Brand Building Process of a Luxury Fashion Brand: Literature Review

Info: 6134 words (25 pages) Example Literature Review

Published: 22nd Feb 2025

Other sections of this dissertation:

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Methodology

2. Literature Review

2.1 Understanding brands and branding

According to the American Marketing Association (AMA), a “brand is a customer experience represented by a collection of images and ideas; often, it refers to a symbol such as a name, logo, slogan, and design scheme. Brand recognition and other reactions are created by the accumulation of experiences with the specific product or service, both directly relating to its use, and through the influence of advertising, design, and media commentary. A brand often includes an explicit logo, fonts, color schemes, symbols, sound which may be developed to represent implicit values, ideas, and even personality” (American Marketing Association, 2018).

Branding helps companies to differentiate their offerings from competition. Brands are usually supported by logos (Jobber & Ellis-Chadwick, 2016). Branding helps develop an “individual identity”, thereby permitting consumers to “develop associations” with brand and in turn ease the decision regarding purchase (Chernatony, 1991).

Branding has an effect on the perceptions (Jobber & Ellis-Chadwick, 2016). Customers often cannot distinguish between brands within each product category in a blind product test. They cannot identify what they consider to be their most preferred brand. For instance, the Pepsi Challenge made use of blind tests and taste tests where the brand identities were hidden, in order to determine the preferred brand. Although more people has bought Coca-Cola, the taste of Pepsi was most preferred when blindfolded (Jobber & Ellis-Chadwick, 2016).

Branding can be defined as “a name, term, sign, symbol, design or a combination of these, which is used to identify the goods or services of one seller or group of sellers and to differentiate them from those of competitors” (Kotler, et al., 1999, p. 571).

2.2 Luxury Fashion Brand

Gutsatz (1996) defines luxury from a consumer perspective and suggests that luxury can be represented from two perspectives. The first representation is material that it includes the brand, its history, identity, its uniqueness and the product. The second representation is “psychological”, it includes representations that are influenced by ones social environment and brand values.

Jackson & Haid (2002) reinforces this perspective and defines luxury from a product/brand perspective and argues that luxury fashion brand is characterized by premium prices, exclusivity, status and image, and all these characteristics make luxury brand desirable for reasons apart from just function.

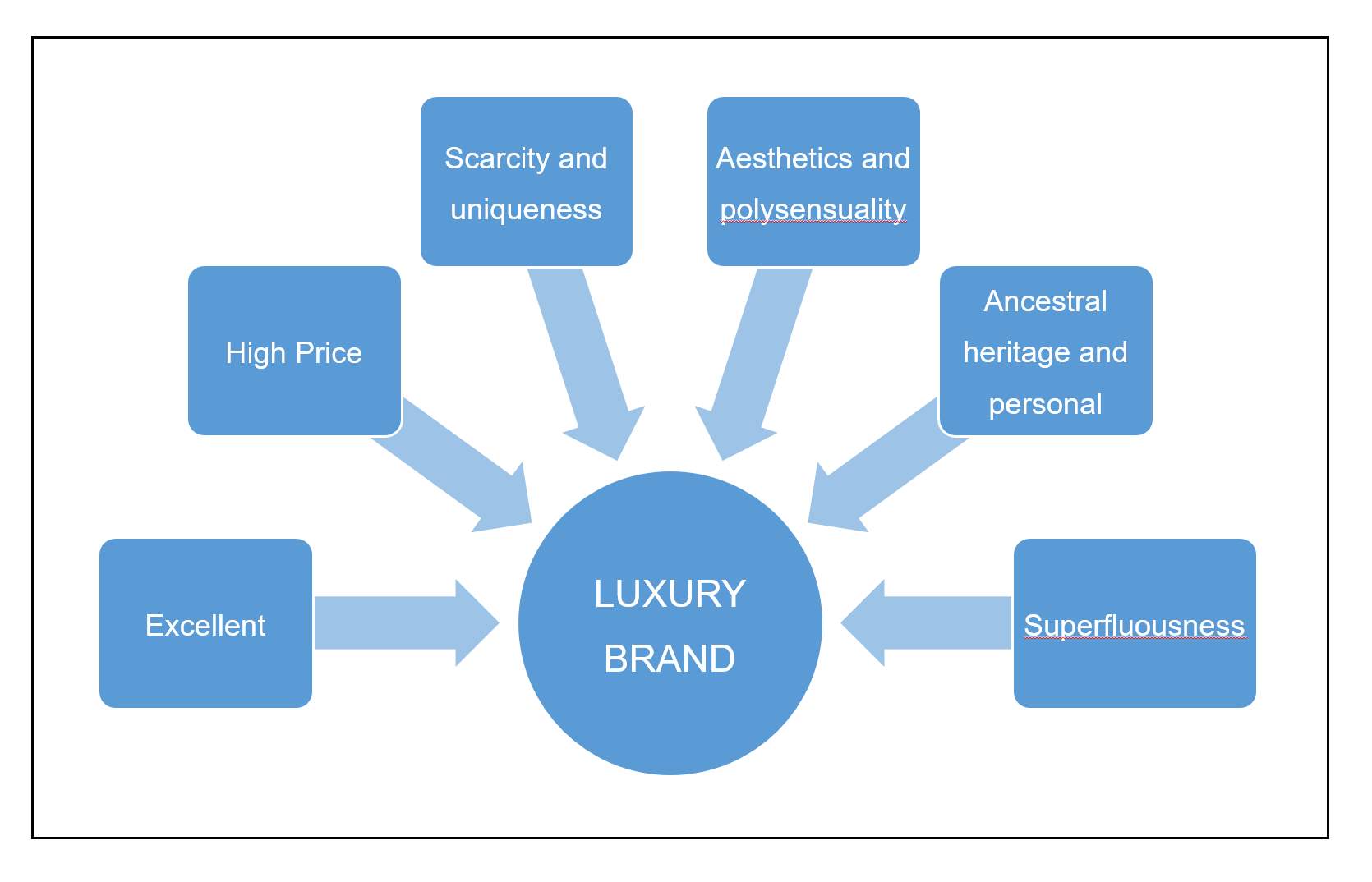

The following figure represents the six elements of luxury (Dubois, et al., 2001).

Figure 1: Six Elements of Luxury

Elements like the “iconic product designs” or the creator’s personality, the brand name , their location and the “visual symbols” associated with the brands and its history, contribute to making a luxury fashion brand (Hines & Bruce, 2007, p. 131). For example, Chanel is “intertwined with the personality” and lifestyle of Coco Chanel, the creator. Thanks to the image of the creator, the brand value of Chanel is upheld. Ever since its inception, the logo of Chanel has not been changed. This feature is also found with other luxury brands. It is typical for luxury brands to invest in “premier locations” and develop flagship stores. Luxury retail stores are clustered in specific streets in capital cities, for example Fifth Avenue in New York and Rue du Faubourg St Honoré in Paris (Hines & Bruce, 2007, p. 132) and Burberry opening a flagship store on New Bond Street in London in an attempt to reposition itself as a “credible high fashion brand” (M.Moore & Birtwistle, 2004). Craftsmanship, history and the heritage of the brand are “built into the luxury brand” (Nueno & Quelch, 1998).It is also stated that “a very important part of the process in creating aura is the stories that surround the company” (Björkman, 2002, p. 76). The symbols associated with the brands are memorable and recognizable at an international level (Dubois & Paternault, 1995).

The luxury fashion brands can be distinguished by the following elements (Kent, et al., 2000):

- Global recognition.

- Core competence and Critical mass.

- High quality products.

- Innovation.

- Immaculate store presentation.

- Powerful advertising.

- Excellent customer service.

Differentiating between luxury brands and premium brands: Luxury brand and premium brands are not the same (Kapferer & Bastien, 2009). They are different models of managing high end companies and brands. Luxury is not “more premium”. Due to the comparative nature of the premium brands, the price of such brands cannot rise beyond a limit. Any increase in the price of premium products must be justified. With respect to luxury brands, there are no restrictions on the price of such products, nor does anyone question the rise in its prices. Luxury is more of an art (Kapferer & Bastien, 2009).

Segmentation of the luxury sector

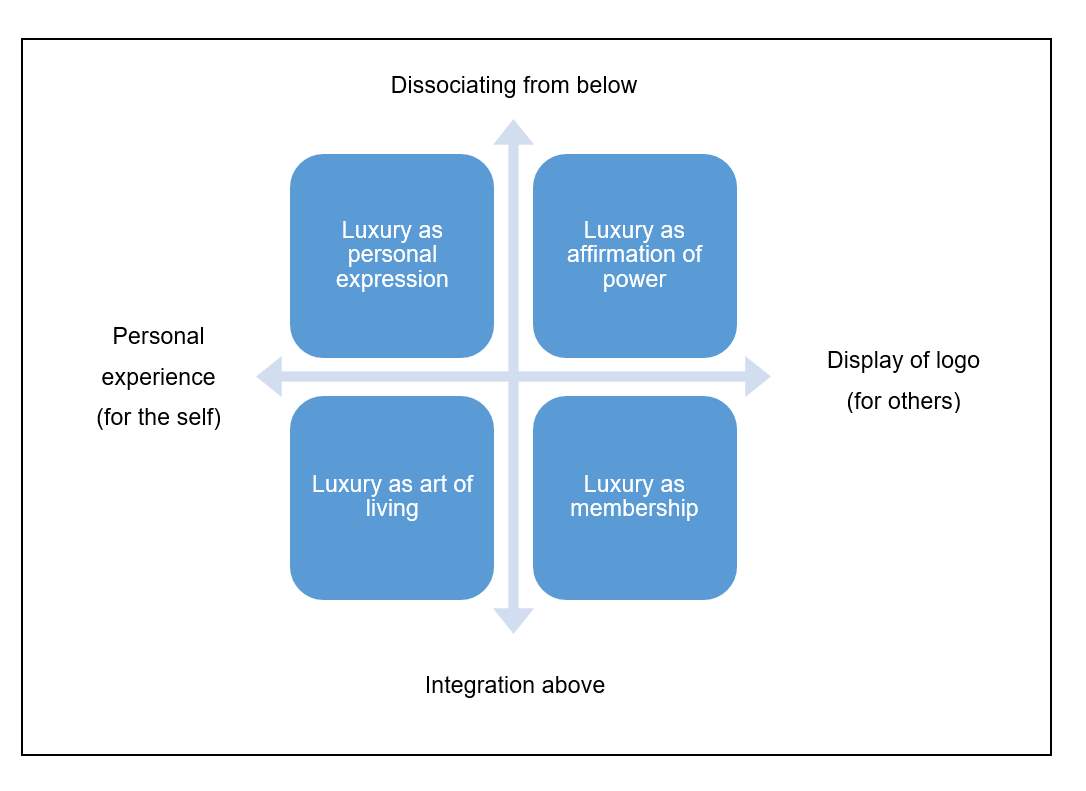

Figure 2: Functional perspective on luxury segmentation (Kapferer & Bastien, 2009)

The above figure gives a functional perspective of segmentation in the luxury sector. The horizontal axis denotes the desire to “signal superiority”, either through the display of “holy logos” or through product culture. The bottom half of the vertical axis represents the desire to be “integrated into an aspirational class”, whereas the other half of the vertical axis represents consumers that want “to stand out from the crowd” (Kapferer & Bastien, 2009).

Following are the four possible ways of segmenting the luxury sector (Kapferer & Bastien, 2009):

- Luxury as membership: Brands that fall within this quadrant, are considered to be “worldwide visas of distinction”. They pour respect upon their owner, as they are well known. The volume of sales and size of the brand is not a problem, so long as the prices are rising. These brands provide a guarantee of taste. The logo of such brands are considered to be a holy sign and must be visible.

- Luxury as affirmation of power: This category is a result of the growth and development of the former category. When a brand is adored by the “happy many”, the “happy few” consider it necessary to differentiate themselves, by choosing more flashy, visible and expensive brands. For example they will choose Dolce & Gabbana in place of Chanel or a Lamborghini in place of Ferrari. People with high need for power and recognition are attracted by these categories of brands.

- Luxury as personal expression: This category includes the start-ups, or “edgy brands” that provides differentiation to some extent. It includes brands that are usually found in multi brand, selective shops.

- Luxury as art of living: The brands forming a part of this quadrant, “promote a product culture” of selling excellence. For them there are only luxury products, no luxury brands.

2.3 Characteristics of Luxury Fashion Brand

Following are the characteristics of Luxury Fashion brand (Gorp, et al., 2012)

a) Clear Brand Identity: As per Fionda and Moore (2009) brand values, global marketing strategy, aspirational and emotional appeal, help defining a clear brand identity.

Products with a strong “aspirational appeal” are bought not only because of the fact they are crafted finely but also because of the “prestigious image” they generate. The brand value must make the brand stand “different and relevant” within the market. The company must make investments to develop the brand and guarantee its future (Gorp, et al., 2012).

b) Marketing communications: As per Fionda and Moore (2009), “powerful marketing communications” helps in creating identity and generating awareness and building the image of a luxury brand. It is necessary to communicate the rare quality and the beauty of the product (Gorp, et al., 2012). Celebrity endorsement, public relations, direct marketing, fashion shows, sponsorship are some of the means of communicating about a luxury brand (Fionda & Moore, 2009)

c) Product Integrity: Unlike a premium product, a luxury product does not aim to be flawless (Gorp, et al., 2012). Flaws are usually seen “as a guarantee of authenticity” and a “part of the charm” (Kapferer & Bastien, 2009). As per Keller (2009) the quality must exceed or meet the expectations of the consumer and in order to achieve it, the company “achieve flawless delivery of value”. As per Fionda and Moore (2009) use of best materials and excellent craftsmanship ensures good quality. Fashion companies have a portfolio of innovative, seasonal and traditional products (Fionda & Moore, 2009). Innovation is seen a key to remain “as a reference” in the market (Lewi & Lacoeuilhe, 2007). While the classical products highlight the “brand’s heritage”, the innovative products help in keeping the brand exciting and fresh (Fionda & Moore, 2009).

d) Brand Signature: Luxury brands can make recognisable products, styles and motifs (Sicard, 2010). Consistency must be maintained across all the products of the brand (Gorp, et al., 2012). As per Fionda and Moore (2009), iconic products are the centre of “luxury product offering”. High-profile fashion designers make the products appealing (Gorp, et al., 2012).

e) Premium Prices: Luxury products do not define expensive products (Dubois & Czellar, 2002). Strategic positioning of the brand is confirmed by price, making it an essential part of the brand (Lewi & Lacoeuilhe, 2007). The aspirational value should form a basis of the price of the luxury goods and not their costs (Sicard, 2010). As per Fionda and Moore (2009), high prices gives the brand a “luxury status and increases exclusivity”. Luxury brands give very few markdowns and discounts (Keller, 2009).

f) Exclusivity: Exclusivity and rarity can be considered as dimensions of luxury brand, which can be translated into exclusive ranges and limited editions (Fionda & Moore, 2009). Sicard (2010) added the relevance of “waiting list”. Chevalier and Mazzalovo (2012) highlighted the relevance of “non-availability”. The influence of rarity varies across different regions (Phau & Prendergast, 2000). For example Asian consumers are less likely to be influenced by rarity as compared to Western consumers (Phau & Prendergast, 2000).

There seems to be an overlap between the dimension of exclusivity and the dimension of product integrity. The sub-dimensions of product integrity are “innovation” and “seasonal products”, whereas the sub-dimensions of exclusivity are “exclusive ranges” and “limited editions”. Most luxury brands include “seasonal product” characterised by “exclusive ranges” and “limited editions” (Gorp, et al., 2012).

g) Heritage: The authenticity of a brand is furthered strengthened by a long history of the brand (Fionda & Moore, 2009). It creates a sense of nostalgia and adds credibility (Fionda & Moore, 2009). The history of the brand also adds to its competitive advantage (Urde, et al., 2007). Sicard (2010) considers this as “seniority”.

h) Environment and Service: Fionda and Moore (2009) highlights upon the importance of the superior service and store environment. “Flagship stores” showcases the experience and environment of the brand (Degoutte, 2007). Sicard (2010) emphasises on the role of manufacturing plants. It is very important to have control over the manufacturers, suppliers, distributors and licensees (Stankeviciute & Hoffmann, 2010). The use of different channels of distribution “reinforces the brand’s notoriety” (Lewi & Lacoeuilhe, 2007). Thus the choice of distribution channel is very crucial as it highlights the brand values(Gorp, et al., 2012). The “highly targeted market segments” and the requirement for prestige and exclusivity, makes retail distribution highly controlled and selective (Keller, 2009).

i) Culture: “Internal and external commitment” can be extended by investing in company culture, where factors in both the categories are going to support the brand. As the company requires “external commitment” from its vendors and partners, it is very important to make the right choice of licensees and manufacturers (Fionda & Moore, 2009).

2.4 Characteristics of Buyers of Luxury Products

As per (Scholz, 2014) there are two approaches to understanding buying behaviour of consumers, namely “personally oriented behaviour” and “socially oriented”. The desire to “impress” others drives “social oriented behaviour”, whereas “personally oriented behaviour” is driven internally and includes an “element of self-fulfilment” (Scholz, 2014). Cultural and psychological factors also affect buying behaviour. The social status and role are significant influencers of buying behaviour, as the social status is signalled by the purchase of luxury goods (Perreau, 2013).

Consumers like to show off and display status (Reis, 2015). They want to be recognised as part of a social group (Reis, 2015). “Luxury goods consumers think a lot about themselves” (Reis, 2015, p. 23). The needs of such consumers are “irrational” and “hedonistic”, where “rewarding oneself” and “self-recognition” also plays an important role (Kapferer & Bastien, 2009); (Chevalier & Mazzalovo, 2012); (Scholz, 2014); (Kapferer, 2012). Personality and values are shaped by family and friends, thereby driving consumer behaviour (Perreau, 2013).

Aspects like lifestyle, age and purchasing power comprise the personal factors (Reis, 2015). The purchasing behaviour of a twenty year old and a sixty year old are going to have “significant differences”, as factors like values, liking, and environment “evolve throughout the years” (Reis, 2015). Moreover it is quite natural for purchasing power to affect the “buying behaviour of a person” as “perspective on money may differ” (Perreau, 2013). Since affluent people can afford to pay for the “full price” of luxury goods, they do not have to worry about “money as much as the less wealthy” (Danziger, 2005).

Values, interests and opinions “influence buying behaviour”, making lifestyle an important component (Perreau, 2013). It will “drive the consumer to pursue goods” that fit within their lifestyle (Reis, 2015). Brand aims at developing a certain kind of personality and imagery that is parallel with the consumer’s traits and values, which helps is forming “consumer’s self-image” (Reis, 2015).

2.5 The Consumer decision making process in the luxury market

Okonkwo (2007, 62-64), explains the “consumer purchase-decision” making process in the luxury market, based on the theoretical framework of (Schiffman & Kanuk, 2004) Schiffmann and Kanuk (2004).

a) What consumers buy: “Luxury consumers” buy not only the products and services, but also a “complete package” of feelings, experience, “the service and the brand’s characteristics”.

b) When consumers buy: Luxury goods are purchased whenever there is an opportunity. These purchases donot come as a result of convenience, because they are desired constantly and “fall within the priority of luxury consumers”

c) Why consumers buy: More than “functional needs”, luxury goods are “‘cravings’ and sometimes ‘wishes’”, resulting in a continuous desire to own them. They are “objects of desire” and such desires continuous to exist.

d) Where consumers buy: Luxury products are usually bought in the “major fashion centre” where luxury fashion forms a prominent aspect of the consumer’s lifestyle.

e) How consumers buy: A major chunk of the luxury consumers like to shop in “physical stores” so as to benefit from the “complete product selection” and to enjoy the “luxury retail atmosphere”. However mobile and internet shopping are becoming increasingly popular in the luxury market.

f) How often consumers buy: The frequency of purchase of luxury goods depends on how financially and practically possible it is for them to buy one. Often the decision to purchase luxury goods is not a logical one. These goods are “objects of desire” and if possible consumers could purchase it on a continuous basis.

g) How often consumers use the products: Such “products are used frequently”, as they are a representative of the consumers lifestyles and personalities.

h) How consumers evaluate the products: The appreciation of luxury products extends beyond the “functional attributes to include abstract and symbolic benefits”, thereby making the post purchase evaluation a “non-representational occurrence”.

i) How consumers dispose off the products: Luxury goods are “rarely disposed of”, as they last for a lifetime. However the occurrence of “fast-fashion” phenomenon has made these goods disposable. This phenomenon highlights that the “design turnover of luxury products has become higher and the product lifecycles have become shorter” (Okonkwo, 2007, p. 64). As a result such items keep changing every few weeks. In a bid to keep up, consumers now tend to sell, their “‘used’ or ‘semi-used’ products for substantial amounts” so as to buy new ones.

j) How consumers decide on future purchases: “The decision for the future purchase of luxury goods has already been made. The future is now!” (Okonkwo, 2007, p. 64).

2.6 The Luxury fashion branding process

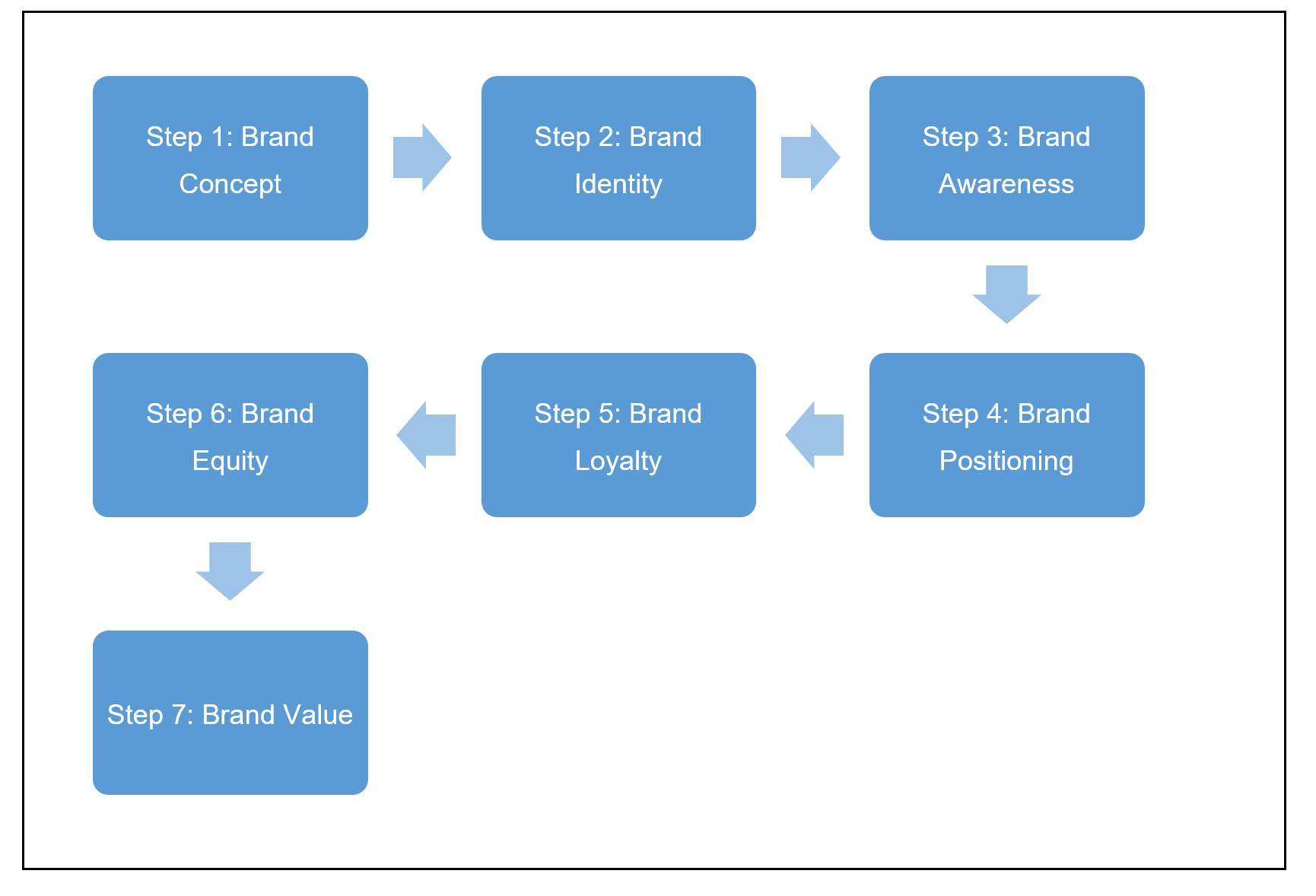

Figure 3: The Luxury fashion branding process (Okonkwo, 2007)

a) Brand Concept: The brand concept answers the question “What is your name”? (Okonkwo, 2007). Brand concepts can be defined as “unique, abstract meanings”, that are associated with the brands (Park, et al., 1991). These “unique, abstract meanings”, are derived from a certain combination of benefits, attributes and marketing efforts, that are used to convert these “benefits into higher-order concepts (Park, et al., 1986), (Park, et al., 1991). The brand concept which denotes the entire idea behind the birth of the brand, is reflected by brand name, brand history, country of origin, “its visual image”, brand color, brand logo, its language, shape and all of its offerings (Okonkwo, 2007).

Although brand concepts highlight both intangible aspects (how people think about the brand in an abstract manner) and tangible aspects (what the brand does actually) of the brand (Keller, 1993), (Keller, 2008), it has been observed that “establishing abstract brand concepts” on the basis of emotional and motivational meanings, helps is getting more “favorable consumer responses than focusing on superior functional attributes” (Hopewell, 2005), (Monga & John, 2010). Every luxury fashion brand has a “distinct brand concept”, differentiating it from the other except for one characteristic that is “prestige”. For example the Hermès logo showing the horse carriage indicates the brands humble beginnings in “horse saddlery production” and its tagline is often stated in French, indicating the country of origin and the foundation of the brand (Okonkwo, 2007). Thus there has been an increase in the importance of “abstract brand concepts imbued with” human like emotions, goals, values with the help of processes like “user imagery” (example: Mountain Dew “dudes”), “anthropomorphization” (example: California Raisins) and “personification” (Aaker, 1997), (Keller, 2008).

The brand name which is a striking aspect of “luxury fashion brand’s concept”, should “evoke all the associations that make up the brand” to the extent that consumer should be able to decipher the “brand’s connotation” from the name, without having to come in touch with its advertisement or products. The brand name chosen should have “elements of universality” as “luxury fashion brands are increasingly global in nature”. “Exotic brand names” that are associated with the origin and the history of the brand, or that reflect the name of the designers or founders, are much appreciated by the customers (Okonkwo, 2007).

b) Brand Identity: The brand identity answers the question: “Who are you”? (Okonkwo, 2007). Brand identity is “a unique set of brand associations implying a promise to customers and includes a core and extended identity”. Core identity forms the timeless, central essence of the brand, remaining constant as and when the brand goes into new products and markets. Product attributes, store ambience, services and performance of the product forms the core identity (Ghodeswar, 2008).

Brand identity comprises of two aspects, namely brand personality and brand image. Brand personality is the “the core personality traits and characteristics” selected for the brand and it denotes what the brand wants to be, how it views itself and how it wants itself to be viewed. However the brand image is how other people exposed to the brand see the brand. Brand image is developed based on the perception of the public as to how the “brand projects itself” (Okonkwo, 2007). Brand identity consists of the following components (Chernatony, 1999); (Harris & Chernatony, 2001):

- Brand vision and culture

- Brand personality

- Positioning

- Presentations

- Relationships

Brand identity needs to highlight upon “points of differentiation”, which helps providing competitive advantage (Ghodeswar, 2008). Brand identity is based on thorough knowledge of firm’s competitors, customers and business environment (Ghodeswar, 2008). Brand identity needs to highlight the “business strategy” and “firm’s willingness to invest in the programs” to ensure that the brand fulfills its promise (Aaker & Joachimsthaler, 2000). For the brand identity to be effective, it must “resonate with customers”, represent the capabilities of the organization and differentiate the brand (Aaker & Joachimsthaler, 2000).

As per (Fionda and Moore, 2009), a “well-known” brand identity is an important aspect of value proposition for luxury brands. Factors such innovation, craftsmanship, recognizable styles, premium pricing and exclusivity, helps build a strong brand identity in the luxury market (Chevalier & Mazzalovo, 2012). From a customer’s point of view, such characteristics provide various benefits such as sense of belonging, “identity affirmation” and social status (Hung, et al., 2011).

Luxury firms like Gucci Group NV, LVMH, Prada, Richemont Group, have spent hefty sums of money, to develop their corporate brand identities, which is a part of their branding strategies (Chevalier & Mazzalovo, 2012). Strong brand identity helps in developing a clear, relevant and well defined brand identity (So, et al., 2013). Suppliers of luxury brands use “high-status” brand names, to differentiate its brand identities (Choo, et al., 2012). The concept of brand identity is crucial to brand management for luxury goods. It sets the base for “long-term capitalization”. It provides a basis for respect for “brand’s specific itinerary” (Kapferer, 1997).

c) Brand awareness: This answers the question: ‘Who knows you? (Okonkwo, 2007). As per Keller (2008), brand awareness refers to whether the customers can recognize or recall a brand, or whether the brand is known to the customers. Brand awareness consists of “brand recall” and “brand recognition”. Brand recall refers to a situation where a consumer can recall the brand name exactly, when they come across a product category. Brand recognition refers to a situation where the customer can recognise the brand when there is a “brand cue” (Chi, et al., 2009). As the luxury goods offer unique and aspirational quality, they are distinguished from an “overcrowded fashion market”, thereby giving them a high level of brand awareness (Okonkwo, 2007). The most important element of brand awareness is the brand name (Davis, et al., 2008). As consumers usually buy well know and familiar products, brand awareness has an important role to play when it comes to purchase decisions (Macdonald & Sharp, 2000); (Keller, 1993).

Brands are “more likely to be included” into a consumer’s consideration set, if they are known to the consumers (Macdonald & Sharp, 2000); (Hoyer & Brown, 1990). Consumers might use brand awareness “as a purchase decision heuristic” (Macdonald & Sharp, 2000); (Hoyer & Brown, 1990). Hence brand awareness is most likely to increase and improve market performance of the brand. Brand awareness influences selection of products and can be “a prior consideration base in a product category” (Hoyer & Brown, 1990). Higher the brand awareness, higher the consumer preferences as the brand has “higher market share and quality evaluation” (Dodds, et al., 1991). Brand awareness for luxury brands is a “carefully managed process that applies the most effective communications channels” (Okonkwo, 2007).

d) Brand Positioning: Brand positioning answers the question: “Where are you in the consumer’s mind?” (Okonkwo, 2007). Brand positioning implies that the brand possess a “substantial competitive advantage” or “unique selling proposition”, thereby compelling the consumers to buy the products of that particular brand (Ries & Trout, 2001) (Wind, 1982) (Aaker & Shansby, 1982). When positioning a new brand, the marketer has the option to position the brand as a “differentiated product” in the overall market (Sujan & Bettman, 1989). With such a strategy the brand is positioned in a way, where it is superior to other brands with the help of “distinguishing attributes” and it also shares important characteristics with other brands in the same category (Dickson & Ginter, 1987).

Creating and establishing a “unique position” in the market, requires careful selection of the “target market” and establishing “clear differential advantage” in the mind of the consumers. This unique positioning can achieved through brand image, name, design, service, packaging, guarantees and delivery (Jobber & Ellis-Chadwick, 2016). New luxury brands, although affordable, have a “reasonable level of perceived prestige”, differentiating them from other middle-range products (Silverstein, et al., 2005). However, prices at which such products are sold, are only slightly higher than those of the comparable mid-range products, with the intention of reaching a target, broader than that of “niches of traditional luxury brands”. This strategy can be described as a “masstige strategy”. The masstige strategy is considered to be effective and innovative as it provides a successful combination of prestige positioning and broad appeal, without much or any brand dilution (Truong, et al., 2009).

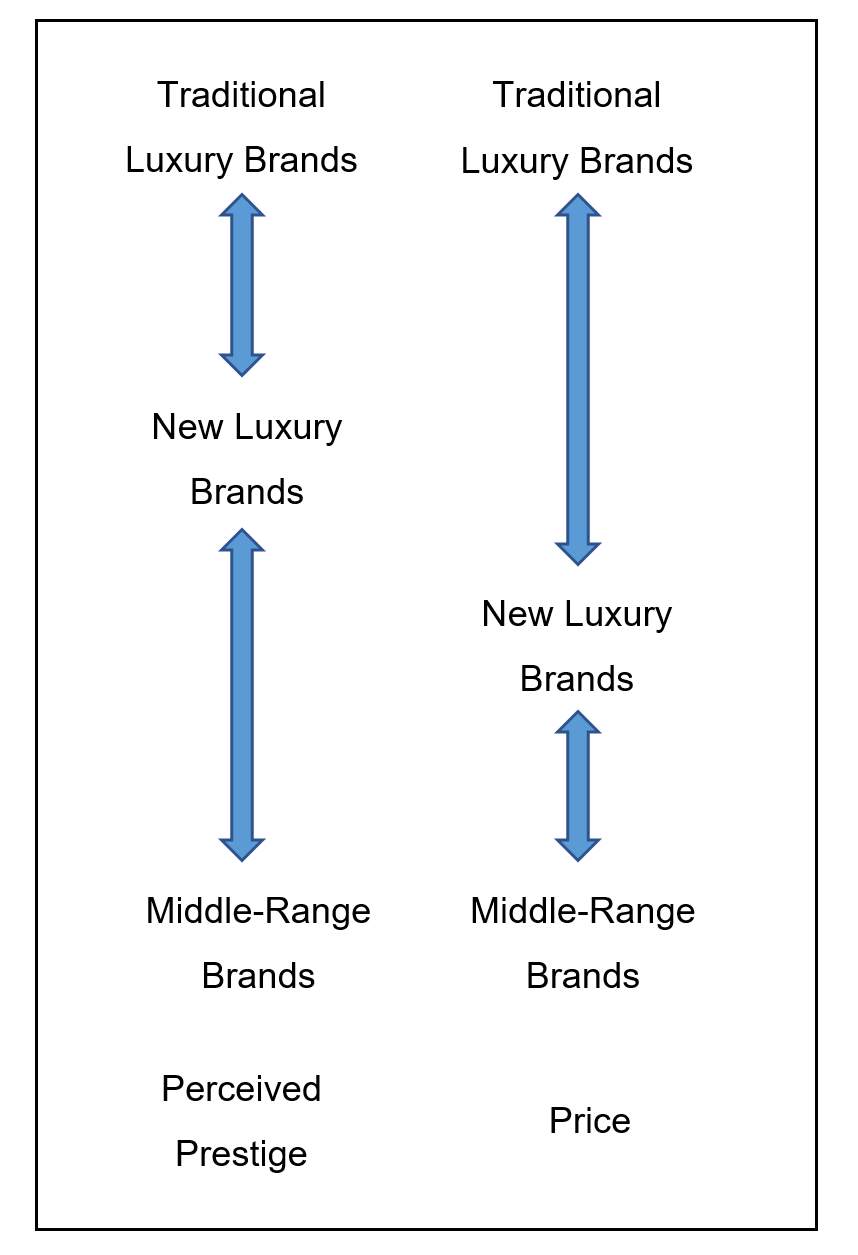

Figure 4: Example of Masstige Strategy (Truong, et al., 2009)

The above figure shows an example of the masstige strategy, where although the new luxury brands are closer substantially to traditional luxury brands as compared to the “middle-range” brands, the new luxury brands are closer substantially to “middle-range” brands, in terms of price (Truong, et al., 2009).

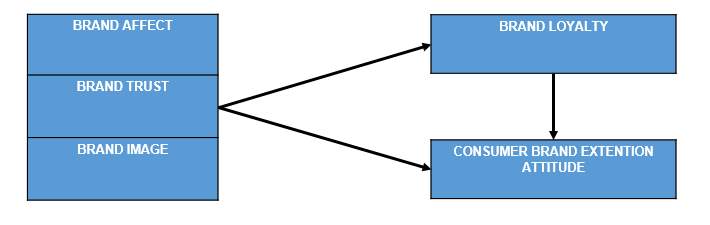

e) Brand loyalty: Brand loyalty answers the question: “Who wants you?” (Okonkwo, 2007). Brand loyalty can be defined as “a deeply held commitment to rebuy or repatronize a preferred product/service consistently in the future, thereby causing repetitive same-brand or same brand-set purchasing, despite situational influences and marketing efforts having the potential to cause switching behavior” (Oliver, 1999, p. 34). “Brand-loyal” consumers perceive the brand to have some unique values, which not other brand can provide, and therefore they might be “willing to pay more” for the brand (Pessemier, 1959); (Jacoby & Chestnut, 1978); (Reichheld & Teal, 1996). This uniqueness may come from a “greater trust in the reliability” of the brand, or from the favorable effect from the use of the brand (Chaudhuri & Hoibrook, 2001). Consumers of luxury brands display a high level of emotional attachment and brand loyalty, which might seem irrational to outsiders as luxury brands assist the customers to display a “self-image” as a result of “high-status” and “prestige” features associated with the brand (Okonkwo, 2007).

Moreover brand loyalty helps in capturing a greater chunk of the market share, when loyal customers repeatedly purchase the same brand, whether or not “situational constraints” come up (Assael, 1995). Therefore customer loyalty might lead to “superior brand performance” in terms of premium pricing and greater market share (Chaudhuri & Hoibrook, 2001). There are two dimensions of brand loyalty, namely: behavioral loyalty and attitudinal loyalty. Behavioral loyalty can be considered as the frequency at which repeat purchases are done (Anwar, et al., 2011). On the other hand dedication, priority and the “purchase aim of the consumers” defines attitudinal loyalty (Mellens, et al., 1996). Consumers become loyal to the brand when they are satisfied with its performance (Bloemer & Kasper, 1995). The company can offer brand’s extension to its loyal customers without fear of failure, and enhance its productivity (Reichheld & Sasser Jr, 1990).

Figure 5 (Anwar, et al., 2011)

Aaker (1991) has specified that brand loyalty has certain marketing advantages like, new customers, reduction in marketing cost, “greater trade leverage”. It costs six times more to win a new customer than retain an existing one (Peters, 1988)

Continuously appealing to the tastes of the consumers, well designed service package along with the products and customer satisfaction can help luxury brands to achieve brand loyalty. The luxury brands must remind the customers continuously of “the value of their products and the worth of loyalty to their brands” and must strive to achieve customer satisfaction (Okonkwo, 2007).

f) Brand equity: Brand equity answers the question “Who likes you?” (Okonkwo, 2007). It is the “incremental utility or value added” by the brand name to its products, such as Kodak, Coke, Nike (Park & Srinivasan, 1994); (Kamakura & Russell, 1993); (Rangaswamy, et al., 1993). Brand equity is an important aspect of building a brand (Keller, et al., 1998). Brand equity brings with it various advantages such as “higher consumer preferences and purchase intentions” (Cobb-Walgren, et al., 1995). Keller (1993, p. 8) referred brand equity as “customer-based brand equity” and defined it as “the differential effect of brand knowledge on consumer response to the marketing of a brand”. Aaker (1991, p. 15) defined brand equity as “a set of brand assets and liabilities linked to a brand, its name and symbol, that add to or subtract from the value provided by a product or service to a firm and/or to that firm’s customers”. As per Aaker, brand associations, brand awareness, brand loyalty, perceived quality, and other proprietary assets were the assets of brand equity.

Brand equity can be determined after subtracting the “utility of physical attributes” of the products from the “total utility of a brand” (Yoo, et al., 2000). Brand equity helps in enhancing the cash flow of the business (Simon & Sullivan, 1993). It also helps the brand to differentiate itself from others, by providing competitive advantage, “based on nonprice competition” (Aaker, 1991).

Brand equity needs to be “sustained and grown” so as to increase value of the luxury brands and all elements of branding need to be nurtured in order to maintain brand equity. It is necessary to sustain, what the consumers feel, see, hear and know about the brand, resulting in their “overall experience with the brand” as such elements remain in the minds of then consumers, enhancing brand associations in the minds of the consumers helps in maintaining sustainable brand equity. This implies that when “favorably viewed by consumers”, brands help in generating positive “consumer-based brand equity” (Okonkwo, 2007).

Consumer based brand equity is ‘‘cognitive and behavioral brand equity at the individual consumer level’’ (Yoo & Donthu, 2001, p. 2). It can be measured on the basis of four dimensions, namely: brand loyalty, brand association, brand awareness and perceived quality (Jung & Shen, 2011). These dimension can help the brand to understand the elements that consumers consider while recognizing brand value and making a decision about purchasing luxury goods (Jung & Shen, 2011). Aaker 1991, defines perceived quality as consumers’ knowledge of the superior quality of a product over other similar products. Consumers associate luxury goods with superior quality and thus they have higher perceived value for luxury brands (Aaker, 1991).

g) Brand Value: It answers the question “What have you gained?” (Okonkwo, 2007). The concept of brand value is deep rooted in added value (Jones, 1986). Added value is an important aspect of the brand’s definition (Jones, 1986). As per (Grönroos, 1994), the essential solution is represented by the core value, whereas the added value represents the additional services.

Brand value consists of three tiers, namely “core functionality”, “emotional values” and “added value services”. Brands can create “core functionality” and “emotional values” by offering the following (Maklan & Knox, 1997):

- Reducing the life-cycle cost of use or ownership by improving the quality of the product.

- Provisioning of services that will reduce the hassle and cost of acquiring and maintenance.

- Increasing the “value-in-use” by enhancing the product functionality.

- Creating prestige and status for the owners.

However, added value is concerned with bringing extra features, which will help enhance the usage of the brand for the consumers (Maklan & Knox, 1997). Expected brand value, consists of four elements which are: product performance, product distribution performance, performance of support services and company performance, and each component integrates “both tangible and intangible elements” (Mudambi, et al., 1997). Brand value is thus a function of expected performance of intangible and tangible attributes and the expected price (Mudambi, et al., 1997).

2.7 Summary

The model shown in Figure 3 by Okonkwo (2007), provides a simplistic view of the brand building process, for luxury fashion brands. On the other hand the nine characteristics highlighted by Fionda and Moore (2009), provides the dimensions on which the brand building process of luxury fashion brands are based. It is also seen that there are a few laws that may not apply to luxury fashion brands. For example the law of price elasticity doesn’t hold good in the case of luxury fashion brands, because no matter how much the prices increase the demand for these goods will not decrease.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Branding"

Branding is widely thought of as simply designing a logo or symbol used to identify a company but is a much broader practice that aims to give meaning to a company and its products or services through researching and developing recognizable features, behaviours and practices that shape the way consumers see them.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this literature review and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: