Types of Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism

Info: 10978 words (44 pages) Dissertation

Published: 25th Jan 2022

Tagged: CriminologySecurityTerrorism

II. Agenda Item: Hybrid Approach to Counter Terrorism: Combining Strategies

Today, security in our daily lives is more important than it ever was before due to threat of terror coming from various entities, ideologies and motives. Although most people became familiar with terrorism after the attacks on World Trade Centre on US soils back in 2001, terror was present in the lives of people decades before the 9/11 attacks. But undoubtedly it is fair to assume that the attacks on twin towers has changed the perception of world on dealing the issues of terror. Today, terror has taken various forms to adopt itself on the environment it plans to terrorize. The rise of the Islamic State has taken counter-terrorism to a next level.[i]

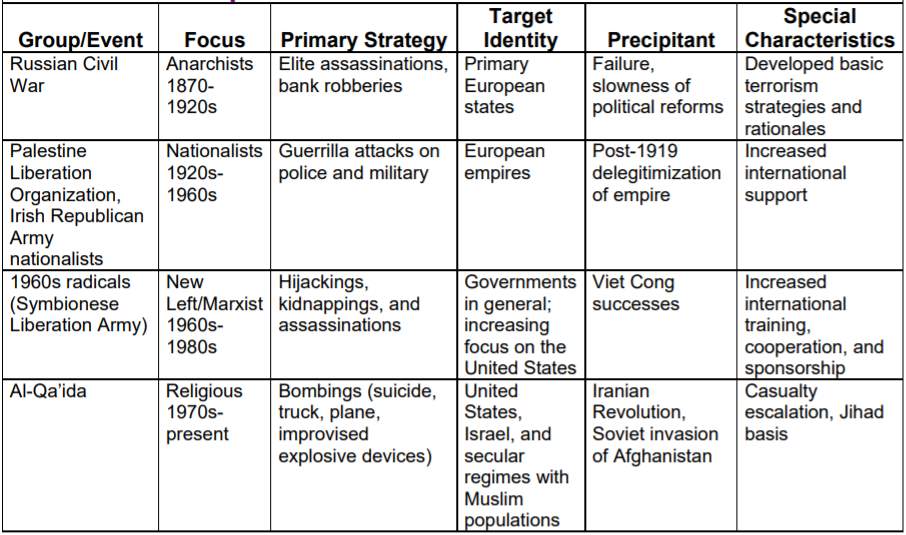

Figure 1: Historical Examples of Terrorism[ii]

National governments and international organizations have adopted different doctrines and approaches when dealing with the issue. Academic research done by governments and researchers have categorized the approaches on counter-terrorism into two where the delegates of this committee will be challenged to complement the two with each other and be tasked to provide an integrated hybrid approach to resolve the issue.

III. Definitions and Terminology

A. Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism

Terrorism is the illegal exercise of violence, often motivated by political, religious, and other ideological beliefs to instill fear and coerce states and communities with the aim of achieving political objectives.[iii] Counter-terrorism on the other hand is the operations and policy implementations being followed, to eliminate terrorist organizations, their manpower, and established networks to render them unable to use violence to achieve their objectives.[iv]

There are three main types of CT activities: advice and assist activities; overseas CT activities; and support to the activities of civil authorities.[v]

- “Advise and Assist Activities are the military efforts to improve the ability of other nations to;

- provide security for its citizens

- govern, provide services, and prevent terrorists from using the territory of the nation as a safe heaven

- promote long-term regional stability.

- ‘Overseas CT Activities’ include: offense, defence, and stability operations; counterinsurgency operations; peace operations; and counterdrug operations.

- ‘Defence Support of Civil Authorities’ includes support to prepare, prevent, protect, respond, and recover from domestic incidents including terrorist attacks, major disasters both natural and man-made, and domestic special events”.[vi]

B. Difference between Counter-Insurgency and Counter-Terrorism

According to US Army is defined as “organized movements aimed to overthrow a constituted, elected government through the use of subversion and armed conflict”.[vii] When the insurgency and terrorism is compared, it can be concluded that terrorism is more complex in its nature. It is fair to say that every insurgent group employs terrorism as a way to achieve their objects. But terrorism has many different forms on its own. And counterinsurgency (COIN) is more likely to be subordinate to CT doctrines.

C. Violent Non-State Actors and State-Sponsored Terrorism

1. Violent Non-State Actors

Non-state actors are “non-sovereign entities that exercise significant economic, political, or social power and influence at a national, and in some cases international, levels”.[viii] In this regard, a Violent Non-State Actor (VNSA) is a group of militants that exercises legally unauthorized use of violence to achieve its objectives.[ix] In politics and international relations, terrorist organizations fall under this category because the designation of an organization as a ‘terrorist group’ is a complicated political issue which could be best described by a famous quotation from Gerald Seymour: “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter”.[x]

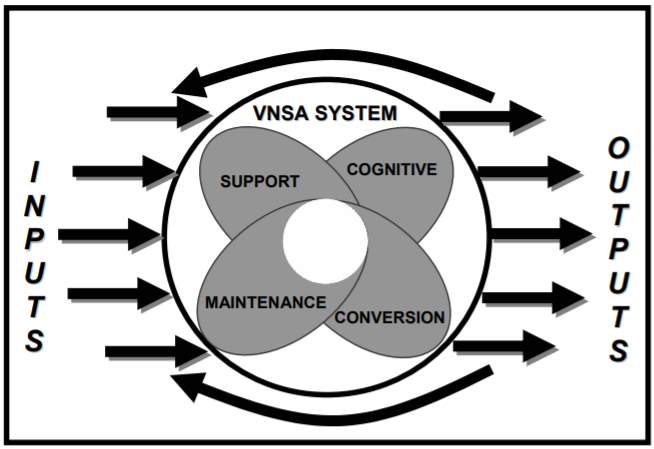

To have a better understanding of the issue, the VNSAs could be best analysed on three levels: environment, organization, and internal elements.[xi] Figure 2 depicts these three by showing a system consisting them altogether in an environment which they exchange energy and information.

Figure 2: Environment[xii]

As a result, these groups could be perceived as basic organic forms of life. They grow, adapt, spawn, and ultimately die. For any VNSA to sustain its functions, it must constantly adapt and improvise to changes in the security environment. This also includes adaptation to the changes made by the sovereign-state the group is fighting against.[xiii] Most of the times, this illustrates a clear separation of inputs and outputs of a VNSA. Inputs are sources for political motives, manpower, and resources available. On the other hand, results of combining these inputs in a systematic manner of violence is the outputs.

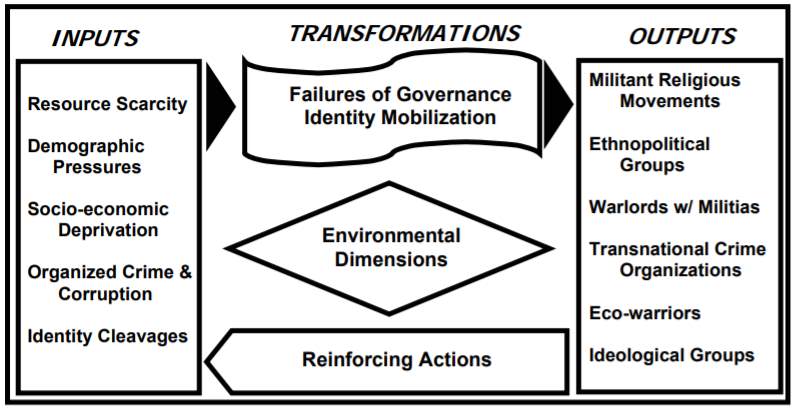

Figure 3: Transformations of Inputs and Outputs[xiv]

This environmental analysis pinpoints major inputs and outputs, thereby illustrates the transformation between the latter and former.[xv] Therefore, the analysis also shows the weak points of the VNSA related to its survival. In general, regardless of their types, every VNSA operates under these basic disciplines.

2. State-Sponsored Terror

State-sponsored terrorism is the government support for violent non-state actors engaged in terrorism.[xvi] Diplomatically, this term is perceived as an unacceptable accusation. So, it results with political disputes and high-tensioned discussions on the definition of terrorism.

IV. Approaches

In the study of international relations there are certain perspectives that perceive each topic and situation on its own unique understanding. In the case of terrorism, most people familiarize the realist approach best suitable for terrorism.[xvii] Although the realist approach on international relations could be described as a security centric approach, this security perspective focuses on relations between states and legitimate international organizations in which terrorist groups and violent non-state actors are not a part of.[xviii] In that regard, two major approaches on terrorism has emerged: statist and cosmopolitan.[xix]

A. Statist Approach

Generally, the statist approach on terrorism is a security oriented perspective that classifies terrorist actions as an act of war.[xx] So it is believed that the most effective strategy to combat the threat is to put pressure, sanctions, and embargo in some cases on states that actively provide support to terrorist organizations. The context also includes political and diplomatic tolerance towards these groups.[xxi]

Unlike the statist approach, cosmopolitan approach recognizes terrorist actions as criminal acts, therefore argues that portrayal as acts of war would lead to counter-productive military response which results with leaving the root causes of terror untouched.[xxii] It is clear that acts of terror violate domestic and international laws, making them criminal acts by nature.[xxiii] The problem is that, acts of terrorism are broader than a criminal act of any kind. It includes many other factors such as politics and engaging in an illegal combat with state forces.

B. Cosmopolitan Approach

Cosmopolitan approach perceives terrorist attacks as criminal acts that requires international attention to provide a multilateral response within the context of international legal system and relevant organization. By addressing the issues of poverty, inequality, and discontent which constitute the root causes, it follows a long-term strategy on countering the threats.[xxiv]

During and after the attacks on Twin Towers, one of the first questions in the minds of public was how to respond to the attacks. The initial response carried out by the Bush administration was to consider them as an Act of War.[xxv] Although the language of war apparent, even for those willing to embrace it conceded that it was a problematic way.[xxvi]

V. Varieties of Counter-Terrorism

A. Coercive Counter-Terrorism

The use of violence solely relies at the discretion of the state, the exercise of hard power. The use of violence by the state are subject to strict limits. These strict national and international principals constitute the legitimacy for the use of force upon the rule of law.[xxvii]

The use of lethal force by the state apparatus, namely the military and police, without legal mandate is to be considered a crime and deemed as violations of national and international laws.[xxviii] When the state combatants perform these acts under the name of counter-terrorism, it is often that they contravene with the rule of law or the laws of war with impunity. That, to an extent, is likely to result with the state forces exercising coercive powers that creates a reign of terror sanctioned by the state in the first place.[xxix]

B. The Criminal Justice Model

This model recognizes the acts of terrorism as a crime.[xxx] When the common types of terrorist actions are evaluated; kidnapping, assassination, the use of ordnance, all lead to injuries and loss of life which themselves are universally recognized as crimes by the respective judiciaries of nations.

Treating acts of terror as an ordinary legal offence instead as a special crime requiring specific procedure has an illegal impact on terrorists.[xxxi] When the actions of terrorists are criminalized by laws, the legal point of view focuses on the criminal nature and this puts a curtain on the political, ideological and motivational aspects of terror.[xxxii]

All these have changed after the attacks of 11 September 2001.[xxxiii] Many sovereign-states have enacted new laws that defined the acts of terror within its own nature after the 9/11 attacks, namely; Canada and the United States in 2001; Australia and Norway in 2002; and Sweden in 2003.[xxxiv] Many of these judicial regulations define ‘motives’ as the central element for the definition of terrorism. These definitions include: committing terrorist actions, committing acts for the purpose of terror, membership in terrorist organizations, and providing material support to fund terror such as financial support, armament and technical expertise support, and recruitment.[xxxv] The creation of speech offences has also increased. United Nations encourages its member states to take measures aimed to prohibit and prevent acts of terrorism by law through the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1624.[xxxvi] Additionally, praising terrorism on speeches is also considered as an offence in several countries such as Turkey, United Kingdom and Spain.[xxxvii]

The criminal justice model relies on a complex chain of bureaucracy with strict rules of governance and institutions in accordance with culture and language. Therefore, the process can be slow and take years in some cases. For that reason some thinkers believe that the model favours the terrorists over victims. As a result, the model has the potential to reach important milestones on the aspects of deterrence, education, and rehabilitation bearing in mind that these are dependent on the ways how the system is being implemented and used, the level of commitment made by the civilians, and most importantly upon the maturity and reliability of the model implemented.[xxxviii]

C. The War Model

The war model, as the name recalls, treats terrorist actions as an Act of War or Insurgency.[xxxix] Wars are usually fought between sovereign states, application of this perception on counterterrorism mechanisms diplomatically implies that the terrorist group being fought against is equivalent of a state. Due to this concern, designating acts of terror as so is more likely to indirectly give terrorist the status of an equal partner in a zero-sum conflict. That is the main reason why many terrorist groups use the word ‘army’ on their names.[xl] Despite the fact that the main apparatus of the war model is the implantation of maximum level of lethal force to outrun the capability of fighting of the enemy, the conduct of war does not occur in a legal context. Because the laws that regulate the wartime functioning of a state specifies how the war should be fought and implies procedures on how to treat non-combatants. The relevant chapter of the 1949 Geneva Conventions on the Status of the Prisoners of War implies that execution and detaining without trial in times of war is legitimate when these actions are aimed to overpower an enemy combatant.[xli] The trade-off is that once a combatant is captured and disarmed, or gives up and abandons the fight, he must be accorded humane treatment, protection, and care.[xlii]

Terrorists, guerrillas, and insurgents do not wear uniforms or insignia identifying them as a combatant of a state that does not exists and the use of stealth brought the adaption of term ‘illegal enemy combatant’ aimed to create an exception to this rule.[xliii] The success on war model tends to be defined as either victory or defeat.[xliv] And a war on terror can only end when the terrorists are completely defeated. But if the conflict is a prolonged one, and it is so in most cases of CT, where the struggle goes on generation by generation, the counter-terrorism efforts must be maintained at all costs as long as a state of war exists. This brings a perception that the public is engaged in a long, never ending war with Islamic terrorism.[xlv] This never-ending vision on the War on Terror has significant impacts on policy implementation.[xlvi]

On a practical basis, this model is considered as a quick, effective and ideal method to the new kinds of emerging threats which are decentralized and ideologically network driven. But they are yet to be contained by traditional military power.[xlvii] For that reason, science and technology became highly important. Examples include; remote sensing, satellite imagery, unmanned aerial vehicles, missile technology and other sophisticated ordnance and munitions, facial recognition and biometrics.[xlviii] The most recent capability achieved by the intelligence agencies to track down terrorists includes ‘the need for birth to death’ tracking and identification along with the methods of protection of critical structure.[xlix] On a worst case scenario of terrorism, the state is facing an atomized, dispersed enemy instead of a simple terrorist group where the individualized ultimate war model is designed to fight this threat by watching, listening, recording, and tracking anyone or anything in the world; striking at will with guided, unmanned combat aerial vehicles; and space-based weaponry.[l] In regards to intelligence, during the first times ever since Barack Obama became the President of United States was to authorize the implementation of a system where the use of drones and targeted assassinations was at the centre of counter-terrorism policies.[li]

The war model carries a high risk of unintended consequences that can escalate violence, undermine the legitimacy of governments that use it, or pull governments along a dangerous path to anti-democratic governance.[lii] But these unfortunate events do not mean that this model is not a useful and valuable method in counter-terrorism on a larger context. In the war theory itself, the use of lethal force can only be justified under certain strict conditions.[liii] It requires a differentiated, well-balanced response declared by a proper authority for a justifiable cause with the aim of outweighing the enemy only, with public support and high probability of success; as a last resort only.[liv]

D. Proactive Counter-Terrorism

The threat of terror has merged internal and external security concerns in a way that resulted with the mandates of domestic law enforcement, intelligence agencies, and customs officials to blend altogether around the issue of tracking the movement of people, materials and financial transactions.[lv] Sophisticated intelligence techniques such as wiretapping, surveillance, eavesdropping and other forms of signals and electronic intelligence (SIGINT/ELINT) have enabled the state to devote more energy and resources to stop acts of terror before happening.[lvi] These developments in the field of intelligence have led to an urgent requirement of a hybrid model of coercive CT, involving elements from the War Model and Criminal Justice Model altogether.[lvii]

Increased focus on the proactive method has important effects on institutions and policies on a wide range of aspects. For the criminal justice it has brought; increase on intelligence-led policy making, increased use of informers, more reliance on preventive detention, and prior arrests of individuals to disrupt plots.[lviii] On the other hand, in the field of intelligence; enlarging surveillance networks on a massive scale, identification of people on a paternal basis, increased use of profiling, increased focus on radicalization and countering radicalization, and tightened track of terrorism financing and fund-raising activities.[lix] In the area of criminal law it has brought more offences, particularly on personal speeches along with criminalizing membership in illegal groups, criminal charges aimed at cutting material supply for fund-raising, training, and recruitment for terrorist groups.[lx] On the military aspects, the use of new technologies has increased drastically by more and more relying on unmanned combat vehicles for surveillance, reconnaissance, and targeted killings; and more political and military intervention in failed and failing sovereign-states to strike facilities and training camps of terrorists. Examples for this are, the French military intervention in Mali and, as a pre-emptive war, US invasion of Iraq back in 2003.[lxi]

Within the spectrum of several political aspects an even further proactive approach requires coordination and integration on different fields: criminal law, policing, intelligence, finance, border control, immigration and refugee policies, military doctrines, diplomacy, development and humanitarian intervention to name a few.[lxii] This brings a requirement for the state to perform cooperation on different areas of jurisdiction where inter-agency cooperation is essential both domestically and internationally.[lxiii]

E. The Intelligence Model

The intelligence apparatus is an extremely critical element for any policymaking efforts in regards to countering terror which is put at the centre in a proactive approach where gathering and using security intelligence (SI/SINT) is essential. In this aspect the use of security intelligence is not limited for obvious purposes but rather directly for intelligence operations.[lxiv] Therefore, the primary goal is not the prosecution of suspects.[lxv] On the contrary, the objective is to gather information on the motives and goals of terrorists. As a result, the specific requirements on information gathering overlaps with judicial investigations.

The proactive method could be described as a double edged sword where it is able to prevent an imminent threat from inflicting damage or destroy a network whereas detaining a wanted terrorist can eliminate opportunities to conduct surveillance and gather more information on unknown terrorist cells.[lxvi]

Recent political developments resulted with the overlapping of national security with social security, prompting surveillance programs on a massive scale and detention without trial which non-citizen permanent residents are also subject to.[lxvii] This is one of the primary reasons on why post-9/11 counter-terrorism policies of intelligence agencies are questioned with the basis of privacy concerns of individual citizens on the use of internet and personal profiling.[lxviii] Two opposing concerns underlie honest efforts to address both security concerns and concerns about democratic acceptability.[lxix]

On one hand, failure to detect an imminent threat may result with even more enlarged surveillance networks as sophisticated as possible. Thereby the state gets stuck between violation of civil liberties and the risk of letting the very people it is violating its rights under risk of getting attacked.[lxx]

On the other hand, targeting of civilians and structures by the terrorists may lead to adaption of strict judicial prohibitions in the name of intelligence gathering. To resolve these concerns, many states formed civilian oversight committees consisting of politicians and enacting legislative mandates that restricts the use of counter-terrorism clauses to specific timeframes which has a risk of negatively affecting intelligence gathering operations.[lxxi]

Relevant state agencies, politicians, private sector, and the media are more likely to attempt to socially direct both of these concerns due to their outcomes of the situation.[lxxii]

F. Persuasive Counter-Terrorism

Figure 4: US Army Psychological Operations Regimental Distinctive Insignia[lxxiii]

In the political and social of life, it is important to understand and encounter the motives and the ideology that drives the terrorists.[lxxiv] These aspects vary on different areas, religion and culture to name a few. Support to terrorism could also be categorized which includes: followers, sympathizers, potential recruits, active and passive supporters, and state sponsors.[lxxv] Like the terrorist groups counter-terrorism bodies are split into different aspects as well which includes several ministries, agencies, allied agencies, private security contractors, and non-state actors within the civil society along with mass media apparatus tasked to respond terrorism on a multi-layered basis.[lxxvi] Therefore, counter-terrorism should encounter with wider audiences.

Terrorism is characteristically communicative, and so is the counter-terrorism efforts.[lxxvii] Psychological warfare (PSYOPS) applications, the use of propaganda, ‘hearts and minds’ campaigns, and policies encouraging terrorists to give up arms through non-violent methods all are means that approaches the issue by putting communications at the centre where every target audience receives a specific message.[lxxviii] Propaganda and discourse are methods that are used by the terrorists too, to blind their followers open new ways of recruitment. From this perspective, counter-terrorism propaganda can also blind citizens and public which is an alternative way of preventing recruiting efforts.[lxxix]

G. Defensive Counter-Terrorism

Certain kinds of terrorist attacks are believed to be imminent by the intelligence agencies so the defensive counter-terrorism method prepares for these attacks by attempting to distract the variables that determine the nature and specifics of the attack.[lxxx] There are two basic ways to execute action, either preventing attacks or mitigating them.[lxxxi] Preventive measures focus on minimalizing the risk of terrorist actions in certain places at certain times. For example, highly increased security sweeps at Times Square on New Year’s Eve. The second approach is to mitigate the impact of the attacks in order to prevent the terrorists to make use of the consequences of their actions, namely for propaganda purposes.[lxxxii]

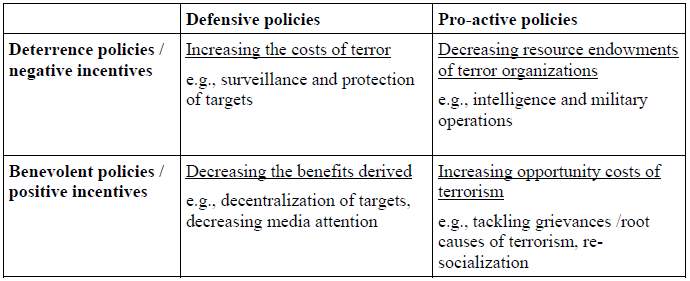

Figure 5: Classification of different types of counter-terror measures[lxxxiii]

H. The Preventive Model

This model priorities on the prevention before the attack. Most of these applications could be witnessed at major ports, terminals, airports. For example, if one has an international flight, he or she has to go through several security sweeps. This perhaps is the most visible and clear example of this model visible at public sphere.

“There are three primary means of prevention:

- Target Hardening

- Critical Infrastructure Protection

- Monitoring and Regulating the flow of people, material, and services”[lxxxiv]

Increasing the level of protection on possible targets aims to make these targets less attractive or more difficult to attack.[lxxxv] This type has conventionally focused on important people (VIPs, bureaucrats and government officials) and high value facilities (Government buildings, military installations) at specific times such as international summits and special anniversaries.[lxxxvi] Making these targets less vulnerable to attacks forces the terrorist groups to innovate and find alternatives, tying up resources and planning. This often leads to target replacement or a shift on softer targets.[lxxxvii] The aim is that, deterring attacks against valuable targets can channel potential terrorists towards less damaging or less costly forms of attack.[lxxxviii]

The second means of prevention is to provide tightened security to structures of critical importance from terrorists.[lxxxix] Although opinions vary on the definition of ‘critical infrastructure’ from a counter-terrorism perspective; energy hubs, industrial centres, and communications facilities are recognized as critical structures.[xc] Potential targets include: hydroelectric and nuclear energy facilities and natural resource refineries, airports, bridges and lately basic water resources.[xci]

When general overview is made, it seems clear that most of the critical structures are under the control of private sector. Therefore, government regulations for these facilities on security matters is limited and weak; it is often that companies object state attempts to increase security levels.[xcii] To conclude, the most important part of securing critical structures is to identify points of intervention where physical, structural and procedural concerns are considered in mind to reduce the likelihood of attacks, and to ensure information exchange across different state agencies and private companies.[xciii]

The third layer of the preventive model focuses on conducting surveillance on the movement of individuals and goods, financial transactions and services with the aim of uncovering plots in the process of being put into actions, with the ultimate goal of preventing them.[xciv] For any member of a terrorist group; basic life stock, shelter, weapons, training, explosive ordnance, safe houses, secure communications, and valid travel documents are vital for survival and achieving the goals of the group[xcv] When there is a scarcity of for getting these material and capabilities, the likelihood of terrorist attacks decreases. In order to cut the reach for those materials to track and identify terrorists, and their plots; increased emphasis is put on border and customs control, immigration and refugee management, observing and regulating the movement of individuals and goods.[xcvi] Special regulations on the financial system is able to cut funding and financing for terrorist groups.

Illegal sale and smuggling of firearms and related material believed to be useful for conducting terror attacks, attempts to bypass sanctions for corporate profit, and evading monitoring programs pose a threat to overall efforts to prevent terror attacks.[xcvii] In order fund their operations, terrorist group take advantage of involving in crime for auxiliary purposes which paves the way for possibility of cooperation between terrorist groups and transnational criminal groups.[xcviii]

I. Long-Term Counter-Terrorism

Long-term CT refers to initiatives that do not promise quick fixes but rather play out on the long term. This also includes efforts to resolve the root causes and structural factors that might have an impact on creating a climate suitable for the glorification of terror. It can often be assumed to be causes, for example, poverty, alienation, discrimination, ideology, are often either facilitating factors, which are usually structural, or triggering factors that are usually ideal in a way that they involve interpretations of an event, situation or a conflict.[xcix] These are the interpretations that are used in the first place in order to recruit and mobile people for causes, prompting the use of violence by terrorists. Radicalisation, mobilisation and recruitment processes are at the central point to understand why ordinary citizens choose to become terrorists and use violence achieve ideological goals with reasons deemed as justifiable according to them.[c]

These are the interpretations that are used in the first place in order to recruit and mobile people for causes, prompting the use of violence by terrorists.[ci] Taking quick actions and using rapid response methods may not lead to clear and remarkable results because of the fact that structural factors change often and they evolve in a slow manner.[cii] This is likely to spark short-term victories into long-term failures and vice-versa. The essential element for effective long-term counter-terrorism strategies is focusing on eliminating back-door-channels of terrorists on a continuous basis, meaning that time after time the state shall always bear in mind that terrorist have several options when following a path and these ways should be targeted too regardless of whether they are adopted or not.[ciii]

J. The Gender Model

A very high majority of terrorists are men are young in age.[civ] Practise of selection on sexes, namely abortion and murder of female children by their parents to their gender have led to a huge gap between the sex ratios of males and females, especially in Asia .[cv] This sociologically meant that many young men in these regions struggle to find a mate, marry, or to raise a family. These seemingly irrelevant but important variables of root causes correspond as a fodder for terrorism recruitment.[cvi]

Studies spectate the existence of a negative correlation between the level of education for women and the number of child she bears.[cvii] As a result, more educated women are more likely to have less children

It is safe to conclude that, more educated women are more likely to have less children. But the education of women on the regions specified above are restricted by cultural norms and in those regions where male-sex is favoured on child making, there is generally a problem of over population and an economy that fails which means less job opportunities that result with more unemployed men.[cviii] Finally, these conclusions lead to the assumption that young, unemployed men are the primary target of audience for terrorist recruiters.

The role of woman in society is traditionally circled around child-raising at the expense of other contributions she may or may not make to her society and economic system, so historically young women are forced into these traditional roles.[cix] Women under the stress of these conditions can be easily convinced to choose the path of terrorists using explosive vests to kill large amounts of people and themselves, suicide bombers namely.[cx] On the contrary, empowering the status and social rights of women could reduce the overall birth-rate, addressing the issues of favouring boys over female children, and resisting the pressure of family and tribal norms is likely to decrease the number of female terrorists being recruited annually.[cxi]

Figure 6: Capt. Anna Crossly of the Royal Army, a Female Engagement Officer, engages with the children and women of the local population in Helmand Province, Afghanistan.[cxii]

VI. Planning, Preparation and Execution

A. C4ISR

C4ISR is basically a military Command & Control definition that stands for Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance.[cxiii] The end of the Cold War has replaced conventional defensive strategies with the uncertainty of failed nation-states, rouge authoritarian regimes, and international terrorist organizations.[cxiv] Combat operations in late twentieth century and early twenty first century were characterized by a dramatic increase in the use of C4ISR systems and network centric warfare concepts as coalition operations in Afghanistan and Iraq has shown how effective these systems can be on the fight against terror.[cxv]

Although the term seems confusing for civilians, the C4ISR involves a vast majority of elements and key applications used in the fight against terror. For example the use of an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle against a terrorist target requires communications, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance.[cxvi] Perhaps a better example would be that of the terrorist groups. The use of social media apparatus such as YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram is known to be Communications element for both terrorists and security forces on a wider spectrum of counter-terrorism.

B. Legality and Human Rights

Legal context of CT varies differently from state to state and in some cases it applies differently depending on the nationality of the detainees or the terrorist militants. But in most cases the common point on the issue is the human rights discussions.

One of the primary difficulties of implementing effective counter-terrorist measures is the decrease of civil liberties and individual privacy that such measures often entail, both for citizens of, and for those detained by states attempting to combat terror.[cxvii] At times, measures designed to tighten security have been seen as abuses of power or even violations of human rights.[cxviii]

While international efforts to combat terrorism have focused on the need to enhance cooperation between states, human rights activists have suggested that more effort needs to be given to the effective inclusion of human rights protection as a crucial element in that cooperation.[cxix] They argue that international human rights obligations do not stop at borders and a failure to respect human rights in one state may undermine its effectiveness in the international effort to cooperate to combat terrorism.[cxx]

C. Status of State Combatants

A legitimate sovereign state fights terrorism with various state institutions and thereby it is expected to push for enhanced cooperation between these bodies. These institutions are divided into three: military, law enforcement, and intelligence.[cxxi] The essential and main organ depends on the threat perception and doctrinal differences in the respective state of relevance.[cxxii] But in most cases it is safe to assume that military is the primary instrument of enforcement for most of the states.[cxxiii]

Military forces have attack helicopters and armed drones at their possession which are the most effective vehicles for any counter-insurgency theatre of operations. The military also provides elite special operations operators who are experts of close quarter combat which is a critical area of expertise at urban areas in case of an attack.[cxxiv] The law enforcement and intelligence organizations provide intelligence to the government not only to prevent the attacks but also to dismantle and control the terrorist groups.[cxxv]

VII. Economics of Terror and Counter-Terrorism

In particular, after the devastating terrorist attacks on New York and Washington on September 11, 2001, the economic analysis of terrorism has gained importance in economic research.[cxxvi] It is fair to conclude that the majority of contributions split into two different areas of focus. Some have focused on the causes of terrorism thereby asking whether terrorism is rooted in poor political and economic conditions whereas the other researchers have focused on the consequences of terrorism.[cxxvii]

Regardless of geopolitical differences and the threat environment, one must realize that any security operation comes with economic implications to the treasury.[cxxviii] The finance of conventional warfare circles around annual defence budgets. However, in the case of terrorism and counter-terrorism this exceeds beyond annual budgets. There are socioeconomic factors as well, in addition to R&D and provincial reconstruction efforts.

A. Economics of Insecurity: Causes and Effects

An economic analysis of terrorism always implies that terrorists are rational actors who are influenced in their decisions to commit acts of terror by a certain set of determinants impacting on their cost-benefit matrices based on the causes of terror.[cxxix] When it comes to identification of the causes, it has shown that there is no ‘one size fits all’ result.[cxxx]

B. Economic Effects of Anti-Terrorism Policy

Direct economic impacts of terrorism refer to the effects arising from the immediate aftermath of a terrorist event.[cxxxi] Estimating these impacts require accounting for the physical destruction of buildings, infrastructure, and losses of human life or capabilities via injuries, but also for the economic impacts resulting from actions to mitigate damages.[cxxxii] Furthermore, in an interdependent economic system, terrorist strikes causes the disruption of economic activities which may feed through, even to economic entities which have not been direct targets of the attack.[cxxxiii]

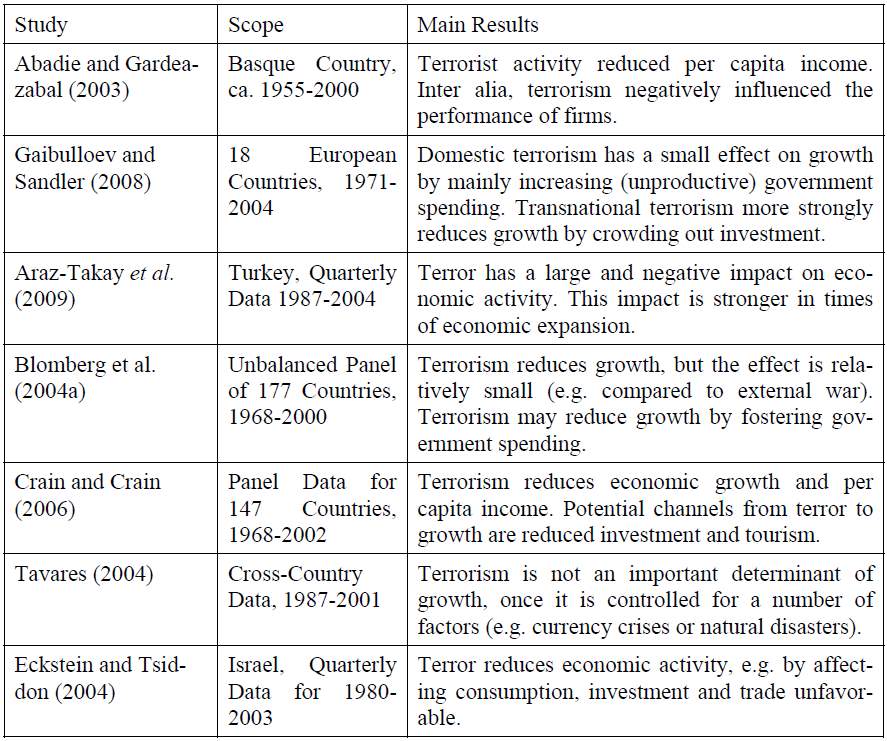

In a state of terror requires strict policies to combat it. In most of the times the domestic economy gets affected by these events which are called Growth Effects of Terrorism.[cxxxiv] To have a better understanding, some empirical research studies are given below.

Figure 7: Some Empirical Evidence on the Growth Effects of Terrorism[cxxxv]

VIII. Major Doctrinal Examples and Tactics

A. Hearts & Minds

Hearts and Minds is a concept that was used by the US military in Vietnam War where to resolve the conflict, one side seeks to prevail not by the use of superior force but by making emotional and intellectual appeals to sway away supporters of the other side. This concept basically aims to focus on public affairs and psychological warfare applications on the battlefield.

Figure 8: A US Army UH-60 Blackhawk helicopter drops propaganda leaflets on a village in Afghanistan[cxxxvi]

B. Foreign Internal Defence

Foreign Internal Defence (FID) is the participation by civilian and military agencies of a government in any of the action programs taken by another government or other designated organization, to free and protect its society from subversion, lawlessness, insurgency, terrorism, and other threats to their security.[cxxxvii]

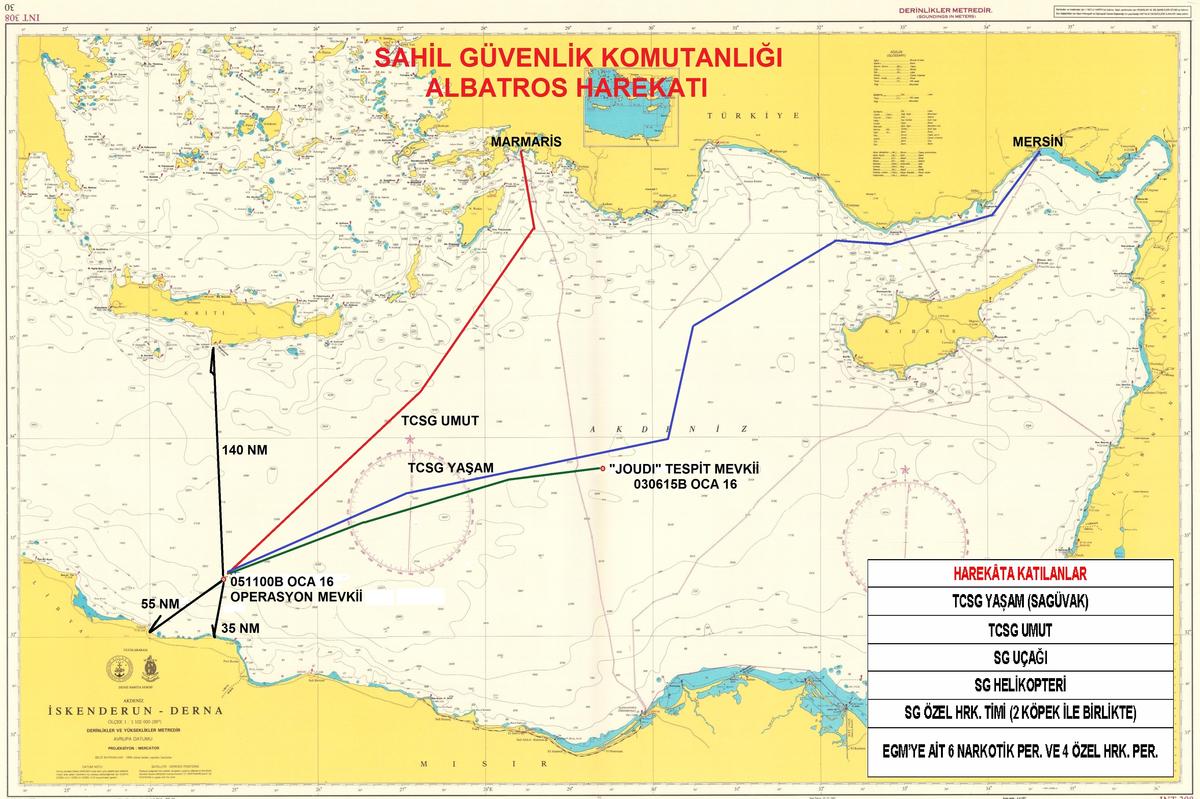

Although the definition seems a bit complex, FID is basically conducting combat operations outside the sovereign soils of a nation in the name of eliminating threats to its domestic security.[cxxxviii] For example, the establishment of several outposts and forward operating bases by the Turkish Land Forces in Northern Iraq and Syria are actions of foreign internal defence.[cxxxix] A second example would be Operation Albatross where very large amounts of illegal drugs that were believed to be material to fund acts of terrorism in Turkey were seized by a joint operation between the Turkish Coast Guard and the Turkish National Police off the coast of Libya.[cxl]

Figure 9: Geographical illustration of Operation Albatross on a map.[cxli]

C. Guerrilla Warfare

Guerrilla warfare is the type of warfare that is fought by irregulars in fast-moving, small-scale actions against military and police forces, and in occasion, against rival insurgent forces, either independently or in conjunction with a larger political-military strategy.[cxlii] This type of warfare has assumed a universal character under the banner of religious fundamentalism. The most prominent practitioner of this type is al-Qaeda along with TTP of Pakistan and PKK in Turkey.

D. Unconventional Warfare

Unconventional warfare differs profoundly from warfare in which regular armies are openly engaged in combat.[cxliii] The objective of such conventional combat is to win control of a state by defeating the military forces of a state. In contrast, the strategy of unconventional forces must be to win control of the state by first winning control of civilian population, militarily inferior guerrilla forces can have no hope of success.[cxliv]

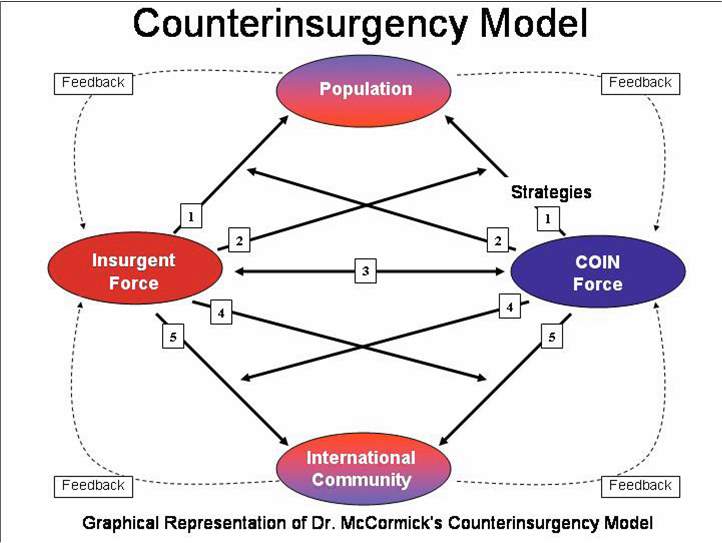

E. Magic Diamond Model

A variety of models for understanding insurgency and planning counterinsurgency response have been developed. One model that has become respected both in academic and military context is the ‘Magic Diamond’ model developed by Gordon McCormick of the RAND Corporation.[cxlv]

This model develops a symmetrical view of the required actions for both the Insurgent and COIN forces to achieve success.[cxlvi] In this way the counterinsurgency model can demonstrate how both the insurgent and COIN forces succeed or fail. The strategies of this model and principle apply to both forces, therefore the degree the forces follow the model should have a direct correlation to the success or failure of either the Insurgent or COIN force.[cxlvii]

Figure 10: Illustration of the Magic Diamond Model[cxlviii]

F. Vehicle Ramming and Lone Wolfs

With the increase of violence on the efforts to defeat the Islamic State, the conflict spilled over across Europe by terrorists targeting the civilian populations at major cities. Due to increase surveillance on personal transportation and the regulations on material suitable for the use of terrorist attacks, the terrorists adopted a new strategy to evade these efforts.[cxlix] Lone Wolf tactic is to prepare, plan, and execute an attack by one individual alone to bypass government efforts to track down terrorist networks.[cl] In most cases these attackers carry small fire arms and improvised explosive devices.[cli] The other trend is the use of large, transportation trucks and to drive them over civilian populations, particularly on crowded, touristic areas.

G. Hybrid Warfare

The Hybrid Warfare is a military strategy that blends conventional warfare, irregular warfare, and cyber warfare.[clii] By combining kinetic operations with subversive efforts, the aggressor intends to avoid attribution or retribution.[cliii]

IX. Conclusion

The use of violence for political motives is not something new for the daily lives of mankind. There will always be war against an opponent. In some cases it is a nation state but today it is non-violent state actors. War is a country of will, if one is not willing to give up everything, the war is already lost. On the spectrum of counterterrorism, it is highly important that governments and military forces adopt to changing environments fast and agile. History has shown that the use of force is as much as relevant as looking into root causes of terrorism; in simplest terms, it is also the ability of the state to prevent the individual to take up arms against his own country or any other state that is the target of systematic hatred. Terrorists win by getting one victory only which they will feed with propaganda and human resources whereas the state can lose its entire chain of efforts by not being able to prevent that one single act of terror which can change the opinions of many citizens.

XI. Bibliography

[i] Understandingwar.org. (n.d.). The Islamic State: A Counter-Strategy for a Counter-State. [online] Available at: http://www.understandingwar.org/report/islamic-state-counter-strategy-counter-state [Accessed 6 November 2017]

[ii] Dtic.mil. (2014). United States Joint Counter-Terrorism Doctrine JP 3-26. [online] http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp3_26.pdf [Accessed 21 Oct. 17]

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Usacac.army.mil. (2006). United States Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual FM 3-24/MCWP 3-33.5. [online] http://usacac.army.mil/cac2/Repository/Materials/COIN-FM3-24.pdf [Accessed 22 Oct. 17]

[viii] Dni.gov. (2007). National Intelligence Council, Non-state Actors: Impact on International Relations and Implications for the United States. [online] https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/nonstate_actors_2007.pdf [Accessed 22 Oct. 17]

[ix] Claws.in. (2013). Violent Non-State Actors: Contours, Challenges, and Consequences. [online] http://www.claws.in/images/journals_doc/2140418965_RajeevChaudhry.pdf [Accessed 22 Oct. 17]

[x] Seymour, G. (1975). Harry’s Game. New York: Random House, pp. (n.d.).

[xi] Au.af.mil. (2004). United States Air Force Academy IITA: Modelling Violent Non-State Actors: A Summary of Concepts and Methods. [online] http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/usafa/modeling_vnsa.pdf [Accessed 22 Oct. 17]

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Maogoto, J. N. (2005). Battling Terrorism: Legal Perspectives on the Use of Force and the War on Terror. Asgate. pp. 59.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Shimko, K. L. (2014). International Relations: Perspectives, Controversies and Readings. 5th Ed. Boston: Cengage Learning. pp. 296.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] Crelinsten, R. (2014). Perspectives on Counterterrorism: From Stovepipes to a Comprehensive Approach. Perspectives on Terrorism (8)1. Leiden University Terrorism Research Initiative

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] Ibid.

[xxxi] Ibid

[xxxii] Ibid.

[xxxiii] Huffingtonpost.com. (n.d.). U.S. Strategy after 9/11: Ruminations on a Lost Decade. [online] Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/nathan-gonzalez/us-strategy-after-911-rum_b_961215.html

[xxxiv] Fco.gov.uk. (2005). UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, ‘Counter-Terrorism Legislation and Practice: A Survey of Selected Countries’. [online] http://www.fco.gov.uk/en/newsroom/latest-news/?view=PressR&id=4186457 [Accessed 23 Oct. 17]

[xxxv] Ibid.

[xxxvi] Un.org. (2005). United Nations Security Council Resolution 1624. [online] http://www.un.org/Docs/journal/asp/ws.asp?m=S/RES/1624(2005) [Accessed 23 Oct. 17]

[xxxvii] State.gov. (2016). US Department of State: Country Reports on Terrorism, Europe. [online] Available at: https://www.state.gov/j/ct/rls/crt/2016/272231.htm [Accessed 6 November 2017]

[xxxviii] Ibid.

[xxxix] Ibid.

[xl] Ibid.

[xli] Un.org. (1949). Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. [online] http://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/atrocity-crimes/Doc.32_GC-III-EN.pdf [Accessed 23 Oct. 17]

[xlii] Rona, G. (2005). Interesting Times for International Humanitarian Law: Challenges from the ‘War on Terror’, Terrorism and Political Violence 17. (n.d.). pp. 164.

[xliii] Ibid.

[xliv] Angstrom, J. (2007). Understanding Victory and Defeat in Contemporary War. London: Routledge.

[xlv] Podhoretz, N. (2007). World War IV: The Long Struggle against Islamofascism. New York: Doubleday.

[xlvi] Ibid.

[xlvii] Ibid.

[xlviii] Ibid.

[xlix] Query.nytimes.com. (2007). The New York Times: The Big Thought Is Missing in National Security. [online] http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=950DE3DA1731F932A35754C0A9619C8B63 [Accessed 23 Oct. 17]

[l] Ibid.

[li] Aslam, M. W. (2011). Critical Studies on Terrorism: Evaluation of American drone strikes in Pakistan. Vol 4. pp. 313-329.

[lii] Parker, T. (2007). ‘Fighting an Antaean Enemy: How Democratic States Unintentionally Sustain the Terrorist Movements They Oppose’ Terrorism and Political Violence. Vol 19. pp. 179.

[liii] Elshtain, J. B. (2003). Just War against Terror: The Burden of American Power in a Violent World. New York: Basic Books.

[liv] Ibid.

[lv] Ibid.

[lvi] Ibid.

[lvii] Ibid.

[lviii] Ibid.

[lix] Schmid, A. P. (2013). Radicalization, De-Radicalization, Counter-Radicalization: A Conceptual Discussion and Literature Review. ICCT Research Paper, International Centre for Counter-Terrorism. The Hague.

[lx] Ibid.

[lxi] Ibid.

[lxii] Ibid.

[lxiii] Ibid.

[lxiv] Ibid.

[lxv] Ibid.

[lxvi] Ibid.

[lxvii] Ibid.

[lxviii] Ibid.

[lxix] Ibid.

[lxx] Ibid.

[lxxi] Ibid.

[lxxii] Ibid.

[lxxiii] Psywarrior.com. (n.d.). Crest. [online] Available at: http://www.psywarrior.com/crest.gif [Accessed 9 November 2017]

[lxxiv] Ibid.

[lxxv] Ibid.

[lxxvi] Ibid.

[lxxvii] Crelinsten, R. (1987). Terrorism as Political Communication: the Relationship between the Controller and the Controlled. Washington DC: Centre on Global Counter-Terrorism Cooperation.

[lxxviii] Ibid.

[lxxix] Ibid.

[lxxx] Ibid.

[lxxxi] Ibid.

[lxxxii] Ibid.

[lxxxiii] Ibid.

[lxxxiv] Ibid.

[lxxxv] Ibid.

[lxxxvi] Ibid.

[lxxxvii] Ibid.

[lxxxviii] Ibid.

[lxxxix] Ibid.

[xc] Ibid.

[xci] Newsecuirtybeat.org. (2014). Water and the Rise of Insurgencies in the ‘Arc of Instability’. [online] https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2017/04/water-rise-insurgencies-arc-instability/ [Accessed 29 Oct. 17]

[xcii] Ibid.

[xciii] Ibid.

[xciv] Ibid.

[xcv] State.gov. (2009). US Department of State ‘the Global War on Terrorism: The First 100 Days’. [online] https://2001-2009.state.gov/s/ct/rls/wh/6947.htm [Accessed 29 Oct. 17]

[xcvi] Ibid.

[xcvii] Ibid.

[xcviii] Berdal, M. (2002). Transnational Organized Crime and International Security: A New Topology. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

[xcix] Bjorgo, T. (2005). Root Causes of Terrorism: Myths, Reality and Ways Forward. London: Routledge.

[c] Forest, J. J. F. (2006). The Making of a Terrorist: Recruitment, Training, and Root Causes. Vol III. Westport: Praeger Security International.

[ci] Ibid.

[cii] Ibid.

[ciii] Ibid.

[civ] Ibid.

[cv] Ibid.

[cvi] Ibid.

[cvii] Beegle, K. (1996). The Impact of Women’s Schooling on Fertility and Contraceptive Use: A Study of Fourteen Sub-Saharan African Countries. World Bank Economics Review. pp. 85-122.

[cviii] Ibid.

[cix] Ibid.

[cx] Ibid.

[cxi] Ibid.

[cxii] British Legion.org.uk. Anna – a female soldier in Afghanistan. [online] Available at: http://www.britishlegion.org.uk/community/stories/general/anna-a-female-soldier-in-afghanistan/ [Accessed 30 Oct. 17]

[cxiii] MAJ Dacus, A. P. (2006). Impact of C4ISR/Digitalization and Joint Force ability to conduct the Global War on Terror. United States Army Command and General Staff College, School of Advanced Military Studies. Kansas: US Army

[cxiv] Ibid.

[cxv] Ibid.

[cxvi] Ibid.

[cxvii] Dorsey, J. (2015). Accountability and Transparency in the United States Counter-Terrorism Strategy. International Centre for Counter-Terrorism. [online] Available at: https://icct.nl/publication/accountability-and-transparency-in-the-united-states-counter-terrorism-strategy/ [Accessed 30 Oct. 17]

[cxviii] Canaan, L. (2016). Fighting Terrorism without Violating Human Rights. Huffington Post. [online] Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/lydia-canaan/fighting-terrorism-withou_b_9513034.html [Accessed 30 Oct. 17]

[cxix] Ibid.

[cxx] Hrw.org. (2004). Human Rights and Counter-Terrorism: Briefing to the 60th Session of the UN Commission on Human Rights. [online] https://www.hrw.org/legacy/english/docs/2004/01/29/global7127.htm [Accessed 30 Oct. 17]

[cxxi] Ibid.

[cxxii] Ibid.

[cxxiii] Ibid.

[cxxiv] Ibid.

[cxxv] Ibid.

[cxxvi] Schneider et al. (2009). The Economics of Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism: A Survey. Berlin: ‘DIW Berlin: European Security Economics’. pp. 6

[cxxvii] Ibid.

[cxxviii] Ibid.

[cxxix] Ibid.

[cxxx] Ibid.

[cxxxi] Ibid.

[cxxxii] Ibid.

[cxxxiii] Ibid.

[cxxxiv] Ibid.

[cxxxv] Ibid.

[cxxxvi] Leaflet Drop in Afghanistan. (2016). Mateusz Kaim Blog, Ex-Polish Army. [online] Available at: http://mateuszkaim.pl/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/leaflet-drop-afghanistan.jpg [Accessed 30 Oct. 17]

[cxxxvii] Dtic.mil. US Department of Defense, Defense Technical Information Centre: Foreign Internal Defense, JP3-22. [online] Available at: http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp3_22.pdf [Accessed 30 Oct. 17]

[cxxxviii] Ibid.

[cxxxix] Ibid.

[cxl] Wikipedia.org. (2016). Operation Albatros. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Albatros [Accessed 30 Oct. 17]

[cxli] Turkishnavy.net. (2016). Turkish Coast Guard Intercepts Cargo Ship with Drugs on Board. [online] Available at: https://turkishnavy.net/2016/01/07/turkish-coast-guard-intercepts-cargo-ship-with-drugs-on-board/ [Accessed 30 Oct. 17]

[cxlii] Britannica.com. (n.d.). Guerrilla Warfare. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/guerrilla-warfare [Accessed 30 Oct. 17]

[cxliii] Ibid.

[cxliv] Foreignaffaris.com. (1962). Unconventional Warfare. [online] Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/asia/1962-01-01/unconventional-warfare [Accessed 30 Oct. 17]

[cxlv] McCormick, G. (1987). The Shining Path and Peruvian Terrorism. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation.

[cxlvi] Ibid.

[cxlvii] Ibid.

[cxlviii] Ibid.

[cxlix] Ibid.

[cl] Ibid.

[cli] Ibid.

[clii] Ibid.

[cliii] Nextgov.com. (2010). Defense Lacks Doctrine to Guide It through Cyberwarfare. [online] Available at: http://www.nextgov.com/nextgov/ng_20100913_7634.php?oref=topnews [Accessed 30 Oct. 17]

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Terrorism"

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: