Can the Doctrine of Joint Enterprise be Reconciled with Racial Justice?

Info: 18733 words (75 pages) Dissertation

Published: 1st Mar 2022

Tagged: CriminologyCriminal LawEquality

Table of Contents

- Introduction…………………………………………………….4

- Context: The Re-Emergence of Collective Punishment……..6

- Doctrinal and Theoretical Analysis: Joint Enterprise Doctrine, Anti-Gang Policy, and Race………………………11

- History, Definitions and Labels…………………………11

- Dimensions of Joint Enterprise……………………..11

- General and Parasitic Accessorial Liability…………14

- A Historical Account of the Doctrine………………16

- Theoretical Framework: Collective vs. Individual Responsibility……………………………………………20

- From Myth-Making to Policy-Making………………….27

- History, Definitions and Labels…………………………11

- Mapping Out Collective Intention and Moral Agency in Multi-Agent Cases: Redefining the Gang and Restricting the Dragnet………………………………………………………39

- Recapitulating and Way Forward………………………39

- Mapping Out Collective Responsibility………………..42

- Bratman’s Template of Collective Action………………45

- The Ontology of The Gang……………………………..49

- Conclusions: Juxtaposing, Comparing and Contrasting..54

- Policy Recommendations and Implications for BAME Groups…………………………………………………..56

- Conclusion……………………………………………………57

- Bibliography………………………………………………….59

1. Introduction

“Better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer”[1]

The Lawrence Inquiry concluded in 1999 that Britain ‘is institutionally racist’,[2] meaning collectively or systemically discriminatory. Evidence points to the fact that BAME (black, Asian and minority ethnic) people have been brought into the criminal justice process more often partly because of proactive police practices[3] and racially biased prosecution strategies.[4] Accordingly, whilst making up just three per cent of the total UK population, black or Black British people constitute twelve per cent of the total prison population.[5] Nevertheless, discrimination within the criminal justice system does not always manifest in terms of explicit racism, but through a series of indirect correlations and subtle associations; a ‘dangerous blend’ of innuendo, myth and ‘voodoo criminology’.[6]

The Common Law doctrine of joint criminal enterprise has found itself at the epicenter of the debate around race and the criminal justice system. Evidence suggests that up to thirty-seven per cent of joint enterprise convictions can be attributed to black or Black British people,[7] more than twelve times higher than the group’s percentage within the general population. These alarming statistics demand not only a robust account of the processes through which the over-criminalisation of specific populations is made possible, but also the way forward.

This paper raises important questions about collective action, individual agency, gang myth-making, street violence and implicit racism: how are street collectives termed ‘gangs’ tied to notions of race and ethnicity? What is the relationship between gangs and serious youth violence? How does the prosecution determine gang membership, and when do the courts impose collective liability? Should the whole group be held collectively liable when only one or a few of its members perpetrated the criminal act? Ultimately, through which processes does joint enterprise over-criminalise BAME, and particularly black and Black British people? This paper will argue that to understand the rapport between race and ethnicity and the doctrine of joint enterprise, one has to fully grasp the concept of the ‘gang’, and to disassociate myth from reality, public discourse from ontological discussion, collective liability from individual agency.

This paper will seek to demonstrate that (a) there is stark correlation between ‘gangs’ and groups of black youths pervading public discourse, as well as between ‘gangs’ and serious youth violence; (b) both correlations are ill founded and misguided; (c) the doctrine of joint enterprise has been used as a political tool to end gang violence and tackle gang culture; (d) evidence of gang membership or even mere association has been used and continues to be used in ‘gang-related’ joint enterprise cases to establish foresight and/or intention of the accessory to participate in the crime; (e) the ‘gang’, by its very ontological and phenomenological definition, as opposed to other group-types, demands individual agency and thus clashes with the concept of collective liability; (f) a more appropriate framework is needed to accommodate the realities of street organisations and which doesn’t problematise individual agency.

Once the reality of the street organisation is disassociated from the ‘highly structured, well-organised and hyper-violent’ representation of the gang, the police, the prosecution and the courts will be able to appropriately and efficiently tackle street violence without over-criminalising black youths under joint enterprise law.

2. Context: The Re-Emergence of Collective Punishment

Police response to the public disorders of the late 1970s and 1980s, such as the Brixton riots of 1981, the Broadwater Farm riot and the Birmingham riots of 1985, considered by many a symbolic battle for authority,[8] unveiled a reality unknown to the majority of the population: the tortuous relationship between a deprived community and a systemically discriminatory criminal justice system. In the aftermath of these altercations, the police reinforced its mass stop and search operations and coordinated raids in black and ethnic minority neighbourhoods, predominantly under s.1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence (PACE) Act 1984, while often bypassing the act’s requirements and relying on informal working practices.[9] Throughout the 1990s, police legal and discretionary powers to stop and search youths in the streets were significantly extended.[10] This occurred at the same time as the ideologically loaded, controversial label ‘criminal gang’ and term ‘black youths’ became inseparably bound in public discourse.[11] The police force began then to customarily identify ‘suspect populations’, who they considered likely to be involved in criminality.[12] Predictably, ethnic minority communities became the target of the ‘suspect population’ label in a way that ‘transcends their class position and is defined specifically by police officers in terms of ‘racial’ characteristics’,[13] as individuals and as a collective. Meanwhile, policy practitioners, prosecutors and the courts devised on their part various strategies to effectively deal with and collectively punish group offenders, including a revised version of the three-hundred-year-old doctrine of joint enterprise.

The creation of the Metropolitan Police’s Operation Trident in 1998 and the establishment of Manchester Action Against Guns and Gangs (MAAGGs) in 2001 marked the genesis for dedicated police and criminal justice teams tasked with managing coordinated responses to group offending[14], focusing on the gang. In 2007, more than twenty years after the Brixton Riots, twenty-seven young people were murdered in London by other youths. For mass media, and many policy practitioners, these killings were linked to ‘what was attributed to the rise of armed organised gangs in the UK; and to what many termed a burgeoning ‘gang culture’ amongst young people’.[15] This increasingly preponderant interpretation of the UK’s street organisations was backed by Home Secretary Smith’s 2007 ‘Tackling Gang Action Programme’,[16] and by the New Labour administration’s 2008 Action Plan to collectively tackle violent and street crime, outlined in a document entitled ‘Saving Lives, Reducing Harm and Protecting the Public’.

Following these developments, the English riots of 2011 led to a swift review of the purportedly growing problem of gangs and gang violence in the UK. Prime Minister Cameron identified ‘gangs’ as the ‘criminal masterminds’ responsible for the riots, that are to be held accountable for a ‘major criminal disease that has infected streets and estates across our country’.[17] This process concluded in the launch of the government’s Ending Gangs and Youth Violence (EGYV) policy in order to compare those individuals who were flagged as involved in ‘gangs’ to the profile of those convicted of ‘serious youth violence’.[18] There emerged a number of distinct differences between both cohorts that confirmed that penal strategies designed to reduce levels of serious violence which focus upon the ‘gang’ are likely to be misguided and ineffective in addressing the levels of serious violence perpetrated throughout the UK.[19]

The most recent manifestation of the trend towards collective responses to the gang is perhaps the execution of Operation Shield within the London boroughs of Lambeth, Haringey and Westminster.[20] The project focuses on gangs as a whole rather than individual members, thus shifting responsibility from individual to collective in gang-related cases:

“This will see every known member of the gang penalised through a range of civil and criminal penalties when one gang member commits a violent crime, such as a stabbing.”[21]

This astonishing shift towards collective responsibility and the collective punishment of a group based upon the behaviour of one individual marks a significant development in the State’s response to the perceived problem of the UK gang. Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the State’s and the judiciary’s current response to the gang phenomena is its willingness to legitimate the highly controversial category of liability without fault under the doctrine of joint enterprise. Here the ‘fault’ or causality element is absent, and liability rests under the assumption that all members of a cohesive, highly structured group are under a duty to ‘police’ all other members, and that such a duty demands accountability. This category of collective responsibility has concerted widespread criticism by academic commentators due to the recurring wrongful implication of innocent group members. Joel Feinberg, in describing the conditions that would make this morally palatable, asserts that collective criminal liability imposed on groups as a mandatory self-policing device is reasonable only when there is ‘a very high degree of antecedent group solidarity’:[22]

“Justice requires that the system be part of the expected background of the group’s way of life and that those held vicariously liable have some reasonable degree of control over those for whom they are made ‘sureties’. It is because these conditions are hardly ever satisfied in modern life that collective criminal responsibility is no longer an acceptable form of social organization.”[23]

The doctrine of joint enterprise has emerged in modern times in the context of the resurrection of collective punishment, and more specifically, coordinated responses to the gang. The British street ‘gang’, as will be argued in the following chapters, is an example of the group-type described by Feinberg, which is neither highly structured nor fundamentally cohesive, but that has nonetheless fallen into the dragnet of the joint enterprise doctrine.

3. Doctrinal and Theoretical Analysis: Joint Enterprise Doctrine, Anti-Gang Policy, and Race

3.1 HISTORY, DEFINITIONS AND LABELS

3.1.1 Dimensions of Joint Enterprise

Joint enterprise is not a specific law, or a type of offence. It should be regarded as a general principle or doctrine which evolved largely through common law rather than statute, and which falls within the wider scope of the law of complicity.

Its very definition has long been disputed. Wilson and Ormerod noted that “A striking illustration of the unsatisfactory state of the law is that we cannot confidently describe the precise scope of joint enterprise liability”.[24] Andrew Ashworth, in his evidence to the first Justice Committee inquiry on joint enterprise, described the law as “replete with uncertainties and conflict. It betrays the worst features of the common law: what some would regard as flexibility appears here as a succession of opportunistic decisions by the courts, often extending the law, and resulting in a body of jurisprudence that has little coherence.”[25] Lord Justice Toulson further commented in R v Stringer: “Joint enterprise is not a legal term of art. In Mendez and Thompson the court favoured the view that joint enterprise as a basis of secondary liability involves the application of ordinary principles; it is not an independent source of liability.” [26]

Over time, joint enterprise evolved as a nebulous and contested concept, becoming a catch-all term for all of secondary liability. Matthew Dyson agrees that the distinction between the traditional categories of aiding, abetting, counselling and procuring on the one hand, and parasitic accessory liability or the historical doctrine of joint enterprise on the other, has largely been lost[27]. That distinction had some benefits, such as allowing separate (lower) substantive, evidential and sentencing rules for truly joint criminality.[28] The law has since become wider, and harsher. Conversely, Dennis J. Baker has suggested that ‘no doctrinal nor conceptual distinction can be drawn between what is orthodoxly known as standard complicity (or accessory liability) and what is orthodoxly known as joint enterprise complicity’:[29] the concept of ‘common purpose’, he argues, runs through all three limbs of the current law of joint enterprise.

The 2012 CPS guidance[30] – which is currently being revised to reflect the Jogee and Ruddock ruling – set out three main ‘types of joint enterprise’, with reference to the Court of Appeal judgment in the case of R v ABCD:

- Where two or more people join in committing a single crime, in circumstances where they are, in effect, all joint principals, as for example when three robbers together confront the security men making a cash delivery.

- Where D2 aids and abets D1 to commit a single crime (under Section 8 of the Accessories and Abettors Act of 1861), as for example where D2 provides D1 with a weapon so that D1 can use it in a robbery, or drives D1 to near to the place where the robbery is to be done, and/or waits around the corner as a getaway man to enable D1 to escape afterwards

- Where D1 and D2 participate together in one crime (crime A) and in the course of it D1 commits a second crime (crime B) which D2 had foreseen he might commit.[31]

The first limb, where the perpetrators of the offence act as joint principals, is fairly straightforward; the second shows that joint enterprise is, in many cases, merely an incident of general accessory liability; and the third, the most problematic one, has been termed parasitic accessory liability (henceforth PAL). The historical doctrine of joint enterprise comprised the first and the third limb;[32] the second limb having been ‘swallowed’ by the now umbrella term ‘joint enterprise’ over time. Findlay Stark has further argued that cataloguing the third limb, or PAL, within the wider law of accessory liability is misleading, as, ‘far from being an invention of the mid-1980s, PAL existed consistently, in some form, from at least the sixteenth century’.[33]

Whether general and parasitic accessory liability are seen as two dimensions of the overarching joint enterprise doctrine or as more distinct from each other, this paper will use the term “joint enterprise” to refer to both forms of secondary liability, as well as to joint principal liability, for the purposes of clarity and consistency.

3.1.2 General and Parasitic Accessory Liability

While the concept of joint principal liability is relatively straightforward, secondary or accessory liability – in both its ‘general’ and ‘parasitic’ forms – is more complex.

What is often termed general accessory liability, or the law on aiding and abetting, covers the situation in which a defendant is said to have assisted or encouraged a principal defendant. This dimension of joint enterprise, although it first emerged through common law, was given statutory force by section 8 of the Accessories and Abettors Act 1861 (as amended by the Criminal Law Act 1977), which provides that anyone who ‘shall aid, abet, counsel or procure the commission of any indictable offence… shall be liable to be tried, indicted and punished as a principal offender’.[34] As expressed by the Law Commission, under section 8:

A person who, with the requisite state of mind, aids, abets, counsels or procures another person to commit an offence is him or herself guilty of that offence (provided that the offence is subsequently committed). Accordingly, D is liable to the same stigma and penalties as P.[35]

The dimension of joint enterprise commonly known as parasitic accessory liability, as noted above, “concerns the liability of accessories for a further or collateral offence (crime B) committed by the principal defendant in the course of an initial crime or criminal venture in which all participated (crime A).”[36]

Among many cases which were significant in the development of PAL, the most prominent was Chan Wing-Siu v R.[37] This case, originating in Hong Kong, concerned a fatal stabbing committed in the course of an armed robbery, in relation to which three defendants were convicted of murder. The trial judge had directed the jury that an accomplice could be guilty of murder if he had foreseen that his co-defendant might stab the victim intending to do serious harm. An appeal against the convictions was subsequently dismissed by the Privy Council, for whom Sir Robin Cooke stated:

The case must depend … on the wider principle whereby a secondary party is criminally liable for acts by the primary offender of a type which the former foresees but does not necessarily intend. That there is such a principle is not in doubt. …The criminal liability lies in participating in the venture with that foresight.

In October 2015, the UK Supreme Court and Privy Council heard two appeals against joint enterprise convictions for murder: R v Jogee and Ruddock v The Queen (Jamaica).[38] Both appeals were allowed, in a decision that effectively abolished parasitic accessory liability, concluding that the common law on joint enterprise had previously taken a “wrong turn”.

3.1.3 A Historical Account of the Doctrine

Originally, the law was established to “prosecute the seconds and aides of persons embarking upon duels to resolve ‘gentlemanly’ disputes”[39]. Under Common Law ‘where one of the disputants was killed in a duel then all parties facilitating the illegal practice of duelling could be prosecuted for their part in bringing about the illegal death, not just the surviving duellist with his sword or pistol’[40].

In Anderson[41], the courts expressed the doctrinal basis for joint enterprise liability as follows:

Where two persons embark on a joint enterprise, each is liable for the acts done in pursuance of that joint enterprise, that includes liability for unusual consequences if they arise from the execution of the agreed joint enterprise but… if one of the adventurers goes beyond what has been tacitly agreed as part of the common enterprise, his co-adventurer is not liable for the consequences of that unauthorised act… It is for the jury to decide whether what was done was part of the joint enterprise, or went beyond it…[42]

This statement is allegedly an expression of the conceptual basis for joint enterprise liability, but digging deeper the statement is more complex: it describes not one but two distinct bases for D’s liability for the acts of P. The first limb relies on the traditional notion of ‘joint principal liability’. The second limb, often referred to as an ‘exculpatory’ limb[43], relies on the existence of derivative accessory liability, and it seems in the past to have been drawn upon to determine the scope of the joint enterprise as ‘limited’ by the common purpose. By ‘not clarifying the relationship between liability based on ‘common purpose’ and liability based upon ‘tacit agreement’, the stage was set for severing the ties between joint enterprise liability and the traditional derivative basis to accessory liability’.[44] Thus, parasitic accessory liability, although governed by the rules of the law of accessory liability, developed as an independent category of the joint enterprise doctrine.

Restricting liability to conduct done in pursuance of a common purpose in a strict sense (premeditation or planning) proved too narrow a limit of liability, in particular in cases of concerted acts of aggression, such as street fights, which have a tendency to escalate into greater violence. It is perhaps because of this and because the notion of ‘tacit agreement’ was so vague that the Court of Appeal in R v Hyde[45] decided to dispense with it altogether, following the ruling in R v Chang Wing-Siu. The Hyde principle thus established the fact that ‘D contemplating as a real risk that P might commit murder (crime B) and yet continuing to lend support to P in the commission of the common purpose to commit crime A is enough to render D liable for crime B’.[46] The consequence of the Hyde principle is that it is possible that a secondary party could be found guilty of murder on the basis of not much more than foresight as inferred from mere association with a joint criminal enterprise,[47] for example, by being a member of a gang.

In Powell,[48] a drug dealer was murdered by one of three people, the defendant being one of them. The prosecution could not prove who fired the gun which caused the death. The House of Lords finally confirmed that “participation in a joint criminal enterprise with foresight or contemplation of an act as a possible incident of that enterprise is sufficient to impose criminal liability for that act carried out by another participant in the enterprise”.[49] Thus phrased, the principle seems to inculpate rather than exculpate, a stark move since Anderson: it broadens S’s liability to cover acts which were merely foreseen as a possible incident of the contemplated crime. Lord Steyn noted, in an attempt to justify the principle behind the conviction:

Experience has shown that joint criminal enterprises only too often escalate into commission of greater offences. In order to deal with this important social problem, the accessory principle is needed and cannot be abolished or relaxed.[50]

In the recent conjoined cases R v Jogee and Ruddock v The Queen, the Supreme Court considered whether the law of joint enterprise had ‘taken a wrong turn’ in Chan Wing-Siu and Powell and English. The appellant Jogee was convicted as an accessory under PAL to the murder of Mr Fyfe, following an attack on the victim orchestrated by the principal and himself. The appellant threatened the victim with a bottle before the principal stabbed him with a kitchen knife. The appellant Ruddock was convicted as an accessory to the murder of Mr Robinson, a taxi driver. The murder was committed in the course of robbing the victim of his taxi. The judges in both cases directed the jury that the appellants were guilty of murder only if, in the course of the respective attack and robbery, the appellants could have foreseen that the principal intended to cause grievous bodily harm or murder the victim. Both Jogee and Ruddock appealed to have their convictions revoked at the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court held, allowing the appeals, that the Board of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Chan Wing-Siu was wrong to have ‘equated foresight with intent to assist, as a matter of law; the correct approach is to treat it as evidence of intent’.[51] Although foresight may be evidence of intention, it had never previously been treated as a substitute for intention, and it is argued, should not be confused with it. Consequently, all subsequent decisions that relied upon the authority of Chan Wing-Siu were also wrong on that point. This meant that foresight had to be substituted for intention for all categories and PAL was effectively abolished, because its very definition relies on foresight.

Following Jogee, uncertainties remain: (1) there still is lack of clarity regarding the level of foresight required to infer intention by an accessory[52]; (2) it is still the case that where there is a prior joint criminal venture it is possible for the jury to infer the intent; (3) joint criminal venture is still susceptible to be equated with membership or association with a ‘gang’ or street collective. These issues remain unresolved and pose threats to the fairness of conviction of defendants under the doctrine of joint enterprise.

3.2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: COLLECTIVE VS. INDIVIDUAL RESPONSIBILITY

The problems of principle with joint criminal enterprise concern not the hazy legal notion of ‘foresight’ or the dangers of inference, but issues of intentionality and accountability. The wider discussion which has underpinned the doctrine of joint enterprise has sought to address the highly contentious notion of collective responsibility. Collective responsibility refers to the responsibility that can be assigned to every member of a group or organisation without regard to an individual member’s participation in the decision-making or execution of a group action.[53] Criticisms of the notion include that it problematizes individual agency,[54] revives notions of guilt by association and clan identity,[55] and increases the chances of miscarriages of justice, when a (possibly peripheral) individual member of the group can be held liable for the actions perpetrated by other members and towards which he did not contribute. On the other hand, proponents of the notion of collective responsibility contend that, on certain occasions, groups perpetrate actions which could never have been committed by individuals alone, and it therefore seems natural and convenient to hold an aggregate of individuals collectively liable. Nevertheless, H. D. Lewis has asserted that, no convincing theory of group action exists which could ever allow collectives to be admitted into the moral realm.[56] He takes it ‘as foundational to ethics that no individual person can be held morally responsible for the actions of another individual’.[57]

According to Baker, no doctrinal or conceptual distinction can be drawn between what is orthodoxly known as standard complicity, or secondary liability, and what is orthodoxly known as joint enterprise or common purpose complicity[58]. Accordingly, section 8 of the Accessories and Abettors Act of 1861, which applies to all of secondary liability, dictates that “a person who, with the requisite state of mind, aids, abets, counsels or procures another person to commit an offence is him or herself guilty of that offence”. The required actus reus is thus aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring, often referred to as assisting or encouraging the perpetrator. Baker suggests, however, that what the joint criminal enterprise cases show is that ‘A is often held liable regardless of whether her act of participating in the underlying joint enterprise encouraged P to perpetrate the collateral crime’[59]. Indeed, the direct consequence of the Hyde principle is that a secondary party could be found guilty of murder on the basis of not much more than mere association with a joint criminal enterprise. The House of Commons Justice Committee reported:

Prosecutions for murder on the basis of joint enterprise have become more common in recent years and are increasingly focused on evidence of association or alleged gang membership. There is increasing potential for cases to be left to juries largely on the basis of evidence of association between defendants, a trend which we believe is directly related to the [Hyde] principle.[60]

Understandably, contemporary legal theory commentators have put forward highly elaborated justifications for convicting an individual on the basis of pure association with a criminal enterprise. Christopher Kutz has argued for a theory of accountability in which ‘any real understanding of collective action not only allows but demands individual responsibility’.[61] His is a minimalist, non-reductive conception of collective action and collective responsibility. Collective action as such requires only agents who act on overlapping participatory intentions: “so long as the members of a group overlap in the conception of the collective end to which they intentionally contribute, they act collectively, or jointly intentionally”.[62] By making individuals’ participatory intentions central to evaluating their accountability, Kutz claims, we can link individuals to collective harms regardless of their causal contributions: this is the current basis of the law of joint enterprise. He considers this conception to be superior “due to its normative significance, as it doesn’t rely upon high degrees of interaction or mutual knowledge, elements that are often absent in ethically complex cases of joint action”.[63] Yet, it is precisely because of how ethically complex these cases are that a non-reductive account of collective action fails to provide a satisfactory framework. The complexity in these cases stems from the frequently high number of defendants appearing in court and the evidential ambiguity surrounding the fatal blow: claiming that all defendants should be held liable for the acts perpetrated by just one or some individuals is not only superficial, but also highly dangerous. By way of illustration, in a situation where twenty individuals gather in the streets and start a fight against another group, it will most likely be possible to identify differing levels of intention: some of them will not want to even be part of the fight, some will engage in the fight in order to stop it, some will participate just by shouting and pushing, and some will pull out a knife and stab the victim. The possibilities are infinite. The question is then, are all of the defendants who participated in the fight morally responsible for the stabbing of the victim? Critics disagree.

Reaching a similar conclusion, Andrew Simester has contended through his ‘change of normative position’ claim, that it is enough that “A changed her normative position by joining the underlying criminal enterprise with foresight of the fact that P might perpetrate a collateral crime”.[64] A person who intentionally confronts another “crosses the relevant moral threshold, and thereby nullifies (or perhaps forfeits the protection of) the restrictive principles that would normally prevent us being held criminally liable for consequences accidentally or unforeseeably caused”.[65] Simester’s theory centres on the intention to ‘wrong’ another (i.e. to bring about a certain harm or risk of harm in a certain way) rather than the intention to harm another.[66] Criticisms of this theory are two-fold: firstly, by ‘underlying criminal enterprise’ the courts and the prosecution have, more often than not, referred to the concept of the ‘gang’, which is deemed to be intrinsically violent and is indirectly correlated with groups of black youths. This issue will be addressed in the following chapters. Secondly, in a more straightforwardly ethical critique, Baker argues that Simester’s ‘change of normative position’ claim does not provide a normative explanation of the fairness of holding a person liable for unintended collateral crimes stemming from an underlying joint enterprise. “Why is constructive liability based on mere foresight and association fair when the accessory is being held equally liable for a crime perpetrated by another?”[67]

The conduct element (here, assistance or encouragement) supplies a key normative ingredient. It is A’s intentional indirect physical contribution to P’s harmful conduct that makes it fair to hold A liable for P’ s act of criminal perpetration. This does not mean A and P need to be held equally liable when there has been only reckless encouragement/assistance on the accessory’s part. The reckless accessory should be charged with an independent lesser offence for personal wrongdoing rather than derivative wrongdoing.[68]

Michael Bratman’s reductive theory of we-actions[69] provides a robust account of collective and individual agency, according to which the twin-requirements of shared intention and collaboration (or ‘commitment to mutual support’) are the basis of all collective actions. In response to Kutz’s minimalist conception of collective action, Bratman argues that ‘acting collectively’ and ‘acting jointly intentionally’[70] are two completely different things: (JIA) jointly intentional activity is weaker than (SCA) shared cooperative activity because sharing an intention, or goal, is far stronger than just holding a goal collectively. SCA would require the further commitment to mutually support the other members of the group. He states:

(Any) joint action-type can be loaded with respect to joint intentionality but still not strictly (be), cooperatively loaded[71]

For a joint criminal enterprise conviction to be morally palatable, collective action, and not jointly intentional action, is the only satisfactory standard of jointness. Analogously, Beatrice Krebs builds upon Bratman’s twin-requirements of shared intention to construct a convincing critique of Simester’s ‘change of normative position’ claim:

[…] If the essence of joint criminal ventures, as is unanimously asserted, are the twin-requirements of ‘shared purpose’ and ‘collaboration’, then it is difficult to see how they can found the basis of liability for criminal conduct in which they are conspicuously absent: in cases such as we are concerned with here, P commits an additional or more serious offence than S intended to be a party to, and P does so alone (albeit during the course of criminal activity in which P and S have worked together). There is thus no shared purpose, and there is no division of labour, no contribution of S as regards this further crime.[72]

Bratman’s theory and Krebs’ critique will be explored in-depth in the following chapters.

In regards to the mens rea required to hold an individual liable under joint enterprise, a number of commentators have offered highly elaborated theories to justify adopting a lower standard of mere foresight. Although the Supreme Court in Jogee ruled that the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Chan Wing-Siu was wrong to have replaced ‘foresight with intent to assist, as a matter of law’, scholars do not have it so clear. According to K. J. M. Smith’s ‘assumption of risk’ model, S, by joining forces with P, signs up to the goals of the joint enterprise and accepts responsibility for all the wrongs (perpetrated by P) in realising that goal[73]. Likewise, G. R. Sullivan’s ‘culpability-risk’ model suggests that by participating with P in crime A, S has enhanced the risk of crime B occurring[74]. On such an analysis, S’s extra liability is triggered because “S enhanced P’s dangerousness, and the fact that he agreed to or otherwise became complicit in crime A, aware that crime A might lead P to commit crime B, exacerbates the wrong that D does in agreeing to or becoming complicit in crime A”[75].

As a matter of principle, Krebs has argued, it appears doubtful whether the ‘assumption of risk rationale’ can, normatively as well as evidentially, be equated with mere foresight. Under an assumption of risk analysis the law generally does not let a cognitive element such as knowledge or foresight alone suffice[76]. Usually, it requires that S willingly or at least consciously accept running an objectively unreasonable risk.[77] This is a volitional element which, it is suggested, needs to be proved in addition to foresight. Furthermore, as with the assumption of risk approach, the problem with the ‘culpability-risk’ model is that it is not obvious that every time S participates in joint criminal activity, he has thereby enhanced the risk of P’s committing a further wrong. This can only be said for “crimes where the risk is inherent in the original enterprise – the more tenuous the link between purpose crime and collateral crime, the more difficult it is to argue that S has increased the risk of P committing the collateral crime”. [78] Thus, the problem lies not with justifying why the law imposes responsibility on S at all, but rather why it imposes the same amount of responsibility on him as it does on P.

Collective liability is a contested concept which needs clarification.

3.3 FROM MYTH-MAKING TO POLICY-MAKING

3.3.1 From myth to reality: gangs, race and teratologies

“An underclass now exists and at its heart, gang culture prevails… For too many the gang leader becomes their inspiration, assuming the role of a father figure but with a brutal code based on savage and violent discipline. In the midst of this sits rap music, celebrating and exciting the same values.”[79]

“It is about a specific problem within a specific criminal culture to do with guns and gangs […] The black community […] We won’t stop this by pretending it isn’t young black kids doing it.”[80]

Academic interest can be traced back to the work of the Eurogang Network in the late 1990s[81], which sought to challenge European policy makers’ “denials about the existence of street gangs in the UK because they didn’t fit the hyper-violent, highly interconnected typology of the ‘real gangs’ that are found in the US”[82]. The Eurogang Network agreed on that, although there isn’t one all-encompassing definition of the gang, there are certain key characteristics which are common to British gangs: they are mostly male and youthful, mostly minority by race or ethnicity, mostly self-recognised as a group and mostly oriented toward criminal activity. However, defining what constitutes the gang remains a complex matter. Far from adopting any common definition, every study in the UK on gang membership has adopted its own version[83].

The earliest academic definition of ‘the gang’ was Puffer’s, who in 1912 positioned ‘the gang’ as ‘one of three primary groups: the family, the neighbourhood, and the play group’[84]. Thrasher, for his part, saw the gang as an ‘interstitial entity’ that formed spontaneously among young migrants in the context of the city of Chicago[85]. This definition, although less criminalising, is closer to the ‘modern gang’ definition embraced by the Eurogang Network. According to Professor Alexander, the ‘modern’ or ‘criminal gang’[86] develops the characterisation of the ‘classic gang’ by centralising criminality and violent conflict[87]. Relatedly, the mythical American ‘gang’ has ‘travelled across the Atlantic largely intact’ – or at least in the tales of the press, politicians and policy makers. Alexander notes that it might be more accurate to argue that the current anxiety reflects more ‘an increasing Americanization of the understanding of the phenomenon, and the institutional response, rather than of the phenomenon itself’[88]. ‘The gang’ becomes then the baseline for understanding the recent outbreak of youth murders, offering ‘Hollywood style images of urban chaos and random violence’[89].

Whilst not contesting the fact that street collectives which approximate gangs are part of the problem of violence in cities like London, Manchester and Birmingham, numerous critics argue that ‘constructing the problem of street violence as essentially a problem of gangs is an exercise flawed on empirical, theoretical and methodological grounds’[90]. In their Dangerous Associations report[91], Williams and Clarke carried a comparative analysis of gang and serious youth violence cohorts to establish that although they make up a much smaller proportion of those perpetuating youth violence, BAME people are overwhelmingly identified and registered on the police’s ‘gang matrix’. What is most revealing about these findings is the stark disproportionality between those engaging in violence and those labelled as ‘gang involved’: whilst eighty-nine per cent of those identified as ‘gang members’ by the Manchester Police were BAME, only twenty-three per cent of serious youth violence involved BAME people[92]. Additionally, a Home Office funded survey examining the extent of gang membership among young people in Britain estimated that no more than six per cent of the total sampled could be classified as ‘delinquent youth groups’[93]. The disconnect is two-fold: first, between the groups labelled as ‘gangs’ and the groups engaging in serious youth violence, and second, between groups of black youths and groups engaging in serious youth violence.

Klein[94], Pitts[95], and others have sought to demonstrate the validity of the ‘Gangland UK thesis’ through an empirically driven gang research tradition, which Jock Young characterises as ‘voodoo criminology’. Voodoo criminology, grounded on ‘voodoo statistics’, is ‘denatured and desiccated’, ‘representing [gang members] by the statistical symbolism of lamda, chi, and sigma, their behaviour can be captured by the intricacies of regression analysis and equation’[96]. As Katz has observed:

“The gang as it is reproduced in this species of scientific criminology dangerously misrepresents the complexity of the street world it aspires to represent precisely by virtue of its crude reductionism”[97]

According to numerous criminologists, ethnographers and phenomenologists, the correlation between ‘gangs’ and ‘black criminality’ stems from a misunderstanding of street violence and a long history of discrimination against the black community and the black culture. The label ‘gang’ is used as a synonym of ‘groups of black youths’ to reinforce the concept of the ‘black criminal’ which ‘threatens white middle-class society’. According to Simon Hallsworth, one of the main opponents of the ‘UK gangland thesis’, in gang talk we find:

“A world reduced to a fundamental binary between the healthy ‘included’ (white) middle-class society and, confronting it, (black) feral gangs that threaten to overwhelm it (unless beaten back).”[98]

The central elements of gang talk include novelty, proliferation, corporisation, weaponisation, penetration, and monstrousness[99]. The elements of ‘corporisation’ and ‘monstruousness’ are perhaps the most revealing, in terms of the popular description of groups of (mainly black, underprivileged) youths as ‘hyper-violent, highly structured, incorporating organisational pre-planned goals’. Therefore, the term gang signifies not this or that group out there but “a Monstrous Other, an organized counter force confronting the good society”; what Katz and Jackson-Jacobs describes as a ‘transcendental evil’[100]. McGuire explores further what it is about the Other that constructs it as such: he argues that we use a science of abnormality, a teratology[101]; in effect, a science of monsters. Gang talk is then one of societies most potent teratologies, a treatise on the imagined deformed and deforming nightmare that white society imagines is taking root within the inner-city ‘heart of darkness’. The ‘myth of black criminality’[102], reiterated by politicians, the police, and the media, only amplifies the public’s anxiety about street violence, knife crime and offers a biased account of ‘black culture’. In August 2007, Jack Straw blamed ‘violence and crime among young black men on the fact that many grow up in homes without fathers… widespread educational failure among black boys and their attraction towards gangs which was caused not by poverty but a ‘cultural problem’’[103]. Rap, and any other elements of black culture are then swallowed by the myth of black criminality, thus contributing to their ‘monstruousness’.

3.3.2 The law of Joint Enterprise as a political tool to deter youths from gangs: from myth-making to policy-making

The only specific anti-gang statue currently available to the police and prosecutors is the Gang Injunction. Civil Gang Injunctions (CGIs; i.e., court-issued restraining orders) were introduced to prohibit and deter gangs from specific legal activities or from entering certain areas[104]. Introduced in the Policing and Crime Act in 2009, “under the Gang Injunction police and local authorities may apply to a county court for a gang injunction against individuals whom they believe, on the balance of probabilities, to be involved in gang-related violence, with the objective of diverting the subject from gang involvement rather than punishing them”[105]. In the UK, between 2011 and 2014, eighty-eight gang injunctions were put in place in twenty-five areas identified by the government as Ending Gang and Youth Violence priority areas[106]. In place of appropriate anti-gang legislation, in the past thirty years in England, prosecutors have used the common law doctrine of Joint Enterprise as a “de facto anti-gang statute with which to target adolescents and young adults allegedly involved in street gangs”[107].

That Joint Enterprise has been used as a political tool to tackle gang culture and deter youths from joining street gangs is no accident. Sir Robin Cooke made clear in Chan Wing-Siu the policy objectives of the joint enterprise doctrine:

“What public policy requires was rightly identified in the submissions for the Crown. Where a man lends himself to a criminal enterprise knowing that potentially murderous weapons are to be carried, and in the event they are in fact used by his partner with an intent sufficient for murder, he should not escape the consequences by reliance upon a nuance of prior assessment, only too likely to have been optimistic.”[108]

In R v Powell and R v English[109], Lord Hutton noted that “although ‘as a matter of logic’ it might be perceived as atypical that a secondary party could be found guilty of murder on the basis of foreseeability of death or serious harm which would not be sufficient mens rea for conviction of the principal party, ‘the rules of the common law are not based solely on logic but relate to practical concerns’, namely ‘the need to give effective protection to the public against criminals operating in gangs’.”[110] Lord Mustill added that the law is determined by ‘practical and policy considerations’, and that ‘intellectually, there are many problems with the concept of a joint venture, but they do not detract from its general practical worth’.

Law has both a regulatory and an educative role and the police tend to favour prosecutions of gang members under the doctrine of Joint Enterprise because they believe it sends a powerful deterrent message to would-be affiliates about the perils of gang involvement. In a speech on BBC Radio 4 in 2010[111], Lord Falconer, former Lord Chancellor, held:

“The message that the law is sending out is that we are very willing to see people convicted if they are a part of gang violence – and that violence ends in somebody’s death. Is it unfair? Well, what you’ve got to decide is not, ‘Does the system lead to people being wrongly convicted?’ I think the real question is: ‘Do you want a law as draconian as our law is, which says juries can convict even if you are quite a peripheral member of the gang which killed?’ And I think broadly the view of reasonable people is that you probably do need a quite draconian law in that respect.”[112]

The recently published Bureau of Investigative Journalism’s report suggested that Lord Falconer’s statement amounts to an implicit justification of possible injustice in the name of the greater good. ‘Is it really the view of “reasonable people” that it is best to condone an evidence bar set at a level that allows peripheral members of a joint enterprise to slip under it in the name of deterrence?’[113] The report demonstrates that this is a dangerous state of affairs. Accordingly, Krebs rightly refers to joint enterprise as a lazy law, adding that it ‘unduly favours the prosecution and undercuts established principles of criminal law – at the cost of individual rights’[114].

Although proponents of the law of joint enterprise rightly argue that street violence and knife crime are tangible problems often leading to tragic consequences and complex cases to which the law of joint enterprise offers a simple, ready and powerful solution, findings overall suggest that the strongest deterrent effects arise “more from the certainty of apprehension rather than from the severity of punishment”[115]. In the Joint Enterprise follow-up report published by the House of Commons Justice Committee[116], Crewe corroborated that the main deterrent effect of any law functions on people’s belief in the certainty of being caught. Consequently, legislation that holds all gang members responsible for an individual member’s actions will have little deterrent impact if the main principle of deterrence (i.e. awareness of sanctions and a corresponding increase in risk perception) is not understood by the target populations.

Wood et al.[117] recapitulate what research has shown so far: gang members are unlikely to be deterred from carrying and using guns[118], unlikely to perceive certainty of arrest, are not influenced by the potential severity of punishment[119] and expect little condemnation from significant others for offending[120]. Other research shows that deterrence efforts have less impact on gang members than on other youth[121].

It has been suggested that the gang is, to a certain extent, a mythology, or a teratology. But how did the criminal justice system incorporate the ‘gang’ in police and prosecution strategies; how did it go from mythmaking to policymaking?

The CCJS’ Dangerous Associations report provides the most recent and comprehensive statistical and qualitative evidence on the matter. The gang, as it has been suggested, is closely associated in public and official discourse with BAME youths and serious youth violence. Nevertheless, data suggests there is a disconnect between people identified as gang members (eighty-nine per cent of people in the Manchester ‘gang matrix’ are BAME) and people engaging in serious youth violence (only twenty-three per cent of them being BAME)[122]. Additionally, data suggests the ‘gang’ is statistically more likely to be employed in joint enterprise cases involving young BAME men. Indeed, “over three quarters of the whole BAME group (78.9%) reported that ‘gangs’ were introduced within the court arena. Comparatively, 38.5% of the ‘White’ group acknowledged the use of the ‘gang’ within the court arena”[123]. For the overwhelming majority (97%) of those reporting that ‘gangs’ were introduced at their trial the gang label was contested and dismissed as untrue, a ‘made up’ feature of the prosecution’s argument[124]. The report also explores a number of linguistic cues and signifiers that are regularly used by the prosecution and the police to link the accused to the construct of the ‘gang’ and thus to demonstrate ‘common purpose’ in joint enterprise cases. These include terms used to elicit images of street-based or violent collectives such as ‘crew’, ‘hoodlums’, ‘click’, ‘soldiers’, ‘troops’ or ‘posse’ and dehumanising signifiers such as ‘animals baying for blood’, ‘a pack of wolves’, or ‘a pack of animals’[125]. As illustrated in the Lewis case study examined by the researchers and authors of the report, the prosecution brought the defendants’ previous convictions and various media reports (so-called ‘bad character evidence’) supposedly demonstrating gang affiliation to the trial. In this case, evidence of gang affiliation mainly revolved around rap videos posted online and pictures downloaded to the defendants’ phones, where Lewis appeared together with his cousin who was identified as one of the gunmen in the trial.

Pitts also exposes the reality of case building by the police and prosecution in alleged gang-related cases, concluding that police evidence:

[It] tends to take the form of a listing by specialist police officers of analogous cases that have been successfully prosecuted in the past. This listing is accompanied by a quasi-anthropological account of the raison d’être, culture, values, attitudes, structure, dynamics, activities and modus operandi of the youth gang. In this preamble particular attention is paid to the distinctive language, signs and symbols employed by youth gangs, their musical tastes and their propensity to produce sensational RAP videos.[126]

Gangs, from myth to reality, and reality to policy-making, have pervaded public discourse and have been used as a political instrument through which to criminalise groups of black youths deemed as problematic. Perhaps, as was concluded in the previous chapter, a more robust account of collective action and collective liability could be useful to decriminalise the gang and its innocent members, and rightfully criminalise those at fault.

4. Mapping Out Collective Intention and Moral Agency in Multi-Agent Cases: Redefining the Gang and Restricting the Dragnet

“Rather than [reading] gangs as a command structure shaped in the image of a tree, let’s capture them and their development instead rhizomatically as ramifications, lateral offshoots; in a sense, a glorious species of weed.”[127]

4.1 Recapitulating and Way Forward

A number of findings, conjectures and conclusions have been addressed in the previous chapters:

- Black and ethnic minorities are disproportionately convicted under joint enterprise: 37% of all prisoners convicted under joint enterprise are black, almost three times the proportion of black prisoners in the general prison population (12%), and almost ten times the proportion of the black people in Britain.

- Empirical evidence suggests there is a stark disconnect between ‘gang’ and youth violence cohorts in Britain, and points to the significance of ‘race’ and ethnicity in explaining this disconnect: although BAME people are overwhelmingly identified and registered to ‘gangs’ lists (e.g. 19% for the Manchester area), they make up a much smaller proportion of those perpetuating serious youth violence (e.g. 6% for the same area). Further analysis reveals that the ‘gang’ label is particularised to the ‘Black’ group.

- Notwithstanding statistical evidence, the ‘gang’ is, both in public discourse and police ‘gang’ lists or ‘Gang Matrixes’, synonym to, or at least, strongly associated and indirectly correlated with, groups of BAME youths and serious violence. As a result of the correlation between ‘gangs’ and groups of BAME youths, and ‘gangs’ and serious violence, BAME youths appear to be the main recipients of police and prosecutorial strategies targeting the ‘hyper-violent gang’. The correlation is established as such:

- If a = b and b = c, then a = c;

- Where a refers to groups of black youths, b refers to ‘gangs’, and c refers to serious violence

- There is both empirical evidence and formal statements made by public officials suggesting that the doctrine of joint enterprise, in all its forms, has been extensively used and continues to be used as a political tool to end ‘gang crime’, tackle ‘gang culture’, and deter youths from associating with ‘gangs’. These policy objectives are grounded on the assumption that such street collectives labelled ‘gangs’ are at the source of serious violence and crime

- There also is evidence to suggest that the term ‘joint criminal venture’, which is the basis for joint enterprise liability, is, more often than note, a synonym of the ‘gang’. The consequence of this, together with the ambiguity surrounding the level of foresight required to infer intention by an accessory, is that it is possible that a secondary party could be found guilty of murder on the basis of not much more than mere association with a ‘gang’

- Therefore, it has been contended that:

- If the ‘gang’ label is disproportionately attributed to BAME people, and particularised to young black males;

- If ‘gangs’ are deemed to be at the source of street violence and crime in Britain;

- And if the doctrine of joint enterprise has officially targeted gangs in an attempt to tackle the issue of street violence, it appears as a logical consequence that the ‘gang’ would be and is statistically more likely to be employed in joint enterprise cases involving young BAME men.

All in all, to understand the disproportionate representation of black and ethnic minorities in the joint enterprise prison population, it is necessary to understand the relationship between ‘gangs’ and race, and ‘gangs’ and serious youth violence. This paper has argued that, because of the direct and indirect correlation between gangs and race, a large part of the over-criminalisation of black and ethnic minorities can be explained by the inaccurate and unfounded representation of the gang as a hyper-violent, highly structured organisation; a description which has been widely and formally used by the media, the police, the prosecution and the courts.

It has become increasingly clear that a conceptually robust account of collective and individual action is urgently required to resolve the conundrum around joint enterprise, gangs, and race. This chapter will seek to construct a highly elaborate account of collective action as well as an ontologically superior interpretation of the British gang in order to provide a thorough understanding of the reality of street organisation. First, once a template by which to determine matters of responsibility and collectiveness has been construed, criminal justice practitioners, not only may, but also will have a duty to juxtapose against the template all groups involved in multi-agent cases, in order to establish whether these can be held collectively liable. Second, once the reality of street organisation is disassociated from the ‘highly structured, well-organised and hyper-violent’ representation of the gang, the police, prosecution and the courts will be able to appropriately and efficiently tackle street violence without over-criminalising black youths under joint enterprise law.

4.2 Mapping Out Collective Liability

When we seek to hold a person accountable for some harm, we sometimes mean to ascribe to her liability to unfavourable responses from others. In the standard case of responsibility for harm there can be no liability without contributory fault[128], or causality. If contributory fault is to be established, Feinberg argues, three preconditions must be satisfied: first, the responsible individual must have done the harmful act in question (actus reus); second, the causally contributory conduct must have been in some way ‘faulty’ (mens rea); and finally, the “requisite causal connection must have been directly between the faulty aspect of his conduct and the outcome”. Certain common deviations from the standard case, however, cause confusion and doubt. The most general category is ‘strict liability’, for which the contributory-fault condition is weakened or absent, and collective liability is its most noteworthy subspecies. Collective liability holds the whole group responsible for the actions of one or a few of its members[129]: responsibility is thus distributed from the perpetrator or perpetrators to all other members, linking individual behaviour to collective action and back to individual culpability. Under collective liability, the contributory-fault condition is absent, and may be inferred from the individual’s membership or allegiance to the group. Accordingly, an individual may be held accountable and share responsibility for the actions of another member or members of the group, based solely on his association with or connection to the perpetrators, and membership status. Criticisms of collective responsibility suggest it threatens the realm of ethics. H.D. Lewis condemns the “barbarous notion of collective or group responsibility”[130] for reviving notions of clan identity and guilt by association.

Under certain circumstances, however, it is appropriate and natural to talk about groups as moral agents. It is natural in that it might well be expected of the members of a group to undertake the organisation of the group’s affairs, and assume responsibility for all intended or unintended, positive or negative consequences. As a customer, for example, I would like to hold the companies I obtain goods and services from responsible for the moral implications of their business affairs. In the case of corporations, or institutional collectives, V. Held argues, under certain circumstances[131], moral agency may be assigned to the corporation itself[132]. Since the implications of holding a group and its individual members collectively liable are significant, a number of fundamental questions must be addressed: can, and should, moral agency be assigned to groups other than institutions? What is the defining characteristic or characteristics that make corporations or institutions different from other groups? Which conditions have to be met to make a group collectively liable for the actions of just one or a few of its members?

The common law doctrine of joint enterprise, as discussed in the previous chapters, is based on a form of collective liability. This entails that all members of a ‘joint criminal enterprise’ shall share responsibility for the consequences of the group’s actions, even if these were perpetrated by one member alone, and when no contributory fault can be established. The Victoria Station killing or the murder of Sofyen Belamouadden[133] is a clear example of collective liability. The prosecution had no clear evidence of who struck the fatal blows, so they relied on joint enterprise, making the group liable for a crime committed by one of its members. All twenty teenagers arrested in the aftermath of the killing were charged with murder, including those not present at the moment the victim was killed, and eight were convicted of murder or manslaughter. The media reinforced the prosecution’s claim that the defendants – mostly black males – were members of a ‘territorial gang’, although evidence of gang membership was never found, and that they were ‘in it together’ by referring to the crime as ‘a fight between two gangs of youths, [which] ended in a fatal stabbing’[134]. The gang narrative, in correlation with the narrative of black criminality in public discourse, reinforces the public’s perception that collective liability is now more necessary than ever. The problem with joint enterprise, then, becomes one of collective liability replacing individual responsibility.

4.3 Bratman’s Template of Collective Action

It has become increasingly clear that a far more philosophically robust account of individual and collective action is needed, notably as it relates to technical matters of intentionality and responsibility when dealing with joint criminal enterprise cases. Anthony Amatrudo has stressed that “a new approach is required that neither falls into the criminological pitfalls of addressing the issue solely in terms of culture nor succumbs to the mystical legal notion of ‘foresight’”[135]. In arguing that the current discussion around joint criminal enterprise will benefit from a critical engagement with analytical philosophy, Amatrudo proposes to use Michael Bratman’s technical account of collective action to build a template by which to determine matters of jointness and enterprise. This would be particularly useful to determine the content of the intentions of the members of a group in relation to that group: shared intentions, Bratman argues, are the defining characteristic of we-actions, or collective action. If all members of a group share the same intentions, or purposes, and are committed to mutual support, they can be said to be engaging in shared cooperative activity, and their actions can then be understood as collectively executed. Following from this, if their actions can be understood as collectively executed, then individual members can be held accountable for such actions even if they themselves did not perpetrate them: in other words, they can be held collectively liable.

Bratman’s most important point is that all cases of collective action may be reduced to constituent actions and to the individual actor, ‘deliberating and acting upon their own individually held, though interdependent, mental states’[136]. According to Bratman, if one actor X has a set of behaviours x which generate an action-type, and if another actor Y also has a set of behaviours y that also establish an action-type, it follows that when actors X and Y undertake a joint action J it is necessarily an aggregate that we can term {Xx, Yy}. Moreover, we can also hold that because of this compositionality of action-types that any joint actions J is always {Xx, Yy} i.e. the aggregate set. This means that all joint action-types are always reducible to a set of behaviours undertaken by members of the group that performed it. This is important in terms of matters of culpability in joint enterprise cases where responsibility may not be simply transferred to the group or joint action. Bratman’s we-actions theory can be contrasted with Kutz’s highly elaborated ‘participatory intentions’ theory, which was introduced in the previous chapters. However, Kutz’s theory is deemed unsatisfactory in that it problematizes individual agency[137].

Bratman considers shared intention as the basis of we-actions, or collective action. Actors are involved in the collective action of J-ing only when they share the same intention to J and where J is voluntary and un-coerded. Citing Bratman’s standard technical formula, we intend to J if and only if:

- (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J;

- I intend that we J in accordance with and because of 1a, 1b, and meshing sub-plans of 1a and 1b; you intend that we J in accordance with and because of 1a, 1b and meshing sub-plans of 1a and 1b;

- 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us[138]

The main objective of we-action theories is to determine the goal of a given actor by asking questions about the content of their intentions in relation to the group. By assessing the goals of all actors in relation to the group we can then determine whether the group acted with shared intentions, or goals, and ascertain whether the aggregate of all actions amounts to a ‘we-action’. Conversely, if the members of a group cannot be said to share intentions, then their team goals cannot be understood as cooperatively structured, and the aggregate of their actions cannot be understood as a we-action, or collective action. Sharing an intention, or goal, is thus stronger than holding an intention, or goal, collectively. The strength of this notion of goal sharing is determined by three elements which characterise shared activity, besides shared intentions: first, a commitment to mutual support; second, a commitment to joint activity and finally, what Bratman terms as ‘mutual responsiveness’. These conditions are comparable to Feinberg’s ‘high degree of antecedent group solidarity’ condition which he claims is essential to hold a group collectively liability. The combination of shared intentions and these ‘three conditions’ distinguishes (SCA) shared cooperative activity, or collective action, from merely (JIA) jointly intentional activity, or joint action[139]: it is argued, that actors who adhere to a team goal are far more committed than actors who are merely engaged in basic joint intentional activity. Conclusively, if the group can be said to engage in shared cooperative activity, then it may be held collectively liable for the actions of one or a few of its members, so long as they all share the end goal, intention, or purpose. Contrariwise, if the group does not share team goals and does not engage in shared cooperative activity, it will not be possibly held collectively liable.

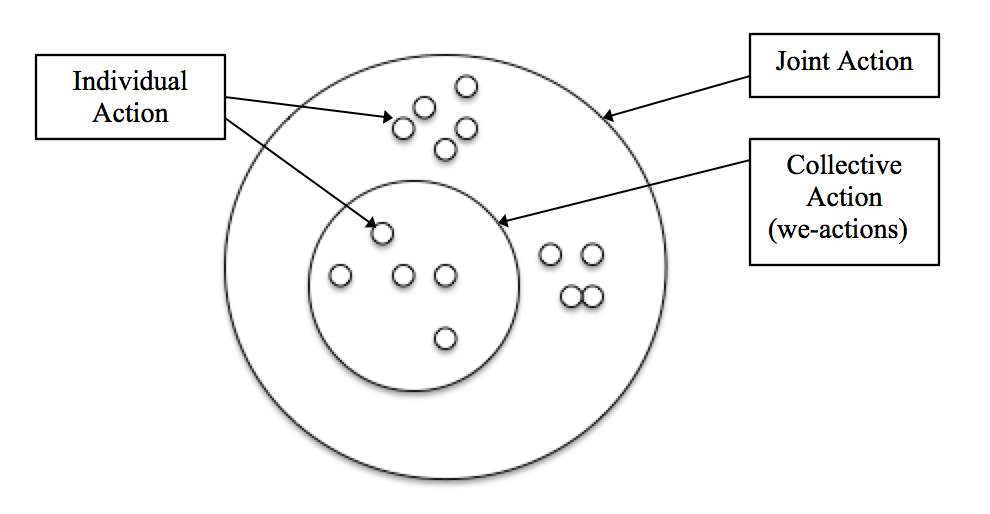

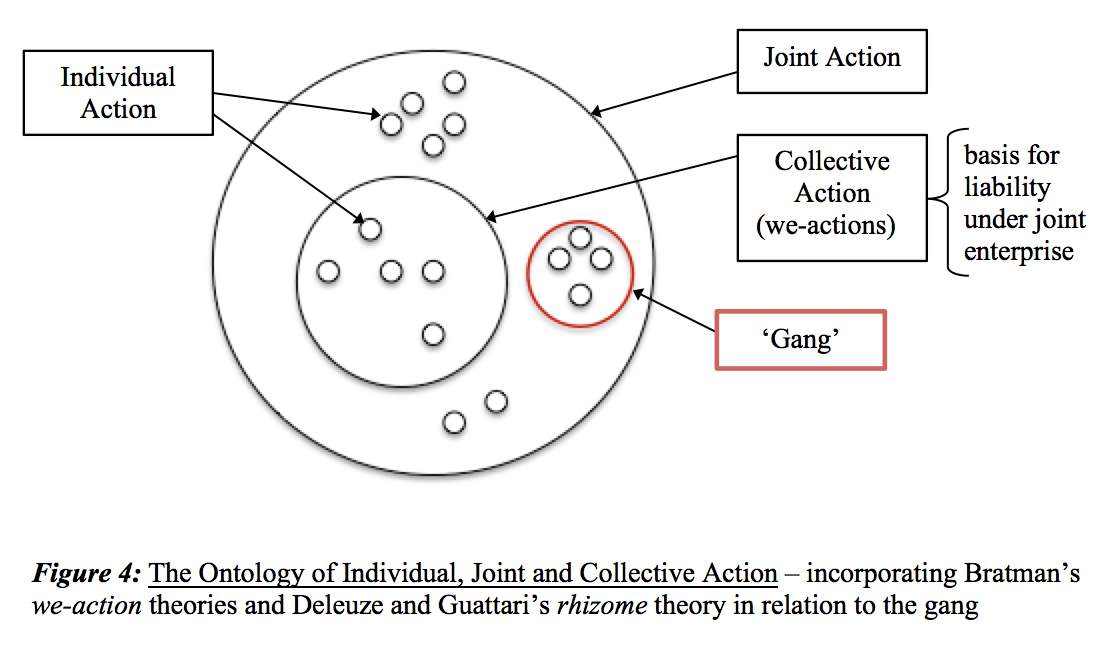

Figure 1: The Ontology of Individual, Joint and Collective Action – Bratman’s Theory

Bratman’s theory, as exposed by Amatrudo, offers a template by which the criminal justice system can determine the ‘collectiveness’ of a group’s actions before deciding whether to impose collective liability on all members of the group, or instead hold members individually liable for their own actions. If the group can be said to share intentions or goals, and more formally, a purpose, and if its members are fully committed to mutual support and responsiveness in the achievement of such purpose, team goals will be said to be cooperatively structured and the group may be held collectively liable for its actions. In cases concerning joint criminal enterprise, Bratman’s theories offer the most satisfactory template by which to determine the culpability of defendants in multi-agent cases, as it allows for a group to be held collectively liable without problematizing individual agency.

4.4 The Ontology of the Gang

Once a template by which to determine matters of responsibility and collectiveness has been construed, criminal justice practitioners, namely the police, prosecutors and the courts, not only can, but also have a duty to juxtapose with the template all groups involved in multi-agent cases, in order to establish whether these can be held collectively liable. The group-type most targeted by the joint enterprise doctrine, which is over-recorded in police lists, prosecutorial evidence and judges dictums, is the ‘gang’. Because of the label’s correlation with race and ethnicity in public discourse, it has become imperative that ‘the gang’ ceases to be over-criminalised. So far, this paper has sought to find the source of the disproportionate conviction of black and ethnic minorities in joint enterprise cases, and now it seeks to provide a solution. It is argued that ‘an appreciative ethnographic approach and one sensitive to the values and meanings actors give to their intentions and actions’[140] has become a necessity to re-orientate the discussion and to understand the reality of street organisation. Through this approach, it will be suggested that the ‘gang’[141] is, by definition, unstructured, ephemeral and mercurial, and its members disorganised in their decision-making and action-planning. The overarching conclusion is, after juxtaposing the ‘gang’ with our template for determining collective action, that the ‘gang’ cannot be understood as an aggregate of individuals acting collectively towards a common purpose, and thus cannot be held collectively liable. Conclusively, once the reality of street organisation is disassociated from the ‘highly structured, well-organised and hyper-violent’ representation of the gang, the police, the prosecution and the courts will be able to appropriately and efficiently tackle street violence without over-criminalising black youths under joint enterprise law.

Marking an epistemic break with ‘voodoo criminology’ and orthodox gang-talking tradition, Hallsworth’s ethnographic approach proposes to engage with Deleuze and Guattari’s theory[142] to comprehend the properties of informal street organisations. Philosophers Deleuze and Guattari developed the philosophical concept of rhizomes in their Capitalism and Schizophrenia project, based on the botanical rhizome, and seeking to apprehend multiplicities. In botany, a rhizome is the modified subterranean stem of a plant, often sending out roots and shoots from its nodes. Multiplicities, Deleuze argues, “are not parts of a greater whole [the One] that have been fragmented, and they cannot be considered manifold expressions of a single concept or transcendent unity”[143]. This same concept is what underpins the theory of the rhizome: unlike trees, rhizomes are non-hierarchical, decentred and distributed, so their ramifications cannot be considered ‘expressions’ of a ‘transcendent unity’. To clarify their account, Deleuze and Guattari set out certain approximate characteristics or principles defining the rhizome: first, under the principles of connection and heterogeneity, “a rhizome ceaselessly establishes connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences, and social struggles”[144]. This suggests that the links that connect rhizomes to one another, unlike trees, are each of a different nature, building different relationships and statuses between them. Second, according to the principle of multiplicity, “it is only when the multiple is effectively treated as a substantive, ‘multiplicity,’ that it ceases to have any relation to the One […]”[145]. Multiplicities are, indeed, rhizomatic. Third, the principle of asignifying rupture entails that “every rhizome contains lines of segmentarity according to which it is stratified, territorialised, and also […] deterritorialised”[146]. By this, interestingly, Deleuze and Guattari mean that the rhizome is an ‘anti-genealogy’, inherently non-hierarchical, which breaks apart and is reconstructed in continuum. Fourthly, the principles of cartography and decalcomania state that rhizomes are not amenable to any structural or generative models: “a genetic axis is like an objective pivotal unit upon which successive stages are organised; a deep structure is more like a base sequence that can be broken down into immediate constituents, while the unit of the product passes into another, transformational and subjective, dimension”[147]. This goes back to the principle of multiplicity analysed by Deleuze according to which the parts of a rhizome cannot be considered “manifold expressions of a single concept or transcendent unit”. Rhizomes, in short, cannot be understood as a collective but as an aggregate of individual parts.

Transposing the theory of the rhizome into ethnography and cultural criminology, Hallsworth offers a more accurate interpretation of the reality of the street world[148]. The gang, he claims, is rhizomatic, as opposed to arborescent. By arborescent, Hallsworth means tree-like, hierarchical, structured and closely interconnected. Many Western organisations are inherently arborescent: the structure of the state is arborescent, as well as that of political parties, corporations, etc. Rhizomes, unlike the tree, develop horizontally, they may be cut into pieces and each piece will form a new plant: they are non-hierarchical, decentred and distributed. The informal world of the street, Hallsworth agues, is rhizomatic in that gang structures are radically informal and non-hierarchical: “the organisational goals are less pre-planned and more situationally determined and driven, where personal and business imperatives often overlap and blur, sometimes with tragic outcomes”[149]. It is precisely this lack of shared intentions which characterises the gang as unstructured, disorganised.

Figure 2: Not The Street

Figure 3: The Street

‘Gang life’ is inherently unstable in what regards membership or association to the gang, even despite achieving a degree of formality on relation to the organisation. In transposing Deleuze and Guattari’s principles defining the rhizome, it is easy to draw obvious comparisons: the relationship between each and all of the people called ‘gang members’ is special, in that some of the them will be at the core of the ‘gang’ and others at the periphery, and their positions within the gang differ in status of proximity or closeness. Moreover, gangs are multiplicities, ephemeral and mercurial aggregates of individuals, and never a clearly defined ‘One’. Furthermore, the gang is ‘anti-genealogy’, in the sense of non-hierarchical, unstable, in the sense that connections can be broken and reconstructed at any moment, and not amenable to a structural model. Hallsworth’s account is ontologically superior in that it offers a more thorough depiction of the gang’s typology and the interrelationships of its members. In brief, Hallsworth’s ethnographic approach, as opposed to traditional gang-talk theories, is sensitive to the values and meanings actors give to their actions and intentions, offering a more accurate picture of the reality of street worlds, which, incidentally, conflicts with the nature of collective liability that is required under joint criminal enterprise law.

4.5 Conclusions: Juxtaposing, Comparing and Contrasting

The typology of the gang, in accordance with an ontologically superior ethnographic account which takes into consideration the intentions and actions of its individual members, is thus informal and non-hierarchical, its organisational goals are less pre-planned and more situationally determined, and each member ‘plays on their own’. The members and peripherals of a gang are not, as the prosecution often claims in joint enterprise cases, ‘in it together’, sharing a common purpose.

As represented in Figure 4, members of a so-called ‘gang’ can be said to act jointly intentionally, but not collectively. The structure of a ‘gang’, or street organisation, does not, contrary to public belief, provide a platform for its members to commit to mutual support in the execution of their ‘shared intentions’ or team goals. The typology of the gang is disorganised, ephemeral, and mercurial. This is so because, as it has been argued, the gang, as an ontological, highly structured organisation, does not exist in the UK. The gang is, instead, a label that is recurrently attributed to groups of friends, or acquaintances, often black, often male, and often deprived. Like any other group of friends or acquaintances, some will be at the core and some will be peripheral, some will get into trouble and some will not, and it would be difficult to argue that groups of friends normally ‘share a common purpose’ or intention towards which they all work cooperatively. This does not mean, of course, that some groups which are identified in the ‘gang matrix’ aren’t part of the problem of street violence in the UK. The main point here is that being considered violent and criminal because of who you are, and who you associate with, only leads to miscarriages of justice and fails to properly tackle the problem of street violence.

Figure 4 also illustrates this paper’s overarching conclusion: by juxtaposing ‘gangs’ with Bratman’s template for collective, joint and individual action, it is possible to conclude that gangs ‘pertain’ to the realm of joint, and not collective, action. Collective action, as has been established, is the basis for liability under joint enterprise: collective liability. In this way, it is argued that gangs, as an ontological entity, should not be held collectively liable under the law of joint enterprise

4.6 Policy Recommendations and Implications for BAME groups and Street Violence