Addressing Operational Human Factors Issues in Aviation

Info: 4472 words (18 pages) Dissertation

Published: 16th Dec 2019

Tagged: Aviation

(“Human Factors in Aviation,” 2016)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This report has the purpose of addressing operational human factors by proposing strategies to improve the effectiveness of the Flight Crew / Cabin Crew relationship and reinforcing the trust between these two crews. Flight Operations managers had identified occurrences of Cabin Crew not passing on safety concerns or disruptive events in the cabin until after the aircraft had landed. Also, the Emergency Procedures Instructors had reported hearing that the Captain can become annoyed if the Cabin Crew tries to advise safety issues while crew rest is being utilised. Lastly, Flight Operations management has recognised negative drift between in the Flight Crew and the Cabin Crew interactions/coordination.

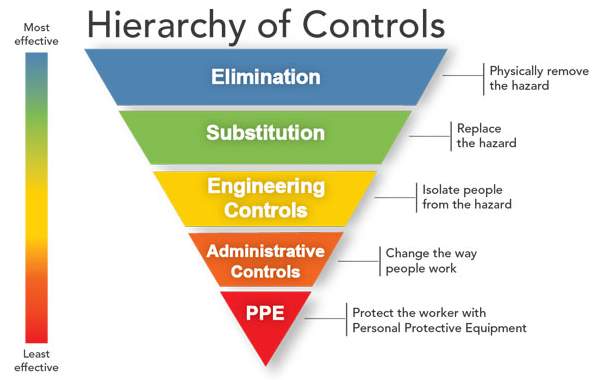

These issues have the potential to affect flight safety. Using the Hierarchy of Controls as a method for addressing these issues combined with the current training system, three strategies have been proposed. Information from journals, academic reports, government websites and peer-reviewed books have been consulted to assist in developing these three strategies.

The first strategy addressed the communication issues between the Flight Crew and Cabin Crew with administrative control proposed to assist the crews to operate on the same page. Strategy two recommended substitution as the appropriate method of resolving the issue of the captain being annoyed if he was woken during crew rest. Finally, strategy three suggested via administrative controls, that the two crews become one team by encouraging interactions beyond the flight.

These strategies highlight the need for CRM training beyond the classroom environment. Recommendations suggest the scheduling of Flight Crew and Cabin Crew together, Pre and Post flight briefings, Bi-annual training, Flight Crew to make Cabin visits during flight, specialised leadership training for Captains and On-The-Job mentoring for junior members.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary 1

- Introduction 3

- Literature Review 3

- Methodology 6

- Strategies 7

- Strategy 1 7

- Strategy 2 8

- Strategy 3 9

- Conclusion 10

- Recommendations 11

List of References 12

Appendices 13

- Introduction

The purpose of this case study report is to consider strategies that maintain or improve the relationship and trust between the Cabin Crew and Flight Crew. Safety data review meetings conducted by Flight Operations managers over the past 12 months have identified occurrences where Cabin Crew have not passed on safety concerns or disruptive events to the Flight Crew until after the aircraft had landed. Emergency Procedures Instructors have also noted that Captains are getting annoyed when the Cabin Crew wakes them while on crew rest to inform them about safety issues. The Flight Operations management, after reviewing the evidence, have determined that there has been some negative drift in Flight Crew/Cabin Crew coordination and interaction over the past 12-24 months.

This case study report will consider strategies that will address both systemic issues and individual behaviours of communication between Cabin Crew and Flight Crew. The aim of the strategies will be to improve the relationship between Cabin Crew and Flight Crew. The case study report will also consider the impacts these strategies will have on the operational costs but also the benefits of the implementing the strategies.

This paper begins with Literature Review in section 1.2 followed by Methodology in section 1.3, Strategies in section 1.4 and Conclusion in section 1.5. Finally, Recommendations are presented in section 1.6.

- Literature Review

The goal of this literature review is to give the reader an understanding of CRM/Human Factors, its evolution and highlight areas that require further study.

Crew Resource Management or CRM is “the effective use of all resources available to the flight crew, including equipment, technical / procedural skills, and the contributions of flight crew and others” with an objective of using all available resources to deliver technical and pilot skills that will ensure efficient/safe operations of an aircraft. (Johnston, McDonald, & Fuller, 1994). According to CASA (2016), “Human factors are issues affecting how people do their jobs” and “the social and personal skills, such as communication and decision making which complement our technical skills”.

Helmreich, Merritt and Wilhelm (1999) discuss the roots of CRM and the five generations of the evolution of CRM in the aviation industry. The roots of CRM can be traced back to a workshop conducted by National Aeronautics and Space Administration in 1979 with the purpose of identifying human error aspects in air crashes, specifically in the cockpit environment. The authors note that the first generation of CRM training was psychological in nature with advocation of general interpersonal behaviour but lacked definitions of appropriate behaviour in the cockpit. The second generation of CRM courses still relied upon non-aviation related concepts and “psycho-babble”. The third generation of CRM saw the broadening of CRM into other departments of airlines besides the flight deck but the authors note an unintended consequence of diluting the focus on the reduction of human errors. The fourth generation had integration of CRM into the Advanced Qualification Program. According to the authors, the fifth generation was a return to the original concept of CRM as Error Management. The authors also note that National culture needs to be customised into CRM programs.

Myers and Orndorff (2013) analyse the original concept of CRM as Error Management and how it applies in the U.S Navy but also occupations where high risk /high-stress environments exist. Myers and Orndorff’s research revealed the U.S Navy has broken CRM training into seven critical skills to assist with human-error-related accident prevention. The seven critical CRM skills used in the U.S Navy are Decision making, Assertiveness, Mission analysis, Communication, Leadership, Adaptability/Flexibility and Situational Awareness. Myers and Orndorff examined 5 non-aviation industries where human error had the potential to have catastrophic consequences. The authors discovered that most of the seven critical CRM skills taught in the U.S Navy were being applied to the non-aviation industries. The study concluded that organisational leadership with the ability to provide operational and training resources while still focusing on safety awareness and professional excellence was required for a successful CRM program.

As the CRM model expanded into non-aviation industries, it also expanded beyond the flight deck into other aviation departments such as Cabin Crew and Maintenance. Ford, Henderson and O’Hare (2013) research discuss the barriers of communication between Cabin and Flight Crew from a flight attendants’ perspective via focus groups. The focus groups highlighted the following barriers: Locked flight deck door and interphone protocols, “Sterile cockpit” SOP’s, Pre-flight briefings, Knowledge of basic aircraft terminology, Debriefings after incidents and Differences in hotels, meals and allowances. Organisational influences such as status, age, gender and power differentials between Flight Attendants and Pilots were also noted as barriers to effective communication. The recommendation to address the barriers between Flight Attendants and Flight Crews is through joint CRM training.

A study conducted by Daly and Cheng (n.d.), while similar to Ford, Henderson and O’Hare (2013), included both Cabin and Flight Crew. The study revealed that current leadership styles at an organisational level had the potential to hinder Cabin Crew reporting safety issues to Flight Crew. Some of the leadership style barriers that prevent safety-communication between Cabin Crew and Flight Crew are Status, Psychological safety, Perceived leader inclusiveness, Level of uncertainty and Power distance. Inclusiveness leadership training of Flight Crew and personnel of high status is recommended as their behaviour can suppress communication from lower status personnel. Operationally, joint Cabin/Flight pre-flight briefings are recommended to assist with psychological safety and safety-communication expectations. Joint CRM training would provide opportunities for Cabin and Flight Crews to understand each other’s roles and synchronise processes.

The literature review has revealed CRM started as a pilot error management tool that transitioned into other forms and eventually returned to its original concept. The U.S Navy identified seven critical CRM skills as a foundation for effective mission accomplishment. While CRM has been aviation focussed, other occupations where human error could have severe consequences have looked to the CRM model, and its seven critical skills, as part of an organisational training program. The CRM model has also expanded from a pilot centred error management tool into other airline departments such as Cabin Crew. This expansion revealed a communication barrier between Flight and Cabin Crew and organisational leadership deficiencies.

When the original CRM was first introduced, aircraft were smaller and travelling by air was considered a luxury. However, with the advancement of technology, aircraft have become bigger and travelling by air is considered a normal travel mode which in turn has increased the potential of safety incidents. Airlines promote safety for passengers and crew via organisational core values, however, research is needed to develop strategies to ensure that Cabin and Flight Crew have a trustworthy relationship while in operating in different sections of the aircraft to maintain an overall acceptable level of passenger and crew safety.

Therefore, the following question arises: “What strategies can an airline employ to maintain or improve Cabin Crew / Flight Crew relationships and reinforce trust between the groups while addressing systemic issues, individual behaviour, operational costs and benefits.

This case study report aims to answer the question with 3 strategies. Using the “Hierarchy of Control” (NIOSH, 2015) (refer to Appendix 1) methodology combined with the literature relating to Human Factors and Crew Resource Management will form the basis of the 3 strategies.

- Methodology

The following 3 strategies will use the “Hierarchy of Control” methodology to provide a structure for effective control measures to address systemic issues and individual behaviours within the operating environment. The Hierarchy of Control has five levels of control measures, with most effective at the top and the least effective at the bottom.

The five levels are:

- Elimination – removes the cause of danger completely.

- Substitution – controls the hazard by replacing it with a less risky way but achieving the same outcome

- Engineering – making physical changes to reduce risk i.e. redesign.

- Administrative – lessen the risk through controls such as procedures, signs, job rotation. Changing the way people work.

- Personal Protective Equipment – Protection of the worker via wearable equipment such as gloves, earplugs, goggles etc.

(Weekes, 2017)

No elimination strategies will be discussed as removable of the Cabin Crew is impracticable and would be in opposition to ICAO Standards and Recommended Practices (ICAO, 2018).

- Strategies

- Strategy 1

Problem: Flight Operations managers have identified that there have been several occurrences over the past 12 months where Cabin Crew have not passed on adequate information about safety concerns or disruptive events in the cabin until after the aircraft had landed.

Research byBienfield and Grote (2012) and Ford, Henderson and O’Hare (2014) identify the “main reason for silence among the flight attendant group was the fear of punishment, followed by feelings of futility and concern about damaging relationships”. Different workloads of Flight Crews and Cabin Crews combined with differing high/low periods have been identified as significant barriers to communication between the two crews. Adding to the communication barrier is the work environment, Flight Crew work behind a locked flight deck door (Ford, Henderson, & O’Hare, 2013) whereas Cabin Crew work in a spacious cabin and therefore each crew is unable to observe the other crew. Ford et al (2014) research also revealed other areas that contribute to non-effective communications; Flight Crews tend to be “older, generally male, highly skilled in technical and operational areas and one aircraft type rated” whereas Cabin Crew were “generally younger and of both genders, had good social skills and held more than one aircraft type rating” (organisational culture).

Strategy: Administrative Controls

Joint CRM training of both Flight Crew and Cabin Crew would assist in understanding each other’s job roles which can produce positive teamwork behaviour between the two crews and break down the organisational cultures. Effective teamwork problem-solving scenarios in a training environment would assist the Flight and Cabin Crews to “operate from the same page” (Ford, Henderson, & Hare, 2014). To encourage the Flight Crew and the Cabin Crew to operate as a team on the same page, Magerison, McCann and Davies (1988) developed the problem-solving model SADIE (S = Share information, A = Analyse, D = Decide if a problem exists, I = Implement a solution, E = Evaluate the outcome to confirm it is appropriate). The SADIE model “ensure that the problem is identified correctly and the correct drill had been implemented” (Ford et al., 2014). While joint CRM training will give participants the classroom skills, mentoring of junior employees by personnel in leadership roles will provide on the job human factors aspect of training due to the experience of the leaders and their understanding of the issue affecting how tasks are done. This on the job training will instil correct social, personal, communication and decision-making skills into the junior employees which is required within an aircrew environment (Ford et al., 2014). This strategy is designed for Flight and Cabin Crews to improve the working relationship and creating a trusting psychological safe space for Cabin Crew members to “speak up” regarding the safety or disruptive events.

Operational costs need to be considered for Flight Crews and Cabin Crews to attend joint CRM training, extra crews will need to fill the scheduling gaps however the long-term benefit of a systematic approach to CRM training, on the job human factors training via mentors and the psychological safe space that it creates will provide a productive work environment (WHO, 2018).

- Strategy 2

Problem: Emergency Procedures Instructors have reported hearing anecdotes from Cabin Crew about the Captain getting annoyed when contacted about a safety issue, if it wakes them up in crew rest.

Initially, it would seem the Cabin Crew would have to decide on whether to wake the Captain for a safety issue or ignore/deal with the safety issue themselves. Federal Aviation Regulation (2018) 91.3 states “The pilot in command of an aircraft is directly responsible for, and is the final authority as to, the operation of that aircraft.”. While the Captain is solely responsible for the flight, leadership training for Captain will assist the removal of ambiguity for Cabin Crew regarding the reporting of safety issues inflight while rest periods are being utilised.

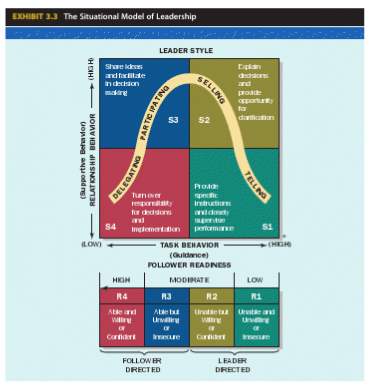

Strategy: Substitution

Leadership training for Captains regarding delegation and follower readiness. Using Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational Theory for the basis of the leadership training, it will assist the Captain to understand that “followers are the important element of the situation, and consequently, of determining effective leader behaviour” (Daft & Lane, 2016). Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational Model of Leadership can be found in Appendix 2. The Captain can delegate (S4) the First Officer(R4) as a substitute during the rest period and this will give the Cabin Crew(R2) direction when safety issues arise. “Leaders control the fear level in the organisation” and creating an “environment that enables people to feel safe” (Daft & Lane, 2016) will build a positive trusting relationship between the Flight Crew and Cabin Crew. Operational costs involved with leadership training could be absorbed into the CRM training. Benefits of leadership training for Captains will remove a barrier for Cabin Crew when it comes to safety reporting and allow Cabin Crew to perform as trained.

- Strategy 3

Problem: Flight Operations management determines that there has been some negative drift in Flight Crew / Cabin Crew coordination and interaction over the past 12 – 24 months.

Strategy: Administration

To address the negative drift between the Flight and Cabin Crew and curtailing the “us and them” culture, the following training initiatives are proposed to transition the crews into teams.

Joint CRM training will assist the crews understanding the others job roles. Moreover, Flight Crew can educate the Cabin Crew the expectations required before, during and after the flight and particularly terminology to use. Also, a basic overview of the aircraft specifications would assist in relaying information from the passenger cabin back to the flight deck.

Combined Flight and Cabin Crew pre-flight briefings would assist with crew introductions and relay flight information i.e. delays, weather, etc. A flight de-brief outlining what could be improved but also what went well in the flight.

Where possible, Flight and Cabin Crews should stay together, this includes hotels, transport to/from the airport, after flight social events etc.

Team members who have frequent contact become a unit and committed. Furthermore, as a team matures, cohesiveness via direction and purpose evolves and the team members will feel involved in something important and relevant. The team members will have an attraction to the team unit as attitude and values align. As the team achieves success and its recognised, commitment levels rise (Daft & Lane, 2016).

The operational costs of retaining Flight Crews and Cabin Crews together will be dwarfed by the benefits of the team environment via higher performance and positive organisational culture.

- Conclusion

An effective trustworthy relationship between the Flight Crew and Cabin Crew is required for continued flight safety. CRM has been developed beyond the flight deck with integration into areas such as Cabin Crews. However, recent studies show that there is still a divide between the two crews.

Using the hierarchy of control as the methodology to address the reported systemic issues and individual behaviour of Flight Crew and Cabin Crew, 3 strategies have been formulated to assist with rectifying the break down of the Flight Crew and Cabin Crew relationship.

The first strategy proposed via administration controls that the Flight Crew and the Cabin Crew engage in joint CRM training with outcomes including the understanding of the other crew’s job roles, creating a psychological safe space for crew members to voice their concerns and mentoring of junior staff to assist in desired crew behaviours.

The second strategy required specific leadership training of the Captain. Delegating and understanding follower readiness is key to lowering fear levels within a team environment. This promotes a positive trusting relationship between the Flight Crew and Cabin Crew with the desired outcome of removing barriers when Cabin Crew are reporting safety concerns in flight and the Captain is utilising crew rest.

Finally, the third strategy proposes that the two crews become one team by initiating guidelines such as staying at the same hotels during layovers and off-duty activities. Research has shown that members of a team, when their values and attitudes align, become highly committed to the team environment.

These strategies highlight the need for CRM training beyond the classroom environment. Recommendations are listed in the final section which combined with the three strategies above will provide a foundation for future training of crews.

- Recommendations

Recommendation 1:

The same personnel of the Flight Crew and Cabin Crew to be scheduled together where possible and both crews assigned to the same hotel and utilise same transport encouraging a team environment both on duty and off duty.

Recommendation 2:

Combined Flight Crew and Cabin Crew pre-flight and post-flight briefings to build trust and provide a psychological safe space regarding expectations.

Recommendation 3:

Joint CRM training for Flight Crew and Cabin Crew, training to be conducted bi-annually.

Recommendation 4:

Flight Crew to visit the Cabin Crew during flight, this will reduce the barrier of the “sterile flight deck” syndrome.

Recommendation 5:

Leadership training for Captains with the goal of minimising fear levels and subsequent ambiguity of Cabin Crew reporting safety issues in flight.

Recommendation 6:

On-The-Job mentoring of junior employees by senior staff will cement the learnt classroom skills into useful inflight skills.

LIST OF REFERENCES

Bienefeld, N., & Grote, G. (2012). Silence That May Kill: When Aircrew Members Don’t Speak Up and Why. Aviation Psychology and Applied Human Factors, 2(1), 1-10.

CASA. (2016). Human Factors. Retrieved from https://www.casa.gov.au/safety-management/landing-page/human-factors

Daft, R., & Lane, P. (2016). The Leadership Experience (7 ed.). Boston USA: Cengage

Daly, L., & Cheng, K. (n.d.). “Captain, we have a problem…” – The barriers to cabin-to-flight deck safety communication.

Ford, J., Henderson, R., & Hare, D. (2014). The effects of Crew Resource Management (CRM) training on flight attendants’ safety attitudes. Journal of Safety Research, 48, 49-56.

Ford, J., Henderson, R., & O’Hare, D. (2013). Barriers to Intra-Aircraft Communication and Safety: The Perspective of the Flight Attendants. The International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 23(4), 368-387.

Government, U. S. o. A. (2018). Part 91 – General Operatin and Flight Rules. Retrieved from https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=06cc533857cf48f8bd6e1e55e514f9c9&mc=true&node=se14.2.91_13&rgn=div8

Helmreich, R. L., Merritt, A. C., & Wilhelm, J. A. (1999). The Evolution of Crew Resource Management Training in Commercial Aviation. The International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 9(1), 19-32.

Human Factors in Aviation. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.aviationcoaching.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/human-factors-in-aviation.jpg

ICAO. (2018). Minimum Cabin Crew Requirements Retrieved from https://www.icao.int/safety/airnavigation/OPS/CabinSafety/Pages/Minimum-Cabin-Crew-Requirements.aspx

Johnston, N., McDonald, N., & Fuller, R. (1994). Aviation psychology in practice. Aldershot, Hants, England : Brookfield, Vt.: Aldershot, Hants, England : Avebury Technical, Brookfield, Vt. : Ashgate.

Margerison, C., McCann, D., & Davies, R. (1988). Air-crew Team Management Development. Journal of Management Development, 7(4), 41-54.

Myers, C., & Orndorff, D. (2013). Crew Resource Management: Not just for aviators anymore. Journal of Applied Learning Technology, 3(3), 44-48.

NIOSH. (2015). Hierarchy of Controls. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hierarchy/default.html

Weekes, J. (2017). How the hierarchy of control can help you fulfil your health and safety duties. Retrieved from https://www.healthandsafetyhandbook.com.au/how-the-hierarchy-of-control-can-help-you-fulfil-your-health-and-safety-duties/

WHO. (2018). Mental health in the workplace. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mental_health/in_the_workplace/en/

Appendices

Appendix 1

(NIOSH, 2015)

Appendix 2

(Daft & Lane, 2016)

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Aviation"

Aviation regards any activity involved in the aircraft industry or mechanical flight including flying and the design, manufacture, and maintenance of aircraft. The term “aircraft” includes such vehicles as aeroplanes, helicopters, and lighter than air craft such as hot air balloons and airships.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: