Transparency and Public Participation Rights in Madagascar Environmental Law

Info: 22821 words (91 pages) Dissertation

Published: 21st Feb 2022

Abstract

It is commonly agreed that the best means to address environment issues, is the public involvement, in the decision-making process. Mining in Madagascar has tremendous potential to further the country’s development but is the most controversial area of economic development. So while although there are concerns about participation in decision-making more generally in Madagascar, participation in the mining sector is the most sensitive and high profile area and thus an appropriate field of study. As a recommendation, the study proposed that the new mining code should include practical provisions to enable the public involvement. Also, it argues that the use of Malagasy traditional form of participation may help to the promotion of participation rights.

Table of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………..1

2. VALUE OF TRANSPARENCY AND PARTICIPATION RIGHTS……..14

2.1 Justifications……………………………………14

2.1.1 Definition……………………………………14

2.1.2 Scope of application……………………………..18

2.1.3 Benefits…………………………………….20

2.2 Criticisms……………………………………..23

2.3 A problem-solving approach…………………………..24

3. BEST INTERNATIONAL PRACTICE PRINCIPLES: AARHUS CONVENTION (1998)…..26

3.1 Global relevance of the Aarhus Convention………………….26

3.1.1 Access to information ……………………………29

3.1.2 Public participation rights ………………………….32

3.2 The influence of Aarhus Convention in developing countries……….34

4. THE ACTUAL POSITION OF MADAGASCAR LAW RELATED TO THE ACCESS TO ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION AND PARTICIPATION RIGHTS…..37

4.1 Current provisions on access to environmental information and participation rights in Madagascar relating to mining activities …..39

4.1.1 General provisions………………………………39

4.1.2 Specific provisions relating to mining activities……………..40

4.1.3 Existing Institutions supporting public participation…………..43

4.2 Adequacy of these provisions; extent to which they are compatible with Aarhus……………………………………………..45

4.3 Examples of case in Madagascar………………………..48

4.3.1 Soamahamanina……………………………….48

4.3.2 Toliara Sands Project…………………………….49

4.3.3 WISCO Soalala………………………………..51

5. CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE NEW DRAFT MINING LAW TO ACCESS TO ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION AND PARTICIPATION RIGHTS…..53

5.1 Provisions on access to information and participation rights………..54

5.2 Extent to which these provisions are improvement on existing rights and are compatible with Aarhus…..56

6. CONCLUSIONS – WHAT MORE NEEDS TO BE DONE TO ENSURE MALAGASY LAW REFLECTS BEST INTERNATIONAL PRACTICE…..58

BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………62

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

BCMM Bureau du Cadastre Minier de Madagascar

EIA Environmental Impact Assessment

IMF International Monetary Fund

IFI’s International Financial Institutions

NGO’s Non Governmental Organisations

ONE Organisation National de l’Environnement

UN United Nations

UNCED United Nations Conference on Environment and Development

UNECE United Nations Economic Commission for Europe

UNEP United Nations Environment Programme

CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

Madagascar is a huge island of 597,000 km2, located in the Indian Ocean, in Southeast Africa. With its area, it is the world’s fourth largest island. Because of its rich biodiversity and natural resources, Madagascar attracts different people such as scientists, tourists, and investors. Besides, the country has established a goal: to be a country ruled by law. Therefore, many efforts have been made, by the institutions to enact and to apply the rules.

The environment constitutes a tremendous potential for the country’s development, and the law has a role to play to ensure its good management. Indeed, the establishment of the Green economy and the reconciliation of the population with its environment to promote sustainable development are among the main goal of the government.[1] In response to it, the legal concept “transparency and public participation rights” merits our attention and discussion. The reason is that the environmental issues are not only the affairs of the leaders of government but concern all the population. Without public involvement, the protection of the environment will be difficult. Meanwhile, there is high demand for public participation in Madagascar society.[2] Traditional authorities (elders within the community) and the citizens want to have input on decision having an impact on their lives. NGOs and some activists working on the promotion of environmental protection, apply pressure to the government for a better management of the natural resources, and for further respect of environmental rights.

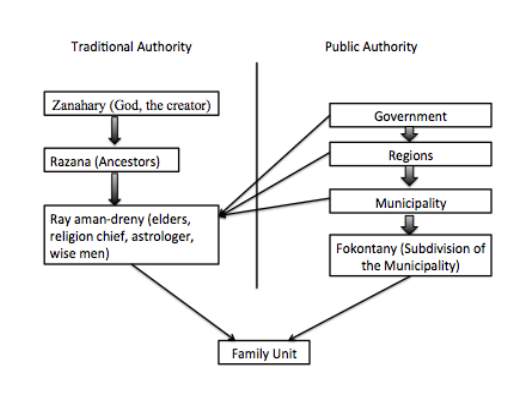

(Source: Heriniaina Andriananja, Katia Radja and Nicolas Sirven in “Ties Network in Manjakatompo, Madagascar: The Self-governance of Dry Forest, 2006, page 33)

Madagascar society is a very organised structure. This figure represents its functioning. In Madagascar, there is a coexistence of two kinds of authority within the community: one is the traditional authority, and the other is the public agency. It is important to notice that the traditional power is not a formal institution established by the law as like as the public body is, but it may have a significant influence on the organisation of the community. Also, the public authority often cooperates with the traditional authority, when dealing with critical issues.[3]

One of the traditional values having a prominent place in Madagascar community is called “FIHAVANANA”. It is a concept based on the belief that relationship is more important than money. Accordingly, each member of the community considers themselves as having one blood, and whatever happens to one individual will affect all. The spirit of goodwill and friendship constitutes the essential key to this concept “FIHAVANANA”. It implies that in every event happening within the society, each member is concerned. The sense of ownership of every decision, affecting the community, benefits from this concept. The “Ray aman-dreny” (elders of the community) are consulted by the “Family Unit” (member of the community) when they want to do some activities such as marriage, or planting rice field, so that, all the communities will be involved. Besides, the government agencies used to have contact with the elders of the communities when they want to do something in the village or city.[4]

As well, the concept of “DINA” has a valuable place in the Malagasy society. It is a “local convention” that each member of the community agreed to respect. It may include provisions relating to different aspects of the community life such as the security of the citizens, the use of the land and other natural resources. DINA also is a kind of community court, which aims to solve locally the dispute that the member of the community is facing. The elders lead the DINA, with the assistance of the other members of the community.[5] This traditional institution is very helpful because it reduces the cases going to Court and may have an efficient result. The DINA may have legally binding effect after its authentication by the public prosecutor of the Tribunal of First Instance, and the authorization from the administrative authority. In the hierarchy of norms in Madagascar, the DINA is at the lower level: Constitution, Laws and regulations, and at the lowest level is the DINA. It is organised by the legislation of 2001-004 related to the implementation of DINA.[6]

From those two concepts mentioned above, we can argue that Madagascar society has an important culture of participation, and the protection of the environment could benefit from it. The fact that the citizens are very sensitive to the respect of these traditional values reinforces the need for transparency of public participation in Madagascar environmental law.

The principle of public participation aims to give incentive to the people to be more responsible and taking part actively in the management of the environment. Besides, the international human rights instruments (ratified by Madagascar) recognised the rights to information and the rights of citizens to participate in the governance of the country (which include the management of the environment). The Malagasy Constitution, which is the fundamental law of the country, stated, “the freedom of enterprise is guaranteed by the State, within the limit of the respect for the general interest, the public order, morality and the environment.”[7] It means any investments, whether public or private, should be compatible with the environment. As well, “The Malagasy Charter of the Environment,” enacted in 2015, emphasises that the environmental protection needs the contribution of each citizen.

The human being is at the centre of any environmental law. Indeed, the link between human rights and environmental protection has attracted the attention of many environmental scholars.[8] The merits of procedural environmental rights are that it may conduct to a better environmental protection and may strengthen the legitimacy of public authority decisions. In International Environmental Law, the first instrument, having a legally binding effect on public participation rights is the Aarhus Convention of 1998. It has introduced the three pillars of participatory and procedural rights in environmental matters, which are: access to information, public participation in decision-making, and access to justice.

Although regional in scope, the Aarhus Convention of 1998, developed under the auspices of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, has a global recognition and is open for signature by any state. It is considered as a benchmark, the best international practice, in public participation.[9] Although Madagascar is not a party to this Convention, it is crucial to note that some provisions of the Charter of the Environment refer to its contents. Also, the fact that the Aarhus Convention serves as law reform model for different countries (whether developed or developing countries) and state organisations in various regions of the world makes it an incredible tool for promoting public participation rights. Besides, the Bali Guidelines is a soft law instrument developed with the participation of civil society groups and nations around the world. Its provisions, in mainly part, is inspired from the Aarhus Convention.[10]

Article 14 of the Charter of the Environment stated that the principle of public participation, including the access to environmental information, constitute a general principle, for environmental governance of the country. Nonetheless, the situation in Madagascar, regarding access to environmental information and the public participation rights, is a very critical issue, if we refer only to the mining activities. Of course, public involvement is relevant to all environmental problems, but it is more problematic in the case of a mining project in Madagascar. As the mining sector is growing fast, the awareness of the citizens regarding participation rights also raised. Most of the time, the implementation of a mining project in the country does not receive full support from the population. It seems like the attribution of exploitation permits, for example, are decided only by the administrative authorities without informing the community and involving them in the decision-making process. As well, the access to information is still difficult due to some factors such as the barrier language, and the inadequate structure of the administration in providing information.

Mining in Madagascar has tremendous potential to further the country’s development but is the most controversial area of economic development. The new Mining Law is being developed partly in response to those concerns. So while although there are concerns about participation in decision-making more generally in Madagascar, participation in the mining sector is the most sensitive and high profile area and thus an appropriate field of study. Social problems, insecurity, and poverty could be alleviated if the population has room to participate actively in the decision-making process. It starts with the reasonable access to environmental information or the respect for the transparency principle. Then, the informed citizens could be involved efficiently in taking decisions. The notion of democracy, or the right of people to self-determination, has a prominent place in Malagasy Law. As a member of the United Nations, Madagascar shares this value, and the Malagasy Constitution, in its provision, refers to it.[11] Nonetheless, the application of the notion of democracy in environmental matters is not straightforward. Some cases of protest against mining exploitation project and grievance registered by NGOs prove this statement.[12] Despite the fact that Madagascar has provisions regarding transparency and participation rights, its application is facing some problems. This is what provides the justification for exploring the extent to which transparency and public participation rights exist and are applied in Madagascar Environmental Law.

1.2 Literature Review

Public access to environmental information is a vital aspect of the notion of public participation in environmental matters, and the latter is mainly an offshoot of democratic norms. In fact, for those who are against participatory rights, the public’s right to elect a body of individuals to represent them is a satisfactory level of public participation rights. However, for Democrats like Rousseau, this is not an accurate picture of democracy. For him, democracy could only exist on a face-to-face basis where state power is decentralised and ordinary citizens are given more space to influence government actions and participate more directly in the business of government. This view has been influenced the rise of the concept of public participation rights.[13] Indeed, the strong participatory views consider that “war is too important to leave to the generals.”

Since the 1990s, public participation has become a significant topic, in international environmental law. In 1992, at the Rio Conference, more than 150 States agreed that the best means to deal with Environmental problems is the citizen involvement, at the relevant level.[14] Rio Declaration Principle 10 provided that each citizen, at national level, should have appropriate access to environmental information, held by public authorities. Also, the citizens shall have an opportunity to participate actively in decision-making procedure. As well, the States should make information widely available, and encourage the public participation. Moreover, the citizens should be offered an effective access to judicial and administrative proceedings as a remedy.[15]

Then, one of the more important steps of recognition of participation rights in environmental matters was the adoption of the Aarhus Convention, on June 25th, 1998. Although regional in scope, it is the most important elaboration of international recognition of participatory rights. Moreover, it is the first international instrument, on public participation, having a legally binding effect. The former U.N Secretary Kofi Annan considered that it was the most ambitious venture in environmental democracy undertaken under the auspices of the United Nations. Its adoption was a remarkable step forward in the development of international law.[16]

There are three main elements, in this Convention: access to environmental information, public participation in various environmental decision-making processes (including the development of plans, programs, and policies), and access to legal review (“access to justice”). For Bende Toth, the three core elements of Aarhus Convention are interdependent: “access to information is required to enable the efficient participation of the public, and access to justice is crucial to assert those other rights if they are denied.”[17]

For Ebesson, participation is critical in the formulation and implementation, of environmental law and policy; specified projects and on more general plans and programs; in monitoring and supervision; and in the enforcement of substantive laws.[18] Sagoff emphasises the importance of deliberation in Environmental Law by arguing: “…individuals should be considered as able to divest themselves of their self-interested consumer preferences, for the limited purposes of coming together as citizens, and of defining public values trough a process of deliberation.” [19]

Although Madagascar is not a member of this Convention, the Law named “Charte de l’environnement” adopted in 2015, has shown the will of the lawmakers to give more incentive to the population to be involved in the decisions concerning environmental matters. Article 3 of this law pointed out the value of environmental protection for the country, and the necessity to associate the population with that shared value. Indeed, article 7 of this law stated: “Any natural or legal person has the right to access information having some influence on the environment. To this end, any natural or legal person has the right to participate in the environmental pre-decision-making procedures.”

Bell and McGillivray found that the rationale behind the public access to environmental information is for a better monitoring of regulatory systems, to enhance its effectiveness. Also, adequate access to information, like civil rights, contributes to the enforcement of environmental law. Moreover, putting out environmental information in the public domain, besides other regulatory instruments, could help to regulate the behaviour of the public authority. Then, the access to environmental information could enable a better debate about environmental risks and might lead to better solutions.[20]

Moreover, many authors and international treaties have evoked the link between participation rights and sustainable development. For example, in Agenda 21, it is stated, “One of the fundamental prerequisites for the achievement of sustainable development is broad public participation in decision-making”.[21] Sustainable development is an important topic discussed a lot in international environmental law. However, its legal nature has raised discussion among legal scholars. Barral concluded that sustainable development’s legal environment is dependent upon two preconditions: its proper scope and its penetration into one of the recognised sources of international law.[22] An empirical study reveals that it is included in over 300 conventions; and 207 of these references are to be found in the operative part of the agreements, which are technically binding on the parties.

1.3 Scope of Study and Methodology

So the thesis would consider the existing position in Madagascar regarding access to environmental information and participation relating to mining activities and then examine how the new mining law proposes to improve the situation. Although there is a more general issue about participation in decision-making in Madagascar, the focus on mining is explained above.

As stated earlier, the Aarhus Convention is the most important Convention on participation rights (1998). Indeed, it has influenced the adoption of Bali Guidelines, which are intended to provide guidance on public participation for developing countries. Therefore, the analysis of the Malagasy Law in this regard will refer to that Convention. Our focus will be on the participatory rights given by the Malagasy Charter of the Environment, and its application to the mining activities. Besides, we will refer to some provisions regarding environmental issues found in the current Malagasy Mining Law. Also, mention of the new draft of Malagasy Mining Law is crucial to find out the solutions, which are going to improve the useful application of participation rights, and the transparency in the management of the environment, in Madagascar. Moreover, the literature on the subject will help us to have a better approach, in analysing the existing situation, in the country.

In term of structure, the thesis has six chapters:

Chapter 1 is the introduction part, in which we will present the topic and the scope of this research.

Chapter 2 deals with the value of transparency and participation rights. It will be an opportunity for us to present the reasons justifying these rights; also the criticisms addressed to it, and to develop a problem-solving approach.

After that, Chapter 3 will explore the global relevance of Aarhus Convention, and its influence in developing countries. It also covers the Bali Guidelines, which is quite similar to Aarhus Convention, in term of provisions.

Then, Chapter 4 considers the actual position of Madagascar law, related to the access to environmental information and participation rights. In this regard, comparison of the current environmental provisions with the Aarhus Convention will be made, to check the compatibility of the former to this latter.

Moreover, Chapter 5 will identify the contributions that the new draft of mining law can bring for the access to environmental information and participation rights.

Finally, the Chapter 6 will consider what more needs to be done to ensure Malagasy law reflects best international practice.

The outcomes of this research will contribute positively to the respect for the citizen’s rights to be informed and to be involved in the decisions related to environmental issues. While the focus is on mining for the reasons given above, the outcomes of the research will be potentially relevant for all areas of environmental decision-making in Madagascar. Also, it will be a tool for the citizens and the government to know their rights and obligations. In fact, information and knowledge are very crucial in respect of the principle “rule of law”, that Madagascar wants to apply.

1.4 Research Question and Research Hypotheses

The main research question is: How adequate is the existing position in Madagascar, regarding the access to environmental information, and the public participation rights, in mining activities? Then, what should be done to improve the situation?

For a better understanding of these issues, it is crucial to answer the following questions: Why are access to environmental information (transparency), and participation rights needed? Specifically, what is the value of transparency and participation rights?

Also, what is the good reference point in international law regarding the application of these rights?

The hypotheses, which drive this research, are:

Madagascar Law has made some progress, concerning the recognition of the transparency, and participatory rights, in the management of the environment. However, the effective application of these rights faces some problems, and the application of these rights could benefit from utilisation of traditional Malagasy forms of participation.

Madagascar could improve its law and the management of its environment, by implementing some provisions inspired by the international best practice.

Only an effective access to information and participatory rights could help to guarantee sustainable development in Madagascar.

CHAPTER 2 – VALUE OF TRANSPARENCY AND PARTICIPATION RIGHTS

2.1 Justifications

For a better understanding of the rationale behind transparency and participation rights, it is important to know, the definition of these notions, their scope of application, and their benefits.

2.1.1 Definition

The concept of transparency, applied to environmental law, is a principle often used in the management of the public funds. In this principle, the citizens should have access to information related to the utilisation of the public resources by government. Therefore, the public authority should respect the accounting rule, in which, the revenue and the expense of an entity, should be registered on a particular paper (e.g.: Budget). The aim of this document is for the accountability of the management, and to build trust between the government and the citizens. In a democratic country, the representatives of the people must vote the state budget to authorise the use of the public resources by the government. The rationale behind this is to seek the consent of the citizens through their representatives: it is one form of democracy.

Back to the concept of transparency in environmental law, the access to the environmental information is the first pillar of the “democratisation of the management system of the environment”. Due to some factors such as the environmental degradation, climatic changes, the concern about the preservation of the environment gain place within the international community. Therefore, it is commonly agreed that environmental issues are best handled with public participation.[23]

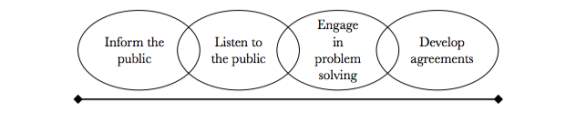

For the purpose of this study, transparency refers to the public access to environmental information. Moreover, there is a correlation between transparency and participation rights. In fact, if we refer to the definition of what participation is, it is best understood as a continuum. It has four major points, which are: Inform the public; Listen to the public; Engage in problem-solving; Develop agreements.[24]

As we can see in that figure, the access to information is a vital point to enable the public participation in decision-making process. At this point, access to environmental information, and participation rights are interdependent. The freedom of information, or the right to obtain information, in possession of the government in response to a specific request, enables the public to examine the data (raw and interpreted) that the government considers in connection with environmental decisions.[25] Without such access to information, the public participation in decision-making process would seldom advance beyond shots in the dark.[26] The government agencies might have greater success in problem-solving by working collaboratively with the public to find a solution that will enjoy broad support.[27] The term “Develop agreements” refers to the notion of consensus building. In this approach, “Consensus building is a process of seeking unanimous agreement. It involves a good-faith effort to meet the interests of all stakeholders. Consensus has been reached when everyone agrees they can live with whatever is proposed after every effort had been made to meet the interests of all stakeholding parties”.[28] However, it is important to notice that the broad support to decision does not always result in agreements. Sometimes, all that occurs is that the positions are clarified through interaction and everybody understands the reasoning behind the decision.[29] The level of public participation depends heavily on the law and the political system of the country.[30]

Public participation principle has roots from the fundamental human rights such as the right to information, and the right to be involved in the political affairs of the country. Indeed, the right to a fair trial might be evoked. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 protects these rights. The Article 19 of this international instrument of human rights provides that: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” Those elements such as the freedom of expression, seeking and receiving information are a prerequisite for political participation. Also, the Article 21 provides: “Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives.” Moreover, it is stated in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights that “Every citizen shall have the right and the opportunity …without unreasonable restrictions: (a) to take part in the conduct of public affairs, directly or through freely chosen representatives”.

Environmental issues are part of the life of a nation, so, it involves the government decision-making. For example, the decision of the government to grant or to deny a license for a private development project will affect the environment and the population who inhabit it. That is why public participation is crucial in the decision-making: the public could influence whether to have the development at all, its location and its conditions of operation.

Picolotti views participation as: “the real involvement of all social actors in social and political decision-making processes that potentially affect the communities in which they live and work”. [31] Participation can be described as well as: “All interaction between government and civil society. It is including the process by which, the public authority and the civil society open a dialogue, establish partnerships, share information, and also, relate to design, implement, and evaluate development policies, projects and programs”.[32]

In 1980, a survey on American public participation pointed out several functions of participation: “Its first function is to give information to the citizens and to get information from and about the citizens. Then, it improves the public decisions and programs. Also, it enhances the acceptance of public decisions and builds consensus. It supplements the federal agency work; and changes the political power patterns and power allocations. As well, it protects individual and minority group rights and interests. Indeed, it delays or avoids making difficult public decisions”.[33]

2.1.2 Scope of application

The concept of public participation in the environmental decision has a broad consensus among the states. However, its application differs from one state to another, depending on the legislation of the country, and the political will of the government. Nonetheless, it is important to find out the limit and extension of public participation.

The access to environmental information is intended to exchange information held by the government agencies and the citizens. In principle, any information that could affect the environment, including the people who inhabit it, should be known or be given to the concerned citizens. However, some exceptions exist to this: information classified as national secret defense, and trade secrets have not to be released to the public. The reason is obvious, certain information should remain secret, and otherwise it can cause problems within the society. For example, unveiling trade secrets of a company to the public could affect the business of the company and menace the employment of its human resources. Nonetheless, in general, when the government agencies refuse the access to information requested by the citizen, they should give the reasons for the refusal within a reasonable period.[34]

Concerning the forms of participation, the following elements should be reflected in participatory processes: First of all, the process should offer a true opportunity for the public to take part in decision-making, and to influence the outcome. Then, it should reflect a broad understanding of who may act to protect the public interests. Also, the decision process, the implementation, and the monitoring should be transparent and open.[35]

Specifically, the public participation can take a form of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), and also could be manifest by the transfer of the management of a site to a local community. The Environmental Impact Assessment is a process by which the environmental effects (positive or negative) of a project are measured. The decision to allow a project to move forward depends on the result of this assessment. During the evaluation, public hearings may be organised to listen to the opinions of the citizens about the project.[36]

Concerning the transfer of the management of a site to local community, it is a process by which the government transfers the management of natural resources (in particular, the forests) to a local organisation. The aims are to provide to the local population sources of revenue and to give them the responsibility to protect the environment. For this purpose, the use of the natural resources is submitted to the provision of agreements established by the local organisation. For example, the person who cut down a tree has the obligation to contribute to the reforestation of the site he destroys.[37]

2.1.3 Benefits

Arguing on what could be the justifications for participatory rights, Professor Ebesson finds the following elements: “Firstly, the protection of the environment and the implementation of environmental law benefits from public participation. Secondly, the public participation is required, from, substantive and procedural aspects of international human rights. Thirdly, the public participation promotes the legitimacy and acceptance of decisions related to the environment.”[38]

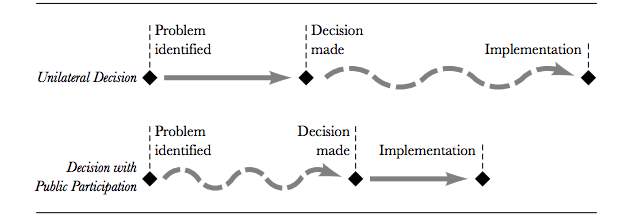

(Note: This figure represents a comparison of unilateral decision and decision with public participation regarding their implementation, in the book of James L. Creighton, “Public Participation Handbook)

Public participation is a critical process that enables an effective implementation of decisions and regulations within the society. It is true that technicians are abler than the public in understanding environmental issues. However, the decision that needs to be taken is not only a technical matter but a question of value as well. In fact, the decision will not affect only one aspect of people’s life but may concern several domains. Therefore, technicians cannot make a decision, without considering or giving a priority, to the values that society believes are good. It is clear that, to determine the acceptable level of health or safety risk, and the reasonable price to pay for the environmental protection, the public involvement is crucial, even if the experts have lots of information to handle it.[39]

Besides, public participation contributes to the fulfilment of environmental rights. It is important to notice that public involvement is two-sided: process-related where it is viewed as an end in itself and substantive where it contributes to some further significant outcomes/achievements.[40] Therefore, public participation is a critical tool to implement environmental priorities, and to find out solutions to environmental challenges, also to execute and apply the most appropriate decision.[41]

The following points could be considered as benefits of the public participation:

- Concerned persons likely to be otherwise unrepresented in, for example, environmental assessment and decision-making processes are provided, an opportunity to submit their opinions;

- Communities may provide helpful additional information to decision-makers – particularly when cultural, social or environmental values are involved that cannot be quantified easily;

- Accountability of the public authority (decision-makers) is likely to be reinforced if environmentally critical processes are open to public comment. Openness make pressure on the administrators to follow, for example, a required procedure in all cases;

- Without considering the opinions of the citizens, environmental policy runs the risk of being delayed early in the implementation phase. Public involvement enhances community ownership of decisions and resultant outcomes because of the community being part of the wider decision-making process

- The engagement of stakeholders may result in partnerships or alliances between interested parties and local government; and

- Public trust in the reviewers and decision-makers is enhanced since citizens clearly can see in every case that all environmentally relevant issues have been fully and carefully considered.[42]

Thus, different international law instruments consider the existence of an explicit link between the achievements of environmental law objectives and public participation. It is, for example, the case of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, in June 1992, which solemnly adopted the principle of public participation.[43] Then, Agenda 21, which emphasised that “genuine involvement” of all social groups, is critical to implement the Agenda 21’s objectives, policies, and mechanisms.[44] Likely, the Aarhus Convention, which aims to reinforce the needs of public involvement in environmental decision-making.[45] Moreover, participation reflects the notion of participatory democracy without which, the concept of sustainable development is without substance.[46] Indeed, public participation provides a means for scrutinising environmental decisions. Like other scrutiny techniques such as administrative review by other governmental agencies, and judicial review in the courts, public involvement and resulting publicity constitutes a source of pressure to both administrators and elected officials, to act fairly and to respect the necessary procedure in all cases. [47]

2.2 Criticisms

The notion of public participation, especially the forms of participation, divides the views among the scholars. In fact, for some authors, electing representative bodies to make a decision on behalf of citizens is a satisfactory level of public participation in decision-making.[48] As justifications of this view, the accent is put on the core logic of citizen participation in complex science-based issues. It is argued that only people with scientific or technical training can undertake active and constructive decision-making. Indeed, it is more efficient to have a small number of individuals involved in decision-making. The public is often subjective, and it takes time to reach a consensus. Most of the time, public participation does not represent truly the public opinion. On the contrary, professionals (bureaucracy, technicians) are supposed to be objective, and can quickly find solutions, and take decisions. Moreover, the organisation of public participation implies additional costs for the government, or for the projects. However, the results are not satisfactory compared to its costs. Molesworth (1985) pointed out that public participation encourages litigants to disrupt the proper processes of the administration. Also, he argued that the public could not understand the significance of the State’s mission (only government and its agencies fully understand this). Others argue that public involvement tends to experience a set of pathologies that range from paralysis by endless deliberations to reaching only insignificant results when trying to establish a consensus among the stakeholders with conflicting values and interests (Sunstein, 2001,2006). As Curtiss Ventriss said, the communicative and participative process in public affairs is inherently limited. This is due, among other things, to a complex array of social forces of selection in public deliberation. He also considered that a consensus in the public domain is like a fleeting mirage: fairness and equity among different stakeholders are ideals rarely achieved.[49] Besides, Williams and Matheny emphasise that the citizen’s involvement in environmental decision-making is intrinsically and appropriately a political process. Therefore, it involves both private and public interests.[50] To sum up, most of the critics worry that public participation in practice may not achieve the goal that it supposed to be in theory and may obstruct right decisions.

2.3 A problem-solving approach

Public participation should be regarded as a means to realise the environmental law objectives, instead of being seen as a problem. In this perspective, the focus is on the potential contributions of the public to environmental decisions. [51] Environmental law success depends on taking people’s opinion about collective goods seriously, and also by developing shared values in the public sphere. Despite the fact that conflicting interests exist within the society, collaboration among the stakeholders always leads to a better decision. In this process, citizens are considered as valuable sources of knowledge, values, and solutions.

However, to have an effective result, public involvement must respect some principles. First of all, the key to the public participation in environmental decision-making is the access to information (transparency). Technicians within the administration should give to the public, sufficient and efficient information, regarding environmental issues. In fact, the citizens should have a clear understanding of the issue that requires their participation. Then, the citizens should be offered space to express their concerns and to debate about the solutions to adopt. Collective deliberations, which give importance to the stakeholder’s opinion, are critical for a better environmental protection.

Moreover, to respond to the former critics, regarding the capacity of the citizens to give views on technical issues, it is good to remark that: both technicians and citizens have a complementary role. [52] The role of technicians is to provide information to the public and to propose to them the available solutions. Based on this, people can raise their concerns about the choice of values, or the shared values to prioritise in the final decision.[53] Also, it is true that public involvement in environmental decision-making implies costs. However, ignoring the citizens’ concerns may cost more because of the delay to implement the decisions. Decisions made with a broad consensus are easier to be applied than unilateral decisions. The trust of the citizens to the decision being made is vital for its effectiveness.

CHAPTER 3 – BEST INTERNATIONAL PRACTICE PRINCIPLES: AARHUS CONVENTION (1998)

3.1 Global relevance of the Aarhus Convention

The Aarhus Convention’s full name is the Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters.

This Convention was adopted under the auspices of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) on 25 June 1998. It has entered into force on 30 October 2001. At present, it has 47 parties, from the UNECE region, including the EU, and all EU Member States, and countries from Central and Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia.[54] Although regional in scope, the Aarhus Convention membership is open to none-UNECE members, upon approval by the Meeting of Parties.[55]

It is crucial to explore the context conducting to the adoption of Aarhus Convention, to understand its relevance. As mentioned earlier, the principle 10 of the 1992 Rio Declaration pointed out the importance of public participation for a better environmental protection. Nonetheless, it mainly offered a brief, general, even vague language for the provisions related to the public right to participation. It is comprehensive that the primary concern of such international instrument is to protect the substantive right to public participation, but substantive right without practical guide or procedure to ensure its enforcement is meaningless. The lacuna in the precision of the implication of participation norms has increased the demand of international regime to clarify this matter. Obviously, the provisions of Aarhus Convention provide this solution.

The Convention has a global relevance as it is considered as the best international practice in promoting public participation.[56] The reason is that: “Aarhus Convention is a fruit of the wider international environmental and humans rights laws considering that it was inspired by, and firmly rooted in a number of such key international initiatives.” [57] This Convention recognises the link between participation rights and human rights. Indeed, in its preamble, it makes a reference to Principle 1 of 1972 Stockholm Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment.[58] It is also the only legally binding international instrument, enshrining the principle 10 of the Rio Declaration.[59] As well, it makes a reference to the World Charter for nature. The UN Secretary Ban Ki-Moon stated that: “The Aarhus Convention is more critical than ever. This important treaty, which combines the protections of the environment and human rights, may help us facing the today’s environmental challenges such as the climate change, and the water pollution. Also, the treaty’s critical focus on involving the public is helping to keep governments accountable.” [60] Besides, many International Financial Institutions (IFI) members have a binding legal obligation to promote the principle found in the Aarhus Convention, in the policies, projects, and procedures of IFIs, when dealing with environmental matters. [61]

Of course, each country has its own culture, politics and legislation to deal with participation rights. However, the Aarhus Convention gives the minimum standard for the implementation of procedural and participatory rights. To a large extent, the Aarhus Convention serves as standard norms for many countries, including Madagascar. In fact, it combines the rules of international initiatives that apply widely and could be used as a model. Furthermore, the Convention reflects principles or rights, which have been considered as “universal in nature”; and having the potential to be a global framework that strengthening citizens’ environmental rights.[62]

Indeed, some other regions of the world are showing strong interest in the Aarhus Convention and discussing the elaboration of similar obligations. It is, for example, the case of the UNEP Bali Guidelines, which contain quite similar principles to those provided by the Aarhus Convention.[63] So although the Aarhus Convention’s principles could be criticized for being western in focus, this is unfounded because of the widespread interest in applying similar principles in developing countries across the world as Etemire has convincingly argued.[64] As Madagascar legislation is in the process of reform, the Aarhus Convention may serve as guidance for the improvements of Malagasy law on public participation.

The Aarhus Convention has the aims to promote and protect the right of every person, including the actual and future generations, to live in an environment compatible with his or her well-being. Therefore, the member should guarantee the rights and principles provided by the Convention.[65] The Convention is based on three pillars: access to information, public participation in decision-making, and access to justice. The first aims to provide to the public, adequate information, for informed environmental choices. The second enables the public to have an influence on the environmental decision. Then, the third (access to justice) seeks to address common impediments to legal challenges, by setting forth provisions designed to assure broad access to justice by the public and civil society, as a tool to ensure enforcement of environmental law and to strengthen the access to information and public participation.[66] However, our focus will be on the first two pillars: access to information, and public participation in decision-making.

3.1.1 Access to environmental information

Access to environmental information constitutes the first pillar of the Aarhus Convention. So, the Convention requires its members, to insert some provisions, within the national legislation framework, to facilitate such access. Therefore, the access to information principles may be established in constitutional provisions, legislation, and guidelines. According to the Convention, the national law should state a general rule for access to any person upon request without their having to show an interest in the required information. It means the general rule set out a presumption that the information is available on demand and any refusal should be justified.[67] Also, it extends the right of access to any person (legal entity, or natural person).

It is evident that information that will not be considered as environmental information will not be available. The Aarhus Convention defines “environmental information” as “ any information on:

- the state of the elements of the environment and the interaction with these items;

- factors affecting or likely to affect those parts; measures or activities affecting or likely to affect those factors or elements, or designed to protect those elements;

- reports on the implementation of environmental legislation;

- cost–benefit and other economic analyses and assumptions used within the framework of those measures and activities; and

- the state of human health and safety, conditions of human life, cultural sites and built structures in as much as they are or may be affected by those elements.” [68]

Moreover, it is crucial that all environmental information held by public authorities comes within the scope of the law. The term “public authorities” refers to the government and its branch (national, regional and another level), and to any natural or legal person performing public administrative functions, concerning the environment.[69] Consequently, private companies performing public duties could have the obligation to make available environmental information.[70] However, there are exceptions: institutions or bodies acting in judicial or legislative capacities are not targeted by the definition of public authorities given within the Convention.

Concerning the form of the request, the Convention does not impose formal requirements. So, it can be made orally, or in writing. Besides, for the period to reply to the request, it should be made available as soon as possible or at least within one month after the submission of the application. [71]

It is important to remark that some information cannot be disclosed for certain reasons. Therefore, exceptions to the general rule in favour of public access to information exist to protect legitimate interests that public disclosure could harm.[72] Those limitations are aimed to protect the confidentiality of international relations, national defence, public security and personal privacy. Also, exceptions designed to protect commercial interests exist, particularly, information related to intellectual property rights (e.g.: trade secret). Besides, confidential information on proceedings of public authorities is exempted from disclosure.[73] Nonetheless, those exceptions should be interpreted in a restrictive way, taking into account the public interest served by disclosure and bearing in account whether the information requested relates to emissions into the environment.[74]

It is required that the members of the Convention establish practical arrangements to provide effective access to information. A useful example of possible methods is the designation of an officer in charge of information in each ministry, department, or public authority. Indeed, the establishment of online databases, to disseminate environmental information, could permit a wider audience access to such information.[75] Online access information contents should include reports on the state of the environment, texts of legislation related to the environment, policies, programs, and agreements.

Concerning the charges or the costs of requesting information, the Convention allows the parties to take some fee, but the amount of this should be reasonable. Otherwise, it will affect the right of public access to information.

3.1.2 Public participation rights

The public participation in decision-making is the second pillar of the Aarhus Convention. To ensure effective participation, the Convention has set out certain essential requirements to follow. It is crucial to note that the Convention identifies three categories of decision-making. The first category refers to the decision-making on specific activities having a significant effect on the environment. There, for these activities, the members shall ensure that:

- The public is informed in an adequate, timely and efficient manner, about the process (by public notice, or individually).

- The public is given reasonable time frames to let them to prepare and to participate actively in the decision-making procedure.

- Early public participation is organised when all options are open and efficient participation can take place.

- All necessary information for an effective participation is made available at the time of the public involvement procedure.

- The public is authorised to submit comments, information, analyses or opinions about the proposed activity (It can be in written form, or as appropriate at the public hearing).

- Due account is taken of the outcome of public participation, and

- The text of the final decision is made available to the public, with the reasons and considerations conducting to that decision.[76]

The second category refers to public participation concerning plans, programs, and policies relating to the environment.[77] For this group, the Convention required that the parties take the following actions:

- Make practical provisions for public participation during the preparation of plans and programs connected to the environment. For this purpose, using a transparent and fair framework with adequate information is recommended.

- Ensure that the public has a reasonable period of time, to prepare and to take part actively in the procedure.

- Organising first public participation when all options are open.

- Due account shall be taken of the result of public input, and

- Providing to the public, the opportunities to participate in the preparation of the environmental policies. (Art 7)

The third category is about the public participation during the development of administrative regulations and generally applicable legally binding normative instruments.[78] For this, the parties shall strive to promote an effective participation, at an appropriate stage (Art 8).

3.2 The influence of Aarhus Convention in developing countries

The Aarhus Convention’s principles could be criticized for being western in focus, but this is unfounded because of the widespread interest in applying similar principles in developing countries across the world as this section goes on to argue. Hence it is not inappropriate to look to the Aarhus Convention in the context of developing Malagasy participation provisions.

Since 2010, the democratisation of environmental governance has received a substantial boost with the development and adoption of Bali Guidelines: “Guidelines for the Development of National Legislation on Information, Public Participation and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters.[79] In 2008, the UNEP Council Governance appointed some high-level experts from different regions of the world, to draft the Bali Guidelines.[80] It is a soft law instrument developed with the participation of nations and civil society groups around the world and adopted by the UNEP Council Governance. The later is a political body composed of 58 Members States elected by the UN for a term of three years and has the responsibility of providing recommendations for environmental policies. The seats are divided as follows: 16 seats for Africans countries, 13 seats for Asian countries, 10 seats for Latin American countries, 6 seats for East European countries, and 13 seats for Western European and other nations.[81] It implies that the development of environmental policies within this organisation results from different perspectives, which may facilitate its implementation around the world.

The Bali Guidelines contain 26 Guidelines, divided into three sections, which correspond to the three pillars of the Principle 10 of Rio Declaration. The aim of this instrument is to:

“… provide general guidance … to States, primarily developing countries, on promoting the effective implementation of their commitments to Principle 10 of the 1992 Rio Declaration … within the framework of their national legislation and processes. In doing so, the guidelines seek to assist such countries in filling possible gaps in their respective legal norms and regulations as relevant and appropriate to facilitate broad access to information, public participation and access to justice in environmental matters.”[82]

Similar to Aarhus Convention, the Bali Guidelines are focused on the three pillars system of Participatory and Procedural Rights in Environmental Matters: Access to information[83], Participation in Decision-making[84], and Access to Justice[85] in Environmental Matters. Moreover, all the provisions of Bali Guidelines are quite similar to the provisions of Aarhus Convention.[86] This fact may explain the reason why the Bali Guidelines are primarily made for developing countries, because the developed countries have already similar instrument (which is the Aarhus Convention).

An African scholar, Uzuazo Etemire, in his book “Law and Practice on Public Participation in Environmental Matters: The Nigerian Example in Transnational Comparative Perspective”, pointed out the influence that the Aarhus Convention have on the African continent, especially in the formulation of law provisions, regarding participation rights.[87] Indeed, in a United Nation Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) report on environmental public participation in Africa, embraces and acknowledges the Aarhus convention as a “model regime for public participation”.[88] Besides, in the African Union, a study for helping the government to implement provisions for “public awareness and participation” expressed the benefits of adopting African Convention similar to the Aarhus Convention, or just the adoption of the Aarhus Convention.[89]

The developing notion of transnationalisation of environmental law implies that environmental law is itself “inherently polycentric and multicultural” in nature, and consider issues which may extend beyond the national boundaries.[90] Although the Aarhus Convention is not a formal source of law for Madagascar, it still has political and legal relevance for the country.

CHAPTER 4 – THE ACTUAL POSITION OF MADAGASCAR LAW RELATED TO THE ACCESS TO ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION AND PARTICIPATION RIGHTS

The changing nature of the environment reveals new challenges and trends both at the National and International level. As the country continues to face environmental challenges, it is now also facing new environmental risks, which include chemicals management, hazardous waste management (e.g.: waste from electrical and electronic equipment), climate change, and different sources of pollution.[91]

Madagascar’s unique Biodiversity and natural resources constitute a national wealth and a global natural heritage that the country has the responsibility to preserve for present and future generations. The natural resources of Madagascar as natural capital form the basis of its sustainable development, both economic and social, and constitute an essential key to the reduction of poverty in the country.

Conscious of these challenges and values, the Malagasy government has enacted some laws to improve the environmental protection. The Malagasy Constitution, as the fundamental law of the country, recognises the principle of sustainable development, which includes the rational and equitable management of natural resources, the transparency and good governance in the conduct of public affairs, and respect for fundamental rights and freedom.[92] Also, in its Article 37, the Constitution states: “ The government guarantees the freedom of enterprise within the limits of respects for… the environment”. Besides, the “Malagasy Charter of the Environment” (Charte de l’environnement) constitutes an essential legal tool for the promotion of environmental protection in Madagascar. As stated by the Article 2 of this law, its purpose is to define the principles and general framework for the country’s environmental policy.[93] Moreover, the Article 5 of this law provides that “The environment is a priority concern of the State. Therefore, the management of the environment, including protection, conservation, valorisation, restoration and respect of the environment constitute general interests.”[94] According to Article 1 of the “Malagasy Charter of the Environment”, this law has a status of “loi-cadre” (which only means it provides general guidance for environmental policies and programs in Madagascar). It implies that the effective implementation of the principles given by this law required the enactment of specific legislation and regulations.

Concerning the access to environmental information and public participation in environmental decision-making, it is important to notice that the country has adopted some provisions relating to it. These provisions are in Article 7 and Article 14 of the Charter mentioned above. Thus, in this Chapter, we will discuss those rules. Then, we will identify the extent to which these measures are compatible with the Aarhus Convention. Finally, we will present some cases involving participation issues that happened, in Madagascar.

4.1 Current provisions on access to environmental information and participation rights in Madagascar relating to mining activities

4.1.1 General provisions

Article 11 of Malagasy Constitution recognises that every citizen has a right to information. Also, it stated that information in all its forms should not be subject to any prior restraint.[95] Moreover, the Constitution guarantees to all citizens the freedoms of speech, communication, and assembly. The only limits are the respect of the other people’s freedoms and rights, public order, and national security (Art 10). In this regard, the Malagasy Charter of the Environment stated, “Any natural or legal person has the right to access to information which may have some influence on the environment. Anyone, whether a natural or juridical person, has the right to participate in decision-making procedure which may have adverse effects on the environment.”[96] This means that Malagasy legislation has set out a general rule for access to information, and public participation in decision-making. Indeed, the law clearly states, “In the application of the principle of public participation, each citizen should have access to environmental information, including those relating to dangerous activities and substances. The public should be involved in the decision, within reasonable provisions” (Art 14).

It is relevant to notice that the Malagasy Charter of the Environment has been adopted recently, in 2015. This law has updated the former Charter of the Environment, adopted in 1990.[97] In comparison with the previous Charter, the new one has more elaborated provisions: The 2015’s law has twenty-three articles while the 1990’s law had only thirteen articles. Also, one of the features of this new law is the recognition of the principle of public participation. The Charter of the Environment of 1990 has made a reference to the principle of public participation but not in expressly manner like the new law does. Therefore, the access to environmental information and the public involvement in decision-making principles have now a critical place in the Malagasy environmental policies. Its adoption was influenced by the IFIs (IMF, World Bank), which require the adoption of such policies.[98] Furthermore, public or private investments project, which may have environmental effects, should be subject to EIA.[99]

4.1.2 Specific provisions relating to mining activities

Mining operations constitute an enormous potential for Madagascar’s economy. Nonetheless, the environmental concerns should not be forgotten. The goal is to have investments, which are compatible with environment concerns.

It is important to note that the mining sector encompasses the following mining value chain: Research; Development of the project; and Operations and Marketing. Accordingly, the EIA study should take place before the commencement of any operations.[100] The objectives of an EIA are to collect information and analyse the environmental impacts of the project. As well, it seeks the public opinions about the project. Thus, it is a form of public participation.

In Madagascar, the legal basis of EIA derives from the Charter of the Environment, adopted in 1990. Besides, there are some implementing decrees, which give more details: Decree 92-926 (1992), and Decree 95-377 (1995). At present, Decree 2004-167 of February 3rd, 2004 is the principal basis of the EIA system in the country. The order’s name is “la mise en compatibilité des investissements avec l’environnement” (MECI), which means, making investments compatible with the environment. For the mining activities, the inter-ministerial directive 12 032/2000 provides additional details relevant to mining operations. Indeed, the directive 6830/2001 of June 28th, 2001 defines the organisation of public participation in EIA.[101]

According to Decree 2008-600, the principal state organisation responsible for the promotion of the environmental protection, in the public sphere, is the “ONE” (National Organization of the Environment). It has for missions:

- The prevention of environmental risks relating to the public and private investments

- The management of environmental system (monitoring and assessing the state of the environment, for a better decision, at all levels) and,

- The environmental certification and label.[102]

Moreover, the ONE is the organisation having the particular mandate to establish or validate an “EIA screening,” from the project description and its place of implementation. The investors should request an EIA study to the ONE office. As well, the NGOs and the public may request the organization of EIA. Then, if the organisation agrees, the evaluation of the project will start. Technical expertise and public hearings are the methods they used. At the end of this process, the ONE will decide, whether to deliver or not the environmental certification, which is the precondition for starting any exploitation.[103] According to Article 4 of “MECI” decree, “are subject to EIA: All activities located in sensitive area; all activities that may have negative effects on the environment. The ONE has the authority to decide whether or not an EIA should be held”.

In Madagascar, there are two important organisations, involved with the administration of mining activities:

The “Bureau du Cadastre Minier de Madagascar”, which is responsible for the management of the mining operations in Madagascar: This entity is the authority, which delivers permits and license for anyone who wants to do such activities.

The ONE, which is responsible for the environmental aspects of the mining project:

Therefore, even the BCMM has delivered permits, for the activities, the investors should not be able to start any operations, without the possession of the environmental certification. The ONE decides whether to deliver or not the environmental certification or permit after the accomplishment of the EIA study. It implies that the legal conditions to establish mining operations in Madagascar are to hold both mining permit and environmental permit.[104]

Concerning the access to environmental information, the register of permits and license, within the BCMM, is publicly available.[105] Anyone can request information about this, with the payment of a certain amount of fee: the fee is required for those who want copies of the document, and it is fixed by ministerial directive. The office of BCMM exists only in Antananarivo (the capital of the Madagascar), and it makes the access difficult for the citizens living in the countryside. [106]Besides, the EIA study operated by the ONE should be accessible to the public, at least in theory (according to the law).

4.1.3 Existing Institutions supporting public participation

In Madagascar, there are some institutions, which may support the public participation, in a case of violations of rights:

First of all, the Administrative Tribunal, which is a particular branch of the Court System in Madagascar, may consider claims against the act, and decisions of the government. It is an institution regulated by the Law 2001-025 related to the Administrative and Financial Tribunal. Its composition is as follows: president, counsellors, State Attorney, Clerk.[107] The procedure used before this court is mainly in written form. The request, conclusion and defence of the parties are presented in written form. The application should be submitted to the clerk of the Administrative Tribunal, and the Judge will take a decision, according to the document presented by the parties.[108]

For the case of public participation, one of the possibilities to enforce it is to make an application called “recours pour excès de pouvoir” (appeal for abuse of power).[109] For example, if the citizens feel that the decisions of the public authority (government and its agencies) do not respect the law, they can make an application before the Administrative Tribunal. The decision of Tribunal may be: annulling the decision of the public authority if it is found illegal, or maintain it if the act is considered as legal. The existence of this Administrative Tribunal in Madagascar may contribute to the respect of the rule of law. However, the fact that this Tribunal is not yet implemented in the different administrative divisions of Madagascar constitutes a block for this goal. Actually, the Administrative Tribunal is based in the capital, thus making it relatively inaccessible for many citizens. Indeed, the problem of independence of the judicial branch from the executive is still a major challenge for the promotion of justice in Madagascar.[110]

Secondly, NGO’s are the most important key, as an institution, supporting public participation. NGO’s have the advantage to be closer to the citizens from the local community. Also, the member of NGO often has more knowledge of the law and can give support to the population, in need of assistance. Moreover, NGO’s can make pressure on the government for respecting citizen rights. In doing so, NGO’s often use the media, and the contact with foreign countries embassy, to influence in some way the decision of the government.[111]

Finally, traditional institution like the “DINA” may be used to solve environmental issues, and could be a mechanism for public participation. The “DINA” as already mentioned earlier is a local jurisdiction, lead by the elders of the community. In some way, it can help to settle the dispute that may happen within the society. For example, in a case that the population has not been consulted for the implementation of a mining project, and contest the functioning of the company, the company may come to the elders of the community to find solutions. As the elders have great influence in the society, it could be easier for the parties to find a consensus, which is going to end up the dispute.[112]

4.2 Adequacy of these provisions; extent to which they are compatible with Aarhus

At first glance, the Malagasy legislation, in some provisions is compliant with the Aarhus Convention. Firstly, the Malagasy Constitution and the Malagasy Charter of the Environment had set out, a general rule for the principle of public participation. Article 14 of the Malagasy Charter of the Environment, for example, stated that it recognises the principle of public participation in decision-making and the access to environmental information. Secondly, the fact that the investments, whether public or private, should be compatible with the environment and subject to EIA, constitutes a crucial point for the environmental protection.[113] As well, it offers an opportunity for the public to participate in the decision-making.

Nonetheless, Madagascar has many actions to take, before being firmly compliant with the Aarhus Convention. In fact, it is stated in Aarhus Convention that the party should have practical arrangements, to enable effective public participation. For instance, Madagascar does not have such useful methods, especially for mining activities. Since the administration of the mining industries, in the country, is centralised, the access to information is quite difficult for the broad public. For example, a citizen who lives in Tulear needs to travel seventeen hours (931.4 kilometres by bus) to have access to information, which is held by the office in the capital, Antananarivo. Such situation constitutes a block for the promotion of participation rights because the ability of the population to access to information determines the level and the quality of public involvement. The lack of effective provisions makes the substantive right to information and participation meaningless. It means that the enforcement of participation rights in Madagascar need a more effective procedure, so that, the right protected by the law will not be just a letter without effect. Here is the importance of the Aarhus Convention as it gives practical guidance for the implementation of the right to access to information and participation.

For instance, most of the information held by the public authority is in paper form, but some government agencies have started to establish online databases. This situation constitutes already a hurdle for public participation, and it is a violation of the Article 4 and the Article 6 of the Convention. As a reminder, Article 4 of the Aarhus Convention provides that the party should ensure the availability of information to the public, within the framework national legislation, including where requested such information. This provision is not entirely respected in Madagascar legislation because most of the critical information is held in the central administration. Therefore, the access to information in local level remains difficult and might imply significant costs for the citizens to get the requested information. Indeed, most of the available information is in the French language, and not in Malagasy (the most used language by the ninety percent of the population). French and Malagasy are both official language of Madagascar, but the ability of the majority of people in understanding French is yet limited. The language barrier is another challenge for the public access to information. In fact, the importance of language in communication is obvious: sharing information with someone in a language that he/she does not understand is difficult.

As the Article 6 of the Convention stated, “All necessary information for an effective participation should be available at the time of the public involvement procedure.” Unfortunately, in Madagascar, the public is informed only about some points that the developer of the EIA judge necessary. In practice, most often, the public is not informed promptly of the existence of the procedure. Then, in public hearings, the citizen does not have, the opportunity to submit views and comments; instead, it is just like a monologue (especially, in the remote area). Also, the fact that the majority of people are illiterate complicates the situation. The issue is that the consultation/hearing might be in French language, which many people will not speak or not speak well. Sometimes, this vulnerability of the citizen profits to the investors, who do not care about the rights of the population.[114] Besides, the fear of certain citizen to have contact with the public officer, or to enter into the administration office, constitute a major challenge, for the promotion of the principle of the public involvement in environmental decisions. Nonetheless, the importance of the concept “FIHAVANANA”, and participation culture in Madagascar society implies the existence of high demand for participation.

Despite the fact that Madagascar has a general provision about public participation rights, the existence of lacunas in the way of application of such rights, creates difficulties. Among other things, the lack of adequate provisions to ensure the effectiveness of the principle may be the principal reason for that. Of course, it is understandable that the law wants to protect the substantial rights (participation, access to information) in its provisions. However, it is also important that the law could give the exact implication of such rights, and the way to enforce it in practice.

For example, the directive 6830/2001 of June 28th, 2001 defines the procedure of public participation in EIA. Its provisions provide necessary step and form of participation but fail to ensure the public participation rights.

4.3 Examples of cases in Madagascar

4.3.1 Soamahamanina

In this case, a foreign company “Jiuxing Mines” has obtained an environmental certification, and mining permit to extract gold, silver, iron and zinc, for forty years. Soamahamanina is the name of the village where the permits are issued.[115]

In June 2016 the Company opened a site for the exploitation of gold and other metals. Then, some citizens of the village, supported by the NGO “Justice et Paix,” manifested their discontent against the mining project, and they asked for the public authority to suspend it.[116] They were claiming that the company did not unveil to them the potential of the project and the benefits that the citizens may gain from it. Also, the NGO claimed that the principle of public participation was not respected. The Minister in charge of mining activities, Zafilahy Ying Vah, acknowledged a failure in a public consultation procedure with the residents near the mine. Therefore, in July 2016, the government decided to suspend the activities of the company and invited the parties to enter into negotiations to find a consensus.[117]

This case showed us, the importance of public involvement in the decision having an impact on the environment prior to the project commencing. Also, it proved the veracity of the argument stated earlier that, organising public participation might cost an additional fee for a project, but implementing unilateral decision will cost much higher. Moreover, it demonstrates the influence and the role of NGO may have, as existing institutions supporting public participation.

4.3.2 Toliara Sands Project