Dissertation on Cultural Conflict in Sino-Indian Employment

Info: 24605 words (98 pages) Dissertation

Published: 15th Nov 2021

ABSTRACT

In today’s global economy, when any corporation expands abroad it usually brings with it the management practices that are deep-rooted in its national culture and management theory. Studies have indicated that often these management practices do not work well in foreign locations, might even undermine an organization’s effectiveness and productivity at the new sites.

In past few years a lot of Chinese companies have invested in India, likewise, a lot of Indian companies have been operating in China. However, cross-cultural differences between these two countries could be a barrier in efficiently managing the organization in the host country.

The purpose of this research is to understand Sino-Indian culture-related theories as per Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and other measures of culture that lead to work-family conflict in a Sino-Indian cross-cultural work setting. The methodology used for this research was qualitative method, in-depth face to face interviews were conducted and follow-up forms were given to the local Indian employees in a Chinese company in India and to local Chinese employees in an Indian company in China. The number of respondents was fifteen in each company. Respondents belonged to low to mid-level management. Interview responses were qualitatively analyzed using codes and themes.

Findings reveal that the differences between employees’ cultural values and company’s culture do exist which lead to work-family conflict in the lives of their employees. This study proposes that cultural dimensions of a country such as individualism/collectivism, power-distance, humane-orientation, and specificity/diffusion create a difference in the work values of an employee. These basic differences in the work values of an employee and the management of a foreign company lead to the work-family conflict in a cross-cultural setting.

This research supports the fact that instead of following long-established ways of managing local workforces in a foreign country, the organizations can benefit from adjusting to local national culture and work values attached to that country.

Keywords: Cross-cultural settings, Work-family conflict, Sino-Indian cultural dimensions

Click to expand Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Chapter I Introduction

1.1 Background

1.2 Research Stimuli

1.3 Aim

1.4 Research Structure

Chapter II Literature Review

2.1 Definition of Culture

2.2 Workplace diversity

2.2.1 Areas of differences in a workplace

2.2.2 Advantages of diversity

2.3 Hofstede’s Culture Dimensions

2.3.1 Power Distance

2.3.2 Individualism

2.3.3 Masculinity

2.3.4 Uncertainty Avoidance

2.3.5 Long-Term Orientation

2.3.6 Indulgence

2.4 Similarities and Differences between India and China

2.5 Other Measure of Culture

2.5.1 Humane orientation

2.5.2 Gender egalitarianism

2.5.3 Specificity/diffusion

2.6 Work-Family Conflict

2.6.1 Work-to-family conflict

2.6.2 Family-to-work conflict

2.7 Outcomes of Work-Family Conflict

Chapter III Research Model

3.1 The Role of Culture in Studying WFC

3.2 Culture as the Main Effect Influencing WFC

3.3 Culture, WFC, and Consequences

3.4 Sino-Indian Cultural factors leading to WFC

3.4.1 Individualism/ Collectivism

3.4.2 Humane orientation

3.4.3 Specificity versus diffusion

3.4.4 Gender-Egalitarianism

3.5 General Framework

3.6 Research Questions

Chapter IV Methodology

4.1 Sampling

4.2 Data Collection

4.3 Data Analysis

Chapter V Results and Findings

5.1 Existence of Sino-Indian cultural differences in the cross-cultural workplace

5.2 Cross- cultural reasons of WFC in both the societies

5.2.1 Individualism/ Collectivism and WFC

5.2.2 Power Distance and WFC

5.2.3 Specificity/Diffusion and WFC

5.2.4 Humane Orientation and WFC

Other differences

5.3 Level of WFC in a cross-cultural setting

5.3.1 WIF or FIW

5.3.2 Types of conflicts

5.4 Additional Findings

Chapter VI Discussion

6.1 Theoretical Implications

6.2 Practical Implications

6.3 Limitations

Appendix 1

Interview Questions

Appendix 2

Follow-up form:

References

Chapter I Introduction

1.1 Background

It is a well-known fact that the world is becoming globalized, most of the companies have been investing in almost every part of the world to make their business international and more profitable. Organizations are no longer constrained by national borders. Differences exist among people from different countries in terms of their lifestyle, values, perspectives, preferences etc. (Robbins and Judge 2013, p. 16).

Globalization has its positive as well as negative aspects. It has expanded capacity, and advances in technology have made organizations be prompt and flexible in order for them to survive. The result is that most managers and employees today work in a climate that can be called as “temporary”. Increased foreign assignments mean they will have to manage a workforce which is very different in needs, aspirations, and attitudes as compared to those used in their own country[i] (Robbins and Judge 2013, p. 17).

When working with people from different cultures, even in someone’s own country, people find themselves working with supervisors, peers, and other employees born and raised in different cultures with different values. What motivates one employee may not motivate the others, or someone’s communication style may be straightforward and open, which others may find uncomfortable and threatening. To work effectively with people from different cultures, a person needs to understand how their culture, geography, religion have shaped them and how to adapt their management style to their differences. Management practices need to be modified to reflect the values of the different countries in which an organization operates (Robbins and Judge 2013, p. 20).

Due to social trends, managing the work-family balance has become a challenging task for employees in almost every nation. Working in a multi-national company requires time, energy and commitment that may not let people satisfy their family and life needs (Powell, Francesco and Ling 2009).

In the recent few years, following this trend of going global, a lot of Chinese companies are investing in Indian market due to the high market potential. In the year 2015, Chinese companies invested $870 Million in India, as reported in an interview of the President of India (Mukherjee 2016)

Most of the companies prefer sending their own experienced employees initially to establish the base, to hire and train local people as per the company culture. Even though China and India are Asian countries but significant cultural differences prevail amongst both the countries.

Since the cultural differences exist between Chinese supervisors and Indian employees in a Chinese company functioning in India, it could be assumed that due to various cultural differences some of the employees would not be able to perform efficiently and effectively as per the expectations of Chinese managers which might lead to Work-Family Conflict (WFC) in Indian employees’ lives. There is a probability that cultural differences in the workplace can affect the employees in one way or the other which would, in turn, affect the overall performance of the company. There also have been studies before about work-family conflict leading to negative psychological impact on a person’s life.

There have been theories also on the fact that the societal or culture of a nation, is likely to form individuals’ experiences of the work-family setting, but generally, it is not recognized in theories and researches on work-family literature. Cultural norms, societal values, and relationship between work-family tend to affect the experience of an individual in these domains. The common notion of culture is that it is deep-rooted group difference in cognitive, attitude, and behavior pattern. Cultural differences are considered to have an important role in understanding employee satisfaction and commitment in context to work-life balance practices.

In one of the pre-existing studies related to the work-life conflict in countries like India, Peru, and Spain, it was found that employees from India experienced higher levels of the conflict. WFC is believed to be two-way phenomena: how work affects employees’ personal lives and how their personal lives affect their work performance. The way in which a person chooses to deal with such kind of conflict varies as per the nationality and culture of that person (Hofstede 2001).

Nowadays, employees complain increasingly that the line between work and non-work time has become blurred, creating personal conflicts and stress. At the same time, today’s workplace gives opportunities for workers to create and structure their own roles. The conception of global organizations means that the world never sleeps. At any time on any day, thousands of employees are working somewhere in the world. The necessity to consult with colleagues or customers eight or ten time zones away means many employees of global firms are at work for twenty-four hours a day. Communication technology helps many technical and professional employees to do their work at home, or in their cars but it also means many employees feel like they never really get away from the office and are working even when at home with family.

Organizations now ask employees to work longer hours than usual. The rise of dual-career couples makes it complicated for married employees to find time to fulfill their commitments towards home, spouse, children, parents and friends. Many of the single-parent households and employees with parents dependent on them have even more considerable challenges in balancing work and family responsibilities.

Employees gradually recognize that work infringes more on their personal lives. Recent research also suggested that employees look for jobs that give them more flexibility in their work schedules so they can better manage their work-life balance. In fact, now balancing work and life demands generally surpasses job security as an employee’s priority. The next generation of employees is likely to show similar apprehensions. In the related studies, it has been found out that most of the university students stated attaining a balance between personal life and work is a primary career goal; they want a better personal life as well as a good professional life as compared to the previous generations. Organizations that do not help their employees to achieve work-life balance will find it increasingly difficult to attract and retain the most capable and motivated employees (Robbins and Judge 2013, p. 21)

WFC has been shown to influence the organizational outcomes like job satisfaction, job performance, creativity, organizational commitment, employee turnover etc. It is also among top three reasons for stress in India (Press Trust of India 2014).

Most common practices in culturally intelligent firms in western countries to overcome such a conflict are telecommuting, flexible timings, compressed work week, reduced work hours, job sharing, paid vacations, parental leaves, paid family and medical leaves.

1.2 Research Stimuli

Many scholars have agreed that attitudes of the employees towards work are an important aspect of the workplace and could lead to higher productivity levels on both individuals as well as organizational level. Also, their cultural background may affect their attitudes toward work to a great extent (Noe, Hollenberck and Gerhart 2000). There not many studies about how culture affects work-related activities in a country. Values even lead to the differences in approach towards work in certain national cultures (Peters 2000).

Cultures within organizations are found to differ, to some extent cultures differ within one nation, but they vary even more when it comes to different nations.

Nowadays organizations do not focus on the fact that in order to work effectively and efficiently with people from different cultures, they still need to understand how their culture, geography, religion have shaped them and how to adapt your management style to their differences. A misfit of cultures is often mentioned as a reason for the failure for multi-national organizations (Cartwright 1993, 1996;Olie 1994).

Management practices need to be modified to reflect the values of the different countries in which an organization operates. As proposed by Trompenaars and Hampden-Tumer (1998), good managers strive to learn to work with other cultures and try to resolve the differences resulting from cultural differences. However, it would be better if these cultural differences would first be identified and later analyzed so that they could be understood and addressed.

Chinese companies hiring Indian employees in India at the employee/staff level and likewise in Indian companies operating in China, cultural differences(such as values, norms, and behavior) between employees and managers could be an issue in a workplace which could lead to WFC and negative psychological outcomes for the employees.

Culture affects an employee’s attitudes and behaviors, providing in turn basis for developing culture-sensitive management systems that can actually improve organizational performance.

1.3 Aim

The aim of this research would be to assess if Sino-Indian cultural factors lead to WFC in the lives of employees working in an organization with values and norms different from their own, and which cultural factors lead to WFC.

Examine cultural diversity in workplace, its advantages and disadvantages.

Examine Sino-Indian cultural differences as per Hofstede’s theory relating to WFC, identify cultural factors leading to WFC in a workplace.

Examine the level and reasons of WFC in Sino-Indian cross-cultural workplace.

1.4 Research Structure

This research is divided into a literature review, research model, methodology, findings, and conclusion. The literature review provides the basis for exploration into the aim of this study. There is an outline of the previous studies that speak about cultural diversity, its advantages and disadvantages in a workplace, followed by existing literature on Geert Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and other dimensions of culture. The cultural differences between China and India are considered on the basis of those dimensions. There are major trends which would have been identified from previous models which help in contrast and co-relation of current issues in multi-cultural organizations functioning in another country such as Chinese companies functioning in India with Indian employee and vice versa. The end of the literature figures the factors leading to WFC and its outcomes.

The rest of the research is fragmented into research model which has a general framework of this research, in-depth study of culture related theories of WFC in previous studies. Also, a methodology which has detailed outlined of methods adopted by the researcher to investigate this study, it also speaks about the sampling methods via which the data has been collected. This is followed by findings and discussions which are an analysis of all the data collected during the process and the relevance of the data collected.

Chapter II Literature Review

2.1 Definition of Culture

Table 1, Selected Definitions of Culture

| Scholar | Definition of Culture |

| Gofdstein (1983)

|

Organizations, like persons, have values, and … these values are integrated into some coherent value system… In any organization, the members generally have a set of beliefs about what is appropriate and inappropriate organizational behavior |

| (NesSmith 1995) | A learned, shared, integrated way of life |

| (G. Hofstede 1991) | The collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one organization from another |

| Lvancevich

and Matteson (2002) |

A collective phenomenon (…) learned, not inherited |

| Cooke and Rosseau (1988) | Ways of thinking, behaving and believing that members of a social unit have in common |

| (Schein 1984) | Culture controls the manager…through the automatic filters that bias the manager’s thoughts and feelings. As culture arises and gains strength, it becomes pervasive and influences everything the manager does, even his own thinking and feeling, [sic] …most of the elements that the manager views as aspects of “effective management”—setting objectives, measuring, following up, controlling, giving performance feedback and so on—are themselves culturally biased to an unknown degree in any organization…. There is no such thing as a culture-free concept of management. |

| Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner | Shared way through which people understand and interpret the world |

| (Marquardt 1993) | Discrete manner of thinking, doing and living |

From these definitions, the common notion derived is that culture refers to the deep-rooted group differences in cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral patterns.

The ability to communicate and interact well with the people belonging to different cultures is known as cultural competence. This ability varies as per a person’s own cultural views and awareness of the other cultural practices and ideas of other people, liberal attitude towards cultural differences and cross-cultural skills.

In the previous researches, many studies have acknowledged that the national culture does have an influence in some manner or the other. Such studies are classified as culture-as-referent (which offers potential insights into cultural influences on the work-family construct as they make reference to the culture construct).

Understanding differences in different values across cultures of the world help explain the behavior of employees from different countries. Hofstede’s framework can be used for assessing cultures which can help organizations to predict the behavior of employees.

Employee’s performance and satisfaction are likely to be higher if their values fit well with the organization. The person who places great importance on imagination, independence, and freedom is likely to be poorly matched with an organization that seeks conformity from its employees.

Figure 1, Factors influencing culture

Religion

Social Structure

Political Philosophy

Culture: Values + Norms

Geography and History

Economic Philosophy

Education

Source: International business: Competing in the global marketplace, by C. W. Hill, 1997, Chicago: Irwin.

The difference is a fine line in culture and personality or between values formed on the basis of cultural background and values that have low relation with culture and are only personality traits. Cultural values are rather strongly related to organizational commitment, citizenship behavior and team related attitudes than are personality scores. On the other hand, personality was more strongly related to behavioral criteria like performance, absenteeism, and turnover (Robbins and Judge 2013, p. 85).

2.2 Workplace diversity

There has been an increase in the number of mergers, joint ventures and strategic alliances which are bringing people from different cultures and types of organizations together. Workplace diversity refers to the diversity of distinction that exists among people in an organization. It was found that cross-cultural alliance and teamwork are very crucial for organizational success. However, in order for all employees to function in a dynamic way, they have to be trained to recognize their differences as assets, rather than liabilities.

It is believed that a diverse workforce usually suffers from the low trust, stress, low job satisfaction, communication difficulties and absenteeism (Alder, 1991; O’ Reilly, Caldwell & Barnett, et al., 1989; Tsui, Egan & O’ Reilly, 1992; Zenger and Lawrence, 1989). Employees that are different from their co-workers usually report feelings of discomfort and lower levels of organizational commitment (Tsui et al., 1992). Teams with high diversity were found to usually get into debates as a result of their heterogeneous perceptions. Diversity could lead to conflicts due to differences that result from dissimilar attitudes and beliefs.

2.2.1 Areas of differences in a workplace

In view of the fact that diversity can add to the business performance; if diversity was not managed effectively it could lead to multiple of adverse repercussions. Such kind of implications could include conflicts, miscommunication, higher levels of employee turnover, and other unintentional effects. The negative implications of diversity are usually acknowledged in terms of adverse behavioral and affective outcomes such as less social cohesion, relational conflicts and higher staff turnover due to employees’ perceived dissimilarity and adverse stereotypes about dissimilar employees (Fujimoto, Hartel and Azmat 2013).

Diversity can also lead to communication barriers (Polzer 2008). It is challenging to incorporate someone else’s values, diverse backgrounds, and norms and manage to work together (Jehn, Northcraft and Neale 1999). Managing diversity effectively requires that managers take several steps to modify values and attitudes and encourage their effective management of diversity.

Multicultural versus same-culture team:

Adverse reactions from the employees working in a diverse workplace could limit the potential of an employee himself and the organization as well. These adverse reactions could be differential organizational socialization, ineffective communication, biases, stereotyping, and perceptions of inequality in the workplace (Sadri and Tran 2002).

In general, it is perceived that teams with high diversity were found to end up having debates often due to their varied perceptions. Diversity could even lead to conflicts due to disagreements that occur from distinct attitudes and beliefs. It can also lead to communication barriers (Polzer, 2008). One of the challenges is also to incorporate their values, diverse backgrounds, and norms and manage to work together (Jehn et al., 1999). To manage diversity effectively managers are required to take several steps to adjust values and attitudes and encourage an effective management of diversity.

A diverse workforce generally has distinctive styles of communication, since team members could have differences in languages, levels of fluency, non-verbal signals through body language and facial expressions. Furthermore, they also differ in the ways of perceiving and interpreting information (Shaban 2016).

The main areas of differences in the cross-cultural workforce are as follows:

- Preferences for leadership styles: There is a preference for participative leadership in individualistic societies and low power distance cultures. While in collectivist and high power distance societies prefer more direct and charismatic leader.

- Group dynamics: individualism-collectivism has an effect on group dynamics since it has close ties to beliefs about groups. Collectivists are linked with the need for being with other people around them and the need for social support. They are more likely to have a preference to work in a team and are more devoted to their teams than individualists are. While individualists, on the other hand, are less likely to accept group demands. Collectivists also show strong favoritism to the groups to which they belong, while individualists do not have such strong group connections.

- Communication style: Masculine and individualist values have been shown to be related to direct communication styles, self-promotion, and honesty in communication. While collectivism, femininity, and high-power distance societies tend to have indirectness and modesty. In individualist, cultures communication is also the low context, which means that the verbal messages are considered to be most important rather than non-verbal part of messages. On the other hand, collectivist cultures have high context communication, in which non-verbal signs or indications carry a lot of meaning. It depends on the way a message is conveyed and the context, “perhaps” can mean “yes” to some or “no” to others. Communication styles may also vary all along a direct-indirect range according to cultural differences. Confucian legacy in East Asia promotes social relationships and concern for others, thus requiring politeness and diplomacy, while the philosophies of the West, individualism, and rationalism, promote freedom of speech, truth, logical thinking and objectivity, leading to explicit speech codes (Gao, 1998; Kang and Pearce, 1983; Tang and Kirkbride, 1986; Yum, 1988).

- Fairness perceptions and compensation: Individualist societies prefer equal rules in terms of rewards and punishments; which indicates that those who contribute more are supposed to be worthy of a greater reward. Collectivist cultures prefer equality rules and are more comfortable with members of the group receiving equal compensation despite individual effort or input.

Cultures with high power distance have a strong inclination for seniority rules which means that the greatest reward or responsibility to most senior or the eldest member of the group. About the perceived equality of decision-making criteria, individualistic societies specifically, when individualism is together with more femininity show a preference for a cooperative style in decision-making. While masculine, collectivist and high power distance cultures favor a hierarchical top to down decision-making process and show regard for authority.

- Conflict handling preferences: For conflict resolution, collectivist cultures prefer involvement of a third party or a mediator to solves issues and show concerns for the interest of the other party. In collectivistic societies, also people with feminine values have a tendency to ignore unfavorable situations in order to maintain group harmony and cooperative spirit. While individualists, people with masculine values display disagreement and unfairness by exiting the group.

- Work design: Individualists and people with low power distance orientation prefer work designs that let them have flexibility, personal autonomy, involvement in the decision-making process, quality of personal and family time. While people from collectivismic societies, high power distance cultures prefer structured roles, clear directions and they feel quite uncomfortable with empowerment or the need to show initiative ahead of conventional situations.

They also show an inclination for familiarity with their direct supervisors, feedback seeking, and expect and provide more paternalistic, caring, and trusting subordinate-supervisor relationships.

Understanding which types of workplace outcomes are prone to be affected by cultural values, managers would also benefit from understanding when culture is likely to matter most (Taras, Steel and Kirkman 2011).

2.2.2 Advantages of diversity

A company culture that values cultural diversity including racial, ethnic, language and religious diversity can render directly into greater profits. A company that embraces diversity, the employees there are likely to be engaged and feel that their employer understands and respects them and their culture. Also, when a diversity-valuing company needs to recruit new workers, you have the chance to seek out employees with the highest potential, regardless of their race, culture or ethnicity (Shaban 2016).

When a company has a diverse workforce, diverse customers in the target market are more likely to trust your brand and feel comfortable doing business with the company. If members of a diverse team understand the people in diverse target markets, they are perhaps better able to design and deliver products and services that meet the needs of these potential customers.

The positive implications of diversity are typically acknowledged in terms of cognitive outcomes such as greater innovation, ideas, and creativity that employees from distinct social backgrounds could bring. (Azmat, Hartel & Fujimoto, 2013).

2.3 Hofstede’s Culture Dimensions

The dimensions mentioned by Hofstede in the cultural dimensions theory stand valid in many types of research; they establish a link between an individual, a group of people and societal level phenomena. Those cultural dimensions are discussed in detail below:

2.3.1 Power Distance

This dimension deals with the fact that all individuals in societies are not equal. It expresses the attitude of the culture towards these inequalities amongst us.

It is defined as per the degree to which the less powerful people in an organization or institutions in a country accept and expect the inequality in power distribution. This dimension explains the inequality in societies that all individuals are not equal and articulate our attitude of the culture towards such inequalities which exists amongst us.

The more the ranking of Power Distance Index is higher the more the society accepts the inequalities amongst people. It means people are not expected to have ambitions beyond their rank. The subordinates are supposed to follow what the superiors say, accept the decisions of the person higher in power, and not expected to show disagreement with their supervisors.

In the societies where power distance is high, the method of communication is from top to down and directive. Negative feedbacks or challenging the person who has authority is not usual. Also, supervisors are not expected to seek advice from their subordinates while taking a decision. In low power distance societies’ employees are given more flexibility, autonomy, and are expected to make decisions frequently without supervisory approval (Taras, Steel and Kirkman 2011).

2.3.2 Individualism

This dimension explains the preference of a society the amount of interdependence on others or self. It is the extent to which people in a society look after own selves, rather than feeling responsible to their community.

It is also related to people’s choice of personal goals or collective goals with other people. In the societies that are individualistic, the people prefer to look after themselves and their immediate family only. While in collectivistic society there is a concept of ‘in groups’ or belonging to a larger social group, wherein people take care of others in exchange for reliability and good relations. This dimension addresses how much do the members of a society are interdependent on each other and act in the interest of the group.

In a collectivist society, colleagues are expected to be cooperative and prefer to work as a team. The organizational commitment of the employees is low, relationships with co-workers are more important than any task. The relationship between employer-employee is based on expectations – faithfulness by the employee and familial protection by the employer. Also, hiring and promotion decisions are sometimes based on relationships which are the main factor in such a society. Collectivists believe that any person, through birth and possible later events, belongs to one or more tight “in-groups,” from which he/she cannot easily detach him/herself. The in-group (whether extended family, clan, or organization) protects the interest of its members, but in turn expects enduring reliability (Taras, Steel and Kirkman 2011).

2.3.3 Masculinity

A society with high masculinity is driven by competition, achievement, and success, in such a setting, success is defined by the winner or best in the field, which is a value system that begins in school days and continues throughout organizational life.

A low score in this dimension depicts that the society is focused on caring for others and quality of life. A society where the quality of life is the sign of success and standing out from the crowd is not admirable is known as a feminine society. This dimension depends on what motivates people, to be the best or liking what they do.

Masculinity-femininity is the extent to which masculine values such as advancement, assertiveness, earnings, and the acquisition of things are valued, and feminine values such as friendly atmosphere, position security, physical conditions, and cooperation are devalued. In more masculine cultures employees will be more motivated to the extent that organizations emphasize performance, success, and competition, while in more feminine cultures motivation comes from maintaining warm interpersonal relationships, caring for the weak, and promoting societal well-being. There is also a gender role dimension to masculinity-femininity, as one would expect to see women in positions of higher power and authority in more feminine, rather than masculine, cultures (Taras, Steel and Kirkman 2011).

2.3.4 Uncertainty Avoidance

This dimension deals with the fact that the future is ambiguous and the anxiety it brings along with it. The score of this aspect depends on how different cultures deal with such kind of a situation of anxiety in different ways. It has also been defined as the extent to which the members of a culture feel endangered by ambiguous situations and have created beliefs that try to avoid such unknown situations is reflected in Uncertainty Avoidance.

It is the extent to which people are uncomfortable with situations that they perceive as unstructured, unclear, ambiguous, or unpredictable. In high uncertainty avoidance cultures, people try to avoid uncertain situations by maintaining strict codes of behavior and believing in absolute truths. In low uncertainty avoidance cultures, there are fewer formal guidelines and rules for how work gets carried out. A low score in this means the people are willing to accept and are comfortable with ambiguity in certain situations (Taras, Steel and Kirkman 2011).

2.3.5 Long-Term Orientation

It describes how every society maintains links with the past traditions while dealing with the present and challenges of the future. The societies that score low in this dimension prefer to retain time-honored traditions and norms and view social change with doubt (Taras, Steel and Kirkman 2011).

2.3.6 Indulgence

This dimension defines the level to which people control their desires and impulses, depending upon the way they were raised. Cultures can be described as indulgent or restrained. The societies where the control is relatively weak are known as indulgent and societies with strong control are known as restrained (Taras, Steel and Kirkman 2011).

Hofstede’s theory revealed that people have diverse and sometimes directly opposing, values, and beliefs depending on their country of origin. Studies show that national cultural differences exist and persist. Cultures tend to form around regions that also share common economic systems, history, or environmental characteristics.

Cultures with Confucian legacy tend to be collectivist and high power distance-oriented which is also indicative of the fact that national and regional cultures are significantly and predictably different from one another.

On the basis of the liking and the perception, it has been suggested that it is important to make a distinction between the culture as perceived and the culture as desired. Across nations, some differences in preferences scores have been found out, such as a lower desired level of power distance by women, and the higher preferences for femininity of young respondents. Most likely, the culture as desired varies more as per the group to which one belongs than the culture as perceived. Men and women may differ with respect to their preferences, but they all have common experiences when working in the same organization or in the same country. Therefore, it is understandable that their perceptions do not differ within one nation (Oudenhoven 2001).

2.4 Similarities and Differences between India and China

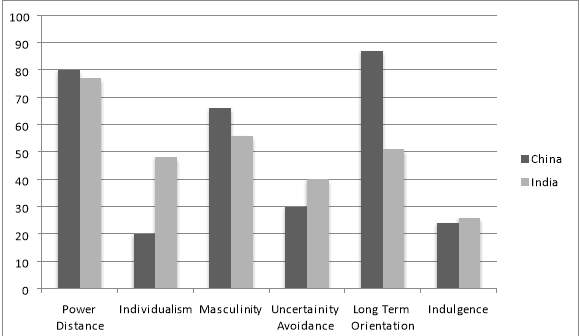

As per Hofstede’s cultural dimensions discussed above,

Table2

Source: (G. Hofstede, https://geert-hofstede.com/china.html n.d.)

| China | India |

| High Power Distance:

A score of 80, means a society that believes that inequalities amongst people are acceptable. Individuals are influenced by formal authority and are in general optimistic about people’s capacity for leadership. |

High Power Distance:

A score of 77, is close to China, indicating an appreciation for hierarchy and a top-down system in society as well as organizations. Dependency on the boss for direction/ decisions, acceptance of unequal rights. |

| Collectivism:

China is a highly collectivist culture where people act in the interests of the group and not necessarily of themselves. In-group considerations affect hiring and promotions with closer in-groups get preferential treatment. Whereas relationships with colleagues are cooperative for in-groups they could be cold or even hostile to out-groups. |

Individualism:

A transitional score of 48 means, it is a society with both collectivistic and individualist traits. Certain actions of the individual are influenced by concepts such as the opinion of one’s family, neighbors, work group and other social networks. The Individualist aspect of Indian society exists due to its dominant religion/philosophy. People consider them to be responsible for the way they lead their lives. |

| Masculinity:

At 66 it is a masculine society, success oriented and driven. The need to ensure success can be exemplified by the fact that many Chinese will sacrifice family priorities to work. Service sector people will provide services until late night. Some workers leave their families behind in hometowns in order to obtain better work and compensations in the cities. |

Masculinity:

Ascore of 56 means it is considered to be a masculine society also. India is a masculine society in terms of visual display of success and power. In more Masculine countries the focus is on success and achievements. Work is the center of one’s life and visible symbols of success in the workplace are very important. |

| Low Uncertainty Avoidance:

At 30 China has a low score on Uncertainty Avoidance. The truth may be relative though in the immediate social circles there is a concern for Truth. Adherence to laws and rules may be flexible to suit the actual situation and pragmatism is a fact of life. They are comfortable with ambiguity. |

Medium-Low Uncertainty Avoidance:

A score of 40 on this dimension means the society has a medium low preference for avoiding uncertainty. There is acceptance of imperfection in such societies; nothing has to be perfect nor has to go exactly as planned. |

| Long Term Orientation:

Score of 87 mean, it is a very pragmatic culture. In societies with a pragmatic orientation, people believe that truth depends very much on the situation, context and time. They show an ability to adapt traditions easily to changed conditions, and perseverance in achieving results. |

Intermediate Orientation:

Score of 51 means a dominant preference in Indian culture cannot be determined. Time is not linear and thus is not as important as to western societies which typically score low on this dimension. Such societies forgive a lack of punctuality or changing plans. |

| Low Indulgence:

China is a restrained society as can be seen in its low score of 24 in this dimension. In contrast to indulgent societies, restrained societies do not put much emphasis on leisure time and control their desires. |

Low Indulgence:

India also has a low score of 26 in this dimension, meaning that it is a culture of restraint. People with this kind of orientation have the perception that their actions are restrained by social norms. |

Source: (Singh 1990)

As per prior researchers, considerable differences between the countries with respect to all the dimensions of Hofstede’s theory were more realistic than the effects of other relevant factors, such as gender, age, and working experience (Powell, Francesco and Ling 2009).

2.5 Other Measure of Culture

A few dimensions from GLOBE (Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness) measures of culture also stand relevant in researches related to cultural dimensions (House 2004). The GLOBE measures of culture consider both societal practices (how things are) and societal values (how things should be).

2.5.1 Humane orientation

It is defined as “the degree to which individuals in organizations or societies encourage and reward individuals for being fair, altruistic, friendly, generous, and caring and kind to others” (House and Javidan 2004). Societies with a high humane orientation are expected to have a high level of social support and individuals are willing to take responsibility for others’ well-being. While, in low humane orientation societies, support for others is limited and people focus more on self-enhancement and self- sufficiency (Kabasakal and Bodur 2004). For example, members of cultures that are higher in humane orientation practices and values may provide greater support for individuals in managing the work-family interface than members of cultures that are lower in humane orientation practices and values.

2.5.2 Gender egalitarianism

It is defined as “the degree to which an organization or a society minimizes gender role differences while promoting gender equality” (House and Javidan 2004, p. 12), put emphasis on societal norms regarding women’s and men’s roles. For gender egalitarianism, the correlation between societal practices and values is significant and positive (Javidan, House and Dorfman 2004). Cultures that are higher in gender egalitarianism have a higher proportion of women in positions of authority, more female participation in the labor force, and less sex segregation in employment.

The influence of gender egalitarianism on the work-family interface may be more complex than that of other cultural dimensions.

2.5.3 Specificity/diffusion

This dimension is defined by Hampden-Turner & Trompenaars, 2000 in their research. It defines the level of particularity or wholeness a culture uses to define different constructs. People from specific cultures tend to be more objective and atomistic, while those from a diffuse culture rather focus on conceptual wholeness and integration. Some societies make an apparent distinction between an individual’s public and private lives; the public life is large and quite accessible to others compared to the private life space, which is smaller and not easy to enter. Diffuse cultures, greatly value all kinds of relationships, and there is often an amalgamation of a person’s public and private lives.

From the cultural dimensions mentioned above, only a few of them have an effect on the interface of WFC. Some aspects of culture are undeniably becoming more similar, while others are actually growing to be more different. The need for employees and customer management systems to match with the local culture still remains a necessary condition for building a successful global company (Taras, Steel and Kirkman 2011).

2.6 Work-Family Conflict

The definition of WFC implies that individuals have a limited amount of energy and time, with the exhausting effect of day to day roles unavoidably causing stress or inter-role conflict. Work-family conflict is considered to be bi-directional (Powell, Francesco and Ling 2009).

Two distinct forms of conflict that have been identified in the research by T.T. Selvarajan et al., are work interfering with family (WIF) conflict and family interfering with work (FIW)conflict. WIF conflict occurs when the family role is hindered by demands of the workplace, while FIW occurs when demands of the family hinder work-role performance.

2.6.1 Work-to-family conflict

It takes place when participation in work-related activities is hindered with input in a competing family activity (Greenhaus and Powell 2006). This type of conflict may occur due to lack of support from management and co-workers, limited job autonomy, increased job demands and overload, inflexible work schedules, and increased number of hours worked (Fredriksen-Goldsen and Scharlach, 2001).

Work demands relate to WIF (e.g., Frone et al., 1997, Hammer et al., 2005). Byron’s (2005) meta-analysis found relationships of WIF with working hours and perceived workload with stronger relationships for workload than working hours.

2.6.2 Family-to-work conflict

It occurs when involvement in a family activity hindered with participation in a work activity (Greenhaus & Powell, 2003).There are various factors affecting this type of conflict such as having a working partner, family support, equity in the division of household chores, satisfactory child care or eldercare provisions, gender and marital status of the person working, impairment level of adult-care recipients, and age of dependent children (Fredriksen-Goldsen and Scharlach, 2001).

Consequences of family interfering with work (FIW) may not necessarily be the same as in the case of WIF (work interfering with family; Frone, Russell, and Cooper, 1992; Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985). WIF might be particularly crucial because it has been noted that individuals tend to experience more WIF than FIW (Frone, 2003).

The former occurs when time demands of one of the domains (e.g., work) prevent performance in the other domain (e.g., home). The latter occurs when strain associated with one domain spills over to the other, such as coming home from work in a bad mood.

WFC can also be defined as “a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressure from work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect. That is, participation in the work (family) role is made more difficult by virtue of participation in the family (work) role” (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985, p. 77). For an employee, the main task nowadays is to discover and maintain a workable and acceptable amalgamation of these frequently conflicting work and family domains. Thus, the psychological familiarity of the term conflict is subjective to the level of demands individuals are confronted with at work and home, the meanings they attach to their participation in the work-family system, and by the resources available and their ability to use them to handle these demands (Saltzein et al., 2001; Felstead et al., 2002).

In a study related to the analysis of the relationship between work-family and job satisfaction it has been found that work-family conflict is related extensively with both types of job satisfaction (global and surface level satisfaction) and the relation was stronger with composite job satisfaction than with global satisfaction (Bruck, Allen and Spector 2002).

On the other hand, there is an indication that this effect is differently subjective to other factors such as the type of conflict and gender. Bruck et al. (2002) also found that out of the three forms of conflict considered altogether (time-based, strain-based, and behaviour-based), the behaviour-based was the only form of conflict significantly related to job satisfaction.

There have been comparisons of WFC across generations and over time: for all the three generations, mental health and job pressure were the strongest indicators of work-family conflict. Additionally, the authors found that the older generation had higher levels of contentment in the domains of job, family, marriage, and life than did the other two generations. Boomers accounted for higher life and job satisfaction than did Xers, while Xers reported a higher level of marital satisfaction (Beutell and Wittig-Berman 2008).

Gender differences were evident in this aspect, with men reporting higher levels of extrinsic work values and women reporting higher levels of intrinsic work values (Wray-Lake et al., 2011). In addition to generational factors, cultural and international differences are also considered in researches on WFC.

Work and family demands have been positively related to WFC, while work resources were negatively related to WFC. Furthermore, WFC was negatively related to family satisfaction.

The more time a person spends on a specific job, the more conflict there is between work and family (Bruck, Allen, and Spector, 2002). A clear connection between work and family stressors and employee strain on the work/family interface has therefore been established (e.g., Allen, Herst, Bruck, & Sutton, 2000; Byron, 2005). The effects are both culture general as well as culture specific. People are now often caught between the demands of work and family (Hsu, Chou, and Wu, 2001; Lu, Huang, and Kao, 2005), especially taking into consideration that family life is traditionally and still highly valued in a Chinese society (F. Hsu 1985).

It has been proposed that long work hours and heavy workloads are a direct sign of work-family conflict (WFC), as excessive time and effort at work leaves inadequate time and energy for family-related activities (Frone, 2003; Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985).

Kahn et al., (1964) stated that work-family conflict arises from an inter-role conflict, whereas (Renshaw 1976) suggested that it is the consequence of interaction between work-and-family- related stresses. The strong predictors of work-family conflict have been accounted working long hours, work overload and job stressors (Bakker and Geurts, 2004; Demerouti et al., 2004; Voydanoff, 2004).

2.7 Outcomes of Work-Family Conflict

There are three categories of outcomes of WFC: work-related such as job satisfaction, non-work related such as life satisfaction and stress-related such as depression, increase in the use of alcohol and substance abuse, a decrease in life, job satisfaction, and marital satisfaction, and increase the tendency to quit the job. In previous researches, the negative effects of WFC have been confirmed on individual well-being and organizational performance.

Research from Western countries also suggests that WFC can potentially lead to poor attitudes about the job, such as job dissatisfaction, also increased turnover intentions (e.g., Allen, Herst, Bruck, & Sutton, 2000; Mesmer-Magnus &Viswesvaran, 2005).

Work constraints have been found to hinder an employee’s performance and increase feelings of frustration (Peters and O’Connor 1980), job dissatisfaction, and turnover intention (Carsten and Spector 1987; Villanova & Roman, 1993). It is likely that work constraints may compel employees to work harder and longer to make up for an insufficient supply of work resources such as equipment, consumables, information, training, and manpower, therefore leading to WFC.

Researchers have shown that job satisfaction is related to motivation, citizenship behavior, withdrawal cognitions and behaviors, and organizational commitment (Kinicki et al., 2002). As a result of increased competition for employee talent and greater investment in employee development, turnover has become more costly, making employees’ job satisfaction and commitment a critical human resource issue (Cliffe, 1998). Although some organizational turnover is unavoidable, and may even be desirable, voluntary turnover is difficult to predict and can reduce the overall effectiveness of an organization (Smith and Brough, 2003). Turnover intentions are important because replacing an employee can cost at 150% of the employee’s annual salary (Bliss, 2001; Curtis and Wright, 2001).

The relationship between WFC and its outcomes also differ across various cultures due to cross-cultural differences in the evaluation and support mechanisms. Besides, the degree of the impact of WFC on its outcomes depends on the ways in which WFC is perceived to affect the domain that is most important in a certain society. WIF is expected to be most strongly associated with negative well-being outcomes in cultures where the family is the most important domain in life, while FIW is expected to be strongly related to negative well-being outcomes in cultures where work is an important domain in life (Eby et al., 2005).

Many public and private organizations have to develop family-friendly policies and programs due to the increasing pressures for attracting and retaining talented employees that are aimed at providing employees with resources to balance their work and family responsibilities.

Chapter III Research Model

The beginning of the global economy and the increase in global organizational competitiveness has led to an increasing number of people crossing cultural boundaries and having to deal with workplace diversity at its richest and most complex way. In previous studies, it has been proven that management practices in a country are dependent culturally, and the practices work in one country might not necessarily work in another.

The two major dimensions along with structures of organizations that differ are concentration of authority and structuring of activities (Geert Hofstede, 1998). Hofstede’s research has provided the foundation for many cross-cultural studies, most often for studies seeking to determine how differences on the basis of cultural dimensions (i.e., power distance, individualism, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity) impacted work-related outcomes.

In regard to work-family issues, organizational culture is often defined as the “beliefs, values, and shared assumptions concerning the extent to which an organization supports and values the amalgamation of employees’ work and family lives” (Thompson et al., 1999).

There are effects of management style on subordinates with different cultural characteristics (Jung and Avolio 1999), comparing actual leadership styles to cultural characteristics (Offermann and Hellmann 1997), and identifying leadership differences and preferences between work-groups from different nations (Kuchinke, 1999). The importance given to various aspects of life such as money, status, or vacation time varies across countries; the rewards are given at work and the financial or non-financial incentives also vary greatly across cultures (Schneider and Barsoux, 1997; Adler, 2002).

3.1 The Role of Culture in Studying WFC

The common terms used to conceptualize culture lay emphasis on values, assumptions, and beliefs, and norms that make a distinction of one human group from another which has been mentioned above as well. Cultural values are likely to play a role in the most relevant job and organizational traits used in decision-making, and the relative influence of recruitment on job choice.

If management systems are implemented without consideration for culture or policies are blindly generalized from one cultural environment to another, it could often lead to conflict, misunderstanding, dissatisfaction, undermined morale, and high turnover. The productivity losses can lead to a whole business failure.

It should be expected that as per the cultural values, employees might have a different understanding of the role of the organization in their lives. Cross-cultural differences in perceptions of the role of the organization in the personal life of employees should be kept in mind.

In the research by Brett, Tinsley, Barsness, and Lyttle (1997) culture can be put forth in two ways: culture as the main reason for differences observed, which attributes to the basic level differences in WFC to cultural variations while in the other approach, culture is the moderator. The links from culture to WFC, supports, and demands in the work and family domains acknowledges that the cultural values mentioned above in the literature review influence the existence of WFC and the type and level of demands and supports in the work and family domains. It is also suggested that culture also influences the strength of the relationship among WFC and its consequences.

3.2 Culture as the Main Effect Influencing WFC

In one of the researches, it has been suggested that WFC occurs in different ways across cultures. For example, the work and family are assumed to be segmented in some of the countries while in China they are integrated (Yang 2005). Due to the perception of segmentation, work and family roles are seen to be incompatible, rather than harmonious in an individualistic society (Joplin, et al. 2003).

When this kind of a conflict is experienced, it is perceived as a threat in some countries, but as an opportunity for development in China (Yang, Chen, et al. 2000). Also, it is perceived to be inevitable in India while preventable in the UK (United Nations 2000).

Across cultures, the type of inter-role conflict also differs (Aycan et al., 2004). For example, the roles of employee and parent are seen as conflicting in Israel, Singapore, and India; the employee and homemaker roles are viewed as conflicting in India; the roles of employee and spouse are seen as conflicting in Singapore and India. The cross-cultural differences in terms of various inter-role conflicts could be a function of importance in different societies. The job roles conflicting with the social roles are most prominent in some societies.

Many reasons exist for such cross-cultural variations, including differences in demands and supports in work and family domains (for example, the number of work hours, availability of support system and work-life balance policies). At the individual level, it seems that whether WFC is more felt by men or women, depends upon the strength of transition in gender roles or strength of role expansion in a society (Barnett and Hyde 2001).

It is assumed that developing economies, mainly those with conventional gender role stereotypes, experience WFC more than developed countries with egalitarian gender role stereotypes. Moreover, individuals holding traditional gender role stereotypes and experiencing role expansion are expected to be more prone to experience WFC as compared to those having egalitarian gender role stereotypes.

Studies have concluded that experiences of role conflict, role ambiguity, role overload, long working hours, schedule inflexibility, work-related travel, and job insecurity are demands of work that are associated with WFC. The extent to which they are experienced may depend on the culture and the socio-economic context.

Some work demands are considered to be culture-specific. For example, in collectivistic cultures maintaining harmony and avoiding conflicts in interpersonal relationships at work is an additional demand on employees (Ling and Powell 2001). Unresolved conflicts and tension at work could spill over to the family domain and may lead to strain-based WFC.

In collectivistic societies, another demand is the life-long care of children. Children’s academic achievement is the main responsibility of the family. Parents are involved in the care of the grandchildren. The care of the offspring is a life-long commitment for parents who are involved in their children’s lives at every age and stage. For working people, it is a big responsibility and a family demand. Therefore, in collectivistic cultures, care and guidance of children at every age and stage are important family demands.

Cultural values are one of the best predictors of workplace outcomes. Mainly, cultural values are stronger predictors of emotional display and many work-related attitudes and behaviors. Cultural values are much better at predicting emotions and attitudes in the workplace. It has a strong effect on job and co-worker satisfaction, organizational commitment, interpersonal relationships, ethics, communication and conflict resolution style. The same practice that may lead to brilliant results in one culture could be a failure in another.

A failure to align the organizational structure with the values of employees, customers, and partners may have a distressing effect on performance, sales, and cooperation and could undermine the success of any organization. Selecting employees for the set of values that best fit the existing organizational structure or job design could help to get rid of differences (Taras, Steel and Kirkman 2011).

3.3 Culture, WFC, and Consequences

WFC is defined as “a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect; which means participation in the work (family) role is made more difficult by virtue of participation in the family (work) role” (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985, p.77).

The psychological experience of ‘conflict’ is subjective to the level of demands individuals are confronted with both at work and home, the meanings they attach to their participation in the work-family arrangement, and by the resources available to them and their capability to utilize those resources to handle such demands (Saltzein, Ting, &Saltzein, 2001; Felstead, Jewson, Phizaclea, & Walters, 2002). Job stress and family stress were consistently related to WFC.

Previous studies on culture analyzed it as an intricate multi-layered and multi-facet construct. It is often described as an “onion” diagram with basic assumptions and values being the core of the culture, and practices, symbols, and artifacts indicative of the outer layers of the assemble (Hofstede, 2001; Trompenaars, 1993). People belonging to a common group or same society contribute usually to a common culture. It is established over an extended period of time and is stable. Due to an increase in migration and the cross-border expansion of business cross-cultural issues have become necessary to management (Vas Taras et al., 2009).

It would seem that societal or national culture has a key role to play in shaping the work-family interface. Norms and values related to the cultural meaning and enactment of work and family may influence the nature and strength of the relationship between individual’s experiences in these two domains (Ashforth, Kreiner, and Fugate, 2000).

Culture may moderate the relationships between such variables, intermediate outcomes such as work-family conflict (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985) and work-family enrichment (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006), and individual’s well-being. However, cultural influences on the work-family interface have not been acknowledged in major reviews of the work-family literature or the cross-cultural organizational behavior literature.

It has been studied that cultural values may affect the strength of the relationship between WFC and its outcomes and predictors (e.g., Hill, Yang, Hawkins, Ferris, 2004; Spector, et al. 2005). As mentioned in the previous section, cultural aspect has an impact on the occurrence and the type of demands and support mechanisms at both work and family domains. It can be suggested that factors leading to WFC are more likely to vary across cultures than its outcomes (e.g., psychological well-being) associated with WFC.

For instance, Spector et al. (2005) suggested that in individualistic cultures working for an extra number of hours is viewed as taking away time from their families, which results in the feeling of guilt and conflict with family. While in collectivistic societies, people consider working for long hours as a sacrifice for their family members (Yang et al., 2000).

Another research, conducted by Yang et al. (2000), explained that family demands such as spending less time at work had a greater impact on WFC in the US than in China, while work demands such as spending less time in the family had a greater impact on WFC in China than in the US. The main difference was due to cultural differences concerning the significance placed on family and work time.

The number of hours spent at work intrudes work-to-family conflict in cultures where the main role of work is to satisfy an individuals’ personal needs (such as financial and psychological), compared to cultures where the main role of work is to satisfy the family’s needs.

Disagreement and quarrels are a usual part of the day to day activities of any workplace, however, when people from different cultural orientations are interacting, complications beyond the usual tensions may arise, due to both to a different array of need and/ or differing conflict negotiation styles (Ting-Toomey 1998).

When an employee is placed with a group of workers who have distinct nationalities other than his own nationality, he is more likely to maintain social distance (Parillo and Donoghue, 2005; Verkuyten and Kinket, 2000). Social distance could be referred to as the degree of unwillingness to work together with other members of the group (Chan and Goto, 2003). This is because of the fact that people are used to be more comfortable when they interact with those, whom they perceive to be similar to them. People tend to like those whom they feel that they are similar to and dislike those whom they see that they are dissimilar to them.

3.4 Sino-Indian Cultural factors leading to WFC

Prior cross-cultural studies show that people from different cultural backgrounds tend to have different values leading to different behaviors (Adler, 1997; Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005; Triandis, 1989, 2003). Understanding cultural beliefs and values provides a foundation for developing effective business practices in an international framework. As globalization deepens, human capital has become a critical element for firm success (Kiessling& Harvey, 2005).

3.4.1 Individualism/ Collectivism

The main difference that can be understood is that in an individualistic society, people view work as a means to personal achievement and development. Excessive efforts spent in work pursuits are seen as being devoted to the self and neglecting the family. On the other hand, in a collectivistic society where people view the individual in terms of social networks, work roles are seen as serving the needs of the in-group rather than the individual. People who put extra effort into work are seen as making sacrifices for their in-group (e.g., family) and enjoy support from the family.

Individualistic societies view excessive working hours as family neglect and it could be viewed in a negative way that leads to conflict within the family. This should produce a positive relationship between the number of work hours and work-family pressure (the extent to which an individual perceives WIF as a source of stress). On the other hand, amongst Chinese and others in collectivistic societies, long work hours might be seen as self-sacrifice and a contribution to the family, leading to family member appreciation and support that helps alleviate work-family pressure. Thus, the relationship between work hours and work-family pressure would be reduced. Work hours would relate more to work-family pressure in the individualistic than in the collectivistic country clusters (Paul E. Spector et al., 2007).

Individualists are likely to focus on their own need. They would, therefore, be likely to respond negatively to a job that interferes with their needs. This means a job that produces WIF would likely be seen in a negative sense and lead to job dissatisfaction. In addition, a typical individualist response to dissatisfaction is to think about one’s own happiness and well-being, which should translate into intentions of quitting the job, and subsequent turnover if possible.

Collectivists would likely look up to co-workers for support in coping with WIF and adverse job situations rather than looking to withdraw from the situation. Instead, they more likely to view themselves in terms of social connections with co-workers and the employer, and would agree to sacrifice self-interest for the interest of the larger collective.

Individualists are likely to look at their jobs more as the means of making a living, possibly professional growth and self-actualization, but not as essential as a part of their personal life. In attempts to involve individualists too much into the life of their corporate family may be perceived as a waste of time, additional dues, and responsibilities, and lead to dissatisfaction and complaints.

It is common in individualist cultures for people working in the same office to not even be familiar with much information about families and interests of their co-workers, and yet remain fully satisfied with their workplace experience.

Collectivist and individualist societies advocate different types of relationships between employers and employees (Hofstede, 1980, 2001). In collectivist cultures, the relationship between employer and employee is seen in moral terms, resembling a family relationship with mutual obligations of protection in exchange for loyalty. Poor performance is usually no reason for an employer to dismiss an employee. Performance and skill are more often used to determine what tasks one assigns to an employee than to determine discharge. Such support from employers to employees is less forthcoming in individualist cultures. They generally remain loyal to the employer, even if that employer’s demands and practices produce WIF, and thus, they do not have negative feelings about the job as the cause of their WIF.

It can be understood that cultures do have effects on WFC, for example, individualism versus collectivism: Individualists had a stronger association between work-family conflict, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions than did more collectivistic countries (i.e., those within Asia, East Europe, and Latin America). They conclude that individuals from individualistic cultures would be more negatively affected by work-family conflict than would those from collectivistic cultures.

3.4.2 Humane orientation

It describes the degree to which a society values equality, generosity, self-sacrifice, and compassion regarding the social support and welfare of others (Powell et al., 2009).Societies with a high humane orientation have a higher level of social support from their family and friends, people of such cultures are willing to take the liability of others’. While, in low humane orientation cultures, support for others is limited and people care rather about self-enhancement and self- sufficiency (Kabasakal & Bodur, 2004).

For instance, in some countries, people tend to reside in nuclear families comprising a couple with dependent children, while people in some countries reside with families comprising more generations. Like in Chinese society, extended families usually form a close-knit protective social network that can be asked to provide social support and help in time of need and distress (Hsu, 1985; Lu, 2006), especially childcare from grandparents. In a few countries, such help is not readily available unless taken externally.

Also, the relationship between superior and subordinate in China is like a paternalistic relationship in which the supervisor would be willing to give advice to the subordinate for better future and help him in achieving better prospects in not only work but in personal life as well.

3.4.3 Specificity versus diffusion

This dimension refers to the level at which social constructs are viewed. Therefore, work-family roles may be viewed as independent from one another (Powell et al., 2009). Countries that are more diffuse, including China, view work-family roles as less compartmentalized and more integrated. Halpern’s (2010) study revealed that across cultures, role integration was significantly related to successful work-family balance. Diffuse cultures, give importance to all kinds of relationships, and there is often no distinction between a person’s public and private life.

For example, in a diffuse country like China, the development of guanxi (relationships) is important while doing business; which means, that managers spend a considerable amount of capital for time building by going out with colleagues for dinners outside of normal working hours. While, in specific culture countries, employees leave work on time at the end of the day and after working hours do not usually expect to attend to work-related responsibilities of any kind.

The number of hours at work sets limits on the number of hours available for the family. As such, hours spent at work are a precursor to time-based WIF. When too much time at work drains the energy people need to meet family demands, working hours may also relate to greater strain-based WIF (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985).

As a result family members are less likely to see work as competing with family, therefore being more likely to see work as competing with family, thereby being more likely to support the person’s efforts at work and less likely to resent the person for having less time and energy for the family. This would minimize an employee’s experience of WIF (Paul E. Spector et al., 2007).

3.4.4 Gender-Egalitarianism

The most discussed support mechanism in the family domain is the emotional and instrumental support from the spouse (Adams, King and King 1996). However, the type and the level of support in the family domain may vary across cultures. In cultures high on gender egalitarianism (House, Hanges, et al. 1999), it is likely to have more support from the male spouse or partner is more likely than it is in cultures low on gender egalitarianism.

Men who do housework in traditional cultures are may be looked down upon by their peers. Not only men but also women stick to long-established gender roles in cultures low on gender egalitarianism. Therefore, support from the male spouse to women is more likely in cultures high, compared to low, on gender egalitarianism. Support from the female spouse or partner to the men is more likely to be high in cultures low, compared to high, on gender egalitarianism.

Egalitarianism refers to a society’s minimization of differences between gender roles and its promotion of gender equality (Powell et al., 2009). Westman (2005) found that differences in the societal role of gender between cultures influenced crossover stress. Gender differences were present in some studies as women reported more concerns regarding family obligations undermining work prospects, while men reported greater concern that work obligations would interfere with family time (Gerson 2010). The researchers found that work-family conflict was higher for women than for men across all cultures and the work-family interface was related to job satisfaction for both genders and all cultures. As compared to China there is more gender equality; women get equal opportunities as men, there is more female participation in work and less sex segregation. While in India, it is not the same.

WIF can be linked to job dissatisfaction and turnover intentions. Since WIF represents a stressor originating in the work domain, it can lead to lowered satisfaction with the root cause of the conflict being the job a person does. WIF also relates to turnover intentions because leaving the job may be viewed as a way to cope with the stress associated with WIF (Bellavia &Frone, 2005). WFC has been linked empirically to job satisfaction and turnover intentions, often at a similar magnitude of correlation as role conflict.

As there have been advances in communication technology which has helped shape this workplace trend (e.g., cell phone, e-mail, text messaging), along with improved geographic mobility. There is a significant empirical evidence for the younger generation’s shift in values, goals, and expectations for balancing work and family roles.

The cultural dimensions mentioned above are studied in depth for this research since these dimensions are assumed to affect the WFC interface the most.

3.5 General Framework

Cultural Differences Work-Family Conflict Stress/ negative

Cultural Differences Work-Family Conflict Stress/ negative

(Sino-Indian) Psychological outcome

3.6 Research Questions

In a globalized world do cultural differences still exist in a workplace (between China and India)?

What are the reasons of WFC in a Sino-Indian cross-cultural workplace?

Are there differences in the level of WFC in a Sino-Indian cross-cultural workplace?

Chapter IV Methodology

4.1 Sampling

The Chinese organization referred to in this research is based in China, Shenzhen. It expanded its market to India in the year 2014. It is a smart-phone company with its Indian Head office located in New Delhi NCR and distributor companies spread across different states of India. It has workforce of more than five thousand Indian employees including the ones in the assembly line or the factory and more than three hundred Chinese managers. Interviews were taken from Indian employees working in this organization.

The Indian organization in the sample for this research started operating in China in the year 2002. The company provides services for Information Technology with its China Head office in Shanghai with branch offices in other Chinese provinces. The number of local Chinese employees in China offices is more than one thousand and Indian employees are more than one hundred. This organization has its presence in around hundred countries.

The main base offices of both the companies are located in their country of origin or home countries. The basic structure and the level at which comparison is done in this research is shown in Figure 2.

There were two focus groups, the theme of the focus group revolved around low to mid level employees, to understand how different company culture and management style lead to WFC in an employee’s life. The number of interviewees was fifteen per company which is thirty in total from both the countries. To understand the differences across various age groups, and backgrounds of employees, the interviewees with dissimilar demographics were interviewed randomly from different departments of the both the companies. The supervisors of the interviewees did not belong to the same culture as theirs so as to understand the differences between subordinate and their managers.

The choice of participants for interviews was based on the following few factors:

- Gender mix- The focus was to gather respondents from both the sexes in order to gain variations in opinions and experiences.

- Availability- Since the process is time-consuming and requires discussions it was important to choose participants with time on hand.

- Culture- The respondents clearly had to be from the culture different than the origin of the supervisor/management of the company.