Impact Measurement Tools for Social Enterprises: Use and Efficiency

Info: 10140 words (41 pages) Dissertation

Published: 22nd Dec 2021

Tagged: Business

Abstract

This paper explores and clarifies the significance of social entrepreneurship, its impact and the existent measurement tools. The measurement of inputs in social enterprises have improved in time, however, the measurement of outputs and the impact that social enterprises have is still primitive. This is problematic for entrepreneurs and investors because they require proper ways to measure in order to know if their resources are being used correctly and generating actual changes in their environments.

Keywords: Measurement tools, social entrepreneurship, social impact

Table of contents

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social entrepreneurship

2.2. Impact

2.3. Measurement tools

2.4. Efficiency

3. Future work

4. References

1. Introduction

Social entrepreneurship has been on the rise in the recent decades. A partial indicator of this surge is revealed by the growth in the number of nonprofit organizations, which increased by 31% between 1987 and 1997 (Austin, Stevenson, & Wei-skillern, 2006). The measurement of inputs as the investment that a social enterprise needs, has improved over the last decade (Flynn & Hodgkinson, 2013). Contrary to that, available data on outputs, outcomes, and impact are very primitive or nonexistent (Flynn & Hodgkinson, 2013). This could be due to the modest influence individual organizations have on the social objectives they are designed to address (e.g., eradicating poverty), making it nearly impossible for a single organization to be successful (Flynn & Hodgkinson, 2013) or to measure the individual impact that it has, excluding the impact of other entities that are working on the same objective.

There is also an increasing pressure for social organizations to be both more accountable by investors and other resource providers, as well as to systematically evaluate their performance (Chmelik, Musteen, & Ahsan, 2015); thus indicating the need for social impact measurement. Social organizations are clearly feeling more pressure to evidence their social value, as the funding and commissioning landscape evolves and grows more competitive(Clifford, Markey, & Malpani, 2013).

Identifying the use and efficiency of measurement tools that detect the impact of social enterprises will allow entrepreneurs and investors know if the use of their resources as money and time is being use in the most efficient way. Meaning that, if this investment is in the manner that gives the best returns in terms of social and economic impression in the correspondent environment.

Social enterprises are those for-profit businesses with shareholders who are interested in preserving their capital but not earning financial dividends or profits in the normal sense. Rather, they seek social profit in the form of positive, measurable impacts on societal problems such as poverty, ill health, illiteracy, and environmental degradation. If profits are earned, they are plowed back into the enterprise to do more good for society (Counts, 2008).

This is the definition that Muhammad Yunus gives. He is a banker and an economist who was awarded in 2006 with the Nobel Peace Prize for founding the Grameen Bank and pioneering the concepts of microcredit and microfinance (Counts, 2008). Although there are non-profit social enterprises, for this research we are only going to use for-profit enterprises that fit in the Yunus definition.

The reasons why we choose to work only with for-profit organizations are because over time, nonprofits alone have proven to be an inadequate response to social problems (Yunus, 2007). As they rely on donations by generous individuals, organizations, or government agencies, when these funds fall short, the good works stop (Yunus, 2007), what don’t happen in a for-profit enterprise. For other part, the need that have to constantly raise funds from donors uses up the time and energy of nonprofit leaders, when they should be planning the growth and expansion of their programs (Yunus, 2007). This use of time and energy reduces their efficiency and for then, their impact in the society. For other part, as Speckbacher (2003) expresses, measurement tools in social enterprises have often been brought over from the commercial business industry, meaning they were designed from a profit-based perspective (Chmelik et al., 2015). Profitability is important to a social enterprise. Wherever possible, without compromising the social objective (Yunus, 2007). Social enterprises should make profit to pay back its investors; and to support the pursuit of long-term social goals (Yunus, 2007)

There are plenty impact measurement tools that achieve to “quantity” the different kind of impact than an enterprise can generate in their environments. For example the matrix of impact measurement and the accounting tool Social Return on Investment (SROI). In the case of social enterprises, some of this measurement tools have been adapted for commercial enterprises including the social factor, and some of them have been elaborated specifically for social enterprises trying, for example, to monetize the variables.

Assessing social performance and impact is one of the greatest challenges for practitioners and researchers in social entrepreneurship (Mair & Marti, 2006). These because the social mission of social entrepreneurships cannot rely only on relatively tangible and quantifiable measures of performance such as financial indicators, market share, customer satisfaction, and quality as commercial enterprises do (Austin et al., 2006). But, the real problem is not the measurement, but how the measures may be used to “quantify” the performance and impact of social entrepreneurship (Mair & Marti, 2006).

The principal aim of this paper is to answer the research question “What impact measurement tools are most favorable for social enterprises?” To do that, we first need to identify and explore the existing impact measurement tools for social enterprises, then set parameters of efficiency and then identify the most efficient tool.

2. Literature Review

For this research, is important to clarify the definition of some key concepts in order to have clear limits of the scope. The procedure to select the articles to review for this research has been choosing the 10 most highly cited articles based in the information of the database of Harzing’s Publish & Perish software (Harzing, 2007). The selection has been made in the bases of the use of the terms entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship, measurement tools for enterprises and efficiency.

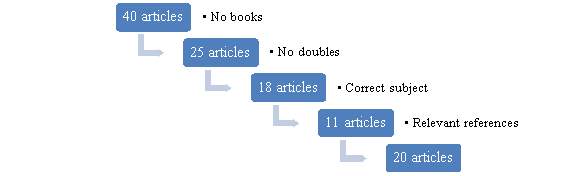

Of these forty results, I have excluded all the books, leaving twenty five articles to review. Of these twenty five articles, some of them were overlapped; excluding this resulted in eighteen unique articles. After reading the abstracts and introductions, seven more articles were excluded because they reached different topics. A more detail review was made to the eleven resulting articles for the elaboration of the present paper. While reviewing them, and for relevant references in those articles, more articles were included to the research reaching twenty articles at the end (Appendix 1).

Figure 1. Literature Review Diagram

2.1. Social entrepreneurship

Austin, Stevenson and Wei-Skillern base their research on the difference between social and commercial entrepreneurship and in what is a problem for the commercial entrepreneur is an opportunity for the social entrepreneur (Austin et al., 2006), because the market failure in which some needs of society do not give the revenue that a commercial entrepreneur is looking for and give the space to a social entrepreneurship. Social entrepreneurship appears to be a source of new and innovative solution to persistent social issues that private and public sectors have failed to address (Wulleman & Hudon, 2016).

This takes us to another difference and probably the most important one, the mission of a social entrepreneur. As Hoogendoorn, Pennings and Thurik express, despite the differences between the various schools of thought within the field of social entrepreneurship, there is agreement on the emphasis on the social mission as the reason to be of a social enterprise (Hoogendoorn, Pennings, & Thurik, 2010).

As Hoogendoorn et al. express that despite the growing attention to social entrepreneurship and similarities between various theories, no agreement exists on what it is or is not (Hoogendoorn et al., 2010). Probably, because the most tricky element about social entrepreneurship is the ability to combine elements of business and volunteer sectors and this combination represent the greatest obstacle to the definition of the field (Certo & Miller, 2008), that is why a proper definition of social enterprise should incorporate both economic and social outcomes (Zahra, Gedajlovic, Neubaum, & Shulman, 2009).

This mission is related with the position of the EMES. The Emergence des Enterprises Sociales en Europe (EMES), which is an European Research Network founded by the European Commission, has the conception that social enterprise and social impact on the community is not just a consequence or a side-effect of the economic activity but it is the key motive of the latter. This is also the reason that has justified the development of new legal forms, across Europe, for companies driven by social goals, being considered as part of the third sector (Defourny & Nyssens, 2010).

The EMES defined a set of indicators that any social enterprise should follow in order to be qualified as one. Such indicators were never intended to represent the set of conditions that an organization should meet to qualify as a social enterprise, but describe an abstract construction that enables researchers to position themselves within the ‘galaxy’ of social enterprises (Defourny & Nyssens, 2010). These conditions include four criteria that reflect the economic and entrepreneurial dimensions of social enterprises and five other indicators that encapsulate the social dimensions of such enterprises (Table 1) (Defourny & Nyssens, 2010).

| Criteria that reflect the economic and entrepreneurial dimensions of social enterprises | Criteria that encapsulate the social dimensions of social enterprise |

| A continuous activity producing goods and/or selling services | An explicit aim to benefit the community |

| A high degree of autonomy | An initiative launched by a group of citizens |

| A significant level of economic risk | A decision-making power not based on capital ownership |

| A minimum amount of paid work | A participatory nature, which involves various parties affected by the activity |

| A limited profit distribution |

Table 1: Indicators that a social enterprise should follow (Defourny & Nyssens, 2010)

These kinds of tools to identify if an enterprise qualified as social enterprise are necessary because there are a lot of terms used to describe entrepreneurial behavior with social aims. Some examples of this are ‘non-profit venture’, ‘non-profit entrepreneurship’, ‘social-purpose endeavor’, ‘social innovation’, ‘social-purpose business’, ‘community wealth enterprise’, ‘public entrepreneurship’, ‘social enterprise’, among others (Defourny & Nyssens, 2010).

Dees and Anderson divided these concepts in two schools of thought (Dees & Anderson, 2006). The first one is the “Earned Income” School of Thought that refers to the use of commercial activities by non-profit organizations in support of their mission (Defourny & Nyssens, 2010). The second school is called the “Social Innovation” School of Thought, in which the emphasis is put in the social entrepreneurs as change makers that carry out ‘new combinations’ in at least one the following areas: new services, new quality of services, new methods of production, new production factors, new forms of organizations or new markets. Social entrepreneurship can therefore be a question of outcomes and social impact rather than a question of incomes (Defourny & Nyssens, 2010).

Following this, for the ongoing research is going to be used the definition of social entrepreneurship made by Muhammad Yunus, which follows the social mission that we had discussed before. Also, even that social enterprises can be for-profit, NPO’s, hybrids, in the private or public sector (Wulleman & Hudon, 2016), with Yunus definition this is going to be filter in only for-profit businesses to have a clearer result of the impact that independent companies can have by their own. A social enterprise is a for-profit business with shareholders who are interested in preserving their capital but not earning financial dividends or profits in the normal sense. Rather, they seek social profit in the form of positive, measurable impacts on societal problems such as poverty, ill health, illiteracy, and environmental degradation. If profits are earned, they are plowed back into the enterprise to do more good for society (Counts, 2008).

As is also important to consider that the conceptions of social enterprise and social entrepreneurship are deeply rooted in the social, economic, political and cultural contexts in which these organizations emerge (Defourny & Nyssens, 2010). This means that to have a definition for the research, is important to delimitate a geographic space in which we could have a relatively similar social, economic, political and cultural context, this research is going to base all the analysis to Brussels, Belgium, considering that the results can be comparable to similar contexts.

This definition has been chosen because it includes the social mission which is an agreement in all definitions, but also because clarifies that in order to be consider a social entrepreneurship it must be a for-profit business, which differentiate this kind of entities from others that also have social mission but acquire their resources from donations. As non-profit business may apply as social entrepreneurships, in this study, and in order to analyze the impact, entities that don’t generate their own resources are going to be excluded.

2.2. Impact

The Cambridge and the Oxford dictionary define impact as a powerful effect that something (especially something new) has on a situation or person. Appling this concept to social entrepreneurship, it will be the effect that the social enterprise has in the environment in which it is involved and the population that lives there in a defined period of time.

The environment impact can be divided in six areas according to Harvard Professor Francis Aguilar in his proposed tool PESTEL. Those areas are Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental and Legal (Aguilar, 1967). Alvord, Brown, and Letts (2004) explore the primary areas of impact of the social enterprises under study. They distinguish between three areas of social impact: economic, cultural and political (Hoogendoorn et al., 2010). The most common areas of social impact for the target groups are the economic and cultural areas, while impact in the political area is less common (Hoogendoorn et al., 2010).

For other part, Burriet et al. said that corporations can only have a positive or negative impact upon the society along three dimensions: environmental, economic and social (Burritt, Schaltegger, Bennett, Pohjola, & Csutora, 2011). The conglomeration of this three dimension conform the term social impact (Burritt et al., 2011). Clark et al. define social impact as the portion of the total outcome that happened as a result of the activity of an organization, above and beyond what would have happened anyway (Burritt et al., 2011). It can be measured at three different levels: individual, corporation and societal (Burritt et al., 2011).

The Social Enterprise East of England (SEEE) define social impact measurement as the process by an organization provides evidence that its services are providing real and tangible benefits to people or the environment (Stevenson, Taylor, Lyon, & Rigby, 2010). Impact measurement is the means of demonstrating the benefits that the social enterprise is generating through evidence of social outcomes/impacts. This requires systematic, effective and appropriate measurement of their social contribution and which, hopefully, demonstrates competitive advantage over alternative providers (McLoughlin et al., 2009).

Analogous to financial accounting methods, environmental and social accounting methods aim to measure the impact of corporate activities on society. Such social and environmental impacts are often not expressed by the market, do not have a market value, and are therefore often ignored by corporations (Elkington 1999, Lamberton 2005, Schaltegger and Burritt 2000) (Burritt et al., 2011).

Consequently, the challenge for any nonprofit, nongovernmental, or for-profit, is to optimize impacts on several dimensions instead of maximizing impacts against a single dimension (Burritt et al., 2011). The process of social impact measurement requires discretion on behalf of those who carry out the process: choice regarding indicators, methods for data collection, judgments regarding what can be defined as success and failure, and finally using discretion at the point of disclosure of results (Lyon & Arvidson, 2011). Only this discretion will make the results reliable.

Impact measurement can be seen as both a bureaucratic form of regulation that allows others to control an organization through performance management or as a form of marketing for organizations with entrepreneurial skills (Lyon & Arvidson, 2011). The context, availability of data and nature of intervention need to influence the setting of impact metrics, but also that practicality is more important than trying to establish the ‘perfect’ metric (Clifford et al., 2013). What can be perfect for one situation, may give an erroneous result for other. Measuring impact may be a way of building and enhancing trust, but it is also closely interlinked with exerting control by funders (Lyon & Arvidson, 2011).

The data collection process is highly varied and depends on the objectives of the organization. However, in contrast to conventional financial accounting, the indicators or social impact can be highly subjective (Lyon & Arvidson, 2011). The range of assumptions that need to be made in any social impact measurement process provides organizations with ‘room to maneuver’ which can be an important source of power to influence others and as a form of resistance to those traditionally considered more powerful. This flexibility allows them discretion at several points of the measuring process (Lyon & Arvidson, 2011). Also, is the reason why measuring and comparing the impact between social enterprises may not give real results because all the assumptions that have to be made in the process.

For this research, the dimensions to be considered in impact that social enterprises can have in society will be economic and social impact. This two kind of impacts are selected because are included into the most important factors for most of the reviewed researches. However, there is no single tool or method that can capture the whole range of impacts or that can be applied by all corporations (Burritt et al., 2011).

2.3. Measurement tools

Based in Nicholls (2005) and Austin et al. (2006) there are plenty tools to measure the impact that social enterprises have in their environment, but social and environmental values are hard to include in impact measurements. In response to such challenges, approaches are being developed for measuring value other than financial. Numerous qualitative and quantitative ‘social metrics’ have been developed within academia in recent years to measure social impact (Ormiston & Seymour, 2011). These methods have been developed in response to the changing needs for management information resulting from increased interest of corporations in socially responsible activities (Burritt et al., 2011).

Maas and Liket (2011) developed a scientific investigation in which analyze and categorize thirty contemporary social impact measurement methods in the following dimensions: purpose, time frame, orientation, length of time frame, perspective and approach(Burritt et al., 2011). The social measurement methods that they analyze are in appendix 2. However, they conclude that the classification clearly illustrates the need for social impact methods that truly measure impact, take an output orientation and concentrate on longer- term effects (Burritt et al., 2011). For them, only eight out of the thirty methods truly measure impact (Burritt et al., 2011). These eight methods are in appendix 3 and in addition some other methods were collected for other authors in appendix 4.

The Bottom of the Pyramid (BoP) Impact Assessment Framework was developed by Ted London in 2007. The aim is to understand who at the base of the pyramid is impacted and how they are affected. The framework is developed to evaluate and articulate impacts, to guide strategy and to enable better investment decisions (Burritt et al., 2011). It also helps to understand the relationship between profits and poverty alleviation.

The Measuring Impact Framework is developed in 2008 by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development. It is designed to help corporations understand their contribution to society. The framework is based on a four-step methodology that attempts to merge the business perspectives of its contribution to development with the societal perspectives of what is important where that business operates (Burritt et al., 2011). There is no “one size fits all” way to use this methodology. In order to appropriately tailor the methodology to the business and its context, corporations are encouraged to make the assessment as participative as possible, consulting people both within and if possible external to the corporation(Burritt et al., 2011).

The Ongoing Assessment of Social Impacts (OASIS) was developed in 1999 by The Roberts Enterprise Development Fund. They developed it to assess the social outputs and outcomes of the agencies overall, including the social enterprises they operated (Burritt et al., 2011). The system is a customized, comprehensive, ongoing social management information system. It entails both designing an information management system that integrates with the agency’s information tracking practices and needs, and then implementing the tracking process to track progress on short- to medium term (two years) outcomes (Burritt et al., 2011).

The Participatory impact assessment was developed by the Feinstein International Center. They have been adapting participatory approaches to measure the impact of livelihoods based interventions since the early nineties (Burritt et al., 2011). Participatory Impact Assessment (PIA) takes the participatory methodology of these processes and applies it to the original corporation objectives in asking the critical questions “what difference are we making?” PIA offers not only a useful tool for discovering what change has occurred, but also a way of understanding why it has occurred. The framework does not aim to provide a rigid or detailed step by step formula, or set of tools to carry out project impact assessments, but describes an eight stage approach, and presents examples of tools which may be adapted to different contexts (Burritt et al., 2011).

The Poverty Social Impact Assessment (PSIA) has been developed by the World Bank in 2000. It is not a tool for impact assessment in and of itself, but is rather a process for developing a systematic impact assessment for a given project (Burritt et al., 2011). The method emphasizes the importance of setting up the analysis by identifying the assumptions on which the program is based, the transmission channels through which program effects will occur, and the relevant stakeholders and institutional structures. Then program impacts are estimated, and the attending social risks are assessed, using analytical techniques that are adapted to the project under study (Burritt et al., 2011).

The Robin Hood benefit–cost ratio was developed by the Robin Hood Foundation in 2004. First of all, this method uses a common measure of success for programs of all types: how much the program boosts the future earnings (or, more generally, living standards) of poor families above that which they would have earned in the absence of Robin Hood’s help (Burritt et al., 2011). Second, a benefit/ cost ratio is calculated for the program—dividing the estimated total earnings boost by the size of Robin Hood’s grant. The ratio for each grant measures the value it delivers to poor people per dollar of cost to Robin Hood—comparable to the commercial world’s rate of return (Burritt et al., 2011).

Social cost-benefit analysis (SCBA) is a type of economic analysis in which the costs and social impacts of an investment are expressed in monetary terms and then assessed according to one or more of three measures: (1) net present value (the aggregate value of all costs, revenues, and social impacts, discounted to reflect the same accounting period; (2) benefit-cost ratio (the discounted value of revenues and positive impacts divided by discounted value of costs and negative impacts); and (3) internal rate of return (the net value of revenues plus impacts expressed as an annual percentage return on the total costs of the investment (Burritt et al., 2011).

Social Impact Assessment (SIA) includes adaptive management of impacts, projects and policies and therefore needs to be involved in the planning of the project or policy from inception (Burritt et al., 2011). The SIA process can be applied to a wide range of interventions, and undertaken at the behest of a wide range of actors, and not just within a regulatory framework. SIA is also understood to be an umbrella or overarching framework that embodies all human impacts (Burritt et al., 2011).

Kaplan and Norton (1996, 2001) originally designed the balanced scorecard performance measurement method for private sector organizations(McLoughlin et al., 2009). The balanced scorecard proposes that corporations measure operational performance in terms of financial, customer, business process, and learning-and-growth outcomes, rather than exclusively by financial measures(Clark, Rosenzweig, Long, & Olsen, 2004). It helps coordinate evaluation, internal operations metrics, and external benchmarks, but is not a substitute for them (Clark et al., 2004).

It has been adapted by various authors and organizations as a social enterprise performance measurement tool. For example, “Balance” by Bull (2007), the Social Enterprise Balanced Scorecard (SEBS) by SEL (Somers, 2005), the Social Firm Dashboard by Social Firms UK (2008). This tool helps socially oriented organizations tell their story and effectively demonstrate value to their stakeholders (Chmelik et al., 2015).

SIMPLE was specifically designed to develop capabilities to systematically measure impacts of Ses which can also be used at a deeper level to support operations management and strategic decision making (McLoughlin et al., 2009). The five steps of this tool (Scope it, map it, track it, tell it and embed it) help social enterprise managers to conceptualize the impact problem; identify and prioritize impacts for measurement; develop appropriate impact measures; report impacts and to embed the results in management decision making (McLoughlin et al., 2009). It provides a conceptual and practical approach to measure impact that methodology can be adapted to all organizational sizes and enterprise sectors (McLoughlin et al., 2009).

SROI is a method to monetize social impact compared with relevant initial investment (McLoughlin et al., 2009). It try to explore how social change is achieved, and how change can be demonstrated and illustrated with the purpose of proving that value has been created (Arvidson, Lyon, Mckay, & Moro, 2010). SROI is an adjusted cost–benefit analysis that takes into account the various types of impact, including social and environmental benefits. As traditional cost-benefit analysis, SROI combines, in the form of a cash flow, the ratio of discounted costs and benefits over a certain period of time (Arvidson et al., 2010). The capability to monetize net social impacts is undoubtedly attractive to social enterprises as monetary measures are clearly understood, so they can demonstrate their competitive advantage and allow potential comparability. However, not all impacts can be reduced to monetary measure and it is difficult to apply (McLoughlin et al., 2009).

SAA is mostly qualitative using descriptive metrics to report on populations served and impacts made (Chmelik et al., 2015). It can be adjusted to have differing degrees of detail and can also include elements of other approaches such as SROI (Stevenson et al., 2010). The defining element is the emphasis on audit by an independent panel with at least one trained audit professional(Stevenson et al., 2010). The stages set out by the Social Accounting Network (2008) include: involving everyone in the organization; social, environmental and economic planning, including the organization’s mission, aims and goals; consultation and gathering of data for social, environmental and economic accounting; establishing a panel of social, environmental and economic auditors, including independent professional auditors and a range of other interested organizations/parties, in order to ensure a robust process (Stevenson et al., 2010).

Social Wealth standard is imprecise and difficult to measure because many of the products and services that social entrepreneurs provide are non-quantifiable (Zahra et al., 2009). The task of determining social wealth is the subjective nature of social value itself, which varies greatly from one context to another, however social wealth standard offers a promising heuristic for evaluate social opportunities and ventures (Zahra et al., 2009). Adding social wealth with the economic factors we get the “total wealth” standard that can be useful for scholars, donors and practitioners as they evaluate both economic and social opportunities and ventures (Zahra et al., 2009). It can also provide a benchmark for evaluating the performance of economic and social ventures based on desired performance goals or performance relative to other organizations (Zahra et al., 2009).

PQASSO has it origin in quality movement, which has had mixed reviews from those who write about public and nonprofit management, organization, and policy (Paton, Foot, & Payne, 2000). PQASSO addresses sixteen different quality areas, such as user-centered service, the management committee, and the management of resources. For each of these the workbook sets out a standard, defines the terms used in the standard, sets out three levels of achievement, and suggests the sort of documentary evidence an organization might provide in order to show that it was consistently operating at that level (Paton et al., 2000). It is up to the organizations themselves to decide which areas are important for them and the levels they need to achieve (Paton et al., 2000).

There are some interesting patterns between the business model configuration and the type of performance measures used as related to focus on internal processes versus external outcomes, and focus on qualitative versus quantitative measures of inputs, outputs, and outcomes (Chmelik et al., 2015). First, those that focus on internal evaluation of the social venture are closely tied to decision-making and operations. The focus of these measures is inputs and outputs of social value ‘production’ and they often serve as means of achieving organizational control (Arvidson and Lyon 2014). Second, there are metrics that focus specifically on measuring social value creation and impact. Measures that have been created for impact investors who invest in businesses expecting not only financial return but also an SROI (Simon and Barmeier 2011). These performance measurements help determine which ventures will provide the most impact per dollar (Chmelik et al., 2015). Examples of measures focused on internal efficiency and effectiveness of the organization include the balanced score card (BSC), a well-developed business analysis tool, adapted to social ventures (Kaplan and Norton 1996; Kaplan 2001)(Chmelik et al., 2015).

Social enterprises do not use all of the performance measures available to them. They select performance measures based on their importance to organizational goals. Social enterprises not only select performance measures that help them enhance organization performance, gain legitimacy, or acquire resources; but the measurement choice is also influenced by other factors such as the degree of founders’ involvement in the ‘social’ aspect of their venture, organizational size, and business model(Chmelik et al., 2015). There is no single tool or method that can capture the whole range of impacts or that can be applied by all corporations (Burritt et al., 2011).

2.4. Efficiency

The Cambridge dictionary defines efficiency as the good use of time and energy in a way that does not waste any. For other part, the Oxford dictionary defines it as the state or quality of achieving maximum productivity with minimum wasted effort or expense and also as preventing the wasteful use of a particular resource.

Traditional economic defines efficiency as the ratio of desirable to undesirable impacts, based in this view; the economic interpretation of efficiency is based on monetary performance data and is expressed in profitability indicators (Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit Deutschland. Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Universität Lüneburg, Centre for Sustainability Management (CSM), & Schaltegger, 2002) . In the context of the goal of sustainable development, however, there is a need to complement this interpretation with social aspects, which they call social efficiency (Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit Deutschland. Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Universität Lüneburg, Centre for Sustainability Management (CSM), & Schaltegger, 2002)

Social efficiency can be defined as the ratio of value added to social impact added, where social impact added represents the sum of all negative social impacts originating from a product, process or activity. Examples of social efficiency yardsticks are value added[EUR]/personnel accidents[number] or value added[EUR]/absence due to illness[days]. Other efficiency types of a more technical nature are characterized by the fact that only non-monetary quantities are used in the ratio (e.g. hours worked[h]/personnel accident, or product units/emissions[t]). (Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit Deutschland. Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Universität Lüneburg, Centre for Sustainability Management (CSM), & Schaltegger, 2002)

Emerson (2003) defines efficiency as the measure of the relation between outputs and inputs of a process. The higher the output for a given input, or the lower the input for a given output, the more efficient the activity, product, or corporation is. The general understanding of both investment and return is founded upon a traditional separation of social value and economic value. However, the pursuit of a blended value for investments and returns does not separate social and financial impacts but is composed of both (Emerson 2003).

Coelli (1995) also separate efficiency in two components: technical efficiency, which reflects the ability of a firm to obtain maximal output from a given set of inputs, and allocated efficiency, which reflects the ability of a firm to use the inputs in optimal proportions, given their respective prices. These two measures are then combined to provide a measure of total efficiency.(Coelli, 1995)

Attempts have been made to construct “indices of efficiency”, in which a weighted average of inputs is compared with output (Farrell, 1957), however, to use them you need to do the assumption that the efficient production function is known. In other words, they are methods of comparing the observed performance of a firm with some postulated standard of perfect efficiency, so that each of the measures has, in general, corresponding to each postulated standard, a different value and a different significance.(Farrell, 1957)

For this research, we are going to use the definition of efficiency of the Oxford dictionary of preventing the wasteful use of resources. This definition is chosen because other definitions are oriented to companies, and for this research we need to measure the efficiency of measurement tools. We need to consider economic, human and time resources as those are the principal resources that any entrepreneurship have. The specific parameters to define the efficiency of a measurement tool will be the economic cost that the application of the tool have, the require human resources needed and the require time.

3. Future work

I will use a mixed method research combining qualitative and quantitative tools. The combination provides a more complete understanding of a research problem than either approach alone (Creswell, 2013). Both methods are going to be used because all methods had bias and weaknesses, and the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data neutralized the weaknesses of each form of data (Creswell, 2013).

The strategy of inquiry will be convergent parallel mixed method so quantitative and qualitative data will be collect roughly at the same time and then integrated in the interpretation of the overall results (Creswell, 2013). The principal research tool to be use will be surveys which can be used as a mixed method research because it will include open and closed questions (Creswell, 2013). Open questions will allow us to sustain the choices that the enterprises made and explain the reasons behind the answers in the closed questions.

First of all, the survey will collect basic information about the entrepreneurship, like the name and the time that is already working. Then, close questions will be used with multiple choice answers in which we will acquire de information about the quantity of the different resources that the entrepreneurships have. Then, the use of measurement tools, which tools they use and the frequency of use. Also, the quantity of resources that the entrepreneurship uses in order to apply the measurement tools. All this questions will be mixed with some open answer question.

The study population for this paper will be for profit social entrepreneurships of Brussels. The facility with this is that as being Brussels a developed ecosystem, is more probably to find enterprises that do use measurement tools, this because enterprises that don’t make use of them, might be excluded of the research. The difficulty is that it is a larger population, of which there is no data base to start the research, so a representative study might be improbably.

4. References

Aguilar, F. J. (1967). Scanning the business environment. (Macmillan, Ed.).

Arvidson, M., Lyon, F., Mckay, S., & Moro, D. (2010). The ambitions and challenges of SROI.

Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei-skillern, J. (2006). Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different or Both? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 1–22.

Burritt, R. L., Schaltegger, S., Bennett, M., Pohjola, T., & Csutora, M. (2011). Environmental management accounting and supply chain management. Springer Science & Business Media.

Certo, S. T., & Miller, T. (2008). Social entrepreneurship: Key issues and concepts. Business Horizons, 51(4), 267–271.

Chmelik, E., Musteen, M., & Ahsan, M. (2015). Measures of Performance in the Context of International Social Ventures: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 7(1), 74–100.

Clark, C., Rosenzweig, W., Long, D., & Olsen, S. (2004). Double bottom line project report: Assessing social impact in double bottom line ventures, Methods Catalog. Columbia Business School, Rise-Project.

Clifford, J., Markey, K., & Malpani, N. (2013). Measuring Social Impact in Social Enterprise : The state of thought and practice in the UK. London, E3M.

Coelli, T. J. (1995). Recent developments in frontier modelling and efficiency measurement. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 39(3), 219–245.

Counts, A. (2008). Small Loans, Big Dreams. Hoboken NJ Wiley.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Dees, J. ., & Anderson, B. . (2006). Framing a theory of social entrepreneurship: building on two schools of practice and thought. Research on Social Entrepreneurship: Understanding and Contributing to an Emerging Field, 1(3), 39–66.

Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2010). Conceptions of Social Enterprise and Social Entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: Convergences and Divergences. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 32–53.

Farrell, M. J. (1957). The Measurement of Productive Efficiency. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General), 120(3), 253–290.

Flynn, P., & Hodgkinson, V. (2013). Measuring the Impact of the Nonprofit Sector. Springer Science & Business Media.

Harzing, A. W. (2007). Publish or Perish. Retrieved December 10, 2016, from http://www.harzing.com/pop.htm

Hoogendoorn, B., Pennings, E., & Thurik, R. (2010). What Do We Know About Social Entrepreneurship : An Analysis of Empirical Research.

Lyon, F., & Arvidson, M. (2011). Social impact measurement as an entrepreneurial process.

Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 36–44.

McLoughlin, J., Kaminski, J., Sodagar, B., Khan, S., Harris, R., Arnaudo, G., & Brearty, S. M. (2009). A strategic approach to social impact measurement of social enterprises. Social Enterprise Journal, 5(2), 154–178.

Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit Deutschland. Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Universität Lüneburg, Centre for Sustainability Management (CSM), & Schaltegger, S. (2002). Sustainability management in business enterprises: concepts and instruments for sustainable organisation development. Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature conservation and Nuclear Safety-Division for Environment and Economy Eco-Aud.

Ormiston, J., & Seymour, R. (2011). Understanding Value Creation in Social Entrepreneurship: The Importance of Aligning Mission, Strategy and Impact Measurement. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 2(2), 125–150.

Paton, R., Foot, J., & Payne, G. (2000). What Happens When Nonprofits Use Quality Models for Self-Assessment? Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 11(1), 21–34.

Stevenson, N., Taylor, M., Lyon, F., & Rigby, M. (2010). Joining the Dots, Social Impact Measurement, commissioning from the Third Sector and supporting Social Enterprise development.

Wulleman, M., & Hudon, M. (2016). Models of Social Entrepreneurship : Empirical Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 7(2), 162–188.

Yunus, M. (2007). Creating World Without Poverty: Social Business and the future of capitalism. PublicAffairs.

Zahra, S. A., Gedajlovic, E., Neubaum, D. O., & Shulman, J. M. (2009). A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(5), 519–532.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Papers consulted for literature review

| YEAR | AUTHOR(S) | TITLE | JOURNAL | |

| 1 | 2006 | Austin, J. Stevenson, H. Wei-skillern, J. |

Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different or Both? | Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice |

| 2 | 2008 | Certo, S. T. Miller, T. |

Social entrepreneurship: Key issues and concepts | Business Horizons |

| 3 | 2016 | Wulleman, M. Hudon, M. |

Models of Social Entrepreneurship : Empirical Evidence from Mexico | Journal of Social Entrepreneurship |

| 4 | 2015 | Chmelik, E. Musteen, M. Ahsan, M. |

Measures of Performance in the Context of International Social Ventures: An Exploratory Study | Journal of Social Entrepreneurship |

| 5 | 2009 | Zahra, S. A. Gedajlovic, E. Neubaum, D. O. Shulman, J. M. |

A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges | Journal of Business Venturing |

| 6 | 2006 | Mair, J. Marti, I. |

Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight | Journal of World Business |

| 7 | 2013 | Clifford, J. Markey, K. Malpani, N. |

Measuring Social Impact in Social Enterprise : The state of thought and practice in the UK | London, E3M |

| 8 | 2006 | Dees, J. Anderson, B. |

Framing a theory of social entrepreneurship: building on two schools of practice and thought | Research on Social Entrepreneurship: Understanding and Contributing to an Emerging Field |

| 9 | 2013 | Flynn, P. Hodgkinson, V. |

Measuring the Impact of the Nonprofit Sector | Springer Science & Business Media |

| EXTRAS | ||||

| 10 | 1967 | Aguilar, F. J. | Scanning the business environment | |

| 11 | 2010 | Arvidson, M. Lyon, F. Mckay, S. Moro, D. |

The ambitions ad challenges of SROI | |

| 12 | 2008 | Counts, A. | Small Loans, Big Dreams | |

| 13 | 2010 | Hoogendoorn, B. Pennings, E. Thurik, R. |

What Do We Know About Social Entrepreneurship : An Analysis of Empirical Research | |

| 14 | 2007 | Yunus, M. | Creating World Without Poverty: Social Business and the future of capitalism | |

| 15 | 2010 | Stevenson, N.

Taylor, M. Lyon, F. Rigby, M. |

Joining the Dots, Social Impact Measurement, commissioning from the Third Sector and supporting Social Enterprise development | |

| 16 | 2011 | Ormiston, J.

Seymour, R. |

Understanding Value Creation in Social Entrepreneurship: The Importance of Aligning Mission, Strategy and Impact Measurement | Journal of Social Entrepreneurship |

| 17 | 2009 | Jim McLoughlin Jaime Kaminski Babak Sodagar Sabina Khan Robin Harris Gustavo Arnaudo Sinéad Mc Brearty, | A strategic approach to social impact measurement of social enterprises | Social Enterprise Journal |

| 18 | 2004 | Clark, C Rosenzweig, W Long, D Olsen, S. |

Double bottom line project report: Assessing social impact in double bottom line ventures, Methods Catalog. Columbia Business School, Rise-Project. | Columbia Business School, Rise-Project. |

| 19 | 1957 | M. Farrell | The Measurement of Productive Efficiency | Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General) |

| 20 | 1995 | T. Coelli | Recent developments in frontier modeling and efficiency measurement | Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics |

Table 2: Papers consulted for literature review

Appendix 2: Social impact measurement methods

Social Impact measurement methods |

| 1.Acumen scorecard |

| 2. Atkinsson compass assessment for investors (ACAFI) |

| 3. Balanced scorecard (BSc) |

| 4. Best available charitable option (BACO) |

| 5. BoP impact assessment framework |

| 6. Center for high impact philanthropy cost per impact |

| 7. Charity assessment method of performance (CHAMP) |

| 8. Foundation investment bubble chart |

| 9. Hewlett foundation expected return |

| 10. Local economic multiplier (LEM) |

| 11. Measuring impact framework (MIF) |

| 12. Millennium development goal scan (MDG-scan) |

| 13. Measuring impacts toolkit |

| 14. Ongoing assessment of social impacts (OASIS) |

| 15. Participatory impact assessment |

| 16. Poverty social impact assessment (PSIA) |

| 17. Public value scorecard (PVSc) |

| 18. Robin hood foundation benefit–cost ratio |

| 19. Social compatibility analysis (SCA) |

| 20. Social costs–benefit analysis (SCBA) |

| 21. Social cost-effectiveness analysis (SCEA) |

| 22. Social e-valuator |

| 23. Social footprint |

| 24. Social impact assessment (SIA) |

| 25. Social return assessment (SRA) |

| 26. Social return on investment (SROI) |

| 27. Socioeconomic assessment toolbox (SEAT) |

| 28. Stakeholder value added (SVA) |

| 29. Toolbox for analysing sustainable ventures in developing countries |

| 30. Wellventure monitor |

Table 3: Overview of social impact measurement methods (Maas and Liket, 2011)

Appendix 3: Methods that truly measure impact

| Tool | Purposes | Time Frame | Orientation | Length of Time Frame | Perspective | |||||||||

|

Screening |

Monitoring |

Reporting |

Evaluation |

Prospective |

Ongoing |

Retrospective |

Input |

Output |

Short term |

Long term |

Micro (individual) |

Meso (corporation) |

Macro (Society) |

|

| BoP impact assessment framework | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | X | x | ||

| Measuring impact framework (MIF) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | X | x | ||

| Ongoing assessment of social impacts (OASIS) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Participatory impact assessment | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Poverty social impact assessment (PSIA) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Robin hood foundation benefit-cost ratio | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Social cost-benefit analysis (SCBA) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Social impact assessment (SIA) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

Table 4: Classification of methods that truly measure impact (Maas and Liket, 2011)

Appendix 4: Impact measurement tools

| Tool | Author | Description | Advantage | Limitation |

| Balance scorecard for not-for-profits | McLoughlin et al., 2009 | Useful route to capture stakeholder perspectives, promoting internal process improvement and framing triple-bottom line impacts, assuming appropriate measures are developed. | There is scope to build on these balanced scorecard approaches as they focus on the internal processes and are essentially business performance analysis tools. | Tend to avoid external impact force analysis and do not outline in detail how to develop precise impact measures or how to implement impact measurement management systems. |

| Social Impact for Local Economies (SIMPLE) | Chmelik et al., 2015 | Strategic way of measuring performance that takes an organization through the process of determining impact measures to implement those measures into decision-making.

This methodology presents a five-step approach to measuring impact performance: scope it, map it, track it, tell it, embed it (i.e. SIMPLE). |

The five steps of the SIMPLE methodology were designed to eliminate complexity in order to create easily accessible parts for both management and training activities. | Problems distinguishing between outputs and outcomes, and then outputs to impacts. |

| Social Return on Investment (SROI) | Arvidson, Lyon, Mckay, & Moro, 2010. | Framework that identifies and appreciates social, economic and environmental value created. It involves reviewing the inputs, outputs, outcomes and impacts made and experienced by stakeholders in relation to the activities of an organization, and putting a monetary value on the benefits and dis-benefits created. | Its advantages lie in the ability to communicate impact and help decision making. | Difficulties in monetizing social impact, and the amount of resources and training that are required to carry it out (Stevenson et al., 2010).

SROI ratio is specific for each organization and hence does not lend itself to cross-organizational comparison. |

| Social Accounting and Auditing (SAA) | Stevenson et al., 2010

Chmelik et al., 2015 |

Well-developed evaluation technique that evaluates the performance of social, economic, and environmental objectives. | This technique can be as detailed as needed and can be combined with other metrics such as SROI. | It is not easily comparable against other organizations because it is highly individualistic. |

| Social Wealth | Zahra et al., 2009 | It measures the contributions of social entrepreneurship within the context of total wealth maximization. Total wealth comprises both economic and social wealth. It also takes into account the forgone costs of other opportunities not pursued. | Show how entrepreneurs can potentially shift resources in a manner that enhances wealth in one category at the expense of another. | Imprecise and difficult to measure because many of the products and services that social entrepreneurs provide are non-quantifiable. |

| Practical Quality Assurance System for Small Organizations – PQASSO | Stevenson et al., 2010 | It is a quality management system designed to assist organizations to run more effectively and efficiently, developed for the charity sector. It is only a partial social impact measurement toolkit. | It is particularly strong with regard to performance. It can be seen as a framework within which approaches to measuring impact can be integrated into management systems. | Weak on the specifics of how to undertake impact assessment. |

Table 5: Impact measurement tools reviewed

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Business"

The term Business relates to commercial or industrial activities undertaken to realise a profit including producing or trading in products (goods or services). A general business studies degree could cover subjects such as accounting, finance, management and increasingly, entrepreneurship.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: