project be continued.

Conclusion. The study is rounded up and any loose ends are tied off. Can technology further enhance the educational learning outcome of the museum visit? This chapter does its best to offer an answer.

Chapter 2. Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

Galleries and museums in the current century are embracing digital ways to showcase their collection, ensure the preservation of the cultural heritage around the world and make their exhibits accessible to the public in an attractive way (Noy, 2016). A gallery is a place where exhibits are displayed with a particular function. Museums are institutions in service of the society in which objects of art, science, history and cultures are stored and exhibited. Virtual museums as the name suggests are online ways of displaying what a museum does. They are collections of recorded images, sights, sounds, historical data, cultures, and artifacts that draw the characteristics of a museum through electronic means. Technology is an activity that changes cultures as it aims at creation and use of technical ways to invent useful things that enable problem-solving. Various technology exists post-twentieth century, with increasing innovation creating new applications for both business and for personal use.

2.2 Museum Design

Exploring various museum types leads to research around the design of the museum (external and internal, the changing forms of the museum, and are museums designed with the flow of visitors in mind).

The incorporation of technology in learning experiences in museums has been done as a result of the growing demand for personalisation of the experience within these institutions. The learning experience has always been seen to be best effective when technology is added as a learning tool; this increases interest as well as retention rates and improvement of the overall experience (Alvermann et al., 1999). Cultural heritage comes out as one of the key components of museums. The museums and galleries are designed as exhibitions of various aspects of human heritage, the most vital being culture. In the modern age, institutions are fast embracing differentiation as a way of increasing their validity and allure. Customisation of services and products is thus becoming a new aspect of establishments.

In museums, there is an increasing interest in ensuring the accessibility of collections to a larger audience with cultural heritage incorporated through the use of web-based and mobile information tools (Ardissono et al., 2011). The Internet and wireless technology enabled museums to exploit the avenues for larger marketing and exhibition, as well as enhancing the learning experiences for individuals seeking to explore the facilities and collections (Ardissono et al., 2011). Technology provides easier means of creating memorable experiences along with ensuring easier management of collections. With the increasing awareness of mobile-based applications and internet-based services and applications, museums are utilising technology to improve the quality of their services and develop new concepts such as the virtual the museum space.

2.3 Purpose of a Museum

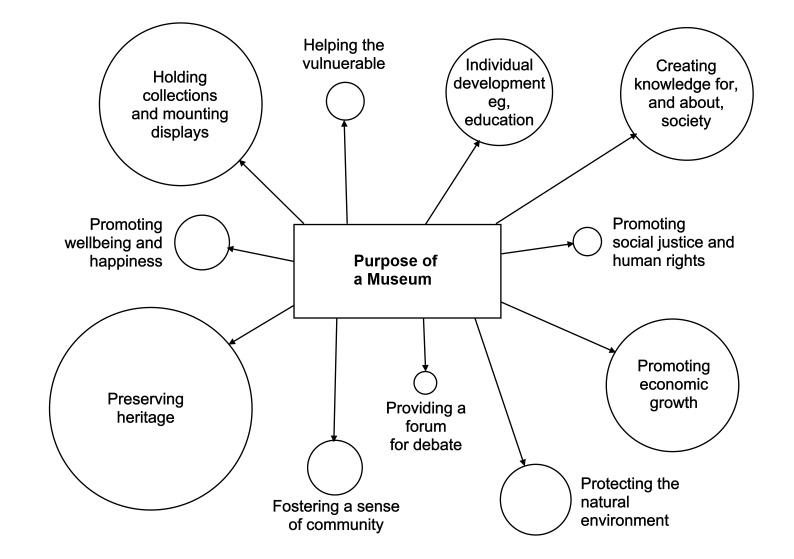

Figure 1

In March 2013 BritainThinks prepared a report for the Museums Association which researched public attitudes to the purpose of the museum and to the future of museums in general (BritainThinks, 2013). A series of workshops were conducted across the UK with a diversity of locations in both rural and urban areas at different types of museum. “During the workshops, participants’ attitudes were explored through a combination of open discussions and hands-on exercises”. Based on this report Figure 1 demonstrates the eleven purposes of a museum.

“Participants’ attitudes to the roles and purposes of museums were carefully teased out over the course of each workshop” (BritainThinks, 2013).

In total the list was rounded down to eleven reasons the public perceived a museum to be the purpose of. Each purpose was ranked in order of importance. The public thought the most important reason was the preservation of heritage. Participants thought it was vital that historic artefacts were kept safe even if never (or very rarely) displayed to the public. The museum therefore has an important hoarding role. Other reasons were for holding collections and mounting displays, for creating knowledge, for, and about society, for promoting economic growth, and fifth on the list, and the purpose for which a lot research was carried out, was for Individual development such as education and learning.

Many of these reasons are backed up by N.J. Merriman from the Institute of Archaeology, University College London who says of the purpose of the museum that they “enable people to explore collections, for inspiration, learning and enjoyment. They are institutions that collect, safeguard, and make accessible, artefacts, and specimens, which they hold in trust for society” (Hardesty, 2010).

2.4 Key Types of Museum Visitor

There are different cultures in the world hence the need to embrace technologies that incorporate all these cultures without discrimination or neglect. Various media is used to provide information like audio and visuals. Audio includes comments on the exhibit as well as audio comments from audio guides. Visual media includes labels as part of the artifacts and those adjacent to the artifacts. Studies conducted have established that different age groups and first-time visitors or returning visitors have variations in the time spent in the museum. The type of information offered by museums, and also galleries, has to vary to incorporate the different groups (Styliani et al., 2009).

Some of the first literature researched for this study was a book called ‘Identity and the Museum Visitor Experience’ in which renowned researcher John Falk attempts to create a predictive model of visitor experience. He identifies five key types of visitors who attend museums and then defines the internal processes that drive them there over again.

Drawing on case studies from other professionals in the field, Jan Packer, Roy Ballentyne and Theano Moussouri, Falk revealed the five categories of visit motivations as:

- Learning and discovery

- Passive enjoyment

- Restoration

- Social interaction

- Self-fulfilment

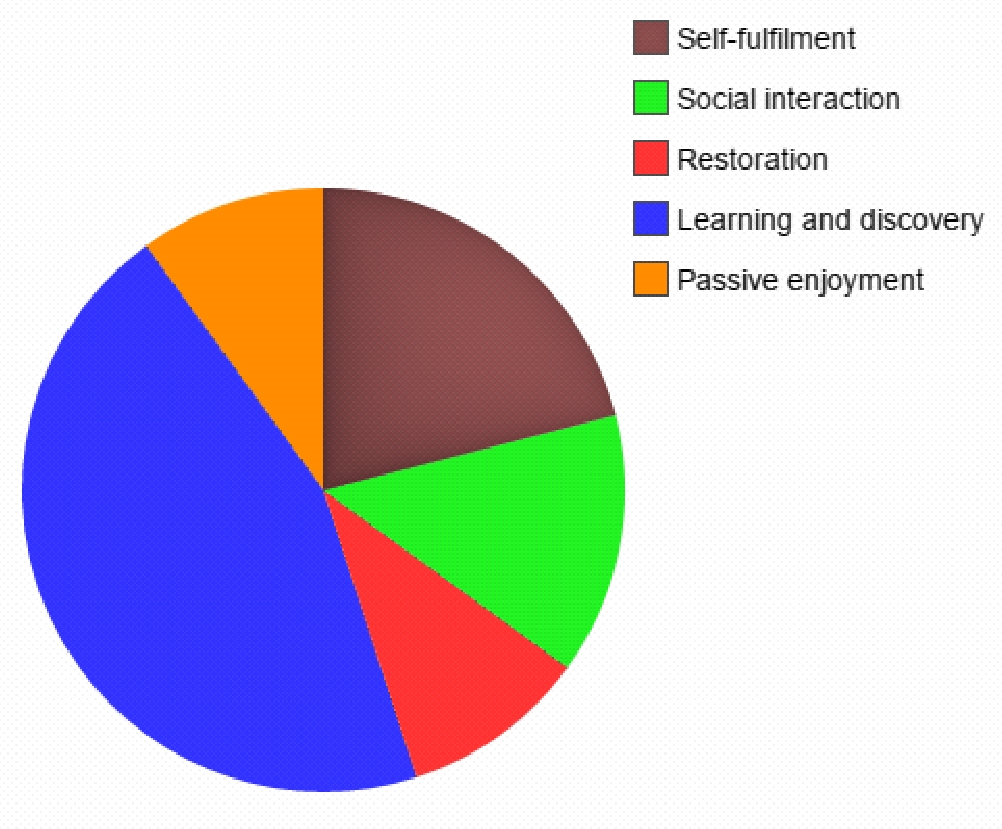

He further explains, “Packer and Ballantyne described learning and discovery as the desire to discover new things, expand knowledge, be better informed, and experience something new or unusual. As found by Moussouri in her initial work, this was the most common category. Also, closely mirroring Moussouri’s data, the second most common category was passive enjoyment – the desire to enjoy oneself, to be pleasantly occupied, and to feel happy and satisfied” (Falk, 2009).

Restoration is explained as the desire to relax mentally and physically, to have a change from routine, and recover from stress and tension. Social interaction is described as the desire to spend time with friends or family, interact with others and build relationships, and finally, citing Packer and Ballantyne once more he mentions self-fulfilment as the desire to make things more meaningful, challenge abilities, feel sense of achievement, and develop self-knowledge and self-worth.

Using Falk’s five key-types of visitor model more research would be carried out; Self-fulfilment is best associated, but not limited to augmented reality. Platforms associated with this are Aurasma, Daqri, Metaio, and the Microsoft HoloLens; Social interaction could be triggered through augmented reality but ultimately leads the user to share and express their thoughts and feelings through social networks such as Instagram, Tumblr, Pinterest, Facebook, and Twitter; Restoration is the visitor model that would best be suited to using virtual reality. In technical terms, virtual reality is the term used to describe a three-dimensional, computer generated environment which can be explored and interacted with by a person. That person becomes part of this virtual world or is immersed within this environment and whilst there, is able to manipulate objects or perform a series of actions (VRS, 2017). Google Cardboard, Samsung Gear, and Oculus Rift are brands associated with the development of virtual reality; Learning and discovery is the visitor model best connected with education and also multimedia, such as film, television, and the media. Multimedia also fits quits well in the self-fulfilment model; Passive enjoyment is the last of the visitor model types and is best described as the passer-by or the window shopper.

2.5 Museums as a Learning Environment

Packer and Ballantyne described learning and discovery as the desire to discover new things, expand knowledge, be better informed, and experience something new or unusual (Falk, 2009).

In 2011, Dr Lynda Kelly was commissioned by The Sovereign Hill Museums Association in Australia to write a report around Student Learning in Museums.

Dr Kelly said of the context for learning in museums that they are “often called ‘free-choice’ learning environments. Museums have the opportunity to shape identities – through access to objects, information and knowledge visitors can see themselves and their culture reflected in ways that encourage new connections, meaning making and learning” (Kelly, 2011).

Dr Kelly is Head of Learning at the Australian National Maritime Museum, and prior to this worked in digital and audience research at the Australian Museum, Sydney. She has published widely in this field in Australia and for museums internationally, pens a well followed and read blog, and openly shares her interest and research in visitor experiences and learning how these can be measured, the strategic use of audience research, and about new technologies in organisational change.

In recent decades, museums have received recognition as centers of learning for developing the teaching and learning process. They provide exposure to the subject matter, resources in one’s community and social experiences. Museums create a podium for learning inquiry, which enables them to pick new ideas and have positive attitudes. Through research, it is suggested that repeat visits tend to be more effective than one-time visits as different people cognitively take in aspects differently to be able to grasp more. Preparation includes a pre-visit which includes psychological, cognitive, spatial orientation, training on practical skills like note taking and post visits. Post-visits include analysing the chosen ideas, enables students to take in the new ideas, learn, assimilate them and tag them off misconceptions. Multimedia and audio guides are used in museum exploration and information search (Vavoula et al., 2009).

Co-Creation is key in the digitalisation of galleries, libraries, archives and museums (GLAMs). GLAM have to build communities of learning through cultural institutions that share experiences, best practices, learn, and adapt to the various situations and circumstances. The participatory approach is the first step to realising this. Involved professionals and researchers apply some theories, such as knowledge and crowdsourcing. Technology, cognitive principles, psychology, and community building rules enable the every-day growth of content, an establishment of norms and sourcing, and sorting information from its broad view then narrowed down to ease understanding (Tammaro, 2016).

There are four key components to learning: acquiring information, using it, sharing it with others and reflecting on it. Capitalising on students as learning resources can enable schools to gain a lot as there is a thin line between teachers and students. Social networking allows people to participate and get access to new learning by broadening learning options. It enables knowledge to be transmitted through active participation, and engagement of the audience. A platform of ideas, their interpretations and assemblage are necessary to link the experiences of visitors with those of other people. Personalisation of information is enhanced by tagging the content and providing their key search words for the database collected. Creation and sharing of context can be done so by media like Click and Flick sites and Myartspace (Vavoula et al., 2009).

2.6 Virtual Museums

Virtual museums were first introduced by André Malraux (1947), he expounded on it as a museum without boundaries, that is accessible to the world. They utilise technologies like virtual reality and augmented reality. Museums are entertaining and informative and aim to gratify and educate visitors. With this, the use of the internet has been explored to attain memorable experiences. The internet enables access to museums to be better and ensures there is the minimisation of costs for the information and learning services offered. Space limitation is taken care of by this new advancement of virtual museums. As space is not the limit, a wider range of exhibits can be shown or made available to the public for their scrutiny (Styliani et al., 2009).

Museums began embracing new ways of conveying context information to exhibits, and virtual museums were created enriching the museum experience as early as the nineteen-eighties. There are many types and forms of virtual museums; the brochure, content and learning museum. The content museum makes information about museum collections available by the creation of a website. A brochure museum is a marketing tool for museums as it provides the essential information that is the location, calendar of events to future visitors, and information about what museum database is made up of. The learning museum is a website in a context-orientation that offers points of access in regards to age, knowledge and cultural backgrounds. It enables the visitor to establish a personal relationship with the collections.

Interactive exhibits have grown to include in structural designs, provide pro-active learning and provide a balance between learning and leisure. Some of the emerging tools and technologies used by virtual museums are: imaging technologies like the JPEG200 image formats, Web3D exhibitions, reality exhibition-virtual, augmented and mixed, haptic and the use of handheld devices in museums like smartphones and tablets. Imaging technologies can be used to cater for visitors’ needs and enable them to enjoy a better experience by allowing interaction with the content. This can be done while providing education and entertainment. Virtual museums can better preserve heritages and cultures passing it on to the incoming generations for a better understanding of the world in its artistic nature (Styliani et al., 2009).

2.7 Augmenting Museums

Augmenting museums has a lot of pros that include time-saving and efficiency. A visitor can be served more efficiently, and information acquired in little or no time. Museums can also be used as centers of providing formal education to young students in schools (Baber et al., 2001). A range of information technologies is utilised in digitising museums. Some of these technologies include computer exhibits and personal digital assistants (PDAs). The aim is to enable new forms of participation and interaction by new visitors. To incorporate these new technologies, curators, educationalists, designers, managers, museums, galleries and science centers all need to collaborate. At the turn of the century interaction in museums and galleries depended greatly on touch screen interfaces (Baber et al., 2001). Touch-screen interfaces require interaction with the visitors by the use of actions, prompts, and responses provided by the system. This form of interaction prioritises the user’s specific goals and transforms these around to use the exhibit with an audience. Screen-based systems are also employed in arts and science museums and centers. Information kiosks and multimedia devices have been developed as screen based systems to enhance the information provided (Baber et al., 2001).

2.8 Social Interaction

Social interaction is critical to visitors’ experience in exhibitions as they come in pairs or groups. Social media can impact informal learning in museums, libraries, and galleries. It opens up the art world to young people making art to be able to be explored (Russo et al., 2009). Digital literacy enables further strengthening of the connection between young learners and the informal learning environment to improve and make the learners active cultural participants. Globally information and communication technology (ICT) is deep rooted in homes, at workplaces and in schools as it is shaping the way people communicate and is providing a new platform for learning. Certain skills and strategies are necessary for one to adapt to the changing world. Media literacy is the ability to encode and decode media symbols that are to analyse, evaluate and create accessible media in a variety of forms: access, analyses, evaluates competencies and content creation (Russo et al., 2009).

2.9 Technology as a Way to Enhance the Visitor Experience

The use of technology in museums has been seen as a way of increasing the experience of visitors and a means of providing information so as to enhance their experiences (Manabe & Lydens, 2007). It is also considered as a way of giving more control and offer a learning process for cultural visitors using existing technologies, such as audio guides for self-guided tours, mobile applications, touchscreen-based information desks, or reality applications combined with wearable technologies among others. Social and mobile technologies use virtual reality or augmented reality to enhance the learning experience, using mobile augmented reality applications within art galleries (Dieck et al., 2016). The use of this technology in cultural and educational institutions has proven to offer learning opportunities and can be found everywhere in modern society. Digital devices with information and communication technologies in museums and exhibits are increasingly used more often. These include ordering systems such as eTable technology, mobile platforms, tablets, various social media channels such as Facebook and Twitter and mobile applications (Dieck et al., 2016). New technologies provide relevant and tailored information, serving to enhance interpretation and engagement with object-rich collections (Lehn & Heath, 2005).

More museums should consider creating spaces for individual and collaborated participation ensuring they have available resources to have an excellent experience and better sense of exhibits. Not every person can be satisfied using a single method of information presentation. This can be sorted by Information Technology (IT). A picture and text can be recalled rather than a picture on its own, and different cultural groups prefer different background information. Imaging technologies can be used to cater for visitors’ needs and enable them to have a better participatory experience by allowing interaction with the content while providing education and entertainment. Education is critical and crucial in the world, and any possibility of storing and passing down cultures and information of what makes us human attracts the need to be kept for future generations. Therefore, digital ways should be embraced to improve learning and highlight new features for museums, as technology is currently the best way to handle learning in our world yesterday, today and tomorrow.

However, the question that remains is which kind of technology can be applied easily, looking in to costs of setting up, maintaining, and integrating into easier ways for the visitors on the establishments. The evolution and convergence of technologies and the need to incorporation information technology into galleries and museums have created a new avenue for personalisation and the potential to increase information presentation, disbursement and augment learning experiences (Ardissono et al., 2011). In various user groups, different technologies can be applied to ensure the personalisation of the services or products provided to the clients. New ideas and technology keep being developed, and it is essential to identify the trends in user preferences and provide realistic options depending on the institution and the products provided.

2.9.1 Infrared Radiation

Technology is crucial in information storage. Through electronic storage of information, one is able to tailor information provided about an artifact across different media and platforms. An example of such technology is the infrared transmission. An Infrared Radiation (IR) is electromagnetic radiation that carries energy. An IR transmitter collects information by transmitting a response to an IR receiver adjacent to the piece of art or exhibit. It was discovered by Sir William Herschel, an astronomer in 1800. IR would be contained in a badge offered to a visitor. Through it, different visitor groups could be arranged for better service with the information that is crucial to the aim of visiting. This is then passed on to a computer where the data could be stored in a database for future referencing (Baber et al., 2001).

2.9.2 The Personal Digital Assistant

The Personal Digital Assistant (PDA) is a device that is used in museums and other establishments to provide information to the user about the artwork or exhibit on display. PDAs are portable and have small screens that display information about the exhibit or purpose and can be used to make selections by virtue of a touch-screen interface. They can deliver multimedia content, text, and images as well as sound and video files. The visual content appears on the screen whilst the audio information is delivered via headphones (Lehn & Heath, 2005). As one of the devices is in use, information about the artwork or exhibit in the museum or gallery are available to the user. It displays information in various stages as the individual walks through the establishment making an observation and learning about the different objects displayed.

2.9.3 Google Glass

Google Glass as another technological device used in the enhancement of the museum and gallery experience to visitors. This learning experience has been hailed as informative and practical. The Google Glass is a device that creates an augmented reality by overlaying digital content onto the real object to the user and gathers information instantly displaying it to the wearer creating a realistic and enjoyable learning experience (Dieck et al., 2016). This device adds another dimension of instructiveness, engagement, and personalisation while at the same time being inconspicuous to other users. Google Glass is seen as a platform to engage users and at the same time incorporate fun into the learning experience while efficiently passing. Augmented reality can provide not only facts and knowledge but can also deliver realistic contexts and reconstructions of events, therefore, enhancing the entire learning experience and making it more applicable (Dieck et al., 2016).

2.9.4 The Multi-touch Table

One of the most commonly used forms of technology in museums and galleries in recent years is the Multi-touch Tabletop and Holography. The Multi-touch tabletop is based on the Frustrated Total Internal Reflection (FTIR) system made up of four layers of acrylic as the base, tracing paper with silicon, plain tracing paper, and the final layer of polyethylene terephthalate (or PET) sheet. The FTIR horizontal table uses a data show projector, a mirror system, an eye camera modified for infrared vision, an infrared LED ribbon, a compliant surface, sound speakers and a laptop or controlling computer (Correia & Mota, 2010). Images of exhibits, artwork or collections are projected scattered on the white screen which in turn allows the user to select and drag the picture onto the interaction area to view and assess as detailed information about the artwork is displayed. However, there are challenges of building the software and hardware of this table for a public space like an art exhibition as a mediator for the artwork and visitors social interaction is a major concern. The Multi-touch table as a large shared physical object allows for a different relation with the virtual information and also, with the other pieces, promotes a social experience that could lead to collaboration scenarios where groups actively participate (Correia & Mota, 2010).

2.9.5 Holography

Holography is a technology used in museums and has been considered a powerful tool for three-dimensional (3D) imaging display techniques pertinent for museum applications, capturing the attention of the specialists involved in the development of novel display technologies (Markov, 2011). Holography uses 3D image displays of any object or artifact without having the object of display physically present, and a hologram can simulate the conditions of observation similar to the real object. Holography is very popular since it provides nondestructive inspection of artifacts, detection, and visualisation of defects, restoration quality control, object demonstration, storage and preservation including classification and identification of museum objects and high-density data storage among others (Markov, 2011). Holography works well in museums where there is limited space for displaying artworks and artifacts, also, where transportation of fragile artifacts is a problem, hence the need for a holographic 3D display. Objects that have been worn out through time and exposure and are unattractive for display or incomplete artworks and those unavailable in the museum for security concerns are also reasons why a 3D display may be used. Furthermore, holography allows the recording of high resolution multiple images on the same carrier therefore allowing the visual perception of the object to be substantially enhanced.

2.10 The Price of Technology

The technology and devices used in the enhancement of museum and galleries come with a price that needs to be accounted for in terms of visitations and usage as growing interest in exploring the ways in which new technologies can enhance participation in museums and galleries. The growing importance of new technology for the museums and galleries has given rise to discussions about whether its placement in exhibitions offers value for money (Lehn & Heath, 2005). As more and more digital displays and technologies are introduced to galleries and museums for visitors, the need for low tech options is important as growing interest in new technology amongst museum managers intensifies. These devices are viewed to be of critical importance to enhance the museums’ role as educational institutions and are used to support the interpretation of exhibits and to increase the appeal of museums to the public (Lehn & Heath, 2005). The technology used might be limited in space like the Multi-touch table that requires space and special care to install the hardware and the software in the gallery (Correia & Mota, 2010). Others like the Google Glass acknowledge that the opportunities provided by wearables for ICT-enhanced learning in museums and art galleries are scarce, especially to great galleries that attract scores of visitors (Dieck et al., 2016).

2.11 Myartspace

Mobile devices are being used to bridge lessons to students seeking to visit museums and galleries. Myartspace is one of the services used on smartphones to allow clients to gather information that they can retrieve, view, contemplate on, share and present back at school after visiting establishments. It was developed around ten years ago. Myartspace interacts in three spaces: the physical space of the gallery, museum and classroom, the personal space created by students on their smartphones and personal computers (PCs), and the virtual space containing artifacts collected online. The evaluation of this service can be based on three levels: micro-level through its usage, meso-level through its effectiveness in learning, and macro-level through the impact on school museum visits using new technology (Vavoula et al., 2009).

Micro-level examines the usage of the utility and individual activities of the technological users. This can range from note-taking to taking pictures, and more frequently in recent years, selfies with works of art or exhibits. Meso-level examines the effectiveness of learning experience, to identify breakthroughs and breakdowns of learning and how learning experience integrates with other related learning experiences. Macro-level examines the impact on school museum visits using new technology and its long-term implications on established educational and learning practice. Each level is analyzed in three stages. Stage one involves data collection on the aim, collection; analysis and documentation of user expectations are captured. Phase two includes the happenings of a particular level and the observations made. Stage three includes examinations of the loopholes between the users’ expectation and the reality (Vavoula et al., 2009).

Myartspace development comprised four broad phases: Requirements analysis to establish the requirements for the system and specify how it would work, designs with regards to the experience and interface of the user and service implementation. It also involves service deployment. Studies have proved that this service enables students to do more explorations while efficiently providing resources for adequate reflection back in the classroom. The website interacts with three digital objects: a museum, class, and private student and teacher stores. The museum maintains museum stores; class stores are kept by educators and lecturers, while students and teachers maintain personal stores at a personal level. It also hosts galleries that can be viewed by others after the creation of digital objects similar to those of a PowerPoint presentation (Vavoula et al., 2009).

2.12 Further Literature

Further research was carried out on Holding Collections and mounting displays, individual development, for example, education and learning, including the use of technologies in this environment, and creating knowledge for, and about society, which was originally thought to fit in to the individual development bracket.

Rather than being about the process of academic or elite research, it is understood to be about public education. It is understand this is an important tool for educating, not on an academic level, although the role of museums is important to academic research, but more about sharing information about the local area, history, exhibits or collections. This is significant in the understanding of how museums can shape identities through access to objects, information, and knowledge in a technological sense.

Further research also lead toa case study at the Gwynedd Museum which looked at a software application that allowed visitors to ‘tag’ objects with their own commentary. The app was tested to see if it increased audience engagement. “The app and related nudging encouraged active participation from those who might otherwise remain silent in a way, offering them a channel that didn’t require them to be social” (Eccles, 2016).

Chapter 3. Design and Development

3.1 Exploring Existing Technology

“Technology in museums is something that is becoming increasingly familiar as curators and designers attempt to harness the latest developments in the field for the benefit of their visitors and collections. And as the use of technology in everyday life has become the norm, integrating this into the museum offer is becoming even more essential” (Murphy, 2015).

Smartphones and smart watches, tablets, and wearable tech have all become everyday items in the lives of much of the population of the United Kingdom. Many visitors to the museum are highly likely to already have on their person tech in some shape or form. Many museums are already aware that they need to engage with visitors in order that they can compete against the many apps and games already feeding individuals information at the touch of their fingertips, but as tech may have some dis-advantages, so it also presents opportunity. Can museums engage with this tech and can they enhance the museum visitor experience, promote education, and interact with visitors like never before and will the visitors’ engagement provide a more meaningful and educational experience when compared to what they are able to do without the augmentation of the interface.

This chapter is to try and establish how technology is already being used, what platforms are already helping shape visitor engagement and what kind of technology can best be used for each of the key types of visitor chosen as subjects with which to design and develop for (learning and discovery, self-fulfilment, social interaction). It is to be established what can be carried forward to the next stage of the study, ultimately being used to implement, test, and try to establish if technology can further enhance the educational visit to the museum. It should also be asked how results can be recorded and how to establish if this design is physically or mentally enhancing the user experience. Can results be used for other areas such as providing useful information about visitors’ actions, and can, in the bigger picture, for example looking at the museum as a whole and not just a single exhibit, the use of technology push prompts to provide a clear path around the museum or provide valuable information to the museum such as recording the time spent at each exhibit or which interaction provided more valuable interactivity?

Mentions should be made to technology that is already providing an interaction and supporting visitors’ learning but due to the scope of this study provides limitations to creating or testing design solutions. Some technology is simply too experimental, or too expensive. Examples include Dynamic Projection Mapping such as ‘Gallery Invasion’ (Skullmapping, 2016) in which visitors’ experience, through the medium of 3D projection, a monkey chasing an aeroplane around a collection of artwork. The visitors need no technology of their own to experience this interaction but this is still very experimental technology and the creation of such an experience would take great skill of which many years of learning would be necessary. Other interactive technology such as multi-touch tables also enable the museum to support the visitors’ learning outcome with a wide range of already available resources like interactive maps, dynamic feedback, videos, gamification, and access to live social media streams. All these resources can be scaled down to be used on a tablet or smartphone but there are cost and availability limitations when considering the multi-touch table solution in the scope of this project.

Re-addressing technology a visitor may already have on their person and considering the resources readily available in the scope of this project turns to research carried out at the Natural History Museum, London, although the research could just as easily have been carried out in the context of a science centre, an aquarium, a gallery or a zoo. Carried out May through June 2015 this study was aimed at adults and subsequently investigated how some use of mobile technologies might affect interactive experiences of adults in a museum environment. Visitors to the museum had to meet three eligibility requirements to be included in the research. They had to be at least 18 years old, speak fluent English, and have on their person a mobile device such as a smartphone or tablet.

When study is carried out in the context of a museum (or a science centre, an aquarium, a gallery or a zoo) mobile learning research has primarily focused on children and student (Chen et al., 2003). At this stage in the study, even though focus has mainly been directed at the educational learning outcomes of children it cannot be ruled out the learning outcomes of adults.

It has been argued that informal science learning settings such as museums have the potential to afford unique opportunities for adults to engage with and learn science (Bell et al., 2009). With the understanding that this research was to be carried out on adults, three questions were developed. What are adults‘ attitudes towards and perceptions of mobile technology use in museums, how do adults naturalistically use mobile technologies in a museum context, and how does it compare to how they use them in their daily lives, and does the prompted use of mobile technologies by adults in this context facilitate an increase in science engagement (Dyson et al., 2016).

It is suggested that the majority of persons use their mobile devices with three specific motivations. These are to capture, to personalise, and to share. Interestingly, preliminary findings in this research at the Natural History Museum suggested that contrary to the results of other studies, mobile devices may not be facilitating higher levels of science engagement in the context of this study, but the capture, personalise, and share concept had an active influence when it was recorded what visitors actually used their mobile devices for suggesting that although the use of the use of smartphones and tablets did not show an increase in the levels of educational engagement, maybe mobile technology did however, have a greater effect on general engagement within the museum.

The results of this study suggest that, even though the key focus was on adults, the project design for visitors from the social interaction type would benefit from allowing test subjects to be able to capture, personalise, and share without necessarily prompting them to do so.

3.2 What technologies will be used?

Possible design solutions are; augmented reality, to map situational knowledge or past exam questions; virtual reality – as an extension to the real museum space; artifact tagging, utilising Bluetooth technology to supply further information pictures, or videos about exhibits; dynamic projection mapping, to bring exhibits to life or map a route around the museum.

Figure 2

The five key visitor types to the museum have been narrowed down to a chosen three, these are: learning and discovery, self-fulfilment, and social interaction. These visitor types have been chosen as they are the visitors that currently frequent the museum more often. Figure 2 above demonstrates this with nearly half the visitors to the museum today visiting for either learning or discovery.

Throughout the literature review it has been suggested that the type of visitor labelled as self-fulfilment is best associated with, but not limited to augmented reality. Therefore, platforms such as Aurasma, Daqri, Metaio, and the Microsoft HoloLens would best suit the design process in this area. These visitors desire to make things more meaningful, challenge abilities, feel sense of achievement, and develop self-knowledge and self-worth. People that visit a museum for learning and discovery also wish to feel a sense of achievement and develop self-knowledge which indicates a very clear connection between the two visitor types. This should be a contributing factor whilst designing a model that would appeal to both. The social interaction of visitors to the museum, and fitting the projects third chosen visitor category desire to share and express their thoughts and feelings through social networks such as Instagram, Tumblr, Pinterest, Facebook, and Twitter, all of which can be triggered through augmented reality, a platform associated with both the learning and discovery, and self-fulfilment visitor types.

3.3 Aurasma

Given that information for each chosen visitor type can be triggered through the augmented reality platform known as Aurasma, this would appear to work well in the scope of this project.

Aurasma has been a forerunner in augmented reality for many years, as their augmented reality platform allows customers to integrate their system into the customer’s own app for the creation of outstanding augmented reality experiences that directs customers to points of sale, landing pages, social engagement channels, and more (Weiner, 2016).

Figure 3

Figure 3 shows how the visitor would use Aurasma to trigger tailored information to the reason behind their visit to the museum. For the full design model and walk-through see Appendix.

Aurasma’s best-in-class web studio for creating, managing, and tracking augmented reality campaigns includes a comprehensive analytics dashboard for views, interactions, clicks, and lots more, making this a great platform for testing if the design model was successful at enhancing the educational outcome to each of the visitor types.

3.4 The Exhibit

The exhibit chosen for this project is the Hellraiser Puzzle Box, otherwise known as the Lament Configuration. The puzzle box bares resemblance to an old Egyptian puzzle cube, contains six sides with opposite sides almost, but not quite identical in detail, and each of these sides has a meaning, albeit made up for the purpose of entertainment. Aurasma requires the object, or in this case, the exhibit to have good detail and a contrast in colours to work effectively, which this puzzle box has. This would make engagement and interaction by the visitor less problematic. Also, as this puzzle box was a creation for a well-known film (Hellraiser) content like video should be readily available.

The box is a mystical/mechanical device that acts as a door, or a key to a door to another dimension or plane of existence (Fandom, 2017). The solution of the puzzle creates a bridge through which beings may travel in either direction across this Schism. The inhabitants of these other realms may seem demonic to humans. An ongoing debate in the film series is whether the realm accessed by the Lament Configuration is intended to be the Christian version of Hell, or simply a generic dimension of endless pain and suffering. This would be a good topic for debate through social media channels and so again link in with a key type of visitor. Using this item as an exhibit will create some limitations such as age concern as the film is certified eighteen and so any images or film clips must be recognised as child friendly of this exhibit was intended for visitors of all ages.

3.5 Limitations

There are other limitations, and some concerns with regards to this project and certain questions have to be answered in order to pursue the best possible outcomes. As mentioned age is a concern. Is this project designed for a particular age group, and if so would this match up with the museum space for which it is intended? Does the exhibit contain adult content? In this case it does contain adult content but as any testing would be done on over eighteens this should not pose a problem.

Technology is also a concern. Where does this stop working effectively? For example, if using Aurasma this requires an active internet connection. Will the museum space provide this or will the effective working of the project rely on mobile technology such as a 4G connection? Dr Malik Mallem pens about some of the problems with augmented reality in his paper on augmented reality, a precise, fast, and robust registration between synthetic augmentations and the real environment is one of the most important tasks for augmented reality. For example, to achieve this for a moving user requires the system to continuously track the user’s position within the environment. Therefore, the tracking and registration problem is one of the most fundamental challenges, which is still open, in augmented reality research today. Especially tracking within outdoors environments is still difficult to achieve even with today’s technology, such as a Global Positioning System (GPS) in combination with relative measuring devices like gyroscopes and accelerometers (Mallem, 2014).

Some technology explored in this project is fairly expensive and some of the software/hardware involved would need a lot of training if it were to be used in some way, therefore confirming that Aurasma would be a good approach as this only requires the user to carry a mobile device such as a tablet or smartphone and have access to an active internet connection.

Testing younger persons could have more rules, ethical barriers, and without approaching testing through the proper channels this could create certain barriers.

Chapter 4. Implementation

Once the decision to create a solution using Aurasma was confirmed and the design model was created it was decided which data sources should be used in order to provide the best possible engagement for each of the chosen user groups. Each of the user groups represents a side of the puzzle cube. A basic information sheet could be supplied either under, or near the exhibit explaining that it is Aurasma ready and what kind of information the visitor could expect with each side of the cube. A QR code could also be present to help users download Aurasma if they did not already have it installed on their mobile device. Once Aurasma is open, holding the device over one side would be for the learning and discovery visitor type and would open educational information such as the puzzle box schematics, how it worked and the history behind it. Holding over another side would be for the self-fulfilment visitor type and would open information to help develop knowledge. In this project it would open a video showing a clip from the Hellraiser movie in which the box is opened and Pinhead, the main character in the Hellraiser series awakens. Holding the device over the final side of the cube would be for the social interaction visitor type and would open a Facebook page, set up to discuss the Lament Configuration exhibit.

Using Aurasma is not as straight forward as first thought. Aurasma works, sometimes. When the trigger image was taken it was ensured a good even light distribution was present, but putting the use of Aurasma in to practice when faced with the exhibit and sometimes it would take a while for Aurasma to recognise the puzzle box and trigger the correct content. Using the masking tool to strengthen the image and tell Aurasma where to focus and where not to focus helped to improve the situation. At one stage parts of the cube were covered by the masking tool and parts of the exhibit were blocked out so Aurasma did not recognize the cube and the required content could not be triggered.

Chapter 5. Critical Evaluation

As this study explores existing state of the art and proposed an idea which delivers an additional or improved solution for the interactive museum space, success should be measured by various criteria. Examples would be, if the idea could be created fully and tested in a real-life museum and how the success of the project could be measured in the scope of this? If this was the case then solutions could have been to use focus groups, questionnaires, social media, and interviews to find out if the results of testing matched initial project goals. As this is not the case the solution can only be evaluated critically.

The goal was to provide three design solutions each with a desired goal to enhance the educational learning outcomes to each of three visitor types in the museum environment. In a way this was achieved, albeit through the use of augmented reality triggering three different end points. The project could have produced a better outcome should three different types of technology have been used. Examples would be using augmented reality to offer the visitor a self of fulfilment, each side of the cube offering up different media such as film, gamification, or a solution to opening the puzzle box. A trigger point such as a QR code or a #hashtag could have been used to open social media channels of the visitors’ choice and let them decide what and where they wanted to share their thoughts. Visitors could have been guided to pages on social media platforms designed to encourage a debate about various aspects of the exhibit. If cost and space was not limited then a multi-touch table would have been a great solution to help the visitors who wished to learn.

Real life testing would have improved the design model of the project as this would have given the project critical feedback which could have been used to then roll the design back, improve on what users did not like or add elements to the design which users may have suggested the design needed. A tried and tested method of evaluating the project would be by following Nielson’s five quality components of usability (Nielsen, 2012) and evaluating if each of these components was considered. These are Learnability, Efficiency, Memorability, Errors and Satisfaction (see Appendix for a full description on Nielsen’s Definition of Usability). Could basic tasks be accomplished the first time a visitor approached the exhibit? This would in part come down to the visitors’ knowledge of their own mobile and device, and if this was sufficient and as long as an active internet connection was available to them then it is believed that basic tasks could be achieved when the exhibit was first approached. A technophobe may not be able to accomplish the basic tasks provided by Aurasma for reasons such as unavailability of a mobile device or lack of knowledge in using a mobile device efficiently. A technophobe may be just as happy reading about the exhibit the same way as they would encounter in the traditional form of the museum.

Aurasma is efficient to use, once the trigger image is recognised. The visitor at this stage. For the most part this project is deigned to self-navigate to the desired information. When visitors re-engage with the exhibit is it easy to remember how things work and would the visitor in fact want to? This would probably depend on the visitor type. A visitor from the social interaction the for example, would want to re-engage with the exhibit if only to see if other visitors had replied or commented on posts the visitor may have made first time around. The visitor would not have to physically visit the exhibit to re-engage with it in this way.

Chapter 6. Further Work

Should this project be taken forward, the first thing that needs to happen is some real-left testing. Only then would the pros and cons of the design model be highlighted. This would result in feedback that could be used to establish areas of study that need to be taken.

During the literature review more case studies should have been analysed. An extension of the literature reviewed would help establish the best recognised practices for implementation of augmented reality. This would also help to eliminate problems from the implementation of a new design model as previous case studies would pin-point difficulties other users may have experienced in similar situations.

If certain limitations could be lifted then this would open the project up to a variety of alternative solutions allowing for a more tailored approach for each of the chosen key visitor types to the museum. An approach could also be taken to include the restoration and passive enjoyment visitor types in the equation. This would lead to offering alternative triggered information and possibly show different learning outcomes when tested.

If expanding on the social interaction within the museum space, not only with this visitor type, but in the space in general, better foundations would result in a more directed approach to the end-point. Information provided could be more tailored to each visitor and this should improve educational learning outcomes when this platform is utilised.

Chapter 7. Conclusion

From the very first literature reviewed through to the goal of designing and implementing a tool to further enhance the educational learning outcomes in the museum visit this project has tried to establish the best practices for visitor engagement and interaction in this space, whilst staying open to new suggestions and alternative technologies.

Museums provide a podium for educational gratification. Acquiring information, using it, sharing it with others and reflecting on it with the aid of technology can help provide a more engaging way to develop knowledge about a certain exhibit or artefact.

Will the knowledge gained be remembered? Without proper testing this is difficult to answer, but past case studies have shown positive results, and with the addition of developing technology such as augmented reality the future of the museum space as a center for learning looks bright.

References

Alvermann, D., Hagood, M. & Moon, J. (1999) Teaching and Researching Critical Media Literacy. Literacy Studies Series. Popular culture in the classroom: Teaching and researching critical media literacy. literacy studies series, 1 (1), .

Ardissono, L., Kuflik, T. & Petrelli, D. (2011) Personalization in cultural heritage: the road travelled and the one ahead. User modelling and user-adapted interaction, 22 (2), 73-99.

Baber, C., Bristow, H., Cheng, S., Heldey, A., Kuriyama, Y. & Lien, M. (2001) Augmenting Museums and Art Galleries. Augmenting museums and art galleries, 1 (1), .

Bell, P., Lewenstein, B., Shouse, A. W. & Feder, M. A. (2009) Learning Science in Informal Environments. Learning science in informal environments: People, places, and pursuits, .

BritainThinks, (2013), Public perceptions of – and attitudes to – the purposes of museums in society. https://www.museumsassociation.org/download?id=954916, Museums Association, .

Chen, Y. S., Kao, T. C. & Sheu, J. P. (2003) A mobile learning system for scaffolding bird watcching learning. Journal of computer assisted learning, 347-359.

Correia, N. & Mota, T. (2010) A multi-touch tabletop for robust multimedia interaction in museums. A multi-touch tabletop for robust multimedia interaction in museums, 1 (1), 117-120.

Dieck, M., Jung, T. & Dieck, D. (2016) Enhancing art gallery visitors’ learning experience using wearable augmented reality: generic learning outcomes perspective. Current issues in tourism, 1 (1), 1-26.

Dyson, L. E., Ng, W. & Fergusson, J. (2016) Mobile learning futures – sustaining quality research and practice in mobile learning. 15th World Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning, mLearn 2016. Sydney, Australia24-26 October, 2016. Sydney, Australia: University of Technology, Sydney.

Eccles, K., (2016), Gwynedd Museum – Audience engagement through technology and nudging. http://happymuseumproject.org/wp-content/uploads/HM_case_study_Gwynedd_v3.pdf, Gwynedd Museum and Art Gallery, .

Falk, J. H. (2009) Jan Packer and Roy Ballantyne. In Anonymous Identity and the museum visitor experience. Left Coast Press, 52-53.

Fandom (2017) Lament Configuration | Hellraiser Wiki | Fandom powered by Wikia. Wikia. Available online: http://hellraiser.wikia.com/wiki/Lament_Configuration [Accessed 5/15/2017 2017].

Hardesty, D. L. (2010) Archaeology – encyclopedia of life support systems volume 2 Singapore: EOLSS.

Kelly, L., (2011), Student Learning in Museums: What do we know? https://musdigi.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/student-learning-in-museums-col-lr.pdf, Sovereign Hill Museums Association, .

Lehn, D. & Heath, C. (2005) Accounting for New Technology in Museum Exhibitions. International journal of arts management, 7 (3), 11-21.

Mallem, M. (2014) Augmented Reality: Issues, trends and Challenges. Augmented reality: Issues, trends and challenges, 1 (1), 1.

Manabe, M. & Lydens, L. (2007) Digital Technology in Japanese Museums. Journal of museum education, 32 (1), 3-5.

Markov, V. (2011) Holography in museums. The imaging science journal, 59 (2), 66-74.

Murphy, A. (2015) Technology in Museums: making the latest advances work for our cultural institutions. Available online: http://advisor.museumsandheritage.com/features/technology-in-museums-making-the-latest-advances-work-for-our-cultural-institutions/ [Accessed 3/12/2017 2017].

Nielsen, J. (2012) Usability 101: Introduction to Usability. Nielsen Norman Group. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability/ [Accessed 5/8/2017 2017].

Noy, C. (2016) Participatory Media and Discourse in Heritage Museums: Co-constructing the Public Sphere. Communication, culture & critique, .

Russo, A., Watkins, J. & Groundwater‐Smith, S. (2009) The impact of social media on informal learning in museums. Educational Media International. The impact of social media on informal learning in museums. educational media international, 46 (2), 153-166.

Simon, N., (2011), ‘What are the most important problems in our field?’, Museum 2.0, : pp. 04/10/2017.

Gallery invasion (2016) Directed by Skullmapping. Skullmapping.

Styliani, S., Fotis, L., Kostas, K. & Petros, P. (2009) Virtual museums, a survey and some issues for consideration. Journal of cultural heritage, 10 (4), 520-528.

Tammaro, A. (2016) Participatory Approaches and Innovation in Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums. International information & library review, 48 (1), 37-44.

Vavoula, G., Sharples, M., Rudman, P., Meek, J. & Lonsdale, P. (2009) Myartspace: Design and evaluation of support for learning with multimedia phones between classrooms and museums. Computers & education, 53 (2), 286-299.

VRS (2017) What is Virtual Reality? – Virtual Reality. Virtual Reality Society. Available online: https://www.vrs.org.uk/virtual-reality/what-is-virtual-reality.html [Accessed 5/14/2017 2017].

Weiner, B. (2016) Top augmented reality platforms, software, and studios – Aurasma. IQ. Available online: http://illusionqueststudios.com/blog/top-augmented-reality-platforms-software-and-studios [Accessed 04/10 2017].

Appendix

Nielsen’s Definition of Usability (Nielsen, 2012)

Learnability: How easy is it for users to accomplish basic tasks the first time they encounter the design?

Efficiency: Once users have learned the design, how quickly can they perform tasks?

Memorability: When users return to the design after a period of not using it, how easily can they re-establish proficiency?

Errors: How many errors do users make, how severe are these errors, and how easily can they recover from the errors?

Satisfaction: How pleasant is it to use the design?

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Learning"

Learning is the process of acquiring knowledge through being taught, independent studying and experiences. Different people learn in different ways, with techniques suited to each individual learning style.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: