Barriers in Referral Pathways for Females at Risk of Familial Breast Cancer

Info: 8777 words (35 pages) Dissertation

Published: 21st Feb 2022

Tagged: MedicineHealthcareCancer

Abstract

Discovering you have breast cancer can be a daunting experiencing for any individual, but not all breast cancer is discovered from identifying a lump. Familial breast cancer is carried through genetic testing when the breast cancer susceptibility gene (BRCA) 1 / 2 is found. An individual who carries the gene may not necessarily develop cancer, but are at a higher risk that those who do not. It can be questioned whether General Practitioners (GPs) have the appropriate knowledge required on the referral process; if the support for both patient and families available is adequate and whether health promotion, campaigns and celebrities have positive influences on patients seeking advice about their concerns. Many have argued that the lack of the GPs knowledge and education can have a negative effect on women who may be at high risk of developing familial breast cancer. Even though certain support is offered for an individual who has been referred for genetic testing, not all individuals feel comfortable to fully seek the support offered to them. Finally, research has shown that the media and celebrities are a powerful way of portraying health issues and encouraging people to check their breast regularly for any changes.

Contents Page

Introduction 5-7

Methodology 8-9

Results 10

Barriers to referrals 11-14

Support for patients attending genetic testing

And family members who may be affected 15-17

Health promotion and education 18-19

Conclusion 20

Reference List 21-31

Appendix 1 32

Appendix 2 33-36

Appendix 3 37-38

Appendix 4 39-40

Appendix 5 41

Introduction

Familial breast cancer can be clarified through genetic testing in the first instance, this gives individual an early option of treatment if they are at risk of developing breast cancer in the future. Despite the National Institute for Health Care and Excellence (NICE) giving guidance on referral pathways, evidence suggests that GPs have gaps in knowledge when it comes to genetics and services provided (Clyman et al, 2007; Rafi et al, 2013).

This assignment will discuss the barriers within referral pathways of identification of females at high risk of familial breast cancer in England, evaluating the support that is given to patients who undertake genetic testing and identifying the impact of campaigns and health promotion have had to raise awareness of familial breast cancer. These have enabled education and have promoted individual to attend GP appointments to seek further information in regards to genetic testing.

This is a topic the author is passionate and particularly interested in as breast cancer has led to premature deaths within the family in recent years. Additionally, the author is eager to specialise in breast cancer care once qualifies and experiences has been gained. Therefore, it is imperative that the author has first-hand knowledge and understanding of the question: “Breast cancer, family history and genetic testing; what are the barriers to genetic testing?”

Cancer can be defined as ‘abnormal cells distributing in an uncontrolled way, with some cancer spreading into different tissues’ (Weinberg, 2013). Cancer begins when there are changes in one cell or within a group of cells (Ruddon, 2007). Cells within a human body produce signals which control when and how much a cell should be divided (Chen and Wong, 2014) if the signals are absent or damaged the cells can grow and multiply too often, forming a lump referred to as a ‘tumour’ or a ‘primary tumour’ when the lump becomes cancerous (Haddad, 2016).

It was estimated that in 2015 there were 2.5 million people within the United Kingdom (UK) living with cancer (Office for National Statistics, ONS, 2017), with the number set to rise to 4 million by 2030 (Maddams, Utley and Moller, 2012). There are approximately over 200 different types of cancer and individuals can be diagnosed with research finding that Breast Cancer is now the most common cancer within the UK (ONS, 2014). It is estimated that 41,200 women are diagnosed with Breast Cancer every year and unfortunately 11,400 women lose their fight against cancer per year (GOV.UK, 2015).

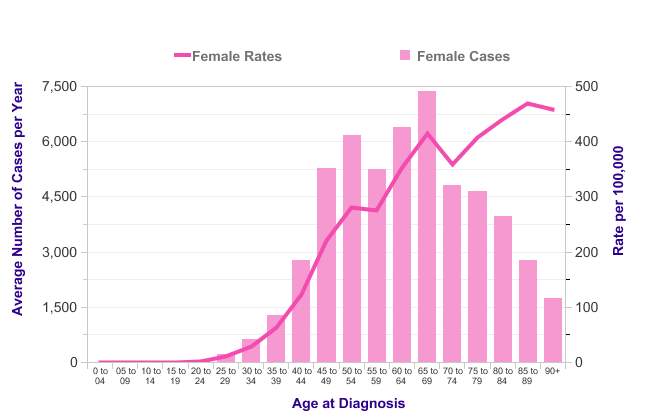

NICE (2011) believe that there are three main factors which can influence the risk of developing Breast Cancer. Firstly: Gender – if you are female you are at a greater risk of developing the disease. Secondly; age – the older you are the greater the risk. Studies have found that 80% of women who are diagnosed with breast cancer are over the age of 50 and most males are over the age of 60 (See appendix 1). Thirdly, family history – although it is not common 5% of diagnosed individuals have inherited the “faulty” BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 gene.

Although more commonly in females, breast cancer can occur in men and women at any age (Nee, 2013). Eccles et al (2015) state that breast cancer is rare within the under 30’s and affects less than one in every 1000 individuals. Regardless of age, Copson et al (2014) believe that an individual should be aware of their options in relation to breast cancer and especially if there is a history of Breast Cancer in the family.

World Health Organisation (WHO, 2017) states “Early detection saves lives”, this has been supported by several cancer charities. Identification of BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 genes allows patients to make a life-saving choice, as well as knowing that they are at an increased risk of developing Breast Cancer (Royal Marsden, 2015). If the tests identify the individual to be a high-risk carrier of BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 genes it can encourage family members to enquire further and educate themselves as well as undertaking genetic tests if the patient meets the criteria (GOV.UK, 2015). However, it is important that the patient understands that if the genetic test is positive it is not an automatic indicator that the individual will have cancer or that it will develop into cancer (Friedenson, 2005). NICE (2017), have set guidelines for GP’s to follow in regards to referring patients who are at risk of Breast Cancer and familial Breast Cancer – referred to as QS12 and CG164.

Methodology

The author has used several electronic resource databases to research ‘Breast Cancer, family history and genetic testing; what are the barriers to genetic testing?’ to determine reliable sources. Badke (2014) state that articles need to be attained from creditable authors. Beins and Beins (2012) believe that for a paper to be creditable it needs to include scholarly sources, be fair and respect the sources used and present information to allow the reader to engage with the context. Macnee and McCabe (2008) agree that by using electronic databases ensures the author that the articles obtained are trustworthy, accurate and reliable, compared to internet searches that lack clarity (Law and MacDermid, 2008).

Databases which were used to help the author gather articles were; CINAHL, MEDLINE and PRO QUEST. To enable creditable papers the author added search limits to narrow the search. Gresham (2016) says enabling search limits allows the author to narrow the focus of the information and relevance. Kotter (2011) expands on Gresham (2016) by stating that the information gained from the database is to set values in which the author has set themselves. The search limits included: academic journals, setting the age of the search to the last 10 years and basing the articles within the UK & Ireland (See appendix 2). Implementing search limits allowed a smaller number of articles which the author could focus on and use accordingly.

Furthermore, the use of key words allowed the search to be narrowed further and more specific (See appendix 2). Kent (2012) puts forward the idea that using key words can improve the result of the initial search as it is tailored to the proposed question. Adams and Lawrence (2014) add that key words are beneficial when narrowing a search, but it can also impair a search. With Watkins (2013) believing that key words should only be used in certain circumstances. In some instances, key words were not used as the author had already found an article without implementing them.

On occasions, if the author chose the articles by reading the title and if it was relevant, the abstract would be explored to get a robust idea of the article.

To gain a substantial understanding the author was also in direct contact with Phil Leonard a genetic counsellor located at the Birmingham Women’s Hospital who was able to answer direct questions and provide fundamental information. Additionally Performa was devised which was reviewed by a lecturer who could confirm it was suitable (See appendix 3). The author also met up with a lecturer and discussed the progress of the assignment on numerous occasions (See appendix 4). This ensured that the author was meeting the proposed deadlines and a timetable was collaborated between the author and the lecturer to work alongside.

Results

By undertaking a database search, it enabled the author to find a number of articles in relation to the three themes that have been identified. A number of limitations were found, as the author wanted to keep the articles UK based. A number of articles outside the UK were found and contained relevant information in relation to the topic. The author also wanted to keep the articles relevant and up to date; therefore a time frame was put into place of articles published within the last 10 years.

From conducting the data base search there was a number of relevant articles found which contained vital information that could be used throughout the assignment. Nevertheless, several articles which were found, five were particularly useful and had information which incorporated all three themes devised. Therefore, they were used throughout the whole assignment (See appendix 2).

Barriers to referrals

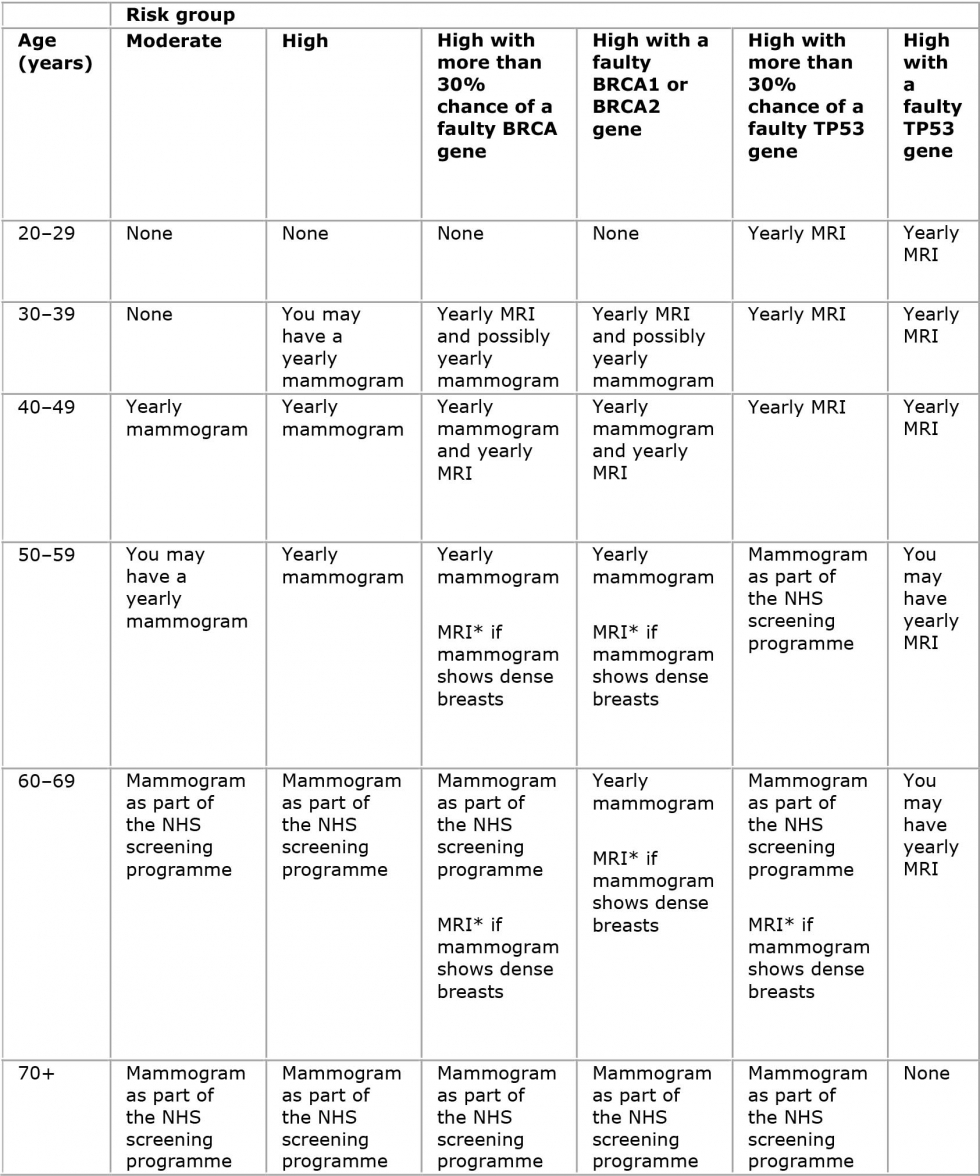

NICE (2011) have made recommendations for GPs to adhere to in relation to familial breast cancer. Indicating whether they need to refer their patients to a genetic centre to get their genes tested for BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 or if they are at a higher risk of developing breast cancer within their life by meeting specific criteria in which NICE has devised. Additionally, NICE recommend different forms of surveillance for women who are considered high risk of developing breast cancer (See appendix 5).

Currently, patients must fill out a family history form which then calculates their possibility of being a BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 carrier. Prior to 2005 all women who were referred were seen in a specialist clinic regardless of whether they completed the form (Hanning et al, 2013). This found that although women did not return their form prior to their appointment there was a higher number of women attending the clinics and having the testing. This was changed to achieve a higher rate of form completion and that a clinic appointment should be arranged. Although this could estimate what risk the patient may be at carrying the BRCA gene (Hanning et al, 2013), it meant that less people were going for the test as it was becoming very time consuming and too daunting.

Foot et al (2010) found that 1 in 20 patients were referred to a specialist service through a GP appointment. However, Duffy (2013) found that thousands of individuals were diagnosed through attending A&E departments rather than being referred to specialist services by their GPs. Research has found that GP surgeries are being offered a large amount of money to cut down the number of patients they refer to specialist services for further investigations due to limited resources and funding available (Campbell, 2015). This has resulted in GP’s being put under enormous amounts of pressure not to refer potential cancerous patients (Dr Loftus, 2010). Therefore, it can be questioned if GPs are adhering to NICE guidelines and referring their patients? Or are they holding back on referrals due to limited resources and funding available?

O’Dowd (2015) argues that the low cancer survival rates within the UK is due to the delay in GP’s referrals for specialist services. Richard Rope the clinical lead for cancer at the Royal College of General Practitioners suggests that referrals are not being dealt with effectively due to limited resources available and the severe shortages of doctors across the UK. Controversially, Clyman et al (2007) believes that it is due to a gap in the knowledge of GP’s when it comes to referring a patient for genetic testing. Supporting Clyman et al (2007) and Richard Rope (2015), Rafi et al (2013) conducted research on the management of people with family history of breast cancer and found that GP’s openly admitted that they lacked knowledge on how to record vital information in regards to referring patients for genetic testing, thus due to not having adequate resources to do so. Sara Hiom of Cancer Research UK states that this is “not good enough”, she believes that GP’s need to do more for their patients so they can have adequate and quick referrals which is required and could result in saving their life. Clyman et al (2007) recommend that genetic education should be implemented within current teaching programmes to ensure newly qualified doctors and nurses are aware.

Research conducted back in 2004 by McCann et al found that GP’s themselves wanted to attend training courses specifically addressed for genetics and genetic testing. This proving they are not confident in that particular area of their profession. The research also found that GP’s felt that referrals in regards to genetic testing is not part of a GP’s role and should be done within the primary care setting. This however, contradicts what Foot et al (2010) believe, as they state that a GP role includes making patient referrals to specialist services. Therefore, it can be difficult to establish where the responsibility lies in regards to whom should make the referrals to the specialist services.

In addition to this, Denmark launched a continuing medical education (CME) programme in early cancer diagnosis in 2012, focusing on enhancing GP’s knowledge of referring patients as well as other aspects of cancer diagnosis. Results found that participating in the CME programme considerably improved their knowledge and understanding on referring patients. Having these results within a country in Europe, it can be asked why hasn’t the UK set up a programme to help GP’s developing their knowledge and understand on referring patients and enhance their chances of surviving or discuss their options if they have the BRCA gene?

Another barrier is that patients who get referred do not always fill out their family history forms primarily due to the lack of knowledge given to them by their own GP’s (Brunstrom et al, 2015). Those who did get referred did not believe that they had enough supporting information in regards to what happened after filling out their family history form and felt they needed help by a professional to fill out the form (Hanning et al, 2014). Therefore, it can be said that education for GP’s is a necessity as they can then educate their patients, which will then enable them to attend appointments. Additionally, GP’s will also be able to support other members of the family who may require genetic testing for genetically related familial disease in the future. Research found by Hanning et al (2013) contradicts what NICE (2011) state as within their recommendations that information should be provided about sources of support as well as the process. It can be judged that some genetic centres are not adhering to NICE recommendations by not providing patient with adequate information at a stressful and anxious time.

Hanning et al (2013) conducted research and found that the proportionate of individuals who did not return their forms were those under the age of 30, who are under the age where surveillance is offered. This could be down to a fear of what the results would show and the lack of forms being sent back within this age group could be due to not knowing what can be done for them in regards to treatment as per NICE guidelines (See appendix 5). In addition to the fear, women did not fill out the form as they felt it was too complicated to finish and family members being unsupportive in helping the individual to complete the forms required. On the other hand, Brunstrom et al (2015) found only encouraging aspects of genetic testing; including positive influences on health and lifestyle choices, women having no regrets of undertaking the test and feeling empowered that they could take action regarding life style choices if they were found to be a carrier of the BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 gene.

The lack of knowledge and understanding from GP’s has had an effect on the detection of the BRCA gene, which could save women’s lives in the future. If GP’s had adequate knowledge on the referral process they would be able to explain to their patients what is required of them when filling out the family history form, if at high risk they can be identified quickly and can make a vital decision about their health. The lack of resources and funding available also has an impact on the number of patients being referred for genetic testing which needs to be addressed.

Support for patients attending genetic testing and family members who may be affected

Genetic support groups commenced in the 1960’s (Chalmers et al, 1996) with breast cancer family history clinics existing since 1986 (Evans et al, 2014). These have developed significantly worldwide offering individuals guidance and support with genetic testing (Crawford and Dubras, 2009). It was developed swiftly in the UK due to the Human and Genome Project (2003) which made advancements in genetic testing technology, resulting in a higher demand of the public requesting an individual risk assessment to see if they were a carrier of the BRCA gene. Within the NICE (2013) familial breast cancer guidelines it recommends that an individual should have at least two pre-sessions of counselling with a genetic counsellor prior to undertaking any tests. This ensures the patient is fully mentally prepared for the process. However, not all individuals decide to participate in the recommended genetic counselling due to them not feeling that support offered is applicable for them and a majority being of an older age (Bakker et al, 2007). Brunstrom et al (2015) found that genetic counselling increased knowledge and awareness about the effects of being a carrier of the BRCA gene. In addition to the awareness, Bakker at al (2007) found that those who participated with genetic counselling found it easier to inform family members of their results as well as deciding promptly what treatment they wanted if tested positive for the BRCA gene. On the other hand, Harris and Ward (2011) found that the impact of genetic counselling has a negative effect on individuals as it changes their lives dramatically and very quickly. Sivell et al (2007) disagree and found that the genetic cancer risk assessments have a positive effect on an individual and causes no harm to them or their lives. Moreover, Bennett et al (2010) believes that it is imperative that individuals as well as their families receive not only appropriate information but also psychological support during the process of genetic testing, this supports NICE (2011) who also highlights the importance of the accessibility to accurate information and psychological support within their guidelines. In saying this, Harris and Ward (2011) found that in some instances individuals who were going through the process of being referred to a genetic service were only given a telephone number which they could contact to gain further information about the process. A number of individuals also found the website inadequate as they could not access information of psychological support. Crawford and Dubras (2010) believe that this is due to effective long term support not always being available and being able to achieve it.

The genetic team have the responsibility to support, provide information and maintain confidentiality for those who are found to be a carrier of the BRCA gene (General Medical Council, 2009). Research has shown there is a split in decisions on whether and individual should pass on information to their family members that they may also be a BRCA gene carrier. Dhennsa et al (2015) found two themes when conducting information; genetic information should be disclosed and having some control over information is desirable. Expanding on theme 1, all participants believed that all relatives have a right to know as they may also be at a potential risk of also being a BRCA carrier. They believed that they had the obligation to inform family members of their own results, which would allow the family member to enquiry about getting their genes tested to see if they are also a carrier of the gene (Harris and Ward, 2011).

However, theme 2 saw that patient’s attitudes changed when asked if they required support in relating their results to family members. Hanning et al (2013) found that this was due to a lack of family support and a lack of contact some individuals had with members of their families, resulting in members of the public being unaware that they could potentially be a carrier of a BRCA gene. Lucassen and Parker (2010) propose that in instances such as those occurring in theme 2, familial genetic information should be available to members of an individual’s family if deemed to be a high – risk carrier of the gene. It can be seen as a very controversial issue because should the genetic team be able to contact family members deemed high risk if the patient declines to inform them about their genetic testing results? As it could potentially save an innocent individuals life. However, can it be argued that as a healthcare professionals you are bound by codes to maintain confidentiality and not disclose any information of your patient.

There is a split decision whether confidentiality should be breeched by just genetic counsellors to ensure that those who may be at a high risk of carrying their BRCA gene should be notified and tested. However, there is a lack of information for those individuals who may be facing genetic testing and feel that there is support there for them.

Health promotion and education

The BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 genes were first identified in 1994 and ever since then there has been ongoing education and health promotion on breast cancer awareness (Harris and Ward, 2011). NICE (2011) recommend strategies to reduce the risk of familial breast cancer and encourage early detection. The services do not provide any recommendations for those under the age of 30 and are at a high risk of developing breast cancer and familial breast cancer (See appendix 5). Therefore, it is imperative that women of all ages have adequate and accurate information regarding this life – threatening disease.

Research conducted by Brunstrom et al (2015) found that by undertaking genetic testing and genetic counselling made women more aware of their breasts and what signs and symptoms they should be mindful of. Which previously they may have ignored or been naïve about. Although this is extremely useful it does not give the education to women who do not undertake the genetic testing and counselling. Although these women do not get the education because they are not at risk of developing familial breast cancer it does not exclude them of being at risk of developing breast cancer at some point in their lives.

Currently, within the UK every October is Breast Cancer awareness month which encourages members of the public to support those affected by breast cancer (Breast Cancer Care, 2017). Over the year’s campaigns have ran effectively such as a “no make-up selfie” and lots of “fun run’s” where you donate money to cancer research or raise money for the charity. Even though this has gained high publicity, it can be questioned whether these campaigns educate women about how to check their breasts and be aware of symptoms that come with breast cancer or is it just to raise money for find a cure or treatment.

A case study has shown that since actress Angelina Jolie announced that she was a carrier of the breast cancer gene and had 87% chance of developing breast cancer. This resulted in the decision to have a double mastectomy to reduce her chances of developing the disease. This has seen an increase of women going to the doctors and enquiring about getting their genes tested for the BRCA gene (Evans et al, 2014). In the UK alone 50% more women got referred to the genetic clinics to see if they were also a carrier of the BRCA gene (Evans et al, 2015). This resulted in the ‘Angelina Jolie effect’ within English speaking countries as it proved to raise awareness for women and some men of all ages (Genomics Education Programme, 2017).

Desai and Jena (2016) state that although celebrities have an immediate effect on individuals in regards to health promotion it does not necessarily mean that everyone takes note of what is being said. This is supported by what Evans et al (2014) found, they state that celebrity profiles have a major influence on the general public but to make it even more effective adequate information needs to be included to assist the general public in their understanding.

There are a number of health promotions and campaigns which occur within the UK throughout the year but there is nothing specific to alert individuals who may be at a high risk of carrying the BRCA gene. Even though the announcement made by Angelina Jolie increased numbers of women seeking information from their GPs, it is important that all women have a clearer understanding of the information published from celebrities about any medical illness or disease.

Conclusion

From the research found it is clear to state that GPs are lacking in knowledge in relation to referring individuals to specialist services, this being due to a lack of education throughout their training. Having the adequate knowledge and education could potentially increase a women’s life span as well as their quality of life as if identified to be a carrier of the BRCA 1 / 2 gene, as decisions can be made earlier regarding their health. However, there are some GPs who are reluctant to further expand their knowledge due to them feeling that referring patients should be done within a primary setting only. So, do not feel that it is necessary to expand their knowledge and education on the referral process. It needs to be clarified where the referral process beings and who has the authority to refer patients who may be at high risk or a carrier of the gene, rather than potential patient’s being made to wait due to GPs being indecisive. Therefore, it can be said that something needs to be implemented in practice to alert GPs of high risk individuals being a BRCA 1 / 2 gene carrier, so they can therefore be referred to specialist services to clarify whether they are indeed a carrier of the BRCA gene. If a system is put in place to alert healthcare professionals that an individual is at high risk of being a BRCA 1 / 2 gene carrier, then a genetic counsellor could contact the patient prior to completing the form and reassure the patient and offer support in filling out the form if it is needed. If approached prior to attending the genetic, allowing the patient to build up a therapeutic relationship being open about their feelings and concerns. If tested positive it can be passed onto immediate family members, who can then enquire about getting their genes tested, preventing unavoidable breast cancer, increase survival rates and promote the importance that if breast cancer is in the family there are options to see if you are a carrier of the gene rather than playing a ‘waiting game’.

Reference List

Adams, K. Lawrence, E. (2014) Research Methods, Statistics and Applications. USA: SAGE Publishers

Badke, W. (2014) Research Strategies: Finding your way through the information fog. 5th Ed. USA: iUniverse

Bakker, K. Krode, H. Rodenhuis, C. Bout, J. Ausems, M. (2007) Barriers to participating in genetic counselling and BRCA testing during primary treatment for breast cancer (Online) Netherlands: Pubmed.gov (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18007146

Beins, B. Beins, A. (2012) Effective Writing in Psychology: Papers, Posters and Presentations. 2nd Ed. West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing

Bennet, P. Parsons, E. Brian, K. Hood, K. (2010) Long – term cohort of women at intermediate risk of familial breast cancer: experience of living at risk. (Online) London: onlinelibrary.wiley.com (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pon.1588/epdf

Breast Cancer Care UK (2017) Support women this Breast Cancer Awareness Month. (Online) London: breastcancercare.org.uk (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: https://www.breastcancercare.org.uk/awareness-month

Brunstrom, K. Murray, A. McAllister, M. (2015) Experiences of Women who underwent predictive BRCA 1 /2 mutation testing before the age of 30. (Online) Cardiff: Journal of Genetic Counselling (Accessed 24th March 2017) Available at: http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=14&sid=842b0e5a-546e-431e-a79e-7940b9068321%40sessionmgr4007&hid=4204&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=112463112&db=rzh

Campbell, D. (2010) GP practices ‘offered rewards’ for not referring patients to hospitals. (Online) London: theguardian.com (Accessed 9th April 2017) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/oct/01/gp-practices-offered-rewards-for-not-referring-patients-to-hospitals

Chalmer, K. Thompson, K. Degner, L (1996) Information, support and communication needs of women with a family history of breast cancer. (Online) Canada: Cancer Nursing (Accessed 23rd March 2017). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8674029

Chen, X. Wong, S. (2014) Cancer Theranostics. London: Elsevier

Clyman, J. Nazir, F. Tarolli, S. Black, E. Lombard, R. Higgins, J. (2007) The Impact of a genetics education program on physician’s knowledge and genetic counselling referral patterns. (Online) New York: Med Teach (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=842b0e5a-546e-431e-a79e-7940b9068321%40sessionmgr4007&hid=4204&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=105835442&db=rzh

Copson, E. Maigham, T. Gerty, S. Eccles, B. Stantin, L. Cutress, R. Altman, D. Durcan, L. Simmonds, P. Jones, L. Trapper, W. Eccles, D. Ethnicity and outcomes of young breast cancer patients in the United Kingdom: the POSH study (Online) Southampton: British Journal of Cancer (Accessed 24th March 2017) Available at: http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=e1bd234e-d215-4830-8a37-ab4c05c980f7%40sessionmgr4010&vid=3&hid=4204

Crawford, G. Dubras, C. (2009) The inaugural meeting for Wessex BRCA carriers. (Online) London: The Newsletter of the British Society for Human Genetics (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: http://cgg2013.bshgconferences.org.uk/media/618530/bshg_newsletter_40.pdf

Desai, S. Jena, A. (2016) Do celebrity endorsements matter? Observational study of BRCA gene testing and mastectomy rates after Angelina Jolie’s New York Times editorial (Online) USA: BMJ Online (Accessed 24th March 2017) Available at: http://www.bmj.com/content/355/bmj.i6357

Dheensa, S. Fenwick, A. Lucassen, A. (2015) ‘Is this knowledge mine and nobody else’s? I don’t feel that’. Patient views about consent, confidentiality and information-sharing in genetic medicine (Online) Southampton: Journal of Medical Ethics (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=16&sid=842b0e5a-546e-431e-a79e-7940b9068321%40sessionmgr4007&hid=4204&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=113446333&db=rzh

Duffy, S (2013) Many cancer patients ‘not referred to specialist by GP’. (Online) London: bbc.co.uk (Accessed 9th April 2017) Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-25274287

Eccles, B. Copson, E. Cutress, R. Maishman, T. Altman, D. Simmonds, P. Gerty, S. Durcan, L. (2015) Family History and Outcome of young patients with breast cancer in the UK (POSH STUDY) (Online) Southampton: Wiley Online Library (Accessed 24th March 2017) Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/bjs.9816/asset/bjs9816.pdf?v=1&t=j0nnexr0&s=e152329a0bda7158d5590efa3f788c579bf209f8

Evans, D. Barwell, J. Eccles, D. Collins, A. Izatt, L. Jacobs, C. Donaldson, A. Brady, A. Cuthbert, A. Harrison, R. Thomas, S. Howell. A. (2014) The Angelina Jolie effect: how high celebrity profile can have a major impact on provision of cancer related services. Manchester: Bio Med Central

Evans, D. Wisely, J. Clancy, T. Lallo, F. Wilson, M. Johnson, R. Duncan, J. Barr, L. Gandhi, A. Howell, A. (2015) Longer term effects of the Angelina Jolie effect: increased risk reducing mastectomy rates in BRCA carriers and other high risk women. Manchester: Bio Med Central

Foot, C. Naylor, C. Imison, C. (2010) The quality of GP diagnosis and referral (Online) London: Kingsfund.org (Accessed 9th April 2017) Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/Diagnosis%20and%20referral.pdf

Friedenson, B. (2005) BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 Pathways ad the Risk of Cancers other than Breast or Ovarian. (Online) USA: Med Gen Med (Accessed 24th March 2017) Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1681605/

General Medical Council (2009) Confidentiality (Online) London: gmc-uk.org (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/confidentiality.asp

Genomics Education Programme (2017) Genomics and the ‘Angelina Jolie effect’. (Online) London: NHS Health Education England (Accessed 24th March 2017) Available at: https://www.genomicseducation.hee.nhs.uk/news/item/325-genomics-and-the-angelina-jolie-effect

Gresham, B. (2016) Concepts of Evidence Based Practice for the Physical Therapist Assistant. Philadelphia: F.A.Davis Company

Haddad, L. (2016) This is Cancer: Everything you need to know, from the waiting room to the bedroom. London: Blackwell Publishing

Hanning, K. Steel, M. Goudie, D. McLeish, L. Dunlop, J. Myring, J. Sullivan, F. Berg, J. Humphris, G. Ozakinci, G. (2013) Why do women not return family history forms when referred to breast cancer genetics services? A mixed – method study (Online) St Andrews: Health Experience (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1111/hex.12166/asset/hex12166.pdf?v=1&t=j1dim5lh&s=08e9150c2b4f5212c9f9ef89b617e625865aaf1a

Harris, J. Ward, S. (2011) A UK collaborative 1 day pilot information and support forum facilitated by a national breast cancer charity and NHS cancer genetic counsellors, for women at high risk, BRCA 1 / 2 carriers and hereditary breast cancer. (Online) London: European Journal of Cancer Care (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=11&sid=842b0e5a-546e-431e-a79e-7940b9068321%40sessionmgr4007&hid=4204&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=104589866&db=rzh

Human Genome Project (2003) History of the Human Genome Project. (Online) USA: genome.gov (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: http://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/Human_Genome/home.shtml

Kent, P. (2012) Search Engine Optimization for Dummies. 5th Ed. USA: Wiley Publishers

Kottler, K. (2011) Excelling in College. Australia: CENGAGE Learning

Law, M. MacDermid, J. (2008) Evidence- based Rehabilitation: A guide to Practice. 2nd Ed. Canada: Slack Incorporated

Loftus, R. (2010) GP practices ‘offered rewards’ for not referring patients to hospitals. (Online) London: theguardian.com (Accessed 9th April 2017) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/oct/01/gp-practices-offered-rewards-for-not-referring-patients-to-hospitals

Lucassen, A. Parker, M. (2010) Confidentiality and sharing genetic information with relatives (Online) Harvard: Harvard Medical School (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(10)60173-0.pdf

Macnee, C. McCabe, S. (2008) Understanding Nursing Research: Using Research in Evidence-based Practice. 2nd Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincot, Williams & Wilkinson Publishing

Maddams, J. Utley, M. Moller, H. (2012) Projections of cancer prevalence in the United Kingdom, 2010-2040 (Online) London: bjc.com (Accessed 18th March 2017) Available at: https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/618604/1/bjc2012366a.pdf

National Institute of Care and Excellence (2016) Breast Cancer (Online) London: NICE.org.uk (Accessed 10th March 2017) Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs12

National Institute of Care and Excellence (2015) Familial breast cancer: classification, care and managing breast cancer and related risks in people with a family history of breast cancer. (Online) London: NICE.org.uk (accessed 10th March 2017) Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg164

Nee, P. (2013) The Key Facts on Breast Cancer: Everything you need to know about breast cancer. USA: Medical Centre

O’Dowd, A. (2015) GP Cancer referral delays may explain UK’s low cancer survival rates. (Online) London: The BMJ (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=7&sid=842b0e5a-546e-431e-a79e-7940b9068321%40sessionmgr4007&hid=4204&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=109794436&db=rzh

Office for National Statistics (2014) 10 most common cancers among males and females. (Online) London: ons.gov (Accessed 18th March 2017) Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105160709/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob1/cancer-statistics-registrations–england–series-mb1-/no–43–2012/info-most-common-cancers.html

Office for National Statistics (2017) Cancer registration statistics, England: First release, 2015 (Online) London: ons.gov (Accessed 18th March 2017) Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/cancerregistrationstatisticsengland/firstrelease2015

Public Health England (2015) Public Health England launches nationwide breast cancer campaign. (Online) London: gov.uk (Accessed 18th March 2017) Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/public-health-england-launches-nationwide-breast-cancer-campaign

Rafi, I. Chan, T. Jubber, I. Tahir, M. De Lusigan, S. (2013) Improving the management of people with a family history of breast cancer in primary care: before and after study of audit-based education. (Online) London: BMC family practice (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=4&sid=842b0e5a-546e-431e-a79e-7940b9068321%40sessionmgr4007&hid=4204&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=104209607&db=rzh

Ruddon, R. (2007) Cancer Biology. 4th Ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Royal Marsden (2015) A Beginner’s guide to BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 (Online) London: NHS Foundation Trust (Accessed 10th March 2017) Available at: https://www.royalmarsden.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/files_trust/beginners-guide-to-brca1-and-brca2.PDF

Sivell, S. Iredale, R. Gray, J. Coles, B. Cancer risk assessment for individuals at risk of familial breast cancer. (Online) USA: US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17443529

Watkins, S. (2013) Lifestyle Writer: How to Write for the Home and Family Market. Winchester: Compass Books

Weinberg, R. (2013). The Biology of Cancer. 2nd Ed. New York: Taylor Francis Group

World Health Organisation (2017) Breast Cancer. (Online) London: WHO.int (Accessed 10th March 2017) Available at: http://www.who.int/cancer/detection/breastcancer/en/

Young, D. McLeish, L. Sullivan, F. Pitkethly, Reis, M. Goudie, D. Vysny, H. Ozakinci, G. Steel, M. (2006) Familial breast cancer: management of ‘lower risk’ referrals. (Online) Scotland: BJCancer (Accessed 23rd March 2017) Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2360713/

Appendices

Appendix 1

Age and breast cancer diagnosis 2012-2014

Cancer Research (2017)

Available at: – http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/breast-cancer/incidence-invasive#heading-One

Appendix 2

| Database | Search Terms | Hits | Keywords | Hits | Inclusion / Exclusion Criteria | Hits | Remaining Articles | Notes | Authors |

| CINAL | Breast Cancer | 778 | Family history and genetics | 325 | 2010 – 2017

Academic Journals |

26 | Down to 26 including:

“Why do women not return family history forms when referred to breast cancer genetic services? A mixed method study” |

This article met the criteria of the proposed question and the themes devised | Hanning, K. Steel, M. Goudie, D. McLeish, L. Dunlop, J. Myring, J. Sullivan, F. Berg, J. Humphris, G. Ozakinci, G |

| PRO Quest | Testing for BRCA 1 / 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2016 – 2017

Academic Journals |

8 | Down to 8 including:

“Experiences of women who underwent predictive BRCA 1 / 2 mutation testing before the age of 30” |

This article will be used for the proposed question and the themes devised | Brunstrom, K. Murray, A. McAllister, M. |

| Medline | BRCA testing | 110 | Genetic counselling | 80 | 2011 – 2017

Academic Journal Peer Reviewed |

70 | Down to 70 including:

“A UK collaborative 1 day information national breast cancer charity and NHS cancer genetic counsellor’s, for women at high risk, BRCA 1 / 2 gene carriers and hereditary breast cancer”. |

This article will be used in the assignment as it meets the criteria for the proposed question and the themes devised | Harris, J. Ward, S. |

| CINAHL | Influences on genetic testing | 48 | Breast Cancer | 12 | 2010 – 2017

Academic Journal Peer Reviewed |

10 | Down to 10 including:

“The Angelina Jolie effect: how high celebrity profile can have a major impact on provision of cancer related services”. |

This article meets the criteria for the proposed question and the themes devised | Evans, D. Barwell, J. Eccles, D. Collins, A. Izatt, L. Jacobs, C. Donaldson, A. Brady, A. Cuthbert, A. Harrison, R. Thomas, S. Howell. A. |

| PRO QUEST | Barriers to genetic testing | 199 | Breast Cancer | 109 | 2010 – 2017

Academic Journal Peer Reviewed |

50 | Down to 50 including: Barriers to participating in genetic counselling and BRCA testing during primary treatment for breast cancer | This article meets the criteria for the proposed question and the themes devised | Bakker, K. Krode, H. Rodenhuis, C. Bout, J. Ausems, M |

| MEDLINE | Breast Cancer | 164 | Genetic Testing | 64 | 2012 – 2017

Academic Journal Peer Reviewed |

39 | Down to 39 including: “Genetic Testing and Counselling Among Patients with Newly Diagnosed Breast Cancer” | This article did not meet the proposed question and the themes devised | Kurian, A. Griffith, A. Hamilton, S. Ward, K. Morrow, M. Katz, S. Jagsi, R. |

| Pro Quest | Support for BRCA 1 / 2 individuals | 143 | Breast Cancer | 59 | 2012 – 2017

Academic Journal Peer Reviewed |

30 | Down to 30 including: “The experience of cancer risk management decision making for BRCA + women”. | This article did not meet the proposed question and the themes devised | Leonarczyk, T |

Appendix 3

Independent Project Summary Form

Section 1 – to be complete by student

| Level | Undergraduate – BNurs (Hons) |

| Working title of project | Breast Cancer, family history and genetic testing: what are the barriers to genetic testing? |

| Brief Outline

Aim/purpose of project: (Include at least 2 references0 How you intend to undertake the project:

|

Breast cancer and statistics – Breast cancer is now the most common type of cancer for females within the UK (Office for National Statistics, 2015) with over 50,000 women each year (Public Health England, 2016) and the number is set to increase with the increasing population (Ashelford, Taylor and Raynsford, 2016). High risk people with familial breast cancer can be identified through genetic testing at regional centres, and offered treatment and options which could reduce their likelihood of developing cancer. Referral to these centres is dependent upon GP’s having an awareness of these issues and NICE guidelines (NICE 164), as there are no formal pathways for identifying individuals at high risk, this is dependent upon health promotion and education to raise awareness. There are also barriers to participating in genetic testing to identify family members at risk (Bakker et al 2007). This assignment will look at these 3 issues and make recommendations for practice to improve pathways for genetic testing, to enable people options to reduce their risk of breast cancer.

CINAHL PROQUEST MEDLINE, Regional genetic testing centres, policy – NICE guidelines and health promotion. Tutorials as agreed with tutor – 4 hours booked. Tuesday and weekend will be allocated to this project. |

Section 2 – to be completed by Supervisor

| Discussed topic and plan, this has mileage to cover the outcomes of the independent project. Structure and research methodology discussed in order to meet LO’s discussed. |

I confirm that that this proposal is a Category 0 (literature based) project and that the student may continue with the proposed project activity described above

Appendix 4

Attendance & Supervision Record

This section is to keep a record of attendance of meetings with your supervisor. You should bring it along to every supervision meeting and hand it in with your final project.

| Date

Location Time |

Topic discussed | Actions suggested | Comments |

| 21/2/17

1hour MC218 |

Area to be researched – focus now on genetic element, access to genetic and support offered | Speak to genetic counsellor

Familiarise with NICE guidance to understand issues relating to treatments offered to younger patients at risk of breast cancer |

See proposal form (Appendix 5) |

| 3/3/17

1 hour MC218 |

Structure identified, referral pathways, health promotion and raising awareness initiatives, support and counselling to testing. Structure with regards to achieving LO’s discussed methodology etc. | Continue with your research of themes, writing and will review further work at next tutorial | |

| 17/3/17

MC218 1 HOUR |

Discussed structure and identified a definite structure. Identified resources to be sued from the library intra loan service and medical/nursing cancer texts. Feedback given on draft work | Structure, reword introduction, to write an abstract, use of medical and nursing cancer texts to support discussion as opposed to just cancer charities, research GP’s knowledge of genetic services and referral pathways and use your literature regarding identifying why patients do not attend these genetic centres. Methodology to be condensed- focus on discussion and themes identified. Request the article you need from library intra library loans. | Please send work done for turnitin by the 24th march please. |

| 24/3/17

MC218 face to face 1 hour |

Discussed draft work done so far, advised proof read and grammar to maximise current work and arguments. Annotated comments emailed. Turnitin reports not yet back – will contact again once back. |

Appendix 5

Breast Cancer Care (2017)

Available at – https://www.breastcancercare.org.uk/sites/default/files/styles/full_width_960_/public/file/pub-risk_groups.jpg?itok=3x-vp7F

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Cancer"

Cancer is a disease in which cells grow or reproduce abnormally or uncontrollably. Cancerous cells have the potential to spread to other areas of the body in a process called metastasis.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: