Challenges of Having Smartphones in Residential Treatment Centers

Info: 6759 words (27 pages) Introduction

Published: 17th Nov 2021

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

This dissertation will be based on a qualitative Delphi methodology, on Smartphones in Residential Treatment Centers and the increase in security breaches. The evolution and integration of Smartphones suggests several security risks for organizing data, such as patient health information (PHI) and personal identification information (PII) (Gartner, 2013). This chapter will discuss the background of the study; it focuses on the increase in security breaches and the challenges that Smartphones have in Residential substance abuse and behavioral health treatment centers. The Diffusion of Innovations (DOI) model is one of the frameworks that will be used to examine these factors. The Diffusion of Innovations (Rogers, 2003) theory explains how innovations are adopted and communicated by others.

The increase in Smartphone security breaches at Residential Treatment Centers raises concerns and the risk of sensitive data to be stolen (Stiakakis, Georiadis, & Andronoudi (2016). As the industry has seen an increase in security breaches a critical decision to enhance security in Smartphones at Residential Treatment Centers. This forms the background against which the literature review will be based. It also discusses the business and technical problem which is the problem statement of the study indicating that the business problem Smartphones in Residential Treatment Centers and the increase in security breaches.

The chapter also discusses the research purpose based on the facts that there is no doubt that Smartphones and other related mobile devices have been identified as flexible, available and powerful tools used for human cognition and behavioral trends. However, the habitual involvement with the mentioned devices has triggered various perceptions whereby some users are well convinced that Smartphones have positive influences on all sectors including the health sector while other view Smartphones as a health risk and a significant cause of diseases such as cancer (Abu-Shanab & Haddad, 2015). The author further states that Smartphones have resulted in mental and psychological dysfunction in some users. The suggested convenience and speed of Smartphones used in Residential Treatment Centers servicing behavioral health and substance abuse clients directly conflicts with the privacy and security of the information these devices store and transmit. Storing and exchanging Personal Health Information (PHI) via Smartphones poses privacy and security issues based merely on the portable nature of these devices.

The very asset of Smartphone technology is also a weakness, as the data collected and stored in Smartphones reveal information about the user ranging from a physical location and the user’s habits to sensitive health information. The issue becomes more complicated when such information is inadvertently or coarsely disclosed or captured by others, and many times used for the purposes not intended (Finn, 2011). According to another scholar (Elgan, 2012), another concern is the use of Smartphones as surveillance applications that many times are downloaded without the user’s knowledge. The surveillance technology triggers more information from a person’s phone, either on health care or other related fields, this pose additional security concerns which results in breach of data.

According to experts in information technology, limitation of the number of applications that are installed would influence lesser hacking of information from the Smartphones (Tofighi et al., 2017). Other elements in this chapter are the research questions which will be used to collect the data. The rationale of the study, which provides the justification and the need of the study, which is to protect those who use Smartphones. The chapter also tackles the theoretical framework, significance of the study as well as definitions of the terms that will be used in this chapter and finally the organization of the remainder of the study.

Background

The goal of this study is to understand the challenges of having Smartphones in Residential Treatment Centers. In the United States, the adoption and use of mobile technologies are growing Granter (2014) projects that Smartphone technology will be the primary technology for over 50% of the users in 2018. Growth and the use of Smartphone technology in the global workplace may soon exceed $284 billion by 2019 (Mastroberte, 2014). This represents a change in the way that Residential Treatment Centers operate, communicate, and service clients. Very few organizations are, technically, operationally, and socially prepared for the change that Smartphones bring (Kim, 2012; Kuyatt, 2011; Marshall, 2014). Privacy of individuals in a Residential Treatment Centers needs to follow strict regulation guidelines that consist of 42 CFR Part 2, HIPPA, HITRUST, and Joint Commission Regulations According to (Lafferty, 2007). Technology advancements over the past few years have driven our culture to a more digitized working environment.

President George W Bush signed an executive order on April 27th, 2004 to implement a Nationwide Health Information Technology (HIT) framework within 10 years (Lafferty). President George W Bush directive was to deliver a more modern digitalized Electronic Health Record (EHR). Smartphones have transformed health care practices, and providers have found that with the introduction of Smartphones they can deliver streamlined processes, optimizing efficiencies, and improve patient outcomes (Idemudia & Raisnghani, 2014).

The question that needs to be asked is what cost and what are the risks associated with using Smartphone technology. The continued growth of malicious software such as malware that can track user’s sensitive personal information, such as PHI (Stiakakis, Georgiadis, & Andronoundi, 2016). The current governing bodies, 42 CFR part 2, HIPPA, and HITECH have not been able to evolve with technology and give the necessary guidance and proper direction around the controls and expectations. The problem lies with legislative provisions which have not been able to keep up with advances in technology. The growth of Smartphones being able to collect data is a growing concern (Birnbaum et al., 2015).

The industry is fully aware of their challenges, but having a governing body to assist and to develop appropriate security frameworks around Smartphones is a critical component as we continue to develop ways to have Smartphones in the Healthcare realm but having proper protocols protecting our patients’ data (Lee et al., 2014). Mobile phone health application systems are known to be increasing at a phenomenal speed (Zahra, Khalid, & Javed, 2013). More so, the fact that there is an advanced technological platform is reason enough to initiate protection against security breaches.

Business Technical Problem

Security breaches within Smartphones have become widespread within our Healthcare industry, but the effects are more significant for those that are bound to follow regulations 42 CFR part 2 guidelines (Safavia & Shukur, 2014). 42 CFR part 2 rules are stricter than Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA). 42 CFR part 2 deals with behavioral health and substance abuse clients that. Current policy around HIPPA and 42 CFR part 2 shows that there is no policy enforcement around Smartphones (Willaims, 2014). Even though current guidelines state the protection of PHI is required (Wilkes, 2014), it is fair to say technology has evolved to the point that the Joint Commission is not able to react quickly enough to all of the technology advancements. The risk of a security breach on a Smartphone, further jeopardizes clients PHI and PII in a Health Care Industry. Security breaches are front-and-center to HIPPA and 42 CFR part 2 (Clark, 2015).

The HIPPA security awareness, through the advanced policies and regulations of the Act, will ensure sustainability and consistency in the practice of confidentiality within the residential treatment centers. Unfortunately, the evolving of technology has led to most of the health practitioners not observing confidentiality. Besides, with the knowledge of patients going through surveillance system through their mobile devices, the communication and information required would not be achieved, because the information is already biased and, in that case, not genuine. According to the Patient Health Information policies and regulations, it is affirmed that every patient should give consent before any information is drawn from their files, in every possible way that the process is conducted. Interestingly, the professionals from the residential care systems do not practice and take this into account. The specific business problem is the increase in security breaches, International Data Corporation predicts that by 2020 more than 1.5 billion will be affected by a security breach (Leech, 2017).

Research Purpose

The purpose of this qualitative Delphi research study is to develop a possible model to reduce security data breaches on Smartphones by interviewing 15-20 security experts in Residential Treatment Centers in the United States. The Diffusion of Innovations theory (Rogers, 2003) and the framework for this study concerning each stakeholder concerns around the adoption of Smartphones in Resenditail Treatment Centers. Participants in this research study were identified as those individuals in Information Technology positions that are responsible for Residential Treatment Centers that can control Smartphones in Residential Treatment Centers in the United States.

Participants in this Delphi Research study were representative of technology decision-makers from the United States, Residential Treatment Centers with less than 1500 employees per site and treat a minimum of 15 patients per month. Participants selected for this research study will be sent an invitation to participate in the online survey. The results of the research study can provide insight into a direction to prevent security breaches in Residential Treatment Centers.

Research Question

The use of Smartphone within a Residential treatment is a growing issue that organizational leaders will eventually confront (Totten & Hammock, 2014). The growth and use of Smartphones within Residential treatment centers will continue to rise, and decision makers will have to react to the issues that are associated with Smartphone technology (Elwess, 2013; Flaten, 2014).

The research question(s) that will guide this Delphi study are:

RQ1. What risks are of greatest concern to the stakeholders regarding the use of Smartphones in Residential Treatment Centers?

RQ2. What is the positive as well as negative consequences of security measures for individuals in Residential Treatment Centers?

Rationale

The rationale for conducting the Delphi study was to understand the increase in security breaches on Smartphones. A Delphi method permitted a focused approach to assess a specific group of experts (Skulmoski et al., 2007). The participants of this Delphi study were solicited from Residential Treatment Centers across the United States. The desired group provided access to a broad range of talented and qualified candidate for this Delphi study while many of which have already addressed the use of mobile technology within their own organization. Skulmoski, et al, (2007) recommends that the ideal Delphi panel should consist of 10-20 participants, with one to six rounds of interviewing with at least a minimum of three rounds conducted to provide adequate results for a conclusion.

The selected group of experts will need to meet the four required requirements to be an expert to participate. These requirements include:

a) willingness to participate;

b) knowledge and experience with the issue;

c) effective communication; and

d) sufficient time to participate (Skulmoski et al., 2007)

The Delphi study will include at least three rounds of questions with the first directly focusing on the challenges that Smartphone raise in Residential Treatment Centers. The subsequent rounds will focus on the risks of security breaches and how each expert formulates their decision if they’re to allow Smartphones in Residential Treatment Centers.

The data responses will be gathered by using the form of SurveyMonkey.com this is a hosted online survey tool that is accessible with any internet connection. The qualitative data for each of the rounds will provide the analysis at the end of the research to present in the chapters to follow in this dissertation.

Theoretical Framework

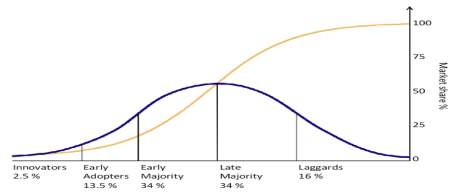

Innovator theory according to (Les, 2009) seeks to illustrate how innovations are taken and utilized by our society who are the users. Les (2009), defines an innovation as an idea that is new and comes with the need to change how the population carries out their activities. The recent increase in technology use has seen innovation in many sectors that are aimed at improving quality of life to users. Another author (Isada & Isada, 2014) is in agreement that classic innovator theory is more relevant in understanding the theory of Diffusion of Innovation in technology such as the use of Smartphones. Factors that affect the spread of diffusion of technology includes the quality of the technology, the needs that the technology fulfills and what peers are targeted by innovation feel about a product (Les, 2009).

This theory can be further explained by the use of Rogers Everest theory. The categories of diffusion include the innovator, opinion leader, early majority, rate majority, and laggard.

According to a recent publication by On digitalMarketing.com (2015), Innovators refer to the first group of people to adopt a new technology. They are willing to take risks. Their risk tolerance levels are high and allow them to invest in technologies that may fail (Isada & Isada). The early adopters are the category of people that adopt technology after the innovators, they are characterized by a high percentage of opinion leaders, they are easily influenced by peers such as the youth, and they are also more social forward. The early majority groups are slower in adopting new technology, although they are also of high financial and social status. Late majority approach new technology with a high rate if skeptics, they fear risks due to their low financial status. Finally laggard’s categories are those who fear change and are slow to accept new technology OnDigitalMarketing, com (2015). When a company is targeting an innovative introduction. It should first understand what category the targeted population is as this will majorly affect the adoption of the new technology.

Advancements and the accessibility to technology innovations have now enabled all users to drive technology innovations in organizations (Dernbecher, Beck, & Weber, 2013). The stakeholders need to determine what is the best course for their organization and yet satisfy the needs of the end users within your organization. This decision process is not repeatable for all stakeholders and they may evaluate different innovation characteristics before making a decision to adopt or even reject the use of mobile technologies in their organization.

The theoretical approach associated with this research is that Diffusion of innovation idea to incorporate Smartphone technology in Residential Treatment Centers. The Diffusion of Innovation provides a relevant lens for this Delphi research study since this has been used in several published studies (Rogers, 2003). Rogers (2003) identified the five levels as persuasion, implementation, knowledge, decision, and confirmation. The focus of this research will directly focus on knowledge, persuasion, and decision. The use of Smartphones technology in an organization is a social process for end users drive technology and they even try to influence organizational stakeholders to allow this to occur (Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, 2015). The Delphi method is an accepted approach since it is dealing with uncertainty with limited knowledge (Skulmoski at el., 2007).

Significance

This Delphi study will focus on evaluating the adoption of Smartphone technologies as security breaches continue to increase (Cegielski et al., 2013). Cegielski et al. (2013) used the theory Diffusion of Innovation to evaluate influences organizational Stakeholders to adopt innovations. Our culture has seen an increase in technology and has opened new risks for PHI. As Smartphones become the norm in organizations as of 2014, 62% of Smartphones were used to look up patient health information (Lee, 2016). Current government regulation, such as HIPPA, HITECH, 42 CFR Part 2 have not been updated policy on protecting Smartphones as quickly as technology has advanced over time (Insel, 2017). Our medical field has seen a need to use mobile devices. Smartphones in today’s age are as powerful as some computers and can do many of those functions rather than just being a device to make a call. Smartphones have become a universal device and industries need to adapt to those changes, but weigh the risks of security breaches with patient data (Jeong, 2017). This research has the possibility to influence Stakeholders if the use of Smartphones in Residential Treatment Centers warrants adoption even though the increase of security breaches.

Definition of Terms

For clarity and consistency, some of the keywords used in this study are defined as follows.

42 CFR Part 2. Commonly referred to as “Part 2”) are the federal regulations governing the confidentiality of drug and alcohol abuse treatment and prevention records. The regulations set forth requirements applicable to certain federally assisted substance abuse treatment programs, limiting the use and disclosure of substance abuse patient records and identifying information. 42 CFR Part 2 is a decade old regulation with complex patient consent requirements at times which make it very difficult or impossible for patients and providers in these care settings to share patient data related to substance use disorders (SUD) and co-occurring physical and behavioral health conditions (42 CFR part 2 updates would improve access to care without compromising patient privacy, 2015).

Breach. Data breach is when an incident of sensitive, protected or confidential data has potentially been viewed, stolen or used by an unauthorized person. Data breaches can involve personal health information (PHI), or extend to personally identifiable information (PII) (What is a data breach? – Definition from WhatIs.com., n.d.).

Bring Your Own Device (BYOD). This is when employees use non-corporate owned devices, including their own software to access company resources within or outside the environment of their organization (Ghosh et al., 2013).

Chemical Dependency / Substance Abuse. Chemical dependency and substance abuse is a medical term used to describe a pattern of using a substance drug that causes significant problems or distress (Substance Abuse/Chemical Dependency, n.d.).

Cloud. Is the ability to provide flexible, on-demand and elastic computing power to an organization. The Cloud concept and idea have been a very attractive and growing business. In this day and age, it is next to impossible for businesses not to come across the concept of cloud computing “Implement Cloud to Survive” is the call you get from the experts. Besides, through the approach of cloud computing, the ascertaining of different applications and information from the mobile systems is faster and simpler (Wilmer & Sherman, 2017). The advent of cloud computing is a direct result of such technological transformations (Aleem & Antwi-Boasiako, 2011).

Electronic Health Record (EHR). Is a real-time individual health record with access to evidence-based decision support tools that can be used to aid clinical decision making (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007). The electronic health record has the potential for sharing health-related information, among providers and facilitates the flow of the information as the client engages in various modalities of care throughout the health care system and treatment (Garets & Davis, 2006).

Encryption. The process of converting data to an unrecognizable or encrypted form. Encryption is commonly used to protect sensitive information so that only authorized parties are allowed to view (Koukouvinos & Simos, 2013)

Enhanced Mobile-Device Security (EMDS). Even articles that dealt explicitly with mobile-device security (Harris & Patten, 2014; Jones & Heinrichs, 2012) neglected to define the term, possibly assuming that the meaning of mobile-device security was intuitively obvious. Enhanced mobile-device security (EMDS) is defined for the purpose of this study as any practice, device setting, or software added to an out-of-the-box, tablet or smartphone that improves its base security profile (Gass & Foden, 2017). This can be as simple as switching on the password-locking function, turning off automatic Bluetooth discovery, limiting access of applications to location services, photos, or contact lists, or setting a smartphone to erase itself after a certain number of failed password attempts. It can also be as complicated as installing third-party software that encrypts text messages, phone calls, and web browsing. The most expensive security enhancement would be to purchase a smartphone with hardened security already installed, such as the CryptoPhone or Blackphone ( Becker, 2017). The use-behavior of enhanced mobile-device security is operationalized as the number of security behaviors used multiplied by a Likert-type scale score of the frequency of use. This will be the dependent variable called enhanced mobile-device security level (EMDSL).

Health Information Portability and Accountability Act 1996 (HIPPA). An actto amend the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 to improve the portability and continuity of health insurance coverage in the group and individual markets, to combat waste, fraud, and abuse in the health insurance and health care delivery, to promote the use of medical savings accounts, to improve long-term care services and coverage, to simplify the administration of health insurance, and for other purposes (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, 2006).

Health Information Trust Alliance (HITRUST). Alliance founded in 2007, is for a not-for-profit organization whose mission is to champion programs that will safeguard sensitive information and manage risk for organizations across all industries (About Us, 2017).

Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH). The legislation created to promote the adoption and meaningful use of health information technology in the United States. Subtitle D of the Act provides for additional privacy and security requirements that will develop and support electronic health information, facilitate information exchange, and strengthen monetary penalties. Signed into law on February 17, 2009, as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (Public Law111-5, 2009) (AHIMA, 2014b, p. 69).

International Organization for Standardization (ISO). This is a worldwide federation of national standards which encompasses 100. The International Organizational for Standardization (ISO) is a non-government organization, to establish and promote the development of standardization and related activities in the world (International Organization for Standardization, n.d.)

Joint Commission. Is an independent, not-for-profit organization, the Joint Commission accredits and certifies over 21,000 health care organizations and programs in the United States (What is Joint Commission? – Definition from WhatIs.com, n.d.)

Mobile Device Management (MDM). Is a software that provides the following functions; software distribution, policy management, security management and service management for smartphones and other mobile devices (Mobile Device Management (MDM), 2012).

Mobile Information Management (MIM). This is focusing on securing critical corporate information. The primary purpose behind MIM is to store enterprise information on a central location, potentially cloud, then share it with different endpoints in a secure manner (Eslahi et al., 2014).

Protected Health Information (PHI). Can be defined in 45 CFR 160.103, where CFR means Code of Federal Regulations and is as defined and referenced in Section 13400 of subtitle D privacy of the HITECH Act (Jones, 2009).

Smartphone. A handheld device that integrates mobile phone capabilities with the more common features of a handheld computer (Lenhart, 2012).

Assumptions and Limitations

The assumption of the Delphi research study would include that all selected participants would be available for all rounds of questions. The second would be that the size of participants would remain the same to the end of questions. The third assumption would be that all the responses are valid and professional phrased that each participant would be a subject matter expert (SME) in their field.

Assumptions

General Methodological Assumptions

A general methodological assumption was the research study that a qualitative methodology and a Delphi design are the appropriate course of action for answering the research problem and questions. The Delphi technique is a reliable vehicle in getting consistency from experts that was desirable for participants and researcher.

Limitations

Design flaw limitations

This Delphi research study focuses on a specific population because the prerequisite for participants were required to be an expert in Information Technology at Residential Treatment Centers in the United States. Skulmoski (2007), suggested that for a homogeneous group, as the one being used for this research study, 10 to 20 participants might be sufficient. Information Technology Delphi dissertations had an average sample size of 15 participants (Skulmoski).

Organization for Remainder of Study

Chapter 1 includes the background of the study, business, technical problem, research purpose, research question, theoretical framework, and definition of terms.

Chapter 2 is a review of available literature on Policies and Governance around Smartphones. The chapter includes analyses and syntheses of relevant scholarly sources that provide support for the purpose of the current study. Besides, the chapter initiates different approaches that the government has taken to safeguard mobile surveillance while at the same time, use different models to protect the information of the patient.

Chapter 3 discusses the research methodology and design of the study. It includes a process plan for participant selection, data collection, data analysis, and the proposed method for addressing bias and validity in the study. The chapter also explores the role of standardization and how this may be applied to curb biases in the study.

The step-by-step account of the data collection and analysis process is presented in Chapter 4, to ensure each account of the patients’ information collected within a specific period, and in which residential treatment center.

The results and findings are provided in Chapter 5.

REFERENCES

42 CFR part 2 updates would improve access to care without compromising patient privacy. (2015, Oct 06). Business Wire Retrieved from http://library.capella.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.library.capella.edu/docview/1719242629?accountid=27965

Aleem, A. and Antwi-Boasiako, A. (2011), “Internet auction fraud: the evolving nature of online auctions criminality and the mitigating framework to address the threat”, International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, September (special edition Fraud Management)

American Health Information Management Association. (2014b). Pocket glossary of information management and technology. Chicago, IL: AHIMA Press.

Becker, S. J., Hernandez, L., Spirito, A., & Conrad, S. (2017). Technology-assisted intervention for parents of adolescents in residential substance use treatment: protocol of an open trial and pilot randomized trial. Addiction science & clinical practice, 12(1), 1.

Behrens, E., Santa, J., & Gass, M. (2017). The evidence base for private therapeutic schools, residential programs, and wilderness therapy programs. Journal of Therapeutic Schools and Programs, 4(1).

Birnbaum, D., Borycki, E., Karras, B. T., Denham, E., & Lacroix, P. (2015). Addressing public health informatics patient privacy concerns. Clinical Governance, 20(2), 91-100. Retrieved from http://library.capella.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fsearch.proquest.com%2Fdocview%2F1696177957%3Facc

Capron, D. W., Bujarski, S. J., Gratz, K. L., Anestis, M. D., Fairholme, C. P., & Tull, M. T. (2016). Suicide risk among male substance users in residential treatment: Evaluation of the depression–distress amplification model. Psychiatry research, 237, 22-26.

Elwess, T. (2013). Bring your own device (BYOD). (Masters thesis). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. (UMI No. 1550056).

Eslahi, M., Naseri, M. V., Hashim, H., Tahir, N. M., Saas, E. H. M. (2014), “BYOD: Current state and security challenges”, in 2014 IEEE Symposium on Computer Applications and Industrial Electronics (ISCAIE), IEEE, pp. 189-192

Flaten, A. (2014). Undergraduate business faculty beliefs about the critical success factors in the adoption of mobile technology in the college classroom. (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. (UMI No. 3645127).

Gass, M., Foden, E. G., & Tucker, A. (2017). Program Evaluation for Health and Human Service Programs: How to Tell the Right Story Successfully. In Family Therapy with Adolescents in Residential Treatment (pp. 425-441). Springer International Publishing.

Garets D , Davis M, (2006). Electronic medical records vs. electronic health records: Yes, there is a difference. Chicago, IL: HIMSS Analytics. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2007). Recommended requirements for enhancing data quality in electronic health records, final report. Retrieved from www.export.gov/safeharbor

Ghosh, A., Gajar, P. K., Rai, S. (2013), “Bring Your Own Device (BYOD): Security Risks and Mitigating Strategies”, Journal of Global Research in Computer Science, Vol. 4 No. 4, pp. 62-70

Habibi, A., & Sarafrazi, A. (2014). Delphi Technique Theoretical Framework in Qualitative Research. The International Journal Of Engineering And Science (IJES),3(4), 8-13. Retrieved February 3, 2018, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Arash_Habibi2/publication/272177606_Delphi_Technique_Theoretical_Framework_in_Qualitative/links/56857a1d08ae1e63f1f36604/Delphi-Technique-Theoretical-Framework-in-Qualitative.pdf.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, 42 U.S.C. § 1320d et seq. (2006).

Health Insurance Reform: Security Standards, 68 Fed. Reg. 8334 (proposed Feb. 20, 2003) (to be codified at 45 C.F.R. pt. 160, 162, and 164). About Us. (2017, November 13). Retrieved November 23, 2017, from https://hitrustalliance.net/about-us

Idemudia, E. C., & Raisinghani, M. S. (2014). The influence of cognitive trust and familiarity on adoption and continued use of smartphones: An empirical analysis. Journal of International Technology and Information Management, 23(2), 69-IV. Retrieved from http://library.capella.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fsearch.proquest.com%2Fdocview%2F1686532722%3Fac

Insel, T. R. (2017). Digital Phenotyping: Technology for a New Science of Behavior. Jama, 318(13), 1215-1216. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2654782?redirect=true

Ingram, I., Kelly, P. J., Deane, F. P., Baker, A. L., Lyons, G., & Blackman, R. (2017). An Exploration of Smoking Among People Attending Residential Substance Abuse Treatment: Prevalence and Outcomes at Three Months Post-Discharge. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 13(1), 67-72. http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3816&context=sspapers

International Organization for Standardization. (n.d.). Retrieved November 23, 2017, from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/International Organization for Standardization

Jeong, S., & Breazeal, C. (2017, March). Toward Robotic Companions that Enhance Psychological Wellbeing with Smartphone Technology. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2017 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (pp. 345-346). ACM. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b07e/bab38437cba4c49a8e961bc4ef0f6b76e711.pdf

Jones, A. E. (2009, September 01). HIPAA ‘Protected Health Information’: What Does PHI Include? Retrieved November 23, 2017, from https://www.hipaa.com/hipaa-protected-health-information-what-does-phi-include

Kazemi, D. M., Borsari, B., Levine, M. J., Li, S., Lamberson, K. A., & Matta, L. A. (2017). A Systematic Review of the mHealth Interventions to Prevent Alcohol and Substance Abuse. Journal of Health Communication, 22(5), 413-432. https://cloudfront.escholarship.org/dist/prd/content/qt95b527kt/qt95b527kt.pdf

Kelly, P. J., Kyngdon, F., Ingram, I., Deane, F. P., Baker, A. L., & Osborne, B. A. (2017). The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire‐8: Psychometric properties in a cross‐sectional survey of people attending residential substance abuse treatment. Drug and Alcohol Review.

Koukouvinos, C., & Simos, D. E. (2013). Encryption schemes based on hadamard matrices with circulant cores. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Bioinformatics, 3(1), 17-41. Retrieved from http://library.capella.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.library.capella.edu/docview/1425247993?accountid=27965

Lee, A., Moy, L., Kruck, S. E., & Rabang, J. (2014). The doctor is in, but is academia? re-tooling IT education for a new era in healthcare. Journal of Information Systems Education, 25(4), 275-281. Retrieved from http://library.capella.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fsearch.proquest.com%2Fdocview%2F1708018936%3Facc

Lenhart, A. (2012). Teens, Smartphones & Texting. Pew Research Center (Vol. i, pp. 1-34). Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Teens-and-smartphones.aspx

Mobile Device Management (MDM). (2012, November 22). Retrieved November 23, 2017, from https://www.gartner.com/it-glossary/mobile-device-management-mdm

Plotnikoff, R., Wilczynska, M., Cohen, K., Smith, J., & Lubans, D. (2017). Integrating smartphone technology, social support and the outdoor environment for health-related fitness among adults at risk/with T2D: The eCoFit RCT. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 20, e24. http://www.jsams.org/article/S1440-2440(16)30329-2/abstract

Rist, B., & Pearce, A. J. (2017). Improving Athlete Mental Training Engagement Using Smartphone Phone Technology. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 7(3), 138. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alan_Pearce/publication/314145515_Improving_Athlete_Mental_Training_Engagement_Using_Smartphone_Phone_Technology/links/59046b43a6fdccd580d06956/Improving-Athlete-Mental-Training-Engagement-Using-Smartphone-Phone-Technology.pdf

Safavi, S., & Shukur, Z. (2014). Conceptual privacy framework for health information on wearable device. PLoS One, 9(12), e114306. http://dx.doi.org.library.capella.edu/10.1371/journal.pone.0114306

Substance Abuse/Chemical Dependency. (n.d.). Retrieved November 23, 2017, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/healthlibrary/conditions/mental_health_disorders/substance_abusechemical_dependency_85,P00761

Tofighi, B., Nicholson, J. M., McNeely, J., Muench, F., & Lee, J. D. (2017). Mobile phone messaging for illicit drug and alcohol dependence: A systematic review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Review. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/dar.12535/full

Wilmer, H. H., Sherman, L. E., & Chein, J. M. (2017). Smartphones and Cognition: A review of research exploring the links between mobile technology habits and cognitive functioning. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5403814/

Williams, J. (2014). Left to their own devices: How healthcare organizations are tackling the BYOD trend. Biomedical Instrumentation & Technology, 48(5), 326-39. Retrieved from http://library.capella.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fsearch.proquest.com%2Fdocview%2F1566917763%3Faccountid%3D27965

Wilkes, J. J. (2014). The creation of HIPAA culture: Prioritizing privacy paranoia over patient care. Brigham Young University Law Review, 2014(5), 1213-1249. Retrieved from http://library.capella.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fsearch.proquest.com%2Fdocview%2F1716212527%3Faccountid%3D27965

What is data breach? – Definition from WhatIs.com. (n.d.). Retrieved November 23, 2017, from http://searchsecurity.techtarget.com/definition/data-breach

What is Joint Commission? – Definition from WhatIs.com. (n.d.). Retrieved November 23, 2017, from http://searchhealthit.techtarget.com/definition/The-Joint-Commissio

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Mobile Phones"

The first commercially available mobile phone was the Motorola DynaTAC 8000x, released in 1983. The high cost mainly restricted the first mobile phones to business until the early 1990’s when mass production brought cost effective consumer handsets. The launch of the first iPhone in 2007 introduced the world to the first phone that closely resembles what we know today.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation introduction and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: