Role of Women in the Irish Construction Industry

Info: 15502 words (62 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Tagged: ConstructionHistoryEquality

The Role Women Play in the Irish Construction Industry.

Abstract

The Irish construction industry is growing faster than any other main sector. This considerable growth of the industry necessitates a raise in the rate of employment of a skilled workforce. Nonetheless, the skill shortage is a key threat that challenges the long-term development of the Irish industry. The Irish construction industry suffers from rigorous skill shortages both at trade and at professional level. Women have made large advances in the world of employment. The employment rate for women keeps rising and at present, there are more women in employment than ever before (now accounting for just under half of the labour force). However, in construction, still one of the largest employers in the Ireland today, advancement has been dreadfully slow. Women account for less than 10 per cent of the construction workforce and only 1 per cent of workers on site. Additionally, the gender pay gap in the construction industry is still wider than in other industries. The construction industry can neither validate nor stand for remaining a ‘no-go area’ for women. To fill the skills gap it will have to draft and retain more women, and not just as supporting roles. The author picks up the challenge facing the construction sector and will show that change can happen. There are no straightforward answers, but the author is sure that women must be essential to the modernisation of the construction industry. The construction industry also suffers recruitment trouble inside its traditional source of labour; young men aged 16-19. The industry cannot rely on only recruiting the traditional male dominated workforce to meet its goals. Women, who are considered competent enough to work in the construction industry, are in principal ignored by construction employers. The regular dependence on a limited recruitment base disadvantages the industry by ignoring half the population and the diversity of skills women have to offer. By restricting the potential workforce, the industry is restricting the choice of potential employees at its disposal, which in turn might lead to the employing of lower quality employees. The Author argues that the employment of women is vital to achieving these objectives and prolonging the development of the industry. The Author argues that there is significant evidence to specify that the male dominated environment of the construction industry represent a considerable obstacle to female recruitment, career progression and retention.

Chapter 1

Introduction

The lack of employing women in construction industry is a matter of alarm to the Irish government and to the industry.

It is acknowledged as a result that there is a need to look at ways to persuade women into traditionally male dominated professions such as those in construction. This problem will be approached by a comparative analysis where the construction industry was compared with other sectors where women are flourishing. Consequently, medical and marketing sectors, which are seen as the available careers for women, have been studied in order to find out what lessons construction can learn from these sectors.

The Irish construction industry is suffering from brutal skill shortages. In addition, it is suffering recruitment problems with its customary male labour force. The continuous dependence on a limited recruitment base disadvantages the industry by disregarding half the population and the assortment of skills these people have to present. Consequently, the under-representation of women in the construction industry is a matter of alarm to the Irish government and to the construction industry itself. The author argues that recruitment of women is essential to achieving these objectives and prolonging the industry’s growth. It is intended at exploring the ways of encouraging women into construction by learning the lessons from other sectors where women are flourishing. The aim is to present recommendations to assist with the employment and retention of women emphasising the role of women in the construction industry development within the Irish viewpoint.

Studies have shown that men and women perform in a different way on jobs. This difference can be accredited to a point to their sex. Studies have also revealed that women are mainly employed in ‘lighter’ building trades and are not expressively present in trades consisting of tasks that are more strenuous. What has not been studied is the association between the unique gender ability and the assignment of women in building firms. With current labour shortages that are only anticipated to get worse, the industry should be vigorously looking to change its aggressive identity and reach out to untapped labour sources.

The objective of this thesis is to decide and analyse the apparent trends of women in construction with respects to recruitment practices and placement inside companies on the foundation of gender. Data and literature on construction industry employment policies, differences in gender, and demonstration of women in the trades has been studied in order to comprehend the observed status of women in the construction industry as a whole.

Aims

The aims are to research the percentage of women who work in the professional field, such as Architecture, Engineering and Construction Management and well as other field in the

industry.

In addition, to conduct a research on the percentage of women who work in the trades industry?

The study collates the main issues surrounding the low percentage of women in the construction industry. It examines the mythology surrounding women in the construction industry and the perceptible unattractiveness of the industry to women.

It will look at the greater picture, grounding the changes within the construction industry over the years to where it stands today in order to develop a deep understanding of the shifting role and need for women in the construction industry. The research increases understanding in the topic of inclusivity and assesses the issues and barriers women face today in the industry.

In addition, it will focus on the reasons behind the under-representation of women in senior management levels in construction. The increasing presence of women in the international labour force continues to inspire research on the leadership styles of women, predominantly to establish if women have their own ways of leading. The genuine concern in leadership differences lies in the equity in selecting the right person with the suitable skills and qualities to make certain the effectiveness and success of the company. The integration of women in leadership roles is not a case of “fitting in” the traditional models, but “giving in” the opportunities for them to exercise their own leadership styles. In view of the fact that men have mainly occupied organisations, a number of women have chosen successful male leaders and their styles as their role models. A number of others chose a different route and commence with leadership styles that frankly expose feminine qualities and behaviours as “silent cries” for social justice and a place of their own in the construction industry. The calculated importance of these styles for organisations lies in the integration of both instinctive feminine characteristics and professional skills developed in the place of work that contributes to the attainability of organisational goals.

Objectives

The objectives are to find out through research to compare the percentage of women

compared to men who work in the construction industry. Also to discover the reasons why

many women choose not to work in the construction sector.

Do many women find it intimidating or believe it is not an industry for women?

The author will discover from the women who do work in the construction industry, the

reasons they have chosen to work in this particular career and also if the find it an enjoyable

career? Do they feel uncomfortable working in an industry which is mainly dominated by the

male population?

Has the construction industry had a higher percentage of women working in construction in

recent years and in which particular fields of construction are they working, both in the

professional and trades industry? Are women being treated fairly and equally in construction?

Is there any way the system can improve to attract women into the construction industry?

How we can overcome bias against women in the construction industry.

It will be investigated to see if all girl secondary schools teach trade subjects such as woodwork, mechanical drawing and other related trade subjects. Do the teachers in these schools encourage girls to take up a college degree in the construction field or to take up a trade such as, painting and decorating or electrician? In addition, if not, why are schools not encouraging young secondary girls to go in the construction direction?

Qualitative Research:

The author researched the D.I.T. library where a number of books, journals and newspapers that refer to women in construction were available.

In addition, research was carried out by using online research. A case study also provided information about the role of Women in Construction.

Questionnaires were circulated to numerous women in the construction industry, to get their feedback on what it is like to be a women working in the construction industry.

Interviews were conducted also with the women who work in the construction industry, both in the professional and trade areas.

It was also discovered in certain cases that many women were not paid the same as men in the construction industry. In addition, decimation still exists in many companies that employ women.

Quantitative Research:

For the quantitative research, the use of bar charts, graphs and tables illustrated the percentage and number of women employed or women who employ both male and female workers in the construction industry.

Using a range of research methodology, certain areas are honed in on such as; what are the percentages of women working in the construction sector? Are women being treated fairly and equally in construction? Is there any way the system can be improved to attract women into the construction industry? How a perceived bias can be overcome to endorsed and increase the percentage women in the construction industry? Why do many women dislike the idea of entering an industry that is mainly male orientated?

Previous Research on Women in the Construction Industry

Previous research on women in construction in the Ireland has concentrated on attracting women to the industry, the experiences of women in the construction education development and their change from higher education into paid work. The poor reflection of construction, a lack of role models and knowledge, bad careers advice, gender-prejudiced recruitment literature, peer pressure and unfortunate educational experiences have all been cited as militating against women’s admission to the construction industry. In recent times, studies have explored the experiences of women within the construction industry. This work has given insight into women’s occupation experiences within the construction professions and the crafts and trades. Research has also examined the resolution of work and family in the construction industry.

Very few studies have looked at views and experiences of key construction industry directors on employing women, and the prospective impact this has on promoting labour force diversity. Therefore, this study makes an exclusive contribution by investigating diversity and equality from the viewpoint of prospective main industry change agents including, employers, professional bodies, clients, training organisations, unions, campaigning groups and industry policy forums. This is required to give a more holistic understanding of why the industry has failed to vary its labour force. The study also significantly evaluated the industry’s prior attempts to diversity its labour force. Together, these researches exposed the necessary challenges for policy makers to conquer in order to promote diversity in the construction industry.

This endorsed the expansion of a practical framework of policy initiatives, which responds to the needs of the construction industry. In this context, the aims and objectives of the study were as follows:

1. To discover industry director’s attitudes towards diversity and equality and recognise their implications for workforce diversification and place of work equality.

2. To create a framework of realistic policy initiatives to deal with inequality and encourage superior diversification of the construction industry labour market.

Chapter 2 – Literature Review

The author will contact Engineers Ireland, the Construction Industry Federation, Women in Engineering, (http://www.cso.ie/en/, n.d.)The Chartered Institute of Building (C.I.O.B.) and The Central Statistics Office (C.S.O.) Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (R.I.C.S) for interviews, questionnaires and statistics.

The literature will discover from these sources, what the percentage is of women employed in their companies. Do the female owners feel obliged to employ female employees or do they choose who the best candidate for the job is, be they male or female?

How was there experience when they started out in the construction industry? Have they encountered any bias or sexism towards them because they work in a predominantly male industry? Are they paid less or the some as their male counterparts?

Studies specifying the situation of women in construction indicate the significance of problems encountered by women arriving and continuing in the construction industry. It is principally these barriers, which lead to a lower contribution rate of women in construction. There are numerous obstacles to women entering and working in the construction industry.

The construction industry has an industry-wide problem with ‘image’, which makes both men and women reluctant or uninterested in the industry

The literature recognises the industry’s image was found to inspire against the entrance of women. The chief image of construction is that of a male-dominated industry necessitating physical strength and a good tolerance for outdoor conditions, harsh weather and foul language. It is chiefly this image that makes women uninterested in the construction industry. Females reflect the equal breaks record of the construction industry is worse than that for males. The C.S.O in Ireland also discovered that 63% of young women interviewed believed that it would be virtually impossible for women to get jobs in the construction industry and only 17% thought that it would be an appropriate occupation for them.

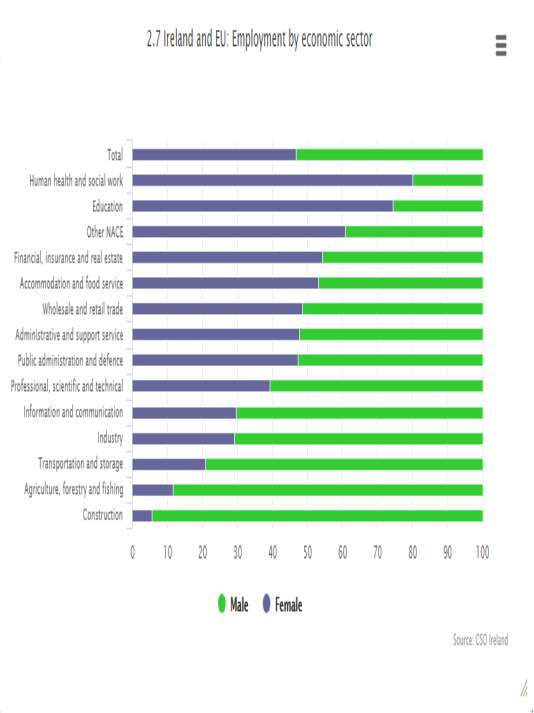

Ireland and EU: Employment by economic sector, 2012 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| % in employment aged 15 & over | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NACE sector | Ireland | EU | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Men | Women | % women | Men | Women | % women | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A | Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 7.9 | 1.2 | 11.7 | 5.8 | 4.1 | 36.9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| B-E | Industry | 16.8 | 7.9 | 29.1 | 23.2 | 11.0 | 28.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| F | Construction | 9.6 | 0.7 | 5.7 | 12.0 | 1.5 | 9.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| G | Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 14.1 | 15.2 | 48.6 | 13.1 | 15.1 | 49.1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H | Transportation and storage | 7.4 | 2.2 | 20.9 | 7.3 | 2.4 | 21.8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I | Accommodation and food service activities | 5.8 | 7.4 | 53.2 | 3.8 | 5.4 | 54.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| J | Information and communication | 5.9 | 2.8 | 29.8 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 31.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| K-L | Financial, insurance and real estate activities | 4.7 | 6.3 | 54.3 | 3.4 | 4.3 | 51.1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M | Professional, scientific and technical activities | 6.4 | 4.7 | 39.3 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 46.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| N | Administrative and support service activities | 3.4 | 3.5 | 47.7 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 48.4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| O | Public administration and defence; compulsory social security | 5.4 | 5.5 | 47.4 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 46.2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| P | Education | 3.8 | 12.7 | 74.6 | 3.9 | 11.7 | 71.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Q | Human health and social work activities | 5.0 | 22.8 | 80.2 | 4.3 | 18.2 | 77.9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R-U | Other NACE activities | 4.0 | 7.1 | 60.9 | 3.5 | 7.7 | 65.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 46.8 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 45.6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Persons in employment (000s)1 | 977 | 859 | 118,390 | 99,120 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (http://www.cso.ie/en/) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(http://www.cso.ie/en/)

| EU 27 percentage breakdown excludes NACE sector not stated, total in employment includes NACE sector not stated. |

- In 2012, the education and health sectors employed 35.5% of women at work in Ireland and 29.9% of women at work in the EU.

- The construction sector had the lowest proportion of women at work in Ireland, with men representing 94.3% of those at work in 2012.

- The sectors with the most gender-balanced workforces in Ireland in 2012 were wholesale and retail trade, administrative, support services, public administration, and defence.

- The percentage of women employed in each economic sector in Ireland is broadly similar to the pattern in the EU, with the exception of agriculture, forestry and fishing where only 11.7% of those at work are women compared with 36.9% in the EU.

(http://www.cso.ie/en/)

“The opportunities on site are open to everybody” – Women in construction Part 1

14th May 2015

Siobhan Tinselly on why she is “looking forward to the day that gender isn’t a discussion piece” in relation to Construction Careers

At present, women account for less than 10 per cent of workers in the re-emerging construction industry. To understand the unique reality of their chosen career path we have put together a series of interviews with three women who have forged successful careers in this lopsided industry. Starting with Irish Mining and Quarrying Society (IMQS) President and TOBIN Consulting Engineers Associate Siobhan Tinselly.

A Natural Sciences graduate at Trinity College Dublin (followed by a Postgraduate Diploma in Environmental Engineering from Trinity and an MSc. in Applied Hydrogeology from Newcastle University), Siobhan became the first female IMQS Vice-President in 2013 before trumping that the following year by becoming its first female President.

“People can become a specialist in a field very quickly”

Her niche expertise in extractive services was central to her rise through the IMQS ranks and is something she sees as a key factor in her success. In her own words, “if you have an interest or develop an interest in a particular area, you can become a specialist in a particular field very quickly if you focus your time and energy on that area”. This approach to forging a career, specifically in construction, is effective regardless of gender and is something Siobhan continues to promote.

Speaking about her election to the position of IMQS President, Siobhan candidly states, “I wasn’t sure how it would be received by the membership”. She explains, “The positive reaction following the announcement was a reflection of a changing industry and a forward thinking membership”. Siobhan also notes the continued support from organisations across the island of Ireland.

“Just the tradition of the industry”

Gender is not at the forefront of people’s thoughts when they ask what she does. In her opinion, people’s “first reaction is intrigue – people are curious to know what projects you are working on and what your role is on those projects…people like to hear about your day-to-day activities and how you got involved”. Gender discussion rarely rears its head as quite simply “it’s a short conversation with nowhere for the discussion to go”.

Siobhan believes that “traditionally construction in Ireland is male dominated, particularly on site, however, this is not the case in the planning/office based environments of the construction industry”. She states that this is “just the tradition of the industry and will be slower to change whereas with the office environment the percentages are visibly different”. For example, TOBIN Consulting Engineers has a very healthy split across both genders with the expertise and experience of the scientist or engineer determining their inclusion in project teams. She is unequivocal however in finishing with the point that “the opportunities on site are open to everybody”.

“The recession was not gender biased”

Many people also point to the recession as a blow to the emergence of women in our industry. Siobhan is adamant that females have been affected “no more than males… the recession was not gender biased”. Siobhan summed up her thoughts on the issue, “I’m looking forward to the day that gender isn’t a discussion piece… that change is gathering momentum”.

When looking for evidence of that trend Siobhan points to the likes of Proof Yvonne Scrannel, Rd. Eibhlin Doyle, Dr. Marie Cowan and Dr. Deirdre Lewis – top female industry experts who “are being recognised for their jobs and for making significant contributions as opposed to the fact that they are female”.

“Work experience is crucial”

Finally, Siobhan reminds any female looking at the construction sector as a career path of the benefits of learning and finding your niche, “the opportunities within the construction industry are vast so, if you have an area of interest, you should do a course to reflect this – but work experience is crucial. Keeping up-to-date with new technologies and guidelines within the industry, reading industry magazines, attending evening seminars, focusing on industry role models on social media and generally being aware of the latest industry trends and announcements – all these activities will help you to keep pace with an ever-changing sector. If you work hard and focus on the field that best suits your interests and capabilities, you will meet the right people and find the best job for you.”

Female contribution continues to rise across many sectors in Irish culture, from politics and business to sport and expertise. Construction appears to be a last stronghold of male-authority in business; nevertheless, there is a strong custom of female leadership in the industry. There are now moves going on to increase female involvement.

The CIF is bringing a certain amount of industry leaders together to deal with the persistently low levels of female contribution to construction. This is a serious business challenge as construction continues to increase powerfully. According to a modern report carried out by DKM (Economic Consultants) with input from SOLAS (known before as- FÁS or ANCO), the industry may possibly expand by 33% to €20 billion by 2020. It is estimated that the construction industry will need 112,000 extra employees across management, craft and trade to supply the houses and infrastructure necessary to support Ireland’s swiftly growing population and economy.

Director of Industrial Relations, CIF Jean Winters said:

“The industry will require around 112,000 extra workers to deliver required construction activity over the next decade. From a practical perspective, the industry is limiting its growth potential if it only recruits from 50% of population. From an efficiency perspective, female participation in business decision making has been proven to improve business performance. We, as an industry, cannot continue to allow such low levels of female participation. Other sectors have taken steps with some success and we need to also. We are using this opportunity, International Women’s Day, to bring together the female leaders of the construction industry to set out a path for industry to increase female participation. At our event, we will also bring together some young women working and studying in construction with a view to building a strong community of female leaders inside the CIF and in the wider industry.” (http://www.cso.ie/en/)

The most recent figures from the Central Statistics Office show that now only 8% of people employed in construction in Ireland are women. Out of 10,000 state-funded apprenticeships taken up last year, only 33 of these new apprentices were female.

CIF Director-General Tom Parlon said:

“I hope the tide is beginning to turn. More young girls must be encouraged to study STEM subjects. This will in turn open up careers in careers in construction for young women, but we cannot wait for this to happen organically. The CIF believes that its members are leading the way in competing for talented female but the industry must look at ways to more rapidly increase participation. The industry is recognising the significant impact that women are making in the area. The CIF is working to bring about a major increase in female participation, both in CIF activities- through our policy and working groups- and in the Construction industry at large.”

“This International Women’s Day the CIF will celebrate the many pioneering women involved in the industry over the years, such as our former President Mirette Corboy and those like her, who have become not only leaders in their field of expertise, but role models for the generations of young women and girls following them” (http://www.cso.ie/en/)

The CIF is hosting Breakfast Briefing: Increasing Female Participation in Construction on Wednesday 8th March to celebrate International Women’s Day.

This event will celebrate the achievements of women in the construction industry and start a conversation in the order to attract more women into Construction Industry, while providing a chance for those entering the industry to associate with female leaders in the construction sector.

“The number of females applying for construction studies courses has not risen radically over the years; that is a fact. However, what is undeniable is that there are now many more female Quantity Surveyors, Project Managers, Architects and Engineers in the industry, particularly at a senior level, than ever before.

The Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland (SCSI) and the Association of Consulting Engineers of Ireland (ACEI) recently said that Ireland is actually lacking in Chartered Surveyors and Engineers, a dearth that could have a huge impact on the construction industry in the next four years.

This summer both bodies were actively encouraging students, particularly females, with an interest and aptitude in STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) subjects to consider a course that would lead them into the construction industry.

At the time, Aine Myler, Director of Operations at SCSI said that surveying, for example, has often been seen as a male-dominated industry, but she says it’s great career for a woman. “Sometimes people feel there is a need for physical strength in surveying but there isn’t. Women tend to be better people persons and the skills they offer are absolutely applicable to this range of opportunities,” she said.

It is clear that for Ireland’s economic recovery to continue, with the Irish Construction and Property Industry at the forefront of that, a more gender-balanced workforce is required.

With that in mind, over the next ten weeks, we will speak to women who have made their way to the top of their specialty in several areas of the construction industry. They will tell us about the challenges they faced, their achievements, the projects they have worked on but will also give advice to and encourage young women who would also like to get into the industry.

Senior Project Manager with KMCS Ltd., Catherine Murphy kicks off the series, filling us in on how she took the ‘scenic route’ to her chosen career and speaks of her time at Carlow IT, where she was the only female graduate from the course.

“Eighty students started, and two of these were girls. In my final year there was one girl who finished-me,” she tells Construction Networks Ireland.

She says she can see a change in the industry now though.

“I would acknowledge the numbers have increased and I am encountering more females in the industry every day, from areas like health and safety to administration on site to architectural, engineering, acoustics and fire,” she says. “Companies need to make a concerted effort from the top to hire females, thus achieving a gender balance within their company. KMCS Ltd. has approximately a 50: 50 males to female gender ratio to the benefit of us within the company and our clients.”

While more women are taking up these jobs and senior jobs into the bargain, figures entering colleges are still low. As of March 2015 there were 2,506 women enrolled in full time undergraduate engineering, manufacturing or construction courses at Higher Education Authority-funded institutions, compared to 14,215 men.

Director General of Engineers Ireland, Caroline Spillane says that, while the outlook is positive in that there was a 9% increase in CAO first preferences for engineering/technology degree programmes in 2015, there is still a lack of gender diversity in these programmes.

“Despite engineers being renowned for their innovation, ingenuity and problem-solving skills, the profession still has to overcome its long-standing challenge of attracting and retaining female engineers,” she said.

Even so, Lorraine Carlisle, CEO of the FKM Group, who we will also speak to us for the series, echoes Murphy’s comments.

“The balance of females to males, since I started, has changed. When I started there was only one other female in the company I worked for and she was in the accounts department. The presence of professional females has increased fourfold since then and they are industry-qualified architects, Engineers and Quantity Surveyors. I do believe the numbers are rising. There is a significant gap but I do see, through networking, an increased number of females but not only females in the industry, females at a senior level as well which is important. It’s in the harder disciplines like QS and Project Management as well.”

Carlisle says that she is of the belief that if you are good at what you do, people look beyond the gender.

“I think the perception of the industry could put some females off but once you’re in it and if you’re good at what you do, then there’s no holding you back. I frequently find myself at round table meetings where I am maybe the only female but my voice has been heard and there is respect and other females I have spoken to would say the same.”

Murphy agrees but acknowledges that her gender can still raise a smile the odd time. “On occasion, I will smile, if I have set up a meeting and you greet a person who maybe you haven’t met before and you see an acknowledgment of, oh, she is actually chairing the meeting. Naturally I would not be a person who would linger on that, we are all in this together be it male or female and we have to get on with it. I would not differentiate between male and female. That being said, I would not be the woman to go to a building site teetering in a pair of high heels and a skirt and not be able to get up a ladder. I’m practical in that regard,” she laughs.” (Murry, 2017).

Woman on Site

“There are 50 cranes on Dublin’s horizon line this week and I counted 11 from the window on the fourth floor of the Construction Industry Federation. So I’m thinking that the figures must be true.

It was a great start to a cold ‘n windy Monday morning meeting up with Dermot Carey at the CIF headquarters in Dublin. We were discussing the lack of women in the industry. The CIF is enthusiastic about the prospect of an increase in the female presence on site. Realising that it’s not every woman’s cup of tea but looking at the fact that more than half the population right now is female, you have to wonder why the number of women is so exceptionally low.

In Ireland today, less than 5 % of construction workers on-site are women and the amount of females in trade’s apprenticeships doesn’t even reach 1%. According to SOLAS women, fill only 34 of the current 10,000 apprenticeship placements.

It’s not uncommon knowledge that women right now are a minority in construction, but we are behind many other places in the world. Statistics from the U.K, U.S.A, Germany and Australia all fall between 5% and 14%.

The news is, that there are a lot of women in Ireland who actually LOVE learning how to use construction tools, though there are psychological hurdles to overcome in every quarter, whether it be a cultivated lack of confidence that women experience, having had it drummed into them for an aeon that is not their domain to enter, and so perhaps they don’t give it a try, or that a lot of people simply don’t expect women to enter that sphere of work so the invite to do so is rare.

There is an age-old myth that construction work requires brute strength rather than physical fitness. The majority of the time this is not true, and these days there are more and more legislative guidelines that recommend manual lifting limits. Working together in groups, or by using devices when moving heavy objects is common sense. There is also the point that newest starters develop strength and brawn over time on the job whether you are male or female. I am a small woman of 5 ft. 5 and have had a fantastic time working in the industry.

U.K. recruitment company Randstad declares it can change its on-site female presence to a much improved 26% by 2020. With the national building industry forecast of a moderate growth of 4-5% between now and then, things are looking promising. This year in Ireland, we have heard from the Construction Industry Federation, of an even stronger growth in the same period. They say that 76,000 new jobs will need to be filled within the next few years. In light of this, we are likely to experience more encouragement and support for women who are have an interest in learning and working in skilled trades…

I’ve been in conversation with some interesting people from all over the country over the last couple of weeks: professional multi-skilled trade’s people, builders, foremen, business owners amongst others, who are supportive of the idea of getting more women on the tools. In addition, a number of who mentioned that they always thought it was weird that there weren’t more women having a crack at it.” (Ireland, 2017)

Women in construction – a summary of facts

Records illustrate that in medieval times, at least four trades employed women workers and they were carpentry, ship righting, plastering and plumbing. Construction is not the only hard work in which women have in the past have done heavy work; women were down the pits with men in the 19th century. Thousands of women were re-trained to fill skilful labour-intensive jobs left unfilled by men in World War 1 and in World War 2. The small percentage of women working in the trade proved that they are competent of handling the work.

Source: The Imperial War Museum

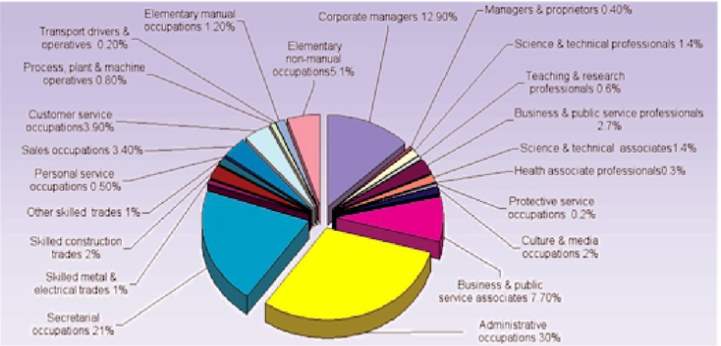

Women in construction by occupation

The chart below shows the occupational allotment of women in the construction industry according to the CSO). 80 per cent of the women work in the skilled managerial, professional, technical and clerical jobs whereas the remainder work in sales, customer service or unskilled administrative occupations. 93 per cent of the women were in non-manual occupations, with no more than about 1 per cent working in the manual trades. Approximately 50 per cent of all women in the construction industry work in administrative and secretarial jobs, whereas 14 per cent are working in professional and associate occupations. 13 per cent are in employment as managers and, of these, a diminutive number are self-employed and managing micro enterprises. Fewer than 5 per cent of all women are working in skilled construction and associated trades, and the somewhat small number of women trainees in the manual trade’s mirrors this proportion.

The chart below shows the occupational allotment of women in the construction industry according to the CSO). 80 per cent of the women work in the skilled managerial, professional, technical and clerical jobs whereas the remainder work in sales, customer service or unskilled administrative occupations. 93 per cent of the women were in non-manual occupations, with no more than about 1 per cent working in the manual trades. Approximately 50 per cent of all women in the construction industry work in administrative and secretarial jobs, whereas 14 per cent are working in professional and associate occupations. 13 per cent are in employment as managers and, of these, a diminutive number are self-employed and managing micro enterprises. Fewer than 5 per cent of all women are working in skilled construction and associated trades, and the somewhat small number of women trainees in the manual trade’s mirrors this proportion.

(http://www.cso.ie/en/, n.d.)

Gender divisions and subordination

“Women do two-thirds of the world’s work, receive 10 per cent of the world’s income and own 1 per cent of the world’s resources. This information regarding the importance of women’s work, paid or unpaid, was encapsulated during the UN decade for women (Charles,(Handy, 1993).”

“The Second World War proved beneficial for women in terms of breaking down job barriers and creating new openings. The 1960s saw women taking control over their fertility, the 1970s brought about the equal opportunities and equal pay act and in the 1980s; the principle of non-discrimination between men and women – equal pay for equal work – was recognised. Post-war developments created new and beneficial social and economical situations for women, shifting towards the services sector industries ((Hakim, 1996)).”

At present, women make up above fifty per cent of the labour marketplace. This increased representation may perhaps be accredited to the following reasons:

- Deskilling of traditional male jobs.

- Demographics: better life expectation and having less children.

- Streamlining of emotional expectations in the direction of self-expectancy.

- Economic requirements: increased cost of living and therefore the need for second

Wages.

- Increasing levels of educational accomplishment.

Even though women have been attaining economic equality with men, women carry on remaining disadvantaged and discontented on the work front. Men and women are divided into different occupations with women concentrated in what may well be described as a ‘job ghetto’ of low paid work and the disparity in pay continues to be present though by narrower borders. Men keep on having the upper hand whereas women keep on to work twice as hard to prove themselves in ‘male-dominated’ industries. This segregation of women into customary female work-related sectors and hierarchical positions by women occupying simply junior and supporting positions results in their evident under accomplishment in the labour market relative to men.

Gender-based ideas of the construction industry persevere among men in general. Some apparent apprehensions of men in the direction of women entering the work place include not being equally appropriate for the work or having the innate talent to use tools, comprehend buildings, lift heavy materials, possess expected strength and handle nonstop criticism or ‘straight talking’. They feared difficulty in the form of distraction at the job, sexual harassment proceedings, and the possibility of women to overreact. On the other hand, they consider that certain jobs were predominantly suitable for women like finishing jobs, plastering, tiling, joinery etc. This was based on women’s talent for attention to detail, and good logic of design and colour and consistency. They are tidier and more vigilant, they tend to be more organised and work well together.

Men who have had experience of working with women find they are competent, they fit in well with male contemporaries and they add to a quality results. Young women are becoming more confident about entering construction industry jobs and being accepted for their donation on an equal, but dissimilar, footing with their male contemporaries. Culture change is considered a key matter vital to attracting and keeping women within the construction industry.

Men’s observation of women coming into the industry is equivocal with some men being protective and unwilling to accept women’s abilities and talents, but others through experience are confident of women’s abilities and have a defensive and welcoming approach.

Conventional employment practices such as ‘word of mouth’ recruitment and unfair burdensome terms and conditions like mobility, lack of part-time work, advertisements and brochures showing images which reveal masculine values and interests, unstructured interviews, prejudiced selection criteria, and sexist attitudes, account for imperfect input of women in the construction industry. The composition of the existing labour force is a consequence of the traditional employment practices. As a result, recruitment and its gender inequalities are the liability of management and the constant re-creation of an all-male labour force is questionable. It is then a very fascinating question to ask whether the attitudes of the existing labour force produce a real limit to what could be implemented by a management that looks to generate diversity. Support and guidance to minors, parents and teachers, use of web portals, and job fairs are valuable communicators in this case.

Work-family disagreement is defined as an appearance of inter-role disagreement whereby job and family demands cannot be met concurrently and is an on-going dilemma for women with career aspirations. The conflict between work and family obligations, that many construction professionals experience, is more sensitive for women than for men. Latest studies suggest that job demands borne by construction professionals are harmful to their personal relationship Onsite based workforce, both professional and manual workers, are regularly subject to changing work locations. This can entail travelling significant distances and/or long periods away from home, circumstances, which can present severe difficulties in terms of transport and child- care. The construction industry fails to understand some of the problems related with combining work and family commitments, and companies have a propensity to treat family and work as entirely separate.

A study undertaken by Lingard and Lin (2004), suggested that women in construction adopt an ‘either or’ approach to career and family. However, women who expect to balance both family and career success in the construction industry may experience significant difficulties (Lin, 2012)

Construction’s image

The Construction industry has one of the most unpleasant public images of all industries. It is seen as promoting adversarial business relationships, poor working practices, environmental coldness and having a name for under-performance. There is moreover, a broadly held observation that career opportunities inside the industry are limited .This is compounded by the poor quality of information given by careers advisors concerning the opportunities offered within the industry, and the qualifications necessary .This image dilemma has been shown to be a significant influence on women’s underrepresentation established that several women seethe construction industry as a male dominated, intimidating environment, with an deep-seated masculine culture characterised by arguments and crisis, point out the satire that in a highly gendered culture, construction work is understood as heavy ‘man’s work’ in contrast to lifting and carrying sick people, small children and all the domestic household tasks of the home which are normally understood as ‘women’s work’. These assumptions support the common argument that women are not physically strong enough to take on construction work. Research have shown that women consider it virtually impossible to get jobs in the industry, jobs are out of place for women, sexual harassment is as chief concern and that all the top jobs in the construction industry go to men. Women also observe the industry to have insufficient amenities and meagre training and established that men had a poor image of the industry describing it as grimy and dangerous; consisting of low standing manual work, low wages and lengthy hours.

Sexism, harassment and bullying

Research has revealed that women’s experiences of the construction industry consist of sexual discrimination, harassment, bullying, intimidation and less obvious discriminatory mechanisms such as prohibited from out of work social occasions (accredited to have a lot of career enhancing benefits) present a colourful account of the cultural surroundings faced by professional women in site-based projects where sexual harassment is prevalent and seen as an occupational danger, which has to be tolerated. Tradeswomen in addition find they have to prove their capability to every new group or individual male employee they come across regardless of their qualifications and experience. Women in the construction industry have reported being singled out by their male co-workers for tasks planned to ‘test’ their capacity. These comprise of being sent up high buildings, expected to inspect hazardous buildings, subjected to offensive and indecent behaviour and being asked technical questions intended to catch them out. A number of women who have refused to take part have found themselves accused of ineptitude and have been targeted for further aggravation. Survival takes its toll and a persistent lack of acknowledgment of women’s skills add to stress. Additionally, the cost of poor performance for women reinforces gender stereotypes of women’s lack of talent. Additionally, women may not receive sufficient support because those in senior positions are men.

Why students filling in their CAO application forms should consider construction courses

| Growth in the construction industry shows no sign of abating. By 2020, Ireland will need an extra 112,000 new workers in the sector, to produce an expected output of €20bn. The government commitment to create 60,000 new jobs makes the construction industry extremely attractive for graduates with the pick of employers competing for their attention. Ferdia White of Hays Construction & Property, gives an overview of the construction landscape that Irish students can expect to navigate in the coming years. |

As students across the country consider their CAO options or indeed change their mind, it is important to highlight the opportunities that exist within the construction and property sector today and how they will multiply over the coming years. Once students have graduated, where will they be working and what will they be doing?

Graduates from construction courses can expect to receive salaries between €25,000 and €35,000 and with demand for graduates increasing, so too will salaries. Many graduates are now in a position to negotiate better salaries with often more than one offer to consider.

A construction related degree will provide a passport to travel, something that is unique among college courses. Our degrees are recognised worldwide with Irish architects and engineers regarded as some of the best in the world.

Quantity Surveying

Quantity surveyors typically work for either the client or the main contractor and are responsible for controlling cost on projects. Graduate quantity surveyors will begin their careers working with a senior surveyor for the first 2-3 years before taking ownership of a project. As a senior surveyor, they may control one project or several, depending on the value of the projects. It is not just projects that will require management, newly appointed senior surveyors will often manage junior surveyors.

Construction Management

Graduates from construction management courses are hired by main contractors to fulfil a wide variety of roles including estimators, site engineers, assistant project managers and assistant site managers. The majority of these roles will eventually develop into project management roles. Graduates who choose to become estimators will take tender drawings and price the entire project, processing take offs and sourcing quotes for materials and sub contracts.

Architecture

The role of an architect is both creative and technical, firstly sketching a client’s idea before making it a reality. Graduates will see opportunities with both architectural practices and public sector clients. Typically, they will spend 2-3 years working on a project, which will then be signed off by a registered architect. This project, combined with the successful completion of a professional practice exam, will see them become a part III architect. This qualification opens up possibilities across a wide range of projects.

A degree in architectural technology will provide opportunities in many of the same areas as one in architecture. Graduates here work as part of the design team, with an emphasis on providing technical assistance. Day to day duties include producing detailed drawings on AutoCAD/Revit and producing tender packages.

Engineering (Common Entry)

Career path

Students who choose engineering courses will have varied options depending on the area they choose to specialise in. Graduates from civil engineering and structural engineering are most likely to find employment in the construction industry. Civil graduates will work for either consultancies or contractors. A role in consultancy will involve the design of infrastructural projects such as roads, bridges, and drainage and water networks. While with a contractor, a graduate will manage engineering on site and will often move into a management position. Structural engineering graduates will work in consultancies ensuring buildings are designed safely.

Building Services

Building services graduates will experience high demand for their skills from mechanical and electrical consultancies, contractors and main contractors. Consultancy roles involve the design of mechanical and electrical services for buildings, working with the client to convert their brief to engineering drawings. Contractors hire graduates to manage the installation of services on site, before progressing to a project management role. Main contractors require building services graduates to coordinate the on-site contractors and liaise with the design team. It is not uncommon for mechanical engineering and electrical engineering graduates to forge careers in building services. http://cif.ie (White, 2017)

Skills shortages

The matter of skills shortages in the construction industry has been well documented. Construction has the sharpest skill shortage of any sector in Ireland. It is reported that as many as 61% of construction companies are suffering problems in recruitment. The construction industry is at present experiencing a fast recovery, and workloads are expected to grow. The causes of the skills shortages in the Ireland construction industry are primarily attributed to the demographic decline in the number of young men available to enter the labour market (a smaller amount of younger people to employ as a result of an ageing population, and bigger numbers of young people staying on in education), which has amplified competition for new entrants to the labour market. The state of affairs has been exacerbated by a dependence on temporary agency labour and self-employment. This means that construction companies have to seek alternative sources of labour, meaning attracting more women. Nevertheless, the propensity for women to reach an unexpected career halt, which is accredited to employers recruiting women to fulfil short-term need or labour shortage instead of a long-term investment. As a result, it is thought that demographic opinion would do little for labour force diversification in the long run.

Conclusion

This has presented a review of the employment problems associated to the underrepresentation of women in the construction industry. It has highlighted women’s experiences of person and institutional discriminatory practices and sexism; nonflexible working structures; an uncooperative atmosphere for the understanding of work and family and an adversarial place of work society.

A hole in the facts exists, as prior research has not explored the views of a variety of the construction industry directors who are key agents of change, exerting influence at levels inside the construction industry. These comprise of individual employers, professional body representatives, unions and campaigning groups. These directors are frequently in charge of strategy formulation and operations. Therefore, without exploring their views and responding to the challenges that these may stand for, it is to be expected that efforts to encourage the labour force diversity will only be in part successful.

The topic of the labour force diversification has been ultimately given recognition by numerous industry reports and initiatives. Nevertheless, this literature review has exposed that women entering and working in the industry are faced with a difficult range of structural and attitudinal barriers. Consequently, there is a call to investigate how the construction industry efforts to diversify the construction labour force have confronted these problems. It is also significant to discover how heads of companies responsible for making change inside their establishment, have engaged with the diversity programme. In addition, this review has revealed how construction industry processes, attitudes and behaviours have served to prohibit and marginalise women at all levels inside the construction industry. Therefore, an incorporated set of policy initiatives, which tackle these problems, is likely to progress opportunities for underrepresented groups in the construction industry.

Chapter 3

Methodology and Research

Introduction

In this chapter the author will be discussing the procedures used to find the conclusion and produce any informed recommendation for this dissertation. The author will go into detail about the methods and questionnaires will be inspected and the steps that were taken to carry these procedures. Google drive was used to create the questionnaire.

Execution of the Research

To achieve the aims and objectives, a questionnaire was sent out too many women who work in the construction industry, both in the professional industry such as architects, engineers, site managers, Quantity Surveyors and Construction Managers and the trade industry such as painters and carpenters.

Also the author has both qualitative and quantitative research methods. The questionnaire developed is considered to be a quantitative piece of research as it is collected detailed information about the role of women in the construction industry.

Questionnaire Survey

Using questionnaires was an ideal way of obtaining information about women’s views on the construction industry. They information was fast and easy to distribute amongst the women who received the questionnaire. The aim of the questionnaire was to obtain information from women in the construction industry and what they knew about the industry and how they felt working in the industry.

The questionnaire contained twelve questions that requires answers. This was the best way to help carry out the aims and objectives for this dissertation. The questionnaire was sent to 12 different women all of whom have experience in the construction industry.

The questionnaire goes into great detail about women’s experiences in the construction industry. From starting out in the industry and working their up through the company ranks. And women who work in the trades sector also.

The author structures the survey so as to get an overall view of women’s knowledge about the construction industry. The questionnaire was set up using google drive and emailing it to the chosen participants for them to fill it in and send it back. The people chosen were a mixture of architects, engineers, lecturers, college students and trades people. Many of the participants were know but, also random people were also selected.

Interviews

Interviews were conducted with women who have experience in the construction industry and also a college student in DIT. A representatives of a construction company was interviewed about their current working operations and their past experiences when first entering the construction industry. Questions were asked to assess their responses towards applying such a system into their current operations. A student was interviewed about her interest in construction and what she expects for the future in the industry. A painter and decorator was also interview on her first hand experiences working on a build site that were predominantly male trades people. The objective being: to get knowledge from their first-hand experience about the construction industry. To examine and understand the meanings that women have for their everyday activities, qualitative interviews shaped the chief method of data collection. The purpose of interviewing is to produce information from the respondent.

The interviews were conducted in a relaxed, free-flowing manner using open-ended questions to permit the collection qualitative information. The interviews were not limited, and the interviewees were permitted to talk until the interview reached its normal conclusion, or was finished because of time limitations dictated by the interviewee’s work situation. The average interview time was around one hours, even though it was not rare for the interview to go on for significantly longer. The interviews were carried out in the interviewee’s natural work environment, and were conducted in private offices or meeting rooms.

Questions about issues related to their experiences starting out and their present stage in the construction industry today and the difference between men and women in the industry. This has been determined to be essential to this research are as follows:

Q 1. What made you decide to take up a career in the construction industry?

Q 2. Did you have any fears of entering a male-dominated industry?

Q 3. Did it frustrate you that men were predominantly in the managerial positions?

Q 4. Do you think that the construction industry is changing?

Q 5. How can more women be enticed into the industry?

Q 6. Do you think secondary schools should promote and encourage young women into the industry?

Q 7. Should trade subjects, for instance, woodwork and metalwork be part of the curriculum in all girl’s schools?

Q 8. What was your first job in construction?

Q 9. What is your current job?

Q 10. When did you realise you wanted to work in the construction industry?

Q 11. Is there someone in particular in your life that led you to this career?

Q 12. What advice would you give someone starting out?

Q 13. What is the biggest challenge of being a woman working in construction?

Conclusion

The author has outlined two methods on how the conclusion was reached. These two methods were a questionnaire survey and interviewing three women in the construction industry.

The questionnaire survey gives a good insight to what women think of the construction industry in their past and now in the present. It gives a great insight into the surrounding and environment women experience working in the construction industry.

Chapter 4 – Data Analysis

Findings from the Questionnaires

Introduction

The author created a questionnaire and emailed it to women in various fields in the construction industry. These women include lecturers in a variety of colleges and universities, women in the construction industry, trades women and college students.

The aim of the questionnaire survey was to get a feedback on what women think about the construction industry, if they are satisfied with the present state of the industry and if there should be changes to the construction industry.

Also three interviews were carried out. The three different women were all involved in the construction industry in different ways. Interview 1 is with a third year college student studying Construction Management in DIT. Interview 2 was with a woman who started out as a secretary with a construction company who later on became co-owner of the company.

And finally interview 3 was with a woman who works as a qualified painter and raised three children while doing her trade.

Analysis of the Questionnaire

Question 1. What made you decide to take up a career in the construction industry?

Answers:

- A love of Architecture.

- I always wanted to make/build things. I was fascinated by bridges.

- I had an interest in Architecture and when I was faced with a choice of building, business or computer studies diploma, I chose building.

- Good at maths and physics in school so engineering seemed obvious choice.

- My Father is an Architect.

- I always had an interest in engineering.

- My Grandfather ran his own construction company. I started out as a painter and decorator.

- Had an interest in it in school.

- An opportunity arose in an engineering consultancy on my return from living in Australia.

- Through family.

- Family Member.

Question 2. Did you have any fears of entering a male-dominated industry?

Answer:

- Yes. I went to an all-girls school and I have two sisters so embarking on a. Male dominated course was terrifying.

- No – if anything I thought it would be cool to be different.

- No.

- I had the preconception that they would be better at maths than me as that’s what we typically hear, but it wasn’t true. Otherwise I didn’t have any fears.

- No. I gained a lot of confidence from my Father.

- Most certainly. I started college in 1969. It was very male dominated.

- Not Really. I worked with my uncle and many other men and they made me feel comfortable.

- Yes. In college the vast majority in the construction courses were male, not too many women.

- No – this wasn’t an issue for me.

- Yes, because I knew I would be one of the few women in the college and the only woman in my course.

- No, this had never crossed my mind

Question 3. Did it frustrate you that men were predominantly in the managerial positions?

Answer:

- I never really thought about it in my early career but yes I am more frustrated now but that is partly because there are insufficient numbers of women at that level.

- Frustrate – no, but when I was promoted a ‘similar’ man had to be promoted too – ‘to keep the peace!

- At times.

- Yes, when I started working as an engineer it was very different from college, very few women over the age of 35, mainly women in roles of hr or admin. I figured it was due to historically few women choosing engineering and that there would be more women in managerial positions in a few years’ time.

- Yes. I wasn’t too pleased to see so few women working in the industry.

- At the time I started it was frustrating but, it was accepted in those days the men got all the top positions.

- I am now a Project Manager. I would love to see more women in my profession.

- No.

- No because at the time several women were rising through the ranks.

- No because there is a lack of women in the industry.

- No. Whether male or female, the person best qualified and experienced should be allotted positions.

Merely filling quotas means that the best person may not in fact get the position.

Question 4. Do you think that the construction industry is changing?

Answer:

- In terms of gender, too slowly. I recently spoke with a recent female QS Grad who said there were 4 out of 60 females in her year. When I Graduated, there were 6 females so rather than having progressed it appears to have gone in the opposite direction.

- Yes.

- I think all industries are changing, however due to the percentage of men in the construction industry, it will take time before more women are in senior roles within the industry.

- Yes, the older men still would have told sexist or racist jokes, would swear and shout in meetings, but the younger guys are simply more used to a mixed environment.

- Yes. Since I started in the construction industry 10 years ago, I see more women getting involved in the industry.

- Most definitely. Today there are many more women in engineering than in the 1970’s when I first made it in construction.

- Yes. It is changing. More women are working in the industry but, not as many as I would like to see.

- Yes. It is changing. More women are working in the industry but, not as many as I would like to see.

- Yes. More women are now in the construction industry.

- Slowly. It is still deemed to be a combative career.

- Yes.

- Over the years, yes.

Question 5. How can more women be enticed into the industry?

Answer:

- Encourage girls at a young age to consider it as a career and that means educating careers teachers as well. Show girls that Construction doesn’t have to be intimidating. There are so many opportunities.

- Role models at primary school – but this must be funded from government. Women engineers are too busy doing a great job and usually child caring too that it is difficult to find the time in addition to the day job. Whilst employers are ‘supportive’ of women attending schools they are not going to put up with a women leaving the office for a day a week to do it! So we can at most visit 2 schools a year and that’s not enough.

- Through awareness and women role models.

- Flexible working hours will encourage more women to any industry as child care usually falls to the woman to organise unfortunately. Having more women will entice more women, training women for management roles and creating an environment women feel comfortable in i.e. less aggression, perhaps training in keeping calm and not using aggressive language.

- Teach more construction based subjects in girls’ schools.

- Today with the amount of women in the industry, they should be taught this in school and encouraged to talk up a career in our industry.

- More effort promoting our industries and enticing women in. Make it look attractive to women, which is it! I love my job.

- Promote it in schools.

- Raise awareness of the diversity and opportunities afforded by a career in this sector.

- By colleges getting in touch with all girl secondary schools.

- Awareness, through second level education.

Question 6. Do you think secondary schools should promote and encourage young women into the industry?

Answer:

- Absolutely.

- Yes – but guidance counsellors need to be better informed.

- Yes.

- Yes.

- Teach more construction based subjects in girls’ schools.

- I have gone to many girl’s schools to promote engineering and other construction industries. To reassure the girls that women have a place in the industry and women are successful in the construction industry.

- Yes.

- Yes.

- Absolutely. Women make excellent project managers and are good at stakeholder engagement. More women in the sector could lead to less projects ending up in litigation.

- Yes

- Yes, but in a balanced way.

- All areas of work should be equally represented.

Question 7. Should trade subjects, for instance, woodwork and metalwork be part of the curriculum in all girl’s schools?

Answer:

- Yes. I didn’t have that opportunity but I would have loved to have taken such subjects.

- I would have loved to do this – but not if I had to give-up a more ‘academic’ subject. I also don’t think these subject would have helped me in my career. I would have liked to do them because I like making things.

- Yes.

- Yes, also applied maths is usually not available in girls’ schools.

- Without a doubt.

- Absolutely.

- Yes.

- Yes. This will encourage more girls to think about a construction degree for their futures.

- Yes, I think they should be offered in all schools – and be compulsory up to Junior Cert. I think there should be a subject called Engineering also on the curriculum.

- Yes.

- Yes.

Question 8. What was your first job in construction?

Answer:

- Trainee QS.

- Student civil engineer.

- Working as an intern in an architectural practice (age 14).

- Structural design engineer.

- Work placement in an Architectural company.

- When I graduated, I got a job with a small engineering company. I was thrown in at the deep end and I not only loved but I relished it!

- Painter.

- Engineer.

- QA Manager in an engineering consultancy.

- Intern in a consultancy firm.

- M&E Consultancy.

Question 9. What is your current job?

Answer:

- Head of Business Development

- Engineering Academic but I was a regional director of a consulting engineering firm when I worked in industry.

- Head of Department of Architecture, Third Level education.

- Lecturer.

- Architect.

- Senior Engineer in a company.

- Project Manager.

- Engineer.

- CPD & STEPS Director.

- Full time student but will be in a graduate program in transportation and highways.

- Education (Technical Officer).

Q 10. When did you realise you wanted to work in the construction industry?

Answer:

- A few weeks after starting a diploma course in building technology.

- 14-15.

- I knew I wanted to be an architect when I was 7.

- When I was about 12, and I was on a construction site.

- When I was in my Father’s office as a child. I loved the idea of being an architect.

- All my life.

- When I was 15.

- When I joined the engineering consultancy and really enjoyed working with engineers and seeing major projects going from concept to completion.

- In transition year in secondary school.

- After investigation into engineering & first year in college.

- I came from an all-girls school where no trade subjects were available at the time.

Q 11. Is there someone in particular in your life that led you to this career?

Answer:

- Not really although my dad was an electrician and as one of three girls I never really saw gender as a barrier.

- My dad was a builder and I grew up in the countryside so I was always around ‘construction’. I wasn’t encouraged to go into construction by my parents, but neither was I discouraged. They were just very proud I was going to college.

- No.

- Probably my parents who said engineer when I was good at maths and science rather than saying a more typically female job.

- My Father.

- Myself.

- My Grandfather.

- My Physics teacher.

- No.

- My step-father

- Yes, a family member.

Q 13. What advice would you give someone starting out?

Answer:

- Be brave. Persevere. Believe in yourself and if you cross paths with other women ask them for advice because they are probably willing to help you.

- Stick at it – being a female is an advantage- it lets you stand out and be noticed and people (clients) remember you.

- Work across the industry, in architecture, engineering, and construction both on site and in offices. This broader understanding of the industry will help to give information about which areas you prefer and are good at.

- It’s not easy, but if you can stick it out until you are in a managerial position then you’ll shine.

- Be positive. Don’t feel intimidated by what people see as a male orientated industry.

- If you want to work in the industry, go for it! Don’t think just because it’s seems to be male orientated, that are many successful women in the profession also.

- Don’t feel intimidated because it seems to be a male industry.

- If you have a goal in becoming and Engineer or Architect, follow these goals and you will make it.

- Try to work for a small consultant first for better variety of experience and increased responsibility from an early stage. Always do your very best to deliver on your promises and your reputation will grow quickly.

- Don’t give up when it gets tough.

- Research all options well, for both course choice and employment prospects afterwards.

Q 14. What is the biggest challenge of being a woman working in construction?

Answer:

- Working within a male dominated industry and perceptions that women can’t succeed in this industry.

- Equal pay.

- Bullying and lack of professional respect by male colleagues.

- My work environment was very much an old boys club, most are used to not having women around, often on site the men use the women’s toilet because there are no women, it can be quite uncomfortable, you can go to conferences and be the only woman in the room.

- First year in college, being the only women in a class of 25 men.

- Sometimes companies don’t give women equal pay.

- I don’t have many problems. But, I do know many women are not getting paid the same as men in many companies out there.

- Making my voice heard. many men didn’t like taking orders from a woman.

- The public not having an appreciation of the opportunities in this career.

- Having men not taking you seriously or to have them look down on you.

- None, in my opinion you enter your career choice for the type of work you are qualified to do, whether male or female.

Findings from the Interviews

Introduction

The interviews offer the opinions, personal insights into the role of women in the Irish construction industry. The women interviewed are;

Lilly Mae Hand – Third year student studying Construction Management in DIT.

Linda Quearney – Co- Owner of Goulding General Contractors.

Holly Byrne – Painter and Decorator.

The interviews mostly took the form of an in-depth, qualitative data collection

method intended to inform the author on the subject the role of women in the Irish construction industry. The interview questions sought to gain information on how women are perceived in the construction industry and what they think of the industry now and when they started out in construction.

The full transcripts of the interviews can be found below.

Interview Number 1.

Interviewee: Lilly Mae Hand.

Student Studying Construction Management in DIT.

Date of Interview: Thursday 6th April 2017

Time of Interview 15.00 PM.

Question 1. What made you decide to take up a career in the construction industry?

“My father is a structural engineer and my grandfather was a tradesman so I have always been exposed to construction in some way. All my aunts and cousins are nurses or are involved in the medical field, so it seemed like the two vocations in my family were construction and nursing and I couldn’t imagine anything I’d hate more than being a nurse so I thought I’d try construction and I love it. I never wanted a job where I’d be stuck in an office all day every day so Construction Management was the perfect fit.”

Question 2. Did you have any fears of entering a male-dominated industry?

“Not really. There are only two of us women in the class of over thirty men. You have to be as hard as nails. Be practical. I had knowledge of the industry before I started in college, I worked with my father on occasions.

Question 3. Do you think that the construction industry is changing?

“Yes. More women are going into the construction industry. The problem of being a woman in this industry is that women tend to become pregnant between the ages of 28 -32, so many employers tend to put men in the managerial positions. But today the construction industry is less of a manly job. Women in my opinion are good with detail, for example they can see a fault with a plaster cornice if it is not matching properly”

Question 5. How can more women be enticed into the industry?

“I went to an all-girls school and by doing honours maths you get 25 extra points in your leaving certificate. More girls need to do honours maths and physics.”

Question 6. Do you think secondary schools should promote and encourage young women into the industry?

“Yes. Most girls’ schools do teach practical subjects, like woodwork or mechanical drawing. So as I said before girls need to push for Maths and Physics. We had a lecturer from DIT who lectured in the construction industry come to our school, she was dressed up with makeup, a dress and high heels to demonstrate that construction is not a dirty trade and many women work in the industry. We found that really cool.”

Question 7. When did you realise you wanted to work in the construction industry?

“Before my leaving cert. When I was in 5th year I studied honours Maths and Physics, so I knew I was going to go to college and take a degree in the construction industry.

Question 8. Is there someone in particular in your life that led you to this career?

“Yes. My dad he is a structural engineer.”

Question 9. What advice would you give someone starting out?