A whole new world: Social media as an Election Monitoring Tool

Info: 7173 words (29 pages) Dissertation

Published: 2nd Mar 2022

Tagged: PoliticsSocial Media

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

1.1. Formal Election Monitoring vs Social Election Monitoring

1.2. Election Monitoring in Mozambique

1.3. Research question

2. Data collection strategies

2.1. Case Study

2.1.1. Employing the Case Study Strategy

2.1.2. Case Selection: Mozambique

2.2. Mixed Methods

2.2.1. Quantitative Methods

2.2.2. Qualitative Methods

3. Data analysis strategies

4. Anticipated outcomes

5. Limitations and further research

References

List of Figures

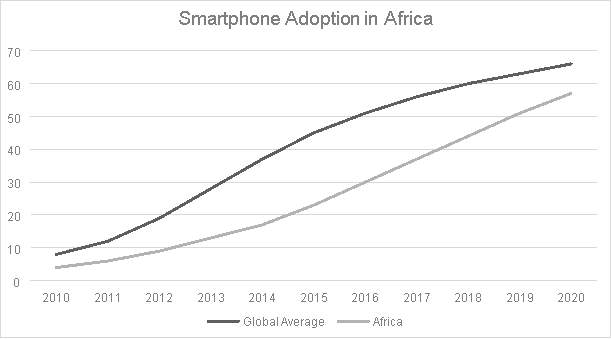

Fig. 1 – “Smartphone Adoption in Africa”

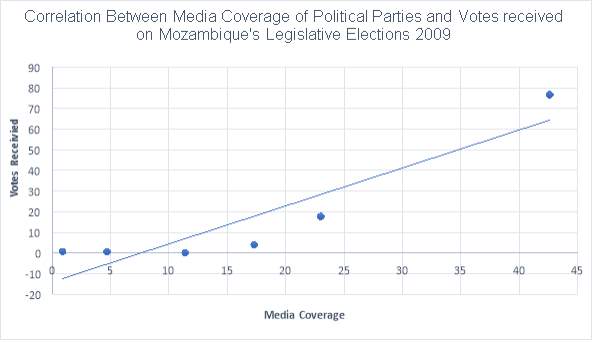

Fig. 2 – “Correlation Between Media Coverage of Political Parties and Votes received on Mozambique’s Legislative Elections 2009”

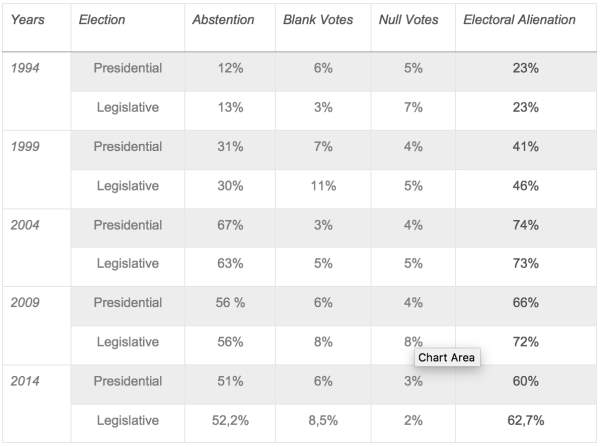

Fig. 3 – “Presidential Elections Mozambique from 1994-2014”

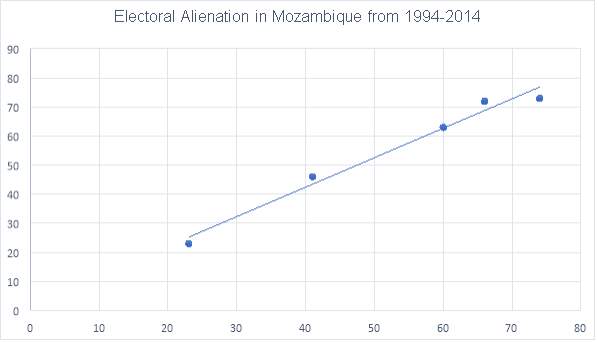

Fig. 4 – “Electoral Alienation in Mozambique from 1994-2014”

Fig. 5 – “Methods considered for analysis of social media data”

1. Introduction

Social’s media’s rapid proliferation in almost every country in the world has revealed a new potential for its use a political tool. From the US 2016 presidential elections to the events that unfolded as Arab Spring ignited mobilisation through social media from 2012 onwards; more than ever, we are aware that new media technologies are enormous platforms to quickly spread information and at a low cost, can target individuals and groups and are a powerful weapon in mobilising people. Although quite recent, social media’s impact has been studied in a western context but “remain virtually unexplored in developing regions were traditional media are scarcer, democracies are younger, and the effect of social media on politics has the potential to be quite distinct.” (Smyth, 2013: 1). Particularly in sub-Saharan Africa a lot of questions arise from the usage of social media in mobilising citizens, sharing information on political candidates and reporting incidents during elections. As recent studies of social media in elections in Nigeria and Liberia in 2011 (Smyth, 2013) have not only successfully employed tools to look at social media as a virtual space for election monitoring, but also explored a new type of election monitoring – social monitoring -, it seems relevant to expand this scope to other case studies of consolidating democracies during elections in Sub-Saharan Africa. Yet the risks of the impact of social media not being explored is only recently becoming clear as companies such as Cambridge Analytica[1] are now known to be attempting to influence the outcome of elections using user data from social media. Furthermore, foreign powers such as Russian organisations have been charged with compromising the election integrity by also trying to influence the 2016 US Presidential election results.[2] The harmful effects of the misuse of user data harvested in social media networks could be mitigated if electoral monitoring was extended to the online world.

1.1 Formal Election Monitoring vs Social Election Monitoring

African elections are usually monitored through standard procedures under international agreements to ensure a peaceful, transparent and stable electoral process. These electoral monitoring missions have been particularly important in post-conflict societies in the years immediately after a significant upheaval. Although elite habituation (Manning, 2000) has reduced the incidence of violence in elections while, the rise of social media in has brought new threats to Africans.

This study will draw a comparison between the formal election monitoring approach and the social monitoring one (Smyth, 2013). Whilst the traditional election monitoring convenes of the deployment of teams of election monitors and observers under a set of standardised training and rules and with the purpose to maintain the integrity of an electoral process (Hyde, 2011), the social monitoring approach involves the mobilization of citizens with minimal training or none with the purpose to monitor and report events and incidents during an election using digital technology, in particular mobile (Smith, 2013: 13). Both social and formal monitoring are based on common international obligations for elections (Davis-Roberts and Carroll: 2010).

There are several benefits of using social media as an election monitoring tool in contrast with more formal monitoring: cost, effectiveness, citizen’s participation, communication trends and security. Firstly, formal monitoring requires more resources allocated for deployment of trained staff, whilst social monitoring doesn’t require those resources because the citizens act as monitors. Secondly, social monitoring allows for real time and immediate incident reporting, therefore more effective monitoring and response, which is always not possible with traditional election monitoring. Thirdly, in social monitoring there is more citizen’s participation and engagement during the election since the citizen’s role changes from merely information consumers to producers. Fourthly, mobile communication and internet are a growing trend in Africa. According to GSMA Intelligence’s latest report[3], “mobile has emerged as platform of choice for creating, distributing and consuming innovative digital solutions and services in Africa”, stating that about half of Africa’s population subscribed to mobile services in 2015. The report also says that the rapid growth of mobile internet subscribers in Africa reached 300 million by 2015 and it is expected to reach 250 million more in the next five years.

Figure 1 – “Smartphone Adoption in Africa”. Source: GSMA Intelligence[4]

Lastly, formal monitoring has not yet been able to address the new challenges in African elections. Security threats in elections in consolidating democracies in Sub-Saharan Africa have been reshaped with the rise of social media. Although there has been research on the risk of violent outbreaks in African elections (Collier, 2007), the emergence of organisations seeking to manipulate social media and harvest people’s personal data has become a major challenge to the transparency and integrity of elections. Therefore, social monitoring is more fit for the new electoral landscape where the political arena is now just as much online. With the new opportunities and challenges of social media, social monitoring can help expose fraudulent behaviour and become a requirement for electoral integrity and transparency.

1.2 Election Monitoring in Mozambique

Aker, Collier and Vicente (2013) made a ground-breaking study at Mozambique about the use of SMS during the 2009 Presidential and Legislative elections. They concluded that the role of the SMS elections was key to spread messages nationally where media scarcity prevailed and that citizens used the SMS service to report incidents in polling stations throughout the election day. The practices implemented during the 2009 Mozambican Elections, such as the bulk SMS lists, the open line and the voter education leaflets, worked as a way to monitor the elections. However, the high costs and complexity of organisation of this operation made it difficult to reproduce not only in Mozambique, but in another countries. Furthermore, traditional election monitoring demands the availability of funds and teams to cover the territory to report incidents and make sure the rules of the national election committee are being followed by political parties and civil society in general.

Yet, there is also research arguing that the use of SMS for election monitoring declines when newer media is available. These findings came from story on the first crowdsourced electoral monitoring project in Mexico in 2009[5]. Its purpose was to allow a platform for citizens to act as reporters, therefore, as information producers and not only as consumers. As the Mozambique enters a quarter century of democratic rule, a new electoral cycle approaches as the country will vote for local elections on the 10th October 2018, which creates an opportunity for research on how social media in the country.

1.3 Research question

This research aims to answer a broader question within the context new political engagement through social media and the eminent growth threats that this new platform brings: to what extent do people and governments participate in politics online and can social media be an election monitoring tool in consolidating democracies where the risk of organisations surreptitiously manipulating citizens’ data is growing. Specifically, can social media be used as an electoral monitoring tool in the context of growing online political participation for Mozambique’s 2018 Local Elections and to intercept attempts to manipulate people through data vulnerabilities? This research question can be divided into three questions:

- How engaged are citizens in politics through social media?

- To what extent are organisations trying to surreptitiously manipulate people online?

- Can social media be used an electoral monitoring tool?

Recent studies (Smyth, 2013) have applied this innovative method for electoral monitoring in Sub-Saharan Africa, which required further testing.

These questions express the main purposes this research: firstly, to explore data vulnerabilities in elections – since traditional news media is government dominated, social media offers an alternative but also a new avenue for government propaganda and manipulation that is less obvious and that needs to be monitored; secondly, to confirm an era of digital citizenship – with the growth of mobile and internet in Africa, social media is rising as a two way communication and a new way for political participation.

The hypothesis for this study are as follows:

H0: Social media cannot be used as an election monitoring tool in Mozambique due to its irrelevance as a source of political engagement for citizens and the government compared to other broadcast media.

H1: Social media can be used as an electoral monitoring tool in Mozambique because citizens increasingly engage more in politics through social media, although there aren’t concerns regarding the government’s usurpation of these platforms for party propaganda.

H2: Social media can be used as an electoral monitoring tool because it represents an opportunity for the government and organisations to surreptitiously manipulate elections, however, as social media is still not widely used in urban areas in Mozambique, this won’t currently impact the election.

H3: Social media can be used as an electoral monitoring tool in the context of growing online political participation for Mozambique’s Elections and growing concerns about the governments and organisations use of these channels to surreptitiously manipulate elections.

FRELIMO has a strong influence over news media and so might invest in online propaganda as well as hiring foreign companies, so having outlets to share news has been more important than ever. Social media in election monitoring can expose this activity.

2. Data collection strategies

This study brings together different areas of research, such as Politics, International Development and Information and Communication Technology. This interdisciplinary approach is called Information Communication Technology for Development, which will be the context of this research.

2.1. Case Study

2.1.1. Employing the Case Study Strategy

The case study approach as a methodology seems to be the most appropriate choice because it enables a deeper understanding of the election period and of the political atmosphere lived during this period (Smyth, 2013). The case study method is used for greater internal validity of the study, in sacrifice of generalisation of results and conclusions (Sambanis (2004: 263) I am hoping to identify the causal mechanisms in the interaction between social media and the engagement by citizens and organisations over an election period.

Case studies can include quantitative evidence. “In fact, the contrast between quantitative and qualitative evidence does not distinguish the various research strategies”, and, as example, they say that “historical research can include enormous amount of quantitative evidence” (Yin, 1994: 14). Studying an election and the engagement of citizens during this event doesn’t mean this approach is incompatible with statistic regression and analytical data. “Case studies can be based on any mix of quantitative and qualitative evidence” (Yin, 1994: 14). For this research, this allows the employment of mix methods such as data collection and monitoring tools for analysing social media, and, simultaneously, conducting interviews for more detailed data on citizen’s perceptions on political engagement in social media.

2.1.2. Case Selection: Mozambique

Using Mill’s Method of Agreement, in comparison to previous similar election monitoring research designs in Nigeria and Liberia (Smyth, 2013), Mozambique was a suitable case study because, firstly, it is also within Sub-Saharan Africa. It would then be interesting to compare the results within the region. Secondly, having pre-existing contacts myself in Mozambique is an advantage, as well as being a Portuguese speaking country, in which I am a native speaker. Thirdly, Mozambique has a democratic rule, although it is still a consolidating democracy, with a post-civil war-based party system in which Mozambique’s Liberation Front (FRELIMO) has been dominant since the first democratic elections. This makes it politically complex and an interesting subject for research. Fourthly, Mozambique is a large territorial country composed by rural areas where traditional media is scarce, and the existing news media is used by the government for propaganda. “The Mozambican media structure and environment reflects a substantial inequality between the state owned and government aligned media and the independent media. The first are usually clearly pro-FRELIMO and controlled by the government, and the latter are more plural, but have more difficulties in accessing information from political authorities and struggle to survive with the high costs of production activity.” (Salgado, 2016: 77). This doesn’t allow for political renovation and change of the ruling power. The “media inequality” is more visible during elections as there is a strong correlation between media coverage and political parties and votes received.

Fig. 2 – “Correlation Between Media Coverage of Political Parties and Votes received on Mozambique’s Legislative Elections 2009”. Source: Data from CNE-STAE

The self-fulfilling cycle of pro-government media that plays into voter turnout is a threat to democratisation. Yet, the rise of social media has allowed for alternative ways to access and share information. And “in countries where the press has been weakened or compromised, having outlets to share news has been more important than ever”[6].

The upcoming elections in Mozambique are an opportunity to understand the issues affecting voting behaviours that lead to electoral alienation, such as abstention, blank and null votes. Electoral alienation is the absence of choice of representatives expressed by blank votes, null notes and abstention (Ramos, 2006). It often corresponds to political behaviours such as apathy or protest, motivated by political alienation, satisfaction or dissatisfaction. It has increased substantially in 24 years. Half of registered voters don’t vote and 6 in every 10 don’t have a say in elections.

Fig. 3 – “Presidential Elections Mozambique from 1994-2014”. Source: Data from CNE-STAE

Fig. 4 – “Electoral Alienation in Mozambique from 1994-2014”. Source: Data from CNE-STAE

As local elections are particularly difficult and costly to monitor through the deployment of formal or traditional election monitoring teams, social monitoring is presented as an alternative. However, it demands engagement and partnering with local NGOs, media outlets and other organisations, in replacement of professionally trained election monitors by citizens.

2.2. Mixed Methods

This research will take advantage of the use of both quantitative and qualitative methods for the analysis and integration of different types of data. Figure 5 demonstrates the methods considered for the analysis of social media data by level of automation or manual and whether it’s quantitative or qualitative data.

| Manual | Automatic | |

| Quantitative | Content Analysis | Natural Language Processing |

| Qualitative | Open/Inductive Coding | [None] |

Fig. 5 – “Methods considered for analysis of social media data”. Source: Smith, 2013: 44.

2.2.1. Quantitative Methods

In regards to quantitative methods, the data I will be using will be collected by an open-source data collection and reporting tool used for monitoring real-time events, Aggie[7]. Aggie is a web application for using social media and other resources to track incidents around real-time events such as elections or natural disasters. It was developed by Georgia Tech and the United Nations University Computing Society (UNU-CS). Today, UNU-CS continues to use Aggie to further research in a project called “Crossmedia Monitoring During Critical Events”[8] It enables monitoring of large volumes of social media traffic from multiple types of sources including Twitter, Facebook, RSS feeds. It also fetches social media content and scans it through a mix of automated and manual means, producing accessible reports. These reports are then organised in trackable incidents for further analysis and monitoring.

Aggie was chosen, firstly, due to its core abilities. Aggie is like an automated computer analysis that supplements and enhances expert human real-time reasoning and decision making, with real-time response and aligned with big data, where it supports up to 1,000 incoming reports per second. Secondly, Aggie’s underlying principle of technological neutrality, which is extremely relevant in this context. It supports content from popular social media platforms along with media originating from purpose-built systems, namely those specific to election monitoring, crises, or conflict response. Thirdly, Aggie’s successful case stories in Nigeria, Liberia and Ghana. Every election has helped improve the system and prepare it for future elections. And as an open source application, it welcomes contributes and enhancements from researchers and developers. It is also in compliance with the Declaration of Principles for International Election Monitoring.[9]

In 2016, Aggie was the software used by the Social Media Tracking Centre (SMTC)[10] in Ghana, a monitoring and response in real-time system of social media platforms such as Whatsapp, Facebook and Twitter. The purpose of the SMTC was to ensure a transparent and peaceful election by passing on information from citizens on social media, especially regarding security incidents, to the National Elections Security Taskforce, who could then take action. A research concluded that the messages collected in WhatsApp improved the effectiveness of the election monitoring (Moreno et al, 2017). These messages allowed for more incidents to be reported and escalated to the Electoral Commission and security forces (Moreno et al, 2017: 654).

2.2.2. Qualitative Methods

In regards to qualitative methods, the data I will be using will be collected in 10 semi-structured interviews carried out in Maputo and Matola. This will take place over a 2-week period in September-October 2018. These locations were chosen because they are the largest urban centres in Mozambique.

Interviews will be 45 minutes and conducted in Portuguese as the official language in Mozambique and spoken in urban areas, and later transcribed into English. There won’t be any compensation offered to participants. Although the number of interviews is not that significant due to time and resource limitations, it will allow for an insight into people’s perceptions of social media engagement during elections.

For the semi-structured interviews, there will be an interview guide containing several open questions related to how Mozambicans engage with social media during and outside election time. The semi-structured interviews allow the interviewer to follow a guide but diverge from it when relevant. For instance, this would provide a new understanding of how social media is used, how is used and other issues and concerns the interviewees address. More importantly, these interviews should allow the participants to express themselves freely. All interviews will be digitally recorded. The choice for semi-structured interviews and not unstructured is to have some points of comparison across the series of interviews.

1. Selection Criteria

Following the criteria used by Smyth (2013: 59-60), the interview participants will be selected from three groups: 3 people that are prominent social media contributors, 4 members of the Social Media Tracking Center (SMTC) set up locally for the election, and 3 traditional media professionals.

Modelling from Moreno et al (2017), a SMTC would need to be set up locally since Aggie has been designed to work within a SMTC to monitor elections. “An SMTC is a group of volunteers who gather and work collaboratively around the clock to monitor social media reports using Aggie during critical events. Generally, an SMTC is organized for an event in advance; this involves recruiting volunteers, identifying sources of reports, and building relationships with partner organizations” (Moreno et al (2017: 647). These volunteers don’t require much training or previous experience.

2. Sampling

The sampling strategies will also be modelled on Smyth (2013: 48-49). Firstly, the selection of the prominent social media contributors will be made by finding digital influencers on social media; once these are identified, they will be contacted via direct messages on their social media channels. Secondly, random members of the SMTC will be contacted through the leaders of the established teams, until all places are filled. Thirdly, in regards to the traditional media professionals, these will be contacted through a snowball sampling strategy from network contacts that are well established in the Mozambican media community.

3. Data analysis strategies

From the data collection, this research will have automated and manual analysed data. Whist the software Aggie provides an automated processing of the information harvested, the remaining data will need to be manually analysed. For the data analysed manually, the main strategy used will be thematic analysis or coding, to help pinpoint and record patterns or themes within the data collected. There will be used a mix of deductive and inductive reasonings as seen in previous studies (Smyth, 2013; Moreno et al, 2017) of analysis methods from qualitative (Miles & Huberman, 1994) to grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

The most appropriate form of data analysis for the quantitative data will be through looking at the content of the incident reports and aggregating the reports by type, giving a code to each type and making a table with how many reports per type and other issues found in this data that might be relevant – as done in a previous study (Moreno at al, 2017: 650-651), where reports were coded as “Actionable”, “Conversational” and “Non-Text”. This will allow to record the frequency of incident reports, the type of incident, incidents were action was taken, monitoring only incidents, amongst others.

The most appropriate form of qualitative analysis will be thematic analysis or coding, by linking common themes and ideas from the responses and then organising them into main categories. It will also be important to employ a comparative strategy in constantly comparing the data so that the results can be as consistent as possible. This would be done until theoretical saturation is reached and is no longer possible to extract further properties from the data.

4. Anticipated outcomes

In previous elections in Sub-Saharan Africa – Zimbabwe in 2008, Nigeria in 2011, Liberia in 2011, Ghana in 2012 and 2016 -, there has been an increase of citizen’s political engagement in social media and, simultaneously, instrumentalization of these channels by political parties and agents for targeting voters in the elections. Internet plays a key role in countries where the press has been weakened or compromised, having outlets to share news has been more important than ever, thus the new role social media in election monitoring. What about Mozambique – which results do we anticipate from this study?

4.1 How engaged are citizens in politics through social media?

In this research, I put forward the claim that social media can be used for election monitoring environment by providing a platform for open discussion and sharing information when this is not possible in traditional media channels.

Although Mozambique doesn’t yet have the same mobile coverage and internet access as some of the countries above, it is a growing trend in the country. It is likely that the data collected on social media demonstrates some levels of activity within Facebook, Twitter, RSS feed and other social media channels, and this perception is then confirmed by the data extrapolated from the interviews. With this, the null hypothesis (H0) would be rejected. As in Smyth (2013: 50), there is some expectation that the participants express some issues to do with traditional media scarcity.

Yet with the evidence presented of the increasing levels of electoral alienation, including abstention, puts another expectation on the future of social media in Mozambique. If people are disenfranchised and don’t believe in the political system, would they turn to social media to talk about it, to discuss their dissatisfaction, to mobilise and protest? Like in the uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt and Syria that led to the Arab Spring, social media, not as a cause but a tool of the revolution, was used as a facilitator for mobilisation and spread of information. Although it is not clear whether social media can overthrow a government, it certainly had an impact on the course of events (Adi, 2014: 55). The expectation is that for Sub-Saharan African countries, social media can not only be used as an escape from traditional media scarcity and censorship or propaganda from dominant parties, but also, to shape and influence the political landscape, where citizens have a voice.

4.2 To what extent are organisations trying to surreptitiously manipulate people online?

Mozambique’s multiparty democracy can be confused as a one-party rule state since FRELIMO has been the only party in power since the first democratic elections in 1994. FRELIMO has won all elections in a country where the news media in the country are responsible for an unequal media coverage of political parties that favours the ruling party.

As an outcome of this research, it’s not expected to find evidence of government propaganda online. However, there is some expectation that the interviews will reveal that Mozambicans are aware of and concerned with the risk or opportunity to be taken by the government in social media platforms. With this, H1 is rejected, although there is still the potential for social media to report and help intercept any attempts to manipulate user data. This is why we chose to confirm H3 and reject H2.

4.3 Can social media be used an electoral monitoring tool?

We predict that social media can be used to monitor elections in consolidating democracies such as Mozambique but only in the context of social monitoring and not as replacement of traditional election monitoring forms, which are still vital for the maintenance of peace and transparency of elections in post-conflict societies.

These anticipated findings mean that social media opens up a whole new world for wider communication, for citizen participation and engagement, for a more effective election monitoring and reaction to real life events at a low cost. Social media promises to revolutionise political communication and participation, whilst carrying the security and data manipulation risks that the elections in Nigeria in 2015 has exposed. However, the impacts of social media are still largely unexplored in the Sub-Saharan Africa context, as there seems that to be a Western-centric focus. If these trends are to be ignored by researchers, in a few years, the African continent will be unrecognisable as technology flourishes and revolutionises the way people live, communicate, work and do politics. This research attempts to shed light on these concerns and continue the research leads left by previous researchers.

As this research will draw attention to the role of social media in elections, it can help shape policy-making and project initiatives from international organisations on several topics: the consideration and regulation of social media as a public space; the need to preserve the freedom of the press – a governmental promise not yet delivered; the need to invest in infra-structure and digital solutions to provide internet access to the wider population and addressing the digital gap that connect some to a global network and leaves others in the dark; on the importance of data and its protection through security measures and implementation of good data practices – data not just from social media, but used by state institutions and companies.

This research design adopts a non-strict “top-down” approach, which also allows for some inductive reasoning that may lead to new and unexpected findings. The theory can be challenged if the data evidence points in a different direction. Some patterns encountered might challenge our hypothesis and help us shape new ones. Yet it is undeniable that there are expectations, theories and guides that this research will be based upon.

5. Limitations and further research

Due to its limited scope conditions, this study approach achieve internal validity which limitation of generalisability. It’s expected to understand how social media is used by citizens and organisations or governments and the causal mechanisms behind these relationships. However, what’s true in Mozambique may not be true in other countries, such as the extent of internet usage or to what extent the government controls the media. In fact, countries like Nigeria, Liberia and Ghana have watched the flourishment of social media, which is very active and dynamic, unlike in Mozambique, where it’s limited to urban centres.

Yet, although the conclusions are not necessarily generalisable, this research can be reproduced for other case studies; as a consequence, its underlying theories of social media impact can be tested and improved or challenged. This research has an innovative research design, modelled after previous studies such as Smyth (2013) and Moreno et al (2017), as it features a hybrid methodology between the human and the machine, meaning between manual and automated data collection and analysis. Software is prone to errors, which demands close monitoring to the performance of the software itself. This raises two further limitations of this study: firstly, the level of technical knowledge needed to properly implement and monitor Aggie – while this wouldn’t be a problem for this study, it poses an issue when this knowledge is scarce; the second is whether it is possible to have technological neutrality, whether Aggie’s analysis is based on assumptions and bias from the creators or monitoring agents.

In regards to feasibility, to set up the Social Media Tracking Centre, the researcher needs to liaise with local organisations prior to their arrival to recruit for the body of volunteers and for the semi-structured interviews. Also, the software used is open source and free to be used.

There are also important ethical concerns that a study of this nature might raise that need addressing. In regards to data protection, all personal data from social media platforms collected in this study won’t be shared or made public and shall remain confidential. Furthermore, the social media data will only be collected when shared publicly by users.

It will be acknowledged the impacts of the research process locally during the election and data collection and analysis. It’s not possible to make a study of this nature and not leave any influence or “foot prints”, but it will be as much discreet and less disruptive for the environment in which the research is conducted as possible.

This research hopes to welcome more researchers into the new theoretical and methodological world of social media, where people increasingly spend most of their social time; where politicians launch their political campaigns and Presidents and Prime-Ministers release statements; where data takes the value of a currency; and where platforms can be an extension for government propaganda, for censorship and for new and unexplored threats.

References

Adi, Mohammad-Munir (2014). The Usage of Social Media in the Arab Spring: The Potential of Media to Change Political Landscapes Throughout the Middle East and Africa. Collection Internet Economics / Internetokonomie Bd. 8, Berlin: Lit Verlag.

Aker, Collier and Vicente (2013). “Is Information Power? Using Mobile Phones and Free Newspapers during an Election in Mozambique”, Working Paper 328, June 2013, Center for Global Development. Accessed on 5th March 2018 at https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/is-information-power.pdf.

Carbone, Giovanni M. (2003) Emerging pluralist politics in Mozambique: the Frelimo-Renamo party system. Crisis States Research Centre working papers series 1, 23. Crisis States Research Centre, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter.

Manning, Carrie L. The politics of peace in Mozambique: post-conflict democratization, 1992-2000. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage Publications, Incorporated.

Moreno, A., Garrison, P., and Bhat, Karthik (2017). WhatsApp for Monitoring and Response WhatsApp for Monitoring and Response during Critical Events: Aggie in the Ghana 2016 Election. United Nations University Institute for Computing and Society, WiPe Paper – Social Media Studies Proceedings of the 14th ISCRAM Conference – Albi, France, May 2017. Accessed on 2nd April 2018 at http://idl.iscram.org/files/andresmoreno/2017/1498_AndresMoreno_etal2017.pdf

Sambanis, N. (2004). Using case studies to expand economic models of civil war. Perspectives on Politics, 2(2): 259-279.

Salazar O., Soto J. (2011) How to Crowdsource Election Monitoring in 30 Days: the Mexican Experience. In: Poblet M. (eds) Mobile Technologies for Conflict Management. Law, Governance and Technology Series, vol 2. Springer, Dordrecht. Accessed on 10th March 2018 at https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-007-1384-0_5#citeas.

Salgado, Susana (2016). The Internet and Democracy Building in Lusophone African Countries. London: Routledge.

Wilson, HS, Hutchinson, SA and Holzemer, WL (2002) Reconciling incompatibilities: a grounded theory of HIV medication adherence and symptom management, Qualitative Health Research 12(10): 1309-22.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

“A guide to staying online if the internet or social media gets blocked in your country” (2017), Quartz. Accessed on 16th April 2018 at https://qz.com/878823/a-guide-to-staying-online-if-the-internet-or-social-media-has-been-blocked-in-your-country/.

“Crossmedia monitoring during critical events – Aggie and the CrossMedia Tracking Centre” (2017), United Nations University Institute on Computing Society. Accessed on 10th April 2018 at http://cs.unu.edu/wp-content/uploads/Crossmedia_web.pdf.

“Declaration Of Principles For International Election Observation And Code Of Conduct For International Election Observers” (2005), United Nations. Accessed on 10th March 2018 at http://electionstandards.cartercenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Declaration-and-Code-English-revised.pdf.

“Freedom in the World 2018 – Democracy in Crisis” (2018), Freedom House. Accessed on 20th February 2018 at https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2018.

“Government reaffirms commitment to press freedom – Mozambique” (2017), Clube of Mozambique. Accessed on 1st April 2018 at http://clubofmozambique.com/news/government-reaffirms-commitment-to-press-freedom-mozambique/.

“Mozambique could be a model of internet access in Africa” (2017), Clube of Mozambique. Accessed on 19th February 2018 at http://clubofmozambique.com/news/mozambique-could-be-a-model-of-internet-access-in-africa/.

“PakVotes Social Media Experiment in Election Monitoring” (2014), United States Institute of Peace. Accessed on 5th February 2018 at https://www.usip.org/publications/2014/04/pakvotes-social-media-experiment-elections-monitoring.

“Social media has become de media in Africa” (2017), Quartz. Accessed on 16th April 2018 at https://qz.com/919213/social-media-has-become-the-media-in-africa/.

“The Mobile Economy Africa 2016” (2016), GSMA Intelligence. Accessed on 20th March 2018 at https://www.gsmaintelligence.com/research/?file=3bc21ea879a5b217b64d62fa24c55bdf&download.

“WhatsApp is now the primary platform for political trash talk in Tanzania’s election campaign” (2014), Quartz. Accessed on 9th April 2018 at https://qz.com/510899/whatsapp-is-now-the-primary-platform-for-political-trash-talk-in-tanzanias-election-campaign/.

Software: Aggie

Aggie’s Documentation: http://getaggie.org/. Last accessed on 18th April 2018.

Aggie’s Source code: https://github.com/TID-Lab/aggie. Last accessed on 16th April 2018.

[2] US intelligence agencies believe Russia tried to sway the 2016 presidential election as several people have been charged with fraudulent behaviour. https://www.justice.gov/file/1035477/download.

[3] https://www.gsmaintelligence.com/research/?file=3bc21ea879a5b217b64d62fa24c55bdf&download

[4] Idem Ibidem

[5] http://transparency.globalvoicesonline.org/project/cuidemos-el-voto

[6] https://qz.com/919213/social-media-has-become-the-media-in-africa/

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Social Media"

Social Media is technology that enables people from around the world to connect with each other online. Social Media encourages discussion, the sharing of information, and the uploading of content.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: