Voluntary Turnover in the Hospitality Industry: Why Do Employees Leave?

Info: 11357 words (45 pages) Dissertation

Published: 11th Dec 2019

Tagged: EmploymentHospitality

Executive Summary

The Hospitality industry is as prominent in the United Kingdom as it is worldwide. The labour force is comprised by a wide range of people from cultures across the globe. It is because it’s dynamic ever changing nature of the workforce that led the researcher to observe it.

The topic of this research project is voluntary turnover of hospitality employees, as staff turnover has been a long standing issue within the hospitality industry, it is a suitable subject for research however so broadly is the topic of labour turnover it was imperative to narrow the scope to just voluntary turnover. Though involuntary has a significant impact on the hospitality industry, focusing on one aspect of turnover could yield more refined results. Voluntary turnover is believed to have an effect on hospitality businesses performance including profitability so if it was to understood then the reasons why employees had to be identified.

Based on sources in the Literature Review certain themes were identified and some prominent precursors for hospitality employees’ turnover intention were human resources topics such as pay, stress and job satisfaction. A limitation of the sources identified is that there was no apparent dominant reason for choosing to leave a hospitality organisation. Therefore there was a requirement to collect primary data in attempt to identify the most prominent reasons for employees have when deciding to leave a hospitality organisation. Prior to this data collection methods needed to be justified in the Methodology section.

In the Methodology section the primary data approach was considered. It was stated that 50 minimum ex-employees of hospitality organisations who had ever voluntarily left a hospitality business would be targeted as it was anticipated that results would be more reliable, representative and valid. Respondents would be known to the researcher to ensure that they had actually worked within a hospitality organisation to build up an accurate picture. A predominantly quantitative questionnaire was selected as the desired method of data collection as interviews were deemed too time consuming and more difficult to analyse and interpret. A pilot study was distributed to five individuals with few issues to report, though notably one issue was similarity between two question responses, this was then hidden from respondents but appeared in results graphs with no data and is acknowledged in Appendix 7.2.

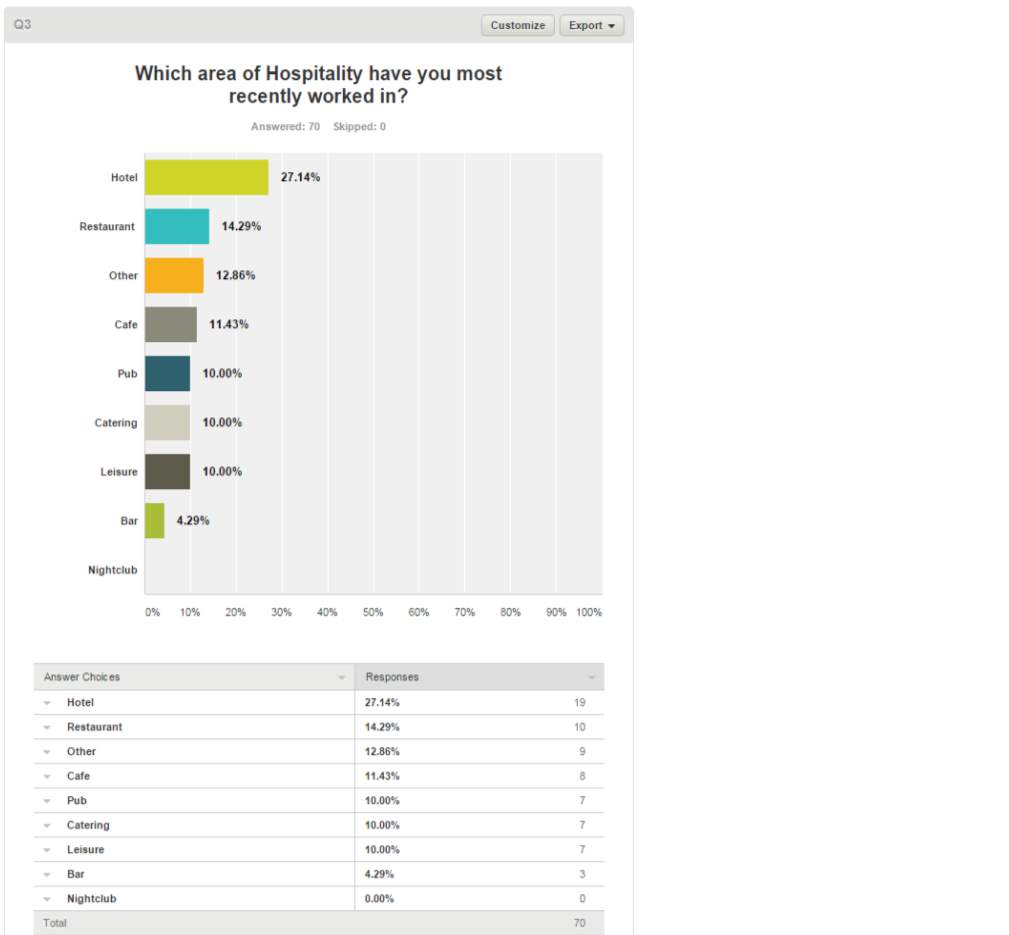

Primary research was then conducted 70 respondents took the questionnaire via surveymonkey.com. 51.43% of respondents were women and 48.57% were men as near total gender parity was achieved. However the sample population were overwhelmingly in the 18-24 bracket as 64.29% identified in this group. Most respondents also identified as having most recently working in Hotels as 27.14% stated this type of hospitality organisation. Themes identified in the Literature Review were used as question options. Primary findings indicated that the three most common reasons for voluntary turnover in organisation were a manager’s methods, pay and job satisfaction respectively according to their individual category of question. Though there limitations in the primary data collection stage as in some cases it was difficult to establish the overall dominant reason for leaving for example there was very little between stress and fatigue.

In the conclusion section it was acknowledged that many respondents’ situations were subjective so one may consider the impact on the results. Some limitations were identified including that it was difficult to find the one dominant reason for employees to choose to leave a hospitality organisation.

Recommendations were also made and as literature offered suggestions to combat turnover in the hospitality industry. As previously stated within the boundaries of this research the most prominent reasons for voluntary employee turnover were a manager’s methods, pay and job satisfaction therefore it was stated that these issues could be focused on by a hospitality manager. This section also acknowledged that the issue still requires extensive research to provide further clarity regarding voluntary turnover in the hospitality sector. It was recommended that in hindsight interviews, which were previously disregarded, may have aided the researcher build up a more accurate picture of the situation surrounding hospitality voluntary turnover.

Contents

- Introduction

1.1 Business Drivers & Organisational Context. …………………………8-9

1.2 Research Aim…………………………………………………………….10

1.3 Research Objectives……………………….……………………………10

- Literature Review

- Introduction………………………………………………………………11

- What factors influence employees to want to leave an organisation?.………………………………………………………..12-13

- Job satisfaction as a possible influence of staff turnover in organisations…………………………………………………………13-14

- What are some of the reasons employees leave hospitality organisations?…………………………………………………………………..14-15

- Impact of high staff turnover on the hospitality industry……………………………………………………………….16-17

- Combatting staff turnover in hospitality……………………………17-19

- Summary…………………………………………………………………19

- Methodology

- Research approach……………………………………………………..20

- The questionnaire method……………………………………………………….20

- Questionnaire Design, Sample Frame & Distribution.…………..21-22

- Pilot study………………………………………………………………..22

- Ethics…………………………………………………………………22-23

- Limitations……………………………………………………………23-24

- Presentation and analysis of data

- Profile of respondents………………………………………….……25-27

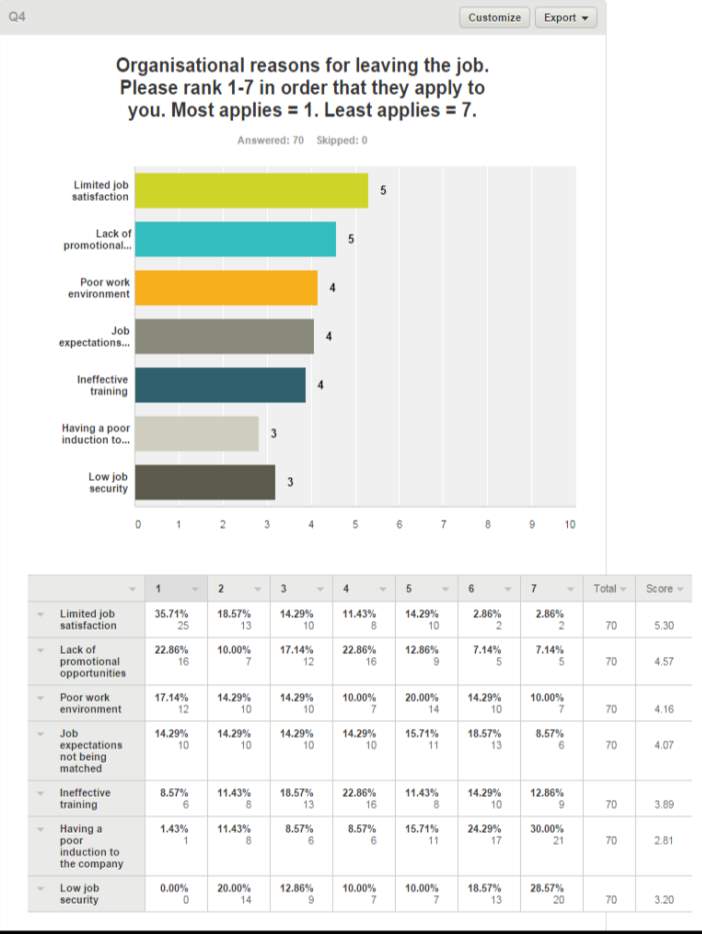

- Organisational reasons for leaving the job…………………….…28-29

- Rational reasons for leaving job……………………………………30-31

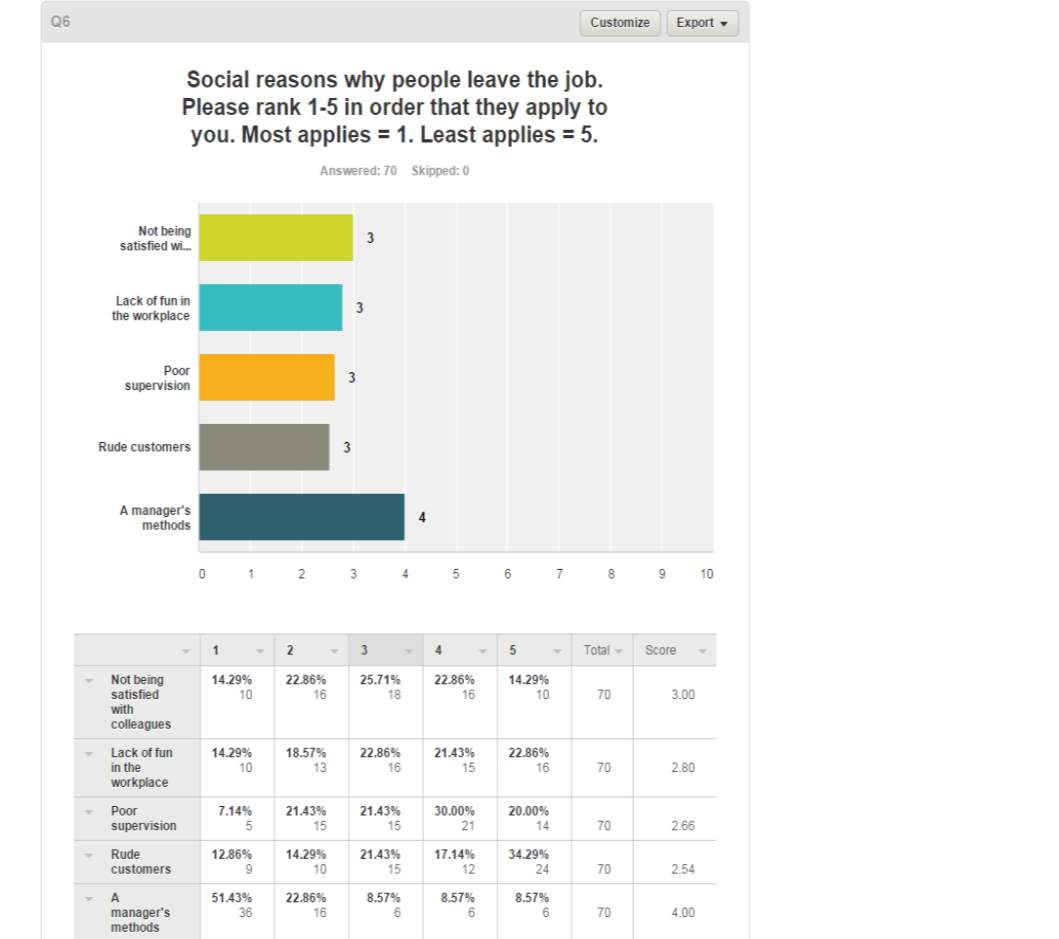

- Social reasons for leaving job…………………………………………..32

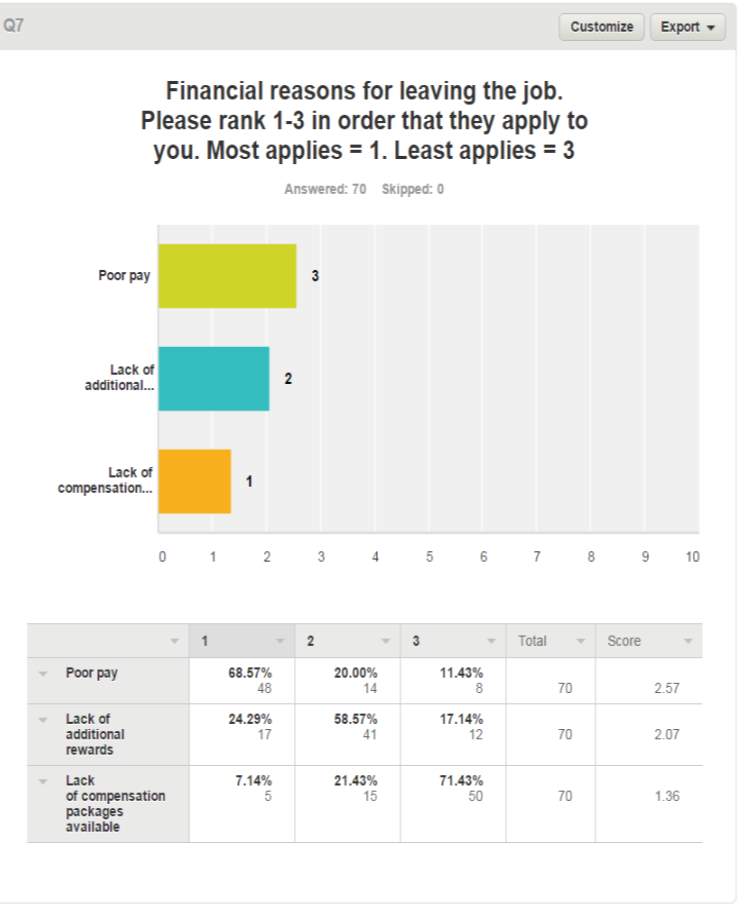

- Financial reasons for leaving job……………………………………….33

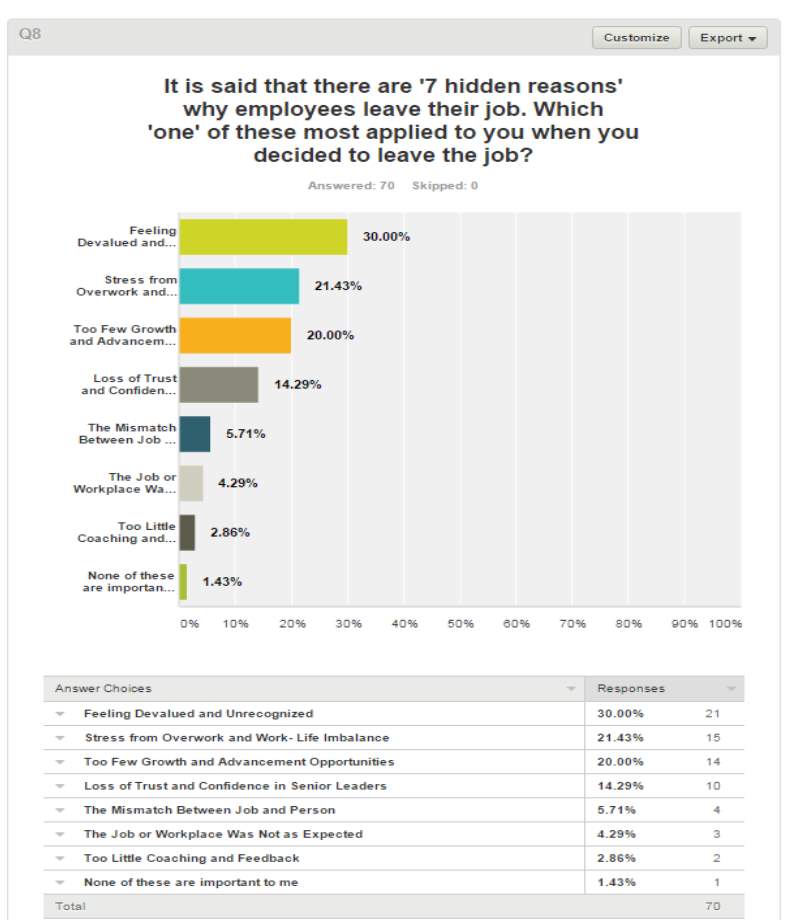

- The ‘7 hidden reasons for leaving a job…………………………..34-35

- Respondents’ current situation…………………………………….36-37

- Conclusions & Recommendations

- Conclusion……………………………………………………………..38-39

- Recommendations…………………………………………………..39-41

- Bibliography……………………………………………………42-48

- Appendices

- Ethics Approval Form……………………………………………….49-53

- Questionnaire………………………………………………………..54-62

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Business drivers & Organisational context

The hospitality industry is a recognised and key industry within the United Kingdom. The scope and nature of the industry is such that it encapsulates many types of organisations including; hotels, restaurants, catering, event management and agency employment and all other related services. Arguably it overlaps with the tourism sector with holiday parks and visitor attractions being examples. It may be difficult to pinpoint where the hospitality industry begins and ends (Mullins and Dossor, 2013, p3).

Staff turnover has been prevalent in hospitality businesses in the UK. The hospitality industry had been known for high turnover. It is either voluntary, where employees leave by their own accord or involuntarily where the decision may be made for them. Ford, Sturman & Heaton (2012, p188) state that Hospitality jobs can often have poor working conditions, poorly paid positions where many employees’ career aspirations cannot be met.

There have been various studies conducted in many fields in many countries regarding labour turnover. There are varying degrees of interpretations particularly around the motives to leave, the industry is arguably transient in nature and perhaps always will be and voluntary turnover is inevitable whatever steps are taken in order to combat it.

High labour turnover can be perceived to be a problem for the industry. High staff turnover is costly for hospitality businesses (Lean, 2015). There is also a perception that high staff turnover can harm business’ performance (Gaskell, 2014). As it can have a knock on effect regarding the profitability of a business if the labour force is not at an optimal level. There are also additional costs accumulated as a result of turnover such as hiring and training new staff.

The issue of staff turnover falls into the Human resources aspect of a business, though it arguably has other implications for different aspects of businesses such as finance. Traditional themes that a Human Resources manager may encounter such as pay, reward and job satisfaction are evident in this project. High labour turnover can be to detriment of a successful human resource manager due to the lack of workforce stability created as a result. Labour turnover is much researched topic not only in the United Kingdom but also worldwide. This project seeks to further this research. Boella & Goss-Turner (2013, p163).

1.2 Research Aim

Ultimately the aim of this research project is to identify reasons why employees voluntarily leave hospitality organisations via secondary research undertaken in the Literature Review section and then test reasons and themes identified via primary research illustrated in thePresentation and analysis of data section to see which were considered to be the most important. Based on methods considered in the Methodology section, the researcher would then look to be in a position to make formal conclusions and recommendations where appropriate in the Conclusions & Recommendations section of the project.

1.3 Research Objectives

- To find and investigate common reasons for voluntary turnover in the hospitality industry

- To evaluate the perceived importance of key reasons for voluntary turnover.

2.0 Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

This is a review of literary sources surrounding the initial question of ‘Voluntary turnover in the hospitality industry: Why do employees leave?’ According to Koslowsky & Krausz (2002, p54) the concept of voluntary turnover is ‘commonly viewed as the termination of formal relations between an employee and organisation’.

According to a report from the British Hospitality Association (2015) regarding the economic contribution of the hospitality industry ‘in 2014, employment in the UK hospitality industry stood at 2.9 million jobs’, which is the equivalent of 9% of total UK employment. It contributed an estimated £57 billion or 4% of the UK Gross Domestic Product in the same year. Compared to other sectors, hospitality ranks 11th out of 17 industries and its contribution is greater than the likes of Agriculture and the Arts but just behind Transportation and Storage and significantly behind Wholesale and Retail. According to the labour rates survey (2015) in 2014 the total average turnover in the UK was at 20.7% and Hotels, catering and leisure industry had the highest average total turnover rate of 32.7% in the whole of the private sector. Michel (2014) highlights that as of the end of 2014 the rate is much higher at 66% and 60% for waiting and bar staff respectively.

2.2 What factors influence employees to want to leave an organisation?

According to Schyns, Torka & Gossling (2007, p660) turnover intention is defined as an employee’s intention to voluntarily change jobs or companies’. Hinkin and Tracey (2000, p21) of Cornell University argued that ‘Turnover is caused primarily by poor supervision, a poor work environment, and inadequate compensation’. Ertas (2015, p418) took an alternative view and argued that ultimately ‘The most important predictor of quit intention is overall job satisfaction’. There are alternate opinions such as Johnston & Spinks (2013, p35) who ‘found no significant relationship between organisational climate and employee turnover intention’ and they consider different motives such as workplace stress or perceptions of employment security. The stress factor is identified by Scanlan & Still (2013, p317) who conclude that ‘stress and fatigue’ was associated with higher turnover intention.

Hayes and Ninemeier (2009, p265) highlighted the importance of extrinsic rewards as for many workers ‘an equitable compensation program that considers pay, as well as all other employee rewards is critical’, also ‘those employers who seek to minimise the amount paid to their employees tend to lose the best of their workers to other organisations that are willing to pay more’.

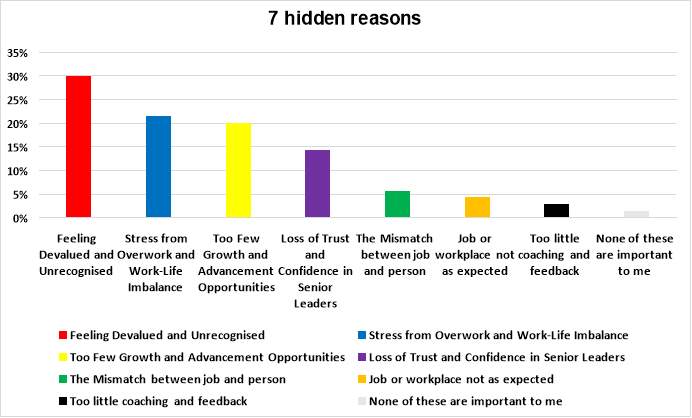

Branham (2005) highlighted seven hidden reasons why employees leave, they are: the job or workplace was not as expected, a mismatch between job and person, too little coaching and feedback, few growth and advancement opportunities, feeling devalued and unrecognised, stress from overwork and work-life imbalance and loss of trust and confidence in senior leaders.

2.3 Job satisfaction as a possible influence of staff turnover in organisations

The annual Jobs Exodus Survey (2015) found that 60% of UK workers were not happy in their jobs. This was a 10% increase since the start of 2014, a lack of job satisfaction was cited as the number one reason to change jobs, as 48% of respondents felt they would be happier elsewhere. According to the British Social Attitudes Survey (2012) out of employees in twenty countries surveyed, only six were more dissatisfied than the UK regarding their jobs and work-life balance. A long-hours culture and prominence of unpaid work were cited as influences. Despite this, job satisfaction had increased here since the start of the economic downturn.

Based on previous research Barrows (1990, p25) summarised job satisfaction as having ‘a consistent negative relationship to turnover; those ‘dissatisfied on the job have been found more likely to leave than their satisfied counterparts’.

However there are alternative interpretations available. Holtom, Mitchell, Lee & Inderrieden (2005, p349) somewhat challenge the concept of job satisfaction being a predictor of voluntary turnover. They consider external, positive or negative events that may influence an employee and considers the complexity experienced by individuals who simultaneously manage careers and non-work issues. Mullins (2013, p244) stated that ‘job satisfaction is affected by a wide range of individual, social, organisational and cultural variables’.

2.4 What are some of the reasons employees leave hospitality businesses?

Hornsey & Dann (1984, p15) state that ‘in many nations the hotel & catering industry is one of low prestige and poor pay, the effect of this is that there tends to be relative ease into the industry, which attracts transient labour’. Riley (1996, p142) also acknowledged the hospitality industry’s reputation for high levels of turnover which was attributed to ‘arbitrary behaviour of supervisors and managers’ as unfair action could influence employees to quit the job, the ‘induction crisis’ which is seen as an endemic in the industry because the job for example, may not be seen as compatible with their non-work life and also the ‘distribution of effort and rewards’ as personnel may expect to be rewarded for staying longer so the ‘transient population may be turned into permanence’ if these aspects of human resource management are mismanaged.

Boella & Goss-Turner (2013, p167) like the sources regarding turnover in the wider organisational context cite similar influences. ‘Poor pay conditions, long hours, ineffective training, a lack of promotional opportunities and also the general stressfulness and pressures of service encounter work’. Pizam & Thornburg (2000, p217) considered work-related and personal characteristics that contributed towards turnover. They surveyed absenteeism and voluntary turnover in hotels. Respondents felt that pay, job and co-worker satisfaction and whether pre-job expectations were matched were the most important influences to voluntary turnover. Han, Bonn & Cho (2016, p103) found ‘significant and positive relationships between customer incivility, employee burnout and their turnover intention’ when studying frontline employees of restaurants. Roberts (1995, p82) added extra factors that influenced labour turnover, such as the ‘induction process failing to create the right working relationship, inadequate or ineffective management, individuals appointed over their skill level or promotion to another company’ but interestingly he claims that ‘pay is rarely the reason for employees leaving an organisation’.

2.5 Impact of high staff turnover on the hospitality industry

A report compiled by People First (2014) outlines the current state of Hospitality in the UK. According to this report, staff turnover costs the industry £274m per annum which is 48% of the total industrial economic contribution and 365,675 people leave every year which is approximately 12.6% of the total employed in the industry based on 2014 figures.

The report gives some context to its study and states that 35% of the workforce are under 25, which as it is implied by their research means the labour force is partially comprised of short term workers who have traditionally suited the flexible nature of the industry. It is implied that demographics of employees is a contributing factor towards turnover.

Lashley (2001, p22) referred to ‘three key phases in the severance of an existing employee, which were the costs associated with finding a replacement; and the cost of bringing the new recruit into the organisation and their development to full effectiveness’. Iverson & Deery (1997) concluded that there is a turnover culture in hospitality and claim that as a result costs to businesses have increased and quality of service has been reduced. Gustaffson (2002, p112) observed private clubs in the USA and concluded that turnover and labour shortage is impacting the industry across the board. It is stated that ‘the hospitality industry is not well positioned to pay high wages’. As a result there may be little motivation to remain in an organisation. Davidson, Timo & Wang (2010, p462) attributed high staff turnover as being a contributor towards ‘intangible costs such as loss of productivity and service quality’. They also noted additional but tangible costs of turnover revolving around management of time and further costs spent on training new employees.

2.6 Combatting staff turnover in hospitality

Walker & Miller (2012, p354) considered some strategies for retaining employees, notably holding ‘50/50 meetings’ where management talks about goals and vision and employees can raise their own questions and issues, walking and discussing day to day issues with employees and conducting exit interviews as a chance to get to the ‘real dissatisfiers’ that employees may have’ to limit turnover. Mohsin, Lengler & Aguzzoli (2015, p46) concluded that ‘managers must monitor organisational enthusiasm and create stimulation in the job’. However it was stated that providing the ‘good things’ to employees does not necessarily guarantee that they won’t quit the job. Robinson, Kralj & Solnet (2014) concluded that because of the influence hospitality employees have on consumer satisfaction and the performance of their companies, a greater understanding may be required in order to rationalise employee retention in hospitality. Deery & Jago (2015, p467) highlighted the need for employers to manage employees’ work life balance by implementing well developed and relevant training programmes, the provision of promotional opportunities, and the genuine interest by managers in the well-being of employees’ family and personal lives’ in order to retain talented staff who may also have other career opportunities.

Dhanani (2014) described employee turnover as an unavoidable circumstance in the hospitality industry and suggested talent management strategies to reduce turnover such as setting expectations and goals clearly to employees or giving them ongoing feedback and direction.

Chan & Kuok (2011, p 437) also made a case for development training which would increase commitment and indicated that Human Resource managers could gain from implementing talent management strategies to develop personnel of the highest quality. Cobb (n.d.), another advocate for using talent management strategies cited fair and consistent performance appraisals, succession programs where internal talent pools are developed and regular feedback is given to employees regarding their performance. Baum (2008, p728) also agreed and stated ‘enhancing the work environment, notably in terms of conditions and remuneration, are areas where employers in hospitality and tourism can seek to attract and retain talented employees at all levels’. However Lundberg & Armatas (1974, p39) argue for the need to draw attention to turnover by ‘compiling a monthly labour turnover report’, which can be sent to departmental heads and serves to point out the problem for both the department head and management. However Tews, Michel & Stafford (2013, p372) argue that ‘fun may be an antidote to the turnover challenge, since most individuals want more from work than financial compensation’.

2.7 Summary

Research questions will be based on secondary research conducted in this review. Themes have been identified in this review including: job satisfaction, promotional opportunities, work environment, job expectations, training, inductions, job security, stress, long hours, fatigue, pressure.

Additional themes have also been cited including; colleague satisfaction, managers, workplace fun, supervision, customers, pay, reward and compensation. Finally the seven hidden reasons (Branham, 2005) contributed reasons such as devalued and unrecognised employees and those that had worked in positions with few growth and advancement opportunities. Primary research will be geared towards the emphasis placed on these themes by ex-employees of hospitality businesses in order to further understand causes of voluntary turnover in hospitality.

3.0 Methodology

3.1 Research Approach

According to Horn (2009, p135) ‘primary data refers to data that has been collected for the study in which it is used’ and consists of quantitative and qualitative approaches. According to Kothari (2004, p3) ‘quantitative research is based on the quantity or amount’ whereas ‘qualitative research is concerned with phenomena relating to quality or kind’. A predominately quantitative approach was used. A quantitative method can be practical. Cooper & Schindler (2013, p147) regard quantitative approaches as ‘clear distinction between judgements and facts’ and also ‘limited involvement from the researcher to prevent bias’.

3.2 The questionnaire method

The researcher sought to use the questionnaire method. This was preferred to methods like interviews as Ghauri & Gronhaug (2002, p102) highlight that ‘interviews are difficult to interpret and analyse’. Interviews can be time consuming so they were deemed unnecessary for gathering primary data in this research. According to Maylor & Blackmon (2005, p185) researchers may have a ‘hard time maintaining consistency across interviews’. Whereas in a questionnaire that is very quantitative, research may be more objective. Hwee- Ang (2014, p11) said of objectivity that ‘research process are not tainted by subjective biases’.

3.3 Questionnaire Design, Sample Frame & Distribution

Quinlan (2011, p337) highlights key issues surrounding questionnaire design such as: ‘content of questions’, their ‘construction and presentation’ and the ‘order’ and ‘length of the questionnaire’. The researcher distributed the questionnaire online via ‘surveymonkey.com’ and aimed to gain 50 respondents minimum in order to be representative. The researcher attained this response rate via direct messages to respondents. The design of the questionnaire was geared towards how much emphasis ex-hospitality employees place on reasons to leave the organisation.

Sekaran & Bougie (2009, p267) define a sample frame as ‘a (physical) representation of all the elements in the population from which the sample is drawn’. The sample was ex-employees of hospitality organisations who have voluntarily left. The researcher contacted known ex-employees of hospitality organisations directly. This defined target audience of known respondents who have left hospitality businesses enabled the researcher to attain accurate results. Respondents ranked reasons for leaving the job which were identified in the Literature review. When data was analysed the design of the questionnaire contributed to a macro view of the issue of voluntary turnover in hospitality.

The researcher specifically targeted respondents who had worked in hospitality via Facebook. They were selected in order of how they appeared on the researcher’s contact list. They were all briefed about ‘surveymonkey.com’ and the background to the research before commencing it. Respondents were not obliged to fill out the questionnaire and could opt out if they wished.

3.4 Pilot study

Bryman & Bell (2011, p263) state that piloting ‘allows the researcher to determine adequacy of instructions’ and consider ‘how well the questions flow’. Gaining feedback on areas such as these enabled the researcher to refine the structure and wording of questions and ultimately lead to valid data collection. A pilot study was sent out prior to distributing the formal questionnaire.

The questionnaire was shown to five different individuals who had diverse backgrounds and based on feedback it was felt that the ranking option of question 5, ‘Burnout’ was too similar to the option of ‘Fatigue’ therefore it was hidden from respondents in the final questionnaire however the category appeared in the graph analysis on ‘surveymonkey.com’, this is also acknowledged in Appendix 7.2.

3.5 Ethics

Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill (2009, p184) state that ethics ‘relates to questions about how we formulate and clarify our research topic, design our research, gain access, collect data, analyse data and write up our research in a moral and responsible way’. There were some ethical considerations prior to commencing primary research such as confidentiality and reliability. Wilson (2010, p88) states ‘confidentiality focuses on the data collected’ and information provided will be adhered to in the strictest confidence. Saunders & Lewis (2012, p128) describe reliability as ‘the extent to which data collection methods and analysis procedures will produce consistent findings’.

The researcher protected the identity of respondents by not validating open response fields. It was anticipated that consistent findings will be presented due to the use of closed questions. Respondents were not required to submit names in response fields and if there was any indication to an individual’s identity then it would not have been placed in the public domain. Therefore confidentiality and anonymity was guaranteed to respondents.

Prior to commencing research the researcher completed an ethics form was signed with no issues to report (see Appendix 7.1).

3.6 Limitations

According to Glenn (2010, p144) regarding research methods ‘a concern has been validity; the value of research has been stronger when both the data and design are valid’.

There is a limitation surrounding the target audience of the research. As the researcher specified contacting ex-employees of hospitality organisations directly risked restricting the frame to those known to the researcher. There was a perceived risk of respondents having too similar experiences to the researcher and affecting the reliability of the research. As there was a clearly defined sample in the primary stage then the risk of undesired respondents completing the questionnaire was minimal. With these assurances the research could be replicated in the future. Though contrary to this limitation all respondents had either worked or were still working in the hospitality industry.

4.0 Presentation and analysis of data

4.1 Profile of respondents

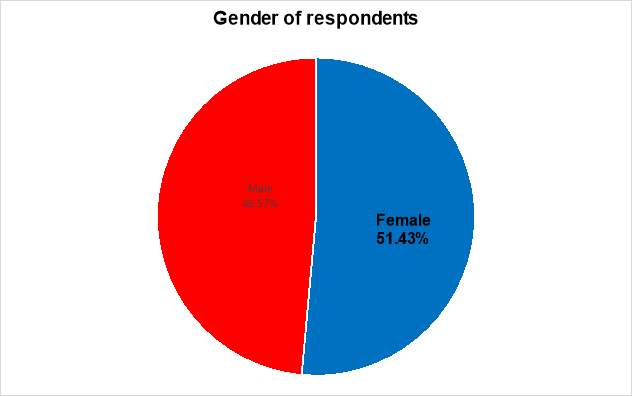

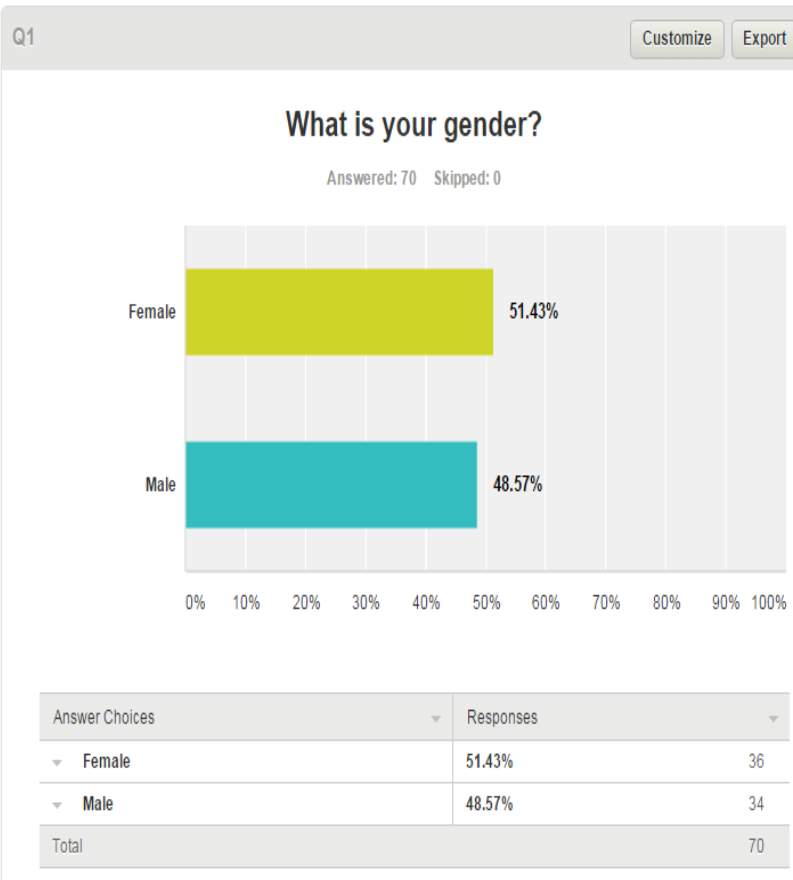

Respondents were targeted as those known to the researcher as having worked in a hospitality organisation via direct messaging. This was to ensure that the desired, representative sample population completed the survey. Respondents were asked to disclose their gender. Of the 70 respondents who participated in the survey, 51.43% were women and 48.57% were men. There was not much disparity between the gender ratios of respondents. See Figure 1.0 for the gender of respondents.

Figure 1.0

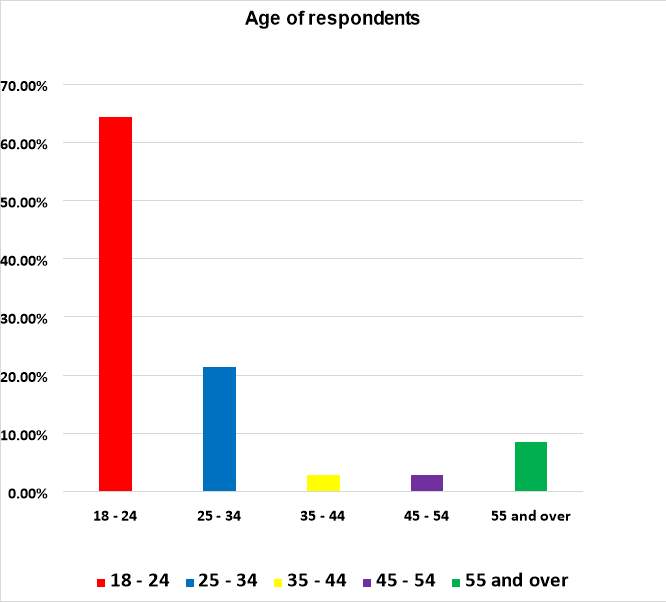

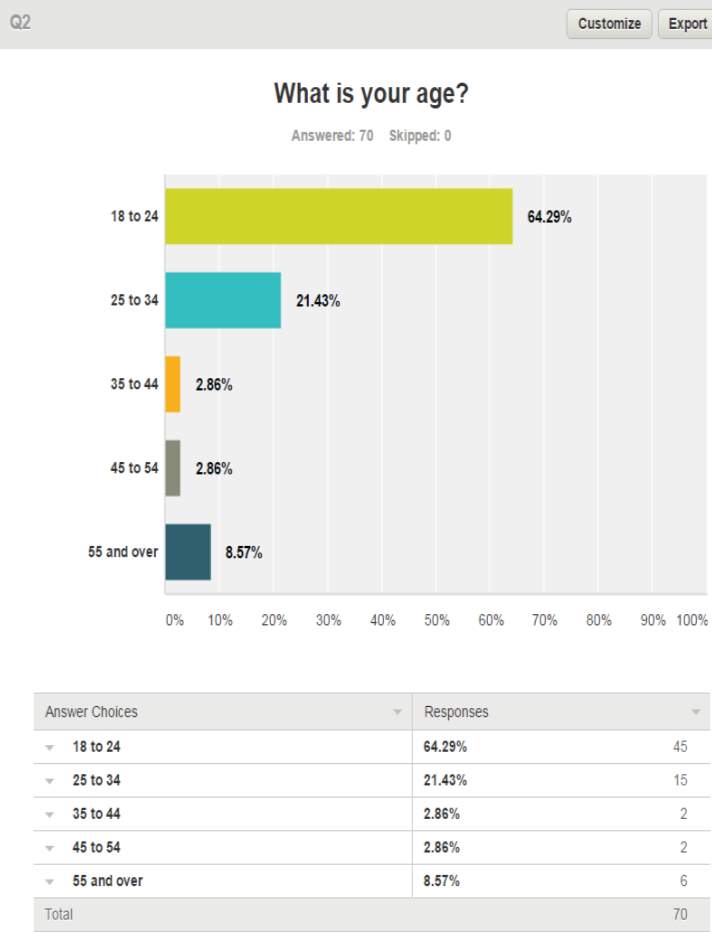

Respondents were then asked to state which age group they were in. However in the age categories of respondents, there was a large proportion of 18-24 year olds, 64.29% of the sample population, which may have compromised the representativeness of the sample. It was also noted that the 35-44, 45-54 and 55 and over categories were underrepresented in this survey. These three categories combined made up just 14.5% of the survey population. See Figure 2.0 for a breakdown of the age of respondents.

Figure 2.0

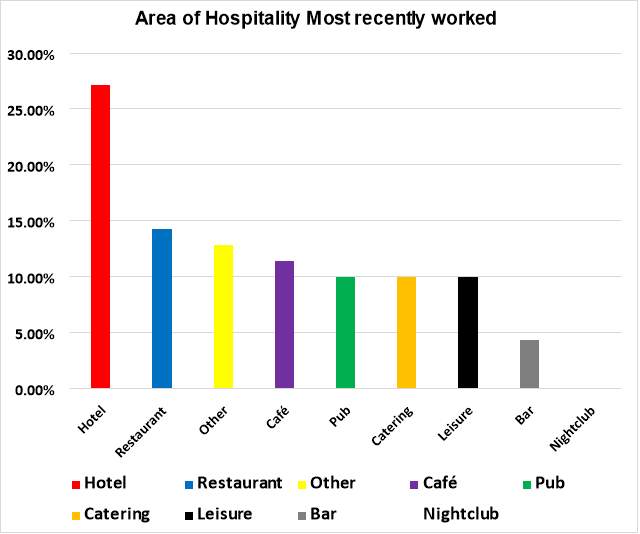

Respondents were asked to state the area of hospitality most recently worked in. Most respondents cited Hotels as their most recent area at 27%. Six of the nine categories were evenly spread as 10-15% identifying with them. One category offered was ‘Other’, perhaps a limitation as it can be difficult to define what type of organisation would fall into this category. It may be difficult for the researcher to break down the components of this category. Referring to the literature, Michel (2014) stated that waiting staff had a turnover rate even higher than the industry average so to have ex-restaurant employees represented may give further plausibility to the sample population.

Figure 3.0

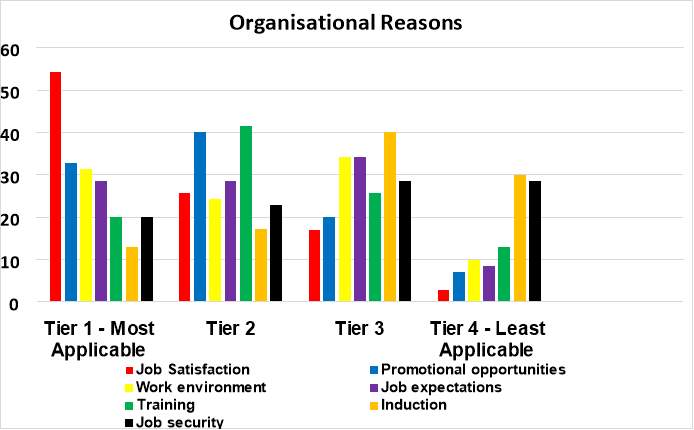

4.2 Organisational reasons for leaving the job

Respondents were asked to rank ‘organisational’ reasons for leaving the job in order of how they applied to them most to least; these were factors where the organisation had some form of control over. The literature review identified several themes which this question was formulated around. As there were so many rankings between seven themes the researcher combined percentages of the top two, third and fourth, fifth and sixth responses into three tiers to create an aggregate score to clarify the results and left the least applicable to tier 4. Tier 1 was the highest ranked reasons, tier 2 was the second most applicable reasons, tier 3 was the lesser ranked reasons. Tier 4, the least applicable reasons to leave was not combined so the results for this category are based on percentage of respondents.

In this section respondents ranked Job satisfaction as the most important reason as most felt that it got the highest aggregate score at 54.28 in the most applicable reasons for leaving, taking into account the top and second ranked reasons for leaving. A poor induction was cited by respondents as the least applicable reason to leave as 40% of respondents ranked it as their least important reason to leave.

Figure 4.0

Referring to the literature, Job satisfaction according to the annual Job Exodus survey (2015) found that job satisfaction was the number one reason to change jobs therefore it is aligned with the primary findings as they suggest this was the most important organisational reason. However Ertas (2015, p418) Barrows (1990, p25) and Mullins (2013, p244) did not explicitly state whether job satisfaction was the most likely reason for employees to leave an organisation. Regarding a poor induction (Riley, 1996, p142) referred to it as an ‘endemic in the hospitality industry’ so these findings may contradict this source as respondents did not regard it as one of the more important reasons. Though if research was conducted on a larger scale it may have ranked higher.

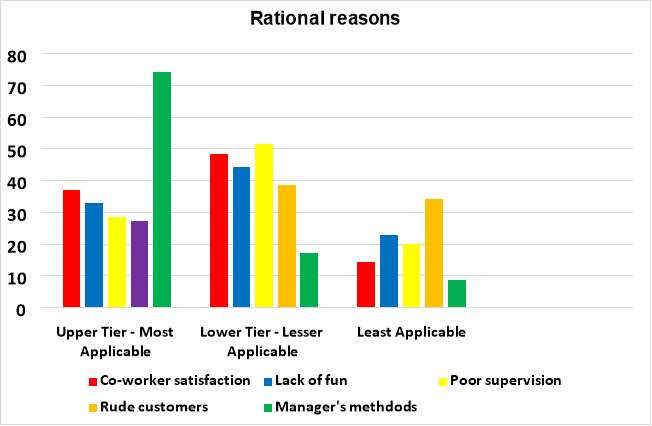

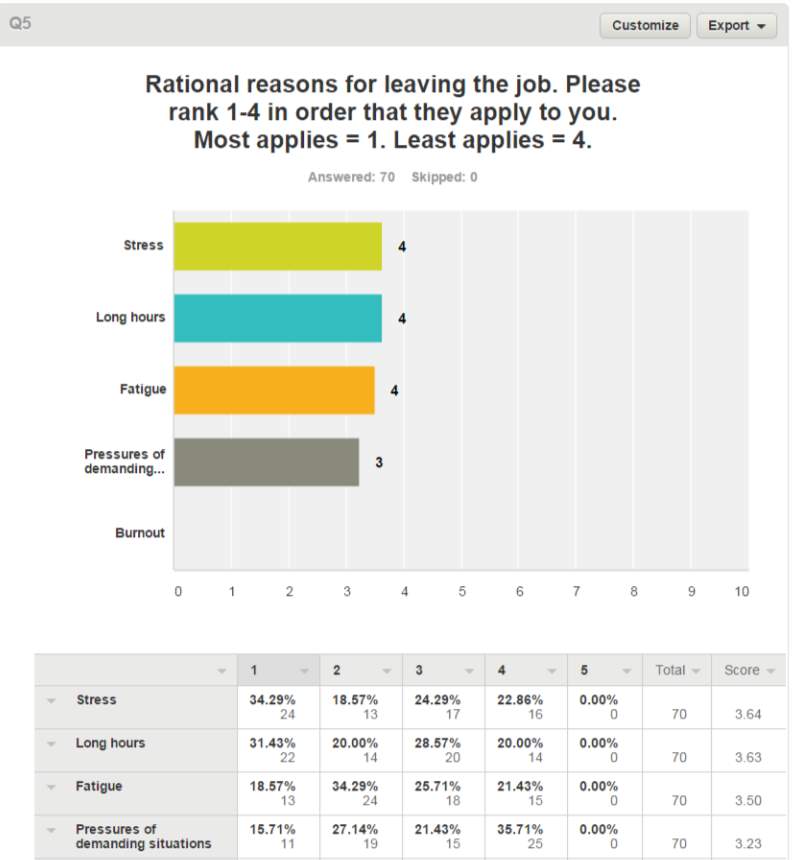

4.3 Rational reasons for leaving job

Respondents were asked to rank rational reasons for leaving the job as they were reasons that were logical and subjective to respondent’s own situations. These responses were grouped into three tiers in order of appliance: upper, lower and least applicable with an aggregated score allocated.

Respondents were asked to rank rational reasons for leaving the job as they were reasons that were logical and subjective to respondent’s own situations. These responses were grouped into three tiers in order of appliance: upper, lower and least applicable with an aggregated score allocated.

Figure 5.0

Of these reasons, a manager’s methods were cited as the number one reason to leave in the upper tier with a score of 74.29. In the lower tier, a prominent lesser reason to leave was poor supervision had the highest score of 51.43. Respondents felt that rude customers, with a score of 34.29 were the least applicable reason.

Interacting with the literature, a manager’s methods (Riley, 1996, p142) only suggested that, perceived unfair treatment could prompt an employee to leave but did not imply that it was a common reason for leaving, whereas these findings suggest that it is likely to trigger turnover intention. Poor supervision (Hinkin and Tracey, 2000, p21) did state that it was a primary reason for turnover so as it is in the second most popular reason in this category is to be expected. Rude customers (Han, Bonn & Cho, 2016, p103) were described as having a positive correlation to turnover intention but no indication to the emphasis employees place on this reason for leaving above others.

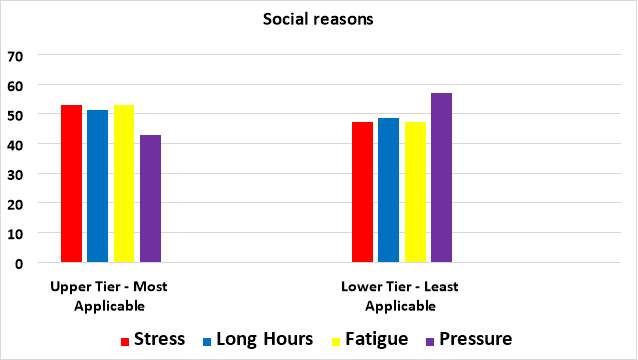

4.4 Social reasons for leaving job

Further themes in the literature were found and based on this respondents were next asked to rank social reasons for leaving the job, this question focused on the interpersonal criteria for leaving. Responses were grouped into an upper tier regarding most applicable rankings and lower tier based on the lesser applicable reasons and allocated aggregate scores.

Figure 6.0

It is apparent based on these findings that there is little to distinguish between these four themes. Stress and fatigue had both been identified by Scanlan & Still (2013, p317) but did not state whether which was a bigger influence. Long hours and pressure were both identified by Boella & Goss-Turner (2013, p167) but likewise did little to indicate which of the two reasons were most likely to make employees leave.

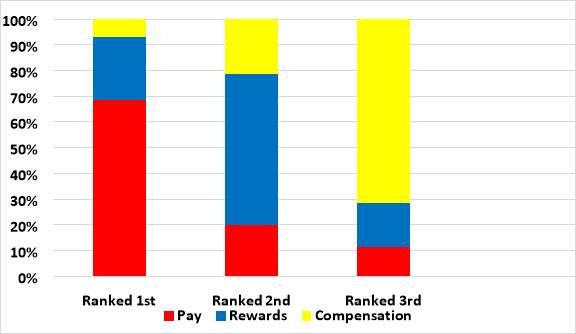

4.5 Financial reasons for leaving job

The literature review established extrinsic influences such as pay and rewards. Respondents were asked to rank reasons in the ‘financial’ category. Poor pay was significantly ranked as the top reason for leaving as 68.57% of respondents placed it first. A lack of additional financial rewards was the top ranked second reason to leave as over half of respondents, 58.57% ranked it as their second most applicable reason. Respondents felt strongly that a lack of compensation packages available was their least applicable reason to leave as 71.43% ranked it as their top third reason.

Figure 7.0

These findings suggest that employees feel strongly about pay and it implies that if pay requirements are not met then they are very likely to leave. As financial compensation was the top 3rd ranked reason it implies that it may not be crucial for hospitality organisations to have this in place in order to retain staff.

4.6 The ‘7 hidden reasons’ for leaving a job

Based on the ‘7 hidden reasons’ for leaving the job, respondents were asked to choose which one most applied to them, Branham (2005). ‘Feeling devalued and unrecognised’ was the most chosen factor as 30% of respondents felt this to be the reason that most applied. In second place was ‘stress from overwork and a work life imbalance’ at 21.43%. A lack of ‘growth and advancement opportunities’ were the third most popular as 20% chose this option. Of the hidden reasons, respondents felt that ‘little coaching and feedback’ would not influence them to leave as only 2.86% chose this option. There was also a ‘none of these applied’ option in this question yet only one respondent chose this, which may imply that these seven hidden reasons are justified.

Figure 8.0

Considering the literature, the ‘7 hidden reasons for leaving’ (Branham, 2005) there was nothing to suggest in the source that any one reason would rank above another. Therefore asking respondents to choose the reason that most applied is a way to give a general consensus, though a limitation is that a different sample may have suggested a different top applicable reason of the seven, however this outcome can be a starting point for further research.

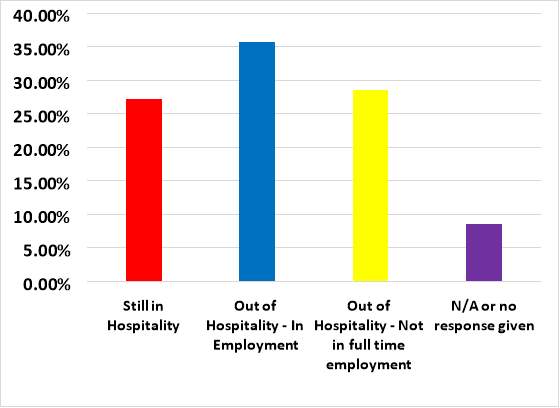

4.7 Respondents’ current situation

Finally respondents were asked to state their current line of work, as to gauge their current situation. This was an open comment box in order to gather as much meaningful data as possible. Frequently cited words were ‘student’, ‘unemployed’, ‘retired’ or ‘in full time education’. This enabled the researcher to build up a picture of respondents’ situations so based on these responses, four different categories were devised; first was those who still worked in the hospitality industry since leaving their most recent position, second was no longer in the hospitality industry but still in some form of employment, there was also those who had left the hospitality industry and were not in full time employment and finally there was an allowance for non-applicable statements and instances where no response had been given.

Figure 9.0

27% identified as still in the hospitality industry, a significant amount, though this section of the survey population may have had negative experiences, this was not enough to deter them from the hospitality industry completely. Of all responses over 35% identified as being out of the industry but in employment which was the greatest of the four categories. Though they were not in the industry at that moment in time there was no indication as to whether they would ever return to the hospitality industry. 28% of respondents identified as being out of full time employment and out of the hospitality industry. The high declaration of full time student status and the predominantly 18-24 age range of respondents arguably factored into these type of responses. Non applicable or non-disclosed statuses accounted for 8% of comments. In the literature review Hornsey & Dann (1984, p15) and Riley (1996, p142) both considered the transient hospitality workforce so there may be a case that these responses reflected that of a sample population that was transient in nature.

Respondents’ current situations in this research may reflect the type of sample population used. As it was generally a young population this may have impacted the results. If a sample that reflected wider age categories had been attained then the outcome may have been different. These findings were arguably to be anticipated by a young sample population. There was a risk of bias as respondents were known to the employer, particularly those who identified as a student. Ultimately as 27% identified as still being in hospitality it suggests despite any negative experience an individual is still willing to work in the industry.

5.0 Conclusions & Recommendations

5.1 Conclusion

Based on themes identified in the Literature Review it is apparent the themes identified were applicable to the sample population. The most common top ranked reasons in the different groups were; job satisfaction, manager’s methods, pay and feeling devalued and recognised.

The original research objectives were:

- To find and investigate common reasons for voluntary turnover in the hospitality industry

- To evaluate the perceived importance of key reasons for voluntary turnover.

It can be worth considering how these initial objectives have been met over the course of the research. Common reasons for voluntary turnover have been identified in the literature so this objective has been achieved. The importance of these reasons for turnover were evaluated via primary research, though the research methods had limitations this initial objective has been achieved as respondents assessed various reasons as to why they voluntarily left hospitality organisations. The key issue however is whether these objectives have been answered indefinitely. In the literature review and in the findings and analysis sections it was difficult to pin down the preferred reasons for leaving yet in some cases like pay and a manager’s methods respondents felt strongly about them.

There were some limitations of this research. For instance the lack of academic writing available in the public domain made it difficult to support themes identified with multiple sources. It is also clear to see some discrepancy surrounding the profile of respondents post the data collection stage as there was a large disparity between the age profiles of respondents, as the majority were in the 18 – 24 age group and possibly compromised the accuracy of results, though this was perhaps to be anticipated as it reflected a population that the researcher had access to. As most respondents identified as most recently working in a hotel this may have implication on the results because though it is a type hospitality business, experiences may differ greatly to restaurants for example so this should be taken into consideration. Another perceived limitation was that the grouping of reasons for leaving into categories may have hindered clarity of results, especially as they may have been grouped incorrectly. A key limitation of this project was that there were certain questions where no clear top ranked reason could be identified meaning that it was difficult for the researcher to draw a conclusion from.

5.2 Recommendations

A suggestion for future research may be to see how respondents match these reasons for leaving a hospitality job against each other as they could not be directly compared to one another in this project. The biggest crux of this project is finding the definitive, dominant reason for leaving a hospitality job and the ranking system in this project perhaps did not provide the means to decide this, as respondents chose the ‘most to least applicable reasons’ therefore taking into account some of the reasons offered may be completely irrelevant.

Based on this, it is apparent the reasons for leaving a hospitality business voluntarily are subjective as each respondents’ situation differs. The researcher may have been able to decipher richer and meaningful data and qualitative data with strong opinions could have proved to be decisive in getting a better reflection what ex-employees’ attitudes towards their reasons for leaving a hospitality business are.

Based on findings in this project there may be a requirement to research this issue further. It could be argued that there was a lack of clarity as to which reason for voluntary turnover was the most dominant reason in several cases. There is perhaps a need for multiple research methods needed to tackle this subject on a greater scale in order for hospitality managers to tackle high staff turnover. Though interviews were disregarded in the Methodology sectionupon collecting the data, they may have been used to support findings. The research may recognise the value of method triangulation whereby multiple methods of data collection and analysis can be combined. Sekaran & Bougie (2009, p385) argue that a researcher ‘can be more confident in a result if the use of different methods or sources leads to the same results’. The use of this technique would be a recommendation towards having a greater clarity over the voluntary turnover reasons and producing and interpreting data that is reliable and valid.

One possible approach may be to formulate interview questions on the basis of these findings. As it is difficult to ascertain the most important reason for leaving a hospitality job and scarce literature that gives closure to what employees decide is the likely determinant of leaving, a starting point may be to ask interview questions tailored to the popular themes which were pay, job satisfaction and managers.

Looking at the survey results found in the Presentation and analysis of data section the three most prominent reasons for leaving an organisation were a manager’s methods, pay and job satisfaction respectively. Therefore based on these findings it would appear that these three reasons could be cited as the most pressing issues to address if staff retention is to be improved. Without disregarding other reasons to leave, hospitality managers may need to prioritise these issues over others in order to retain more staff and reduce voluntary turnover as respondents in this project felt strongest about these areas most of all.

6.0 Bibliography

- Barrows, C. W. (1990). Employee Turnover: Implications for Hotel Managers. Hospitality Review, 8(1), 24 – 31.

- Baum, T. (2008). Implications of hospitality and tourism labour markets for talent management strategies. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20(7). 720 – 729

- Bell, J. (2010). Doing Your Research Project: A guide for First-Time Researchers in Education and Social Science (4th ed.) Buckingham: OU Press. P147.

- Boella, M, J & Goss-Turner, S. (2013). Human resource management in the hospitality industry: a guide to best practice (9th ed). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Branham, L. (2005). The 7 Hidden Reasons Employees Leave. New York: Anacom.

- British Hospitality Association. (2015). A report prepared by Oxford Economics for the British Hospitality Association. Retrieved from the BHA website: http://www.bha.org.uk/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Economic-contribution-of-the-UK-hospitality-industry.pdf

- Bryman, A & Bell, E. (2011). Business Research Methods (3rd ed). Oxford: Oxford University Press. P263.

- Can’t get no satisfaction: UK workers among the most dissatisfied in Europe. (2012). Retrieved from the ACAS website: http://www.acas.org.uk/index.aspx?articleid=3924

- Chan, S.H & Kuok, O. M. (2011). A study of Human Resources Recruitment, Selection and Retention Issues in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry in Macau. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 10(4), 421-441

- Cobb, A. (n.d.). Using Talent Management to reduce Employee Turnover. Retrieved from: http://hotelexecutive.com/newswire/39999/using-talent-management-to-reduce-employee-turnover

- Cooper, D. R & Schindler, P. S. (2013). Business Research Methods (12th ed.). New York: McGraw – Hill. P147.

- Davidson, C.G, Timo, N & Wang, Y. (2010). How much does labour turnover cost? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(4), 451 – 466.

- Deery, M & Jago, L (2015). Revisiting talent management, work-life balance and retention strategies. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(3), 453 – 472.

- Dhanani, N. (2014). 6 ways to reduce employee turnover. Retrieved from: http://hotelnewsnow.com/Article/13474/6-ways-to-reduce-employee-turnover

- Ertas, N. (2015).Turnover intentions and work motivations of Millennial Employees in Federal Service. Public Personnel Management, 44(3), 401- 423.

- Ford, R.C, Sturman, M.C & Heaton, C.P. (2012). Managing Quality Service in Hospitality. New York: Delmar. P188

- Gaskell, A. (2014). How High Employee Turnover Harms Your Performance. Retrieved from: https://www.salesforce.com/blog/2014/11/how-high-employee-turnover-harms-your-performance.html

- Ghauri, P & Gronhaug, K (2002). Research Methods in Business Studies (2nd ed). Pearson Education: Harlow. P102.

- Glenn, J.C. (2010) Handbook of Research Methods. Delhi: Oxford Book Company. P144.

- Gustaffson, C.M. (2002). Employee turnover; a study of private clubs in the USA, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 14(3), 106 -113.

- Hayes, D. K. & Ninemeier, J. D. (2009). Human Resources Management in the Hospitality Industry. New Jersey: Wiley. P265.

- Han, S.J, Bonn, M. A & Cho, M. (2016). The relationship between customer incivility, restaurant frontline service employee burnout and turnover intention. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 52(1), 97-106.

- Hinkin, T. R. & Tracey, J. B. (2000). Cost of turnover: Putting a price on the learning curve. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 41(3), 14-21.

- Holtom, B.C, Mitchell, T.R, Lee, T.W & Inderrieden, E.J. (2005). Shocks as Causes of Turnover: What they are and how organisations can manage them. Human Resource Management, 44(3), 337-352.

- Horn, R. (2009). Research & Writing Dissertations. London: CIPD. P135

- Hornsey, T & Dann, D. (1984). Manpower Management in the Hotel and Catering Industry. Worcester: Batsford. P15

- Hwee-Ang, S. (2014). Research Design for Business & Management. London: Sage. P11

- Iverson, R.D & Deery, M. (1997). Turnover culture in the hospitality industry. Human Resource Management Journal, 7(4), 71 – 82.

- Johnston, N & Spinks, W. (2013). Organisational Climate and Employee Turnover Intention within a Franchise System. Journal of New Business Ideas and Trends, 11(1), 20-41.

- Koslowsky, M & Krausz, M (2002). Voluntary Employee Withdrawal and Inattendence: A current perspective. New York: Plenum Publishers. P54

- Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research Methodology Methods and Techniques (2nd ed). New Delhi: New Age International Publishers: P3

- Lashley, C. (2001). Costing staff turnover in hospitality organisations. Journal of Services Research, 1(2). 3-22

- Lean, G. (2015). Briefing: High staff turnover is costly for hospitality businesses. Retrieved from: http://hospitalitypeoplegroup.com/2015/06/04/staff-turnover/

- Lundberg, D.E & Armatas, J.P. (1974). The Management of People in Hotels, Restaurants, and Clubs (3rd ed.). Iowa: W.C Brown. P39

- Maylor, H & Blackmon, K. (2005). Researching Business & Management. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. P 185

- Michel, M. (2014). Recruitment strategy needed change needed to tackle £2.7m turnover cost. Retrieved from: http://www.bighospitality.co.uk/Trends-Reports/Recruitment-strategy-change-needed-to-tackle-2.7m-turnover-cost.

- Mohsin, A, Lengler, J & Aguzzoli, R. (2015). Staff turnover in hotels: Explaining the quadratic and linear relationships. Tourism Management, 51, 35 – 48.

- Mullins, L.J. (2013). Management & Organisational Behaviour (10th ed.). London: Pearson. 243 – 244.

- Mullins, L.J & Dossor, P. (2013). Hospitality Management and **Organisational Behaviour (5th ed.). Harlow: Pearson. P3

- Murphy, N. (2015). Labour turnover rates: 2015 survey. Retrieved from: http://www.xperthr.co.uk/survey-analysis/labour-turnover-rates-2015-survey/156198/?keywords=labour+turnover+rates+2014.

- Pizam, A. R & Thornburg, S.W. (2000). Absenteeism and voluntary turnover in Central Florida hotels: a pilot study. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 19(2), 211 -217.

- People 1st. (2014). Hospitality and Tourism – Creating a sustainable workforce. Retrieved from the people1st website: http://www.people1st.co.uk/getattachment/Research-policy/Research-reports/Monthly-insights-reports/Reworked-Hospitality-Report-v-4.pdf.aspx.

- Quinlan, C. (2011). Business Research Methods. Andover: South-Western Cengage Learning. P337

- Riley, M. (1996). Human Resource Management In The Hospitality & Tourism Industry (2nd ed). Oxford: Butterworth – Heinemann. P142

- Roberts, J. (1995). Human Resource Practice in the Hospitality Industry. London: Hodder & Stroughton. P82.

- Robinson, R, N.S, Kralj, A, Solnet, D.J, Goh, E & Callan, V. (2014). Thinking job embeddedness not turnover: Towards a better understanding of frontline hotel worker retention, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 101 -109.

- Saunders, M & Lewis, P. (2012). Doing Research in Business & Management. Harlow: Pearson. P128

- Saunders, M, Lewis, P & Thornhill, A. (2009). Research methods for business students (5th ed.) Harlow: Pearson Education. P184

- Scanlan, J. N & Still, M. (2013). Job satisfaction, burnout and turnover intention in occupational therapists working in mental health. Australian occupational Therapy Journal, 60, 310 – 318.

- Schyns, B, Torka, N & Gossling, T. (2007). Turnover intention and preparedness for change: Exploring leader‐member exchange and occupational self‐efficacy as antecedents of two employability predictors. Career Development International, 12(7). 660 – 679

- Sekaran, U & Bougie, R. (2009). Research Methods for Business (5th ed.) Chichester: Wiley.

- Tews, M.J, Michel, J.W & Stafford, K. (2013). Does Fun Pay? The impact of workplace fun on Employee Turnover and Performance. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(4). 370 – 382.

- Walker, J.R & Miller, J.E (2012). Supervision in the Hospitality Industry. (7th ed.) New Jersey: Wiley. P354

- Wilson, J. (2010). Essentials of Business Research. London: Sage. P88

- 60 percent of UK workers not happy in their jobs. (2015). Retrieved from the investorsinpeople website: https://www.investorsinpeople.com//press/60-cent-uk-workers-not-happy-their-jobs

7.0 Appendices

7.1 Ethics Approval Form – Students

This form should be completed by the student and passed to the supervisor prior to a review of the possible ethical implications of the proposed dissertation or project.

No primary data collection can be undertaken before the supervisor has approved the plan.

If, following review of this form, amendments to the proposals are agreed to be necessary, the student should provide the supervisor with an amended version for endorsement.

The final signed and dated version of this form must be handed in with the dissertation.

The form MUST be signed and dated by both the student AND the supervisor.

If the dissertation is submitted without a fully completed, signed and dated ethics form it will

be deemed to be a fail. Second attempt assessment may be permitted by the Board of Examiners.

- What are the objectives of the dissertation / research project?

To find out the reasons for high staff turnover in hospitality and see which are the biggest influences

- Does the research involve NHS patients, resources or staff? YES / (NO) (please circle).

If YES, it is likely that full ethical review must be obtained from the NHS process before the research can start.

- Does the research involve MoD staff? YES / (NO) (please circle).

If YES, then ethical review may need to be undertaken by MoD REC. Please discuss your proposal with your Supervisor and/or Course Leader and, if necessary, include a copy of your MoD REC application for quality review.

- Do you intend to collect primary data from human subjects or data that are identifiable with individuals? (This includes, for example, questionnaires and interviews.) (YES) / NO (please circle)

If you do not intend to collect such primary data then please go to question 15.

If you do intend to collect such primary data then please respond to ALL the questions 5 through 14. If you feel a question does not apply then please respond with n/a (for not applicable).

- How will the primary data contribute to the objectives of the dissertation / research project?

Primary data based on secondary data in the literature review will enable the researcher to get a bigger picture of what the overall situation of staff turnover is really like

- What is/are the survey population(s)?

Ex-Employees of hospitality

- How big is the sample for each of the survey populations and how was this sample arrived at?

1 sample population (50 – 100 respondents)

- How will respondents be selected and recruited?

The researcher will identify ex-employees of hospitality organisations and ask them to participate in the questionnaire

- What steps are proposed to ensure that the requirements of informed consent will be met for those taking part in the research? If an Information Sheet for participants is to be used, please attach it to this form. If not, please explain how you will be able to demonstrate that informed consent has been gained from participants.

The researcher will directly approach respondents and by completing the questionnaire, respondents will give their consent to participate

- How will data be collected from each of the sample groups?

Via the use of a questionnaire on ‘surveymonkey.com’

- How will data be stored and what will happen to the data at the end of the research?

Data will be stored on ‘surveymonkey.com’ website and can be deleted if required after research has ceased

- What measures will be taken to prevent unauthorised persons gaining access to the data, and especially to data that may be attributed to identifiable individuals?

The survey is password protected

- What steps are proposed to safeguard the anonymity of the respondents?

Respondents not obliged to declare identity or organisations

Open answer fields have limited characters and are not validated

- Are there any risks (physical or other, including reputational) to respondents that may result from taking part in this research? YES / (NO) (please circle).

If YES, please specify and state what measures are proposed to deal with these risks.

- Are there any risks (physical or other, including reputational) to the researcher or to the University that may result from conducting this research? YES / (NO) (please circle).

If YES, please specify and state what measures are proposed to manage these risks.[1]

- Will any data be obtained from a company or other organisation? YES / (NO) (please circle) For example, information provided by an employer or its employees.

If NO, then please go to question 19.

- What steps are proposed to ensure that the requirements of informed consent will be met for that organisation? How will confidentiality be assured for the organisation?

- Does the organisation have its own ethics procedure relating to the research you intend to carry out? YES / NO (please circle).

If YES, the University will require written evidence from the organisation that they have approved the research.

- Will the proposed research involve any of the following (please put a √ next to ‘yes’ or ‘no’; consult your supervisor if you are unsure):

| • | Vulnerable groups (e.g. children)? | YES | NO | / | ||

| • | Particularly sensitive topics? | YES | NO | / | ||

| • | Access to respondents via ‘gatekeepers’? | YES | NO | / | ||

| • | Use of deception? | YES | NO | / | ||

| • | Access to confidential personal data? | YES | NO | / | ||

| • | Psychological stress, anxiety etc? | YES | NO | / | ||

| • | Intrusive interventions? | YES | NO | / |

If answers to any of the above are “YES”, how will the associated risks be minimised?

- Are there any other ethical issues that may arise from the proposed research?

NO

7.2 Questionnaire

7.2 Questionnaire

NB – Burnout was removed from survey as pilot sample felt it was too similar to fatigue. Respondents never saw this question option in survey.

NB – Burnout was removed from survey as pilot sample felt it was too similar to fatigue. Respondents never saw this question option in survey.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Hospitality"

Hospitality refers to the hosting and entertainment of guests or visitors. The Hospitality sector includes businesses such as hotels, B&Bs;, restaurants, cafes, bars, and other businesses relating to travel, tourism, and entertainment.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: