Five-Factor Model Traits Effect on Organisational Commitment

Info: 10345 words (41 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Tagged: BusinessBusiness Strategy

There have been volumes of studies and research surrounding personality which was predominantly founded by Klages (1926), Baumgarten (1933), and Allport and Odbert (1936). This work started with a list of all personality-specific terms from the dictionary and was coined the “lexical hypothesis” and suggests that most of the personality characteristic phrases became part of everyday language (e.g., Allport, 1937). Allport and Odbert (1936) and Norman (1967) split the terms into certain categories that were found to overlap, which lead some researchers to believe that differences between the personality characteristics are so random they should not be included (Allen & Potkay, 1981). However, Chaplin, John, and Goldberg (1988) fought for a model where each section should not be defined in terms of its boundaries.

Cattell (1943) used Allport and Odbert’s list as a starting point for his diverse model of personality. As the size of the list was so overwhelming for research reasons, Cattell (1943, 1945) removed around 99 percent of the trait terms that Allport (1937) had classified. Using this small set of variables, Cattell identified 12 personality characteristics, which became part of his 16 Personality Factors questionnaire (Cattell, Eber, & Tatsuoka, 1970).

In the early 1980s when Costa and McCrae were working to measure three personality dimensions: Neuroticism, Extraversion, and Openness to Experience which had formed part of Cattell’s early lexical work. Their analyses highlighted the importance of Openness to Experience, which originated from a number of Cattell’s initial factors. They then added to their model Agreeableness and Conscientiousness. The Five-Factor Model was developed to initially measure the behaviours, interests, psychological wellbeing and characteristic coping styles of a person. (Costa & McCrae, 1998)

Several studies (Shoss & Witt, 2013; Witt, Burke, Barrick, & Mount, 2002) have suggested that personality trait interactions provide an indirect assessment of a specific configuration of traits interactions as predictors of workplace outcomes. One trait only provides a narrow portrayal of a person, by analysing the trait blends of a person it provides a very clear way to capture the impact of a personality and work behaviour. Although previous studies have mainly considered trait interaction effects on job performance (Guay, 2013; Penney, David, & Witt, 2011), there is limited research on the effects of each personality trait on career commitment.

Today, building and maintaining a career-committed workforce has become one of the major challenges for organisations, research suggests that Consciousness could be useful in assessing employee reliability (Barrick & Mount, 1991) which is very useful for management. It has been found that when staff is committed to their career they experience greater satisfaction, success and tend to remain committed to the organisation (Poon, 2004).

Mowday, Porter, & Steers (1982) state that organisational commitment is confidence and acceptance of the goals and values of the organisation, as well as a desire to maintain one’s status as a member of the organisation. Meyer and Allen (1991) developed a theory comprising of three components – affective, normative and continuance commitment, this was to an individual’s psychological attachment to the organisation. Affective commitment (AC) is based on emotions and feelings an employee develops within the organisation, continuance commitment (CC) is based on the costs, both economic and social, perceived if they left the organisation and normative commitment (NC) is based on the obligations perceived toward the organisation. This theory has been used to predict important employee effects like turnover, citizenship behaviours, job performance and absenteeism, of various professional groups (Meyer & Allen 1991; Meyer et al. 2002, Wasti 2003; Laka-Mathebula 2004; Lingard & Lin 2004; Ersoy 2007; Sürvegil 2007).

- Openness to Experience and Organisational Commitment

Openness to Experience is less documented than Neuroticism or Extraversion. The traits of Openness to Experience are active imagination, aesthetic sensitivity, attentiveness to inner feelings, and preference for variety, intellectual curiosity and independence of judgement (McCrae & Costa, 1987). They are eager to entertain original ideas and unusual values, and they experience both positive and negative emotions more keenly than closed individuals (Rokeach, 1960). These traits have often played a role in theories but being a single trait was not solely documented for many years (Woo, Saef, & Parrigon, 2015).

The varying types of the Five-Factor Model have labeled this factor as Intelligence. Openness is chiefly related to certain aspects of intelligence – such as divergent thinking – that contribute to creativity (McCrae, 1987). Nevertheless openness is not necessarily similar to intelligence, some intelligent people are unwilling to experience and some very open people are quite restricted in academic capability (Gregory, Nettelbeck, & Wilson, 2010).

Many job attributes can ease the expression of openness to experience. To illustrate this, openness is more likely to be demonstrated in roles that encourage an employee to challenge outdated practices, introduce unique practices, and develop additional skills (Tett & Burnett, 2003). Despite that some obstacles, which Tett and Burnett (2003) mention as constraints, could prevent the communication of openness even in roles that require creativity and intellect. For example, when materials and equipment are lacking, the capacity to establish creative ideas and engage in specific tasks is acutely constrained.

Previous research has revealed significantly that resource scarcity reduces creativity which might then reduce change as well as hinder the appearance of openness to experience. Kontoghiorghes, Awbrey, and Feurig (2005), found that finite resources, combined with deficient communication, and excessive workload, were the main obsticals to workplace adaptableness and innovation. According Gouldner, 1960; Settoon, Bennett, & Liden, (1996), when employees perceive they have not experienced the resources and support they expect, their sense of duty to the organisation reduced and their normative commitment subsides.

Two other common measures of work are CC and job satisfaction. CC, which is mainly dependent upon the accessibility of a new job (Allen & Meyer, 1990), is less likely to rely on the resources and support that employees encounter (see Meyer et al., 2002). Job satisfaction overlaps considerably with AC (Meyer et al., 2002). Furthermore, job satisfaction, in contrast to AC (Meyer et al., 2002), partly reflects the nature of individuals, as indicated by twin studies (Arvey, Bouchard, Segal, & Abraham, 1989; Arvey, McCall, Bouchard, Taubman, & Cavanaugh, 1994) and might be less possible upon the support that employees experience.

Most published studies in this area have paid attention to discovering the trait interaction effects on job performance (Guay et al., 2013; Witt, 2002). Recruiters often seek employees who manifest creativity, parade intellectual curiosity, showcase diversity, and challenge tradition. These qualities are clearly represented in openness to experience (e.g., Barrick & Mount, 1991; Goldberg, 1992; Goldberg, 1993; LePine et al., 2000; McCrae and Costa, 1987; see also Harris, 2004, McCrae & Costa, 1987). Although these qualities are usually appreciated, the assumed benefits of Openness to Experience have not been substantiated definitively. Similarly, studies that have found the coalition between openness to experience and work attitudes have not revealed definitive or encouraging findings. Openness is particularly unrelated to job satisfaction (Judge, Heller, & Mount, 2002), slightly, but linked to turnover (Salgado, 2002) career search (Boudreau, Boswell, Judge, & Bretz, 2001). Additionally, researchers have yet to explore the relationship between openness to experience across a range of environments (Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, 2002).

- Conscientiousness and Organisational Commitment

The conscientious individual is purposeful, strong willed and determined (Roberts, Lejuez, Krueger, Richards, & Hill, 2014). Digman and Takemoto-Chock (1981) referred to this domain as Will to Achieve. Conscientiousness scores are associated with academic and occupational achievement; the opposite end of the scale may lead to finicky tendencies or compulsive neatness (Roberts, Lejuez, Krueger, Richards, & Hill, 2014).

High conscientiousness scorers are meticulous, punctual and diligent while low scorers are not necessarily lacking in integrity but they are less open in applying them, just as they are more indifferent in working toward their goals (Costa, McCrae, & Dye, 1991). There is some proof that low scorers are more hedonistic and interested in sex than high scorers (McCrae, Costa & Busch, 1986)

Conscientiousness has been found not relate to AC because it has been argued to associate with a generalised work-involvement tendency (Organ & Lingl, 1995) but not an organisational-involvement tendency. As research has demonstrated, people are capable of becoming committed to various facets of the workplace including the job, occupation, and organisation (Cooper-Hakim & Viswesvaran, 2005), and such specific commitments do not necessarily have to be compatible with each other (Reichers, 1985).

Studies show that there is a consensus on the association between conscientiousness and AC of individuals. Barrick and Mount (1991) suggest that there is a positive relationship between AC and the personality traits of; conscientiousness, agreeableness and extraversion were then supported by various empirical results obtained by Judge et al. (2002), Naquin and Holton (2002), Bozionelos (2004), Watrous and Bergman (2004), Raja et al. (2004), Erdheim et al. (2006), Gelade et al. (2006) and Kumar and Bakhshi (2010). These researchers also determined an expected negative relationship with AC and Neuroticism which was described as the main source of negative affectivity.

Unlike empirical research relating to conscientiousness and AC, the relationship between conscientiousness and CC are clear across all professional groups. Researchers like McCrae and John (1992); Organ and Lingl (1995); Naquin and Holton (2002); Erdheim et al. (2006) and Kumar and Bakhshi (2010) revealed a strong positive correlation between conscientiousness and CC. These researchers affirmed it is because of conscientious employees’ “superior job association inclination”, they were more likely to acquire satisfying work rewards and because of the likely costs of leaving the current organisation it was easy to believe that they should have greater levels of CC.

- Extraversion and Organisational Commitment

Extraverts are, known to be sociable, but amiability is only one of the traits that encompass the domain of extraversion. In addition to liking people and favour large groups and meetings, extraverts are also self-assured and active (Fielden, Kim, & MacCann, 2015). Sales people represent the make-up of extraverts in western culture and the extraversion domain scale is highly correlated with an allure of imaginative occupations (Costa, McCrae & Holland, 1984; De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1997)

While it is easy to show the attributes of the extravert, the introvert is less not as easy to render. Introverts are reserved, independent, even paced and may say they are reserved when they mean they favour to be alone and may not actually suffer from social anxiety (Stock, von Hippel, & Gillert, 2016). Although they are not given to the buoyant disposition of extravert’s, introverts are not unhappy or downbeat (Costa & McCrae, 1980; McCrae & Costa, 1987).

Given that AC founds an employee’s favourable emotional reaction to the organisation and having a positive mind-set is at the core of extraversion (Watson & Clark, 1997), it is rational to presume that those with high extraversion should experience higher AC than those who are less extraverted (Cropanzano et al., 1993; Williams et al., 1996).

NC evolves from the investments that an organisation makes in its employees (Meyer & Allen, 1991). Especially, when a company supports their end of the psychological agreement, which constitutes an employee’s beliefs about the corresponding commitment between a person and the organisation (Meyer et al., 2002), that individual will feel obligated to their organisation and want to respond the organisation’s initiatives. As positive emotions are at the core of extraversion, extraverted employees may seek out more social interactions within the workplace and find these interactions more rewarding than introverts (Watson & Clark, 1997). These experiences may lead extraverted employees to requite the organisation for supplying a context for these fulfilling interpersonal exchanges. One way in which CC develops is through an employee’s perceptions of employment alternatives. Particularly, employees who perceive that they have several viable alternatives will have weaker CC than those employees who perceive that they have few alternatives (Meyer & Allen, 1997).

Extraverts seem to be more responsive to incentive aspects of a job, such as commendation and gratitude for their contributions. This shows the theory by Gray (1981, 1982), which suggested that extraverts will be reactive to rewards while introverts will be responsive to discipline. This theory has received sufficient support in research unrelated to occupational settings (Boddy, Carver, & Rowley, 1986; McCord & Wakefield, 1981), but it seems that the extravert’s reaction to positive reinforcement influences the behaviour across various environments. A low positive link between Extraversion and the hygiene composite corresponds the earlier finding by Furnham et al. (1999) and shows that extraverts may also be sensitive to some specific aspects of a job. Analysis indicated that Extraversion was a significant positive predictor of both composites. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that extraverts would highly value certain aspects in a job, such as opportunities to collaborate with others and rewards in the form of pay increases etc (e.g. Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985; Furnham & Heaven, 1999). Furthermore, this finding is in accord with evidence that the core feature of Extraversion is reward sensitivity, rather than sociability (Lucas, Diener, Grob, Suh, & Shao, 2000).

The extraversion dimension may be especially useful in predicting job satisfaction. Skinner (1983) looked at the relationship between extraversion and resilience in business occupations. Extraversion would correlate positively both most dimensions of job satisfaction while neuroticism (and psychoticism) would correlate negatively with most dimensions of job satisfaction (e.g. especially supervision. amount of work and working conditions). Extraversion, was strongly positively correlated with enterprising occupations in both men and women, and negatively correlated with conventional occupations.

Within personality, extraversion is especially is a very good discriminating variable around the area of job choice than job satisfaction. As people choose jobs hopefully similar with their personalities, and are chosen for the potential fit between their abilities needs and the job characteristics, those in jobs are likely not to have widely different personality characteristics. Therefore selection has already taken place for people at work which has presumably considerably reduced personality heterogeneity. Thus, the relationship between personality and job satisfaction is likely to be subtle and relatively small. Based on the present evidence, it can be said that Extraversion bears on what people think is important at work, with extraverts emphasising the importance of motivator aspects of the work environment while also valuing, to some extent, certain hygiene aspects.

- Agreeableness and Organisational Commitment

Agreeableness is essentially a dimension of social tendencies, people are sympathetic to others and eager to help them, and believe that others will be as obliging in return (Doucet, Shao, Wang, & Oldham, 2016). By contrast, low scores on agreeableness are disagreeable, sceptical of others’ intensions and competitive rather than cooperative (Doucet, Shao, Wang, & Oldham, 2016).

When seeing the amiable side of this domain being both socially preferable and psychologically healthier and it is certainly the case that agreeable people are more popular than unfriendly individuals (Wang, Hartl, Laursen, & Rubin, 2017). However, the readiness to fight for their own interests is often advantageous, and agreeableness is not a widely featured trait on the frontline or in court (Wang, Hartl, Laursen, & Rubin, 2017).

Neither end of this dimension is inherently better than the other from society’s point of view or is necessarily better in terms of the individual’s mental health. Horney (1945) examined two neurotic tendencies – moving towards people and moving against people – that favour pathological forms of agreeableness and antagonism. Low agreeableness scores are associated with narcissistic, antisocial and paranoid personality disorders, whereas high agreeableness scores are associated with the dependent personality disorder (Costa & Widiger, 2002). Those high in Agreeableness have been found to get along with co-workers in agreeable ways (Organ & Lingl, 1995), however it is unclear whether this affable behaviour would function as a catalyst for, or reaction to, an organisation upholding its end of the psychological contract.

Agreeableness has not been found to relate to AC because previous studies have found negative relationships with agreeableness and positive affective reactions such as job satisfaction (Judge et al., 2002). Alternatively, agreeableness and openness to experience are not hypothesised to relate to CC. Although individuals high in agreeableness often demonstrate respectful and proper workplace behaviour (Organ & Lingl, 1995), it is unlikely that this appropriate behaviour would be rewarded because it is expected, thereby failing to increase the costs associated with leaving an organisation. As a result, it involves emotional processes that are pertinent to an interpersonal context and have implications for relationships with others. Two mechanisms may show in how agreeable people cope with emotions in interpersonal situations: they experience and express empathetic feelings at others’ life events, and they may control emotions that have relationship implications (Tobin et al., 2000).

In the work context, as agreeable people can regulate emotions to maintain harmonious relationships, they may enact a friendlier environment, foster team coherence, and enjoy consideration from others, resulting in their being accepted as important and trustworthy organisational members. Therefore, as argued by Zimmerman (2008), agreeableness may engender job cohesiveness (Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski, & Erez, 2001). This likely fosters a positive affective state which may enhance identification to the organisation (Ellemers, de Gilder, & Haslam, 2004), hence AC. Indeed, the experience of positive affect facilitates social acceptance at work, thus enhancing AC. In parallel, agreeable individuals’ regulation of negative emotions likely reduces feelings of negative affect, thus helping to maintain social cohesion with others (McCarthy, Wood, & Holmes, 2017).

- Neuroticism and Organisational Commitment

The most pervasive domain of personality scales contrasts adjustment or emotional stability with dysfunction or neuroticism (Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Carl, Bullis, & Ellard, 2014). Although clinicians distinguish among many kinds of emotional distress, from social phobia to borderline hostility, studies have shown that individuals prone to any type of distress experience negative effects such as fear, sadness and embarrassment is at the core of the neuroticism domain (Eysenck, 2016). However, neuroticism includes more than receptive to psychological distress in neuroticism are also prone to have irrational ideas, to be less able to control their impulses and to cope more poorly with stress than others (Eysenck, 2016).

As the name proposes, patients who are conventionally diagnosed with suffering from neuroses generally score higher than other on measures of neuroticism (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1964) but the neuroticism scale of the Five-Factor Model measures a dimension of general personality. High scorers may be at risk for kinds of psychiatric problems, but the neuroticism scale should not be viewed as a measure of psychopathology (Garcia, & Zoellner, 2016). It is probable to obtain a high score on the neuroticism scale without having any diagnosable psychiatric disorder; equally, not all psychiatric categories imply an antisocial personality disorder without having an elevated neuroticism score (Thomson, 2016). Individuals who score low on neuroticism are emotionally stable, they are usually calm, even-tempered and relaxed and they can face stressful situations without becoming rattled (Swickert, Hittner, Foster, 2010).

In relation to commitment, neuroticism does not relate to AC because neurotic individuals tend to experience negative affect (Emmons, Diener, & Larsen, 1985), which should reduce their possibility of developing a positive emotional reaction to an organisation. These findings directly relate to CC, which may develop out of an employee’s fear of the costs associated with leaving their current position (Meyer & Allen, 1997). To the extent that negative events occur in a neurotic’s job, he or she may feel more apprehensive about facing a new work environment that could provide even harsher experiences.

Neuroticism has tendency to exhibit poor emotional adjustment and experience negative affect (Judge, Bono, Ilies, & Gerhardt, 2002). Neurotic individuals partly select themselves into situations that generate negative affect (Judge, Heller, & Mount, 2002). Accordingly, neuroticism is associated with a variety of maladaptive coping mechanisms including disengagement, wishful thinking and withdrawal (Connor-Smith & Flachsbart, 2007), and low job search self-efficacy. Neurotic individuals tend to dwell on the negative side of things (Bono & Judge, 2004), can view neutral events as problematic (Duffy, Shaw, Scott, & Tepper, 2006), and are prone to mood swings and anger (Watson, Clark, & Harkness, 1994), they tend to experience lower well-being, more stress (Ozer & Benet-Martinez, 2006), more burnout (Armon, Shirom, & Melamed, 2012) and poor relationship satisfaction with partners (White, Hendrick & Hendrick, 2004). In the work context, these outcomes may lead neurotics to experience few constructive work experiences that would create a positive commitment to the organisation, hence reducing AC, NC and CC sacrifices. Rather, commitment “by default” (Becker, 1960) may develop, that is, commitment based on few perceived alternatives. Therefor as neurotic individuals may be more likely to experience negative events at work, neuroticism will engender negative affect which, in turn, will lead to lower AC, NC and CC-sacrifices, and higher CC-alternatives (Ohana, 2016).

1.2 Rationale of the Study

The rational of this study is to explore how the relationships of personality and organisational commitment to explore whether certain traits formulate a stronger commitment to a person’s work or if there are some personality traits that hinder this. During the literature research phase there seemed to be a lots of research on certain personality types and commitment than others. The focus was around Extraversion, Conscientiousness and sometimes Neuroticism. There was also a primary focus on how these traits were linked with another variable of performance.

It became clear that there were not many studies that focused on all the traits within one study and that focussed purely on commitment. This is where this research has focussed and will be using an organisation to obtain the data from employees who may be experiencing certain types of commitment at this time. Analysis this data will allow the development of understanding to see how certain traits can affect or develop commitment to an organisation.

This will be a useful aid to organisations who have got staff who have been at the company for a long time and they will be able to gain and insight into how the staff may be feeling in regards to their commitment to the company. This will also be useful to organisations who have a high turnover of staff as they may be able to assess what type of people are leaving and why they are not committed to the company. It may be down to personality or that the organisation is not fulfilling the needs of the staff to make them feel committed.

- Hypotheses of the Study

- From the literature review presented above, it looks logical to expect that there will be a positive association between the Openness and organisational commitment. It is therefore predicted that participants who score high in the Openness variable will correspondingly indicate higher levels of organisational commitment.

- From the literature review presented above, it looks logical to expect that there will be a positive association between the Conscientiousness trait and organisational commitment. It is therefore predicted that participants who score high on the Conscientiousness variable will correspondingly indicate higher levels of organisational commitment.

- As detailed in the above literature review, there is a lack of adequate research on the link between Extraversion and organisational commitment. However, due to the reported strong link between Extraversion and job satisfaction, it is proposed that extraversion will strongly be associated with organisational commitment.

- From the literature review presented above, it looks logical to expect that there will be a positive association between the Agreeableness trait and organisational commitment. It is therefore predicted that participants who score high on the Agreeableness variable will correspondingly indicate higher levels of organisational commitment.

- From the literature review presented above, it looks logical to expect that there will be a negative association between the Neuroticism trait and organisational commitment. It is therefore anticipated that participants who score high on the neuroticism variable will correspondingly indicate lower levels of organisational commitment.

2. Methodology

2.1 Participants

Two hundred participants were invited to take part in the study – 175 returned their questionnaires and after sorting 123 were suitable to be used in the study which was a 61.5% return rate based on the questionnaires that had been completed correctly. Purposive sampling was used to select the participants as it was from the author’s place of work at the time of the dissertation being written. Each participant was sent an email to inform them of the study taking place. Following this the questionnaire packs were sent out and included two questionnaires and an information sheet. These participants were selected based on the geographical location and based on the number of staff within that area.

| Table 1 | |

| Table for Region | |

| Location | n |

| Region Red | 27 |

| Region Dark Green | 16 |

| Region Blue | 23 |

| Region Purple | 18 |

| Region Orange | 15 |

| Region Light Green | 23 |

| Total | 122 |

The chosen participants are all customer facing, branch based colleagues, who are all from small teams (8-10 members). Both male and female participants were selected (Males, N=18, SD=.82, Female N=78, SD=.82, Prefer Not to Say N=27, SD=.82), all aged between 21 to 64 years (M = 38.29, SD = 12.51).

2.2 Research Design

A within-groups design was used for the current study. The independent variable was personality traits, and the dependent variable was organisational commitment.

Regression analysis which will include multiple regressions which will show if the variables can predict commitment this will also be seen in the pattern of correlations shared by each. If you are going to do more complicated analyses (e.g. mediation or moderation regression)

2.3 Instruments / Measures

Participants’ personality traits were measured with the NEO-FFI-3. This is a 60-item version of the NEO-PI-3 that provides a quick, reliable, and accurate measure of the five domains of personality (Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness). In addition to measuring the five major domains of personality the NEO-FFI-3 gives insight into the six facets that define each domain. This scale is a 60-item self-report questionnaire containing a 5-point Likert scale, which ranged from (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Costa and McCrae (1980) founded this model after decades of research compiling the traits that each dimension to measure a personality. This model has been used all over the world and is one of the most commonly used methods in practice and in theory.

Occupational Commitment was measured with Allen and Meyer’s (1990) classic scale. This measure consists of 24 items with eight items for each of the three dimensions (AC, NC, and CC). The responses were scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

In previous studies the Five-Factor model and commitment has shown to provide reliable scores in studies such as Panaccio, Alexandra, and Vandenberghe, Christian, (2012) and Erdheim, Wang, and Zickar, (2006). The scores from both studies found that there was correlation between personality and for commitment for example “Extraversion was positively correlated with affective commitment (r = .20, p < .01). Extraversion was negatively correlated with continuance commitment (r = −.22, p < .01)“. It can be seen from these studies both questionnaires have high reliability.

2.4 Data Collection Procedure

Following approval from senior management at the participating company I was permitted to send out the questionnaires packs to the selected members of staff. As part of this the participating staff members were given an information sheet which can be seen in Appendix 1, the commitment questionnaire – see appendix 2 and the NEO-FFI-3 questionnaire – see appendix 3. The participants were given 2 weeks to complete the questionnaires and return them to me at the dedicated branch.

The information given to the participants informed them of what was expected of them as well as the ways of communication if they needed to ask questions. To ensure the ethical compliance with anonymity and confidentiality, participants were asked not to detail any personal info that will lead to their identification. They were encouraged to put their age and sex on the personality questionnaire so that the demographic data could be taken but this was not compulsory if they didn’t want to. The questionnaires had no specific order in which to be completed but were to be completed by hand. If the participant did not want to complete the questionnaire then they were at liberty to do so and were under no obligation to do so.

2.5 Ethical Procedure

Confidentiality within this study was highly considered when making the design. On the information sheet there were instructions informing participants not to include their names on the questionnaires. The information sheet also informed participants that they did not need to complete the questionnaires if they did not want to give them the options to consent to filling the questionnaire in or not. There was contact details listed on the information sheet detailing an email address they could ask questions on. Participants also contacted me directly as the place of work which was of their choice and not stipulated on the information sheet. If the participants wanted to withdraw from the study then they were able to do so.

Other ethical considerations within the study are to make sure that existing professional relationship with certain participants were not going to affect the study. To combat this, the study did not include the branch that the author was based in at due to the proximity of working relationships. There was also the consideration that there were no discussions regarding the study with other participants whom the author had working relationships with – this has been fully maintained.

Participation pressure was an area of consideration as there was potential for participant concern of where the data will be used after participation. As this study is an independent study there was need to make sure that the participants were put at ease and clearly knew that their responses were not going to be seen in raw form by the organisation they currently work for. This has been adhered to and the participants were given a plastic sealable bag to return the completed questionnaires. This was to ensure confidentiality and also to make sure that the forms were not tampered with before analysis.

3. Results

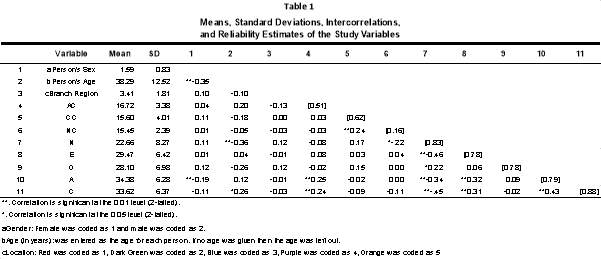

Means, standard deviations, inter-correlations, and alpha reliabilities of the study variables are reported in Table 2. All the personality measures were found to be reliable with Cronbach’s alpha above .70, within the range recommended by Nunnally (1978). The commitment scale Cronbach’s alpha score was found to be like that of other studies that used the scale (Allen & Meyer 1990; Allen & Smith 1987; Bobocel, Meyer, & Allen 1988; McGee & Ford 1987; Meyer & Allen 1984,1986; Meyer et al. 1989; Withey 1988) range from .74 to .29 for the Affective Commitment Scale (ACS), .69 to .34 for the Continuance Commitment Scale (CCS), and .69 to .79 for the Normative Commitment Scale (NCS).

Means, standard deviations, inter-correlations, and alpha reliabilities of the study variables are reported in Table 2. All the personality measures were found to be reliable with Cronbach’s alpha above .70, within the range recommended by Nunnally (1978). The commitment scale Cronbach’s alpha score was found to be like that of other studies that used the scale (Allen & Meyer 1990; Allen & Smith 1987; Bobocel, Meyer, & Allen 1988; McGee & Ford 1987; Meyer & Allen 1984,1986; Meyer et al. 1989; Withey 1988) range from .74 to .29 for the Affective Commitment Scale (ACS), .69 to .34 for the Continuance Commitment Scale (CCS), and .69 to .79 for the Normative Commitment Scale (NCS).

To test the hypotheses of the proposed interaction effects, this included demographic variables in the first block and then entered the commitment and personality to control for the main effects. This was followed by entering the interaction terms between OCEAN individually in the next step against job commitment (dependent variable). A simple linear regression was calculated to predict commitment in a work based environment based on personality traits from the Five-Factor Model.

AC and Personality

A regression equation was compiled (F(5,114)=2.16, p<.63), with an R² of .09 . AC was predicted to equal 9.93 -.03 (O) +.08 (C) + .01(E) + .11 (A) + .03 (N). Personality varies across all variables ranging between -.02 to .11 depending on the specific traits relation to AC. The scatterplot of standardised predicted values verses standardised residuals showed that the data met assumptions of homogeneity of variance and linearity and the residuals were approximately normally distributed. The correlation between commitment & personality was R=.30, indicating that 4% of the variation could be predicted (adjusted R2). The analysis showed that this was unlikely to be due to sampling error (F(5,114)= 2.16, p<.63). Personality varies across all variables ranging between -.02 to .11 depending on the specific traits relation to AC. The scatterplot of standardised predicted values verses standardised residuals showed that the data met assumptions of homogeneity of variance and linearity and the residuals were approximately normally distributed. Multicollinearity within this analysis was not present as the scores for all the personality variables and AC were under 10 and away from 1.

CC and Personality

A regression equation was compiled (F(5,114)=1.55, p<.18), with an R² of .06 . CC was predicted to equal 9.68 + .07 (O) + .01 (C) + .04 (E) -.00 (A) + .11 (N). Personality varies across all variables ranging between -.00 to .11 depending on the specific traits relation to CC. The scatterplot of standardised predicted values verses standardised residuals showed that the data met assumptions of homogeneity of variance and linearity and the residuals were approximately normally distributed. The correlation between commitment & personality was R=.25, indicating that 2% of the variation could be predicted (adjusted R²). The analysis showed that this was unlikely to be due to sampling error (F(5,114)= 1.55, p<.18). Personality varies across all variables ranging between -.00 to .11 depending on the specific traits relation to AC. The scatterplot of standardised predicted values verses standardised residuals showed that the data met assumptions of homogeneity of variance and linearity and the residuals were approximately normally distributed. Multicollinearity within this analysis was not present as the scores for all the personality variables and CC were under 10 and away from 1.

NC and Personality

A regression equation was compiled (F(5,114)= 2.53, p<.33), with an R² of .10 . NC was predicted to equal 20.95 + .03 (O) -.10 (C) -.02 (E) -.00 (A) – .11 (N). The amount of variation in job commitment explained by a measure of personality (predictor variable) was assessed using linear regression analysis (enter method). The correlation between commitment and personality was R=.10, indicating that 6% of the variation could be predicted (adjusted R²). The analysis showed that this was unlikely to be due to sampling error (F(5,114)= 2.53, p<.33). Personality varies across all variables ranging between -.00 to .11 depending on the specific traits relation to NC. The scatterplot of standardised predicted values verses standardised residuals showed that the data met assumptions of homogeneity of variance and linearity and the residuals were approximately normally distributed. Multicollinearity within this analysis was not present as the scores for all the personality variables and NC were under 10 and away from 1.

The effect of personality on commitment in the work place was analysed. Both variables were between-participant factors and therefore the data was analysed with a two-way repeated measures ANOVA. The significant results from the ANOVA were interesting to see as it was AC that came out with the most consistent across the different types of personality. The commitment types CC and NC were found to have only one significant trait from the personality scale and that was Neuroticism (CC – p = .35, NC – p = .44). All the other traits within the commitment scales of CC and NC were found to have no significance at all. The interactions with significant values were then analysed with one sample t-tests using a Bonferroni correction to reduce the likelihood of a type 1 error.

AC

- N (p = .08) = (t(120) = 6.98, p <.001, 95%CI 4.14 – 7.41).

- E (p = .06) = (t(121) = 21.30, p <.001, 95%CI 11.74 – 14.14)

- O (p = .08) = (t(120) = 15.91, p <.001, 95%CI 9.89 – 12.70)

- C (p = .05) = (t(120) = 28.62, p <.001, 95%CI 15.68 – 18.01)

CC

- N (p = .04) = (t(120) = 9.06, p <.001, 95%CI 5.32 – 8.30)

NC

- N (p = .04) = (t(120)=8.71, p <.001, 95%CI 5.44 – 8.65)

4. Discussion

Hypothesis 1 – a positive association between the Openness to Experience and organisational commitment.

- Affective Commitment and Openness to Experience

Openness to Experience and AC has a limited amount of research around it which meant comparison within this relationship was limited. Staff who score highly on this scale like to learns new things and enjoy new experiences. Linking this with AC can be seen as very positive seeing as this type of commitment means that the person feels they have a strong emotional attachment with the organisation and that they are enjoying their work. For this specific trait it means that they are able to learn new things easily and accessibly. If this was to stop then they would become less inclined to work at the same optimum commitment level. The increased job satisfaction can be seen within this highly significant relationship of openness to experience and affective commitment.

In other studies it has been found that Openness to Experience is connected with “status striving or a motivation to get ahead” (Hogan & Holland, 2003). Meaning, Openness is likely linked with a tendency to pursue job alternatives both inside and outside the organisation. Comparing this to the current results it shows that some of the staff who are currently working for the organisation are satisfied with their role and feel stimulated with the opportunities available to them and that they are not needing to look elsewhere for better opportunities as they have them currently.

- Continuance Commitment and Openness to Experience

Individuals high in Openness to Experience are more likely to prefer external alternatives, making it more likely that they will change organisations as good job alternatives arise. This is because they like to trail variety and try-out new experiences (e.g., new jobs; Erdheim et al., 2006; Maertz & Griffeth, 2004). Meaning that, individuals high in this trait are more likely to focus on the benefits of exploring new opportunities and modulate the costs of leaving their current positions. From the results it has been found that there is not significant relationship between CC and openness to experience. This will be because the type of commitment that CC is does not bare any relevance to the type of person who will have the Openness trait. The staff with this trait will see another opportunity and take and not think about staying. This will happen unless they are given new opportunities within their current work place.

- Normative Commitment and Openness to Experience

A meta-analysis by Fuller and Marler (2009) showed that Extraversion and Openness to Experience are highly related to proactive personality. Proactive individuals actively seek various and novel opportunities and more challenging and complex work experiences and therefore tend to focus on the benefits of getting a job in a new organisation rather than on the costs associated with leaving their current job (Bateman & Crant, 1993; Dragoni et al., 2011). From these results there is no significant result linking the trait openness to NC as this type of commitment means that they feel a sense of obligation to the organisation to stay and will do so even if the person wants to pursue better opportunities. They will stay in their role as they feel that it is the right thing to do. This has no significance to the Openness trait as the thought of having an obligation to stay in a place would not be motivating for this person. They will proactively want to move on with the next better opportunity.

Hypothesis 2 – a positive association between the Conscientiousness trait and organisational commitment

- Affective Commitment and Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness was significantly correlated with AC, suggesting that a possible relationship exists between the two constructs. Because conscientious individuals tend to get highly involved in their jobs (Organ & Lingl, 1995), possibly this involvement extends to the organisation as well. Looking for literature of this trait that is solely linked with organisational commitment was limited and it has been interesting to see what the results from the data will show. Having satisfied conscientious staff who have high levels of AC are just what an organisation wants. The conscientious person will be reliable and prompt which for the work place is highly regarded. Linking this with a significant level of AC means that the person is willing to grow their feelings of attachment to the organisation. In regards to the results this has been found and there is a significant relationship with these two variables. There are staff who work for the organisation who are organised and methodical as well as enjoying their work. These are the type of staff that the company will not have to work hard to keep but they will need to make sure that they are given the support from managers by being given structure and consistency otherwise their feelings of commitment could change.

- Continuance Commitment and Conscientiousness

From other studies it has been found that if the person is to have increased job involvement which “should” ultimately lead to an accrual of workplace rewards, this will heighten their feeling of the costs associated with leaving an organisation. However, if that is not there then the person will not have high scores in this area, which is what appears to have occurred. From this data there is no significant result that links these two variables together. The staff who are conscientious will be mostly be satisfied with their work but if they aren’t they will look elsewhere. They will have the feeling that they are able to keep the friendships, and respect they have built over time they have been there to satisfy their needs within their job. However, there is the chance that if they do feel that they may need to make a move follow the same type of methodical practice they will have done within their workplace in searching for a new job which will make them weigh up the pros and cons of leaving their position.

- Normative Commitment and Conscientiousness

Results of previous studies (Erdheim et al. 2006) show that the more conscientious individuals may develop a generalised involvement tendency; it therefore likely that conscientious employees will work hard and effectively. This involvement in the job may result in the organisation’s trust and support, and thus, a reciprocation of duties and rights. It is this that will make the employee feel that they are under a sense of obligation (NC) which will make them unhappy rather than empowered due to them feeling that they cannot leave as they feel they need to stay with the organisation.

Hypothesis 3 – proposed that Extraversion will strongly be associated with organisational commitment

More generally, it would be worth clarifying what extroverts gain from their environment through their emotional coping strategies. Based on commitment theory (Meyer & Allen, 1997), it would make sense that the attainment of valued rewards is the key mediating mechanism. Indeed, valued rewards may serve as a currency for social exchange (i.e., AC), felt obligation toward the organisation (i.e., NC), and a benefit one does not want to forgo in case of leaving the organisation (CC-sacrifices).

- Affective Commitment and Extraversion

Consistently with previous findings that positive emotionality and AC are positively related (Thoresen et al., 2003), Extraversion was positively related to affective commitment because positive emotionality is at the core of this personality dimension (Watson et al.,1988). Extraverts obtain their energy from interacting with staff and groups. General characteristics are normally energetic, talkative and self-confident which typically you will find in those in sales. If a person is Extraverted and has AC there is a great promotional match. The person who has a sense of AC will feel loyal to the organisation and will want to do a good job. The results show that there was a significant relationship between E and AC within this organisation which shows that there are staff who can happy in their role and due to the nature of their personality they will be able to do this well.

- Continuance Commitment and Extraversion

Extraversion was not related to continuance commitment. Possibly, due to their nature, extraverts are more likely to network and perceive job alternatives than introverts (Watson & Clark, 1997). From the results, there is no significant result showing that the extroverts would want to stay committed to their role as they will want to go out and find the next best opportunity no matter the monetary cost. Extroverts are able to take their energy in to many different environments and if they feel there is not enough interaction for them then they will become restless. As extroverts get ahead socially and are enjoyable, assertive, and dominant, they are plausibly easily trusted and likely to encourage supervisors to reward them through more challenging assignments and pay raises. There is indeed evidence that extroverts achieve higher job status in the longer term (George et al., 2011) and seek growth opportunities and perceive more job challenge (Zimmerman et al., in press).

- Normative Commitment and Extraversion

Extraversion was not significantly related to normative commitment. As NC develops from norms of affinity (Gouldner, 1960), extraverts are inclined to reciprocate their organisation because they believe it upholds the psychological contract by providing an exemplary social environment (Watson, 2000).

However, in this case where no association with NC and Extraversion, it shows that the staff who have scored low in this area could feel that there is no mutual feeling benefit from the organisation (Watson, 2000). Staff may feel like they are not being supported by the organisation and will not feel motivated to work at the same rate if they were to have an equal understanding of what is expected of them. This may be explained by the fact that extroverts in this organisation do not have the opportunity to seek out more social interactions at work (Erdheim et al., 2006), which may result in reduced opportunities to establish shared arrangements with other co-workers which will increase the feeling that they owe a lot to the organisation.

Hypothesis 4 – predicted that participants who score high on the Agreeableness variable will correspondingly indicate higher levels of organisational commitment.

As agreeable staff expresses empathetic concerns and prosocial motivation in the context of interpersonal relationships (Graziano, Jensen-Campbell, & Hair, 1996; Graziano et al. 2007), they likely build stronger exchange relationships with co-workers and the organization’s agents, such as supervisors. Their cooperative nature makes them successful in their professional work, especially in occupations in which teamwork and serving customers are a prime focus (Gelissen & de Graaf, 2006). Again, these ties may serve as currencies that foster AC, NC, and CC-sacrifices.

- Affective Commitment and Agreeableness

There is very little study complied on these two variables. The mean score of A was 34.4 which on Five Factor Model scale results in being very high. This shows that the staff in the study has come out with a high score of agreeableness. As the results show that there is no significant result from the AC and A analysis it means that the staff are not committed to the organisation. This goes against what was hypothesised as it was predicted that those who scored high in Agreeableness would be committed to the organisation but from the results there is no relationship between the two.

- Continuance Commitment and Agreeableness

Agreeableness and CC resulted in no significance after analysis. This finding is interesting as it shows that agreeable staff, through their capacity to apply unspoken control over the expression of negative affect (Haas et al., 2007), maintain better interpersonal relationships and reduce stressful situations, therefore paving the path toward more optimistic assessment of their value to others.

This self-perception may generalise to one’s feeling as a competent employee, and hence to one’s perception of opportunities in the job market. Within the results it can be seen that those who have a higher agreeableness trait within their personality will do not show to be highly committed to the organisation as they will be able to look at who they are as a person and be able to see the positive in a situation rather than looking at the negative.

- Normative Commitment and Agreeableness

Agreeableness has been related to getting along with others in pleasant and satisfying ways (Organ & Lingl, 1995), which directly relates to emotional warmth. Such emotion may increase an employee’s social identity with his or her work environment, thereby increasing his or her need to reciprocate the organisation for providing a supportive social environment. It is within this reciprocation where the agreeableness trait may come under strain as they may not be happy in a certain role but will not want to be ungrateful or appear to be unkind to those who they work for. From the results, there is no significance between NC and A which that those who are agreeable will not feel they have to stay with the organisation to make it happy.

Hypothesis 5 – negative association between the Neuroticism trait and organisational commitment

Neuroticism emerged as the most consistent predictor, significantly relating to all three forms of organisational commitment. Neuroticism is not a factor of meanness or incompetence, but one of confidence and being comfortable in one’s own skin. It encompasses one’s emotional stability and general temper. Due to their nature, neurotics are prone to experiencing negative situations (Magnus et al., 1993) and negative affect (Emmons et al., 1985), which may make them wary of becoming emotionally invested in their organisations, conscious of the costs associated with leaving a job, and aware of the atypical investments their employing organisation makes in them, fostering in return, a need to reciprocate.

Surprisingly, the results found that there is a significant relationship between Neuroticism and all types of commitment. What had been predicted was that there is a negative association between neuroticism and commitment which turned out to be incorrect.

- Affective Commitment and Neuroticism

From the results the neuroticism trait is a ranging scale within it. Those who have a low neuroticism score are usually cool and even tempered which means that they are more likely to be comfortable in their work. However, this can also mean there can be staff who are highly neurotic but like their job and appreciate the company they work for. This can be seen within AC due to the feeling of being strongly attached to the organisation. The results of the data found that AC and neuroticism (p = .09) had a very strong relationship. This goes against what was predicted in neuroticism being negatively associated with organisational commitment.

- Continuance Commitment and Neuroticism

From the results neuroticism was the only trait that had a significant relationship within CC (p = .04). As previously mentioned neuroticism has a scale that can range from even-tempered to extremely anxious. With CC being based around weighing up the pros and cons of leaving based on the loss that the person could experience it has proven interesting there is a strong relationship with this trait. It shows that staff can have traits such as pessimism; anxiety and fearfulness which alongside this trait will make people think carefully about staying with the organisation and stay with what they know, not because they have a strong affection for the organisation but because they have not got anything better to move to. It is with this type of feeling that there needs to be awareness from the organisation as this is where staff will stay and could become more temperamental or easily angered.

- Normative Commitment and Neuroticism

This is another significant result as there has been a significant relationship between NC and N (p = .04). This is a result that goes against what was expected for the hypothesis. It was hypothesised that there was to be a negative relationship between the two variables which has turned out to be positive. The traits of neuroticism alongside positive relationship with NC could end up being a very negative feeling for members of staff who have this trait and the sense of commitment. This is because the negative feelings they have for themselves is also with the organisation. They will turn to feel resentment which can also end up affecting other team members. This is the trait and commitment type that organisations should be aware of as it shows that staff does not want to be there but do not feel they can leave. Staff in this situation will become resentful and it will be for supervisors and managers to recognise this and see what can be done to alleviate their feelings.

4.1 Conclusion

If we consider highly committed employees as valuable assets, then both researchers and practitioners should find ways to nurture commitment in employees. Thus, an important goal of this study was to examine the dispositional antecedents of organisational commitment. The research was conducted to find the relationships between the FFM traits and three forms of organisational commitment. In general, the results suggested that neuroticism was the only FFM trait which was significantly associated with all the forms of organisational commitment and that some relationships were stronger only within affective commitment. Thus, our study highlights that the most common commitment type was affective commitment which is a positive result as most staff members have that feeling of commitment. It was also found that agreeableness was not as predicted in being positively correlated with all types of commitment. Finally, even though it was a significant result in how neuroticism is the most consistent trait with commitment, it is not ideal for those who have strong scores of neuroticism with NC and CC as they are not in a committed or motivated way of working.

4.2 Limitations

The present study has limitations that suggest directions for future research. Firstly, the results may have been affected by common method bias because all of our data were collected from self-report measures. As these were completed independently there were occasions where the quality of the data was compromised and had to be excluded which meant that the number of final participants had reduced due to the quality not being suitable. For future research having the researcher present when the data is being compiled would be useful as it will deter confusion.

Secondly, although the research developed and tested hypotheses regarding the FFM trait and organisational commitment relationships, there were several unexpected results. For example the high number of non-significant results did initially cause concern as to whether the data was not going to be suitable for analysis. However, the data did raise some interesting results which were useful for analysis and was different to that of previous research in the significance of each trait and commitment relationship.

Despite these limitations, this study is the first to provide a comprehensive picture of the relationships between the FFM traits and the three forms of organisational commitment, suggesting a meaningful dispositional basis of organisational commitment. Future research developing a broader, overarching theoretical framework built upon our results is needed to further clarify these linkages.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Business Strategy"

Business strategy is a set of guidelines that sets out how a business should operate and how decisions should be made with regards to achieving its goals. A business strategy should help to guide management and employees in their decision making.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: