Overview and Evaluation of Saudi Arabia's Economy

Info: 8791 words (35 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Tagged: EconomicsInternational Studies

Contents

Chapter 4: The Saudi Arabia Economy

4.3 The Tenth Development Plans

Chapter 4: The Saudi Arabia Economy

Saudi Arabia is one of the most oil rich countries in the world, and the largest oil producer. The country took advantage of the competitiveness of the international market for oil, and received extremely high revenues for over 40 years. As such, the oil industry is considered to be the main engine of the country’s economic development (Albassam, 2015). Since the 1980s, the industry has contributed to half of the total Gross Domestic Product (GDP), according to the Central Department of Statistics and Information of Saudi Arabia. Although the oil industry has contributed significantly to the economic development in Saudi, relying on it has created a major problem for the economy. The non-diversified economy that has emerged has resulted in unsustainable development and a weak private sector, which contributed 10% to total GDP between 2004 and 2013 (Aldarwish et al., 2015).

Additionally, the private sector could not generate high-skilled job opportunities. Instead, the majority of job opportunities in the private sector are low-skilled and low-wage jobs that has resulted in an increase of foreign workers in this sector of up to 50% (Khorsheed et al., 2014). As around 57% of job seekers in Saudi are highly educated, they refuse to take these low-skilled jobs that do not require high academic qualifications. In addition, the private sector does not provide the necessary training programs to enhance skills and productivity to engage the local workers to the private sector (De Bel-Air, 2014). Consequently, diversifying the economy is necessary to decrease the risk of volatility and uncertainties in the international oil market that could cause problems for the economy (Walker, 2015), and to help generate suitable job opportunities in the private sector. Furthermore, a diversified economy would assist in achieving sustainable growth away from the oil industry through strengthened productivity and contribution of the private sector (Aldarwish et al., 2015).

The Saudi government have adopted policies to strengthen private sector and achieve diversification by enhance the business environment and to reform the labour market to increase the employment rate in different development plans have been issued, with the latest covering 2015-2019 (Albassam, 2015). Economic diversification has been a main target of the government in all 10-development plans, according to the Saudi Arabian government’s first development plan (1970-1975), one of three objectives was: “diversifying sources of national income and reducing dependence on oil by increasing of other productive sectors in gross domestic product” (Ministry of Economy and Planning, 2014, p.23). Even though economic diversification has been the main goal of development plans in Saudi Arabia since 1970, the result of the current analysis shows that the oil sector remains the engine driving the economy. Many reasons have been suggested to explain the government’s lack of success in diversifying the economy. Among them there are the absence of clear plan that addresses in detail the process of diversifying the economy, the government support provided to industries that are profoundly dependent on oil (e.g., petrochemical industries), the almost complete dependence of the private sector on government spending and projects, and lack of clear and specific plan support non-oil sectors (agriculture, service).

This chapter is organised as follows. First, a review of the Saudi economy, where the main features of the Saudi economy are discussed, in addition to brief outline of the main objectives of all ten Development plans. Second, the 10th Development plan (2015-2019) is discussed in term of the main features and the main issues in the Saudi economy, as well as explain entrepreneurship ecosystem in Saudi and what need to be done to support entrepreneurship and SMEs. Finally, an outlook of research case study the National Entrepreneurship Institute (NEI) and explain in more details the main programs of NEI to support entrepreneurship and SMEs.

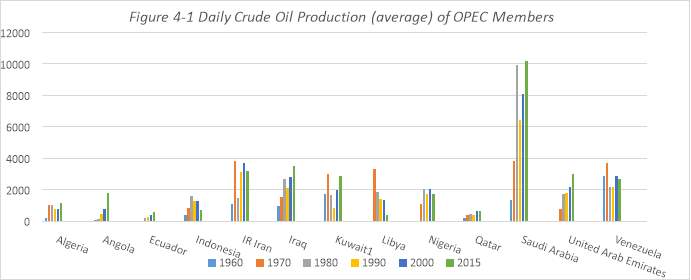

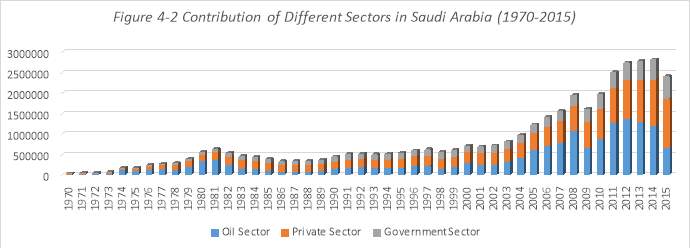

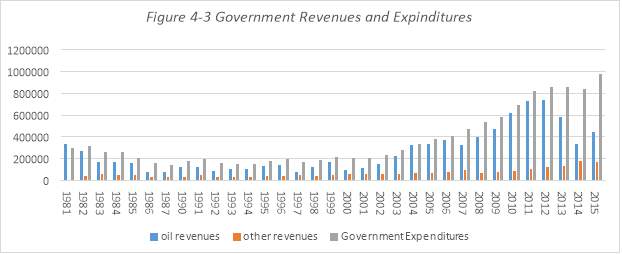

Saudi Arabia is one of the most oil rich countries in the world, and the largest oil producer, see Figure 4-1 the daily crude oil production (average) of OPEC members for the last 6 decades. Comparing with other members of OPEC, Saudi Arabia is considered the largest oil producer since 1970s, since it has the highest average of the daily crude oil production. The country took advantage of the competitiveness of the international market for oil, and received extremely high revenues for over 40 years. As such, the oil industry is considered to be the main engine of the country’s economic development (Albassam, 2015). Since the 1970s, the oil sector has contributed significantly to the total Gross Domestic Product (GDP), see Figure 4-2 contribution of different sectors to the GDP in Saudi Arabia (1970-2015). In addition, the Saudi government has relied mainly on the oil revenues to cover all the government expenditures since the 1980s, see Figure 4-3 Government revenues and expenditures. The main government expenditures cover the following:

- Human resource development;

- Transport and communication;

- Economic resource development;

- Health and social development;

- Infrastructure development;

- Municipal services;

- Defence and security;

- Public administration and other government spending; and

Government lending institutions.

Government lending institutions.

Source: OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin Report, 2016.

Source: OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin Report, 2016.

Source: Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA), Annual Statistics (SAMA, 2016).

Source: Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA), Annual Statistics (SAMA, 2016).

Source: Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA), Annual Statistics (SAMA, 2016).

Note: data for 1989, 1990 and 1991 are not available.

Although oil industry has contributed significantly to the economic development in Saudi since it contributes significantly to the GDP and it covers all the government expenditures, relying on it has created a major problem for the economy. The non-diversified economy that has emerged has resulted in unsustainable development, meaning any changes in the oil prices would impact directly on the Saudi economy, and this is what happen recently in 2015 that has resulted to major changes in the Saudi economy and policy. To explain, when the oil prices fall significantly in 2015 to reach 46.47 US $ per barrel, see Table 4-1 changes in oil prices, the oil revenues decreased and the GDP decreased as well since the oil sector’s contribution to the GDP decreased in 2015, see Figure 4-2 and 4-3.

Table 4-1 Changes in Oil prices (Arabian Light), Nominal and Real Prices

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| Oil Prices of the Arabian Light | ||||||||||

| Nominal Price (*) | 61.10 | 68.75 | 95.16 | 61.38 | 77.82 | 107.82 | 110.22 | 106.53 | 97.18 | 49.85 |

| Real Price (*) | 59.94 | 62.59 | 80.38 | 53.89 | 68.60 | 88.79 | 93.06 | 88.95 | 80.34 | 46.47 |

Source: the Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA), Annual Statistics (SAMA, 2016).

(*) Base year 2005, and the prices in US$ per Barrel.

Theoretically, changes in oil prices are expected to have two contradictory effects on the private sector and manufacturing sector, since the production cost will reduce. However, this is not the case in Saudi Arabia, where the government plays an important role in supporting manufacturing and private sector and relying on the oil export revenues in their support. Therefore, lower oil price will reduce export revenues, and the government may not be able to provide the same level of support to privet and manufacturing sector as it used to do (Mahboub and Ahmad, 2017). This has led to adopt new changes in the Saudi economy and policy such as decreasing the government expenditures for 2016 in education and militarily sectors, as well as announcing the 2030 vision in 2016 during an interview with Prince Mohammed Bin Salman.

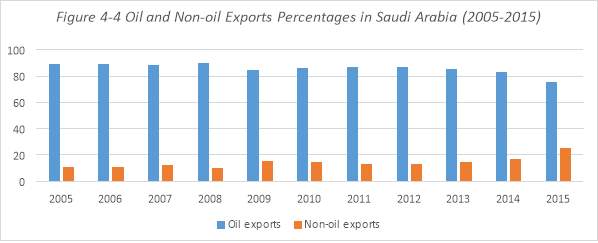

In term of diversification, Saudi Arabia needs economic diversification for at least four reasons. First, it would reduce the exposure of the economy to volatility and uncertainties in the global oil market. Second, it would help create jobs in the private sector that are needed to absorb the young and growing working-age populations into the workforce. Third, it would help increase productivity and sustainable growth. Fourth, it would help put in place the non-oil economy that will be needed many years down the road when the oil revenues start to decrease (Al-Darwish et al., 2015a). Although Saudi Arabia’s economy has evolved significantly over the past decade, as seen in Figure 4-2 the contributions of different sectors to GDP, further diversification is important to avoid risks in one-sided heavy reliance on production and export. Figure 4-4 indicates the heavy reliance on the oil exports with almost 90% in 2005, which decreased slightly during the following years to around 73% in 2015.

Source: Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA), Annual Statistics (SAMA, 2016).

Source: Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA), Annual Statistics (SAMA, 2016).

Saudi Arabia compares relatively well across several business indicators, yet challenges remain. For instance, the country has been doing well in terms of its business and infrastructure, incentives for export promotion, labour market regulation, and education. However, challenges remain in contract enforcement and resolution of company insolvencies, and in trade integration, despite export incentives (Al-Darwish et al., 2015a). In term of business climate, Saudi Arabia was ranked as the 29th most competitive economy worldwide among 138 countries according to the Global Competitive Index 2016-2017 (Schwab, 2017). Global Competitiveness Index combines 114 indicators that capture concepts that matter for productivity and long-term prosperity. These indicators are grouped into 12 pillars, these pillars are in turn organised into three groups (basic requirements, efficiency enhancers, and innovation and sophistication factors):

- Factor-driven economies: institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, health and primary education.

- Efficiency-driven economies: higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labour market efficiency, financial market development, technological readiness and market size.

- Innovation-driven economies: innovation and sophistication factors.

Figure 4-5 shows the Global competitiveness rank in three countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), these are United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. According to this report, Saudi Arabia comes at 29th, losing four places mainly because of a deteriorating macroeconomic environment following the drop-in oil prices. In details, in the basic requirements, the macroeconomic environment has the lowest rank (68); in the efficiency-driven economies, the lowest rank was in the labour market efficiency; and in the innovation-driven economies, the innovation is the lowest rank. Therefore, achieving higher diversification will require enhancing the macroeconomic environment to the basic requirements, building capacities in innovative industries and services sectors to enhance innovation and sophistication factors. Strengthening education, will be necessary, but also will be a more flexible labour market that ensures that talent is used efficiently (Schwab, 2017).(Jeddah-Chamber, 2016)

Source: Global Competitiveness Report, 2016- 2017.

Insufficient labour market can be explained by four of the main challenges in Saudi Arabia. First, a lack of competitive and fulfilling private sector jobs attractive to Saudi nationals, since the majority of job opportunities in the private sector are lower-skilled and low-wages jobs that has resulted in an increase of foreign workers in this sector up to 50% (Khorsheed et al., 2014). As around 57% of job seekers in Saudi are highly educated, they refuse to take these low-skilled jobs that do not require high academic qualifications. In addition, the private sector does not provide the necessary training programs to enhance skills and productivity to engage the local workers to the private sector (De Bel-Air, 2014).

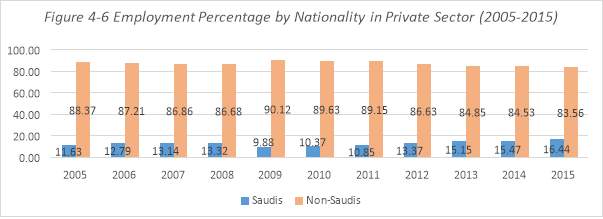

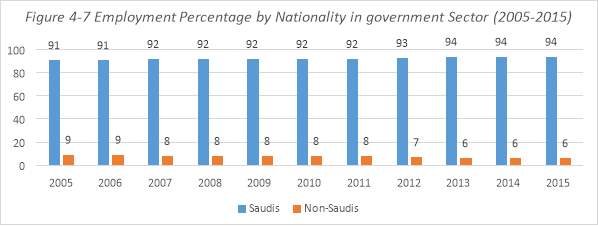

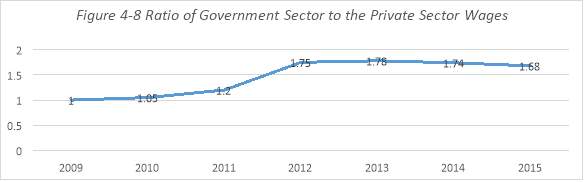

In addition, state-owned enterprises still provide most of the jobs for Saudis entering the workforce, with about two-thirds of Saudis employed in the public sector. Expanded opportunities within the private sector have not changed perceptions of these jobs. Saudi nationals continue to view public-sector work as more attractive than private employment. As a result, private sector jobs are overwhelmingly held by expatriates, as shown in Figure 4-6 while Saudis dominate the public-sector job market in Figure 4-7. As Figure 4-8 shows, the ratio of government sector to private sector wages is changing slightly, but still the government sector wages are better than private sector wages, which reinforces many Saudis’ employment perceptions. In addition, many public-sector jobs require a work week of 40 hours or less, while private sector jobs often demand six days and more than 50 hours each week. Accordingly, younger workers often prefer to stay jobless and wait for public sector vacancy. Therefore, although the number of Saudis in the private sector has been increasing, the private sector mainly relies on foreign labour, which is considered the second challenge in the labour market (MOL, 2016).

Source: Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA), Annual Statistics (SAMA, 2016).

Source: Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA), Annual Statistics (SAMA, 2016)

Source: Manpower & Employment, Talent Management, and Compensation, 2016 by Jeddah Chamber.

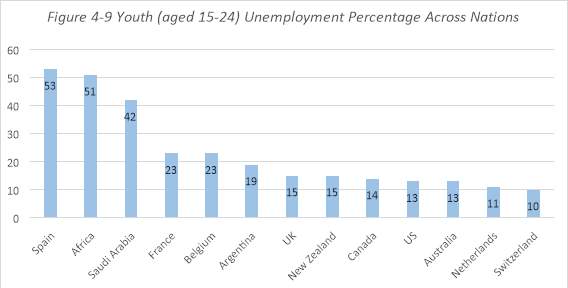

Third challenge is youth unemployment in Saudi Arabia, as annually, numerous Saudis join the workforce, but the youth of the nation is still largely unemployed. Although the total youth unemployment in 2014 was 30%, the youth unemployment among Saudis stood high as 42%. Comparing the unemployment by youth group (15-24), Saudi Arabia has a significant percentage of youth unemployment, see Figure 4-9. A major driver of the high unemployment rate is the substantial disparity between the skill set of youths and the skills required by the private sector. Thus, it is important for the government to take initiatives, to manage the expectations of its youth population by providing support in the form of training and mentorship. Additionally, improving job security and working conditions, implementing strategies to create more competitive, and fulfilling jobs, along with higher wages, would also help in making the private sector more attractive for the youth in Saudi Arabia (Jeddah-Chamber, 2016).

Source: Saudi Arabia- Manpower and Employment Talent Management and Compensation Report, by Jeddah Chamber (2016).

Saudi Arabia- Manpower and Employment Talent Management and Compensation Report, by Jeddah Chamber (2016).

Fourth, demand for labour is not being efficiently matches with the supply of labour, meaning mismatch between demand and supply especially in connecting jobs seekers to opportunities that most effectively match their skills, is considered another obstacle in the labour market in Saudi Arabia. The link between job seekers and private employers is clearly not functioning effectively. Part of the reason for lack of publicly available information is that labour market has traditionally relied on personal connections and networks (MOL, 2016, Jeddah-Chamber, 2016). Based on survey results done by Oxford Strategic Consulting of Saudi employment, not having good contacts is considered one on the significant difficulties Saudis face in finding jobs (Najat et al., 2016)

The Saudi government has adopted several development policies considering these issues within the last 10 development plans, see Table 4-2 (4 parts) for more details on the objectives of all 10 development plans, where it is obvious that diversification, employment and strengthen the private sectors are considered since the first development plan. The following section discuss the policies to tackle the fundamental issues in the Saudi economy, by focusing more on the 10th development plan (2015-2019).

Table 4-2 the 10 Economic Development Plans of Saudi Arabia (Part 1)

| Plan Name | Framework Time | Objectives |

| 1st Development Plan | 1970-1974 |

|

| 2nd Development Plan | 1975-1979 |

|

| 3rd Development Plan | 1980-1984 |

|

Source: Ministry of Economy and Planning of Saudi Arabia, 1st, 2nd, and 3rd development plans.

Table 4-2 the 10 Economic Development Plans of Saudi Arabia (Part 2)

| Plan Name | Framework Time | Objectives |

| 4th Development Plan | 1985-1989 |

|

Source: Ministry of Economy and Planning of Saudi Arabia, 4th development plan.

Table 4-2 the 10 Economic Development Plans of Saudi Arabia (Part 3)

| Plan Name | Framework Time | Objectives |

| 5th Development Plan | 1990-1994 |

|

| 6th Development Plan

7th Development Plan |

1995-1999

2000-2004 |

|

| 8th Development Plan | 2005-2009 |

|

Source: Ministry of Economy and Planning of Saudi Arabia, 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th development plans.

Table 4-2 the 10 Economic Development Plans of Saudi Arabia (Part 4)

| Plan Name | Framework Time | Objectives |

| 9th Development Plan

10th Development Plan |

2010-2014

2015-2019 |

|

Source: Ministry of Economy and Planning of Saudi Arabia, 9th and 10th development plan.

Considering the challenges in the Saudi economy, the 10th Development Plan has taken new structural policy responses toward investment and infrastructure, employment, trade, and competition and competitiveness (MEP, 2015). In term of investment and infrastructure, different tools are adopted to achieve the following objectives: 1) develop the economic, social, and environmental infrastructure; 2) stimulate economic activities and dealing efficiently with global developments; 3) develop the role of private sector; and 4) strengthening sustainable development. Regarding the first objective, the government investment spending is increased particularly in transport and health systems to meet needs of the growing population and the requirements of improving the quality of public services. In order to stimulate economic activities and dealing efficiently with global developments, private investment need to be increased, which can be achieved through:

- Expanding public-private partnerships for the implementation of infrastructure projects and the development of health, educational and social development services.

- Expanding the scale of investment banking to address the growing relative importance of medium and long-term bank credit, and support SMEs, where new laws and regulations are being considered.

- Promote private sector investment in the four Economic Cities by overcoming obstacles that may limit the efficiency of investment performance, such as reduce the rental charges of land in industrial zones and other investment projects.

- Maintaining a regulatory environment that is supportive and has stimulating effect on investment.

- Establishing 13 region-wise investment councils to encourage and develop investment in all Saudi regions, where each council will cooperate with the Saudi Arabia General Investment Authority (SAGIA) to support investment in its region, overcome obstacles, and improve the investment environment.

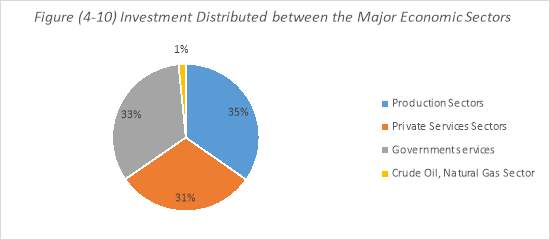

Regarding the third objective, support the development role of the private sector through developing the financial market and improving its efficiency that need new actions to be introduced. These include open up the stock market for foreign financial institutions and reduce obstacles hindering foreign investment, creating an Early Warning System (EWS) against financial crisis, introducing measures to reduce harmful speculation and enforce transparency and improve governance of the financial market. There are a number of initiatives that can serve the (EWS); one of them is the Ministry of Economy and Planning (MOEP) that prepared economic models and annual reports of the plan achievements. Finally, making sure that considerations of environment-friendly need to be in line with all investment activities in order to strengthen sustainable development. Figure (4-10) and Table (4-3) summarises targeted investment during the 10th Development Plan distributed between the major economic sectors (MEP, 2015).

Source: Ministry of Economy and Planning of Saudi Arabia, 10th Development Plan

Source: Ministry of Economy and Planning of Saudi Arabia, 10th Development Plan

Table (4-3) Investment Distributed between the Major Economic Sectors

| Economic Sectors | Total Plan Investment (%) | Yearly Growth (%) |

| A. Non-oil Sectors | 98.4% | 11.2% |

|

34.7% | 13.7% |

|

30.7% | 13% |

|

33% | 7.1% |

| B. Crude Oil, Natural Gas Sector | 1.6% | 5% |

| Total | 100% | 11.1% |

Source: Ministry of Economy and Planning of Saudi Arabia, 10th Development Plan

In term of employment, the authorities have adopted policies to increase labour force participation and reducing unemployment in the private sector through a series of supply and demand procedures to either improve the aggregate demand or increase labour force participation or expand the active labour market policies (MOL, 2016, MEP, 2015). On the demand side, three policies are considered: 1) social protection package to ensure efficiency and support labour in employment transitions; 2) increase mobility of expatriate labour to reduce the wage gap between nationals and expatriate labour force; and 3) encourage employment in the private sector to reduce unemployment rate. On the supply side, three policies are considered to increase participation of labour force among youth and women and to promote effective and efficient labour activation programs. These policies include: 1) supporting the preparation of labour force, increasing participation of female, and prioritising the incentives in the private and government sectors. For more details of the tools of each policy, see Table (4-4).

Table (4-4) Summery of Policies and Tools toward Employment (part 1)

| On the Demand Side | Policy | Tools |

| Social protection package | 1. Sanid Program: unemployment insurance for all citizens with jobs.

2. Wage Protection System: monitors the payment of wages to all workers in the private sectors. The system covers companies who employ more than 500 workers with the intention to cover all companies in the private sector. 3. Minimum Wage for workers in private and public sectors: the general minimum wage is 3000 SAR. 4. Hafiz Program: which support real job seekers financially during unemployment time. |

|

| Increasing mobility of expatriate labour | Wafeed Mobility System: allows expats from companies with poor nationalisation ratios (based on Nitaqat band) to apply to other companies without approval from existing employer, which support a reduction in the wage gap between them and national workers. | |

| Encourage employment in private sector | 1. Nitaqat Program: each company is classified in bands depending on their compliance with nationalisation requirement, where companies in high bands are given privileges.

2. On the Job Training: for youths and other new employees in the private sector occurs in the workplace under a contract between the employer and trainee. 3. Payroll Rebate: encourage private companies to increase the proportion of payroll spent of national workers. The scheme subsidisesa proportion of any increase in the total compensation paid to Saudis, with the subsidy level dependent of Nitaqat band. |

Source: Ministry of Economy and Planning of Saudi Arabia, 10th Development Plan

Table (4-4) Summery of Policies and Tools toward Employment (part 2)

| On the supply side | Policy | Tools |

| Supporting the preparation of labour force | 1. Establish 50 technical training institutes: that are incentivised based on the number of college graduates that successfully move directly into employment.

2. Establish Project Parallel: an employment readiness program for young Saudis that provides an online pre-test, e-learning modules and e-couching during work experience. |

|

| Increasing participation of female in private and public sectors | 1. Female Employment in Retail sectors: replace all male staff with women in all shops that sell women products.

2. Telework Program: as new employment channel. 3. Distance work Program and legislation: for home based business. 4. Day-care Centres Program: it seeks to reduce a key barrier to workforce participation among working mothers, childcare provision. 5. Transportation incentive: to ease the financial burden of transportation to employees’ place of employment to remove an additional barrier to workforce participation. 6. Short vocational training courses: whilst the courses are open to males and females, they are particularly intended to female. |

|

| Prioritising the incentives | 1. Taqat: a multi-channel job matching agencies that provide job seekers with evaluation, training and communication skills, and link them with suitable jo opportunities.

2. Career Education: aims to provide a lifelong service matching skills and interest with employment to make the best possible use of human resources. 3. Project Parallel: the main program parts are general employability skills and specialised skills for different types of jobs, which gives employers the confidence that the respective [person is employable and brings the right skills. |

Source: Ministry of Economy and Planning of Saudi Arabia, 10th Development Plan

In term of diversification, improvement of productivity and competiveness, and the move towards a knowledge-based society, the authorities have adopted several policies. One of these polices is a non-oil export development policy that depends on a certain mechanisms, such as establishment of export-oriented industrial zones, and adoption of short-and medium-term programs to promote productivity in the government and private sectors. Second policy is liberalisation of service sector with intention to maximise net exports of services. Further policy is a long-term strategy to implement structural reforms to enhance net exports. Finally, expanding investment in banking to address the growing relative importance of medium and long-term bank credit and support SMEs. Since SMEs play a critical role in job creation and diversification, the authorities have announced various support programs to new businesses and entrepreneurs that aims at up skilling entrepreneurs to support the development of SMEs in Saudi Arabia.

In most advanced economies, SMEs contribute as much as 70% to GDP. Saudi SMEs, however, are not yet a major contributor, accounting for less than 20% of GDP in 2015, as shown in Figure (4-11). Despite efforts to improve the business environment in Saudi, SMEs often endure unnecessary skills, capabilities and funding, financial institutions provide no more than 5% of their commercial loans to SMEs, a much lower percentage than the global average, see Figure (4-12). In addition, many entrepreneurs and investors believe that Saudi regulations and incorporation policies are inefficient and deter investment, while the legal framework does not provide enough support and transparency for resolving contract disputes and bankruptcies. Saudi Arabia rank last among advanced countries in resolving insolvency issues. Cultural attributes also can inhibit start-up business because entrepreneurs have few examples to follow. The businesses most familiar to Saudis are large government controlled enterprises (MOL, 2016). As a result, the youth who enter the workforce favour large business for their prestige, stability and promising career path (Najat et al., 2016). According to Mohammad and Ahmed (2013), The main features of Saudi culture actually deter the entrepreneurial activities, namely, favour the large-scale enterprise, favour public sector jobs, a fear of change, risk aversion, and orientation towards security. For these reasons, these features should be considered within these policies to enhance the entrepreneurial environment by creating entrepreneurial culture first. It could require encouraging people to accept changes, value differences, favour small-scale enterprise, and be more risk inclined.

By looking at the evaluation 2013 to 2015 of the Saudi Arabia entrepreneurship ecosystem (Khan, 2016). The eco at institutional level, where the different institutions, such as government and non-governmental institutions, are responsible for promoting SMEs by providing effective business support services including support and information on the following:

- How to prepare business plans;

- Organisation and dissemination of information on business formation and licensing;

- Marketing intelligence;

- Human resources;

- Real estate; and

- Innovation and facilitating cooperation.

In 2013, the soft skills development initiatives were limited and so was the effort in the teaching and training. However, the number of organisations was notable comparatively in the areas of research and creating awareness. The year 2014 witnessed the eco grow considerably, new organisations started increased and brand new services introduced. The universities understanding the requirement and obligation launched their own programs. Many organisation expanded the portfolio of their services and a number of new organisations started brand new services. More investors started to come but the environment remain hazy to their classification.

However, with in one year, a huge transformation of the eco took place. New services added, eco became filled up and almost started to provide all services. A number of more organisations filled in the gaps in the support services and expansion took place both qualitatively and quantitatively. To develop the entrepreneurship ecosystem and to be the enterprise level, where entrepreneurs and enterprise is responsible strengthening entrepreneurial and managerial skills is required. It will require practical innervations such as consulting services, access to technology and technology transfer, and incubators (Khan, 2016). See Table (4-5) for more information of all level of entrepreneurship ecosystem. Therefore, the effort to enhance the eco in Saudi Arabia need to be applied in five areas: sector development, financing, capability and resources, the business environment, and entrepreneurship culture as stated in the 9th and 10th Development Plans (MOL, 2016). To explain, the 10th development plan (MEP, 2015), the authority has several key roles as follow:

- Simplify processes by reviewing laws, regulations and processes and proposing amendment that make doing business easier.

- Provide entrepreneurs access to education and training to increase their understanding of business practices an opportunities.

- Support the creation, incubation and acceleration of SMEs.

- Improve SMEs’ access to capital assist in attracting investment.

- Spur SMEs growth by fostering the development of existing businesses.

- Support SMEs innovation with incentives for new business practices and technology.

- Provide access to government procurement by helping SMEs in bidding for government projects and tenders.

As mentioned, since the entrepreneurship ecosystem is in the institutional level, where government institutions are responsible to support entrepreneurs and SMEs, and regarding the key roles of authorities in the 9th and 10th Development Plans, the next section focus on one of the governmental institution that support entrepreneurs and SMEs, (National Entrepreneurship Institute).

Table (4-5) Levels of Entrepreneurship Ecosystems

| Level, Responsibility and Requirements | Why |

Strategic Level

|

To develop sustainable environment and to promote and then creating the entrepreneurial activity through SME Development and growth. It requires the following:

|

| Institutional Level

The following are responsible to enable enterprise:

Information on how to start a business is required. |

To promote SMEs by providing effective business support services including support and information on:

|

| Enterprise Level

Entrepreneurs and enterprise is responsible strengthening entrepreneurial and managerial skills is required |

It will require practical interventions such as:

|

Source: Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Evaluation Strategy of Saudi Arabia by Khan (2016).

National Entrepreneurship Institute (NEI) is a non-profit organisation aims to support entrepreneurship and SMEs in different regions in Saudi Arabia and to generate job opportunities to young people through support them to start their own business. Number of large companies and government initiatives have helped to establish these institutes in different regions. These include Saudi Arabian Basic Industries Corporation (SABIC), Aramco “state-owned oil company”, Saudi Telecom Company (STC), Alinma Bank, Social Development Bank, and Technical and Vocational Training Corporation. This institute plays key role in supporting SMEs through the following business support services:

- Spread knowledge and awareness toward entrepreneurship and SMEs;

- Consultation and guidance;

- Training;

- Business incubators and networks during the early stage of SMEs; and

- Easing access to different resources, such as human resources and financial.

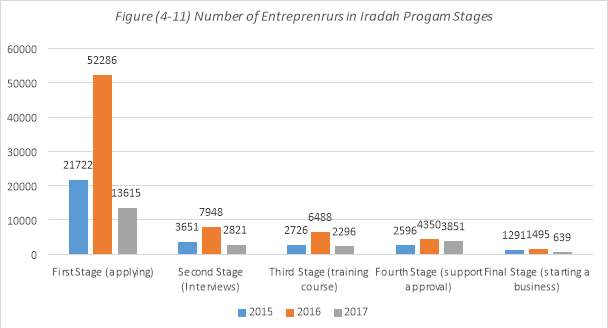

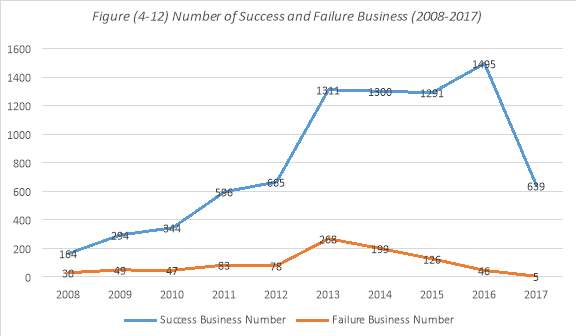

These services are introduced through five different programs. First, Entrepreneurs Program (Iradah) that provide all required services to start new business, such as preparing a business plan, develop soft skills regarding business management, and easing access to different resources during the early stage of SMEs. Entrepreneurs need to go through six stages in this program to start a new business. These stages start by applying to this program first and after that the interview stage to explain in more details their business and the support they need. Third stage is training course to train entrepreneurs how they write their business plan and manage their business. During this stage, any changes on the business regarding the support and resources they need will be sorted out. For example, if an entrepreneur need financial loan more than 300,000 SAR (80,000 US$), which the highest limit for the financial support can be given to each entrepreneurs, thus, changes on the business regarding the financial support is required or adding another source of fund. Next stage is the final approval to start a business, and finally stating the business. Figure (4-11) shows some statistics regarding these stages in Iradah Program, and Figure (4-12) shows the number of success and failure businesses since 2008 to 2017.

Source: The National Entrepreneurship Institute Accomplishment (2017)

Source: The National Entrepreneurship Institute Accomplishment (2017)

Source: The National Entrepreneurship Institute Accomplishment (2017)

(2017)

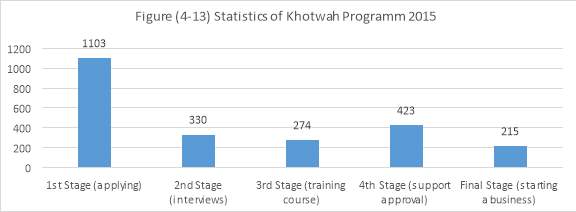

Second program is called one-step (Khotwah) is designed to support prisoners families, people with special needs and unfortunate people. These program go through the same stages of the previous program, yet the financial support in this program is lesser, 50,000-200,000 SAR (13,334-53,335 US$). Figure (4-13) shows statistics of this program stages.

Source: The National Entrepreneurship Institute Accomplishment (2017)

Third program is designed to spread knowledge and awareness of entrepreneurship and SMEs through the following activities:

- Choose a business idea course: the main aim of this spread knowledge and awareness regarding how to choose a suitable business, how to recognise the potential opportunities for good investments, and how to be an entrepreneur. In 2015, this course was arranged 500 time in different regions, where there was more than ten thousands applications to this course in different regions and more than eight thousand were accepted to attend this course in 2015.

- Induction lectures: to explain to the audience the main programs in NEI and the application process and stages. In 2015, more than four hundred induction lectures were arranged in different schools and universities in different regions, where more than thirty thousand attended these lectures.

- Participating in conferences and exhibitions: NEI participated in more than 70 conferences in different regions during 2015, in addition to present several workshops and working papers by the CEO and coordinators of NEI. Total audience for these activities were more than fifty thousands in 2015.

- Tamakan Program: this program is in cooperation between NEI and the Saudi Arabian Cultural Bureau in United States to arrange competition on writing a business plan among sponsored students in U.S. , where the best three will be supported financially by the NEI, 30,000$, 25,000$,20,000$ respectively. In addition, these three winners will have a chance to be signed in Iradah program.

Fourth program is Kab Program, which is training program aims to encourage participants to choose entrepreneurship and SMEs as professional career through educate them about the importance of SMEs and entrepreneurship and the role they can play in a society. This program contains 4 training courses and more than 200 trainers.

4.5 Conclusion

Refrences

2016. Saudi Arabia- Manpower and Employment talent Management and Compensation. Jeddah Chamber.

2017. National Entrepreneurship Institute Riyadah [Online]. Available: http://www.riyadah.com.sa/Index.aspx [Accessed 12/07/2017 2017].

AL-DARWISH, A., ALGHAITH, N., BEHAR, A., CALLEN, T., DEB, P., HEGAZY, A., KHANDELWAL, P., PANT, M. & QU, H. 2015a. Saudi Arabia : Tackling Emerging Economic Challenges to Sustain Strong Growth. USA: ‘IMF eLibrary ‘.

AL-DARWISH, M. A., ALGHAITH, N., BEHAR, M. A., CALLEN, M. T., DEB, M. P., HEGAZY, M. A., KHANDELWAL, P., PANT, M. M. & QU, M. H. 2015b. Saudi Arabia:: Tackling Emerging Economic Challenges to Sustain Growth, International Monetary Fund.

ALBASSAM, B. A. 2015. Economic diversification in Saudi Arabia: Myth or reality? Resources Policy, 44, 112-117.

DE BEL-AIR, F. 2014. Demography, migration and labour market in Saudi Arabia.

JEDDAH-CHAMBER 2016. Saudi Arabia- Manpower & Employment, Talent Management, and Compensation. Jeddah Chamber.

KHAN, M. R. 2016. Entrepreneurship ecosystem evolution strategy of Saudi Arabia. Przedsiębiorczość Międzynarodowa, 2, 67-92.

KHORSHEED, M. S., AL-FAWZAN, M. A. & AL-HARGAN, A. 2014. Promoting techno-entrepreneurship through incubation: An overview at BADIR program for technology incubators. Innovation, 16, 238-249.

MAHBOUB, A. A. & AHMAD, H. E. 2017. The effect of oil price shocks on the Saudi manufacturing sector. Economics, 5, 230-238.

MEP 1970. Saudi Arabia 1st Development Plan (1970-1974). Ministry of Economy and Planning.

MEP 1975. Saudi Arabia 2nd Development Plan (1975-1979). Ministry of Economy and Planning.

MEP 1980. Saudi Arabia 3rd Development Plan (1980-1984). Ministry of Economy and Planning.

MEP 1985. Saudi Arabia 4th development Plan (1985-1989). Ministry of Economy and Planning.

MEP 1990. Saudi Arabia 5th Development Plan (1990-1994). Ministry of Economy and Planning.

MEP 1995. Saudi Arabia 6th Development Plan (1995-1999). Ministry of Economy and Planning.

MEP 2000. Saudi Arabia 7th Development Plan (2000-2004). Ministry of Economy and Planning.

MEP 2008. Saudi Arabia 8th Development Plan (2005-2009). Ministry of Economy and Planning.

MEP 2010. Saudi arabia 9th Development Plan (2010-2014). Ministry of Economy and Planning.

MEP 2015. Saudi Arabia 10th Development Plan (2015-2019). Ministry of Economy and Planning.

MOHAMMAD, K. A. A. & AHMED, Z. 2013. The Role of Cluture on Entrepreneurship Development in saudi Arabia. Global Entrepreneurship, 4, 31.

MOL 2016. Saudi Arabia Labour Market Report 2016. 3rd Edition ed. Ministry of Labour and Social Development.

NAJAT, B.-S., ROBERT, M., SCOTT, O. & WILLIAM, S.-J. 2016. Saudi Arabia Employment Report. Online Oxford Stratigic Consulting: Oxford Stratigic Consulting.

SAMA. 2016. Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA) [Online]. SAMA. Available: http://www.sama.gov.sa/en-US/Pages/default.aspx [Accessed 12-07-2017 2017].

SCHWAB, K. 2017. The Global Competitiveness Report 2016-2017. World Economic Forum.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "International Studies"

International Studies relates to the studying of economics, politics, culture, and other aspects of life on an international scale. International Studies allows you to develop an understanding of international relations and gives you an insight into global issues.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: