Simulation for acute gynaecological emergencies - a training needs analysis

Info: 7372 words (29 pages) Dissertation

Published: 22nd Feb 2022

Introduction

Simulation in teaching doctors remains and has been recognized to be an important contributary factor to a doctor’s development, towards becoming or transitioning into a better clinician and practitioner. This aspect is particularly significant in junior doctors who start a rotation in gynaecology or for those who are starting their journey as a specialty trainee in gynaecology. In order to ascertain the necessity and effectiveness of the simulation process in gynaecological emergencies, an initial survey has been carried out to conduct a pre - simulation training needs analysis.

This survey was carried out in acute hospital from a National Health Service (NHS) Trust. The second part of the project is an intervention made up of several pilot simulation sessions, concluded with a final survey. The results were analysed and recommendations drawn to include gynaecological emergencies simulation as a mandatory part of the training programme.

A literature review was carried out to assess and understand the role of simulation in health care practice, over the past years. Simulation is a significant part of many other work fields. Obstetric emergencies skill-drills, have been introduced relatively recently in healthcare, and have been developed to a high grade of teaching and expertise. This seem to developed as a response after NHS had to pay huge compensations towards the affected patients, obstetrics being in the top three, on the third place of the most negligence claims in 2013 - 2014 (NHSLA - 2017). Although accounting for 10% overall specialties claims made, obstetrics is actually the most expensive, with a cost of 41% of the total spend on clinical negligence.

On the other hand, Gynaecology accounts only for 6% of the clinical negligence claims. In order to minimize the complications rates and to improve the patients’ safety, many NHS Trusts hospitals across England adapted to this situation and they set up special simulation suits, investing a considerable amount of money, with the approximate cost of £ 50000 (WBWire - 2017). The team usually involves anaesthetists, obstetrician, midwives, nurses and faculty team that will coordinate the simulation process. There were only a few attempts of gynaecological simulations in the United Kingdom (UK), and all over the world. Most of them were directed towards the laparoscopic simulation rather than an emergency point of view. Recently, some of the Deaneries across Health Education England (HEE), have introduced in their regional training days (RTD) some aspects of the gynaecological simulations.

Again, mainly adapted towards technical aspects and malfunctions rather than clinical emergencies. The gynaecological emergencies are underestimated, the most junior doctors having lack of practice and experience, leading to delays in diagnosis and treatment. In few UK hospitals, had been introduced as a part of the rota, a dedicated oncall emergency gynaecological consultant. But even with this, it was not possible to minimize the effect of the shortage of registrar level staff and the inexperience of the junior doctors. It is therefore important that a gynaecology specialist step up and be involved in the gynaecology simulation process to improve the quality of the service.

Aim

The aim of the survey was:

To assess the impact of a gynaecological simulation exercise in gynaecological emergencies.

Objectives

- Conducting a pre-simulation survey to establish the knowledge and experience of the junior doctors, in dealing with gynaecological emergencies, in an acute hospital, as per National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guidelines

- Performing a post-simulation survey, to assess the important role of simulation in improving their practice

- To analyse the results and make adjustments depending on the individual needs, using simulation scenarios on various gynaecological emergencies

- To highlight any lack of knowledge in the clinical or practical aspect of the emergency and to improve through simulation scenarios, following the protocol and guidelines of NICE and RCOG

Background

Simulation is virtual reality through which various skills may be checked, developed and improved. In 1903, Orville Wright piloted the first airplane prototype above a beach in North Carolina. The flight lasted 12 seconds, covering 120 feet, on 20 feet above ground (Crouch, 1989). In 1909, it is developed the first flight simulator, named the “Antoinette Trainer”, made of two half-barrels, that were moved by assistants, while pilot was trying to improve the balance of the machine (Havkar, 2018).

In 1914, at the beginning of the First World War, the German loss accounted for more than 100 aircraft, due to accidents, not by enemy kills. An internal investigation showed that 90 % of all accidents were due to human error, 8 % to aircraft malfunctions and only 2 % to enemy shooting (Havkar, 2018). The cost of initial simulation hour was approximately 50 $. The science developed and the flight simulation updated constantly. The pilots had certain mandatory hours of simulation, before flying on a real aircraft. It has taken 100 years, for the simulation to be recommended officially in medical education, by the Word Health Organisation (WHO), in 2009.

It has been debated that with the changes in medicine, assessment methods need to be changed (Broadfoot, 1994). And in order to improve the assessments, an increase in the range of qualities that need to be assessed (Black, 1994). Furthermore, the clinical simulation’s benefits are widely reported in literature, adding more strength for being used in healthcare education. (Issenberg et al. 2005; McGaghie et al. 2010 a). General Medical Council (GMC) is doctor’s regulatory body, in charge with setting the standards and requirements for delivering excellence in medical education. New set of assessment tool have been introduced to assess more the attitudes and the professionalism, rather than concentrating on the length of the training programme. In 2007, RCOG, at the recommendations of the Postgraduate Medical Education Training Board (PMETB), introduced the workplace-based assessment (WPBA). The evidence of competencies is achieved step-wise, as per Miller’s pyramid concept in figure 1.

![Miller's pyramid [Source: http://www.faculty.londondeanery.ac.uk/e-learning/setting-learning-objectives/some-theory]](https://images.ukdissertations.com/34/0364039.001.jpg)

Figure 1.

Source: http://www.faculty/londondeanery.ac.uk/e-learning/setting-learning-objectives/some-theory (Assessed 15.5.2018)

From the WPBA, it is the objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) assessment, that will “show how” well the trainee is performing and, at this pyramid level is where the simulation plays a decisive role. There were considered two components to estimate the efficiency of simulation: Learning Curve - relating to mastering specific task and Transfer Validity relates to the level in which simulation- attained skills are applied clinically. (Sturm LP et al, 2008). All of the above improvements have been designed to improve patients’ safety during an adequate healthcare.

Literature Review

A literature review was performed to analyse the use of simulation in gynaecology practice. A systematic computerised search using the terms “gynaecological emergencies simulation” and “simulation in gynaecology”, between 2009 - 2018. The relevant data bases used were Ovid, Wiley Online Library / Cochrane Library and British Medical Journey and UpToDate. The search engines used were universities iCat Library Search, Medline, Google Scholar search. Relevant websites of RCOG and Department of Health UK provided certain evidences. All articles were included in order to ensure the most updated information was used. Evidence shows that simulation was there since 2000 BC, in Egypt, where the surgeons priest may have simulated a series of surgical procedures - such as rhinoplasty, on the cadavers that were prepared for mummification process (Hawass, 2002).

It has taken a very long time till 1700, when father and son Dr Gregoire de Paris, used a human pelvis with skin stretched across it and a dead foetus to explain the assisted complicated deliveries. In this way their method become the first recorded use of a medical simulator (Buck, 1991). After few decades later, a French midwife created dolls that helped teaching the birth process in a safety manner (King, 2007). In 1739, Dr William Smellie will create his version of simulated delivery, in the form of a very realistic human pelvis with ligaments, muscles, skin, using turned upside down carafe as a womb and cloth dolls. By the 1747 he produced 3 machines with 6 artificial children (Blackwell, 2001).

UK specialty press did not praise too much the simulation as educational tool in healthcare, neither disapprove it. It was described more as a potential solution to the decrease in junior doctors’ working hours and the subsequent reduction in their hands-on practise (Evans, 2010). In Canada, the integration of simulation into specialty programme took longer. A survey of 19 questions has been developed and distributed to 16 active obstetrics and gynaecology specialty programs in Canada. The response of 92 % of them stated they already introduced the simulation in their curriculum and 100 % had already access to a simulation suite in their premises.

The overall conclusion was the need of a standardized simulation curriculum to be introduces in the obstetrics and gynaecology specialty programme in Canada (Sanders, 2015).

A year later, in the UK, has been published a cross -sectional survey, with the aim of exploring laparoscopic simulation training and the attitude of trainers and trainee to the role of simulators in surgical training (Burden, 2016). Their data revealed an inconsistency in the use of laparoscopic simulators, with limited use of compulsory curricula, but in contrast both the trainees and the trainers identify the necessity for better use of laparoscopic simulation for surgical training. Regarding the simulation training in obstetrics and gynecology, across Australia and New Zealand, a survey was circulated to identify any specific issues and how these can be addressed.

The findings were surprising, as even with simulator accessibility, only few trainees benefit from it as a part of the curricula and this should be more largely supported with appropriate curriculum and teaching sessions (Wilson, 2016). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG) planned a series of obstetric situations appropriate to simulation training. They noticed that teamwork and communication failures stand up for 70 percent of sentinel events in obstetrics. Multi-layered strategies to improve the global safety environment embrace the use of clinical protocols, guidelines, and checklists (Ennen, 2017).

The role simulation plays, it can be clearly observed in obstetrics and gynaecology. The obstetrics emergencies are mandatory throughout the Deaneries programmes, being present as regional training days, update courses, or as induction days for the newly starters in the obstetric field. The literature search did not show any mentions about emergency gynaecological only. There is a gap in this area and there is place for improvement. It is reasonable to assess the emergency gynaecological simulation need and provide the trainees with appropriate support from curricula.

Materials and Methods

A local survey has been carried out in 2 phases, as pre - simulation and post-simulation. The post-simulation test consisted from a questionnaire comparing the pre-simulation vs post-simulation experience, knowledge and level of confidence (Appendix 3). The pre-simulation survey had 1 questionnaire with two sections, one with the general background of the persons involved (Appendix 1) and the second one with specific gynaecological emergencies (Appendix 2).

All questionnaires have been delivered by hand to each participant and collected later same day. This had the advantage of being in direct contact with potential contributor that might in turn persuade a larger percentage of individuals to complete the questionnaire. The questionnaires were based on Likert - type scale, a scaling technique in which respondents are asked to order or rank the answers with respect to a specific characteristic (Likert, 1932). It is worth mentioning that the benefits of this approach are: can target vast number of people, low cost and time efficient, fast and easy way to get information, analysis can be straight, low pressure on responders and lack of interviewer bias.

The disadvantages are: the scale is uni - dimensional, giving only few option of choice, therefore failing to measure the true attitude, it is more likely people to be influenced by the previous questions, also people avoid choosing the extremes, potentially from negative implications (LaMarca, 2011).

Scenario Setup

With regards to the scenario setup environment, the trainee will be presented to the essential materials and resources that will be used throughout simulation. Also, they should be informed how to request information and details about the patient’s physical findings and the laboratory or imagistic results, how to perform calls or call for help. Providing a systematic approach, will enable the participants to immerge into the virtual reality scenario, minimizing unpredicted disruptions.

Scenario Conduction

Organizing a simulation with trainees can be a very complex mission. There is no sole great technique to deal with this task. There are multiple factors that will help the trainer how to guide the scenarios, such as a decision when to continue or to stop an intervention, when to change the treatment pathway or even forcing a patient to have a cardiac arrest. If using manikins in simulation process, all possible pre - set scenarios should be designed using flowcharts, for the ease of the scenario. All of these decisions should take in the consideration the learning points and the trainee’s training (Pazzin, 2007)

Scenario Debriefing

Debriefing is done at the end of the simulation sitting, being one if the most important aspect. It is a reflective thinking process, where both the trainee and the trainer are discussing the trainees’ actions in the simulation exercise (Cho, 2015). The trainer should act as a facilitator, promoting a nonthreatening environment, allowing the trainee active involvement, using open-ended questions and positive feedback. The trainee should be guided through the simulation exercise, enable him or her to analyse, synthetize and appraise their knowledge with the aim to apply the experience in forthcoming instances (Fanning, 2007). Debriefing helps the trainees to learn from their mistakes, this being one if the advantage of the simulation. Debriefing has been used successfully after real clinical situations, being applied in various specialties as obstetrics (Cho, 2015), resuscitation (Couper, 2013) and critical care (Clay, 2007).

Sample and Scope

During the induction process, at the beginning of a new position or starting a rotation in a new specialty, every doctor should have a simulation for an emergency clinical situation. This is happening successfully in obstetrics, but not in gynaecology spectre. A well - planned induction is aiming for the new doctor to become familiar with the new working environment, in order their work to be efficient in providing excellent care to the patient (The British Medical Association - BMA - 2018). In order to have the best representation possible over the Trust, in the survey have been included all the junior doctors working at that time in the gynaecological department. A total of 15 junior doctors, comprising Trust Senior House Officer (SHO), Specialty Trainee Year 1 (ST1) and Year 2 (ST2), Foundation Year 2 (FY2) and General Practitioner Specialty Trainee (GPST).

Data Collection

The survey was based on the pre-simulation and post - simulation surveys. The data was collected over a four - month period - a typical rotation for most of the doctors, between December 2017 - March 2018.In the pre-simulation phase, each doctor received 1 questionnaire with 2 sections, based on Likert-type scale (Likert, 1932), which they were asked to fill in and return the same day. In the second phase, after the simulation, a post-simulation questionnaire was given comparing the pre-simulation vs post-simulation experience, knowledge and level of confidence. All this process coincides with teaching season, in which all the junior doctors need to take part regularly over their rotation period. All the data were anonymised and secured to the NHS Trust premises (Data Protection Act, 1998).

Data collection was done using questionnaires with open and closed questions, assessing the experience, level of knowledge and confidence in dealing with the most common gynaecological emergencies. The simulation process entailed the participation in a small group scenarios. The scenarios themes were designed accordingly with the areas from the acute gynaecological emergencies, where the candidates did not feel confident at. The aim of scenarios was to simulate a real-life case of acute gynaecology simulations, where the situation may aggravate quickly, without notice, forcing the participants to chance their attitude towards stabilisation of the patient (Jones, 2015).

Data Analysis

All the data was secured on the NHS computers, under password and encrypted system. Data were analysed using excel spreadsheets. Data were separated into different categories, such as professional characteristics, experience, confidence level, supervision level. All of these methodical results were aiming to provide accurate recommendations for future practice. As Likert scale is symmetric and equidistant, behaving as ordinal, It may be represented in a binomial form by summing agree and disagree responses separately. For this reason, non-parametric tests can be used, such as Chi - squared test or Mann - Whitney test. These tests may be use for a larger sample. For the small sample presented here, visual representation included tables and bar charts.

Ethical Consideration

- As this project was not an audit, but mainly a survey tool to analyse the training need, did not need to follow the specific steps of the audit pattern. However, in order to present the findings to the clinical team, was registered within the clinical effective and assurance committee.

- There was no ethical permission required, as no patients’ details were needed, according to NHS Health Research Authority.

- Data was used and stored according to the data protection act (1998) on password protected trust computers, the anonymity of individuals maintained

Results

A total of 100 % (n = 15 / 15) of questionnaires have been completed. These included 23,33 % (n = 5) obstetrics and gynaecology specialty trainees and 66,66 % (n = 10) GPST and Trust grades. All the completed forms were introduced into excel spreadsheet for analysing and producing the relevant graphs.

Discussion

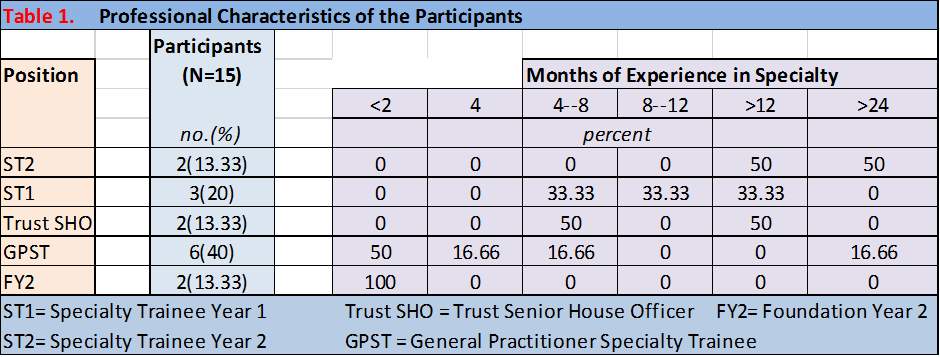

From all the participants, ST2 were 13,33 % (n = 2), ST1 20 % (n = 3), Trust SHO 13,33 % (n = 2), GPST 40 % (n = 6) and FY2 13,33 % (n = 2). Diagrams as per table 1.

Table 1.

In the next paragraphs will present the findings from the pre – simulation survey. Respecting the order of the questions, from the first questionnaire (Appendix 1), the following have been concluded:

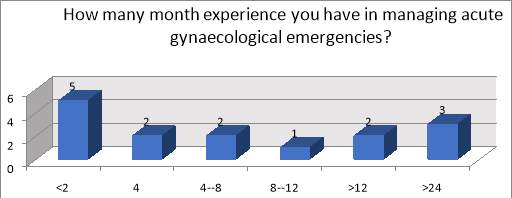

Question 1: “How many months experience you have in managing acute gynaecological emergencies?”

Findings: 33,33 % (n = 5) had months experience; 20 % (n = 3) had > 24 months; 13,33 % (n = 2) had > 12 months; 13,33 % (n = 2) had 4 months; 13,33 % (n = 2) had between 4 - 8 months and 6,66 % (n = 1) had between 8 – 12 months. Diagrams as per figure 2.

Figure 2.

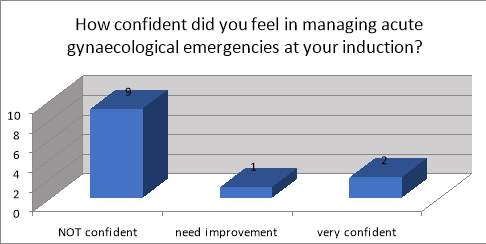

Question 2: “How confident did you feel in managing acute gynaecological emergencies at your induction?”

Findings: At induction, 60 % (n = 9) felt not confident to manage the emergencies, 6,66 % (n = 1) needed improvement and 13,33 % (n = 2) were very confident in managing the acute gynaecological emergencies. Diagrams as per figure 3.

Figure 3.

Question 3: “Did induction cover acute gynaecological emergencies?”

Findings: 100 % (n = 15) did not have covered at the induction the acute gynaecological emergencies.

Question 4: “Did you have any skills drill for acute gynaecological emergencies?”

Findings: 100 % (n = 15) did not have any skills drill for acute gynaecological emergencies.

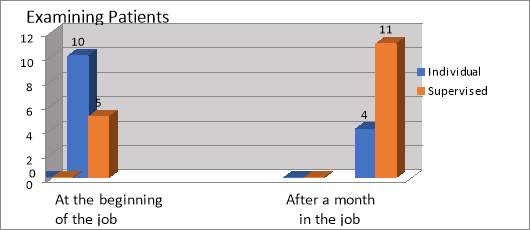

Question 5:” At the beginning of the job, did you examine patients by your own or supervised? “ has been compared with Question 6: “After a month in the job, do you feel confided to manage the acute gynaecological emergencies by your own or still need supervision? “

Findings: 66,66 % (n = 10) vs 26,66 % (n = 4) examined the patient individual at the beginning of the job comparing after a month in the job. 33,33 % (n = 5) vs 73,33 % (n = 11) required supervision at the beginning of the job comparing after a month in the job. Diagrams as per figure 4.

Figure 4.

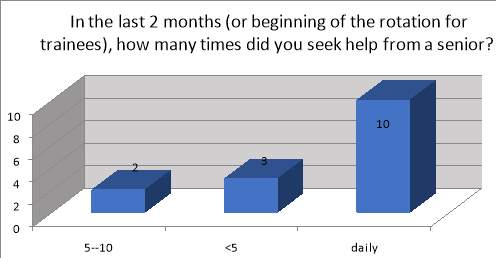

Question 7: “In the last 2 months (or beginning of the rotation for trainees), how many times did you seek help from a senior?”

Findings: In the last 2 months 66,66 % (n = 10) asked daily for senior help, 20 % (n = 3)

Figure 5.

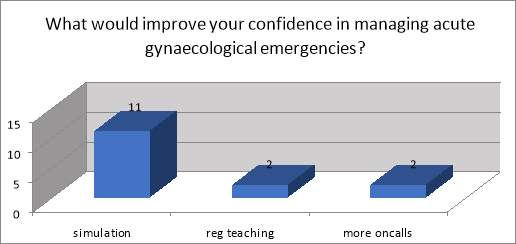

Question 8: “What would improve your confidence in managing acute gynaecological emergencies?”

Findings: 73,33 % (n = 11) thought that simulation will improve their confidence; 13,33 % (n = 2) regional teaching will help and 13,33 % (n = 2) thought doing more gynaecology oncalls will improve their confidence in managing acute gynaecological emergencies. Diagrams as per figure 6.

Figure 6.

Question 9:” Do you believe a skill drill for acute gynaecological emergencies will improve your practice?”

Findings: 100 % (n = 15) did believe a skill drill for acute gynaecological emergencies will improve their practice. The following have been concluded from the pre – simulation survey, from the second questionnaire. The second questionnaire from the pre - simulation survey included only three options of answer: not confident, need improvement and very confident. The questions referred to the most important acute gynaecological emergencies, according to the curriculum. They have been categorised into eight groups, each of them with subgroups (Appendix 2):

- General Gynaecology comprising team working, basic life support (BLS), advanced life support (ALS) and sepsis;

- Early Pregnancy covering miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, molar pregnancy, septic abortion, hyperemesis gravidarum and vomiting in pregnancy (HGVP), cervical incompetency and emergency cerclage (CIEC);

- Acute and Chronic Abdominal Pain including acute abdominal pain (ectopic, miscarriage, ovarian cysts / fibroid torsion, pelvic inflammatory disease) and chronic abdominal pain (pelvic infection, endometriosis, tumour);

- Intra – Operative Emergencies containing haemorrhage, perforated uterus and damage to urinary tract / blood vessels / bowel;

- Post – Operative Complications including collapse, chest pain, abdominal distension, pyrexia, oliguria and anuria, post LLETZ (large loop excision of transformation zone of the cervix);

- Contraception and Termination of Pregnancy (TOP) covering unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI) and emergency contraception (EC), TOP complications;

- Miscellaneous with sexual assaults and urinary retention;

- Communications Skills including the following Counselling about amniocentesis (ACS) and chorionic villus sample (CVS); Counselling about miscarriage, ectopic and molar pregnancy, TOP; Counselling about newly diagnosed tumour; Consent for surgical procedures – surgical management of miscarriage (SMM), medical management of miscarriage (MMM), ectopic, salpingo - opphorectomy, diagnostic laparoscopy, laparotomy, total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH), early menopause.

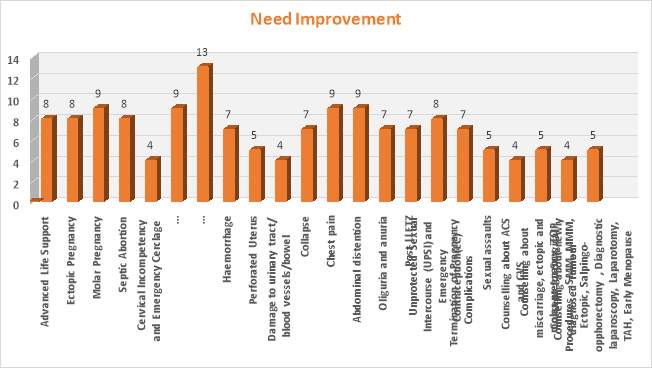

Findings: The majority of the participants answered in the section of “Need Improvement” for the most of the acute gynaecological emergencies, as per diagram in Figure 7.:

- 86,66 % (n = 13) - Chronic Abdominal Pain -pelvic infection/endometriosis/tumour

- 60 % (n = 9) - Molar Pregnancy, Abdominal distention, Acute Abdominal Pain – ectopic/miscarriage/ovarian cyst/fibroid torsion, PID, Chest pain

- 53,33 % (n = 8) - ALS, Ectopic Pregnancy, Septic Abortion, UPSI and EC

- 46,66 % (n = 7) - Haemorrhage, Collapse, Oliguria and anuria, Post LLETZ, TOP Complications

- 33,33 % (n = 5) - Perforated Uterus, Sexual assaults, Counselling about miscarriage, ectopic and molar pregnancy, TOP, Consent for Surgical Procedures – SMM, MMM, Ectopic, Salpingo-opphorectomy, Diagnostic laparoscopy, Laparotomy, TAH, Early Menopause

- 26,66 % (n = 4) - CIEC, Damage to urinary tract/ blood vessels/bowel, Counselling about ACS and CVS, Counselling about newly diagnosed Tumour

Figure 7.

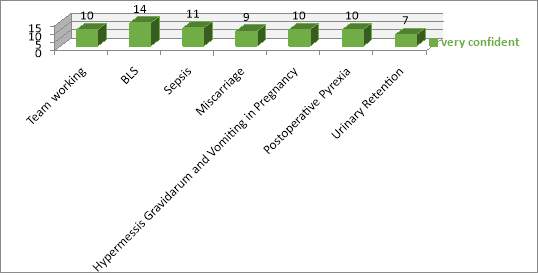

The percentages of the participants answering that they were “Very Confident “are detailed below, as per diagram in Figure 8.:

- 93,33 % (n = 14) - BLS

- 73,33 % (n = 11) - sepsis

- 66,66 % (n = 10) - team working, post – operative pyrexia, HGVP

- 60 % (n = 9) - miscarriage

- 46,66 % (n = 7) - urinary retention

Figure 8.

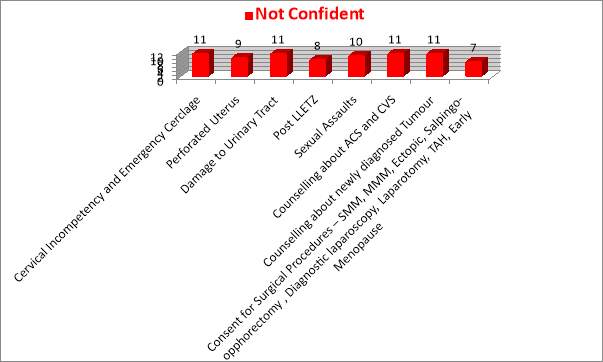

The percentages of the participants answering that they were “Not Confident “are detailed below, as per diagram in Figure 9.:

- 73,33 % (n = 11) – sepsis, CIEC, Damage to urinary tract, counselling about ACS and CVS, Counselling about newly diagnosed tumour

- 66,66 % (n = 10) – sexual assault

- 60 % (n = 9) – perforated uterus

- 53,33 % ( n = 8) – post LLETZ

- 46,66 % (n = 7) - Consent for Surgical Procedures – SMM, MMM, Ectopic, Salpingo-opphorectomy, Diagnostic laparoscopy, Laparotomy, TAH, Early Menopause

Figure 9.

In the next passages will extend the findings from the post - simulation survey. Following the order of the questions (Appendix 3), the results are shown below:

Question 1: “Do you feel this simulation scenario will impact positively on your practice?”

Findings: 100 % (n = 15) felt this simulation scenario will definitely impact positively on their practice.

Question 2: “Do you feel this simulation scenario will positively impact on your teamwork?”

Findings: 100 % (n = 15) felt this simulation scenario will definitely impact positively on their teamwork.

Question 3: “Do you feel this simulation scenario will improve your communications skills?”

Findings: 100 % (n = 15) felt this simulation scenario will definitely improve their communication skills.

Question 4: “Do you feel this simulation scenario has improved your assessment skills?”

Findings: 100 % (n = 15) felt this simulation scenario definitely improved their assessment skills.

Question 5: “Has this simulation scenario helped you improve on a specific topic?”

Findings: 100 % (n = 15) felt this simulation scenario definitely helped them improve on a specific topic.

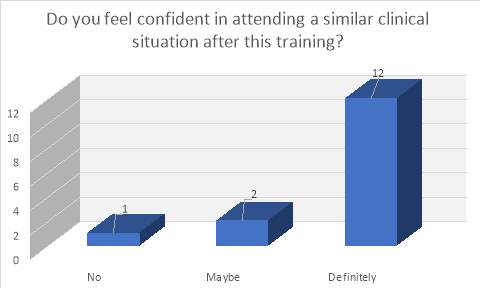

Question 6: “Do you feel confident in attending a similar clinical situation after this training?”

Findings: 80 % (n = 12) answered “definitely” in feeling confident in attending a similar clinical scenario, 13,33% (n = 2) answered “maybe” and 6,66% ( n = 1)answered “no”. Diagrams as per Figure 10.

Figure 10.

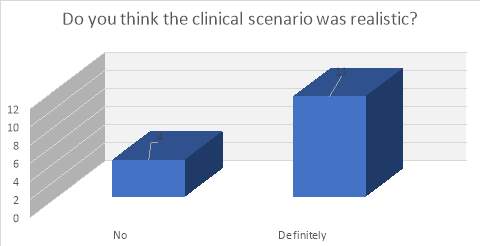

Question 7: “Do you think the clinical scenario was realistic?”

Findings: 73,33 % (n = 11) who answered “definitely”, thought the clinical scenario was realistic, 26,66 % (n = 4) thought the clinical scenario was “not” realistic and improvements need to be done. Diagrams as per Figure 11.

Figure 11.

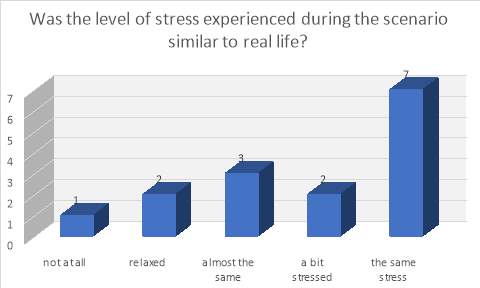

Question 8: “Was the level of stress experienced during the scenario similar to real life?”

Findings: 46,66 % (n = 7) felt was “the same stress “to real life, 20 % (n = 3) felt “almost the same” stress; 13,33% (n = 2) felt “relaxed”; 13,33% (n = 2) felt “a bit stressed” and 6,66% ( n = 1) felt no stress at all. Diagrams as per Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Limitations

This training needs analysis was done on a relatively small sample, only 15 persons involved. After achieving promising results, the aim is to involve in the survey the rest of the Trusts from the same Deanery. This will make the sample bigger and the results more reliable.

Future recommendations

From the completed survey questionnaires, it has been highlighted the need of junior doctors for improvement the management of the acute gynaecological emergencies. There were reported a series of aspects of the acute gynaecological emergencies, where the junior doctors felt not confident in dealing with them. Also, there was reported the need of supervision in most of the emergency situations. For these reasons, the future recommendations seem appropriate:

- Increase the sample, by inviting in the study all the teaching trust hospitals and making the study strength more robust

- Introducing clinical scenarios for the topics the participants were not confident and needed improvement

- Introducing acute gynaecological emergencies simulation drill as a regional training day for specialty trainees

- Introducing acute gynaecological emergencies simulation drill mandatory at induction for all junior doctors

Conclusions

Although, at the beginning of the job, the majority of the participants felt very confident, after one month the numbers reversed, due to lack of confidence, with the majority of them seeking for senior help daily. In 1999, the United Sates (U.S.) Institute of Medicine raised concerns regarding patients’ safety.” The Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System” report aimed to increase awareness of U.S. medical errors. U.S started to improve the patient quality of care and safety medical practice by changing how the healthcare professional are trained (Linda, 1999).

Simulation is offering a safe and controlled location. Simulation can be tailor - made to train the technical and non-technical skills and the attitudes. Simulation helps the trainee to improves the teamwork, communications and to develop the clinical leadership. Simulation is a reliable teaching assessment technique through OSCE. In UK, it is considered as good medical practice to acquire training in technical skills in a simulation setting, before applying these skills on real patients.

In gynaecology, the trainee can use the simulation for improving the non-technical skills, like consent, multi-disciplinary team involvement or early pregnancy loss issues. The trainees following an acute surgical or medical specialty, are expected to progress towards clinical independence in these procedures. If this is not possible, one or more of the next are adequate: “skills lab competent with certification, course competent with certification, some clinical experience with Directly Observed Procedural Skills (DOPS) indicating, at a minimum, ‘able to perform the procedure under direct supervision / assistance’” (NHS Health Education England, 2016).

The simulation-based education (SBE) should be affiliated to the appropriate educational curriculum, up - to - date by the evidence base and follow to the highest quality standards. To benefit a maximum quality effect, there should be consistent occasions for SBE during doctors’ careers.

References

Annual Review 2014/15 & Forward Look for 2015/18., NHS Litigation Authority, [Online] Available at: http://www.nhsla.com/AboutUs/Documents/NHS%20LA%20Annual%20Review%202014%20-15%20and%20Forward%20Look%202015-18.pdf (Accessed 12.06.2018)

Black HD. The quality of assessment in further education in Scotland, In: Harlen W, editor, Enhancing quality in assessment, London: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd; 1994

Blackwell, B., "Tristram Shandy" and the Theatre of the Mechanical Mother, ELH. 68, 81-133; 2001

Broadfoot P., Editorial: Assessment in education; 1994; 1:3–10

Buck GH., Development of simulators in medical education, Gesnerus 1991;48 Pt 1:7-28

Burden C. et al, Laparoscopic simulation training in gynaecology: Current provision and staff attitudes – a cross-sectional survey, Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 36(2):234-40; 2016

Cho SJ. Debriefing in paediatrics. Korean J Paediatrics. 2015;58(2):47–51

Clay AS, Que L, Petrusa ER, Sebastian M, Govert J. Debriefing in the intensive care unit: a feedback tool to facilitate bedside teaching. Critical Care Medicine. 2007;35(3):738–54

Couper K, Perkins GD. Debriefing after resuscitation. Current Opinion Critical Care. 2013;19(3):188–94 [Online] Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23426138 (Accessed 18.07.2018)

Critical Care Unit opens a new Simulation Suite thanks to fundraising efforts by Nottinghamshire mum in memory of her daughter, Westbridgfordwire, [Online] Available at: https://westbridgfordwire.com/critical-care-unit-opens-new-simulation-suite-thanks-fundraising-efforts-nottinghamshire-mum-memory-daughter/ (Accessed 12.06.2018)

Crouch, Tom D., The Bishop's Boys: A Life of Wilbur and Orville Wright; 1989

Data Protection Act 1998, Legislation Gov UK, [Online] Available at: http://www. Legislation.gov. uk/ukpga/1998/29/contents (Accessed 4/5/2018)

Department of Health. Confidentiality. NHS Code of Practice, [Online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/ government/ uploads/system/uploads/ attachment_data/ file/ 200146/Confidentiality_-_NHS_Code_of_ Practice.pdf (Accessed 6/6/2018)

E-Learning - Miller’s pyramid, [Online] Available at: http://www.faculty/londondeanery.ac.uk/e-learning/setting-learning-objectives/some-theory (Accessed 12.6.2018)

Enhancing UK Core Medical Training through simulation-based education: an evidence-based approach, NHS Health Education England, October 2016, [Online] Available at: https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/sites/default/files/HEE_Report_FINAL.pdf (Accessed 19.07.2018)

Ennen CS et all, Reducing adverse obstetrical outcomes through safety sciences. UpToDate. August 21,2017. [Online] Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/reducing-adverse-obstetrical-outcomes-through safetysciences?search=simulation%20in%20gynaecology&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H6 (Assessed 28.05.2018)

Evans E et al, Simulation in obstetrics and gynaecology, Obstetrics Gynecology & Reproductive Medicine, 20(8):253-254; August 2010

Fanning RM, Gaba DM. The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simul Healthcare 2007;2(2):115–25 First Aircraft Simulator, Kavkar, [Online] Available at: https://www.havkar.com/en/blog/view/first-aircraft-simulator/90 (Accessed 15.6.2018)

General Medical Council. Good Medical Practice, London: General Medical Council; 2001 General Medical Council, Promoting excellence: standards for medical education and training. London: GMC; 2016. General Medical Council, Theme 5: Developing and implementing curricula and assessments, London: GMC; 2016.

Hawass ZA, Hidden treasures of the Egyptian Museum: one hundred masterpieces from the centennial exhibition, Photographs by Kenneth Garrett, Introduction by Farouk Hosni, Cairo: American University in Cairo Press; 2002. 82 p

Impact of an open-chest extracorporeal membrane oxygenation model for in situ simulated team training: A pilot study - Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. [Online] Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/Questionnaire-for-self-evaluation-1-not-at-all-no-impact-and-5-a-lot-high-impact_fig3_258054952 (Accessed 24 Jun, 2018)

Induction for junior doctors-10.04. 2018.British Medical Association, [Online] Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice/employment/contracts/juniors-contracts/induction-and-shadowing/induction (Accessed 12.06.2018)

Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ, Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review, Med Teach.; 2005; 27:10-28. Review

Ivette Motola, Luke A. Devine, Hyun Soo Chung, John E. Sullivan & S. Barry Issenberg, Simulation in healthcare education: A best evidence practical guide. AMEE Guide No. 82, Medical Teacher, 35:10, e1511-e1530; 2013

Jones et al. Simulation in Medical Education: Brief history and methodology. Principles and Practice of Clinical Research. Jul-Aug, 2015 / vol.2, n.1, p.56-63

King, H, Midwifery, obstetrics and the rise of gynaecology: the uses of a sixteenth-century compendium, Aldershot, Hants, Ashgate Pub;2007

LaMarca N, The Likert Scale: Advantages and Disadvantages, Field Research in Organizational Psychology;2011. [Online] Available at: https://psyc450.wordpress.com/2011/12/05/the-likert-scale-advantages-and-disadvantages/ (Assessed 07.06.2018)

Likert, R., A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes. Archives of Psychology; 1932; 140, 1–55

Linda T. Kohn, Janet M. Corrigan, and Molla S. Donaldson, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (November 1999), The National Academies Press, [Online] Available at: https://www.nap.edu/read/9728/chapter/1 (Assessed 15/07/2018)

McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Petrusa ER, Scalese RJ.; 2010a, A critical review of simulation-based medical education research: 2003–2009, Med Educ ,44:50–6

National Institute of Clinical Excellence, Principles for best practice in clinical audit 2002, Radcliffe Medical Press, Oxford National Quality Board. Quality Governance in the NHS National Quality Board – A guide for provider boards. [Online] Available at: Https://www.gov.uk/ government/uploads/system/upload/ attachment_ data/file/216321/dh_125239.pdf (Accessed 21/ 4/2018)

NHS Health Research Authority. Defining Research. Research Ethics Service guidance to help you decide if your project requires review by a Research Ethics Committee. [Online] Available at: http:// www. hra.nhs.uk/documents/2016/06/defining-research.pdf (Accessed 2/5/2018)

NHS Litigation Authority Report and accounts 2013/14. [Online] Available at: http://www.nhsla.com/AboutUs/Documents/NHS%20LA%20Annual%20Report%20and%20Accounts%202013-14.pdf (Accessed 12.06.2018)

Pazin Filho A, Romano MMD. Simulacao: Aspectos conceituais. Rev Fac Med Ribeirao Preto. 2007;40(2):167–70

Sanders A, Wilson Douglas R, Simulation Training in Obstetrics and Gynaecology residency Programs in Canada, Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 37(11):1025-1032; November 2015

Sturm LP et al., A systematic review of skills transfer after surgical simulation training, Ann Surg.; 2008.

Sutherland et al., Surgical simulation: a systematic review. Ann Surg.; 2006

Wilson E, et all, Simulation training in obstetrics and gynaecology: What's happening on the frontline? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology ;2016, [Online] Available at: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ajo.12482 (Accessed 10.6.2018)

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Medicine"

The area of Medicine focuses on the healing of patients, including diagnosing and treating them, as well as the prevention of disease. Medicine is an essential science, looking to combat health issues and improve overall well-being.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: