An Interdisciplinary Investigation of the Gender Pay Gap

Info: 14035 words (56 pages) Dissertation

Published: 4th Jan 2022

Abstract

Using existing theories of the gender wage gap, this study investigates unconscious gender biases, the motherhood penalty, and the uneven distribution of unpaid household and childcare labor as the main forces persistently maintaining wage inequality. Theories aspiring to explain the pay gap often turn to highly simplistic justifications that fail to acknowledge the dynamic nature of our inherent biases, systematic constraints and societal assumptions about gender that contribute to the pay gap. This study complements existing research on wage inequality through surveys of 445 individuals with and without children, and interviews of mothers, fathers, and young adults who want children in the future. Controlling for gender and parental status, female survey participants with children take on significantly more childcare responsibilities than men, and their careers are jeopardized as a result. In conjunction, both childless male and female survey respondents assume most of the responsibilities associated with childcare to be predominately a woman’s responsibility, despite equal rates of career development and advancement goals.

Keywords: Motherhood penalty, unconscious gender bias, parental leave, gender pay gap

Table of Contents

Click to expand Table of Contents

Introduction

Aim of Study and Research Questions

Background Information

Parental Leave Policies Around the World

Existing Theories for the Gender Wage Gap

Unconscious Gender Bias

Negotiation Differentials

Corporate Sponsorship

The Motherhood Penalty

Research Methods

Survey Data

Interview Data

Description of Findings

Maternity and Paternity Leave

Career Advancement

Career Goals

Interpretation of Results and Conclusions

Implications and Next Steps

Limitations and Future Research

Appendix

Appendix A: Survey Questions for Childless Participants

Appendix B: Survey Questions for Parent Participants

Appendix C: Demographic Information Included in Both Surveys

References

Introduction

Aim of Study and Research Questions

My research aims to identify discrepancies between men and women in understanding and assuming childcare responsibilities in order to recognize inequalities at home (in unpaid labor) that may translate to inequalities in paid labor in the formal work sector. Furthermore, I aim to understand the differences between those who speculate about having kids, and those who have kids, in order to determine if the gendered division of labor often seen in families with children is the most efficient, or if it is an assumption forced onto women and men by society. In my study, the gendered division of labor occurs when specific tasks and jobs are allocated to either a man or a woman simply based on their gender i.e. women are responsible for household duties because they are women. And finally, I aim to understand the various challenges faced by working mothers. Drawing from these goals, I formed the following research questions:

- Why does the gender wage gap exist and what can we do to close the gap?

- How do women and men perceive the division of labor?

- Are women and men’s careers affected differently after having children?

- Do women and men have different career goals in terms of growth and advancement?

Background Information

Second-wave feminism in the 1960s and 1970s broadened the publics’ attitudes around education, family, the workplace and other gender inequalities, redefining women’s involvement in the public sphere, and helping reinvent the female identity. Today, both men and women are expected to pursue higher education and become financially independent, while only fifty years ago, over half of married mothers were primary caregivers and did not engage in paid labor in the formal sector (Parker & Livingston, 2016). Today, more women graduate from college than men and over 58% of women participate in the labor force (“Status of Women in the U.S.” 2017). Moreover, female engagement in the formal paid sector is associated with greater economic growth and development.

For example, companies with more women in leadership positions generate more profit (Noland et al., 2016), companies with ethnic and gender diversity are more innovative, and thus more competitive (Groysberg & Connolly, 2013) and companies with more female directors are associated with greater corporate sustainability (McElhaney & Mobasseri, 2012). Despite the clear economic advantages of women engaging in paid work, women experience a significant wage gap. Recent studies show that women make 20% less than men, controlling for education level and occupation, and this gap is even larger for women of color (“The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap” 2017). According to the National Partnership for Women and Families, on average, full-time employed women in the United States, in total, lose more than $840 billion every year, due to the wage gap. As a result, women have less money to support their families, themselves, and have less disposable income to support businesses (“America’s Women and the Wage Gap” 2017).

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, an increase in women’s human capital, education, and work experience has narrowed the earnings gap between men and women over the last few decades. However, the narrowing gap has significantly decelerated in recent years, suggesting other forces at play (Day, J. C., & Downs, B., 2007). According to economists and social scientists, 38% of the gender wage gap is completely unexplained (Blau, F., & Kahn, L., 2000) and, as I argue, potentially due to implicit and inherent biases, gender stereotypes, penalties associated with motherhood, and the unbalanced distribution of unpaid labor. Despite the shifting gender roles we have seen over the last 50 years, family planning, homecare and childcare is still severely gendered and unbalanced, creating a persistently unequal distribution of work, resulting in a continued earnings gap. Social scientists call this phenomenon the “second shift” describing the unpaid work mothers perform at home in addition to the paid labor they perform at work (Hochschild, A., & Machung, A., 2012).

Factors contributing to the wage gap, I argue, are a result of institutional, structural, individual, and cultural sexism. Sexism refers to the unjustified negative behavior against either a woman or a man and is particularly used to represent discrimination against women and girls. The multifaceted nature of sexism makes solving issues of gender inequality extremely difficult. In a 1970 study on the processes and structures of professions in the United States, Cynthia F. Epstein, a leading sociologist and researcher on gender inequality argues that women’s participation in the formal sector is limited due to the male-dominated nature of most fields. She argues that “institutionalized channels of recruitments and advancement” are not available to women in the way they are to men (Epstein, C. F., 1970, p. 965). Although her study examines systems in the 1970s when gender equality was a fairly new idea, we still see signs of institutionalized sexism today. According to the World Economic Forum, the United States ranks 45th out of 144 countries in gender parity and has an overall score of 0.722, and a score of 0.162 in political representation, where 0.00 = imparity and 1.00 = parity (“The Global Gender Gap Report” 2016). These data represent the institutional gender inequality on a national level.

Scholars often attribute gender inequality in the workplace and the gender pay gap to six distinct reasons including (1) work structure – such as inflexible working hours –, (2) women’s inability to negotiate their salaries both when they start a new job and when advancing their careers within an organization, (3) the lack of corporate sponsorship women receive, (4) the lack of women in C-suite (CEO, COO, CFO, etc.) and executive roles, making it harder for other women to rise up within a company, (5) the penalties associated with being a mother and (6) unconscious gender biases, all of which fall into one or more categories within sexism. The stagnant gender norms (despite the shifting gender roles) coupled with the aforementioned theories has left us with a pay gap that refuses to close. In a sociological framework, gender norms are what society considers either male or female behaviors, which by extension form gender roles, which are the specific roles men and women are expected to assume in society (West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H., 1987).

As stated earlier, gender roles are changing, while gender norms have remained stagnant for generations. For example, while today, it is expected for women to pursue higher education, advance professionally and become financially independent (when 50 years ago this was seen as a man’s responsibility), hence the shifting gender roles. However, gender norms have not changed; women are still expected to take on most childcare and household responsibilities (Sayer, L. C., 2005).

Parental Leave Policies Around the World

The United States is the only developed country in the world that does not have a mandatory paid parental leave policy. In the absence of such policies, traditional gender roles (where women are the primary “caregivers” and men are the “providers”) and the lower earnings of mothers due to the motherhood penalty (I will explore this more in depth later on) encourages women to cut back on paid employments and take on more child care responsibilities (relative to men) (Ray, C. Gornick & Schmitt, 2009). However, as researchers have shown, these policies do not necessarily lead to gender equality because childcare continues to disproportionately fall on women, essentially giving working women two full-time jobs (Aisenbrey et al., 2009; Albrecht et al., 1999), or a “second shift” (Hochschild, A., & Machung, A., 2012).

In the United Kingdom, parents who have been working for at least one year can take up to 280 days off for every child they have, and receive 90% of their pay, Germany provides 98 days of paid maternity leave at 100% pay, and Saudi Arabia provides 70 days of paid maternity and paternity leave at 50% pay (Downs & Wagner, 2013). Although the United States lags significantly behind other countries in providing appropriate time off to care for a newborn, providing mandatory or optional time off after a birth or adoption may not result in gender equality, or the earnings gap to close. According to researchers in the United States, Sweden and the Netherlands, any length of time mothers take off from work after childbirth (whether it be paid for and mandated by law or not) results in a career punishment (Aisenbrey et al., 2009).

In the United States, where there is no parental leave policy, mothers who take a short period of time off to care for their child experience some form of career consequences, and mothers who take a long period of time off move down in their careers and completely reduce their changes of upward mobility (Aisenbrey et al., 2009). In Germany, where law mandates a 98 day paid period for mothers, taking the full time off is shown to destabilize a mothers’ career (Aisenbrey et al., 2009). And in Sweden, where 480 days of paid time off is mandated, 90 of the days are allocated to the father (Gender Equality in Sweden [APA], n.d.) and 80% of their normal pay is given, women experience a negative effect on their careers when they take time off from work. Hence, even in Sweden where a lengthy legal parental leave is provided, if women want to advance their careers, they must return to paid work as soon as they can; “the longer women stay outside the labor market, the higher the depreciation of their human capital and consequently the lower the wage upon return to the labor market” (Aisenbrey et al., 2009, p. 3).

Family friendly policies aim to reduce gender inequality, but actually appear to do the opposite because both parents are not using them equally (Aisenbrey et al., 2009; Albrecht et al., 1999). Mainly women utilize gender-neutral family leave policies, while men take little or no time off from work to care for their children. In Sweden, for example, fathers took only 25% of the total parental leave in 2014 (Gender Equality in Sweden [APA], n.d.). This uneven distribution of childcare leads to gender inequality in paid and unpaid work. Thus, the solution to the gender wage gap does not simply lie in parental leave policies; rather, we must address the deeply imbedded institutional, structural, individual, and cultural sexism in order for us to reevaluate the distribution of labor.

In the following section I review literature on the gender wage gap in order to further understand the various explanations and theories for why the gap continues to persist. I analyze concepts including unconscious bias, negotiation differentials, corporate sponsorship, and the motherhood penalty. In order to shed light on the complex nature of the wage gap, my investigation is rooted in the analysis of gender wage gap theories from various disciplines including business, sociology and gender and women’s studies. By employing an interdisciplinary investigation of the wage gap, I aim to illustrate the dynamic nature of the issue, and help establish a framework for my own research and findings.

Existing Theories for the Gender Wage Gap

Unconscious Gender Bias

Unconscious bias, or implicit bias, refers to the attitudes and stereotypes that influence our understanding of the world and our everyday actions and decisions. These biases are automatic and completely unconscious. Unconscious biases often lead to discrimination, and greatly affect women both in academic and workplace environments (Moss-Racusin et al., 2012). For example, studies have proven that when identical female and male candidates are being assessed, male applicants are seen as significantly more competent than the identical female candidate (Moss-Racusin et al., 2012; Van Vianen et al., 1992; Good et al., 2010). Unconscious gender biases come into play in various situations i.e. when a woman becomes a mother, and results in gender inequalities and by extension wage penalties that contribute to the wage gap.

Unconscious gender biases are often coupled with gender stereotypes, creating a highly gendered climate whereby men and women are raised differently, and given a different set of expectations. For example in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math), the largest growing sectors, in 2009, women earned only 18% of all computer science degrees in the United States, and made up less than 25% of the workers in technology and engineering fields (Fisk, 2011). These data are often attributed to women’s lack of interest in these fields, however, Shelley Correll, a leading sociologist at Stanford University, argues that gender stereotypes and implicit biases may push women away from certain fields, and affects their performance, confidence, and how they are evaluated by others (Correll et al., 2014). Correll et al. argues that beliefs about gender create gender-differentiated double standards for men and women. Her study on the constraining effects of cultural understandings of gender on the career aspirations of men and women finds that when controlling for actual ability, because of these gender biases, women and men assess their own abilities differently, and thus form different career paths and aspirations. This study proves that women are not entering STEM because they are not interested or qualified; rather, they choose different career trajectories because of gender stereotypes and biases, which discourage women from pursuing these fields.

Unconscious biases can work in conjunction with other factors that contribute to wage inequality, such as how women are perceived when negotiating, establishing corporate mentorship and sponsorship, and when becoming a mother, and thus must be discussed and understood within the context of each of these issues. In the subsequent section of this literature review, unconscious gender bias is analyzed in relation to other factors contributing to the pay gap.

Negotiation Differentials

The gender wage gap is often attributed to salary negotiation differences between men and women that stem from the varying socialized behavioral norms and expectations, internalized sexism, and, as previously mentioned, unconscious gender biases. Socialized gender norms are seen as the “prototypes of essential expression” for either masculinity or femininity (West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H., 1987, p. 6), which establishes where we stand in society, how we relate to others, and how others relate to us. These socialized norms produce a dual effect that results in an immediate wage gap between men and women, regardless of skill level or experience. Scholars argue that these socialized norms lead to two distinct outcomes: (1) women are socialized to be kind, accommodating and less competitive and thus less likely than their male colleagues to negotiate in the first place, and (2) because society expects women to be kind, accommodating and less competitive, if they do negotiate, they are penalized for being “unfeminine” and as a result, risk jeopardizing their relationship with their managers, which can result in lower pay (Craver, C. B., 2002). Consequently, women are in a double bind.

When women and men negotiate, stereotypical beliefs and implicit biases about gender influence their interactions (Craver, C. B., 2002), resulting in an unequal propensity to negotiate, and by extension, unequal pay. Both women and men assume men to be more competitive, manipulative and win-lose negotiators, while women and men expect women to be more accommodating, win-win negotiators and less competitive (Craver, C. B., 2002; Bowles, H. R. 2013). These implicit biases cause managers to judge what men and women say and do differently, and for women, these biases work against them (Bennett et al., 2016; Blau et al., 2016). Women are socialized to feel “unfeminine” if they negotiate because they are perceived to be pushy or overbearing, making them less likely to negotiate in the first place. However, when women reject these socialized expectations and negotiate their salary, promotion, or benefits, they are more likely to elicit negative responses compared to their male colleagues (Blau et al., 2016). In a study on the social cost of negotiating, Bowles et al. (2005) found that male evaluators penalized female candidates for negotiating more than the male candidates, proving that even if we control for negotiation skills, educational level, and human capital, because of deep-rooted gender stereotypes, and implicit biases, women are unconsciously penalized and disadvantaged for negotiating.

Understanding negotiation differentials is important when discussing wage inequality, but we must be aware that controlling for these differentials does not solve the issue at hand. Even if we do control for these differentials – implicit biases, propensity to negotiate, and negotiation styles – women still do not advance to higher paying positions as frequently as their male colleagues, and still experience a wage gap. The gender pay inequality is a multi-faceted problem that is caused and influenced by varying levels of sexism and therefore cannot be attributed to a single reason.

Corporate Sponsorship

Sponsorship in corporate America is critical for career advancement and personal growth and development. Mentors and sponsors provide important coaching tools, advice and networks essential to younger employees trying to make their way up the corporate ladder. Mentees act as protégés and are trained and coached to stretch into a specific role, position or assignment for which their mentor or sponsor is recommending them for (Foust-Cummings et al., 2011). Sponsorship is particularly important for women because of the severe pipeline issue within the corporate structure. A corporate pipeline refers to the reduction of female employees within a firm, from entry-level roles, to senior executives. While entry-level positions have reached parity in many companies, the number of women at each level of the corporate ladder diminishes dramatically. For example, at PwC, a professional services firm, women make up 51% of the graduate intake, 47% of the global leadership teams, but only 18% of global partners (Women at PwC, 2017). This gradation seen at PwC is just one example of the pipeline issue within many companies, and corporate sponsorship is often used to mitigate this issue. However, unlike most men in corporate roles, women are less likely to have a mentor, and fail to cultivate the right kind of sponsorship (Hewlett et al., 2010).

According to Catalyst[1] research on women and men in the pipeline, when women’s mentors are highly placed within the organization, women are just as likely as men to get promoted. Thus, despite being equally qualified and competent as their male colleagues, women are not being propelled forward in their careers – and thus may experience a wage gap – because of a lack of the right type of corporate sponsorship. Furthermore, women may not be seeking sponsorship at all because the arrangement often involves spending one-on-one time with an older, married male, which can easily be perceived as an affair (again, relating to unconscious biases) (Hewlett et al., 2010). And lastly, cronyism (Epstein, C. F., 1970) and the existing stark difference in the number of men versus women in corporate leadership positions results in significantly fewer sponsorship or mentorship relationship opportunities for young female employees.

As research shows, corporate sponsorship is an effective tool used by both women, and men (although at seemingly different rates) to advance professionally. However, solving the disparity between the number of sponsored female and male employees does not address the other factors contributing to the gender wage gap, or other forms of gender discrimination. Even if a woman receives proper corporate sponsorship and advances professionally as a result (at equal rates to her male colleagues), if she decides to become a mother, she will experience significant career and wage penalties because of institutionalized sexism and gender biases.

The Motherhood Penalty

The motherhood penalty is a term coined by sociologists who argue that relative to women who do not have children, working mothers face systematic disadvantages in pay, perceived competence, and benefits (Correll et al., 2007). In the United States working mothers face discrimination in hiring and promotion and suffer a wage penalty of approximately five percent per child (Katz, 2012). Moreover, for women under the age of 35, a larger pay gap exists between mothers and non-mothers than the pay gap between men and women (Correll et al., 2007), thus working mothers make up most of the gender pay gap.

In a study on the motherhood penalty, Correll et al. (2007) provide causal evidence proving that mothers experience discrimination in hiring, and by extension, other disadvantages in the workplace and in pay. They test the hypothesis that the motherhood penalty exists because cultural views of the “ideal worker” are antithetical to what American culture views as a “good mother”. An “ideal worker” is characterized as an individual who is committed to their work, and does not have any external distractions that could potentially get in the way of doing their job. An example of this would be dropping everything at a moments notice to take over a project, working late hours, and even coming into the office during the weekend (Correll et al., 2007).

Their study shows that when the qualifications and background experiences of fake applicants were held constant, but had varying parental status, employers unconsciously discriminated against mothers when making decisions about hiring, promotion, and salary assessments, but not fathers (Correll et al., 2007). Employers judged mothers as significantly less competent and committed than their non-mother counterparts (Correll et al., 2007) and by extension, discriminated against them when making hiring and salary decisions. In contrast, fathers were actually advantaged over childless men and were viewed as more committed to paid work and offered higher salaries (Correll et al., 2007; Hodges et al., 2010; Budig, M. J. 2014). When characteristics associated with motherhood are used to describe a worker, they experience negative biases stronger than those produced solely by gender alone (Cecilia et al., 2004). Because motherhood is seen as a status characteristic, it will implicitly lower people’s expectations for a working mother’s competence, aptness for authoritative positions, and raise the standards forcing women to work harder than their colleagues to prove her ability in the workplace (Ridgeway, C. L., & Correll, S. J., 2004).

The motherhood penalty is often attributed to women valuing family more than work and employment, and thus receiving lower pay. In a study on the relationship between endorsement of family and power, anticipated work commitment and expected peak pay, Lips et al. (2009) confirmed that men expect higher peak salaries and value power more and family less than women. However, for both men and women valuing power was a predictor of higher expected peak salary, and valuing family was a predictor of lower anticipated work commitment. For women, reduced work commitment meant that they had a lower anticipated peak pay, and for men, valuing family meant that they had higher expectations for peak pay. Thus, between men and women, expectations around work and family matters are perceived quite differently. For men, even if they valued family matters, their expectations for peak pay were still high, despite the belief that valuing family was related to lower work commitment (the study also found that men and women differ in their anticipated peak career salaries with men expecting to make, on average, $20,500 a year more than what women expect to make). Women on the other hand associated lower work commitment with lower anticipated peak pay.

As studies show, the motherhood penalty greatly affects the gender wage gap due to the deep-rooted cultural beliefs of what it means to be a good worker and a good mother. Cultural norms and ideologies about gender lead to unconscious biases against mothers, framing them as less committed to work, less available, and distracted, and thus experience discrimination in hiring, promotion, and pay. Although Correll et al.’s (2007) research confirms the theory that employed mothers experience a per child wage penalty, and that mothers experience discrimination during the hiring process, their findings cannot attribute motherhood as the sole reason for the wage penalty. There are many other institutional, personal, and cultural factors that have left us with a pay gap that refuses to close.

Research Methods

Through survey data and interviews, I attempt to identify discrepancies between men and women in understanding and assuming childcare responsibilities in order to recognize inequalities at home (in unpaid labor) that may translate into inequalities in paid labor in the formal sector. Furthermore, I aim to compare those who speculate about having kids to those who have kids in order to determine if the gendered division of labor often seen in families with children is the most efficient, or if it is an assumption forced onto women and men by society. Moreover, I aim to further understand the various challenges working mothers experience to help shed light on the injustices women face. My data are based on the surveys and interviews of individuals with and without children, resulting in 445 surveys and 10 interviews. The combination of qualitative and quantitative data aim to complement one another, supporting empirical survey data with lived experiences and stories.

Survey Data

My survey was informed by Professor Carol Kehr Tittle’s study from her book Careers and Family: Sex Roles and Adolescent Life Plans (1981), which aims to understand the varying expectations around careers and family between young men and women. Her study shows discrepancies between young men and women in understanding how having children will affect their careers, but no gendered differences in career aspirations. My study builds upon many of the questions from Tittles’ research, with added questions that aim to understand opinions on maternity and paternity leave, thoughts on career advancement after having a child, and career development goals. I also developed and distributed a second survey for individuals who already have children, which aims to understand how having a child affected their careers, and how the responsibilities associated with childcare were distributed between partners. By comparing the two groups– individuals with children, and individuals without– I aim to observe trends, differences and themes. Thus, for my analysis, I controlled for parental status and gender, and did not control for age. In a few analyses, I also controlled for whether the male or female respondents want children in the future or not. This was to discard irrelevant answers related to having children.

I recruited study participants through online tools and social media platforms – Facebook, email, text, online community pages and forums – and by asking my community to distribute the survey to their own networks. My sample included 222 individuals without children, and 223 individuals with children. Though my respondents primarily female (277 women, 165 men in total), I made an overt effort to capture male respondents. A majority of study participants without children were between the ages of 18 and 24, while most participants with children were between 45 and 54 years old.

The survey was titled Career Development and Family Planning Survey to avoid gendered connotations that may otherwise deter potential male participants. I distributed the survey for 18 days, between the months of February and March. The survey was divided into two separate sets of questions – one set was for individuals with children, and the other was for individuals without children – in order to identify potential discrepancies between the two groups. I included important demographic information – such as socio-economic status, race and education- to identify and discuss potential intersections. Survey and demographic questions are listed in Appendix A, B and C.

Most of the survey response options were pre set, so participants for the most part did not have the option to give free responses. The purpose of this method was to easily identify potential trends in a purely quantitative manner. A few questions asked participants to explain their binary– either “yes” or “no”– responses so that I could incorporate important perspectives into the final analysis. For example, one question asked if participants want to go back to work after having a child. Following the question was a free response section asking them to elaborate on why they do or do not want to return to work. The quantitative survey data were analyzed using an online statistical analysis software[2]. I used a standard z-score calculation for two population proportions, since I was comparing responses between male and female participants and did not have an equal sample size for each cohort. The qualitative free-response survey answers were organized and analyzed based on similarity of the sentiments. For example, if several answers were describing similar ideas, they were grouped together to help identify recurring themes.

Interview Data

In order to supplement the survey data, I conducted a total of 10 interviews. I interviewed five men and five women, six were parents and four were not. The sample size is particularly small because I did not want to look for trends or common themes; rather, I wanted to listen to interviewees tell their stories about their careers and having children, in order to give life to the survey data. I left the questions from the interview fairly open-ended, mainly using the opportunity I had to listen and take notes. Important quotes from the interviews have been included throughout the following findings section. These quotes help illuminate important findings from the quantitative survey data.

Description of Findings

My sample demographic predominately includes highly educated individuals from a high socioeconomic status. Nearly 50% of the respondents’ yearly household income before taxes is $100,000 or above, and 75.6% of the respondents have either earned, or are currently pursuing a Bachelors degree or higher, or some sort of professional or associate degree. Most survey respondents are from the Bay Area, emphasizing predominantly liberal political and social beliefs. For my research analysis, I successfully collected 445 survey responses, 277 women, 165 men, and three gender non-binary individuals. Of the 277 women, 158 were mothers and 119 did not have children, and of the 165 men, 62 were fathers and 103 did not have children. Because my sample included very few individuals who identified as gender non-binary, I did not include their responses in my analysis.

My findings are broken into three parts:

(1) Maternity and Paternity Leave; where I discuss men and women’s opinions around parental leave and childcare resources, and compare their opinions to what occurs in reality i.e. comparing their opinions to what the parent participants actually did when they had children

(2) Career Advancement; where I analyze the differences between men and women in how having children affects their careers, and

(3) Career Goals; where I look at men and women’s opinions around career development and professional growth. In addition, throughout the discussion of my findings, I highlight important interview and survey quotes that aim to supplement the quantitative findings with qualitative stories, thoughts, and experiences.

Before I begin analyzing the data, it must be noted that from the sample of individuals who do not have children (this includes 222 total individuals who identify as either a man or woman), 75.7% of the childless men indicated that they want to have children in the future, while only 58.5% of childless women reported wanting children in the future. Moreover, 16% of women do not want children at all, while only 12.6% of men say they do not want children. Thus, the data show that significantly more men than women want children in the future, contrasting common discourse that women are more interested in family matters, homecare and childcare (Parker-Pope, 2012).

This discrepancy between men and women in wanting children may exist because women are aware of the disadvantages they will face if they have children. As Correll et al. (2007) show in their study on the motherhood penalty, when the qualifications and background experiences are held constant between men and women, employers discriminated against mothers, but not fathers (Correll et al., 2007) highlighting the disadvantages women face, but not men, when having kids. I will bring this particular result into discussion with later findings throughout the following subsections.

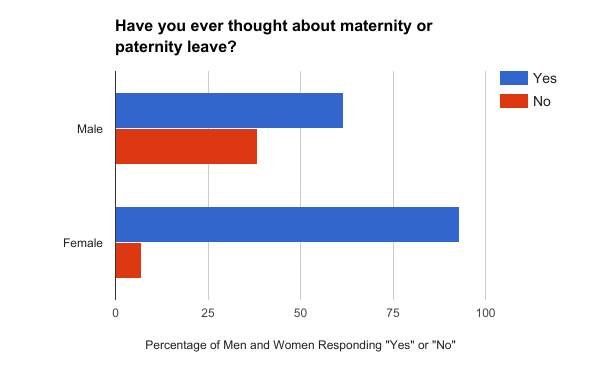

Maternity and Paternity Leave

Of the 222 respondents without children, significant distinctions between men and women in thinking about maternity and paternity leave exists, supporting the claim that both men and women know that the burdens of having a child fall differently on them. Although men are more likely than women to want kids in the future, as mentioned before, they are less likely than women to think about maternity or paternity leave. For this analysis, I only included responses from those who want children in the future. Of this cohort there were a total of 70 female and 78 male respondents. The data show 93% of the female participants marked having thought about parental leave, while only 61.2% of men say the same, as shown in figure 1 below.

Figure 1- Figure 1 shows the number of childless individuals who have or have not ever thought about maternity or paternity leave. Survey respondents were asked to mark either “yes” or “no” to this question. For the purposes of this analysis, only childless respondents who indicated that they want children in the future were included, resulting in 148 total participants (78 male and 78 female).

This finding complements trends of the percentage of fathers who actually take advantage of paternity leave opportunities. For example, as mentioned before, in Sweden where a robust family leave policy is mandated by law, and a significant portion of the family leave time is specifically designated to men, fathers take advantage of a significantly smaller portion of the total parental leave time than mothers (Gender Equality in Sweden [APA], n.d.). Moreover, as shown in a study from the Center for Work and Family at Boston College, when fathers worked for a company that offered 6 weeks of paid paternity leave, only 7% of men took advantage of the full time (Harrington et al., 2014).

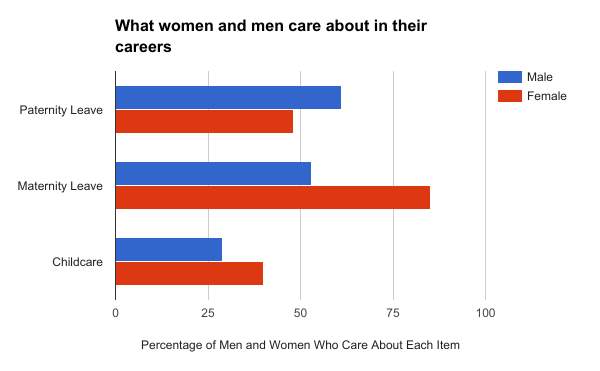

To further understand if study participants care about having a parental leave policy (provided by their employers) or childcare resources (such as an on site daycare), childless individuals were asked to mark various items they care about in their current or future careers. Respondents were not limited to a specific number of responses, so participants were able to check as many or as few as they liked. This was to gain a true understanding of what childless individuals want in their current or future careers without limiting them to a certain number of responses. The selectable items ranged from family planning and childcare resources to professional and personal development opportunities (for a list of all the questions, please refer to Appendix A). For this specific analysis, again, I chose to only include responses from men and women who indicated that they want children in the future. The data have been divided into two separate charts and subsections, divided between figures 2.1 and 2.2. Items related to family planning and childcare resources are shown below in figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1- Figure 2.1 shows the percent of childless individuals who have indicated caring about having paternity leave, maternity leave, or childcare resources in their current or future careers. For the purposes of this analysis, only childless respondents who indicated that they want children in the future were included, resulting in 148 total participants (78 male and 78 female).

As figure 2.1 illustrates, from the sample of individuals, the largest discrepancy exists between men and women in item Maternity Leave (“I want to work for a company that provides paid maternity leave”). Here we can see that significantly more women selected this option, indicating that working for a company that provides paid maternity leave is important, mainly for women. Of the total of 70 female participants who want children in the future, 85% marked wanting to work for a company that provides paid maternity leave. Of the 78 male respondents, 53% marked this same category.

For item Paternity Leave (“I want to work for a company that provides paid paternity leave”), although more men selected this option than women (61% men and 48% women), this finding was statistically insignificant at the 5% significance level. In addition, item Childcare (“I want to work for a company that provides free childcare services”) was also statistically insignificant at the 5% significance level (29% men and 40% women). Thus, from my sample of childless individuals, maternity leave is the only item where we see a significant gendered division.

This finding complements the Pew Research Center study on the American publics’ opinion on men and women taking time off from work following a birth or adoption of a child. The study shows that 15% of American adults say men should not be able to take paternity leave at all (either paid or unpaid) while only 3% believe women should not take maternity leave (Horowitz, 2017). Thus, the finding from the Pew Research Center corroborates the significantly higher percentage of participants who selected maternity leave as something important in their current or future careers. The data suggests that both women and men believe in dividing responsibilities in a gendered manner. I did not expect to see so few women from my sample select paternity leave as something important to them. I hypothesized that women would care about paternity leave at almost equal rates as maternity leave because of the significant challenges that are associated with having a child. I also hypothesized that because women are aware of the unequal division of labor, they would be more likely to prefer both maternity and paternity leave options. I will bring this result back into discussion in the section Career Advancement.

The higher percentage of women who selected maternity leave and not paternity leave does not necessarily suggest that both men and women prefer the gendered division of labor, but perhaps something assumed because of institutionalized sexism and gendered norms. In a 2017 study by the Council on Contemporary Families, young Americans were asked if they agreed with the statement “It is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family”. 74% and 52% of women and men, respectively, disagreed with this statement (Pepin & Cotter, 2017). Hence, almost 50% of men believe that men should be the financial achiever, and women should be the primary caregivers, while only 26% of women believe in such a gendered division. Thus, although significantly more women in my study care about maternity leave than paternity leave, these women may not necessarily agree with or want such a strict gendered division of labor –as shown in the study from the Council on Contemporary Families– but instead are complicit to such a division due to external forces of sexism (Epstein, C. F., 1970). These findings support the notion that women and men believe the effects of having kids will fall differently on them. Although significantly more men want children in the future than women, men are not proportionately thinking about the repercussions of having children, as shown in the number of men who have ever thought about parental leave, or care about having a paternity leave policy provided by their employers. In contrast, women want children in the future at significantly lower rates, but think about parental leave at significantly higher rates.

In order to compare childless respondents’ views about maternity and paternity leave to individuals with children, I asked mothers and fathers in my sample to indicate how much time they took off from work when they had their first child. From my sample of parent respondents, significantly more women than men took time off from work when their first child was born, and as a result, my data show that the mother respondents’ careers were affected (I will discuss the effects in the section Career Advancement). From my survey sample, 93.6% of women took time off from work or were not working when they had their first child, while all men from my survey sample were working when they had their first child, and 55.6% of men say they took time off from work when their first child was born. Thus, 44.4% of men went back to work immediately after their child was born.

I expected to see such a result as research shows that most housework and childcare continues to fall on women (Hochschild, A., & Machung, A., 2012) and that men take advantage of parental leave policies at significantly lower rates than women (Harrington et al., 2014). It must be noted that because women are the ones who give birth and actually experience pregnancy, it may seem obvious that they take time off from work at significantly higher rates than men. However, regardless of this reality, these findings still suggest an unequal division of labor. Physically, mothers are able to return to work just a few weeks after giving birth (the speed of a woman’s return is influenced by factors including family structure, education level, and birth history) but the most important factor is whether or not the new mom had been working prior to giving birth (Han et al., 2008). This suggests that although women take significantly more time off after childbirth, they do in fact want to go back to work, but may not be able to because their partners are not present to take on more childcare responsibilities (I will return to this argument in the section Career Goals).

To further illustrate the unequal division of labor, and external forces of institutionalized sexism, one interviewee describes why he was not able to take advantage of the full paternity leave provided to him, even though he wanted to. He currently works for a company with 8 weeks of paid paternity leave and 12 weeks of maternity leave. Although he was given 8 weeks of paid time off, he explains that he was only really able to take 2 weeks; “most men do not take advantage of the full paternity leave because of fear of getting paid less, our job bonuses are discretionary, and because of stigma”. This excerpt helps illustrate the external forces that may push women and men into certain roles, and demonstrates why men may not have the true opportunity to take on more childcare responsibilities, which by extension, places it on women.

Career Advancement

When asked “Do you think it will be harder to advance in your career if you have a child?” 52.8% of childless women in my sample marked “yes” in response to this question, while only 25.3% of childless men marked “yes”. The 27.5% difference between men and women in regards to this question demonstrates the differential effect of having children. Significantly more women believe that having a child will make it harder to advance their careers, demonstrating the imbalance in assuming childcare responsibilities. This finding complements the 2013 study by Pew Research Center where among parents with some work experience, mothers with children under the age of 18 were three times as likely as fathers to say that having a child made it harder to advance their career. The study found that while 51% of women agreed with this sentiment, only 16% of men agreed (Parker, 2015). In addition, this finding complements existing research on the repercussions of taking time off from work to have a child. As Aisenbrey et al. (2009) show in their study on the effects of parental leave policies in the United States, Germany, and Sweden, mothers who take a short period of time off to care for their child experience career consequences, despite the number of paid days off provided by the government. Thus the 27.5% difference between men and women in believing it will be harder to advance their careers if they have children is expected and warranted.

This discrepancy was also touched on in several interviews, but one interview in particular clearly illustrates the external effects that jeopardize women’s careers. The following excerpt is from a mother of two young children who was forced to quit her job after having a baby. She worked in banking and finance when she had her first child and explains why she had no choice but to quit shortly after coming back from maternity leave: “Banking is a male dominated field. When I would leave my desk to pump, my manager would get upset because I wasn’t at my desk, and I was a high performing employee! I decided to quit my job after I realized that I was waking up my daughter after work to breastfeed her, and when I got home at 10 ‘o’clock at night when I got back from entertaining clients”. Here the interviewee describes how she was forced into a position where she had to completely pause her career for her baby because her employer did not provide proper care for her as a new mother. She stated later on that she never wants to return to her previous employer because of how poorly she was treated. Pausing her career now will have serious repercussions on career advancement later on (Aisenbrey et al., 2009; Correll et al., 2007) and by losing a high performing employee, the company experienced a significant sunk cost (Boushey et al., 2012).

To further illustrate the childless participant’s opinions on the effects of children on career advancement, parent participants were asked to indicate how their careers developed after having children. When asked “What happened in your career within five years of having your first child?” the data show that mother respondents’ careers were impacted much more heavily than the male respondents. The survey data show that while 3.5% of women went from full-time to part-time and 6.3% of women stepped down to a less demanding role, no fathers from my sample experienced such career changes. Other important differences include the number of women versus men who quit their job within five years of having a child. While 16.1% of women say they quit their jobs, only 5.6% of men say they did the same. Additionally, only 12.6% of women were promoted within five years, while 25.9% of men reported to have been promoted within five years of having their first child, supporting Correll et al., 2007; Hodges et al., 2010 and Budig, M. J.’s 2014 studies proving that fatherhood is rewarded in paid work, while motherhood is penalized (Correll et al., 2007). Furthermore, the discrepancies between men and women in career advancement within five years of having a child confirms the views of the childless respondents on how having a child will affect their careers. Moreover, these findings may help explain why significantly fewer women than men in my sample want children in the future.

I was expecting to see differences between childless men and women’s responses to their thoughts on career advancement after having a child, however, these findings coupled with the results from Maternity and Paternity Leave displays an interesting result. As the data shows, significantly more women believe having a child will affect their career advancement. However the question remains as to why significantly fewer women care about paternity leave in their current or future careers. I expected to see significantly more women select paternity leave (which is why I allowed respondents to select as many options as they wanted), however seeing that women selected maternity leave at significantly higher rates than paternity leave suggest that women tend to internalize childcare responsibilities more than men.

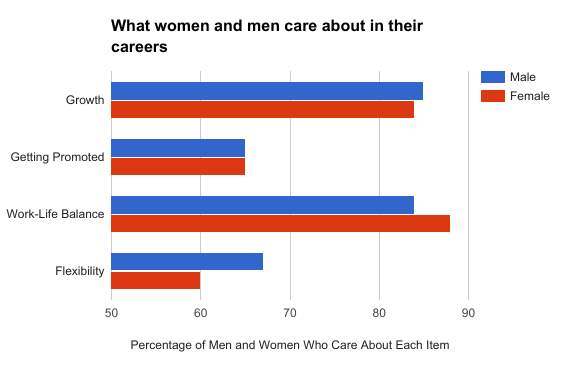

Career Goals

While there are distinct variations between the male and female responses to questions related to the effects of having children, no such variation exists in relation to career goals and wanting to return to work after having a child. When childless survey respondents were asked to mark items they cared most about in their current or future careers, we see no gendered division in items related to career growth, promotion opportunities, and flexibility. The results are pictured in figure 2.2.

In item Growth (“I want to work for a company that has many opportunities for growth”) 84% and 85% of women and men, respectively, selected this option, showing us that both men and women care about growing professionally. Thus, my data show that there is no statistical evidence that suggests that either men or women care more or less about opportunities for growth.

Figure 2.2- Figure 2.2 shows the percent of childless individuals who have indicated caring about personal growth, getting promoted, work-life balance in their current or future careers. For the purposes of this analysis, only childless respondents who indicated that they want children in the future were included, resulting in 148 total participants (78 male and 78 female).

Similarly, in item Getting Promoted (“I care about getting promoted and making my way to the top of the company”) 65% of men and women in my sample selected this option, showing that both men and women, equally, care about advancing professionally. This finding complements research on career importance by gender of men and women between the ages of 18 and 34 from the Pew Research Center. The study shows that in 1997, 58% and 56% of young men and women, respectively, believe that being successful in a high-paying career or profession is “one of the most important things” or “very important” in their lives. While in 2010/2011, 59% and 66% of young men and women, respectively, agreed with the same sentiments (Patten, E., & Parker, K., 2012).

Moreover, my survey results contrast 1970s research findings indicating that females are inherently less motivated and less interested in advancing professionally (Horner, M. S. 1972). These studies show the clear reversal of traditional gender roles around work and careers. The subsequent items –work life balance, and flexibility– also show statistically insignificant variations between the male and female respondents, highlighting the lack of a gendered division in these categories. Thus, while women experience a greater pull from home and work roles than men (Farmer, H. S. 1987) my data suggest that their career aspirations are not altered as a result.

Furthermore, my data show that 93.9% and 95.6% of women and men, respectively, plan to go back to work after having a child, further demonstrating shifting gender roles and changed expectations around women and work. Today, men are no longer seen as the primary breadwinners, and women are just as likely as men to want to get back to work after having a child, despite the clear professional disadvantages women experience when having kids (Correll et. al., 2007).

To examine reasons for why survey participants want to return (or not return) to work after having a child, I listed a type-in sub-section where participants had the opportunity to freely express their opinions. Analyzing the text, I found two distinct trends that differentiated the female responses from the male responses. Many of the female responses expressed a sense of urgency in wanting to go back to work, such as by wanting to set an example for their children, or by maintaining financial autonomy. For example, an 18-24 year old female noted “I can’t see myself as a stay at home parent. I need to be working and equally contributing to the family finances. I don’t want to be dependent on my spouse’s income”.

Similarly, another 18-24 year old female states “I don’t want to lose my self autonomy the way I watched my mother give up hers by quitting her job to raise kids”.

And finally, a 25-34 year old explains “I need to set a good example for my kids, one in which I show them how strong their mom is”.

In contrast, the male responses express an implicit assumption around going back to work after having a child. Their reasons for going back to work did not express urgency or desire to set an example for their children, rather, their responses expressed assumption about their role as the man in the relationship: “as the male in the partnership, a pregnancy will have no physical effect on me and will allow me to go back to work. Once past infancy I’m sure my partner and I will work out a schedule which would allow me to work full time” (18-24 year old male).

The three females’ responses illustrate a sense of responsibility they feel in contributing financially to their families, the control they seek to maintain after having children, and the desire to set an example for their children proving to them that women can be mothers and maintain a career. The male’s response illustrates a slightly different reaction to this same question. His response actually includes his partners’ involvement, where he is assuming that his partner will be there for him so that he is ensured the opportunity to go back to work. This response in particular further emphasizes the idea that men and women assume childcare responsibilities differently. Similar to how significantly more women thought about maternity and paternity leave, and significantly more women also believed that having a child will affect their career advancement opportunities, the statement from this male respondent illustrates the assumption that as a man, he will go back to work after having a child, no matter what.

Interpretation of Results and Conclusions

My findings show significant gender disparities in views related to maternity and paternity leave, childcare, and the effects of having a child on career advancement. The data however show no such gender disparity in ideas related to career goals, professional growth and development, and wanting to return to work after having a child. Thus, from my sample, women and men care about advancing professionally at equal rates, but at the same time, both women and men assume childcare responsibilities to be predominantly a women’s job. The findings from this study reinforce existing research on societal opinions on the division of labor, the shifting gender roles, and the motherhood penalty. The discrepancies shown in both samples (from individuals with children, and individuals without) show that unpaid labor and responsibilities associated with childcare are not only still highly gendered, but also expected, by both women and men, to be divided in this way. These findings suggest forces of institutional, structural, individual, and cultural sexism that affect how both women and men view and make sense of the division of labor. Cultural expectations about gender roles force women to take on a “second shift”, which as studies have suggested, may be a contributing to the wage gap.

As discussed before, my research and findings do not suggest that women and men must both do equal amounts of the same type of work in order for us to reach gender equality. I argue, instead that if a woman wants to take on most of the childcare responsibilities, she should be free to make that choice. And, if a woman wants to both have a child and advance her career, she should have the same rights and opportunities as a man to do so. This may be achieved by changing cultural norms around household and childcare labor, such as de-stigmatizing childcare for men so that they can take on more responsibilities without feeling societal pressures, and by implementing practices within corporate America that promote equal pay and gender equality.

Implications and Next Steps

In seeking to analyze the dynamic nature of the gender wage gap, this paper has argued that women and men perceive the division of labor differently –women tend to internalize childcare responsibilities, while men tend to assume responsibilities in the formal work sector– which results in inequalities in paid work for women. The data show that both women and men expect a gendered division of labor that puts most of the unpaid labor on women, which by extension, makes it harder for women to advance professionally. Despite these findings, survey data suggest that both women and men want to advance professionally at equal rates. However, because of institutionalized sexism (as shown in the stigma men feel around taking paternity leave, and the lack of parental leave policies) gender norms –and thus a gendered division of labor– is supported and encouraged by our current political and social systems (Epstein, C. F., 1970).

In order for us to achieve gender parity, we need to make changes on a national level. However, to begin this process, companies can make changes to end wage and workplace inequalities. Gap Inc. is an example of a Fortune 500 company that pays female and male employees equally and has equal representation of men and women at various levels of leadership and managerial positions. Kellie McElhaney, a professor at Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, outlines a few practices that contribute to Gap’s success in achieving true equality, which can be implemented by other companies as well:

- Create a company culture that fosters the growth and development of all employees, regardless of race, gender or sexual orientation (McElhaney, K., & Smith, G., 2016). In addition, create a culture that de-stigmatizes parental leave and encourage both mothers and fathers to take time off if they can.

- Analyze pay data often, and use this information to make internal changes to support and promote equal pay (McElhaney, K., & Smith, G., 2016).

- Develop a formal mentorship and sponsorship program that eliminates the need for side networking. If new employees are paired with senior employees through a pre-set system, biases and cronyism is mitigated.

- Provide family-friendly policies that support both men and women when they have a child (McElhaney, K., & Smith, G., 2016).

These methods have contributed to Gap’s success in achieving gender pay parity and a high representation of women in various levels of the organization (McElhaney, K., & Smith, G., 2016). Other companies may implement these approaches as well to work towards wage parity and equality within their organizations.

Limitations and Future Research

Although this research project was carefully constructed and carried out, there are a few limitations of the study that should be addressed in future research. Due to the small scale of the survey study, and how the survey was distributed (via my own social media platforms), I was not able to capture a diverse demographic. Most survey respondents were from very similar socioeconomic and educational backgrounds, and thus, I was not able to discuss the issue of the gender wage gap in regard to varying intersections. For future studies, intersections such as race, class, gender identity, sexual orientation and educational background should all be considered in order to gain a holistic understanding of wage inequality. In addition, although I hoped to include fairly even numbers of male and female respondents, I had a particularly difficult time collecting survey data from men. Due to time constraints I was not able to spend more time targeting my survey distribution efforts to men alone. Moreover, because the survey was distributed via social media platforms within my network, I may have been unable to capture a larger male demographic. And finally, future research may need to control for age in a similar analysis in order to identify potential trends within specific age groups.

This study poses many questions for further investigation and research. Given the multifaceted nature of the wage gap, future research must be cognizant of cultural differences that may affect perceptions of the division of labor. In some cultures, gender is the determining factor for what roles and responsibilities one has, and may not be easily altered. Future researchers may want to explore the division of labor in same-sex couples. How do these couples divide household and childcare work? Do these couples gravitate towards normative gender roles (see West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H., 1987) based on the degree of their masculine and feminine qualities i.e. the partner with feminine qualities may take on childcare responsibilities, and the partner with masculine qualities may take on most of the financial duties? Other areas of study include analyzing male and female perspectives on the division of labor using a longitudinal analysis, the role of family members who help the parents with household and childcare work (and if their presence affects female labor force participation rate and career advancement trajectories), and the interaction between political party associations and beliefs on the division of labor. The gender pay gap is a multifaceted issue that must be addressed on a national level by our politicians, on a social level by businesses, and on an individual level by being cognizant of normative gender norms and unconscious gender biases. In order for us to fully close the wage gap, we need to make fundamental cultural changes to help foster inclusion, exercise equality, and eliminate all forms of sexism.

Appendices

Appendix A: Survey Questions for Childless Participants

| Q: Do you want to have kids in the future? | A:

☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ Maybe |

| Q: How old were you when you realized you wanted to have kids? | A:

☐ 5-10 ☐ 11-15 ☐ 16-20 ☐ 21-25 ☐ 26-30 ☐ 31-35 ☐ 36-40 ☐ 41-45 ☐ 46 or older ☐ No idea ☐ I don’t want kids |

| Q: If you eventually want a child, what is preventing you from having one right now? | A: ___________________________________ |

| Q: Have you ever thought about maternity leave or paternity leave? | A:

☐ Yes ☐ No |

| Q: Do you plan on going back to work after having a child? | A:

☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ Maybe ☐ I don’t want a child/not applicable |

| Q: Why or why not? | A: ___________________________________ |

| Q: Do you think it will be harder to advance in your career if you have a child? | A:

☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ Maybe ☐ I don’t want a child/not applicable |

| Q: Please select all items you care about in your career or future career: | A:

☐ I care about having a flexible schedule. I would like to set my own hours ☐ I want to work for a company that provides free childcare services ☐ I want to work for a company that provides paid maternity leave ☐ I want to work for a company that provides paid paternity leave ☐ I care about getting promoted and making my way to the top of the company ☐ I want to work for a company that provides a good work-life balance ☐ I want to work for a company that has opportunities for growth |

Appendix B: Survey Questions for Parent Participants

| Q: How many children do you have? | A:

☐ 1 ☐ 2 ☐ 3 ☐ 4 or more |

| Q: Do you plan on having more children in the future? | A:

☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ Maybe |

| Q: How old were you when you had your first child? | A:

☐ 15-20 ☐ 21-25 ☐ 26-30 ☐ 31-35 ☐ 36-40 ☐ 41-45 ☐ 46 or above |

| Q: When your first child was born, were you… | A:

☐ Working full-time? ☐ Working part-time? ☐ Not working? ☐ In school? Other: ________________________________ |

| Q: Did you take time off from work when you had your first child? | A:

☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ I wasn’t working when I had my first child |

| Q: If so, how much time did you take off? | A:

☐ Less than 1 week ☐ About a week to a month ☐ 1-2 months ☐ About 3 months ☐ More than 3 months ☐ I never went back to work ☐ I wasn’t working, so didn’t need to take time off |

| Q: What happened in your career within five years of having your first child? | A:

☐ I was promoted ☐ I took on more responsibilities at work ☐ I went back to the same position ☐ I stepped down to a less demanding role ☐ I went from full-time to part-time ☐ I changed employers ☐ I quit my job completely ☐ Nothing changed in my career |

| Q: Where were you in your career when you had your first child? | A:

☐ Still in school ☐ Still in school and working part-time ☐ Entry-level ☐ Mid-level ☐ Senior-level ☐ Self-employed ☐ Unemployed and looking for work ☐ Unemployed and not looking for work ☐ Other: ______________________________ |

Appendix C: Demographic Information Included in Both Surveys

| Q: What id your gender identity? | A:

☐ Female ☐ Male ☐ Gender non-binary ☐ Prefer not to say ☐ Other: ______________________________ |

| Q: How old are you? | A:

☐ Under 12 years old ☐ 12-17 years old ☐ 18-24 years old ☐ 25-34 years old ☐ 35-44 years old ☐ 45-54 years old ☐ 55-64 years old ☐ 65-74 years old ☐ 75 years or older |

| Q: Please specify your ethnicity: | A:

☐ White ☐ Hispanic or Latino ☐ Black or African American ☐ Native American or American Indian ☐ Asian/Pacific Islander ☐ Middle Eastern ☐ Prefer not to say |

| Q: What is the highest degree or level of school you have completed? If currently enrolled, please indicate highest degree received | A:

☐ No schooling completed ☐ Some high school, no diploma ☐ High school graduate, diploma or equivalent ☐ Some college credit, no degree ☐ Associate degree ☐ Bachelor’s degree ☐ Master’s degree ☐ Professional degree ☐ Doctorate degree ☐ Other: ______________________________ |

| Q: What is your marital status? | A:

☐ Single, never married ☐ Married or domestic partnership ☐ Widowed ☐ Divorced ☐ Separated |

| Q: Employment status: | A: I am currently…

☐ Employed for wages ☐ Self-employed ☐ Out of work and looking for work ☐ Out of work but not currently looking ☐ A stay-at-home parent ☐ A student ☐ Military ☐ Retired ☐ Unable to work |

| Q: What is your total household income before taxes during the past 12 months? (If you are a student, please specify you family’s household income) | A:

☐ Less than $25,000 ☐ $25,000 to $34,999 ☐ $35,000 to $49,999 ☐ $50,000 to $74,999 ☐ $75,000 to $99,999 ☐ $100,000 to $149,999 ☐ $150,000 to $199,999 ☐ $200,000 or more |

References

Aisenbrey, S., Evertsson, M., & Grunow, D. (2009). Is There a Career Penalty for Mothers’ Time Out? A Comparison of Germany, Sweden and the United States. Social Forces, 88(2), 573–605.

Albrecht, J. W., Edin, P. A., Sundström, M., & Vroman, S. B. (1999). Career interruptions and subsequent earnings: A reexamination using Swedish data. Journal of human Resources, 294-311.

America’s Women and the Wage Gap (Rep.). (2009). Washington DC: National Partnership for Women & Families.

Bennett, J., Wariner, S., & Campbell, H. F. (2016). Feminist fight club: an office survival manual (for a sexist workplace). New York: Harper Wave, an imprint of HarperCollins .

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2016). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations (No. w21913). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Blau, F., & Kahn, L. (2000). Gender Differences in Pay. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 75-99. doi:10.3386/w7732

Boushey, H., & Glynn, S. J. (2012). There are significant business costs to replacing employees. Center for American Progress, 16.

Bowles, H. R. (2013). Psychological perspectives on gender in negotiation. The Sage handbook of gender and psychology, 465-483.

Bowles, H. R., Babcock, L., & McGinn, K. L. (2005). Constraints and triggers: situational mechanics of gender in negotiation. Journal of personality and social psychology 951.

Budig, M. J. (2014). The fatherhood bonus & the motherhood penalty: Parenthood and the gender gap in pay. Washington, DC: Third Way.

Budig, M. J., & Hodges, M. J. (2014). Statistical models and empirical evidence for differences in the motherhood penalty across the earnings distribution. American Sociological Review, 79(2), 358-364.

Connolly, B. G., & Abrahams, B. G. (2014, October 27). Great Leaders Who Make the Mix Work. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from https://hbr.org/2013/09/great-leaders-who-make-the-mix-work

Correll, S. J., Benard, S., & Paik, I. (2007). Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? 1. American journal of sociology, 112(5), 1297-1338.

Correll, S. J., Kelly, E. L., O’Connor, L. T., & Williams, J. C. (2014). Redesigning, redefining work. Work and Occupations, 41(1), 3-17.

Craver, C. B. (2002). Gender and negotiation performance. Sociological Practice: A Journal of Clinical and Applied Sociology, 4(3), 183-193.

Day, J. C., & Downs, B. (2007). Examining the Gender Earnings Gap: Occupational Differences and the Life Course (Rep.). U.S. Census Bureau.

Downs, T., & Wagner, S. (2014, December 15). Parental leave laws in the U.S. and abroad: Evolving international standards (Part 1). Retrieved April 30, 2017, from http://www.insidecounsel.com/2014/12/15/parental-leave-laws-in-the-us-and-abroad-evolving

Epstein, C. F. (1970). Encountering the male establishment: Sex-status limits on women’s careers in the professions. American Journal of Sociology, 75(6), 965-982.

Farmer, H. S. (1987). A multivariate model for explaining gender differences in career and achievement motivation. Educational Researcher, 16(2), 5-9.

Fisk , S. (2011). Negative Math Stereotypes = Too Few Women How Gendered Beliefs Funnel Women Away from Science and Engineering (and What Can Be Done about It) (Vol. 1, pp. 5-6, Rep.). The Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research.

Foust-Cummings, H., Dinolfo, S., & Kohler, J. (2011). Sponsoring women to success. New York, NY: Catalyst.

Gender equality in Sweden | The official site of Sweden. (2017, January 09). Retrieved April 30, 2017, from https://sweden.se/society/gender-equality-in-sweden/

Good, J. J., & Rudman, L. A. (2010). When female applicants meet sexist interviewers: The costs of being a target of benevolent sexism. Sex Roles, 62(7-8), 481-493.

Han, W. J., Ruhm, C. J., Waldfogel, J., & Washbrook, E. (2008). The timing of mothers’ employment after childbirth. Monthly labor review/US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 131(6), 15.

Harrington, B., Van Deusen, F., Sabatini Fraone, J., & Eddy, S. (2014). The New Dad: Take Your Leave: Perspectives on Paternity Leave from Fathers, Leading Organizations, and Global Policies. Boston, Mass: Boston College Center for Work & Family.

Hewlett, S. A., Peraino, K., Sherbin, L., & Sumberg, K. (2010). The sponsor effect: Breaking through the last glass ceiling. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review.

Hochschild, A., & Machung, A. (2012). The second shift: Working families and the revolution at home. Penguin.

Hodges, M. J., & Budig, M. J. (2010). Who gets the daddy bonus? Organizational hegemonic masculinity and the impact of fatherhood on earnings. Gender & Society, 24(6), 717-745.

Horner, M. S. (1972). Toward an understanding of achievement‐related conflicts in women. Journal of Social issues, 28(2), 157-175.

Horowitz, J. M. H. a. (2017, March 27). About one-in-seven Americans don’t think men should be able to take any paternity leave. Retrieved April 30, 2017, from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/03/27/about-one-in-seven-americans-dont-think-men-should-be-able-to-take-any-paternity-leave/

Joanna Pepin and David Cotter: Trending Towards Traditionalism? Changes in Youths’ Gender Ideology. (2017, March 31). Retrieved April 30, 2017, from https://contemporaryfamilies.org/2-pepin-cotter-traditionalism/

Kricheli-Katz, T. (2012). Choice, Discrimination, and the Motherhood Penalty. Law & Society Review, 46(3), 557–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2012.00506.x

Lips, H., & Lawson, K. (2009). Work values, gender, and expectations about work commitment and pay: Laying the groundwork for the “motherhood penalty”?. Sex Roles, 61(9-10), 667-676.

McElhaney, K. A., & Mobasseri, S. (2012). Women create a sustainable future. UC Berkeley Haas School of Business, October.

McElhaney, K., & Smith, G. (2016). Eliminating the Pay Gap: An Exploration of Gender Equality, Equal Pay, and A Company that Is Leading the Way (Rep.). UC Berkeley.

Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J., & Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(41), 16474-16479.

Noland, M., Moran, T., & Kotschwar, B. R. (2016). Is gender diversity profitable? Evidence from a global survey.

P. (n.d.). Gender Diversity International Women’s Day. Retrieved April 30, 2017, from http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/about/diversity/women-at-pwc/internationalwomensday.html

Parker-Pope, T. (2012, March 22). Do Women Like Child Care More Than Men? Retrieved April 30, 2017, from https://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/22/do-women-like-child-care-more-than-men/

Parker, K,. & Livingston, G. (2016, June 16). 6 facts about American fathers. Retrieved April 27, 2017, from http://www.pewresearch.ord/fact-tank/2016/06/16/fathers-day-facts/

Parker, K. (2015, March 10). Despite progress, women still bear heavier load than men in balancing work and family. Retrieved April 30, 2017, from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/03/10/women-still-bear-heavier-load-than-men-balancing-work-family/

Patten, E., & Parker, K. (2012, April 19). A Gender Reversal On Career Aspirations. Retrieved April 30, 2017, from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/04/19/a-gender-reversal-on-career-aspirations

Ray, R., Gornick, J. C., & Schmitt, J. (2008). Parental leave policies in 21 countries. Assessing generosity and gender equality.

Ridgeway, C. L., & Correll, S. J. (2004). Motherhood as a status characteristic. Journal of Social Issues, 60(4), 683-700.

Sayer, L. C. (2005). Gender, time and inequality: Trends in women’s and men’s paid work, unpaid work and free time. Social forces, 84(1), 285-303.

State Data. (n.d.). Retrieved April 4, 2017, from https://statusofwomendata.org/explore-the-data/state-data/united-states/#employment-earnings

The Global Gender Gap Report 2016 (Rep.). (n.d.). World Economic Forum. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

The Simple Truth about the Gender Pay Gap (Spring 2017). (n.d.). Retrieved April 15, 2017, from http://www.aauw.org/research/the-simple-truth-about-the-gender-pay-gap/

Tittle, C. K. (1981). Careers and family; sex roles and adolescent life plans.

Van Vianen, N. E., & Willemsen, T. M. (1992). The Employment Interview: The Role of Sex Stereotypes in the Evaluation of Male and Female Job Applicants in the Netherlands1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22(6), 471-491.

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing Gender. Gender and Society, 1(2), 125–151.

[1] Catalyst is a nonprofit organization with a mission to accelerate progress for women through workplace inclusion. They provide extensive research available to the public and help companies become more diverse and inclusive.

[2] Z Score Calculator for 2 Population Proportions. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2017, from http://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/ztest/Default2.aspx

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Equality"

Equality regards individuals having equal rights and status including access to the same goods and services giving them the same opportunities in life regardless of their heritage or beliefs.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: