An Investigation into Coping Methods That Maintain Resilience and Wellbeing after Stressful Life Events

Info: 7914 words (32 pages) Dissertation

Published: 25th Feb 2022

Tagged: PsychologyMental Health

Abstract

Stressful life events are able to contribute to a variety of different mental illnesses and is closely associated with resilience and different coping strategies used to maintain wellbeing. However, the nature of these relationships that resilience has to spirituality and substance use is still unexplored. The current study therefore aimed to explore the relationships between stressful life events, spirituality, substance use, resilience and wellbeing. In particular, an examination of the mediating effecting known to resilience between stress and wellbeing will occur as well as models for moderated mediation with resilience as a mediator and spirituality and substance use acting as moderators. 33 males and 69 females aged between 18 and 60 years old (M = 29.41, SD = 11.26) completed a pack of questionnaires consisting measuring the demographics and the study variables. A majority of the results show non-significant correlations except for significant links between stressful life events and polysubstance use as well as resilience and wellbeing. The mediation model was not confirmed as there was no mediation effect resilience. Equally, the moderate mediation model between the variables showed no interaction or effect of significance. The findings show support and disagreement with the previous research. Implications, limitations and future recommendations are also discussed.

Keywords: stressful life events, resilience, substance use, spirituality, wellbeing

Introduction

Resilience can play a crucial role within psychology and aid in understanding how people recover from traumatic events. Studies have noted that a well-known trigger for resilience processes are stressful life events (SLEs) (Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli & Vlahov, 2007). As a response, coping strategies assist with stress management (Kimhi & Eshel, 2015), yet not all coping habits are considered a protective factor for resilience. To elaborate further, it is still unknown which coping habits moderate the stress levels and assist the resilience processes to maintain wellbeing. In attempts to bridge this gap in knowledge, this present study will seek to explore the relationships between two common coping habits – spirituality and substance use their link to SLEs and maintaining resilience and wellbeing.

Resilience

Stressful life events are capable of affecting all ages, genders and cultures in a variety of risk-taking behaviours, increased substance usage and symptoms of anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, hopelessness as well as suicidal tendencies (Aune & Stiles, 2009; Baldwin, Brown, Wayment, Nez & Brelsford, 2011; Biafora, Warheit, Vega & Gil, 1994; Gallagher III, Jones & Pardes, 2016; Jaiswal, Faye, Gore, Shah & Kamath, 2015; Lim, Lim, Gwee, Nyunt, Kumar & Ng, 2015; Phillips, Carroll & Der, 2015; Skrove, Romundstad & Indredavik, 2013; Staton-Tindall, Duvall, Stevens-Watkins & Oser, 2013). Although, it has also been documented that SLEs can also trigger positive psycho-social adjustments which can predict resilience and lead to post-traumatic growth (PTG) (Arpawong, Sussman, Milam, Unger, Land, Sun & Rohrbach, 2015; Bonanno, et al., 2007; Rodriguez-Rey, Palacios, Alonso-Tapia, Perez, Alvarez, Coca…Belda, 2017). Moreover, further research continues to understand and explore how resilience can improve the efficacy of existing intervention programs (Steinhardt & Dolbier, 2008).

However, operationalising resilience does have its complexities since it is a multilevel construct with numerous aspects (Kimhi & Eshel, 2015). While some suggest resilience is a process that allows one to bounce back from adversity (Kapikiran & Kapikiran, 2016), others have consider it an outcome (Cowden & Meyer-Weitz, 2016) or a personality trait one shows (Rodriguez-Rey et al., 2017). An alternative perspective is to perceive resilience as a state of mind that allows individuals to readapt and proceed with their lives despite suffering from adversities (Kimhi & Eshel, 2015). In other words, resilience can be defined as the protective mind frame one adopts to participate in the continuous struggle between traumatic stress following an SLE and one’s own mental strength to resist and endure (Kimhi & Eshel, 2015). Within this perspective, it is noted how the resilient state of mind includes coping processes that end up building protective traits within the person and assist with their post-traumatic growth. One of the most effective ways to measure resilience is to utilise self-report instruments like the Brief Resilience Scale (Smith, Dalen, Wiggins, Tooley, Christopher & Bernard, 2008). Reason being, they can provide observations into an individual’s perceived level of resilience (Kimhi & Eshel, 2015).

In terms of research, there has been continuous support for resilience acting as a buffer for the stress from traumatic life events. To illustrate, one study by Shi, Wang, Bian and Wang (2015) sought to examine the mediating role of resilience between stressors that predicted life satisfaction through hierarchical linear regression models. A cross-sectional study was performed with self-report questionnaires measuring the perceived stress, resilience and satisfaction with life by Chinese medical students. From their sample of 2925 valid respondents, a positive correlation was seen between resilience and satisfaction with life (r = 0.53, P

Another example sees how resilience is related to the happiness of an individual. For instance, one proposal states how forgiveness can predict resilience in people which in turn predicts overall happiness (Jaufalaily & Himam, 2017). The examiners recruited 203 undergraduate students that completed a self-report questionnaire packs assessing forgiveness, happiness and resilience. Results from their mediation analyses highlighted significant predictions with forgiveness predicting resilience (t = 5.174, p = .00

Resilience and Spirituality

The next step in resilience research is garnering a greater understanding on the protective factors that exist. If resilience can reduce the impact of stress and maintain ones well-being, exploring what type of protective factors and which coping strategies are linked to the resilience process should remain a top priority. O’Grady, Orton, White, Snyder’s article (2016) supports this notion but goes a step further by proposing that incorporating concepts of spirituality within the resilience framework is necessary for greater understandings. While the definition of what spirituality is differs from researcher to researcher, this study will adopt the following modified perspective: A personal transcendent experience, sharing a connection to everything, nothingness and one’s self with God or through a divine universal higher spirit that leads to the construction of an existential meaning to life (Underwood & Teresi, 2002; Tong, 2017). Such an experience is said to occur when an individual is affiliated with an organised religion (Van Cappellen, Toth-Gauthier, Saroglou & Fredrickson, 2016), practicing self-imposed mantras (Krok, 2008), or even through interactions with nature such as gardening. (Trigwell; Unruh & Hutchinson, 2011). With this in mind, psychologists have resorted to self-report measurements such as the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES) (Underwood & Teresi, 2002) to understand the level of spiritual experiences felt within a day.

Following an SLE, coping through spirituality in the form of ancient practices and modern philosophies has continued to be a source of PTG and psycho-spiritual transformation (Bray, 2010). A sense of self-awareness is said to be facilitated through self-reflection of one’s feelings, thoughts and behaviours and produce insights of enlightenment that boost ones self-esteem and resilience (Joshanloo & Daemi, 2015; Krok, 2008; Cowden & Meyer-Weitz, 2016; Smith, Webber, DeFrain, 2013). Daily experiences with spirituality according to Tong (2017) can show strong associations with transcendental positive emotions such as compassion, humility, gratitude and love. Subsequently, many have noted that spiritual wellbeing can contribute towards maintaining a resilient state of mind (Yoon, Chang, Clawson, Knoll, Aydin, Barsigian & Hughes, 2015; Smith, Webber & DeFrain, 2013). From the numerous amount of support that spirituality has for its health benefits, it can be suggested that spirituality is a potential protective factor for resilience (Womble, Labbe & Cochran, 2013). However, it is unknown to our knowledge if spirituality has been tested as a moderator between stress and resilience.

Resilience and Substance use

Following an SLE, another popular coping strategy that is prevalent across all ages, genders and cultures is substance use. Many consider this strategy to be a maladaptive form of coping behaviour due to its capacity to alter a person’s state of mind over prolonged use (Staton-Tindall, et al., 2013; Van Gundy, Howerton-Orcutt & Mills, 2015; Unger, Li, Anderson Johnson, Gong, Chen, Li, … Lo, 2001). Similarly, it has been recognised that the consumption of multiple different drugs is also capable of predicting lower levels of wellbeing (Allen & Holder, 2004). To further support this link, Rudzinski, McDonough, Gartner & Strike (2017) observed how the efficacy of resilience based intervention programs decreased when a patient’s habit of substance use increased. On the other hand, researching into the motivating factors for substance use and how resilience processes impact that link. The nature of that relationship was explored by Fadardi, Azad & Nemati (2010) significantly noted how resilience is correlated to reducing the motivating factors for regular substance use. Likewise, it has also been suggested that focusing on specific protective factors of resilience that are related to substance use could increase the efficacy of resilience intervention (Hodder, Freund, Bowman, Wolfenden, Gillham, Dray & Wiggers, 2016).

From these results, it can be suggested that resilience and substance use possesses a relationship that is possibly bidirectional. Nevertheless, the correlations between substance use and resilience require additional investigation because substance use is known for being a chosen coping mechanism. Additionally, previous studies have yet to explore if substance use plays a moderating role between SLEs and resilience.

In summary, SLEs trigger resilience processes that assist recovery from traumatic moments in life. To date there are two coping habits that can be considered to be the first option of many people under stress: spirituality or substance use. The current available research suggests that spirituality is a potential protective factor with a bigger role to play within the resilience framework. On the other hand, substance use and its relationship with resilience still requires further investigation. Finally, there is no research exploring whether the mediation effect of resilience is moderated by coping strategies.

Aims

The present study seeks to explore the associations between SLEs, resilience, spirituality, substance and wellbeing. Based off the research, resilience’s role as a mediator for SLEs and wellbeing will be examined. Additionally, spirituality and substance use will be operationalized as moderators in the relationship between SLEs and resilience. Which in turn shall be looked at further within a moderated mediation model with the five variables.

In this research, the Independent variable (IV) is SLEs, the dependent variable (DV) is wellbeing and the mediator will be resilience. The moderator variables will be spirituality and substance use. The design itself will be cross-sectional model consisting of an online questionnaire pack created through survey monkey.

Hypotheses

H1 – There will be positive correlations seen between the five study variables.

H2 – Resilience has a mediating effect on the relationship between SLEs and wellbeing

H3 – Spirituality will moderate the mediation effect given by resilience between SLEs and wellbeing.

H4 – Substance use will moderate the mediation effect given by resilience between SLEs and wellbeing.

Method

Participants

The sample contained of 102 applicants (69 females and 33 males), aged between 18 and 60 years (M = 29.41, SD = 11.26). One third of the sample (38.2%) was reported to be single, with the nearly half the sample reporting to be with a partnership of the sort (insert values). The ethnicities of the participants were scattered across different cultures, with a large part of the sample being of a Caucasian background (43.1%). Almost 70% of participants were not studying, with 25.5% being full-time students. Over half the sample was employed to some degree, with full time showing the highest representation with 47.1%. Lastly, 40% of the sample had finished tertiary education while the rest finished in high school or tafe.

Materials

Volunteers had to complete the sequence of self-report questionnaires online via SurveyMonkey (http://www.surveymonkey.com). Consisting of six measures, totalling 103 items, the questionnaire package took approximately 15 minutes to finish. The six measures that were utilised within the study are:

Demographic data

Non-identifiable questions given to the participants addressing demographics such as age, gender, relationship status, ethnic background, occupation status, and educational level.

Stressful Life Events

The Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) by Holmes and Rahe (1967) is a 43-item instrument designed to measure the stressful events in the last year. The events are given a “life changing unit” value which reflects the relative amount of stress the event causes. Gerst, Grant, Yager & Sweetwood (1978) tested the reliability of the SRRS, and found that rank ordering remained extremely consistent both for healthy adults (r = 0.89 – 0.96) and patients (r= 0.70 to 0.91)

Spirituality

The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES) by Underwood and Teresi (2002) is a modified Likert scale with 16-items intended to measure participant’s daily spiritual experiences. Respondents indicate the extent to which particular items reflect their own experiences. For example; on a six-point scale ranging from 6 (many times a day) to 1 (never or almost never), I experience a connection to all of life. Underwood and Teresi (2002) conducted tests of internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha, acquiring reliabilities of 0.94 and 0.95.

Drug Use Survey

The Drug Use Survey is a self-designed Likert scale consisting of 16-items regarding the participant’s current usage with a variety of different substances. The response categories for the measure are every day, approx. once a week, approx. once a month, one or twice a year, not currently using and never used. Scoring ranged from 0 for never used to 6 for every day. A polysubstance use variable will also be calculated from the number of participants who answer 4 (approx. once a month) and above on the survey.

Resilience

The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS; Smith, Dalen, Wiggins, Tooley, Christopher & Bernard, 2008) is a 6-item instrument intended to assess an individual’s ability to bounce back from adversities. Items 1, 3, 5 are positively worded while items 2, 4 and 6 are negatively worded. The BRS is scored by reverse coding items 2, 4, 6 and finding the mean of the six items. Respondent statements on the scale were: 1= strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree. Smith and colleagues (2008) tested the shorter Brief Resilience scale within their study and found the Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .80-.91 across their four samples.

Wellbeing

The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS; Clarke, Friede, Putz, Ashdown, Martin, Blake,…Stewart-Brown, 2011) is a measure of 14 positively worded items, with five response categories, for assessing a population’s mental wellbeing. Clarke, et al., (2011) demonstrated strong internal consistency and a high Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 (95% CI (0.85-0.88), n = 1517)

Procedure

Upon approval from The Cairnmillar Institute Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC), participants were drafted from the population using the snowball technique as well as online social media groups. Volunteers were given link to online questionnaire pack through SurveyMonkey (HTTP://www.surveymonkey.com). Prior to commencing the survey, participants had to read through the plain language statement which covered the general purpose of the study in simple terms and notified participants of their right for confidentiality, anonymity, and the right to withdraw at any moment. Consent was assumed with survey completion.

Results

Data screening for missing values, outliers and assumption criteria as well as the analyses were conducted through Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 22. Analysis of incomplete scales led to 15 cases being excluded (list-wise deletion), leaving a valid sample of 102. As seen in Table 1, all scales displayed acceptable internal reliability except the Social readjustment rating scale.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for the sample are also displayed within Table 1. The scales used to measure SLEs, spirituality, substance use, resilience and wellbeing all showcased scores within the medium levels. Polysubstance use scores were around the lower level of the scale.

Correlations

Pearson’s correlations were calculated to assess bivariate associations between SLEs, spirituality, substance use, resilience, wellbeing as well as age and gender. Shown in Table 2, the relationships varied between negative and positive with many being non-significant. Notably, resilience showed the most promising results with statistically significant associations with wellbeing, highlighting how the more resilient an individual reported to be, the greater their wellbeing. On the other hand, there is a small, significant correlation between those with higher levels of stress and those with greater levels of polysubstance use. Furthermore, a small significant correlation existed between the age of the participants and higher levels of spirituality. Lastly, the gender of the participants shared a medium correlation of significance with higher levels of polysubstance use and higher levels of resilience.

Mediator and Moderated Mediation Analyses

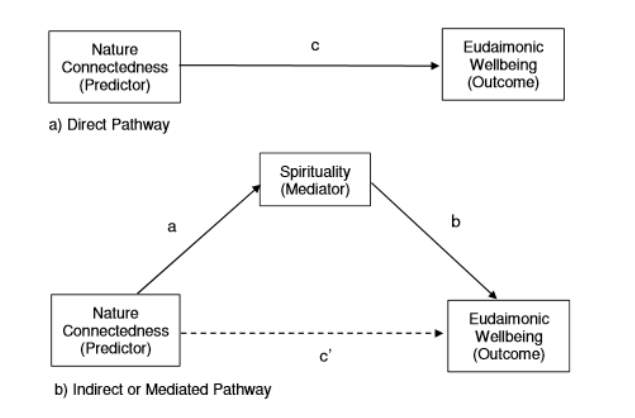

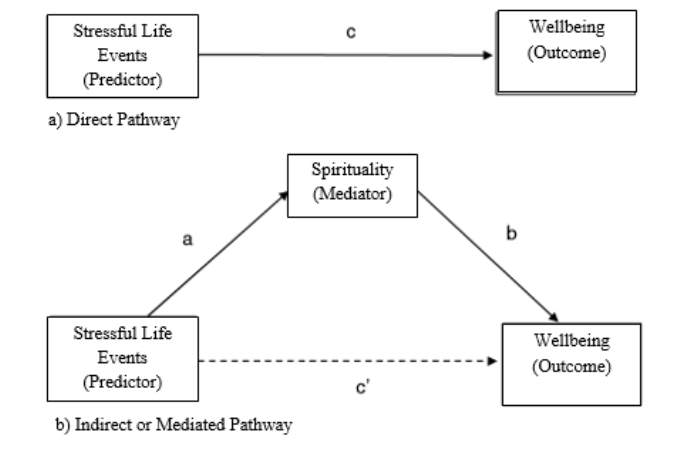

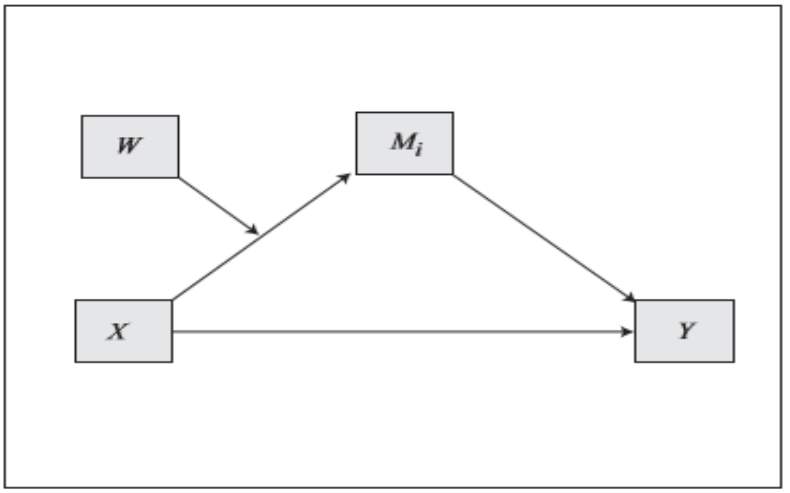

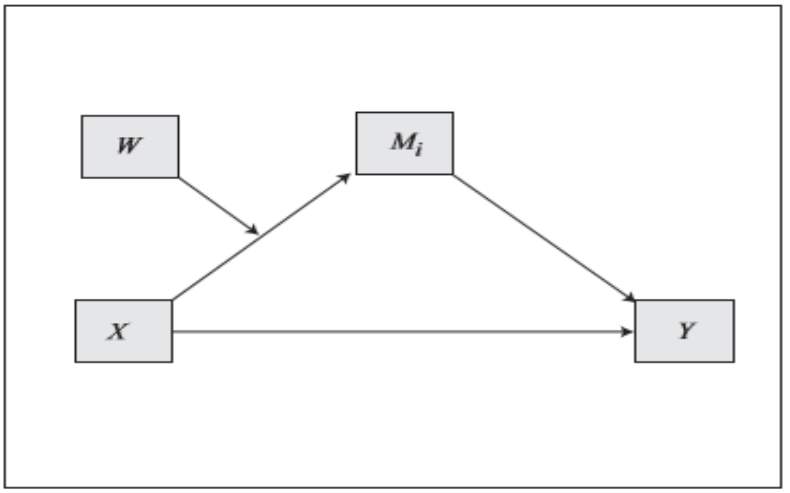

To test the hypotheses, the PROCESS script by Preacher and Hayes (5,000 bootstraps, 95% confidence interval) was conducted through SPSS 22. The mediation model used within this study focused on the mediating role of resilience between stress and wellbeing (Figure 1.). The first moderated mediation model (Figure 2.) has spirituality acting as the moderator for the mediation model mentioned beforehand. The second moderated mediation model (Figure 3.) has polysubstance use acting as the moderator in place of spirituality. Displayed in Table 3, the results for the interaction between SLEs and Spirituality was not significant, indicating that little to no moderated mediation had occurred. SLEs and substance use also showed no significant interaction result. Additionally, there does not appear to be any form of moderated mediation present as the confidence levels of both spirituality and substance use passed through the value of 0.

Discussion

Our purpose with this study is to examine the relationships between SLEs, resilience, spirituality, substance use and wellbeing. Contrary to previous findings, we found that our hypothesis was only partially supported through positive correlations between SLEs and polysubstance use as well as resilience and wellbeing. Additionally, we hypothesised that a mediation model with SLEs, resilience and wellbeing would be supported. However, our findings from the data showed that this prediction is not supported. Likewise, the moderated mediation models with SLEs, resilience, substance use, spirituality and wellbeing that was proposed by the researchers was also not supported by the results.

Implications

Our findings confirm that SLEs are significantly related with polysubstance use, a replication of past findings regarding the popularity of substance use as a coping strategy (e.g., Biafora et al., 2004; Staton-Tindall, et al., 2013; Unger et al., 2001). Still, our results suggest that higher levels of stress might also influence the frequency of polysubstance use. While there is a small positive association that was observed, it may not be enough evidence to say that this relationship exists within the population. Nonetheless, it could be speculated that the general public are becoming more inclined towards using the different amount of drugs that are becoming readily accessible (Allen & Holder, 2004). Moreover, self-medication with more than 2 substances is also becoming increasingly popular and common as a coping strategy (Allen & Holder, 2004). Given the growing concern over the way people use substances during stressful times, this finding may be of relevance to the frequency of multiple substances being used at that time. It seems that even now in this present day, substance use continues to be a dominant form of coping.

The results also indicated that a significant association existed between resilience and wellbeing, another finding that confirms previous findings regarding resilience’s link to the wellbeing of an individual (e.g., Shi, et al., 2015; Jaufalaily & Himam, 2017). Based off this outcome, those who are resilient might have greater levels of wellbeing. There is also enough evidence for the correlation observed to exist within the general population. One possible speculation for this current association could be that nowadays with the increasing library of knowledge that becomes accessible to the general public, improving one’s health by building their resilience could more possible than before (O’Grady et al., 2016; Womble et al., 2013 ). Just as it was noted by Steinhardt & Dolbier (2008), understanding the impact that resilience has during stressful times is also completely relevant to today’s current intervention programs aimed at utilising the resilience framework. Having an awareness of the possible protective factors and coping strategies that people will resort too during stressful times will provide additional support in the development of resilience based intervention programs (O’Grady, et al., 2016).

Secondary findings have revealed another significant relationship between age and spirituality. Previous studies have noted how the elderly tend to be more spiritual than younger generations (Unruh & Hutchinson, 2011) yet it does not appear to be the case here. It seems that those who reported themselves to be under the age of 30 had also reported having higher levels of spiritual experience than their older counterparts. Such a contrast in findings however could be partially explained by the overrepresentation of those under the age of 30 (nearly 70% of participants) seen within our study. Our results do reflect Smith, Webber & DeFrain’s (2013) study, highlighting the associations between the youth and their level of spiritual experience. Unfortunately, given our small effect size, there is not enough evidence to support this link existing within the general population. But it does lead us to speculate whether or not age has a role in the level of spirituality as additional research continues to explore these concepts further.

The other secondary finding is that both resilience and polysubstance use are positively connected with gender. This revelation also corresponds with prior research findings regarding gender differences in the perceived level of resilience and in the level of substance usage (previous research). Within our study, it was found that more males had higher levels of resilience even though females had a larger representation. Moreover, given the overrepresentation of female participants, there are more reports of lower levels of resilience. Yet still, given the medium effect size, it maybe representative within the current population. The correlation seen in our sample raises question over what factors are relevant to understanding the gender differences among resilience. It could be speculated however that males are more resilient due to the biological nature of masculinity as well as a preference for substance use as a coping strategy. Whereas previous research has well noted that females use spirituality as a source of strength as well as substance use (e.g., Staton-Tindall. Et al., 2013). Nevertheless, this study could be of relevance for future studies on gender differences.

While the theory behind the associations between SLEs, spirituality, substance use, resilience and wellbeing appear to indicate potential links among them, our findings showed little support for their connection. SLEs also displayed insignificant relations between spirituality, resilience and well-being, though this could primarily be due to research design (discussed further in limitations). Spirituality has been said to play a role in the buffering of stress and the promotion of resilience and well-being, but our results were insignificant. It may be that spirituality has a weaker association to the study variables than previously considered, though this is merely speculation.

The mediation and moderated mediation models (Figures 1 & 2) that was proposed by the researchers was not supported. Resilience within our study had caused no mediation effect between SLEs and Wellbeing. Likewise, the results also provide quantitative support that both spirituality and substance have no interaction on the mediation effect of resilience between SLEs and wellbeing. These findings may be explained in part due to the experimental design (discussed in limitations).

Limitations and future directions

The results from the present study and related limitations identify multiple pathways for future experiments. Judging from many insignificant findings, the current research possesses a few limitations that need to be addressed. Primarily, the small sample size used within our research has been a great limitation is research was greatly limited by its small sample size and therefore unable to acquire the minimum number of participants for a significant effect size. Although this research aimed to sample the general population, sample characteristics indicate that participants over the age of 25, females, Caucasians, full time workers, participants who weren’t studying and those who had completed university had been overrepresented. Therefore, these findings might not be applicable to the wider community. Next, using the snowball sampling technique as well as advertising within various online social media groups related to the study variables has exposed the sample to false data. This also could further be caused by individuals taking advantage of the anonymous status given by the internet to skew results by falsely reporting in the research. With regards to expanding the sample size, data collection may have occurred at an earlier date with additional advertising done for greater exposure to potential participants. An increase in participation could have also occurred if the investigator and dedicated more time to contact people of all populations to have a better represented sample. Including spreading advertisements across several campuses, social groups, related organisations, work places and an increased online presence on social media. Preferably, the amount of applicants should have been distributed across all demographic variables; age, gender, relationship status, ethnicity, as well as occupation status and education level evenly. Given the current results and level of participation, the sample size represents a very narrow range of the general population.

Our research design favoured a cross sectional approach to measure the variables due to time constraints of having to complete the dissertation by the end of 2018. The idea was that having a simple comparison study conducted over a short time would present a decent foundation to exploring any possible relationships between the variables. Unfortunately, the research is limited by the amount of time to collect data, further decreasing the chances of observing a significant association or mediation effect between the variables. Generally, previous research involving these variables are conducted as longitudinal studies to compare the changes at different points. The impact of stressful life events on wellbeing for example could be better examined if the research collected data every month over 12 months. Measures of spirituality, substance use and resilience would have all benefitted further if the results were collected every month over a period of 12 months as well. This would show whether there is an increased or decreased in the levels of SLEs, spirituality, substance, resilience as well as wellbeing over that time. Such data would be more useful to understanding the coping strategies. Furthermore, the scales used were reputable yet outdated. A more significant outcome could have been provided if future researchers use more newer and reliable scales such as the COPE Inventory (previous research). It could facilitate a better understanding on the type of coping strategies used by the participants to maintain their resilience and wellbeing.

Conclusion

The present research offers minute evidence on the positive relationships between stressful life events, substance use, spirituality, resilience, and wellbeing. It has confirmed previous findings of wellbeing having strong significant relations to maintaining wellbeing as well as significant correlations between SLEs and substance. Contrary to past research, resilience had no mediation effect between SLEs and wellbeing. After testing two moderated mediation models, spirituality and substance use were found to have no significant interaction effects on moderating resilience as it mediates SLEs and wellbeing. Understanding the connections between SLEs, spirituality and substance use is necessary for exploring how coping habits assist resilience and wellbeing within different populations. As such, it seems that the information presented within this report can assist future research designs by acting as a foundation for subsequent studies.

References

Allen, J., & Holder, M. D. (2014). Marijuana use and well-being in university students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(2), 301-321. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9423-1

Arpawong, T. E., Sussman, S., Milam , J. E., Unger, J. B., Land, H., Sun, P., & Rohrbach, L. A. (2015). Post-traumatic growth, stressful life events, and relationships with substance use behaviors among alternative high school students: A prospective study. Psychology & Health, 30(4), 475-494. doi:10.1080/08870446.2014.979171

Aune, T., & Stiles, T. C. (2009). The effects of depression and stressful life events on the development and maintenance of syndromal social anxiety: Sex and Age Differences. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38(4), 501-512. doi:10.1080/15374410902976304

Baldwin, J. A., Brown, B. G., Wayment, H. A., Antone-Nez, R., & Brelsford, K. M. (2011). Culture and context: Buffering the relationship between stressful life events and risky behaviors in American Indian youth. Substance Use & Misuse, 46, 1380-1394. doi:10.3109/10826084.2011.592432

Biafora Jr., F. A., Warheit, G. J., Vega, W. A., & Gil, A. G. (1994). Stressful life events and changes in substance use among a multiracial/ethinic sample of adolescent boys. Journal of Community Psychology, 22, 296-311.

Bonanno, G. A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A. & Vlahov, D. (2007). What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life Stress. Journal of Counselling and Clinical Psychology, 75(5), 671-682.

Bray, P. (2010). A broader framework for exploring the influence of spiritual experience in the wake of stressful life events: examining connections between posttraumatic growth and psycho-spiritual transformation. Mental Health, Religion & Culture , 13(3), 293-308.

Clarke, A., Friede, T., Putz, R., Ashdown, J., Martin, S., Blake, A., … Stewart-Brown, S. (2011). Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Validated for teenage school students in England and Scotland. A mixed methods assessment . BMC Public Health ,11(487), 1-9.

Cowden, R. G., & Meyer-Weitz, A. (2016). Self-reflection and self-insight predict resilience and stress in competitive tennis. Social Behavior and Personality, 44(7), 1133-1150. doi:10.2224/sbp.2016.44.7.1133

Gallagher III, B. J., Jones, B. J., & Pardes, M. (2016). Stressful Life Events, Social Class and Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses, 10(2), 101-108. doi:10.3371/1935-1232-10.2.101

Gerst, M. S., Grant, I., Yager, J., & Sweetwood, H. (1978). The reilability of the Social Readjustment Rating Scale: Moderate and long-term stability. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 22(6), 519-523.

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(2), 213-221.

Hodder, R. K., Freund, M., Bowman, J., Wolfenden, L., Gillham, K., Dray, J. & Wiggers, J. (2016). Association between adolescent tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug use and individual and environmental resilience protective factors. British Medical Journal, 6, 1-11.

Jaiswal, S. V., Faye, A. D., Gore, S. P., Shah, H. R. & Kamath, R. M. (2016). Stressful life events, hopelessness, and suicidal intent in patients admitted with attempted suicide in a tertiary care general hospital. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine, 62(2), 102-104.

Joshanloo, M., & Daemi, F. (2015). Self-esteem mediates the relationship between spirituality and subjective well-being in Iran. International Journal of Psychology, 50(2), 115-120. doi:10.1002/ijop.12061

Kapikiran, S. & Acun-Kapikiran, N. (2016). Optimism and psychological resilience in relation to depressive symptoms in university students: Examining the mediating role of self-esteem. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16(6), 2087-2110.

Kimhi, S., & Eshel, Y. (2015). The missing link in resilience research. Psychological Inquiry, 26, 181-186. doi:10.1080/1047840X.2014.1002378

Krok, D. (2008). The role of spirituality in coping: Examining the relationships between spiritual dimensions and coping styles. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 11(7), 643-653. doi:10.1080/13674670801930429

Lim, M. L., Lim, D., Gwee, X., Nyunt, M. S. Z., Kumar, R. & Ng, T. P. (2015). Resilience, stressful life events, and depressive symptomatology among older Chinese adults. Agingand Mental Health, 19(11), 1005-1014.

O’Grady, K. A., Orton, J. D., White, K., & Snyder, N. (2016). A way forward for spirituality, resilience, and international social science. Journal of Psychology & Theology, 44(2), 166-172. doi:po0091-6471/410-730

Phillips, A. C., Carroll, D., & Der, G. (2015). Negative life events and symptoms of depression and anxiety: stress causation and/or stress generation . Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 28(4), 357-371. doi:10.1080/10615806.2015.1005078

Rodriguez-Rey, R., Palacios, A., Alonso-Tapia, J., Perez, E., Alvarez, E., Coca, A., … Belda, S. (2017). Posttraumatic growth in pediatric intensive care personnel: Dependence on resilience and coping strategies. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice,and Policy, 9(4), 407-415.

Rudzinski, K., McDonough, P., Gartner, R. & Strike, C. (2017). Is there room for resilience? A scoping review and critique of substance use literature and its utilization of the concept of resilience. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention and Policy, 12(41), 1-35.

Shi, M., Wang, X., Bian, Y. & Wang, L. (2015). The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between stress and life-satisfaction among Chinese medical students: a cross sectional study. BioMed Central Medical Education, 15(16), 1-7.

Skrove, M., Romundstad, P. & Indredavik, M. S. (2013). Resilience, lifestyle and symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescence: The Young-HUNT study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48, 407-416.

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Tooley, K., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194-200.

Smith, L., Webber, R. & DeFrain, J. (2013). Spirituality well-being and its relationship to resilience in young people: A mixed methods case study. SAGE Open, 1-16. doi:10.1177/2158244013485582

Staton-Tindall, M., Duvall, J., Stevens-Watkins, D., & Oser, C. B. (2013). The roles of spirituality in the relationship between traumatic life events, mental health, and drug use among African American women from one southern state. Susbtance Use & Misuse, 48, 1246-1257. doi:10.3109/10826084.2013.799023

Steinhardt, M. & Dolbier, C. (2008). Evaluation of a resilience intervention to enhance coping strategies and protective factors and decrease symptomatology. Journal of American College Health, 56(4), 445-453.

Tong, E. M. (2017). Spirituality and the temporal dynamics of transcendental positive emotions. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 9(1), 70-81. doi:10.1037/rel0000061

Trigwell, J. L. (2014). Nature connectedness and eudaimonic wellbeing: Spirituality as a potential mediator. Ecopsychology, 6(4). doi.org/10.1089/eco.2014.0025

Underwood, L. G., & Teresi, J. A. (2002). The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24(1), 22-33.

Unger, J. B., Li, Y., Johnson, C., Gong, J., Chen, X., Li, C., . . . Lo, A. T. (2001). Stressful life events among adolescents in Wuhan, China: Associations with smoking, alcohol use, and depressive symptoms. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 8(1), 1-18.

Unruh, A., & Hutchinson, S. (2011). Embedded spirituality: Gardening in daily life and stressful life experiences. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 25, 567-574. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00865.x

Van Cappellen, P., Toth-Gauthier, M., Saroglou, V., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2016). Religion and well-being: The mediating role of positive emotions. Jounal of Happiness Studies, 17, 485-505. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9605-5

Van Gundy, K. T., Howerton-Orcutt, A., & Mills, M. L. (2015). Race, coping style, and substance use disorder among non-Hispanic African American and white young adults in South Florida. Substance Use & Misuse, 50, 1459-1469. doi:10.3109/10826084.2015.1018544

Womble, M. N., Labbe, E. E., & Cochran, C. (2013). Spirituality and personality: Understanding their relationship to health resilience. Psychological Reports: Mental & Physical Health, 112(3), 706-715. doi:10.2466/02.07.PR0.112.3.706-715

Yoon, E., Chang, C. C., Clawson, A., Knoll, M., Aydin, F., Barsigian, L., & Hughes, K. (2015). Religiousness, spirituality, and eudaimonic and hedonic well-being. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 28(2), 132-149. doi:10.1080/09515070.2014.968528

Table 1

Descriptive Results and Reliability Analysis for the Social Readjustment Rating Scale, Daily Spiritual Experience Scale, Substance use survey, Brief Resilience Scale, The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale, Age and Gender.

| M | SD | α | Range | |

| Stressful life events | 1.72 | .71 | 1-3 | |

| Spirituality | 49.68 | 19.48 | .949 | 16.50-96 |

| Resilience | 1.99 | 1.42 | .815 | 4.83 |

| Polysubstance use | 3.12 | .77 | .780 | 1.33 |

| Wellbeing | 45.00 | 9.11 | .909 | 16-64 |

Note, N = 102. Polysubstance use = number of substances taken more than once per month.

Table 2

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between Stressful life events, spirituality, polysubstance use, resilience and well-being.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 1. Stressful life events | |||||||

| 2. Spirituality | -.01 | ||||||

| 3. Resilience | -.01 | -.05 | |||||

| 4. Polysubstance Use | .24* | -.14 | .09 | ||||

| 5. Wellbeing | -.19 | .15 | .50** | -.13 | |||

| 6. Age | -.172 | .22* | .05 | -.32** | .01 | ||

| 7. Gender | .11 | -.12 | .307** | .30* | .23* | -.13 |

Note, N = 102.

*p p

Table 3

Role of spirituality in mediating the relationship between stressful life events and wellbeing

| 95% Bias Corrected and Accelerated CIa | ||

| LL | UL | |

| Resilience | -1.37 | 1.34 |

Note. N = 102, CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit, UL = upper limit. a = 5000 bootstraps

Wellbeing (Outcome)

Stressful Life Events (Predictor)

a) Direct Pathway

Resilience (Mediator)

Stressful Life Events (Predictor)

Wellbeing (Outcome)

b) Indirect or Mediated Pathway

Figure 1. (a) Diagram of a direct effect of stressful life events on wellbeing. (b) Diagram of a mediation model where stressful life events has an indirect effect on wellbeing through resilience (adapted from Preacher and Hayes, 2008)

β = -2.41, p t(100) = -1.91,

Resilience (Mediator)

β = 5.88, p <.001>, t(99) = 5.85

β = -0.01, p t(100) = -0.13

β = -2.33, p t(99) = -2.13

Figure 2. Direct effects between stressful life events, resilience and wellbeing.

X*W= 0.002, t(98) = 0.42

Stressful life events

(Predictor – X)

W M = -0.01, t(98) = -0.58

Resilience (Mediator – M)

Polysubstance use (Moderator – W)

b = 5.88, t(99) = 5.85, p

a = 0.12 t(98) = -0.44

Wellbeing (Outcome – Y)

c’ = -2.33, t(99) = -2.13, P

C1 (low) – β = -0.35

C2 (average) – β = -0.11

C3 (high) – β = 0.16

Figure 3. Diagram of the conditional indirect effect of stressful life events on wellbeing through resilience with moderation by spirituality

X*W = -0.05, t(98) = -0.61

W M = 0.14 – t(98) = 0.94

Resilience (Mediator – M)

Polysubstance use (Moderator – W)

B = 5.88, t(99) = 5.85, p

A = 0.05, t(98) = 0.28

Stressful life events

(Predictor – X)

Wellbeing (Outcome – Y)

c’ = -2.33, t(99) = -2.13, P

C1 (low) – b = 0.18

C2 (average) – b = -0.26

C3 (high) – b = -0.69

Figure 4. Diagram of the conditional indirect effect of stressful life events on wellbeing through resilience with moderation by polysubstance use.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Mental Health"

Mental Health relates to the emotional and psychological state that an individual is in. Mental Health can have a positive or negative impact on our behaviour, decision-making, and actions, as well as our general health and well-being.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: