Sustainable Development and Institutional Complexity

Info: 7807 words (31 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Tagged: Sustainability

1 Introduction

In addressing the challenges of sustainable development, the local level has become increasingly important over the last 25 years (Meadowcroft, 1997, Geissel, 2009). Similarly, as Australian populations grow, the deleterious environmental effects of increased population and land use planning failures increase proportionately (Jackson et al., 2017). In the face of these challenges, local government, as the tier of government closest to the population and to localised effects, is a large player in the field of enacting sustainability. Given the complexity of Australia’s three tiers of government and their interactions and responsibilities with environmental sustainability, how to deliver sustainability within a resource-constrained and constitutionally bereft environment is a key challenge for local government.

One area of increasing interest in the local government sector, is the applicability of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2015). At the 2015 United Nations General Assembly, 193 UN member states unanimously adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a global development agenda that lays out 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be achieved by 2030. The SDGs, which came into effect in January 2016, are a universal set of goals, targets and indicators that set out quantitative objectives across the social, economic, and environmental dimensions of sustainable development (Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments, 2016). Addressing critical sustainability issues such as poverty, climate change, inequality, economic development, and ecosystem protection, the SDGs will be implemented in all countries, across different territorial scales, including that of local governments.

For local governments that are working to improve the quality of life in their communities, the SDGs provide a roadmap for more balanced and equitable development. All local governments aim to increase prosperity, promote social inclusion, and enhance resilience and environmental sustainability. In this way, the SDGs already capture large parts of the existing political agenda in nearly all local government municipality. When aligned with existing planning frameworks and development priorities, they have the potential to strengthen development outcomes and potentially provide additional resource for local governments

All of the SDGs have targets directly related to the responsibilities of local governments. The process of translating these global goals down to the local level is known as the localisation of the global goals and has been identified as imperative for the success of the SDGs (United Cities and Local Governments, 2015). This is a new way for local government to think about how it progresses sustainability within the borders of its municipality, and like any new concept that requires a radical change of thought process, it comes with its own inherent complexities and challenges.

Against this background, this thesis seeks to examine whether institutional work theory (Lawrence and Suddaby, 2006) is a useful lens when exploring the strategies used by, and the experiences of, local government actors to create new ways of working within the sustainability sphere. After first outlining some of the challenges of local government in enacting sustainability, and the development of the Sustainable Development Goals, I review institutional work theory and the way that actors within the local government context may wield some of the tools outlined by Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) in their attempts to either establish new sustainability norms, disrupt old institutional practices that may work against a the creation of new sustainability institutions, and battle against the maintenance of practices that may impede new sustainability initiatives, such as will be required when attempting to progress the SDGs in a local municipality.

In order to test the hypothesis that actors within the local government context may engage in, or experience from others, some of the strategies outlined in institutional work theory such as resistance to new ways of working, a case study approach was employed using both semi-structured interviews with local government officers, and participant observation directly with Council business units on their experiences and familiarity with working to progress the 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

This research was situated within a local government entity in the South-East of Melbourne. This municipality is considered typical of other inter-face Councils in Victoria who are subject to a mix of rapid population growth and lower socio-economic constituents compared to inner-city municipalities, along with much larger boundary areas. Approximately 30 per cent of the land within an interface council is classified as urban, while the remaining majority of land inside their boundaries comprise of Green Wedge, agricultural land, national parks or rural communities. This brings with it particular pressures on the environment that are different to those of more metropolitan Councils. After analysing the responses from both interviews and participant observation, I reflect on the empirical analysis and how helpful the conceptual framework of institutional work is in understanding the complex real-world processes inherent in local government practice when trying to progress new ways of working. Finally, a new framework is suggested that may help to shape future pathways to sustainability for local government seeking to progress the Sustainable Development Goals, and how this contribution is intended to help address gaps in institutional theory literature.

2 Literature Review

Australia’s environment is subject to many of the same pressures being felt all over the world. The main pressures facing the Australian context are climate change, land-use change, habitat fragmentation and degradation, and invasive species. The key drivers of these environmental changes are population growth and economic activity (Jackson et al., 2017). Poor collaboration and coordination of policies, decisions and management arrangements across sectors and between different managers has been identified in the latest Australian state of the environment report (2017) as one of the issues working against effective sustainable management. One

In order to understand the challenges that Australian local government entities face in progressing sustainability within their municipalities, it is important to get an overview of the global context of sustainably and global efforts to address the need to do things differently. This chapter explores the literature in three key areas. It begins with a brief examination of worldwide and Australian progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (Ban, 2015); followed by the more specific sustainability challenges faced by local government, and finally, an exploration of the theory of institutional work drawing on Lawrence and Suddaby’s (2006) institutional work theory paradigm to determine if it is an appropriate lens through which to view challenges in local government in attempting to realise the Sustainable Development Goals.

2.1 Progression to the Sustainable Development Goals

Realisation of the worldwide environmental problems that were developing in the late 1960s compelled the international community to establish the United Nations (UN) Environment Programme in 1972. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) recognised that only governments with clear commitment and leadership could generate the institutional, policy and regulatory impetus for environmentally sustainable reforms (Organisation for Economic and Development, 2002). International support for the role of local government in environmental sustainability followed this process, through Chapter 28 of Agenda 21, commonly referred to as Local Agenda 21 (LA21) and the formation of organisations such as the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI) (Thomas, 2010, Mercer and Jotkowitz, 2000, Evans et al., 2006, Wild River, 2006, Laurian and Crawford, 2016, Bajracharya and Khan, 2004, Khakee, 2002).

At the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit on 25 September 2015, world leaders adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to end poverty, fight inequality and injustice, and tackle climate change by 2030 (see Figure 1). The SDGs build on the Rio +20 outcomes and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (United Nations, 2012).

The SDGs are universal, meaning they apply to every country in the world, not just developing countries, an important distinction from the Millennium Development Goals which focussed much more on poverty alleviation rather than seeing poverty and equity within the sphere of the earth’s capacity to provide a habitable environment (Griggs et al., 2013, Béné et al., 2014). This shift in emphasis from the MDGs was intended to address several of their perceived shortcomings and incorporate a broader and transformative agenda that more adequately reflects the complex challenges of the 21st century and the need for structural reform in the global economy (Fukuda-Parr, 2016, Stuart and Woodroffe, 2016, United Nations Development Programme, 2016). The MDGs were essentially a North-South aid agenda and consequently the goals and targets, such as universal primary education, were mostly relevant for developing countries and have been labelled by some commentators as ‘Minimum Development Goals” (Harcourt, 2005). Other commentators have noted that the MDGs were weak in the facilitation of participation and voice in relation to reviewing implementation (Waage et al., 2015). The eight MDGs and 21 targets were limited to ending extreme poverty. In contrast, the 17 SDGs are about sustainable development of all nations. This includes ending poverty as a core objective but the 17 goals and 169 targets set out a broader agenda that also includes environmental, social and economic sustainability.

Translating these national concerns, or ‘localising’ the SDGs is the process of taking into account subnational contexts in the work towards achieving the 2030 Agenda (United Nations Development Programme, 2015). This can range from the setting of goals and targets, to determining the implementation, and using local indicators to measure and monitor progress. Localisation relates to how local governments can support the achievement of the SDGs through action from the bottom up and how the SDGs can provide a framework for local policy development. While the SDGs are global, their achievement will depend on making them a reality in cities and regions. All of the SDGs have targets directly related to the responsibilities of local governments, particularly in their role in delivering basic services. As stressed in the Synthesis Report of the UN Secretary General “many of the investments to achieve the sustainable development goals will take place at the subnational level and be led by local authorities” (Ban, 2015). Similarly, the Report of the High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda (United Nations, 2013 p.10) states that ‘local authorities form a vital bridge between national governments, communities and citizens and will have a critical role in a new global partnership’.

Local and regional governments (LRGs) played an important role in influencing the definition of the SDGs, campaigning for international recognition of the pivotal role that local governments play in sustainable development. As per the findings on the global consultations of the UN on the localisation of the SDGs, co-led by the Global Taskforce of LRGs, UN Habitat and the UN Development Program (States News Service, 2015), local and regional governments are essential for promoting inclusive sustainable development within their municipalities. By creating broad-based ownership, commitment and accountability, they are seen as vital partners to the implementation of the SDGs (Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments, 2016). The LRGs 2017 report to the High Level Political Forum (HLPF) stated that local and regional governments have been involved in the reporting process of voluntary national reviews (VNRs) submitted by 65 UN Member States and UN agencies on the localisation of the SDGs in 2016 and 2017, with local governments being involved in at least 38 countries (58% of Member States). 27 countries included LRGs in high-level decision making or consultation mechanisms created for the coordination and follow-up of the SDGs. The key messages approved by the consultation were:

- Local and regional governments are essential for promoting inclusive and sustainable development within their territories and, therefore, are necessary partners in the implementation of the SDGs

- Effective local governance can ensure the inclusion of a diversity of local stakeholders, thereby creating broad-based ownership, commitment and accountability

- An integrated multi-level and multi-stakeholder approach is needed to promote transformative agendas at the local level

- Strong national commitment to provide adequate legal frameworks and institutional and financial capacity are required (States News Service, 2015)

National legislation and regulations provide the frameworks within which local and regional governments act. Such frameworks can create incentives or obstacles for sustainable development (Freyling, 2015) especially in relation to local resource management, fiscal and financial decentralization, inclusive economic development and environmental protection. Some of the enabling elements identified in the Roadmap for Localizing the SDGs (2016) are multi-level governance mechanisms and multi-stakeholder partnerships and the capacity building of local and regional governments in relation to the SDGs, empowering them to maximize their contributions, even in the face of limited competencies. Other UN reports (United Nations Development Group, 2014) have highlighted a number of criteria for a multi-stakeholder partnership to be effective and add value. For example, several of the Dialogues emphasized the need for a clear delineation of responsibilities between the various partners, and for dialogue and transparency of decision-making processes. The Dialogue on localizing the agenda also indicated that a clear division of labour is needed between different levels of government, taking into account the comparative advantage of each level and accompanied by coordination mechanisms that harmonize efforts (United Nations Development Programme, 2015). This is especially relevant as most countries, including Australia, have multi-level governance structures, meaning that local governments are directly responsible for delivering a large part of the national governments’ commitment to the SDGs. As much as 65 percent of the SDG agenda may not be fully achieved without the involvement of local actors (Cities Alliance, 2015 p. 19).

2.2 Sustainability progression in Australia from a local government perspective

In the years following the creation of the UN Environment Programme, Australia’s national and state governments established agencies and programs to try to manage environmental concerns, but these provided no role for local government. The complexities and overlap arising from the differing levels of government were further emphasised in the 1999 EPBC Act which some authors describe as an effort by the federal government to shift responsibility for the environment to the states by giving itself only an assessment role (Hollander, 2015, Curran, 2015). Although local government is recognised as playing a role, it has virtually no formal powers as it is considered a mechanism of the State and part of its internal structure. Each local government area is responsible for management of the environment within its boundaries, in compliance with the relevant state and federal laws and policies (Thomas, 2010).

Australia’s three-tiered system of government makes for a complicated natural resource management policy and legislative arena. Since 1900 the Australian Constitution has formed the basis of current government in Australia, however 117 years later it does not cover areas of current community and political concern. One of these omissions is that there is no recognition of the role of local government. Following the British model, local government in Australia was established as an arm of state governments. Another omission is the lack of a formal role for any tier of government in environmental awareness and management. The Australian Constitution makes no mention of “the environment”. When the states were passing their legislation at the end of the nineteenth century there was no formal recognition that the environment was important. However, since the mid twentieth century both local government and environmental issues have been important aspects of life in Australia (Thomas, 2010, Curran, 2015, McNeill, 1997). There is consequently much variation in the environmental responsibilities and capacities of the 537 local governments in Australia. There is also considerable diversity across local governments according to geographic size and population. Typically, those with larger areas and a smaller number of residents are those located in rural and regional areas (Pini et al., 2007, Wild River, 2006).

Unlike many of their international counterparts, local governments in Australia were traditionally responsible for a set of narrowly defined services provided through property levies. This was the source of the axiom that positioned local government as concerned solely, or largely, with ‘roads, rates and rubbish (Thomas, 2010 p.123). Since 1989, however, all states have instigated new local government acts which have resulted in the sector having a much broader brief, including responsibilities for community development, economic growth as well as natural resource management (Pini et al., 2007)

There are good reasons for focusing national attention on local government. Wild River (2006) states succinctly;

‘Every environmental issue is a local environmental issue. Even when those issues also capture the attention of state and territory, regional or Commonwealth agencies, the local governments in which they are located always have a profound and enduring interest that is worthy of attention by all spheres and stakeholders. Local government is the sphere of government that is closest to the people and environment (p.2).’

Despite being the smallest and least resourced of Australia’s three government spheres, local government environmental spending far outweighs that of the others (Wild River, 2006, McNeill, 1997). However, due to the lack of constitutional recognition, and the attendant funding and legislative functions, local government faces substantial difficulties in enacting many of the sustainability and environmental management solutions that it is now responsible for (Wild River, 2006, Evans et al., 2006, Dollery et al., 2014, Mercer and Jotkowitz, 2000). The role of local government in environmental management has clearly moved past the traditional ‘roads, rates and rubbish’ narrative and world-wide there are many examples of local governments being heavily involved across the spectrum of environmental issues (ICLEI, 2015, ICLEI, 2016), however many researchers have noted that local governments face many barriers in developing and implementing their environmental policies (see, for example; Pini et al., 2007, Keen and Mercer, 1993, Whittaker, 1997, Lawrence et al., 2013a, Laurian et al., 2016).

| Constraint | Reference |

| Lack of information and data | (Measham et al., 2011, Whittaker, 1997) |

| Imposed policy frameworks from state and federal governments | (Measham et al., 2011, Wild River, 2006) |

| Resource constraints | (Pini et al., 2007, Wild River, 2006, Measham et al., 2011) |

| Lack of community literacy in sustainability | (Peters et al., 2010, Nalbandian et al., 2013) |

| Lack of consensus building | (Whittaker, 1997) |

| Lack of political will | (Thomas, 2010) |

However, despite these identified challenges, many scholars are arriving at the conclusion that actors within the local government sphere play a very important role in the realisation of sustainability and that this role becomes even more important when it comes to implementation (Wang et al., 2014, Zeemering, 2017, Laurian and Crawford, 2016). Following research undertaken on local government activity within adopting alternative water practices Morison and Brown (2010) discuss how local government actors help overcome internal organisational resistance to change; and how they can work with industry and the community in evolving educative, facilitative, and regulatory ways to enhance environmental policy effectiveness . The ways in which these local government actors can work within this space has become an area of interest for many scholars. Drawing on contemporary institutional theory scholarship (Bos and Brown, 2012, Khakee, 2002, Platje, 2008), one way of conceptualising the internal patterns of behaviour and ways of working, as well as the collective values, knowledge and relationships that exist within any organized group in society, is institutional capital. Institutions that have high levels of such capital might reasonably be expected to act effectively and efficiently and to demonstrate institutional initiative and responsibility and there are diverse theories on the best way to measure this (Bansal and Gao, 2006, Iarossi et al., 2011). In the context of sustainable development it might be expected that such institutions would be proactive in the undertaking of sustainability initiatives (Evans et al., 2006).

Some study has been undertaken on the capacity for organisations such as local government to undertake sustainability initiatives, see for example (Thomas, 2010, Pini et al., 2007, Evans et al., 2006, Saha, 2009, Bos and Brown, 2014) however, the extent of activity is as broad as the scope of the environment itself. The important question of how effective the activity has been, and how effectiveness could be improved is often overlooked (Ji and Darnall, 2017). Despite the obvious role of local government actors in facilitating sustainability initiatives, the success of these ventures is rarely discussed in the literature. This deficiency is especially salient as local governments move from developing sustainability initiatives to implementing them. While the literature generally does a good job in describing local sustainability practices (what sustainability is at the local level) and motives (why sustainability is important for local government), more research is needed to understand both the conditions and the management of successful implementation. That is, more research is required to explain the role of actors in enacting sustainability within the institution of local government and the success or failure of their endeavours. One of the areas that local government is beginning to be active in, is the implementation of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (United Cities and Local Governments, 2015).

2.3 The Sustainable Development Goals in Australia

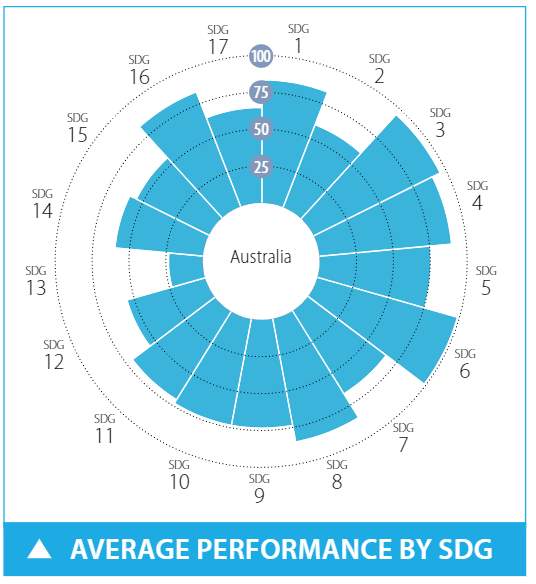

Sustainability in Australia, as in all areas of the globe, is a complex issue, indeed, the term sustainability itself can be problematic as it has so many possible connotations (Manderson, 2006, Ramsey, 2015). Similarly, Australia’s cities are described as some of the most ‘liveable’ in the world (Neild, 2016), however we still have a long way to go to meet some of the Sustainable Development Goals, many of which directly relate to the liveability of human settlements. The UN 2017 SDG Index and Dashboards Report (Sachs, 2017) ranks Australia as 26 out of 157 countries against different nations’ performance on the 17 SDGs. The purpose of the report is to help countries identify the gaps that need to be closed in order to achieve the SDGs by 2030 and to identify priorities for action.

Australia has some of the world’s highest carbon emissions per person and rates poorly on clean energy (SDG 7) and climate change (SDG 13). Additionally, biodiversity loss (SDGs 14 and 15) and land clearing are also areas of concern. As can be seen by Figure 2, Australia performs fairly well on the UN’s Human Development Index which focuses on social and economic development but the areas relating to environmental sustainability are extremely deficient (Sachs, 2017). This demonstrates that Australia needs to act urgently to address climate and environmental goals. This is an area of increasing activity for local governments who may be able to help address these shortcomings (Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments, 2016, United Nations Development Group, 2014).

Increasingly in Australia, local government bodies and other organisations are beginning to recognise the need to align their internal strategies with the Sustainable Development Goals. Some of the Victorian organisations to begin the process are The City of Port Phillip (2017), City of Melbourne (2017), ancilliary organisations such as the Resilient Melbourne collaboration (2017) and universities such as Monash University (2016), RMIT (2016), and Macquarie University, Victoria University and UTS (Sustainable Development Solutions Network Australia/Pacific, 2017). However for many, transitioning away from the traditional, siloed ways of enacting sustainabiity may require a large shift in the previous institutions or ‘ways-of-working’. The very nature of the Sustainable Development Goals are transactional and each goal is not meant to be taken in isolation, but the linkages and overlaps are intended to be part of the process of progressing towards realising them.

2.4 Sustainable development and institutional complexity

There is an inherent complexity when thinking about forms of institutional practice to address sustainable development. Institutions are by their nature reproduced ways of doing things, a stable foundation on which individual actors, communities of practice, and all tiers of government base their everyday actions on and seek legitimacy for (Ostrom, 2005, Young, 2008) whilst effective sustainable development requires flexibility and the ability to adapt readily to both environmental shocks and the pace of the modern world, both of which are moving at an unprecedented rate (Duit et al., 2010). Some researchers look to forms of governance that they term ‘anticipatory’ (Boyd et al., 2015) in order to determine how our imbedded institutional practices can work with the apparent contradiction of static institutions and the need for adaptability, whilst others look within institutional practices themselves to explore how existing institutions resist pressure to change, how they are disrupted, or how new institutions are created and stabilised (Beunen et al., 2017). The balancing of these apparent contradictions are a feature of ongoing research (Davoudi et al., 2012). Flexible institutions that allow innovation and can adapt to new pressures and environmental risks such as climate change (Folke et al., 2005, Cruz et al., 2016) are desirable. However those that allow environmental policy to be diluted or permit governments to retract from national and international commitments on political whims are less so (Rootes, 2014). Achieving a productive balance between stability and flexibility of institutions, when engaging in sustainable development, is likely to depend on a range of dynamic actions that may both promote or resist change at different times (Beunen et al., 2017). The flexible and transactional nature of the Sustainable Development Goals is likely to be a challenge for organisations such as local government, who are used to working within much more rigid institutional practices. In examining how such institutional changes might occur, Lawrence and Suddaby’s (2006) theory of institutional work practice may offer a lens to examine how different actions may be used by local government actors to fulfil their sustainability aspirations.

2.5 Institutional work theory

Some early conceptions of institutional work, such as neo-institutionalism, implied that institutions arise from an unintentional social construct where actors are subject to the rules-as-usual of institutions rather than as participants in the creation and recreation of the institutions within which they live and work (Lawrence et al., 2010, Willmott, 2010). However, Lawrence and Suddaby’s concept of institutional work describes “the purposive action of individuals and organizations aimed at creating, maintaining and disrupting institutions” (Lawrence and Suddaby, 2006 p.25) and goes on to depict institutional actors as reflexive, goal-oriented and capable. It focuses on actors’ participation as the centre of institutional dynamics and it strives to capture structure, agency and the interrelations between them. A practice perspective on institutional work is made clearer in its contrast with a process perspective on institutions. The focus of processual descriptions of institutionalisation is on the institutions: what happens to them; how they are transformed; what states they take on and in what order. In contrast, a practice orientation focuses on the world inside the processes – the work of actors as they attempt to shape those processes, as they work to create, maintain and disrupt institutions (Brouwer and Huitema, 2017, Lawrence and Suddaby, 2006). Together, these shifts lead to an image of action as dependant on cognitive (rather than affective) processes and structures, and thus suggests an approach to the study of institutional work that focuses on understanding how actors accomplish the social construction and reproduction of rules, schemas and cultural accounts (Lawrence and Suddaby, 2006).

This perspective on institutional work suggests that we cannot step outside of action as practice – even actions which are aimed at changing the institutional order of an organisational field occur within sets of institutionalised rules. Lawrence and Suddaby describe some actions, techniques and generalizable procedures that are applied in the disruption/transformation of social practices (Lawrence and Suddaby, 2006). Battilana and D’Aunno in Dobbins (2010) build directly on Lawrence and Suddaby’s typology to argue that we can identify three new forms of agency in institutional studies, each of which operates within institutional creation, maintenance, and disruption. “Iterative” agency refers to small-scale decisions that can reinforce institutions or move them in a new direction, such as choosing one institutionalised practice over another. “Practical-evaluative” agency refers to self-conscious actions to reinforce, or remake, institutions within existing ideational frameworks, such as collating elements of different institutionalized systems together for new purposes. Finally, “Projective” agency refers to actions designed to re-imagine, or re-theorise, the institutional terrain, such as challenges to taken-for-granted institutional logics.

2.5.1 Creating institutions

Early research into the conscious creation of new institutions primarily examined institutional entrepreneurship (Fligstein, 2001, Lawrence et al., 2013b, Czarniawska, 2009, Battilana, 2006). This approach emphasises agency in institutional theory however it was confined to actors with the resources to engage in institution building, and did not examine coalitions of actors working together in subtler ways. Sense-making practices and communication between actors is important in institutional work and goes beyond the actions of a single person (Fredriksson and Pallas, 2015). Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) outline nine sets of practices that result in the creation of new institutions;

| Forms of Institutional work | Definition |

| Advocacy | The mobilization of political and regulatory support through direct and deliberate techniques of social suasion |

| Defining | The construction of rule systems that confer status or identity, define boundaries of membership or create status hierarchies within a field |

| Vesting | The creation of rule structures that confer property rights |

| Constructing identities | Defining the relationship between sets of practices and the moral and cultural foundations for those practices |

| Changing normative associations | Re-making the connections between sets of practices and the moral and cultural foundations for those practices |

| Constructing normative networks | Construction of interorganizational connections through which practices become normatively sanctioned and which form the relevant peer group with respect to compliance, monitoring and evaluation |

| Mimicry | Associating new practices with existing sets of taken-for-granted practices, technologies and rules in order to ease adoption |

| Theorizing | The development and specification of abstract categories and the elaboration of chains of cause and effect |

| Educating | The educating of actors in skills and knowledge necessary to support the new institution |

Some researchers describing frontrunners or early champions who collectively steer the creation of new institutional practices claim that under the right conditions, these actors can greatly influence the course, speed and direction of new institutional practices (Brown et al., 2013, Taylor, 2009, Iarossi et al., 2011). Taylor (2009) denotes two differing types of ‘champions’ who may be involved in the creation of new forms of institutions, the first being the change agents who work on projects and rely on personal forms of power to influence, and secondly, those who enjoy more formal, positional power and who are likely to be more senior. The combined efforts of both kinds of leaders is seen to be more effective than one or the other working solely (Taylor, 2009, Brown et al., 2013).

Inter-organisational work, sometimes referred to as ‘boundary work’ and ‘practice work’ is also recognised as having a role to play in the creation and legitimacy of new institutions. Zietsma and Lawrence (2010) found in their research that institutional creation was associated with a combination of boundary and practice work that provided safe spaces for actors to experiment with new ideas and develop new ways of working together. Other researchers have also acknowledged the importance of experimentation in the creation of new institutions (Bettini et al., 2015). This may have a great deal of importance when attempting to progress Goal 17 of the SDGs, Partnerships for the Goals.

2.5.2 Maintaining institutions

In general, work aimed at maintaining institutions involves supporting, repairing or recreating the social mechanisms that ensure compliance. Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) identify six types of institutional work devoted to maintaining institutions. The first three, ‘enabling’, ‘policing’ and ‘deterring’, primarily address the maintenance of institutions through ensuring adherence to rule systems. The latter three, ‘valourizing/demonizing’, ‘mythologizing’ and ’embedding and routinizing’, focus efforts to maintain institutions on reproducing existing norms and belief systems. Each of these types are elaborated below. See Table 3 for a summary of the forms of institutional work associated with maintaining institutions.

| Forms of institutional work | Definition |

| Enabling work | The creation of rules that facilitate, supplement and support institutions, such as the creation of authorizing agents or diverting resources |

| Policing | Ensuring compliance through enforcement, auditing and monitoring |

| Deterring | Establishing coercive barriers to institutional change |

| Valourizing and demonizing | Providing for public consumption positive and negative examples that illustrates the normative foundations of an institution |

| Mythologizing | Preserving the normative underpinnings of an institution by creating and sustaining myths regarding its history |

| Embedding and routinizing | Actively infusing the normative foundations of an institution into the participants’ day to day routines and organizational practices |

Some of the work being done in sustainability transitions looking at phenomena such as policy resistance (de Gooyert et al., 2016), describes feedback loops that push systems back toward their initial conditions. Through the institutional work lens, this can be seen as a maintenance of an institutional practice. Some authors describe the difficulties within the creation of new sustainability institutions as being “aggravated by strong path dependencies” (Markard et al., 2012 p.955) and powerful vested interests who do not want the status quo to change (Hess, 2014, Capoccia, 2016). Similarly, scholars in transition dynamics such as Forrester (1971) and de Gooyert et al. (2016) explain that society can become frustrated as repeated attacks on deficiencies in social systems lead only to worse symptoms. This can be viewed as an example of the demonizing component of the maintaining of institutional work, simply understood as – we tried it before and it didn’t work, we’re better off staying with what we have. Overemphasising structure creates such a strong narrative for why things are the way they are that there is no room left for change (embedding and routinizing structures) and only incremental changes can be made (Markard et al., 2012). A focus on structure can illuminate why new institutions can be difficult to enact however it doesn’t provide much help for ways to overcome institutional maintenance when seeking to create a new practice.

2.5.3 Disrupting institutions

In contrast to earlier interpretations of actors as passive within the confines of institutions, disrupting institutions is a clear example of the effort that is central to the concept of institutional work. Effort from the perspective of disrupting institutions might be allied with the idea of the struggle of individuals or groups to step outside of the established roles or activities they usually engage in, and adopt a more reflexive stance in order to engage in the institutional work required to transform their work and living conditions (Lawrence et al., 2010). In many ways, creating institutions is closely related to disrupting them, however some researchers (Oliver, 1992, Lawrence and Suddaby, 2006) point out that there is a distinct difference in tactics used in disruption work than those in use in creation. Table 3 outlines these tactics and forms of disruption.

| Forms of Institutional work | Definition |

| Disconnecting sanctions | Working through state apparatus to disconnect reward and sanctions from some set of practices, technologies or rules |

| Disassociating moral foundations | Disassociating the practice, rule or technology from its moral foundation as appropriate within a specific cultural context. |

| Undermining assumptions and beliefs | Decreasing the perceived risks of innovation and differentiation by undermining core assumptions and beliefs |

Some authors have discussed tactics that may be used by actors to disrupt institutions such as Zietsma & Lawrence (2010) who describe the use of dramatic language such as ‘earth rape’ and ‘wounds that bleed’ by a group of activists attempting to delegitimize the institutional practice of forest clearcutting in Vancouver. Institutional disruption may often strongly depend on narratives in which current perspectives and institutional structures are questioned or criticised (Beunen et al., 2017) . Institutional work aimed at disrupting the relationship between an institution and the social controls that maintain and perpetuate it by disconnecting rewards and sanctions, disassociating moral foundations and undermining assumptions and beliefs all lower the impact of those social controls on non-compliance thereby making it more palatable to engage in replacing those institutions with something new.

2.6 Inter- and intra-organisational capacity for change

The emergence of environmental problems has engaged researchers, policy makers and communities all around the world in attempting to craft solutions via industrial and societal transformations. Large-scale utilities such as transportation, energy and water have been areas of great focus and research, especially given their large impacts on environmental degradation, resource scarcity and climate change (Rogers et al., 2015). Within the nascent institutional theory scholarship, many authors have overlooked the important aspect of inter-organisational interactions between local governments and external organisations (e.g. Fuenfschilling and Truffer, 2014). This is an oversight given local governments are involved in nearly every aspect of environmental and social issues, particularly within Australia (Thomas, 2010, Curran, 2015). The ability for organisations to forge new ways of working when seeking to progress the Sustainable Development Goals is explicitly stated in Goal 17 – Partnerships for the Goals. Equally important is the intra-organisational ways of working within local government as many local government business units work largely as if they were separate units to the rest of Council (Mukheibir et al., 2013, Measham et al., 2011). In this aspect, what might normally be considered external inter-organisational capacity may have the same benefits when attempting to work together across the breadth of areas that local government covers.

There has been some early work into the importance of ‘bridging organisations’ in the form of intergovernmental committees, cooperative research centres and capacity building programs (Brown and Clarke, 2007, Wong, 2006) in the transference of institutional capacity between organisations, however some researchers have noted that there is a lack of published work that focuses on the internal changes in organisational capacity required when engaging in the creation of an inter-organisational innovation (Bos and Brown, 2014, Farrelly and Brown, 2011). Van De Meene and Brown (2009) found in their literature review of water management research and commentary that peer reviewed journal articles published on inter-organisational capabilities of water management regimes far outweighed that of intra-organisational capabilities, demonstrating a dearth of work being done on the internal capacity of organisations to engage with the inter-organisational work necessary in the development of new sustainable solutions. As the world continues to move from a traditional fragmented model of environmental management to the more nuanced and adaptive model of sustainable development, the challenge to local government will be to use whatever intra-organisational capacity it has to effectively engage in the new regimes being proposed by the Sustainable Development Goals.

To this end, this research intends to contribute to the recognized knowledge gap by exploring the internal capability of local government seeking to localise the Sustainable Development Goals through the institutional work lens. It is hoped that this research will assist in understanding the nuances and experiences of local government in attempting to create and contribute to these new institutions of practice, and these insights can potentially help build a framework to assist local governments everywhere in their efforts to translate these global goals down to the local level to make explicit every day work can actually contribute to a better world.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Sustainability"

Sustainability generally relates to humanity living in a way that is not damaging to the environment, ensuring harmony between civilisation and the Earth's biosphere.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: