The 2016 Marine Life Disaster and Civil Society in Vietnam

Info: 8441 words (34 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

The 2016 Marine Life Disaster and Civil Society in Vietnam

Abstract

In April 2016, Formosa-Ha Tinh Steel Corporation, a subsidiary of the Taiwanese Formosa Plastics, became the prime suspect for the massive marine life death along a 200-kilometer coastline in Central Viet Nam. This unprecedented disaster, along with the Vietnamese government’s insufficient response to it, has sparked a rare chain of prolonged protests, as well as socio-political activism and advocacy surrounding the topics of governmental transparency and corruption. This thesis aims to explore the emergence of civil society and citizen-level socio-political activism in Viet Nam in the context of the post-disaster response to the 2016 Marine Life Disaster along the Vietnamese Central Coast. By presenting the different capacities civil societies have operated with in the aftermath of the industrial disaster, the thesis hopes to highlight the importance and resilience of citizen-level leadership in socio-political activism under the authoritarian rule of the Vietnamese Communist Party.

Keywords: civil society, informal socio-political channels, industrial disaster, Viet Nam, Formosa Plastics, activism

Introduction

Unitary authoritarian regimes like that of Vietnam have often been characterized as limited in political opportunity and socio-political freedoms. While it is true in the formal extent of the socio-political structure that freedoms of speech and of assembly are not observed, the informal channels are increasingly open for active citizens to engage politically in dissent and activism. In particular, civil society and advocacy groups have gained grounds in the Vietnamese socio-political scene, fueled by the increasing discontent among Vietnamese citizens regarding governmental conduct.

My thesis examines the resilience and different roles of civil society organizations in challenging the hegemony of the single-party rule of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, in the context of the ongoing Marine Life Disaster, which has and continues to devastate the fishing and tourism industries in the country. My argument is that in the absence of meaningful government response to crisis, civil society in Vietnam gains legitimacy in the socio-political structure by taking over the spaces traditionally inhabited by public institutions. This signals a potential for more open political opportunities and enhancement of civil liberties in Viet Nam.

This thesis is developed as manifestation of my interest in researching human rights and civil liberties in Viet Nam. Viet Nam in the popular American consciousness has been largely reduced to a cautionary tale of horrible foreign policies and model for unpopular American intervention warfare. While it is valid for Western historical thoughts on Viet Nam to take such perspectives, it is also important to address the contemporary development of an increasingly vocal and politically-aware population who is doing good work in order to address social and political issues in present-day Viet Nam.

For the purpose of this thesis, the working definition of civil society is posited as “a process of collective action that occurs and develops when organizations and individuals join together to influence power and promote positive, non-violent social change” (Wells-Dang, 2012). The basic units that comprise civil society in this thesis could include networks of organizations, informal groups and individual activists, rather than non-governmental organizations alone.

The thesis will seek to explore the expanding socio-political roles of civil society in Viet Nam firstly through engagement with existing scholarly sources. The first portion of the thesis synthesizes media reports and establishes the background of the 2016 Marine Life Disaster, which presents the context through which the position of civil society in Viet Nam is examined. The theoretical framework will also establish essential background on the formal and informal socio-political structures of the Vietnamese government and society through review of existing scholarly literature on the topic, to provide the foundation upon which the discussion of the roles of civil society in Viet Nam can be developed. Analysis of the roles of Vietnamese civil society in the context of the Marine Life Disaster will focus on the spaces civil society inhabits as humanitarian relief forces, as the media, and as legal-political actors within the informal apparatus of socio-political engagement in Viet Nam. Lastly, the thesis will address potential political implications following the formal settlement process of the disaster between Formosa Plastics Corporation and the Vietnamese government.

Literature Review

Overview of the Marine Life Disaster in Viet Nam

The first signs of the disaster washed ashore the coast of Vung Ang, Ha Tinh, one morning in April, 2016, although resident recreational and professional divers had known of the existence of a discharge pipeline in the ocean, connected to the recently-built $11 billion Hung Nghiep Formosa-Ha Tinh Steel Plant in the nearby Vung Ang Economic Zone, two years prior to the first incidents of fish death (Tong, 2016). Locals continued to sight more dead fish throughout the summer on the beaches, moving southwards with the sea currents along four different provinces: Ha Tinh, Quang Binh, Quang Tri, and Thua Thien Hue, a 200-kilometer long coastline. Within the same month, Nguyen Van Ngay, 46, a local diver employed at Nibelc – a construction subcontractor for Formosa-Ha Tinh – passed away after being hospitalized for chest pains and difficulty breathing. In the next two days, five other divers of the same company were admitted to the local hospital for similar conditions (Thanh Nien News, 2016).

The first signs of the disaster washed ashore the coast of Vung Ang, Ha Tinh, one morning in April, 2016, although resident recreational and professional divers had known of the existence of a discharge pipeline in the ocean, connected to the recently-built $11 billion Hung Nghiep Formosa-Ha Tinh Steel Plant in the nearby Vung Ang Economic Zone, two years prior to the first incidents of fish death (Tong, 2016). Locals continued to sight more dead fish throughout the summer on the beaches, moving southwards with the sea currents along four different provinces: Ha Tinh, Quang Binh, Quang Tri, and Thua Thien Hue, a 200-kilometer long coastline. Within the same month, Nguyen Van Ngay, 46, a local diver employed at Nibelc – a construction subcontractor for Formosa-Ha Tinh – passed away after being hospitalized for chest pains and difficulty breathing. In the next two days, five other divers of the same company were admitted to the local hospital for similar conditions (Thanh Nien News, 2016).

Map: The areas most affected by the mass fish death in Vietnam

(Source: The Wall Street Journal)

Facing mounting economic losses due to inability to fish and the public fear of poisoned seafood causing low market demand, coastal communities – whose livelihood has always been dependent upon the sea they live by – as well as concerned consumers and environmental activists across the nation, began calling for an official investigation into the pipeline connecting Vung Ang Economic Zone to the ocean, rejecting official statements made by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment in emergency press conferences claiming that the fish deaths were caused by “red tide”, a natural phenomenon in which toxic algal bloom accumulates in the ocean water. The central government, reluctant to incriminate one of its top foreign investors, maintained silence on the progress of any official investigation and cranked up efforts to block any information pertaining to the situation from domestic social networks. With popular sentiments concluding that the government was somehow directly involved in the conundrum and would not address citizens’ concerns adequately, a series of large protests, boycott campaigns, class-action lawsuits, and facility occupation protests pushed Formosa-Ha Tinh into admitting their complicity in the disaster in the fall of 2016 (Green Trees, 2016). Formosa Ha-Tinh has been discovered to have violated 53 environmental regulations in Viet Nam. The water off the coast of the four provinces in the immediate vicinity of the steel plant has been found to contain high levels of cyanide, phenol, and mercury – typical by-products of the “wet coking” process to cool down factory machineries, which generates wastewater containing these toxic pollutants (Marques, 2016).

It is estimated by the Vietnamese Directorate of Fisheries that the total loss in resources averaged 4.7 billion dong (or $200,000) per week, and that it would take the affected marine ecosystems along the coasts of the four most-impacted provinces a decade or more to recover to their conditions before the pollution. Furthermore, the $500 million fine that Formosa-Ha Tinh has agreed to pay as reparation fees would need to be divided among more than 65,000 citizens liable for compensation, not to mention funding government efforts to clean up and preserve the affected areas. (Directorate of Fisheries, 2016).

Political Structures in Viet Nam: Formal and Informal Pathways

Network of Power

According to James C. Scott’s exploration of contemporary Southeast Asian politics, regime political survival in contemporary Viet Nam relies on a “distinctly traditional” patron-client structure that fits into the regional theme regarding power dynamics and political vertical integration (1972). In this study,

Clientelism plays a significant role in the political processes in Viet Nam. Tromme (2016) demonstrates a correlation between Viet Nam’s economic growth since the 1986 reform (known as Doi Moi or Renovation) and the increase of clientelist-model corruption in the government at various administrative levels. As a result of liberalizing economic policies in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Viet Nam’s economy enjoyed substantial growth and poverty reduction. However, liberalized markets and economic growth could also generate many social and political challenges, such as widening income inequality, environmental degradation, and corruption. The opening of the previously planned economic model created opportunities for diversification and rent-seeking activities by public officials, who may have access to the privatization process of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and land-use licenses. This would facilitate the establishment of patronage networks on many administrative levels, with politicians using authority to privately grant property-use licenses, privatized SOEs, and foreign investment contracts to their relatives, or provincial and municipal-level officials in exchange for political support during intra-party power struggles. Whether or not specific cases of corruption were proven, this rent-seeking behavior is highly suspected by the Vietnamese general public and civil society organizations as a factor in the government’s unresponsiveness in investigating Formosa-Ha Tinh Corporation in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 Marine Life Disaster. This could signal very low public opinion and trust in the government, a sign of socio-political instability.

Pro-Democratic Sentiments and Civil Society in Vietnam

Since the takeover by the Vietnamese Communist Party in 1975, pro-democratic sentiments did not emerge in the country until the mid-1990s, when the results of a major 1986 economic reform called Doi Moi (Renovation), which transformed the nation’s centrally-planned economy to a state capitalist system with liberalized market and privatized enterprises similar to that of China’s in the 1980s, had had the chance to materialize (Wang, 2008).

Doi Moi was implemented in 1986 after the Sixth Congress of the VCP, who by then had realized and acknowledged the unpopularity and inefficiency of central-planning economy. The new plans for economic reforms included decollectivization of agricultural land through the introduction of land tenures, reallocation of resources from heavy to light industries, interest rate liberalization, encouragement for privatization, and re-establishing trade relationships with the global economy (Ong, 2004). Although the VCP was clear in new reforms mandates that the Party remains the ruling figure for the people of Viet Nam, and by systematically excluding constitutional revision from the new reforms, the VCP ensured its legal-political survival in the post-Renovation society and still adhered to Leninist configuration of the party-state (Benedickter, 2016).

Regardless of the country’s formal political configuration, a study done by the Institute of Human Studies in Ha Noi for the World Value Survey in 2006 reveals that a majority of Vietnamese responders (59.8%) across genders and age groups view democracy as “absolutely important” when asked if it is important for them to live in a country that is governed democratically. The youngest age group – 18 to 29 years old – demonstrates slightly stronger preference towards democracy than other age groups, although the difference can be deemed negligible (Institute for Human Studies, 2015).

Table 1.1: Importance of living in a country with democratic government among Vietnamese respondents across genders and age groups[1]

| Total | Sex | Age | ||||

| Male | Female | Up to 29 | 30-49 | 50 and up | ||

| Not at all important | 0.9 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.2 |

| 2 | 0.1 | N/A | 0.1 | 0.2 | N/A | N/A |

| 4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| 5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 6 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 2.7 |

| 7 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 5.4 | 5 | 5.4 | 4.2 |

| 8 | 11.8 | 9.5 | 14.1 | 10.7 | 10.4 | 15.2 |

| 9 | 14.3 | 14.1 | 14.6 | 15 | 15.1 | 12.3 |

| Absolutely important | 59.8 | 64.9 | 54.4 | 61.7 | 60.1 | 57.2 |

| Missing: Not asked by the interviewer | 0.1 | 0.1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.2 |

| No answer | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| Don’t know | 3.6 | 1.6 | 5.8 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 6.6 |

| (N) | 1,495 | 767 | 728 | 441 | 647 | 407 |

| Mean | 9.19 | 9.27 | 9.09 | 9.21 | 9.15 | 9.22 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.42 | 1.4 | 1.42 | 1.4 | 1.53 | 1.23 |

| Base mean | 1,430 | 748 | 682 | 428 | 625 | 377 |

Source: Institute of Human Studies (2015). World Value Survey (2005-2009) – Vietnam 2006. Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences, p. 58.

In the same survey, responders of the same demographics were asked to reveal their perception of how democratically Viet Nam is governed. Although, according to the data, a very small percentage responders perceive that the country is “not at all undemocratic” or generally undemocratic, less than a quarter (22%) of total responders view that their country is democratically governed. The survey was conducted after the Vietnamese government added the concept of democracy into the national slogan (which reads: “Prosperous people; strong nation; just, democratic, and civilized society”[2]) in an effort to modernize the country with political reform following the success of the 1986 economic reform Doi Moi (“Renovation”).

Table 1.2: Perception of Vietnamese responders across genders and age groups on the degree of democracy in the country’s governance[3]

| Total | Sex | Age | ||||

| Male | Female | Up to 29 | 30-49 | 50 and up | ||

| Not at all democratic | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| 3 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| 4 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.2 |

| 5 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 3.2 |

| 6 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 9.8 | 10.5 | 10.6 |

| 7 | 15.9 | 17.5 | 14.1 | 13.6 | 17.9 | 15 |

| 8 | 24.6 | 22.8 | 26.5 | 25.6 | 22.6 | 26.8 |

| 9 | 14.4 | 14.7 | 14 | 16.1 | 13 | 14.7 |

| Absolutely democratic | 22 | 24.5 | 19.4 | 21.8 | 25.2 | 17.2 |

| Missing: Not asked by the interviewer | 0.1 | 0.1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.2 |

| No answer | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| Don’t know | 5.2 | 2.9 | 7.6 | 4.3 | 3.1 | 9.3 |

| (N) | 1,495 | 767 | 728 | 441 | 647 | 407 |

| Mean | 7.95 | 7.99 | 7.91 | 7.92 | 8 | 7.91 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.72 | 1.75 | 1.69 | 1.8 | 1.73 | 1.59 |

| Base mean | 1,404 | 740 | 664 | 420 | 618 | 366 |

Source: Institute of Human Studies (2015). World Value Survey (2005-2009) – Vietnam 2006. Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences, p. 58.

The data over all show a favorable attitude towards democracy in the country, and these sentiments are increasingly reflected in the activities of urban Vietnamese, who generally enjoy higher socio-economic standings and greater access to information than their rural counterparts. These advantages keep them more engaged in national and international politics, whereas rural residents are more involved in local disputes and oversight of local Communist cadre members, who frequently make use of the uncertain land tenures to illegally seize farming lands for profitable development projects that they might have gained the contract for with rent-seeking activities (Wells-Dang, 2010). In many cases, Vietnamese citizens have become savvy in using the state machinery against itself for specific, localized campaigns. Using moral arguments, personal connections to cadre members and the argument for reciprocal benefits, the “insider-dissenter” tactic, employed especially in the Northern provinces, limits the inherent risk of going against state interests, and shows a social adaptation Vietnamese citizens have gained to be able to participate in the political play in their country (Wells-Dang, 2010).

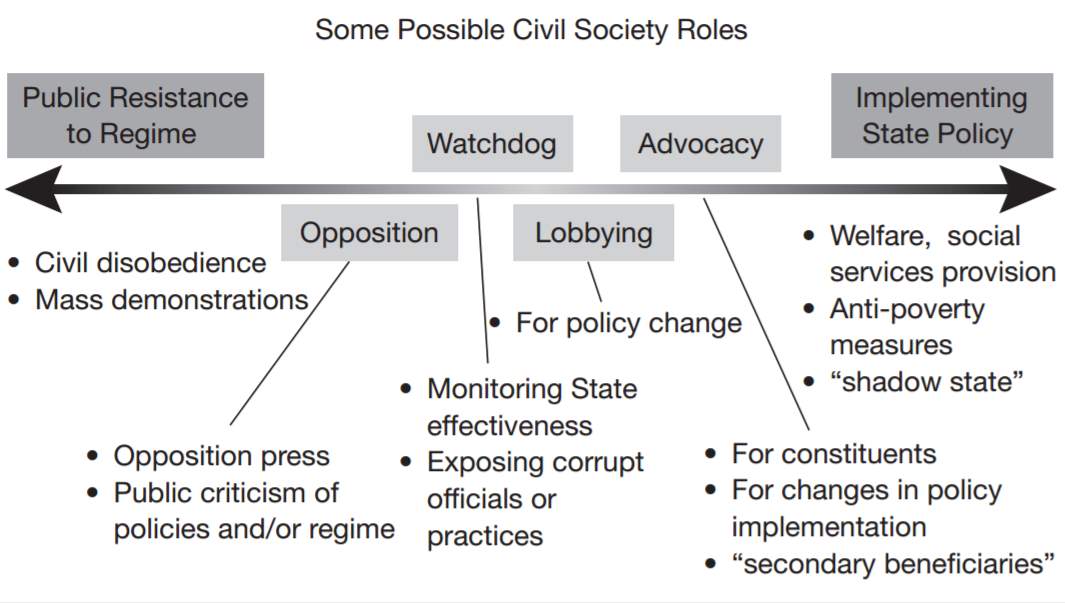

It is within this socio-political context that Vietnamese civil society emerges and operates. Viet Nam’s Marxist-Leninist model of society typically includes three main components: the party, the government and the citizens, as a well-known Vietnamese slogan states: “The party leads, the government manages, the people rule,”[4]. As such, both the government and non-governmental organizations themselves mainly view the civil society sector as partners working to support and enhance state policy. Their roles are limited to the realm of advocacy for improved state services, representation for marginalized groups through lobbying government officials for changes in policy (Thayer, 2009). Within these capacities, Vietnamese NGOs attempt to push for their agenda by negotiating and educating state officials, who make concession in order to maintain at the very least the appearance of state-society cooperation, rather than confront them directly as is often observed in the non-profit sector in Western democracies. Their activities are in direct support of existing government programs or state policy agendas.

Figure 1.1: The spectrum of civil society roles in Viet Nam

Source: Hannah, J. (2007). Local Non-Governmental Organizations in Vietnam: Development, Civil Society, and State-Society Relations. University of Washington. p.93.

However, there is a development of increasingly politically-vocal organizations, who identify more with the term civil society than NGOs. Civil societies as citizen-led organizations are becoming more associated with advocacy for liberal democratic reforms in Vietnam. They create public spaces in which the one-party rule could be challenged by the non-violent political mobilization of ordinary citizens (Wells-Dang, 2012). Many of these are simply watchdog networks of concerned citizens, but some, like the Democratic Party and Bloc 8406, represent themselves as oppositional political parties who employ the development of the Internet to engage in name-and-shame activities to expose corruption and advocate for regime reform. Members of these organizations are often scholars, researchers, journalists, and many are former Party members who have connections with informants from within the Party. These organizations operate websites and blogs that bypass the government’s censorship system to inform and mobilize fellow citizens on key socio-political issues in the country. Increased exchange of information and agendas between groups with different missions is also observed, as many groups are linking the root causes of their targeted issues to problems in the regime.

Roles of Vietnamese Civil Society in the 2016 Marine Life Disaster

Civil Society as Humanitarian Relief

The massive fish death on the Vietnamese Central Coast is estimated to have cost the economy an average of 200,000 USD per week at its peak, and severely crippled the fishing and tourism industries. Coastal communities whose livelihood had depended on the sea for generations continue to be the most affected as domestic and international consumers avoid contaminated seafood. The government’s failure to initiate relief programs to the most affected populations left the responsibility to be taken over by civil society, both domestic and overseas. For example: VOICE Vietnam, a civil society organization whose mission statement involves development of the non-governmental and non-profit sectors in Viet Nam, directly donated 20 tons of rice to the fishing communities in Ha Tinh Province, funded the year’s tuition for 155 children displaced from school by the disaster, and raised around 1000 USD for the local parish infirmary to help them better address cases of poisoning. (Green Trees, 2016).

Here we see civil society organizing around a task that has traditionally been carried out by governmental disaster relief forces. This facilitates a transfer of trust and reliance from public entities to civil society organizations, and establishes these organizations as trusted figures to the affected citizens, while the government failed to organize timely and sufficient disaster relief programs – likely as an attempt to deny the existence of a man-made industrial disaster. Gaining support from the people would also be a strategic move for the expansion of more political civil society organizations, as they can run opposite to the state in informal socio-political engagement channels with popular support.

Civil Society as the Media

The Vietnamese government does not allow for the establishment of independent press that may publish oppositions or critiques of the government’s policies. As such, politically-aware citizens typically turn away from state-sponsored sources of news to find information on socially and politically controversial matters. As such, when media blackout on the Marine Life Disaster inevitably took place, independent news sources provided by civil society organizations became the public’s link to new developments. Trust in public figures following the unresponsiveness regarding the investigation of the Marine Life Disaster has plummeted to an expressedly low level following popular sentiments about government’s incompetence, corruption, and collusion with Formosa Plastics Group to gain wealth at the expense of local population.

With the government’s silence and unresponsiveness throughout the summer regarding citizens’ demand for thorough investigation, citizen activists and scientists, along with the support of many environmental-CSOs-turned-political-advocates (such as Green Trees, For A Green Hanoi, Vietnam Path, etc.) felt the call to response to the disaster by conducting their own investigation into the matters. They demonstrated the power of uniting for a common cause, from organizing protests and free legal assistance to the fishing communities affected by the disaster, to conducting research by scouring the government’s law archives to produce comparison charts such as the table below. Green Trees, a civil society organization whose initial mission statement focuses on environmental preservation but has since become increasingly politicized, published a chart originally compiled by anti-Formosa activist and Facebooker Pham Hong Phong, showing the difference between conventionally-permissible standards of chemical by-products across multiple sectors, per the National Technical Regulation on Marine Water Quality QCVN 10-MT:2015/BTNMT, and the permissible standards for waste-water treatment procedures afforded to the Formosa Ha-Tinht according to the investment license No. 3215/GP-BTNMT. According to the numbers (Table 1.3), the levels for various toxic chemical by-products, such as cyanide and mercury, Formosa Ha-Tinh is permitted to release in their waste-water treatment procedure are consistently higher than the permissible levels indicated by the more general National Technical Regulation. For example, the cyanide level permitted to Formosa Ha-Tinh alone is calculated to be 58.5 times greater, and the amount of mercury – a known industrial neurotoxin – the steel plant is permitted to release is 11.7 times more than indicated in the national regulation.

Records such as these state-published technical regulations and investment contracts are not widely publicized or accessible to the general public, although they are government documents. Activists, especially those among legal professionals or with legally educated, have been employing more aggressively investigative approaches by going through public records or through the social capital of the network members, who may – given the relatively more lucrative economic position such connections could give them – be associated with the Vietnamese Communist Party. With the proliferation of Internet use in Vietnam, online forums and blogs become a vital tool for these civil societies to disseminate information through a network of proxies and fake accounts to prevent persecution. Information such as the figures presented in Table 1.3 has been credited as an important factor behind the mobilization of thousands of protesters across the nation in anti-Formosa, pro-environment and pro-transparency demonstrations in 2016, as it shows the government’s disregard of their own environmental regulations to attract foreign investment.

Table 1.3: Comparison of several permissible values of pollutants in seawater according to QCVN 10-MT:2015/BTNMT

| Parameter | Unit | Permissible parameters according to QCVN 10-MT:2015/BTNMT | Permissible parameters applied to Formosa according to license No. 3215/GP-BTNMT | Number of times greater that the permissible parameters according to QCVN 10-MT:2015/BTNMT | ||||

| Aquaculture and marine protection | Beach water sports | Others | Aquaculture and marine protection | Beach water sports | Others | |||

| pH | 6.5-8.5 | 6.5-8.5 | 6.5-8.5 | 5.5-9 | ||||

| Total suspended solid (TSS) | mg/l | 50 | 50 | – | 117 | 2.34 | 2.34 | – |

| Cyanide (Cn) | mg/l | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.585 | 58.5 | 58.5 | 58.5 |

| Cadmium (Cd) | mg/l | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.117 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 11.7 |

| Chrome VI (Cr6+) | mg/l | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.585 | 29.25 | 11.7 | 11.7 |

| Mercury (Hg) | mg/l | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.0117 | 11.7 | 5.85 | 2.34 |

| Total Phenol | mg/l | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.585 | 19.5 | 19.5 | 19.5 |

| Total Mineral Oil | mg/l | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 11.7 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 23.4 |

Source: Green Trees, 2016, 80; MONRE, 2015; MONRE, 2013

Civil societies involved in advocacy in the aftermath of this disaster have had particular success with making alliances with public personalities and celebrities to enhance their media presence in an otherwise state-controlled outlet. Various celebrities, like actor Thanh Loc, and talk-show host MC Phan Anh, have endorsed and popularized the call for governmental accountability in the Marine Life Disaster, becoming particularly vocal after civil society networks published images of the municipal police’s violent response to the May 8th demonstration in Ho Chi Minh City (Lan, 2016). Although most are careful with their wordings for fear of reprisals, the endorsement of public figures spreads the message to populations who don’t already engage in the discourse, or to those who don’t have access to the Internet.

Civil Society as Legal-Political Actors

Many non-state actors involved in the Marine Life Disaster started out as NGOs who were more-or-less state-conforming, but has since transitioned into more politically-active networks of actors. This phenomenon is observed as the cross-fertilization of ideas and agendas among political civil societies, and is described as a result of the interactive nature between civil society and social change, dependent on the shift in political opportunities and contention (Wells-Dang, 2012).

The legal and political mobilization done by civil societies over the course of the Marine Life Disaster played a critical role in compelling Formosa Corporation to admit their pollution practices and led to the settlement process. These civil society organizations have been involved in various forms of mobilization, from organizing demonstrations to offering free legal counseling and filing class-action lawsuits for plaintiffs, the vast majority of whom are not particularly familiar with their rights and have little means to pay for professional legal help.

Civil society was also active and successful in their outreach efforts to organize demonstrations against Formosa-Ha Tinh in Viet Nam’s largest urban centers, including Ho Chi Minh City and Ha Noi, wherein crowds of thousands gathered through the months of May to August despite frequent arrests being made by the municipal law enforcement. Green Trees, as an experienced protest organizer from the earlier Tree Movement in Ha Noi against the government’s decision to cut down thousands of trees in the urban center with the expressed purpose of urban planning reform, was among some of the most active civil society groups to organize rallies for the environment and bureaucratic transparency on May 1st, May 5th, May 15th, and June 5th of 2016 (Green Trees, 2016). Cause lawyers associated with various civil society networks also volunteered their expertise in civil defense following arbitrary arrests of activists and citizens during these protests.

The organizations involved in legal-political mobilization against Formosa-Ha Tinh have also displayed willingness to challenge the authorities on in a more formal legal arena. Twenty independent civil society groups published their petitions to the Vietnamese government demanding a full investigation of the events and calling for the end of Formosa operations in Vietnam (Green Trees, 2016). The petitions were spread widely across the Internet through these organizations’ social media pages and received massive online support. Along these lines, lawyers from Green Trees and the Vietnam Path Movement volunteered to help the fishing communities in the affected provinces file several class-action lawsuits against Formosa-Ha Tinh and the provincial authorities for obstructing investigation. As this thesis develops, more lawsuits and petitions are being filed and presented to multiple levels of the government. Formosa-Ha Tinh’s concession and apology demonstrate that the public pressure has made them choose between an immediate and prolonged loss of profit, just as it has made the Vietnamese government reconsider their options between immediate profit and regime survival. For the corporation, choosing to admit fault and entering a settlement process with the government would reduce the money they would have to pay to individual lawsuits, and ensure that their license to operate in Vietnam remains after this disaster. For the central government, publicly condemning Formosa Plastics for its violations of environmental law would distance them from the corporation, mitigating accusations of complicity and appeasing public discontent. While the general public is more-or-less satisfied with the resolution of the matter, more militant voices could be isolated. It’s a strategic cat-and-mouse game that the state and political civil society have to play in order to push their agendas.

Political Implications

Although Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc had officially concluded the investigation into the Marine Life Disaster with the famous declaration that Formosa-Ha Tinh would be shut down immediately if environmental inspectors find any sign of pollution over the permissible parameters in the future (Hoang, 2016), little else is revealed about the specific results of the investigation. How the government had handled the response to Formosa-Ha Tinh since the beginning has left little positive impression on the citizens involved, especially the fisherfolk whose lives are affected the most. It is perhaps sooner rather than later that the government of Viet Nam will need to re-invent ways to survive with full legitimacy in a country that is growing increasingly dissatisfied with its leadership.

The settlement payment of $500 million has been reached without citizen representatives at the negotiations, and has been deemed by both citizens and experts as insufficient to cover the cost of the damages and clean-up programs (Ha & Boliek, 2016a). Authority on municipal, provincial, and national administrative levels have stalled on investigation, and run public propaganda campaigns to denounce peaceful demonstration as reactionary elements paid by foreign factions to incite public disorder in Viet Nam (Nguyen, 2016b). Moreover, the use of physical force by the VCP in demonstrations and to prevent plaintiffs from bringing class-action lawsuits to the provincial courts has heightened the perception among Vietnamese citizens of the existence of a corrupt and authoritarian class of public bureaucrats and Party cadres, who prioritizes retention of profit and power over the public’s will (Green Trees, 2016).

The reality that Formosa-Ha Tinh is allowed to continue operation in Viet Nam has infuriated many activist circles, especially after allegations reemerged of continued toxic wastewater discharge after a video clip was posted on Facebook showing red streams of water pouring out of a wastewater pipeline, and of reports of red streaks of water in the sea near the steel plant, as recently as April 2017 (BBC News, 2017). So far, all government-sponsored media sources in the country have denied that the pipeline shown in the video belongs to the steel plant, and no investigation has been pursued on the topic. Meanwhile, fishing communities across the affected provinces continue to organize and pursue class-action lawsuits against Formosa-Ha Tinh for more sufficient compensation, and have been met with strong-armed suppression from the local police and the Ministry of Public Security (Ha & Boliek, 2016b).

The contingent events that follow this industrial disaster may have lasting impacts, not only on the socio-political stability of Viet Nam, but also on the legitimacy of the Vietnamese Communist Party. Many social scientists like Nguyen (2016a) and Hiep (2012) theorize that the successes of the 1986 economic liberalization reform Doi Moi re-established the legitimacy of the VCP and enabled them to rebuild the public’s trust after decades of high poverty rates plaguing their economic policies. The reforms revitalized the image of the VCP from warmongers – during the Vietnam War and the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in 1979 – to politicians and lawmakers ready to solve the country’s multifaceted crisis (Hiep, 2012). In the 1980s, troubles with the collectivization of agricultural land, high poverty rate, the ho khau system (household registration), etc. created a sense of palpable frustration towards the administration, signaling a turning of the tide when the VCP would have to choose between reform and survival. This transition from planned economy to state capitalism transformed Vietnamese society, significantly increase literacy levels and lower poverty rates, among other social reforms. For a while, the socio-economic benefits were enough legitimation for the party-state, but the after-effects of industrialization have rolled in at the start of the 21st century, bringing yet more challenges for a single-party regime to maintain legitimacy (Nguyen, 2016a). Citizens’ perception of administrative corruption, the type of activities that had toppled the Soviet republics in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, has increased in recent years. The connection between the government’s collusion with Formosa Plastics and the unresponsiveness showcased during the crisis caused by the industrial disaster cannot be proven by ethical watchdogs under the surveillance of the party-state. However, this means little to the people who feel abandoned by their own government and were violently suppressed in their efforts to demand sufficient payments.

All of this may factor into the increasing dissatisfaction that Vietnamese citizens feel towards their administration, encouraging a burgeoning defiance towards the state and how it is running the country. More and more, Vietnamese citizens are becoming activists and reclaiming the use their constitutional rights by fostering a stronger civic culture and demanding structural reforms in the government. An example would be the recently-revived call for the abolition of Article IV of the Vietnamese Constitution, which sanctions the Vietnamese Communist Party to be the only ruling party of Viet Nam. The former Deputy Director of the Central Committee of the VCP, Nguyen Dinh Huong, states in an interview with BBC Vietnamese (2016) that the movement for the abolition of Article IV is a sign that the government is “rotting themselves from the inside”, and that the central government should look to anticorruption measures in order to regain public trust and prevent the VCP establishment from collapsing on itself. Indeed, the party-state may continue to use force and implement strict crackdown on peaceful demonstration, but the Vietnamese people have realized just how far-removed the Party has become from their people, and the newly awoken activism that has emerged and unified the nation would likely continue to flourish if the state fails to address the people’s needs in a satisfactory manner.

Conclusion

It is unlikely that Vietnam will become fully democratic as pro-democracy advocates hope for. The regime itself has proven to be resilient amidst crises that had heralded the collapse of similar communist regimes in Eastern Europe. There is no way to conclude that pro-democratic movement is gaining enough traction to challenge Vietnam’s one-party state, as the government still has in possession an effective internal security force that has driven many pro-democracy activists underground. However, the merging of agendas for civil society groups and latent public discontent with the regime are giving non-state political actors more platforms to influence the public by inhabiting the spaces left open by governmental authority, and this is something that will play a crucial role in the future socio-political stability in the country.

Calls for the government to appoint non-partisan committee of inspectors to monitor Formosa-Ha Tinh for continued violations of environment standards have echoed across many activists and civil societies’ social media platforms, although the details behind clean-up plans and compensation distribution remain frustratingly vague for the hundred thousands of people affected by the event. The majority of citizens demand that Formosa-Ha Tinh cease operation on Vietnamese soil, but with $11 billion worth of foreign investment, it is highly unlikely that the Vietnamese government would yield to such a demand unless the Vietnamese people present them with a choice between profit and survival. As collective action becomes more complex, the difficulties of cohesion and sustainability increase. The challenge for Vietnamese civil societies at this juncture is the sustainability of their movement, and this would be an ongoing issue as long as the Vietnamese Communist Party retains strict internal security mechanisms to ensure party survival.

Acknowledgment

This thesis project could not have been completed without the guidance of Dr. Serena Cosgrove and Dr. Enyu Zhang of Seattle University’s International Studies Department. I would also like to express gratitude towards the civil society organizations and individual activists involved in socio-political organization for transparency and human rights in Viet Nam during and after the 2016 Marine Life Disaster.

References

Benedickter, S. (2016). Bureaucratisation and the State Revisited: Critical Reflections on Administrative Reforms in Post-Renovation Vietnam. International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, 12(1).

Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Article IV (2013). Vietnam General Assembly.

Directives on the Determinations of Reparation Fees for All Eligible Parties in Ha Tinh, Quang Binh, Quang Tri, and Thua Thien Hue Affected by the Marine Environmental Disaster. (2016). Directorate of Fisheries of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. Retrieved from: https://tongcucthuysan.gov.vn/Portals/0/QD-18-QD-TTg-Boithuong-Su-co-Moi-truong.pdf

Green Trees (2016). An Overview of the Marine Life Disaster in Vietnam. San Bernadino, CA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Ha, V. & Boliek, B. (2016a). Formosa Steel Owns Up to Toxic Spill, Agrees to Pay Vietnam $500 Million. Radio Free Asia. Retrieved from: http://www.rfa.org/english/news/vietnam/formosa-steel-owns-up-06302016142903.html

Ha, V. & Boliek, B. (2016b). Vietnamese Authorities Send “Thugs” to Beat Activists. Radio Free Asia. Retrieved from: http://www.rfa.org/english/news/vietnam/vietnamese-authorities-send-02142017143556.html

Hiep, L. H. (2012). Performance-based Legitimacy: The Case of the Communist Party of Vietnam and Doi Moi. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 34(2).

Hoang, D. (2016). Prime Minister: If They Continue to Pollute, We Will Shut Formosa Down. Soha News, Vietnam. Retrieved from: http://soha.vn/thu-tuong-neu-tiep-tuc-gay-o-nhiem-moi-truong-se-dong-cua-formosa-20161117091614463.htm

Institute of Human Studies (2015). World Value Survey (2005-2009) – Vietnam 2006. Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences. Retrieved from: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV5.jsp

Lan, P. (May 2016). Gương mặt của im lặng trong biểu tình. BBC Vietnamese. Retrieved at: http://www.bbc.com/vietnamese/forum/2016/05/160509_protest_comment

Morris-Jung, J. (2015). Vietnam’s Online Petition Movement. Southeast Asian Affairs, 402-415.

Mysterious death of diver adds to ongoing environmental crisis in central Vietnam (April 26, 2016). Thanh Nien News. Retrieved from: http://www.thanhniennews.com/society/mysterious-death-of-diver-adds-to-ongoing-environmental-crisis-in-central-vietnam-61565.html

National Technical Regulation on the Environment for the Steel Industry – QCVN 52-2013/BTNMT(2013). Vietnam’s Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment (MONRE). Hanoi, Vietnam. Retrieved from: http://congnghemoitruong.com.vn/qcvn-522013btnmt-nuoc-thai-cong-nghiep-san-xuat-thep/

National Technical Regulation on Marine Water Quality – QCVN 10-MT:2015/BTNMT(2015). Vietnam’s Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment (MONRE). Hanoi, Vietnam. Retrieved from: http://iren.hueuni.edu.vn/uploads/download/2017_01/files/qcvn-10.2015_nuoc-bien1.pdf

Nhiều vệt nước đỏ lại xuất hiện gần Formosa (April 2017). BCC News Vietnamese. Retrieved at: http://www.bbc.com/vietnamese/vietnam-39562694

Nguyen, H. H. (2016a). Resilience of the Communist Party of Vietnam’s Authoritarian Regime since Doi Moi. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 35(2).

Nguyen, M. (2016b). Formosa Unit Offers $500 Million for Causing Toxic Disaster in Vietnam. Global Energy News, Reuters. Retrieved from: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-vietnam-environment-idUSKCN0ZG1F5

Ong, N. N. (2004). Support for Democracy among Vietnamese Generations. Presented at “Vietnam 2005”. Center for the Study of Democracy, University of California, Irvine.

Scott, J. C. (1972). Patron-Client Politics and Political Change in Southeast Asia. The American Political Science Review, 66(1), 91-113.

Shanks, E., Luttrell, C., Conway, T., Vu, M. L., & Landinsky, J. (2004). Understanding pro-poor political change: the policy process – Vietnam. London, UK: Overseas Development Institute.

Skanavis, C., Koumouris, G., & Petreniti, V. (2005). Public Participation Mechanisms in Environmental Disasters. Environmental Management, 35(6), 821.

Tong, L. (2016). Vietnam Fish Deaths Cast Suspicion on Formosa Ha-Tinht. The Diplomat. Retrieved from: http://thediplomat.com/2016/04/vietnam-fish-deaths-cast-suspicion-on-formosa-steel-plant/

Tromme, M. (2016). Corruption and Corruption Research in Vietnam: An Overview. Crime Law Social Change, 65.

Vu, N. A. (2017). Grassroots Environmental Activism in an Authoritarian Context: The Trees Movement in Vietnam. Voluntas, 28, 1180-1208.

Wells-Dang, A. (2010). Political space in Vietnam: A view from the ‘rice-roots’. The Pacific

Review, 23(1), 94.

Wells-Dang, A. (2012). Civil Society Networks in China and Vietnam: Informal Pathbreakers in Health and the Environment. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

[1] Transcribed by author as presented in original report

[2] “Dân giàu; nước mạnh; xã hội công bằng, dân chủ, văn minh.”

[3] Transcribed by author as presented in original report

[4] “Đảng lãnh đạo, nhà nước quản lý, nhân dân làm chủ.”

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Marine Studies"

Marine studies look at the oceans and seas from the resources they provide, the diverse organisms and life that live in them to the threats and effects of climate change on marine habitats.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: