Veterans’ Health Administration: Problems and Solutions

Info: 9762 words (39 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Tagged: Health and Social Care

Abstract

This paper will review the literature on the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), including the current methods of improving safety, efficiency, access, satisfaction, and responsiveness. After reviewing the literature, this paper will also present recommendations based on the current programs and strategies the VHA has made in the past to improve its organization. Researchers have suggested that the decline of the VHA is attributed to the lack of management at Veterans Administration (VA) facilities, inefficient VA programs offered to veterans, and the overall organizational culture. Improvements within the VHA will require changes in the organizations culture and innovations through each current VA program/benefits that are available for veterans. Although the VHA has produced some changes over the years; scandals and patterns of documented-problems has overshadowed any success that has come from those changes. In summary, researchers’ proposal of changes towards the VHA is widespread and offer strategies that could improve how the VHA functions in the future.

Veterans’ Health Administration: Problems and Solutions

Introduction

The Veterans’ Healthcare Administration (VHA) in the past has received accusations of mismanagement, falsifying records, and failing to take actions which would have prevented patient deaths. The VHA’s inability to progress and improve veterans’ health care processes has a well-documented problems pattern of behavior. Some efforts have been made to help veterans who seek to receive better care and obtain needed benefits. For example, the Veterans’ Choice Program (VCP), this allows eligible veterans to receive care from non-VA facilities. The implications with this program is the longevity though,” Authorized under Section 101 of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (VACAA), the veterans’ choice program (VCP) is a new, temporary program (the VCP is set to expire in August 2017 or whenever funds in the Veterans Choice Fund are exhausted) that enables eligible veterans to receive medical care in the community’ (Panangala, 2017, p. 2). Despite the mounting pressures from veterans’ organizations and other entities, major changes to the VHA have not been implemented. Furthermore, this research paper argues that the VHA is not providing adequate health care and many of the veterans across the United States are not receiving care at all. In summary, by identifying the main issues surrounding the VHA and implementing strategies in restructuring the organization, the goal of this capstone is to review the different strategies to determine how they have helped and hurt efforts to improve the VHA throughout history.

VHA History

As the U.S. entered World War I in 1917, Congress established a new system of Veterans benefits, including programs for disability compensation, insurance for service personnel and Veterans, and vocational rehabilitation for the disabled (U.S. Department of Veterans Affair, 2017, p. 1). This first-ever government institution was established to provide care to veterans, specifically those who were discharged honorably. Moreover, the care being provided for veterans became overshadowed by other issues (civil rights, economic, wars) in the United States. One of the biggest issues that developed from the VHA was the lack of data and measures of performance, which could be used to research productivity. During the 1970s and 1980s the VHA was widely viewed as an inefficient safety-net provider at best (Hayward, 2017, p. 11). The inefficiency within the VHA became more noticeable as certain health issues, such as post as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was more prudent within the veteran community. Transformation within the VHA did not occur until the 90s, when focus on clinical quality and performance increased. Its turnaround in the 1990s under VHA Under-secretary Ken Kizer was one of the most dramatic in health-care history (Hayward, 2017, p. 11). During this time more efforts were made to figure out issues such as budgeting, wait time, management, and overall performance measurements within the VHA. Not until the 1990s, programs and strategies to improve the VHA were implemented in a major way. Launched in 1998 as a key element of VHA’s strategy to systematically examine and enhance its quality of care, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) is a large-scale, multidisciplinary quality improvement initiative designed to ensure excellence in all areas where the VHA provides health care services (McQueen, 2004, p. 340). The progress and sustained commitment to deliver high quality health-care to all veterans was now a major part of the implementation of future VA programs.

Literature Review

The ethical discussion behind the VHA is not only framed through the context of how the organization functions, but also its history. As the VA Health-care system works to address issues of access to and timeliness of health care for our nation’s veterans, it must ensure that these dimensions of quality are equitably achieved for all veterans (Hayward, 2017, p. 22). Certain methods and technological advancements have helped the VHA become effective in reducing disparities and better quality services as a whole. VA health care delivery is supported by centralized administration; a high value, evidence-based pharmacy benefits plan; and a national health information technology platform that enables innovative and interactive use of the electronic health record and clinical and administrative data for intervention, evaluation, and tracking patient care (Hayward, 2017, p. 18). In the spectrum of care in the United States, the way the VHA compares to other health-care programs, remains to be unclear. The debate on whether or not the overall services provided by the VHA are effective will exist long after any transformations that are made within the VHA. One of the biggest differences between the VHA and other health-care providers is that the VHA is not delivered by private providers in private facilities. In contrast, the VA health care system could be categorized as a veteran-specific national health care system, in the sense that the federal government owns a majority of its health care delivery sites, employs the health care providers, and directly provides most of health care services to veterans (Panangala, 2016, p. 3).

Eligibility Requirements

The VHA does not offer free health-care to all veterans; there are requirements they have to meet to receive certain services. In fact, numerous of claims have been made by veterans about the certain “promises” that military personnel make to veterans regarding free medical benefits for life. At a minimum, the veteran must have served (1) in the military, naval, or air service; (2) for the required minimum period of duty;24 and (3) received a discharge or release that is under other than honorable (e.g., general, honorable, under honorable conditions) (Panangala, 2016, p. 4). Veterans under a certain “A” or “core” category will receive free health care based on the more specific criteria they have to meet for enrollment. For the VA to provide all needed hospital care and medical services, the veteran must have service-connected disabilities;16 former prisoners of war; veterans exposed to toxic substances and environmental hazards such as Agent Orange; veterans whose attributable income and net worth are not greater than an established “means test”; and veterans of World War I (Panangala, 2016, p. 3). Furthermore, these various requirements that are needed to be made by veterans are one of many obstacles veterans have to go through to receive health-care. The VHA is a mechanism for health relief by many insured, pensioned, and middle-class persons as well- patients not often perceived as requiring a safety net (Simpson, 2006, p. 22). The VHA is also difficult to deal with when it comes to veteran families because of the strict criteria they have to meet for benefits as well.

Veteran Families

For military families with children, partners may tackle a host of new challenges while service members are deployed, including loss of income and child care, and changes in health insurance (Makin-Byrd, McCutcheon, Roberts, Barnett, &Michelle, 2011, p. 48). When it comes to veteran families being eligible for VA health-care, there currently is not any program that gives families them that option. However, veteran families that meet certain requirements as dependents and survivors may receive some type of reimbursement from the VA for medical expenses. On May 5, 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law the Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010, which expanded the CHAMPVA program to include the primary family caregiver of an eligible veteran who has no other form of health insurance, including Medicare and Medicaid (Panangala, 2016, pp. 3-4). This program is primarily a fee-for-service program that reimburses most medical care to families, which will be provided by facilities outside of the VA. Major depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and alcohol misuse disorders are all common psychological problems experienced by Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF/OIF) service members (Makin-Byrd, McCutcheon, Roberts, Barnett, &Michelle, 2011, p. 49). Ultimately, this program provides counseling, training, and mental health services for the primary family caregivers that meet the criteria.

Combat Veterans

To clarify VHA initiatives and services for community-based clinicians, veterans, and their families, we will next review the empirically-based family intervene interventions currently available within the Veterans Health Administration (Makin-Byrd, McCutcheon, Roberts, Barnett, &Michelle, 2011, p. 49). Next, enrollment for returning combat veterans is another component of the VHA that requires certain criteria’s that need to be made by combat veterans. Veterans returning from a combat theater of operations are eligible to enroll in VA health care for five years from the date of their most recent discharge or release without having to demonstrate a service-connected disability or satisfy an income requirement (Panangala, 2016, p. 5). The VHA has a large population of veterans that were injured in the OEF/OIF wars, which now require services that focuses on the veteran’s disabilities. The survivability of severe injuries from OEF/OIF is unprecedented, resulting in rehabilitation needs and long-term outcomes not experienced in previous military conflicts (Copeland, Bingham, Schmacker, & Lawrence, 2011, p. 227). One of the biggest factors in the OEF/OIF wars where the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), which had become more regularly used in battle. Service members are not the only ones threatened by these conventional high explosive devices, but also the civilian population. With increasing use of explosive weapons, blast related brain injury, in the absence of direct skull trauma or penetration, was noted to occur with increasing frequency (Depalma, & Hoffman, 2016, p. 2). Finally, the largest challenges existing within the VHA is credited to numerous of issues, which include recent scandals, chronic illnesses, and mismanagement.

Exploring the issues

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has been plagued by one of the largest scandals in its history since receiving cabinet level status: scandal regarding veterans experiencing excessive wait times for needed health care services (Campbell, 2015, p. 1). It is imperative to examine the VHA’s current capabilities in producing effective methods in addressing these issues and overcoming the obstacles that come with implementing policies. One of the most critical issues the VHA is presently facing is the increase numbers in wait-times and backlogs for services, which is attributed to the growing number of disabled veterans coming back from OIF/OEF wars. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is another issue that VHA facilities face from both OIF and OEF wars. Rehabilitation counselors are now facing a new, ever-larger population with a disability, one that has been termed a “signature wound” of the returning Operation Iraq Freedom (OIF) and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) veterans (Burke, Degeneffe, & Olney, 2009, p. 52). The various psychological and medical needs these veterans are returning home with will require a focus profession such as a rehabilitation counselor to be manage and serve those needs. Implementing a program that best equips these counselors to provide effective case management services for the veteran’s specific needs is one way to improve overall productivity. Furthermore, the mass number of veterans returning with chronic and mental illnesses will only increase, which makes it even more important to implement programs specifically for veterans returning from war.

Chronic and Mental Illnesses

Since the Gulf War ended in 1991, there has been a growing number of reports of chronic illnesses among the nearly 700,000 United States troops who service in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Iraq (United States, 1997, p. 6). The frequent occurrence in mental illnesses such as PTSD in OIF/OEF veterans is very high and the costs to each veteran that has PTSD are excessive. From suicides to violent crimes, the PTSD epidemic has risen to a degree in which it pressures the VHA to determine methods of reducing suicides and crime. In turn, more attention was made toward understanding and recognizing signs of symptoms of those who endured any trauma during their tour. Depending upon blast exposure intensity, immediate symptoms and signs of concussion ensue, followed by a variable intermediate period of evolving neuropathological effects (Depalma, & Hoffman, 2016, p. 2). Mental illnesses that resulted from IED blasts have several consequences towards the veterans’ mental stability, which has been focused on more over the recent years. More broadly, Federal agencies, including the VA, the DOD, NIH (Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke), the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research focus upon diagnosis and understanding of short and long-term TBI effects, evaluation of existing treatments, and development of novel approaches for rehabilitation and community reintegration (Depalma, & Hoffman, 2016, p. 2). Through determining effective methods of prevention, screening, and low-cost treatments, the VHA can provide better overall care for returning veterans across the United States. Lastly, now that chronic and mental illnesses have been given more attention, it gives the veterans that have those symptoms the opportunity to take advantage of VHA programs that focus on those disabilities.

Recent Findings & Scandals

According to an article made by The Republic (2015), the following statement was made in 2012, “Dr. Katherine Mitchell, a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) emergency-room physician, warns Sharon Helman, incoming director of the Phoenix VA Health Care System, that the Phoenix ER is overwhelmed and dangerous” (p. 2). This statement made by a VA emergency-room physician only verifies the recent scandals that have resulted from the lack of timely made services. The emergency-room is not the only department within the VHA that has its flaws, but also the claims department. As of August 2014, the average wait time for a claim response was 160 days and the average wait time to appeal a claim was 1,301 days (Anderson 2014, p. 26). With the new generation of disabled veterans being pushed to the VA system, the high demand of services has reached an all-time high for the VHA.

Cooper (2004) claim findings:

In 2003 the VA suspended health care benefits to 200,000 veterans just prior to the launch of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Approximately 27,000 veterans filed for benefits in 2004, but nearly 9,000 were not processed within the calendar year due to a backlog of 334,000 claims (p. 973).

The reality is that the VA is one of the oldest, largest and most complex health care systems in the world, especially due to its high demand in services. More specifically, it is our country’s leading centrally managed health care system and the principal unified provider of health care education for health care staff and physician residents (Kizer et al. 2000, p. 15). The VHA is faced with continually expanding responsibilities and demands, which puts more pressure on management to respond to the growth and change in a timely way. Only through efficient management and structure will help improve care in a timely matter for patients. The demand to meet the needs of service members and veterans continues to grow: the number of outpatient visits to VA health care facilities have grown by 26% over the last five years, and the VA system experienced an overall increase from 83.6 million to 94.6 million outpatient visits/fiscal year from 2012 to 2014 (Shear & Oppel, 2014, p. 2).

Mismanagement

In 2010, the Institute of Medicine reported a shortage of mental health services for veterans and the VA technology chief called the claims management system “broken beyond repair” (Billitteri, 2010, pp. 371-372). Effective leadership is about maximizing productivity from employees and getting the most out of the employees who work within the organization. The VHA is such a complex organization that has consistently failed to show any signs of productivity and efficiency in its leadership positions. Leadership positions within the organization have the power to recreate a culture that empowers employees to understand their role in the system. For example, successful organizations that create certain mottos (vision, values, and characteristics) for their employees to mirror, help keep employees motivated and productive in their services. Wait-times and misconduct within any organization usually points towards management, which has been frequently questionable within the VHA. Shear & Oppel (2014) elaborate on recent mismanagement accusations in 2010 with the following, “The scandal came to a head when reports confirmed accusations of widespread misconduct and the long-term systematic cover-up of these appalling wait-times throughout the VA’s massive hospital system, which led to the resignation of VA Secretary Eric Shinseki in May 2014” (p. 35). The challenges that the VHA is currently facing with management is integrity and properly implementing programs to improve services for veterans.

Factors Affecting the VHA

The VHA has had its ups and down, in particularly at the Phoenix Arizona location where numerous scandals and constant change of leadership has occurred over the years. From bad overall services veterans’ experience to growing number of wait-times, the VHA system has been overwhelmed with providing care for veterans. One important factor to consider is the number of veterans the VHA must care for daily. Not only do they have to care for veterans from the past couple decades, but also those dating back to WWI. For example, “The Veterans Administration also had to serve an additional 245,437 soldiers who were wounded during the Korean War and the Vietnam War between 1953 and 1979, all of whom received fewer VA benefits compared to WWII veterans (Chambers & Clemmitt, 2007, p. 707). The demand to serve for this large population will only increase in the future, which makes it important for the VHA to restore trust within the veteran community. Through meeting the publics’ demands and understanding the current issues within the veteran community; the VHA could satisfy veterans’ needs. Also through news media outlets, social media, and community events, the VHA can gain the trust of veterans throughout the nation. The focus with this approach is to mitigate the impact of uncontrollable events and show the country how much effort this organization is putting to fix its image. Improving overall-care is the responsibility of VHA leadership that have the power to change its organizations culture to meet the needs of veterans.

Media Influences

Not until recently has the VHA been rightly or wrongly portrayed by media/entertainment outlets, even though there have been notable examples of failures within the organization. Although most of the news made on the VHA is negative, there also has been improvements within the organization and how its system functions. The VHA has established itself as a more of an innovative healthcare-system, by including advance electronic medical records, with comprehensive clinical and informative objectives. The media and political figures have the responsibility to keep the VHA accountable for their actions and missteps. In April 2014, the Chair of the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, Jeff Miller (D-FL), held a hearing to examine evidence that the Phoenix VA kept one set of records to demonstrate timely delivery of care and another set that illustrated significant deferrals (Gold 2014, p. 17). More pressure needs to be made by politicians to unsure that the organization is functioning professionally as well as staying accountable. Gold (2014) goes on to state the following on the media’s power in keeping the VHA accountable, “Later that month CNN aired “A Fatal Wait,” which revealed internal emails showing that top-level management condoned the act of shredding veteran appointment requests to distort wait-times” (p. 17). The media’s ability to attract national attention is a vital factor in improving the VHA because it gets outside entities (politicians & public) involved at any moment. As the VHA receives more and more attention from the media, it also gives the organization the opportunity to develop strategy that receives positive feedback from the public.

Budget

The amount of responsibility the VHA has in treating both combat-related injuries and veterans with service-related disabilities are considerably expensive. It has “grown from the Veterans Administration with an operating budget of $786 million serving 4.6 million veterans in 1930 to the Department of Veterans Affairs with a budget of $63.5 billion serving nearly 25 million veterans” (U.S. Department of Veterans Affair, 2017, p. 1). VHA clinics across the United States have struggled to keep up with the large number of veterans that are diagnosed with serious combat-related injuries. Amara & Hendricks (2014) findings on traumatic brain injuries (TBIs):

Since 2000, there have been nearly 300,000 traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) diagnosed in U.S. service members around the world. Approximately 80% of these TBIs have been mild11 in severity. In theater, mild TBI can sometimes go undiagnosed, or have a delayed diagnosis, for multiple reasons, including service member reluctance to report medical injuries or mild TBI being overlooked for more apparent injuries that require immediate attention. Blast-related TBIs occur in addition to concussions by more traditional means, such as motor vehicle accidents and other blunt trauma, making TBI one of the defining injuries of OEF/OIF. Studies from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), 17 the Rand Corporation,18 and the Army19 20 have estimated that 7% to 23% of those who served in OEF/OIF have either probable or clinician-confirmed TBI (p. 965).

These TBI findings should be considered for VHA budget because of the amount of expenses the VHA need to put aside for TBI related injuries and treatment plans. Overall the VHA must implement a budget plan that guides its organization in a direction that best serves veterans and the VHA financially. The issues that surround budgeting should not be used as an excuse for the VHA because it does not relate to the overall productivity of VA employees. The VHA has an ethical obligation to serving veterans to the best of its ability, which begins with recognizing current issues they are facing such as wait-time and back-logs.

Wait time

Although there is no policy requiring the VHA to measure the total time veterans wait to be seen, officials from one Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) has begun to measure wait-times, as it may provide valuable insights into newly enrolled veterans’ experiences in trying to obtain care from the VHA (Draper, 2016, p. 21). Entities such as the VISN are vital to collecting data and oversighting VHA facilities across the nation. Even though it does not account for all veterans, it still gives the VHA a better viewpoint on how effective its services are for veterans. Since February 2015, officials from this Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) have instructed each of the medical centers they oversee to audit a sample of 30 primary care, specialty care, and mental health appointments for new patients, including newly enrolled veterans, for a total of 90 appointments each month (Draper, 2016, p. 26). The VISN’s audit also records dates of initial requests on schedule appointments, when the dates where created, and the actual date they were seen. These measurements are extremely important for the VHA to develop a strategy to help provide services in a timely manner. While profit serves as the goal of a business, the corresponding measure of government’s achievement is less clear (Johnson, 2004, p. 305). Ultimately, the VHA is a government entity that does not make any profit from the veterans they serve, which makes it even more important to keep this organization accountable.

Internal Problems

Governmental created systems such as the VHA holds a different level of responsibility for those it serves versus private agencies who usually focus more on profit. One of the most significant risks and problems that the VHA faces other than the lives of numerous of veterans are hiring good staff (doctors, nurses, receptionists, etc.).VA employees hold a great amount of responsibility in serving the veteran community with high morals and values that focus on the veterans’ needs. While the veteran community continues to grow every year, the amount of pressure to balance the level of employee to veteran ratio becomes more evident. Internal problems within the VHA stems closely to the organization’s culture and goals set by leadership positions within the VHA. Developing a vision for an organization such as the VHA falls in the hands of management, who have the responsibility in keeping every employee on the same page. Also, consistently training and empowering employees are another approach leadership positions within the VHA can implement. Furthermore, the leadership role within the VHA is vital to the overall success of the organization, relationships with the veteran community, and improving overall care. The most natural of human relationships is that between leader and followers (Starling, 2008, p. 311). Leaders of organizations have the power to recreate a culture that promotes and enforces regulations that best suits the patron’s well-being. In summary, monitoring safety and enforcing regulations for the veteran’s well-being can be much easier by restructuring an organization’s culture.

Organizational Structure

Once disparaged as a bureaucracy providing mediocre care, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) reinvented itself during the past decade through a policy shift mandating structural and organizational change, rationalization of resource allocation, explicit measurement and accountability for quality and value, and development of an information infrastructure supporting the needs of patients, clinicians, and administrators (Perlin, Kolodner, & Roswell, 2004, p. 1). Reinventing the VHA’s organizations structure is not only necessary for bureaucratic purposes, but also for getting the most out of every employee that work at the facilities. The decentralization and dispersing responsibilities throughout the VA has contributed to the struggles the VHA experiences. To help oversee veterans’ access to primary care, officials at VHA’s central office, medical centers, and VISNs rely on measuring, monitoring, and evaluating the amount of time it takes veterans to be seen by a provider (Draper, 2016, p. 31).The VISNs approach to monitoring veterans’ overall care is helpful, but would it be more reliable if other entities also measured these evaluations. Officials indicated that it is time-consuming to perform these audits, and it would be helpful if VHA had a centralized system which would enable them to electronically compile the data (Draper, 2016, p.21). Furthermore improving the VHA organizational structure begins with developing formal methods of measuring its system and its overall services.

Responsibilities

Monitoring wait-times and accounting for enrolled veterans are currently not responsibilities of the VHA. A large amount of the VHA responsibilities are on veterans with combat related disabilities and veterans with service-connected disabilities. VHA employees help guide veterans through lengthy claims process to receive benefits and serve as a primary care for veterans. Most of the issues that surround the VHA are accountability, which points to the duties and responsibilities they are obligated to do. Accountability includes having a certain level of ethical behavior, which Kettle, (2010) states ethical behavior with the following, “adherence to moral standards and avoidance of even the appearance of unethical actions” (p.7). Developing an ethical standard for the VHA is important to ensure that services are given at a high level and duties are met. Lastly, demanding productivity through creating quotas or goals for employees to meet are strategies that could improve overall care.

Overall Care

Authors Kizer and Jha (2014) state the following on the progression in efficiency that the VA system has shown, “The performance-measurement program — a management tool for improving quality and increasing accountability that was introduced in the reforms of the late 1990s — has become bloated and unfocused”( p.295). Previous attempts in improving the VHA has failed in the past, which is one reason the VHA, should implement concepts such as resolving conflict, overcoming resistance to change, and ethical behavior. To reach this goal, management will have to engage more with employees and mold them to work efficiently through any situation. If human resource management is about the development of policies for effective utilization of human resources in organizations, it should be doubly concerned with employee engagement, which is key performance-engaged workers are more committed, conscientious, and concerned with achieving outcomes, and they have less turnover, too (Berman, Bowman, West, and Montgomery, 2016, p. 215). Employees’ morale affects how efficient and accountable an organization is, which ultimately affects the community in the long run. Employee engagement will be important in the future to help the VHA receive internal feedback and recommendations on improving overall care.

VHA Programs/Benefits Offered

The Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA) mission, with 151 hospitals and over 900 outpatient clinics, is to “honor America’s Veterans by providing exceptional health care that improves their health and wellbeing (Wittrock, Ono, Stewart, Reisinger, & Charlton, 2015, p. 35). Providing veterans with the best possible care is heightened by the implementation of programs and systems that are made in place to improve services. Since the 1960s, large integrated delivery systems such as the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and Kaiser Permanente have engaged in cutting-edge health services research designed to directly apply to and improve care (Wu, Kinsinger, Jackson, 2014, p. 825). A large amount of the benefits is offered to veterans based on the service connected disabilities they obtained while their time in the service. Other milestones that have been made over the past years are the collaboration efforts between non-VA facilities and the VHA. For example, implementation of programs that allows veterans the opportunity to receive care as well as counseling outside of the VHA. Such collaborations can be especially valuable, as health systems implement new clinical programs to ensure that they will be able to answer the critical questions about how effective the programs are, how to maximize safety and value, and how to make sure they are implemented reliably and efficiently (Wu, Kinsinger, Jackson, 2014, p. 825).

Veterans’ choice program

The veterans’ choice program has shown signs of availability, good services, and overall flexibility for veterans who may live far from main VA facilities. Under the program, for example, certain veterans can receive care in the community, including primary care, if the next available medical appointment with a VA provider is more than 30 days from their preferred date or if they live more than 40 miles driving distance from the nearest VA facility (Draper, 2016, pp. 26-27). This alternative method of services for veterans is something that not only gives them a chance to seek care that better suites their needs (availability, geography, services), but also benefits family members that may be their only transportation. To identify recent VHA efforts to improve veterans’ timely access to primary care, the Choice Act intended to enhance veterans’ access to care, as well as relevant documents from VHA and medical centers in our review that outline steps taken to enhance or improve veterans’ access to primary care appointments (Draper, 2016, p. 6). Improving primary care in a timely manner is the main goal for this program, but there still are several issues it doesn’t answer for disabled veterans such as employment.

Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment (VR&E)

Service members with severe injuries or illnesses may automatically qualify for VA Vocational Rehabilitation benefits. If a service member has been referred to a Physical Evaluation Board or are going through the joint VA/DoD Disability Evaluation System, he or she may qualify for services to begin planning the transition to civilian life (Military News, 2012, p. 1). Although the VR&E is a program outside of the VHA, it still is connected to disabled service connected veterans and could be beneficial for researchers seeking to measure the number of veterans willing to work. Lastly, the overall focus should be on productivity and performance levels of all VHA employees, but there still should be a strong effort in implementing programs that allow veterans to live normally as possible.

Suggested Courses of Action

Hocker and Wilmot (2011) states the following on the importance of collaboration, “Collaboration shows a high level of concern for one’s own goals, the goals of the others, the successful solution of the problem, and the enhancement of the relationship” (p.168). The VHA will have to take the necessary steps in improving its operations by focusing internally and developing characteristics that strengthens its reputation. First there has to be a clear vision, mission, and goal that all employees need to be on board with from top to bottom. As author Kettl (2012) describes the role of leadership, “high performance in public agencies depends on leadership of top officials” (p.286). Top management and officials within the VHA have to lead by example to gain the trust of veterans who seek services from their facilities. New Veterans Affairs Secretary Bob McDonald has talked about bringing a culture of transparency to the department, but he proved it Monday by giving his cellphone number to a room of reporters — and having it aired live on C-SPAN (Klimas, 2014, p. 1). Transparency is one way to structure an organization that struggles with corruption and scandals, but in this case, implementing policy is more of an (formal) necessary approach to gaining the trust of the veterans.

Implementing Governmental Policies

For the past 20 years, scholars have suggested that when public agency responses to social problems are being examined, the focus has shifted from a government policy perspective to one of governance (Campbell, 2015, p. 76). Rather than focusing on the program itself, government policy focuses more on the tools or instruments in which the public sector operates. Next, developing an action plan that establishes a direction the organization needs to go will eventually shape how it functions. Any change within an organization has its obstacles, especially when it comes to implementing formal policies. Therefore, it is important for the VHA to be innovative in its approach towards creating policies such as performance focused evaluations and measuring veterans’ overall salinification with services. In the case of the VHA, the FY 2013 strategic plan identifies the federal government, health care providers, and the veterans/patients as primary actors in the delivery of health care services (Campbell, 2015, p. 78). Overall, the VHA will have to evaluate specific elements within its organization to recognized its flaws and keep accountability of every move it makes.

Accountability

According to Kettl (2010) define accountability standards for public organizations with the following, “Faithful obedience to law, to higher officials’ directions, and to standards of efficiency and economy” (p. 23). Accountability translates closely to efficiency, which is something that the VHA has lacked throughout the years. Professionalism is another characteristic that relates to accountability, in this case it is regarding VHA employees, veterans, and the obligations they have towards serving them. Considering the startling events of the last 10 years, it is a propitious time to gauge the attitudes of public managers toward ethics in government (Bowman and Knox, 2008, p. 627). Accountability is so vital in serving veterans because of the amount of care they require to have from their time in the service. Individual actions clearly can be affected by an agency’s written policies and unwritten expectations; indeed, many decisions in government must supersede individual preferences (Bowman and Knox, 2008, p. 629). In summary, leadership positions within the VHA must develop written policies that are understood all throughout the organization as well as keeps every employee accountable for their work.

Possible solutions

The VA’s performance management program has sought to fulfill its missions and visions by associating tracking measures with goals, including the development of quality indicators that reflected private sector performance measures (Kizer, Demakis, and. Feussner. 2000, p. 8). The quality of care in a timely manner is the goal that should be reached for the VHA. In developing a solution for the issues, the VHA has experienced in the past, they would have to take advantage of newly technological advancements. The VA needs to develop a detailed plan that addresses how to update the IT infrastructure, for the problems related to claims processing and integrating non-VA health records will not be resolved until there are updated software programs in place – ones that can integrate digital information from various sources and allow access to records by different departments (Kizer, Demakis, and. Feussner. 2000, p. 17). Implementing centralized software that allows all facilities to communicate better as well as hold records for a long period of time will benefit bother the VHA and veterans. Possible solutions that the VHA could develop to be more successful are by focusing more on employees’ performance levels, interpersonal issues within the VHA, and improving veterans overall experience.

Productivity

The stereotypical portrait of public-sector employees—ones who “punch the clock” each day and go about their work in a rigid and sedate manner, emphasizing rules and protocol above creativity and experimentation, preferring safety to risk-taking in their work—continues to this day (Hoff, 2003, p. 13). VHA employees will have to restrain from mediocre productivity because serving for the public in the healthcare field is far to serious to be taken lightly. During the mid-1900s, director Kenneth Kizer reorganized the VHA, which was on the verge of failing completely. Kizer implemented a service delivery structure that focused on funding for veteran populations, which also departures from the traditional budgetary focus on individual VHA facilities like medical centers. (Hoff, 2003, p.9) Lastly, solutions towards changing the current VHA will not be possible without the proper changes throughout the organization itself.

Timothy (2003) states the following stages that are vital to organizational change within VHA:

First, stage 3) Develop a compelling vision and strategy”, putting the responsibility in the leadership’s hands to formulate and articulate a vision that will guide all employees to achieving a successful change Second, stage 4) Communicate the vision widely”, basically initiating the vision that is in place by constantly communicating with employees to the point that they might be making personal sacrifices Third, stage 8) “Institutionalize change in the organizational culture”, which integrates a system where the change “sticks” and the mid-sets are permanently replaced with the new values/beliefs (p. 3).

Interpersonal Issues

Interpersonal conflicts within the VHA will not only cause distractions, but could also affect overall performances. A couple methods in retracting from interpersonal conflict are mediations, resolutions, and collaboration. Regardless of the position within this organization; approaching a conflict with an authoritative, compassionate, or purposeful approach could affect the overall result of any issue at a workplace. According to Hocker & Wilmot (2011)” They can agree that whenever a serious imbalance occurs the high-power party will work actively with low- power party to alter the balance in a meaningful way” (p. 140). Interpersonal conflict is a key problem in an ethical environment such as the VHA because the constant pressures of working with veterans. Success of governmental system such as the VHA translates a lot through the emotional barriers settled at a workplace. Mediators should be attuned to their own reactions to emotional displays, know their triggers and how they react when attacked (McCorkle & Reese, 2005, p. 128).

Improving Veterans’ experience

Department of Veterans Affairs -Budget in Brief (2016) state the following strategy to improving veteran experience with the following, “A Veteran walking into any VA facility should have a consistent, high-quality experience. To accomplish this, the Department has developed five strategies that are fundamental to the transformation in VA:

•Improving the Veterans’ experience. At a minimum, every contact between Veterans and VA should be predicable, consistent, and easy. However, under My VA, the Department is working to make each touch point exceptional.

•Improving the employee experience. VA employees are the face of VA. They provide the care, information, and access to benefits Veterans and their dependents have earned. They serve with distinction every day.

•Achieving support services excellence will let employees and leaders focus on assisting Veterans, rather than worry about back office issues.

•Establishing a culture of continuous performance improvement will apply lean strategies to help employees examine their processes in new ways and build a culture of continuous improvement.

•Enhancing strategic partnerships will allow the Department to extend the reach of services available for Veterans and their families” (p. 3).

Statistical Findings

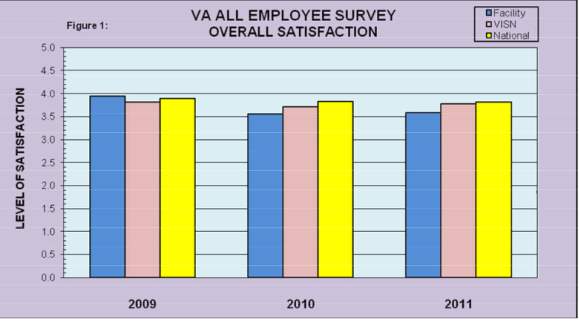

See Figure 1 below, it displays the Phoenix VA facility’s overall employee scores for 2009, 2010, and 2011. VISN and national scores are included for comparison because there aren’t other entities that targeted scores of employees’ satisfaction.

Figure 1

Employee satisfaction

Employee satisfaction

The results from this figure are consistent from a year to year basis, which is important because productivity can translate to high employee satisfaction. Furthermore, these results measure and enhance the accountability of all employees who work at the VHA. According to article entitled Deaths at Phoenix VA hospital may be tied to delay care by Dennis, Wagner “It appears there could be as many as 40 veterans whose deaths could be related to delays in care”(p.1).

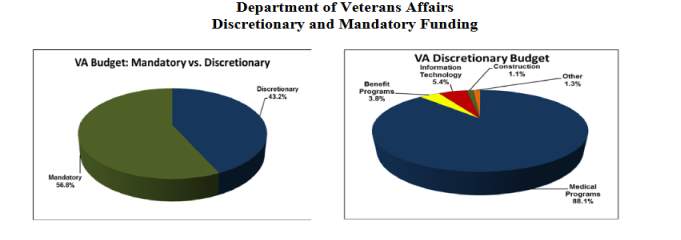

The data represented below in figure 2 represents the VA’s discretionary and mandatory funding. The request includes $103.9 billion in 2018 mandatory advance appropriations for Compensation and Pensions, Readjustment Benefits and Veterans Insurance and Indemnities benefits programs in the Veterans Benefits Administration (U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, 2016, p. 1).

Figure 2

Most of the expenses in figure 2 lean towards the veterans and other programs that are beneficial to them. Certain expectations of the resources spent on are expected within the VA budget, which only puts more pressure on its overall success. For example, Swain and Reed (2010) describe the reasons for not choosing a particular provision option with this statement, “The reasons for not choosing a particular provision option include: that the option is outside the purposes or mission of the organization; that the option does not truly serve the public interest; that the option is unlikely to succeed (government failure); and that resources are too scarce to allow that choice” (pp.199-200).

Conclusion

In order for the VA to thrive and improve its services in the future, it is imperative that future policies focus on addressing the critical issues identified in this paper. These issues are fundamental weaknesses that have plagued the VA system and cannot be resolved without an effective plan that focuses on achieving both short-term and long-term goals. Groups such as the VISN will play a huge role in measuring performance and service levels. It is necessary to collaborate with these types of groups in ensuring and verifying that veterans are receiving high-quality medical care. Collaboration partners build trust by sharing resources such as information and demonstrating competency, good intentions, and follow-through; conversely, failing to follow through or serving one’s own or one’s organization’s interests over the collaboration undermines trust (Chen 2010, p. 21). Furthermore, the VHA must improve the continuity of its overall services, especially for aging and disabled veterans. All in all, the main issues identified in this paper will always exist within this organization, which makes it important to develop strategies that focus more on innovations versus short-term operations.

Reference

ADMINISTRATION: American Journal of Public Health, 96(6), 956. Retrieved from, https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.nau.edu/docview/215083889/fulltextPDF/9B56C4C226E646CFPQ/1?accountid=12706

Amara, J., Pogoda, T., Krengel, M., Iverson, K., Baker, E., & Hendricks, A. (2014). Determinants of Utilization and Cost of VHA Care by OEF/OIF Veterans Screened for Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Military Medicine, 179(9), 964-972. Retrieved from, http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.lopes.idm.oclc.org/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=af3e09b6-e778-493f-b7a6-4b18f4eb7af6%40sessionmgr4008

Anderson, S. B. (2014). “Data Resources: VA Disability Backlog.” Medill National Security Zone: A Resource for Covering National Security Issues. Retrieved from, http://nationalsecurityzone.org/site/resources-va-disabilitybacklog/.

Berman, Evan M., James S. Bowman, Jonathon P. West, and Montgomery R. Van Wart. (2016). Human Resource Management in Public Service: Paradoxes, Processes, and Problems. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Billitteri, Thomas J., Marcia Clemmitt, Peter Katel, Rachel Cox, Sarah Glazer, Alan Greenblatt, Reed Karaim, (2010). “Caring for Veterans: Does the VA Adequately Serve Wounded Vets?” CQ Researcher 20, no. 16 (April); 361-384.

Byrd, K., Gifford, E., McCutcheon, S., Glynn, S., Roberts, Michael C., Barnett, Jeffrey E., & Sherman, Michelle, D. (2011). Family and Couples Treatment for Newly Returning Veterans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(1), 47-55. Retrieved from, http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.libproxy.nau.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=d74827f1-7e13-42a6-b7e6-e82c0f999964%40sessionmgr4010

Campbell, C. (2015). Reducing Waits for VHA Services Through Use of Tools of Governance. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 1-12.

Chambers, John W., ed. (1999). The Oxford Companion to American Military History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cooper, Mary H., William Triplett, Sarah Glazer, David Hatch, David Hosansky, Patrick Marshall, Tom Price, and Jane Tanner. (2004) “Treatment of Veterans.” CQ Researcher 14, no. 41: 973-996.

Copeland, Zeber, Bingham, Pugh, Noël, Schmacker, & Lawrence. (2011). Transition from military to VHA care: Psychiatric health services for Iraq/Afghanistan combat-wounded. Journal of Affective Disorders, 130(1-2), 226-230. Retrieved from, http://ac.els-cdn.com.libproxy.nau.edu/S0165032710006312/1-s2.0-S0165032710006312-main.pdf?_tid=5dbfada8-7704-11e7-a5bc-00000aab0f6c&acdnat=1501624810_45ac204a97222228fdfd6edd640d433a

Depalma, & Hoffman. (2016). Combat blast related traumatic brain injury (TBI): Decade of recognition; promise of progress. Behavioral Brain Research, Behavioral Brain Research. Retrieved from, http://ac.els-cdn.com.libproxy.nau.edu/S0166432816305538/1-s2.0-S0166432816305538-main.pdf?_tid=b87c176e-77ad-11e7-9584-00000aab0f27&acdnat=1501697548_4fa72a4ccad3cda36f592ff3a8151380

Draper, D. (2016). VA HEALTH CARE: Actions Needed to Improve Newly Enrolled Veterans’ Access to Primary Care GAO Reports. Retrieved from, EBSCOhost, lopes.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ulh&AN=114611102&site=eds-live&scope=site

Gold, Hadas. (2014). “Anatomy of a Veterans Affairs Scandal.” POLITICO, Retrieved from, http://www.politico.com/story/2014/05/veteransadministration-scandal-106982.html.

Hans Petersen (2015). Veterans Health Administration: Roots of VA Health Care Started 150 Years Ago. Vermont Avenue, NW Washington. Retrieved from, https://www.va.gov/HEALTH/NewsFeatures/2015/March/Roots-of-VA-Health-Care-Started-150-Years-Ago.asp

Hayward, R. (2017). Lessons from the Rise- and Fall of VA health care. Journal of general Internal Medicine, 32(1), 11-13. Retrieved from, https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs11606-016-3865-1.pdf

Hoff, Timothy J. (2003). The Power of Frontline Workers in Transforming Government: The Upstate New York Veterans Healthcare Network .University at Albany, SUNY.

Hoff, Timothy J. (2003). The Power of Frontline Workers in Transforming Government: The Upstate New York Veterans Healthcare Network .University at Albany, SUNY

Jaffe, Greg, and Ed O’Keefe. (2014). “Obama Accepts Resignation of VA Secretary Shinseki.” The Washington Post. Accessed October 18, 2014. http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/shinseki-apologizes-for-va-health-carescandal/2014/05/30/e605885a-e7f0-11e3-8f90-73e071f3d637_story.html.

Johnson, William C. (2004). Implementation and Evaluation in Public Administration: Partnerships in Public Service. 3rd ed. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press (Chapter 13, pp. 303-329

Kearney, L. K., Smith, C., Kivlahan, D. R., Gresen, R. C., Moran, E., Schohn, M., & … Zeiss, A. M. (2017). Mental Health Productivity Monitoring in the Veterans Health Administration: Challenges and Lessons Learned. Psychological Services, doi: 10.1037/ser0000173.

Kettl, D.F. (2012). The Politics of the Administrative Process (5th Ed.). Washington, D.C.: CQ Press

Kizer, K. W., & Jha, A. K. (2014). Restoring trust in VA health care: New England Journal of Medicine, 371(4), 295-297.

Kizer, Kenneth W., John G. Demakis, and John R. Feussner. (2000). “Reinventing VA Health Care: Systematizing Quality Improvement Quality Innovation.” Medical CARE 38, no. 6: I-1-I-16. Retrieved from, www.jstor.org/stable/3767341.

Klimas, Jacqueline. (2014). The Washington Times: VA secretary Bob McDonald puts his cellphone number where his mouth is. Retrieved from, http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2014/sep/8/va-secretary-bob-mcdonald-puts-his-cellphone-numbe/

McQueen, L., Mittman, B.S., & Demakis, J.G. (2004). Overview of the veterans’ health administration (VHA) quality enhancement research initiative (QUERI). Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 11 (5), 339-343.

Military News. (2012). VA Offers Benefits and Services for Veterans Looking for Work: Exceptional Parent, 42(7), 49. Retrieved from, http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.lopes.idm.oclc.org/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=25&sid=d7250aea-274c-4612-a52f-b76873b51272%40sessionmgr101

Panangala, Sidath, V. (2016). Health Care for Veterans: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved from: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42747.pdf

Panangala, Sidath, V. (2017). The Veterans Choice Program (VCP): Program Implementation. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved from: https://fas.org/spg/crs/misc/R44562.pdf

Perlin, Jonathan, B. Kolodner, Robert M. and Roswell, Robert H. (2004). The Veterans Health Administration: Quality, Value, Accountability, and Information as Transforming Strategies for Patient-Centered Care. Retrieved from, http://www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2004/2004-11-vol10-n11pt2/nov04-1955p828-836/

Phelps, R. (1997). VHA Policy-Related Clinical Ethical Issues. HEC Forum, 9(2), 159-168. Retrieved from, https://link-springer-com.libproxy.nau.edu/content/pdf/10.1023%2FA%3A1008827106544.pdf

Rainey, Hal G. (2014). Understanding and Managing Public Organizations. 5th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Shear, Michael D., and Richard A. Oppel. (2014). “VA Chief Resigns in Face of Furor on Delayed Care.” New York Times. Retrieved from, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/31/us/politics/eric-shinseki-resigns-as-veteransaffairs-head.html.

Simpson, S. (2006). SAFETY NET LESSONS FROM THE VETERANS HEALTH

Starling, Grover. (2008). Managing the Public Sector. 8th ed. Boston: Wadsworth

The Republic. (2015). The Arizona Republic: The road to VA wait-time scandal. Retrieved from, http://www.azcentral.com/story/news/arizona/politics/2014/05/10/timeline-road-va-wait-time-scandal/8932493/

U.S. Department of Veterans Affair. (2017). History: VA History. NW, Washington. Retrieved from, https://www.va.gov/about_va/vahistory.asp

United States, Congress. (1997). Gulf War veterans’ illnesses: VA, DOD continues to resist strong evidence linking toxic causes to chronic health effects: Second report by the Committee on Government Reform and Oversight, together with additional views. U.S. G.P.O. Retrieved from, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pur1.32754067873558;view=1up;seq=6

Wittrock, S., Ono, S., Stewart, K., Reisinger, H., & Charlton, M. (2015). Unclaimed Health Care Benefits: A Mixed-Method Analysis of Rural Veterans. The Journal of Rural Health, 31(1), 35-46. Retrieved from, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.libproxy.nau.edu/doi/10.1111/jrh.12082/full

Wu, R. Ryanne, Kinsinger, Linda S., Provenzale, Dawn, King, Heather A., Akerly, Patricia, Barnes, Lottie K., Jackson, George L. (2014). Implementation of New Clinical Programs in the VHA Healthcare System: The Importance of Early Collaboration between Clinical Leadership and Research. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29(4), 825. Retrieved from, https://link-springer-com.libproxy.nau.edu/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs11606-014-3026-3.pdf

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Health and Social Care"

Health and Social Care is the term used to describe care given to vulnerable people and those with medical conditions or suffering from ill health. Health and Social Care can be provided within the community, hospitals, and other related settings such as health centres.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: