Service Quality and Measurement of Customer Satisfaction in Hotel

Info: 8569 words (34 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Tagged: Consumer DecisionsHospitality

An individual report that critically evaluates the current organisational practice for the delivery of service quality and the measurement of customer satisfaction.

Table of Contents

1.Introduction……………………………………………………3

2.The Setting…………………………………………………….3

2.1 Inspiration…………………………………………………..4

2.2 Insight……………………………………………………..5

2.3 Ideation…………………………………………………….6

2.4 Initiative……………………………………………………8

2.5 Implementation……………………………………………….9

2.6 Invigilation………………………………………………….10

2.7 Investigation…………………………………………………13

3. Reflection……………………………………………………14

4. Conclusion……………………………………………………15

5. Refrences……………………………………………………18

List of Figures

Figure 1: The 7-I Process………………………………………………………………………….4

Figure 2: Guest Feedback System Developed at Taj Resorts, Hotels, and Palaces……………..…7

Figure 3: Complaint Management Tracking System at Taj Holiday Village Goa…………………8

Figure 4: Guest Meeting Tracking Report, Taj Holiday Village Goa……………………………12

Figure 5: Pictorial Method of Capturing Housekeeping Inconsistencies…………………………14

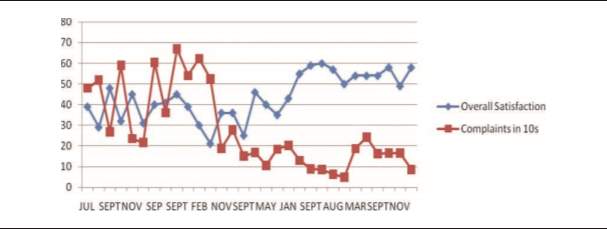

Figure 6: Monthly Guest Satisfaction Scores Compared to Complaints per Month…………….15

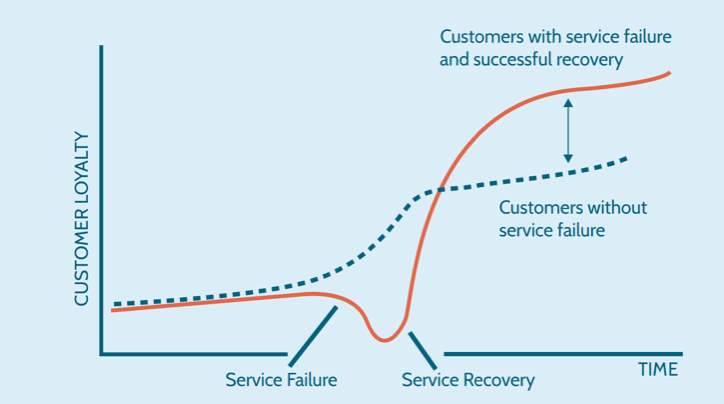

Figure 7: Service Recovery Paradox………………………………….…………………………16

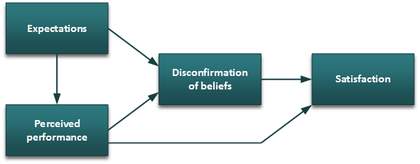

Figure 8: Expectation and Confirmation Model………………………………………………….16

Service Innovation: Applying the 7-I Model to Improve Brand Positioning at the Taj Holiday Village Goa, India

1. Introduction

The modification of the Taj Holiday Village Goa from a three-star to five-star property can be originate as a seven-step innovation management process, the 7-I model. The process resulted in the Taj becoming a market pioneer in Goa. The case discovers the process using the 7-I model: inspiration, insight, ideation, initiative, implementation, invigilation, and investigation. Concentrating on the need to upgrade service by addressing and reducing customer complaints, Taj Holiday Village Goa began with the idea of using cell phones to text guest complaints immediately to the guest services department. The plan was eventually modified to include communication of complaint reports to department managers and direct decision between high-level managers and guests to personalize the service offering. The process recognized additional issues that were resolve by establishing a new check-in time, identifying the breakfast room and kitchen, and the use of illustrated evidence to improve guestroom preparation. Because of the successful execution of these innovations, guest satisfaction scores increased, revenue per available room (RevPAR) rose to the highest in the market, and the RevPAR index increased. Revenue per available room (RevPAR) is a performance metric used in the hotel industry and is calculated by multiplying a hotel’s average daily room rate (ADR) by its occupancy rate. It may also be calculated by dividing a hotel’s total room revenue by the total number of available rooms in the period being measured (Anon., 2009). Ultimately, the cost of this innovation was insustantial in comparison with the benefit resulting in a high return on innovation. (Sengupta, 2011). This process is being reviewed with a focus on customer satisfaction.

2. The Setting

The Taj Holiday Village Goa is a 142-room, five-star property operated by Taj Hotels, Resorts, and Palaces, which is based in India and operates luxury lodging worldwide. At 15 degrees north latitude and located on the Arabian Sea, Goa enjoys a tropical climate that draws international travelers in winter and domestic travelers year-round. In addition to its coastal location, Goa features world heritage architecture resulting from 450 years of Portuguese occupation. Taj opened the Holiday Village resort in 1982 on a thirty-acre tract facing the Arabian Sea. As recently as 2005, the hotel was operating as a three-star property. The main clientele is leisure, with approximately 15% to 20% conference business. The guests are (in descending order) Indians, Western Europeans, Americans, and East Asians.All these guests give the hotel feedback using its Guest Satisfaction Tracking System (GSTS).

The Taj Goa’s management team wanted to reposition it as a five-star resort property (Guliani, Lipika Kaur, 2016) and make it a market leader in Goa. Therefore, the property was completely renovated to match the standards of international resort properties. In addition to renovating the property’s physical facilities, the hotel’s “servicescape” (Teresa Swartz, Dawn Iacobucci, 2000) also had to be redefined to match its new image. To this end, extensive training sessions and certification tests were carried out to develop the necessary skills and attitudes among the employees. Despite these efforts to revamp its service offering, however, the hotel had not yet claimed its true market position after the first year following renovation. The RevPAR index remained at 0.96, barely at par with the market, and guest satisfaction scores remained only a little above 30 percent checking the “top box” or the highest rating on the guest satisfaction survey. At this point, the hotel undertook a series of steps using the 7-I process to innovation (Sengupta, 2011).

The 7-I Process to Hospitality Innovation

The 7-I process begins with inspiration and proceeds with insight, ideation, initiative, implementation, invigilation, and investigation. Each step depends in part on what is accomplished in the preceding step, gradually modifying and refining the innovation until it achieves the initial goal. A simple model of the 7-I process is depicted in Figure 1 (Sengupta, 2011).

Figure 1: The 7-I Process (Sengupta, 2011)

Inspiration

Insight

Investigation

Implementation

2.1 Inspiration

Any major change requires inspiration, the invisible force that guides the change process. Inspired employees and management have the motivation and commitment needed to bring about transformational change (WebFinance Inc., 2017). Even though change often requires a prodigious effort on the part of everyone involved, with inspiration a team can affect, and experience change more smoothly. Inspiration, which is the spark that sets the process of innovation in motion, might be provided by a person or by an ambitious target (Ottenbacher and Gray 2004).

Inspiration involves a process of conscious discovery of the reality of a situation and then of developing a strategy to alter that reality. Targets are process-driven and generally provide more effective inspiration to employees, since all can aim for the same target. Leaders also provide inspiration by driving the change process, but their relationships with individuals will vary from case to case (Ottenbacher and Gray 2004). A common target unifies the staff more reliably. At the Taj Goa, the employees of the hotel were made aware of the hotel’s new objective to become a five-star resort for the leisure and tourist market of Goa in a way that enlisted their efforts towards this common goal. This lofty objective instilled pride equally in the employees and the management team. Everyone knew that working for a five-star property would mean providing the highest quality professional service and amenities to the hotel’s guests (Sengupta, 2011).

Most employees are also inspired when management is open and transparent about its objectives, sharing the true status of the company, because it makes them feel valued and trusted. Therefore, the general manager shared with all employees a detailed picture of the hotel’s business situation, which showed the hotel was lagging its competition in terms of average daily rate (ADR) ADR is one of the commonly used financial indicators in hotel industry used to measure how well a hotel performs compared to its competitors and itself (year over year). It is common in the hotel industry for the ADR to gradually increase year over year bringing in more revenue. However, ADR itself is not enough to measure the performance of the hotel. One should combine ADR, occupancy and RevPAR (revenue per available room) to make a sound judgment on hotel performance (Anon., 2013), revenue per available room (RevPAR), and occupancy (Ottenbacher and Gray 2004). The general manager’s efforts to create awareness of the situation, combined with the ambitious nature of the target outcome, inspired the team to undertake the innovation process whole heartedly (Sengupta, 2011).

2.2 Insight

Insight is needed to turn inspiration into results. Effective innovative cannot occur in isolation. Instead, innovation requires deep understanding of the processes that are to undergo change and of how to bring about that change (Victorino et al. 2005). The team must have a thorough insight regarding the environment in which change is to be affected and must identify the factors that promote the process. Each step in understanding the various environmental factors is a moment of insight. In a hospitality environment, innovative insight is crucial because it is not possible to run a controlled experiment to understand the effects of various forces on the change process. It is therefore through insight that the team comes to understand what might happen if a particular factor is altered in light of the objective (Sengupta, 2011).

In this case, personalizing the guest experience was the critical factor (see Victorino et al. 2005). Four Seasons has, for example, constantly differentiated itself from other hotels based on its ability to provide personalized service to its guests (Jay Kandampully, 2006). This personalized service helps Four Seasons to remain on top of the market (Talbott 2006). The Taj Goa sought insights into how to personalize its service by tailoring services and amenities to meet its guests’ high expectations. Developing this insight is an integral part of innovation, to allow development of a process to implement personalized service. Such a process should be able to provide a framework that creates knowledge for developing definitive guest experiences, which generally result in higher guest satisfaction and incremental revenue increases (see Prasad and Dev 2002).

To redesign its services, the Taj Goa sought guest feedback on its existing operations. According to a senior Taj Goa manager, “Guest feedback is the first step to know our guests. Feedback of all types complaints, compliments, and suggestions should be welcome. Complaints provide the most important insights, and we need to encourage our employees to share the complaints without fear of reprimand (Sengupta, 2011).” Taj employs a proprietary customer feedback system to collect, record, and track guest feedback in a meaningful format (see Figure 2). Employees can upload guest feedback, which can then be seen on a real-time basis by the top management of the hotel as well as that of the company (Sengupta, 2011).

This process revealed another insight into the guest feedback process. Because the guest feedback channels that hotels use vary in richness, not all channels are equally attractive to guests. Research shows, for example, that guests are disinclined to use guest-comment cards typically found in the guestroom (Susskind 2006). Direct conversations with hotel management, on the other hand, are more likely to yield useful information. This is particularly true for guest complaints, as 49 percent of guests prefer registering complaints with a manager rather than with a line-level employee or by writing on an in-room guest comment card (Susskind 2006).

2.3 Ideation

Ideation is the process through which a team striving to bring about change develops new ideas directed at solving problems (Jones 1996). An effective innovative idea must be grounded and bear directly on key factors in the change process. From a potentially limitless stock of ideas, those that are realistic and easy to understand and implement best support the innovation process. Being realistic also makes ideas easily communicable to the entire team. All stakeholder’s employees, management, and guests should become part of the idea-generating process, because an idea that is not supported by all stakeholders is unlikely to realize its full potential. Achieving buy-in from all stakeholders leads to the easy implementation and effective functioning of an idea (Jones 1996). Ideation is the creative process of generating, developing, and communicating new ideas, where an idea is understood as a basic element of thought that can be either visual, concrete, or abstract. Ideation comprises all stages of a thought cycle, from innovation (Graham and Bachmann, 2004, p. 54), to development, to actualization. As such, it is an essential part of the design process, both in education and practice (Anon., 2014). A good way to achieve buy-in is to openly discuss a promising idea with the change team and allow its members to share their concerns and suggestions for improvement. Such transparency and full participation leads to a richer understanding of the ideation process and a more effective outcome.

To foster proper recording and transmission of complaints, the general manager of the Taj Goa swept away the typical (and cumbersome) process of registering complaints in writing. Instead, the general manager’s novel idea was to encourage employees to share guest complaints using the telephone.

Calls of this type went to a centralized guest services desk in the housekeeping department. This desk was designed to collect all guest requests and complaints so that they could be brought to the management’s attention. When an employee receiving a guest complaint phoned guest services, the attendant at the desk would text a group short service message (GSSM) to the mobile phones of all heads of department and managers—instantly alerting every department about the complaint. This innovative approach made computer access unnecessary, and most guest-facing employees carry mobile phones always. Once the complaint was texted, the responsible department could contact the guest and work on appropriate service recovery. Other departments could also follow up by treating the guest with extra care throughout the rest of the stay. This not only ensures that the complaint is not repeated but enhances the guest experience in a way that compensates for the problem that provoked the complaint (Sengupta, 2011). Not every idea works as well as this one did, but each idea should be considered carefully to see whether it fits with the original inspiration and insights (Anon., 2011).

| Figure 2:

Guest Feedback System Developed at Taj Resorts, Hotels, and Palaces (Sengupta, 2011)

|

2.4 Initiative

Even with inspiration and insight, a great idea can be highly effective only if it is backed up by an initiative, the plan of action through which an innovation is implemented. Initiatives must be carefully designed service delivery methods that can transform ideas into reality. An effective initiative works as a catalyst between an idea and the implementation stages of the innovation cycle (Dev, 2012). The initiative stage is in that respect like the soft launch of a hotel. That is, an idea is soft launched and run for a certain period. During this trial period, employees and management can assess the efficacy of the idea and look for opportunities to improve it. The initiative stage ensures that the idea is ready to be implemented and does not run off the road once it has been implemented. As the wheel of innovation runs, the initiative stage touches each process in the organization. This helps to introduce new ideas into existing processes and incorporate the relevant ones permanently into the system.

When the complaint management system was soft launched at the Taj Goa, the general manager observed that many complaints were “lost” in the course of daily operations. As we have noted, the way in which a complaint is registered matters. For example, a complaint reported to guest services in the register will not be available for any type of analysis. Also, no one can know how many complaints occurred on a date or what was done to ensure proper service recovery in each case. Therefore, the team felt that the system should be slightly modified to incorporate a tracking system for complaints. A complaint would be recorded on a shared Excel spreadsheet for guest services (see Figure 3). This system ensured that all complaints would be available to everyone with access to a computer in the hotel. The general manager would review the complaints once each day to ensure that proper service recovery had been achieved. This initiative was easy to understand and implement because once the idea is created and implemented then it can be understood by the employees and the team. The process also ensured that the hotel’s senior management team learned of and could effectively track guest complaints. This process helped to ensure that most guests leaving the hotel would depart happy despite the service issues they had encountered.

Figure 3:

Complaint Management Tracking System at Taj Holiday Village Goa(Sengupta, 2011)

The new system for sharing complaints, however, raised a different challenge. The managers who were responsible for a department in which a complaint occurred felt uncomfortable. Employees could now directly communicate a complaint to guest services (and eventually the general manager) without first checking with their own department managers. Therefore, most managers and heads of departments were discouraging their employees from communicating complaints. When the general manager became aware of this situation, he again changed the process. Now, the employee reporting the complaint had to inform the appropriate departmental manager after reporting the complaint to guest services. The employee was assured that no disciplinary action would be taken for reporting a complaint.

If you work with people, sell a product, or provide a service, you likely deal with complaints, and those complaints can take many forms (L. Heather, 2016). While most companies must manage complaints of some kind, certain businesses—like healthcare institutions, municipalities, educational systems, financial services companies, restaurants, and retailers—also must consider how failing to properly handle a complaint could potentially damage their reputation or even create liability due to compromised compliance. The trick is to recognize the extent to which your business may have to deal with complaints on a regular basis and then implement complaint management early on. This is especially critical if you serve external customers and your reputation or compliance, in part, relies on making customers happy or keeping them safe. (L. Heather, 2016)

The department heads were also told that the process was being run on a test-case basis and that the number of complaints originating in their departments would not affect their performance appraisals. This effectively removed the incentive on the part of managers to hide complaints. Of course, complaints from any given department do reflect poorly on the department manager, so it took some time for the entire team to commit to open sharing of guest complaints.

2.5 Implementation

The real test of an idea takes place during the implementation process. For implementation to work, an idea must be communicated effectively to all stakeholders. Rarely do the people who develop an idea assume primary responsibility for its implementation. For example, most ideas originate with or are approved by top management and then implemented by supervisors or frontline employees. Implementation is therefore the time during which gaps in understanding between management and frontline employees are revealed. An idea that top management finds easy to understand may be incomprehensible to frontline employees. Another challenge that arises during the implementation phase is that the scale at which the idea is to be implemented broadens. An idea that seemed to work well when tested in a small focus group might yield different results when introduced into the complexities of a hotel. Thus, the real-world test of an innovation process is crucial.

The innovation process is fragile during the implementation phase, because even momentary or minor failures can be magnified. Thus, management must communicate frequently to keep concerned employees well informed about the implementation process and its outcome. This requires a certain degree of agility on the part of management, which must respond to and adjust for small glitches as quickly as possible to keep the process moving. Should a major failure occur, the buy-in effect dissipates rapidly, thus potentially killing the innovation before it has been thoroughly tested.

In the case of the Taj Goa, the general manager announced the introduction of the new role of guest services and the complaint management system at one of the monthly staff “town hall” meetings, which are official yet informal gatherings of all employees and managers. The general manager explained the rationale for the innovation and the exact process that had to be followed in operating the new complaint management system. He also met with the employees’ union separately and assured its officers that all union members understood the process and what it was trying to achieve. Those responsible for training departmental staff were first trained in the operation of the process (Ottenbacher, Shaw, and Howley 2005), and these departmental trainers in turn trained the remaining staff to ensure that the entire team was clear about the process. Training follow-up included displays of process charts in each department that clearly outlined the process to be followed for reporting complaints.

The successful implementation of the complaint process created a sarcastic and awkward outcome a noticeable increase in complaints registered in the system as compared with the same period in the previous year. Contrary to past practice, the complaint management system ensured that all complaints were reported and recorded. At the same time, these complaints were fed into the customer feedback system of the Taj Goa. This created a delicate situation, because capturing all complaints made the Taj Goa’s complaint rates seem high in comparison with those of other Taj hotels. Since this was a pilot project and was running solely at the Taj Holiday Village Goa, the hotel alone would be responsible for any company-wide spike in reported complaints. Indeed, corporate management noticed the number of complaints and queried the general manager regarding those numbers. He explained that the new awareness of guest complaints made it possible for the hotel to address those complaints effectively thereby eventually raising guest satisfaction scores. Those predictions were borne out when guest satisfaction rose almost 10 percent after the system was fully in place, the property’s RevPAR rose by 1,000 rupees (about $20), and the RevPAR index rose to 1.10 a remarkable swing from below fair share to 10 percent above fair share of the market. Despite these favorable numbers, the guest complaints increased at an even higher rate than did the guest satisfaction scores or the RevPAR index. Still, the Taj Goa could point to a successful implementation of its process and service innovation.

2.6 Invigilation

Once an innovation has been implemented, it must be invigilated, a term borrowed from examination proctoring that means monitoring. In short, one must ensure that the process is running as intended, since the long-term success of an innovation requires continual monitoring and supervision and the staff’s commitment to it. Particularly in large organizations, employees require a good deal of handholding long after an innovation has been implemented. Threats to the innovation come from a changing business environment, employee confusion, and the human tendency to modify processes that one does not enjoy or understand. Management also must maintain a reliable training regime for new employees. Careful monitoring of the innovation process helps ensure full implementation, and observation based on invigilation can result in modification of the innovation when so indicated. Thus, as the innovation changes the organizational culture, it may become clear that the innovation must be modified to achieve its goals (Sengupta, 2011).

In the case of the Taj Goa, invigilation led to a substantial modification of the complaint monitoring plan that involved switching to a proactive stance. Despite an assertive service recovery process, the guests usually did not rate the hotel as “excellent” on the guest satisfaction survey. In many instances, no matter how effectively a complaint was addressed, the guest still recalled that something “not good” occurred. The general manager’s analysis of the guest feedback statistics showed that there was a constant bias toward reporting and recording of complaints. Though it is extremely important for a hotel to acknowledge guest complaints and act on them, guests’ rating of a hotel depends crucially on guest delight. The hotel can correct a problem, but the hotel is completely forgiven only when the overall guest experience is highly positive.

As a result, the Taj Goa altered its program to include a proactive approach to determine guests’ likes and dislikes. Most upscale hotels send guests a prearrival questionnaire to learn about their personal preferences and to create a service blueprint. Research shows, however, that e-mails or other written exchanges with the guest history manager are not rich sources of communication for guests (Ottenbacher, Shaw, and Howley 2005). Most guests prefer face-to-face interaction with the senior management of a hotel. Therefore, at the Taj Goa, the guest complaint management system was modified to include meetings between guests and senior managers, both to forestall problems and to resolve issues before they became severe enough to provoke a guest complaint. If a guest had a problem, he or she could instantly find a manager to resolve the issue. While the personal contact would likely lead to an increase in the number of complaints, it would also ensure prompt responses. Managers would attend to complaints directly, thereby demonstrating to guests that their satisfaction is important to the property.

This modified idea was put into practice with regular meetings of guests and managers. Each manager was assigned a certain number of rooms and was responsible for meeting the guests occupying those rooms upon the guests’ arrival, to plan a customized experience. Since the guests were in Goa for an experience, they appreciated this gesture, and the manager could explain all of Goa’s attractions. The manager would also leave his or her contact details with the guest, so that the guest could call the manager with any suggestions, complaints, or inquiries (Sengupta, 2011). Once again, guest feedback was tracked on an Excel spreadsheet that would be updated any time a manager met with guests (see Figure 4). Among other advantages, the continual monitoring of the guest meeting process ensured that all guests would eventually meet with a manager before they left. This process helped the hotel to understand and record the individual needs of all guests, which in turn led to a marked improvement in the quality and quantity of information that was available to the hotel’s staff. Most guests now had their preferences marked out, which helped the staff honor guest preferences on return visits.

Although frontline employees, who interacted most frequently with guests, should be able to identify guests’ preferences, the general manager observed that employees had no incentive to share what they had learned. The general manager therefore created an incentive by rewarding employees for identifying a certain number of guest preferences each month. They also understood that delighted guests would leave higher tips for all. This realization led to increased reporting and recording of guest feedback. The higher information level with which the guests’ preferences were recorded further improved the quality of services for the guests.

Figure4: |

This modified idea was put into practice with regular meetings of guests and managers. Each manager was assigned a certain number of rooms and was responsible for meeting the guests occupying those rooms upon the guests’ arrival, to plan a customized experience. Since the guests were in Goa for an experience, they appreciated this gesture, and the manager could explain all of Goa’s attractions. The manager would also leave his or her contact details with the guest, so that the guest could call the manager with any suggestions, complaints, or inquiries. Once again, guest feedback was tracked on an Excel spreadsheet that would be updated any time a manager met with guests (see Figure 4). Among other advantages, the continual monitoring of the guest meeting process ensured that all guests would eventually meet with a manager before they left. This process helped the hotel to understand and record the individual needs of all guests.

2.7 Investigation

The observations from the final phase allow an investigation of the various cause-and-effect relationships that have occurred with an innovation, many of which are not apparent prior to implementation. Moreover, management must investigate any unexpected outcomes. The difficulty with designing a process is that one cannot ascertain with certainty the outcome except through invigilation after implementation. Upon investigation, it may be determined, for example, that seemingly unrelated services have affected the innovation’s outcome. Thus, an investigation requires objective and analytical thinking, as well as rigorous analysis, to identify and assess cause-and-effect relationships between various service elements. These analytical findings can then be used to fine-tune the servicescape (Teresa Swartz, Dawn Iacobucci, 2000).

In the case of the Taj Holiday Village Goa, the guest manager interaction process improved the quality of guests’ feedback dramatically. The ensuing investigation of guest dissatisfaction identified the following three causes for 80 percent of the complaints:

- room not ready on arrival,

- too long of a wait for breakfast at the restaurant, and

- inconsistent servicing of room by housekeeping.

Management then analyzed the source of each of these complaints, all of which were based on unrealized but reasonable expectations. Unready rooms stemmed from the hotel’s policy that set both check-in time and check-out time at 12:00 p.m. If a departing guest did not vacate the room until occupancy of 77 percent, the average house count was 243, as most rooms were on double occupancy. Enjoying a relaxed holiday schedule, most guests came to breakfast between 9:00 and 10:00 a.m. The mismatch of restaurant size and guest patronage now created tremendous pressure on the service staff and longer wait times for guests (Sengupta, 2011).

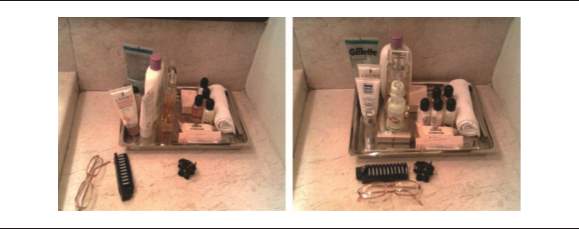

As was the case for the rooms being unready, the inconsistent service on the part of housekeeping staff was caused by the overlap of the check-in and check-out times, augmented by ineffective training.

The matter of unready rooms was easily remedied. The general manager requested corporate approval to shift the hotel’s check-in time to 2:00 p.m., while keeping the check-out time at noon. Adjusting the restaurant capacity took more work but also was easily accomplished. The breakfast preparation work was shifted to a satellite kitchen. Since breakfast is mainly a buffet, this did not lead to any larger operational problems. The kitchen space thus released was converted to additional seating space as part of a larger renovation. This increased the number of covers to 236, which could more easily accommodate the breakfast rush. On days when occupancy peaked at 100 percent, the adjoining restaurant would be opened with a separate buffet to ensure that guests enjoyed prompt service (Sengupta, 2011).

With the check-in and check-out time resolved, management could focus on training to ensure housekeeping the noon deadline, housekeeping did not have time to turn the room if it was needed for a guest arriving at noon. Since Goa is easily accessible from Mumbai (the main feeder market for domestic tourists), most guests would plan to arrive by 12:00 p.m. One would not be surprised if a guest lodged a complaint in such a case.

The wait for breakfast occurred primarily because the restaurant had only 144 covers for 142 rooms. With an average consistency. To strengthen the verbal training program, the general manager advised trainers to adopt pictorial training methods, as shown in Figure 5 (see Robson and Pullman 2006). Whenever a housekeeper checked rooms, she would photograph mistakes, correct them, and take photographs to show the proper, corrected arrangement. Comparing the pictures at departmental briefings made it easy to clarify issues with room attendants. To reinforce this learning, the hotel changed the room attendants’ pay package to include incentive pay. This incentive was paid monthly based on the percentage of excellent ratings on the guest satisfaction survey and on points scored during room checks (Sturman 2006).

Figure 5:

Pictorial Method of Capturing Housekeeping Inconsistencies(Sengupta, 2011)

Effective Innovation

Effective Innovation

These steps helped reduce complaints dramatically and improve guest satisfaction scores by 20 percentage points on average (see Figure 6). The hotel’s RevPAR increased to the highest level in the market, with the RevPAR index moving up to 1.17, or 17 percent above its fair share of the market. In doing so, the hotel became the market leader in Goa (Sengupta, 2011). Based on an analysis of guest satisfaction scores from July 2006 to December 2008 and the complaints for the corresponding periods, the correlation between the number of complaints and the corresponding overall satisfaction was good. The interaction with the guests and the personalized service accounted for the remaining part of the increase in the overall score for satisfaction.

3. Reflection

The general manager thought that it was important to carry out the 7-I process of innovation in a sequential manner, with feedback loops where appropriate. Each step of the process was informed by its predecessors. Investigation allowed the general manager to understand the efficacy of the processes. When the general manager implemented the complaint escalation process through mobile SMS, for example, it did not lead to substantial rise in the satisfaction scores. This required the general manager to return to earlier steps of inspiration and insight, which led to the focus on personalized service. This in turn led to the idea of the Guest Meeting Tracking Report. Thus, the innovation process went through the cyclical process of the 7- I process. The results were that the Taj Goa achieved an increase in GSTS scores and a reduction in complaints (Karthikeyan, 2009).

Figure 6:

Monthly Guest Satisfaction Scores Compared to Complaints per Month(Sengupta, 2011)

4. Conclusion

This case study underlines the key point that innovation in a resort hotel or any hospitality operation is a complex process involving products, people, and process. By following the seven steps of the 7-I process, a hotel property or brand can innovate in a logical manner. The process at the Taj Holiday Village Goa took two years to show results and then only after several midcourse adjustments (Sengupta, 2011).

The author has seen in this case study that implementation of a successful innovation involved the identification and correction of a series of problems, some of which could not have been anticipated in the early stages of the process. Earlier the hotel was facing many issues related to customer satisfaction but after implementation of the 7-I process there are many changes are perceived, i.e. employees are working in the hotel more effectively and efficiently, the improvement was seen in customer satisfaction, customer feedback is increased for positive parameters and customer complaints are decreased. By keeping the focus on crucial organizational parameters, the Taj Goa could ultimately validate a successful innovation. The author is explaining some theories to define the implementation, satisfaction, suggestions and approach which can be tried in the business.

Service Recovery Theory: The service recovery paradox (SRP) is a situation in which a customer thinks more highly of a company after the company has corrected a problem with their service, compared to how he or she would regard the company if non-faulty service had been provided. The main reason behind this thinking is that successful recovery of a faulty service leads to increased assurance and confidence among customers (Krishna, 2014).

For example, a traveler’s flight is cancelled. When she calls the airline, they apologies and offer her another flight of her choice on the same day, and a discount voucher against future travel. Under the service recovery paradox, the traveler is now happier with the airline, and more loyal to it, than she would have been had no problem occurred.

Understanding SRP has been an important goal for both researchers and managers, as service failure is one of the main determinants of customer switching behavior and successful recovery from these failures is seen by some as critical for customer retention (McCollough, 2000). Recovery is especially important for service providers for whom ensuring an error-free service is impossible (Fisk, 1993)

Figure 7: Service Recovery Paradox

Expectation and Confirmation Theory: Expectation confirmation theory (alternatively ECT or expectation disconfirmation theory) is a cognitive theory which seeks to explain post-purchase or post-adoption satisfaction as a function of expectations, perceived performance, and disconfirmation of beliefs (L, 1997). Although the theory originally appeared in the psychology and marketing literatures, it has since been adopted in several other scientific fields, notably including consumer research and information systems, among others (R.L, 1980).

Figure 8: Expectation and Confirmation Model

Some major key points to be considered:

- Open feedback platform for customer.

- Respond to guest feedback.

- Feedback portal must be available at every POS (Point of Sale).

- Manager must leave his/her contact details with customer during the check-in.

- Weekly feedback from employee regarding customer complaint.

- Motivational session for employees for customer satisfaction.

- Training session for employees for enhancing the customer satisfaction.

- Use an alert system for feedback with negative reviews, receives instant attention.

- Create policies and guidelines for management of online feedback.

- Share best and worst media practices with all hotels and staff members.

5. Refrences

Anon., 2009. Wikipedia. [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RevPAR [[Accessed [Accessed 19 Novemebr 2017].

Anon., 2011. Sources of Insight. [Online] Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/search?dcr=0&source=hp&ei=eRslWq7GLtHWkwWppZj4DQ&q=.+Not+every+idea+works+as+well+as+this+one+did%2C+but+each+idea+should+be+considered+carefully+to+see+whether+it+fits+with+the+original+inspiration+and+insights.&oq=.+Not+every+id [Accessed 24 November 2017].

Anon., 2014. wikipedia. [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ideation_(creative_process) [Accessed 1 december 2017].

Dev, C., 2012. Hospitality Branding. [Online] Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?isbn=0801465265[Accessed 29 Novemeber 2017].

Fisk, R. P. S. W. B. a. M. J. B., 1993. wikipedia. [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Service_recovery_paradox#cite_note-3 [Accessed 2 Decemeber 2017].

Graham and Bachmann, 2004. The Birth and Death of Ideas. In: The book Ideation. s.l: s.n.

Guliani, Lipika Kaur, 2016. Google. [Online]

Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?isbn=1466699035 [Accessed 14 November 2017].

Heather Lancaster, June 2016, https://www.issuetrak.com/what-is-complaint-management-and-why-do-you-need-it/ [Accessed 29 Novemebr 2017].

Jones, P. 1996. Managing hospitality innovation. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 37 (5): 86.

Krishna, A. D. G. a. S. S., 2014. wikipedia. [Online]

Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Service_recovery_paradox#cite_note-1 [Accessed 2 Decemeber 2017].

Karthikeyan, A. S. M. G., 2009. LQ feedback formulation for discrete-time. [Online] Available at: http://www.EDU.PL/yadda.icm.edu.pl [Accessed 28 November 2017].

Lewis, R. C. 1983. When guests complain. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 24 (2): 23-32.

McCollough, M. B. L. a. Y. M., 2000. wikipedia. [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Service_recovery_paradox#cite_note-2 [Accessed 2 December 2017].

L, O. R., 1997. wikipedia. [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expectation_confirmation_theory [Accessed 2 December 2017 ].

Ottenbacher, M. C. 2005. How to develop successful hospitality innovations. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 46 (2): 205-22.

Ottenbacher, M. C. 2007. Innovation management in hospitality industry: Different strategies for achieving success. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research 31 (4): 431-57.

Ottenbacher, M. C., and B. Gray. 2004. The new service-development process: The initial stages for hotel innovations. FIU Hospitality Review 22 (2): 59-70.

Ottenbacher, M. C., V. Shaw, and M. Howley. 2005. Impact of employee management on hospitality innovation success. FIU Hospitality and Tourism Review 23 (1): 82-95.

Prasad, K., and C. S. Dev. 2002. Model estimates of financial impact of guest satisfaction efforts. Hotel and Motel Management 217 (August): 23.

R.L, O., 1980. wikipedia. [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expectation_confirmation_theory

[Accessed 2 Decemeber 2017].

Robson, S. K. A., and M. E. Pullman. 2006. A picture is worth a thousand words: Using photo-elicitation to solicit hotel guest feedback. CHR Tools no. 7. Ithaca, NY: Center for Hospitality Research, Cornell University.

Sengupta, A., 2011. Service Innovation: Applying the 7-I Model t. Feburary, pp. 3-11.

Sturman, M. 2006. Using your pay system to improve employee performance—How you pay makes a difference. Cornell Hospitality Report 6. Ithaca, NY: Center for Hospitality Research, Cornell University.

Susskind, A. 2006. An examination of guest complaints and complaint communication channels—The medium does matter. Cornell Hospitality Report 6 (14). Ithaca, NY: Center for Hospitality Research, Cornell University.

Talbott, B. M. 2006. The power of personal service. Cornell Hospitality Industry Perspectives 1. Ithaca, NY: Center for Hospitality Research, Cornell University.

Teresa Swartz, Dawn Iacobucci, 2000. Handbook of Services Marketing and Management – Page 37. [Online]

Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?isbn=0761916121 [Accessed 14 November 13 2017].

Victorino, L., R. Verma, G. Plaschka, and C. S. Dev. 2005. Service innovation and customer choices in the hospitality industry. Managing Service Quality 15 (6): 555-76.

WebFinance Inc., 2017. Business Dictionary. [Online] Available at: http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/transformational-change.html [Accessed 19 Novemebr 2017].

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Hospitality"

Hospitality refers to the hosting and entertainment of guests or visitors. The Hospitality sector includes businesses such as hotels, B&Bs;, restaurants, cafes, bars, and other businesses relating to travel, tourism, and entertainment.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: