Relationship Between School Safety and Achievement in K-12 Education

Info: 9845 words (39 pages) Dissertation

Published: 11th Dec 2019

Tagged: EducationHealth and Safety

Introduction

The Office of Safe and Healthy Students (OSHS), with its Readiness and Emergency Management for Schools (REMS) Technical Assistance (TA) Center, supports schools, districts, and institutions of higher education (IHEs), with their community partners, in their emergency preparedness efforts. These include activities to address safety, security, and emergency management issues and create a comprehensive all-hazards Emergency Operations Plan (EOP).

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), signed into law in December of 2015 reauthorizes the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA), and builds upon the primary ESEA goal of providing all students with equal access to a high-quality education. Included in the new provisions to improve student outcomes, the Student Support and Academic Enrichment (SSAE) program is designed to support state education agencies (SEAs), local educational agencies (LEAs), schools and communities in their capacity to address the following three goals for all students:

- Provide access to a well-rounded education

- Establish safe and healthy school conditions

- Improve academic achievement and digital literacy through the effective use of technology (SSAE grants guidance, ESEA section 4101).

Purpose

This literature review was conducted to evaluate the relationship between school safety and achievement schoolwide, classroom-wide, and for individual students in K-12 education. This review focused on research pertaining to the three abovementioned content areas of ESEA section 4101, and activities that may be implemented under these content areas as a part of the SSAE grants.

Research Questions

The literature review was guided by the following research questions:

- What, if any, relationship exists between school safety and student achievement?

- How does the current body of research on school safety and student achievement pertain to well-rounded education, safe and healthy schools, and the effective use of technology?

Methods for Literature Search

The search for credible information and data was conducted using the PubMed, PubMed Central, Academic Search Complete/EBSCO and Business Source/EBSCO databases and the Google and Google Scholar search engines. Search results were narrowed to focus primarily on the results of research studies published in peer-reviewed journals and federal and state government resources.

Searches were conducted using combinations of the following terms: safety, school, student, security, achievement, academic outcomes, performance, school climate, trauma, trauma-informed, bullying, engagement, education, grades, intervention programs, sexual harassment, impact, substance abuse, perceived safety, victimization, violence, social-emotional learning, crime, mental health, safety measures and impacts, technology. If selected research and resources cited other research or data, this information was reviewed to ensure only primary/original research evidence was included.

School Safety and Achievement as Part of a Well-Rounded Education

Under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) legislation, ESEA section 8101(52) defines well-rounded education as:

courses, activities, and programming in subjects such as English, reading or language arts, writing, science, technology, engineering, mathematics, foreign languages, civics and government, economics, arts, history, geography, computer science, music, career and technical education, health, physical education, and any other subject, as determined by the State or local educational agency, with the purpose of providing all students access to an enriched curriculum and educational experience (U.S. Department of Education (ED), 2016).

Allowable activities as part of a well-rounded education include programs that promote constructive student engagement, problem solving and conflict resolution. This section will focus on the importance of safety and perceptions of safety for student success in an enriched educational curriculum, beginning in early learning with exploration and expanding into diverse learning across a variety of activities.

School Climate

The National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments defines school climate as “a product of a school’s attention to fostering safety; promoting a supportive academic, disciplinary, and physical environment; and encouraging and maintaining respectful, trusting, and caring relationships throughout the school community no matter the setting—from Pre-K/Elementary School to higher education” (National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments, n.d.). Climate is based on patterns of experiences of students, parents, and school personnel, and includes shared norms, values, and expectations, as well as educational practices, relationships, and the organizational environment (National School Climate Council, 2007; Glisson, 2007; Cohen & Geier, 2010). Both the quality and consistency of school climate impact the cognitive, social, and psychological development of children, and a growing body of research suggests that school climate reform offers an evidence-based strategy for improving school safety (Haynes, Emmons, & Ben-Avie, 1997; Astor, Benbenisty, & Estrada, 2009). Schools lacking supportive climates have students who are more likely to experience victimization, violence, poor attendance, and decreased academic achievement (Astor, Guerra, & Van Acker, 2010), and risk factors such as unsafe, disorganized schools and neighborhoods are predictive of academic failure (Hopson, Schiller, & Lawson, 2014; Berliner, 2010; Urban, Lewin-Bizan, & Lerner, 2009).

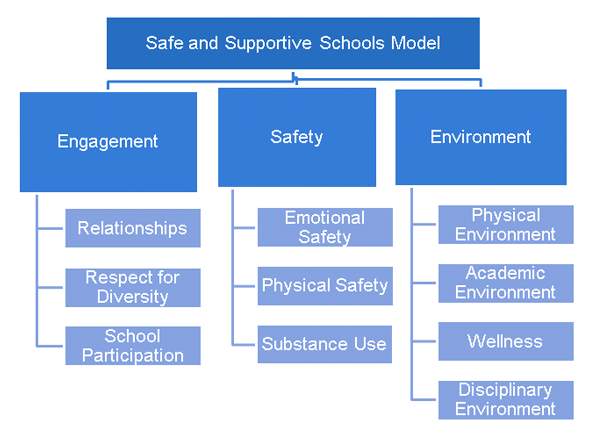

Figure 1. US Department of Education Safe and Supportive Schools Model of School Climate

Although a consensus regarding key dimensions of school climate has not been reached, most research suggests that there are four broad areas of focus: Safety, Relationships, Teaching and Learning, and the External/Institutional Environment (Center for Social and Emotional Education, 2010; National School Climate Council, 2007). The Safe and Supportive Schools Model of School Climate, above, groups individual factors contributing to school climate into three overarching topics—engagement, safety, and environment. The model identifies three key domains of school safety, including social-emotional safety, physical safety, and substance use. An examination of the Maryland Safe and Supportive Schools Climate Survey further expanded upon elements of each of the domains. Results suggested that student perceptions of physical safety at school depended heavily on opinions of whether the school was equipped to deal with conflicts; the existence of bullying and aggression, and a sense of whether or not substance abuse represents a significant problem in the school. Engagement encompassed indicators addressing teacher, student, and whole-school connectedness, as well as parental involvement, academic engagement, and the presence of a culture of equity. The domain of environment was comprised of items addressing discipline (rules and consequences), cleanliness and physical comfort, emotional support, and level of disorder. Data from over 25,000 high school students confirmed the validity of this model, and confirmed that safety is a central aspect of the school climate model, reinforcing the importance of students’ ability to feel safe in school (Bradshaw, Waasdorp, Debnam, & Johnson, 2014; Wilson D. , 2004).

Literature indicates that perceived safety at school is determined by school climate as opposed to elements such as location or levels of academic achievement (Bosworth, Ford & Hernandez, 2011), suggesting that school climate plays a pivotal role in determining feelings of safety among the school community. In fact, schools with demographically similar levels of crime and poverty can vary considerably in rates of victimization. Astor et al. (2009) examined 239 schools that did not meet predicted levels of violence based on violence in the community, and found that school climate and organization were the key variables in determining both violent and nonviolent school settings. Distinguishing characteristics included observable positive relationships between students and staff, as expected, but extended beyond personal relationships to the physical school environment itself. Schools perceived as safe were generally more attractive and well-cared for, and schools with high levels of violence/ perceived danger evidenced multiple physically neglected areas (Image 1, below).

Figure 2: Images of school grounds for atypically low violence (a) and atypically high violence (b) schools. From “School Violence and Theoretically Atypical Schools: The Principal’s Centrality in Orchestrating Safe Schools”, by R.A. Astor, R, Benbenishty, and J.N. Estrada, 2009, American Education Research Journal, 46, p.445. Copyright 2009 by American Education Research Association.

In a recent Institute of Educational Sciences (IES), National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE) study, Voight and Hanson (2017) evaluated data from 1000 California middle schools between the 2004/2005 and 2010/2011 school years. Incorporation of longitudinal data offered a unique opportunity to examine the relationship between school climate and achievement across schools at a single time point as well as over a six-year period. Results indicated that schools with higher levels of student-reported positive climate (including high levels of safety, connectedness, and positive relationships; and low levels of substance abuse, bullying, discrimination, and violence) had higher academic performance in English and Math. Additionally, changes in school climate over time were associated with changes in academic achievement within individual schools, although these differences in academic performance were smaller than the differences across schools at a single time point. These findings suggest that the relationship between climate and achievement at a single time point may not be predictive of the magnitude of academic changes that occur as climate changes over time. Of note, the design of this research study was not intended to assess a causal relationship between climate and academic performance (Voight & Hanson, 2017).

Positive school climate has a significant impact on student motivation, feelings of connectedness and engagement with school, and academic performance (Hopson, Schiller, & Lawson, 2014), and evidence suggests a positive climate can mitigate both the negative effects of self-criticism (Kuperminic, Leadbeater, & Blatt, 2001), and the negative impact of socioeconomic environment on academic achievement (Astor, Benbenisty, & Estrada, 2009). School climate has been positively correlated with student self-esteem (Hoge, Smit, & Hanson, 1990), decreased absenteeism (Gottfredson & Gottfredson, 1989; Thapa, Cohen, Guffey, & Higgins-D’Allesandro, 2013; Center for Social and Emotional Education, 2010), reduced bullying and harassment, (Kosciw & Elizabeth, 2006; Center for Social and Emotional Education, 2010) and decreased substance abuse and psychiatric problems (Kasen, Johnson, & Cohen, 1990; LaRusso, Romer, & Selman, 2008). A growing body of research indicates that positive school climate is also associated with reduced violence and aggression (Gregory, et al., 2010; Karcher, 2002; Godstein, Young, & Boyd, 2008; Brookmeyer, Fanti, & Henrich, 2006); however, this relationship appears to depend on student feelings of connectedness to their school (Wilson D. , 2004). Ultimately, school climate appears to impact student outcomes through a number of overlapping effects. Thapa et al. summarized the myriad ways in which school climate is important in their 2013 review of school climate research:

…including social, emotional, intellectual, and physical safety; positive youth development, mental health, and healthy relationships; higher graduation rates; school connectedness and engagement; academic achievement; social, emotional, and civic learning; teacher retention; and effective school reform. Furthermore, it must be understood that both the effects of school climate and the conditions that give rise to them are deeply interconnected. (p.3)

Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Health and Learning

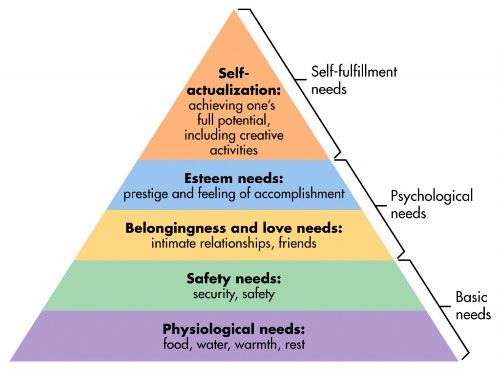

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 1943) states that basic/deficiency needs, including physiological (food, sleep, etc.) needs and safety needs must be met before an individual can attempt to fill higher-level needs such as self-esteem and the drive to evolve and achieve.

Figure 3. Maslow’s Hierarchy. From “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs”, by S. A. McLeod, 2016 (www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html)

Emotional, social, psychological, and physical safety are fundamental to the satisfaction of the deficiency needs. Student perception of school as a safe place encourages healthy learning and development (Devine & Cohen, 2007). Conversely, students who do not feel safe in school or perceive their school as dangerous experience lowered confidence, motivation, and academic performance (Jimerson & Furlong, 2006; Bosworth, Ford, & Hernandez, 2011; Goldstein & Boyd, 2008). It is likely that students who are fearful and focused on meeting basic needs for safety are unable to dedicate sufficient attention and resources to learning and academic achievement (Bosworth, Ford, & Hernandez, 2011) (Juvonen, Nishina, & Graham, 2006; Steinberg, Allensworth, & Johnson, 2011). Safe and supportive school environments encourage a greater student sense of attachment to school, and establish an ideal base for student social, emotional, and academic learning (Center for Social and Emotional Education, 2010).

Safety

Recent research indicates that perceptions of school safety and danger may actually have a greater impact on student success than actual incidents (Godstein, Young, & Boyd, 2008; Dinkes, Forrest Cataldi, & Lin-Kelly, 2007). In a purposeful sample of 12 Arizona public and charter schools, students and faculty identified three primary categories of school safety: physical characteristics and features (tangible/visible items and equipment like fences, video cameras, locked doors, and an existing emergency plan); organization and school discipline (a clearly communicated and consistently enforced system of discipline and behavior management in place, teacher awareness and intervention in disruptive behavior and fights); and school staffing (positive relationships, teamwork, administrative support, and alert, present adults). Schools included in the study were divided equally between low and high achieving schools, based on standardized achievement tests. Of note, school resource officers (SROs) were perceived as improving school safety only if the SRO was highly visible, present, and his or her role was clearly understood (Bosworth, Ford, & Hernandez, 2011).

Analysis of data from 13,068 middle school students from 43 schools in four states who completed the School Success Profile (SSP) (Bowen, Rose, & Bowen, 2005) between 2001 and 2005 revealed significant relationships between school-level perceptions of safety and student grades, and between student-level perceptions of neighborhood safety and grades. An examination of the interaction between student-perceived neighborhood support and school safety indicated that the relationship between neighborhood support and grades is only significant in schools that are perceived as safe, suggesting that neighborhood support, as a protective factor is insufficient to mitigate the effects of an unsafe school environment on academic outcomes (Hopson, Schiller, & Lawson, 2014).

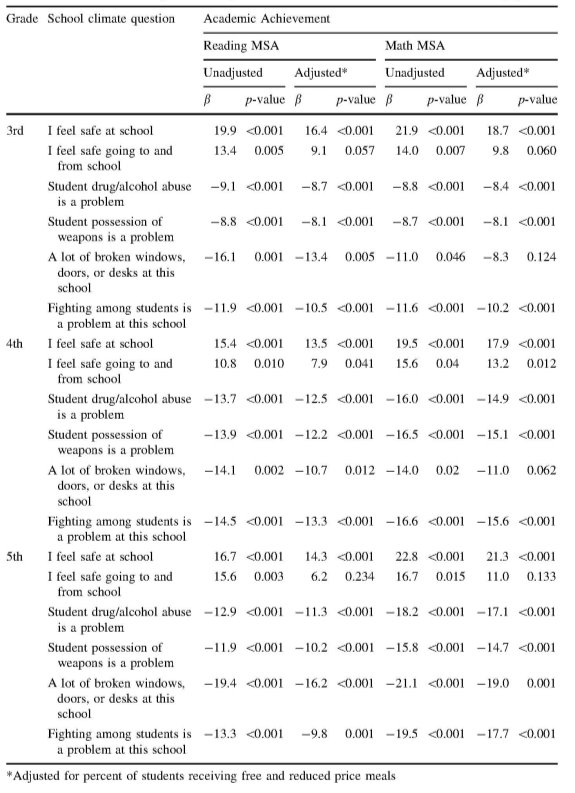

To date, most studies examining the relationship between perceptions of school safety and achievement have utilized single-time-point data, and variations across schools. Evidence from this work appears to support the assertion that there is a positive correlation between school climate and academic performance. A study of 3rd-5th grade students in 116 public elementary schools in urban Baltimore used the Baltimore City Public School System’s (BCPSS) annual School Climate Survey (SCS) and the Maryland School Assessment (MSA) to evaluate the relationship between perceptions of school and community safety (and perceived peer substance abuse), neighborhood violence and school performance. The study utilized the Neighborhood Inventory of Environmental Typology (NIfETy) observational instrument (Furr-Holden, et al., 2008) to provide an objective measure of neighborhood violence risk. The study revealed strong associations between student reported sense of safety in school and academic achievement on the reading and math MSA for each grade (Table 1) (Milam, Furr-Holden, & Leaf, 2010).

Table 1. School Climate and Academic Achievement Linear Regression Results. From “Perceived School and Neighborhood Safety, Neighborhood Violence and Achievement in Urban School Children,” by A. Milam, C. Furr-Holden, and P. Leaf, 2010, Urban Review, 42(5), p. 464. Copyright 2010 by Springer Science+Business Media, LLC.

The Research Alliance for New York City Schools also conducted an analysis of longitudinal data, comprising teacher responses to the New York City School Survey from 278 middle schools between 2007 and 2012. Using factor analysis, Kraft et al. identified four dimensions of school context:

- Leadership and professional development,

- High academic expectations for students,

- Teacher relationships and collaboration, and

- School safety and order.

School safety and order survey items addressed crime and violence, threats, bullying, discipline and order, whether adults are disrespectful, and teacher perceptions of safety. The study was designed to capture the relationship between changes in the school organizational contexts, teacher turnover, and student achievement, modeling achievement as a function of student, teacher, and school variables. Findings were consistent with those of previous studies that demonstrate larger student achievement improvements are associated with schools with higher quality climates/contexts, and revealed that climate/contextual improvements were associated with corresponding achievement gains. Specifically, of the four dimensions identified, safety was most strongly associated with academic improvement. This association was stronger in mathematical achievement than in English, with improvements in math equivalent to those resulting from an extra month and a half of math instruction. An increase of one standard deviation in the safety of a school was correlated to a 0.056 standard deviation gain in math, and a 0.032 standard deviation increase in English language arts (0.032 standard deviations and 0.013 standard deviations, respectively, when controlled for other contextual variables. Taken together, results indicate a likely causal relationship between improved school context and teacher retention, leading to increased rates of student achievement improvement on standardized tests (Kraft, Marinell, & Shen-Wei Yee, 2016).

Emotional Safety, Trauma, and Academic Functioning

Between 13% and 20% of children in the United States experience a serious emotional disturbance in a given year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Perceptions of emotional safety are an important determinant of academic achievement, as students who struggle with emotional and mental disturbance cannot perform well if their needs are not being met. Students’ academic success is supported or constrained by multiple tiers of influence (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and as a result, is necessarily interdependent with their success in other domains (Doll, Spies, & Champion, 2012). Therefore, it is plausible that academic success is related to psychological, social, and emotional well-being, and ensuring physical and psychological well-being are fundamental to student perceptions of safety. Awareness of student emotional and mental disturbances is essential, as schools are “the largest de facto provider of mental health services” (Foy & Perrin, 2010).

The topic of emotional safety becomes even more important when discussing youth exposed to long-term trauma, manifesting itself in such disturbances as anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and concentration problems, as well as difficulties with emotion regulation, social relationships, and even physical symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Cavanaugh, 2016). Further, given that the neurobiological development of children and adolescents is incomplete, trauma experienced during youth can result in impaired self-regulation, learning, memory, and social skills (Perry, 1994; van der Kolk, 2003). Since these types of disturbances can impair important elements of success in school such as study skills, reasoning, and verbal abilities, it can be said that youth exposed to trauma are at risk for poor academic performance (Overstreet & Mathews, 2011). The same risk for poor academic performance is also observed in college students experiencing posttraumatic stress disorder (Boyraz, Granda, Baker, Tidwell, & Waits, 2016).

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (2013), as many as one third to one half of individuals exposed to trauma will develop PTSD, and individuals with PTSD are 80% more likely to have depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, or substance use disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Students with pre-existing behavioral, academic, or attentional problems are at increased risk of developing PTSD following exposure to trauma (Kruczek & Salsman, 2006), and children who live with parent/caregiver neglect, mental illness, and substance abuse are at even greater risk when exposed to school trauma (Shonkoff, 2008; Walkley & Cox, 2013). Higher self-esteem, cognitive ability, problem solving and communication skills may serve as protective factors against the development of PTSD (Yule, Perrin, & Smith, 1999; Kruczek & Salsman, 2006).

Trauma may relate to individual incidents, including school shootings and natural disasters, or daily occurrences such as neglect and abuse (American Association of Children’s Residential Centers, 2014). Children who experience maltreatment typically evidence increased internalizing and externalizing behaviors, social skill impairment, and diminished school engagement (Shonk & Cicchetti, 2001). Findings regarding the influence of exposure to disaster on standardized test scores and grades are mixed. A number of studies have demonstrated declines in academic performance following a disaster (Broberg, Dyregrov, & Lilled, 2005; Ward, Shelley, Kaase, & Pane, 2008), while others have reported no evidence of a relationship (La Greca & Prinstein, 2002; Scott, Lapre, Marsee, & Weems, 2014). The inconsistency of these findings is likely due to the fact that the impact of disaster exposure is not always direct, but is mediated by emotional distress (Sims, Boasso, Burch, Naser, & Overstreet, 2015). Exposure may diminish perceptions of personal control (Weems & Overstreet, 2008), generating feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, and emotional detachment. This, in turn, can lead to disengagement with school, decreased academic performance and disrupted academic motivation (Saigh, Mroueh, Zimmerman, & Fairbank, 1995; Saigh, Mroueh, & Bremmer, 1997).

Most students experience trauma as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (Cavanaugh, 2016). According to the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than one in five adults reported three or more adverse childhood experiences, which increases the risk of poor academic achievement, high-risk behaviors, adolescent pregnancy, and substance abuse, and other social, cognitive, and emotional impairments (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Students who have experienced trauma not only are at risk of poor academic performance, but are at risk for poor behavior and feeling mistrustful in relationships with adults at school (Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative, n.d.), are 2.5 times more likely to fail a grade, are suspended or expelled more often, and score lower on standardized tests (Wolpow, Johnson, Hertel, & Kincaid, 2009). ACEs are also related to negative outcomes later in life, including obesity and early death (Cavanaugh, 2016). Exposure to violence as early as first-grade is related to deficits in children’s I.Q. and reading ability even after controlling for caregiver I.Q, socioeconomic status, and exposure to substance abuse; and subsequent trauma-related distress accounts for additional variance in reading ability (Delaney-Black, et al., 2002). Given the frequency of ACEs and their impact on student social, emotional, cognitive, and educational development, it is especially critical that educators engage in trauma-informed practices.

Trauma-informed practice encourages providers to “approach their clients’ personal, mental, and relational distress with an informed understanding of the impact trauma can have on the entire human experience” (Evans & Coccoma, 2014, p. 1). According to the National Center for Trauma-Informed Care (National Center for Trauma Informed Care (NCTIC), 2015), trauma-informed practices encompass an entire organization and its purpose, policies, and mission. A trauma-informed program or organization:

- Understands the full impact of trauma and potential paths to recovery;

- Recognizes signs and symptoms of trauma in individuals involved in the program or organization;

- Fully integrates knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and

- Actively resists and prevents re-traumatization (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2014).

Trauma-informed schools are prepared to recognize and respond to students who have been impacted from traumatic stress (Treatment and Services Adaptation Center, n.d.). The key to trauma-informed practice is establishing a safe environment (Cavanaugh, 2016). Trauma-informed educational practices accomplish this through systems such as school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports (SWPBIS) (Horner, Sugai, & Anderson, 2010), where three to five schoolwide expectations are developed, taught and reinforced across school environments. Maintaining these regardless of environment also provides critical consistency for traumatized students (Pappano, 2014). Trauma-informed schools are also culturally sensitive, linguistically informed, and considerate of diversity, offer opportunities for students to interact in empowering roles, and utilize positive reinforcement with a focus on a strengths-based approach (Cavanaugh, 2016). They emphasize compassionate teaching practices, avoiding power struggles and providing students with a sense of shared control (Crosby, 2015). These practices support self-efficacy and provide traumatized students with opportunities to showcase strengths, make choices, and explore interests, and to experience significant successes, engagement (Cavanaugh, 2016).

Social Emotional Learning

The ESEA, section 4107 (a)(3)(J) allows for the use of funds designated to support a well-rounded education for “activities in social emotional learning, including interventions that build resilience, self-control, empathy, persistence, and other social and behavioral skills” (U.S. Department of Education (ED), 2016, p. 23). In addition to SWPBIS and trauma-informed educational practices, social and emotional learning (SEL) programs teach skills that support resilience and healthy development, and foster engagement and adaptation in students.

Social and emotional competencies are key to school success and academic achievement in elementary school. These abilities, such as empathy, conflict resolution, and decision making, foster engagement, collaboration, and academic readiness. In fact, emotion knowledge in kindergarten students predicts academic achievement at age nine (Denham, Bassett, Zinsser, & Wyatt, 2014). Conversely, lack of social and emotional competencies leads to student disengagement and a lack of connectedness to the school, negatively impacting academic performance.

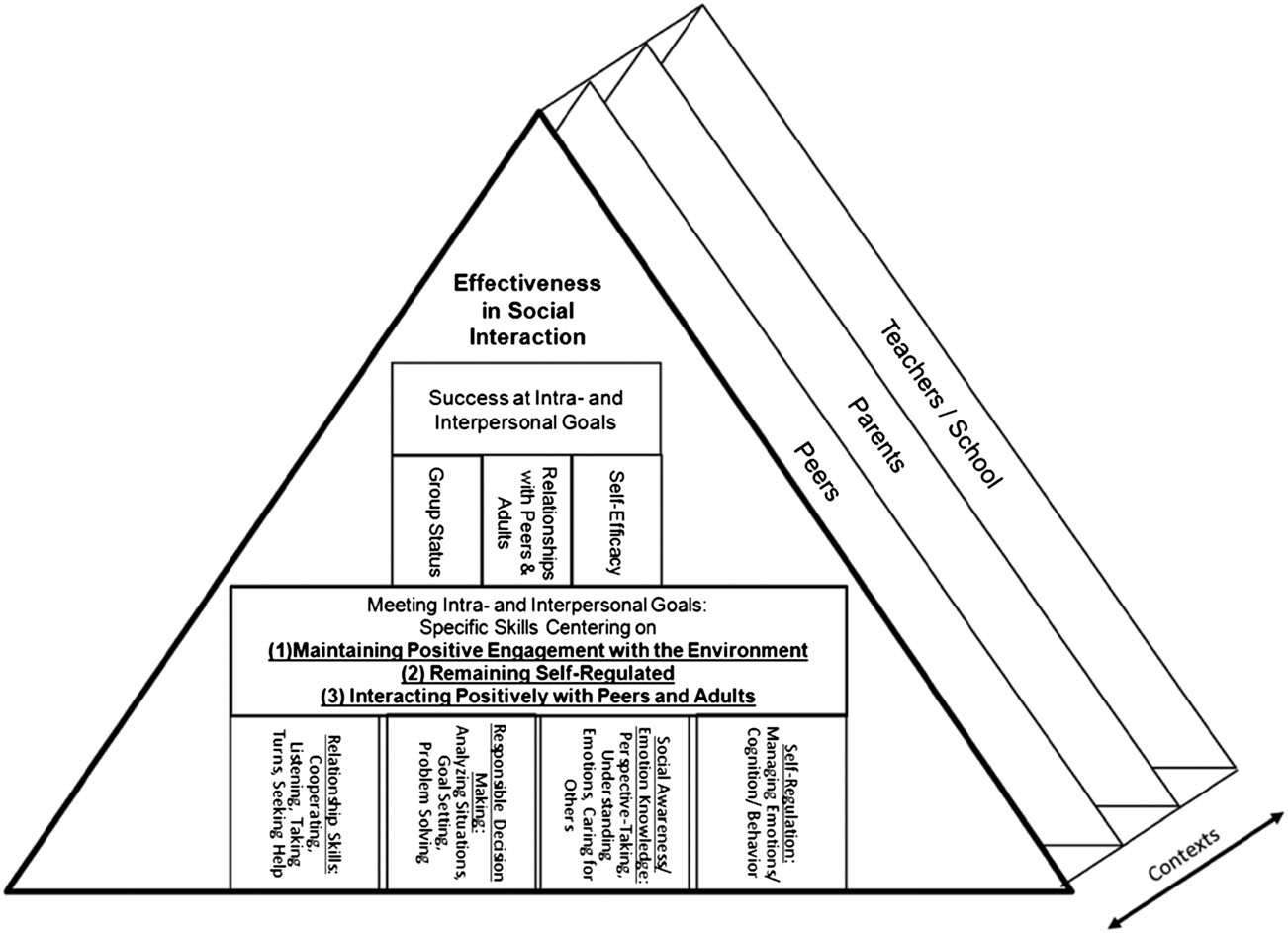

SEL interventions are evidence-based practices that support a sense of belonging, value, self-efficacy, and self-determination, enhance social and emotional development, and increase academic success (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011). Universal school-based interventions target outcomes including academic performance, aggressive and problem behaviors, mental health, and drug use with the goals of fostering self-awareness, self-regulation, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision making (Figure 4) (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, 2005). When structured, sequential, and correctly implemented, SEL programs enhance social and emotional competencies, prosocial behavior, reduce conduct problems and distress, and improve academic performance.

Figure 4. Prism Model of Social-Emotional Learning. From: “How Preschoolers’ Social-Emotional Learning Predicts Their Early School Success: Developing Theory-Promoting, Competency-Based Assessments” by S. A. Denham, H. H. Bassett, K. Zinsser, and T. M. Wyatt, 2014, Infant and Child Development, 23, p. 428. Copyright 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

In a study of over 250,000 kindergarten through high school students participating in universal -delivered to all students in a general classroom setting, rather than only delivered to specific students- (National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, n.d.) school-based SEL programming, significant improvements were seen in social and emotional skills, attitudes, behavior, with an 11 percentile-point gain in academic performance compared to controls (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011). Further, specific SEL programs like Steps to Respect (Committee for Children, 2001)have demonstrated that combined with focused rules, policies and supervision, and staff intervention training, student classroom SEL interventions result in improved school climate and reduced physical bullying (Smith & Low, 2013).

Safe and Healthy Schools and Student Achievement

The SSAE grants program is also designed to support activities that improve school conditions for student learning and success. Aspects of school safety in this category include physical safety and substance abuse, discussed further below.

Physical Safety

The physical safety of students is essential to establishing an environment that promotes learning and achievement. Physical safety may include safety from human hazards, such as bullying, harassment, and violence, or health and environmental health issues such as drug and alcohol abuse.

Bullying

Bullying, a highly influential contributor to school climate, has many documented effects on the victim and overall school community. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), 28% of U.S. students in grades 6-12 has experienced bullying (National Center for Education Statistics and Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2013). More striking, 70.6% of young people say that they have seen bullying in their schools, with 70.4% of school staff having witnessed bullying as well (Bradshaw, Sawyer, & O’Brennan, 2007). While bullying can be an issue of both emotional and physical safety, verbal and social types of bullying that include name calling, teasing, and spreading rumors or lies are much more common than physical types such as pushing or shoving, hitting or slapping, and threatening. Cyberbullying is also of increasing concern as more children gain access to social media platforms.

The literature suggests that bullying and peer victimization are related to low academic performance (Espelage, Hong, Rao, & Low, 2013). Lacey and Cornell found that a climate of bullying, specifically student perceptions of the severity of bullying and teasing was predictive of schoolwide achievement on standardized testing in Virginia (Lacey & Cornell, 2013). In an assessment of peer victimization, depression, and academic outcomes in 199 elementary school children, frequent victimization was associated with lower grade point averages and achievement test scores on both a concurrent and predictive level (Schwartz, Gorman, Nakamoto, & Toblin, 2005). Additional analyses supported the hypothesis that peer group victimization is predictive of academic challenges due to depressive symptoms.

The first study to comprehensively examine the effect of state anti-bullying laws (ABLs) on school safety and youth violence found that there is little evidence that state ABLs are effective in improving school safety, however, school districts with strong and comprehensive anti-bullying policies see a 7-13% reduction in school violence and a 8-12% reduction in school bullying (Sabia & Bass, 2017).

Harassment and Violence

Sexual harassment has been found to have detrimental effects on a greater number of health outcomes when compared to bullying in a sample of 522 middle school and high school students. These health effects are most significant among girls and sexual minorities (Gruber & Fineran, 2008). For girls, sexual harassment is associated with feeling unsafe at school (Chiodo, Wolfe, Crooks, Hughes, & Jaffe, 2009). Verbal victimization occurs more often than physical victimization, with the most upsetting incidents including homophobic language, followed by sexual commentary and rumors (Espelage, Hong, Rinehart, & Doshi, 2016). The Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network has reported that:

- approximately 85% of high school students report suffering harassment in school due to real or perceived sexual orientation,

- 64% of students report harassment due to real or perceived gender identity, and

- 31% of LGBT students report that their schools have comprehensive protection policies.

Although nearly all public schools receive Title IX funding, entitling any student to file a complaint with the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) at the U.S. Department of Education, this complaint must be filed within 180 days of the incident (GLSEN & PFLAG, n.d.). In 2009, OCR began investigating sexual violence as a separate category of sexual harassment (already monitored under Title IX). OCR, in consultation with the Justice Department, issued requirements in 2011 for K-12 schools that have received reports of sexual violence. These requirements specify that police investigation does not absolve schools from conducting reviews of whether student rights have been violated. The new regulations led to a dramatic increase in the number of sexual violence complaints received by OCR, and a struggle to keep up with the influx. An Associated Press analysis of OCR records released under a public information request found that only 1 in 10 sexual violence complaints led to school improvements, nearly half of the complaints received between 2008 and 2016 were unresolved, and of those that were resolved, most were closed (Schmall & Dunklin, 2017).

It has been suggested that bystander action on behalf of school personnel may be an important component of domestic violence, sexual violence, and sexual harassment prevention programs for teenagers; school personnel cite that they talk with teenagers about healthy relationships, intervene during acts of violence and harassment, and comfort victims after the fact (Edwards, Rodenhizer, & Eckstein, 2017). A 2016 study found that student beliefs that sexual harassment is morally wrong and harmful strongly predicts that the behavior will stop occurring (Peter, Tasker, & Horn, 2016). Further, student beliefs about school policies prohibiting sexual harassment had no bearing on whether students perpetrated sexual harassment, findings that suggest sexual harassment prevention programs in schools should focus on the moral reasoning of perpetrators as opposed to strict, no-tolerance initiatives.

Substance Abuse

Substance abuse among youth impedes school safety efforts by negatively impacting academic performance, increasing the potential for violence, and potentially creating mental health issues (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2014). Data from the National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), the only surveillance system designed to monitor a wide range of priority health risk behaviors among high school students at the national, state, and local levels, show that alcohol and other drug use negatively correlates with academic achievement after controlling for sex, race/ethnicity, and grade level (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Alcohol is the most widely abused substance among youth in the United States (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015); adolescent drinkers are more likely than adults to engage in binge drinking, and are at increased risk of physical and sexual assault, academic problems, drug use, and physical illness or death due to alcohol poisoning. It has been documented that females who report high levels of drinking report experiencing higher levels of academic difficulty compared to females who do not report high levels of drinking (Balsa, Giuliano, & French, 2011). Drug abuse among students also includes the presence of substance use and sale or trade on campus and during school-related activities, creating situations that are contradictory to a school climate of safety and support for learning. According to the 2015 YRBS, 21.7 percent of high school students in the United States were offered, sold, or given an illegal drug on school property during a twelve-month period.

School-based interventions to prevent or reduce substance abuse vary from those incorporating other determinants of school climate such as physical health (Project SPORT) (Werch, et al., 2003) to those focusing on implementing drug education curricula (NARCONON™ drug education) (Lennox & Cecchini, 2008). Findings of both interventions suggest that school-based programs targeting student drug use have positive effects. Project SPORT found that a brief sport-based screen and consultation program tailored to adolescents’ health habits may potentially reduce alcohol use while increasing exercise frequency, while Lennox & Cecchini’s study showed that adolescents who received the Narconon drug education curriculum showed reduced drug use across all tested categories; the program also produced changes in knowledge, attitudes, and perception of risk. Data suggests that funding towards programs that aim to prevent or decrease student substance abuse may be well-spent, as they have been shown to have positive, tangible outcomes that will increase school safety and foster academic success.

Effective Use of Technology

ESEA Section 4109 provides guidelines for program activities that support building technological capacity and infrastructure and support curricula using technology. Within this section of the literature review, the relationship between technologies and school safety will be explored as a mechanism by which learning can be conducted within schools. RAND Corporation identified twelve main school security technologies, defined as devices developed or implemented to prevent violence in schools and make schools safe (Schwartz, et al., 2016). These technologies include:

- Entry control equipment

- Identification technology

- Video surveillance technology

- Communication technology

- School-site alarm and protection systems

- Emergency alerts

- Metal detectors and X-ray machines

- Anonymous “tip lines”

- Tracking systems

- Maps of school terrain and bus routes

- Violence prediction technology

- Social media monitoring

The prevalence of these technologies in schools varies widely, along with evidence on their effectiveness at preventing, mitigating, and responding to threats to school safety.

Entry Control Equipment

Entry control equipment includes electronic door locks, barricades, posted signs, radio frequency identification (RFID) cards, and biometric access control systems and are designed to limit or prevent physical access to buildings and areas to unauthorized persons. In 2011–12, 88 percent of public schools and 80 percent of private schools utilized entry control equipment to restrict access to school buildings, and 44 percent of public schools and 42 percent of private schools used entry control equipment to limit access to grounds during the school day (Robers, Kemp, Rathbun, & Morgan, 2014). Expensive systems to install, no rigorous evidence exists to support a positive correlation between the use of entry control equipment and improved school safety outcomes (Schwartz, et al., 2016).

According to the Data Quality Campaign (DQC), 80 out of 112 state bills introduced concerning student data privacy in 2016 sought to ensure student privacy by banning the collection of such data as biometric data, and in some cases, predictive analytics as a whole. This may have implications in some safety technologies as entry control equipment, identification technology, violence prediction technology, and social media monitoring that may limit their prevalence in schools (Data Quality Campaign, 2016).

Identification Technology

Identification technology, employed widely by schools, is used to distinguish individuals with authorization to access school property from those who do not. Identification technology may include identification cards, parking stickers, and visitor badges. Rarer forms include palm scanners or “hand geometry identification devices,” which use infrared light to instantly capture a digital image of a parent’s or guardian’s hand, which can be used to cross-check the identity of adults who attempt to take a child out of school (Uhl & Wild, 2009). Iris recognition technology is another biometric identification technology, in which a scan of a person’s eyes is used (as opposed to the hand) to cross-check people (Uchida, Maguire, Solomon, & Gantley, 2004). In 2011–12, 7 percent of public schools and almost 3 percent of private schools reported requiring students to wear badges or picture identification (Robers, Kemp, Rathbun, & Morgan, 2014). No substantial studies exist that establish identification technology as effective in reducing school violence or threats, although the technology is inexpensive to establish aside from those involving biometrics.

As described in “Entry Control Equipment”, state bills banning the collection of such data as biometric data may have implications in the prevalence of this technology.

Video Surveillance Technology (VST)

Video surveillance technology is used primarily to deter criminals from conducting crime on school property by making it easier for crime to be seen. It is also used to help identify perpetrators if crimes do occur. VST includes cameras, closed circuit television (CCTV), video-recording devices, and video-motion detection systems. VST is one of the more popular technologies utilized by schools; in 2011–12, video cameras were used by 64 percent of public schools and 41 percent of private schools (Robers, Kemp, Rathbun, & Morgan, 2014). Data suggest that VST is more effective in thwarting property crimes like vandalism than preventing violence or crimes in schools (Garcia, 2001).

According to the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), laws concerning privacy issues and civil rights as they apply to VST may vary widely by state or region, and schools should consult an attorney before considering an electronic surveillance system. However, certain general guidelines are fairly consistently applied across most of the country:

- Cameras may not be used in an area where there is a “reasonable expectation of privacy”, examples of which include bathrooms, gym locker rooms/changing areas, and private offices;

- Camera use is generally acceptable in hallways, parking lots, front offices, gymnasiums and cafeterias where there is high foot traffic;

- Cameras should only be used in classrooms when the teacher is given an option and/or notification that a camera is to be used; and

- Dummy cameras should not be used, as the potential for temporary deterrent of crime is outweighed by the risk of a victim’s false impression that he/she will be rescued quickly in the event of an emergency.

Communication Technology

Communication devices connect classrooms, faculty and staff during and outside of school hours. Intercoms and two-way radios allow users to communicate quickly about incidents and risks and are used extensively in schools, because they serve communication functions other than reporting emergencies and suspicious behavior. There are no studies of these devices’ effects on school safety (Schwartz, et al., 2016).

Other communication technologies that are leveraged for school safety situations include school district television stations, local radio stations, websites, and social media. Privately licensed communication media are also used by districts across the country. For example, Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) in Los Angeles, California utilizes a system which generates personalized calls to parents and guardians regarding school emergencies (Los Angeles Unified School District, 2016). Many other school districts utilize similar systems.

School-Site Alarm and Protection Systems

School-site alarm systems are used to moderate and manage a threat to school safety that has already occurred. Local and silent alarms are triggered by the detection of atypical movement, heat or sound. The literature does not describe the prevalence of these systems in schools although they act similarly to fire alarm systems. A significant increase in the use of Use of panic buttons or alarms in schools occurred between 1997 to 2005 (Wilson & Henry, 2006). Since these technologies are primarily used after an event has occurred, there is no evidence to date that these systems actually prevent emergencies (Schwartz, et al., 2016).

Emergency Alerts

Emergency alerts are used to inform the school community of threats to school safety once they have occurred. to inform them of a crisis (e.g., intruder on school campus, school shooting). Phone and email alerts are sent to students, parents, and other community members to provide the school community with facts about potential or ongoing crises to keep them informed and up to date, and to ease community members’ minds and prevent false information from spreading. While there are no estimates of how many schools employ emergency alert systems, many schools have lists of emails and phone numbers of students, and oftentimes their parents, that would easily facilitate the use of a system. Additionally, many schools and school districts have a presence on at least one form on social media today through which emergency alerts may be posted. As with school-site alarm systems, since emergency alerts are activated during or following an event, there is no research evaluating the effect of this technology on school safety. However, frequent use of the alert system in place may overload users with trivial messages, which may inadvertently cause them to ignore messages received (Schwartz, et al., 2016).

Metal Detectors and X-Ray Machines

Metal detectors and X-ray machines are used to inspect students for weapons and other contraband and are designed to prevent the presence of weapons on school grounds. These technologies may be used for daily searches of all students, random inspections of all students, or random inspections of individuals. They are very rarely used in schools; in 2011–12, 5 percent of public schools and 1 percent of private schools conducted random metal detector checks on students, and almost 3 percent of public schools and 0.4 percent of private schools required students to walk through metal detectors daily (Robers, Kemp, Rathbun, & Morgan, 2014). Since installing this technology can be very expensive, it is worth noting that a review of research conducted over a 15-year period found that metal detectors have no demonstrable impact on the incidence of injuries, deaths, or threats of violence on school grounds (Hankin, Hertz, & Simon, 2011).

According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Northern California, schools have the right to install general metal detector systems (such as a system installed at the school entrance that all students must pass through), but they cannot target individual students for metal detector searches unless they have “reasonable suspicion” that they will find something in violation of school rules (American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California, 2015).

Anonymous “tip lines”

Tip lines are used to prevent incidents before they occur. Tip lines are thought to be most helpful in identifying when a weapon is brought to school, reporting plans to bring harm to self and others, and informing about drug use on school grounds (National Center for Education Statistics, 2004). Users can submit tips through phone hotlines, anonymous text-messaging services, and websites that allow anonymous posts. Students, family members, and community members are instructed in the use of these technologies.informed beforehand about how to submit a tip. There is no data on how prevalent “tip lines” are in schools. Anecdotal evidence suggests that tip lines may be useful, although no substantial studies exist on the subject.

Tracking Systems

Student tracking systems are intended to be carried by students via smartphone applications or other devices with GPS capability. GPS tracking systems placed on school buses can be used to track the location of a bus. There is little evidence on the prevalence of these systems to the extent that they are used by schools, but it is likely that they will be increasingly used due to the omnipresence of smartphones these days. There is no evidence on the effectiveness of student or school bus-tracking systems with regards to handling school safety threats, however, they may have important implications in locating special needs students and in tracking school bus routes to ensure that students are accounted for and have arrived at their destinations safely.

GIS-Informed Maps of School Terrain and Bus Routes

GIS-informed maps of school terrain and bus routes are designed for use in preparation for and response to school safety crises(National Law Enforcement and Corrections Technology Center, 2014). GIS software is used to plot transportation routes and maps of school property. School bus routes can be planned and modified, and even used to plot the residences of students against those of registered sex offenders to notify parents. GIS maps can also help emergency services workers respond to emergencies by identifying the locations of incidents and the ideal routes to reach them.

Violence Prediction Technology

Violence prediction technology is intended to prevent school violence before it occurs and works primarily through social media monitoring of student profiles online. The technology also uses information collected about individual or group demographics or tendencies from sources such as individual school records or national research databases. Violence prediction technology is not common, as it is an emerging technology that can be costly to implement. Further, there is no research on the effectiveness of this technology in preventing school violence.

As described in prior sections, state bills banning the use of predictive analytics to collect student data may lower the prevalence of violence prediction technology in schools.

Social Media Monitoring

Social media monitoring technology is utilized to screen social media platforms for issues that might precede violence, such as bullying or threats. Since these actions are increasingly taking place online, social media monitoring is thought to be helpful in preventing violence from occurring. This technology is emerging, and still under development. As such, it is not common in schools, and there is no evidence of its effectiveness.

According to the ACLU of Northern California, if a school starts a social media monitoring program, students and parents must be notified, allow students and parents to see the information that has been collected, and they must delete all information collected when a student leaves the district or turns 18. If a school does not have a social media monitoring program in place, students do not have the right to know what information school staff collects through their individual searching as public posts can be seen by anyone (American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California, 2015).

Student rights with respect to social media monitoring do differ, however, if school technology is being used to access social media as schools have the right to place restrictions on content accessed and may monitor activity to enforce these restrictions. As with violence prediction technology, state bills banning the use of predictive analytics to collect student data may lower the prevalence of social media monitoring in schools.

Summary

Safety is a central component of school climate, and therefore profoundly important to the social, emotional and academic successes of students (Bradshaw, Sawyer, & O’Brennan, 2007). Climate encompasses dimensions pertaining to safety, engagement, relationships and the school environment. A positive school climate powerfully influences the motivation to learn, and mitigates the negative impacts of socioeconomic disadvantages and neighborhood violence on academic success. Schools lacking a school climate with supportive norms, structures, and relationships have an increased likelihood of violence, victimization, absenteeism, punitive discipline, and reduced academic achievement. A greater understanding of the variables impacting school climate, and their relationship to academic outcomes may guide school reform efforts and ensure that all students have equal access to a well-rounded education that prepares them for success.

Safety is also a fundamental human need that must be met before all higher-level needs. Students who do not experience emotional, psychological, social, and physical safety are forced to focus on meeting these basic needs, and cannot devote significant energy to learning, academic achievement, accomplishments, and self-actualization. Perception of safety appears to be more important to student success than measurable incidents of violence, victimization, and trauma, and multiple studies of perceived school safety and academic performance demonstrate a correlation between student perceptions of safety and achievement in both math and ELA. Experiences of trauma, mental illness and emotional distress impair student performance, likely through intermediary factors such as PTSD and emotional distress. However, even traumatized students may thrive academically with appropriate interventions and approaches including trauma-informed practices, SWPBIS, and social and emotional learning programs.

Issues of physical safety, bullying, victimization, harassment, violence and substance abuse have long been correlated with decreased academic achievement in the research community. All impact student accomplishments by decreasing student engagement and connectedness to the school. Interventions to address these problems should focus on clear, consistent discipline, and positive, caring relationships with adults who model healthy behavior.

Advancements in technology have yielded a number of new potential techniques intended to ensure student safety and security and prevent violence. In general, most technologies are expensive to implement and install, and there is a distinct lack of evidence supporting the effectiveness of these methods.

Schools and districts can improve school climate and safety, and address social and emotional aspects of the school environment critical to learning; strategies to improve achievement should focus on evidence-based approaches to strengthening student experiences of safety, relationships, and the school environment.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Health and Safety"

Health and Safety is a set of regulations, policies, procedures, and guidelines that aim to prevent any accidents or injuries from occurring. Health and Safety procedures are essential to ensuring a safe, efficient working environment.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: