Cyber Maritime Security – Threats and Counter Measures

Info: 8169 words (33 pages) Dissertation

Published: 23rd Feb 2022

Tagged: Cyber SecurityMaritime

INVESTIGATION OF TRIGGERS FOR THREATS TO MARITIME SECURITY AND ASSESSING EMERGING THREATS WITH EMPHASIS ON CYBER SECURITY

Ransomware victims have paid more than $25 million in ransoms over the last two years, according to a study presented today by researchers at Google, Chainalysis, UC San Diego, and the NYU Tandon School of Engineering. By following those payments through the blockchain and comparing them against known samples, researchers were able to build a comprehensive picture of the ransomware ecosystem.

Ransomware has become an almost unavoidable threat in recent years. Once a system is infected, the program encrypts all local files to a private key held only by the attackers, demanding thousands of dollars in bitcoin to recover the systems. It’s a destructive but profitable attack, one that’s proven particularly popular among cybercriminals. This summer, computers at San Francisco’s largest public radio station were locked up by a particularly brutal ransomware attack, forcing producers to rely on mechanical stopwatches and paper scripts in the aftermath.

The study tracked 34 separate families of ransomware, with a few major strains bringing in the bulk of the profits. The data shows a ransomware strain called Locky as patient zero of the recent epidemic, spurring a huge uptick in payments when it arrived in early 2016. In the years that followed, the program would bring in more than $7 million in payments.

(Brandom, 2017)

Brandom, R. (2017) Ransomware victims have paid out more than $25 million, Google study finds, The Verge, [online] Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2017/7/25/16023920/ransomware-statistics-locky-cerber-google-research (Accessed 26 July 2017).

WannaCry Attack

On 12 May 2017, the world woke up to one of the most extensive cyber-attack on IT systems and network across the world. With the attack carried out by the ‘WannaCry’ crypto worm, the term ‘ransomware’ became part of the common jargon of the IT community and a reality to contend with. The WannaCry attack (Brenner, 2017), is supposed to have infected more than 2 lakh PCs and networks in more than 150 countries. The timing of the attack was such that most organisations and companies only became aware of the attack on the morning of 15 May 2017 thereby ensuring that the ransomware had unfettered access to global corporate, business, financial networks to facilitate its spread.

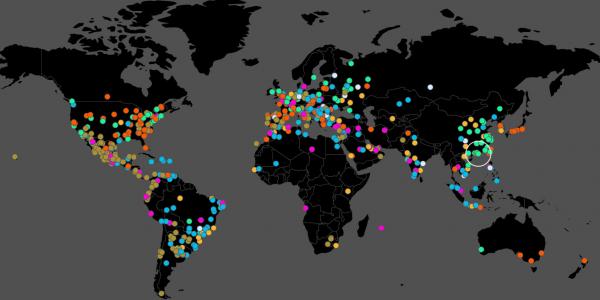

Figure 1. Spread of WannaCry ransomware May 17 (Durden, 2017)

The WannaCry ransomware propagated by using the inbuilt exploit EternalBlue of Windows Microsoft systems. Though initially believed to affect mainly PCs running the Windows XP OS, it later emerged that other Windows OS were infected too, with almost 98% of the systems running Windows 7 OS (Brandom, 2017), which forced Microsoft to issue security patched for all current OS (Microsoft, 2017) being used along with an emergency security patch for Windows XP (Warren, 2017). This, however, took Microsoft two days to issue. Luckily, a kill switch accidently discovered by a security researcher (Willgress and Walker, 2017), just hours after the attack began, could limit the spread of the ransomware.

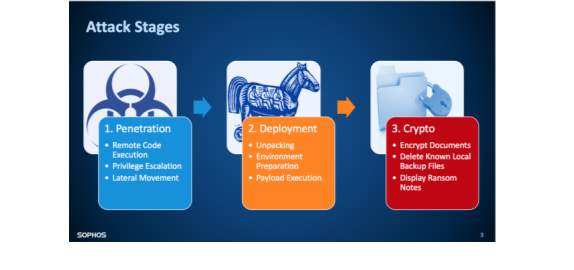

Wannacry attacked the networks in three stages (Brenner, 2017). It started with the execution of a remote code which enabled advanced user privileges. In the second stage the ransomware was unpacked and executed causing the computers to be hijacked. The ransomware then flashed the now famous ransom notes after encrypting documents on the PC. The uniqueness of the ransomware was that it did not require human intervention to spread. Also, due to some technical bugs there was no guarantee that the hackers would be able to decrypt the files. This meant that payment was not a guarantee for unlocking the systems (Symantec Official Blog, 2017).

Not everyone paid that ransom that was demanded. However, the ransom was to be paid in bitcoins to three addresses. While around $50,000 (Lynch, 2017) was received as ransom in the first three days, by July 26th, this had risen to only $144,967 (Twitter, 2017). This figure will also vary depending on the price of Bitcoin in the digital market. Furthermore, as can be seen from the Figure 3 below, no withdrawals had been made from the Bitcoin account, most likely because most Governments and Security Agencies will be keeping watch on it.

Figure 3. Ransom collected by Wannacry (Twitter, 2017)

As of 02 August 17, $142,361.51 (price variable due to fluctuating value of Bircoins), which comprises the entire ransom generated by the ‘WannaCry’ attack had been withdrawn. To sum up, while it is estimated that while the hackers caused losses of billions of dollars, they have earned less than a dollar per infected computer. The attack has shown that even major corporates and organisations that have the finances and the resources to safeguard their networks and systems have still not realised the grave threat that such attacks pose and the havoc it can cause.

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-cyber-attack-maersk-idUSKBN19I1NO

Petya Malware Attack

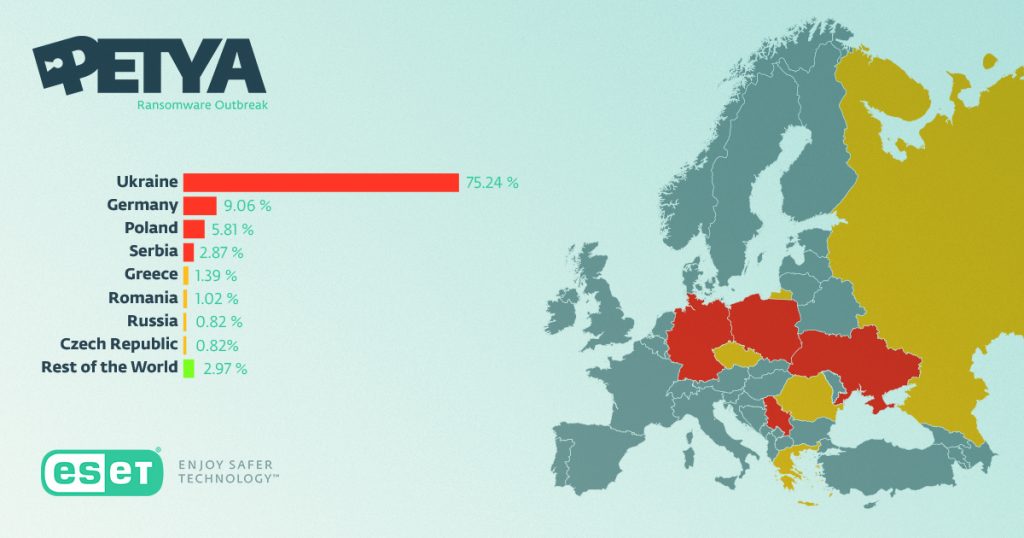

Just as the world was coming to terms with the WannaCry ransomware attack, Ukraine was at the hub of the Petya malware attack (Polityuk and Prentice, 2017). Although this came at the heels of the ransomware attack and it exploited the same vulnerabilities as the earlier attack, it was essentially different in its character. The attack was primarily aimed at Ukraine (We Live Security, 2017) as can be seen in Figure 4 below and despite throwing up warnings demanding ransomware, it went about wiping out the hard disks of computers rather than encrypt them. Experts, therefore, concluded that the proclaimed aim of the malware was monetary, its hidden intent was to cripple the government and the institutions in Ukraine (Kramer, 2017). Ukraine’s Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant was one of the victim where the attack led to the shutting down of the radiation monitoring system.

Figure 4. Spread of Petya Malware attack (We Live Security, 2017)

A case in point in the maritime sector was the world’s largest container shipping company, transporting 15 % of the worlds seaborne trade, which was also effected by the Petya cyber-attack which affected both, operations at many of its 76 port terminals in 59 countries as well as business operations / bookings ( ). Maersk is one of the industry leaders which has a new digitisation strategy for its operations. In many of the ports affected by the cyber-attack, containers could not be loaded or unloaded as the handlers could not identify whom the shipment belonged to. It took Maersk almost a week ( ) to make all its IT operations serviceable.

Cyber Threat to the Maritime Industry

The correlation between the abovementioned attacks and the threat to maritime security may not be easily discernible. What needs to be understood here is that to a hacker or a Jehadi, the computer node in a merchant vessel or a port facility is just like any other PC in a government / Corporate office with its own difficulties of firewall etc and its value to him is just based on the ransom it can fetch or the destruction / damage it can cause. It can be seen from the instances of the WannaCry ransomware attack and the Petya malware attack, the scale of cyberattacks have been getting severe and the motivation of the hackers range from ransom (which they may be willing to forego) to economic / governmental meltdown. Given the growing capabilities of cyber criminals and governmental / non-state actors, how long would it be before they target the maritime industry?

The maritime industry has been relatively insulated from the storm of cyber-attacks that seem to be sweeping the globe with only a handful being reported in the last few years. A study by Google (Brandom, 2017) has found that in the last two years ransomware victims have paid ransom in the excess of $ 25 million. Consider the lethality of a merchant vessel going rogue in the Suez Canal. It could disrupt the International Sea Laves and the Supply Chain Network, given the fact that 90% of trade happens through the seas. As early as 2014 Reuters had predicted that as more oil rigs, port facilities, containers and merchant vessels connect to the internet, they expose them to attack (Wagstaff, 2014). They reported how in one case an oil rigs had been hacked and caused to tilt and another was flooded with malware making them non-operational.

In a high-profile case, that started in 2011 and lasted for over two years, drugs were being shipped to Antwerp in containers along with banana shipments (Freeman, 2013). Belgian hackers hired by the cartel then identified the containers by hacking into the ports management system and did away with the containers before the real owners could claim them (Bateman, 2013). When the breach was detected and a firewall was installed, the hackers physically breached the security, installed wireless bridges to give them direct access to the system. By the time the case was solved in 2013, it is unknown as to how much quantity of drugs had been shipped, but can only be estimated from the seizures at the end, which amounted to £260 million.

What Makes it Vulnerable?

Automation

Preparedness of the industry in tackling the cyber threat has been discussed in later sections. However, at this juncture, while both IMO and BIMCO, have issued guidelines ( ), the question remains whether they are adequate to counter the current risks. IMO and BIMCO have linked Cyber Security to the ISM code thereby diluting the urgency needed to counter the cyber threat ( ).

The Unmanned Cargo Ship Alliance – Current Members

- Chaired by HNA Technology Group Co Ltd

- American Bureau of Shipping

- China Classification Society

- China Ship Research and Development Institute

- Shanghai Marine Diesel Engine Research Institute Ltd

- Hudong – Zhonghua Shipbuilding (Group) Co Ltd

- Marine Design Research Institute of China

- Rolls – Royce

- Wartsila

The Unmanned Cargo Ship Alliance

What make the shipping industry highly vulnerable is its growing tilt towards digitisation and preferred dependence on Information Commutation Technology (ICT) to manage its fleets and resources. In June, American Bureau of Shipping and other industry partners came together to launch the ‘Unmanned Cargo Ship Development Alliance’ in Shanghai, China. The alliance plans to collaborate and apply the latest technologies to design and formulate a new autonomous ship concept with the target to deliver the unmanned cargo ship by Oct 2021 ( ).

Integrated Networks

In July this year, Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI), the world’s largest ship building company announced the development of a proprietary ICT technology called the Integrated Smart Ship Solution (ISSS). The company said that this technology could provide smart management of ships while integrating its navigation functions to make it more economical and reliable. ( ). Such disruptive technologies are expected to bring down annual cost of operations by as much as 6 % and therefore, is likely to be a preferred option for shipping companies. With the expected introduction of e-navigation by 2019 (http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/ Navigation/Pages/eNavigation.aspx), it is expected that smart ships and solutions like the ISSS would see a greater demand.

Age of Merchant Fleet

The WannaCry ransomware exploited inbuilt vulnerabilities in Windows systems and networks targeting Windows XP Operating systems in particular, as Microsoft Inc has discontinued security patches for the same. It came as a shock to most that the recently launched HMS Queen Elizabeth, the largest and the most modern of the Royal Navy ships still uses computers onboard that run Microsoft Windows XP (_______) to maintain compatibility with critical weapons systems software. The Equasis Statistics Report 2016, clearly shows that only around 20% of the World Merchant Fleet is less than 5 years old (_______).

Most companies are unlikely to invest substantial amounts for the upgradation of onboard systems as they would cause other compatibility issues with the machinery and control system software and would consequently render the ship more vulnerable to a cyber attack.

Centralised Management

As early as Jan 2016, Transas unveiled the next generation ‘Transas Harmonised Eco System of Integrated Solutions (THESIS). The platform is expected to provide an ecosystem that would link all stakeholders like shipping companies, ship owners and training institutions and Vessel Traffic Management nodes and enable sharing of real time data to optimise fleet resource management. In March this year, Transas announced a partnership agreement with Satcom Global to add integrated connectivity to THESIS allowing ships at sea to connect seamlessly with shore based fleet operations centres. This would mean that in the future, ships would be connected to the internet 24 X 7.

Given the rapid process of digitisation that is expected in the maritime industry, driven by prospects of reducing operating costs in an otherwise dull market, it is natural to believe that the industry would be have been prepared to take on this change and the vulnerabilities that comes with the digitised environment. But it appears it is not so.

Human Element

The NATO Defence College Foundation quoted a survey conducted by the University of Coventry titled ‘Cyber Security, The Unknown Threat at Sea 2016’, the results of which were startling. The survey was conducted for a duration of 18 months with information collected from more than 250 ship owners. Highlights of the survey are shown in Table 2.

- 67% of Company Security Officers (CSOs) within shipping companies felt ‘Cyber Security’ was NOT a serious threat to international shipping.

- 89% of CSO’s did not believe Cyber Security was their responsibility and referred issues to their IT department.

- 91% of Ship Security Officers (SSOs) questioned or interviewed believed that they did not have the knowledge, training or competencies to manage the cyber threats to the vessel.

- Crew members were given NO training at all nor was there any campaigns to raise awareness, yet 53% of CIOs stated they had IT security policies in place on their vessels.

Table 2. Extract of ‘Cyber Security, The Unknown Threat at Sea 2016’ survey.

- 91% of the surveyed Singapore companies are in the early stages of security preparedness

- 54 % of the Singaporean respondents do not have a Security Operations Centre to monitor their networks and security devices for suspicious traffic

- 49 % have not conducted any form of IT security awareness exercise

- 56 % of them do not have Security Intelligence and Event Management Systems to correlate and raise alerts for any anomalies in a timely manner.

- 40 % of Singaporean respondents either do not have incident response plans to protect the companies’ networks and critical data in the event of a cyber-attack.

- 33 % of them practise their incident response plans.

- 33 % of the Singapore companies require all members of the organisation—from the CEO down—to take part in IT security awareness training.

- 75 % do not have a dedicated IT security budget and planning process.

- 32 % having security support only during work hours, and 25 percent only during the work week.

Table 2. Extract of ‘Quann IT Security End User Study 2017’

One would be led to believe that the dismal preparedness is limited to the maritime industry alone. However, that’s not true. In a recent study conducted by Quann[1] and IDC[2] and published in end July 17, majority of Singapore organisations were not adequately prepared to handle cyber security and intrusion while believing that cyber security was and important issue and were engaging with IT Security experts for it. Highlights of the study are in Table ….

As can be seen, while organisations do admit the looming threat from a cyber-attack, and take steps to prepare their organisation for the eventuality, majority is just lip service and does nothing to mitigate the risks. With the scale of the threat rising, the dangers posed are also rising exponentially and the pace that the industry is currently adopting may not be sufficient.

A Potential Time Bomb – Possible Scenarios

It is clearly evident that while the maritime industry is undergoing a fast pace automation transformation, the awareness and the preparedness of the industry leaves a lot to be desired. In a 2014 report, it was estimated that almost 1.9 billion dollars ( ) would be spent by the Oil and Gas Industry due to cyber-attacks. In another report, the UK government estimated that Oil and Gas companies already spend around 400 million pounds a year due to cyber-attacks ( ). Similar data on the maritime industry is not readily available. Unjustifiably low cyber-attacks in the maritime industry in comparison to the global trends could be a red flag in itself and point to companies under-reporting disruptions and cyber-attacks for fear of alarming investors, driving up insurance premiums or simply getting under the regulators spotlight. It could also mean that the industry is currently out of the radar of cyber criminals / tech savvy Jihadis but once the vulnerability of the industry and the potential for higher returns is identified (like piracy in 2008), it could be the next time bomb waiting to explode.

Surprisingly, the current narrative on cyber threats to the maritime industry seems to be a conflicting mash of opinions. While experts refer to the other major cyber breaches in the financial and industrial sectors to highlight the serious of the looming threat, when it comes to possible scenarios in the maritime domain, they limit themselves to AIS data manipulation or GPS spoofing. While these may only be some of the symptoms, to use these as a benchmark would be a grave underestimation of the potential damage that a serious cyber-attack can cause. I have examined a few possible scenarios and likely motivations that may be possible in case of a serious cyber-attack. Needless to say, the mind of the perpetrator will always be more willing and capable top conjure up any combination of possible action plans.

Ransom

As has been discussed earlier in this section regarding the ‘WannaCry’ and the ‘Petya’ ransomware attack in 2017, ransom seems to be the single biggest incentive for a cyber-attack on various businesses in the maritime industry. Be it gaining control the machinery and navigation of a crude tanker to decapacitate or hijack it, rendering an oil rig inoperable or encrypting the container details of a Ultra Large Container Vessel (ULCV) (a capacity of 18,270 TEU), CAPESIZE or CHINAMAX, the resultant delays, extended turnaround times and logistic chaos would make it a very lucrative target. Unlike a ransomware attack which is wide spread, targeted attacks would cripple the operations of a multinational company and forcing the company to pay the ransom, which would be, in all likelihood, a fraction of the operating losses and the loss of market value that the company would face in the period required to recover from the attack. The industry is already acquainted with settling ransom demands away from the limelight, due to its tryst with Somali piracy since 2008 and it may, therefore, prove to be an easy lure for the cyber criminals.

Media Headlines

In the 1970s and 1980s, terrorist and other self-proclaimed political outfits hijacked planes and held people as hostage to just garner the world attention (https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/pubs/fs/5902.htm). With political turmoil rife throughout the world, and the war against ISIS at its peak in the Middle East, the possibility of disgruntled elements remotely hijacking ships and port facilities, just to make the headlines around the world cannot be ruled out. As Dr. Alec Coutroubis stated in his interview, the only reason the Jihadi outfits from the Middle East and South East Asia have still not turned to the maritime domain to forward their cause is due to their cultural aversion to things maritime.

Business Strategy or Financial / Market manipulation

In a recent incident in the Black Sea in June 2017, more than 20 ships encountered erroneous GPS signals. This incident was widely reported and documented although the cause has not yet been identified. It is presumed that Russia was behind the spoofing incident, given their often-declared capability to jam GPS receivers. The matter came to the notice of mariners through a safety alert from the US Maritime administration that initially reported GPS interference. (https://www.marad.dot.gov/msci/alert/2017/2017-005a-gps-interference-black-sea/)

Vessels were advised to exercise caution as some ships reported that GPS displayed their position on land and others reported their position 25 nm from the position they were adrift in. Though the exact motivation for causing such an interference is not understood, it is likely that it could be an attempt by Russia to encourage ships to shift to the Russian GPS system (GLONASS) or Chayka, the Loran terrestrial navigation system.

Further, disruption caused by cyber-attacks on maritime infrastructure, both at sea or in harbor can be used as a business manipulative tool to bring down the price of acquisition / takeover, adversely affect the market capitalization or dent the credibility of a company when involved in competitive bidding for a huge contract. These are standard business ploys that are regularly used in the corporate world, which is even more easier to implement through the cyber domain, given the anonymity it offers.

Supply Chain Disruption

With 90% of global trade moving via the sea, any incident at sea or at major ports will have ripple effects on the economy of the country or the region. Needless to say, whatever be the motivation of the cyber criminals, the outcome would result in the disruption of the supply chain of crude oil / refined petroleum, essential raw materials that drive the economy of the country, infrastructure development and day to day goods. Frequent and unpredictable disruptions can also eventually affect the inflation and GDP of the companies.

Terrorism

Post the 9/11 attacks on the twin towers in 2001, it is no longer an improbability that any means may be adopted by a determined adversary to cause damage to the target country. With Islamic terrorism rising across the globe due to online indoctrination and recruitment, the terrorist organizations have successfully converted normal citizens into terror messengers. The scourge has not spared the young or the old, male or female, educated or the less aware. The resultant effect is that security agencies can no longer predict where and how the next attack will be perpetrated or what would be the level of sophistication and complexity. Also, it is an adage that every country prepares for the previous attack. Given these realities, it is only natural to assume that is only a matter of time before the terrorists identify the growing automation in the industry and the resultant increase in the vulnerabilities of the systems / networks that are required to manage the vast resources. Given the level of preparedness in the industry and by personnel onboard ships, it would be easier to breach ships at sea than company offices and port facilities. If a ship’s engineering / control systems or the navigation systems were hacked into at the time of their choosing and then went into hibernation to avoid being detected, the malware could get activated when in a congested geographical area or vital choke points like Bab el-Mandeb (http://cimsec.org/dangerous-waters-situation-bab-el-mandeb-strait/29508), or the Strait of Hormuz. Terrorists could then remotely control the ships to run amok and engineer collisions with military / nonmilitary targets (including oil rigs) and cause groundings / obstructions at major ports thereby boxing in vital military assets or resources for war waging and thereby, effectively impeding ongoing military operations. Although it may seem that there are adequate checks, balances and layered defenses in both the virtual world and at the physical level, the possibility of ‘the Swiss Cheese effect’[3] heightens the possibility of successful terrorist strike as was accomplished during the 9/11 New York attacks or the 26/11 Mumbai attacks.

Environmental Disaster

It may not seem likely that anyone may knowingly cause an environmental disaster, as everyone’s habitat will be equally affected by such an incident. However, historically, nations and criminals have been known to resort to the unlikeliest and unexpected of means to further their interests. Be it with the aim of adversely affecting the economy of a tourism dependent nation or keeping military and coastal protection forces engaged and away from conflict areas where they can be otherwise involved, causing an environmental disaster could be engineered to suit the requirements of the state / criminals. Notwithstanding the motivations of the perpetrators,

Political / State Sponsored

This may be one of the most unlikely possibilities, but one that cannot be ruled out. Like the recent incident of GPS Spoofing in the Black Sea in June 17 has been unofficially linked to the Russian government. With nations taking cyber warfare seriously and deploying vast resources to attack and im

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-cybersecurity-shipping-idUSBREA3M20820140424

Are we taking it seriously?

BIMCO

BIMCO was the first stake holder off the block which made a serious effort to address the issue of cyber threats to the maritime industry. In BIMCO’s annual conference held in Hamburg in November 2015, Maritime Cyber Security was one of the main issues discussed. In a session titled ‘Cyber Attack’, participants were shown a live demonstration of the vulnerabilities of ship’s systems and its potential to be hacked.

In a preliminary paper titled ‘The Guidelines on Cyber Security Onboard Ship Ver. 1.1’ published in February 2016, it laid out the framework by which shipping companies could tackle the looming threat of cyber-attacks. However, the document was more strategy and less on what needed to be done on ground to safeguard maritime assets. Moreover, while it clearly held the senior management of companies responsible for the cyber security issues (Anand, 2016), it would have been nearly impossible for the mariners’ onboard ships to understand the technical jargons and interpret strategy into an action plan.

BIMCO has since sent out mixed signals regarding its stand on cyber security. In Nov 2016 and then recently in June 17, it issued a repeat statement clearly stating “High level framework regulations that address cyber security are already provided by the International Safety Management code (ISM), which entered into force on 1 July 1998, and the International Ship and Port Security code (ISPS) in 2004…. Additional regulatory actions are not required because the ISPS and ISM codes are suitable regulatory frameworks for cyber security” (Petersen, 2017). Such a stand is likely to lead ship owners and organisations into complacency and thereby reduce the urgency felt to counter the possible cyber threats.

Effective response

A team, which may include a combination of onboard and shore-based personnel and/or external experts, should be established to take the appropriate action to restore the IT and/or OT systems so that the ship can resume normal operations. The team should be capable of performing all aspects of the response.

An effective response should at least consist of the following steps:

1. Initial assessment: To ensure an appropriate response, it is essential that the response team find out:

- how the incident occurred

- which IT and/or OT systems were affected and how

- the extent to which the commercial and/or operational data is affected

- to what extent any threat to IT and OT remains.

2. Recover systems and data: Following an initial assessment of the cyber incident, IT and OT systems and data should be cleaned, recovered and restored, so far as is possible, to an operational condition by removing threats from the system and restoring software. The content of a recovery plan is covered in section 7.2.

3. Investigate the incident: To understand the causes and consequences of a cyber-incident, an investigation should be undertaken by the company, with support from an external expert, if appropriate. The information from an investigation will play a significant role in preventing a potential recurrence. Investigations into cyber incidents are covered in section 7.3.

4. Prevent a re-occurrence: Considering the outcome of the investigation mentioned above, actions to address any inadequacies in technical and/or procedural protection measures should be considered, in accordance with the company procedures for implementation of corrective action.

Table 3. ‘The Guidelines on Cyber Security onboard Ships’

BIMCO has since issued an updated version of the ‘The Guidelines on Cyber Security onboard Ships’ in July 17. Primarily, the second edition has been aligned to the IMO’s ‘Guidelines on Maritime Cyber Risk Management’ recommendations and includes additional chapter on “responding to and recovering from cyber incidents” and “contingency planning”. It is aimed to address ships and their related isolated conditions and has responses for situations when the ship’s systems have been breached. It has raised the bar on the technical information provided with regards the communication between ship and shore. However, given the likelihood of limited knowledge of IT and data communication systems onboard merchant ships, it is questionable whether these non-enforceable guidelines alone can make the ship secure. To make the point, the guidelines on responding to a cyber-attack is listed in Table 2; it will be evident that it will not be easily understood by a lay mariner.

IMO

The Maritime Security Working Group met in May 2016 as part of the 96th Session of the IMO’s Maritime Safety Committee and prepared the ‘Draft Guidelines on Maritime Cyber Risk Management’. This was later published on 01 June 16 as the MSC.1/Circ.1526 – ‘Interim Guidelines on Maritime Cyber Risk Management’ (IMO, 2016) and just like the Guidelines issued by BIMCO earlier that year, gave a strategic and bird’s eye view about the cyber risk landscape while completely overlooking the specifics and urgent requirements on the ground. While broadly touching the issue, it recommends following guidelines issued by BIMCO and the ISO/IEC 27001 Standard. The ISO/IEC 27001 standard is the best-known standard in the ISO 27000 (ISO/IEC 27001, 2017) family laying out the requirements for an Information Security Management System (ISMS). While members at the session acknowledged the existence of a rising cyber threat, which was a wakeup call for the industry, it fell well short of decisive action by only issuing interim guidelines which do not mandate shipping companies to implement them. The irony of it all is that while there are strict standards for marine / environmental pollution and mariners have to be adequately qualified to handle accidents, collisions and contingencies at sea, there seems to be little acknowledgement that a cyber-attack can cause all of the mentioned disasters with no human intervention to prevent it. These interim guidelines have since been adopted vide MSC-FAL.1/Circ.3 on 05 July 2017.

After the issue of the IMO’s Interim Guideline, IMO has set the dead line for the implementation of cyber risk management into the ISM Code safety management on ships by 01 Jan 2021 (International Maritime Organisation, 2017). This was discussed during the Maritime Safety Committee (MSC), 98th session in June 17 in London. In discussions, IMO has also highlighted that the International Ship Management Code, by its nature, requires for identification of risks to the ship, personnel and the environment and to apply safe guards to it. This falls well short of the urgent action that may be needed to mitigate and counter the looming threat to ships and marine facilities.

UK Government

In the 2016 ‘National Cyber Security Strategy 2016-2021’ published by the UK Government, while identifying the potential areas which are likely to be vulnerable to cyber-attack (HM Treasury, 2016), it lists out UK’s most successful companies, data holders, media organisations, digital service providers, insurers, investors, regulators and professional advisors as being likely targets of cyber-attacks. Again, the maritime sector is conspicuous by its absence.

FireEye – Cyber Security Company

In a 2017 report by the cyber security company FireEye in which it assessed the sectors that could be targeted in 2017, the maritime sector doesn’t find a mention. However, it makes a mention that instead of targeting individual transportation units (FireEye, 2017), the future attacks will aim to attack and disable a logistic or rental fleet to scale up the ransom demands. The focus of cyber criminals and Jehadi elements may not have yet shifted to the maritime sector. This is evident from the Cyber threat map at the FireEye website that clearly gives a real time feel on the cyber-attacks that are being detected around the world. A screenshot of the same on 31 Jul 17 is shown in Figure 5, which indicates that the financial sector remains the main focus of cyber criminals.

The Maritime Cyber Risk Management Summit (in association with Norton Rose Fulbright)

The first edition of the Maritime Cyber Risk Management Summit was held on 21 June 2016. Few of the issues discussed during the Summit were “Current and emerging cyber risks facing maritime industries, What can be done to mitigate cyber risk, Latest best practices and technologies used to reduce the risks of a cyber security breach and What to do in the aftermath of a successful cyberattack”.

The second Summit was held on 20 June 2017 in London. The topics included “Topics included New and emerging maritime cyber security risks and regulation, Maritime cyber security and loss prevention, reputational risk and business interruption, The maritime industry and malware – the owner/operator perspective, Maritime Cyber Tech: the good, the bad and the ugly, Can you counter-attack a maritime cyber security attack? Cyber security health check: benchmarking your company’s ability to withstand a maritime cyber security breach, How to embed maritime cyber security awareness onshore and at sea, Maritime Cyber Security and the law and What the maritime industry can learn from other industries” (Anon, 2017).

International Ship owning and Ship Management Summit (ISSS)

One of the focus areas during the fourth International Ship owning and Ship Management Summit (ISSS) as part of the London International Shipping Week 2017 in London is the change the industry is undergoing due to the emergence of disruptive technologies.

Be Cyber Aware at Sea

In 2016, a campaign called ‘Be Cyber Aware At Sea’ was launched by JWC International[4] to help raise awareness of cyber threats and risks to ship owners and offshore energy suppliers through an industry messaging initiative which includes posters, short educational films, guidance booklets for on board crew members and a bespoke maritime cyber training programme.Finally, JWC International have designed and developed the first internationally approved ‘Maritime Cyber Security Awareness Course’ (MCSA) in conjunction with the UK lead for Cyber and Information Assurance, GCHQ. The course which can be delivered on board or at the shipping or energy companies HQ is the first of its kind and has been developed by the maritime and offshore sectors for their people.The ‘Be Cyber Aware At Sea’ initiative will be holding free workshops around the world for CSO’s, SSO’s, IT staff and seafarers in conjuction with the CSO Alliance.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/global-maritime-cyber-awareness-initiative-launched-jordan-wylie

Way ahead

While maritime cyber-security is an issue that falls outside MTI’s traditional domain, we are in a position to use our platform to raise awareness of the issues at the executive level.

Adopting good “cyber-hygiene” will dissuade opportunistic attacks and prevent accidental security compromises.

Developing and implementing such policies will require a top down approach within a company. At the most basic level a company should:

- Set strong user access controls

- Set strong network access controls

- Perform regular backups

- Keep software up to date

Training employees on how to recognize cyber-attacks and implementing policies on computer hard-ware usage, particularly the use of USB memory sticks, are further steps a company should consider.

Doing what you can to secure your networks and taking the time to integrate cyber-security into your risk management and crisis communications procedure, are the two most strategic things you can do to ensure you can respond effectively to maritime cyber-security threats and in doing so, protect your reputation as a secure service provider.

MTI Network Special Report – Maritime Cyber Security (http://www.mtinetwork.com/mtinetwork-special-report-maritime-cyber-security/)

What are best practices for protecting against ransomware?

New ransomware variants appear on a regular basis. Always keep your security software up to date to protect yourself against them.

Keep your operating system and other software updated. Software updates will frequently include patches for newly discovered security vulnerabilities that could be exploited by ransomware attackers.

Email is one of the main infection methods. Be wary of unexpected emails especially if they contain links and/or attachments.

Be extremely wary of any Microsoft Office email attachment that advises you to enable macros to view its content. Unless you are absolutely sure that this is a genuine email from a trusted source, do not enable macros and instead immediately delete the email.

Backing up important data is the single most effective way of combating ransomware infection. Attackers have leverage over their victims by encrypting valuable files and leaving them inaccessible. If the victim has backup copies, they can restore their files once the infection has been cleaned up. However organizations should ensure that backups are appropriately protected or stored off-line so that attackers can’t delete them.

Using cloud services could help mitigate ransomware infection, since many retain previous versions of files, allowing you to roll back to the unencrypted form.

References

Anand, S. (2016) BIMCO launches new Cyber Security Guidelines, www.incelaw.com, [online] Available at: http://www.incelaw.com/en/knowledge-bank/bimco-launches-new-cyber-security-guidelines (Accessed 31 July 2017).

Anon (2017) European Maritime Cyber Risk Management Summit | Home, Shipcybersecurity.com, [online] Available at: http://www.shipcybersecurity.com/index.htm (Accessed 3 August 2017).

Bateman, T. (2013) Police warning after drug traffickers’ cyber-attack – BBC News, BBC News, [online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-24539417 (Accessed 26 July 2017).

Brandom, R. (2017) Almost all WannaCry victims were running Windows 7, The Verge, [online] Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2017/5/19/15665488/ wannacry-windows-7-version-xp-patched-victim-statistics (Accessed 26 July 2017).

Brenner, B. (2017). WannaCry: the ransomware worm that didn’t arrive on a phishing hook. [Online] Naked Security. Available at: https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com /2017/05/17/wannacry-the-ransomware-worm-that-didnt-arrive-on-a-phishing-hook/ [Accessed 26 Jul. 2017].

Durden, T. (2017). Real-Time Malware Attack Map | Zero Hedge. [online] Zerohedge.com. Available at: http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2017-05-12/real-time-malware-attack-map [Accessed 26 Jul. 2017].

FireEye (2017) Questions and Answers: The 2017 Security Landscape 2017, Milpitas, California, FireEye, pg. 9, [online] Available at: https://www2.fireeye.com/WEB-RPT-2017-Cyber-Security-Predictions.html (Accessed 31 July 2017).

Freeman, C. (2013) Traffickers using hackers to import drugs into major Europe ports, Telegraph.co.uk, [online] Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/belgium/10383504/Traffickers-using-hackers-to-import-drugs-into-major-Europe-ports.html (Accessed 3 August 2017).

Geib, R., & Petrig, A. (2011). Piracy and Armed Robery at Sea (First ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Guilfoyle, D. (2009). Shipping Interdiction and the Law of the Sea (First ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

HM Treasury (2016) National Cyber Security Strategy 2016 to 2021, Cyber security, London, HM Treasury, pp. 99,100, [online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-cyber-security-strategy-2016-to-2021 (Accessed 31 July 2017).

International Maritime Organisation (2016) Interim Guidelines on Maritime Cyber Risk Management, IMO, [online] Available at: http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Security/Guide_to_Maritime_Security/Documents/MSC.1-CIRC.1526%20(E).pdf (Accessed 31 July 2017).

International Maritime Organisation (2017) Maritime Safety Committee (MSC), 98th session, 7-16 June 2017, [online] Available at: http://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/MeetingSummaries/MSC/Pages/Default.aspx (Accessed 3 August 2017).

International Maritime Organisation. (2017). Piracy Reports. Retrieved Feb 27, 2017, from http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Security/PiracyArmedRobbery/Reports/Pages/Default.aspx

ISO/IEC 27001 (2017) ISO/IEC 27001 Information security management, Iso.org, [online] Available at: https://www.iso.org/isoiec-27001-information-security.html (Accessed 31 July 2017).

Kramer, A. (2017) Ukraine Cyberattack Was Meant to Paralyze, not Profit, Evidence Shows, Nytimes.com, [online] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/28/world/europe/ukraine-ransomware-cyberbomb-accountants-russia.html (Accessed 26 July 2017).

Kraska, J., & Pedrozo, R. (2013). International Maritime Security Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Lynch, V. (2017) WannaCry Ransom Total: How Much Money Did WannaCry Make?, Hashed Out, [online] Available at: https://www.thesslstore.com/blog/ wannacry-ransom-total/ (Accessed 26 July 2017).

MarineInsight. (2017). 10 Maritime Piracy Affected Areas Around The World. Retrieved Mar 03, 2017, from http://www.marineinsight.com/marine-piracy-marine/10-maritime-piracy-affected-areas-around-the-world/

McNicholas, M. (2016). Maritime Security – An Introduction. Butterworth-Heinemann.

Microsoft (2017) Microsoft Security Bulletin MS17-010 – Critical, Technet.microsoft.com, [online] Available at: https://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/security/ms17-010.aspx (Accessed 10 July 2017).

NATO. (2014). Operation Ocean Shield. Retrieved Mar 06, 2017, from http://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_topics/141202a-Factsheet-OceanShield-en.pdf

Petersen, L. (2017) Cyber Security, Bimco.org, [online] Available at: https://www.bimco.org/about-us-and-our-members/bimco-statements/cyber-security (Accessed 31 July 2017).

Polityuk, P. and Prentice, A. (2017) Ukrainian banks, electricity firm hit by fresh cyber-attack, Reuters, [online] Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ukraine-cyber-attacks-idUSKBN19I1IJ (Accessed 26 July 2017).

FireEye (2017) Cyber Threat Map | FireEye, FireEye, [online] Available at: https://www.fireeye.com/cyber-map/threat-map.html (Accessed 31 July 2017).

Symantec Official Blog (2017) What you need to know about the WannaCry Ransomware, Symantec Security Response, [online] Available at: https://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/what-you-need-know-about-wannacry-ransomware (Accessed 26 July 2017).

Twitter (2017) actual ransom (@actual_ransom) | Twitter, Twitter.com, [online] Available at: https://twitter.com/actual_ransom (Accessed 26 July 2017).

Wagstaff, J. (2014). All at sea: global shipping fleet exposed to hacking threat. [online] Reuters. Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-cybersecurity-shipping-idUSBREA3M20820140424 [Accessed 29 Jul. 2017].

Warren, T. (2017) Microsoft issues ‘highly unusual’ Windows XP patch to prevent massive ransomware attack, The Verge, [online] Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2017/5/13/15635006/microsoft-windows-xp-security-patch-wannacry-ransomware-attack (Accessed 26 July 2017).

We Live Security (2017) New ransomware attack hits Ukraine … may be global in scope, WeLiveSecurity, [online] Available at: https://www.welivesecurity.com/2017/06/27/new-ransomware-attack-hits-ukraine/ (Accessed 26 July 2017).

Willgress, L. and Walker, P. (2017) IT expert who saved the world from ransomware virus is working with GCHQ to prevent repeat, The Telegraph, [online] Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/05/14/revealed-22-year-old-expert-saved-world-ransomware-virus-lives/ (Accessed 26 July 2017).

[1] Quann, formerly known as e-Cop, is a Singapore-based cyber security services provider and a business unit of Singapore’s leading security organisation, Certis Group.

[2] International Data Corporation (IDC) is a Chinese-owned provider of market intelligence, advisory services, and events for the information technology, telecommunications, and consumer technology markets.

[3] The Swiss cheese model of accident causation illustrates that, although many layers of defense lie between hazards and accidents, there are flaws in each layer that, if aligned, can allow the accident to occur.

[4] JWC International is a leading provider of Maritime & Offshore Cyber Security Training Solutions

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Maritime"

Maritime is something relating to the seas and oceans. The term is commonly used in nautical and seaborne trade matters. Not to be confused with “marine” which relates specifically to the seas, oceans and the life within them.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: