6 Key Areas of Knowledge for a Learning and Development Practitioner

Info: 9816 words (39 pages) Dissertation

Published: 25th Aug 2021

Principles, Theories and Practices of Learning and Development “training programmes are effective only to the extent that the skills and behaviours learned and practised during instruction are actually transferred to the workplace” Chiaburu and Lindsay (2008 pp199).

Most organisations provide learning and development opportunities for employees to ensure that they can carry out their current role efficiently. In recent years Health and Safety implications have seen the introduction of some mandatory training but most learning and development will be at the organisation’s discretion.

Towler and Dipboye (2009) believe that providing employees with new knowledge and skills will not only maximise their potential but enhance the human resource skill base of the organisation. They argue that investing in the learning and development of their employees can help an organisation stay ahead of their competitors.

However, simply providing learning and development opportunities alone does not guarantee an organisation will be more productive or effective. Nevertheless, as Chiaburu and Lindsay (2008) point out training programmes are only effective if the skills learned can actually be transferred to the workplace.

The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD 2016) believe that “When effectively designed and implemented, an organisation’s learning and development strategy can deliver the capabilities, competencies and skills required to support sustainable business success”.

Anyone who has a responsibility for learning and development within their organisation should be recognised as a learning and development practitioner. This paper will review the knowledge and understanding an advanced learning and development practitioner requires to support their core practice.

To do so the paper will examine six key areas in which a learning and development practitioner requires an in-depth knowledge and understanding:

- The principles, purpose and context of learning and development.

- The learning and development cycle.

- How people learn.

- The needs of learners in relation to learning and development.

- The roles and responsibilities of the learning and development practitioner.

- Legislative and organisational requirements in relation to learning and development.

By understanding these six key areas a learning practitioner can think objectively about learning and development interventions to deliver training strategies that meet their organisation’s needs.

The Principles, Purpose and Context of Learning and Development.

It is important to identify the rationale of any learning and development initiative that an organisation intends to implement. Each organisation is responsible for ensuring employees have the appropriate skills and knowledge to achieve the organisation's strategic and operational objectives.

As previously noted (Chiaburu & Lindsay 2008) there is no point introducing training for training sake; training programmes are only effective to both the employee and the organisation if the skills learned can actually be transferred to the workplace. An organisation can ensure it is providing the correct learning and development opportunities in a number of ways, ranging from on the job training to internal and external training courses or even supported further educational studies.

The Australian HR (2017) Institute defined the purpose of workplace learning and development “as the process of acquiring new behaviours, knowledge, skills and attitudes which enhance employees' ability to meet current and future job requirements and perform at higher levels”.

Although the purpose of investing in learning and development is the up-skilling of employees to enable them to meet current and future job requirements there are other benefits. Increasing employees' generic skills can provide benefits to employee career development and succession planning as well as motivation.

To effectively implement a training or development program, an organisation needs to know what training or development is required - for the individuals, distinct departments within an organisation and the organisation as a whole. To do this an organisation needs to undertake training needs analysis. As new technologies and flexible working practices increasingly impact the modern workplace an effective training needs analysis will map these changes to the skills and abilities to the skills and abilities the workforce has and identify skills gaps.

To prevent departments duplicating work an effective training needs analysis requires coordination and planning across an organisation. Tom Holden (2002) identifies a training need as a skills or abilities shortage which by means of training and development could be reduced or eliminated. He goes on to identify that a training needs analysis will identify training needs for employees, individual departments or the organisation as a whole; this will ensure the organisation performs effectively. There are three parts to an effective training needs analysis:

- Reviewing current performance: this can be done by observation, interviews and questionnaires.

- Anticipating future problems: is new technology being introduced, has the organisations legal responsibilities changed or is government introducing new legislation that will need to be complied with?

- Using the information from above to identify the training required and analysing how this can best be provided.

These three steps will ensure that only one department provides the training to address current problems with some future proofing built in, it is focused on organisational objectives and is delivered promptly and effectively. Once an organisation has conducted a training needs analysis and identified the skill sets that need updating to meet current and future job requirements and/or will benefit succession planning and employee development, the training has to be planned and delivered.

During the planning stage the learning and development practitioner needs to be aware of what motivates learners, the different learning styles and domains (Blooms Taxonomy of Learning Domains 1956) as well as the different delivery structures and types of delivery and overcome any barriers to learning. There are two types of motivation an organisation’s learning and development practitioner will encounter.

- Intrinsic motivation where an individual is self-motivated; they actively engage themselves in learning in order to achieve their own personal goals. Within an organisation this will usually be the employee who has applied for a job, it could be a promotion and they are excited at the prospect of being trained to do this job.

- Extrinsic motivation is where the employee’s motivation is based on reward or avoiding a negative consequence. Within an organisation this could be when the current job no longer exists and the employee is placed in the redeployment pool. In some organisations if the employee does not find a job within a few months they will be made redundant

Research undertaken by Brooks et al. (1998) indicates that individuals whose motivation is to avoid consequences or obtain the baseline pass mark rarely exert more than the minimum effort required to achieve their goal. When students focus on comparing themselves with others in the same class rather than on working on achieving the skill set at their own rate they become easily discouraged and their intrinsic motivation to learn may actually decrease; it is the responsibility of the trainer to prevent this.

Trainers need to motivate students, lifting their knowledge to greater levels; Bloom's Taxonomy will assist in this. Bloom's Taxonomy of Learning Domains otherwise known as Bloom's Taxonomy was published by Dr Benjamin S Bloom in 1956 and is still relevant over sixty years on. Bloom's Taxonomy helps the learning and development practitioner understand the different learning styles and domains. It is split into three domains:

- Cognitive (mental skills or knowledge)

- Affective (emotional areas, feelings)

- Psychomotor (manual or physical skills)

The cognitive domain involves knowledge and the development of intellectual skills (Bloom, 1956). This includes the ability to recall or recognise facts and concepts involved in developing intellectual abilities. There are six categories in the cognitive processes; Bloom (1956) categorised the six categories as Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis and Evaluation.

Each category becomes progressively more difficult which means that the first one should be mastered before the next one can take place until all six have been mastered. Anderson et al (2001) suggested that learning is an active process and renamed the six categories replacing nouns with verbs and inverting synthesis and evaluation. Their revised Taxonomy is remembering, understanding, applying, analysing, evaluating and creating.

Anderson et al (2001) believe the new taxonomy to be a more active form of thinking. The second of Bloom's Taxonomy of Learning Domains is the Affective domain; the learning objectives in this domain places emphasis on feeling and emotions (Bloom et al 1964).

As with cognitive the affective processes is split into categories. There are five categories in the affective domain; receiving, responding, valuing, organisation and characterisation. The relevance of the affective domain is sometimes ignored by the learning and development practitioner. The cognitive domain gives the learning and development practitioner an insight on how to expand the knowledge and develop the intellectual skills of those being trained.

Most classroom based training focuses on the cognitive aspects of training as evaluating cognitive learning (an individual’s knowledge) is straightforward, but assessing affective outcomes is difficult. Once students receive knowledge Bloom et al (1964) believe trainers should be encouraging them to respond to what they learn, to value and organise it.

The trainer needs to find delivery structures and different types of training delivery that encourages students and draws them in. Affective topics in training include attitudes and motivation of both trainer and those being trained along with communication, classroom management and learning styles, use of technology in training and nonverbal communication. Learning and development practitioners need to understand the potential that exists to increase student learning by tapping into the affective domain.

The Psychomotor or Kinaesthetic Domain is a skills-based domain which includes physical movement, coordination, and use of the motor-skill areas. Cognitive taxonomy was described in 1956 and the effective in 1964 but it was not until the 1970s that the psychomotor domain was fully described. Dave’s (1970) taxonomy has five categories imitation, manipulation, precision, articulation and naturalisation.

In 1972 Simpson expanded the categories to seven. First is perception which he described as the “ability to use sensory cues to guide motor activity”. Stage two is set or mind-set, the readiness to act. Once ready to act the third stage is a guided response, which Dave (1970) called imitation, it’s the initial stage in learning a complex skill.

The next step up is mechanism, when the basic proficiency has been achieved; the expert stage is complex overt response when complex patterns of movement can be carried out quickly and accurately. Adaptation can only take place when skills are well developed and the individual can modify the skill to fulfil special requirements.

And finally, origination when skills are so highly developed that the individual can create movements to solve a particular problem. Although the psychomotor domain was designed to address manual skills and tasks it has real meaning not only in today’s hi-tech work environment but also in everyday activities such as using a computer keyboard or being able to use the latest iPhone. Learning takes place in multiple domains and at various degrees of complexity which is why Bloom's Taxonomy has stood the test of time.

Bloom’s Taxonomy also impacts on the type and structure of training delivery: is the learning and development practitioner imparting mental skills and knowledge (cognitive) or manual and physical skills (psychomotor)? There are numerous training delivery methods available to learning and development practitioners and the most effective way to help employees learn and retain information is by combining several methods of delivery during a training session.

This paper will focus on classroom based instructor-led training with a short section on hands-on or cascade training as they are the most relevant to the qualification and will examine the advantages and disadvantages of these training methods.

These advantages and disadvantages will include any barriers to learning such as the availability of resources, time and financial implications and the impact of technology. Classroom based instructor-led training is one of the most popular or common training methods. One of the main advantages to this type of training is its flexibility. Instructors can present a large quantity of material to large or small groups of employees. It also provides a personal, face-to-face type of training which offers the learner an opportunity to question and receive clarification on any points with which they are having difficulty.

Classroom based instructor-led training standardises the training ensuring everyone receives the same information in the same format at the same time. Classroom based instructor-led training can be cost-effective if delivered in-house as there are no extra costs to the organisation from outsourced guest speakers.

On the down side, some classroom based instructor-led training can lack interactivity and can manifest as a lecture. Large organisations may have extra costs in delivering training at multiple locations where suitable classrooms may have to be hired. Ultimately the success or failure of classroom based instructor-led training boils down to one thing, the instructor. No matter how knowledgeable a learning and development practitioner may be, if they cannot deliver their subject in a way that captures the learner's imagination they will not be an effective trainer.

Hands-on or cascade training can be cost effective and can be used to enhance employees skills in the workplace. The advantages of this type of training are in its effectiveness for bringing new employees up to speed with company policy and procedures. It can be very effective in regards to health and safety and when introducing an individual to new procedures or equipment.

Adversely this type of training is less effective with large groups especially if there is not enough equipment for everyone to use. Just because an individual is perceived to be an expert at their job does not mean they will be able to teach others to do the job to the same standard. This type of one to one training requires coaching rather than training skills.

Another advantage of coaching or cascading your skill set to a colleague is the focus on needs and what is required to improve skill set and performance; it is generally less formal than other kinds of training. Unfortunately, coaching can be disruptive to the coach’s productivity.

Computer-based training and online or E-Learning have become increasingly prevalent as technology has become more widespread and easy to use. Both have the advantage of being, in the main, easy to use and can be custom designed. Both are cost-effective as the same equipment and programs can be used by large numbers of employees 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Unfortunately computer-based training and online or E-Learning require the learner to be computer literate and have access to a computer. There is none or very limited interaction and the learner has no one to question if they do not understand a particular section of the program. Some computer based programs are poorly designed and fail to maintain the learner’s interest.

The Learning and Development Cycle

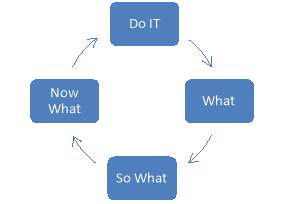

Once an organisation has defined its principles, purpose and context of learning and development it needs to understand the learning and development cycle. David Kolb (1976) published his four stage cycle of learning.

Kolb believed learning involves the acquisition of different concepts which are then applied in a range of situations. Kolb (1984, p. 38) states “Learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience”. Simply put Kolb's experiential learning theory is shown in the diagram below.

- Do it - Have and experience

- What - Reflect on that experience.

- So What - Learn from that experience.

- Now What - Try out what you have learned.

For effective learning to take place individuals needs to progress through a cycle of four stages. Stage 1 is the “do it” stage. Kolb (1984 p. 38) believes that “Learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience,” therefore in order to learn an individual is required to experience doing something.

Stage 2, “what” can only happen after an experience then consider observations and reflect on the experience. Within an organisation’s learning and development program reflective observation should not be left to the individual alone, the learning and development practitioner can help through feedback and assessments.

Stage 3 is the “so what,” which enables individuals to analyse the information they have gained to make conclusions based upon their observations.

Stage 4, the “now what” is where the individual tests out their hypothesis in future situations; they use their learning to solve problems.

Putting new knowledge into practice provides the individual with new experiences which begins the learning cycle again. Honey and Mumford (1982) developed Kolb's experiential learning theory into a slightly different learning cycle; doing, reflecting, concluding and planning. Honey and Mumford labelled individuals who prefer to enter the cycle at different stages as Activist, Reflector, Theorist and Pragmatist. While different people prefer to enter the cycle at different stages both Kolb (1984) and Honey and Mumford (1982) believe that the cycle must be completed to provide a sound foundation for learning and that it can be performed multiple times to build up layers of learning. An effective training workshop should be well-planned to facilitate each of the learning and development cycle's four stages.

How People Learn

Blooms Taxonomy explained the three main domains of learning; cognitive (thinking), affective (feeling), and psychomotor (physical). Kolb's experiential learning theory explained the learning cycle.

As everyone has their own system for absorbing, processing, comprehending and retaining information this section will explore different learning styles, learning theories and motivation theories.

Individual learning styles are as unique as the individual: everyone is different. Learning and development practitioners need to understand the differences in their students’ learning styles if they are to implement best training strategies into their training program.

The VARK model of student learning (Fleming & Baume, 2006) is one of the most widely accepted student learning styles. VARK is the acronym that refers to the four types of learning styles: Visual, Auditory, Reading/Writing and Kinaesthetic.

VARK acknowledges that each individual will absorb and process information differently prior to them comprehending and retaining information.

- Visual Learners – usually learn best from visual displays such as power point presentations and hand-outs. It’s not unusual for visual learners to sit at the front of the classroom so they can see the trainers’ body language and facial expression; this helps them to understand the content of a lesson. During lessons/discussions, visual learners prefer to take notes which will help them with absorbing and processing the information rather than get involved.

- Auditory Learners – usually learn best through verbal lessons. They prefer to listen to what others have to say and will take part in discussions. Where a visual learner will pay attention to a trainers’ body language and facial expression auditory learners interpret the meanings of speech through the trainer’s voice tone, pitch, and speed of delivery.

- Read/Write Learners – usually learn through all forms of reading and writing. They will take copious notes. It’s not unusual for read/write learners to rewrite lessons or hand-out into their own words.

- Kinaesthetic Learners - learn best through a hands-on approach. One trait of kinaesthetic learners is their difficulty with sitting still for long periods of time as they can become distracted by their need for movement.

Building on Kolb’s (1976) four stage cycle of learning Honey and Mumford (1982) labelled individuals who prefer to enter the cycle at different stages as Activist, Reflector, Theorist and Pragmatist. Activists are similar to kinaesthetic learners; they learn by doing. Their mantra is very much “Let’s just give it a go”, whereas a Reflector likes to think about what they are learning and need to understand things before trying it. Pragmatists care about what works, they are not interested in abstract concepts. Theorists like to understand where new ideas have their roots, understanding how new ideas or learning fit with what they already know.

- Activists – Let’s just do it!

- Reflectors – Let’s think about it for a moment!

- Pragmatists - How will it work in practice?

- Theorists – What are the principles behind this?

The Cognitive Learning Theory is based on the brain's ability to process and interpret information as we learn. Learning is usually defined as using your brain; how often have you heard someone say “just think about it, use your brain” and this is the basis of Cognitive Learning Theory (CLT). The theory has been used to explain mental processes as they are influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, which eventually bring about learning in an individual. The Cognitive Learning Theory explains why the brain processes and interprets information as we learn.

According to Sincero (2011), cognitive learning theory implies learning can be explained by analysing the mental processes. She believes that learning is easier with an effective cognitive process as new information can be stored in the memory for a long time. An ineffective cognitive process leads to learning difficulties. This theory can be divided into Social Cognitive Theory and Cognitive Behavioural Theory. Cognitive-Behavioural Theory is based more in psychology, highlighting on how an individual’s thoughts impact their behaviours. Negative thoughts can make it difficult for an individual to make positive behaviour choices. Social Cognitive Theory impacts on education; it is the view that people learn by watching others.

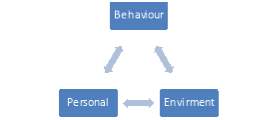

There are three variable factors which are interlinked and enables learning to take place: behaviour, environment and personal factors. Social cognitive theory explains how an individual thinks about and responds to their social environment. Bandura (1977) argued that when an individual sees someone rewarded for their behaviour, they tend to behave in the same way to receive the same reward. Bandura (1977) states that individuals are also more likely to imitate those with whom they identify. From his research Bandura formulated four principles of social learning.

- Attention - We cannot learn if we are not focused on the task.

- Retention - We learn by internalising information in our memories. We recall that information later when we are required to respond to a situation that is similar to the situation within which we first learned the information.

- Reproduction - We reproduce previously learned information (behaviour, skills, knowledge) when required.

- Motivation - We need to be motivated to do anything.

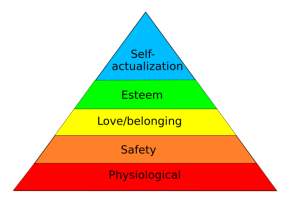

Learning and development practitioners can build on Social modelling in their training. The use of practical situations or funny anecdotes can capture students’ attention making the lesson stand out in the memory. Students can be motivated to pay attention if they see others around them also paying attention. Constructive feedback can help develop an individual’s self-efficacy, a concept that is rooted in social learning theory. Behaviourist theory assumes a learner is passive, responding to environmental stimuli. According to Watson (2013) the learner starts off as a clean slate and behaviour is shaped through positive or negative reinforcement. Watson (2013) believes that positive reinforcement increases the probability that the behaviour will be repeated and punishing reinforcement reduces this likelihood. Behaviourist theory is simple in as much it only relies on observable behaviour which is either punished or rewarded. As On Purpose Associates (2011) point out behaviourism has its critics questioning as to whether it take into account the needs of different learners in relation to their learning and development. Maslow (1943) wanted to understand what motivates people; he believed that people were motivated to achieve certain needs. Maslow (1943) believed that the needs were hierarchical so when one need is fulfilled they move on to the next one, and so on. The most popular version of Maslow's (1943, 1954) hierarchy of needs is often depicted as hierarchical levels within a pyramid.

Maslow (1954) states everyone not only has the ability to move up the hierarchy, they have a built in desire to achieve self-actualization. Maslow noted only one in a hundred people become fully self-actualized as progress can be disrupted by the failure to meet lower level needs. Everyday events such as divorce or unemployment may cause an individual to fluctuate between levels of the hierarchy. The table below shows how Analytic Technologies (2017) have applied Maslow's (1943) hierarchy of needs to the work environment.

| Need | Job |

| self-actualisation | training, advancement, growth, creativity |

| esteem | recognition, high status, responsibilities |

| belongingness | teams, departments, co-workers, clients, supervisors, subordinates |

| safety | work safety, job security, health insurance |

| physiological | heat, air, base salary |

If Analytic Technologies (2017) are correct then to achieve self-actualisation in the work place training and advancement play a major role. Maslow's (1943) hierarchy of needs also play a part in the training provided. When on a training course learners can be preoccupied. They may worry about the course and their ability to complete it, especially if it is a pass-fail course.

They worry about home life, are the children ok?

On residential courses they worry about the food and accommodation, and so on. When learners are preoccupied with these lower needs they are not concentrating on self-actualisation or the higher need which is the learning. The learning and development practitioner can help learners’ satisfy needs and return the focus to course content and learning. The table below shows one way a learning and development practitioner can guide learners through Maslow's hierarchy of needs.

| Need | Job |

| self-actualisation | Have the learners advanced and grown? Do they have the ability to apply what they have learned? |

| esteem | When marking assessments highlight achievements as well as the areas that need improvement. Make sure learners feel they are contributing and their contribution are listened to and valued |

| belongingness | Make students feel they belong. Explain there will be working in pairs and groups throughout the course. Encourage shared experiences at the introduction stage. On a residential course it is not just about class work but also the leisure facilities they can use. |

| safety | Health and Safety briefing. Fire alarms, toilets etc. This is essential to create a safe learning space. |

| physiological | Ask about their accommodation, is their room ok, not too hot or too cold. Did they sleep well? Do they have any special dietary needs? |

The Needs of Learners in relation to Learning and Development

When evaluating the needs of learners in relation to their learning and development it is important that a learning and development practitioner evaluates the needs of different types of learners, evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of adapting learning and development activities to meet those needs and preferences of learners as well as engaging learners in planning, managing and reviewing their own learning. An essential aspect of any learning and development program is its ability to meet the learning needs of all students.

So what are Learner Needs?

Noessel (2003) describes the needs of a learner as the knowledge or skills that are required to fill the gap in an individual’s current knowledge or skill set and the knowledge or skill set they are trying to acquire. Each student will be unique as highlighted in the sections above; they will have their own different learning style, knowledge set, and past experiences.

Each student will also have their own motivation for wanting to learn. Dick et al (2004) highlight the importance for learning and development practitioners to consider the level of knowledge and skill development attained by the learners prior to instruction. The best way to find out about an individual’s learning style, knowledge set, and past experiences is by asking them.

Prior to the first session the learning and development practitioner should have decided as to how they should collect and use data on learner needs. Pre-course workbooks, when properly designed and assessed, can provide invaluable information about the different types of learners that will be attending the training. As part of the introduction process a learning and development practitioner could use several icebreakers to gather the information required. The learning and development practitioner should continue to use and build upon this information throughout the training to customise their training strategies to enable all learners to achieve their maximum potential.

There are both advantages and disadvantages of adapting learning and development activities to meet the needs and preferences of all learners. There may also be a legal requirement to make reasonable adjustments that enable all learners to fulfil their potential. According to Olinghouse (2008), there are four areas where a learning and development practitioner can adapt their learning and development activities to meet the needs and preferences of learners: Content, Process, Products and Environment

- Content: What the student needs to learn. All students need to be given access to the same core content. Learning and development practitioners should vary the presentation of content, to best meet students’ needs. The advantage of this means a learning and development practitioner will have course material that will engage all learning styles from visual through to kinaesthetic. The disadvantage is that the learning and development practitioner will potentially produce learning recourses that will never or rarely be used.

- Process: the activities a learning and development practitioner uses to deliver the content. The advantages to varying the processes used to deliver the course content is that it can keep all types of learner engaged. By continually self-assessing their training delivery a learning and development practitioner will be able to identify the processes that work and those that are less effective.

- Products: The tasks students undertake to demonstrate their knowledge. The disadvantage is that it is not always possible to have a variety of products which will provide students different methods to demonstrate their knowledge. Groups of learners can be difficult to assess as there is usually a dominant group member who may try to take over; assessments and exams completed by individuals are easier to manage.

- Environment: The learning and development practitioner may not always have control over the classroom they have been allocated or external environmental factors.

Our ability to focus and sustain attention is a hallmark of a highly functioning attentional system, but sometimes we experience lapses of attention. Even when participating in something we enjoy and in which we are accomplished our attention can waver. Unsworth et al (2012) believe such failures in attention from the task at hand are caused by either external distractions or internal thoughts (daydreaming) that result in failures to perform an intended action.

Failure by the learning and development practitioner to consider individual learner differences could result in individuals not being fully engaged in the subject at hand making them easily distracted or prone to daydreaming and could lead to educational difficulties (Lindquist & McLean, 2011) The importance of engaging learners in planning, managing and reviewing their learning is two-fold. Firstly it engages them in the learning process; if the learner feels part of the process and feel that they have a say in planning the process they are more likely to talk about their learning style, knowledge set, and past experiences.

This enables the learning and development practitioner to adapt learning and development activities to meet their learners’ needs. Secondly it helps the learner to review their learning and analyse their learning gaps. If they are able to review their learning and highlight their own learning needs they will be more likely to show an interest in the subject than if learning is imposed on them (Grant 2002). Once a learner takes responsibility for their own learning it becomes more personal which increases their motivation (Grant & Stanton, 2000).

The roles and responsibilities of the learning and development practitioner

The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD 2016) states that “When effectively designed and implemented, an organisation’s learning and development strategy can deliver the capabilities, competencies and skills required to support sustainable business success”.

This statement holds true for Technical Skills Trainers employed at the College of Policing (CoP 2017) who employ Technical Skills Trainers for the “delivery of training programmes, supervising students to ensure that learning objectives are met to course specifications and agreed quality standards. Work with other College departments to provide subject matter expertise in the formulation of evidence-based policing standards and the design and development of learning products.”

To ensure that the Technical Skills Trainers carry out their role correctly the job description has nine (9) accountabilities which must be adhered to. The accountabilities also provide guidance and referral points which will enable the College Technical Skills Trainers to meet the potential needs of learners as well as guidance that ensures that they are fully engaged in improving the quality of learning and development in their training field.

The first accountability is to deliver training programmes. All training programs must be delivered using the agreed content and assessment specifications but as everyone learns in a different way Technical Skills Trainers are required to develop and adapt their teaching techniques, lesson plans and training materials to meet individual students’ needs. To do this Technical Skills Trainers require an understanding of the three main domains of learning (Blooms Taxonomy 1956 and 1964); cognitive (thinking), affective (feeling), and psychomotor (physical).

They also need to understand the differences in their students’ learning styles and which of the four types of learning styles (Fleming & Baume, 2006): Visual, Auditory, Reading/Writing and Kinaesthetic that best suits their students for any given lesson. By understanding how individuals learn, Technical Skills Trainers will ensure that all students receive a consistent, high-quality training intervention which addresses their learning and development needs.

The second accountability not only recognises that many of the subjects Technical Skills Trainer teach are in fast developing fields such as telecommunications but also links into personal development plans. Technical Skills Trainers need to continually research and refresh their own subject matter expertise. Chiaburu and Lindsay (2008) believe that training programmes are only effective if the skills and behaviours learned can be transferred to the workplace; Technical Skills Trainers at the College of Policing not only need to keep up with technological developments but changes in the law.

Directly linked to this is accountability three which requires Technical Skills Trainers to take ownership of specific training modules, courses or work-streams. Within the High Tech Crime (HTC) training, the trainers continually review lesson plans and training materials. When necessary changes are made to the HTC courses; this may be due to accountability, where the law has changed or due to technological advancements but changes are also made when professional good practice guides are updated or as a result of student feedback.

Any changes made are recorded and there is a strict version control log maintained. Accountability four requires HTC trainers to liaise with business administration and other support teams. Without doing so the HTC courses could not run. The support teams not only ensure that the students are booked on the course and have accommodation for the duration of the course but that the HTC trainers have the correct resource course materials to run the course in accordance with the agreed training delivery plan.

The first three elements of Maslow's (1943) hierarchy of needs can to some extent be met with proper liaison and support from the business administration and other support teams. Providing the correct accommodation and being able to provide food that meets the student's dietary needs goes some way to fulfilling Maslow's (1943) first level, the physiological need. Obtaining the correct classroom to run the course helps with Maslow's (1943) second level which is safety. Having the correct classroom with the correct IT which complies with health and safety needs will put the students at ease. Ensuring that there are enough of the correct resource course materials to run the course in accordance with the agreed training delivery plan will help all students to feel they are part of the class, that they belong, Maslow's (1943) third level, belongingness.

Accountability five highlights the HTC trainers Health and Safety responsibilities. It ensures that the learning environment, equipment, and resources for practical scenarios are fit for purpose and safe not only for the students but for other trainers, college employees and visitors.

Accountability six, seven and nine go hand in hand. Accountability six requires that the HTC trainers compile accurate records of formative assessments. They also need to provide feedback, identify strengths and target areas for further work and to inform and improve the quality and delivery of the Trainer’s teaching skills. Accurate student assessment records are not just used to help the individual student through what is to them a one-off course. HTC trainers analyse the assessments to identify any gaps in their training. If the majority of the students in a class do not complete an assessment to the standard expected then the HTC trainers will review how that lesson was delivered on that particular day. If over several courses there is a failure by the students to complete the same assessment to the standard expected then the whole lesson plan will be reviewed.

Accountability seven broadens what the HTC trainers do on a day to day basis so that the assessments and exams are evaluated to enable accreditation of student learning on an individual and group basis against standards of professional practice, national policing curriculum specifications and other benchmarks.

Accountability nine extends the accountability of the HTC trainer to keep accurate records of formative assessments and provide feedback to tutors, monitor and assess students on extended specialist learning programmes through the evaluation of Personal Development Portfolios (PDP) and evidence of Continuous Professional Development (CPD) and workplace assessments. Accountability eight directs HTC trainers to ensure that everyone attending the College of Policing comply with the Code of Ethics and local standing instructions and that their welfare needs are catered for. Individual’s behaviour and the way they treat others also has legal implications which are covered in more depth in the next section.

Legislative and organisational requirements in relation to learning and development

The learning and development practitioner has a duty to promote equality, diversity and inclusion under equality legislation including the Equality Act 2010. The Equality Act protects people from discrimination because of certain ‘protected characteristics’. The nine protected characteristics are:

- Age

- Disability

- Gender reassignment

- Marriage and civil partnership

- Pregnancy and maternity

- Race

- Religion and belief

- Sex

- Sexual orientation

A higher or further education establishment is liable for any breaches of the Equality Act unless it can show that it took ‘all reasonable steps’ to prevent the discrimination, harassment or victimisation from taking place. The Equality Act lists six ways where learning and development practitioners working in higher or further education establishment can discriminate against an individual.

- Direct discrimination occurs when individuals are treated less favourably than others because of a protected characteristic.

- Discrimination based on association occurs when individuals are treated less favourably than others because of their association with another person who has a protected characteristic (other than pregnancy or maternity).

- Discrimination based on perception occurs when individuals are treated less favourably than others because it is mistakenly thought that they have a protected characteristic (other than pregnancy or maternity).

- Discrimination because of pregnancy or maternity is when a female student is treated less favourably because she is or has been pregnant, has given birth in the last 26 weeks or is breastfeeding a baby who is 26 weeks or younger.

- Indirect discrimination occurs when a provision or criterion appears neutral but its impact particularly disadvantages people with a protected characteristic,

- Discrimination arising from disability occurs when individuals are treated less favourably than others because of something connected with their disability and cannot justify such treatment.

Victimisation takes place where one person treats another less favourably because he or she has asserted their legal rights in line with the Act or helped someone else to do so. There are also three types of harassment which are unlawful under the Equality Act:

- Harassment related to a relevant protected characteristic.

- Sexual harassment.

- Less favourable treatment of a student because they submit to or reject sexual harassment or harassment related to sex.

There is a duty to provide reasonable adjustments under the Equality Act but for a learning and development practitioner it should be more than just a requirement forced on them by law. The Equality Act states that reasonable adjustments should be made to ensure disabled students can fully engage not just in learning but in the facilities and services enjoyed by other students. It does not mean that the whole program will be rewritten to help one person to the detriment of all others in the class but a learning and development practitioner is expected to provide an auxiliary aid where without one a disabled student would be disadvantaged.

This could be as simple as printing hand-outs and exams on different coloured paper for a dyslexic student or allowing a dyspraxic student to do their final written exam on a computer instead of hand writing it. Legislative and organisational requirements are in place to ensure everyone can attain belongingness and provide opportunities to increase their self-esteem to reach what Maslow (1954) calls self-actualisation.

Equality Act 2010 places a duty on an Organisation and the learning and development practitioner as their representative to ensure equality, diversity and inclusion, but there are other responsibilities placed on them to provide the safety and security of learners. This is not a one-way street as the learner also needs to take responsibility for their safety and security.

Learning and development practitioners hold a position of trust and may be privy to personal information about students that they do not want disclosed to others. The Data Protection Act 1998 is intended to protect such students from the data an organisation holds on them being unlawfully disclosed to others or otherwise misused. The learning and development practitioner must uphold the eight principles of the Data Protection Act which specify that data must be

- fairly and lawfully processed

- processed for limited purposes

- adequate, relevant and not excessive

- accurate

- not kept for longer than is necessary

- processed in line with an individual’s rights

- secure

- not transferred outside the European Economic Area without adequate protection.

The Data Protection has implications regarding student record-keeping and performance monitoring. It is crucial that learning and development practitioners understand the principles of data protection and understand how to manage data responsibly and keep up to date with new legal requirements such as the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). GDPR comes into force in May 2018 and will replace data protection law providing one set of data protection rules for the EU. Organisations have a duty to maintain a safe working environment. There are three main responsibilities for the learning and development practitioner when conducting their training, which is to:

- provide a safe place of work

- provide a safe system of work

- provide adequate equipment

Safety in the classroom should not just be left to the learning and development practitioner; students need to share this responsibility by working with the learning and development practitioner to develop a safe place to learn. By providing this safe working environment we are completing level two of Maslow's (1943) hierarchy of needs, safety. Student confidentiality plays a large part in learning and forms part of the student’s human right.

Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights states, "Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.” Students should expect information given in confidence to be treated in a confidential manner. Confidentiality and trust between the learning and development practitioner and the students helps build a successful relationship which Kardon (1993) believes benefits the student as trust in the trainer will enhance the educational opportunities.

However the learning and development practitioner needs to make it clear that they cannot guarantee absolute confidentiality as there may be legal or professional reasons that require information to be shared. There will be occasions when the only way to help a student is to seeking advice from a colleague with more experience and who may be better placed to help.

Organisations keep records of their staff; some records are a legal requirement such as individual pay rates so that HM Revenue & Customs can calculate Tax and National Insurance deductions. Organisations need to keep a record of hours worked as there are limitations to working hours under the Working Time Regulations. As far as training records are concerned not all training details have to be recorded although under the Provision and Use of Work Equipment 1998 regulations (Health & Safety Executive 1998) organisations are not only required to train their staff in the correct and safe use of equipment provided, they need to keep a record of the training.

Some of the training provided by organisations, especially concerning health and safety and first aid, will require periodic refresher training. Without proper training records it would be impossible to provide this. As pointed out at the start of this paper providing employees with new knowledge and skills will not only maximise their potential but enhances the human resource skill base of the organisation (Towler & Dipboye 2009).

As part of training needs analysis organisations need to identify any potential abilities shortage which training and development could reduce or eliminate (Holden 2002). It is only by keeping detailed records of skills and training that an organisation can do this. Organisations benefit from maintaining accurate training records as it enables them to manage their business effectively as the information assists with appraisals, as well as future recruitment and training needs. Training records help with consistency in delivering an organisations policies and visions to its employees. When employees receive the same structured training and training records are up to date they don’t have any excuse of “I did not know that” or “no one told me”. The role of the learning and development practitioner is an important one so consider the thoughts of JJ Keller (2017): “The most valuable asset within your organisation are your people, and the skills & knowledge they possess”

References

Anderson, L.W. (Ed.), Krathwohl, D.R. (Ed.), Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, R.E., Pintrich, P.R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M.C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman. Australian HR Institute. (2017) Learning and Development [Online] Available at https://www.ahri.com.au/assist/learning-and-development (Accessed: 21st June 2017)

Bandura, A. (1977) Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press Bloom, B.S. (Ed.).

Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H., Krathwohl, D.R. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain.

New York: David McKay Co Inc. Bloom, S.B., Krathwohl, D.R. & Masia, B.B.(1964). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. The Classification of Educational Goals, Handbook II: Affective Domain.

New York: David McKay Company, Inc Brooks, S.R., Freiburger, S.M., & Grotheer, D.R. (1998) Improving elementary student engagement in the learning process through integrated thematic instruction.

Chicago: Saint Xavier University. Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. (2016) Learning and development strategy: an introduction – Factsheet [Online] Available at https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/strategy/ development/factsheet (Accessed: 21st June 2017)

Chiaburu and Lindsay (2008) ‘Can do or will do? The importance of self-efficacy and instrumentality for training transfer’, Human Resource Development International, 11(2) pp.199-206. Data Protection Act 1998 published by HM Government [Online] Available at https://www.gov.uk/data-protection/the-data-protection-act (Accessed 09/07/2017)

Dave, R.H. (1970). Psychomotor levels in Developing and Writing Behavioral Objectives, pp.20-21. R.J. Armstrong, ed. Tucson, Arizona: Educational Innovators Press. Dick, W. O., Carey, L., & Carey, J. O. (2004). The systematic design of instruction. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. European Convention on Human Rights (amended version) (2002) [Online] Available at http://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Convention_ENG.pdf (Accessed 09/07/2017)

Equality Act 2010 [Online] Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents pdf (Accessed 18/06/2017)

Fleming, N., and Baume, D. (2006) Learning Styles Again: VARKing up the right tree!, Educational Developments, SEDA Ltd, Issue 7.4, Nov. 2006, p4-7. [Online] Available at https://semcme.org/wp-content/uploads/Flora-Educational-Developments.pdf (Accessed 21/06/2017)

General Data Protection Regulation (2016) [Online] Available at http://www.eugdpr.org/ (Accessed (11/07/2017)

Grant, J. (2002) Learning needs assessment: assessing the need. British Medical Journal. 324 (7330) p 156-9.

Grant. J. and Stanton F.(2000) The Effectiveness of Continuing Professional Development. Edinburgh: Association for the Study of Medical Education Holden, T. (2002)Training needs analysis in a week.

London: Hodder & Stoughton. Honey, P. and Mumford, A. (1982) Manual of Learning Styles.

London: P Honey Kardon, S. (1993). Confidentiality: A different perspective [As Readers See It]. Social Work in Education, 15, 247–250.

Keller, J.J. (2017) Training Records: Going Beyond the Class Sign-In Sheet Online] Available at https://www.jjkellertraining.com/TrainingResources/1812/OSHA (Accessed: 01/06/2017)

Kolb, D. A. (1976). The Learning Style Inventory: Technical Manual. Boston: McBer & Co. Kolb, D. A. (1984).

Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (Vol. 1).

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Lindquist, S., & McLean, J. P. (2011).

Daydreaming and its correlates in an educational environment. Learning and Individual Differences, 21, 158 –167. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2010.12.006

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-96.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and Personality.

New York: Harper and Row Noessel, C. (2003). Free range learning support. Interaction Design Institute. [Online] Available at http://www.interaction-ivrea.it/theses/2002-03/c.noessel/need.htm (Accessed: 15th June 2017)

On Purpose Associates (2011). Behaviourism [Online] Available at http://www.funderstanding.com/theory/behaviorism/factsheet (Accessed: 1st June 2017)

Provision and Use of Work Equipment 1998 published by the Health & Safety Executive [Online] Available at http://www.hse.gov.uk/work-equipment-machinery/puwer.htm (Accessed 25/06/2017)

Simpson E.J. (1972). The Classification of Educational Objectives in the Psychomotor Domain. Washington, DC: Gryphon House. Sincero, S.M. (2011).

Cognitive Learning Theory. [Online] Available at https://explorable.com/cognitive-learning-theory (Accessed 26/06/2017)

Towler, A.J. and Dipboye, R.L. (2009) ‘Effects of Trainer Expressiveness, Organization and Training Orientation on Training Outcomes’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(4), pp.664-673.

Unsworth, N., Brewer, G. A., & Spillers, G. J. (2012). Variation in cognitive failures: An individual differences investigation of everyday attention and memory failures.

Journal of Memory and Language. Advance online publication. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2011.12.005 Watson, J. B. (2013). Behaviorism.

Worcestershire: Read Books Ltd. Working Time Regulations 1998 (Amended 2007) published by the Health & Safety Executive [Online] Available at http://www.hse.gov.uk/contact/faqs/workingtimedirective.htm (Accessed 25/06/2017

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Workplace Training"

Workplace training enhances or teaches new skills to employees to help improve efficiencies and confidence in carrying out a job role. Increased skills and knowledge also improves job satisfaction and career progression which can make employees more loyal to a company, reducing staff turnover.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: