Community-Based NHS Health Check Outreach Programme Reduces Health Inequalities

Info: 7742 words (31 pages) Dissertation

Published: 22nd Feb 2022

Tagged: NursingHealth and Social Care

Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the effects that the implementation of a community-based outreach health programme check has on the uptake of patients from in deprived areas.

Design: Retrospective cohort study using data collected from 1092 health check performed across a one-year time period.

Setting: The health checks were based in community venues across North, Central and South Manchester clinical commissioning groups.

Participants: Eligible adults were aged between 40–74 years, had no without pre-existing, contraindicated medical condition and were registered with a primary care centre within the catchment area.

Intervention: NHS Health Check: A comprehensive routine cardiovascular screening assessment, with additional provision for behavioural modification and the treatment of new found comorbidities for those at risk.

Results: Of the total eligible population in Manchester across the study period 110194, it was found 7025(6.4%) had a NHS health check, of these 1092(29%) had a community-based outreach check. Attendance was highest in younger females aged 40-45. Most patients were either in a managerial/professional occupation or unemployed. The population at higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) are those coming from a deprived less affluent socio-economic background and these were in highest attendance. Amongst the registered attendees, the checks discovered 129 new cases of hypertension, 64 new cases of type 2 diabetes, the vast majority of patients required an additional form of intervention, be that lifestyle or behaviour.

Conclusion: Overall community-based outreach checks have been shown to be a viable method of delivering intervention to “hard-to-reach” patients of lower socio-economic background.

Introduction

Background/rationale

Despite best efforts, cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the second biggest cause of premature death in the UK from 2014(1), many of these deaths may have been preventable had suitable intervention been initiated early. The persistent issue of CVD causing death and disability in the U.K, continues despite a fall in the mortality over the last 20 years currently affecting around 7 million people in the U.K. A worryingly significant proportion 1 in 4 of these deaths are deemed premature, for those under of age of 75, 25% of men and 17% of women can attribute their cause of death back to CVD (2). The National Health Service (NHS) spent about £6.8 billion on cardiovascular disease in 2012/13(1).

This topic led to the formation of the NHS health check (3) screening programme. Understandably, since its inception in 2009, there has been considerable debate on its efficacy, engagement, and delivery, the overall benefit remains uncertain.

The primary objective of the NHS health check is to reduce the risk of CVD, by way of offering a structured clinical assessment to all adults aged 40-74 years, that meet the eligibility criteria, primarily those without pre-existing CVD diagnosis.

It is understood that prevention is “better than cure”, however health inequalities follow predictable patterns and are passed down through generations(4), thus making an intervention at an early stage crucial. One primary concern that has been raised, is that the ethos of the execution of the NHS health check encourages the uptake of the “worried well” and therefore has little impact in the reduction of these health inequalities. Additionally, concerns have been raised regarding the lack of scientific evidence of the benefits of the health check programme(5, 6). Attendance, on the whole, has been demonstrated to be low in the younger population-under 54 and amongst males. It is highest in the “white British” population across both sex groups(7-9), and for those in higher socio-economic groups.

It has been demonstrated that a traditional General Practitioner (G.P) health check, is not capturing enough of the disadvantaged population and that a hmore collaborative effort must be made to target those who would receive the greatest benefit from a health check(10).

One key link that has been shown is that CVD risk is intrinsically linked to the level of deprivation, consistently those in the most deprived decile are at much higher risk, on average the under 75 mortality rates for CVD is 105 per 100,000 when compared to 58 per 100,000 in the least deprived decile recorded between 2013-2015(11).

Importantly variable results have been published when examining the influence of deprivation on the rate of uptake for NHS health checks, with historical reporting that high deprivation is linked to low uptake(12), and that living in less-deprived areas is correlated with higher uptake(13) (14).

This is a major factor in the reasoning behind the establishment of community-based outreach services, that focus on capturing deprived population and providing a comprehensive CVD assessment.

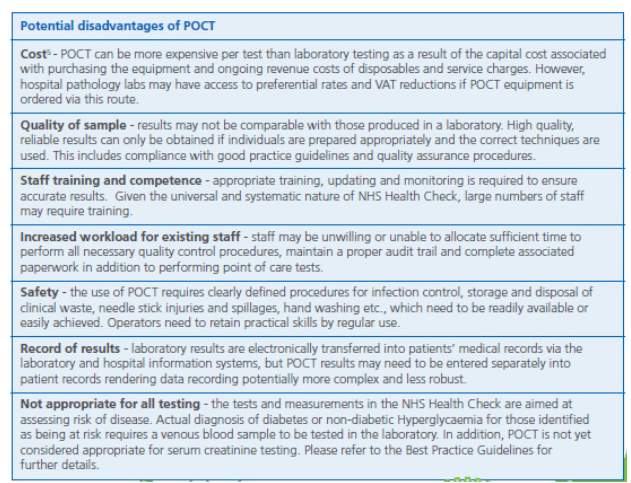

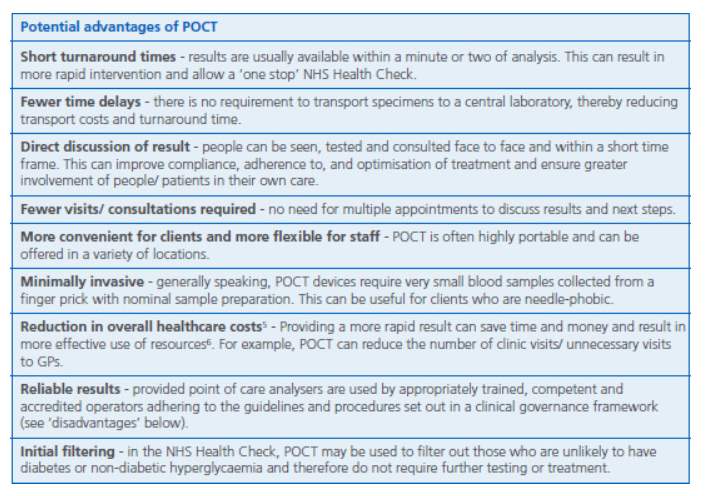

Greater Manchester was one of the first to trial a Health Bus from 2009-2015, performing walk in, no appointment required NHS health checks in areas of high socio-economic deprivation, using near patient testing equipment to give on-the-spot blood test results. Despite its attractiveness, the health bus was, unfortunately, decommissioned due to increasing costs of maintenance. From this, a community-based NHS outreach programme evolved, using the same equipment in the community, still with the same aim of targeting areas of highest socioeconomic need, this time performing health checks within local centres.

It has been hypothesised that by specifically targeting areas of known deprivation, using a service that has minimised barriers for engagement, allows for an increase in the uptake of those who would usually abstain from a traditional primary care based check, these patients are also those in more need of a primary intervention post check and for whom the service must isolate.

Objectives

This retrospective cohort study examines the role of a community-based outreach programme designed to reduce health inequalities across Manchester Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), using data that had been collected across the financial year.

The study’s overall aim was to investigate the effectiveness of providing community-based health checks, how these results compare to national statistics and if the service is being marketed effectively. Specific objectives were:

- To understand importance of providing a community-based outreach check, in areas of known high socio-economic deprivation and how this acts to reduce health inequalities.

- To examine, the demographic of who is having the health check and their overall state of health, how this compares to current statistics across England.

- To assess, the significance of deprivation score in relation to eventual uptake of health check

- To explore, how the service can be developed further.

Methods

This report has been designed to correspond with the STROBE recommendations that has been outlined for that of observational studies(15).

Dates

The community outreach intervention scheme was aimed to provide a structured CVD assessment within the context of local centres, allowing for ease of access and point of care testing. The sample length ran from 1st April 16 -30th March 17.

Method of selection

The service ran as a partnership between Manchester City Council and the NHS, in particular, was coordinated by a primary care practice based in Manchester. Uptake was through several different methods; primary care centres were requested to participate in advance when the service was within their catchment area, their patients were invited via postal service for those that met the eligibility criteria with a description of available time and location, other methods included; opportunistic offerings at location, poster advertisement was used this included canvasing of flyers and postal leaflets.

The service has no appointments and primarily runs as a walk in centre. Patients are excluded if their primary care practice lies outside of the catchment area and if they are diagnosed with a contraindicated pre-existing medical condition as expressed by the Department of Health, such conditions include; pre-existing vascular disease including hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, stroke or transient ischaemic attack, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, CKD, familial hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and those who are already prescribed a statin(16).

Patients were then followed up either in primary care centres or through additional health and wellbeing services as appropriate, no further follow-up was provided by the outreach health check service.

Location

The nature of the community-based outreach checks allows the service to have the freedom to be set up across a variety of centres. These locations included: libraries, leisure Centres, swimming baths, religious centres, town halls, art galleries, youth centres and memorial halls. The setting of each venue is specifically targeted in advance with the aim of providing the maximum uptake, this is achieved by deliberate discussion with local contacts involved in the running of each venue and their knowledge of the area itself.

Data Source

All data was anonymised and collated routinely as part of the full NHS health check. The checks are performed on mobile tablets, using PharmOutcomes a web-based system, which logs and produces an immediate assessment report for each patient. This report provides the results clearly, with added explanation in layman’s terminology. This data enables suitable action to be taken which has been demonstrated to improve outcomes(17). Using PharmOutcomes, assessment reports of the service were tailor generated to suit the needs of this report.

The system also generates a report which is sent to the patient’s G.P containing the results and read codes, additionally, a second notification is also sent if abnormal results are inputted. The data that is stored includes the patient’s demographic information, medical history, family history, point of care test (POCT) results, the method of referral, occupational status, an indication of signposting intervention and referral to G.P status.

Outcomes

The principal outcome of measure was the overall uptake of the community-based outreach check.

Exposure

The level of overall deprivation as defined by the index of multiple deprivation score 2015*

Predictor

Historical data that has reported non-attendance in areas of high deprivation* (ADD source)

Potential cofounder

***

Effect modifying

Time constraints, previous attendance to health check, access to the service , pre-existing medical condtion, attitude towards the health check.

The patient data for those that attended the NHS health check were stratified into the following categories; age, sex, ethnic group as determined by the Office of National Statistics categories(18).

Patients were also stratified into deprivation deciles from 1 being most deprived to 10 being least, using data collected from the Indices of Deprivation (IMD) 2015(19), which is based on seven different measures: Income Deprivation, Employment Deprivation, Education, Skills and Training Deprivation, Health Deprivation and Disability, Crime, Barriers to Housing and Services and Living Environment Deprivation. The IMD gives a set of comparative measures of deprivation for small areas (Lower-Layer Super Output Areas).

All additional health outcomes were collected in accordance with the NHS health check best clinical guidance (16) these include: smoking status, occupational Status, family history of coronary heart disease, body mass index (BMI), lipid profiling, blood pressure, pulse rhythm, physical activity assessment, alcohol risk assessment, diabetic risk assessment. The QRISK®2 engine(20) was used to calculate the individual’s 10-year risk of CVD in line with the National Institute for Health And Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommendations.

All efforts to reduce bias were undertaken observer bias was reduced by providing standardised training to assessors, a structured clinical assessment template and regular independent inspection of all testing equipment. Overall trends and patterns were assessed comparing to available U.K national statistics to reduce the effects of any outliers recorded.

The author of the report was previously a member of the team involved in performing community outreach checks, this enables a first-hand insight into the lack of bias in the selection of patients other than that which is consistent with the strategy of the overall project. This also provides a valuable understanding into the current management and organisation of an external provider of health checks based within the community.

There will always remain a concern of reporter bias, but nevertheless the author is now distant enough from the project and its workings that they will remain impartial throughout, with the report being independent of the project itself and the report being externally moderated.

The data was analysed using Minitab Express (Version 1.5.0). Pearson correlation testing analysing the link between IMD and uptake of the community-based health check was used.

Results

Demographic Analysis

A total of 1092 NHS health checks were performed by the community-based outreach programme in the year April 2016 to April 2017. The community-based health check represented a significant 29% of the total number of health checks performed in Manchester across the time period (see Figure 1). The total number of checks represented 6.4% (7025) uptake of the total eligible population in Manchester (110194).

The graph (X) demonstrates the influence that gender has on the uptake of the health checks, with the community NHS outreach check, the majority 55% of the attendees being female.

Graph (X) shows the age profile of the attendees in the community-based NHS outreach check during the yearlong study period. Those that were eligible 21% were in the age groups 40-45 and 45-49, 20% were in the group 50-54, 15 % were in the group 55-59, 9% in the age groups 60-64 and 65-69 and 5% in the age group 70-74. These results show a shift in the age profile with a higher turnout of younger attendees.

The following details give the ethnic breakdown of attendees in descending percentage order: White (British, Irish, other white background) 59.4%, Asians (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Chinese other Asian) 20.6%, Black (African, Caribbean, other black background) 12.23%, Arab 3.5%, Mixed 2.4%, Any other ethnic group 1.0% and Not stated 0.92%.

Attendees were categorised according to their occupational status; this is demonstrated by graph (X) the following definitions were used for each:

- Unemployed- An attendee is classified as long-term unemployed if they have been unemployed for one year, otherwise use previous employment.

- Home Carer Looking after children, family or home.

- Managerial and Professional- accountant, artist, civil/mechanical engineer, medical practitioner, musician, nurse, police office (sergeant or above), physiotherapist, scientist, social Professional worker, software engineer, solicitor

- Intermediate- call centre agent, clerical worker, nursery auxiliary, office clerk, secretary

- Routine and Manual- Electrician, fitter, gardener, inspector, plumber, printer, train driver, tool maker, bar staff, caretaker, catering assistant, cleaner, farm worker, HGV driver, labourer, machine operator, messenger

- Student

Data collected for the community-based outreach check showed that 18% of all attendees were unemployed, this was the second largest group having health checks, only behind the managerial and professional roles which represented 33% of the total number of community outreach checks performed.

Method of Referral

The approach to referral had a pronounced effect on the subsequent uptake of the community outreach check (Fig(x)). Patients referred to the service through a letter by the GP had the highest uptake 45.2%(494), whilst the lowest uptake was those who had received a postal invitation. A significant 29.4%(321) attendees were offered opportunistic appointments.

Risk Factor Analysis

Table(X) presents the characteristics associated with CVD and the proportion of patients identified during the community outreach check as having one or more of these risk factors. Importantly most patients received some form of intervention, these included discussion around ways to reduced modifiable risk factors, referral to additional services such as smoking cessation, weight management or referral back to primary care centres or referral to hospital in cases of severe hypertension. The most common reasons for referral back to primary care were cholesterol 84.6%, BMI 80.9% and physical activity 87.5%. A further primary care intervention was needed in 30.5% of patients who received an outreach health check, therefore, most patients did not require additional G.P follow up and most intervention was dealt with through the services provided by the outreach team.

Most patients were non-smokers (75.3%) and drank no alcohol (46.7%) or had an audit-C score(21) of

BMI testing revealed that 70% of patients tested had a BMI of greater than 25, with 45% having a BMI of 25-30, 19% 30-35, 6% 35-40 and 0.3% with a BMI of over 40.

The majority of attendees (77 %) had a low CVD risk under as calculated by Qrisk2, 20% had a medium risk, 4% had a high risk and 0.6% were defined as having a very high.

Link between IMD and uptake of Health Checks

One of the key areas for investigation was regarding if there was a link between English indices of deprivation 2015(19) with the uptake of the community outreach NHS health checks across Manchester.

All patients who undertook a community outreach health check had their postcode analysed and grouped into IMD decile from 1-10 with 1 being most deprived 10 being least deprived.

Using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, we can see a clear negative linear trend between deprivation decile and numbers of community outreach health check performed. This trend was significant Pearson correlation of Number of Patients and Index of Multiple Deprivation = -0.972993 with a P-Value =

Discussion

The key objective of this study was to investigate the importance of community-based outreach check programme in the reduction of health inequalities. Therefore, a concentrated effort has been made on ways to combat these health inequalities. One such service is the use of a community outreach health check, as far there has been little-reported information on the outcomes of such a service.

The fundamental advantage of a mobile service is that it allows for ease of deployment in areas where uptake is known to be low, with the aim is to gather that missing “hard-to-reach” population. The service had a specific target population of those in the highest IMD deprivation decile, which are known to be at the highest risk of CVD.

Uptake of health checks in the U.K is 53.2%(22) this is vastly different from the 75% uptake originally proposed when the NHS health check was first launched. In Manchester, currently, the uptake of the health check programme is 52.9%(23), just lower than the up-to-date U.K average.

What is already known on this topic

As it stands, there are few examples of literature surrounding a community-based mobile outreach health check service.

One such study reporting uptake of community-based simplified health checks in Stoke-On-Trent demonstrated that opportunistic community outreach programmes are successful in areas of high deprivation, being a prompt for members of the public who usually abstain from general practice(13).

A similar study in County Durham using lay health trainers to provide a community-based health check service emerged to be successful in terms of engaging with men, younger age groups and those living in socio-economically disadvantaged areas(24).

Through both studies, it has also been shown that non-clinicians such as those who deliver a community -based outreach check are shown to be favourable with members of the public being more open and honest, as they find a non-clinician more relatable, understandable and non-intimidating(13, 24).

Using the Health Belief Model(25), the reasoning behind the strong level of uptake in community-based health checks can be predicted. By placement of a health screening service in an area of high public footfall e.g. supermarket, introduces a component of surprise, which acts a cue to action, this initial surprise then acts as a catalyst to raise the issue of the patients own susceptibility and by targeting at somewhere they regularly attend makes this concern more personal and directed. Various examples have been used to act as cues to action with varying effect the use of including the use of postal invites with the question “if you put the enclosed string around your waist, is it too short?” (26), acting as a visual prompt for their weight. Placing health checks in an area frequently inhabited, by attendee’s acts as a similar visual prompt.

Using succinct explanation by members of staff of the service allows the patient to see the perceived benefit of the check and the severity of not having a check performed. **

Through making it easier and more convenient for attendees to have a check performed, allows for a reduction of barriers to having a health check when compared to those in a traditional G.P setting. **A similar concept of employing health checks in community pharmacies gives a series of results comparable with the community-based outreach check in Manchester and distinct from national statistics. One such study in Birmingham showed that the delivery of a one-stop cardiovascular risk assessment was feasible with 23 urban U.K pharmacies between 1 June 2007 and 31 March 2008 compiling results from 1141 people. It revealed a male dominance (60:40), with a high uptake from those in the most deprived deciles and those of Black or Asian communities were also well represented. It was noted the role of a pharmacy in identifying and managing the workload of around 30% of clients who undertook CVD assessments within the pharmacy setting with the remaining 70% requiring additional intervention through G.P service(26).

What this study adds

Performing checks in a primary care setting gives numerous benefits, being able to access an entire register of eligible patients for checks provides a continual influx of patients, additionally 85% of the population will at some point during a five-year period access health care under their GP. Relationships are already most likely to be well established and can be a positive motivation tool.

However primary care centres being commissioned to deliver a structured cardiovascular risk assessment has in itself inherent issues, with its ability to bring “hard-to-reach” patients through the door, who are in the most need of intervention and therefore the role of external providers must be considered.

This study reveals a community-based outreach check, can produce substantial numbers of attendees 27.9% of all checks performed in Manchester during the financial year 2016-2017 were through this avenue and is, therefore, a viable method, provided suitable resources are available. ***

Demographic Breakdown

Age

One of the biggest concerns regarding the health check programme is the age profile of attendees with the age most frequently attended group being between the age of 60-74(27), during our study we found evidence that did not support the same conclusion with the same age range only accounting for 23.7% of the total attendees with the most frequently visited group being within the age range 40-44. This tendency towards the younger attendees is a positive predictor as we know they are a frequently under-represented group (add source).

The importance of early intervention is well documented (add source), therefore it becomes crucial that the health check is targeted and delivered appropriately. By acting early, diseases can be detected and treatment initiated quickly improving outcomes, additionally, intervention can become routine and the long-term risk modifiable factors can be reduced.

Using a considered selection of venue allows for a more reliable and consistent uptake of the target attendees. By targeting areas known to have a higher density of younger individuals the service can be tailored to suit the demographic that is required.

Sex

It has become apparent during the 8 years since the inception the health check that there are considerable gender differences with regards to a female dominance *add info*, this continued into our findings with females were more likely to attend, however, the gender gap was down to approx. 10%.

Males are known to be at a higher risk of developing CVD disease than females with women developing CVD disease up to 10 years later than males and are three times more likely to suffer a myocardial infarct than women(1).

Therefore, a concerted effort must be made in order to attract more male attendees across all methods of performing a health check. ***

Occupational status

Method of referral

An important factor that increases the popularity of the community-based outreach check is the convenience factor, this has been reported as a big influence on subsequent uptake of health check(17), by having a mobile no appointment required service with the addition of opportunistic appointments being offered, attendees do not need to factor time out of their schedule that may have previously limited their ability to attend a traditional G.P setting.

Importantly the biggest proportion of uptake was through postal service contrary to other studies (8). By inviting the patient through their own G.P service, giving them flexibility and drop in times, all acted to improve uptake. Considerable variability in letter quality was delivered despite a clear template being available, with some lacking detail, not stating eligibility criteria, correct times and location of the service, unsurprising the G.P services that had the highest uptake were those where the letter quality was high.

It has been demonstrated how direct verbal engagement with the public is known to increase uptake(8) with people being unlikely to attend unless they have been approached(17). Although the majority attended though postal invitation a significant proportion of patients who received a health check were after an opportunistic appointment was offered, this represented 29.4% of all checks performed in the community outreach programme.

Continued effort must be made to give a clear layman description of what the purpose of CVD assessment, its risk scoring is as this generates confusion amongst attendees(17), from the onset this would be beneficial if expressed in the invitation letter coherently.

By hosting a health check in a convenient, non-clinical environment encourages a perceived choice of whether to engage with the service or not, this acts as a further prompt to start the thought process regarding the patient’s own health and supports engagement with the programme(13).***

IMD+ UPTAKE

A key area of interest was surrounding the overall link between deprivation and the uptake of the outreach health check in Manchester. It has been reported that the deprived population are frequently under-represented group when it comes to health checks, sadly this population are the group that would most benefit from a check (10). By keeping the service targeted at the deprived population, the outreach programme aims to reduce those health inequalities.

“The IMD 2015 ranks Manchester as England’s fifth most deprived local authority, Manchester has been ranked as first in the rank of the proportion of LSOAs that are in the most deprived 10% nationally in the Health Deprivation and Disability domain. The health domain has been the largest factor in keeping Manchester’s position in the top five most deprived in the IMD, ranking Manchester 2nd in the rank of average score and 1st in the rank of the proportion of LSOAs that are in the most deprived 10% nationally. This domain has a weighting of 13.5% in the IMD(28).

To investigate if the outreach health check was capturing the target population desired, a comparison between uptake and IMD decile was undertaken. A clear significant linear trend can be seen as deprivation increases the number of health checks performed increases proportionally (GraphX).

The implications for practice is that for areas of high deprivation with a low uptake of health checks, an outreach community-based health check can prove a viable service.

Risk Factor

Most patients received a form of intervention when the undertook a health check. Health care assistants were trained to give appropriate advice on lifestyle and diet modifications that can be undertaken when results were not satisfactory, but not in the range a referral back to the G.P was required.

Our study revealed that most patients were non-smokers and drank far less that the maximum weekly recommended intake, these findings were unusual for an area of such high deprivation and were different to what was expected. **

In the UK, obesity is on the rise for both men and women, since 1993 up to 2011 the proportions that were overweight has remained (approximately 40% men and 30% for women). However, alarming there has been a significant elevation in the proportions of the public that are obese. In men, the percentage of obese in 1993 was 13.2% which has grown to 23.6% in 2011 for men and from 16.4% to 25.9% in women. The overall percentage increase of the public with a BMI of 25+ was 57.6% to 65.0% in men and from 48.6% to 58.4% across the time period (29). In 2015 over a quarter of adults (27% of men and women) were obese. An additional 41% of men and 31% of women were overweight (30).

Therefore, it is unsurprising that 70.1% of patients had a BMI of greater than 25, it has long since been established the link between obesity and the increased risk of CVD diseases(31), a continued effort must be made to educate individuals and signpost to additional services and appropriate diet and lifestyle modifications.

Well over a half of all adults in England have a total cholesterol above 5mmol/L, however in 2013 300 million cholesterol lowering prescriptions were issued to treat CVD (32). Over study revealed the average total cholesterol was 4.88 with an average HDL of 1.6. Whilst these statistics appear promising over 84.6% required additional intervention with regards to their cholesterol, be that further education or referral showing the continued need for time in an appointment to provide a comprehensive service which addresses all patients concerns.

Hypertension is the largest prevalence condition reported on the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) between April 2015 to March 2016 with a rate of 13.8% (7.9million)(3). The mean blood pressure for the group undergoing the community-based check was 123/78mmHg, with 12.1% of patients requiring referral to GP or immediate blood pressure treatment in hospital, this is comparable to****. It is worth noting in Manchester the prevalence rates of hypertension are lower than the national average with hypertension being defined as a blood pressure reading above 150/90mmHg, with Central Manchester prevalence of 9.1%, North Manchester 11.4% and South Manchester 11.1%(33).

Diabetes mellitus (over the age of 17) has a current U.K prevalence rate of 6.5%(3). In Manchester, the prevalence rates vary across the CCG areas. The highest prevalence is in North Manchester with 7.0%, Central Manchester 6.0%, the lowest prevalence area is South Manchester with 5.9%(33). The study found 51.5% of patients required an additional intervention of some kind regarding their blood sugar levels, with intervention being classed as discussion over ways to reduce sugar intake, or as in the case of 6.1% of the 51.5% of patients a referral to the G.P for HbA1c outside the reference ranges. The results demonstrate a similar prevalence rate to diabetes register in primary care. **

Significantly virtually all patients required intervention regarding levels physical activity, with their activity score being less than the recommended weekly 150 minutes of cardiovascular exercise per week. **

Limitations of the Study

This study has examined data for a single year for a very specific service targeted on a subset of the population, the generalisability and application, therefore, could be limited to certain locations. The service is not stand alone and does not eliminate the need for G.P based NHS health checks but acts as an adjunct. **

The study did not include cost-benefit analysis, with the community outreach checks requiring additional costs when compared to a traditional primary care based check. **

Additionally, the risk factor results did not reveal a significant increase in features known to increase the risk of developing CVD that are associated with living in an area of high deprivation. This is likely to be due to the fact that most patients were in a younger age range and that given time this conditions would have developed or progressed further and their risk would of CVD would of increased. Reaching these people early before the development of CVD is a great strength of the service as the interventions offered should prevent these people from ever developing CVD. However, it would require very long term follow up to confirm if this is the case. **

A limitation of this study revolves around follow-up, individual outcomes post check requires additional research comparing to national and regional statistics. Having longitudinal data would assist in the understanding of the patients overall long-term health outcome and if deprivation has an influence.

Further Service Development

An area that this NHS health check programme/service has recently incorporated is the integration with Buzz an additional NHS health and wellbeing service run in Manchester. From the health check, attendees are encouraged to spend time on a personalised, holistic one to one basis with the team to enable individuals to improve physical, mental health and wellbeing by promoting self-care and personal resilience. By applying a broader more holistic approach, that does not only focus on lifestyle but also behavioural patterns decreases the “lifestyle drift” that results in constricted interventions, that are acknowledged to be ineffective(34, 35).

The team has local knowledge of services in the area that can be recommended to patients on an appropriate basis for their own objectives. The ability to form immediate succinct action plans that are relevant to the outcome of the health check, create a more positive outlook and set realistic targets with suitable follow-up is known to increase compliance rates. **

Conclusion

In conclusion, health inequalities remain prolific in England and bring social injustice and suffering to many. The continued effect of differences in the standard of health, wellbeing and living due to socio-economic status, have become exceedingly avoidable with the work being undertaken with services such as outreach health check programmes, however, work remains to reduce these inequalities further. The unfortunate graded correlation between the richest in society and the poorest in society is evident, the more affluent higher social position a person is, the healthier they tend to be.

The advantages of using point of care “one-stop” testing system are numerous. Using direct discussion of a patient’s results within the context of the health check, person to person has a shorter timeframe, increases compliance by providing a more personal experience to attendees(36). Using an external service provider to give health checks reduces the time constraints that is inherent in general practice, this has the benefit of being able to spend additional time with patients and the production of more individualised management plan known to give better outcomes post check(37). This also acts to reduce the burden in general practice, as the health check acts as an initial screen so only patients in need of additional intervention are being referred. The importance of health education is not to be mislaid, with many patients using the health check as a platform to assess their general health and wellbeing to make suitable steps to improve their own overall health.

In 2010 The Marmot report was published(38) designed to reduce health inequalities, it laid out six main policy objectives two of which are applicable and have been the reasoning behind providing health checks in a community outreach setting these include:

- Create and develop healthy and sustainable places and communities

- Strengthen the role and effect of the prevention of ill health: prioritise investment across government to reduce the social gradient

The report also revealed some worrying points “In England, people living in the poorest neighbourhoods will, on average, die seven years earlier than people living in the richest. Even more disturbingly, there is a greater variation in the length of time people can expect to live in good health (their health expectancy). For example, the average difference in disability-free life expectancy is 17 years). In other words, people in poorer areas not only die sooner but spend more of their shorter lives with a disability.

This study revealed providing outreach health checks that are embedded within a community, can be a viable method for a distinct set of circumstances such as targeting individuals in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation and can generate sufficient numbers of attendees. Contrary to current studies whereby the population are older, more affluent and with the highest risk categories of patients least likely to attended (39), the use of an alternative model that is specific in its approach, to a “hard-to-reach” population more in need of intervention allows for an more effective service better suited to providing health checks to those that would receive the greatest overall improvement in their health and wellbeing to those most at risk of developing cardiovascular disease.

Bibliography and References

1. Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Williams J, Rayner M, Townsend N. The epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in the UK 2014. Heart. 2015;101:1182-9.

2. Waterall J. Getting serious about prevention. Nurs Stand. 2016;31(8):26-7.

3. Primary Care Domain ND. Quality and Outcomes Framework – Prevalence, Achievements and Exceptions Report. 2016;2.

4. NHS England. NHS five year forward view.

5. McCartney M. NHS Health Check betrays the ethos of public health. BMJ. 2014;349:g4752.

6. McCartney M. Where’s the evidence for NHS health checks? BMJ. 2013;347:f5834.

7. Cook EJ, Sharp C, Randhawa G, Guppy A, Gangotra R, Cox J. Who uses NHS health checks? Investigating the impact of ethnicity and gender and method of invitation on uptake of NHS health checks. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2016;15(1):13.

8. Gidlow C, Ellis N, Randall J, Cowap L, Smith G, Iqbal Z, et al. Method of invitation and geographical proximity as predictors of NHS Health Check uptake. J Public Health (Oxf). 2015;37(2):195-201.

9. Dalton ARH, Bottle A, Okoro C, Majeed A, Millett C. Uptake of the NHS Health Checks programme in a deprived, culturally diverse setting: cross-sectional study. Journal of Public Health. 2011;33(3):422-9.

10. Attwood S, Morton K, Sutton S. Exploring equity in uptake of the NHS Health Check and a nested physical activity intervention trial. J Public Health (Oxf). 2016;38(3):560-8.

11. (PHE) P. Public Health Outcomes Framework.

12. Thorogood M, Coulter A, Jones L, Yudkin P, Muir J, Mant D. Factors affecting response to an invitation to attend for a health check. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1993;47(3):224-8.

13. Gidlow CJ, Ellis NJ. Opportunistic community-based health checks. Public Health. 2014;128(6):582-4.

14. Artac M, Dalton AR, Majeed A, Car J, Huckvale K, Millett C. Uptake of the NHS Health Check programme in an urban setting. Fam Pract. 2013;30(4):426-35.

15. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344-9.

16. England PH. NHS Health Check Best Practice Guidance 2017.

17. Perry C, Thurston M, Alford S, Cushing J, Panter L. The NHS health check programme in England: a qualitative study. Health Promot Int. 2016;31(1):106-15.

18. Statistics OfN. Presentation of Ethnic Group Data. 2017.

19. Government DfCaL. English indices of deprivation 2015. 2015.

20. QRisk 2. 2016.

21. Centre AL. AUDIT – C – Latest Resources – Resources 2017.

22. (PHE) P. Public Health Profiles. 2017.

23. England PH. NHS Health Check Data Manchester. 2017.

24. Visram S, Carr SM, Geddes L. Can lay health trainers increase uptake of NHS Health Checks in hard-to-reach populations? A mixed-method pilot evaluation. Journal of Public Health. 2015;37(2):226-33.

25. Hochbaum G, Rosenstock I, Kegels S. Health belief model. United States Public Health Service. 1952.

26. Richardson G, van Woerden HC, Morgan L, Edwards R, Harries M, Hancock E, et al. Healthy hearts–a community-based primary prevention programme to reduce coronary heart disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2008;8:18.

27. Robson J, Dostal I, Sheikh A, Eldridge S, Madurasinghe V, Griffiths C, et al. The NHS Health Check in England: an evaluation of the first 4 years. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e008840.

28. Bullen E. A Briefing Note on Manchester’s relative level of deprivation using measures produced by DCLG, including the Index of Multiple Deprivation. Manchester City Council. 2015.

29. Health and Social Care Information Centre LS. Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet: England. 2013;2.

30. Health and Social Care Information Centre LS. Health Survery for England 2015: Health, social care and lifestyles. National Statistics 2015.

31. Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, Hong Y, Stern JS, Pi-Sunyer FX, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2006;113(6):898-918.

32. H M. Key facts & figures | Expert advice from HEART UK. 2017.

33. (PHE) P. Healthier Lives – Practice List. 2016.

34. Vallgarda S. Why the concept ”lifestyle diseases” should be avoided. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7):773-5.

35. Hunter DJ, Popay J, Tannahill C, Whitehead M. Getting to grips with health inequalities at last? BMJ. 2010;340.

36. Varvel M. Role of POCT in NHS Health Check

37. Ismail H, Atkin K. The NHS Health Check programme: insights from a qualitative study of patients. Health Expect. 2016;19(2):345-55.

38. Marmot M, Atkinson T, Bell J, Black C, Broadfoot P, Cumberlege J, et al. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: The Marmot Review. 2010.

39. Cochrane T, Gidlow CJ, Kumar J, Mawby Y, Iqbal Z, Chambers RM. Cross-sectional review of the response and treatment uptake from the NHS Health Checks programme in Stoke on Trent. J Public Health (Oxf). 2013;35(1):92-8.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Health and Social Care"

Health and Social Care is the term used to describe care given to vulnerable people and those with medical conditions or suffering from ill health. Health and Social Care can be provided within the community, hospitals, and other related settings such as health centres.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: