Social Prescribing to Support the Treatment of Mild Anxiety and Depression in University Students

Info: 9779 words (39 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Tagged: EducationMental HealthPsychiatry

Exploring social prescribing as a means to support the treatment of mild anxiety and depression in undergraduate university students

Abstract

Background: Anxiety and depression affect the lives of many UK citizens, particularly young people. Social prescribing is a relatively new service that aims to improve patients physical and mental wellbeing by offering them a variety of non-clinical social activities as a form of treatment for their anxiety and/or depression. Currently there is little evidence available to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of social prescribing, especially in the long-term.

Objectives: To gather views of University of Bath students on social prescribing and determine whether there is a correlation between these views against gender, age or department of study. Also, to investigate what would motivate students to engage with this service if it was implemented at the University.

Method: Data collection adopted a mixed method approach. Qualitative data was coded using an inductive, iterative approach to thematic analysis. Quantitative data was collected via an online questionnaire using SurveyMonkey and then inputted into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software for analysis.

Results: The qualitative data demonstrated that the majority of students lacked any prior knowledge of social prescribing. Students suggested it could be a better treatment alternative to medication, however it may be challenging to offer a range of activities as part of this service that can cater to all individuals. The quantitative data found a positive association between gender and experiencing anxiety (p=0.019), with more females reporting feelings of anxiety than men. No positive associations were found between views on social prescribing as well as experiencing a mental health issue with age, gender, or department.

Conclusion: Findings show that although students were aware of the student services provided by the university, the prevalence of anxiety and depression in undergraduate students is still high. Social prescribing could be a promising scheme for supporting students with mild cases of anxiety and depression. However, further research is required to determine its clinical effectiveness in young people and whether it would be a cost-effective service.

1. Introduction

- Background

Mental health problems are a growing public health concern, where it is estimated that approximately one in four people in the UK will experience a mental health condition at some point in their lifetime [1]. Young people especially are vulnerable to experiencing mental illnesses, with approximately one in four university students reporting having experienced a mental health problem of one type or another whilst at university [2]. Depression and anxiety are by far the most commonly reported mental health conditions. Of those who suffer, 74% have anxiety related problems and 77% have depression related problems [2]. Anxiety and depression are highly prevalent amongst university students and the effects can often be obstructive. Approximately 6 out of 10 students believed their stress levels were having a negative impact on their day to day lives [2], indicating a definite need for intervention in order to improve the general mental health of university students nationally.

The prevalence of mental health between the genders is also of notable reference. In 2010, the global annual prevalence of major depression was higher in woman than in men [3] at 5.5% and 3.2% respectively, representing a 1.7-fold greater incidence in women.

Current practice for mild cases of anxiety and depression implements self-help groups, exercising and talking therapies as the most effective forms of treatment, whilst moderate to severe cases may consider prescribing antidepressants [4].

Social prescribing is a relatively new and expanding service, which aims to help patients with social, emotional, or practical needs by referring them to non-clinical community services [5]. This includes activities such as volunteering, gardening clubs, swimming, self-help groups, exercise and dance classes amongst many others [6]. Social prescribing recognises that a person’s health is influenced by a variety of social, economic and environmental factors, and thus adopts a holistic approach in order to address people’s needs [7]. It also encourages individuals to become more involved with and take better control of their own health. Ultimately, social prescribing looks to offer long-term support for people, for example, improving employment prospects, better education and better social relations. There is an increasing recognition of the potential of social prescribing to help achieve the ambitions of the Five Year Forward View and of sustainability and transformation partnerships (STPs) to support people in managing their own care [5]. Moreover, social prescribing may be deemed an effective tool in achieving the Five Year Forward View, dependent on the supporting evidence.

Interest in social prescribing has largely expanded over the past decade, with the UK currently running 100 schemes, over 25 of which are in London [7]. There is emerging evidence to suggest that social prescribing can have a positive effect on health and well-being outcomes, with improvements on one’s mental and general wellbeing as well as reduced levels of anxiety and depression [7]. One study at the University of West England (UWE) into social prescribing found improvements in anxiety levels and one’s quality of life [8].

Another study scheme in Rotherham conducted by Sheffield Hallam University found evidence to suggest that social prescribing schemes may also lead to a reduction in the use of NHS services, including A&E attendances and GP appointments [9]. A non-systematic review studying arts on prescription found evidence to support the idea that active involvement in creative activities can promote well-being, quality of life and health [10].

| Study objective 1: | To explore using focus groups what undergraduate students and staff at the University of Bath know and think about social prescribing. |

| Study objective 2: | To identify from the focus group data what the key issues are for students in relation to social prescribing and use this to develop a questionnaire that we will ask students from a range of discipline areas to complete. |

| Study objective 3: | To investigate if and how students’ views vary on social prescribing, depending on their degree, age and gender. |

| Study objective 4: | To determine what would be the key factors that would motivate the students at the University of Bath to engage with social prescribing. |

| Study objective 5: | To develop a guideline and identify possible services that could be implemented by the Students Union for the inclusion of social prescribing as a means to support students who are living with mild anxiety and depression. |

Nevertheless, there are still few robust systematic reviews currently available that investigate the effectiveness of social prescribing. Many studies included within these systematic reviews are of poor quality, with small numbers, no control group, short follow up times and differences in outcomes measured. Much of the data is qualitative, and is reliant on personal cases and self-reported outcomes; and it is understandable that outcomes can be difficult to measure in such complex interventions.

There is currently no NICE guidance on social prescribing, but some of their published guidelines include recommendations for interventions that could be used in a social prescribing programme. For instance, the NICE Depression: Evidence Update April 2012 includes some additional support for the existing recommendation for physical activities programs [11][12].

Social prescribing has been shown to be beneficial for those suffering from social isolation [7]. One study of 721 students across three universities reported 60.2% of the participants experienced loneliness whilst at university [13], often due to lack of emotional and social support. With social isolation being so prominent amongst university students, it comes to question whether social prescribing could be a promising intervention for students to overcome these feelings of social isolation issue and low mood. With no apparent research being published with regards to the effectiveness and acceptance of social prescribing in university students, this research study hopes to provide some new evidence on the need for and potential use of social prescribing at the University of Bath.

1.2 Aims of the study

The aim of this study is to explore perspectives of students at the University of Bath with regards to the use of social prescribing as a means to help support students with mild anxiety or depression. Views of staff members were also investigated. Research collected from this study can help determine which, if any, social activities would be beneficial for students who were potentially referred on to this service as well as establish the logistics of how social prescribing would operate at the university. The specific objectives of this research were:

2. Methods

Data was collected in two primary phases: firstly, through conducting focus groups (FG) and secondly from an online questionnaire. Using a mixed-method approach for this study allowed for both quantitative and qualitative data to be collated and analysed in order to reach the conclusions drawn for this study.

2.1 Ethical considerations

Ethics approval for this research study was attained by completion of an Ethical Implications of Research Activity (EIRA) form prior to the study being carried out. This was required by the university’s pharmacy undergraduate research project committee. Ethical considerations were made for both the qualitative and quantitative data collection.

2.1.1 Recruitment of participants

Participants were selected only if eligible, ie. if they were a current undergraduate student or staff member at the University of Bath. Bias was excluded by recruitment of participants from a range of degree courses and faculties as well as from different year groups. Focus groups were divided by year group (years one to four) and a fifth one was held for staff members. The online survey was primarily distributed via social media platforms such as Facebook, as well as a QR code which was printed and displayed around campus so that students could simply scan the code to take them directly to the survey web link. The survey was also circulated to staff members by emailing the heads of teaching to then distribute it onto the rest of their department.

2.1.2 Consent

Involvement in this research project was optional and participants had the option to leave the study at any time if they wished. Incentives were used to help encourage the recruitment of participants for focus groups and participation in the online survey, but these were not large enough to be coercive or pressurise people to take part. Focus group participants were told prior to starting that the session was to be recorded by two audio-digital Dictaphones. Written consent was obtained once participants had read through the participant information sheet and consent form, before any audio recordings were made. The groups were all made aware that they could withdraw their consent at any stage for whatever reason without penalty. Survey respondents provided implied consent by means of completion of the survey.

2.1.3 Confidentiality

As anxiety and depression can be sensitive topics for some, FG participants were asked to not share any of the thoughts and opinions shared by others in the discussions. Participants were also assigned random numbers in each FG which were used for any referencing rather than individual names, ensuring anonymity. Recordings of the FGs were also erased once they had been transcribed by the researchers. People who completed the survey were not identified by name, but provided an email address if they wanted to enter the prize draw which was not compulsory. All participant information was stored on password protected electronic devices of the researchers. Confidentiality of participants was maintained through the collection, analysis and results of the report, as per the requirements of The Data Protection Act (1998), Good Clinical Practice and University policy regarding Data Protection.

2.2 Qualitative phase: Focus Groups

2.2.1 Recruitment of participants

Participants for the FGs were recruited from University of Bath undergraduate students between first and fourth year as well as staff; with a total of five FGs carried. Participants were recruited on a voluntary basis and those who showed interest were selected dependent on year group and faculty to ensure a wide range of participants from different courses.

Students were recruited by means of advertising the FGs with posters which were designed by the researchers and displayed around the university campus. Staff were recruited by Dr Andrea Taylor personally asking five members of staff in various departments to participate, to which they all agreed. Incentives were used to encourage participation, which consisted of a £10 Amazon voucher for all partakers. The qualitative research aimed to recruit approximately 8 participants for each FG.

2.2.2 Procedure

An email account was created specifically for the research project which was used to send out further information on the FGs (of that which was displayed on the poster) to those who showed interest. This included a participant information sheet [see appendix A] and a topic guide [see appendix B] for them to read prior to actually commencing the FGs. The participant information sheet provided the students and staff with a concise summary of why this research was being done, as well as details of the time and location their FG would take place. The topic guide gave them further information of the matters that would be covered in the sessions. The guide was developed to cover the aims of the research study, examining views on social prescribing, anxiety and depression and potentially introducing social prescribing to the university.

When participants attended their designated FG, they were provided with another copy of the information sheet and topic guide as well as a consent form [appendix C] which they read and signed before commencing the session, thus providing written consent for their participation in the study.

Two pilot studies were carried out the week before the actual FGs took place which helped to determine the quality of the topic guide and make improvements where necessary. As there were only two pilot FGs, the groups contained students from various years as well as two members of staff attending the second pilot group. Participants were asked at the end of the pilot studies to provide any feedback on how the session could be improved, which included using more probing and open-ended questions in order to gain more detailed responses.

Once the topic guide had been amended, five semi-structured FGs were conducted which involved one facilitator and one co-facilitator in each group. The facilitator was responsible for running the session using the structure depicted in the topic guide whilst the co-facilitator helped to transcribe the session.

The participants were provided with light refreshments during the session and given a £10 amazon voucher at the end as a means of thanking them for their contribution to the study.

2.2.3 Analysis

All of the focus groups were recorded with a Dictaphone as well as partially transcribed by the co-facilitator. This helped to identify which participant was speaking at a particular time so that the entire FG could be transcribed in full. All of the research members were responsible for transcribing one of the five FGs carried out which helped to familiarise themselves with the data [14]. See appendices D, E, F, G and H for full transcripts.

The transcribed data for the staff and one of the student FGs was then coded using an inductive, iterative approach to thematic analysis. The initial coding was completed by highlighting relevant sections of the transcripts that were applicable to a particular code, to make one master coding framework [appendix I]. Braun & Clarke (2006) define inductive analysis being “data-driven”, where the themes emerge from reading over the transcripts with no pre-existing coding frame in mind [15].

The codes were then analysed by the whole research team and grouped together into potential themes and sub-themes [appendix J] that were common amongst all of the FGs. Some of the original themes were merged whilst others were completely removed. Eventually the themes were narrowed down to create two main themes with three sub-themes each (see Section 3.1).

The patterns and themes emerged which were utilized to assist in the development of an online survey.

2.3 Quantitative phase: Online survey

The qualitative data was collected using a separate online survey for students [appendix K] and staff [appendix L].

2.3.1 Recruitment of participants

Advertisement for the online survey was carried out primarily through the means of social media, particularly Facebook, where a brief description of the survey with an accompanying web link were posted on numerous pages affiliated with the University of Bath. A QR code was also created for the student survey then printed and displayed around campus which allowed students to simply scan the code with a mobile device that would direct them straight to the survey for them to complete. The Heads of Departments were also all emailed and asked to distribute the surveys to undergraduate students and staff within their faculty.

2.3.2 Survey development

Both surveys were developed using SurveyMonkey. A separate questionnaire was used for staff and students to allow for different areas to be explored as not all questions asked to students were applicable for staff and vice versa.

The surveys were initially piloted by some members of staff within the pharmacy department and some undergraduate students in order to identify any potential problems with its structure and design as well as assess how long on average they took to complete. It was also important to ensure all vocabulary used would be comprehensible by the target audience and that the survey did not include any leading questions that could hence effect people’s responses. Feedback was received and adjustments made so that both surveys took on average ten minutes each to complete.

The surveys were both launched and kept open for three weeks. Incentives were used to encourage the participation of undergraduate students, which included the opportunity to win one of:

- 23 x £10 Amazon vouchers

- 2 x £25 Amazon vouchers

- 1 x £50 Amazon voucher

To have the chance to win, participants were required to input an email address once they had completed the survey, which was optional.

2.3.3 Analysis

The data was collected by SurveyMonkey and was exported into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software to be analysed in depth. SurveyMonkey offers SPSS integration for response data, excluding the incidence of human error occurring from inputting data manually.

3. Results

See appendix M for details of the work log for this research study.

3.1 Qualitative findings

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the qualitative data collected from the FGs, with an inductive, iterative approach. Themes were identified at a semantic level as themes were identified through their obvious meaning and not looked further into. The data was arranged into 2 key themes; (1) social prescribing and (2) anxiety & depression.

3.1.1 Social prescribing

i) Pathway

Participants of the FGs discussed if they believed social prescribing could be of benefit to undergraduate students at the university. This involved investigating the actual means necessary for such a service to operate. Themes identified included:

- Advertising/ promotion of the service: Caution should be made as to how the service is promoted as certain phrasing could be unintentionally interpreted as being patronising when dealing with anxiety and depression (Box 1.1)

- The range of activities that should be offered: Some participants believed sports were the ideal method to help engage people in social interaction (Box 1.2). Others believed that the activity should be more tailored the individual and their personal interests (Box 1.3).

- How it should be funded

- How those who used the service would be monitored for improvement: One’s mental health can present as a challenge to assess as different people present in different ways (Box 1.4), thus careful monitoring was suggested to ensure the service was actually beneficial to those using it.

- Stigma around the service and mental health: Using the term “prescribing” could medicalise the service (Box 1.5) and could deter people from using it as it implies that they have a condition or ‘illness’ that requires medical treatment.

ii) Benefits

The majority of students and staff within the FGs could see various potential benefits of using social prescribing as a means to help support students with mild anxiety and/or depression. This mainly revolved around its encouragement in engaging people to have more social interaction (Box 1.6), where people have the opportunity to meet others who may be experiencing similar issues and therefore reduce any feelings of social isolation. Other benefits included physical health, where social prescribing activities involved participating in sports or games (Box 1.7).

iii) Limitations

Although several benefits were discussed within the FGs, a number of limitations also arose. Some were not convinced that it would be an effective treatment, particularly as it is a relatively new service and has not been implemented on a large scale. One participant highlighted that all individuals varied in how they experienced anxiety and depression and thus it may not be an appropriate treatment for everyone (Box 1.8). It was also widely discussed that joining a social prescribing service may be quite daunting for the person involved as it is pushing them out of their comfort zone which could be considerably intimidating and hence prevent them from engaging with social prescribing (Box 1.9). One of the staff participants highlighted that it was important for the service to be offered to people in a non-threatening manor in order to encourage their participation (Box 1.10). There were also concerns regarding how the service would be funded, particularly if targeted towards university students as many students are already under financial pressures so may not be able to afford this service if it had to be funded by the individual (Box 1.11).

3.1.2 Anxiety and depression

i) Perceptions of anxiety and depression

The different focus groups offered a wide range of views with regards to anxiety and depression, with one student sharing their own personal experience with mental illness, whilst another participant strongly believed mental illnesses were due to weak character (Box 2.1). Most people were of the belief that society were not always accepting of mental illness (Box 2.2), but this was improving with time as the public are becoming increasingly aware of the prevalence of mental illness (Box 2.3). Participants also respected that anxiety and depression were complex conditions which present differently in various people, as people show different symptoms and deal with their condition in different ways (Box 2.4)

ii) Triggers

There was a clear, common theme throughout the focus groups that almost all the participants believed that university life played to at least some extent in triggering anxiety and depression in undergraduate students. This comprised of various aspects regarding university life, particularly students’ workload (Box 2.5), as many students believed that the university curriculum alongside coursework assignments and exam stress all totalled to cause students a great deal of stress that could further result in poor mental health (Box 2.6). Other aspects of university life included; moving away from home (Box 2.7), feeling socially isolated, and social pressures. It was a big significance that both students and staff in the focus groups agreed that the university environment can be challenging for new students (Box 2.8). However, where students mainly believed that workload had a big impact on poor mental health in students, staff put this down to social pressures and merely entering adulthood (Box 2.9).

iii) Management and support

The students of the FGs were generally aware of some of the range of services that the university provided for students experiencing stress and required support; including student services, nightline, peer mentors and personal tutors (Box 2.10). However, some students were hesitant on how effective these services are in helping students with anxiety and/or depression (Box 2.11). The staff FG discussed that they believed many students actually did not recognise the signs of anxiety and depression (Box 2.12) which may prevent them from seeking support in the first place. One of the staff participants suggested that many students may try to manage their anxiety and/or depression themselves rather than seek external help which is not effective for them and may cause them to only seek help later when their condition becomes more serious (Box 2.13).

Box 1: Social prescribing

1.1 “How they phrase it can sound quite patronising” (FG1 F2)

1.2 “Social, non-competitive team sports” (FG3 F4)

1.3 “Treatment must be personalised” (FG1 F2)

1.4 “Hard to track progress” (FG3 F4)

1.5 “I’ve got a little concern about the stigma that giving it a quasar medical term.” (Staff FG M4)

1.6 “Meet new people with similar worries/problems” (FG2 M5)

1.7 “Body feels disgusting and you play and you just feel better after and mentally release” (FG2 M6)

1.8 “I don’t think it will work in all types of anxieties” (FG3 M1)

1.9 “If feeling really depressed and someone told you to go out to be social you might not really want to” (FG4 F1)

1.10 “You need to get out to those people that don’t do it, in a non-clinical way and a non-threatening way I suppose, that’s the challenge” (Staff FG M2)

1.11 “Joining fees is a big thing” (FG1 M2)

1.12 “I think people experience these conditions because they’re mentally weak” FG3 M6

1.13 “People try to hide it and not accept it”

1.14 “I sense so much more positive acknowledgement of these [anxiety and depression] broadly in society these days” Staff FG P4

1.15 “Everyone deals with anxiety and depression differently”

1.16 “Added stress of your degree”

1.17 “Curriculum shapes the environment fundamentally and will create triggers”

1.18 “University is a new environment that they may not be comfortable with”

1.19 “Well, we structure their lifestyles basically, the entire semester, pattern and structure so we are in control of lots of things and in addition to the fact that they are going through a biological and psychological process of transition at that stage in life to adulthood if you like and we’ve uprooted them under a different institution which is really quite dangerous.” (Staff FG P4)

1.20 “Work has helped, it has been the one thing that is holding them together and that’s the only one thing that they can focus on because it’s structured and they know when they have to turn up to their sessions and they know what coursework they have got to hand in.” (Staff FG P3)

1.21 “Nightline, personal tutors, student services, resident tutor”

1.22 “More can be done to help people with anxiety”

1.23 “I think a lot of people don’t actually recognise the signs” (Staff FG P5)

1.24 “I think it’s possibly that they do try and manage it themselves and unfortunately perhaps not going to seek help early enough when easier interventions would support them. The time that it is coming out is the stage where you know it’s a bit more serious.” (Staff FG P3)

Box 2: Anxiety and depression

2.1 “I think people experience these conditions because they’re mentally weak” (FG3 M6)

2.2 “I think most people try to hide it” (FG1 M2)

2.3 “I sense so much more positive acknowledgement of [anxiety and depression] broadly in society these days” (Staff FG M4)

2.4 “Everyone deals with anxiety and depression differently” (FG1 M2)

2.5 “Added stress of your degree” (FG1 M4)

2.6 “Curriculum shapes the environment fundamentally and will create triggers” (Staff FG M4)

2.7 “University is a new environment that they may not be comfortable with” (FG1 M1)

2.8 “Well, we structure their lifestyles basically, the entire semester, pattern and structure so we are in control of lots of things and in addition to the fact that they are going through a biological and psychological process of transition at that stage in life to adulthood if you like and we’ve uprooted them under a different institution which is really quite dangerous.” (Staff FG M4)

2.9 “Work has helped, it has been the one thing that is holding them together and that’s the only one thing that they can focus on because it’s structured and they know when they have to turn up to their sessions and they know what coursework they have got to hand in.” (Staff FG M3)

2.10 “Nightline, personal tutors, student services, resident tutor” (FG2 M1)

2.11 “More can be done to help people with anxiety” (FG1 M4)

2.12 “I think a lot of people don’t actually recognise the signs” (Staff FG M5)

2.13 “I think it’s possibly that they do try and manage it themselves and unfortunately perhaps not going to seek help early enough when easier interventions would support them. The time that it is coming out is the stage where you know it’s a bit more serious.” (Staff FG M3)

3.2 Quantitative findings

3.2.1 Participants

The only inclusion criteria for completing the online survey was that the participant must be a current undergraduate student at the University of Bath (for the student survey) or a current member of staff (for the staff survey). Participants were not excluded based on age, course, year of study or whether they were a full or part-time student/member of staff.

3.2.2 Demographic Characteristics

| N | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 202 | 48.79 |

| Female | 211 | 50.97 | |

| Age | <18 | 5 | 1.21 |

| 18-19 | 187 | 45.17 | |

| 20-21 | 138 | 33.33 | |

| 22-23 | 76 | 18.36 | |

| >23 | 8 | 1.93 | |

| Degree | Accounting and Finance | 9 | 2.17 |

| Architecture | 8 | 1.93 | |

| Biosciences | 25 | 5.04 | |

| Business and Management | 23 | 5.56 | |

| Chemical Engineering | 78 | 18.84 | |

| Chemistry | 15 | 3.62 | |

| Civil Engineering | 7 | 1.69 | |

| Economics | 12 | 2.90 | |

| Electronic and Electrical Engineering | 11 | 2.66 | |

| Integrated Mechanical and Electrical Engineering | 7 | 1.69 | |

| Languages | 3 | 0.72 | |

| Mathematical Sciences | 37 | 8.94 | |

| Mechanical engineering | 27 | 6.52 | |

| Natural Sciences | 12 | 2.90 | |

| Pharmacy and Pharmacology | 73 | 17.63 | |

| Physics | 12 | 2.90 | |

| Politics | 9 | 2.17 | |

| Psychology | 14 | 3.38 | |

| Social Work | 1 | 0.24 | |

| Sociology and Social Policy | 11 | 2.66 | |

| Sport-Related Studies | 20 | 4.83 | |

| Faculty | Science | 174 | 42.03 |

| Humanities & Social Sciences | 58 | 14.01 | |

| Engineering & Design | 138 | 33.33 | |

| Management | 44 | 10.63 | |

| Year of Study | Year 1 | 134 | 32.37 |

| Year 2 | 89 | 21.50 | |

| Year 3 | 74 | 17.87 | |

| Year 4 | 117 | 28.26 |

527 students started the student survey, of which 414 completed it in full (79% completion rate). There are currently 13,051 undergraduate students at the university so for a confidence level of 95% and 5% margin of error, 374 students were required to complete the study. Therefore, this is an acceptable sample base, however this is still a limited sample so caution was taken when extrapolating responses to represent the entire undergraduate population. Demographic characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic data for the student survey

There was a relatively even number of responses from male and female participants, with 202 male respondents (48.79%) and 211 females (50.97%). Responses were gathered from students of various departments, particularly pharmacy &

pharmacology (17.63%), chemical engineering (18.84%) and mathematical sciences (8.94%), representing a high number of responses from those doing a science degree.

104 members of staff began the staff survey, of which 64 completed it fully (62% completion rate). Again, for a confidence interval of 95% with 5% margin of error, 298 staff members would have had to complete the survey in order to be a representative sample. Thus, the results of the staff survey cannot be used to represent general views of all staff at the university.

Tables 2 and 3 show further detail on the outreach of the study with response rates for the student and staff surveys.

Table 2: Response rates for student survey

| Sources | No. of replies | Total no. of students who saw/ were sent | Response rate |

| Social media (Facebook) | 203 | 4287 | 4.7% |

| 106 | 1168 | 9.% | |

| Word of mouth from researchers | 105 | 562 | 18.% |

| Other | 113 | 628 | 18% |

Table 3: Response rates for staff survey

| Sources | No. of replies | Total no. of staff who saw/were sent | Response rate |

| Social media (Facebook) | 23 | 143 | 16% |

| 68 | 584 | 12% | |

| Word of mouth from researchers | 5 | 28 | 18% |

| Other | 8 | 82 | 10% |

The survey was used to help investigate study objectives 3 and 4 (see section 1.2); to investigate if and how students’ views vary on social prescribing, depending on their degree, age and gender, and to determine what would be the key factors that would motivate the students at the University of Bath to engage with social prescribing.

3.2.3 Anxiety and depression in the student population

In order to determine how prevalent anxiety and depression are amongst students at the university, students were asked a series of questions regarding their own personal experiences with mental health.

Students were asked to rate how often they felt down on a scale of ‘never’ to ‘always’. 52.4% (n=217) of respondents answered ‘sometimes’, whilst 27.1% (n=112) answered often and 2.4% (n=10) answered all the time.

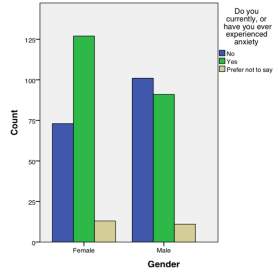

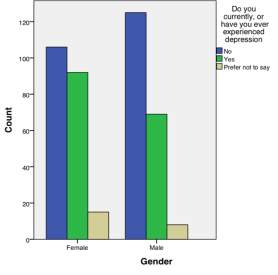

Students were also asked whether they had personally experienced anxiety or depression. They were given the option ‘prefer not to say’ as it was understandable that some respondents may not wish to disclose this information, despite answers being anonymised. Results for this in comparison to gender can be seen in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1 – Responses to ‘Do you currently of have you ever experienced anxiety?’ in males and females

Figure 2 – Responses to ‘Do you currently of have you ever experienced depression?’

There was a significant association between males and females in whether they currently or have ever experienced anxiety which was discovered using a Pearson-Chi Squared test (x2=11.76, p=0.019). Female respondents were more likely to have experienced anxiety with only 34.3% (n=73) having never experienced anxiety as opposed to males where 49.8% (n=101) had never experienced it.

When investigating depression, more females than males also answered that they had experienced it at some point (see Figure 2), but the difference in gender was not deemed significant (x2=8.266, p=0.082).

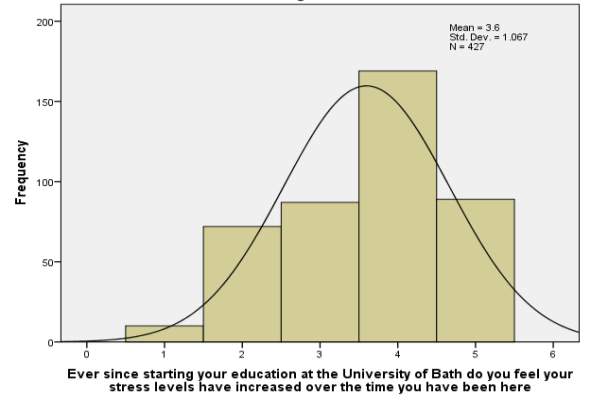

Respondents were asked whether they believed their stress levels had increased since starting university, using a rating scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ (figure 3). The majority of students rated ‘agree’ (40.1% n=166), with 20.3% (n=84) answering with ‘strongly agree’.

Figure 3 – Responses to ‘Ever since starting your education at the University of Bath do you feel your stress levels have increased over the time you have been here?’ (1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree)

3.2.4 Views on social prescribing, according to degree, age and gender (study objective 3)

Respondents were asked a number of questions to explore their views on social prescribing.

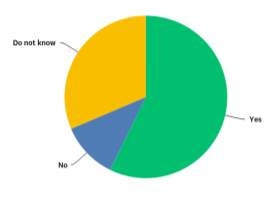

Students were asked whether they thought the term ‘social prescribing’ was an appropriate description of the service it provides (see Figure 4). Although the majority (57.5%) voted ‘yes’, 31.4% answered ‘do not know’ and 11.4% answered ‘no’. Respondents who answered ‘no’ were asked to suggest a term they believed would be more suitable. Answers included: wellbeing consultation, social guidance, social development, wellbeing guide and mood support. No statistical significances were found in this question with regards to gender, age or department.

Figure 4 – Responses to ‘Do you think the term social prescribing describes this service appropriately?’

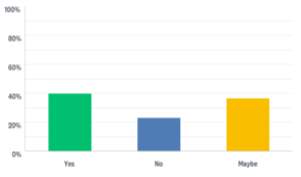

Students who had answered yes to having experienced anxiety and/or depression were then asked whether they would have liked the opportunity to take part in social activities as part of their treatment. 160 students responded to this question, results can be seen in Figure 5. The majority (40.0% n=64) answered yes, 23.1% (n=37) answered no, and 36.9% (n=59) answered maybe. Again, no significant associations were found for this question with regards to the age, gender or department of respondents.

Figure 5 – Whether students would have liked to have been offered social prescribing for treatment of their anxiety and/or depression

3.2.5 Motivators to engage with social prescribing (study objective 4)

To investigate what would influence a person to take part in social prescribing, several questions were asked in the student survey on what might encourage them to participate, what might limit this and how the service should be provided at the university.

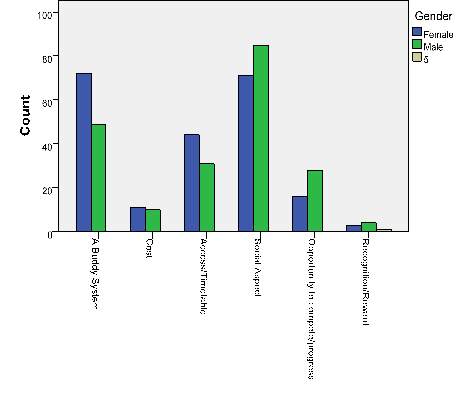

Figure 6 – Responses to ‘What would be the biggest motivation for you to join a club if it was recommended to you as part of social prescribing?’ in males and females

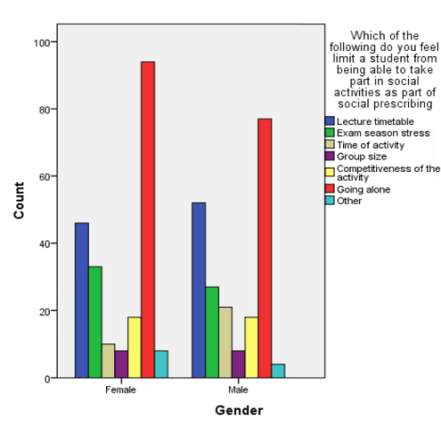

Figure 7 – Responses to ‘Which of the following do you feel limit a student from being able to take part in social activities as part of social prescribing?’ in males and female

The survey asked respondants what would motivate them to join a club if it was recommnded as part of social prescribing, and were asked to pick one out of six available options (see Figure 6). This was compared between male and female respondents. ‘Social aspects’ ranked highest for males and second highest for females (closely following ‘a buddy system’). Males also ranked ‘having the opportunity to compete/progress’ higher than females (males: 13.5%, females: 7.4%). A chi-squared test showed a positive asssociation between the two variables (x2=63.365, p<0.05).

Respondents were asked who they believed should provide a social prescribing service that would be accessible to students. The majority voted the Student’s Union, which was then followed by an external provider and then by GP’s (see table 4).

Table 4 – Students’ opinion on who should provide a social prescribing service for students

| Student’s Union | External Organisation | GP | Other | |

| n | 294 | 82 | 26 | 12 |

| % | 71.0 | 19.8 | 6.3 | 2.9 |

The survey also looked to explore what students believed may limit people from being able to take part in social activities as part of social prescribing. Figure 7 reveals that the majority of males (37.2%) and females (43.3%) believed that ‘going alone’ would be the biggest limitation, with lecture timetable as the second biggest limitation, and exam season stress in third for both genders. A chi squared test showed no significant association between these gender and limitations for social prescribing (x2=9.149, p=0.690). There was also no significant association when compared to department (x2=121.432, p=0.446).

4. Discussion

4.1 Study findings

Instances of anxiety and depression are not uncommon within university students in the UK, and can rise as a result of workload, balancing various commitments and social isolation. In this study, the majority of student respondents in the survey (51.9%) admitted to having experienced anxiety at some point in their lives, whilst depression was not as common but had still been experienced by 39% of respondents. These statistics rank higher than those which have been reported nationally [2] where one in four university students reportedly experience a mental health issue, which may suggest that the University of Bath has a larger problem with instances of poor mental health in students. However, these results may also be skewed as students with anxiety or depression may have seen the topic of the online survey and been more inclined to respond than students who could not relate to these mental health issues.

Responses also supported the statistics regarding mental health between the genders, as more females reported having experienced anxiety and depression than males did [3]. However, in the qualitative data, it was cited that it was not always clear for someone to identify symptoms of anxiety and depression in themselves or in others and therefore, there may have been even more instances that were not clinically diagnosed and left unnoticed.

Student views regarding social prescribing varied, however the views could not be clearly distinguished according to gender, age or department of study. The quantitative data indicated that a large proportion of participants who reported having experienced anxiety or depression would like to have had the option to engage with a social activity as part of their treatment. However, the data also suggests that participants generally felt that social prescribing sounds too medicalised so an alternative label for the service may be required.

4.2 Implications at the University of Bath

Although the qualitative and quantitative data showed that students had a clear knowledge of the support services currently available to them for any concerns they have with experiencing anxiety and depression, the quantitative data still showed a high prevalence of these conditions. This indicates a need for the university to introduce more effective interventions that are easily accessible to students. Respondents of the student survey voted cost of the activity, timing of the activity and activities consisting of a larger group of people (>15) as the three highest factors that may hinder access to social activities for students with mild anxiety and depression. Therefore, if a social prescribing scheme was to be implemented at the university, it is important to ensure that these factors are taken into account when designing the logistics so that students will be more inclined to commit to this service.

The quantitative data found that 67.6% of students thought GPs should be involved with the prescribing of social activities for mild anxiety and/ or depression. However, students ranked student support services the highest for who they believed should refer students onto social prescribing. Some students commented that they believed there should be multiple points of access to social prescribing, such as through GPs, personal tutors, and self-referral, and it should not be limited to just one method. Moreover, it is clear that students deem easy accessibility to be a key motivator in encouraging involvement with social prescribing.

Another key motivator extracted from the quantitative data was that 29% of respondentsbelieved a ‘buddy system’ would be the biggest motivation for them to join a club if it was recommended as part of social prescribing. The need for a buddy system may be put down to feelings of loneliness and social isolation in students, especially when they first come to university and may not know anyone before they arrive. A recent AXA PPP poll found that 18-24 year olds are four times as likely to feel lonely “most of the time” as those aged over 70 [16]. Loneliness can result in low mood and mental illness, and so although loneliness is most commonly associated with older people, it must not be overlooked in young people. Therefore, if social prescribing was to be implemented at the university, a buddy system appears to be a positive feature that could help diminish feelings of social seclusion.

4.3 Limitations

| Limitation | Explanation and outcome | How it was overcome or could be improved |

| Focus groups did not contain the same number of participants for each session. | The study aimed to get 8 participants per focus group. However, some students did not show up to their designated focus group. | Confirm with the participants 24 hours in advance that they will definitely be in attendance, or to give advanced notice if they can no longer attend. |

| Head of teaching for some departments would not circulate the survey link to students and staff due to university policy. | Less students and staff received the link by email so less responses received overall. Certain departments did send on the email so data is skewed with responses not evenly representing students and staff from all departments. | Other platforms were used to promote the survey, including social media and a QR code posted around campus. |

| Some questions were poorly designed, such as where participants would have to give three options for a question where three may not have actually applied to them. | Participants skipped several questions, with a 79% and a 62% completion rate for the student and staff surveys respectively. | The survey could have been piloted by more students and staff, particularly from departments other than pharmacy to ensure good clarity and logical flow of questions. |

| When the survey was designed, it was not planned how the data was going to be analysed. | Data analysis with SPSS took a considerable amount of time. | Data analysis should have been carefully planned during the process of designing the surveys. |

| Some answers to questions in the survey allowed for options such as ‘don’t know’ and ‘prefer not to say’. | These responses cannot be interpreted for analysis as it is unclear why they chose these options. | Take out options such as ‘don’t know’ where the subject matter is not sensitive or give the option to free text as to why they have put this response. |

| The number of completed responses for the student survey varied on SurveyMonkey (414) and on SPSS (427). | When analysing data, statistic varied slightly between the SurveyMonkey data and that on SPSS even though the SPSS extrapolated data should only have included completed responses to the survey. | Another attempt should have been made to transfer the SurveyMonkey data to SPSS to ensure the total number of responses to analyse was the same or investigated into why they varied in number. |

5. Conclusion

This study has shown the prevalence of anxiety and depression amongst students at the University of Bath is particularly high. More people are becoming increasingly accepting and aware of mental illness and the challenges it entails. However, many people still are not seeking help when they need it. The university currently offers a range of support services for students which are well advertised on campus and online. Current evidence suggests social prescribing can have positive impacts on both mental and physical health, as well as improve social and economic issues. Social prescribing does appear to have potential for university students, particularly as mental health is considerably poor and reports of social isolation are high for this demographic. In order to operate successfully at the university, it is important to offer a range of activities for participants to choose from based on their interests, that are easily accessible and are of low cost for the user to ensure full engagement with the service. Further research on a large scale is required to determine whether social prescribing is clinically effective and cost-effective for undergraduate students.

References

[1] Halliwell E, Main L, Richardson C. The Fundamental Facts: The Latest Facts and Figures on Mental Health. Mental Health Foundation (London, England); 2007.

[2] Aronin S. One in four students suffer from mental health problems. YouGov; 2016. Available from: https://yougov.co.uk/news/2016/08/09/quarter-britains-students-are-afflicted-mental-hea/

[3] Cyranowski JM, Frank E, Young E, Shear MK. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000 Jan; 57(1):21-7.

[4] Devine E. What could STPs learn from social prescribing? NHS England; 2017. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/clinical-depression/treatment/

[5] https://www.england.nhs.uk/blog/what-could-stps-learn-from-social-prescribing/

[6] The Univeristy of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Evidence to inform the commissioning of social prescribing. Available from: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Ev%20briefing_social_prescribing.pdf

[7] The King’s Fund. What is social prescribing? 2017. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/social-prescribing

[8] Kimberlee R. Developing a social prescribing approach for Bristol. Project Report. Bristol Health & Wellbeing Board, UK; 2013.

[9] Dayson C, Bashir N. The social and economic impact of the Rotherham Social Prescribing Pilot. Sheffield Hallam University; 2014.

[10] Bungay H, Clift S. Arts on Prescription: A review of practice in the UK. Perspectives in Public Health 2010;130(6):277-81.

[11] NICE Evidence Update 13 – Depression (April 2012) Available from: https://www.evidence.nhs.uk/evidence-update-13

[12] NICE guidelines [CG90] Depression in adults: The treatment and management of depression in adults. October 2009. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90/chapter/1-guidance

[13] Özdemir U, Tuncay T. Correlates of loneliness among university students. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2008;2:29. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-2-29.

[14] Riessman C. Narrative analysis. 1st ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993.

[15] Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77-101.

[16] Sanghani R. Generation Lonely: Britain’s young people have never been less connected. The Telegraph [Internet] 2014. Available from: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/11312075/Generation-Lonely-Britains-young-people-have-never-been-less-connected.html

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Psychiatry"

Psychiatry is a branch of medicine dedicated to helping people with mental health conditions through diagnosis, management, treatment, or prevention. Psychiatrists deal with a broad range of conditions including anxiety, phobias, addictions, depression, PTSD and many more.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: