Observation of On-task Behaviour of Children Diagnosed with ASD

Info: 10376 words (42 pages) Dissertation Methodology

Published: 30th Nov 2021

Chapter 3 Methodology

3.1 Participants

Ethical approval from Queen’s University, Belfast was obtained before the outset of the research. The study followed the standards defined by the Behaviour Analyst Certification Board in the Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behaviour Analysts (BACB, 2014) for scientific competence and ethical research. Through the delivery of consent forms, permission was obtained from participants’ parent/guardian before the research was undertaken. The consent form consisted of; acknowledging potential benefits and risks related to taking part in the study; how data will be collected, stored and disposed of; how data will be anonymized and kept confidential; at what point in the study and how consent could be withdrawn; the researcher and the researcher’s supervisor’s contact information. The consent form was sent home with the children from school prior to data collection. There is a copy of the consent form available in Appendix (chapter 8).

The participants in this study were three children diagnosed with ASD attending a special education needs school in the north of Wales providing for approximately 200 pupils between the ages of three and 19 years. All participants attended the school Monday-Friday 9:00-15:00 and were eligible for the study as they engaged in frequent off-task behaviour that interfered with learning.

The requirement for inclusion in the study was a lack of on-task behaviour displayed by the student during independent work. To demonstrate on-task behaviour, students must 1) actively listening to teacher instructions. An example of this is by responding verbally (e.g. answering questions) or responding nonverbally (shaking head). 2) Abiding by the teacher’s instructions, 3) facing the teacher or task and 4) seeking help appropriately e.g. asking questions or raising their hand (Allday and Pakurar, 2007). Non-examples include: looking out of the window, not looking at the teacher, holding and playing with items, head down on /facing the desk for more than 5 seconds. The three students that participated in the study were chosen by the teacher for displaying the least on-task behaviour during independent work in the classroom.

Neither participant was taking medication during the course of the study. All three were members of a class of ten children with one teacher and three teaching assistants (0.4:1 staff to child ratio). The school is bilingual (English-Welsh) therefore work and materials in the classroom are all presented in both languages in accordance to the 1993 Welsh Language Act which requires that all programs, assessment and training materials are presented bilingually (Welsh Language Act, 1993). Working alongside the teacher’s in this school are an ABA team. The team consists of a consultant behaviour analyst, a BCBA and two assistant-level behaviour analysts. The team work with the teachers to create and carry out behavioural interventions or plans that are based on the principles of the science of ABA. They also provide training for teachers and classroom assistants to deliver the teaching programs and behavioural interventions.

Participant 1, who for the purpose of this investigation will be referred to as Owen, was seven years old at the onset of the intervention and had been attending the school since he was five. Owen was eligible for this study as his teacher described that he frequently engaged in off-task behaviour in the classroom through echolalia, or distracting his peers through touching them, or talking to them.

Participant 2, Sara, was seven years old at the beginning of the intervention and had only just moved from a mainstream school in September 2016. Sara consistently displayed self-stimulatory behaviour in the form of hand flapping during work sessions, and frequently got up from her chair to walk around class.

Participant 3, Daniel, was eight years old at the beginning of the intervention and had been attending the special needs school since he was five. Daniel’s teacher noted that he had great difficulty staying on-task in the classroom as he often looked out the window, and sat very low in his chair in a lying down position.

3.2 Setting

All observations and intervention took place during work sessions the classroom on normal school days for a period of 8 days (2 school weeks). This isolated room was familiar to all the children and consisted of two tables with ten chairs, a whiteboard at the front of the class where the teacher stood, and three cupboards at the back of the class where the children kept their bags and teaching materials. The day was split into periods as follows;

Table 1. Normal school-day routine for participants’ class

| Time | Activity |

| 9-9.30am | Registration and welcome song |

| 9.30-10.45am | Work session |

| 10.45-11.00am | Play time |

| 11.00-11.45am | Work session |

| 11.45am-12.25pm | Lunch time |

| 12.25pm-1pm | Lunch time play |

| 1-1.45pm | Work session |

| 1.45-2pm | Snack |

| 2-2.15pm | Play time |

| 2.15-2.45pm | Collective worship/class wide songs |

| 2.45-3pm | Toileting/preparing for home time |

| 3pm | Home time |

This schedule was strictly followed in order for the pupils to learn their routine and be comfortable in school.

3.3 Materials

The MotivAider was used as a tactile cue to self-monitor throughout the intervention phase as the independent variable. The pocket-sized device can be effortlessly programmed to vibrate at different time intervals with a range of 1-5 strength of vibration option. The MotivAider was attached to the child’s waistband and programmed to vibrate on a 3-minute fixed-time schedule with a vibration strength of 4. The MotivAider would automatically re-start after every vibration. The student was presented with a self-monitoring form, which is available in the appendices, to record whether he was on-task at the time the MotivAider vibrated.

Digital timers to measure duration of observations were used, data sheets appropriate for event recording and for general note-taking were designed for the needs of the study, the FAST questionnaire to determine function of behaviour, and a social validity questionnaire for the teacher were used and can be found in the appendices.

Functional Behaviour Assessment

A Functional Behaviour Assessment (FBA) was conducted for all three participants using an indirect assessment method; The Functional Assessment Screening Tool (FAST) (Iwata and DeLeon, 2006) to identify the maintaining variables of lack of on-task behaviour. The FAST (Iwata and DeLeon, 2006) is a 16-item questionnaire concerning antecedent and consequent events of an episode of problem behaviour. The person completing the questionnaire is asked to circle a ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or ‘N/A’ for 16 statements. It is organized into four categories based on contingencies that maintain problem behavior; 1. social-positive reinforcement (access to attention/tangible items), 2. Social-negative reinforcement (escape from demands), 3. Automatic-positive reinforcement (self-stimulatory behaviour) and 4. Automatic-negative reinforcement (removal of pain/discomfort) (Iwata, DeLeon and Roscoe, 2013). For the remainder of this paper the four categories will be labelled as follows;

Social Positive Reinforcement = Attention

Social Negative Reinforcement = Escape

Automatic (Positive) Reinforcement = Sensory Stimulation

Automatic (Negative) Reinforcement = Pain Attenuation

The number of ‘Yes’ responses are counted and analysed in the scoring summary section of the questionnaire. 1-4 ‘Yes’ responses denote that the behaviour is maintained by Attention, 5-8 ‘Yes’ responses denote that the behaviour is maintained by Escape, 9-12 responses suggest a Sensory Stimulation function and 13-16 ‘Yes’ responses suggest the behaviour is maintained by Pain Attenuation.

The decision to use the FAST as an assessment tool was based on its ease of use, its unobtrusive nature, convenience in that it would not disturb the participants’ daily routine in school, and its time-saving feature. The FAST was completed independently by the teacher and then discussed in an informal interview. This was conducted to evaluate whether the use of the MotivAider to increase on-task behaviour would benefit children with different functions of off-task behaviour.

3.5 Reinforcement

When a behaviour is followed by reinforcement, that behaviour will appear more frequently in future (Cooper, Heron and Heward, 2014). A reinforcement system for work sessions was already in place before the beginning of this study, and was used during the research in line with their usual routine. Before the beginning of every work session in the classroom, the children are presented with their ‘choosing board’. These ‘choosing boards’ consist of pictures of their favourite toys or activities e.g. iPad, outside play, chocolate buttons etc. Parents and members of staff are continuously interviewed during the school year in order to gain a pool of potential reinforcers for each participant. The pictures of these toys and activities are stuck on the board using Velcro. The children use the boards to choose what they would like to work for by pulling off their desired picture and handing it to their teacher. Materials and toys from each child’s ‘choosing board’ were used as reinforcement at the end of each work session.

3.6 Measurement

Momentary time sampling was used to measure the dependent variable on-task behaviour at 20-second fixed intervals during an observation period of 10 minutes. The observation period took place during work sessions in the child’s daily schedule. If the student presented on-task behaviour at the end of the interval the student’s behaviour was recorded as on-task for that interval. The dependent variable, ‘On-task behaviour’ was defined as follows:

To demonstrate on-task behaviour, students must 1) actively listening to teacher instructions. An example of this is by responding verbally (e.g. answering questions) or responding nonverbally (shaking head). 2) Abiding by the teacher’s instructions, 3) facing the teacher or task (reading or writing on their worksheet (Holifield et al., 2010)), and 4) seeking help appropriately e.g. asking questions or raising their hand (Allday and Pakurar, 2007). Non-examples include: looking out of the window, not looking at the teacher, holding and playing with items, head down on /facing the desk for more than 5 seconds.

3.7 Research Design and Procedure

An ABAB reversal design was used with the three participants. Phase A (baseline) was conducted to obtain information regarding pre-intervention levels of on-task behaviour. This was followed by intervention with implementation of the tactile prompt (phase B). Then a return to baseline (A) was conducted and finally a second intervention phase (B). A training phase was implemented after the end of the first baseline period.

The baseline establishes the performance of the participant in the absence of the independent variable, in other words, in the absence of the intervention. This acts as a basis for detecting the effects of the independent variable when it is introduced in future. The goal of a baseline is to establish a stable and predictable trend prior to introducing treatment. A stable and predictable trend of responding can be defined as a pattern that “exhibits relatively little variation in its measured dimensional quantities over a period of time” (Johnston and Pennypacker, 1993a, pp. 199). If the baseline trend is ascending or descending in the therapeutically desired direction, or if the baseline is unstable, the independent variable should be withheld. If the behaviour begins to deteriorate, or the baseline stabilises, the independent variable can be applied (Cooper, Heron and Heward, 2014). During this study, baseline was measured until stable, prior to the introduction of the intervention.

Baseline: During baseline, self-monitoring procedures were not in place. Teachers were instructed to use their typical classroom management procedures for the target behaviour. The child was observed during work sessions with staff: child ratio of 1:4 or 1:5. The researcher observed the child from a distance that would allow them to identify the target behaviour, while being as discrete as possible to reduce reactivity effects.

Training phase and video modelling: Each student was trained to self-monitor his/her on-task behaviour in a video-modelling and a practice session. During the video-modelling session, the students were presented with two short videos to provide visual examples of the target, and of non-examples of the target behaviour. The first video showed what consisted of on-task behaviour and lasted approximately one minute. The video showed a 12 year-old boy sitting at a desk, looking at and writing on the piece of paper in front of him. He then feels the MotivAider vibrate on the waistband of his trousers and notes on his self-monitoring sheet that he is on-task.

The student was also taught what did not consist of ‘on-task behaviour’ in a second video which lasted approximately one minute. The second video showed the same boy sitting at a desk, with a piece of paper in front of him. The boy looks out of the window when he feels the MotivAider vibrate on his waistband and notes on his self-monitoring sheet that he is not on-task.

Each student received one training session prior to the intervention which lasted approximately 10 minutes. During the session, there was an introductory stage aiming to ensure the vibration of the pager did not cause distress to the child. The MotivAider was placed on the child’s hand to feel the vibration. Following this, the MotivAider was attached to the waistband of the child.

During the practice session, the child was asked to colour in a worksheet and the MotivAider was attached to their waistband. On the vibration of the MotivAider the child was required to fill in the self-monitoring sheet and return to work. The mastery criterion for each step of this stage was two consecutive correct responses. Both practice and training sessions took place in an isolated room outside the classroom.

Self-Monitoring Intervention: At the beginning of the session, the teacher presented the student with his/her choosing board and instructed the child to choose what they wanted to work for. After this, the MotivAider was attached to the child’s waistband and the teacher continued to teach as usual. When the MotivAider vibrated, the student noted whether he was on-task on the provided sheet. The work session staff to child ratios were 1:4 or 1:5. During the work session, the children were given work to complete using a 5-10 minute instruction phase, followed by independent work. Data was collected during the independent work phase for 10 minutes across a variety of different activities including maths, literacy and art.

The person(s) collecting data observed the child from a distance that would allow them identify the target behaviour while being as discrete as possible. The data collector sat behind and across from the child.

Additional training was required for Daniel as he would take the MotivAider off his waistband and hold it in his hand to look at it. This distracted him from his work. When this occurred, the behaviour was ignored and MotivAider placed back on his waistband. Daniel received the training phase prior to every work session when he wore the MotivAider.

3.8 Validity

Social Validity: Even if treatment is found successful of effective by researchers, if it is not found useful, helpful, productive and socially valid by the significant others of the participants e.g. parents, teachers, carers, then it is not socially valid (Horner et al., 2005; Horner et al., 2012). Wolf (1978) recommended that data should be collected to identify the values of the intervention to society in three ways; the social significance of the target behaviour, the appropriateness of the procedures, and the social significance of the result e.g. would participants consider using the intervention outside the study, or if they would recommend the intervention to others in future. This is to “help choose and guide program developments and applications” (Baer and Schwartz, 1991, pp. 231), which is ultimately the purpose of social validity assessments (Cooper, Heron and Heward, 2014). Therefore, following the final intervention phase, the classroom teacher completed a social validity questionnaire. Items were rated on a Likert-type scale designed to allow respondents to rate their level of agreement or disagreement with a series of statements. These levels of agreement were as follows; strongly agree, agree, disagree and strongly disagree. The assessment consisted of statements regarding helpfulness of the intervention in the classroom, future use of the intervention, and possible benefits for both students and teachers from the intervention. The questionnaire was completed in less than five minutes and can be found in the appendices.

Internal Validity: Experiments demonstrating high internal validity are experiments that demonstrate clear experimental control; that the changes in the dependent variable, the behaviour, are a function of the independent variable, and not from uncontrolled variables (Cooper, Heron and Heward, 2014).

An ABAB reversal design was used in order to demonstrate experimental control in the form of verification and replication. When the intervention is removed, verification is affirmed as the baseline measures return to initial levels. This confirms that the behaviour is changed by the intervention, and would remain unchanged without the intervention. When the intervention is reintroduced and an increase in the target behaviour is presented, replication is demonstrated. An ABAB design is preferred to an ABA design as it strengthens the demonstration of experimental control because it reintroduces the treatment phase which enables the replication of treatment effect.

Confounding variables minimized to increase internal validity

Maturation: Changes can take place in a subject over the course of time that can be a confounding variable e.g. improved performance may be the result of the acquisition of new skills. This study used rapidly changing conditions and multiple introductions and withdrawals of the independent variable to control for maturation.

Observer Training: A potential threat to reliable data is inadequate observer training. Observers must be able to differentiate between an occurrence or non-occurrence of the target behaviour and record accurately on a data sheet. In this study, the researcher and inter-observer agreement (IOA) data collector received training via video modelling of how to recognise and record the target behaviour. This training was provided to the IOA data collector prior to every work session in order to minimize observer drift.

Observer Reactivity: In order to reduce the participants being aware that they were being observed, the person(s) observing the participants did so from a distance that would allow them identify the target behaviour while being as discrete as possible e.g. sitting behind and across from the participant. Additionally, to reduce the influence of observer reactivity in the data collection, the person(s) collecting data sat on different sides of the room. If one observer predicts that the second observer will record the behaviour of a specific interval in a particular way, the data could be influenced by what the first observer anticipated the other observer may record. By placing both data collectors on different sides of the room, it minimizes the potential for them to consult each other during data collection, and focus entirely on the target behaviour.

External Validity: External validity is the degree to which the functional relation is found reliable and socially valid under different conditions. To maximize external validity data was taken during several activities (maths, literature, art) and across several times of day (morning, mid-day and afternoon work sessions).

3.9 Fidelity of implementation and inter-observer agreement (IOA)

Prior to the beginning of the study, the rationale, procedure and materials of the project were presented to the classroom staff, following an opportunity to ask further questions. On-task behaviour alongside non-examples were demonstrated via the video-modelling that the students received.

The researcher served as the primary data collector, and a Postgraduate Certificate of Education (PGCE) student on work placement in the school collected inter-observer agreement (IOA) data for 20% of the sessions. For the purpose of IOA the second data collector was further trained to identify on-task behaviour by re-watching the video model of the target behaviour before each data collecting session. IOA was collected during the first and third day of data collection across two participants. IOA was calculated by dividing the total number of agreements, by the total number of agreements and disagreements, multiplied by 100. On average, IOA was 96% (range 92% to 100%).

Chapter 4 Results

4.0 Functional Behaviour Assessment

An indirect functional behaviour assessment was completed by the teacher in the form of the Functional Assessment Screening Tool (FAST) (Iwata and DeLeon, 2006). The scoring criteria is summarised in the table below and is taken from the FAST which is available in the appendices.

Table 2. Scoring Summary for the FAST

| Number Of Items Circled ‘Yes’ | Potential Source of Reinforcement |

| 1-4 | Attention/Preferred Items |

| 5-8 | Escape |

| 9-12 | Sensory Stimulation |

| 13-16 | Pain Attenuation |

The results are summarised for all 3 participants and are available in Table 3 below.

Table 3. Results of Functional Analysis Screening Tool for each participant’s decreased on-task behaviour

| Name | Number Of Items Circled ‘Yes’ | Pain Attenuation | Escape | Sensory Stimulation | Attention/

Preferred Items |

| Owen | 3 | ||||

| Sara | 11 | ||||

| Daniel | 7 |

The results of the FAST suggest that Owen’s off-task behaviour is maintained by attention, as he frequently distracted his peers through touching them or talking to them. FAST results suggest that Sara’s off-task behaviour is maintained by sensory stimulation as she frequently displays hand flapping, and that Daniel’s off-task behaviour is suggested to be maintained by escape of demands as he is frequently observed looking out the window, or with his head on his desk.

4.1 Data Analysis

The target was to increase on-task behaviour in three children diagnosed with ASD during work sessions in a special education classroom.

Data from intervals in which the participant presented on-task behaviour was converted into percentage of intervals with behaviour present and was graphed using Microsoft Excel 2010.

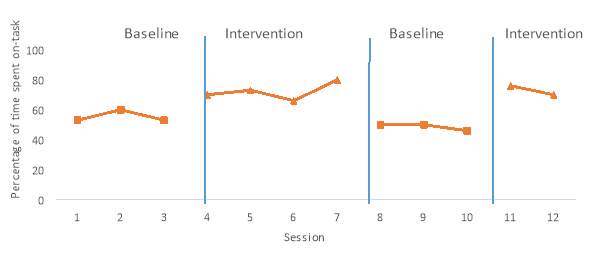

Participant 1: Owen

During the initial baseline condition, Owen displayed on-task behaviour during a mean of 55.3% intervals with a range of 53% to 60%. Intervention conditions (self-monitoring using the MotivAider) showed an increased mean score of 72.25% with a range of 66% to 80%. On-task behaviour decreased to a mean of 48.6% (range, 46-50%) on return to baseline conditions. A reintroduction of the intervention showed an immediate increase in mean on-task behaviours (73%, range, 70%-76%).

When the intervention was first introduced, on-task behaviour increased from 55.3% to 72.25%. After the second introduction of the intervention, on-task behaviour increased from 48.6% to 73%. On average, on-task behaviour increased 20.6% from baseline, during the intervention.

Figure 1. Owen’s on-task behaviour across baseline and intervention conditions

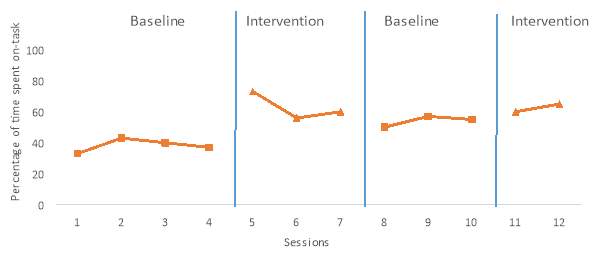

Participant 2: Sara

During the initial baseline condition, Sara displayed on-task behaviour during a mean of 38.3 % intervals with a range of 53% to 60%. Intervention conditions (self-monitoring using the MotivAider) showed an increased mean score of 63% with a range of 66% to 80%. On-task behaviour decreased to a mean of 52% (range, 50-55%) on return to baseline conditions. A reintroduction of the intervention showed an immediate increase in mean on-task behaviours (62.5%, range, 60%-65%).

When the intervention was first introduced, on-task behaviour increased from 38.3% to 63%. After the second introduction of the intervention, on-task behaviour increased from 52% to 62.5%. On average, on-task behaviour increased 17.6% from baseline, during the intervention.

Figure 2. Sara’s on-task behaviour across baseline and intervention conditions

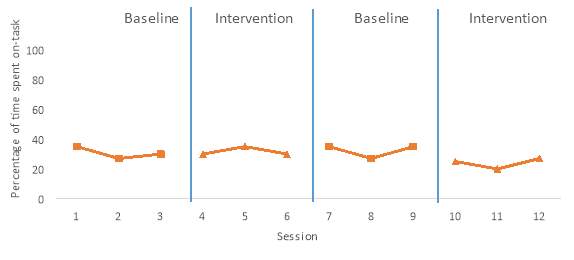

Participant 3: Daniel

During the initial baseline condition, Daniel displayed on-task behaviour during a mean of 30% intervals with a range of 27% to 33%. Intervention conditions (self-monitoring using the MotivAider) showed an increased mean score of 31.7% with a range of 30% to 35%. On-task behaviour decreased to a mean of 30.7% (range, 27-35%) on return to baseline conditions. A reintroduction of the intervention showed a decrease in mean on-task behaviours (24%, range, 20%-27%).

When the intervention was first introduced, on-task behaviour increased from 30% to 31.7%. After the second introduction of the intervention, on-task behaviour decreased from 30.7% to 24%.

Figure 3. Daniel’s on-task behaviour across baseline and intervention conditions

Table 4. Summary table: Mean performance of on-task behaviour

| Name | Baseline Mean: | Intervention Mean: | Change: |

| Owen | 52% | 72.6% | Increase of 20.6% |

| Sara | 45.2% | 62.8% | Increase of 17.6% |

| Daniel | 30.5% | 27.9% | Decrease of 2.6% |

4.2 Accuracy of self-monitoring when the MotivAider vibrated

All three students noted that they were on task 100% of the time, a false positive.

Participants’ self-monitoring sheets were analysed for accuracy of self-monitoring. The students noted whether or not they were on-task every 3 minutes regardless of whether or not they were performing the target behaviour.

Table 5. Data analysis for accuracy of self-monitoring

| Name | Percentage Of Accurate Self-Monitored Intervals |

| Owen | 71% |

| Sara | 65% |

| Daniel | 11% |

4.3 Social validity

The overall impressions for the study were favourable. The teacher agreed that the intervention was easy to implement and that she would recommend the intervention to other teachers. She also agreed that the intervention was an effective way to handle the child’s problem behaviour and that the intervention was beneficial for the child. The teacher strongly agreed that she would recommend the intervention for other students in her classroom.

There was a section in the questionnaire for further comments in which the teacher noted that more time was needed to implement the intervention. She suggested that she would introduce the intervention in more stages, e.g. “allow the child to play with the MotivAider before placing it on him”, and take more time to implement the intervention, possibly from the beginning of term. This would ensure that the student is comfortable with wearing the MotivAider, that it is part of his/her routine, and that the student understands the concept of self-monitoring and the purpose of MotivAider prompts.

It is possible that increased exposure to the MotivAider as described above could have had a positive impact on Daniel’s on-task behaviour. The teacher disagreed with the statement, ‘the intervention made a positive impact within my classroom’ based on Daniel’s performance. Daniel displayed decreased levels of on-task behaviour during the intervention as he was distracted by the MotivAider.

This is also reflected in the questionnaire when she disagreed with the statement ‘the intervention made a positive impact within my classroom’ referring to participant 3, Daniel, who displayed decreased levels of on-task behaviour during the intervention, as he was distracted by the MotivAider. Further analysis of the social validity will be provided in the discussion section.

Chapter 5 Discussion

5.1 Purpose of study

The primary purpose of this investigation was to determine the effect of self-monitoring with a MotivAider on on-task behaviour in three children diagnosed with ASD. The secondary purpose was to examine the attitudes of the teacher towards using the ABA based intervention in the classroom. This study was conducted in order to increase the growing evidence for using low-intensity ABA based interventions in special education needs classrooms in the UK.

5.2 Findings

The results show an increase in on-task behaviour for two out of three of the participants. Participant 1, Owen, displayed an increase of 20.6% in on-task behaviour between baseline and intervention conditions. Participant 2, Sara, displayed an increase of 17.6% between baseline and intervention conditions. For both participants, using the MotivAider to self-monitor as an intervention to increase on-task behaviour and decrease off-task behaviour proved successful. For the third participant, Daniel, the target behaviour remained almost unchanged, with a decrease of 2.6%. Results of the current study suggest that the MotivAider can be used to increase on-task behaviour in some children with ASD in a special education needs classroom.

The accuracy of self-monitoring varied greatly across the three participants from 11% to 71% accuracy. It has been reported that it is not required for students to accurately record their on-task behaviour in order for the intervention to take effect (e.g. Marshall, Lloyd and Hallahan, 1993; Legge, DeBar and Alber-Morgan, 2010). These findings were reflected in the current study. Owen self-monitored accurately 71% of intervals and increased his on-task behaviour by 20.6%, and Sara self-monitored accurately 65% of intervals and increased her on-task behaviour by 17.6%. However, the student that was most accurate in self-monitoring, showed the greatest increase in on-task behaviour, and similarly, the student that displayed the lowest accuracy in self-monitoring also displayed the least change in target behaviour at 2.6%. Results from the accuracy of self-monitoring in this study suggests that the more accurate the student is in self-monitoring, the greater the effect the intervention will have on the target behaviour.

Treatment must be found useful and productive by the significant others of those receiving the treatment in order to be socially valid (Horner et al., 2005). The results from the social validity questionnaire present an overall favourable impression towards the intervention as the teacher noted that she would recommend the intervention to other teachers and other students in the classroom. This suggests that low-intensity ABA interventions would be recommended to students and teachers, by teachers who are introduced to their benefit and ease of application. This result is similar to previous studies (e.g. Amato-Zech, Hoff and Doepke, 2006; Boswell, Knight and Spriggs, 2013) who noted that teachers and students provided high ratings of treatment acceptability in using tactile self-monitoring prompt to increase on-task behaviour in a special education classroom and would further recommend the low-intensity ABA based intervention to teachers and students in other classrooms.

5.3 How this relates to previous research

The success of this low-intensity ABA based intervention in a special education needs classroom is similar to previous studies (e.g. Foran et al., 2015; Boswell, Knight and Spriggs, 2013; Grindle et al., 2012; McDougall, Morrison and Awana, 2012; Eldevik et al., 2006). Using the MotivAider as a self-monitoring intervention can increase on-task behaviour in special education classrooms, consistent with previous research (Amato-Zech, Hoff and Deopke, 2006; Boswell, Knight and Spriggs, 2013; Farell and McDougall, 2008; Legge, DeBar and Alber-Morgan, 2010; Navarrete et al., 2006). The increases in on-task behaviour in previous research are considerably higher than in the present study. There are several possible factors from previous research discussed below that may explain this trend: e.g. older participants, interventions were presented during single subject classes rather than across the curriculum; the use of additional verbal prompts by classroom staff; the use of shorter time-sampling intervals; the presence of the experimenter for the duration of the study; and the recruitment of participants with a range of diagnoses (i.e. not limited to ASD, as in the present study).

Amato-Zech, Hoff and Deopke (2006) studied three participants in an American school and increased their on-task behaviour from a mean of 55% to more than 90% (increase of 35%). This 35% increase is considerably higher than the 20.6% and 17.6% change that was observed in the current study. This can be explained by four variables. The participants in Amato-Zech et al.’s study were four years older (11 years old) than the participants in the present study (7 years old), and may have developed skills in their maturity that would assist them in being more successful at self-monitoring. Secondly, Amato-Zech et al. noted that at baseline levels, the target behaviour was observed at a mean of 55%, which is 12.6% higher than the present study’s 42.6%. This lower mean suggests that the target behaviour may be new to the participants or not yet fully mastered in their repertoire as it is not displayed as often. Thirdly, Amato-Zech and colleagues observed the participants in one class only; reasoning and writing class, whereas the present study used a range of classes including art, maths and language in order to generalise the skill, which in turn, could take longer to master. A further difference is that the present study’s inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of ASD, but Amato-Zech et al., recruited participants with speech and language impairment and specific learning disability. The needs of children with ASD vary remarkably to those with learning disabilities and speech and language impairment, therefore it is difficult to make comparisons. The present study’s results reflect that self-monitoring can be effectively taught to children with ASD to increase on-task behaviour which extends the research by Amato-Zech et al., (2006) who show the same results with children diagnosed with speech and language and specific learning disabilities.

Boswell, Knight and Spriggs (2013) reported that an 11-year old student diagnosed with moderate intellectual disability increased his on-task behaviour using the self-monitoring intervention prompted by a MotivAider from 29% at baseline to 100% in the final condition of an ABAB reversal design (increase of 71%). This higher increase compared to the present study can be explained by a lack of generalization and the presence of additional prompts. Boswell, Knight and Spriggs (2013) observed the target behaviour during maths classes only and an assistant who accompanied the student in class typically prompted him to stay on-task during the intervention phase. In the present study, the only prompt that the children received to stay on-task was from the MotivAider.

A study using participants with ASD is by Legge, DeBar and Alber-Morgan (2010) who observed 3 boys (aged 11-13). Two of the boys had a diagnosis of ASD and one had a diagnosis of Cerebral Palsy but frequently displayed symptoms of ASD (e.g. stereotypy). The researchers demonstrated increases in on-task behaviour using a self-monitoring intervention with a MotivAider with a 65%, 45% and 20% increase. Again, in this study, the increases in target behaviour are greater than observed in the present study, but can also be explained by the following limitations. The study used 2-minute intervals as momentary time-sampling measurement, as opposed to a more conservative 3-minute intervals in the present study. Secondly, the researchers note that the outcome of the successful data may be a result of the presence of the experimenter. The same experimenter trained the students and also implemented the intervention over a period of several weeks. It is possible that the students may have associated her presence with the target behaviour. The present study ensured that the researcher would not cause observer reactivity by sitting at a distance that would allow the target behaviour to be identified while being as discrete as possible and sitting behind and across from the participant.

The present study has shown how on-task behaviour can be increased in younger children than previous research has investigated and in a variety of subjects or classes that differs from the single subject past research. It has also shown that children with ASD can use self-monitoring effectively and increase their on-task behaviour without additional prompts from paraprofessionals. This increases the evidence for low-intensity ABA based interventions in special education classrooms.

5.4 The MotivAider; A function based intervention?

The results of the FBA suggested that all three participants had different functions to their behaviours. Owen’s lack of on-task behaviours were found to be maintained by attention, Sara’s maintained by sensory stimulation and Daniel’s maintained by escape from demands. As discussed above and in the results section, the intervention had a greater effect on Owen (on-task behaviour increased by 20.6% from baseline) and Sara (on-task behaviour increased by 17.6% from baseline) than on Daniel, whose behaviour remained almost unchanged, with a decrease in on-task behaviour of 2.6% from baseline. This suggests that the MotivAider as an intervention to increase on-task behaviour, is a function based intervention for attention and automatic maintained behaviours, but not escape maintained behaviours. Similar previous research (e.g. Amato-Zech, Hoff and Doepke, 2006; Farell and McDougall, 2008; Legge, DeBar and Alber-Morgan, 2010; Boswell, Knight and Spriggs, 2013) did not conduct a FBA to identify the function of off-task behaviour, therefore comparisons cannot be made. A recommendation for future research is to investigate the use of the MotivAider as a function-based intervention. A thorough FBA, such as a Functional Analysis (FA), conducted prior to the introduction of the intervention could confirm that the MotivAider is a function based intervention for attention and automatic maintained off-task behaviours, and not for escape or pain attenuation maintained off-task behaviours, as is suggested in the present study.

The FBA conducted in this study has limitations. The FBA was an indirect method of collecting information, which does not directly observe the behaviour. Caregiver descriptions from questionnaires and verbal reports about behaviour are often unreliable and inaccurate (Arndorfer et al., 1994; Conroy, et al., 1996; Duker, and Sigafoos, 1998; Sigafoos, Kerr, and Roberts, 1994; Sigafoos et al., 1993) as people have a biased recall of the behaviours and the environmental conditions under which they occurred (Cooper, Heron and Heward, 2014). For example in interviewing caregivers (e.g. parents, teachers, friends) for student preferences, more often than not the interviews do not correspond with direct assessment of preferences (Green et al., 1991; Green et al., 1988). Iwata and colleagues (2013) compared FAST outcomes with results of 69 FA’s where the FAST score predicted the maintenance of the problem behaviour in just 63.8% of cases. They note that the “FAST is not an approximation to a functional analysis of problem behaviour” (pp. 283) and state that is has limited validity. This method was chosen because of its convenience and time-saving properties. Another, more rigorous and thorough FBA method that could be used in future research is Functional Analysis.

A Functional Analysis (FA) is not conducted under naturally occurring circumstances. Antecedents and consequences are arranged in order to observe and measure their separate effects on the problem behaviour. FA’s have been shown extremely effective in identifying the environmental determinants of problem behaviour (e.g. self-injurious behaviour, Iwata et al., 1994). There are typically four conditions in a FA, similar to the FAST; contingent attention, contingent escape, alone and a control condition (Cooper, Heron and Heward, 2014). Elevated levels of problem behaviour in the contingent attention suggests that the behaviour is maintained by positive reinforcement, elevated levels of problem behaviour in the contingent escape condition suggests that the behaviour is maintained by negative reinforcement. Behaviour is maintained by automatic reinforcement if it is high in the alone condition. Implementing the procedures and interpreting the data of FA’s is possible with as little as two hours training (Moore et al., 2002; Iwata et al., 2000). This suggests that professionals such as teachers who have limited knowledge evidence-based interventions from teacher training (Dillenburger et al., 2014) could easily implement a FA with a short-training session.

FA is the only FBA method that can lead to functional rather than correlational data (Asmus, Vollmer and Borrero, 2002). The method is time-saving, more accurate than other FBA methods, can be conducted with little training and identifies maintaining reinforcers of problem behaviour (Mueller, Nkosi and Hine, 2011). Indirect methods such as questionnaires should be used as preliminary hypothesis of the function of behaviours, and if opportunities to collect data are unavailable. To be able to confirm whether the MotivAider is a function based intervention for behaviours maintained by attention and sensory stimulation, a functional analysis should be conducted on the on-task behaviour of the participants prior to implementing the intervention. This would strengthen the evidence suggested by the present study; the MotivAider is a function based intervention for children whose off-task behaviour is maintained by attention and sensory stimulation.

An additional thought for observing behaviours maintained by attention in the classroom, is whether the behaviour is maintained by peers or teachers. It has been suggested that general education teachers and student peers are capable of participating in the FA within the usual daily routine of the classroom (Skinner, Veerkamp and Andra, 2009). It is important to explore this factor as the motivating operations and reinforcers in natural settings e.g. social reinforcers provided by peers need to be identified. In a school setting, future researchers should consider manipulating conditions in which both teachers and peers deliver social reinforcers in order to be able to identify what maintains the target behaviour (Broussard and Northup, 1995; Wehby, Symons and Shores, 1995). An example of this is Jones, Drew and Weber (2000) who assessed disruptive behaviour in a student with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in a mainstream classroom using a FA with teacher attention, peer attention, escape, and non-contingent reinforcement conditions. The researchers found that peer attention was the primary maintaining variable for the target behaviour. A similar procedure would be useful in a FA for MotivAider intervention.

5.5 Limitations

To increase the on-task behaviour during the intervention phase, a thorough and specific training plan should be created and implemented. This was not included in the present study. The MotivAider was completely new to the children, and this was reflected in their behaviour in the initial presentation of the device. All three participants were happy and comfortable to wear the MotivAider, however, they behaved quite differently in the work sessions. Owen, was very excited to be introduced to the MotivAider, and told his peers and other teachers that he was wearing it. He liked to show them by lifting his jumper and pointing to the device. When reminded that it was a work session, he quickly put down his jumper and proceeded to follow instructions and complete his work. Sara was very comfortable wearing the MotivAider, seemed undistracted and was not fazed by the device. Daniel however, frequently took off his MotivAider to look at it in his hands, shake it and press the buttons on it.

As suggested by the teacher in the social validity questionnaire, more time needs to be taken in introducing children to the MotivAider in order to desensitize them in a training phase. This will be described within the next sections; ‘Educational Applications’.

Previous research (e.g. Boswell, Knight and Spriggs, 2013; Tzanakaki et al., 2014) has utilized a variety of measures such as the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (4th Edition; Wechsler, 2003) or the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale Fourth Edition (SB-IV; Thorndike, Hagen and Sattler, 1986) to measure IQ, and the Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scale-Survey Form (VABS; Sparrow, Cicchetti and Balla, 2005) to measure composite, communication, socialization and daily living skills scores. Such measures have allowed the researchers to control and predict the effect of factors such as severity of Autism and intellectual disability as these may affect participants’ ability to self-monitor and identify target behaviours. The methodology of the present study did not include such measures and this may be a possible limitation. Autism is a spectrum disorder, therefore it is possible that each child would react differently to this intervention, e.g. in rate of learning, accuracy of self-monitoring, retaining the skill, generalising the skill etc. Research including a severity of Autism measure, could assist in selecting candidates most likely to self-monitor effectively.

The MotivAider has proved to be useful to increase a range of skills and is recommended in previous research for special education classrooms at an expense of £88 (Amazon). It would be difficult to provide a MotivAider for several students in a classroom with such a high cost. However there is a recently developed iPhone app ‘MotivAider for mobile’ available for an extremely reasonable £2.99 that could be used on student smart phones to overcome this financial issue. In 2012 the MotivAider for mobile was released by developer Behavioural Dynamics Incorporated (Itunes/Behavioral Dynamics, 2012). The app is easy to use, and uses a private prompt in the form of a text message to repeatedly trigger the desired behaviour. First, the user must devise a brief personal message that will be emitted to remind the individual to engage in the desired behaviour. This message is delivered with a vibration or audible cue on either a fixed or varied schedule. Currently, there is no literature exploring the use of the MotivAider app as a self-monitoring tool in children with ASD. Future research should explore whether students with ASD in a special needs classroom are able to use the app, and whether it has the same effects as using the MotivAider device. This could decrease cost further for schools, students and society.

This treatment package of self-monitoring with the cue of a MotivAider has decreased problem behaviour and increased socially significant behaviour. When presented together, it is not possible to determine which component is responsible for the behaviour change. A component analysis could detect the effective component of the treatment package by presenting each IV in isolation (Baer, Wolf and Risley, 1968). This could be done by teaching the participant to self-monitor, then use different prompts e.g. visual prompt, verbal prompt etc. to determine whether it is the tactile prompt from the MotivAider that promotes the increase in on-task behaviour.

A further limitation to this study, is that no fading condition was implemented post-intervention. Legge, DeBar and Alber-Morgan (2010), successfully increased on-task behaviour in three students with ASD. The researchers found that after a systematic fading condition, all three students maintained high percentages of 80-100% on-task behaviour. They used fixed-time schedules of 2-minutes during the intervention phase. During the fading condition, they introduced variable-time schedules of 4-minutes to 10-minutes. The present study could have followed the same form of fading condition. However, one could argue that if the MotivAider is effectively increasing on-task behaviour there is no need for a fading condition. If the MotivAider is increasing academic scores, decreasing teacher workload and problem behaviour without affecting other students in the classroom, is cost-effective for the school, is viewed favourably by both student and teacher, and improves the quality of life of the student, it can be worn indefinitely.

The intervention as effective for two out of the 3 participants, therefore an additional limitation to the study is the small sample size. Although the research provides useful information for future studies, a higher sample size would increase external validity.

The most significant limitation to this study is the lack of accuracy and completion of work sheets or assignments data during the intervention. Boswell, Knight and Spriggs (2013) showed that Maths fluency increased as on-task behaviour increased in their participant. Not only did the target behaviour improve with the MotivAider, but also academic performance. Meaningful conclusions cannot be drawn about the effects of the self-monitoring procedure on academic productivity and accuracy from the present study.

Strengths of the Design

A strength of the ABAB reversal design is that it demonstrates experimental control in the form of verification and replication. When the intervention is removed, verification is affirmed as the baseline measures return to initial levels. This confirms that the behaviour was changed by the intervention, and would remain unchanged without the intervention. When the intervention is reintroduced and an increase in the target behaviour is presented, replication is demonstrated.

The reversal design is appropriate here as the MotivAider can be taken away from the student and does not fall into the problem of irreversibility (Cooper, Heron and Heward, 2014). An example of an irreversible intervention would be if the student was taught to read as the skill has been taught and cannot be removed. On that occasion, a design such as an alternating treatment design or multiple baseline may be more appropriate e.g. Mayfield and Vollmer (2007) who taught Mathematic skills using a multiple baseline design.

5.7 Educational Applications

The present study and its results suggest several applications for future use of the MotivAider as a prompt for self-monitoring on-task behaviour in a special needs classroom. Firstly, use thorough, specific teaching phases for using the MotivAider. In classrooms, the teacher could be implementing the intervention as standard practice, which would not be reliant on the time-consuming return of consent forms. The teacher could take their time and introduce the intervention with an appropriate teaching plan with precise stages, as this study has shown is required. The evidence from this study suggests that using the MotivAider as a prompt for self-monitoring in a classroom environment requires a longer and more specific training phase than was used in the present research. Legge, DeBar and Alber-Morgan (2010) described a 20-minute training session that they conducted twice with their participants. The students were required to reach an 80% accuracy in self-recording which resulted in a successful intervention with increased on-task behaviour.

Taylor and Levin (1998) used a specific, systematic teaching procedure to teach a 9 year old student with ASD to use a prompting device (the Gentle Reminder) as a prompt to make verbal initiations about his play activities. This teaching procedure was further developed by Tzanakaki et al., (2014) to use the MotivAider to prompt social initiations in children with ASD. The plan was split into eight stages in order to familiarize and desensitize the participant to the MotivAider, teach the target behaviour, teach the child to present the target behaviour upon the prompt, generalising the skill in a different setting and with different adults. For example, in phase 1, Tzanakaki et al.,s objective was that the child would not show observable signs of distress or startle when a MotivAider vibrates in their pocket, phase 2’s objective was for the child to perform the target behaviour when the MotivAider vibrated on the table. The researcher built on every skill in each teaching stage and successfully demonstrated how a MotivAider can be used as a prompt for social initiations in a school environment. Each training stage was conducted in two sessions a day, lasting approximately ten minutes. Each training stage had a mastery criteria with an objective and teaching procedure instructions. This teaching plan could be used and further developed for a teaching plan for introducing a MotivAider as a prompt for self-monitoring on-task behaviour in a classroom environment. E.g. stage 1; same as Tzanakaki et al., stage 2; the child must be able to self-monitor accurately upon the vibration of the MotivAider when it is placed on the table, stage 3; the child must be able to self-monitor accurately when the MotivAider is in their pocket and their hand is placed on top, stage 4; the child must be able to self-monitor accurately when the MotivAider vibrates in their pocket when their hand is not in their pocket (i.e. is on the table). By creating a teaching plan with many stages and a specific mastery criteria, it will ensure that the child is comfortable, accurate and successful in using the MotivAider as a prompt for self-monitoring as evidence from the present study from results of the on-task behaviour during the intervention, and results from the social validity questionnaire suggest a need for specific, intensive training for using self-monitoring with a MotivAider as an intervention for increasing on-task behaviour in children with ASD.

Secondly, the present study suggested that the higher the accuracy of self-monitoring, the higher the increase in on-task behaviour. Therefore, accuracy of self-monitoring provides information on the increase of on-task behaviour that will be observed when using the MotivAider. In future applications of this intervention, the student should master self-monitoring before using the MotivAider in their daily routine. This can be achieved in the training phase discussed above.

Thirdly, this study demonstrates that students as young as 7 years old can successfully be taught to use the MotivAider as a self-monitoring prompt for on-task behaviour. Therefore, the use of the MotivAider should not be limited to older children (aged 11+) as is suggested by previous research.

Lastly, the social validity questionnaire has increased the evidence for the use of low-intensity ABA based interventions in special education classrooms, as the intervention was rated favourably by the teacher who had limited prior knowledge of ABA.

5.8 Ethical Implications

Withdrawing an effective intervention using a reversal design has ethical implications. Increasing on-task behaviour in students can give them more independence and increase a positive environment in the classroom. Additionally, increasing on-task behaviour has been shown to increase academic performance (McDougall, Morrison and Awana, 2012). As Behaviour Analysts we must follow the Professional and Ethical Compliance Code (BACB, 2014) which states that clients have a right to effective treatment (2.09). This suggests that withdrawing an effective intervention should be avoided. The use of a multiple-baseline design could overcome this.

Chapter 6 Conclusions

Children with ASD who receive teaching methods primarily based on the science of ABA make more significant gains on social, communication, language, play and cognitive skills than children who do not (Eldevik et al, 2009; Grindle et al., 2012, Remington et al., 2011; Reichow and Wolery, 2009; Virues-Ortega, 2010). Recent evidence suggests children with ASD do not require high-intensity interventions such as EIBI to make significant gains, as an increase in in low-intensity, low-cost, school-based ABA interventions implemented in classrooms have been developed (Eldevik et al., 2006; Foran et al., 2015; Peters-Scheffer et al., 2010; Grindle et al., 2012). The present study investigated whether a low-intensity ABA-based intervention would increase on-task behaviour in a special education classroom, specifically, in children diagnosed with ASD.

The results of the study suggest that students as young as seven years old, diagnosed with ASD can successfully increase their on-task behaviour in the classroom by using a self-monitoring intervention prompted by a device called a MotivAider. This intervention was rated favourably by the teacher and was recommended for other students and teachers.

It is of utmost importance to provide optimum, evidence-based teaching for all students, but also ensure that students thrive socially and feel comfortable in the classroom. Students with intellectual disabilities often have reported feelings of embarrassment, stigmatization and exclusion (Broer, Doyle and Giangreco, 2005). This intervention is an alternative to the overreliance on paraprofessionals in special education classrooms in the UK.

The present study provides evidence to support the use of low-intensity ABA-based teaching as a service delivery in an already existing system; schools. Children diagnosed with ASD are in desperate need for evidence-based interventions in order to decrease the risk for challenging behaviours, and increase socially significant behaviours. They deserve fair, effective and high quality interventions that will help increase their independence and academic performance. Implementing teaching and introducing interventions based on ABA-methods in schools will guarantee that every child has access to the services and support that they need in order to reach their full potential. This in turn, will reduce strain on carers, teachers and societal resources, and improve the quality of life of each child diagnosed with ASD.

This dissertation methodology has been written by a student and is published as an example. See our guide on How to Write a Dissertation Methodology for guidance on writing your own methodology.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Teaching"

Teaching is a profession whereby a teacher will help students to develop their knowledge, skills, and understanding of a certain topic. A teacher will communicate their own knowledge of a subject to their students, and support them in gaining a comprehensive understanding of that subject.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation methodology and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: