Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) During the UN Peacekeeping Operations

Info: 45725 words (183 pages) Dissertation

Published: 11th Dec 2019

THE WOMEN PROTECTION UNDER THE INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW: A STUDY FOCUSED ON THE SEXUAL EXPLOITATION AND ABUSE (SEA) DURING THE UN PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS

A CASE STUDY OF SEXUAL EXPLOITATION AND ABUSE (SEA) IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC)

ABSTRACT

THE WOMEN PROTECTION UNDER THE INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW: A STUDY FOCUSED ON THE SEXUAL EXPLOITATION AND ABUSE (SEA) DURING THE UN PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS

From the past period until the 21st century, the new international issues and challenges have been increased noticeably. As occurring during the interwar era, wars between states have been considered as a significant issue. After the establishment of the United Nations and the International Law, wars between have rarely occurred. However, the new International issues and challenges have been emerging through times. At the same time, with the presence of the development of the International Law, it also reflects the new International issues and challenges. Since then the armed-conflict has been considered as one of the issues, but the United Nations responses to the issue by establishing the Peacekeeping Operations under the Chapter VII of UN Charter. With the Peacekeeping Operations, it does not guarantee the success of its response. One of the challenges, which this dissertation will focus on that originates from the Peacekeeping operations itself is the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA). From the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA), Women who are considered as in a vulnerable group suffer greatly from it. To analyze and study on the women protection from the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA), this dissertation will examine and analyze over the related International law, especially under the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and International Human Rights Law (IHRL). Therefore, this paper will put forward into five important chapters. To begin with, the Chapter one just starts with the brief introductory background of SEA, scope and limitation of this study, and research methodology. Importantly, chapter two opens with the definition of the “Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA), examine and analyze the International legal frameworks which granted protection for women from such violation and abuse, especially the special protection of women. Moving further to the Chapter three of this dissertation, an in-depth analysis of the applicability of the IHL, and obligations of the UN peacekeepers to bring the perpetrator to justice. Chapter four of this dissertation will have a deep analysis in the case of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). From this chapter, I have found that not the Intervention Brigade is considered as a party of the armed-conflict, but the MONUSCO as a whole is considered as a party of the armed-conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which would place the mission as a whole under the application of the IHL. To finalize this dissertation with the chapter five, I have come up with such potential approach and proposal for the future protection of women from the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) committed by the UN personnel. The Conclusion of this dissertation is drawn in Chapter Six. It summarizes all the discussion and analysis of this dissertation and shows the keystones in the development of rules protection women.

CONTENTS

1-4. Scope and Limitation of the Study

CHAPTER TWO: THE PROTECTION OF THE WOMEN UNDER THE INTERNATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK

2-1. The Introduction to International Humanitarian Law

2-1.1 Legal Source of International Humanitarian Law

2-1.1.1. International Conventions or Treaties

2-1.1.2. Customary International Law (CIL)

2-1.1.3. General Principles of Law and the Judicial Decision

2-2. The Peacekeeping Operations

2-2.1. The Historical Development of Peacekeeping Operations

2-2.1.1. The Traditional Peacekeeping Operations

2-2.1.2. The Peacekeeping Operations with civilian tasks

2-2.1.3. The Peacekeeping Operations: Peace Enforcement

2-2.1.4. The Peacekeeping Operations: Peace-building

2-2.1.5. The Peacekeeping Operations: as a hybrid mission

2-2.2. Organizational Structure of Peacekeeping Operations

2-3. The General Introduction to the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

2-3.1. The Development of the Prohibition of the SEA

2-3.2. Definition of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

2-3.3. The Scope of Application and Standards on the SEA

2-4. The General Protection under International law

2-4.1. The Women Protection under the International Humanitarian Law

2-4.1.1. The 1949 Geneva Conventions

2-4.2. The Women Protection Under the IHRL

2-4.2.1. The Convention on the Rights of Child (CRC)

3-1. Applicability of the IHL to the UN Peacekeeping Operations

3-1.1. Status of Force Agreements (SOFA)

3-1.2. The Convention on the Safety of United Nations and Associated Personnel

3-1.3. The Bulletin on the Observance by United Nations Forces of International Humanitarian Law

3-1.3.1. The problem of the Bulletin’s Nature

3-2. The Status of the UN Peacekeepers

3-2.1. Peacekeepers under the International Humanitarian Law

3-2.2. Peacekeepers under the U.N Documents

3-2.3. The Status Of UN peacekeepers under Customary Law

3-3. UN Peacekeepers’ Obligations

3-3.1. The General Principle of UN peacekeeping operations

3-3.2. The Blue Helmet’s Code of Conduct

3-4. The obligations of the Troop Contributing Countries

3-3.1. Assuring the accountability of the committed crimes or offences

4-1. The UN Peacekeeping Operations in the DRC

4-1.1. The Establishment of MONUSCO

4-1.1.1. Background Crisis of DRC

C. The March 23 Movement (M23)

4-1.2. The notion of Intervention

4-1.2.1. The Military Intervention

4-1.2.2. The Humanitarian Intervention

4-1.2.3. The Intervention Brigade

4-2. The Applicability of IHL to the MONUSCO and Intervention Brigade

4-2.1. Determining the Armed-Conflict in the DRC

4-2.1.1. Active Armed Groups in the DRC

A. The Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda

C. The Allied Democratic Force

D. The National Congress for the Defense of the People

4-2.2. The MONUSCO as a party to the Armed-Conflict

4-2.2.1. Relevance to the Intervention Brigade

4-2.3. Legal Status of Peacekeepers under MONUSCO and Intervention Brigade

4-3. The Challenges to the Women Protection in the Congo

4-3.1. Allegation of the SEA by UN Personnel

4-3.1.4. The impacts on the Victims of the SEA

B. The Psychological or Mental impact

4-3.4. Lack of evidence and insufficient investigation

4-4. International response to the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

4-4.1. United Nations’ Response to the SEA

5-1. The National efforts over the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

5-1.1. A vetting mechanism on the Security Forces

5-1.1.1. The Increasing role of the Female UN personnel

5-1.2. The Amendment on Paragraph 47 of the Model UN Status of Force Agreement

5-2. The Problem Solving at the International Level

5-2.1. The feasibility of the Special Permanent Court

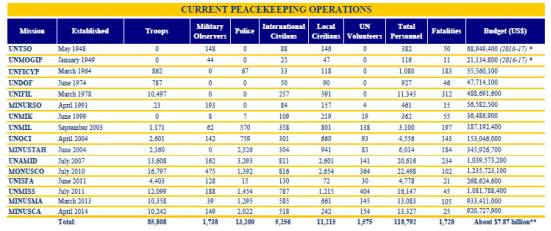

Table 1: The Current Peacekeeping Operations

Table 2: The Allegation, Investigation and Actions from 2016 to 2017

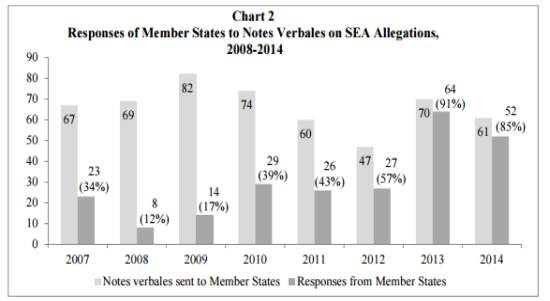

Table 3: The Response of Member States on the SEA Allegations

Table 4: The Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) from 2010 to 2017

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ADF Allied Democratic Force

API Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949

APII Additional Protocol II to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949

ASEAN Association of Southeast Asia Nations

AU African Union

CAH Crime against Humanity

CIL Customary International Law

CNDP National Congress for the Defense of the People

CRC Convention on the Rights of the Child

DPKO Department of the Peacekeeping Operations

DRC Democratic Republic of the Congo

EU European Union

FARDC Forces Armees de la Republique Democratique du Congo

FDLR Democratic Forces of the Liberation of Rwanda

FIB Force Intervention Brigade

GCI The First Geneva Convention

GCII The Second Geneva Convention

GCIII The Third Geneva Convention

GCs The Geneva Conventions

GCVI The Fourth Geneva Convention

IAC International Armed-Conflict

ICC International Criminal Court

ICJ International Court of Justice

ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross

ICSS International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty

IHL International Humanitarian Law

IHRL International Human Rights Law

IOs Intergovernmental Organizations

LRA Lord’s Resistance Army

M23 The March 23 Movement

MONUC United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

MONUSCO United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NGOs Non-Governmental Organizations

NIAC Non-International Armed Conflict

OCHR Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

OIOS United Nations Office of Oversight Service

ONUSAL United Nations Observer Group in El Salvador

OSCE Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe

PIL Public International Law

R2P Responsibility to Protect

RCD Rassemblement Congolais pour la Democratie

SEA Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

SOFAs Status of Forces Agreements

SRSG Special Representative of the Secretary-General

TCCs Troop Contributing Countries

UN United Nations

UNAMIR United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda

UNGA United Nations General Assembly

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

UNMID United Nations-African Union Mission in Darfur

UNSC United Nations Security Council

UNSG United Nations Secretary General

UNTAC United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia

UNTAG United Nations Transition Assistance Group

UNTSO United Nations Truce Supervision Organization

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

With the evolution of the International Law, it has been divided into two aspects known as the Public International Law and Private International Law. Regarding the Public International Law (PIL), it governs and helps to maintain the International Peace and Security. Children and Women, who have always been considered as in the vulnerable groups, have been violated and abused with their rights, especially in certain developing countries suffering from the civil wars and conflicts. This has not been viewed as a new issue for the Public International Law (PIL), but as a new challenge contributing the greatest threat to the International Peace and Security.

If we take a look at the International Legal system concerning the protection of individual rights, we definitely can find that the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) has always been there to serve and develop in response to the globalization[1]and the violation of individual rights, especially to the child’s and women’s rights. In the field of the International Humanitarian matters, it should be viewed as the International Common problems rather than being viewed as an isolated one[2] since the International Humanitarian problems are all interconnected in concerns of the International Security. The world, from time to time, is continuously undergoing rapid changes in relevance to the International Humanitarian matter which deems in need of cooperation from State and Non-State Actors. The International Humanitarian actions are conducted and cooperated by states, Intergovernmental Organization, and non-governmental organization are as means to help and protect individual and groups of people against the threat or the violation of their rights. Working out a code of cooperation on the Humanitarian issues and proceeding from the general principles, it should be starting from the regional or international cooperation to make use of the Intergovernmental Organization or Regional Organizations, particularly in the field of the International Humanitarian actions. The International Cooperation on the International Humanitarian issues should be based upon the general principles[3] as being mentioned below:

- Given more respect to the right of self-determination of each nation. For instance, states receive their rights to decide its own future without any interference from the outside,

- The collective cooperation among states in spreading out the peace’s notion, disarmament, and protect and promote the human rights and freedoms,

- The cooperation between all states on the dissemination of objective information[4], and enhancing the quality of such information about each nation’s issues so that international confidence, understanding, and awareness can be promoted,

- The Exclusion or prohibition of any kind of discrimination and exploitation or abuse against individuals’ rights, especially the protection of the vulnerable groups,

- The collection response from all states in abolishing genocide and apartheid, and prohibiting the existence of the notion of fascism which possibly leads to the human rights violations.

After the end of the World War II (WWII), it could be considered as the Modern International Law, with the existence of the Intergovernmental Organization which is the so-called “United Nations (UN).” Based on the establishment and its existence, the United Nations has played an important role in maintaining the International Peace and Security. As based on what mentioned above, the Intergovernmental Organization known as the United Nations (UN) has carried a remarkable role in the International Humanitarian matters, especially to carry out the International Humanitarian Actions. Due to the fact that the United Nations (UN) has no its own standing troop or police force,[5] the question then arises, “How can the United Nations carry out its significant role in maintaining the International Peace and Security, especially to carry out the International Humanitarian Actions.? To illustrate the mentioned question, the United Nations has been considered as the one of the Intergovernmental Organization (IOs) that has been joined by many countries around the globe. The purpose of the United Nations is carried out by the member states as by the UN Charter.[6] However, the member states, in a condition of respecting state sovereignty, are not allowed to carry out the act directly. Member states normally contribute their troop to the United Nations so that the organization can carry out the actions.[7] The troop, polices or armies that are sent to the United Nations are called the peacekeepers. The countries, which the United Nations send the peacekeepers to, are mostly suffering from the humanitarian crisis, and are in need of the humanitarian assistance. In the humanitarian crisis, the exploitation and violation mostly on the civilian’s rights, especially on the women and child who are in the vulnerable group. The Violation of women’s rights could also be considered as the violation of the dignity, safety, and Human Rights. Surprisingly, such violations are also involved by the UN peacekeepers whose mission is supposed to maintain the peace and security and to protect the civilian. In this sense, the impunity among the peacekeepers becomes the problem of implementation of the International Law, which the UN peacekeepers are committing crimes during the peacekeeping mission could mostly get away from the criminal prosecution for their actions due to the fact that the immunity is granted to UN peacekeepers.[8] Due to the mentioned problem, it brings and remains injustices to the victims of the crime committed by the UN peacekeepers, and extremely ruins the reputation and image of the United Nations.[9]

As mentioned above about the problem, it could be seen that this study is considered to be very significant because the problem is not only about the International peace and security. However, it has also been involved in the women protection who are in the vulnerable group, and the reputation and image of the United Nations which could lead the loss of trust from the countries around the world. To mention and study the problem, this paper will show how the International law, especially the IHL as well as the IHRL can be used as the International Legal Instrument in protecting and promoting the women’s rights. As to have an in-depth study, this paper will take and be focused on the case study of the Democratic Republic of Congo since this country has suffered and remains from such phenomenon of peacekeeping personnel involving in the sexual exploitation of women and girls in 2004 during the UN Peace Support Operations causing a serious public outcry.

Based on such a problem, the women, who are in the vulnerable group, has still been suffering from the exploitation and abuse. Surprisingly, the problem remains unsolved, and the victims are also living in the shadows. In this sense, it is an important point for the international community to pay more attention to the women protection and justice of the victims, especially the case of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) which has been alleged of the exploitation and abuses the most among countries in Africa Continent. As a result, this dissertation will be focused and studied by answering the following legal issues:

- What constitutes Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA)? Who can be considered as the perpetrator of the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse?

- What are the regional or International legal frameworks in the purpose of protecting Women’s right?

- What are the obligations and responsibilities of the United Nations to the issue of SEA? And to what extent will the United Nations bound by the International Humanitarian Law?

- Is there any illegitimated act or cases of the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) committed by the UN peacekeepers? What are the responsibilities or accountabilities of the peacekeepers in violation of the sexual exploitation and Abuse?

- What are the potential approaches and proposals to the future protection of women during the UN Peacekeeping Operations?

Acknowledging the important that Women’s rights should be protected from all violations, especially in the case of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse, and the necessary of the legal analysis of the International Legal Frameworks concerning the Women’s rights so that the available approach and proposal could be brought up to order to bring justice to the victims. As a result, this paper will focus on the following important point which is organized as below:

Chapter One: The initial part of the paper is the Introduction which will focus on: The rationales detailing the motions why the topic is chosen, the Legal Issues which are going to be dealt with, the Study objective of this dissertation will be presented in that section, the scope and limitation of study, last but definitely not lease the paper will also focus on the research methodology.

Chapter Two: Answering the legal issue, this section will firstly provide the general introduction to the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) by defining the term “Sexual Exploitation and Abuse”, and studying about the relation between the International Humanitarian Law as one of the International Law and the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA).examine and analyze the International legal frameworks which granted protection for women from such violation and abuse, especially the special protection of women.

Chapter Three: This section will provide the updated review of the current status of UN peacekeepers within the legal and regulatory framework for their conduct, and examine the obligation of UN peacekeepers, Troop Contributing Countries (TCCs), and host state. Importantly, this section will also examine and analyze the International Legal Frameworks concerning on the applicability of the IHL, and obligations of the UN peacekeepers in order to bring the perpetrator to justice.

Chapter Four: This section will be studied on the problem of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse toward the women as victims by the UN peacekeepers and in hopes of contributing to raise awareness of the case. Lastly, the UN’s response to the women protection will also be presented.

Chapter Five: Resembling the conclusion of this dissertation, the last section of this paper will search and look up for the future possible solution and proposal on the improvement of the women protection during the UN peacekeeping operations.

Chapter Six: Last but definitely not least, this chapter will wrap up and provide a summary of this dissertation, with the potential solution and proposal which have been mentioned in Chapter five.

Owing to the nature of the topic, there has been many crimes committed during the United Nations Peacekeeping Operations, but this paper will only focus on the Women Protection from the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse which leads to the accusation of the UN peacekeepers as perpetrators. Within the African Continent, there are some cases of the UN Peacekeeping Missions which leads to the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse. However, this scope of this dissertation will mainly focus on the case of the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Besides, this research has encountered several limitations when this paper is being written. The problem of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) happens to several countries in the African Continent. However, due to the constraint, this dissertation faces another limitation that it will only focus on the women protection from the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) during the UN Peacekeeping Operation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

With the nature of the topic, this study will employ descriptive study in order to collect information about background of key actors, international norms, rules and laws, case reports, and case study regarding the topic. With the collected information from the descriptive study, the analytical study will also be employed to analyze the international norms, rules, and laws which will be used in Chapter 3, 4 and 5 of this dissertation. The framework of this study is based on the content analysis on the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) during the UN Peacekeeping Operation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

For the data collection, this paper will utilize both the primary sources and secondary sources in order to fill in the analysis and justify the finding of this paper. In order to collect the primary sources, International Conventions or Agreements will be employed as references to analyze the facts and cases. The International Convention or agreements includes the Charter of United Nations, the Four Geneva Convention in 1949, and other related International Laws concerning the Women Protection. Besides, secondary data will be obtained from online articles, journals, previous related researches, case reports, case studies, and International Organizations’ Publications.

CHAPTER TWO: THE PROTECTION OF THE WOMEN UNDER THE INTERNATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The International Humanitarian Law which is known as IHL is a collective rule of the International conventions or agreements seeking for humanitarian reasons to solve societal issues and effect of the armed-conflict.[10] Since the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) is also one part of the International Law, it helps to govern the relations between States and International Organization, and other subjects of the International Law. The International Humanitarian Law applies to all of the situations of the armed-conflict, which aim to protect the civilian and regulate over the method of warfare.[11]

As mentioned above that the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) is also one part of the International Law, the source of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) could also be considered as the same as the source of the International Law[12] as well, which include International Treaties or conventions, Customary International Law, General Principle of Law, and judicial decision and teaching of the most qualified publicists.

With the International Law, its sources might be broader than the sources of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL). Regarding International conventions or treaties as a source of the International Humanitarian Law, there are two main treaties as main sources of the International Humanitarian Law, including The Hague Convention in 1907 or known as the “law of the Hague”, and The Geneva Conventions (GCs) known as the “law of Geneva”.[13] With The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, it could be considered as a set of rules regulating the conduct of hostilities, complying with the rules of engagement. In this sense, it can be seen the relations between The Hague Convention and The Geneva Convention that such rules of the Hague later improved and gone through the fourth Geneva Convention and additional Protocols. Relating to the four Geneva Conventions, its applicability has been universally accepted through the ratification.[14] The four Geneva Conventions grant protection to the categorized vulnerable group, which is considered to be different from each other. The First Geneva Convention (GCI) was established with the purpose in protecting the wounded and sick. The Second Geneva Convention (GCII) was created with the aim to provide protection to the wounded, sick and shipwrecked in the armed-conflict at sea. The Third Geneva Convention (GCIII) aims to provide the protections to Prisoners of War (PoW). Last but definitely not least, the fourth Geneva Convention (GCIV) aims to protect the civilians in the armed-conflict, including anyone who live under the occupation.[15]

As one of the primary sources of the International Law, the Customary International Law (CIL) consists of two essential elements, including the objective element as state practice and the subjective element as opinion rurissivenecessitatis[16]. State Practice can be referred as the practice of state for sufficient duration of time and has been accepted as law from many other states, which is, to sum up as a practice with continuity and uniformity of usage.[17] It is the same thing applying the Customary International Law (CIL), the Customary International Law (ICL) contains elements of general practice as law and opinion juris. Importantly, the so-called Customary IHL has played a very significant role in the armed-conflict because it helps to fill gaps where the International Human Rights Law (IHRL) could not afford to apply, especially to enhance the protection of victims.[18] Linking the relation between The Hague and Geneva Conventions and its Additional Protocol to the Customary IHL, such conventions and rules could also be considered and accepted as Customary International Law.[19] In this regard, acknowledging the recognition from most of the states, Hague especially Geneva Conventions and its Additional Protocol as the Customary IHL undoubtedly have developed as the important key sources of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL).

The General principle of law and the judicial decision and teachings of the most qualified publicists as the secondary or subsidiary sources, they are also playing an important role in the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) as the General Principle of Law recognizes the Jus Cogens norms[20] such the principle of prohibition against Genocide, Slavery or Torture, which granted non-derogable obligations to all states; and the judicial decision as the court plays its role in interpreting IHL.[21]

Throughout the past period, the UN peacekeeping operations have been engaged in many countries to ensure the International Peace and Security which some of them already succeeded and some of them are remaining to exist until nowadays (Table 1).[22] On the one hand, the term “Peacekeeping Operation” should be firstly defined and understood so that the deeper explanation could be easily understood. The Peacekeeping Operation is the operation that has been considered as one of the effective tools for the United Nations in helping the host countries to get out of the difficult circumstance like from the complicated conflict to peace.[23] Basing on its legitimacy and uniqueness, the peacekeeping bears the burden sharing and ability to deploy troops and police which are contributed by the member states from around the world on the voluntary basis in order to operate such various mandates.[24] As mentioned above that the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) aims to protect persons who do not involve, and no longer to be part of hostilities.[25] Hypothetically, the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) is considered as relevance to the UN Peacekeeping Operations since these operations are deployed in the post-conflict period which the presence of violence may be occurred and ongoing, or conflict possibly reignite. By saying that the IHL as relevance to the UN peacekeeping Operation because the presence of the violence or hostilities during the conflict, it might not be an enough ground to the application of the IHL to the UN personnel. However, the conducts of the UN personnel during the operation would attribute to the application of the IHL to the operation or UN personnel itself. As a result, the UN peacekeeping may potential be placed under the scope of application of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL).

Source: The Department of Peacekeeping Operations and Department of Field Support and Department of Management, January, 2017.[26]

With the Peacekeeping Operations for over the six and a half decade, the UN Peacekeeping Operations have been transformed fundamentally from its nature and purpose.[27] It undergoes the transformations by five generations which will be discussed in this section, including the first generation: traditional peacekeeping, the second generation: civilian tasks, the third generation: peace enforcement, the fourth generation: peacebuilding, last but not least the fifth generation: hybrid missions.

Referring to the first generation, the Peacekeeping operation that had been engaged during the cold war was the traditional one, which is occurred only to keep peace or end armed-conflicts by ceasefire.[28] The first generation operation are lightly armed with the strict rules of engagement, by operating its mandate under Chapter VI of UN Charter. Such restriction on the nature of operations were made because of the relationship between the principle of state sovereignty and Human Rights during the Cold War period.[29] Due to the nature of peace operations at that time, the peace operations were deployed under three basic principles, including the consent of the host countries, the principle of impartiality which is no discrimination between the conflicting parties, and the prohibition of the use of force from the United Nations.[30] One of the best example for the first generation of peace operations is the mission in 1948 “the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO), which were deployed as an unarmed observer in the Middle East during the conflict between the Arab countries and Israelis on the ground of new emerged state “Israel”, with the main purpose to just reach the cease-fire agreement between the conflicting parties.[31]

Regarding the second generation of the peace operations, the nature and extent of operation itself have been transformed because of the end of Cold War changing in the International Politics. Due to the end of the Cold War, there have been much demands and supplies for peace operations.[32] During the Cold War and post-Cold War, many people suffered from the famines.[33] The first generation of peacekeeping operation was not easy to deploy, which lead to the development of the second generation of peacekeeping operation which is easier to dispatch. However, the mission was sent to more complex and dangerous situation. Developing from the first generation, this second generation added up the civilian tasks, such as the humanitarian aid, the promotion of human rights, Capacity building on the government system, organizing the election, and disarmament and reconciliation.[34] There are several missions from the second generation, such as the United Nations Transition Assistance Group which is known as the UNTAG in Namibia, the UN Observer Group in El Salvador (ONUSAL), and the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC).[35]

With the third generation of a peace operation, the transformation of nature of peace operations to peace enforcement, with the increasing of permission to use force to fulfill the mandate of the operations. This generation of a peace operation is different and developed from the first and second generation by being deployed under the Chapter VII of the UN Charter. With this generation, the increasing of permission to the use of force directly resulted from the moral after the three failed missions in Rwanda, Somalia, and Bosnia, which seems to encourage the shift in balancing the principle of non-intervention and Human Rights.[36]

Developing to the fourth generation of peace operations as peacebuilding, it combines the permissiveness of use of force with the civilian tasks, which is also known as state-building. With its nature and complexity of its mandate, it led to the remarkable increase in numerous of organization and other actors involving into the peacebuilding operations,[37] including the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), UN specialized agencies, and International financial institutions.

Last but definitely not least, the fifth generation of peace operation which develops to the hybrid missions respond to the complex context. The United Nations shared its job with the regional organization in order to fulfill the mandates. Such Missions under mandates of the UN Charter are carried out by the regional actors, including NATO, African Union (AU), and European Union (EU).[38] This generation of peace operations deploy military and police personnel under mixed commands of both the United Nations and regional organization deploying military personnel to the same operations, but with separate command and form of mandate.[39] For example, the hybrid mission of UN African Union Peacekeeping Operation (UNAMID), under the Chapter VII of UN Charter and authorized by the Security Council.[40]

Owing to its nature, the Peacekeeping operations are considered to be part of the institutional structure of the United Nations, which is known as the subsidiary organ of the United Nations by the Article 7(2) of the UN Charter.[41] The Peacekeeping missions are operated under the Department of the Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) which is established in 1992 by Boutros Boutros Ghali as Secretary General of the UN, with the purpose to assist the state parties and the Secretary-General in maintaining the International Peace and Security.[42] With the political and executive instruction, the DPKO can operate its missions around the globe and keep contact with the Security Council, financial and troop contributing countries, and the conflicting parties. Particularly, the DPKO also provides support, and formulate policies or guidelines on military and police personnel, and mine action.

Regarding the UN Peacekeeping Operation, there are several actors involving in the Operations, including the United Nations (UN), the Troop Contributing Countries who send their military contingent for missions, and the Host state[43] where the operations will be taken place.[44] Importantly, there are four main offices of the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO), including the Office of Military Affairs, the Policy Evaluation and Training Division, the Office of the Rule of Law and Security Institutions, and the Office of Operations. The Department of Peacekeeping Operations is working under the Secretary General who will provide the general instruction and the general political guidance. However, the United Nations Security Council still will be the one who has the utmost authority on the operations and have the power to decide whether the deployment of military contingent is continued.[45] Looking for the main role, the Office of Operations is running to assist the Secretary General in formulating strategic policy or guidance, provides support to the missions. The office of the rule of law and security institutions was created in 2007, with the purpose to improve the links and the coordination of the department’s activities in the extents of police, justice, security reform, reconciliation between the conflicting parties, mine actions, and disarmament. The Policy Evaluation and Training Division aims to disseminate policy or guidelines, coordinate and operate standardized training programs, especially to evaluate the progress of the ongoing mission’s mandate and formulate policies and framework for the cooperation with the external partners. Lastly, the office of the Military Affairs is tasked to deploy the best military competency in fulfill the mandate of the operations, to improve the performance and effectiveness of military factor in the UN Peacekeeping Operations. During the operations, the authority over the military command is given to the Force Commander who will be on behalf of the UN Secretary-General. That is the reason why the Secretary-General will appoint the Force Commander by himself.[46] In any case that the operation is involved with the serious civilian tasks, a Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG) will also be appointed by the Secretary-General, alongside with the Force Commander. However, the responsibility between the two will be in detail in the internal document.[47] The Commander of the force will be the one who is responsible for watching over the good conduct and discipline of the Force in the Operations.[48] However, there is a problem concerning on the conducts and disciplines of the UN personnel over the issue of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse on the Women which will be discussed in the next section.

As mentioned and be known that Women has been considered to be in the vulnerable ground of the society, both domestic and International legal framework has played a significant role in protecting women from the abuse and violation of their rights. After the World War II (WWII) in 1945, the United Nations, as one of the International Legal frameworks, had been adopted in order to maintain the International Peace and Security[49], especially the charter has also set out one of its goals to endorse faith in the fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, especially in respect to promoting the human rights and the fundamental freedoms.[50] Before examining and analyzing the International Legal frameworks regarding the Women protection, the term “Sexual Exploitation and Abuse” must be defined and explained instantly. As a result, the next section will be focus on the definition of the term “Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA)”, the development of the International Law of the prohibition of the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA), last but definitely not least the Scope of application and standard on the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA).

Since the problem of the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse has never been considered as new, but it still remains a serious challenge for the International Law. After the World War II ended up as a tragic historical record, there has been a development of the International Law resulting from the new emergence of the new actors or subjects of the International Law.[51] With the negligence of the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunal in prosecuting the crime of sexual violence, the tribunal of former Yugoslavia and Rwanda was in successful to prosecute different crimes of sexual violence, such as Genocide, Crime Against Humanity (CAH), Torture, Enslavement, and War Crime.[52] The Vienna Conference concerning on the Human Rights was held in 1993 to contribute to the change of traditional view and mark a great attention to the sexual crimes. It could be seen as one of the success effort on the Women’s rights to end the Women’s Right violation. With the conference in 1993, the declaration and action plan regarding the elimination violence against women and specified types of sexual harassment and exploitation (such as from International trafficking in person or prejudice of culture) were issued and considered as the violation of human dignity.[53] In the International context, this legal framework has borne purposes in protecting women and girls in/during armed conflict and post-conflict, especially to undermine the impunity for those who committed such crimes that have mentioned above.[54] With the advancement of the existing norms and new standards concerning the Women’s Rights, there had been another development of Women’s rights by the United Nations Security Council adopting the Resolution 1325 in 2000 regarding the Women, Peace, and Security. This Resolution aimed to protect the rights of women and girls during the conflict and post-conflict from such crimes such as rape and other sexual exploitation and abuses, with the full implementation of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) as well as the International Human Rights Law (IHRL).[55] Taking another step of the development in 2008, the Security Council issued Resolution 1820 concerning the sexual violence in the Armed-Conflict, emphasizing and ending the sexual violence as a tool of war to degrade, dominate, and force evacuation of civilian of local people and ethnic group.[56] Besides, Resolutions adopted by the General Assembly and Security Council concerning on the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse, there are many other International Legal instruments on such problems. The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) has also played a significant role in bringing justice and impunity by prosecuting crimes related to Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) under the International Law.[57] The International Legal instruments such as “The Hague Convention,” and “The Four Geneva Convention” could be known as the main sources of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL).[58] In the sense of the relation between the IHL and IHRL, the IHL grants protection to women and girls within the time of Armed-Conflict, which is complemented by the IHRL during the peace time where the protection granted by the International Humanitarian Law reaches its limitation.[59] Such Legal protection of the Women’s Rights could be found under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (the so-called CEDAW), and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Such the International Legal Protection under the International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Law that have mentioned above will be discussed in detail the latter section of this chapter.

In the sense that Sexual Exploitation and Abuse still remains a challenge for the International Community to handle, it has been considered as the serious violation of the Human Rights.[60] With the definition of the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse, it is divided it into two violations, including the “Sexual Exploitation” and “Sexual Abuse.”[61] Owing to the definition of the Sexual Exploitation, it is defined as any activity or attempt of the abuse toward the vulnerability or vulnerable group[62], and the abuse of differential power and trust for the purposes of sexual activity, including benefiting socially, politically, and monetarily.[63] Besides, according to the Secretary General’s Bulletin, Sexual Abuse is defined as any act or threats of a sexual nature physically regardless by forces, in a coercive situation or under unequal condition.[64] One the one hand, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the sexual abuse is considered as any coercive actions in a range of physically, sexually, and psychologically conditions toward women at all ages, particularly it also includes any forms of non-consensual sex such as sexual exploitation and harassment.[65] Based on the definition above, the definition of the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) can be simplified as any acts involving the sexual activities for the purpose of exchanging money, food, shelter or other goods toward the vulnerability or someone in the vulnerable group, whether threatening or forcing under the unequal positions and conditions.

Any Sexual Exploitation and Abuse committed by an International or National United Nations personnel and anyone working under the organization’s mission, it would be considered as a serious misconduct and might be fall under the disciplinary measures. In this sense, having a sexual relationship between UN personnel and beneficiaries of such assistance are not discourage due to the fact that the differential in power and position would be abused. Such acts of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) are listed as below:[66]

- Having Sexual intercourse with anyone under 18 years old would be prohibited, even with the consent,

- Having Sex trade[67] would be resulted in punishment,

- Having exchange of sexual acts for the humanitarian assistance[68] is prohibited,

- Any force, threat or coercive action for sexual intercourse is prohibited.

- Case Study of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse of United Nations Transnational Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC)

As the definition of the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse has been provided in the last section, it would be more informative to study on the case of United Nations Transnational Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC). For the first step to understand the UNTAC, there was a historical reason behind its establishment. Cambodia had never been in a stable condition for decades because of persistent conflict and human rights abuse within the country.[69] During the regime of the Khmer Rouge ruling Cambodia (1975-1979), there were approximately 1.5 million deaths[70], including living in famine, starvation, and diseases.[71] In 1979, Vietnam invaded Cambodia with the purpose of driving the Khmer Rouge out of the country. After then, the new government was established, changing the regime to the People’s Republic of Kampuchea. After this new government lasting for twelve years, it was challenged by the two forces such as Front Uni National pour un Cambodge Independant Neutre Pacifique Et Cooperatif (FUNCINPEC, the royalist faction to the former king Norodom Sihanouk), and KPNLE force. These forces were supported by China, the United States (US) and the Association of Southeast Asia Nations (ASEAN), while the new government was backed by Vietnam and the Soviet Union.[72] This led to the instability in the country, including the refugees along the border of Cambodia and Thailand. However, the peace talk initiated in 1988, and the new government was established by changing the name to the State of Cambodia (SOC). Cambodia had not been in a stable condition yet until the peace agreement was signed in 1991 which is known as the Paris Peace Agreement.[73]

From the agreement allowing the United Nations (UN) to deploy their troop to Cambodia, it led to the establishment UN peacekeeping operation in 1992 which was known as United Nations Transnational Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC). Without talking much about the political thing, the United Nations Transnational Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) made its biggest achievement in May 1993, which was the successful free and fair election in Cambodia.[74] However, at the same time, there were many cases of the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse in Cambodia because of numerous sex houses and prostitutes (including child).[75] With the presence of the United Nations Transnational Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC), it had been a notice that there has been an increase in a number of prostitutes from 6000 to 25000 after the deployment of UNTAC.[76] The UN peacekeeping troop were seen going into the brothels and having sexual activities with the prostitutes, and this rose a problematic of the rise of prostitutes in Cambodia.[77] Alongside the rise of prostitutes, the UNTAC also caused a very significant mistake of all times which was to leave a high rate of HIV/AIDs in Cambodia.[78] However, the United Nation did not take any action or response to the problem of the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA).[79] It could be understood the reason behind through the unclear definition of the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) and the Statute of limitation.

As discussed in the section “Definition of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA)”, the definition was officially given through the section 1 of the 2003 bulletin. As being argued by Professor Whitworth Sandra, the Sexual Exploitation during the United Nations Transnational Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) was not a Sexual Exploitation and Abuse[80], and did not fit to the definition of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) given under the section 1 of the Special Measure for Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse[81]. The Statute of limitation is rule and law that prevents prosecutors from charging person with a crime which was committed from years ago.[82] Through this, the sexual exploitation during the UNTAC was occurred in 1992-1993, not even existence of the Special Measure for Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse yet. In consistent with the principle of the non-retroactivity in the international law, the effect of the present law or rule would not extend to the past committed crime and would not be able to pass the judgment on the circumstance before to its implementation.[83] From this reason, the definition of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) was given by the 2003 bulletin. However, the sexual exploitation during UNTAC was occurring in 1992-1993. Therefore, basing on the principle of the non-retroactivity in the international law, the 2003 bulletin would not have any effect on such case, even the sexual exploitation during UNTAC was not matched to the definition given in the 2003 bulletin.

With the current issue in the International Community, the issue of the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) involved by the UN personnel to the local people tend to emerge due to the drastic increase of UN Peacekeeping Operations.[84] With such a problem, the cases of UN personnel’s serious misconduct slowly exposed to the International Community through media and Human rights reports or NGOs annual reports.[85] Involving in the SEA and human trafficking, the UN peacekeeper was exposed in the 1990s with the case of Cambodia. However, it was dismissed due to the ground of insufficient evidence.[86] Besides, the case of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) also happened in Kosovo and Bosnia, along with the reports produced by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) about the Sexual Violence and Exploitation in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra-Leone indicating that SEA was frequently committed UN peacekeeping personnel and local NGO.[87] With the Special measures for Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse issued by the Secretary-General’s Bulletin, it applies that such application of the present bulletin applies to all the staff of the United Nations, such as to all staff from different administered organs or programmes of the UN.[88] Particularly, the act of committing crime of the SEA by the UN peacekeeping personnel weakens the very strict rule of conduct or ethics of peacekeeping. True, the UN peacekeeping missions are mandated to ensure peace and security, especially to protect civilian.[89] However, involving the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse with the local civilian or people breaches the International Laws, particularly the ethical conduct of the peacekeeping unit. In addition to that, such matters going through media which weakens the reputation of the United Nations, as well as the loss of trust from people within the International community.[90] As a result, the UN Peacekeeping personnel operating missions under the command and control of United Nations shall not commit any acts of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA), and bears a particular responsibility to protect women and children.[91] Regarding the command and control under the United Nations, there are some set ethical conducts and standards of conduct for the UN peacekeeping personnel, which will be discussed in detail in chapter 3 of this dissertation.

Seeing women as one of the vulnerable group, the protection of their rights are easily violated during the armed-conflict and post armed-conflict. Then, the question often arisen where are the international legal framework that grant legal protection to the women under the International Law? As discussed about the inter-relations between the IHL and IHRL that the IHL is, to the extent where it could not afford to apply due to its limitation, is complemented by the IHRL. To illustrate the legal protection granted by the International legal framework, this dissertation will indicate and divide the legal protection under the International law into two aspects, including the Women Protection under the International Humanitarian Law (IHL), and the Protection of Women under the International Human Rights Law (IHRL), which both of them will be discussed in details with the next sections of this chapter.

Under the International Humanitarian Law, it is served to prevent human from suffering from war due to based gender issues. However, the current challenge is different from the old day’s problem that women as vulnerable people during the armed-conflict and post armed-conflict still face certain problems,[92] and this sexual violence or Sexual Exploitation and Abuse has been considered as as a current challenge for the International Community. Under the International Humanitarian Law, there two main International Legal instruments granting protection for Women, such as the Hague Convention and Geneva Convention and its Additional Protocol.

The Hague Convention II in 1899, as a reference, was seen as the International codification of crime of sexual violence.[93] It later was also included in the Hague Convention in 1907, and it then expended through the development of the Geneva Convention 1949 and its Additional Protocols.[94]

Founded in the Geneva Convention, the women would be protected under the consideration as in the vulnerable group, with the article 12 of Geneva Convention stating that: “Women shall be treated with all consideration due to their sex.” From the protection of women, women, the same to all civilian or who are not considered to be part of the armed force, are protected from any abuse or any violence by the party of the conflict, or from the negative impact of the hostilities.[95] Owing the purpose of the fourth Geneva Convention relating to the protection of civilian persons in time of war, Women are protected in all circumstances as stipulated under the Fourth Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I (AP I) & II (AP II). The general protection for women or civilians who will be benefited from the convention, as stipulated under the article 27 of the Fourth Geneva Convention:

Article 27:

Protected persons are entitled, in all circumstances, to respect for their persons, their honour, their family rights, their religious convictions and practices, and their manners and customs. They shall at all times be humanely treated, and shall be protected especially against all acts of violence or threats thereof and against insults and public curiosity.

Women shall be especially protected against any attack on their honour, in particular against rape, enforced prostitution, or any form of indecent assault, […][96]

With this provision, it indicates that Women as a protected person shall be protected in all circumstance, against any acts of violence, insult, threats, and others related acts. In addition to that, it indicated in the second paragraph of the article 27 that it would be a violation the International Humanitarian Law for such practices which numerous of women from infancy to old age were forced to involve into the sexual activities with any consent, including rape, sexually brutal treatment, or sexual exploitation and abuse. Particularly, around based or headquarter of troops or UN personnel were located, even when they get through or pass by, tremendous amount of women were forcibly asked to have sexual intercourse which go against the wills of the victims. As a result, such mentioned acts are prohibited under the Geneva Convention.

Owing to the uniqueness and independent characters of the IHL and IHRL, both of them still remain to complement each other so that the protection of human being would be ensured. Under the International Human Rights Laws, there are several international instruments which grant protection for women from the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA), like the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). In any case that the UN personnel involve in the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse by using differential power between them and women, they are considered to violate women’s rights which granted by the conventions above.[97]

The legal protection of Women also grant from the Convention on the Rights of Child (CRC). The issues of the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse do not occur only on the women, but also girls who have been forced to engage in the sexual intercourse during the armed-conflict, even happen during the UN peacekeeping operations. From the stretch, Women and girls are protected by the convention through the local authority or government, which is already stipulated in the article 34 of the Convention:

States Parties undertake to protect the child from all forms of sexual exploitation and sexual abuse. For these purposes, States Parties shall in particular take all appropriate national, bilateral and multilateral measures to prevent:

a. The inducement or coercion of a child to engage in any unlawful sexual activity;

b. The exploitative use of children in prostitution or other unlawful sexual practices;

c. The exploitative use of children in pornographic performances and materials.[98]

As a result, the member states of the convention protecting child from the SEA bear responsibility take all necessary measures in order to ensure the legal protection of women and girl under this convention.

With the tragedy history of the great barbarian invasion and the World Wars, tons of the women and children still lives in fears and physical or mental scars of the treatment.[99] It wakes the conscience of all humankind and emphasizes over the necessity of the women protection that Women shall be treated in accordance with the special consideration or protection due to their sex.[100] Certain acts such as forcing women to involve into the immorality by using violence or threat and any acts which would lead to any form of sexual assault are constituted as a violation on women’s honour, rape, and enforced prostitution. These mentioned acts are prohibited in any places and all circumstances, and women are protected in accordance with the paragraph 2 of Article 27 of the Geneva Convention.[101] The protection which granted to women regardless of the nationality, beliefs, age, race, religious, status or social conditions shall be respected for their dignity as women.

CHAPTER THREE: THE APPLICABILITY AND OBLIGATION OF THE UN PEACEKEEPERS OF THE INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW TO THE PEACE OPERATIONS

From scratch, it has been contested that the United Nations is not bound by the treaties of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) since the United Nations itself does not constitute as a state who possesses rights and duties as a state possesses such as juridical and administrative powers, especially not a party to the four 1949 Geneva Convention or their Protocols. On the other hand, it does not mean and has been no longer an excuse that the conduct of the UN forces are staying out of the humanitarian constraint or the IHL considerably does not apply.[102]

Besides from contesting over the application of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL), the rule of customary International Humanitarian Law are universally applicable to states, International Organizations (IOs), or Individuals, which rules are included to apply to any types of armed conflict.[103] With the notion of armed conflict, there are two types such as International Armed Conflict (IAC) and Non-International Armed Conflict (NIAC). However, since the missions are deployed to the foreign country in the peacekeeping areas, it is not necessary to discuss the Non-International Armed Conflict (NIAC).[104] According to the Article 2 of the 1949 Geneva Convention, it provided that:

In addition to the provisions which shall be implemented in peacetime, the present Convention shall apply to all cases of declared war or of any other armed conflict which may arise between two or more of the High Contracting Parties, even if the state of war is not recognized by one of them.

The Convention shall also apply to all cases of partial or total occupation of the territory of a High Contracting Party, even if the said occupation meets with no armed resistance.[105]

Based on the provided article, it concerns on the “High Contracting Parties” only, who has ratified the 1949 Convention. This means that the parties concerning to the International Armed Conflicts are limited to states only. However, with current international practices and legal concepts, it slowly acknowledges the qualification of IOs as to become a party to the International Armed Conflict. Under the UN Charter[106], UN using its armed force to stop and prevent aggression and to maintain the International Peace and Security would also become a party to the International Armed Conflict.[107] By doing so, the UN signs an agreement with the host state so that the UN can send its force to operate the mission, and the rule and principles of the International Humanitarian Law could be inserted through the Status of Force Agreements between the United Nations and the Host States.

A Model Status of Force Agreement (SOFA) is considered as an agreement made between a host state and a foreign state (or International Organization, United Nations as a best example), in which a foreign state stations its military forces in a host state in order to follow the mandate of the UN Peacekeeping Operations.[108] Concluding the SOFAs or Status of Mission Agreement (SOMAs), it derives from the practical lesson from every each mission from the past period.[109]The Model State of Force Agreement (SOFA) has been playing a significant role and instrument in establishing conditions of the function of the operations to be more effective and efficient, as well as to provide proper protection for the UN peacekeepers.[110] For the very time through the Status of Forces Agreements (SOFAs) in 1992, the application of International Humanitarian Law was included in the agreement which is known as the Status of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR).[111] It could be noted that the statement in the status of forces agreement between the UN and Rwanda include ensuring the respect of International Humanitarian Law by using the term “Principles and spirit of International Humanitarian Law” which would be used to govern the conduct of the UN peacekeeping personnel.

Through the Convention of the Safety of United Nations and Associated Personnel, it could be noticed about the application of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) to the UN peacekeeping operations as well. Time passing with the changes of situation and issues, the Convention was adopted by the General Assembly in 1994 because the UN peacekeeping operations have established to engage in the areas where the civil war or conflict is still occurring. With the adoption of the convention, it contributes to the security and safety of the UN peacekeeping personnel which is stipulated in the Article 20 of the Convention on the Safety of United Nations and Associated Personnel:

The applicability of international humanitarian law and universally recognized standards of human rights as contained in international instruments in relation to the protection of United Nations operations and United Nations and associated personnel or the responsibility of such personnel to respect such law and standards;[112]

Aside from the protection of rights of the UN peacekeeper, such provision recognizes the application of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and International instruments relating to the human rights. At the same time, it recognizes that the personnel bears the responsibility to respect such law and standards which the Convention on the Safety of United Nations and Associated Personnel recognize.[113]

During the meeting of the Intergovernmental group of experts for the protection of war victims held in Geneva 1995, the implementation and the dissemination of the International Humanitarian Law were recommended. By doing so, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) carrying out its mandate to disseminate the IHL work with UN organs, specialized agencies, and other regional organizations.[114] Right after that, the Bulletin on the Observance by United Nations Forces of International Humanitarian Law was introduced and issued by the Secretary General in 1999. With the content in the section 1 of the Bulletin on the Observance by United Nations Forces of International Humanitarian Law, it indicates the application of the principle and rules of the IHL in the Bulletin over the UN peacekeeping personnel in the circumstance the personnel are actively involving in the armed conflict as combatant[115] With such provision, in any case that the UN peacekeeping personnel are engaging in the armed conflict, it could be proved by the section 1 on the qualification of the UN peacekeeping personnel to become a party to the armed conflict. However, including such provision has been criticized by states because the main purpose of the TCCs sending their troop is to operate under the Chapter VI of the UN charter, not to engage in wars.[116] From my point of view, including such provision which is the ground of applying the IHL is a great opportunity in locating the UN peacekeeping personnel into the right position because they always claim as to operate under the principle of self-defence so that they can fulfill their mandate which somehow leaves impunity. In addition to that, it helps to regulate the conduct of the personnel since the nature of the UN peacekeeping operation keep shifting from the traditional peacekeeping to peace enforcement where it is allowed to use forces.

Owing to its nature and legal affect, the Bulletin on the Observance by United Nations Forces of International Humanitarian Law, it has a legally binding effect toward the UN peacekeeping personnel.[117] Comparing to the hundreds of pages of the Geneva Convention, the Bulletin seems to be very short and brief. From the Bulletin, it only mentions that every member of the UN peacekeeping operations are fully acquainted with the principles and rules of the International Humanitarian Law (IHL). However, it has not stated, under the Bulletin, what liability that the UN peacekeeper would be subjected to due to the breach and violation of the International Humanitarian Law. Instead, it has been mentioned under the section 4 of the Bulletin on the Observance by United Nations Forces of International Humanitarian Law that the UN peacekeeping personnel would be subjected to prosecute by their own national court in any case of violation of the International Humanitarian Law.[118] With such provision, it bars the host state from taking direct action to prosecute the peacekeeper, but to send the peacekeepers back to their home for the investigation and prosecution.[119] However, peacekeepers, most of the case, who were sent back for the investigation and prosecution were not trailed for the crime they committed. As a result, it left the victims from the violation of the International Humanitarian Law with inadequate remedy and injustice.

The legal status of personnel contributed by member states of United Nations deploying during the peace operations is in the reflection of the complicated legal status of peacekeepers. Legally, the legal status of peacekeepers is depended upon the mandates and purpose of the particular operations, and depended upon whether it falls under the International Humanitarian Law or other International treaties governing the peace operations. It could also be contested on the application of the International Humanitarian Law to the United Nations. As the opinion of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the United Nations is considered to be a subject of the International Law, with the capacity to possess international rights and duties.[120] This means to the rules of the International Law, including the International Humanitarian Law. Particularly, the model status of forces agreements between U.N and a host state also specifically add up for the respect of the International Humanitarian Law[121], which the UN peacekeepers is mandated. Importantly, Both the Report of the Panel on the UN Peace Operations and the Secretary General’s Bulletin on Observance by United Nations Forces of International Humanitarian Law (which will be discussed in the later part of this chapter) declare for the application of the International Humanitarian Law to the UN forces or personnel. Considering violations of the International Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law, the UN peacekeepers has committed crimes, including Torture, Attacks on civilian, especially the Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA) during the missions in Somalia, Kosovo, Bosnia, Mozambique, Haiti, East Timor, Congo, and Cambodia. True, as member states, they have a duty to respect the Geneva Convention in 1949, and the responsibility still remains even if the personnel is already sent to the United Nations Peacekeeping Operations. The UN Peacekeepers would be prosecuted by their respective states’ courts in the light of violation of the International Humanitarian Law.[122] Therefore, it should not be any problem in the application of the International Humanitarian Law in determining the legal status of the UN peacekeepers.

With the peace enforcement as a deployed operation, the status of the UN peacekeepers in the situation when the use of force is permitted is not hard to define. In such situation, the UN peacekeepers are considered as armed forces sending from the foreign countries involving in the armed-conflict. Therefore, they would be categorized as combatants under the Article 4 of the Third Geneva Convention and Article 43 of its Additional Protocol I. On the other hand, the status of the UN peacekeeper could be changed in accordance with its mandates, and even also the factual situation of the participation of the operations should be taken into account because the mandate where it aims to maintain the peace by using force in circumstance of self-defense only, which will be discussed in the next section of this chapter, is not really clear and difficult to determine.

Accordingly, the International Humanitarian Law has divided persons into two categories, including the Combatant or as a member of armed-forces of the conflicting parties, and Non-Combatant or Civilians.[123] Reflecting the International Humanitarian Law, the UN peacekeepers may be classified as civilians.[124] However, it could also contest over the legal status of the peacekeepers as civilians due to the connection of the personnel with the United Nations (UN) and the Troop-Contributing Country (TCC). With the presence of the forces of foreign entities in the territory in the circumstance that the armed-conflict is still occurring, they would be considered as combatants.[125] On the other hand, if peacekeepers are not involving or participating in the hostilities, the United Nations and Troop-Contributing Country are not considered to be part of the conflict. Then, the connection between the peacekeepers and UN and Contributing Country is nothing to affect the status of the peacekeepers, unless the mandate of the operations is a mission with an enforcement action. As not one of the party to the conflict, the Status of the UN peacekeepers will be as civilians under the IHL,[126] with certain protections, which will be discussed in the following section. Any means of capture, killing, or injuring are prohibited and the personnel would be placed under the protected status by using the sign, emblems and uniform of the United Nations.[127] With another point of view, the peacekeepers could also be considered as combatants if they are taking part or participating in the hostilities. This would present the UN and TCC to be a party of the conflict, so peacekeepers are no longer protected and their legal status shifts from civilians to combatants.[128]

Aside from the providing legal status of the UN peacekeepers under the International Humanitarian Law (IHL), Various U.N Documents contribute to the definition of the legal status of UN peacekeepers, as well as to see whether the legal status of the UN peacekeepers under the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) has been assigned appropriately.

There are two milestone documents of UN concerning the legal status of the UN Peacekeepers, such as the Convention on Safety of United Nations and Associated Personnel, and the Secretary General’s Bulletin. With the 1994 Convention on the Safety of United Nations and Associated Personnel and its Optional Protocol in 2005, A specific legal basis of protection for peacekeepers involving in the UN Peace Operations. From the Convention on Safety of United Nations and Associated Personnel, it established that those who are taking part of the UN peace enforcement operations established under the Chapter VII of the U.N Charter are considered as combatants. However, the peacekeepers are also protected and criminalize certain act against the United Nations or Associated Personnel under the Article 9[129] of the 1994 Convention on the Safety of United Nations and Associated Personnel, including murder, kidnapping, threat or violent attack against the United Nations or associated personnel. At the same time, the Bulletin on the Observance by United Nations Forces of International Humanitarian Law is also on the line to determine the legal status of the UN peacekeepers. Under the section 1 of the Secretary General’s Bulletin, the present rule applies to the United Nations within the armed conflict in which the peacekeepers are involving actively so as to become combatants or enforcement actions, and in the operations in which the use of force is allowed but only in self-defence.[130] In other words, even in the situation that the peacekeeping operation is mandated to use force only in self-defence, they may be considered as combatants if they are involving and engaging actively in the armed conflict.[131] Thus, the legal state of peacekeepers as protected civilians could be drawn depending upon their participation during the armed conflict.

From the protection of the UN peacekeepers in Peace Operations, the UN peacekeepers of the contributing states operating in a host state’s territory hold a special legal status.[132] Their special legal status is the immunity granted by the 1946 Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations, which the Peacekeepers shall enjoy the granted immunities from the legal process so that they can fulfill their tasks and mandates.[133] This immunity of the peacekeepers during the operation derives from the International customary law rather than the Status of Force Agreements or the Status of Mission Agreements itself. This Principle of Immunity not only applies to organs of states, but also to the military or civilian staffs of the United Nations (UN) or other regional organizations enjoying the International legal personality. With even the personnel contributed by the contributing countries, most of the operational control, not full command, may be still exercised by the United Nations. True, the peacekeeping personnel enjoy the granted immunity. However, it might be lost in any case of wrongful acts, and the Troop Contributing Countries (TCCs) would be accountable for their national military contingents. Besides enjoying the immunity, under the rule 33 of the Customary International Humanitarian Law, the legal status of peacekeepers would be regarded as protected civilians.[134]

Under the Capstone Doctrine, it regulates the general principle of the conduct of the United Nations peacekeeping operations as well as their function leading to the success of the operations.[135] With the core value in the tasks of the operations, every peacekeeper has obligations to ensure impartiality, Integrity, Respect, and Loyalty which all of them will be discussed and explained in the following sections.

Every UN peacekeeper has to remain impartial at all times, by not being favorable to any party of the conflict and being preferential or supportive to any group of the host state. By doing so, the UN peacekeepers have to understand the main mandate of the operations and follow any directives and operational instructions. One of the most important obligation is that every UN peacekeepers must not take any actions that would likely to jeopardize the mandate or legitimacy of the operations.[136]

To build the integrity, UN peacekeepers must be honest at all times, with the ability and competence to respect the morality. It has been considered to be very essential to have a trustful relationship with the population of a host state. Therefore, Peacekeepers must behave themselves and act professionally. By doing so, Peacekeepers, at all time, have to remain in a proper dress, conduct themselves in accordance with the professionality and disciplines, and have to refrain from any form of misconduct such as negligence, or violation of Human Rights or any other relevant applicable rules. [137]

Last but definitely not least, as one of the important general principle that every UN peacekeepers have to keep in mind. UN peacekeepers have to keep to be royal to the objective and goals of the UN which are to maintain International Peace and Security, and the mandate of the operation. Peacekeeper has to balance the conflict of interests by always standing in the UN’s Interests. Thus, Peacekeepers have to show themselves to achieve the goals of operations and United Nations, regardless of their personal interests.[138]