How Does Urban Planning Influence Gender Equality?

Info: 6054 words (24 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

INTRODUCTION

Social structures affect physical structures, and gender norms have always been reflected in the planning of cities. This creates unequal opportunities to be represented in public spaces. For example, 50 percent of a city’s public spaces consist of streets, where men constitute the norm as users of this space (UN-Habitat, 2016). Even though women have reclaimed space in the public sphere during the past century, women are still underrepresented in public space today. This consequently increases economic instability and does not help to achieve the goals of social sustainability. Thus, to a create safe and inclusive city, city planners need to uncover the power of gendered-planning.

According to traditional gender stereotypes, a home was regarded as a woman’s place to be, whist men dominated public spaces (Fainstien & Sevon, 2005). This division and dichotomy between private and public, women and men, has for a long time been deeply rooted in society. Such connection between private and public policy was that of a regulatory manifestation, as well as making sure that sexual relations only occurred between husband and wife, and that children went to school. The need for women-focused solutions in cities becomes clear when one looks at how they have been ignored in urban planning and design. The built environment – including the accessibility of public spaces, zoning for housing and transportation design – can marginalize women and jeopardize their safety.

According to the American Planning Association and Cornell University’s Women’s Planning Forum, women use cities differently from men in many ways; as such they have higher poverty rates and different housing needs, nonetheless are still “responsible for the majority of housework and childcare” and “have unique travel behaviour related to their combination of work and household responsibilities” (Abbey-Lambertz, 2016). Some the challenges women face may seem simple, such as having to navigate poorly maintained sidewalks or stairs with a stroller or use restrooms without sanitary waste containers. But many more are consequential, such as avoiding public transport rather than facing conditions, like desolate and poorly lit bus stops, that make them feel unsafe.

In the planning process, women are a under-prioritized group. At the same time, this is not a homogeneous group. More layers of social identity can be added to the groups marginalization. For example, class, age, ethnicity and sexual orientation are identities that can enhance discrimination. An intersectional perspective which acknowledges these overlapping layers of social identities is therefore of important in this thesis. UN Sustainable Development Goals number 5, 10 and 11 – gender equality, reduced inequalities and sustainable cities and communities respectively – are about achieving more equal cities. (United Nations, 2017). However, none of the sub goals emphasize the fact that everyone should have the same right to use and appropriate urban spaces. A fundamental aspect of a democratic society is that everyone is able to be part of shaping the city and to use its public spaces. A specific focus on the underrepresented group of women is therefore needed.

The structure of the thesis is as follows.

Background to the research

QUESTION

How does urban planning influence gender equality?

PURPOSE

The problem of why and how women have been underrepresented in the built environment has historically been overlooked in planning decisions, leading to marginalization and decreased participation of women in society. The purpose of this thesis is to discuss urban planning and development from an intersectional feminist perspective, and explore how urban planners can design cities that people either encouraged discourage certain individuals or groups. Further, this thesis attempts to close the gap between theory and practice in gender-equal opportunities in planning and development.

The thesis claims that urban form influence how cities are perceived and use, meaning that urban form effect, or even controls, the behavior of those who participate in it. Norms and power structures have long existed in society and tend to become manifested in built environments, which in turn influences urban life of inhabitants and creates exclusions from public spaces for marginalized groups, such as women. Thus, there is a need for a specific focus on this group, to explore how the design of cities constitutes unequal opportunities and possibilities for marginalisation.

AIM

The aim of this thesis is to identify the relationship between the design of cities and women. This relationship is explored and discussed through the study of the master planned community of Springfield Lakes, Brisbane by assessing the different feelings to certain spaces. In this way, urban form is explored as a tool to achieve just cities, through a feminist lens.

By joining the feminist perspective, this thesis aims at contribute to the debate surrounding more equal cities. However, it must be noted that this thesis does not solely portray the view that women are underrepresented in urban space, though sets out to review the evidence behind the statement. The primary objective of this thesis is to explore whether positive outcomes are achievable within the context of urban planning from a feminist perspective, and whether design features assist in this process. The second objective of this thesis is to assess whether Springfield Lakes is perceived as a gender-inclusive city or opposed to. In doing so, the following questions will be explored:

- What are feminist approaches to urban planning and design?

- What are the differing perceptions, if any, of feminist urban planning in the context of Springfield Lakes?

Another important aspect of this thesis, and therefore the third objective, is to identify some of the advantages and challenges in developing Springfield Lakes for both men and women. By doing so, this will further contribute to the discussion and recommendations that will be offered in the latter part of this thesis.

Theoretical framework

In this part the theoretical framework behind the study is presented, which acts as a foundation for the research within this thesis. Theoretical concepts related to the just cities (the goal), intersectional feminism (the perspective) and urban form (the tool) are analysed as the basis for understanding the empirical data.

JUST CITIES

As a result of the strong urbanization trend, the city is in focus now more than ever. There is a wealth of literature concerning the values, shortcomings and challenges that cities are facing. However, the representation is contrasting and complex where the city is described as the future but but also a place where problems and conflicts become most apparent (Elander and Aquist, 2001).

One fundamental aspect of society is that everyone should be equal and be able to use its amenities. It can be argued that a man’s needs are seen as a norm in society and that women and their needs are seen as inferior to men. The differences between gender in terms of power and privileges is something that needs to be highlighted in order to change prevalent conditions in society. Though, how does one highlight these disparities without consolidating them further. This is the dilemma that feminist scholars have debated with for a long time. How can the gender inequalities be highlighted without further becoming deepened?

Planning professionals (urban planners, policy makers, architects) play a key role in shaping cities. Principles and practice of professional planning is guided through education, and derived by society. However, issues around gender are often ignored in urban planning and can lead to social exclusion and marginalization of women’s participation in society. In exploring the built-form of cities, it can be concluded that cities are essentially “malestreamed” by evidence of how women’s needs and issued are not addressed in terms of housing, social supports, safety and public services (Ross, 2009). Fundamentally, cities had been historically designed to meet the needs of mainly “young productive men”; where women lived and worked at home as caregivers (Beebeejaun, 2017). Thus urban planners lack the awareness of the unique needs of women and this is the main reason for insensitive design that women encounter today. Ross (2009) and Hayden (1984) suggest women face many increased demands, inside and outside the home, and the built environment does not reflect this; nor has done a good job in making a woman’s life easier. For example, a woman’s daily jobs might be as follows: Home – School – Work – Shops – School – Home. The problem is that of daycare centres and education facilities not located within close proximity to employment centres and basic services, and rarely operate outside of the standard hours of 7am to 6pm. Hayden (1984) assert that “women are subject to daily harassment in trying to coordinate work hours and commuting schedule within the hours of these facilities”.

This brings about the topic of a just city. Fainstein (2009) suggest that justice is one of the core elements of a good city and calls for a sustained discussion among planner on how policies can be made that would produce more just cities. She suggests that it is possible to produce changes in planning practice if the value of equality, diversity and democracy become the standard of work if planner and policy-makers. Changing the approach of planning so that demands for justice and equality become central concerns, she argues the apparent lack thereof gender considerations will be changed and so, the scope for action enlarged.

Additionally, Harvey (2008) states, the concept of justice and the creation of a just city inevitably brings about the notion of “the right to the city”. The term and idea behind the right to the city first came from Henri Lefebvre in 1968. His complex vision about the city focused on how to restructure the power relationships which are connected to the production of urban spaces. Later, Harvey (2008) in his article “The right to the city”, described the notion far beyond an individual’s liberty to access urban amenities – it is a right to change themselves by changing the city. Thus, justice alone should not influence policy and planning practice, though should challenge the underlying social processes the shape policy-making. This, he suggests can only be done through collective struggle and conflict. Further to the right to the city, Harvey argues that the concept of a “perfect” just city is not as realistic or even desirable as it is made out to be, since urban projects should be understood as a product of social relations and therefore constantly will be changed and re-made because of social struggle (Sjöqvist, 2017). Instead of searching for utopian ideal of a just city, Harvey suggest individuals to challenge and remake cities according to their own desires and conceptions. In other words, while Faintein focuses on making prevailing discussions of planning more justice-orientated to develop outcome-based strategies, Harvey emphasizes the needs to challenge the foundations upon which these discussions take place.

INTERSECTIINAL FEMINSIM

Intersectional feminism is a concept use within feminist theory and refers to the integration of several inequalities into the feminist agenda. Inequalities can be based on social identities such as gender, ethnicity, class, sexuality, age and functional capacity, and overlapping identities can exacerbate a person’s marginalization. As such, the more identities that deviate from the norm, the more discrimination. This thesis focuses mainly on the intersections between gender, age and functional capability. Without the intersectional perspective, there is a risk that privileged women’s interest dominate the feminist agenda and other groups become invisible and marginalized.

Intersectional theory is rooted in Black feminist scholarship and first developed in the 1970s and 1980s by a group of African American feminist scholars and activists. They accused the Women’s Movement – also known as the Womens Liberation Movement – of neglecting black women and of misunderstanding oppression. Pathologies like racism and sexism are not separate systems – they are interconnected and overlap – and create a complex arrangement of advantages and burdens. For example, white women are penalized for their gender but privileged by their race, and black men suffer from their race but garner advantage from their gender. Black women – are in double jeopardy – they are disadvantaged by both race and gender. The focus of intersectional feminism within this thesis is important to highlight the needs of all women – by gender, age, sexuality, disabilities and religion – and not solely the needs of a single women. Thus, this thesis can be considered unbiased.

Gender equality and the intersectional perspective is essentially about justice and democracy. The overarching goal of gender equality is that everyone should be able to live their lives without being limited by stereotypes of what men and women should and shouldn’t do. Everyone should have the possibility to feel safe, have freedom of choice and be respectfully treated. This is not the situation today, so to achieve this, there is a need to break the structure which are limiting people lives and that place them in positions with different possibilities for action (Larsson & Jalakas, 2008). Many goals and regulations exist at global and local contexts that highlight the importance of gender equality. During the United Nations summit in September 2015, countries agreed on 17 Sustainable Development Goals that would end extreme poverty, inequality and climate change by the year 2030. Three of these goals are relevant to this thesis, including the following (UN, 2017). These three goals for sustainable development together grasp the overall aim of the thesis, namely to create inclusive and just cities from the perspective of women.

“Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”

This goal states gender equality is a fundamental human right, but also a necessary foundation for a peaceful, prosperous and sustainable world.

“Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries”

This goal includes the intersections that goal number 5 is missing, and focuses on inequalities such as income, gender, age, disability, sexual orientation, race that exists all over the world

“Goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”

The goal calls for nations to develop inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable cities to eliminate some of the greatest challenges such as poverty, climate change and healthcare.

URBAN FORM

This thesis seeks to answer how public spaces can hinder women’s participation in society. The built environment in itself is very is complex. When adding the interactions that take place between social environments/human and the urban form, the situation become even more difficult to grasp. Therefore, it is difficult to argue what “good” urban design is in general terms. Neither is a general discussion about good urban form is favourable in this study, as the focus on cities for women. Thus with women in mind, research will need to go beyond established practice about what “cities for everyone” means. As such, a number of spatial concepts relating to design elements, social behavior and spatial relationship will be described below.

The design and location of settings have a big impact on what way and how long people stay in cities. Based on feminist scholarship, strategic gender planning guidelines were developed to effectively assist planning for adequate urban environments (Huning, 2013). Guidelines to date include the below.

- The proximity of building in relation to public and private traffic infrastructure

- Size and layout of land uses

- Prominent of access points and entryways

- Adequate space between buildings (to ensure privacy and provide sunshine, natural light and ventilation)

- Orientation of buildings towards outdoor spaces

- Preferred use of construction methods and designs that allow quiet indoor and outdoor areas

- Avoiding “blind facades” (safety, design)

(für Stadtentwicklung, 2011)

Within cities, people often choose different locations due to personal taste and other circumstance such as price, density, transport etc. People therefore have different appropriation ladders, in other words, a personal hierarchy of places in which they choose to position themselves. Places with a high spatial variation that offer different forms of infrastructure and services, personal control and publicness are desirable to attract more visitors. This gives people the possibility to find their own desirable location to territorialize (Magnusson, 2016).

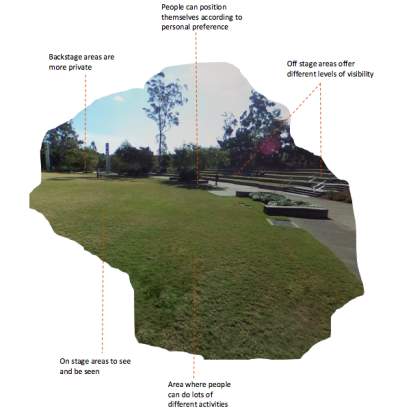

Other forms of urban form and its influence on social behaviour relate to different levels of publicness in cities. The concepts of on stage, off stage and backstage derives from sociology and developed by Erving Goffman (Oommen, 1990). According to Goffman, people in a city can be seen as actors on a stage. The metaphor is used to describe different modes of behaviour and human interaction. On stage behaviour can be described as the focus spot, where an individual has a lot of eyes on them. For example, the audience therefore can be pedestrians on a street or other consumers in a shops. Off stage behaviours refers to places that are situated behind or in close connection to focus spots (on stage) while backstage are places that are behind and more hidden. If the aim is to attract different groups of people, then that is the ability to create places where one can choose on stage, off stage and backstage places. The importance of Goffman`s research in relation to urban planning includes two categories of spaces – spaces for retreat and spaces for interaction. It is important that women have the possibility to move between these different levels of visibility.

Lastly, the ability to move between cities depending on the configuration is a concept vital to equal cities. Configuration and geometry in cities has many important health and social benefits as it encourages physical activity and independence (Ferenchak and Marshall, 2017). Spatial configurations can be best understood by theory of Space Syntax. Space Syntax approach builds upon a number of techniques for representation, quantification and interpretation of spatial configuration in buildings and settlements. Configurations must be dynamic, consistent and robust. This concept of configuration together with social behaviours and design are used in the thesis as tools to evaluate Springfield Lakes.

data methods

DATA COLLECTION

The research project will be approached using qualitative research methods. This type of methodology is concerned with the shape and process of societal structures, or of individual experiences of places or events. To understand how people interact with the world around them, it is essential to consider the social context and how it influences relationships between individuals and the world. Semi-structured, closed-ended questionnaire surveys were conducted for data collection. A qualitative approach using questionnaires have shown to provide a richer and more descriptive explanation of an individual’s perception of urban environment. This type of experimental understanding is what the study aims to achieve to better inform planning practices.

The questionnaire consists of namely placed-based questions and personal experience. Respondents were asked to evaluate the surrounding landscape and design of Springfield Lakes based on experiences in a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represents strongly disagree and 5 represents strongly agree. Some questions also included a rating scale used to measure the direction and intensity of attitudes. In the questions, various variables of urban form, equal equalities and feminism in the literature review was presented as a self-explanatory statement for the respondents to rate their personal importance. Some example questions include the following: do you feel unsafe in public spaces?; how often do you experience hazardous feelings?; and are you concerned about gender issues?

The survey was administered via email. Targeted respondents were local residents (men and women), undergraduate and postgraduate planning students, and development agencies. Data collection started with the known stakeholders and respondents were invited to also distribute the survey link to their respective networks. Data collection continued for approximately a two-month period of time. A total of 30 surveys were conducted.

DATA ANALYSIS

The 30 survey respondents personal profile are show in Table 1. The data was analysed with Excel to evaluate the barriers to women in city design, if any, using descriptive statistics such as mean and ranking to show their relative importance. This data was then used to examine whether personal attributes (i.e. gender, age, or interest) would have an effect on an individual’s experience to city design and development. These results will be discussed in the following section.

| No. of Respondents (%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 7 (23.3%) |

| Female | 23 (76.6%) | |

| Age | 18 – 25 | 20 (66.6%) |

| 26 – 30 | 3 (10%) | |

| 31 – 40 | 0 (0%) | |

| Above 40 | 7 (23.3%) | |

| Period in Springfield Lakes | < 1 Year | 3 (10%) |

| 1 – 5 Years | 13 (43.3%) | |

| 5+ Years | 16 (53.3%) | |

| Interest in Gender Issues | Not at all | 0 (0%) |

| Neither interested or uninterested | 23 (76.7%) | |

| Very much | 7 (23.3%) |

Table 1 Survey Respondents Personal Profile

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

The following section contains the results of respondent’s perceptions and reflections of urban planning and development in relation to Springfield Lakes. To understand the needs of women, this thesis has worked with local residents and also looked at current planning practice. As abovementioned, the survey had reached 30 people; the majority of participants were women, with 23 females and 7 males. Of participants, more than half were aged below 25 with the remainder aged above 40 years old. Further, 23 percent of participants were “very interested” in gender issues, while 76 percent were “neither interested or uninterested”. No participants said they were completely uninterested in gender issues.

On the face of it, the spread of information received from empirical data gathering seems to run directly counter to the above literature. The results suggest that Springfield Lakes has been somewhat successful in “gender inclusive” planning. There was a general consensus on Springfield Lakes being perceived as friendly, welcoming, equal and pleasant, confirmed by majority of the participant’s responses. The results of this study are surprising, given the research findings discussed in previous sections of this thesis. Research shows that conventional land use planning constrains the mobility and limits opportunities for women, reinforces outdated family structures as the norm and provides inadequate support systems. However, it can be argued that this is not the case for Springfield Lakes.

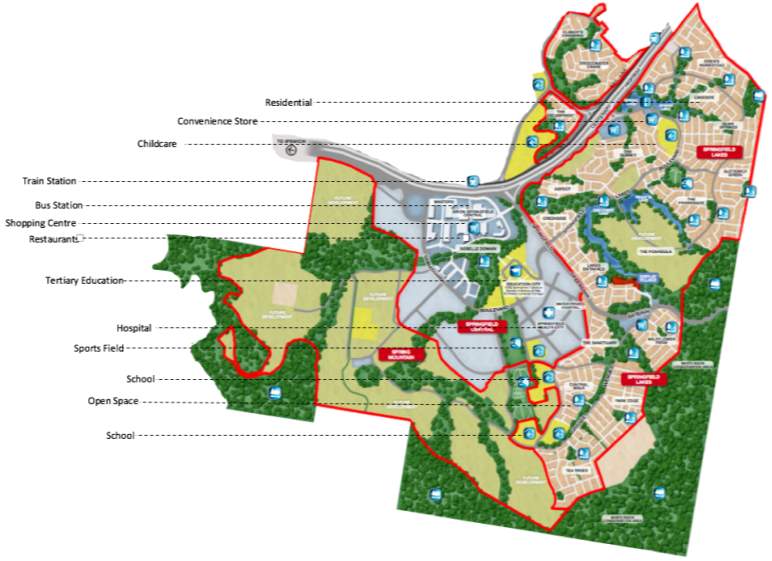

The neighbourhood surrounding Springfield Lakes has high population density. The 2917 Estimate Residents Population for Springfield Lakes is 17,450, with a population density of 9.19 persons per hectare (ABS, 2017). Springfield Lakes is considered a satellite city, whereby it is essentially a smaller metropolitan area which is located somewhat near to, but are independent of, large metropolitan areas (Hayes, 2017). Survey results indicate that offices, shops, childcare and residential zones are close to each other which does not burden access such facilities. Likewise, spatially integrated landscapes and transit plans in Springfield Lakes support women’s mobility needs and include women in society. The results are also supported by current planning practice as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Commerce and Business around Springfield Lakes

To create spaces for women, configuration is of critical and vital importance. It is evident from survey feedback that majority of residents felt safe to walk or ride their bike during day and, to a lesser extent, at night time. Participants also suggested they feel comfortable going out completely alone, however very dependent on personal attitudes. Springfield Lakes has high mobility options and transport choice for women; which in turn uplifts the status of women in society and enhances their access to economic opportunities. There are two train stations in Springfield Lakes – Springfield Central Station and Springfield Station – located central to the area. The train and bus services are very frequent arriving every 30 minutes, safe and affordable for women. Springfield Lakes is also categorized to be of medium socioeconomic status. Research often shows low or medium socioeconomic status associated with higher density, meaning facilities and homes closing located together. From an intersectional feminist perspective, high density living can be beneficial as it promotes inclusiveness and provide equitable opportunities for all women. The densest cities can be the most efficient, lively and sustainable (Rodes, 2015). In contrast to above, women in higher socioeconomic suburbs generally experience a higher likelihood of inequality as places and infrastructure is spread over a wider area.

Additionally, data results also show safety is of high concern for all participants. Women prefer to exclude themselves from places which are poorly lit and uninviting due to safety concerns. For example, the below figure compares a major neighborhood street in Springfield Lakes from day to night. During the day, the street appears aesthetically attractive and user-friendly. Although, during the night the street is poorly lit, with only two number of street lights. Hence poses a danger to residents, more so women. In order to encourage women, cities need to design streets with more lights to increase visibility and safety. As a result, more street life will be attracted without one dominating the other.

Figure 2 Springfield Lakes Nieghbourhood Street

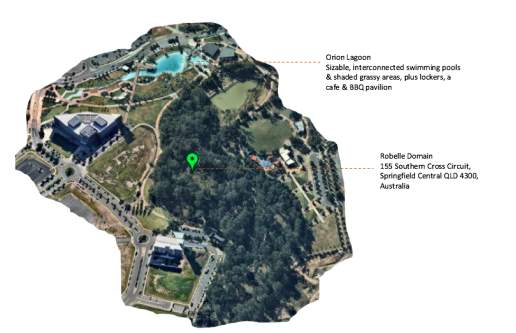

Furthermore, Springfield Lakes provides possibilities for a mix of different zones, from on stage to backstage places where the level of privacy shifts. Women have the need to see other people but also to be seen when they want to. For example, Robelle Domain Parklands located within Springfield Lakes as shown in Figure 3 below, is an interactive space that meets several needs and responds to different desirable behaviours. The parkland is flexible and allows women to have the choice of privacy. Firstly, the parklands offer on stage areas to see and be seen. The parklands allow for mothers to bring their children here to explore and play whilst mothers find time to do their own work. On stage behaviour is favorable in this space as it encourages interaction and mothers feel safe to let their children play while they are doing everyday activities. Secondly, the parkland also offers off stage areas at different levels of privacy. This is through use to location of furniture and shelter. Thirdly, the parklands offer backstage areas which are more private. Planting and landscaping features somewhat provide secluded space which women can enjoy the public spaces without the feeling of everyone watching them. Offering both on stage, off stage and backstage places is a good tool to ensure women’s comfort and safety.

Figure 3 Key Aspects of Design Relating to Robelle Domain

To sum up, women’s needs are beginning to attract planners interest, particularly in the case of Springfield Lakes. A consistent theme become common in the literature and surveys: planning for women is about planning for everyone. It can be said that considering the impact of planning actions on women means that the needs of most people are also considered. Asking “would a woman feel comfortable here?” and getting a positive response likely indicates most people will feel comfortable using the space. As such, women and can be used as a guide for planning priorities.

LIMITATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

This thesis set out to explore women’s right to the city and the importance of gender equality in urban planning. As the thesis unfolded it became apparent how important it is to prioritize women in order to create equal cities. The focus of the thesis was from an intersectional feminism perspective, a perspective that is even more lacking in planning. This perspective recognises how marginalized groups are often interconnected and cannot be examined separately from one another. This thesis focuses mainly on the intersections between gender, age, sexuality, disabilities and religion.

Through questionnaire surveys with different actors and background analysis of current literature, this thesis has found Springfield Lakes balances the needs of men and women equality. Empirical data gathering has shown to run counter to existing literature and responds to the objectives set out in the thesis aim. Firstly, the results prove successful in achieving positive outcomes within the context of urban planning from a feminism perspective. Secondly, more than two-thirds of survey participants perceive Springfield Lakes as “gender-inclusive”. Cities can definitely be designed in a way that can stimulate women’s participation in society, and thereby enhance their possibilities to be represented.

Participants feel comfortable to do their own thing and are not constrained by unequal opportunities.

Nevertheless, issues of women safety still remain. Improved planning, for example, elimination of dark streets and narrow pathways, and ensuring eyes of the street can help make cities safer for women.

This thesis contributes to revealing the current situation of gender-inclusive in urban planning and development in an Australian context.

http://publications.lib.chalmers.se/records/fulltext/255094/255094.pdf

http://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/SSC32655

Hayes, M. (2017). What Is A Satellite Town?. Retrieved from https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-is-a-satellite-town.html

Rodes, P. (2015). How connected is your city? Urban transport trends around the world. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/nov/26/connected-city-urban-transport-trends-world

Harvey, D. (2008). The right to the city.

Oommen, T. K. (1990). Erving Goffman and the study of everyday protest. Beyond Goffman. Studies in Communication, Institution, and Social Interaction, Berlin et al, 389-407.

Ferenchak, N., & Marshall, W. (2017). Are our Cities Making our Roads Unsafe? The Impact of Land Use Configurations on Child Pedestrian Injuries (poster). Journal of Transport & Health, 7, S15-S16.

https://www.breitbart.com/europe/2017/04/05/swedish-no-go-zone-adopt-feminist-urban-planning/

https://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/entry/cities-designed-for-women_us_571a0cdfe4b0d0042da8d264

Olsson, L. (2008). The self-organized city: appropriation of public spaces in Rinkeby. Department of Architecture and Built Environment, LTH, Lund University.

Purcell, M. (2002). Excavating Lefebvre: The right to the city and its urban politics of the inhabitant. GeoJournal, 58(2-3), 99-108.

United Nations. (2017). Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved from: https://dfat.gov.au/aid/topics/development-issues/2030-agenda/Documents/sdg-voluntary-national-review.pdf

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2017. Springfield Lakes : Region Data Summary. Retrieved from http://stat.abs.gov.au/itt/r.jsp?RegionSummary®ion=310041304&dataset=ABS_REGIONAL_ASGS&geoconcept=REGION&measure=MEASURE&datasetASGS=ABS_REGIONAL_ASGS&datasetLGA=ABS_NRP9_LGA®ionLGA=REGION®ionASGS=REGION

Goal number 5 is to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls (United Nations, 2017). UN states that gender equality is a fundamental human right, but also a necessary foundation for a peaceful, prosperous and sustainable world. Goal number 10 aims at reduced inequalities within and among countries. This goal includes the intersections that goal number 5 is missing, and focuses on inequalities such as income, gender, age, disability, sexual orientation, race that exists all over the world. Goal number 11 strived for making cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. These three goals for sustainable development together grasp the overall aim of the thesis, namely to create inclusive and just cities from the perspective of women.

Habitat, U. N. (2013). Streets as public spaces and drivers of urban prosperity. Nairobi: UN Habitat.

Fainstein, S. S. (2009). Planning and the just city. In Searching for the just city (pp. 39-59). Routledge.

Elander, I., & Åquist, A. (2001). The contradictory city – everyday life and urban regimes.

Sjöqvist, E. (2017). Struggling for gender equality in Husby: Feminist insights for a transformative urban planning.

Magnusson, J. (2016). Clusering Architectures – e role of materialities for emerging collectives in the public domain. Sweden.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Equality"

Equality regards individuals having equal rights and status including access to the same goods and services giving them the same opportunities in life regardless of their heritage or beliefs.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: