Effectiveness of Therapeutic Communities in the Treatment of Self-harm in People with Personality Disorders

Info: 9131 words (37 pages) Dissertation

Published: 17th Nov 2021

Title of Dissertation: ‘Evaluating the effectiveness of therapeutic communities in the treatment of self-harm in people with personality disorders: a systematic review’

Abstract

Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to systematically review both quantitative and qualitative research since 1997 in order to evaluation the effectiveness of therapeutic communities in the treatment of self-harm in people with personality disorders.

Design/methodology/approach – A systematic search with quite narrow inclusion criteria resulted in the review of 9 studies. The studies explored one-day TC’s, residential medium term TCs, residential long term TCs and step-down outpatient programme TC’s. Only peer-reviewed and English-language studies were included in the study.

Findings – Most of the studies were poorly conducted and of low methodological quality due to low sample sizes, lack of blindness rating and low follow up percentages, however the conclusions were that the variety of TC’s examined in the review found TC’s to be effective in the reduction of self-harming behaviours within this population. Some results were mixed and others were inconclusive, especially in the one-day TCs and newly established TC’s. A study with increased methodological rigour found that residential TC treatment was effective in the treatment of self-harm but could only be maintained with combination treatment including residential and step-down TC treatment.

Originality/value – The study provided a broad evaluation of TC effectiveness across a range of TC settings and highlighted that a combination of treatment is superior to residential TC treatment alone. The main finding emphasised the importance of the management of inpatient to community transition for self-harm and other clinical outcomes of people with personality disorder. Recommendations are made for future research in this area.

Research limitations/ implications – Variability in outcomes suggests further research needs to be carried out focussing on the evaluation of intervnetions – how the intervention works = which would play an important role in understanding TC effectiveness in self-harm outcomes.

Keywords – Therapeutic communities, psychoanalytic treatment, self-harm, personality disorders, systematic review, psychosocial.

Paper type – Research paper.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Methodology

Findings

Discussion

Clinical and research implications

Limitations

Conclusions

References

Introduction

Self-harm can be a difficult phenomenon to determine and is easily misunderstood (McAllister et al 2002). For the purpose of this review, self-harm is defined as ‘self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of the apparent purpose of the act (NICE 2004). According to Gregson (2011:503) this can include ‘cutting, burning, biting, head banging, picking and scratching, trichotillomania and over dosing’.

According to McAllister et al (2002), self-harm is a coping mechanism which individuals may use to manage emotional pain or distress. Although it is viewed as a maladaptive coping mechanism (Barker, 2009), health care professionals must still encompass the appropriate skills, training and values required to work with people who self-harm in order to provide them with the appropriate care and treatment.

Although self-injury is a universal symptom, which can be present across psychiatric diagnostic entities, research has shown that self-injury is significantly associated with personality disorder, in particular borderline personality disorder (Chiesa at al 2011). This is not surprising because of the function DSI serves in temporarily relieving negative feelings, regulate emotional storms, ending dissociative states and trying to influence interpersonal transactions, all core features of personality disorder (especially borderline) psychopathology.

The diagnosis of personality disorder is often a contested category and those who attract it can be considered to be difficult patients or untreatable (Lewis and Appleby, 1988 in Norman & Ryrie)

According to Kernberg, the term personality disorder implies patients with borderline personality organisation (primitive defence mechanisms and lack of an integrated identity), low impulse control, severe acting out, negative therapeutic reactions and low motivation for treatment (Kernbers, 1984; Kernberg and Michels 2009 in Vaslamatzis et al, 2014)

The DOH (2003) acknowledges that “people with a primary diagnosis of personality disorder are frequently unable to access the care they need from secondary mental health services”. The poor impulse control, self harm and aggression are highlighted as major burdens to psychiatric sesttings (Jones et al, 2013)

For a chronic condition with a variable course such as personality disorder, it is essential to know if treatment effects are maintained after discharge from treatment (Mehlum et al 1991). This is particularly pertinent in psychodynamically informed treatments, which by addressing the underlying issues of overt behavioural disturbance aim to bring about durable and stable rehabilitative change (Howard et all, 1993) ALL IN CHIESA AND FONAGY 2003.

In the UK, one of the most widespread interventions has been therapeutic community treatment which have provided specialist services for people with personality disorders for over 50 years. Therapeutic community treatment is a form of psychosocial treatment based on a collaborative and deinstitutionalised approach to staff-patient interaction; particular emphasis is placed on empowerment, personal responsibility, shared decision-making and participation in communal activity (Pearce et al, 2016:2)

According to Main (1957), a ‘therapeutic community’ is a community that adopts the culture of enquiry, from both individual and group perspectives, giving particular emphasis to both individual and group anxieties and defences. The emphasis, therefore, in working with these patients is to explore the unconscious processes as well as the conscious processes. Griffiths and Hinshelwood (1990:1) state that anybody working in hospital settings, ‘whether working as staff or there as patients, experience the hospital in both conscious and unconscious terms’.

The continuing psychodynamic input and the provision of a new emotional experience gives opportunity for containment and working through of often severe anxieties to do with separation, abandonment and hopelessness, making possible a further growth of ego functions, which allows patients first to survive the transition and then to progress to a less dysfunctional life, as shown by the marked reduction in self-harm, para-suicide and readmission to psychiatric services (Chiesa et al 2003:12)

Through the application of therapeutic community principles, especially the ongoing exploration of interactions arising in the course of daily life in the hospital, patients are encouraged to take co-responsibility for their own treatment. Rather than being passive recipients, an organised system of daily activities ensures that patients actively assume essential roles in the social functioning of the hospital (Chiesa, Fonagy and Gordon 2009:13)

Confrontations in the here and now concerning patients functioning and behaviour and exploration of their interpersonal ways of relating are central to patient’s resocialisation and rehabilitation. This organisation of treatment constitutes the framework within which patients difficulties, conflicts and ways of relating are expressed, explored and worked through in their multi-faceted interactions with staff and other patients. Features of the residential setting such as the sense of belonging, containment, safety, open communication, involvements and empowerment are components peculiar to the hospital-based setting that are deemed necessary for patients to challenge and modify behavioural responses and affective experiences (Chiesa, Fonagy and Gordon, 2009:14)

One of the main aims of treatment is to help patients realise their social and emotional capacities through individual psychotherapy, psychosocial nursing in the context of the therapeutic community and of patients working together within the framework of hospital lie (Griffiths and Leach 1998 in Pringle and Chiesa (2001).

Through the sharing of domestic and social activity patients are in a position to comment on each others behaviour and attitudes. As patients often share similar problems, they can understand the persons feelings, see the issues involved and can offer constructive suggestions and empathy. Through this mutual process feelings that seemed initially overwhelming become contained and manageable (Irwin, 1995 in Pringle and Chiesa, 2001).

Daily interactions with patients in the milieu of the therapeutic community setting gives rise to close working relationships with patients where thoughts and ideas can be exchanged (Flynn, 1993) in Pringe and Chiesa 2001). Close working relationships can provide patients with an opportunity to work through interpersonal difficulties with the nurse. Psychoanalytic concepts of transference and counter transference are used to understand some of the interpersonal process that occur within relationships between nurses and patients (Pringle and Chiesa, 2001:230)

Although therapeutic communities have a long research history (Broekaert et al, De Leon, 2010), the Cochrane hierarchy of scientific evidence suggests a limited evidence base. Previous systematic reviews have found therapeutic communities to be effective in interpersonal and offending outcomes, substance misuse, crime, mental health and social engagement outcomes (Magor-Blatch et al, 2014; Capone et al, 2016) but they have not explored or evaluated their effectiveness on the outcome of self-harm.

Aims

The aim of this review is to offer a critical analysis of literature evaluating the effectiveness of therapeutic communities in the treatment self-harm in people with personality disorders and question whether the outcomes are influenced by the treatment setting.

Method

The Cochrane Collaboration systematic review methodology, as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins and Green, 2008) and the PRISMA (2009) checklist for Systematic reviews (Moher et al, 2009) were utilised.

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted via online databases.Studies were also identified through hand searching of the International Journal of Therapeutic Communities and snowballing of articles found.

Study selection

Studies must have included participants who had a diagnosis of personality disorder and subject to in patient, day or outpatient settings all based on therapeutic community treatment principles. Co-morbidity diagnoses were excluded as these were not relevant to the aims of this review. Studies including other outcomes (as well as specific to self-harm) such as interpersonal functioning, global functioning, social adjustment and other symptomatic changes were included in the search although had to measure the outcome of self-harm.

Participants aged 18 and over were considered due to personality disorder not being a diagnosed illness to those below 18 years old (reference).

Further eligibility criteria included articles published since 1997 to the current date (2017) due to the limited published research pertinent to self-harm outcomes. For practical reasons only English language studies were considered. Additionally, only peer-reviewed journal articles were included to safeguard the quality of the studies included.

Database selection and search

Three online databases were extensively searched: PsychINFO, CINAHL and MEDLINE. These specific databases were chosen as they all pertinent to health care and nursing practice (Parahoo, 2006:139)

To confine the search specific to the focus of the literature review, relevant key words were selected for the search. Initial key words included: personality disorder, self-harm and therapeutic community. Truncations and synonyms were also used to expand results. Additionally, Boolean operators were used to combine key words, allowing more pertinent articles.

Data extraction

For each study, the following information was recorded and summarised into a table of results: author, date of publication, number, age and gender of participants, percentage of follow up, type of treatment, self-harm outcome measures used and key findings.

Assessment of methodological quality and risk of bias

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) was used as a quality assessment tool to appraise and select the articles chosen for this review. Three different appraisal tools were used due to the varying types of research articles found: randomised control trials, cohort studies and case control studies. These tools included initial screening questions before asking several specific questions relating to the quality of the studies.

Studies were assess for risk of bias with reference to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins and Green, 2008) including selection bias, systematic differences in exposure factors other than the intervention of interest (performance bias), blinding procedures, attrition bias and selective reporting of outcomes.

Results

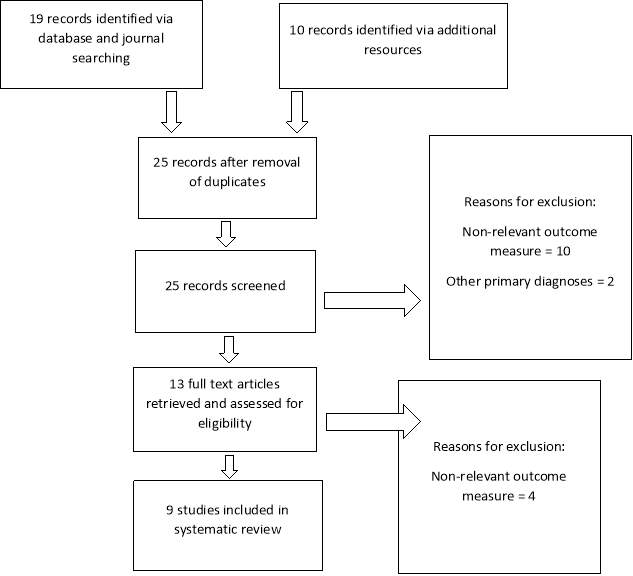

The database search retrieved only 19 studies. 10 additional articles were founds through hand searching journal articles and snowballing of key articles, giving a total of 25 articles after duplicate removal. All studies were screened to produce a sample of nine studies for the review. Eight of the studies chosen for the review were quantitative, which is a fundamental part of health services research (Meadows, 2003). However, the search found one relevant qualitative article which focused on the description and interpretation of personal experiences of therapeutic communities in the treatment of self-harm; making it a reliable source for the review.

Further detail regarding the process of study selection has been presented in a flow diagram as recommended by the PRISMA group (see Figure 1 below) (Moher et al, 2010).

A summary of the design and key results of the nine studies is given below in Table 1 (Moher et al, 2010).

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram of systematic search results

| Primary Author/ Year | Participants | % Follow up | Gender and mean age (years) | Treatment (max duration in months) | Outcome measures (duration in months) *Note: includes only outcome measures that capture self-harm. Other outcome measures used in the studies are not included. | Key findings |

| Lowyck et al. (2015) | 44

Attrition 9 |

80% | M/F 35 | Hospitalisation based psychodynamic treatment for personality disorders (6) | Self-harm inventory (SHI) (intake, 6, 12, 60) | Repeated-measures ANOVAS showed a significant effect from intake to 5 year follow up on self-harm, F(1.33) = 8.48, p=.01, as measured with the SHI total scale. Further pairwise t tests showed a significant difference between the SHI at intake and discharge, t=3.10, df =34, p=.004; 1 year posttreament, t=2.81, df=33, p=.008; and 5 years posttreatment, t=3.26, df=34, p=.003. |

| Warren et al. (2004) | Admitted 75

TAU 60 |

36% | NR 28 | Specialist therapeutic community treatment for personality disorders (6.7) | Multi Impulsivity Scale (MIS) (admission, 12) | Standard deviation of impulse of self-harm in admitted group at baseline was 3.27 and 2.43 at follow up. In impulse of self-harm in TAU group, baseline was 2.85 and 2.58 at follow up. Standard deviation of action of self-harm in admitted group at baseline was 2.41 and 1.77 at follow up. In action of self-harm in TAU group, baseline was 2.19 and 2.04 at follow up. |

| Bateman and Fonagy (2001) | 38 | 100% | Partially hospitalised M/F (30.3)

Control M/F 33.3 |

Partial hospitalisation consisting of long-term psychodynamically orientated treatment for patients who suffer from Borderline personality disorder (18) | SHI (18, 24, 30, 36) | At end of treatment phase, significantly more BPD patients who completed partial hospitalisation programme than control group patients had refrained from self-mutilation in the preceding 6 months (p.<0.005) (Fisher’s exact test). Also, significantly more partial hospitalisation patients than control group patients reported not engaging in self-mutilation after 24 months (90.9%) versus 36.8%; 30 months, 81.8% versus 31.6% and 36 months 77.3% versus 31.6%. |

| Bateman and Fonagy (1999) | 38 | 100% | Partially hospitalised M/F (30.3)

Control M/F (33.3) |

Partial hospitalisation consisting of long-term psychodynamically orientated treatment for patients who suffer from Borderline personality disorder (18) | SHI | Median of self-mutilation (per 6 month period) in partially hospitalised group was reduced from 9-1, whereas in the control group over the same period, the change was from 8-6. The trend test was highly significant for the partially hospitalised group (Kendall’s W=0.21, x2 =11.9, df=3, p.<0.008) but not significant for the control group (Kendall’s W=0.005, X2=2.4, df=3, n.s.). Group differences in the number of attempts of self-mutilation emerged by 12 months and the number of individuals no longer self-mutilating was significantly greater by 18 months in the partially hospitalised group than in the control group (x2=7.0, df=1, p.,0.008). |

| Chiesa et al (2004) | 49 Inpatient programme

45 step-down programme 49 general psychiatric group |

M/F (31.5)

M/F (32.5) M/F (34.5) |

Long-term inpatient programme involved a psychoanalytically orientated residential specialist programme expected to last 12 months with no outpatient follow up assessment. Step-down programme was expected 6 month inpatient stay following 12-18 months of outpatient group analytic psychotherapy and 6-9 months of outreach nursing. In the general psychiatric group, patients received standardised general psychiatric care. | A structured interview, modelled on the SHI was applied at intake, 12 and 24 months to obtain details of self-harm episodes. | The number of patients who engaged in at least one episode of self-mutilation decreased markedly by 12 and 24 months in the step down sample, whereas it increased at 12 months in the step-down sample, whereas it increased in the general psychiatric group by 24 months. The hierarchical logistic regression showed that the model including self-mutilation the year before intake and group status was predictive of self-mutilation at 12 months (x2=60.48, df=3, p.,0.001) with membership in the inpatient programme contributing to the prediction (B=1.91, [SF=0.59], df=1, p.,0.002). Similarly, prediction self-mutilation at 24 months from the covariates and group membership yielded a highly significant model (X2=45.07, df=3, p<0.001). | |

| Chiesa et al (2004) | 39 Inpatient programme

34 step-down programme 38 general psychiatric group |

49%

59% 52% |

M/F (31)

M/F (34) M/F (34) |

Long-term inpatient programme involved a psychoanalytically orientated residential specialist programme expected to last 12 months with no outpatient follow up assessment. Step-down programme was expected 6 month inpatient stay following 12-18 months of outpatient group analytic psychotherapy and 6-9 months of outreach nursing. In the general psychiatric group, patients received standardised general psychiatric care. | A structured interview, modelled on the SHI was applied at intake, 12 and 24 and 72 months to obtain details of self-harm episodes. | Episodes of self-mutilation at intake of inpatient group was 19, step-down group 17 and general psych group 20. At 12 months, episodes of self-mutilation in inpatient group increased to 26 but reduces to 11 in step down and 14 in general psych group. All groups had decreased rates at 24 months (17, 10, 16) however at 72 months, episodes remained stagnant in inpatient group (17), reduced again in step-down group (9) and increased significantly in general psych group (23) |

| Barr et al (2010) | 20 | 26% | M/F (35.15) | Once weekly therapeutic community day treatment for people with personality disorders (12) | SHI (intake, 3, 6, 9, 12) | Baseline mean/median 2.40 and follow up 2.05. Observed changes in patterns of self-harm and service use failed to reach significant levels but was suggestive of possible underlying improvements. Although percentages fluctuated at different intervals the main findings of self-harm outcomes were: cutting went from 55% at baseline to 50% at follow up; Scratching went from 40% at baseline to 20% at follow up; preventing healing went from 35% at baseline to 40% at follow up and overdose went from 25% at baseline to 20% at follow up. |

| Hodge et al (2010) | 51 | 100% | NR | Once weekly therapeutic community day treatment for people with personality disorders (12) | Semi-structured interviews (analysed thematically). One at time of joining service and another at 12 months. | TC has enabled patients to understand the relationship between emotional state and their urge to self-harm which may have an impact on their behaviour. Patients report that they may continue to self-harm during treatment but responses of the group to this have helped confront possible consequences. Other patients report that they stop self-harming during treatment but restart after discharge. |

| Pearce et al (2016) | 70

Control group (35) Intervention group (35) |

NR | M/F (33.4)

M/F (34.6) |

Democratic therapeutic community treatment for people with personality disorders (18) | Frequency of suicidal acts and acts of self-harm collected via a self-report questionnaire developed specifically for the study (based on SHI). | Overall, DTC treatment is superior to TAU in reducing self-harming behaviours. Acts of self-harm at baseline in TAU group was 3, and remained at 3 at 24 month follow up whereas in DTC group acts of self-harm at baseline were 2 and 4 at 24 month follow up. |

Methodological quality of results

All but one of the studies resulted in several ‘can’t tell’ or ‘no’ answers to the quality assessment questions asked in the CASP checklists which indicated a high risk of bias within the majority of the studies included in the review.

In Chiesa et al’s (2004) study, there were more ‘yes’ answers which indicated a more robust study design and reduced risk of bias. Study results are considered in relation to possible sources of bias examined by the quality assessment tool.

Demographic characteristics of participants in the studies included

The participants were mainly recruited from patients already in treatment in various therapeutic communities. Other participants were recruited via psychotherapy referrals, patients referred to TC treatment by the referring clinician but weren’t accepted into inpatient TC treatment and patients with personality disorders but not receiving TC treatment.

All studies included both female and male participants. Their mean age ranged from 28-35.15 years and in all but one study, the majority of the participants were female. The reason for this could be that females with personality disorders are more likely to evidence their distress in self-mutilating and other self-harming behaviours whereas men are more likely to present with substance muisuse problems and antisocial behaviours. Additionally, women are more likely to seek out and utilise pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy services (Sansone and Sansone, 2011).

Risk of bias existed within some studies due to small sample size (REFERENCE STUDIES) and subjective assessments of personality disorder symptoms (again reference studies). Some studies included patients who had been re-tested and assessed who were more likely to have been in treatment longer and who had therefore received more care and support (include refs)

Control and comparison groups

In Chiesa et al’s 2004 study, all groups were subject to the same inclusion/ exclusion crtieria. Results from this study have greater specificity due to increased comparability of participant groups, in addition to two multiple group contrasts; two additional treatment groups (TAU, residential TC plus step-down treatment.

Characteristics of TC programmes used in the studies

All studies incorporated the main therapeutic community principles: sense of belonging, safety, openness, participation and empowerment (Haigh, 1999). Although the treatment programmes differ in each study, most incorporated an intense weekly programme consisting of: group analytic therapy, individual psychotherapy, daily community meetings, activity groups, non-verbal therapies such as art therapy and movement therapy, individual meeting with nurses and psychosocial activities.

The control/ comparison groups included in some of the studies received very little input from services and professionals in comparison to the treatment as usual groups. Their treatment programme included very basic input consisting of monthly reviews by a psychiatrist, fortnightly follow up from community psychiatric nurses and psychotropic medications.

The length of treatment varied between studies with most having around 12 months.

Findings

Although all studies explored other outcome measures relating to the effectiveness of therapeutic community treatment in people with personality disorders, the findings below focus on the outcome of self-harm only. All but one of the studies used the Self-Harm Inventory (SHI) to assess the outcome of self-harm. This measure incorporates a 22 item self-report scale used to assess the extent to which patients report engaging in various self-harming behaviours. Several previous studies have supported the reliability and validity of this tool (Lowyck et al, 2015).

In Warren et al’s (2004) study, the Multi-Impulsivity Scale (MIS) was used to measure outcome of self-harming (impulsive) behaviours. This scale includes a checklist of impulsive feelings and behaviours which is similar to the SHI, again including a 22 item self-report questionnaire where 11 questions address the frequencies of impulses towards particular actions and 11 address the frequencies of these actual actions.

In Hodge et al’s (2010) qualitative study of mixed methods findings of once weekly therapeutic community day services for people with personality disorders, semi-structured interviews around self-harm and risk were carried out between service users, service user consultants, former service users, staff and referrers. The majority of interviews were carried out with current service users. Although these interviews weren’t measurable, they were able to support the clinical findings in the quantitative paper of the same study (Barr et al, 2010).

Within subjects TC comparisons

Barr et al (2010), Hodge et al (2010) and Lowyck et al (2015) used a within-subjects design to measure outcomes of self-harming behaviours within a therapeutic community setting.

In Barr et al’s (2010) study, changes in the functioning of service users who attended the day therapeutic community services were assessed every 12 weeks up to a year. They found substantial developments in both the mental health and social functioning of service users however changes in patterns of self-harm were indicative of possible underlying improvements but failed to reach noteworthy levels.

The overall finding was that self- harm did not dramatically reduce over the duration of treatment.

They did however find a minor decrease in overdose although there was self-mutilation and prevention of healing showed a minor increase. Though low sample numbers at the short-term assessments hamper interpretation of these quantitative results, their qualitative findings show a more positive interpretation of the impact of one-day therapeutic communities on self-harming behaviours in the longer term.

Nonetheless, observed changes were limited, perhaps because an engrained ‘coping mechanism’ like self-harm is very resistant to change in the short term (Barr et al, 2010).

Hodge et al, (2010) found that service users had noted that the TC had enabled them to understand the connection between their emotional wellbeing and their urge to self-harm which may have an impact on their behaviour. Service users conveyed that a more open approach can help them to address their self-harm by motivating them to be seen not to be self-harming.

Many service users noted that self-harm remains a continuing problem they have to battle with. So although they have developed a deeper understanding of the reasons behind their self-harm, this is not always enough to impact dramatically on the behaviour itself (Hodge et al, 2010).

It appears, then, that one day therapeutic communities are perhaps unsuccessful in the treatment and reduction of self-harm however they are able to create an environment in which group members are encouraged to understand better why they self-harm and are encouraged and supported to develop approaches for reducing their dependence on it as an identified coping mechanism (Barr et al, 2010; Hodge et al, 2010).

In Lowyck et al’s (2015) study of 5 year follow up findings of a psychodynamically oriented hospitalisation based treatment for patients with personality disorders, found that improvement in symptoms and general functioning was maintained during the follow-up period.

Pairwise t tests showed a marked difference between the SHI at intake and discharge; 2 year post treatment and 5 years post treatment. Taken together, these findings show that there was a substantial improvement in symptomatic functioning from intake to discharge and that this improvement was sustained during the 5 year follow up period (Lowyck et al, 2015).

The findings of the study provide further support for increased positivity concerning the effects of intensive psychotherapy (as part of a therapeutic community programme) for people with personality disorders. Additionally, about 60% of patients moved from the dysfunctional range to the normal range between intake and 5 year follow-up in terms of symptom severity (including self-harming behaviours). Although more research is required to repeat these findings, continued improvement in symptoms is remarkable and is likely to have a significant impact on the daily functioning of these individuals (Lowyck et al, 2015).

TC compared with no treatment group

Pearce et al (2016) undertook an RCT of 70 people meeting DSM IV criteria for personality disorders. The intervention was therapeutic community treatment and the control condition was crisis planning plus treatment as usual (TAU). For the purpose of this review, treatment as usual groups are considered as a ‘no treatment group’ as it doesn’t include any kind of specialist treatment specific to people who self-harm or have a diagnosis of personality disorders.

In this study, outcomes were measured at 12 and 24 months after randomisation. At 24 months, self- and other directed aggression were significantly improved in the TC compared with the TAU group. The TC group showed significant advantages over the TAU group in aggression and self-harm measured by the modified overt aggression scale (Pearce et al. (2016).

In Bateman and Fonagy’s (1999) study, they found that patients who were partially hospitalised (in a setting based on TC principles) showed a statistically significant reduction on all measures in contrast to the control group (standard psychiatric care) which presented limited change or worsening over the same period. An improvement in depressive symptoms, a reduction in suicidal and self-mutilatory acts began at 6 months and continued until the end of treatment at 18 months (Bateman and Fonagy, 1999).

The number of occurrences of self-mutilating behaviour lessened throughout the duration of treatment in the partially hospitalised group but remained persistent in the control group. In the partially hospitalised group, the median number of self-mutilations per 6 month period was reduced from 9 to 1 whereas in the control group over the same time period, the change was from 8 to 6 (Bateman and Fonagy, 1999).

In their follow up paper, Bateman and Fonagy (2001) found that patients who completed the inpatient programme not only preserved their significant gains but also showed a statistically substantial continued improvement on most measures in contrast to the patients treated with standard psychiatric care who showed only limited change in the same period.

At the end of the treatment phase, significantly more patients who completed the partial hospitalisation programme (N=13) had abstained from self-mutilation in the previous 6 months (p<0.005, Fishers exact test). In addition, significantly more partial hospitalisation patients than control group patients reported not engaging in self-mutilation after 24 months (90.9% [N=20 of 22] versus 36.8% [N=7 of 19] (Bateman and Fonagy, 2001).

Warren et al (2004) undertook a study where comparisons were made within and between groups of patients admitted (n=75) and not admitted (TAU N=60) to a residential therapeutic community for treatment of personality disorders. Assessment of a range of impulsive feelings and behaviours was made at referral and one year follow up. Substantial reductions were found in the treatment group for both total impulsive feelings and total actions. Exceptionally significant differences were also found between change scores for the admitted and treatment as usual groups for both impulses and behaviours.

For the admitted group, there were substantial and significant differences found for both impulses and behaviours. Improvements were statistically significant for the impulses and the actions of hurting the self. Change was irrelevant on the total scores for impulses and actions in the treatment as usual (not admitted) group (Warren et al, 2004).

It is important to highlight that some areas of impulsivity changed more than others in the admitted group and that this was not the case for the treatment as usual comparisons. Ten of the 22 items examined in the study showed marked variations in the admitted group. Generally, these ten included both the impulse and action elements of individual items so that the primary areas which showed change following therapeutic community treatment were binge eating, hitting others or smashing property, hurting the self and overdosing. Some of the biggest changes were apparent in behaviours that would be considered under then generic umbrella of self-harm: hurting oneself and taking overdoses (Warren et al, 2004).

TC compared with another treatment group

Chiesa et al (2004) conducted a study to compare the effectiveness of three treatment models for personality disorders. The three groups consisted of an inpatient group (admitted to a therapeutic community), a step down programme group (patients receiving outpatient therapeutic community treatment) and a general psychiatric group (patients receiving basic psychiatric input).

They found that by 24 months, patients in the step down programme indicated substantial improvements on all measures, patients in the long term inpatient programme showed no changes in self-harm or attempted suicide and patients in the general psychiatric group showed no improvement on any variables except self-harm and hospital readmissions (Chiesa et al, 2004).

The number of patients who engaged in at least one episode of self-mutilation reduced distinctly by 12 and 24 months in the step down sample, whereas it increased at 12 months in the inpatient group and somewhat reduced in the general psychiatric group by 24 months (Chiesa et al, 2004)..

The odds ratios discovered that patients in the step down programme were three times less likely to self-mutilate by 24 months, while involvement in the inpatient programme group predicted a 1.5 increase in self-mutilation (Chiesa et al, 2004).

The overall results showed that a step down programme involving a medium term inpatient stay in a psychosocial therapeutic setting followed by long-term outpatient group psychotherapy and support in the outside community attained substantially further improvement on a number of standardised and clinical outcome measures than long term specialist inpatient treatment alone with no outpatient follow up or general psychiatric organisation (Chiesa et al, 2004).

In their follow up paper, Chiesa et al, (2006) conducted a six year follow up of the previous paper. Again, the Self-Harm Inventory (SHI) was used and applied at intake, 12, 24 and 72 months to elicit self-mutilation episodes and suicide attempts.

They found that the distinct reduction in the number of patients in the step down programme that committed acts of self-mutilation and parasucide by 12 and 24 months was retained at 72 months follow-up (Chiesa et al, 2006).

Rates of self-mutilation reduced from 50% to 29% by 24 months and to 27% by 6 year follow up, in the step down programme. Self-mutilation rates did reduce in the long term inpatient programme but not as considerably as in the step down programme (Chiesa et al, 2006).

Discussion

Overview

The findings from the studies indicate that on the whole, therapeutic community treatment appears to be effective in the treatment of self-harm in people with personality disorders. There are however, varying degrees of effectiveness due to differences in duration of TC treatment, type of TC treatment and the different components of TC treatment.

Length and duration of treatment

In Barr et al’s (2010) study of one-day TCs, they found little improvement on self-harm outcomes. The short and minimal intensity of this therapeutic community programme may have been responsible for these results. There remains considerable discussion around exactly who within the wide-ranging personality disorder population needs further intensive input than a once weekly therapeutic community programme can offer (Barr et al, 2010)

Kennard and Roberts (1983) note that patients in a therapeutic community are encouraged to engage in frequent group meetings which allow patients to talk about their thoughts and feelings in a safe space, amongst other patients and staff which can help to refrain from acting impulsively on these thoughts and feelings.

For people with personality disorders which such a fragmented sense of self and trust issues, they require time and space to be able to develop relationships in order to be able to truthfully express how they feel which further evidences the need for consistent and longer treatment.

As relationships develop with the therapeutic milieu, patients are able to then confide in each other and are able to express their concerns for one another. It is when this concern about one another is expressed that patients are able to then identify with a more caring attitude towards themselves (Day and Pringle 2002:50).

However, although long term inpatient therapeutic community programmes have proved to be successful in the reduction of self-harming behaviours, the length of inpatient stay should not be excessive. Excessive hospitalisation may cause patients to become somewhat institutionalised and dependant on the environment and the staff and patient group. (Chiesa et al, 2004).

Type of TC treatment

Difference in type of TC treatment showed variations in the outcome measures pertinent to self-harm. Barr et al, (2010) found that the once weekly TC treatment was aimed more at helping people to engage with services and to keep safe generally rather than providing specific care and treatment towards self-harming behaviours which indicates why there was minimal change in the outcome of self-harm within this group. Barr et al (2010) suggest that significant change in self-harming behaviour would be more likely in a service devoted to this specific goal.

Chiesa et al, (2004) found that although medium term inpatient stay in a therapeutic community was effective in the reduction of self-harming behaviours, greater and sustained reduction would be more prevalent if it were followed by long term outpatient group psychotherapy and support in the external community. They added that specialist inpatient treatment alone would not be effective in long term maintenance of reduced self-harm and other clinical outcomes.

They also noted that substantial reduction in self-mutilating and parasuicidal behaviours in the step down group was an indication that continuing therapeutic community/ psychosocial treatment in the community plays an important part in assisting patients make the transition between hospital and community life (Chiesa et al, 2004).

Further evidence from Chiesa et al’s (2004) study suggests that providing a long term outpatient specialist psychosocial aftercare programme seems to shield patients from the typical anxieties connected with discharge from hospital, which in turn allows them to better face the challenges of reconnecting to community life without breaking down or reverting to previous maladaptive coping mechanisms such as self-mutilation and other self-harming behaviours.

In their later follow up study, Chiesa et al (2006) note that the key factor in sustained improvements and recovery in these patients is how they are managed in the boundary/ transition between inpatient and community life.

Different components of TC treatment

Bateman and Fonagy (1999) noted that the vast amounts of staff time received by the partially hospitalised patients may be responsible for their improvement although the control group received large amounts of staff attention through hospital admission, nonpsychoanalyyic partial hospitalisation and extensive outpatient support.

These patients often express the inability to cope with their own feelings without some kind of assistance which then leads to a spilling over of these feelings onto others. Casement (1986) notes that this spilling over, or incapacity to contain, as an unconscious communication to others that there is something amiss, something that is unmanageable without help. He adds that the ongoing help being searched for is always for an individual to be available and accessible to help with these difficult feelings (Casement, 1986).

The amount of staff time desired by and given to patients may indeed influence their outcome of improvement (including clinical outcomes such as self-harm) however in order for the treatment to be effective in the long-term and for patients to maintain a sense of well-being then a healthy balance needs to be struck between support and individual responsibility (Bateman and Fonagy, 1999).

Pearce et al (2016) support this by adding that a key function of therapeutic communities is that they place an emphasis on peer support and challenge. Whilst promoting a sense of belongingness to patients which in turn has an independent effect on wellbeing and health, the mutual promotion of responsibility allows favourable effects on impulsivity, self-efficacy and the ability to make good choices.

It is believed that real responsibilities (and accountabilities) offer opportunities for both success and failure. The creation of a safe supportive environment, in which patients can experience4 failure and disappointment, as well as success, is an important part of the work with patients in that it offers reparative possibilities (Griffiths and Hinshelwood, 1994).

Within the psychosocial milieu, there is an emphasis on three particular aspects: responsibility, reparation and self-esteem (Griffiths and Hinshelwood, 1994).

Bateman and Fonagy (1999) added that they found the following as essential components of an effective treatment programme for treating people with personality disorders: a theoretically comprehensible treatment approach; a relationship emphasis and a consistent application of these over a period of time. This then allows examination of inconsistencies in the relationship patterns of patients with personality disorders (particularly borderline) and identification with unconscious influences that may hinder the possibility of change.

These unconscious influences, mainly derived from infancy, are often what drives the destructive and more difficult aspects of the self. Malan (2007:15) states that ‘human beings adopt various defensive mechanisms in order to avoid mental pain or conflict to control unacceptable impulses’. He adds that destructive and maladaptive behaviours such as self-harm are often the end product of these defence mechanisms.

The quantitative findings from this study (Barr et al., this issue) indicate statistically significant improvements in the mental health and social functioning of service users. The findings reported here offer some insight into the dynamics at work in one-day TCs that may play a role in these improvements.

Barr et al (2010) found that one of the main beneficial features of being in a one- day TC seemed to be the value gained from shared experience. This mirrors similar findings in various other studies. Sharing experiences amongst fellow peers with similar experiences and difficulties can help to validate those experiences and lessen feelings of shame and isolation.

Shared experience and developing relationships within the community also provides the basis for the development of secure attachment (Haigh, 1999; Kennard and Roberts 1983; Bowlby, 1977). Through developed trust, individuals can begin to participate more openly with the group, gaining insight into themselves and an improved awareness of how they relate to others. This gained insight into themselves and how they relate to others is key in supporting the reduction of harmful behaviours.

Warren et al (2004) also found that effective treatment in the TC is achieved via the working through and internalisation of the experiences relating to such integration, exploration and experimentation. He does however suggest that additional exploration of the influence of treatment on impulsive and self-damaging behaviours in PD, including an identification and description of therapeutic processes and key features of treatment needs further research and investigation.

Very great emphasis is therefore placed on the support and supervision of nursing staff. Nurses can hold on to hope and hopefulness only if they can own and contain their own omnipotent phantasies of absolute cure and its converse: total impotence of failure (Griffiths and Hinshelwood, 1994). Only supported and contained staff can provide the interpersonal medium required to achieve therapeutic change and transformation in patients.

Through the process of psychosocial practice, nurses mediate the connection between earlier experience and present-day experience and promote the possibility for change and growth (Griffiths and Hinshelwood, 1994).

Clinical and research implications

Although there is some variability in treatment populations included in the review, evidence reported in other publications suggest that individuals with personality disorders who engage in self-harming behaviours will benefit from TC treatment.

The weight of evidence gleaned from multiple sources of research including randomised control trials and field outcome studies, suggests that TCs are an important and effective treatment for patients in improving some features of their illness/ pathology – specifically mental health and social engagement and in reducing harmful behaviours. Variability in treatment setting and populations reflect the real word setting in which TC treatment is delivered, providing a multifaceted treatment modality to a complex population in variable circumstances.

A large proportion of studies harboured numerous methodological limitations such as limited use of binding, randomisation and follow up periods which may have been responsible for the mixed findings of self-harm outcomes in the available studies.

Chiesa et al’s (2004) study harboured a heightened methodological rigour, findings suggest that whilst residential TC treatment is effective in reducing self-harm outcomes, these can be enhanced by further treatment in the community, for example in a step down group based on the principles of TC treatment. Although enhancements may be evidenced during treatment, it is important to explore the evidence around post treatment and measure whether outcomes improve or decrease.

Future research should consider adopting a focus on the processes inherent within TCs to develop an evidence based understanding of its most effective components so we might enhance their aspects. As highlighted, in light of the continuous modification of TCs and ongoing therapeutic integration of different theoretical approaches, gaining a deeper understanding of how TCs work would also enable future clinicians to approach TC modification with an understanding that would guard against undermining the core integrity of the model.

Limitations

This review should be interpreted with reference to its limitations. Participants were included from a range of different TC settings, therefore comprehensive comparisons were unable to be made clearly between the different studies. The very limited research in this area made it incredibly difficult to pinpoint the features of therapeutic communities that were actually responsible for change in outcome.

Because the study specifically evaluated studies that were peer-reviewed, it may make the study highly vulnerable to risk of publication bias. A suitable suggestion would be that future researchers could try to access unpublished studies as well as considering grey literature.

Most of the studies included non-randomisation allocation of patients and the majority of patients had been referred to therapeutic community settings for psychotherapeutic treatment. It could be argued then that patients were selected on the basis of their potential for responsiveness (Chiesa et al, 2004)

Many studies included a low sample size and a loss in participants at varying follow-up points (Bateman and Fonagy, 1999; Barr et al 2010; Pearce et al, 2016). Additionally, study designs adopted in the studies didn’t permit in-depth exploration of the therapeutic processes taking place in the groups which may have impacted on the therapeutic outcomes (Hodge et al, 2010).

Chiesa et al (2006) noted that further treatment between anticipated end of original treatment programme and 6 year follow up assessment may have influenced outcome. This was a similar finding in other studies.

Differences in age of settings also varied which may have influenced outcome. For example, in Barr et al’s (2010) study, half of the TC’s in the study were mature and longer running and the other half were undeveloped and newly established.

Conclusions

The strength of the current study is that it examined a variety of therapeutic community settings focussing on the treatment of self-harm in people with personality disorders (one-day, long-term inpatient, outpatient) however, as various other outcome measures were explored in the studies it made the studies less valuable.

The findings suggest that that TC treatment is generally effective in the treatment of self-harm with people with personality disorders, however the evidence failed to pinpoint where the improvements where coming from in relation to the overall treatment. What exactly is it that makes TCs effective in this outcome measure?

Further studies using adopting qualitative methods from both patient and staff perspectives are crucial in order to increase understanding in therapeutic community treatment efficiency in the treatment of self-harm of people with personality disorders.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Mental Health"

Mental Health relates to the emotional and psychological state that an individual is in. Mental Health can have a positive or negative impact on our behaviour, decision-making, and actions, as well as our general health and well-being.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: