Systematic Reviews for Policy Decision-Making

Info: 8897 words (36 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

1 CHAPTER ONE: Introduction

1.1 Systematic reviews for policy decision-making

The last 30 years has seen a proliferation of systematic reviews seeking to synthesise the best available and most relevant evidence to inform policy. Although the evidence-based policy and practice movement originated from medical science’s concern with reducing harm and improving patient health outcomes it has expanded beyond clinical health to a range of public policy sectors and disciplines. (Oliver et al. 2015). In the UK, this movement can be traced back to the British Government’s commitment to ensuring effective evidence-based programme service delivery in the 1980’s and was further galvanized by the New Labour government in the 1990’s. This has led to the establishment of statutory bodies responsible for producing systematic reviews including guideline development; such as the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) which provides evidence-based guidance on health and social care, and NHS Evidence, which publishes systematic reviews to inform local commissioning of services (NHS Evidence 2011).

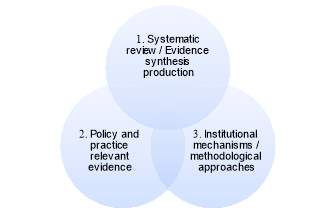

Developing methodological approaches to evidence synthesis and ensuring institutional mechanisms are in place to support the production of a range of review products for evidence-informed decision making is a primary objective of the Evidence for Policy and Practice (EPPI)-Centre. In my 13 year tenure at the EPPI-Centre, my key research activities have included building capacity to undertake systematic reviews in new policy and practice areas (e.g. education, adult social care, and more recently international development) and producing different types of systematic reviews, for a range of audiences. There is no one methodological approach to conducting a systematic review, however, the overall purpose can be summarised as the use of systematic, transparent, and replicable methods to identify, critically appraise and synthesise published or unpublished works (Gough et al. 2012a). The aims of systematic reviews can stretch from instrumental: e.g. should a decision maker invest in programme A or B? to enlightenment e.g. influencing ‘decision-making through changing perceptions and opinions’ rather than providing a yes or no answer to a question (Gough and Thomas 2016, p.88). Policy-relevant systematic reviews ‘present findings clearly for policy audiences to: illuminate policy problems; challenge or develop policy assumptions; or offer evidence about the impact or implementation of policy options; and take into account diversity of people and contexts’ (Oliver and Dickson, 2016 p.235). Within this diversity, systematic reviews contain three distinct research stages: 1) Review inception: outlining the question, scope and methodological approach; 2) review execution: conducting the review; through to 3) review dissemination: communication of findings, with each of stage providing an opportunity to engage with stakeholders and make decisions which maximise and increase the policy and practice relevance of a review.

1.2 Models and mechanisms for producing systematic reviews

The policy context in which the need for synthesised evidence arises can also be diverse and pose unique challenges, as two different worlds, with their own set of social norms and values ‘meet’ (Dickson and Oliver, 2015). Two overarching processes can be identified at the policy-research interface. Firstly, ascertaining what ‘relevant’ evidence might mean and look like for each review of set of reviews commissioned, at that point in time and why. Secondly, making judgements throughout the review process about whether the evidence synthesis product proposed will meet needs and expectations. These processes often require a range of institutional mechanisms and engagement with the type of methodological approach that will be taken to produce a new systematic review (Oliver et al. 2015). Identifying these processes and development of thinking around them came in response to a growing interest in the process of strengthening the capacity to undertake evidence synthesis. This lead to my involvement in two primary research studies exploring the perspective of policy makers and academics about the production of systematic reviews to inform health systems policymaking. This first study (Oliver and Dickson, 2015) outlined four models for achieving policy-relevant systematic reviews (see figure 1.2) and institutional mechanisms for navigating the policy-research interface (see figure 1.3) while the second study used this framework to investigate examples of exchanges across research and policy worlds to understand the process of producing systematic reviews in more detail (Oliver et al. 2017).

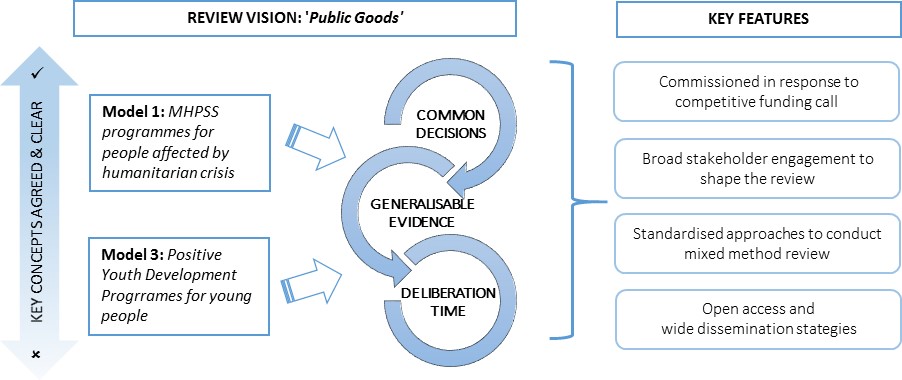

For example, the first study found that reviews may be commissioned for use as ‘public goods to address common problems’ (models 1 and 3) or focus on addressing specific decisions to inform ‘immediate local or national policy concerns’ (models 2 and 4). Within each of these broad aims, the conceptual clarity of a review’s scope may also vary, with key concepts existing on a continuum from widely agreed and clear (model 1 and 2) to not very well defined (model 3 and 4). We found that each of these broad dimensions are likely to influence the type of institutional mechanisms and methodological approaches required to support the production of systematic reviews. For example, the need for open access publishing to reach multiple audience (model 1), producing evidence to inform local decisions more likely when directly linked to policy teams (model 2), the need to make conceptual sense of findings by drawing on diverse set of stakeholders (model 3) or the need to draw on knowledge brokers to mediate policy input directly as part of responding to urgent call for evidence (model 4). Cutting across each of the four models, we conceptualised institutional mechanisms as falling within higher order themes, framed according to the overlapping social worlds of policy and research. These included: shared motivation, mutual engagement, and supportive structures and procedures for producing evidence and resulting impact. Each of these analytical themes are briefly described below (see figure 1.3).

Figure 1.2 Models for achieving policy-relevant systematic reviews*

I

*Oliver & Dickson (2015)

Diversity and aligning motivations for producing systematic reviews

“Aligning the motivations of policy makers and systematic reviewers is an essential first step for a satisfactory project” (Oliver et al. 2015).

Systematic reviewers and policymakers have different levels of experience and exposure to producing and using evidence. Researchers may not be familiar with designing systematic reviews to meet policymakers needs. Similarly, policymakers may not be familiar with the types of evidence synthesis and systematic review products possible to address the scale and scope of their concern. Thus, aligning the motivations of reviewers and policy makers, to identify and ascertain what type of systematic review and evidence synthesis is required is an essential part of the review process.

Mutual engagement between policy and research

Making decisions about what type and how to conduct a systematic review is not a purely technical exercise, but can be understood as an interactive social and political process, supporting the production of new knowledge. When systematic reviewers and policy makers work together, it can provide a platform to communicate and understand their interests, informing the design and shape of a review from inception to the dissemination of findings. It can also provide mutual opportunities to build or extend capacity in producing and using evidence to inform policy decision-making.

Establishing structures

Enabling engagement between researchers and policy makers benefits from pre-existing or the development of new structures to support collaborative working practices. These can include producing reviews as part of ‘on-call’ reviews programmes, or by directly linking evidence from systematic reviews into guidance development panels. It can also include the use of knowledge brokers, i.e. ensuring there is an intermediary between reviewers and policy makers to support greater communication.

Formalising procedures

Standardised procedures to produce systematic reviews products can be found across different organisations and institutions, and are often the first choice when producing evidence for use as public goods. However, when reviewers are producing evidence synthesis to inform immediate and/or local policy decisions, attention may need to be paid to certain aspects of reviewing. For example, some methodological approaches may need to be prioritised over others, and standardised procedures may need to be adapted, to ensure timeliness and relevance and evidence.

Impact

The greater use of evidence may be supported by producing credible evidence relevant to more than one policy setting and/or timely access to clear policy messages based on critically appraised evidence synthesis findings. Greater applicability of evidence may also be enhanced by engaging with local stakeholders who helped shape and contextualise the review findings, and support the identification of gaps in the evidence-base to support future knowledge production.

Figure 1.3 Analytical framework for policy relevant systematic reviews

*add ref

1.3 Aims and approach

1.3.1 Research questions

These models and mechanisms were developed in a health systems policy context. Their applicability and transferability could now usefully be ‘tested’ against reviews commissioned in other contexts and disciplines to explore each configuration in further detail. Using the publications, I have submitted for consideration, the aim of this thesis will be to demonstrate how my approach to conducting systematic reviews contributes to an understanding of the institutional mechanisms and systematic research methods required to produce policy relevant evidence. This thesis will be guided by the following research questions:

- To build on the models in figure 1.1, what review-level evidence exists on the institutional mechanisms and methodological approaches to evidence synthesis to support the production of relevant systematic reviews to inform policy decision-making?

- How have my publications contributed to an understanding of the institutional mechanisms and methods required to support the production of policy relevant reviews to inform decision-making?

- Model 1: Facing ‘common problems’, drawing on agreed taxonomies, to produce ‘generalise evidence for use as public goods’ in international development (Mental health and psychosocial programme, Bangpan, Dickson, et al. 2017)

- Model 2: Facing ‘immediate’ UK policy concern to inform ‘specific’ policy decision-making with key concepts agreed in advance (Meta-review on adult social care outcomes framework, Dickson et al. 2015)

- Model 3: Facing ‘common problems’ to produce ‘generalisable evidence for use as public goods’’ where key concepts needed clarification (positive youth development, Bonell C, Dickson et al. 2016)

- Model 4: Facing ‘immediate’ UK policy concern to inform specific policy development with many key concepts unknown in advance (No-fault compensation scheme, Dickson et al. at 2017)

- What are the main findings of the above analyses; to what extent has my mechanisms available and methodological approach to producing policy relevant reviews developed thinking in this area? (Discussion)

- What are the main gaps and what areas of future development in the production of policy relevant reviews to inform decision making? (Conclusions)

1.3.2 Methodological and epistemological approach

Supporting publications, from four review projects, were used as case studies to explore the validity and utility of each of the models outlined. This was achieving by taking the analytical framework (figure 1.3) developed and applied in two of the supporting publications (Oliver and Dickson 2015, Oliver et al, 2017) and operationalising the higher order themes into questions that I could use to interrogate my approach to producing systematic reviews. I chose systematic reviews projects that were sufficiently aligned to each individual model (see appendix three). This ‘analytical interrogation’ was an iterative and interpretive process which required me to draw on my ‘the use of self’ to reflexively generate new insights and understanding about producing policy relevant views, based on my experience in the field (Finlay and Gough 2008) I also discussed those reflections with co-authors and colleagues. Reflections were collected and recorded in a verbal and written research journal.

Initial reflexive positioning led me to trace back to my original reason for joining the EPPI-Centre, which was namely to conduct research that would be ‘useful’. It also led me to identify, that as a practitioner, I have sought to be evidence-informed and aware when delivering mental health and social care services (e.g. working with children in a domestic violence refuge, and with adults as an integrative psychotherapist). As a practitioner, I have always valued ‘building collaborative working practices’ and considered ‘the quality of the relationship’ and ‘mutual reciprocal engagement’ between practitioner and client as the primary vehicle enabling a therapeutic process to elicit change. These ideas are reflecting in my approach and thinking about working with people to produce reviews and inform the analysis in this thesis. My approach to producing evidence from systematic reviews and the writing of this thesis is also informed by a critical-realist epistemology (Bhaskar, 1998) originating from my background in applied psychology and sociology. In simple terms, a critical realist world view is one in which reality is understood to exist independently of our perceptions, while simultaneously accepting that our understanding of reality is socially constructed (Maxwell, 2012). ADD

2 CHAPTER TWO: Background

This Chapter has X sections. Sections 2.1 reports the findings from a systematic review conducted to inform this thesis. ADD

2.1 Search of the literature

2.1.1 Objectives and review questions

As outlined in Chapter 1, the production of systematic reviews requires a range of institutional mechanisms and methods to ensure relevance to policy. To further develop and ground the analytical framework presented in chapter one (figure 1.3) with existing research I conducted a systematic scoping review of the literature to identify any existing synthesis or overviews on this topic. The aim of the review was to answer the following research question: What review-level evidence exists on the institutional mechanisms and methodological approaches to evidence synthesis to support the production of systematic reviews to inform policy decision-making?

2.1.2 Concepts and definitions

The scope of the review has three interrelated dimensions:

Systematic reviews and evidence synthesisproduction: the generation of synthesis generated from systematic research-based activities;

Policy relevant evidence: the relevance of evidence to policymakers and practitioners; including the usefulness of evidence to inform behaviour and the enlightened uses of evidence in shaping knowledge and understanding of, and attitudes toward social issues (Nutley et al., 2007; Weiss, 1979).

Institutional mechanisms and methodological diversity: the processes which mediate and support evidence production to enable its relevance and potential use.

2.1.3 Methods

A systematic search of electronic databases, google scholar and citation checking was completed in October 2016. Systematic reviews published in English were included if they investigated any aspect of the production of systematic reviews to inform policy. Systematic reviews on processes and interventions supporting the uptake and use of evidence, a closely related field but not the direct subject matter of this thesis, were excluded. Types of evidence falling within the scope included evaluations of interventions supporting the production of systematic reviews, or qualitative or quantitative data seeking to understand the processes of producing systematic reviews to inform policy, such as people’s views on the barriers and facilitators to generating evidence. Search results were imported into the systematic review software, EPPI-Reviewer 4 (Thomas et al. 2014) and screened on title and abstract. Full reports were obtained for those references where title and abstract suggested the study was relevant or where there was insufficient information to judge.

2.1.4 Results

After the removal of duplicates, 1,280 citations were identified from the search. A total of 126 full text reports were retrieved and re-screened. However, none met the eligibility criteria for inclusion. Further exploration of primary studies also confirmed the paucity of research in this area. A comprehensive breakdown of the flow of studies through the review is provided in Appendix two. The findings from the screening process did reveal that while there is a body of literature on evidence-informed policy making, the concentration of systematic reviews is concerned with the processes and mechanisms contributing to the successful uptake of evidence. This focus largely concentrates on the final review stages; dissemination and communication of systematic review findings, with much less focus on the process and mechanisms involved in each stage leading to the completed evidence synthesis output. This lack of evidence on how reviews are produced from their initial inception to becoming synthesized knowledge available for policy translation and used in policy making is a significant gap in the field.

Figure 2.1 Gaps in the evidence base

In the absence of review-level evidence to answer the research questions, I will instead draw on the wider literature to inform the three key dimensions relevant to this thesis (see figure 2.1); Systematic review and evidence synthesis, as a form of knowledge production and the relationship this has with producing evidence for policy and policymaking, including the opportunities, challenges and approaches to working at the research-policy interface and what this poses for producing evidence; and the potential role of institutional mechanisms and methodological approaches to address and mediate some of those challenges and maximise opportunities.

2.2 The production of synthesized evidence to inform policy

In simple terms, the policy-research interface can be characterised by the flow of research knowledge from its production to its use by policymakers. Research knowledge in the context of this thesis refers to knowledge generated via scientific research activity. This activity is usually identifiable by its observance to a pre-defined set of epistemological and ontological principles (refs). As a form of research knowledge, evidence generated from systematic reviews aims to bring together and summarise what is known from individual sources of research knowledge and provide ‘research-based answers’ to the kinds of social problems policymakers are routinely asked to address (Gough et al. 2017, Lavis 2004 p.1615). Systematic reviews can also establish what is not known and inform decisions about what further primary research should be undertaken. In sum, they support policy makers to answer key questions about: ‘what do we know, how do we know it?’ as well as ‘what more do we want to know and how can we know it?” (Gough et al. 2013 p.5).

The underlying assumption of systematic reviews is that the generation and use of synthesised research evidence can better inform policy and improve decision making. However, others argue that producing evidence in itself is not sufficient, as that evidence also needs to be ‘relevant’, ‘accessible’ and ‘useful’ to policy and policy makers (refs). This ‘Utilitarian Evidence’ model of evidence production (Hanney et al. 2003, de Leeuw and Skovgaard 2005, de Leeuw et al. 2008) suggests that those generating evidence are likely to be different to those using evidence, thus the producers of knowledge, in this case researchers, need to design and communicate research with its end users (e.g. policy-makers and other stakeholders) in mind. How ‘utility’ is achieved can be sometimes opaque. de Leeuw et al. (2008) hint at stakeholder engagement, but cite others who argue that the utility of research occurs via ‘relatively autonomous processes and events’ (e.g. Kingdon 2002 p.12) or via the ‘enlightenment / percolation / limestone idea whereby research‘slowly seeps into the realities of politicians and practitioners’ and becomes used (e.g. Overseas Development Institute 1999, Hanney et al. 2003). The systematic review of reviews on strategies to increase evidence-informed decision making by Langer et al. (date) also touches on these ideas. Their review suggests that it is the context in which evidence is produced which can contribute to a greater understanding of the mechanisms informing how evidence becomes to be judged as relevant and usefulness by decision-makers. They suggest that concepts such as ‘relevance’, ‘usefulness’, and the notion of utility, are highly specific to the needs of those individual policy makers, at any given time.

As the demand for research-based answers has grown so have debates articulating its challenges for policy use (Fox 2005) emerging alongside a greater understanding of the policy-research interface as a complex and dynamic phenomenon (refs). These discussions have drawn attention to the political nature of policy making and evidence production (K Oliver 2014), with many authors highlighting that neither generating or using evidence is a value neutral or a purely academic exercise (Liverani et al. 2013). Weis (1979) over 30 years ago, highlighted that generating evidence for policy does not follow a linear route; i.e. the flow of scientific evidence does not occur by simply generating and making it available to policymakers or practitioners. Although research can and does inform different stages of policy making (e.g. policy agenda setting, formulation and implementation) each of those stages and the extent to which scientific evidence will inform them is shaped by socio-political dynamics specific to each context (Dobrow et al. 2004). Research evidence is competing alongside other sources of knowledge and inputs influencing policy decision-making, such as local and national data, values, beliefs, wider socio-economic contexts, and resources (refs).

When exploring the barriers between the production of epidemiological research, and it’s use by local health policy development in the Netherlands, Goede et al. (2010) outline a useful overview describing the breadth of frameworks seeking to explain the gap between evidence and policy use. They argue, that even when frameworks move away the ‘rational’ approaches characterised by knowledge ‘push’ or ‘pull’ models, the ‘dissemination explanation’ which does not assume that knowledge transfer is automatic, or the ‘two communities’ explanation which does assume that a cultural gap between research and policy needs to be bridged, each framework is weakened when they continue to ‘assume a linear sequence from supply of research to utilisation by policy makers’ (p.4). The authors, argue this inaccurately place responsibility of research use with either ‘producers (researchers) or with users (policy makers) rather than emphasising that the production and utilisation of knowledge is based on ‘a set of interactions between researchers and users’ p.5. In the context of systematic reviews, these set of interactions occur at the research-policy interface, bringing with them their own set of challenges and opportunities.

Thus, it is becoming more helpful to conceptualise working at the research-policy interface, to produce evidence, as a socially dynamic and non-linear process. Gibbons et al. (1994), for example, suggests that there are two ‘modes’ of knowledge production. In mode one, producing new knowledge is more likely to adhere to traditional paradigms of scientific discovery and is identifiable by the ‘hegemony of theoretical or, at any rate, experimental science; by an internally-driven taxonomy of disciplines; and by the autonomy scientists and their host institutions’ (Nowotny et al. 2003 p.179). They contrast mode one with the emergence of mode two knowledge production, which is ‘socially distributed, application-oriented, trans-disciplinary, and subject to multiple accountabilities’ (Nowotny et al. 2003 p.179). In mode one, the problems scientific enqury seeks to address are largely determined by academic interests from a singular discpline. In comparison, mode two, knowledge production is said to occur ‘in a context of application’ and is more likely to include a range of stakeholders ‘collaborating on a problem defined in a specific and localised context’ (Gibbons 1993, p.3) and is generating knowledge across disciplines.

Despite criticisms of oversimplification and the potential for generating a false dichotomy of knowledge production it is possible to see that systematic reviews can span both mode one and mode two and that producing evidence to inform policy has much in common with mode two. The authors also suggest that engaging in forms of mode two knowledge production can develop greater reflexivity. This is a result of conducting research which seeks to identify a ‘resolution’ to problems. Thus research activity in this context ‘has to incorporate options for the implementation of the solutions and these are bound to touch the values and preferences of different individuals and groups that have been seen as traditionally outside of the scientific and technological system’, whom, ‘can now become active agents in the definition and solution’ (Gibbons et al. 1994 p.7).

2.3 Types of of synthesized evidence to inform policy

2.3.1 add

Aside from the two key aspects of systematic reviews which separate them from traditional literature reviews (e.g. the transparent approach taken to identify and include studies and the critical appraisal judgements made about those studies, Gough et al. 2017) reviews can vary greatly. This variation is usually found in the type of questions being asked, the primary studies required to answer those questions and the methodological paradigm related to each guiding the overall review (Gough et al. 2017). Although, policymakers often want answers to questions on effectiveness (e.g. “what works”), which systematic reviews are mostly known for, they may also seek evidence which fall outside of traditional “what works” questions. Policy questions often need to be understood and translated into questions that can be addressed. This process needs to ensure that the review question(s) retain their policy focus, which is likely to be broad and transdicplinary, but is sufficiently operationalised that it can be answered by review methods.

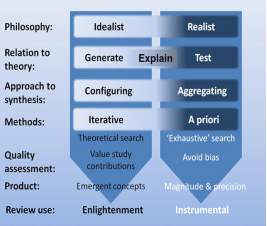

Figure 2.2. ‘dimensions of difference’ provides an overview of the epistemological variation that can be found in systematic reviews. ‘What works’ review question often fall in the right-hand column and attempts to aggregate (add up) quantitative data using statistical analysis to test a hypothesis (e.g. does programme a produce outcome b). Effectiveness reviews are usually concerned with avoiding bias to produce credible and generalisable evidence, and document their methods in advance. They often adopt a realist approach, which assumes there is an observable world that can be known and understood. They also seek to produce review outputs that can provide policymakers with some form of certainty; i.e. by identifying studies that evaluate the same type of programme, adding up their results and providing greater confidence in the final aggregated answer. Policymakers may also ask questions, which are fit into the left-hand column and configures (arranges) data to generate new concepts or theory. Configurative reviews allow for different levels of iteration (e.g. the extent to which concepts are developed or modified before or during the review process) and lean towards a more idealist philosophical stance. This type of review can have greater explanatory power than aggregative reviews and can provide policymakers with more contextual understanding of a phenomenon; i.e. by placing and connecting study findings next to each other, the synthesis can build up a partial or full picture of the whole and explore how findings may relate to one another (Gough and Thomas, 2017).

Figure 2.2 Dimensions of difference in systematic reviews

Generally speaking producing policy relevant evidence often requires conducting reviews which may draw on aggregative and configurative synthesis methods. Systematic reviews commissioned by policy often start with a wide-ranging policy concern that needs to be broken down into separate answerable review questions requring different types of review methods. The review question may remain broad, to identify and describe what literature is available first i.e. ‘mapping’ the evidence base (Sutcliffe et al. 2017) before deciding if there are sufficient studies to answer a sub-review question such as ‘what work’s or conduct a configurative review or a combination of both. In some cases, there may be a proliferation of existing reviews warranting a ‘systematic review of systematic reviews’ (meta-review) rather than a systematic review of primary studies.

2.3.2 Transdisciplinary

Systematic reviews have evolved from focusing on single medical issues to address ‘real world social problems’, doing so has led them to seek evidence and generate knowledge that goes beyond single methodological and academic disciplines (Oliver et al. in press). Similarly, mode two, transdisciplinary research has emerged from a practical need to provide local and contextually relevant evidence (Regeer and Bunders 2009) with diverse research teams and multiple stakeholders. Producing policy relevant systematic reviews, like ‘transdisciplinarity’

is an integrative process in which researchers work jointly to develop and use a shared conceptual framework that synthesizes and extends discipline-specific theories, concepts, methods, or all three to create new models and language to address a common research problem. (Stokols et al. 2008 p.S79)

Synthesising evidence from different disciplines can also support fill important gaps in knowledge and understanding that would have been ‘missed’ if addressed separately. However, the challenge for research, including systematic lies in bringing together different disciplines, methodological study designs, and multiple stakeholder views to address complimentariry and diversity in a way that is useful to end users Scholz & Steiner (2015).

2.4 Barriers to the production and use of synthesized evidence to inform policy

Research is primarily undertaken in academic institutions, while policymakers are usually based in local and national government departments. In broad terms, the aims of each organisation differ, influencing how they are structured and governed. Although policymakers are increasingly being asked to improve their policy development processes, to ensure it is innovative, forward-looking and joined up (e.g. UK Cabinet Office’s Professional Policy Making initiative), the extent to which this includes being evidence-informed varies (Hallsworth 2011). In contrast, academa has primarily valued to the advance of knowledge via the publication of rigorous research outputs, although more emphasis is being placed on other forms of knowledge dissemination (refs). This is seen in the response to recent calls that research knowledge is not only high quality but also accessible and available to those outside of the academic community, which can also be met with varying degrees of receptivity and support (ref et al. date). In most instances, policymakers are accountable to governmetnts, politcial parties and the public, while researchers are held to account by their funding bodies and individual institutions. These differences, and the extent to which policy makers and researchers have been exposed to each others worlds, and their organisational expectations and responsibilities can have implications for collaborative working practice between them to support the production of policy relevant evidence (refs).

Two recent systematic reviews exploring the barriers and facilitators to uptake of systematic reviews found that policymakers’ lack of awareness and familiarity with systematic reviews limited their use and involvement with them (K Oliver et al. 2014, Tricco et al. 2016). They also found that policymakers’ attitudes about the utility of systematic reviews and their knoweldge and skills to interpret the findings of reviews were also barriers to evidence uptake. Conversely, the ‘clarity and relevance’ of reviews (K Oliver et al. 2014 p.6) and a ‘belief in their relevance, and their applicability to policy’ supported their greater use (Tricco et al. 2016 p.5). Another theme to support evidence use identified by Oliver et al. (2014 p.4) was ‘contact, collaboration and relationships’ and the importance of building ‘trust and mutual respect’ (p.4) between policymakers and researchers. Similarly, Tricco et al. (2016 p.5) report that ‘participants perceived systematic reviews were useful if they had confidence in the review authors’. The findings in each of the reviews point to a need to have better engagement between researchers and policymakers during the review process, as ‘such interactions have the potential to promote the generation of policy-relevant research’ (Liverani et al. 2013 p.6).

An ongoing difference and source of tension between the world of research and policymaking is also timeliness. The policymaking context is characterised as unpredictable, fast-paced and operating on short-time frames, compared to the slower more deliberate pace typical of conducting research. Whether systematic reviews are commissioned as a ‘one off’ to inform a specific decision or a series of systematic reviews to inform a larger policy area it is likely that evidence is expected within a pre-defined timeframe (Lavis et al. 2006). Generating evidence that is readily available and in synch with the needs of policy decision-makers has led to new ways of engaging and conducting reviews. This includes engaging with each aspect of the review process to maximize the use of the time available (Oliver et al. in press). ADD

A pivotal role to address this need for greater engagement has emerged for knowledge brokers (Lomas 2007). ‘Knowledge brokering’ as a mechanism to address the need for greater engagement and bridge the gap between research and policymakers is becoming ubiquitous in the field (Lomas 200). Knowledge brokers are increasingly being assigned a professionally defined role in collaborative research partnerships, acting as an intermediary between researchers and policy decision makers (refs). Operating as a ‘connector function’, knowledge brokers can facilitate greater interaction so that reviewers and policy decision makers are ‘better able to understand each other’s goals and professional culture, and influence each other’s work’ (Traynor et al. p.534). In addition to their role of ‘linking and exchanging’ ideas between different professional groups, some knowledge broker also act as project ‘knowledge’ managers. This entails co-ordinating different aspects of the review (e.g. commissioning, protocol development, and peer review,) and building capacity to produce and use evidence in reviews. Their dual role in capacity building includes supporting reviewers to generate evidence that can be of use to policy makers and to develop capacity in policymakers to utilise research evidence. Knowledge brokers can also mediate ad support researchers and policymakers navigate the type of systematic review evidence and produce they might require.

In their reflective account of “The Evidence Request Bank project”[1], Morton & Seditas (2016) provide an example of working closely with policy and practice partners to ensure they devised an evidence synthesis research plan that was relevant to informing their current programme of work. They found that partners, who were thinking more in practical rather than research terms, needed a clear process that could facilitate the identification of reviewable research options. This was achieved by devising a series of questions to ‘identify’ and ‘interrogate’ partners to support their thinking and help them move from larger issues to to more specific focus. This process retained an understanding that what constitutes meaningful evidence might differ between the partners and that useful evidence was more likely to be defined by its relevance and applicability to its current policy and practice context rather than adhering to strict scientific research principles. ADD

ADD – STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT TO SUPPORT POLICY RELEVANCE AND USE – including issues around the relationship and dialogue and the individual skills needed to engage with stakeholders – CAPACITY TO ENGAGE AND PRODUCE SYNTHESISED EVIDENCE TO INFORM POLICY ADD:

Named barriers to evidence use included access [41], capacity to analyse and interpret evidence [42], availability and relevance [58] and knowledge of different sources and types [42].

DISSEMINATION STRATEGIES: summarise two reviews:

Disseminating research findings: what should researchers do? A systematic scoping review of

conceptual frameworks

3 CHAPTER Three: Producing evidence for use as ‘public goods’

3.1 Review context

3.2 Introduction

In this chapter I will consider the institutional mechanisms and approaches to reviewing required to support the production of evidence for use as ‘public goods’; where the key concepts were agreed, and understood in advance (Model 1: MHPSS review) and where the conceptual issues were theoretically engaged with during the review (Model 3: PYD review). Both reviews, commissioned through competitive systematic review funding programmes, were designed to answer more than one review question for international audiences (see table 3.1). The systematic review on mental health and psychosocial programmes for people affected by humanitarian emergencies was one of seven reviews commissioned by “The Humanitarian Evidence and Communications Programme” (HEP); a partnership between Oxfam and the Feinstein Centre at Tufts University, externally funded by Humanitarian Innovation and Evidence Programme at DFID. The Public Health Research (PHR) programme, which forms part of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), is interested in generating and using evidence synthesis on the impact and acceptability of non-NHS interventions seeking to improve health outcomes. They funded a systematic review on the effectiveness and delivery of Positive Youth Development (PYD) on substance use, violence and inequalities.

Table 3.1 Overview of reviews

| Review context | Model 1: Mental health and

psychosocial programmes |

Model 3: Positive youth

development programmes |

| Funder | DFID | NIHR |

| Review programme | Tufts-Feinstein and Oxfam

Humanitarian review programme |

Public Health

Research (PHR) Programme |

| Jurisdiction | International | International |

| Review aims |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Stakeholder involvement | Yes: Mental health humanitarian aid practitioners and policy advisors. | Yes: Public health specialists working in policy settings |

| Review team composition | 3 experienced reviewers;

1 topic expert 1 Information specialist |

4 experienced reviewers;

2 topic experts 1 Information specialist |

3.2.1 Vision: generalisable evidence to inform common decisions

Each of the reviews presented in this chapter were commissioned to ensure they produced evidence for policymakers facing similar decisions, across a range of contexts, making the need for generalisable and widely disseminated evidence a priority. Engaging with a broad stakeholder base was a feature throughout the review process, to ensure they maintained their broad appeal and to support greater dissemination and uptake of findings. To produce generalisable evidence that would meet internationally recognisible markers of quality we drew on standardised approaches to reviewing quantitative and qualitative evidence currently established in the field. Engagement with policy issues and the structures and procedures conducive to the production of “public good” reviews are explored in the following sections.

Figure 3.2: Key features of reviews for use as ‘public goods’

3.3 Harnessing motivations to achieve public goods review

3.3.1 Producing evidence for the humanitarian sector in international development

The initial demand for generalisable evidence was ascertained by funders and by reviewers, via engagement with a range of stakeholders potentially interested in using the review findings. The decision to commission a review on MHPSS was decided by the HEP team after consulting a survey on topics requiring evidence synthesis in the humanitarian sector, via conversations with researchers, policymakers, and practitioners, and by drawing on results from the Evidence Aid priority-setting exercise (EAPSG, 2013). A similar call for a systematic synthesis of the MHPSS evidence-base was also made in an scoping exercise on health interventions in humanitarian crises commissioned by ELRHA (Blanchet et al. 2015).

Deciding to apply for the MHPSS review was motivated by several academic factors. Firstly, it would build on our experience of conducting and building capacity to produce systematic reviews in international development and expand our portfolio in this area (e.g. Dickson et al. 2012, Birdthistle et al. 2011, Stewart et al. 2010). It with a previous funder (DFID) but with a new institutional partner, Oxfam & Feinstein Centre.

Secondly, the guidance note on evidence synthesis in the humanitarian sector reflected similar philosophical and epistemological approaches to reviewing. For example, the need to communicate accessible review findings to policymakers, ‘with the ultimate goal of improving humanitarian policy and practice’ (Oxfam & FIC 2015, p.1), the value of mixed methods reviews and the potential of qualitative evidence synthesis in achieving that goal, and the likelihood that review teams would need to address methodological challenges, such as engaging with grey literature, low quality evidence, and contextualising review findings. These and other points made in the call indicated that there would be a ‘good match’ with our own thinking and experience of reviewing in international development. Thirdly, having recently graduated as an integrative psychotherapist it would also provide an opportunity to apply practitioner topic knowledge to a field relatively new to evidence synthesis, with collaborators interested in building policy and practitioner research awareness.

In aligning the scope for the Oxfam review we stayed close to the broad parameters set out in the funding call. However, it was difficult to ascertain the HEP/DFID priorities in full. For example, if they were interested in MHPPS programmes delivered to people affected by any type of humanitarian emergencies, from any geographical context, and of any age. Thus, we delayed making a call on the scope of review until we had further engagement with stakeholders and a better sense of the available literature.

The first indication of whether there was alignment in our thinking about the review and potential users of the review occurred when we were shortlisted and invited to provide feedback on the proposal. For both reviews, funders considered the proposal to be strongly in line with their criteria but had some additional queries. Addressing those queries via a formal written response provided an opportunity to ‘correct’ or clarify any ‘misalignment’. The MHPSS review also requested a telephone meeting to discuss our responses, providing the first opportunity to build a collaborative working alliance with them. Further aspects of the research design emerged when we engaged with policy and practice issues (see section 3.xx below).

3.3.2

Conducting a priority setting exercise prior to commissioning new research, is now a ‘well recognised mechanism’ supporting the production of useful evidence (Cooke et al. 2015 p.2). Government funding bodies such as the NIHR operate with a fixed set of resources and therefore need to set priorities to ensure research production is in alignment with current needs and demands for evidence in the UK. The priority setting approaches adopted by the NIHR continue to evolve to ensure they are inclusive in the views they elicit and accurately reflect priority areas (Noorani, et al. 2007, Kelly et al. 2015). Alongside ‘themed’ calls for research, informed by NIHR priority setting exercises, the Public Health Research (PHR) programme also allows the opportunity for researchers to identify gaps in the evidence-base, and present a case for research determined to be in alignment with stakeholder priorities. The PYD review was commissioned under this ‘researcher-led’ funding stream in 2013. At the time, the coalition government had produced its vision for children and young people in the ‘positive for youth’ policy agenda and had committed to funding positive youth development programmes in the UK. Although UK policy and PYD programmes are interested in reducing health inequalities in young people, the evidence for PYD programmes was out-of-date and there was a lack of cost-effectiveness evidence. Dialogue with policy stakeholders, such as the Head of Children and Young People’s Health Improvement Team at the Department of Health, indicated an interested in using finding from a systematic review on the health effects of Positive Youth Development. Similar interest was also garnered from the Deputy Director of the national team for Children, Young People and Families at Public Health England. This preparatory work focused on identifying a need for evidence at a national policy level harnessed policymakers’ motivation to be involved throughout the review process and to use the findings once the review was completed. Taking on board the NIHR’s commitment to inclusive approaches to stakeholder involvement young people were also consulted to determine their interest in the shape of the review (discussed further in the chapter).

I was invited to lead on the day to day running of the positive youth development review I was keen to take up this offer as it also reflected my professional and academic interests. Firstly, it also provided an opportunity to gain experience of producing a mixed methods public goods review for a funder new to me (NIHR), reflected previous research interests in youth work (Dickson et al. 2013, Thomas et al. 2008) and provided an opportunity to work closely with stakeholders and lead a qualitative evidence synthesis, building on past experiences (Hurley et al. date, Dickson et al. 2008).

.

Move somewhere – to engagement

The criteria set out in the funding call indicated that the design of both reviews needed to be in alignment with producing credible evidence for use by multiple audiences (e.g. as public goods) to address common problems. Thus, during the proposal writing stage, it was judged that to be of benefit to the field solely undertaking an aggregative synthesis, which tested theory using empirical observations of the effectiveness of programmes was unlikely to be sufficient. Instead adopting a mixed methods approach which sought to aggregate and ‘configure’ findings was judged to be more beneficial to a range of users and provide a greater contribution to the evidence-base. In both reviews, this meant identifying studies with quantitative data that could provide evidence on effectiveness of programmes and qualitative or quantitative data on the characteristics of participants or contextual factors potentially acting as barriers or facilitators to programme implementation, and to use hypothesis generated from configurative synthesis as an analytical tool for any observed heterogeneity in outcome effects.

Both reviews devised a dissemination plan during the protocol to affirm commitment and need to reach a broad audience base to support shaping and uptake of the review findings. Dissemination plans included more conventional approaches such as publishing the findings in academic journals, at conferences, organising a launching of the findings (PYD review) as well as capitalising on new modes of dissemination, such as through social media and blogs (MHPSS review). For transparency and dissemination purposes we also outlined our plan to publish protocols on Prospero (the international prospective register of systematic reviews), technical reports, and plain language summaries.

[1] A partnership between Centre for Research on Families and Relationships, the Scottish Government, two third sector intermediaries (Children in Scotland and Parenting Across Scotland), and West Lothian Council.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Politics"

Politics refers to the way in which decisions are made on behalf of groups of people. A politician will use their position to suggest and support the creation of new policies and laws, before a group of politicians will come together to debate the creation of such policies and laws.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: