Self-report Psychological Tests Critique: The Big Five and Multiple Intelligences (MI)

Info: 11199 words (45 pages) Dissertation

Published: 25th Feb 2022

Tagged: Psychology

Introduction

The scientific study of human individual differences is a cornerstone subject area in modern psychology (XX). It is Plato’s statement more than 2000 years ago, “no two persons are born exactly alike”, that highlighted the need to consider individual differences in constructing new psychological theories (XX). Sir Francis Galton’s invention, psychometrics, is the initial inspiration for the development of various techniques of present psychological measurements (XX). However, it is James McKeen Cattell, considered the pioneer of psychometrics, who expanded Galton’s work, that is responsible for the development of modern psychological tests (Kaplan & Saccuzzo, 2010). Personality and intelligence are two popular area of modern individual differences studies. In fact, the first psychometric instruments were designed to measure the concept of intelligence (XX). Intelligence testing is aimed at measuring individual’s cognitive ability to acquire and apply knowledge (XX) while personality testing is aimed at identifying the various aspects of the personality or the emotional status of the individual (XX). Today, researchers agree that we can classify people according to their intelligence and personality characteristics with moderate success, however, since people are complex, there are multiple and often conflicting theories and evidence in this area of study ().

History of personality research

As mentioned earlier, Galton is one of the first researchers to apply the lexical hypothesis to the study of personality. Lexical hypothesis denotes that important personality characteristics of a group are more likely to be encoded into the group’s language as a single word (XX). Early explorations in personality psychology, therefore, ventured into the psycholexical classification of personality traits (XX). From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, the use of lexical hypothesis flourished in English psychology (XX).

In 1936, Allport and Odbert proposed one of the most influential psycholexical studies in the history of trait psychology. They identified 17,953 terms describing personality or behaviour, grouping them in four separate columns: neutral terms, temporary moods, social judgements and metaphorical terms (Allport & Odbert, 1936). Many of their terms could have been differently classified or placed into multiple categories and their work was criticised for being somewhat arbitrary and unfinished (XX). It was in 1943, when British and American psychologist, Raymond Cattell used factor analysis to investigate the overarching structure of the trait terms. Factor analysis is a statistical procedure for identifying hidden or overlapping patterns to reduce many variables into fewer numbers of factors (XX).

Applying the method to personality, Catell discovered 16 primary trait factors within the normal personality sphere and he constructed a self-report instrument using the clusters of personality traits, known as the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF) (XX). Later, he factor-analysed his 16 primary traits and found five secondary traits, now known as the Big Five. Following this, Dr Hans Eysenck (1970) proposed a three-factor model of Psychoticism, Extraversion and Neuroticism, also known as the PEN model (XX). In 1976, Hans and Sybil Eysenck developed the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ) to measure the traits described in the PEN model of personality.

Like Catell’s work, at least three other group of researchers independently identified the same five factors of personality (XX): Ernest Tupes and Raymond Christal in 1961 (XX), Goldberg at the Oregon Research Institute (XX) and Costa and McCrae at the National Institutes of Health (XX). Although these sets of researchers used different methods in finding the five traits, each of the sets of traits was found to be “highly inter-correlated and factor-analytically aligned” (XX). Each set of traits comprises of two opposite but correlated aspects under the broad domain of trait (XX). The final renown five-factor model (FFM), now used in the Big Five Inventory (BFI), is made up of the dimensions of Agreeableness (friendliness and likeability), Conscientiousness (reliability and willingness to achieve), Negative Emotionality or Neuroticism (volatility vs. stable mood), Extraversion (sociability), and Openness or Open-mindedness (broad-mindedness and creativity) (XX).

Since 1949, the Big Five Inventory (BFI) has been revised four times and the current version was developed in 1993 (XX). The test has since been re-standardised in 2002 and 2011 and has been adapted into more than 35 languages, allowing validation from cross-cultural studies (XX).

History of intelligence research

Galton was one of the first scientists to study intelligence in the late 1800s. He believed differences in individuals can be measured scientifically and attempted to measure intelligence through reaction time tests (Simonton, 2003). He introduced the use of questionnaires and surveys for collecting data for his studies (Galton, 1869). His success forms the basis for many later researchers in intelligence testing. At present, psychometrics is applied widely in educational assessments to measure linguistics and logical abilities (XX).

The first intelligence test, known today as the Stanford-Binet IQ test is developed by Frenchman Alfred Binet in the 20th century and is the basis of modern-day intelligence tests (XX). With the assumption that intelligence develops with age but the individual’s cognitive standing remain stable in comparison to peers, he designed a questionnaire that could distinguish children of all ages with learning disabilities (Binet, X). The test used a single number, known as the intelligence quotient (or IQ), to represent an individual’s score on the test. However, Binet suggested that intelligence is a broad concept, unquantifiable by a single number. He insisted intelligence changes over time and is influenced by a number of factors and thus is comparable only with children with similar backgrounds (XX).

Throughout the years, researchers proposed a variety of theories to explain the nature of intelligence. Charles Spearman is a British psychologist who introduced the concept of general intelligence or g factor (XX). His claims include people who perform well in one cognitive test also perform well in the other. Thus, he concluded intelligence is a general cognitive ability that can be measured. By way of contrast, a theory by Psychologist Louis L.Thurstone claimed that intelligence is a made-up of seven different primary mental abilities (XX). Recently, Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences became widely used in psychological testing. He outlined eight distinct types of intelligence, namely, Visual-spatial intelligence, Verbal-linguistic intelligence, Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence, Logical-mathematical intelligence, Interpersonal intelligence, Musical intelligence, Intrapersonal intelligence, and Naturalistic intelligence. He declared that quantifying human intelligence is an inaccurate way to measure people’s abilities (XX). While many educators and school administrators were inspired by Gardner’s theory, many others from the field of education and psychology questioned criticised his work for the lack of empirical evidence (XX). Nevertheless, his work remains popular among educators today (XX).

Assessment aims

In this paper, personality and Intelligence will be measured using the online versions of the tests. The Big Five Project Personality test will be used to measure personality (John, & Soto, 2016), which uses a 5-point Likert scale to determine how strong you agree with each of the 60 statements about yourself in various situations. The scale ranges from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), which generated results in percentiles. Multiple Intelligences for Adult Literacy and Education is a 56 statements questionnaire, utilised to measure different intelligence strengths on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from Statement does not describe you at all (1) to Statement describes you exactly (5) (1992).

The results from the two psychological tests (John, 2000; Multiple Intelligences for Adult Literacy and Education, n.d.) will be evaluated and discussed later. It is crucial to keep in mind that in the comparison between the first and second time the tests were taken, a better (and balanced) mood was observed during the first attempt.

Results

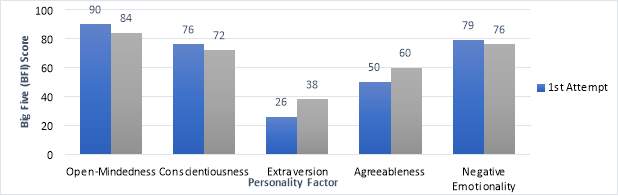

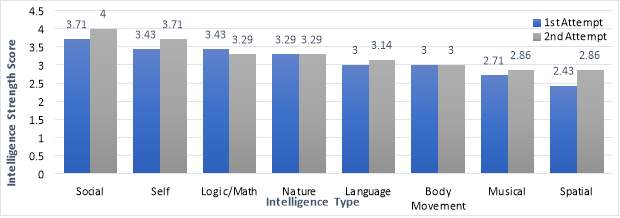

Figure 1 and 2 show the results of the Big Five Project personality test and the Multiple Intelligence tests produced from the two separate attempts. The first attempt was on Tuesday, 8 May 2018 at 10 am and the second attempt, on Saturday, 19 May 2018 at 10 am. It is necessary to note that during the first attempt, I was in a balanced mood at work and during the second attempt, I was in a considerably bad mood.

Figure 1

BFI scores on the Big Five Personality test

According to Figure 1, the BFI score was highest for Open-mindedness in both attempts (90%, 84%) and lowest for Extraversion (26%, 38%). The scores for Conscientiousness and Negative Emotionality were also high (above 65%), with Agreeableness considerably increasing from 50% to 74% in the first and second attempts.

Figure 2

Intelligence scores on the Multiple Intelligence (MI) test

As Figure 2 shows, in both attempts, Social Intelligence score was the highest (3.71, 4) and the Spatial Intelligence score was the lowest (2.43, 2.86). The scores for other types of intelligence were also persistent across two attempts and they range from 3.71 to 2.71.

Evaluation and Reflection

The Big Five Project Personality Test Results

The results from the BFI test (John, 2000) did not come as a surprise for me. This is because I have taken the test before and knew that I will score highly on Openness, Agreeableness and Negative Emotionality and low on Extraversion. However, my scores for Conscientiousness are now higher than the previous score I remember (

The definition of the Open-mindedness covers a broad range of traits associated with intellectual curiosity and an adventurous mien (McCrae & Costa, 1987). Open-minded individuals are described as intellectual, unconventional, independent and imaginative (Zuckerman, 1994; p. 31). The high score on this trait reflects my personality as I love learning and exploring new cultures and activities. Open-mindedness is defined by Authentic Happiness Coaching (2004) as being readily acceptable and in search of knowledge or truth that is against a person’s own beliefs and understanding such as alternate religious beliefs. Being an atheist despite coming from a religious family shows that I am open to disparate ideologies and thus, scoring high in this trait. In addition, research has suggested that multicultural exposure is linked to openness in individuals (Leung & Chiu, 2008; Livert, 2015; Chao, Kung & Yao, 2015; Maddux & Galinsky, 2009). Not only did I grow up in an Asian family and went to an International school, I have lived and studied in three different countries in my life. A high score in openness (90% and 84%) is therefore accurate in my case. Similarly, in 2015, Işık and Üzbe performed an analysis of meaning in life among adults and found that individuals who are open to experiences search for meaning and purpose of life and adhere to ventures that serve these purposes. Since I am working towards changing my career from a public relation specialist to a clinical psychologist, it is evident that I am devoted to what I believe is my purpose in life. Scoring high on this trait is, therefore, a reliable description of my personality.

Conscientiousness is the trait that captures individual differences in the degree of organisation, persistence and motivation to succeed goals (Bartley, & Roesch, 2011; Duckworth, Weir, Tsukayama, & Kwok, 2012). High conscientious people are known to be self-disciplined, focused, persistent and goal-driven (Packer, Fujita, & Herman, 2013; Hülsheger & Maier, 2010). I have been told I am determined and that I have high standards by the people around me recently, contrary to what I used to be when I was younger. Oliver, Guerin, & Coffman, 2009 studied the effect of the big five parental personality traits on their offspring and found that children of conscientious mothers are genetically predisposed to the trait themselves. This suggests that having hard-working parents is the reason I scored moderately high in Conscientiousness (76% and 72%). Additionally, research has shown that the average level of conscientiousness escalates as a person ages (Lucas, & Donnellan, 2011). They claimed that people’s average levels of conscientiousness increase from adolescence to middle age due to the increasing demands of adult roles (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005; Wu, 2016). As I transitioned from being a fresh graduate to a working adult, it was obvious that I had to step up to fulfil my adult roles both at home and work. Naturally, this explains why my conscientiousness scores have increased now compared to the past.

A low score on extraversion (26% and 38%) implies that I prefer solitude over spending time socialising with others, i.e. an introvert (Shatz, 2005). While it was true that I prefer to spend most of my time alone, I was not convinced the first time I took the test because I periodically enjoy going out with family and friends, having discussions with them and taking part in fun activities. I previously suspected I may be an ambivert, which is in between the introvert and extrovert extremes (Davidson, 2017). However, Cooper (2013) identified the “signs that point someone closer to an introvert” (p. 13), and highlighted that while they need alone time, introverts enjoy one-on-one time or in small groups with family and close group of friends regularly. They also pointed out that introverts are not always shy, they take part in social activities, giving that they shall get some quiet time after to recharge. Hence, the study convinced me that I may be closer to be an introvert than an ambivert.

Agreeableness is associated with traits such as being kind, generous, sympathetic and trusting of other people (Barrick et al., 2001; Costa & McCrae, 1992; Kabat-Zinn, 1990). In Buddhism, compassion for others is the heart of its teachings (Goodman, 2014). Therefore, being empathetic and having a concern for others is engraved in the personality of Buddhist followers like me and thus, possess an above-average level of the trait (Ark, 2014). Besides, longitudinal studies such as Furham and Cheng (2015) highlighted that females consistently score higher than males in Agreeableness (Weisberg, DeYoung, & Hirsh, 2011). Despite the claims, as mentioned above, my scores for Agreeableness is moderate in both attempts (50% and 60%). I agree that previous working experience in the business field has taught me to be more focused on the tasks and less on other people, hence, I hold a balanced level of agreeableness.

Lebowitz (2016) proposed individuals high in Negative Emotionality or Neuroticism are vulnerable to anxiety, depression, worry, and low self-esteem. Neuroticism encompasses emotional stability and general temper of a person (Judge, Erez, Bono, & Thoresen, 2002). It is likely no surprise that people high in this trait do not produce one’s best work. Generally, Neuroticism was found to be inversely correlated with other Big Five traits (Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion and Open-mindedness) (Ones, Viswevaran, & Reiss, 1996). In fact, a long-term study by Soldz and Vaillant showed that Neuroticism is linked to addiction, alcohol abuse, low resilience and mental health issues (1999). By contrast, I scored moderately high on Negative Emotionality and on other traits except for Extraversion. Also, since I regularly meditate and do yoga to manage my moods and thoughts, I predicted my score to be moderate on the trait (Giluk, 2009). For this reason, it would be useful to explore other sub traits of Negative Emotionality (Roccas, Sagiv, Schwartz, & Knafo, 2002).

The Multiple Intelligence (MI) Test Results

I find the results of the MI test to be somewhat accurate. The results claimed I am mostly socially intelligent and least intelligent spatially.

Gardner (1993) has identified the two aspects of personal intelligence as social intelligence and intrapersonal intelligence. Social intelligence is measured by the capacity to detect moods and respond appropriately to others and individuals strong in social intelligence are good at understanding and interacting with other people (Summerfield, Kloosterman, Antony & Parker, 2006). Intrapersonal intelligence is defined by the degree of self-awareness and being in tune with one’s feelings, values, beliefs and thinking processes (Gardner, 1993). I believe being socially intelligent and self-aware are the reasons for my career and personal success today. Jacobs (2004) (in Pearson, 2011) has proposed that personal intelligence is a necessity for clinicians. My ambition to dedicate myself to helping others and becoming a clinical psychologist, I believe, is the result of having high interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligences.

Researchers suggested links between logical-mathematical intelligence and spatial intelligence (Tirri, & Nokelainen, 2008). On the contrary, I scored high in logical-mathematical intelligence but the lowest in spatial intelligence. Generally, individuals with this intelligence are good at reasoning and comprehending abstract concepts (Tirri & Komulainen, 2002). Spatial intelligence measures the ability to visualize and work with multidimensional objects (Gardner, 2017). Having a background in business and engaging in scientific research currently explain why I have scored high in Logical-mathematical intelligence, but it is not clear why I have scored low on Spatial intelligence when I have been driving a car for two years now.

Limitations of BFI and MI tests

While no psychological tests are free from errors, BFI and MI have been criticized on one ground or another (X). First, Pervin (1993) and Mischel (1995) claimed that reliability of psychological tests depends upon the individuals, circumstances, situations and the parameters adopted for the testing sessions. In contrast, results of the two psychological tests (John, 2015; Multiple Intelligences for Adult Literacy and Education, n.d.) were different between the two times the tests were taken, even when the environment and the timing of the test were controlled. Secondly, the Big Five is not based on underlying theory, but simply a data-driven description of traits (XX). Similarly, to date, no published studies has offered evidence of the validity of the MI and Gardner and Connell (2000) admitted that there is “little hard evidence for MI theory” (p. 292). Evidently, the reliability and validity of the tests remain low.

Social desirability bias and mood effects should be addressed when using self-report measures (XX). Researchers claim that people give responses different descriptions because they wish to see themselves as described (Robins et al., 2001). In addition, evidence shows that an individual’s mood can affect their responses (Jylhä, Melartin, Rytsälä, & Isometsä, 2009). In 2009, Matthews and colleagues analysed the personality–mood relationship. The study suggested that neuroticism influences mood states in individuals across situations suggesting that since I tend to be a neurotic person, the variability in scores between my first and second attempts are explained by my mood state caused by other factors prior to the experiment (Matthews, Deary, & Whiteman, 2009). Furthermore, psychologists including XX (X) criticized the MI test, claiming that the accuracy of self-report responses itself depends upon individual’s introspective ability (X). Nonetheless, since I achieved a high score in Intrapersonal intelligence, this should not be a serious problem at present.

Finally, various researchers have raised concerns regarding the Lexical hypothesis in the established five-factor models of personality (Block, 2010; Lamiell 2003; Rosenbaum and Valsiner 2011). John, Angleitner, and Ostendorf (1988) criticized that the use of lexica of human languages may not explain all variations in the human personality and translation of the concept in different natural languages may not result what was intended in the original language. This suggests that I, being Asian, may have interpreted the definition of traits in relation to my own culture. Thus, this underlines the serious need for ways to assure consistency and validity among cross-cultural studies (XX).

Conclusion

The tests used in the study were somewhat useful in assessing my intelligence and personality. Some researchers argued Big One or Big Two model be more appropriate (XX), while others are opposed to the idea of personality itself (XX). The idea of multiple intelligences is still shadowed by the g factor theory as many studies show evidence of the underlying mental ability affecting cognitive tasks performance (X). To sum up, individual differences is a young science and likely will change and evolve with time. For there are questions remaining regarding the measurement and classification of human personality and intelligence, it is necessary to continue with the research while keeping an open mind and a critical perspective as we go along.

References

Allport, G. W., & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait-names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychological Monographs, 47(1), i-171. doi:10.1037/h0093360

Ark, W. C. (2014). Effects of meditation practice on altruism, empathy, guilt, and depression among theravada buddhists (Order No. 3664309). Available from Health Research Premium Collection; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I. (1729107651). Retrieved 3 June 2018 from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1729107651?accountid=14620

Bartley, C. E., & Roesch, S. C. (2011). Coping with daily stress: The role of conscientiousness. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(1), 79-83. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.027

Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 453–484.

Cooper, B. B. (2013). Are you an introvert or an extrovert?. American Swimming Coaches Association (ASCA) Newsletter, (8), 10-15.

Chao, M. M., Kung, F. Y. H., & Yao, D. J. (2015). Understanding the divergent effects of multicultural exposure. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 47, 78-88. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.03.032

Ching, C. M, Church, A. T., Katigbak, M. S., Reyes, J. A. S., Tanaka-Matsumi, J., Takaoka, S., Zhang, H., Shen, J., Arias, R. M., Rincon, B. C., Ortiz, F. A. (2014). The manifestation of traits in everyday behavior and affect: A five-culture study. Journal of Research in Personality, 48, 1-16. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2013.10.002

Davidson, I. J. (2017). The ambivert: A failed attempt at a normal personality. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 53(4), 313-331. doi:10.1002/jhbs.21868

DeYoung, C. G., Grazioplene, R. G., & Peterson, J. B. (2012). From madness to genius: The Openness/Intellect trait domain as a paradoxical simplex. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(1), 63-78. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2011.12.003

Duckworth, A. L., Weir, D., Tsukayama, E., & Kwok, D. (2012). Who does well in life? conscientious adults excel in both objective and subjective success. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 356. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00356

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1975). Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Fleeson, W., & Gallagher, P. (2009). The implications of big five standing for the distribution of trait manifestation in behavior: Fifteen experience-sampling studies and a meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1097-1114. doi:10.1037/a0016786

Furnham, A., & Cheng, H. (2015). Early indicators of adult trait agreeableness. Personality and Individual Differences, 73, 67-71. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.025

Gardner, Howard (1993), Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice, Basic Books, ISBN 046501822X https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=eZQq3z7joHkC&q=046501822X&dq=046501822X&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj7rfDa57fbAhUNV8AKHRzLBGUQ6AEIKTAA

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2017). Taking a multiple intelligences (MI) perspective. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 40. doi:10.1017/S0140525X16001631

Giluk, T. L. (2009). Mindfulness, big five personality, and affect: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8), 805-811. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.026

Goodman, C. (2014). Consequences of Compassion: An Interpretation and Defense of Buddhist Ethics. Oxford University Press.

Hülsheger, U. R., & Maier, G. W. (2010). The careless or the conscientious. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(2), 246-254. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2010.04.001

John, O. P. (2000). The Big Five Project Personality test [Measurement instrument]. Retrieved from https://www.outofservice.com/bigfive/

John, O. P., Angleitner, A. & Ostendorf, F. (1988). The lexical approach to personality: A historical review of trait taxonomic research. European Journal of Personality. 2. 171 – 203. doi:10.1002/per.2410020302.

Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2002). Are measures of self-esteem, neuroticism, locus of control, and generalized self-efficacy indicators of a common core construct? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 693-710. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.3.693

Krumpal, I. (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Quality & Quantity, 47(4), 2025-2047. doi:10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9

Livert, D. (2015). Understanding the role of openness to experience in study abroad students. Journal of College Student Development, 56(6), 619-625.

Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (2011). Personality development across the life span: Longitudinal analyses with a national sample from Germany. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(4), 847-861. doi:10.1037/a0024298

Lebowitz, S. (2016). The ‘Big 5’ personality traits could predict who will and won’t become a leader. Business Insider. Retrieved 3 June 2018 from http://www.businessinsider.com/big-five-personality-traits-predict-leadership-2016-12

Leung, A. K. -., & Chiu, C. (2008). Interactive effects of multicultural experiences and openness to experience on creative potential. Creativity Research Journal, 20(4), 376-382. doi:10.1080/10400410802391371

Maddux, W. W., & Galinsky, A. D. (2009). Cultural borders and mental barriers: The relationship between living abroad and creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1047-1061. doi:10.1037/a0014861

Matthews, G., Deary, I. J., & Whiteman, M. C. (2009). Personality traits (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81-90. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81

Multiple Intelligences for Adult Literacy and Education (n.d.). [Measurement instrument]. Retrieved from: http://www.literacynet.org/mi/assessment/findyourstrengths.html

Oliver, P. H., Guerin, D. W., & Coffman, J. K. (2009). Big five parental personality traits, parenting behaviors, and adolescent behavior problems: A mediation model. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(6), 631-636. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.05.026

Ones, D. S., Viswesvaran, C., & Reiss, A. D. (1996). Role of social desirability in personality testing for personnel selection: The red herring. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 660-679. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.81.6.660

Packer, D. J., Fujita, K., & Herman, S. (2013). Rebels with a cause: A goal conflict approach to understanding when conscientious people dissent. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(5), 927-932. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2013.05.001

Pearson, M. (2011). Multiple intelligences and the therapeutic alliance: Incorporating multiple intelligence theory and practice into counselling. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 13(3), 263-278. doi:10.1080/13642537.2011.596725

Robins, R. W., Tracy, J. L., Trzesniewski, K., Potter, J., & Gosling, S. D. (2001). Personality correlates of self-esteem. Journal of Research in Personality, 35(4), 463-482. doi:10.1006/jrpe.2001.2324

Roccas, S., Sagiv, L., Schwartz, S. H., & Knafo, A. (2002). The Big Five personality factors and personal values. Personality and Social Psychology, 28, 789-801. doi:10.1177/0146167202289008

Shatz, S. M. (2005). The psychometric properties of the behavioral inhibition scale in a college-aged sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(2), 331-339. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.01.015

Soldz, S., & Vaillant, G. E. (1999). The Big Five personality traits and the life course: A 45-year longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 33, 208-232. doi:10.1006/jrpe.1999.2243

Summerfeldt, L. J., Kloosterman, P. H., Antony, M. M., Parker, J. D. A. (2006). Social anxiety, emotional intelligence, and interpersonal adjustment. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 28(1), 57-68. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10862-006-4542-1

Sutin, A. R., Luchetti, M., Robins, R. W., Stephan, Y., & Terracciano, A. (2017). Parental educational attainment and adult offspring personality: An intergenerational life span approach to the origin of adult personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(1), 144-166. doi:10.1037/pspp0000137

Tirri, K., & Nokelainen, P. (2008). Identification of multiple intelligences with the multiple intelligence profiling questionnaire III. Psychology Science Quarterly, 50(2), 206-221.

Tirri, K., & Komulainen, E. (2002). Modeling a self-rated intelligence-profile for virtual university. In H. Niemi & P. Ruohotie (Eds.), Theoretical understandings for learning in virtual university,139-168. Hämeenlinna, FI: RCVE.

van Hiel, A., Kossowska, M., & Mervielde, I. (2000). The relationship between openness to experience and political ideology. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(4), 741-751. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00135-X

Weisberg, Y. J., Deyoung, C. G., & Hirsh, J. B. (2011). Gender differences in personality across the ten aspects of the big five. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 178. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00178

Wu, C. (2016). Personality change via work: A job demand–control model of big-five personality changes. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 92, 157-166. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2015.12.001

Zuckerman, M. (1994). Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Appendices

Appendix A

Big Five Project Personlaity Test (BFI)

Take this psychology test to find out about your personality! This test measures what many psychologists consider to be the five fundamental dimensions of personality.

- Learn more about the Big Five by reading answers to commonly asked questions.

- Read our consent form, which explains the benefits of this free, anonymous test and your rights.

- There are no “right” or “wrong” answers, but note that you will not obtain meaningful results unless you answer the questions seriously.

- These results are being used in scientific research, so please try to give accurate answers.

- Your results will be displayed as soon as you submit your answers.

Top of Form

As you are rating yourself, you are encouraged to rate another person. By rating someone else you will tend to receive a more accurate assessment of your own personality. Also, you will be given a personality profile for the person you rate, which will allow you to compare yourself to this person on each of five basic personality dimensions. Try to rate someone whom you know well, such as a close friend, coworker, or family member.

If you would like to compare your personality to another person’s, please select how you are related to the other person.

(Click for choices)My FriendMy RoommateMy Co-workerOther (non-relative)My SisterMy BrotherMy Half-sister or half-brotherMy MotherMy FatherMy SonMy DaughterOther (family relative)My GirlfriendMy BoyfriendMy Partner (significant other)My Spouse

Directions: The following statements concern your perception about yourself in a variety of situations. Your task is to indicate the strength of your agreement with each statement, utilizing a scale in which 1 denotes strong disagreement, 5 denotes strong agreement, and 2, 3, and 4 represent intermediate judgments. In the boxes after each statement, click a number from 1 to 5 from the following scale:

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Neither disagree nor agree

- Agree

- Strongly agree

There are no “right” or “wrong” answers, so select the number that most closely reflects you on each statement. Take your time and consider each statement carefully. Once you have completed all questions click “Submit” at the bottom.

I am someone who…

1. Is outgoing, sociable

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

2. Is compassionate, has a soft heart

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

3. Tends to be disorganized

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

4. Is relaxed, handles stress well

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

5. Has few artistic interests

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

6. Has an assertive personality

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

7. Is respectful, treats others with respect

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

8. Tends to be lazy

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

9. Stays optimistic after experiencing a setback

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

10. Is curious about many different things

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

11. Rarely feels excited or eager

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

12. Tends to find fault with others

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

13. Is dependable, steady

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

14. Is moody, has up and down mood swings

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

15. Is inventive, finds clever ways to do things

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

16. Tends to be quiet

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

17. Feels little sympathy for others

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

18. Is systematic, likes to keep things in order

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

19. Can be tense

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

20. Is fascinated by art, music, or literature

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

21. Is dominant, acts as a leader

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

22. Starts arguments with others

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

23. Has difficulty getting started on tasks

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

24. Feels secure, comfortable with self

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

25. Avoids intellectual, philosophical discussions

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

26. Is less active than other people

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

27. Has a forgiving nature

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

28. Can be somewhat careless

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

29. Is emotionally stable, not easily upset

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

30. Has little creativity

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

31. Is sometimes shy, introverted

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

32. Is helpful and unselfish with others

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

33. Keeps things neat and tidy

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

34. Worries a lot

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

35. Values art and beauty

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

36. Finds it hard to influence people

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

37. Is sometimes rude to others

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

38. Is efficient, gets things done

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

39. Often feels sad

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

40. Is complex, a deep thinker

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

41. Is full of energy

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

42. Is suspicious of others’ intentions

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

43. Is reliable, can always be counted on

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

44. Keeps their emotions under control

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

45. Has difficulty imagining things

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

46. Is talkative

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

47. Can be cold and uncaring

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

48. Leaves a mess, doesn’t clean up

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

49. Rarely feels anxious or afraid

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

50. Thinks poetry and plays are boring

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

51. Prefers to have others take charge

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

52. Is polite, courteous to others

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

53. Is persistent, works until the task is finished

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

54. Tends to feel depressed, blue

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

55. Has little interest in abstract ideas

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

56. Shows a lot of enthusiasm

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

57. Assumes the best about people

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

58. Sometimes behaves irresponsibly

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

59. Is temperamental, gets emotional easily

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

60. Is original, comes up with new ideas

| Strongly Disagree |

|

Strongly Agree |

Bottom of Form

Appendix B

Multiple Intelligence (MI) Test Questionnaire

This form can help you determine which intelligences are strongest for you. If you’re a teacher or tutor, you can also use it to find out which intelligences your learner uses most often. Many thanks to Dr. Terry Armstrong for graciously allowing us to use his questionnaire.

Instructions: Read each statement carefully. Choose one of the five buttons for each statement indicating how well that statement describes you.

1 = Statement does not describe you at all

2 = Statement describes you very little

3 = Statement describes you somewhat

4 = Statement describes you pretty well

5 = Statement describes you exactly

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1. I pride myself on having a large vocabulary. | |||||

| 2. Using numbers and numerical symbols is easy for me. | |||||

| 3. Music is very important to me in daily life. | |||||

| 4. I always know where I am in relation to my home. | |||||

| 5. I consider myself an athlete. | |||||

| 6. I feel like people of all ages like me. | |||||

| 7. I often look for weaknesses in myself that I see in others. | |||||

| 8. The world of plants and animals is important to me. | |||||

| 9. I enjoy learning new words and do so easily. | |||||

| 10. I often develop equations to describe relationships and/or to explain my observations. | |||||

| 11. I have wide and varied musical interests including both classical and contemporary. | |||||

| 12. I do not get lost easily and can orient myself with either maps or landmarks. | |||||

| 13. I feel really good about being physically fit. | |||||

| 14. I like to be with all different types of people. | |||||

| 15. I often think about the influence I have on others. | |||||

| 16. I enjoy my pets. | |||||

| 17. I love to read and do so daily. | |||||

| 18. I often see mathematical ratios in the world around me. | |||||

| 19. I have a very good sense of pitch, tempo, and rhythm. | |||||

| 20. Knowing directions is easy for me. | |||||

| 21. I have good balance and eye-hand coordination and enjoy sports which use a ball. | |||||

| 22. I respond to all people enthusiastically, free of bias or prejudice. | |||||

| 23. I believe that I am responsible for my actions and who I am. | |||||

| 24. I like learning about nature. | |||||

| 25. I enjoy hearing challenging lectures. | |||||

| 26. Math has always been one of my favorite classes. | |||||

| 27. My music education began when I was younger and still continues today. | |||||

| 28. I have the ability to represent what I see by drawing or painting. | |||||

| 29. My outstanding coordination and balance let me excel in high-speed activities. | |||||

| 30. I enjoy new or unique social situations. | |||||

| 31. I try not to waste my time on trivial pursuits. | |||||

| 32. I enjoy caring for my house plants. | |||||

| 33. I like to keep a daily journal of my daily experiences. | |||||

| 34. I like to think about numerical issues and examine statistics. | |||||

| 35. I am good at playing an instrument and singing. | |||||

| 36. My ability to draw is recognized and complimented by others. | |||||

| 37. I like being outdoors, enjoy the change in seasons, and look forward to different physical activities each season. | |||||

| 38. I enjoy complimenting others when they have done well. | |||||

| 39. I often think about the problems in my community, state, and/or world and what I can do to help rectify any of them. | |||||

| 40. I enjoy hunting and fishing. | |||||

| 41. I read and enjoy poetry and occasionally write my own. | |||||

| 42. I seem to understand things around me through a mathematical sense. | |||||

| 43. I can remember the tune of a song when asked. | |||||

| 44. I can easily duplicate color, form, shading, and texture in my work. | |||||

| 45. I like the excitement of personal and team competition. | |||||

| 46. I am quick to sense in others dishonesty and desire to control me. | |||||

| 47. I am always totally honest with myself. | |||||

| 48. I enjoy hiking in natural places. | |||||

| 49. I talk a lot and enjoy telling stories. | |||||

| 50. I enjoy doing puzzles. | |||||

| 51. I take pride in my musical accomplishments. | |||||

| 52. Seeing things in three dimensions is easy for me, and I like to make things in three dimensions. | |||||

| 53. I like to move around a lot. | |||||

| 54. I feel safe when I am with strangers. | |||||

| 55. I enjoy being alone and thinking about my life and myself. | |||||

| 56. I look forward to visiting the zoo. | |||||

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Psychology"

Psychology is the study of human behaviour and the mind, taking into account external factors, experiences, social influences and other factors. Psychologists set out to understand the mind of humans, exploring how different factors can contribute to behaviour, thoughts, and feelings.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: