Effectiveness of WIC Nutrition Education

Info: 8814 words (35 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Tagged: NutritionCommunity Health

Public Health Issue

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) is recognized as one of the most successful federal assistance programs in the nation. Studies have indicated the numerous health benefits that recipients experience with participation in WIC. Though there is no doubt as to the impact WIC makes, the question as to which component of WIC, the supplemental food package, nutrition education or health referrals, has the greatest effect on various health outcomes. Few, if any, studies have examined which factor effects long-term health. The nutrition education component likely has a lasting impact and aids participants in making dietary and physical activity behavior changes. However, it is difficult to determine if participants are grasping the information provided to them at the nutrition education sessions and using the acquired information to make appropriate behavior changes. There is limited and outdated research examining the effectiveness of WIC nutrition education, and even fewer studies have assessed the various instructional methods. Additionally, it has been cited across the nation that WIC clients are not participating or completing the required education. However, as previously mentioned, there is very limited research on why participation is so low and how to make improvements. Increasing accessibility of WIC nutrition education and making sessions interesting and engaging is the first step in developing effective nutrition education. Research is necessary to determine if new and innovative styles of education will improve participation rates, increase nutrition knowledge and improve health outcomes in WIC participants.

Background of Organization

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) was created in 1972 as a two-year pilot program as an amendment to the Child Nutrition Act of 1966. It was established as a permanent program in 1975, and is now the third largest food and nutrition assistance program, serving approximately eight million participants per month in fiscal year 2015, including over half of all infants born in the United States (Food and Nutrition Services [FNS], 2018a; National WIC Association [NWA], n.d.; USDA Economic Research Services [ERS], 2017b). WIC operates at the Federal level under the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Food and Nutrition Service (FNS). It is administered at the local level by 90 WIC State agencies covering all 50 states, the District of Columbia, 34 Indian Tribal Organizations and five U.S. territories (USDA ERS, 2017a). WIC provides Federal grants to States for supplemental foods that are good sources of nutrients typically lacking in the diet of low-income populations such as protein, iron, calcium, vitamin A and vitamin C. Health care referrals, breastfeeding support and nutrition education and counseling are also provided (FNS, 2018b; USDA, 2001). WIC is not an entitlement program, but rather a Federal grant program; Congress does not set aside funds to allow every individual to participate in the program, rather, Congress authorizes a specific amount of funding each year for program operations (USDA ERS, 2017a). Federal program costs were roughly $6.2 billion in fiscal year 2015 (USDA ERS, 2017b).

WIC’s mission is “to safeguard the health of low-income women, infants, and children up to age five who are at nutritional risk by providing nutritious foods to supplement diets, information on healthy eating, and referrals to health care” (FNS, 2018a). WIC aims to influence lifetime nutrition and health behaviors in a high-risk population, and promotes breastfeeding through various programs. WIC services are provided at county health departments, hospitals, mobile clinics, community centers, schools, migrant health centers and camps, public housing sites and Indian Health Service facilities (FNS, 2015). To qualify for WIC, an applicant must be either a pregnant or postpartum (up to one year if breastfeeding or six months of not breastfeeding) woman, an infant younger than one, or a child up to his or her fifth birthday. Additionally, applicants must have a family income at or below 185 percent of the U.S. poverty level or participate in other benefits programs such as the Supplement Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Applicants must also meet state residency requirements and be at nutritional risk as determined by a health professional (USDA ERS, 2017a).

WIC has undergone various changes since the erection of the program. In 1978, changes to legislation occurred that required nutrition education be provided to participants in order to receive vouchers for WIC approved foods (NWA, n.d.). Nutrition education topics include healthy eating, appropriate infant feeding, breastfeeding support and other topics, which help participants understand theirs and their children’s specific nutritional needs and learn about health prevention and improvement strategies. A Registered Dietitian, degreed nutritionist, or other certified professional authority typically performs the nutrition education (WIC, 2018).

Literature Review

WIC is considered one of the most effective federal assistance programs established in the United States, having both impacts on maternal, infant and child health as well as healthcare savings. One of the most influential studies conducted in the early 1990s by Devaney et al. found that each dollar spent providing WIC prenatal benefits yielded a $1.77 to $3.13 savings for newborns and mothers in Medicaid costs over the first 60 days after birth. The study also found that prenatal WIC participation was associated with increased birth weight, fewer preterm births and longer gestational age (Oliveira, Racine, Olmsted, & Ghelfi, 2002). Another study conducted by the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) combined results from 17 studies and determined that each Federal dollar spent on WIC prenatal services in 1990 saved an estimated $3.50 over an 18-year period in Federal, State, local and private health care costs (Oliveira et al., 2002). Though these studies were conducted nearly 30 years ago, their results still stand to be significant. Other studies have reported various health benefits of the program such as a reduction in premature births, improved birth weights, reduced fetal and infant deaths, reduced incidence of iron-deficiency anemia, increased access to prenatal care earlier in pregnancy, improved diet quality, increased access to regular screenings and other health care services and other various health impacts (NWA, n.d.). However, it is important to note that the impact of the WIC program on health outcomes has been questioned, due to issues related to selection bias. Selection bias may occur in these research studies because WIC evaluation studies are not randomized for ethical reasons (Oliveira et al., 2002). It is also important to note that, though numerous studies have determined participation in WIC has positive impacts on various health outcomes, it is difficult to determine which component has influenced these results. Various components may contribute to the health benefits noted, such as increased food supply, increased screening, increased referrals and ease of access to other health care professionals, breastfeeding support and nutrition education.

Nutrition education is a critical component to the WIC program, which is intended to influence participant nutrition and health-related knowledge, attitude and behaviors and may lead to long-term health improvements of participants (USDA, 2001). WIC nutrition education is designed to improve the health status and achieve positive changes in dietary and physical activity habits of recipients, and is a mandatory component of WIC. However, it is difficult to ascertain whether or not nutrition education makes a significant impact on participants, and few studies have been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of WIC’s nutrition education program. Most studies were conducted more than 15 years ago, and found discouraging results. For instance, in The WIC Program: Background, Trends, and Economic Issues 2009 Edition (2009), various studies were summarized to explore the effectiveness of WIC’s nutrition education program (Oliveira, 2009). A study conducted by the GAO in 2001 reviewed previous research on the effectiveness of WIC’s nutrition education and determined the research to be severely limited by methodological constraints, including the use of outdated and poor-quality data, and concluded the research provided few, if any, insights into the effectiveness of specific WIC components (Oliveira, 2009). Another study aimed to determine the effectiveness of different approaches to nutrition education (a computerized touch-screen video for individual nutrition education and a facilitated group intervention), and found no increase in knowledge from either intervention. However, the assessment tool used may not have been capable of measuring such impacts (Oliveira, 2009). Lastly, Bell and Gleason performed a study in 2007, and found that nutrition education had no significant difference on WIC participants’ food purchasing behavior (Oliveira, 2009).

Oliveira states that the lack of research demonstrating positive effects may partially be related to the low participation rates in WIC’s nutrition education. A study by Fox et al. in 1998 found that large percentages of women failed to attend the required nutrition education sessions. A GAO study also found nutrition education sessions ranged from an average of four to 17 minutes, an inadequate amount of time to make any significant impact on knowledge and changes in behavior (Fox et al., 2998; Oliveira, 2009). In the 2002 report of The WIC Program: Background, Trends, and Issues, it was stated that it is often difficult for working women to access the WIC program. The U.S GAO addressed this concern in 1997 by surveying WIC directors. It was mentioned that working women face various barriers including difficulty reaching the clinic, long waiting times and lack of service during the lunch hour (Oliveira et al., 2002). However, the directors, not the participants were interviewed, so the real access barriers remain unknown. The New York State Department of Health conducted a study to identify barriers from the perspective of the participants. They found that the most commonly reported barriers were long waiting times, overcrowded and noisy clinics with nothing to do for children and nutrition education sessions that were boring and repetitive (Oliveira et al., 2002). This information was reiterated in a focus group conducted in Arizona, in which participants suggested classes and materials that were more engaging for children, a new delivery format for education including interactive demonstrations, and materials that were less time-consuming and met the participants’ needs (Greenblatt, Gomez, Alleman, Rico, McDonald, & Hingle, 2016).

It is important to note the ways in which education can be delivered. Education differs among and between states, and can also be different based on amount of time available to educate, the number of WIC staff available and the WIC employee who is conducting the education. Education may be offered in individual counseling sessions, through group classes, via films and videos or online via the WICHealth.org application. One-on-one nutrition education is available at almost all WIC sites, and 75% of agencies offer group classes and 32% have web-based nutrition education (USDA, 2012). The WIC Nutrition Education Study: Phase I Report (Summary) indicated that one-on-one counseling was the primary method for nutrition education, followed by group and technology-based methods (USDA, 2016). One study examined the effectiveness of an innovative method of nutrition education (a touch-screen video comprised of a five-module curriculum [individual intervention] and curriculum presented through facilitated group instruction focused on behavioral change) compared to traditional education classes. Interestingly, they found that neither the innovative or the traditional intervention increased nutrition knowledge among prenatal clients, though there were several limitations to their assessment (USDA, 2001). It is also interesting to note that the innovative individual educational intervention was more difficult to implement than the group intervention. Any form of individual nutrition education requires extensive resources, planning and attention to implement, monitor and maintain (USDA, 2001).

On the contrary, the WIC Nutrition Education Assessment Study, which examined nutrition education services, participants’ receipt of and satisfaction with these services and changes in knowledge, attitudes and beliefs found more positive results. Overall, they found that knowledge scores significantly increased in all sites between baseline and prenatal surveys (Fox, Burnstein, Golay, & Price, 1998). They deemed WIC nutrition education to be effective in communicating nutrition concepts to program participants. Additionally, participants seemed fairly satisfied, and found the nutrition education and written materials to be useful and interesting (Fox et al., 1998). In a small focus group of WIC participants in Washington State, researchers determined that, “participants expressed an interest in a more interactive approach and new themes for WIC education. Participants said that didactic instruction, with little or no open discussion, discouraged them from returning to WIC for nutrition education” (Birkett, Johnson, Thompson, & Oberg, 2004). Their preferred methods for nutrition education included group classes and print materials that were interactive, participatory, facilitated by knowledgeable staff, useful, exciting and had multiple time offerings and activities for children (Birkett et al., 2004).

It was previously mentioned that nutrition education is a critical component to the many benefits that WIC bestows upon its participants. Though two nutrition education contacts must be offered per certification period (approximately every six months), participants are not required to attend. This has led to extremely low rates of attendance for nutrition education contacts (Fot et al., 1998; USDA, 2001). According to Fox et al. (1998) though 80 to 97 percent of participants were offered to receive two nutrition education contacts during a certification period, the percent of women who actually received both contacts ranged from 24 to 92 percent amongst six different sites (Fox et al., 1998).

It is clear by the minimal, contraindicating and outdated evidence related to WIC nutrition education, that further studies are necessary to determine which methods of nutrition education are preferred by WIC participants, are easiest to implement, are resource-efficient and increase nutrition knowledge the most. The method of education must also be easily accessible by working mothers, encourage child interaction, be conducted in a reasonable amount of time and keep the interest of WIC participants.

Various WIC agencies throughout Riverside County have adopted a new style of nutrition education, termed an education fair, in hopes of improving client participation and nutrition knowledge. Between 1995 and 1996, one study was conducted which examined this innovate style of teaching that involves active client participation (Kowtha & Bruce, 1997). The nutrition fair involved multiple stations with educational activities and games at each station, along with nutrition information. The study determined that the nutrition fair, compared to traditional nutrition education classes resulted in a 15 percent increase in nutrition knowledge with certain booths and up to 30 percent increase in nutrition knowledge was found with the nutrition fair compared to the traditional education provided (Kowtha & Bruce, 1997). The response was extremely positive and participants showed enthusiastic interest in the nutrition fair. The study mentioned that a larger scale study might be initiated in the county (Prince Georges County, MD) soon, though there appears to be no evidence of any such study nationwide. However, this method of education has begun to be readopted by multiple WIC sites in Riverside County, CA. The purpose of the current project was to obtain preliminary data assessing participation and attendance rates, satisfaction, knowledge and active engagement amongst WIC participants in both the traditional classes as well as the newly adopted education fair. Data would be used to determine if time and money should be invested in continually improving the education fair, in addition to research aimed at establishing the effectiveness of WIC nutrition education.

Project Description

Description, Goals and Theoretical Framework

The student carried out her project from July 2017 through February 2018 at the Temecula WIC clinic. The project encompassed various tasks, including observing classes at multiple WIC agencies, developing a survey to compare traditional education classes with the innovative style of teaching, teaching traditional classes, implementing the education fair and analyzing data to determine which style was more effective and which participants preferred.

The main goal for this project was to obtain baseline data to see which form of nutrition education participants preferred and which was more effective in teaching participants about nutrition and healthy living. Another aim was to see if participation increased with the new method of teaching. The data would be utilized by Riverside County, and could potentially be extrapolated to all state and nationwide WIC agencies. The results from this project would provide reference values and indicators to see if this style of education is worth investing time, money and research into. If successful, other agencies may want to adopt this style of teaching, and the State may want to conduct further research to see if it improves interest in nutrition education and nutrition knowledge and improves health outcomes.

The education fairmay have been modeled after the 1995 to 1996 nutrition fair technique (Kowtha & Bruce, 1997). Though it was never clearly articulated, it appears this was the framework from which the new fair was modeled, though other WIC agencies in the county implemented the education fair before the Temecula site. Administration may have decided to adopt this style of teaching based on various other models and studies. The education fair was designed with the intent of being more engaging and allowing children to interact with the booths, as well.

Methodology

The student first observed, then facilitated, multiple didactic classes to understand the process of educating, and to see if participants were interested in learning about nutrition and received the information. Additionally, she attended other agencies’ education fairs to examine different methods of operation and flow. A survey was then developed to assess various indicators the student found to be appropriate and helpful in learning about the differences between the traditional classes and the education fair. Surveys were developed and modified throughout August and September, and distributed to participants at various classes from October through December. Show rates were also evaluated during this time, with the help of all WIC staff. The education fair was set to be implemented starting in January, and educational materials were received from the State close to the start date. The first education fair was held on January 4th, 2018. Fairs were conducted roughly once every two weeks thereafter. Some agencies decided to conduct multiple fairs during the month, only having them in the mornings or in the afternoons, or all day for only one day per month. Temecula WIC conducted their fairs roughly twice per month, for a few hours each day, though changes were occurring to accommodate more participants at the time the student completed her practicum hours.

The nutrition and health topics, as well as the visual material (presented on a tri-fold board) and proposed script, were provided by the State. However, the organization of the education fair varied site to site. Additionally, each site could elect to provide additional handouts and print materials and invite other organizations and referrals from the community to participate in the fair. Though the outlined script was provided by the State, the conversation was still focused on the participant, with the goal of performing participant-centered education (PCE). According to Deehy et al. (2010), “The fundamental spirit of PCE includes working collaboratively, eliciting and supporting motivation to change, and respecting participants’ independent thoughts and actions. Participant-centered education focuses on participants’ capabilities, strengths, and needs, rather than solely on problems, risks, and negative behaviors identified by educators” (Deehy, Hoder, Kallio, Klumpyan, Samoa, Sell & Yee, 2010). The goal of the education fair was to maintain PCE and allow the participant to set her own goals, while using a new approach to teaching.

Though the education topics were provided, each site was allowed to operate their fair however they saw fit. The student observed one site that had groups of five to six participants go around the room to each of the booths. Some sites had a staff member leading the group and facilitating discussion, while others stationed staff members at each booth who led discussions with the participants, either in a one-on-one situation or as a group. Another site allowed participants to come as they wanted and could go to any of the stations they preferred. Participants were encouraged to attend all booths, but were not required to.

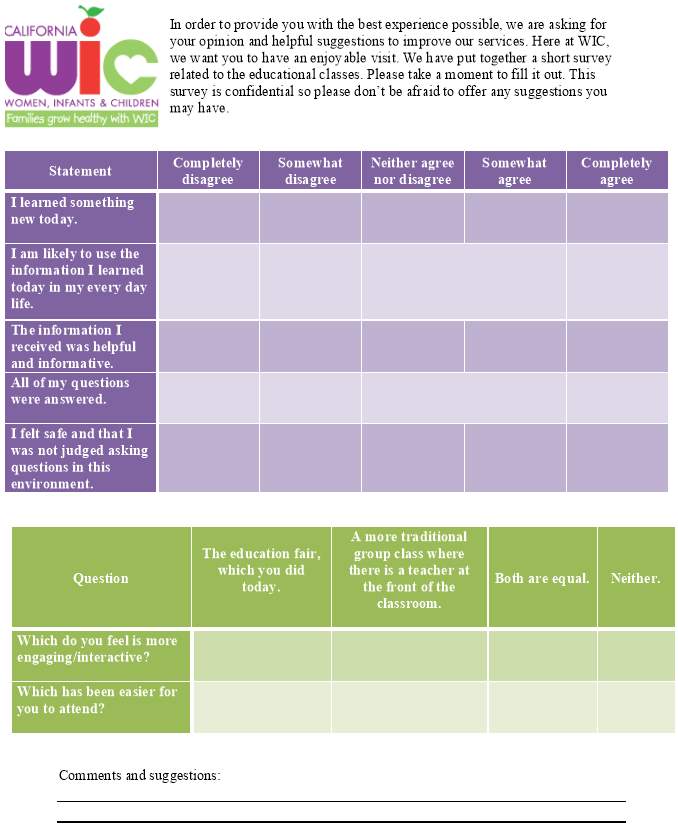

The student created the survey based on previous satisfaction surveys and indicators of interest. The survey included a series of statements that could be ranked on a scale of completely disagree to completely agree. The survey can be found in Appendix A. Before the education fair was implemented, surveys were distributed after traditional didactic group classes. Once the fair was in effect, willing participants completed a survey at the end of the fair. The student used Excel to analyze the number of responses to each question for both the traditional class and the education fair.

Recruitment was not necessary, as participants were automatically signed up to participate in the education fair if typically completed their nutrition education contact in the clinic. Most events occurred at the WIC agency in Temecula, though preliminary research was conducted at other WIC sites in Riverside County to observe operations.

Evaluation Methods

Progress was measured by periodically checking in with the student’s preceptor. The survey was completed with enough time to be given to a number of participants in traditional classes before the education fair began. No official evaluations were conducted. The supervising Registered Dietitian (preceptor) oversaw the project, and communication continually took place, even after the student completed her practicum hours early in February. Additional surveys from education fairs throughout February and March were scanned and sent to the student via email in order to increase the sample size.

Results and Project Summary

The goal of obtaining baseline data comparing the traditional nutrition education class to the education fair was accomplished. The student was able to acquire 59 completed surveys from the traditional class and 70 surveys from the education fair. The cumulative results of these surveys can be seen in Appendix B. Based on feedback from participants, it was clear that the education fair was successful in educating participants about nutrition. Participants “completely agreed” or “somewhat agreed” that they learned something new in the education fair more so than in the traditional class. It also appears that questions were more likely to be answered, and participants felt safer and less judged asking questions in the education fair compared to the traditional class. Sixty percent of participants felt that the education fair was more engaging, compared to six percent who believed the traditional class was more engaging. Thirty-four percent felt that both were equally engaging. It is also interesting to note that 47 percent of respondents felt the education fair was easier to attend, another 47 percent believed both to be equally accessible and only two percent felt the traditional class was easier to attend.

Additionally, show rates drastically varied between the traditional classes and the education fair. On average, only 19 percent of participants showed for their appointments during the traditional class, ranging from zero to 50 percent of people showing for their appointment on a given day. There were multiple incidences where none of the participants who were scheduled came to their appointment. It is worth noting that there was little difference between the show rate for English and Spanish classes. On the other hand, 47 percent of participants attended their appointment when scheduled for the education fair, ranging from 29 to 65 percent of participants attending their appointment. There was a somewhat significant difference between the English and Spanish classes, with 43 percent and 29 percent completing their appointments, respectively, though these numbers are somewhat arbitrary as the show rate was not analyzed based on language for all education fairs. Interestingly, show rates typically continued to improve as the education fair had been implemented longer. Lastly, appointments for online education remained fairly consistent, with an average of 58 percent completing education online when traditional classes were utilized, and 51 percent completing their education online when the education fair was implemented.

A space was provided on the surveys where participants could write comments and suggestions. These can be found in Appendix C. Comments were overwhelmingly positive. Participants thoroughly enjoyed the education fair and the information provided, and appreciated the one-on-one interaction, how quick the fair was and the fun and new approach to learning.

Based on the data previously mentioned, it can be assumed that the education fair was more engaging for participants and was easier for them to attend when compared to the traditional class (based on surveys and show rates) and gave participants the opportunity to learn something new in a safe and interactive environment that they are likely to implement.

Discussion

The results stated above and found in the Appendices clearly articulate the success of the education fair. Participants not only enjoyed this method, but appeared to have greater access to education when conducted in this setting. These results indicate that the organization should continue to implement this style of education. Additionally, this information can be used to persuade administration and other staff to adopt this method of education in other agencies throughout Riverside County and California.

This project contributed to the lacking body of knowledge regarding the effectiveness of nutrition education, by showing that participants are interested and would like to be engaged in nutrition education if the sessions are implemented in appropriate and interactive ways. Additionally, it shows that participation in WIC nutrition education can significantly increase if delivered in an engaging way. This information can be utilized to conduct further studies related to the topic of nutrition education and methods of delivery at WIC agencies.

Though this project was successful in accomplishing its goals, there were several limitations. For instance, because the surveys were completed anonymously, statistical analysis could not be performed to compare before and after results of the education fair on a personal level. However, the purpose of the study was more to gather qualitative data and determine participant satisfaction, rather than obtain quantitative data. Additionally, the questionnaire did not measure an increase in nutrition education by asking questions related to the topic discussed. It was also very difficult to assess true show rates for classes and the education fair, because there were a great deal of individuals who walked in and participated but did not have an appointment. This may have created a false increase in participation rates. Regardless, results were drastic enough that it can be determined there was some effect caused by the change in method of education and availability of appointments. This data also might not be representative of the entire population who uses WIC. Survey respondents were primarily spoke English, and few Spanish-speaking individuals completed surveys. This information must be considered when trying to generalize information to the entire population of WIC users. Additionally, surveys were not distributed after one-on-one counseling sessions, which comprise a large portion of nutrition education sessions. Lastly, data on the show rates for October was lost. Though a significant amount of data was collected in November and December, results may have been strengthened if October data was included in the analysis.

The student would recommend continuing to distribute surveys to participants after the education fair, in order to strengthen the results of the project. Upon obtaining a fair amount of data, it can potentially be presented to WIC administration in hopes of encouraging other sites to adopt this education style, and may lead to research studies that could improve WIC nutrition education. She would also suggest organizing the education fair in different ways. Many participants liked the one-on-one interaction of the education fair, but many individuals missed having other mothers to talk and learn from. The site should adopt multiple styles of operation, for example allowing participants to come and go as they please versus scheduling participants for a facilitated guide, and compare which one participants enjoy best and what is easiest to implement.

If the student could have done anything differently, it would have been enforcing WIC staff to distribute surveys more and reassuring them how important this information would be. The student was unable to attend every class and fair, and the staff did not always distribute the questionnaires to all participants. Additionally, surveys would have been distributed to participants who completed one-on-one education, as well. Again, having a greater number of surveys would have strengthened the results of the study. The student would have also included a few questions related to the topics discussed in order to assess an increase in nutrition knowledge with the traditional class setting versus the education fair. A question regarding the ability for child to participate in education would also have been included.

Though the student’s portion of the project was completed, she strongly encourages the agency to continue collecting data on this topic. Depending on results, in may pave the way for further research or change the way WIC nutrition education is implemented throughout the state and nation.

Personal Reflection

The student learned an incredible amount during her time at WIC. Most importantly, she was humbled after hearing participants’ stories, and became even more grateful for the people in her life. She gained a new perspective of what it means to be “low-income” and feels she better understands the struggles and strengths of this population. Additionally, she learned about the different duties of being a supervisor, and was allowed to perform some of these tasks. She discovered the supervising Registered Dietitian plays a much different role in WIC than she had expected. She also realized how difficult it is to create a good survey and to actually obtain thoroughly and accurately completed surveys. Lastly, she discovered she is passionate about helping this population and one day wants to work in WIC administration so she can conduct research and implement new and improved protocols to better improve health outcomes of women, infants and children.

The student greatly appreciated having an extended period of time (roughly six months) to complete her practicum experience, and would highly recommend this to any student who can do so. She was able to experience the changes that occur within an organization over time. The preceptor gave the student great responsibility in this project, while providing support and advice as necessary, which significantly improved the student’s learning experience. She was able to participate in many different projects and assignments and get a feel for all that WIC is. No limitations of the experience were noted.

The knowledge gained during this experience have assisted the student in realizing she would like to become a lactation consultant, and one day work in WIC administration. These career paths may never have been established without the wonderful experience she had while at WIC.

References

Birkett, D., Johnson, D., Thompson, J. R., & Oberg, D. (2004). Reaching low-income families:

focus group results provide direction for a behavioral approach to WIC services. Journal of

the American Dietetic Association, 104(8), 1277-1280.

Deehy, K., Hoger, F. S., Kallio, J., Klumpyan, K., Samoa, S., Sell, K., & Yee, L. (2010).

Participant-centered education: building a new WIC nutrition education model. Journal of

nutrition education and behavior, 42(3), S39-S46.

Food and Nutrition Service. Women, Infants and Children (WIC). (2015). Retrieved from

https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/about-wic-wic-glance

Food and Nutrition Service. Women, Infants and Children (WIC). (2018a). Retrieved from

https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/about-wic-wics-mission

Food and Nutrition Service.Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). (2018b). Retrieved from

https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/women-infants-and-children-wic

Fox, M. K., Burstein, N., Golay, J., & Price, C. (1998). WIC Nutrition Education Assessment

Study Final Report. Retrieved from

https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-nutrition-education-assessment-study

Greenblatt, Y., Gomez, S., Alleman, G., Rico, K., McDonald, D. A., & Hingle, M. (2016).

Optimizing nutrition education in WIC: Findings from focus groups with Arizona clients and

staff. Journal of nutrition education and behavior, 48(4), 289-294.

Kowtha, B. J., & Bruce, C. J. (1997). Nutrition Fair: An Effective Nutrition Education Tool in

the WIC Setting. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 97(9), A59.

National WIC Association. WIC Program Overview and History. (n.d.). Retrieved from

https://www.nwica.org/overview-and-history

Oliveira, V. J. (2009). The WIC program: background, trends, and economic issues (No. 73).

DIANE Publishing.

Oliveira, V., Racine, E., Olmsted, J., & Ghelfi, L. M. (2002). The WIC Program: Background,

trends, and issues (No. 33847). United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research

Service.

USDA Economic Research Service. WIC Program. (2017a). Retrieved from

https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/wic-program/background/

USDA Economic Research Service. WIC Program. (2017b). Retrieved from

https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/wic-program/

USDA. (2012). National Survey of WIC Participants II Report Summary. Retrieved from https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/NSWP-II_Summary.pdf

USDA. (2001). WIC Nutrition Education Demonstration Study: Final Report Child Intervention. Retrieved from https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-nutrition-education-demonstration-study-child-intervention

USDA. (2016). WIC Nutrition Education Study: Phase I Report (Summary). Retrieved from

https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/WICNutEd-PhaseI-Summary.pdf

WIC. (2018). Retrieved March 31, 2018 from the WIC Wiki: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WIC

Appendix A

Education Fair Survey

Appendix B

Results

Appendix C

Comments and Suggestions from Distributed Surveys

| Traditional Class | ||

| Positive Feedback | Suggestions for Improvements | General Comments/ Up for Interpretation |

| I completely agree to the class today and I want to apply it to my son. I learned how important to build self-esteem to a child | Thank you for talking about a developmental topic! I would like to see more like this. Suggestion: short ice-breaker activities to encourage more conversation | A great activity for all the WIC members. It really helps. God bless you all. Have a good day! |

| I am grateful for this program and handouts and friendly faces. Always feel welcome and better prepared after I leave | Teacher not call people out if they have nothing to say, makes them uncomfortable | Thank you for taking the time out of your busy schedule to do these classes! |

| The class was very good and I really appreciate it | I like interactive classes | I love the WIC program |

| Thank you, I learned something new today! | I wish classes started on time | All the WIC staff is awesome! Love you guys! |

| Good information | Good info. Handouts would help to take info home | Thank you |

| The lecture was great! | Larger groups | Great |

| The lady who gave the class was very helpful and awesome | You guys go a great job | |

| I love how I always get positive information from WIC. It always feels good to hear it especially with newborns. You’re reminded that you’re all doing it together | I recently moved from North County and was going to the San Marcos office. No complaints there the staff is lovely. This office is just as wonderful. Thank you | |

| I love that the teacher uses her personal life in her examples. It makes it more personal | ||

| Very helpful class | ||

| Education Fair | ||

| Positive Feedback | Suggestions for Improvements | General Comments/ Up for Interpretation |

| I liked having the one-on-one interaction because I’m very introverted, so I was a little more comfortable | Like the classes because [I] can talk with other moms about problems or topics related to [my] child | They were really nice and approaching |

| This was an interesting new way to do the class and learn about multiple healthy topics. I liked the range of topics and the way they were presented | All stations should be included in education fair class, otherwise doesn’t reach potential (easy fix). Thank you | I enjoyed today’s education fair! Very good information provided. Everyone was very friendly and helpful. Thank you! |

| Loved it. Very helpful. Ladies were making me feel comfortable to ask and be helped | I like group sections because we can interact and hear other moms’ experiences | First time for education materials |

| The fair was quick, easy and personal | Ladies did great with the information they gave | |

| Very knowledgeable and helpful | Learned about fitness video and sites for toddlers | |

| I liked the fair. Meal planning was my favorite. I would attend more. | ||

| Enjoyed today’s fair | ||

| The fair is a great idea! It’s great to have one-on-one interaction | ||

| [The education fair makes it] much better with the baby | ||

| The [fair] was informative and educational | ||

| Great info and idea. I enjoyed this class | ||

| Today’s experience was new and I love it. It’s quick yet very informative | ||

| Pamphlets of information always are great. Direct and comprehensive information. Thank you | ||

| I love more one-on-one, being able to ask questions. All of my questions were answered. | ||

| I like the education fair because it’s more one-on-one and visual | ||

| It’s all very informative. Will be reviewing the packets I got and applying it | ||

| I love the education fair. It’s more educational. You learn more and interact | ||

| Really liked choices on boards and other questions I had were answered | ||

| I like the education fair because it’s more one-on-one | ||

| This set up feels more relaxed and welcoming. A fun approach to learning | ||

| It was good because we can move and keep going | ||

Appendix D

Met Competencies Inventory

Analytical/Assessment Skills

|

| How did you meet it in your field practicum? |

| The student created a survey to compare participants’ opinions toward the nutrition education component for the traditional class vs. the education fair. All surveys were completed anonymously, and results were only used within the organization. The student also researched and developed multiple presentations on drug abuse, post-partum mental health and marijuana use during pregnancy and breastfeeding, which included researching characteristics of these public health issues. |

Policy Development/Program Planning Skills

|

| How did you meet it in your field practicum? |

| The main purpose of the student’s project was to obtain data that may influence the implementation of nutrition education in all WIC agencies. With the data that was obtained, administration will determine whether or not to continue this style of education, and whether or not to disseminate findings to other agencies and have them adopt this method of teaching, as well. The student also attended multiple RD meetings with WIC RDs throughout Riverside County. Policy updates, changes that are occurring, and changes that need to occur in policies and programs were frequently discussed. The student also read various materials on policies and program planning and implementation within WIC and other public health programs. |

Communication Skills

|

| How did you meet it in your field practicum? |

| The student developed and shared multiple presentations in small (4-5 attendees) and large (30+ attendees) group settings. The student presented material at staff meetings, RD meetings and at various educational sessions in multiple settings (at the WIC agency and the mental/behavioral health clinic), and through various means of communication (speaking, printed materials, visual presentations, etc.). The student participated in many nutrition education sessions (individual and group), and performed active listening and participant-centered education in order to set goals the participant deemed important. The student also developed an infographic to be utilized by WIC administration at upcoming meetings throughout the year. |

Cultural Competency Skills

|

| How did you meet it in your field practicum? |

| The student had to complete a shopping trip using WIC vouchers, which allowed her to appreciate the program from the perspective of a participant and experience how it feels to participate in the program. She communicated with and educated individuals of very diverse backgrounds on a daily basis. She developed many presentations on sensitive topics and had to be culturally aware when presenting them to various individuals and groups. |

Community Dimensions of Practice Skills

|

| How did you meet it in your field practicum? |

| The student developed a presentation on Rethink Your Drink and educated a group attending the mental/behavioral health clinic. The student attended multiple Inland Empire Breastfeeding Coalition meetings and gathered information to be utilized in the WIC agency to better promote breastfeeding, mental health, and other aspects of health. The student indirectly learned about stakeholders, community assets and resources when developing an infographic for WIC administration. |

Public Health Sciences Skills

|

| How did you meet it in your field practicum? |

| The student researched many different topics related to public health (mental health, drug abuse, marijuana use during pregnancy and breastfeeding, nutrition education) and translated the scientific evidence and public health concerns related to each topic to various individuals and groups. The student also examined and explained the limitations of the research to date on the previously mentioned topics. She also examined the limitations to her own “research findings.” She contributed to building the scientific base with her project, in hopes of the findings being disseminated throughout Riverside County and beyond to improve WIC nutrition education. |

Financial Planning and Management Skills

|

| How did you meet it in your field practicum? |

| The student adhered to the organization’s policies and procedures on a daily basis. The student conducted various quality assurance/ performance measurements on WIC staff, and observed managerial meetings to discuss performance assessments with staff. The student observed management conduct staff meetings to resolve internal conflicts. The student observed and participated in management’s role in training of new staff. |

Leadership and Systems Thinking Skills

|

| How did you meet it in your field practicum? |

| The student gave nutrition advice as was deemed ethical and appropriate, and did not participate in any advice or education that was beyond her scope of practice. She developed and presented multiple inservice trainings/topics and had the opportunity to teach her peers, while also receiving positive feedback and critiques from them. She also learned from other staff’s information and presentations. The student also conducted multiple performance assessments on staff to improve the quality of organizational performance. The student worked in a team setting on various occasions. |

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Community Health"

Community Health is the field of public health that concerns itself with the health and wellbeing of residents within a particular area, taking into account environmental and infrastructural factors.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: