The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulations: Impact on Saudi Arabia’s Economic Growth

Info: 9306 words (37 pages) Example Dissertation Proposal

Published: 19th Mar 2021

THE EUROPEAN UNION’s GENERAL DATA PROTECTION REGULATIONS: IMPACT ON SAUDI ARABIA’S ECONOMIC GROWTH

Abstract

The focus of this research proposal is to evaluate the impact of General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) on economic growth of Saudi Arabia, a member of the Gulf Cooperation Council(GCC) and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries(OPEC). GDPR is the European regulation on data protection and privacy for all residents living in Europe, replacing the existing European Union (EU) Directive (95/46/EC) (EUGDPR, n.d.). The EU Parliament approved GDPR on 14th April 2016, published on 24th May 2016 and applied on 25th May 2018. If organizations, whether in EU or non-EU, handle or work with associations that deal with personal information of people residing in EU, then the organizations will need to comply with GDPR and noncompliance may result in hefty fines. Compliance with GDPR requires additional investment, increasing the initial cost of the transaction, and may act as a non-tariff trade barrier. The timing of GDPR is crucial as Gulf countries like Saudi Arabia are now in the middle of diversifying its economy from the oil sector to boost investment and strengthen trade in critical non-oil services. The Saudi government passed several regulations to monitor electronic transactions and reduced cybercrime and working to formulate e-commerce law. Will the lack of a comprehensive data protection law block the expansion of digitization? Will compliance to GDPR add more burden on Saudi Arabia’s businesses and act as a trade barrier? Will GDPR enforces Saudi Arabia’s Government to define its data protection policies to minimize the compliance cost carried by each company individually? The proposal is to answer these questions by using mixed research, convergent parallel methodology.

Chapter 1: Introduction

During the last week of May 2018, many companies updated their privacy policies and notified consumers worldwide (Chen, 2018). This massive update on privacy policy event was in response to European regulation. On May 25, 2018, the EU Parliament enforced General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) into law that was approved two years ago on 14 April 2016. (EUGDPR). GDPR is the regulation on data protection and privacy for all residents living in Europe, replacing the existing EU Directive (95/46/EC) (EUGDPR). GDPR is designed to bring a shared understanding of data-protection laws among all EU members. The point of the GDPR is to shield all EU subjects from security and information breaches, in a data-driven world, that are different and unique about the time in which the previous EU directive was set up. Although the fundamental standards of data protection remain same, GDPR has added many changes to regulations and policies (EUGDPR, n.d.). These changes include updated consent, increased penalties, and enhanced cross-border scope (Goodard, 2017).

If organizations, whether in EU or non-EU, handle or work with associations that handle information of natural person residing in EU, then per GDPR these organizations are under obligation on how that information is dealt with, regardless of where the information is transferred, processed, or stored. Non-compliance to GDPR may result in a fine of up to €20 million, or 4% of the worldwide annual revenue of the prior fiscal year, shall be issued for infringements (Goodard, 2017).

GDPR, as a regulation, helps reduce the negative externalities in the digital market where a third party accrues costs because of some agreement of which he/she was not part. Cyberattack and data breach can have a significant impact on the individuals whose data are affected (Romanosky & Acquisti, 2012). Cyberattack is an attempt to damage, disrupt or gain unauthorized access to a computer. Data breach is a security incident in which private or confidential information is disclosed to unapproved entity intentionally or unintentionally. For example, in August 2017, a petrochemical plant in Saudi Arabia was a victim of cyberattack designed to destroy data or shut down the plant, creating a safety, financial and economic risk (Perlroth & Krauss, 2018). In the U.S, Facebook broke users’ trust by making over 50 million users’ data available to Cambridge Analytica, a UK research firm, which built a system targeting voters’ behavior without users’ consent influencing US elections and creating a political risk. (GDPRReport, 2018). In U.K., on June 13, 2018, Dixons Carphone, a British retailer who owns Curry’s, PC World, and more electrical brands in the UK and Europe, had a personal data breach that may impact 5.9 million customers (Dixons CarPhone, 2018). These incidents highlight circumstances where cyber attacks and data breaches, have placed people and the environment in physical harm, where people’s credit, financial, health information is stolen and where people’s political voice in a democratic society is manipulated.

Background of Study

Digitization is changing how businesses and consumers interact across global and political borders. A research study conducted by McKinsey indicates that the worldwide exchange of goods, investment, and information have accounted for a10% increase in the world’s GDP (2016). Data has become the core of the transaction resulting in the new idea of “Data the next big Oil.” In our modern computerized world, individual information is the fuel that drives much business movement on the internet (Schweighofer, Heussler, & Kieseberg, 2017).

Consumers provide businesses with their data in numerous situations such as using their credit cards when accessing medical care, or while interacting with companies and friends through social media (Bauer, Erixon, Krol, Lee-Makiyama, & Verschelde, 2013). However, many strategies for using information has raised concerns as of late concerning assurance and the security of data (2016). Consumers are often unaware of how much information is captured and used by firms.

The EU commission believes personal information protection is an individual’s primary right, and its goal is to protect its citizens. (Manu, 2015). The European institutions and EU member states believe in closer digital integration and creating a digital single market strategy (DSM). Digital integration is a basis for building up European guidelines and standard successfully, particularly in the global market (Bendiek, Berlich, Metzger, & Bendiek, 2015). Previous Data Protection Directive (DPD) was a directive and not a regulation. Different implementation and enforcement of DPDs by each member countries created a “…a strong risk of increasing fragmented approaches that would increase business cost, creating additional barriers for businesses to operate across borders and thus undermine the completion of a Digital Single Market…”(EU Commission, 2017).

GDPR, a legal framework, has six fundamental principles and eight rights, as shown below, as in contrast to eight principles in DPD.

| Principles | Rights |

| Lawfulness, fairness & transparency | Right to be informed |

| Purpose Limitation | Right of access |

| Data minimization | Right to rectification |

| Accuracy | Right to erasure |

| Storage limitation | Right to restrict processing |

| Integrity & Confidentiality | Right to data portability |

| Rights about automated decision making and profiling |

There are some key terms used in throughout DPD and GDPR that have special meanings. All of these key terms are defined in Article 4 of the GDPR. Some of these key terms are data subject, controller, processor, processing, personal data and, supervisory authority. A data subject is a natural person, living individual (not a corporation, dead or an animal). Any information that can identify data subject is personal data. A controller is an organization or legal body that determines the purpose and means of processing personal data. A processor is an organization or legal entity that processes personal data on behalf of a controller. A supervisory authority is a governmental organization in each member state of EU that is responsible for enforcement of GDPR (IT Governance, 2017).

Some of the critical differences between GDPR and previous Data Protection Directive, which makes GDPR, a strong privacy regulation are as follows:

| Key Areas in GDPR | Differences with DPD |

| Personal Data Definition (Extended) | The definition of Personal data is broad than defined in DPD and now includes IP address, mobile device identifiers, geo-location, biometric data, psychological identity, genetic identity, economic status, cultural identity, and social identity. |

| Data Subject Rights (Redefined and Added) | Controller to data subject must provide an explicit opt-in. Consent needs to be lawful, fair and transparent.

Data subject has a right to request information about the data given to the company by the data subject. Data subject has a limited right to be forgotten or erasure. If data subject related processing is done and is no longer needed then data subject has a right to ask the controller to remove his/her personal information Data subject has a limited right to data portability. Data subject has a right to ask for its data to move from one company to other in a machine-readable format |

| Data Controller vs. Data Processor- Accountability | In contrast to DPD, data processor is also accountable for the regulation of the processing of the information of data subjects.

Companies more than 250 employees must have a data protection officer (DPO) when the tasks of the controller or processor involve regular and systematic monitoring of data subjects on a large scale. |

| Information Governance and Security | |

| Data Breach notification, Complaints, and Penalties | Controllers must report to their supervisory authority within 72 hours of a breach; In case of higher risk breaches, the controller must notify data subjects.

Noncompliance with GDPR may result in fines up to 2-4% of global turnover or 20 million Euros, whichever is greater |

| Global Impact | The regulation applies to even controller or processor that are not in EU if they provide any market goods or services to EU residents |

Figure 1: The main differences between the DPD and the GDPR and how to address those moving forward. (2017, Feb). Retrieved from Britishlegalitforum: https://britishlegalitforum.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/GDPR-Whitepaper-British-Legal-Technology-Forum-2017-Sponsor.pdf

The balance between Privacy & Trade in EU: While concentrating on Privacy, the EU is looking to remove obstructions to the flow of information between organizations in future trade deals, as it attempts to push digital economy whereas protecting privacy (Fioretti, 2018). There are various contracts to conduct business or trade with EU countries under GDPR:

- Model Contracts: Model Contractual Clauses (or called as standard contract clauses) are pre-approved contractual clauses simplify data transfer agreements between countries and processors located outside the EU.

- Binding Corporate Rules: Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs), another form of a contractual clause, allows organizations to transfer data within their sister organization or group

- Adequacy Clause: Under previous EU Data Protection Directive (1995) Article 25, Section 6 states that the European Commission has an authority to evaluate whether a country utilizes “adequate” privacy protections. The EU recognizes a third country’s privacy framework to be adequate, and currently, only 12 countries have given the stamp to transfer the data freely. Saudi Arabia is not one of them.

Current EU- Saudi Trade position and Vision: Today, the trade balance is positive for EU-Arab Countries, and the trade between EU and Arab countries conducts trade within the framework of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). GCC countries are Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (Yusuf, 2017).

Figure 2: Dana Asaad, Ibrahim Al Mana, Noora Al Kuwari, Hamad Jaber, “Map of the GCC,” Borders, accessed June 21, 2018, https://apps.cndls.georgetown.edu/projects/borders/items/sho

Per 1988 cooperation agreement between EU and GCC Countries, GCC framework was put in place to improve trade relations and stability (EU GCC Corporation Agreement, 2008). In an interview in April of 2018, with Saudi Gazette reporter, Ewa Synoweic, Chief advisor to the European Commission, stated that the EU became the largest trading partner of GCC, with two-way trade exceeding 143 billion Euros (Synoweic, 2018).

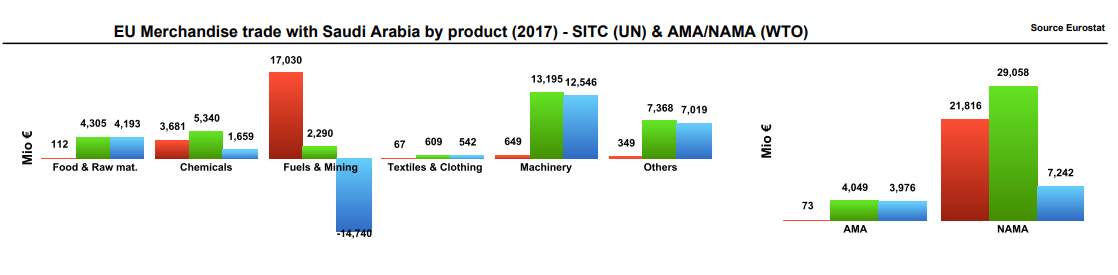

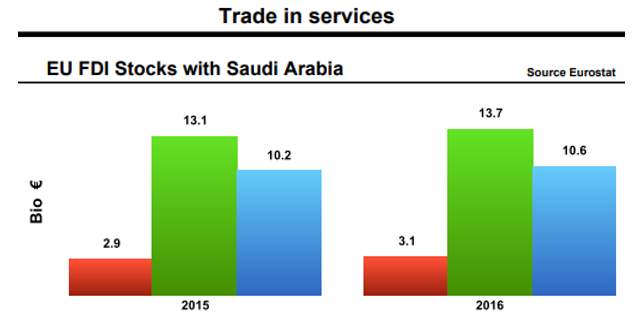

With 15% share in an EU market, Saudi Arabia is the EU’s 15th trading partner in goods and services (Gulf region – Trade – European Commission, 2018). Under the Vision 2030 plan, Saudi Arabia would like to increase its global competitiveness rank from 25th to the top 10 and increase private sector contribution to the GDP from 40% to 65%. It would also like to go from the 19th largest economy in the world to one of the top 15th largest economies of the world increase the non-oil exports from 16 to 50% of non-oil GDP, and go up in the logistic performance index from 49th to 25t (Thompson, 2017). The following figure shows EU export and import trend between Saudi Arabia and EU in goods and services in the last thee years.

As per another source, the following graph (Sabbati, 2017) indicates that services industry is moving up but slowly.

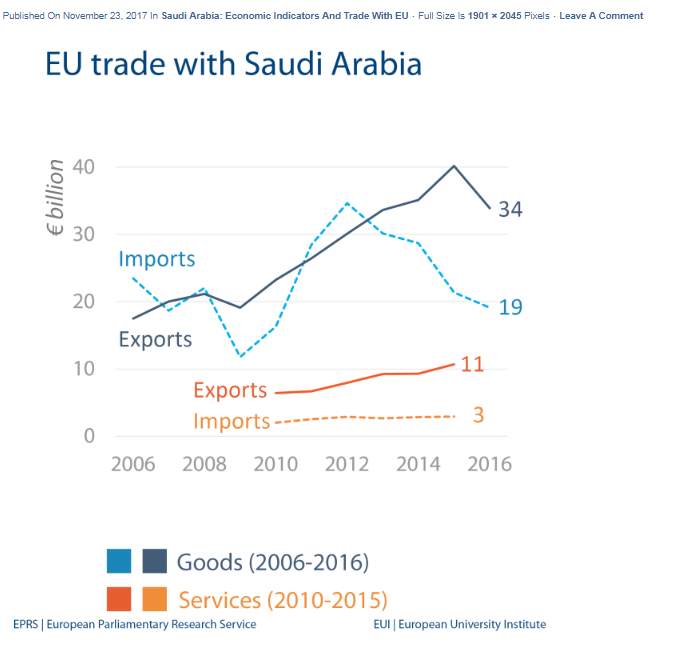

To diversify the economy from the oil sector, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries are focusing on digitization by enhancing Information Technology Infrastructure, compliance and training unskilled workers. Per report from World Economic forum (Elmasry, Benni, Patel, & Moore, 2016) there is a strong correlation between digitization and non-oil GDP.

Figure 3: Source: Networked Readiness Index 2015, World Economic Forum; 2016 Digital yearbook, We Are Social; Digital Adoption Index 2016; World Development Indicators, World Bank; Wild Market Monitor, September 2016; World Industry Service Database, July/September 2016; Euromonitor Passport, September 2016; Megna Strategy Analysis; Analyys Mason;UN E-Government Survey 2016; ITU; McKinsey analysis

While digitization is essential and useful for economy, latest survey by Ernst & young Global Forensic Data Analysis survey found that 60% of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and United Arab Emirates (UAE) respondents are aware, and concern about data protection and privacy compliance, and 82% do not have a strategy in place to comply with EU legislation (Saudi Gazzette, 2018). These companies are working under Saudi Arabia privacy laws that may not be fully compliant with GDPR.

Current Privacy Laws in Saudi Arabia:

There is no omnibus data protection law in Saudi Arabia unlike EU (Bowman, 2016). Instead, the country’s constitution (the Basic Law of Governance) and various sectoral laws together make Saudi privacy law. In addition to these two laws, Saudi has a Sharia, “Islamic law,” and it provides a comprehensive code for living one’s life in compliance with Islamic dictate (Bowman, 2016). Generally, in the absence of applicable legislation, Saudi judges apply Sharia in adjudicating claims. While the Saudi government has passed several regulations to monitor electronic transactions and reduced cybercrime and working to formulate e-commerce law, the lack of a comprehensive data protection law could be a blocker to the expansion of online trading. In Saudi Arabia, Advisory “Shura’ Council is currently reviewing new freedom of information and protection of private data law (Law in Saudi Arabia, 2017). There are significant gaps between Saudi Laws and GDPR.

| Saudi Laws | GDPR | ||

| Personal Data | “Personal Data” as such is not defined. Instead, laws referred to Personal information that includes: name; email address; and personal identifiers such as education, employment, family and financial details | The definition of personal data includes additional fields like IP address, biometric, race, ethnicity, genomic data, etc. | |

| Data Subject | “Data Subject” is not defined. However Saudi laws are to protect Saudi citizens | “Data Subject” is a natural person, living in EU, whether EU citizen or not | |

| Data Controller or Processor | “Data Controllers” and “Data Processors” are not defined. There is no standard notification or registration requirements needed before processing of data. | “Data Controllers” and “Data Processors” have a required contract in place. | |

| Data Protection Authority or Supervisory authority | There is no concept of national data protection regulator in Saudi Arabia. | Companies more than 250 employees must have a data protection officer (DPO) when the tasks of the controller or processor involve regular and systematic monitoring of data subjects on a large scale.

Every EU member country has one or more supervisory authority to enforce regulations |

|

| Consent | In case of credit arrangement, lawfulness to collect the data exist.

Information technology sector must get employees’ consent before releasing personal data to third parties (Ministers Resolution no. 163 dated 24/10/1417H). Under Article 23(2), Electronics Transactions Law, it is unlawful to process an applicant’s information without his or her consent. There is no mention of implied or inferred consent by minors (people under 18 years of age) in Saudi legislations. However, there is no standard language for the content of the consent, and this law does not apply to employers’ access to employees’ work-related emails. An employer can access an employee’s work-related e-mails or database without permission. |

“Consent” need to be lawful, fair and legitimate.

Child consent requires special consideration. Only parental authorized, verified, can provide child consent if the child is under 16 years old. There is no default opt-in. Consent needs to be clear as consent to withdraw. |

|

| Right to erasure and data portability | There are no laws for “right to be forgotten” or erasure and “data portability” for data subjects. | Introduction of two rights “Right to be forgotten” and “Right to Data Portability” is added in GDPR. | |

| Notification of Breach | In case of data security breach, companies do not need to notify any individual or entity in Saudi Arabia | Companies whether controller or processor need to inform every violation to the supervisory authority under 72 hours | |

| Cross-border transfer | There are some regulations in the financial sector where it is mandatory to get the approval of relevant regulatory authority like Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA). SAMA prohibits the cross-border transfer of data processing of any banking information that initiates in Saudi Arabia. There are no standard contracts for data exchange among associations. | Standard Contract Clause, Binding Corporate Clause, Adequacy framework are three ways where cross-border data transfer can happen. |

Table 2Law in Saudi Arabia. (2017, Jan 26). Retrieved from DLA PIPER DATA PROTECTION LAWS OF THE WORLD: https://www.dlapiperdataprotection.com/index.html?t=law&c=SA

The Ministry of Commerce and Investment began to formulate a draft e-commerce law in 2014, and presently, it is still under review by the Saudi government (2018). Will the EU-Saudi Arabia trade decline in the absence of data protection laws? If so, how much? This study will address these questions.

The Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this research proposal is to assess a variety of critical political and economic indicators to help evaluate the impact of GDPR on Saudi Arabia’s economic growth. The scope is limited to digital services sector where companies trade with EU member countries in exchange for goods and services and have limited privacy laws.

Research Questions

What is the quantitative and qualitative impact of GDPR on the growing sectors as called out in the Saudi Vision 2030 (tourism, healthcare, logistics, telecommunication, and critical IT services such as data centers) in Saudi Arabia? If the impact is significant, how will it affect their Vision 2030 implementation to diversify cross-border trade in the non-oil sectors? Does GDPR bring an opportunity for Saudi Arabia Policymakers to create data protection regulations to reduce the non-compliance and help expedite the implementation of Vision 2030?

The Significance of the Study

This study can help companies, big or small, government officials, and policymakers in the following ways:

- ‘C’ level officers (Chief financial officer, Chief Governance and Risk Compliance Officer and Chief Cyber Security Officers) at multinational companies in Saudi Arabia can understand the need and prepare for complying with GDPR.

- Tourism, Logistics, Healthcare, and Information & Communication Technologies (ICT) services sectors can understand the importance of complying with being in non-compliance, assess the likelihood and severity of the future breaches and act accordingly.

- The ministries of Commerce, Transportation, and Health can understand the impact of GDPR on the overall economy and perhaps may make a case for creating a data protection framework at a national level.

Literature Search Procedures

The literature search focused on articles describing the definition, interpretation and the need for GDPR to replace European Directive. Reviewed materials representing the GDP contribution of current cross-border trade between Saudi Arabia and Europe in the non-oil services sector. Most data and reports use information from World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), European Commission reports, scholarly articles, and other privately funded reports. The analysis covers studies published in English. Search terms include various combinations of the keywords such as “regulations,” “Economic Growth,” “the impact of regulation of the economy,” “service sector,” “the contribution of the service sector in GDP,” “the effect of non-tariff barrier on economic growth.” Reviewed data protection related legal cases in Europe.

Conceptual Framework

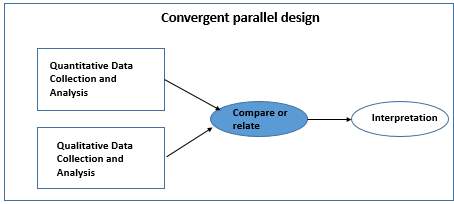

This study, based on convergent parallel mixed methodology, is divided into three phases as depicted below (Creswell, 2014).

Figure 4The three phases of the present study using the “convergent parallel” design

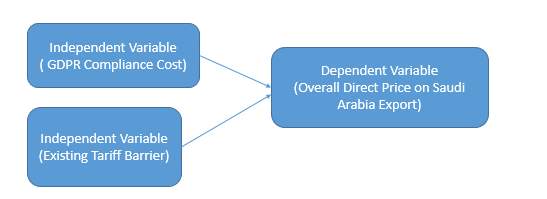

The Quantitative stage analyzes the potential cause and effect of the EU’s proposed General Data Privacy Regulation (GDPR) on services sector trade. In this exercise, GDPR compliance cost is an additional non-tariff barrier impacting overall direct price on data export.

Figure 5 Quantitative phase: Direct Price Increase based on Compliance Cost

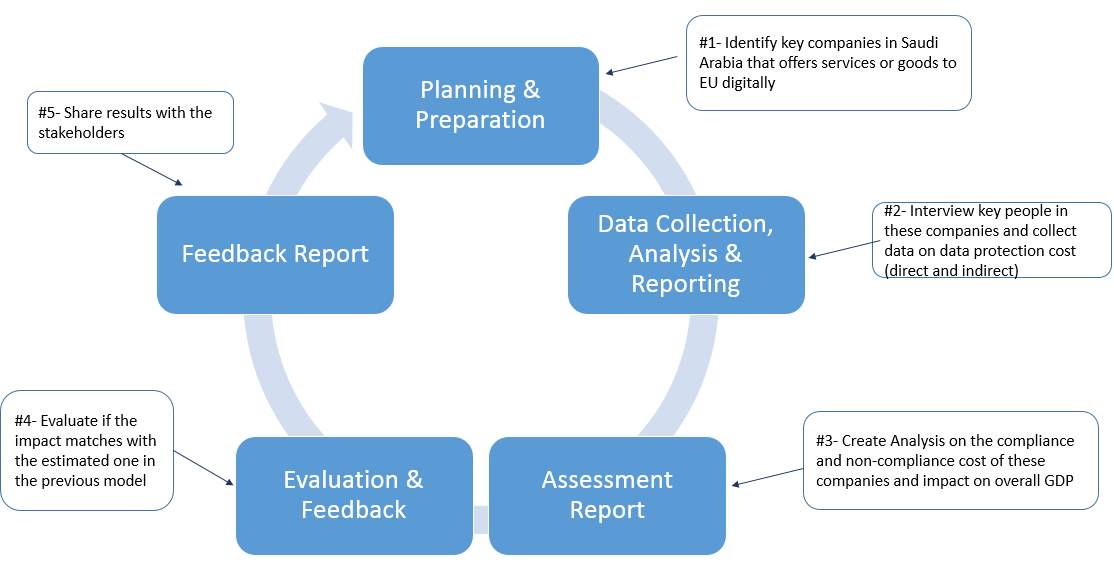

The Qualitative stage, shown below, describes a process of conducting semi-structured interviews with the multinational companies located in Saudi Arabia. These companies are involved in digital trade with EU in the services sectors, particularly transportation, tourism, finance, communication (information technology) and healthcare.

Figure 6: Qualitative phase of conducting semi-structured interview

Review of Related Literature

Scholars, lawyers, and economists have written about the impact of regulations on economic growth from a legal perspective. Some scholars are have written about the economics of privacy whether they are old or related to other geographies and not for Saudi Arabia. However, existing reports provides insights, applicability, and methodologies to a study related to Saudi Arabia.

There are different opinions about economies of privacy and how it impacts the companies and economic growth. Chicago school of law scholars Posner (The Economics of Privacy, 1981) and Stigler (1980) states that limiting privacy drives inefficiencies in the market. Additionally, Calzoria and Pavan (2006) argued that unrestricted sharing of data across borders, in fact, reduces market distortion. Posner, Stigler, Calzoria, and Pavan are right as long as the unlimited privacy drives positive externality. In cases of a negative externality, such as in the case of Facebook and Cambridge Data Analytica, not restricting privacy regulations can create far more economical and political risk than the benefits (GDPRReport, 2018).

Another study at The London School of Economics, a for-profit-organization, revealed that restricting consent may likely to damage productivity benefits. A strict interpretation of the GDPR consent could cause a loss of UK GDP of up to £14 billion, due to additional hurdles to direct marketing only. For the EU, GDP losses could be as significant as £58 billion, with 1.3 million jobs lost. A loss to the UK GDP, due to additional hurdles to online behavioral advertising, could be up to £633 million (£3 billion and 66,000 jobs lost EU-wide) (2017). The services sector is still growing in Saudi Arabia, and to my knowledge, the cost of restricting privacy is still unknown in the Saudi market.

Varian (1996) claimed that consumers might suffer privacy costs when transaction uses too little personal information. Varian states that ” …The consumer, Varian notes, may rationally want certain information about herself known to other parties: for instance, a consumer may want her vacation preferences to be known by telemarketers, to receive from them offers and deals she may be interested in…”. A London school of economics research study found that consumers are willing to forego savings of roughly 5% to 10% on weekly spending (2017). Consumers may be willing to pay extra off. However, the quantification of the implications of this additional cost on the business is still unknown, especially in Saudi Arabia.

With privacy, negative externalities are the cause of large information asymmetries existing between companies and consumers. (Sholtz, 2001). Coase Theorem states that trade in an externality (e.g., data breach cost) is possible, as long as the transaction costs for both parties are low (Halteman, 2005). The low transaction cost can vary from business to business and country to country, and the different low transaction cost is unknown now.

Alessandro Acquisti (Acquisti, Taylor, & Wagman, 2016) used the cost-benefit approach to examine the economics of personal data and the economics of privacy by looking at the cost and benefits to stakeholders involved in the trade. Acquisti’ conclusion is similar to Article 24 in GDPR “.Taking into account the nature, scope, context, and purposes of processing as well as the risks of different likelihood and severity for the rights and freedoms of natural persons, the controller shall implement appropriate technical and organizational measures to ensure and to be able to demonstrate that this regulation performs processing. These measures shall be reviewed and updated where necessary…” (EUGDPR, n.d.). The government of United Kingdom has done impact assessment using cost-benefit analysis. There is no privacy impact assessment done at Saudi Level to understand the cost-benefit analysis.

Francois (Francois, 2013) used regulations as a non-tariff barrier to show the impact of reducing the transatlantic barrier to trade and investment between the UK and the US. Matthias, Fredrik, Michal, Hosuk and Bert’s study used Francois’s basis of treating GDPR as a non-tariff barrier, as well as the Global Trade Analysis Project 8 (GTAP 8) database to show that EU GDP shrinks as the degree of trade disruptions increase (2013). Significant political, economic, and financial differences exist between the US and Saudi Arabia. Therefore, the inference from Matthias et al. ’s research cannot be applied automatically to the EU-Saudi Arabia relationship. However, this study is the most relevant study to helping us in finding the similar relationship between Saudi Arabia and EU quantitatively.

Crozet Milet and Mirza’s (2016) research showed that domestic regulation has a significant adverse impact on both the decision to export and the values transported by each firm during international trade. Crozet et al. conducted a quantification exercise and used a Non-Manufacturing index (NMR) developed by OECD as a proxy for the domestic regulations in the French firm-level market on the exports of professional services. This exercise indicates that the French firms are less likely to export to highly regulated markets. GDPR, in contrast, puts a burden of compliance on non-EU countries, which may increase the actual cost of doing business with EU.

The tourism sector, generating approximately US$ 13.8 billion annually, is the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s second largest source of income after oil and is the third largest source of employment (Khan, Alam, & Han, 2014). Revenue from international travel and tourism to Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is expected to reach US$ 63.7 billion by 2019 (Khan, Alam, & Han, 2014). One international study indicated that hotels think they are GDPR compliant, but the reality is that there are no universal compliance standards in the hotel industry (NewsRX LLC, 2018). Race and ethnic origin are the now personal data as per GDPR, and travel companies will be liable for complying with GDPR. Information about health issues during travel is also personal and sensitive data. In the Tourism sector, only 33.10% companies are compliant (DLAPiper, 2018). The impact of GDPR on Saudi tourism sector is still unknown.

Per the Minister of Transport in Saudi Arabia, non-oil GDP will increase by 5% in 2021 (Ministry of Transport – Saudi Arabia, 2017). Moreover, the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) says 50% of transportation companies will need a data protection officer (DPO) due to the data-intensive nature of their operations. DPO is a new role that companies will need to invest money in. As per GDPR, DPO reports to the board of the directors, who will monitor compliance, manage data protection activities and assessments, provide staff training and audits, and interact with the authorities. The GDPR requires that the DPO have “expert knowledge of data protection law and practices” (IAPP, 2017). GDPR forces companies to evaluate the likelihood and the severity of the risk caused by data protection and privacy issues to reduce the risk.

Saudi Arabia faces the highest number of cyber-attacks in the Arab region, per the Kaspersky cyberthreat real-time map, with the number of threats rising by 7% quarter on the quarter (2018). The average cost incurred for each lost or stolen record containing sensitive and confidential information increased 6 % from a consolidated average of $145 to $154 (2015). A recent study conducted among 13 countries, including Saudi Arabia, found that on average the cost of a data breach is $158 per data record (Cost of data breach reaches record levels, 2015)

A study in 2017 found that only 2 percent of “GDPR-ready” organizations are compliant (Software World, 2017). DLA Piper, a for-profit multinational law firm located in more than 40 countries, conducted another study on GDPR preparedness. After examining 200 organizations worldwide, DLA Piper found only 34.4% to have some data protection processes in place, and many still have gaps in more than one area (DLAPiper, 2018). ; .

Another study from Ponemon Institute and Globalscape, for-profit organizations, indicates that the cost of compliance may vary from $7.7 to $30.9 million. As per their report, the cost of non-compliance is 2.71 times the cost of compliance and the average price for organizations that experience non-compliance problem is $14.82 million, a 45percent increase from 2011 (Ponemon Institute LLC and Globalscape, 2017).

Conclusion:

References

(n.d.).

Ng, W. Y., & Ko, J. (2017, May 24). The Geopolitics of Data Transfer: What Do Companies Need to Consider in a Post-Trump, Brexit and GDPR World? – Global Investigations Review – GIR. Retrieved from https://globalinvestigationsreview.com: https://globalinvestigationsreview.com/insight/the-european-middle-eastern-and-african-investigations-review-2017/1142001/the-geopolitics-of-data-transfer-what-do-companies-need-to-consider-in-a-post-trump-brexit-and-gdpr-world

Acquisti, A., Taylor, C., & Wagman, L. (2016). The economics of privacy. Journal of Economic Literature, 54(2), 442-492. doi:10.1257/jel.54.2.442

Analysis of the potential economic impact of GDPR. (2017, October). Retrieved from londoneconomics.co.uk: https://londoneconomics.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Analysis-of-the-potential-economic-impact-of-GDPR-FINAL-October-2017.pdf

Bauer, M., Erixon, F., Krol, M., Lee-Makiyama, H., & Verschelde, B. (2013). The Economic Importance Of Getting Data Protection Right: Protecting Privacy, Transmitting Data, Moving Commerce. Belgium: European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE). Retrieved from https://www.uschamber.com/sites/default/files/legacy/reports/020508_EconomicImpo

Bendiek, A., Berlich, C., Metzger, T., & Bendiek, A. (. (2015). The European Union’s Digital Assertiveness. Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik.

Bowman, M. C. (2016, November). Privacy Law In Saudi Arabia: A Primer For Businesses. Mondaq Business Briefing. Mondaq.

Calzolari, G., & Pavan, A. (2006). On the optimality of privacy in sequntial contracting. Journal of Economic Theory, 130(1), 168-204. doi:10.1016/j.jet.2005.04.007

Chen, B. (2018, May 23). Getting a Flood of G.D.P.R.-Related Privacy Policy Updates? Read Them. Retrieved from nytimes.com: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/23/technology/personaltech/what-you-should-look-for-europe-data-law.html

Companies Law. (n.d.). Retrieved from Boe.gov.sa.

Cost of data breach reaches record levels. (2015, May 29). Enterprise Innovation.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design : qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks : SAGE Publications.

Crozet, M., Milet, E., & Mirza, D. (2016, August). The impact of domestic regulations on international trade in services: Evidence from firm-level data. Journal of Comparative Economics, 44(3), 585-607. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2015.11.004

Curtiss, T. (2016). Privacy harmonization and the developing world: The impact of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation on Developing Economies. Washington Journal of Law, Technology & Arts, 12, 95. Retrieved from http://digital.law.washington.edu/dspace-law/handle/1773.1/1654

Data Protection regulations and international data flows. (2016, April). Retrieved from UNCTAD.org: http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/dtlstict2016d1_summary_en.pdf

Determann, L. (2017). Determann’s field guide to data privacy law : international corporate compliance, third edition. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Pub.

Digital Globalization: The New Era of Global Flows. (2016, March). Retrieved from www.mckinsey.com/mgi: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Business%20Functions/McKinsey%20Digital/Our%20Insights/Digital%20globalization%20The%20new%20era%20of%20global%20flows/MGI-Digital-globalization-Full-report.ashx

Dixons CarPhone. (2018, June 13). Investigation Into Unauthorised Data Access. Retrieved from dixonscarphone.com: http://www.dixonscarphone.com/~/media/Files/D/Dixons-Carphone/documents/pr-investigation-into-unauthorised-data-access.pdf

DLAPiper. (2018). 2017 Privacy Snapshot report. DLA Piper. Retrieved from https://www.dlapiper.com/en/europe/insights/publications/2018/01/global-data-privacy-snapshot-2018/

Elmasry, T., Benni, E., Patel, J., & Moore, J. a. (2016). Digital Middle East: Transforming the region into a digital economy. Dubai: McKinsey.

EU. (2016). Access to European Law. Retrieved from EUR-Lex: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016R0679

EU GCC Corporation Agreement. (2008, September). Retrieved from http://trade.ec.europa.eu: http://trade.ec.europa.eu

EUGDPR. (n.d.). Retrieved from Key Changes with the General Data Protection: http://www.eugdpr.org/key-changes.html

Fefer, R. F., Akhtar, S. I., & Morrison, W. M. (2018, May 11). Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy. Retrieved from www.crs.gov: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44565.pdf

Fioretti, J. (2018, Feb 9). EU moves to remove barriers to data flows in trade deals. Retrieved from www.reuters.com: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-data-trade/eu-moves-to-remove-barriers-to-data-flows-in-trade-deals-idUSKBN1FT2DC

Francois, J. (2013). Reducing Transatlantic Barriers to Trade and Invstment. London: Center for Economic Policy Research.

GDPRReport. (2018). Legal Expert Predicts Facebook Data Breach Could Lead to Increased Enforcement of GDPR. M2 Presswire.

Godel, Moritz; Landzaat, Wouter; Suter, James. (2017). Research and analysis to quantify the benefits from personal data rights under the GDPR. London: London School of Economics. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/635701/PersonalDataRights_LE_-_for_Data_Protection_Bill__1_.pdf

Goodard, M. (2017). The EU General Data Protection Regulation: European regulation that has a global impact.(Viepwoint). International Journal of Market Research, Vol.59(6). doi:0.2501/IJMR-2017-050

Gulf region – Trade – European Commission. (2018). Retrieved from Ec.europa.eu: http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/regions/gulf-region/

Halteman, J. (2005). Externalities and the Coase Theorem: A Diagrammatic Presentation. Journal of Economic Education.

IAPP. (2017). The GDPR Demands 75K DPOs. International Association of Privacy Professionals. Retrieved from https://iapp.org/media/pdf/DPA-Whitepaper.pdf

IT Governance. (2017). EU General data protection regulation (GDPR) : an implementation and compliance guide. (P. Team, Ed.) Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom: Ely : IT Governance Publishing.

Khan, S., Alam, S., & Han, W. (2014, December). ‘Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A potential destination for medical tourism. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 9(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2014.01.007

Lambert, P. (2018). Understanding the new European data protection rules. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

Law in Saudi Arabia. (2017, Jan 26). Retrieved from DLA PIPER DATA PROTECTION LAWS OF THE WORLD: https://www.dlapiperdataprotection.com/index.html?t=law&c=SA

Laybats, C., & Davies, J. (2018). GDPR: Implementing the regulations. Business Information Review, 35(2), pp. 81-83.

Manu, S. J. (2015). THE EUROPEAN UNION’s GENERAL DATA PROTECTIOn REGULATION: HOW WILL IT AFFECT NON-EU ENTERPRISES. Syracuse Science & Technology Law Reporter, 31(1555-4996), 216-251.

Michael, M. G., & Michael, K. (2014). Uberveillance and the social implications of microchip implants : emerging technologies. Hershey, PA, USA: Information Science Reference. Retrieved from https://www.worldcat.org/title/uberveillance-and-the-social-implications-of-microchip-implants-emerging-technologies/oclc/843857020

Ministry of Transport – Saudi Arabia. (2017, April). Ministry News. Retrieved from Ministry of Transport Saudi Arabia: https://mot.gov.sa/en-us/MediaCenter/News/Pages/news841.aspx

Nermeen Abbas, Forbes Middle East Staff. (2018, March 28). Arab Countries Facing The Highest Number Of Cyber Attacks. Retrieved from www.forbesmiddleeast.com: https://www.forbesmiddleeast.com/en/arab-countries-facing-the-highest-number-of-cyber-attacks/

NewsRX LLC. (2018, June 4). Hotels Think They Are GDPR Compliant, But The Truth Is There Are No Universal Compliance Standards. Jorunal of Engineering, 607.

Nurunnabi, M. (2017). Transformation from an Oil-based Economy to a Knowledge-based Economy in Saudi Arabia: the Direction of Saudi Vision 2030. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 8(2), 536(29). doi:10.1007/s13132-017-0479-8

Perlroth, N., & Krauss, C. (2018, March 25). A Cyberattack in Saudi Arabia Had a Deadly Goal. Experts Fear Another Try. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/15/technology/saudi-arabia-hacks-cyberattacks.html

Ponemon Institute LLC and Globalscape. (2017). The True Cost of Compliance with Data Protection Regulations. San Antonio: Globalscape. Retrieved from https://www.globalscape.com/resources/whitepapers/data-protection-regulations-study

Posner, R. A. (1981). The Economics of Privacy. The American Economic Review, 405-409.

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council. (2017, 10 1). Retrieved from EUR-LEX Access tro European Union Law: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A52017SC0003

Sabbati, G. (2017, November 23). Saudi Arabia: Economic indicators and trade with EU. Retrieved from European Parliamentary Research Service Blog: https://epthinktank.eu/2017/11/23/saudi-arabia-economic-indicators-and-trade-with-eu/

(2018). Saudi Arabia’s e-commerce market set to take-off. Oxford Business Group. Retrieved from Oxford Business Group: https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/analysis/expansion-horizon-favourable-forecast-kingdom%E2%80%99s-e-commerce-market

Saudi Gazzette. (2018, Feb). Companies in KSA, UAE ‘increasingly concerned’ about data protection: EY. Retrieved from saudigazette.com.sa: http://saudigazette.com.sa/article/528760/BUSINESS/Companies-in-KSA-UAE-increasingly-concerned-about-data-protection-EY

Schweighofer, E., Heussler, V., & Kieseberg, P. (2017, October 11). Privacy by Design Data Exchange Between CSIRTs (Vol. 10518). Springer, Cham. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67280-9_6

Sholtz, P. (2001, May 7). Transaction Costs and the Social Costs of Online Privacy. First Monday, 6(5).

Software World. (2017). Organisations worldwide mistakenly believe they are GDPR compliant: only Two Percent of “GDPR-ready” Organisations Are Compliant.(GDPR STUDY). 48(4), p. 15(3).

Stigler, G. J. (1980). An Introduction to Privacy in Economics and Politics. The Journal of Legal Studies, 9(4), 623-644. doi:10.1086/467657

Synoweic, E. (2018, April). EU becomes largest trading partner of GCC with two-way trade exceeding €143 billion. (S. Gazzette, Interviewer) Retrieved from http://saudigazette.com.sa/article/532289/BUSINESS/EU-becomes-largest-trading-partner-of-GCC-with-two-way-trade-exceeding-euro143-billion

The main differences between DPD and the GDPR. (2017, 02). Retrieved from BritishLegalItForum: https://britishlegalitforum.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/GDPR-Whitepaper-British-Legal-Technology-Forum-2017-Sponsor.pdf

The main differences between the DPD and the GDPR and how to address those moving forward. (2017, Feb). Retrieved from Britishlegalitforum: https://britishlegalitforum.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/GDPR-Whitepaper-British-Legal-Technology-Forum-2017-Sponsor.pdf

Thompson, M. C. (2017). SAUDI VISION 2030: A VIABLE RESPONSE TO YOUTH ASPIRATIONS AND CONCERNS? Asian Affairs(2), 205-221. doi:10.1080/03068374.2017.1313598

UNCTAD Summary of Adoption of E-Commerce Legislation Worldwide. (n.d.). Retrieved from Unctad.org: http://unctad.org/en/Pages/DTL/STI_and_ICTs/ICT4D-Legislation/eCom-Global-Legislation.aspx

Varian, H. R. (1996). Economic Aspects of Personal Privacy. Berkely: University of California.

Yusuf, Y. K. (2017). The Gulf Cooperation Council states : hereditary succession, oil and foreign powers. London: Saqi Books.

| Fair, lawful and transparent processing

The requirement to process personal data fairly and lawfully is extensive. It includes, for example, an obligation to tell data subjects what their personal data will be used for. |

Rec.38, Art.6(1)(a)

Personal data must be processed fairly and lawfully. |

Rec.39; Art.5(1)(a)

Personal data must be processed lawfully, fairly and in a transparent manner in relation to the data subject. |

This change imposes an additional compliance burden on organisations (albeit one that is implied under the Directive). It requires that organisations take additional care when designing and implementing data processing activities. |

| The purpose limitation principle

In summary, the purpose limitation principle states that personal data collected for one purpose should not be used for a new, incompatible, purpose. |

Rec.28; Art.6(1)(b)

Personal data may only be collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and must not be further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes. (Further processing of data for historical, statistical or scientific purposes is permitted, provided that Member States provide appropriate safeguards.) |

Rec.50; Art.5(1)(b)

Personal data may only be collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and must not be further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes. (Further processing of personal data for archiving purposes in the public interest, or scientific and historical research purposes or statistical purposes, in accordance with Art.89(1), is permitted—see Chapter 17). |

The GDPR brings limited changes to the principle of purpose limitation. Further processing of personal data for archiving, scientific, historical or statistical purposes is still permitted, but is subject to the additional safeguards provided in Art.89 of the GDPR. |

| Data minimization

The principle of data minimisation is essentially the idea that, subject to limited exceptions, an organisation should only process the personal data that it actually needs to process in order to achieve its processing purposes. |

Rec.28; Art.6(1)(c)

Personal data must be adequate, relevant and not excessive in relation to the purposes for which those data are collected and/or further processed. |

Rec.39; Art.5(1)(c)

Personal data must be adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which those data are processed. |

The obligation to ensure that personal data are not excessive is replaced by a more restrictive obligation to ensure that personal data are “limited to what is necessary”. Organisations will need to carefully review their data processing operations to consider whether they process any personal data that are not strictly necessary in relation to the relevant purposes |

| Accuracy

There are obvious risks to data subjects if inaccurate data are processed. Therefore controllers are responsible for taking all reasonable steps to ensure that personal data are accurate. |

Art.6(1)(d)

Personal data must be kept in a form that permits identification of data subjects for no longer than is necessary for the purposes for which the data were collected or for which they are further processed. Member States are obliged to implement appropriate safeguards for personal data stored for longer periods for historical, statistical or scientific use. |

Rec.39; Art.5(1)(e)

Personal data must be kept in a form that permits identification of data subjects for no longer than is necessary for the purposes for which the personal data are processed. Personal data may be stored for longer periods insofar as the data will be processed solely for archiving purposes in the public interest, or scientific, historical, or statistical purposes in accordance with Art.89(1) and subject to the implementation of appropriate safeguards. |

The principle is unchanged, but the GDPR introduces two important new factors:

There are specific provisions on the processing of personal data for historical, statistical or scientific purposes (see Chapter 17). The principle should be read in light of the “right to be forgotten” (see Chapter 9) under which data subjects have the right to erasure of personal data, in some cases sooner than the end of the maximum retention period. |

| Data security

Controllers are responsible for ensuring that personal data are kept secure, both against external threats (e.g., malicious hackers) and internal threats (e.g., poorly trained employees). |

Rec.46; Art.17(1)

The controller must implement appropriate technical and organisational measures to protect personal data against accidental or unlawful destruction or accidental loss, alteration, unauthorised disclosure or access. |

Rec.29, 71, 156; Art.5(1)(f), 24(1), 25(1)-(2), 28, 39, 32

Personal data must be processed in a manner that ensures appropriate security of those data, including protection against unauthorised or unlawful processing and against accidental loss, destruction or damage, using appropriate technical or organisational measures. |

The GDPR moves this obligation into the Data Protection Principles, reinforcing the idea that data security is a fundamental obligation of all controllers. However, the principle itself is essentially unchanged. |

| Accountability

The principle of accountability seeks to guarantee the enforcement of the Data Protection Principles. This principle goes hand-in-hand with the growing powers of DPAs. |

Art.6(2)

The controller must ensure compliance with the Data Protection Principles. |

Rec.85; Art.5(2)

The controller is responsible for, and must be able to demonstrate, compliance with the Data Protection Principles. |

Under the GDPR, the controller is obliged to demonstrate that its processing activities are compliant with the Data Protection Principles. This obligation is expanded upon in Chapter 10, which sets out the obligations of controllers. |

https://www.whitecase.com/publications/article/chapter-6-data-protection-principles-unlocking-eu-general-data-protection

We hope this example dissertation proposal has helped you with your studies. See our guide on How to Write a Dissertation Proposal for guidance on writing your own proposal.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Data Protection"

Data Protection refers to the privacy and security provided to data that is collected and stored by businesses. Data related to both customers and employees is protected from being misused by others as part of scams or fraud.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation proposal and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: