Psychology Undergraduate Attitudes Towards Male Sex Offenders: The Impact of the Victim’s Gender

Info: 13008 words (52 pages) Dissertation

Published: 28th Feb 2022

Tagged: CriminologyPsychology

Abstract

There is a general aspiration for the treatment outcomes of both the sex offender and his/her victim to be fruitful. The relevance of attitudes in this context has been widely studied and there is a substantial body of empirical research pointing towards the importance of attitudes within the treatment and rehabilitation of the sex offender. Still, research that investigates the relevance of attitudes for the successful treatment outcome of the sexual assault victims is scarce. Nonetheless, this study attempts at investigating this gap in literature by measuring the attitudes of students (soon-to-be professionals) towards sex offenders in relation to an important characteristic of the victim, gender. One hundred and twenty-four participants fulfilled two measures of attitudes (PSO and ATS-21) in order to test the hypothesis and to answer the research question. Overall, the sex offenders’ perceived intentions were considered more negative when the victim was a female. No other statistically significant results were found, however on multiple subscales, the attitudes appeared somewhat more negative when the victim of the sexual offences was a female. Findings, limitations and implications are discussed.

Table of Contents

Click to expand Table of Contents

List of abbreviations

Introduction

Literature Review

Method

Design

Participants

Materials

Case vignettes

‘Perceptions towards Sex Offenders’ (PSO) scale

‘Attitudes Towards Sex offenders’ (ATS-21) scale

‘Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding’ (BIDR) scale

Procedure

Ethical considerations

Results

PSO Findings

ATS-21 Findings

BIDR Findings

Discussion

Limitations and future directions

Conclusion

References

Appendices

Appendix 1. Social media publication

Appendix 2. Case vignettes

Appendix 3. The Perceptions of Sex Offenders Scale (PSO) and Permission

Appendix 4 – The Attitudes Towards Sex Offenders Scale (ATS-21) and Permission

Appendix 5 – Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (BIDR)

Appendix 6 – Participant Information Sheet

Appendix 7 – Consent form

Appendix 8 – Online Debrief Form

Appendix 9 – Data Authenticity Form

Appendix 10 – Ethical Approval Code

Appendix 11 – SPSS Output – Assumptions of Normality

Appendix 12 – PSO Findings

Appendix 13 – ATS-21 Findings

List of abbreviations

SOA – Sexual Offences Act

CSEW – Crime Survey England and Wales

ONS – Office for National Statistics

BPS – British Psychological Society

UK – United Kingdom

TA – therapeutic alliance

GLM – Good Lives Model

RNR – Risk-Need-Responsivity model

PSO – Perceptions towards Sex Offenders scale

CATSO – Community Attitudes Towards Sex Offenders scale

S&M – Sentencing and Management (PSO subscale)

SE – Stereotype Endorsement (PSO subscale)

RP – Risk Perception (PSO subscale)

ATS-21 – Attitudes Towards Sex offenders scale (revised – 21-items)

T – Trust (ATS subscale)

I – Intent (ATS subscale)

SDATS – Social Distance (ATS subscale)

BIDR – Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding scale

IM – Impression management (BIDR subscale)

S-D – Self-deception (BIDR subscale)

ANOVA – Analysis of variance

Introduction

Data from the most recent 2013/2014 Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) shows that 19.9% of women and 3.6% of men, aged between 16-59 were victims once or more of sexual assault (ONS, 2015). This suggests that a significant fraction of the adult population has experienced sexual assault victimisation and often forensic psychologists, therapists and other professionals that work with sex offenders can be part of this fraction (Willmot, 2013). A sex offender is legally a generic term for all individuals convicted of crimes involving sex. This can range from sexual touching to penetration and the imprisonment time may differ. Within this study, a sex offender is a person that has been found guilty and convicted of a sexual offence under the Sexual Offences Act (SOA; 2003), chapter 42, part 3: sexual assault. For the purpose of this study it is not essential to evaluate any other type of sexual offences. Within the Sexual Offences Act, sexual assault is described as an offence where an individual (A) intentionally touches another individual (B), the touching is sexual, B does not consent to the touching and A does not reasonably believes that B consents (SOA, 2003).

Literature Review

There seems to be a general agreement throughout literature that sex offenders are much more resented by society in comparison to any other offender, even within the prison system (Akerstrom, 1986; Kjelsberg & Loos, 2008). Understandably, sexual assault is a term that often generates strong and negative emotions mostly due to its invasive context but more importantly, as it is considered a violation of one’s fundamental human rights (Corăbian, 2016). Empirical evidence has extensively developed ways in which the resentment the public hold towards sex offenders can be measured such as attitude and perception scales (i.e. Church, Wakeman, Miller, Clements & Sun, 2008; Hogue, 1993; Harper & Hogue, 2014b). Attitudes are most often measured through self-reports that aim to reflect the individual’s belief, feelings or behaviour towards an attitude object (Vogel & Wanke, 2016). The existent attitudes and perceptions scales are mostly developed as a Likert scale (Likert, 1932) or a similar method and thus measured on a spectrum with two opposite ends (i.e. very negative versus very positive) (Vogel & Wanke, 2016). Hogue (2009) suggests that in order for the attitudes towards sex offenders to be socially acceptable they have to fall somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. Accordingly, with the use of scales that ask the appropriate questions (items), it is possible to determine the thoughts, feelings and views that the individual has on a certain topic (Stuart-Hamilton, 2007). Some noteworthy limitations and issues might arise when attempting at measuring attitudes with the use of multi-item scales. The most common concern seems to be the participant’s awareness (‘reactivity’) of the attitude measurement and this may be a threat to the overall validity of the scale (Vogel & Wanke, 2016). In line with the British Psychological Society Code of Ethics and Conduct (BPS, 2010), participants have to be fully informed about the study they are taking part in, therefore this makes it very hard to conceal what the study is actually measuring. Not only that, but it is easy to determine if the study is asking for the opinion, thoughts, feelings and behaviours on a particular topic even with the attempt to conceal the actual purpose of the experiment. In addition, this study attempted at identifying if the participants are distorting their answers to meet the socially acceptable criteria with an added scale at the end in order to determine how much the participants may have distorted their answers. This is perhaps one solution in making sure the collected data is valid and it represents the actual attitudes of the sample. All things considered, measuring attitudes is not as effortless as it may seem and they can easily be influenced by extraneous variables.

The literature on attitudes is vast and mixed in their theoretical approaches (Albarracin, Johnson, Zanna & Kumkale, 2005; Oskamp & Schultz, 2005; Vogel & Wanke, 2016). Therefore, they can have more than one definition in the literature of social psychology, but the basic statement that most are based on is that attitudes are “a summary evaluation of an object of thought” (Vogel & Wanke, 2016, p. 2). This evaluation can be in favour or disfavour towards an attitude object (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). As mentioned, throughout research, attitudes fall under several theoretical models. The ‘tripartite model’ (Allport, 1935) suggests that attitudes are comprised of affective, behavioural and cognitive responses. This has been challenged within the literature, Oskamp and Schultz (2005) affirm that the three responses of the model are not always related or present together, however this does not determine that the attitude is not present. Another theoretical model is the ‘file-drawer model’ and suggests that attitudes are mental files stored in memory, which one consults when performing an evaluation of an attitude object (Wilson, Lisle & Kraft, 1990). This has been challenged by another theory, the ‘attitudes-as-constructions perspective’ that concludes that individuals do not retrieve a previously filed memory but they create a new attitude based on surroundings (Wilson & Hodges, 1992). Despite the significant discrepancy in definitions and the theoretical basis of attitudes, the common ground implies that attitudes are composed of beliefs, affect and overt behaviour and they influence and interact with each other (Albarracin et al., 2005; Oskamp & Schultz, 2005). Nevertheless, attitudes have the potential to affect behaviour.

The relationship between attitudes and behaviour is complex and not always certain. A considerable amount of research has focused on this relationship extensively and it broadly recognised the relevance of attitudes in predicting behaviour (Ajzen, 2001). Although the link between attitudes and behaviour is somewhat logical, early research has failed to provide empirical evidence that successfully supports this link (Vogel & Wanke, 2016). In a literature review, Wicker (1969) found no significant relationship between attitudes and overt behaviour. Moreover, he suggested that perhaps the concept of attitudes is non-existent and they cannot justify for overt behaviour. Following research began examining the different factors that can affect and moderate the link between attitudes and behaviour (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2005; Fazio & Roskos-Ewoldsen, 2005). They have found various explanations for previous inconsistent findings of the link between attitudes such as the multidimensionality of attitudes, response bias and other moderating factors (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2005). Ultimately, they produced a set of appropriate measures guidance that can increase the finding of an attitude-behaviour link. The ‘correspondence principle’ (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977) suggests that behavioural criteria must be included into the measure of attitude and it should follow four elements: action, target, context and time. The predictive power of attitudes can be therefore maximised if the ‘correspondence principle’ is adopted in empirical research (Ajzen & Fishbein 1977; 2005; Eagly & Chaiken, 1998). Additionally, general attitudes may provide a better prediction and explanation of a broad variety (situations and contexts) of discriminatory behaviours when compared to particularly specific attitudes (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2005).

Across literature, there have been many attempts at providing strong empirical support for the link between attitudes and behaviour together with the development of several theories. The theory of ‘reasoned action’ suggests that an individual’s intentions are the best predictors of one’s behaviour (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). The behavioural intention is a conscious decision to engage in certain behaviours and this is mediated by one’s attitude towards the behaviour and subjective norms (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). The theory of planned behaviour suggests that individual’s behaviour is in line with their intentions and perceived control over set behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). Collectively, the two theories imply that the base for behaviour are the initial intentions that in turn are influenced by an array of factors including attitudes towards that behaviour.

As noted above, attitudes can also be influenced by social interactions and this can result in participants distorting their answers to meet the desirable criteria for that interaction. However, social interactions are not the only influencer of attitudes. Attitudes can also be influenced by the media and this has been long-established, with empirical evidence suggesting that media plays a significant role in the nature of the attitudes towards sex offenders (Brown, Deakin & Spencer, 2008; Malinen, Willis & Johnston, 2014). It was found that public attitudes were being influenced by the media in most cases, especially with no direct contact with a sex offender (Brown et al., 2008; Kjelsberg & Loos, 2008).

Furthermore, in a UK based study, Brown et al. (2008) found that 90% of the participants reported to have obtained their knowledge about sex offenders from the media and they also felt that the media is somewhat exaggerating the offences in order to incite fear in society. The exaggeration in the media is most likely the generator of negative attitudes and stereotypes about this type of offender. A Canadian study asked professionals and sex offenders about their attitudes on the media’s impact on the reintegration of sex offenders. They found that there is an existent belief that the way media portrays sex offenders can negatively impact on reintegration and affect several risk factors (Corăbian & Hogan, 2012). Harper & Hogue (2017) suggest that the emotionality presented in the media may have a great impact on the way the public shapes their attitudes towards sex offenders. Moreover, the negative portrayal of sex offenders can have such a great negative impact that reintegration and desistance seem hopeless (Fox, 2015). Therefore, it is safe to conclude that the media has negatively shaped and influenced the attitudes towards sex offenders.

Although attitudes may not always be a very good predictor of future behaviour as they are easily influenced, it has been stated throughout the literature that attitudes are the basis for stigma (Goffman, 2009). Attitudes allow stigma to set in because of their evaluative (positive or negative) and subjective characteristics that happen at both a conscious and an unconscious level (Maio, Olson, Bernard & Luke, 2006). Stigma has been defined as an attribute that discredits the individual within the society, somewhat diminishing the individual “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one.” (Goffman, 1963, p.3). The stigmatisation process occurs when an individual has or is believed to have “some attribute or characteristic that conveys a social identity that is devalued in a particular social context” (Crocker, Major & Steele, 1998, p.505). Essentially, the two definitions accord that if an individual has met the criteria for a stigmatisation mark he or she is somewhat devalued in society. In the case of a sex offender, the stigmatisation mark is often linked to their offending behaviour and they are often considered to be a highly stigmatised population within the society (Evans & Cubellis, 2015; Griffin & West, 2006).

It is important to note that this stigma is relationship and context specific and it is not merely a characteristic of the person except in a social context (Major & O’Brien, 2005). Link and Phelan (2001) added that stigma is the result of factors that can correlate such as labelling, discrimination and stereotyping. The factors can also appear together and when that happens a justification is also present as to why the individual is devaluing, rejecting and excluding the stigmatised person (Link & Phelan, 2001; Ricciardelli & Moir, 2013). The identity of the stigmatised person is often reflective of society’s expectations and assumptions (the ‘virtual social identity’) and it reshapes how the stigmatised individual is seen (Goffman, 1963). The negative evaluations and stereotypes are generally well known and practised in a society (Crocker et al., 1998; Steele, 1997), thus the stigmatised individual is faced with stereotypes, labelling and discriminations across most social interactions and is often excluded and avoided (Major & Eccleston, 2004). Moreover, the literature suggests that the negative information that one holds of another has a greater impact on the general evaluation than positive information in a comparable situation (Ajzen, 2001). Nevertheless, the dehumanisation of the sex offender can affect their rehabilitation (Viki, Fullerton, Raggett, Tait & Wiltshire, 2012).

In order to provide ‘best practice’, the work of professionals working with sex offenders has to be “grounded in theoretical understanding” (Willmot, 2013, p.172). Willmot (2013) also suggests that the work of forensic psychologists should be respectful, boundaried and compassionate whilst acknowledging that this sometimes might be difficult. It is also safe the assume that the work of professionals should resemble a stigma-free approach. Willmot (2013) also points out to the importance of a good therapeutic alliance (TA) between the therapist and the sex offender. An investigation into the factors that are most likely to influence the client outcome, the ‘common factors’ were found to have the highest correlation with a positive therapy outcome than any specialised interventions (Lambert & Barley, 2001). Part of the ‘common factors’ and perhaps the most studied are the ‘person-centred facilitative conditions’ and the TA (Lambert & Barley, 2001). TA is plainly defined as the relationship between a client and their therapist or the outcome between the therapist’s approach and the client’s perception of the approach and the therapist (Marshall et al., 2003). TA was found to be at the centre of a positive treatment outcome in sex offender rehabilitation (Ross, Polaschek & Ward, 2008). Although little research has investigated the impact that negative attitudes can have on the successful rehabilitation of the sex offender, it is safe to assume that they have the potential to damage the TA. For example, empirical evidence suggests that the prison atmosphere (therapeutic or not) together with the attitudes of the professionals can negatively affect how stable the treatment is delivered and inevitably the treatment outcome (Schalast, Redies, Collins, Stacey & Howells, 2008; Ward, Day, Howells & Birgden, 2004). When working with sex offenders, the TA should also incorporate the Six Central Themes of Desistance (Farrall & McNeill, 2010). The negative attitudes that the therapist has towards the client could affect the applicability of the six themes of desistance in practice. For example, the second theme is referring to the development and maintenance of hope and motivation (Farrall & Calverley, 2006), however negative attitudes can hinder the development of hope and motivation and so on. Arguably, if the six themes of desistance are not applied in practice, this could lead to reoffending. The six themes of desistance are somewhat the basis to a strength-based approach such as the Good Lives Model (GLM; Ward & Steward, 2003) which was found to be successful in promoting desistance and lowering the risk of reoffending in sex offenders (Ward & Laws, 2010). In addition, the hope and motivation of the sex offender may also be hindered by the attitudes of the therapist. Before the GLM, practitioners were using a ‘What works’ approach with the application of a ‘Risk-Need-Responsivity’ (RNR; Andrews, Bonta & Hoge, 1990) that mostly suggested in targeting the offenders’ criminogenic needs. The main difference between the two approaches is in the focus of the treatment and arguably, another difference is the empirical views on the topic (see Andrews, Bonta & Wormith, 2011 and Ward, Yates & Willis, 2012). The RNR focuses on the weaknesses of the offender (i.e. criminogenic needs), whereas the GLM accentuates the strengths (i.e. primary goods). Thus, the criminogenic needs approach was criticised by empirical evidence suggesting that the identification of risk factors and subsequent treatment solely to reduce the level of risk may not necessarily achieve desistance (Ward, Mann & Gannon, 2007). Nevertheless, regardless of the approach taken in treatment, the focus should primarily be on the six themes of desistance due to their strong empirical basis and their emphasis on TA. If stigma endangers the TA connection, several other issues can arise, such as the loss of motivation to engage with the treatment programme (McMurran, 2003). The motivation and engagement of the offender, or rather the lack thereof is the greatest predictor of recidivism (Levenson & Macgowan, 2004).

As previously mentioned, attitudes are widely measure on a spectrum ranging between too negative or too positive. Throughout his work, Hogue (2009) has examined the impact of both negative and positive attitudes on the development of TA in the treatment of sex offenders. He suggests that negative attitudes allow a punitive and/or dismissive approach, which can significantly weaken the TA (Hogue, 2009). Although they are widely used in practice, confrontational approaches can discourage the offenders from taking responsibility for their actions and disempower them from changing their behaviour (Kear-Colwell & Pollock, 1997). Forcing them to accept the label of a sex offender can also hurt the TA, inhibit their engagement in treatment, and incite resistance in the client (Kear-Colwell & Pollock, 1997). Another significant issue that can arise as a result to negative attitudes for the sex offender is the failure to reintegrate into communities. For example, Levenson and Hern (2007) found that sex offenders could often be denied rent property and employment, which unavoidably can debilitate the successful reintegration. Subsequently, the offender can return to risky behaviours and eventually re-offend (Hanson & Bussiere, 1998). On the other side of the spectrum, when the attitudes are too positive towards the client may unlock different problems, which can also be regarded as negative. The most obvious effect that positive attitudes can have on the TA are boundary issues (Smith & Fitzpatrick, 1995). In this case, the healthy TA cannot be maintained which can also negatively affect the treatment outcome (Beech & Hamilton-Giachritsis, 2005). Moreover, overly positive attitudes can be viewed as a perceived normalisation of cognitive distortions and an acceptance of the offending behaviour (Hall & Hirschman, 1991) which arguably is inversely correlated with desistance. Positive attitudes towards the sex offender can also predispose the therapist to the vulnerability of being victimised (Farrenkopf, 1992). Overly positive attitudes somewhat disregard the victim and can influence the objective assessment of clinical change (Hogue, 2009). Across previous research, the positive attitudes towards sex offenders varies in regards to the participant’s gender. A significant amount of empirical evidence found women’s attitudes to be more positive (Ferguson & Ireland, 2006; Green, 2004; Radley, 2001) or males with more positive attitudes (Smith, 2008 cited in Hogue, 2009). Other studies found no difference between males and females (Hogue, 1993; 1995; Johnson, Hughes & Ireland, 2007). However, none of the above mentioned studies explored the idea of ‘relateability’ between the participant’s gender and the gender of the victim portrayed in the sexual offender presented to them.

The attitudes of psychology students are important and relevant as they are more likely than other graduates to be involved in the rehabilitation of the sex offender or the victim (Harper, 2012). The public attitudes towards sex offenders have been widely researched in different settings and under different contexts, however no research has been found that investigated the attitudes in relation to the victim. Data from the 2013/2014 CSEW (ONS, 2015) also shows that the victim can be predisposed to stigma perhaps as much as the sex offender can. One in eleven people thought that the victim was ‘completely’ or ‘mostly’ responsible for a sexual assault or rape by someone if they have been heavily flirting beforehand (9%), when they were under drug influence (8%) and while they were drunk (6%). Although the results are indicative of the members of the general population, professionals are part of the general population just as any individual and they are too predisposed to showing negative attitudes towards the victims to sexual offences. The literature around the impact of negative attitudes on the treatment outcomes of the victims of sexual violence is limited. The existent research in this area has mostly investigated the attitudes towards rape victims (Barber, 1974; Ward, 1988), suggesting that the attitudes towards victims of sexual violence are important as they can affect the quality of victim care. Therefore, it is argued that the victim is important as it can influence the attitudes towards sex offenders. For example, Weekes, Pelletier and Beaudette (1995) found that the sex offenders that victimise women and children are viewed as more immoral and ‘mentally ill’ than other sex offenders due to their victim’s perceived vulnerability factor. This is important as the treatment outcome and the desired desistance is hindered by the very important factors that can be somewhat controlled (influenced by attitudes) and perhaps the characteristics of the victim is just another factor. Therefore, this study is set out to examine what is the potential impact of victim’s gender on the general attitudes towards sex offenders as measured in a university sample. In line with previous research, the hypotheses used to guide this study are:

H1 – The attitudes towards sex offenders will be significantly more negative when the victim is a female.

H2 – The attitudes towards sex offenders will be significantly more positive when the victim is a male.

The predictions will be investigated in order to answer the following research questions:

Does the victim’s gender affect (positively or negatively) the general attitudes towards sex offenders? Does the gender of the participant reflect the attitudes?

Method

Design

The research follows a repeated-measures design where each participant covered both male offender – male victim and male offender – female victim conditions. Student attitudes (dependent variable) are measured in both conditions. The independent variables in this study are the gender (male or female) of the victim and the gender of the participant (male or female).

Participants

The participants are part of an opportunity sample recruited with the use of an advertisement published on social media websites (e.g. Facebook; see Appendix 1) asking all students that were enrolled at university studying a degree in Clinical, Counselling or Forensic Psychology for their willingness to take part. Some participants have also been recruited with the use of a publication on the Psychological Research on the Net website for further recruiting in an attempt to meet the desired number of participants.

One hundred and seventy-five participants have taken part, with N=124 completing all questionnaires. Out of the final sample, 87% are females (N=108) and 13% males (N=16), N=41 claim to study for a Forensic degree, N=47 a Clinical degree and N=36 a Counselling degree at an UK University across all three levels (see Table 1). Participants age ranges between 18 and 51 (M=21.94, SD=4.63).

Part of the departmental research participation scheme in place at the University of Worcester, first and second year students enrolled at this university received 1 credit (1=15 minutes) that can be used for their final year research project. No other participants received incentives. None of the participants were informed about the hypotheses of the study.

| Table 1

Variation across the three university years based on the studied degree |

|||

| Year 1 (Level 4) | Year 2 (Level 5) | Year 3 (Level 6) | |

| Clinical | N=18 | N=21 | N=8 |

| Counselling | N=11 | N=19 | N=6 |

| Forensic | N=10 | N=17 | N=14 |

Materials

Case vignettes

For the purpose of this experiment, two short vignettes were produced both describing an act of sudden sexual assault against a victim (male and female) by a male perpetrator. The case vignettes were adapted from a media publication (see Appendix 2) and they portray very similar sexual acts, where the mode of transportation is different to avoid confusion between cases. The gender of the victim is also manipulated in order to measure its effect on the dependent variable (attitudes).

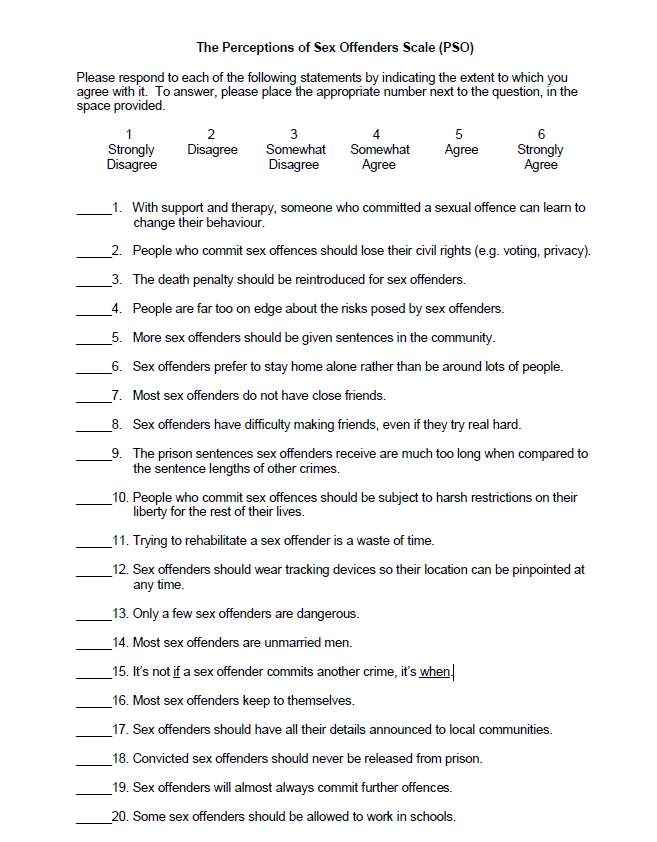

‘Perceptions towards Sex Offenders’ (PSO) scale

The PSO is a 20-item self-report questionnaire developed to assess the perceptions towards sex offenders that people might have. It was developed by Harper and Hogue (2014b) and it is an adaptation from the ‘Community Attitudes Toward Sex Offenders’ (CATSO) scale (Church, Wakeman, Miller, Clements & Sun, 2008). The adaptation wanted to change the original use of the CATSO and turn it into a more of an outcome scale, and where the perceptions about sex offenders can be measured empirically and accurately pre and post educational interventions (Harper & Hogue, 2014b). Harper and Hogue (2014) suggest that what the PSO is set out to examine is the participators’ understanding of who sex offenders are and their perceptions of how they should be treated, sentenced and managed post-conviction. The PSO is comprised of three factors: ‘Sentencing and Management, ‘Stereotype Endorsement’ and ‘Risk Perception’ all of which have multiple items (six are reverse scored) in the shape of statements (e.g. “Trying to rehabilitate a sex offender is a waste of time.”) (see Appendix 3 for a full overview of this scale). The participants are asked to rate the extent to which they agree or disagree with each statement on a 6-point Likert scale and the overall possible score can range from 0 to 100, where high score indicates negative attitudes (i.e. punitive, stereotype-driven perceptions of sex offenders). Overall, the scale showed a great internal consistency (α = .92), as well as for each factor: ‘sentencing and management’ (α = .93), ‘stereotype endorsement’ (α = .85) and ‘risk perception’ (α = .81).

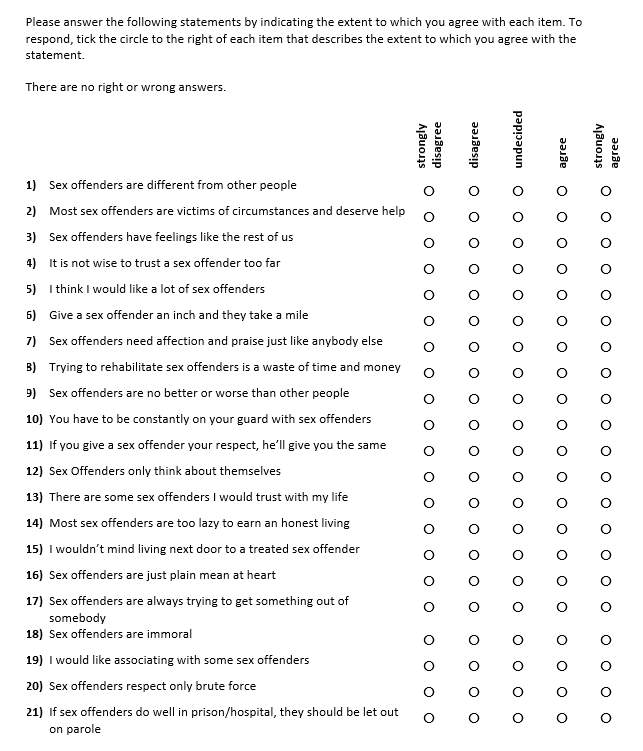

‘Attitudes Towards Sex offenders’ (ATS-21) scale

The ATS-21 is a shortened and revised version of the ATS (Hogue, 1993). The ATS was originally adapted from the ‘Attitudes towards Prisoners’ scale (Melvin, Gramling & Gardner, 1985) by replacing the word ‘prisoners’ with ‘sex offenders’ and is comprised of 36 items. The ATS-21 is a 21-item (eleven reversed scored) self-report questionnaire comprised of three factors: ‘Trust’, ‘Intent’ and ‘Social Distance’ measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The overall scores can range from 0 to 84, where the highest score indicates highly positive attitudes towards sex offenders. The scale was revalidated by Hogue (2015) and it showed a strong correlation with the original ATS (r = .98, p <.001 similar to the pso ats-21 constitutes of statements think i would like a lot sex offenders. appendix for full overview this scale overall showed great internal consistency .94 as well each factor: .84 .87 and distance .83>

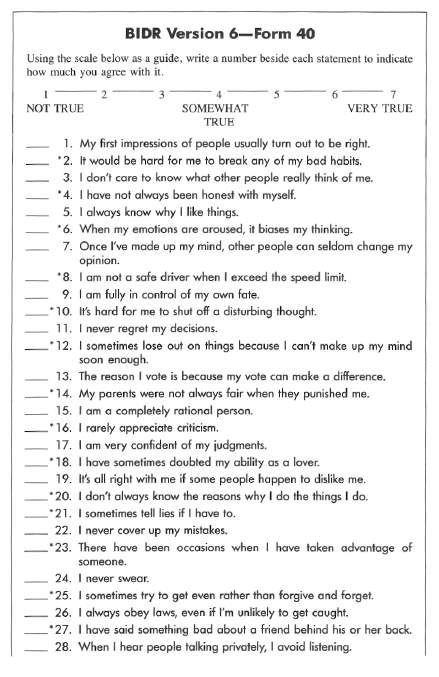

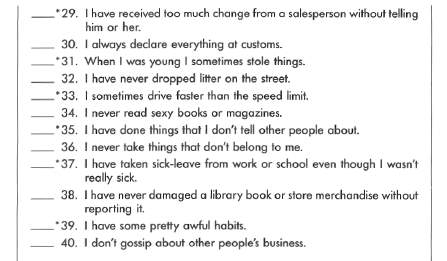

‘Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding’ (BIDR) scale

The BIDR is a 40-item questionnaire developed by Paulhus (1984; 1986; 1994). The socially desirable responding is measured on a 7-point Likert scale with questions about self-deception and impression management (see Appendix 5 for a full overview of this scale). An example of an item is: “I sometimes tell lies if I have to.”. Scores on self-deception and impression management can range from 0 to 20 and are attributed to categories (low 0-6; moderate 7-13; high 14-20) where higher scores indicate desirable responding. The scale indicates great internal consistency for both subscales (‘impression management’ α = .84; ‘self-deception’ α = .73; Holden, Starzyk, McLeod & Edwards, 2000; Kroner & Weeks, 1996).

Procedure

Participants that agreed to take part in the study were required to access an online survey hosted by esurveycreator.co.uk. Participants were greeted with an information sheet (see Appendix 6) that explained in enough detail what was required of them throughout the study. This was in place to make sure that the participants were fully informed of the study’s sensitive topic. All participants had to complete the online consent (see Appendix 7) form before continuing. Demographics were then collected and this included age, gender, degree taken (clinical, counselling or forensic) and the degree level (year 1, 2 or 3). After reading the vignettes, the two questionnaires, PSO and ATS-21 were administered to each participant on separate pages. Considering that the victims were of a different gender in each vignette, each participant responded to both questionnaires twice. The participants were randomly assigned to read the male – female vignette first or the male – male vignette first. Towards the end of the survey, the BIDR was administered in order to identify how much the participants may have distorted their answers. Once the tasks were done, each participant was presented with a debrief page (see Appendix 8) where they were being thanked for their contribution, contact details for the researcher if they had any remaining questions, links to available local support and useful links.

Ethical considerations

Taking into consideration the British Psychological Society Code of Ethics and Conduct (2010) the participants were provided with sufficient information (see Appendix 6) about the study to avoid the code of deception. Informed consent (see Appendix 7) was taken from every participant in conformity with the Code of Responsibility (BPS, 2010). Furthermore, in line with the responsibility guidelines, the above mentioned published advertisement had a prior note specifying that the process will include fictional scenarios depicting sexual assault, giving participants the option to not access the link if they do not feel comfortable doing so. The supervisor has authenticated (see Appendix 9) the data used in this study. The University of Worcester Institute of Health and Society Ethics Committee ethically approved this experiment (see Appendix 10).

In order to try and overcome any possible distress caused, the participants were debriefed in accordance with the responsibility guidelines (BPS, 2010) and were given contact details of professionals to support the participants if distressed was caused by this experiment.

Results

Participant’s responses to the PSO and the ATS-21 scales were compared for both the male victim and the female victim conditions in order to determine whether the attitudes towards sex offenders were influenced by the gender of the victim. All participants (N=124) completed both scales for each group: a) male offender – male victim; b) male offender – female victim.

The results of both the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and the Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that the majority of the subscales have violated the assumptions of normality (see Appendix 11). Therefore, Friedman’s ANOVA was conducted instead in order to measure student’s attitudes towards sex offenders in relation to the gender of the victim. The non-parametric Friedman test of differences among repeated measures concluded a Chi-square value of 757.41 which was significant (p<.01 therefore it is safe to conclude that student attitudes towards sex offenders were significantly affected by the gender of victim>2(11) = 757.41, p <.05>

PSO Findings

Wilcoxon tests were used to further investigate this finding. The signed-ranks test indicated that there were no statistically significant differences in the perceptions towards sex offenders based on the victim of the gender. Participants scored similarly on the ‘Stereotype Endorsement’ (Z = -1.49, p = .136) and ‘Risk Perception’ (Z = -1.76, p = .079) and this indicated that the results were not statistically significant. Although there was an attitude difference within the ‘Sentencing & Management’ subscale that indicated more punitive scores towards sex offenders when the victim was a female, the results were not statistically significant (Z = -.057, p = .955). Overall, the measurements made by the PSO did not indicate any statistically significant results in attitudes between the answers when the victim was female nor when the victim was a male, although some differences between the means can be observed (see Appendix 12).

ATS-21 Findings

Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks test was used to identify the difference in attitudes towards sex offenders as measured by the ATS-21 when mediated by the gender of the victim. Participants scored similarly on the ‘Social Distance’ factor (Z = -.746, p = .455) indicating that there was no statistically significant difference between the responses on the two vignettes. There was no statistically significant difference in the scores measuring ‘Trust’ (Z = -1.44, p = .149), however a small difference in means can be observed (see Appendix 13) indicating that the participants believed the sex offender to be less trustworthy when the victim was a female. A statistically significant difference was found in the scores measuring the perceived ‘Intent’ of the sex offender (Z = -3.50, p = .000). This suggests that the participants indicated a perceived malicious intent in the actions of the sex offender when the victim was a female. These findings partially support the hypothesis that the attitudes will be more negative when the victim is a female and more positive when the victim is a male.

BIDR Findings

The results presented in the two subscales of the BIDR, ‘Self-deception’ (M = 4.19, SD = .733) and ‘Impression Management’ (M = 3.97, SD = .767) indicated by investigating the mean that overall (M = 8.05, SD = 1.18), the participants (N=124) might have slightly (M = 8.05 out of a possible of 20) distorted their answers to meet the socially desirable criteria (Paulhus, 1984).

Discussion

This study used a repeated-measures design to examine the effect of the victim’s gender on the general attitudes towards sex offenders using fictitious case vignettes to help create a ‘visual’ image of the scenario for participants. One hundred and twenty-four psychology students, part of an opportunity sample, completed the tasks of this study. All participants were current students (at the time of this experiment) reading either a forensic, clinical or counselling degree and were varied across the three years of study. The main aim was to explore if the attitudes are different towards the general population of sex offenders when the victim was either a female or a male. The second aim of this study was to explore whether the gender of the participant was the determinant of overall attitudes when this could relate to the gender of the victim. The study hypothesised that the attitudes will be significantly more negative when the victim is a female due to their perceived vulnerability (Weekes, Pelletier & Beaudette, 1995) and consequently the attitudes will be significantly more positive when the victim is a male.

In order to assess this, the two scales used were divided in three subscales accordingly as they measured different aspects of attitudes and a Friedman’s ANOVA was performed. Overall, the hypotheses were only partially supported. Out of the six subscales (combined), only the scores on one subscale were statistically significant (p = .000). The results showed that attitudes had a negative effect when the victim was a female. This suggests that the participants perceived sex offenders to be more malicious in their ‘Intent’ when the victim was a female.

Despite the promising findings, this research has found no other statistically significant (p > .05) differences in attitudes. This can be explained in a number of ways. For example, looking at Burt’s (1980) work, within his sample, he found that the younger and better educated people were, the less likely they are to hold stereotypic views. Transitioning his findings onto this study, the results could imply that the non-significance in both conditions (male offender – male victim and male offender – female victim) was due to the sample of ‘better educated’ university students. However, it is hard to assume this in its entirety as there was no ‘control’ group of less educated people to compare the findings. Therefore, this could be examined further in future research.

Moreover, using a UK university sample, Harper (2012) did find that undergraduate psychology students showed significantly more negative and punitive attitudes towards sex offenders and he argued that “undergraduate psychology degrees do not go far enough to address some of the stigmatised views” (pp.1). Arguably, this study adds to the view that perhaps undergraduate psychology courses are well-equipped as within this sample the attitudes were roughly in between the two ends of the spectrum. Hogue (2009) suggests that in order for the attitudes to be socially acceptable and non-damageable to treatment, they should sit somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. From this perspective, this study contributes to the explanation that the students in UK university are successfully preparing for providing ‘best practice’ for both the sex offender and the victims of sexual violence in the future. This is an implication for education worth considering.

Another possible explanation for the non-significant results is that, judging by the answers on the BIDR, participants might have slightly distorted their answers. Paulhus (1986) explains that individuals have a tendency to distort their answers to meet the socially desirable criteria. The current data presented a moderate (7-13 scoring) probability (M = 8.05, SD = 1.18) that the student distorted their answers. Unfortunately, other than accepting this as a limitation to the study, this extraneous variable could have not been controlled for in any other way.

Limitations and future directions

The first limitation of the current research might be using the online survey. The rationale for using an online survey was to avoid putting pressure on the participants, however arguably reducing the pressure can also belittle the demand characteristic of the situation (Paulhus, 1991). Thus, the undergraduate students with negative attitudes might have simply refused to participate. This could have potentially affected the applicability of this study in practice. Finding a balance between reducing the pressure of the demand characteristics and allowing self-selection will arguably remain a dispute for subsequent researchers.

In his study, Burt (1980) found that the younger the sample, the less stereotypic views they had. Due to its purpose, the current research was limited in its accessibility to well-educated older practitioners. However, for future research this could be an interesting and rationalised approach to the attitudes towards sex offenders when investigating the impact of the victim’s gender. Future studies could also analyse different characteristics of victims and explore their impact on the overall attitudes about sex offenders and the perceived implications for practice. Not only, would this be interesting, but it could also add to the notion of the victim portrayal affecting the attitudes of practitioners and its effect on the treatment of the sex offender but also on the treatment of the victim. Although previous studies on the attitudes towards victims has been done, this is fairly outdated and has only researched rape victims (Barber, 1974; Ward, 1988). Therefore, subsequent research could study the implications of stereotypes and attitudes and the implications for the treatment of the victims of other types of sexual violence. For example, sexual assault can generate different stereotypes when compared to rape as this is perceived to be more violent.

The research around the gender differences in attitudes towards sex offenders is vast and mixed. Previous research has had mixed findings when they investigated the effect on the gender of the participant on the attitudes towards sex offenders. For example, Smith (2008 cited in Hogue, 2009) found males to have more positive attitudes while other research (Ferguson & Ireland, 2006; Green, 2004; Radley, 2001) found females to be more positive in their attitudes. Different research found no differences between genders in measured attitudes (Hogue, 1993; 1995; Johnson, Hughes & Ireland, 2007). The notion of the participant’s gender was initially targeted within this study, however due to the unexpected inequality within the sample, this could not be investigated. Although this study aimed at recruiting over 120 participants through opportunity samples with equal demographics, only 18 males have taken part in the experimental phase. With a high dominance of females (N=108) across the participant sample (N=124), the results would have not been suitable for comparison as they would have lacked the statistical power due to the small sample size of men. Future studies are encouraged to investigate further the notion of the gender association between the practitioner and the victim of a sexual offences and what implications this could bring to practice. However, none of the above mentioned studies explored the idea of ‘relateability’ between the participant’s gender and the gender of the victim portrayed in the sexual offender presented to them. This could potentially be explored in future studies as well and determine how much do the characteristics shared by the practitioner and the victim influences the attitudes. Moreover, the research on the attitudes and behaviour has proven challenging throughout the existent empirical evidence (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2005; Fazio & Roskos-Ewoldsen, 2005). Perhaps subsequent research should further investigate this issue and assess this in practice as an established link, or lack thereof, could significantly influence the outcome of practice and treatment.

In the future, researchers could conduct studies to identify the link between attitudes towards sex offenders and their victims among university students. Although the current work suggests that there is no direct impact of the victim’s gender on the overall attitudes towards sex offenders, this study is accompanied by many limitations. Therefore, a stronger replication with a more diverse sample and perhaps more characteristics could potentially alter the present results.

In conclusion, the present study has contributed to the gap in literature addressing attitudes towards sex offenders. The focus of this experiment was to analyse university students’ attitudes towards sex offenders in relation to victims’ gender. The results indicated that students had significantly more negative attitudes towards sex offenders when the victim of the offence was a female. This enabled students to perceive that the sex offender is somewhat more maliciously intended when the victim was a female rather than a male. However, there was no other statistically significant differences among the other measured concepts: stereotype endorsement, risk perception, sentencing and management, social distance and trust. This may have been due to a number of plausible reasons for example, the sample used in this study reflected the young population, the students may have slightly distorted their answers to meet the socially desirable criteria and/or the several limitations of this research that may have influenced the results (i.e. possible extraneous variables uncontrolled for). Therefore, future research may consider some or all of the future directions considered in this study, such as to test these hypotheses in a more experienced older population (i.e. current practitioners).

References

Åkerström, M. (1986). Outcasts in prison: The cases of informers and sex offenders. Deviant Behavior, 7(1), 1-12.

Albarracín, D., Johnson, B. T., Zanna, M. P., & Kumkale, G. T. (2005). Attitudes: Introduction and scope. The handbook of attitudes, 3-19.

Allport, G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In C. Murchison (Ed.), Handbook of Social Psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 798-844). Worcester, MA: Clark University Press.

Ajzen, I. (2001). Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual review of psychology, 52(1), 27-58.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179-211.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2005). The influence of attitudes on behavior. The handbook of attitudes, 173, 221.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological bulletin, 84(5), 888.

Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Hoge, R. D. (1990). Classification for effective rehabilitation: Rediscovering psychology. Criminal justice and Behavior, 17(1), 19-52.

Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Wormith, J. S. (2011). The risk-need-responsivity (RNR) model: Does adding the good lives model contribute to effective crime prevention?. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(7), 735-755.

Barber, R. (1974). Judge and jury attitudes to rape. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 7(3), 157-172.

Beech, A. R., & Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. E. (2005). Relationship between therapeutic climate and treatment outcome in group-based sexual offender treatment programs. Sexual Abuse, 17(2), 127-140.

British Psychological Society (2010). Code of Human Research Ethics. Leicester: BPS.

Brown, S., Deakin, J., & Spencer, J. (2008). What people think about the management of sex offenders in the community. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 47(3), 259-274.

Burt, M. R. (1980). Cultural myths and supports for rape. Journal of personality and social psychology, 38(2), 217.

Church, W. T., Wakeman, E. E., Miller, S. L., Clements, C. B., & Sun, F. (2008). The community attitudes toward sex offenders scale: The development of a psychometric assessment instrument. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(3), 251-259.

Craig, L. A. (2005). The impact of training on attitudes towards sex offenders. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 11(2), 197-207.

Corăbian, G. (2016). Working towards desistance: Canadian public’s attitudes towards sex offenders, sex offender treatment, and policy. Doctoral dissertation submitted at University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon.

Corăbian, G., & Hogan, N. (2012). Collateral effects of the media on sex offender reintegration: perceptions of sex offenders, professionals, and the lay public. Sexual Offender Treatment, 7(2), 10.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1998). Attitude structure and function. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds). The Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th ed. Vol. 1 (pp. 269-322). New York: McGraw Hill.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

Evans, D. N., & Cubellis, M. A. (2015). Coping with stigma: How registered sex offenders manage their public identities. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(3), 593-619.

Farrall, S., & McNeill F. (2010). 6. Desistance Research and Criminal Justice, Part 3 – Addressing Crime Prevention. In M. Herzog-Evans (Ed.), Transnational criminology manual (pp.203-221). Wolf Legal Publisher. Retrieved from http://www.cep-probation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Farrall_McNeill_Transnational_Criminology_Manual.pdf

Farrenkopf, T. (1992). What happens to therapists who work with sex offenders?. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 18(3-4), 217-224

Fazio, R. H., & Roskos-Ewoldsen, D. R. (2005). Acting as We Feel: When and How Attitudes Guide Behavior. In T. C. Brock & M. Green (Eds.) Persuasion: Psychological insights and perspectives (2nd ed., pp. 41-62). Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications

Ferguson, K., & Ireland, C. (2006). Attitudes towards sex offenders and the influence of offence type: A comparison of staff working in a forensic setting and students. The British Journal of Forensic Practice, 8(2), 10-19.

Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fox, K. J. (2017). Contextualizing the policy and pragmatics of reintegrating sex offenders. Sexual Abuse, 29(1), 28-50.

Goffman, E. (2009). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon and Schuster Inc. New York.

Green McGowan, M. (2004). Who is the predator? How law enforcement, mental health (forensic and nonforensic), and the general public stereotype sex offenders. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Dissertations & Theses: Full Text. (Publication No. AAT 3129997).

Griffin, M. P., & West, D. A. (2006). The lowest of the low? Addressing the disparity between community view, public policy, and treatment effectiveness for sex offenders. Law & Psychology Review, 30, 143–169.

Hanson, R. K., & Bussiere, M. T. (1998). Predicting relapse: a meta-analysis of sexual offender recidivism studies. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 66(2), 348.

Harper, C. A. (2012). In pursuit of the beast: undergraduate attitudes towards sex offenders and implications for society, rehabilitation and British psychology education. Internet Journal of Criminology.

Harper, C. A., & Hogue, T. E. (2014b). Measuring public perceptions of sex offenders: reimagining the Community Attitudes Toward Sex Offenders (CATSO) scale. Psychology, Crime & Law, 21(5), 452-470.

Harper, C. A., & Hogue, T. E. (2017). Press coverage as a heuristic guide for social decision-making about sexual offenders. Psychology, Crime & Law, 23(2), 118-134.

Harper, C. A., & Hogue, T. E. (2015). The emotional representation of sexual crime in the national British press. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 34(1), 3-24.

Hogue, T. E. (2015, July). Attitudes to sexual offenders. Paper presented at the BPS Division of Forensic Psychology Annual Conference. Manchester, UK.

Hogue, T. E. (2009, June). Attitudes Toward Sexual Offenders; what impact on clinical practice. Presented at the International Association of Forensic Mental Health Services Annual Conference (IAFMHS), Edinburgh, UK.

Hogue, T. E. (1993) ‘Attitudes towards Prisoners and Sexual Offenders’. In N. K. Clark and G. M. Stephenson (eds), Sexual Offenders: Context, Assessment and Treatment (27–32). Leicester: BPS.

Hogue, T. E. (1995). Training multi-disciplinary teams to work with sex offenders: Effects on staff attitudes. Psychology, Crime & Law, 1, 227-235.

Holden, R. R., Starzyk, K. B., McLeod, L. D., & Edwards, M. J. (2000). Comparisons among the holden psychological screening inventory (HPSI), the brief symptom inventory (BSI), and the balanced inventory of desirable responding (BIDR). Assessment, 7(2), 163-175.

Johnson, H., Hughes, J. G., & Ireland, J. L. (2007). Attitudes towards sex offenders and the role of empathy, locus of control and training: A comparison between a probationer police and general public sample. The Police Journal, 80(1), 28-54.

Kjelsberg, E., & Loos, L. H. (2008). Conciliation or condemnation? Prison employees’ and young peoples’ attitudes towards sexual offenders. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 7(1), 95-103.

Kroner, D. G., & Weeks, J. R. (1996). Balanced inventory of desirable responding: Factor structure, reliability, and validity with an offender sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 21, 323-333.

Lambert, M. J., & Barley, D. E. (2001). Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome. Psychotherapy: Theory, research, practice, training, 38(4), 357.

Levenson, J. S., & Hern, A. L. (2007). Sex offender residence restrictions: Unintended consequences and community reentry. Justice Research and Policy, 9(1), 59-73.

Levenson, J. S., & Macgowan, M. J. (2004). Engagement, denial, and treatment progress among sex offenders in group therapy. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 16(1), 49-63.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 140, 1-55.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual review of Sociology, 27(1), 363-385.

Maio, G.R., Olson, J.M., Bernard, M.M, & Luke, M.A. (2006). Ideologies, values, attitudes, and behavior. In J. Delamater (Ed.), Handbook of Social Psychology (pp. 283-308). New York: Kluwer-Plenum.

Major, B., & Eccleston, C. P. (2004). Stigma and social exclusion. In D. Abrams, J. Marques, & M. A. Hogg (Eds.), Social Psychology of Inclusion and Exclusion (pp.63-87). New York: Psychology Press.

Major, B., & O’Brien, L. T. (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review Psychology, 56, 393-421.

Malinen, S., Willis, G. M., & Johnston, L. (2014). Might informative media reporting of sexual offending influence community members’ attitudes towards sex offenders?. Psychology, Crime & Law, 20(6), 535-552.

Marshall, W. L., Fernandez, Y. M., Serran, G. A., Mulloy, R., Thornton, D., Mann, R. E., & Anderson, D. (2003). Process variables in the treatment of sexual offenders: A review of the relevant literature. Aggression and violent behavior, 8(2), 205-234.

McMurran, M. (Ed.). (2003). Motivating offenders to change: A guide to enhancing engagement in therapy (Vol. 52). John Wiley & Sons.

Melvin, K. B., Gramling, L. K., & Gardner, W. M. (1985). A scale to measure attitudes toward prisoners. Criminal Justice and Behaviour, 12, 241-253.

Oskamp, S., & Schultz, P. W. (2005). Attitudes and opinions. Psychology Press.

Paulhus, D. L. (1994). Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding: Reference manual for the BIDR Version 6. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia at Vancouver.

Paulhus, D. L. (1991). Measurement and control of response bias. In J.P. Robinson, P.R. Shaver, & L.S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes (pp. 17-59). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Paulhus, D. L. (1986). Self-deception and impression management in tests responses. In a Angleitner & J. S. Wiggins (Eds.), Personality assessment via questionnaire (pp. 143-165). New York: Springer.

Paulhus, D. L. (1984). Two-component models of socially desirable responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 598-609.

Radley, L. (2001). Attitudes towards sex offenders. Forensic Update, 66, 5-9.

Ricciardelli, R., & Moir, M. (2013). Stigmatized among the stigmatized: Sex offenders in Canadian penitentiaries. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 55(3), 353-386.

Schalast, N., Redies, M., Collins, M., Stacey, J., & Howells, K. (2008). EssenCES, a short questionnaire for assessing the social climate of forensic psychiatric wards. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 18(1), 49-58.

Sexual Offences Act (2003) c.42, London: The Stationary Office.

Smith, D., & Fitzpatrick, M. (1995). Patient-therapist boundary issues: An integrative review of theory and research. Professional psychology: research and practice, 26(5), 499.

Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American psychologist, 52(6), 613.

Stuart-Hamilton, I. (2007). Dictionary of psychological testing, assessment and treatment. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Viki, G. T., Fullerton, I., Raggett, H., Tait, F., & Wiltshire, S. (2012). The role of dehumanization in attitudes toward the social exclusion and rehabilitation of sex offenders. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(10), 2349-2367.

Vogel, T., & Wanke, M. (2016). Attitudes and attitude change. Psychology Press.

Ward, C. (1988). The attitudes toward rape victims scale. Psychology of women quarterly, 12(2), 127-146.

Ward, T., Day, A., Howells, K., & Birgden, A. (2004). The multifactor offender readiness model. Aggression and violent behavior, 9(6), 645-673.

Ward, T., & Laws, D. R. (2010). Desistance from sex offending: Motivating change, enriching practice. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 9(1), 11-23.

Ward, T., Mann, R. E., & Gannon, T. A. (2007). The good lives model of offender rehabilitation: Clinical implications. Aggression and violent behavior, 12(1), 87-107.

Ward, T., & Stewart, C. A. (2003). The treatment of sex offenders: Risk management and good lives. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34(4), 353.

Ward, T., Yates, P. M., & Willis, G. M. (2012). The good lives model and the risk need responsivity model: A critical response to Andrews, Bonta, and Wormith (2011). Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39(1), 94-110.

Weekes, J. R., Pelletier, G., & Beaudette, D. (1995). Correctional officers: How do they perceive sex offenders?. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 39(1), 55-61.

Wicker, A. W. (1969). Attitudes versus actions: The relationship of verbal and overt behavioral responses to attitude objects. Journal of Social issues, 25(4), 41-78.

Willmot, P. (2013). Sexual Offenders. In J. Clarke & P. Wilson (Eds.), Forensic Psychology in Practice: A Practitioner’s Handbook (pp. 172-189). Palgrave Macmillan.

Wilson, T. D., & Hodges, S. D. (1992). Attitudes as temporary constructions. The construction of social judgments, 10, 37-65.

Wilson, T. D., Lisle, D. J., & Kraft, D. (1990). Effects of self-reflection on attitudes and consumer decisions. Advances in Consumer Research, 17, 79-85.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Social media publication

! Please note that this study will include a consideration of scenarios of sexual assault.

If you are collecting SONA credits, this would be a great opportunity to add to your overall credit!

Thank you!

Appendix 2. Case vignettes

CASE VIGNETTE 1 – Male offender, male victim

A 29-year-old man, Tom was on a bus on his way to visit family. Half way through the journey an unknown male sat next to him and raised the armrest between their seats. The unnamed man began to touch him sexually. He immediately got up, moved to another empty seat and proceeded to report the man. CCTV was in place on the bus and confirming the allegations, the man was arrested. He later received a prison sentence of 10 weeks.

CASE VIGNETTE 2 – Male offender, female victim

Tania, 28 was on a business trip to several other company offices around the country. On her flight back home, as soon as she sat down noticed another passenger, a man, occupying the seat next to her. He sat down next to her and as soon as the plane took off he unbuckled her seat belt and began to touch her sexually. Upon arrival, she reported the incident to the flight attendants and the police. An eyewitness confirmed the allegations and the man was arrested, receiving a prison sentence of 10 weeks.

Original media story: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-elections/donald-trump-sexual-assault-groping-allegations-anthony-gilberthorpe-jessica-leeds-a7362761.html

The names were change to random names in order to anonymise the perpetrator and the victims. The amount of jail time the perpetrator received is not mentioned. The details are not revealed and neither is the weapon no minimise distress where possible.

Appendix 3. The Perceptions of Sex Offenders Scale (PSO) and Permission

Appendix 4 – The Attitudes Towards Sex Offenders Scale (ATS-21) and Permission

Appendix 5 – Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (BIDR)

Appendix 6 – Participant Information Sheet

Participant Information Sheet

Title of Project: Psychology undergraduate attitudes towards male sex offenders: The impact of the victim’s gender

Invitation

I would like to invite you to take part in my research project. Before you decide whether to take part it is important that you understand why the research is being done and what it will involve. Please take time to read this carefully and ask the researcher if you have any questions.

What is the purpose of the study?

This study aims to explore the views that students have towards sex offenders and their post-conviction future (released, reintegrated into community etc.) as well as their thoughts on how harsh should they be punished for their criminal actions. This study is important as most students are on a path to become professional in the field of psychology and are very likely to be in some way involved in the treatment and rehabilitation of sex offenders but also perhaps helping them reintegrate into community. The students are asked to present their views upon two fictional cases and with the cases in mind, to rate their thoughts about the sex offender on two scales.

Why have I been invited to take part?

You have received this invitation because you are a current student at the university studying Clinical, Counselling or Forensic Psychology. I am hoping to recruit at least 120 participants for this study.

Do I have to take part?

No. It is up to you to decide whether or not you want to take part in this study. Please take your time to decide and please give this decision a thorough think before. If you take part, but you wish to have your data withdrawn please contact the researcher with your participant number and your data will then not be used. If you do decide to take part, you will be asked to sign an electronic consent form.

What will happen to me if I agree to take part?

If you agree to take part, you will be asked to complete an online task. This requires you to answer a few online questionnaires with your opinion on a fictional person in different settings. The online task can be completed in the comfort of your own home and it should not take any longer than 15 minutes.

Are there any disadvantages or risks to taking part?

It is important that you understand that during this study you will be exposed to two scenarios of sexual assault and it is required of you to self-asses what potential impact this may have on you, therefore deciding whether you want to take part or not. There are no foreseen risks in taking part in this study and even though the study is based on a sensitive topic (sexual assault), this should not be anything you have never been exposed to through media, television or other news sources. Although, you will have to think about how you feel towards sex offenders and for some people this might be upsetting. If you do feel that any distress was caused to you by any part of this study, you are free to discontinue the completion at any point and contact any of the support services provided to you here or at the end of the online task.

Will the information I give stay confidential?

Everything you say/report is confidential unless you tell us something that indicates that you or someone else is at risk of harm. I would discuss this with you before telling anyone else. The information you give may be used for a research report, but it will not be possible to identify you from our research report or any other dissemination activities. Personal identifiable information (e.g. name and contact details) will not be collected as part of this study. Other demographic data (e.g. gender, age and course) will be securely stored and kept for up to 3 months after the project ends in 4th of May 2017 and then securely disposed of. The research data (e.g. questionnaire responses) will be securely stored and may be used for further research purposes.

What will happen to the results of the research study?

This research is being carried out as part of my independent study at the University of Worcester. The findings of this study will be reported as part of my dissertation and may also be published in academic journals or at conferences.

If you wish to receive a summary of the research findings, please contact the researcher.

Who is organising the research?

What happens next?

Please keep this information sheet. If you do decide to take part, please contact the researcher using the details below.

Thank you for taking the time to read this information

If you decide to take part of you have any questions, concerns or complaints about this study please contact one of the research team using the details below.

If you need any help or are experiencing distress in regards to this study and would like to speak with someone about this please use the following links: https://www.selfhelpservices.org.uk/directory-of-services/

http://www.worc.ac.uk/counselling/

Appendix 7 – Consent form

Appendix 8 – Online Debrief Form

Online debrief

Your generosity and willingness to participate in this study are greatly appreciated. The questionnaires you have answered included two measures of attitudes towards sex offenders and one measure of desirable responding.

Sometimes people find the subject matter of this task and questionnaires disturbing. If any part of this study led you to feel distressed and you would like to speak to someone about how you feel, please check the following link which will take you to Self Help Services web page. Here you can find useful information about local services and groups that may help you.

https://www.selfhelpservices.org.uk/directory-of-services/

Thank you again for taking part!

Appendix 9 – Data Authenticity Form

Appendix 10 – Ethical Approval Code

Appendix 11 – SPSS Output – Assumptions of Normality

| Tests of Normality | ||||||

| Kolmogorov-Smirnova | Shapiro-Wilk | |||||

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Statistic | df | Sig. | |

| PSO Male victim – S&M | .090 | 124 | .016 | .981 | 124 | .080 |

| PSO Female victim – S&M | .060 | 124 | .200* | .986 | 124 | .221 |

| PSO Male victim – SE | .062 | 124 | .200* | .979 | 124 | .053 |

| PSO Female victim – SE | .077 | 124 | .070 | .979 | 124 | .049 |

| PSO Male victim – RP | .111 | 124 | .001 | .965 | 124 | .003 |

| PSO Female victim – RP | .102 | 124 | .003 | .972 | 124 | .011 |

| ATS Male victim – T | .076 | 124 | .075 | .984 | 124 | .160 |

| ATS Female victim – T | .103 | 124 | .003 | .968 | 124 | .005 |

| ATS Male victim – I | .068 | 124 | .200* | .990 | 124 | .536 |

| ATS Male victim – SD | .077 | 124 | .069 | .986 | 124 | .246 |

| ATS Female victim – I | .074 | 124 | .088 | .987 | 124 | .288 |

| ATS Female victim – SD | .083 | 124 | .036 | .989 | 124 | .417 |

Appendix 12 – PSO Findings

| Descriptive Statistics for PSO subscales | ||

| Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| PSO Male victim – S&M | 31.78 | 9.23 |

| PSO Female victim – S&M | 31.98 | 10.08 |

| PSO Male victim – SE | 13.91 | 4.43 |

| PSO Female victim – SE | 13.50 | 4.41 |

| PSO Male victim – RP | 23.41 | 3.90 |

| PSO Female victim – RP | 23.04 | 4.04 |

Appendix 13 – ATS-21 Findings

| Descriptive Statistics for ATS-21 subscales | ||

| Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| ATS Male victim – T | 16.74 | 4.84 |

| ATS Female victim – T | 16.46 | 5.15 |

| ATS Male victim – I | 24.30 | 4.40 |

| ATS Female victim – I | 23.52 | 4.88 |

| ATS Male victim – SD | 20.88 | 3.93 |

| ATS Female victim – SD | 20.93 | 4.47 |

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Psychology"

Psychology is the study of human behaviour and the mind, taking into account external factors, experiences, social influences and other factors. Psychologists set out to understand the mind of humans, exploring how different factors can contribute to behaviour, thoughts, and feelings.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: